Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation

La pensée sociale d'Émile Durkheim et Pierre Bourdieu ● Aux origines de la chute de la République de Weimar ● La pensée sociale de Max Weber et Vilfredo Pareto ● La notion de « concept » en sciences-sociales ● Histoire de la discipline de la science politique : théories et conceptions ● Marxisme et Structuralisme ● Fonctionnalisme et Systémisme ● Interactionnisme et Constructivisme ● Les théories de l’anthropologie politique ● Le débat des trois I : intérêts, institutions et idées ● La théorie du choix rationnel et l'analyse des intérêts en science politique ● Approche analytique des institutions en science politique ● L'étude des idées et idéologies dans la science politique ● Les théories de la guerre en science politique ● La Guerre : conceptions et évolutions ● La raison d’État ● État, souveraineté, mondialisation, gouvernance multiniveaux ● Les théories de la violence en science politique ● Welfare State et biopouvoir ● Analyse des régimes démocratiques et des processus de démocratisation ● Systèmes Électoraux : Mécanismes, Enjeux et Conséquences ● Le système de gouvernement des démocraties ● Morphologie des contestations ● L’action dans la théorie politique ● Introduction à la politique suisse ● Introduction au comportement politique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : définition et cycle d'une politique publique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise à l'agenda et formulation ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise en œuvre et évaluation ● Introduction à la sous-discipline des relations internationales

The main objective of this analysis is to explore the path taken by a law, from its formulation to its application and enforcement, generally orchestrated by public institutions.

To explore this issue further, our study is divided into three distinct segments: First, we will return to the notion of implementation in the context of public policy analysis. Essentially, it is a dynamic process, often subject to tensions, which has the potential to radically transform the decisions taken when the law was created. Secondly, we will look at one particular aspect with reference to the situation in Switzerland, more specifically what is known as the 'polity', which corresponds to the country's federalist institutional structure. In this federal dynamic, the Confederation draws up the laws, but it is the cantons and municipalities that put them into practice. This unique arrangement can give rise to a number of challenges, as well as advantages, in the application process. Finally, we will emphasise the importance of taking account of the local situation when evaluating enforcement measures. More specifically, we will examine the behaviour of officials in the field, whether on the street or behind a counter. Rather than focusing on abstract theories, we will back up our arguments with tangible examples.

Implementation: an open and complex process

Implementation studies began to take shape as a distinct discipline within political science in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. It was inspired by a series of academic works aimed at understanding why certain public policies did not produce the expected results once they had been implemented. It was the 'implementation school' that really formalised the subject as a distinct branch of study. Researchers in this school began to examine the implementation process not simply as the execution of policy directives, but as a complex and multidimensional phase of the policy process, involving multiple actors, levels of government and power dynamics. Researchers such as Jeffrey Pressman, Aaron Wildavsky and James Q. Wilson have contributed influential work to implementation theory. Pressman and Wildavsky, for example, wrote "Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland" in 1973, a work often cited as the first major book on the subject.[1] This work has paved the way for a more nuanced understanding of implementation, recognizing that the implementation phase is itself a complex political process, often marked by conflict, negotiation, and compromise.

"Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It's Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga ... Morals on a Foundation" is a seminal work that truly launched the field of study of public policy implementation. Written by Jeffrey L. Pressman and Aaron Wildavsky in 1973, the book exposes the complex and often surprising challenges of implementing public policy. The book's subtitle raises a central question: how the high expectations formulated in Washington can clash with the reality on the ground in Oakland. It highlights the potential gap between the formulation of a policy (the intention) and its actual implementation (the reality). This raises questions about the effectiveness of federal programmes, given the complexity of the implementation process. By revealing this complexity, Pressman and Wildavsky paved the way for a multitude of studies on implementation. These studies have sought to understand the many nuts and bolts of successful implementation and to highlight the many obstacles that can impede the process. In doing so, they have contributed to a more nuanced understanding of public policy, one that recognises implementation as an essential and distinct phase of the policy process, rather than a mere formality once the policy decision has been made.

The almost canonical definition of implementation is a social process in which actors assert their interests, powers and opportunities for influence. This definition highlights the complexity and dynamics of the process. Indeed, implementation is often perceived as a social process involving various players seeking to promote their interests, exercise their power and use their means of influence. Laws, ordinances and other prescriptions are not simply fixed rules to be applied; rather, they are normative offers that different actors can interpret and use in different ways to achieve their objectives. In other words, these 'offers' serve as resources that actors in the field can exploit, modify, adapt or even challenge, depending on their own interests and the way they perceive these normative offers. This perspective underlines the importance of actors on the ground in determining the actual content of a public policy. The decisions they take, the strategies they adopt and the interpretations they make of legal requirements can significantly influence the final outcome of implementation, and therefore the actual impact of public policy on society.

Describing implementation as an "implementation game" underlines its negotiated, strategic and interactive nature. Rather than being a simple process of mechanically applying the law, implementation is a dynamic process, in which different actors interact, negotiate, cooperate and sometimes oppose each other, in order to advance their interests and objectives. This 'game' can involve a wide range of actors, including implementers within the public administration, policy beneficiaries, interest groups, service providers and other stakeholders. Each of these actors may have different interests, priorities and perspectives, and may use different strategies to influence the implementation process and its outcomes. This perspective highlights the open and complex nature of implementation, showing that it is a process that is shaped by ongoing interactions, negotiations and conflicts between different actors. It also highlights the uncertain and unpredictable nature of implementation, as the outcome of the 'implementation game' may depend on many factors, including power dynamics, available resources, contextual conditions and unforeseen events.

Executive federalism - diversity and deficits in the cantons

What does this mean in practice in Switzerland? In Switzerland, executive federalism is the practical expression of the division of powers between levels of government in the process of implementing public policy. Under this system, policy formulation is dominated by the federal institutions, in particular the National Council, the Council of States and sometimes even the people through direct-democratic votes. However, once these policies have been defined, responsibility for their implementation is generally delegated to the cantons and municipalities. This structure reflects the high degree of decentralisation and local autonomy in Switzerland, allowing each canton to tailor implementation to specific local conditions. However, this system can also lead to variations in implementation between different cantons, depending on their interpretation of policies, their resources and capacities, and their political priorities. In addition, it can sometimes lead to tensions between the federal level and the cantons over issues such as the allocation of resources and responsibilities, or the interpretation of federal laws.

