Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

The 18th century marked the advent of a revolutionary era in the course of human history, indelibly shaping the future of Europe and, by extension, the world. Anchored between ancient traditions and modern visions, this century was a crossroads of contrasts and contradictions. At the beginning of the century, Europe was still largely a mosaic of agrarian societies, governed by ancestral feudal structures and a hereditary nobility holding power and privileges. Daily life was punctuated by agricultural cycles and the vast majority of the population lived in small rural communities, dependent on the land for their livelihood. However, the seeds of change were already present beneath the surface, ready to blossom.

As the century progressed, a wind of change blew across the continent. The influence of the Enlightenment philosophers, who advocated reason, individual freedom and scepticism towards traditional authority, began to challenge the established order. Literary salons, cafés and newspapers became forums for progressive ideas, fuelling the desire for social, economic and political reform. Europe's economic dynamic was also undergoing a radical transformation. The introduction of new farming methods and crop rotation improved land yields, encouraging population growth and increasing social mobility. International trade intensified thanks to advances in navigation and colonial expansion, and cities such as Amsterdam, London and Paris became buzzing centres of commerce and finance. The Industrial Revolution, although in its infancy, was beginning to show its face by the end of the 18th century. Technological innovations, particularly in textiles, transformed production methods and shifted the focus of the economy from rural areas to the expanding urban cities. Water power and later the steam engine revolutionised industry and transport, paving the way for mass production and a more industrialised society.

Yet this period of growth and expansion also witnessed growing inequality. Mechanisation often led to unemployment among manual workers, and living conditions in industrialising cities were frequently miserable. The wealth generated by international trade and the colonisation of the Americas was not evenly distributed, and the benefits of progress were often tempered by exploitation and injustice. Political upheavals, such as the French Revolution and the American War of Independence, demonstrated the potential and desire for representative government, undermining the foundations of absolute monarchy and laying the foundations for modern republics. The notion of the nation state began to emerge, redefining identity and sovereignty. The end of the 18th century was therefore a period of dramatic transition, as the old world gradually gave way to new structures and ideologies. The imprint of these transformations shaped European societies and established the premises of the contemporary world, inaugurating debates that continue to resonate in our society today.

Notions of structure and economic conditions

In the jargon of the economic and social sciences, the term 'structure' refers to the enduring features and institutions that make up and define the way an economy functions. These structural elements include laws, regulations, social norms, infrastructures, financial and political institutions, as well as patterns of ownership and resource allocation. Structural elements are considered stable because they are woven into the fabric of society and the economy and do not change quickly or easily. They serve as the foundation for economic activities and are crucial to understanding how and why an economy works the way it does.

The concept of equilibrium in economics, often associated with the economist Léon Walras, is a theoretical state in which resources are allocated in the most efficient way possible, i.e. supply meets demand at a price that satisfies both producers and consumers. In such a system, no economic actor has the incentive to change his or her production, consumption or exchange strategy, because the existing conditions maximise utility for all within the given constraints. In reality, however, economies are rarely, if ever, in a state of perfect equilibrium. Structural changes, such as those observed during the eighteenth century with the transition to more industrialised and capitalist economic systems, involve a dynamic process in which economic structures evolve and adapt. This process can be disrupted by technological innovations, scientific discoveries, conflicts, government policies, social movements or economic crises, all of which can lead to imbalances and require structural adjustments. Economists study these structural changes to understand how economies develop and respond to various disturbances, and to inform policies that aim to promote stability, growth, and economic well-being.

In the context of capitalism, structure can be thought of as the set of regulatory frameworks, institutions, business networks, markets and cultural practices that shape and sustain economic activity. This structure is essential for the proper functioning of capitalism, which is based on the principles of private ownership, capital accumulation and competitive markets for the distribution of goods and services. The structural integrity of a capitalist system, i.e. the robustness and resilience of its components and institutions, is crucial to its stability and ability to regulate itself. In such a system, each element - be it a financial institution, a company, a consumer or a government policy - must function efficiently and autonomously, while being consistent with the system as a whole. Capitalism is theoretically designed to be a self-regulating system where the interaction of market forces - principally supply and demand - leads to economic equilibrium. For example, if demand for a product increases, the price tends to rise, which means a greater incentive for producers to produce more of that product, which should eventually restore the balance between supply and demand. However, economic history shows that markets and capitalist systems are not always self-correcting and can sometimes be subject to persistent imbalances, such as speculative bubbles, financial crises or growing inequality. In these cases, elements of the system may not adapt effectively or quickly, leading to instability that may require external intervention, such as government regulation or monetary and fiscal policies, to restore stability. So, although capitalism tends towards some form of equilibrium thanks to the flexibility and adaptability of its structures, the reality of how it works can be much more complex and often requires careful management and regulation to avoid dysfunction.