The configuration of executive federalism in Switzerland, where the Confederation draws up laws and the cantons are responsible for implementing them, is in reality more complex than a simple division of tasks. This division is not always clear-cut and rigid, and there is often considerable room for manoeuvre for the cantons, and even the municipalities, in applying federal laws. This autonomy can give rise to an impressive diversity in the way the same law is implemented from one canton to another, and even from one municipality to another. This diversity can be reflected not only in the specific actions taken to implement the law, but also in the effects of that implementation on citizens. So even if a law is uniform at federal level, the way it is applied and the effects it has can vary considerably from one place to another. In some cases, this can lead to significant differences in the treatment of Swiss citizens, potentially creating de facto inequalities between them. This situation highlights the importance of taking local and regional specificities into account when analysing the implementation of public policies in Switzerland. It also highlights the need to balance local autonomy and national uniformity in the implementation of public policy, in order to ensure that the law is applied fairly and equitably.

We will examine how conventional analytical questions can shed light on the effects of executive federalism. More specifically, we will seek to understand how the political and institutional structure - which we will call 'polity' - influences policy implementation - or 'public policy'. In other words, we will explore how federalism in Switzerland concretely affects the implementation of public policy.

Analysing the impact of federalism (polity) on the implementation of public policy in Switzerland requires an understanding of how the country's institutional and political framework influences implementation practices. Executive federalism, in which the cantons and municipalities are largely responsible for implementing federal laws, has several important implications. Firstly, federalism allows a degree of flexibility in the application of public policy. This means that the cantons can adapt implementation to specific local conditions and the needs of their citizens. For example, an education or health policy may be implemented differently depending on the resources available, local political priorities and the demographic or socio-economic characteristics of the cantons. Secondly, federalism can lead to diversity in the implementation of public policy, with potentially significant differences between cantons. This diversity can be beneficial in allowing policy experimentation and fostering innovation, but it can also lead to inequalities and variations in the quality of services provided to citizens. Thirdly, federalism can create challenges in terms of coordination and efficiency. Coordination between different levels of government can be difficult, especially when responsibilities are shared or when policies require concerted action at several levels. In addition, fragmented responsibilities can make it more difficult to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of policies. In short, federalism in Switzerland has a significant impact on the implementation of public policy, offering opportunities for adaptation and innovation, but also posing challenges in terms of equality, coordination and effectiveness.

Case study - Wildlife control/hunting (cf. Nahrath study, 2000)

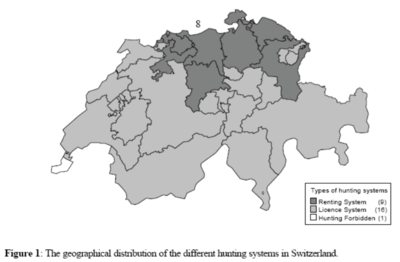

The first example we are going to look at is the regulation of hunting in Switzerland, a topical issue. If we look at the way in which hunting and wildlife are managed, we see a fairly notable diversity of approaches, reflecting what might be described as a "federalist laboratory". In other words, the cantons are experimenting with different methods of regulating hunting, creating a variety of approaches and solutions across the country.

Why is this? Under the Swiss Federal Constitution, the allocation of hunting rights is a public monopoly. However, it is up to the cantons to determine the hunting regime to be implemented to regulate not only who can hunt, but also at what intensity. The Confederation limits itself to regulating certain aspects such as protected species (not just any animal can be hunted), the types of weapons that can be used and the use of traps. When we analyse public policy, we sometimes find ourselves in a wide variety of areas. For example, we are going to look at how the cantons have chosen to regulate hunting, given the wide discretion granted to them by the Federal Constitution.

There are several ways in which the Swiss cantons can regulate hunting, depending on their interpretation of the Constitution and federal laws. This can result in a variety of hunting regimes, with each canton adapting the rules to its own needs and circumstances. For example, some cantons may choose to allocate hunting rights on an individual basis, perhaps according to the hunter's skills or experience. Other cantons may prefer a licence system, perhaps limiting the number of licences available or allocating them by lot. In addition, each canton has the ability to determine the intensity of hunting that is permitted. This may include regulations on the number of animals that can be shot, the species that can be hunted, or even the times of year when hunting is permitted. The impact of this diversity of regulations is twofold. On the one hand, it allows a degree of experimentation and innovation in hunting management, with each canton able to adapt its rules to best meet local needs. On the other hand, it can also lead to inequalities, with hunters in some cantons potentially subject to stricter rules than those in other cantons. This analysis shows how the autonomy granted to the cantons under Swiss federalism can influence the implementation of public policies. While this may allow a degree of flexibility and adaptation to local conditions, it can also lead to disparities between regions.

This breakdown of hunting regulation in Switzerland clearly demonstrates the diversity of public policies resulting from the interpretation of federal laws by the various cantons. In the canton of Geneva, hunting is banned outright, which is a unique exception in the country. This probably reflects stronger environmental values, as well as a high population density that makes hunting less practicable. In the Romansh-speaking, Alpine and Appenzell Inner and Outer Rhodes cantons, hunting is regulated by a permit system. This means that anyone wishing to hunt must obtain a licence, which is probably issued on the basis of certain criteria, such as the hunter's skill or experience. Finally, in the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland, hunting is regulated by a "leasing" system. Under this system, hunting rights for a certain area are 'leased' to an individual or group, who then have the right to hunt there for a set period. This allows for more intensive and targeted wildlife management. This variety of hunting regimes shows how cantons can adapt federal laws to their own needs and circumstances, leading to a diversity of public policies across the country. It also highlights the importance of examining the implementation of public policies at a local level to fully understand their impact.

In the canton of Geneva, hunting is strictly reserved for professional gamekeepers, making private hunting prohibited. This particular regulation has several notable consequences. Firstly, it entails significant costs for the canton. Indeed, recruiting professional gamekeepers to manage the animal population involves significant expenditure. In addition, the canton of Geneva does not receive any income from the sale of hunting licences, which would be the case if private hunting were authorised. Furthermore, this particular regulation of hunting is associated with certain criticisms in terms of hunting ethics, i.e. the moral principles that govern the practice of hunting. For example, it is generally forbidden to hunt at night with infrared weapons, for reasons of safety and respect for wildlife. However, in Geneva, these rules are not always respected, because of the risk of accidents if hunting takes place during the day. Gamekeepers are therefore sometimes forced to hunt at night, contrary to federal law, in order to maintain the ban on private hunting. This illustrates how the implementation of public policy can lead to ethical and practical dilemmas, requiring a delicate balance between different priorities and constraints.

In the case of cantons that adopt the hunting licence system, access to this activity is regulated by issuing licences to different hunters. These hunters can then hunt throughout the canton within the limits defined by the licence, often in the form of animal quotas that must not be exceeded. However, this system of regulation by permit presents its own challenges. In particular, wildlife is often under-exploited, i.e. the number of animals slaughtered is lower than the quotas set. This can lead to ecological imbalances, with negative impacts on forests and crops. In the canton of Geneva, for example, an excessive wild boar population can cause considerable damage to crops. So, unlike the system in place in Geneva, where wildlife is managed by professionals, the hunting licence system does not necessarily guarantee balanced wildlife management throughout the canton. It thus reveals the limits of a decentralised approach to the implementation of public policies, where local variations can lead to uneven results.

The third model of hunting administration found in Switzerland is that of leasing. This system differs significantly from the previous two in that it does not allocate individual hunting permits, but rather entrusts the management of a territory to a hunters' association for a period of 6 to 8 years. During this period, the association is responsible for regulating the number of animals that can be hunted and is also liable for any damage caused by wildlife to forests or crops. At the end of each cycle of 6 to 8 years, the leasing right is auctioned off again. If a hunting association has mismanaged its territory during this period, it risks losing its leasing rights at the next auction, which could lead to its exclusion from hunting. This leasing system therefore creates an incentive for responsible management of wildlife and its impact on the local environment.

The empirical analysis carried out on these three hunting management systems revealed that, in terms of sustainability and rational wildlife management, the leasing system is generally the most effective. By entrusting responsibility for wildlife management to a hunters' association for a specific area, better results are obtained than those obtained either by entrusting this task to bureaucrats or by granting individuals the opportunity to hunt via a licence. Leasing seems to promote more effective and sustainable wildlife management than the other methods examined.

Although these three systems derive from the same delegation of powers to the federal level, they differ markedly in terms of implementation methods and impact. This is precisely what executive federalism allows: it provides a framework for experimenting with different implementation solutions in a "federalist laboratory". In the case of hunting, this system has enabled valuable lessons to be learned from the different approaches employed by the cantons. However, this process of learning and adaptation is not limited to the management of hunting. It can be found in various other public policies. For example, in the field of drug regulation, the cantons of Geneva, Zurich and Basel have experimented with different management methods. Lessons can then be learned from these experiments and the most effective model adopted. The same applies to various social policies: implementing federalism not only makes it possible to benefit from a diversity of approaches, but also to test different solutions, before finally choosing and adopting the one that proves to be the most effective. This shows that, in many areas, executive federalism can be a valuable tool for innovation and improving public policy.

Case study - Acquisition of property by foreigners (cf. study by Delley et al., 1982)

The Swiss Federal Law on the Acquisition of Real Estate by Persons Abroad, commonly known as the "Lex Koller", was introduced in the 1960s in response to an increase in the number of property purchases by non-residents. The aim of this legislation was to control the acquisition of property by foreigners in Switzerland. The law was put in place to protect national interests and to prevent excessive property inflation that could make housing unaffordable for Swiss residents. It is a protectionist measure designed to protect the Swiss property market from foreign speculation. Jean-Daniel Delley, Professor of Law at the University of Geneva, has produced a classic analysis of this policy. It is interesting to examine how the implementation of this law was influenced by Swiss federalism, and how it varied from canton to canton.

In the 1960s, certain groups in Switzerland were concerned about the increase in foreign purchases of property, fearing that this would lead to greater foreign control over Swiss soil. These concerns were particularly pronounced among certain sectors of the political right, which had a more nationalist outlook. They argued that this trend represented a threat to Swiss national interests, not least because rising property prices were making housing less affordable for Swiss residents and because increased foreign control over Swiss soil could threaten national sovereignty. These concerns contributed to the drafting of the law on the acquisition of real estate by persons abroad, known as the "Lex Koller". This law was designed to restrict the purchase of property in Switzerland by non-residents, with the aim of protecting the Swiss property market and preserving national sovereignty.

In addition to the nationalist concerns of the right, the Swiss left also had concerns about the increase in property purchases by foreigners, but for very different reasons. The left was mainly concerned about the socio-economic impact of these acquisitions. Specifically, they feared that the purchase of property by foreign investors, with the aim of speculating on the property market, would lead to an increase in rents across the country. This, in turn, could make housing less affordable for many Swiss people, particularly those on moderate incomes. In addition, it could contribute to a scarcity of low-cost housing, further exacerbating Switzerland's housing problems. So while the right was primarily concerned about sovereignty and foreign control, the left was worried about the socio-economic implications of increased foreign property purchases. These joint concerns helped shape the debate on property ownership policy for non-residents.

A third group of players also took part in the debate, namely the liberal right. This political faction saw no need for regulation on this issue. Instead, they defended the principle of private property and Switzerland's traditional approach to free trade. In their view, foreign ownership was not in itself a problem. As a result, they opposed any state intervention in property construction or rent control, nor did they see any danger in the idea of foreign influence on Swiss territory. For them, the free market should be the main determinant of property transactions, regardless of the nationality of the owner.

The forces of these three parties were fairly balanced, and no clear majority emerged in favour of any one of them. So a compromise was reached that allowed all parties to express their views. It was recognised that there was a need to exercise control over this issue, and that a foreigner wishing to acquire real estate in Switzerland would have to obtain formal authorisation from the State. However, the question remained as to the conditions under which such authorisation could be granted. This is where the subtlety of implementation came into play, and where the role of executive federalism was crucial in the practical application of this policy.