The Ancien Régime structure

The economy of the Ancien Régime, which prevailed in Europe until the end of the 18th century and is particularly associated with pre-revolutionary France, was mainly dominated by agriculture. This agrarian predominance was strongly marked by cereal monoculture, with wheat as the standard of production. This specialisation reflected the basic food needs of the time, climatic and environmental conditions, and farming practices rooted in tradition. Land was the main source of wealth and the symbol of social status, resulting in a rigid socio-economic structure that was reluctant to change and adopt new farming methods. The productivity of Ancien Régime agriculture was low. Land yields were limited by the use of traditional farming techniques and a glaring lack of innovation. Three-year crop rotation and dependence on the vagaries of nature, in the absence of advanced technology, limited agricultural efficiency. Investment in technologies that could improve the situation was rare, hampered by a combination of lack of knowledge, lack of capital, and a social system that did not value agricultural entrepreneurship.

In terms of demographics, population balance was maintained by social customs such as late marriage and a high rate of permanent celibacy, practices that were particularly widespread in north-western Europe. These customs, combined with high infant mortality and recurring periods of famine or pandemic, naturally regulated population growth despite meagre agricultural production.

The development of means of transport and communication was also very limited, resulting in an economy characterised by the existence of micro-markets. High transport costs made it prohibitively expensive to trade goods over long distances, with the exception of high-value-added products such as watches produced in Geneva. These luxury items, aimed at a wealthy clientele, could absorb the transport costs without compromising their competitiveness on distant markets.

Finally, industrial and craft production under the Ancien Régime was mainly focused on the manufacture of everyday consumer goods, dictated by the "law of consumer urgency", i.e. the necessities of eating, drinking and dressing. Industries, particularly textiles, were often small-scale, spread across the country and tightly controlled by guilds that restricted competition and innovation. This limited production was consistent with the immediate needs and economic capacities of the majority of the population at the time.

This set of characteristics defined an economy and society where the status quo prevailed, leaving little room for innovation and dynamic change. The rigidity of the structures of the Ancien Régime therefore played a part in delaying the entry of countries like France into the Industrial Revolution, compared with England, where social and economic reforms paved the way for more rapid modernisation.

The Economic Situation: Analysis and Impact

Economic and social history is marked by long-term cycles of growth and recession, crises and periods of recovery. Changing socio-economic structures is an arduous process, not least because it involves upsetting the balance of systems that have been in place for centuries. However, these structures are not set in stone and reflect the constant dynamics of a society that is constantly evolving, even if the ways in which this evolution occurs can be subtle and complex to discern.

Crises are often the result of an accumulation of tensions within a system that has enjoyed a long period of apparent stability. These tensions can be exacerbated by catastrophic events that force a reorganisation of the existing system. Crises can also lead to greater social polarisation, with more distinct winners and losers as society adapts and reacts to change.

The image of "rising and falling, like successive tides" is a powerful metaphor for these economic and social cycles. There are periods of demographic or economic growth that seem to be reversed or cancelled out by periods of crisis or depression. These 'ebbs and flows' are characteristic of human history, and studying them offers valuable insights into the forces that shape societies over time. It also suggests an inherent resilience in social systems, which although facing regular 'breakdowns', are able to recover and rise again, although never quite in the same way as before. Each cycle brings with it changes, adaptations and sometimes profound transformations of existing structures.

The Dawn of Economic Growth

The 18th century was marked by a demographic expansion unprecedented in European history. The population of the United Kingdom, for example, grew impressively, from around 5.5 million at the beginning of the century to 9 million at the dawn of the 19th century, an increase of almost 64%. This demographic growth was one of the most remarkable of the period, reflecting improved living conditions and technological and agricultural progress. France was no exception, with its population rising from 22 to 29 million, an increase of 32%. This rate of growth, while less spectacular than that of the UK, nonetheless reflects a significant change in French demographics, benefiting also from improvements in agriculture and relative political stability. On the European continent as a whole, the overall population grew by around 58%, a remarkable figure given that Europe had been subject to recurring demographic crises in previous centuries. Unlike previous periods, this growth was not followed by major demographic crises, such as famines or large-scale epidemics, which could have significantly reduced the number of inhabitants.

These demographic changes are all the more remarkable in that they have occurred without the traditional mortality "corrections" that have historically accompanied population increases. There are many reasons for this phenomenon: improved agricultural production thanks to the Agricultural Revolution, advances in public health, and the start of the Industrial Revolution, which created new jobs and encouraged urbanisation. These population increases played a crucial role in the economic development and social transformations of the period, providing an abundant workforce for fledgling industries and stimulating demand for manufactured goods, thus laying the foundations of modern European societies.

The exceptional demographic growth of 18th-century Europe can be attributed to a number of interdependent factors that together altered the continent's socio-economic landscape. Agricultural innovation was a key driver of this growth. The introduction of crops from different continents diversified and enriched the European diet. Maize and rice, imported from Latin America and Asia respectively, transformed agriculture in southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy, which adapted to intensive rice cultivation. In northern and western Europe, the potato played a similar role. Its rapid spread over the course of the century increased calorie intake compared with traditional cereals, and it became the staple food of the working classes. Trade also made a significant contribution to prosperity and population growth, especially in the British Isles. The United Kingdom, in particular, built up a robust merchant fleet, establishing itself as the "world's trader". The development of the Industrial Revolution enabled the mass production of goods that were then distributed across the continent. In 1740, when a bad harvest hit Western Europe, England was able to avoid a mortality crisis by importing wheat from Eastern Europe thanks to its fleet, while France, less well connected by sea, suffered the consequences of this shortage. The Netherlands also enjoyed considerable commercial power thanks to its merchant navy. Finally, the change in economic structures had a profound impact. The transition from the domestic system, where production took place in the home, to proto-industrialisation created new economic dynamics. Proto-industrialisation, which involved an increase in small-scale, often rural production prior to full industrialisation, laid the foundations for an industrial revolution that would transform local economies into economies of scale, amplifying the capacity to produce and distribute goods. These factors, combined with advances in public health and better management of food resources, not only enabled Europe's population to grow substantially, but also paved the way for a future in which industrialisation and world trade would become the pillars of the global economy.

The Domestic System or Verlagsystem: Foundations and Mechanisms

The Verlagsystem was a key precursor to industrialisation in Europe. Characteristic of certain regions of Germany and other parts of Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries, this system marked an intermediate stage between artisanal work and the industrial factory production that would later predominate. In this system, the Verleger, often a wealthy entrepreneur or merchant, played a central role. He distributed the necessary raw materials to the workers - generally craftsmen or peasants looking to supplement their income. These workers, using the space of their own homes or small local workshops, concentrated on producing goods to the specifications provided by the Verleger. They were paid on a piecework basis, rather than a fixed wage, which encouraged them to be as productive as possible. Once the goods had been produced, the Verleger collected them, took care of the finishing if necessary, and sold them on the local market or for export. The Verlagsystem facilitated the expansion of trade and allowed greater specialisation of work. It was particularly dominant in the textile industries, where items such as garments, fabrics and ribbons were mass-produced.

This system had several advantages at the time: it offered considerable flexibility in terms of labour, allowing workers to adapt to seasonal demand and market fluctuations. It also allowed entrepreneurs to minimise fixed costs, such as those associated with maintaining a large factory, and to bypass some of the restrictions of the guilds, which strictly controlled production and trade in the towns. However, the Verlagsystem was not without its flaws. Workers, tied to the piece, could find themselves in a situation of virtual dependence on the Verleger, and were vulnerable to economic pressures such as falling prices for finished goods or rising costs for raw materials. With the advent of the industrial revolution and the development of factory production, the Verlagsystem gradually declined, as new machines enabled faster, more efficient production on a larger scale. Nevertheless, it was a crucial step in Europe's transition to an industrial economy and laid the foundations for some modern production principles.

The domestic system was particularly prevalent in the textile industry in Europe from the 16th century onwards. It was a method of organising work that preceded industrialisation and involved dispersed production in the home rather than centralised production in a factory or workshop. Under this system, raw materials were supplied to homeworkers, who were often farmers or family members looking to earn extra income. These workers used simple tools to spin wool or cotton, and to weave cloth or other textile goods. The process was usually coordinated by entrepreneurs or merchants who supplied the raw materials and, after production, collected the finished goods to sell on the market. This method of working had advantages for both merchants and workers. Merchants could bypass the restrictions of the urban guilds, which strictly regulated trade and crafts in the towns. For workers, this meant they could work from home, which was particularly advantageous for rural families, who could supplement their farming income with textile production. However, the domestic system had its limits. Production was often slow and the quantities produced relatively small. What's more, the quality of the goods could vary considerably. Over time, these disadvantages became more apparent, particularly when the industrial revolution introduced more efficient machinery and factory production. The invention of machines such as the power loom and the spinning machine greatly increased productivity, leading to the obsolescence of the domestic system and the rise of factories. The domestic system was therefore a significant stage in the evolution of industrial production, serving as a bridge between traditional craftwork and the large-scale production methods that followed it. It witnessed the first stages of industrial capitalism and the emergence of a more modern market economy.