In the text of the law, authorisation to acquire a building is granted "if there is a legitimate interest". This is what is known as an indeterminate legal concept, which leaves a great deal of room for interpretation. Given Switzerland's federal structure, it was the cantons that were responsible for implementing this law. The cantons were therefore responsible for defining in concrete terms what was meant by "legitimate interest". The law had very different objectives and there was no solid consensus at federal level. As a result, when the law was implemented, it was used to suit the specific interests of the cantons and local regions. Some have described this as a "misuse of the law" by the cantons, as the interpretation of legitimate interest varied widely from one canton to another, depending on their own priorities and concerns.

The graph shows how, in an initial situation where cantonal practices were in some respects similar or comparable, the introduction of various laws aimed at controlling, or even reducing, the acquisition of property by foreigners led to a significant divergence in the approaches adopted by the different cantons. The different cantons then adopted distinct strategies for interpreting and applying these laws. This reflects the flexible aspect of implementing federalism, which allows local authorities to adapt the implementation of national laws to their own specific needs and concerns. This variety of approaches can also be seen as a 'laboratory' for policy experimentation, where different strategies can be compared and evaluated for their effectiveness.

The canton of Valais has chosen to interpret the notion of 'legitimate interest' in relation to its ambition to promote tourism through the inflow of foreign capital. As a result, the canton has adopted a policy of expanding tourism by granting permits fairly freely, thereby enabling a large amount of housing to be built for non-residents. Even when the Confederation expressed doubts about the legitimacy of some of these authorisations, Valais found ways of getting round these objections. One such method was to set up local trusts which, although officially Swiss, were financed by foreign capital. These trusts enabled foreigners to acquire property indirectly, through a 'pseudo-Swiss' entity, in order to circumvent the restrictions on the purchase of property by non-residents. This illustrates how, depending on local priorities, the application of a federal law can be creatively adapted.

The canton of Lucerne has taken a very different approach in applying the same law. Despite its tourist appeal, Lucerne has chosen to use this legislation as a tool to limit foreign control over local development, favouring local and Swiss investment. Unlike Valais, Lucerne has granted very few authorisations for the purchase of real estate to foreigners. The authorisation curve in the canton of Lucerne is almost at zero, which shows that the canton has adopted a very strict policy when it comes to controlling property purchases by foreigners. This difference in approach is a good example of how the implementation of the same law can vary considerably depending on the local context and priorities. So, even with federal legislation, there can be a wide variety of outcomes depending on how each canton chooses to implement it.

In the canton of Geneva, the approach to the application of the law on the purchase of property by foreigners has varied according to fluctuations in the local property market. When the property market is growing and demand for housing is strong, the canton may have been more willing to grant purchase authorisations to foreigners because of the potential economic benefits of such investments. Conversely, during property market downturns, the canton could have adopted a more restrictive approach to limit foreign speculation and protect local residents from rising rents and property costs. This illustrates how the cantons can adapt their implementation of federal laws to suit local economic conditions and the needs of their population. It also demonstrates the flexibility that Swiss federalism allows the cantons in applying the law, even when that law is enacted at federal level.

Studying the implementation of laws, particularly those that are broadly or vaguely formulated, is an essential part of public policy analysis. It allows us to understand not only how a law is interpreted and applied in different contexts, but also how its application can vary according to local conditions and the values and interests of the actors involved. In the case of the Swiss law on the acquisition of real estate by foreigners, the concept of 'legitimate interest' leaves a great deal of leeway to the cantons in determining what constitutes a legitimate interest. As a result, as we have seen, the application of the law can vary considerably from one canton to another, depending on how each canton interprets the concept. This highlights the importance of the implementation of the law in determining its real effects and raises interesting questions about the role of federalism and decentralisation in the management of public policy. It also highlights the importance of empirical research in the study of public policy, as it allows us to see how laws work in practice, beyond what is written in the text of the law itself.

Case study - Disability insurance reforms (see study by Byland et al. 2015)

The precise wording of a law can effectively reduce variability in its application, as it leaves less room for interpretation. However, this does not necessarily guarantee uniform application of the law. Differences in implementation can still arise due to a variety of factors, including differences in available resources, political priorities, the competence of those responsible for implementation, and administrative culture. The 2015 study by Byland et al. on disability insurance reforms in Switzerland is a good example of this. Despite the fact that the law on invalidity insurance was fairly precisely formulated, they found significant variations in implementation between cantons. These variations were due to factors such as differences in the resources available to implement the law, differences in the interpretation of the legislative provisions, and differences in the administrative culture and political priorities between the cantons. This illustrates the importance of analysing implementation in the study of public policy, as even a well-conceived and precisely formulated law can lead to varied results depending on how it is implemented. It is therefore crucial to take contextual factors into account when analysing the impact of a law and its reforms.

The graph seems to indicate that, at a certain point, a policy was put in place with the aim of reducing the number of disability insurance beneficiaries and, consequently, reducing the disability insurance deficit. This inflection point may be the result of various measures taken, for example the introduction of stricter criteria for eligibility for invalidity insurance, increased requirements for rehabilitation or professional reintegration, or the application of stricter controls to combat fraud. It is also possible that external factors, such as an improving economy or changes in the structure of the population (for example, a drop in the number of people with chronic illnesses or long-term conditions), have contributed to the decline in the number of disability insurance beneficiaries.

The development of disability insurance policy in Switzerland can be examined over three distinct periods: 1999 - 2003, 2004 - 2007 and 2008 - 2011. Each period was characterised by a specific policy direction. From 1999 to 2003, the dominant policy was that of granting pensions. In other words, when a person could no longer work because of disability, they received a pension. This traditional approach encouraged many people to claim pensions, which led to an increase in disability insurance deficits. In 2003, faced with increasing deficits, a reform was introduced. The new approach continued to grant pensions, but only if individuals could not be reintegrated into the labour market. Pensions remained the main instrument, while trying to keep disabled people active in the labour market as much as possible. For example, granting partial pensions was an option, allowing recipients to work part-time while receiving a pension, which reduced the pressure on disability insurance. However, this measure proved insufficient to put disability insurance finances on a sounder footing. As a result, new restrictions were introduced, fundamentally changing the philosophy of disability insurance policy. Since 2008, the granting of a pension has been considered only as a last resort. To qualify for a pension, you have to prove that all possible measures to reintegrate yourself into the labour market have been unsuccessful. This development means that, over time, obtaining a pension has become increasingly difficult. The emphasis is now on getting disabled people back into work and keeping them there, even on a part-time basis.

How is this federal policy applied at cantonal level? Federal policy on invalidity insurance is implemented at cantonal level by the AI (Invalidity Insurance) Offices. These offices are responsible for examining applications for invalidity pensions and deciding whether or not to accept them. When an application is made, the AI Office assesses the applicant's disability and determines whether it is serious enough to justify the granting of a pension. This assessment takes into account various factors, including the claimant's ability to work (either full-time or part-time), the employment opportunities available and the effectiveness of rehabilitation or reintegration efforts. However, although disability insurance policy is federal, the way in which it is implemented can vary from canton to canton. Each IV office may have its own procedures and criteria for assessing claims. As a result, there may be variations in the acceptance rates for disability claims between different cantons. This means that the way in which this policy is implemented on the ground can depend largely on the interpretation and individual management of each IV Office. This is why it is important to understand how each canton applies this policy, to ensure that it is implemented effectively and fairly across the country.

In this context, three distinct periods are highlighted, along with the national average disability pension approval rate. As time passes, there is a steady decline in the acceptance rate for pension claims, meaning that fewer and fewer pensions are being granted in relation to the claims made. The central concern for a political scientist in this situation is to determine whether the chances of obtaining a pension are uniform across all the cantons, or whether the application of the policy at cantonal level could lead to discrimination. In other words, is it possible for the same situation to give rise to totally different decisions by the cantonal administration, despite the fact that they are all subject to the same federal law? This question raises issues of fairness and uniformity in the application of the law.

It is clearly illustrated here that the acceptance rate for pension applications decreases as we move forward in time, indicating that it is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain a pension. The relevant question for a political scientist would be to determine whether the chances of obtaining a pension are equal in all cantons, or whether the application of federal law by the various cantons can lead to discrimination. In other words, could the same situation lead to different administrative decisions depending on the canton, even if they are all governed by the same federal law? This question is all the more important as it could have significant implications in terms of fairness and equal access to disability benefits. This is why it is essential to understand how policies are implemented at different administrative levels and whether these differences can lead to inequalities between cantons.

We often hear talk of the "Lake Geneva syndrome", a notion that suggests that only the cantons in French-speaking Switzerland grant pensions. The canton of Valais is the most restrictive in this respect, while the canton of Neuchâtel has seen its practices tighten up over time. What we can see is that all the cantons are adopting an increasingly strict approach, but at very different speeds. As a result of these successive reforms, there appears to be increasing diversity in the way the cantons implement the policy, and potentially greater inequality in the treatment of citizens depending on the canton in which they live.

The box plots presented here show the median, as well as the first, second, third and fourth quartiles. An initial dispersion can be seen, which is initially reduced, then increases significantly during the third period. Today, inequality of treatment, in the political sense of the term, seems to have increased between the cantons. However, it should be noted that this analysis is purely quantitative. It would be necessary to compare comparable cases in different cantonal systems to determine whether objectively similar situations of disability lead to radically different decisions.

Case study - Snow guns

Let's take the example of hypothetical legislation concerning the use of snow guns in ski resorts. Let's assume that this law clearly states that it is forbidden to use these machines between certain hours in order to minimise their impact on the environment. On paper, this rule is simple and straightforward. However, its implementation can be affected by a number of factors at local level. For example, local authorities may come under pressure from ski resort operators, who argue that the ban is damaging their operations and therefore the local economy. There may be a flexible interpretation of the law, with some officials turning a blind eye to non-compliance during peak periods of the ski season. In other cases, the application of the law may be inconsistent, with penalties for some offenders and not for others. There is also the possibility of what is known as "circumvention of the law". For example, ski resort operators can technically comply with the ban by switching off the machines during the prescribed hours, but they can switch them on again immediately afterwards, perhaps at a higher level to compensate for the time lost. In this way, they respect the letter of the law, but not its spirit. So, although the law on the use of snow cannons is clear and precise, its actual implementation can vary considerably, depending on factors such as local economic pressures, the interpretation of the law by those in charge and the tactics used to get round the law. This can lead to significant differences between the original purpose of the law and its actual impact on the ground.

The implementation of policies at local level can be strongly influenced by the power dynamics and relationships between the different actors involved. Specific configurations of actors can create considerable obstacles to the effective application of rules. For example, in a local community, a number of influential actors, such as business leaders, elected representatives or special interest groups, may oppose the application of a certain rule because of their own interests or beliefs. They may use their power and influence to challenge, delay or hinder the implementation of the rule. In some cases, actors may engage in rule-bypassing activities, for example by exploiting loopholes or ambiguities in the legislation, putting pressure on those responsible for enforcing the rules, or mobilising public opinion against the rule. This underlines the importance of taking account of local realities and power dynamics when designing and implementing policies. A thorough understanding of local actors, their interests and their relationships can help to anticipate potential challenges to the application of rules and to develop strategies to deal with them.

Clearly, the implementation of this specific rule on artificial snowmaking is fraught with challenges because of the diversity of the players involved and their divergent interests. Firstly, there is the commune of Les Agettes, a small town in the Valais, which is considering a merger with the town of Sion. Local decision-makers may be more concerned about the economic and political implications of this potential merger than about applying the rule on artificial snow. Secondly, there are the local environmental groups, who are seeking to enforce the law banning artificial snow before November 1, in order to protect the natural environment. Thirdly, there is the local promoter of Téléveysonnaz, who may have a commercial interest in early snowmaking to extend the ski season and attract more tourists. Finally, there are the hydropower producers, who need water to generate electricity. They might prefer their water not to be used for artificial snowmaking, as they need hydroelectricity for other uses, notably industrial and heating purposes, particularly during cold spells. Thus, the effective implementation of the rule on artificial snowmaking comes up against a variety of interests and local dynamics. This situation illustrates the complexity of the challenges involved in implementing policies, even when the law is clear and unambiguous.