The domestic system, which was widespread before the advent of industrialisation, was characterised by its decentralised production structure and the dynamic between craftsmen and merchants. At the heart of this system were the peasants who, outside the demanding seasons of agricultural work such as sowing and harvesting, devoted their time to craft production, particularly in the textile sector. This model offered workers a way of supplementing their often insufficient income, while guaranteeing them a degree of flexibility in their employment. In return, merchants benefited from an affordable and adaptable workforce. Merchants also played a pivotal role in the economic organisation of the system. Not only did they supply craftsmen with the raw materials they needed, but they were also responsible for distributing tools and managing orders. His ability to centralise the purchase and distribution of resources enabled him to reduce transport costs and exercise control over the production and sales chain. What's more, by regulating the pace of work according to orders, the merchant adapted supply to demand, a practice that heralded the principles of flexibility in modern capitalism. Overall, the domestic system was marked by the dominant figure of the merchant-entrepreneur, who orchestrated the production and marketing of finished products, relying on intermittent farm labour. This system was to evolve gradually, paving the way for more centralised production methods and the industrial revolution that would follow.

In the domestic system that prevailed before the Industrial Revolution, the role of the peasant was characterised by a high degree of economic dependence. This depended on a number of factors. Firstly, the peasant's life was governed by the seasons and agricultural cycles, making his income uncertain and variable. As a result, craft production, particularly in the textile sector, provided a necessary income supplement to make up for the shortfall in earnings from farming. The nature of this dependence was twofold: not only did the peasant depend on agriculture for his main livelihood, but he was also dependent on the additional income provided by craft work. Secondly, the relationship between the peasant and the merchant was asymmetrical. The merchant, who controlled the distribution of raw materials and the marketing of finished products, had considerable influence over the peasant's working conditions. By supplying the tools and placing the orders, the merchant dictated the work flow and indirectly determined the peasant's level of income. This dependence was exacerbated by the fact that the peasant himself did not have the means to market his products on a significant scale, forcing him to accept the terms dictated by the merchant. The peasant's dependence on the merchant was reinforced by his precarious economic status. With little opportunity to negotiate or alter the conditions of their craft work, farmers were vulnerable to fluctuations in demand and the decisions of the merchant. This situation lasted until the advent of industrialisation, which radically transformed production methods and economic relations within society.

The textile guilds, strong institutions from the Middle Ages to the modern period, played an essential role in regulating the production and quality of goods, as well as in the economic and social protection of their members. When the decentralised production system, known as the Verlagsystem or putting-out system, began to develop, it presented an alternative model in which merchants outsourced work to craftsmen and peasants working in their own homes. This new model created significant tensions with traditional guilds for a number of reasons. Corporations were based on strict rules governing the training, production and sale of goods. They imposed high standards of quality and guaranteed a certain standard of living for their members, while limiting competition to protect local markets. The Verlagsystem, however, operated outside these regulations. Merchants were able to bypass the constraints of the guilds, offering products at lower cost and often on a much larger scale. For the guilds, this form of production represented unfair competition as it did not abide by the same rules and could threaten the economic monopoly they maintained over the production and sale of textiles. As a result, the corporations often sought to limit or prohibit the activities of the Verlagsystem in order to preserve their own practices and advantages. This opposition sometimes led to open conflict and attempts to introduce stricter regulations to curb the expansion of the system. Despite this, the Verlagsystem gained ground, particularly where corporations were less powerful or less present, foreshadowing the economic and social changes that were to characterise the Industrial Revolution.

The organisation of production that emerged with the domestic system offered an innovation in the management of agricultural labour. The system enabled peasants to take advantage of their slack periods by working part-time for merchants or manufacturers. The peasant thus became a cheap and flexible workforce for the merchant, who could adapt to fluctuations in demand without the constraints of a full-time commitment. Despite this innovation, the domestic system remained a relatively marginal phenomenon and did not have the transformative impact that capitalist merchants might have expected. The latter held the capital needed to buy the raw materials and pay the peasants for their labour, often at the lowest price, before selling the finished products on the market. This represented an early form of commercial capitalism, but this economic model came up against a major obstacle: weak demand. The social and economic reality of the time was that of a "society of mass misery", where famine was commonplace and consumption was limited to the bare necessities. Clothes, for example, were bought to last and were patched and reused rather than replaced. Mass consumption required a level of purchasing power that was simply not present in the majority of the population, with the exception of a few minority groups such as the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the clergy. So, despite its innovative aspects, the domestic system did not grow significantly, partly because of this weak demand and limited overall purchasing power. This helped to keep the economic system in a state of "gridlock", where technological and organisational progress alone could not trigger wider economic development without a concomitant increase in market demand.

The emergence of proto-industrialisation

Proto-industry, which developed mainly before the Industrial Revolution, was an intermediate stage between the traditional agricultural economy and the industrial economy. This form of economic organisation emerged in Europe, particularly in rural areas where farmers sought to supplement their income outside the planting and harvesting seasons. Under this system, production was not centralised, as it was in the factories of the later industrial era, but dispersed across numerous small workshops or homes. Craftsmen and small-scale producers, who often worked in families, specialised in the production of specific goods such as textiles, pottery or metals. These goods were then collected by merchants, who were responsible for distributing them to wider markets, often well beyond local ones.