This example highlights how local power dynamics can influence the effective implementation of public policy. In this case, Mr Fournier, described as an influential tourism player, appears to have enough power to openly circumvent the law on artificial snow. This behaviour suggests a perception that certain individuals or groups are, de facto, 'above the law' because of their local influence. What is particularly surprising in this situation is the passivity of local authorities and environmental groups. Although the latter might be expected to want to enforce the law, they have not prosecuted this illegal act. This might suggest that the reality of local power relations can sometimes go beyond the legal framework and policy implementation, and that the actors involved may be unable or unwilling to challenge these power dynamics due to various factors, such as political, economic or other considerations.

This example illustrates how, when implementing a policy, the law can sometimes be ignored or circumvented. In this case, no request for authorisation was submitted, the municipality that should have granted it did not react, and no action was reported to the cantonal authorities. What seems to exist is a tacit agreement between all the players involved: the law will simply not be applied. This situation highlights the complexity of implementing public policies, where local institutional, social and political forces can sometimes interfere with strict compliance with the law. It also highlights the importance of the local context and power dynamics in the interpretation and application of public policies.

This example is certainly evocative, but it is important to note that in some cases the stakes can be much higher than the snow cover on a few ski slopes. The concept of the "implementation gap" becomes crucial when, despite the clarity of the law, local resistance prevents the effective application of legal norms. This reminds us that drafting a law is only the first stage in the process of implementing public policy. The implementation of these laws can be hampered by various factors, including local resistance, conflicts of interest, power dynamics and variations in the interpretation of laws. This is why it is essential to examine public policies not only in the context of their conception, but also in the context of their implementation on the ground.

Bureaucracy "on the ground"

Concept and definition

In addition to executive federalism, another factor explaining the difficulties associated with policy implementation is the role of the "street-level bureaucrats" or front-line agents, also known as front-office agents. These are the individuals who work on a daily basis with the beneficiaries of public policies, and they often have a wide discretion in the way they apply directives and regulations. These front-line agents can include a variety of professionals such as social workers, teachers, police officers and many others. Their day-to-day interaction with citizens gives them a unique perspective on the effects of policies on the ground. As a result, they can play a decisive role in implementing policies, often by adapting, interpreting or even modifying directives to meet the specific needs of the people they work with.

Field" bureaucrats are civil servants who interact directly and frequently with citizens. They are responsible for granting authorisations or providing services. However, a key element of their role is their discretion, which allows them to tailor the implementation of policies to specific situations. The guidelines and rules they are charged with implementing are often not detailed enough to cover all possible situations. As a result, these bureaucrats have the freedom to interpret and apply these rules flexibly, according to their personal judgement. Moreover, these officials often enjoy a degree of autonomy from their superiors, reinforcing their discretionary power. This means that they have the freedom to make decisions without having to obtain prior approval from their superiors. It is this combination of discretionary power and autonomy that enables these field bureaucrats to have a significant influence on the way policies are implemented.

Appliquer les attributs précédemment mentionnés - interaction régulière et directe avec les citoyens, pouvoir d'interprétation et discrétion - nous mène à comprendre que de nombreux fonctionnaires jouent un rôle déterminant. Parmi eux, on compte les enseignants, les professeurs d'université, les policiers, les travailleurs sociaux, les juges, et le personnel soignant. Ces bureaucrates de terrain se retrouvent souvent face à une multitude de situations pour lesquelles les directives de la politique publique qu'ils mettent en œuvre ne peuvent pas prévoir chaque détail. Les situations concrètes et individuelles auxquelles ils sont confrontés sont si variées que c'est à eux d'évaluer en temps réel les meilleures actions à entreprendre. Cela peut aller de la décision d'imposer ou non une sanction, de fournir ou de refuser un soin, de sélectionner un sujet particulier à discuter ou non, et ainsi de suite. Ainsi, il leur revient de prendre des décisions instantanées selon les situations rencontrées : déterminer s'il faut appliquer une sanction ou pas, décider de prodiguer des soins ou non, opter pour un sujet particulier à traiter ou le mettre de côté, et ainsi de suite.

Lors de l'élaboration d'une politique publique, les décideurs doivent prendre en compte le fait que, pendant la phase de mise en œuvre, ils pourraient se heurter à la résistance des bureaucrates de terrain, c'est-à-dire ceux qui sont chargés de mettre en pratique la politique sur le terrain. Ces bureaucrates de terrain, qu'il s'agisse de policiers, d'enseignants, de travailleurs sociaux ou d'autres fonctionnaires en contact direct avec le public, possèdent une marge de manœuvre discrétionnaire dans l'application des politiques. Ils ont le pouvoir d'interpréter les règles et de décider comment les appliquer dans des situations spécifiques. Cette latitude peut être utilisée pour façonner, modifier ou même contrecarrer les intentions initiales de la politique. Par exemple, dans le domaine de l'éducation, un enseignant peut choisir d'interpréter et d'appliquer les directives du programme d'une manière qui reflète ses propres convictions ou la réalité spécifique de sa classe. De même, un policier peut choisir d'appliquer la loi de manière sélective ou à partir de sa propre interprétation des règles. De plus, la résistance à la mise en œuvre peut également être une forme de rétroaction de la base vers le sommet. Les bureaucrates de terrain, confrontés à la réalité quotidienne de la mise en œuvre des politiques, peuvent identifier des problèmes ou des obstacles imprévus qui n'étaient pas apparents lors de la formulation de la politique. Leurs réactions peuvent donc offrir des enseignements précieux pour l'amélioration des politiques futures. Il est donc crucial pour les décideurs de prendre en compte cette dynamique lors de l'élaboration des politiques publiques. Une bonne compréhension de la réalité de terrain, des mécanismes de mise en œuvre et des potentiels de résistance peuvent grandement contribuer à la réussite de la politique. Pour ce faire, il peut être bénéfique d'impliquer les acteurs de terrain dès la phase d'élaboration des politiques et de mettre en place des mécanismes de suivi et de feedback afin d'adapter la politique en temps réel et de garantir son efficacité.

Michael Lipsky, dans son ouvrage "Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service", publié en 1980, a mis en évidence le rôle crucial que jouent les bureaucrates de terrain dans la mise en œuvre effective des politiques publiques.[2] Selon lui, les décisions prises par ces acteurs, les routines qu'ils établissent et les stratégies qu'ils développent pour faire face aux incertitudes et aux pressions du travail deviennent, en réalité, les politiques publiques qu'ils mettent en œuvre : « I argue that the decisions of street-level bureaucrats, the routines they establish, and the devices they invent to cope with uncertainties and work pressures, effectively become the public policies they carry out. I argue that public policy is not best understood as made in legislatures or top-floor suites of high-ranking administrators, because in important ways it is actually made in the crowded offices and daily encounters of street-level workers ».

Lipsky soutient que pour comprendre réellement la politique publique, il ne faut pas uniquement se concentrer sur les décisions prises dans les législatures ou par les hauts fonctionnaires. Au contraire, il souligne que la politique publique est en grande partie façonnée dans les bureaux bondés et les interactions quotidiennes des travailleurs de première ligne. Cette idée remet en question la vision traditionnelle de la formulation des politiques publiques, qui suppose généralement que les décisions prises par les législateurs et les administrateurs de haut niveau sont directement traduites en action sur le terrain. Au lieu de cela, Lipsky souligne l'importance de reconnaître l'autonomie et le pouvoir discrétionnaire des bureaucrates de terrain, qui jouent un rôle actif et décisif dans la mise en œuvre des politiques. La reconnaissance de ce phénomène a des implications importantes pour la conception et la mise en œuvre des politiques publiques. Cela implique que les décideurs doivent non seulement prendre en compte les intentions et les objectifs de la politique, mais aussi la manière dont ils seront interprétés et mis en œuvre par les acteurs de terrain. Cette perspective souligne l'importance d'impliquer ces acteurs dès le début du processus de formulation des politiques et de mettre en place des mécanismes pour recueillir leurs retours et adapter la politique en conséquence.

Les interactions entre les bureaucrates de terrain et les citoyens sont au cœur de la mise en œuvre effective des politiques publiques. Ces interactions sont le moment où les politiques publiques sont interprétées, appliquées et ajustées en fonction des situations individuelles. Ces bureaucrates de terrain ont non seulement un contact direct avec les citoyens, mais ils ont aussi une compréhension détaillée et nuancée des contextes locaux et des problèmes spécifiques que les politiques publiques visent à résoudre. Ils sont souvent en mesure de voir les effets des politiques publiques sur le terrain et de comprendre comment elles peuvent être adaptées pour mieux répondre aux besoins des citoyens. Les interactions entre les bureaucrates de terrain et les citoyens peuvent également avoir un impact significatif sur la perception qu'ont les citoyens des politiques publiques et de l'administration publique en général. Leur attitude, leur comportement et la manière dont ils appliquent les politiques publiques peuvent influencer la confiance des citoyens dans les institutions publiques et leur volonté de se conformer aux politiques publiques. En fin de compte, si nous voulons comprendre comment les politiques publiques sont réellement mises en œuvre et comment elles pourraient être améliorées, il est crucial de se concentrer sur ces interactions au niveau de la rue. Cela nécessite une approche plus décentralisée et participative de la politique publique, qui prend en compte le rôle actif que jouent les bureaucrates de terrain dans la mise en œuvre des politiques.

Les bureaucrates de terrain, ou "street-level bureaucrats", jouent un rôle crucial dans la mise en œuvre des politiques publiques. Leurs actions, leurs décisions, les routines et les stratégies qu'ils mettent en place peuvent avoir un impact significatif sur la façon dont les politiques sont appliquées et interprétées. Par exemple, un travailleur social qui interprète et applique les directives relatives à l'aide sociale va influencer directement la manière dont ces aides sont distribuées, à qui elles sont attribuées, et comment elles sont perçues par les bénéficiaires. De la même façon, un enseignant va décider de la meilleure manière d'appliquer un programme scolaire et son interprétation et son application vont directement affecter les expériences éducatives des élèves. Par conséquent, ces bureaucrates de terrain sont en fait des acteurs essentiels de la politique publique. Ils sont ceux qui "font" réellement la politique sur le terrain. Leur rôle va donc bien au-delà de la simple exécution des politiques telles qu'elles ont été conçues par les décideurs à un niveau supérieur. Ils sont des agents actifs dans le processus de mise en œuvre, façonnant et influençant la politique à travers leurs interactions quotidiennes avec les citoyens. Cette perspective souligne l'importance de considérer les acteurs de terrain lors de la conception et de l'évaluation des politiques publiques. Il est essentiel de comprendre leurs perspectives, leurs défis et leurs stratégies pour mettre en œuvre efficacement les politiques publiques.

Cas d'application d'une réforme de la politique sociale en Californie (Référence : étude Meyer et al., 1998)

Cette réforme de la politique sociale en Californie visait à favoriser le "workfare" plutôt que le "welfare", c'est-à-dire à encourager les bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale à retourner sur le marché du travail plutôt qu'à rester dépendants de l'aide gouvernementale. Dans ce contexte, les travailleurs sociaux ont joué un rôle essentiel dans la mise en œuvre de cette réforme. En tant que bureaucrates de terrain, ils étaient en première ligne pour interagir avec les bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale, leur expliquer les nouvelles exigences de la réforme, les aider à naviguer dans le processus de recherche d'emploi et les soutenir tout au long de cette transition. Cependant, les travailleurs sociaux ont également eu une marge de manœuvre dans l'interprétation et l'application de cette réforme. Ils ont dû prendre des décisions discrétionnaires en fonction de leur évaluation de la situation de chaque bénéficiaire, de leurs capacités et de leurs besoins. Ils ont également dû faire face à des défis et des dilemmes, comme la difficulté de réconcilier les objectifs de la réforme avec les réalités du marché du travail et les circonstances individuelles de chaque bénéficiaire. Cette étude met donc en évidence l'importance des bureaucrates de terrain dans la mise en œuvre des politiques publiques et illustre également les défis qu'ils peuvent rencontrer lorsqu'ils sont confrontés à des réformes qui nécessitent un changement significatif dans la manière dont les services sont fournis.