Proto-industrialisation implied a mixed economy in which agriculture remained the main activity, but in which the production of manufactured goods played an increasing role. This period was marked by a still rudimentary division of labour and limited use of specialised machinery, but it nonetheless laid the foundations for the subsequent development of industrialisation, notably by accustoming part of the population to work outside agriculture, stimulating the development of skills in the production of goods and promoting the accumulation of capital needed to finance larger, more technologically advanced businesses.

Franklin Mendels (1972): Thesis on Flanders in the 18th Century

Franklin Mendels conceptualised the term 'proto-industrialisation' to describe the evolutionary process that took place in the European countryside, particularly in Flanders, during the 18th century, foreshadowing the Industrial Revolution. His thesis highlights the coexistence of agriculture with the small-scale production of manufactured goods in peasant households. This dual economic activity enabled rural families to increase their income and reduce their vulnerability to agricultural hazards. According to Mendels, proto-industrialisation was characterised by a scattered distribution of manufactured production, often carried out in small workshops or within households, rather than in large, concentrated factories. Farmers were often dependent on local merchants who supplied the raw materials and took care of marketing the finished products. This system stimulated productivity and promoted efficiency in the production of manufactured goods, which in turn boosted the economy of the regions concerned. This period also saw significant changes in family and social structures. Farming families adapted by adopting economic strategies that combined agriculture and manufacturing. This had the effect of familiarising the workforce with manufacturing activities and weaving distribution networks for the goods produced, thereby facilitating the accumulation of capital. Proto-industrialisation therefore not only changed the economic landscape of these regions, but also had an impact on their demography, social mobility and family relations, laying the foundations for modern industrial societies.

At the end of the 17th century, population growth in Europe led to significant changes in the social composition of the countryside. This demographic growth led to the distinction of two main groups within the rural population. On the one hand, there were the landless peasants. This group was made up of people who did not own any agricultural plots and who often depended on seasonal or day labour to survive. These people were particularly vulnerable to economic fluctuations and poor harvests. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution, they were to become an essential workforce, often described as the 'reserve army' of industrial capitalism, as they were available to work in the new factories and plants due to their lack of ties to the land. On the other hand, there were the peasants who, faced with demographic pressure and the increasing scarcity of available land, sought alternative sources of income. These peasants began to turn to non-agricultural activities, such as craft production or work at home within the framework of systems such as the domestic system or proto-industrialisation. In this way, they contributed to the economic diversification of the countryside and to preparing rural populations for the industrial transformations to come. These dynamics led to a socio-economic reorganisation of the countryside, with an impact on the traditional structures of agriculture and a growing involvement of rural areas in the wider economic circuits of trade and manufacturing production.

Characteristics of the Proto-industry ("Putting-Out System")

The eighteenth century was a period of profound economic transformation in Europe, and particularly in regions such as Flanders. The economic historian Franklin Mendels, in his landmark thesis on eighteenth-century Flanders, identified several key elements that characterised proto-industry, a system that paved the way for the Industrial Revolution. One of Mendels' most surprising findings is that, unlike earlier periods in history, population growth in the eighteenth century was mainly centred in the countryside rather than the towns. This marks a reversal of historical demographic trends in which cities were usually the engines of growth. This expansion of the rural population led to a surplus of labour available for new forms of production. Furthermore, Mendels identified that the basic economic unit during this period was neither the town nor the village, but rather the household. The household functioned as the nucleus of production and reproduction. Rather than relying solely on agriculture, rural families diversified their activities by taking part in proto-industrial production, often as part of the domestic system. These households produced goods at home, such as textiles, for merchants or entrepreneurs who supplied them with raw materials and collected the finished products for sale. This economic structure allowed greater flexibility and adaptability to fluctuations in demand and the seasons, contributing to sustained economic growth that would eventually lead to the Industrial Revolution. Protoindustry was therefore a key factor in economic growth in the 18th century, preparing rural populations for the major changes that were to come with industrialisation.

Franklin Mendels' meticulous studies of eighteenth-century Flanders offer a detailed insight into the economic and social dynamics of rural Western Europe. By analysing the archives of some 5,000 households, Mendels was able to identify three distinct social groups, whose growth reflected the tensions and changes of the time. The landless peasants were a growing group, a direct consequence of population growth that outstripped the capacity of the land to provide for everyone. With inheritance practices dividing the land between several heirs, many farms became unviable and went bankrupt. These farmers were under pressure from demographic and economic imperatives, sometimes leading to bankruptcy. For some, working for large landowners was an option, while others would become what Marx called "the reserve army of capitalism", ready to join the workforce of nascent industry in their desperate search for work. A second group was made up of peasants who chose to emigrate to avoid the excessive subdivision of their family plot of land and the consequent dilution of income. These peasants sought economic opportunities in town or even abroad, often on a seasonal basis, establishing migration patterns that became common in the eighteenth century. Finally, there were those who remained attached to their land but were forced to innovate in order to survive. This group adopted proto-industry, combining agricultural work with small-scale industrial production, often in the home. By integrating these new forms of production, they managed to maintain their rural lifestyle while generating the additional income needed to support their families. These three social groups, observed by Mendels, illustrate the complexity and diversity of the responses to the economic and demographic challenges of the time, and their central role in the transformation of pre-industrial rural society.

Proto-industry represents an intermediate phase of economic development that took place mainly in the countryside, characterised by a system of home-based work. It is a form of rural craft industry that remains largely invisible in traditional economic statistics, as it takes place in the interstices of agricultural time. The workers, often peasants, use the periods when farming requires less attention to engage in production activities such as spinning or weaving, enabling them to diversify their sources of income. The proto-industrial system is perfectly compatible with the seasonal rhythm of farming, as it capitalises on the slack periods in agriculture. In this way, farmers can continue to meet their food needs through agriculture while increasing their income through proto-industrial activities. In the event of a poor harvest and rising wheat prices, the additional income generated by the proto-industry provides economic security, enabling them to buy food. Conversely, if a crisis hits the textile sector, agricultural harvests can provide a guarantee against famine. The duality of this economy therefore offers a degree of resilience in the face of crises, since the survival of farmers does not depend exclusively on a single sector. Only the misfortune of a simultaneous crisis in the agricultural and proto-industrial sectors could threaten their livelihoods, a rare occurrence historically. This demonstrates the strength of a diversified economic system, even at the microeconomic level of the rural household.

The introduction of a second source of income marked a significant turning point in the lives of farmers. Although poverty continued to be widespread and the majority of people lived on modest means, the ability to generate additional income through proto-industry helped to reduce the precariousness of their existence. This diversification of income has led to greater economic security, reducing farmers' vulnerability to seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of agriculture. So, even if the overall standard of living did not rise spectacularly, the impact on the security and stability of rural households was substantial. Families were better able to cope with years of poor harvests or periods of rising food prices. What's more, this greater security could translate into a certain improvement in social well-being. With the extra income, families potentially had access to goods and services they would not otherwise have been able to afford, such as better clothes, tools, or even education for their children. In short, proto-industry played a fundamental role in improving the condition of peasants by providing them with a safety net that went beyond subsistence and paved the way for the social and economic changes of the Industrial Revolution.

Triangular Trade: An Overview

The integration of proto-industry into world trade marked a significant transformation of the global economy. This system, also known as the putting-out system or domesticity system, paved the way for rural producers to participate fully in the market economy by manufacturing goods for export. This development has had a series of interconnected consequences. Proto-industry led to a significant increase in demand for manufactured goods, partly thanks to the establishment of triangular trade. The latter refers to a trade circuit between Europe, Africa and the Americas, where goods produced in Europe were exchanged for slaves in Africa, who were then sold in the Americas. Raw materials from the colonies were brought back to Europe to be processed by the proto-industry.

This trade fuelled the accumulation of capital in Europe, which subsequently financed the Industrial Revolution. In addition, the expansion of markets for proto-industrial goods beyond local borders fostered the emergence of a more integrated, globalised market economy. Economic structures began to change, as proto-industry paved the way for the Industrial Revolution by directing producers to produce for the market and not just for personal subsistence. However, it is essential to recognise that the triangular trade also included the slave trade, a profoundly inhumane aspect of this historical period. Economic advances sometimes came at the cost of great human suffering, and although the economy prospered, it did so with irreparable damage to many lives, the impact of which is still felt today.

Proto-industry, often confused with the domestic system, differs from the latter in its scale and economic impact. Proto-industry affected a large number of farmers, with few agricultural regions spared by the phenomenon. This widespread diffusion is mainly due to the transition of rural producers from local micro-markets to a global economy, enabling them to export their products. The export of goods such as textiles, weapons and even items as basic as nails has considerably increased global demand and stimulated economic growth. This expansion of markets was also the driving force behind triangular trade. This system saw the products of proto-industry in Europe traded for slaves in Africa, who were then transported to the Americas to work in plantation economies producing cotton, sugar, coffee and cocoa, which were eventually exported to Europe. This trade flow not only contributed to an increase in demand for proto-industrial goods, but also led to an increase in shipbuilding work, a sector that provided employment for millions of peasants, reducing transport costs and promoting sustained economic growth. However, it is important to remember that the triangular trade was based on slavery, a deeply tragic and inhumane system, the after-effects of which are still present in modern society. The economic growth it generated is inseparable from these painful historical realities.