La promotion de l'État social actif repose sur l'idée que l'aide sociale n'est pas simplement une prestation passive fournie par l'État, mais qu'elle doit aussi encourager et faciliter la réintégration active des bénéficiaires dans la société, et en particulier sur le marché du travail. Cette approche souligne l'importance de la responsabilité individuelle et de la participation active des bénéficiaires dans leur processus de réintégration. Dans le cadre de cette réforme en Californie, par exemple, les bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale étaient encouragés à chercher un emploi, à suivre une formation ou à participer à d'autres activités qui pourraient améliorer leurs chances de trouver un emploi. En échange de cette participation active, ils continuaient de recevoir une aide financière de l'État. Cependant, la mise en œuvre réussie de cette approche dépend largement des bureaucrates de terrain, tels que les travailleurs sociaux, qui sont chargés d'accompagner les bénéficiaires dans ce processus, de surveiller leur progrès et de les aider à surmonter les obstacles qu'ils peuvent rencontrer.

Les bureaucrates de terrain, ceux qui travaillent directement avec les bénéficiaires, sont souvent les premiers et les plus importants interprètes des politiques. Leur compréhension, leur interprétation et leur application des règles peuvent avoir un impact significatif sur la manière dont une politique est mise en œuvre en pratique. Dans le cas de la réforme de la politique sociale en Californie, ces bureaucrates de terrain étaient les travailleurs sociaux travaillant dans des agences sociales décentralisées. Pour que la réforme soit un succès, il était essentiel que ces travailleurs sociaux comprennent pleinement l'intention de la politique, la manière dont elle devrait être mise en œuvre et le rôle qu'ils joueraient dans ce processus. C'est pourquoi un programme de formation détaillé a été mis en place pour ces travailleurs sociaux. Ce programme visait non seulement à leur fournir les connaissances nécessaires pour comprendre et mettre en œuvre la réforme, mais aussi à les sensibiliser à l'importance de leur rôle et à les motiver à travailler de manière proactive pour aider les bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale à réintégrer le marché du travail. Cet exemple illustre clairement l'importance du rôle des bureaucrates de terrain dans la mise en œuvre des politiques publiques et montre comment des efforts ciblés pour les former et les soutenir peuvent contribuer au succès d'une réforme.

L'utilisation d'approches ethnographiques, comme l'observation directe des interactions entre les bureaucrates de terrain et les bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale, permet aux chercheurs d'obtenir une vue détaillée de la façon dont la politique est appliquée sur le terrain. Cela inclut non seulement la façon dont les bureaucrates de terrain interprètent et appliquent les règles, mais aussi comment ils interagissent avec les bénéficiaires, comment ils gèrent les situations difficiles ou ambiguës, et quels facteurs influencent leur comportement. Les chercheurs peuvent alors utiliser ces informations pour identifier les éventuels problèmes ou obstacles à la mise en œuvre efficace de la politique, et pour formuler des recommandations sur la façon dont ces problèmes pourraient être résolus. De plus, le fait d'effectuer des entretiens avec les bureaucrates de terrain après les observations peut également être très utile. Ces entretiens peuvent aider à clarifier et à approfondir les observations faites, et peuvent fournir une occasion de discuter des problèmes ou des préoccupations que les bureaucrates de terrain pourraient avoir. Ils peuvent également aider à comprendre les motivations, les attitudes et les perceptions des bureaucrates de terrain, qui peuvent toutes avoir un impact sur la manière dont ils mettent en œuvre la politique.

La déception fut grande lorsqu'ils ont réalisé, au fil de leurs observations, que les bureaucrates de terrain n'avaient jamais fait référence au principe central de la réforme, à savoir "il est toujours bénéfique de travailler". En dépit des efforts consacrés à la formation et à la sensibilisation de ces acteurs clés, la réforme semblait n'avoir eu aucun impact réel. Il semblait que malgré tous les efforts déployés, rien n'avait véritablement changé sur le terrain.

C'est une déception courante lors de la mise en œuvre de politiques publiques. Même avec une formation et une sensibilisation adéquates, il peut être difficile de changer les comportements et les routines bien ancrés des bureaucrates de terrain. C'est d'autant plus le cas lorsque les nouvelles directives ou politiques exigent un changement majeur dans la façon dont les choses sont faites.

Il y a plusieurs raisons possibles à ce phénomène :

- Résistance au changement : Comme pour toute organisation ou individu, il peut y avoir une résistance naturelle au changement. Les bureaucrates de terrain peuvent se sentir plus à l'aise avec les méthodes et les procédures existantes et peuvent être réticents à changer leurs habitudes de travail.

- Manque de compréhension ou de soutien : Malgré la formation, les bureaucrates de terrain peuvent ne pas comprendre pleinement la nouvelle politique ou ne pas être convaincus de ses avantages. Ils peuvent également manquer de soutien ou de ressources pour mettre en œuvre le changement.

- Conflits de valeurs ou de priorités : Les bureaucrates de terrain peuvent ne pas être d'accord avec les principes ou les objectifs de la nouvelle politique. Par exemple, dans le cas de la réforme en Californie, ils peuvent estimer que les bénéficiaires de l'aide sociale ont besoin de plus de soutien et de compréhension, plutôt que d'être poussés à travailler.

- Charge de travail et stress : La mise en œuvre d'une nouvelle politique peut entraîner une augmentation de la charge de travail et du stress pour les bureaucrates de terrain, ce qui peut les dissuader de l'adopter.

Cet exemple souligne l'importance de la coopération de tous les acteurs dans la mise en œuvre d'une politique publique, y compris les acteurs considérés comme étant au bas de l'échelle hiérarchique. Prenons l'exemple d'une politique d'éducation : sa réussite dépend grandement de l'engagement des acteurs de terrain tels que les enseignants. Si ces derniers résistent ou s'opposent à la mise en œuvre d'une réforme, ils ont le pouvoir de bloquer son application, et ce, malgré les décisions prises en amont au niveau du parlement ou de l'administration supérieure. C'est donc dire que la réussite d'une politique publique peut être compromise si les bureaucrates de terrain n'adhèrent pas à sa vision et à ses objectifs.

Annnexes

References

- ↑ Derthick, M. (1974). Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It's Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation of Ruined Hopes. By Jeffrey L. Pressman and Aaron Wildavsky (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. pp. xviii, 182. $7.50.). American Political Science Review, 68(3), 1336-1337. doi:10.2307/1959201

- ↑ LIPSKY, MICHAEL. Street Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. Russell Sage Foundation, 1980. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610447713.