The relationship between population growth and proto-industry in the 18th century is a complex question of cause and effect that has been widely debated by economic historians. On the one hand, population growth can be seen as an incentive to seek new forms of income, leading to the development of proto-industry. With a growing population, particularly in the countryside, land is becoming insufficient to meet everyone's needs, forcing farmers to find additional sources of income, such as proto-industrial work that can be carried out at home and does not require extensive travel. On the other hand, proto-industry itself has been able to encourage demographic growth by improving the standard of living of rural families and enabling them to provide better for their children. Access to additional off-farm income has probably reduced mortality rates and enabled families to support more children into adulthood. In addition, as incomes increased, populations were better nourished and more resistant to disease, which could also contribute to population growth. Proto-industry thus represents a transitional phase between traditional economies, based on small-scale agriculture and crafts, and the modern economy characterised by industrialisation and the specialisation of labour. It has enabled the integration of rural economies into international markets, leading to an increase in production and a diversification of sources of income. This has had the effect of boosting local economies and integrating them into the expanding global trade network.

The demographic effects

Impact on Mortality

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, Europe underwent a significant demographic transformation, characterised by a fall in mortality, thanks in part to a series of improvements and changes in society. Advances in agriculture led to increased food production, reducing the risk of famine. At the same time, advances in hygiene and public health initiatives have begun to reduce the spread of infectious diseases. Although major advances in medicine would not come until the end of the 19th century, some early discoveries had already had a positive impact on health. In addition, proto-industrialisation created additional income opportunities outside agriculture, enabling families to better withstand periods of poor harvests and improve their standard of living, including their access to quality food and healthcare. This era also saw a change in economic and social structure, with families now able to afford to marry earlier and bring up more children thanks to greater economic security. Home-based industrial work, such as textiles, offered additional financial security which, combined with farming, provided a more stable and diversified income. This helped to erode the old demographic regime where marriage was often delayed for lack of economic resources. The convergence of these factors therefore played a role in reducing mortality crises, leading to sustained demographic growth and a transformation of mentalities and lifestyles. Proto-industrialisation, by providing additional income and economic stability, was a key element in this transition, although its influence varied greatly from region to region.

Influence on Age at Marriage and Fertility

Proto-industrialisation had an impact on the social and economic structure of rural societies, and one of these effects was a lowering of the age at marriage. Before this period, many small farmers had to delay marriage until they could afford to support a family, as their resources were limited to what their land could produce. With the advent of proto-industrialisation, these small farmers were able to supplement their income with home-based industrial activities, such as weaving, which became increasingly in demand as the market expanded. This new source of income made marriage more accessible at a younger age, as couples could count on additional income to support themselves. What's more, in this new economic model, children represented an additional workforce that could contribute to the family income from an early age. They could, for example, work on the looms at home. This meant that families had an economic incentive to have more children, and that children could contribute economically long before they reached adulthood. This dynamic reinforced the economic viability of marriage and the extended family, allowing an increase in the birth rate and contributing to accelerated population growth. This demographic transition had profound repercussions on society, eventually leading to structural changes that paved the way for full industrialisation and economic modernisation.

The phenomenon of proto-industrialisation had varying effects on marital behaviour and fertility, depending on the region. In areas where proto-industrialisation provided significant additional income, people began to marry earlier and fertility increased accordingly. The ability to supplement agricultural incomes with those from home-based industrial work reduced the economic barriers to early marriage, as families could feed more mouths and support larger households. However, in other regions, economic prudence prevailed and peasants tended to postpone marriage until they had accumulated sufficient resources to become landowners. The acquisition of land was often seen as a guarantee of economic security, and peasants preferred to postpone marriage and the creation of a family until they could ensure a certain degree of material stability. This regional difference in marriage behaviour reflects the diversity of economic strategies and cultural values that influenced peasants' decisions. While proto-industrialisation offered new opportunities, responses to these opportunities were far from uniform and were often shaped by local conditions, traditions and individual aspirations.

Transforming Human Relationships: Body and Environment

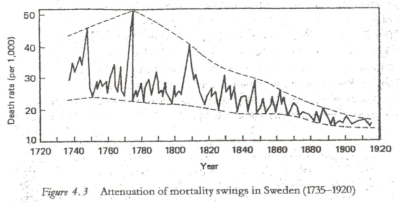

The graph shows the mortality rate per 1,000 individuals on the y-axis and the years from 1720 to 1920 on the x-axis. A clear trend can be seen on the graph: the mortality rate, which shows wide fluctuations with high peaks in the early years (particularly around 1750 and just before 1800), gradually flattens out over time, with the peaks becoming less pronounced and the overall mortality rate falling. The dotted line represents a trend line indicating the general downward trajectory of the mortality rate over this two-century period. This visual representation suggests that, over time, the instances and severity of mortality crises (such as epidemics, famines and wars) have decreased, due to improvements in public health, medicine, living conditions and changes in social structures.

Evolution of the Perception of Death

The change in the perception of death in the West between the 16th and 18th centuries reflects a profound transformation in mentality and culture. In the 16th and 17th centuries, high mortality rates and frequent epidemics made death a constant and familiar presence in daily life. People were used to coexisting with death, both as a community and as individuals. Cemeteries were often located in the heart of villages or towns, and the dead were an integral part of the community, as evidenced by rituals and commemorations. However, in the 18th century, particularly with advances in medicine, hygiene and social organisation, mortality began to decline, and with it, the omnipresent presence of death. This reduction in daily mortality led to a transformation in the perception of death. It was no longer perceived as a constant companion, but rather as a tragic and exceptional event. Cemeteries were moved outside inhabited areas, signifying a physical and symbolic separation between the living and the dead. This "distancing" of death coincides with what many historians and sociologists consider to be the beginning of Western modernity. Attitudes turned to valuing life, progress and the future. Death became something to be fought, pushed back and, ideally, conquered. This change in attitude has also led to a certain fascination with death, which has become a subject of philosophical, literary and artistic reflection, reflecting a certain anxiety in the face of the unknown and the inevitable. This new vision of death reflects a wider shift in human understanding of ourselves and our place in the universe. Life, health and happiness have become central values, while death has become a limit to be pushed back, a challenge to be met. This has had a profound influence on cultural, social and even economic practices, and continues to shape the way contemporary society approaches the end of life and bereavement.

The decline in mortality in the eighteenth century and changes in perceptions and practices around death have had consequences for many aspects of social life, including criminal justice and execution practices. In medieval and early modern times, public executions were commonplace and often accompanied by torture and particularly brutal methods. These executions had a social and political function: they were supposed to be a deterrent, a warning to the population against breaking the law. They were often staged with a high degree of cruelty, reflecting the era's familiarity with violence and death. However, in the eighteenth century, under the influence of the Enlightenment and a new sensitivity towards human life and dignity, there was a transformation in legal and punitive practices. Philosophers of the Enlightenment, such as Cesare Beccaria in his work "Of Crimes and Punishments" (1764), argued against the use of torture and cruel punishments, pleading for a more rational and humane form of justice. Against this backdrop, public executions began to be called into question. They were gradually seen as barbaric and uncivilised, and in contradiction with society's new values. This change in perspective led to reforms in the penal system, with a trend towards more "humane" executions and, ultimately, the abolition of public executions. Execution, rather than being a public spectacle of torture, became a swift and less painful act, with the aim of ending the life of the condemned person rather than inflicting prolonged suffering. The introduction of methods such as the guillotine in France at the end of the 18th century was partly justified by the idea of a quicker and less inhumane execution. The decline in mortality and the accompanying changes in mentality played a part in the transformation of judicial practices, leading to the reduction and eventually the cessation of public executions and associated torture, reflecting a gradual humanisation of society and its institutions.

In the eighteenth century, cemeteries began to be moved out of towns, a sign of a profound transformation in the way society viewed death and the dead. For centuries, the dead had been buried close to churches, in the very heart of communities, but this began to change for a variety of reasons.

Public health concerns gained in importance with increasing urbanisation. Overcrowded cemeteries in towns and cities were seen as potential health threats, especially in times of epidemics. This realisation led the authorities to rethink the organisation of urban spaces to limit health risks. The influence of the Enlightenment also encouraged a new approach to death. It was no longer an everyday spectacle, but a personal and private matter. There was a growing tendency to see death rites and mourning as something to be experienced more intimately, away from the public eye. At the same time, conceptions of the individual were evolving. More dignity was being accorded to the human person, both living and dead, and this translated into a need for funeral spaces that treated the remains with respect and decency. The spirit of rationalism at the time also played a role. There was a greater belief in man's ability to manage and control his environment. Moving cemeteries was a way of reorganising space to improve collective well-being, by bringing the layout of the city into line with the principles of rationality and progress. Moving cemeteries was a concrete expression of a move away from death in everyday life, reflecting a desire to manage it in a more methodical way, and showed a growing respect for the dignity of the dead, while marking a step towards greater control over the environmental factors affecting public life.

The Fight Against Diseases: Progress and Challenges

The externalisation of death in the eighteenth century reflects a period when perspectives on life, health and disease began to change significantly. Enlightenment man, armed with a new faith in science and progress, began to believe in his ability to influence, and even control, his environment and his health. Smallpox was one of the most devastating diseases, causing regular epidemics and high mortality rates. Edward Jenner's discovery of immunisation at the end of the 18th century was a revolution in terms of public health. By using the smallpox vaccine, Jenner proved that it was possible to prevent a disease rather than simply treating it or suffering its consequences. This marked the beginning of a new era in which preventive medicine became an achievable goal, reinforcing the impression that humanity could triumph over the epidemics that had decimated entire populations in the past. This victory over smallpox not only saved countless lives but also reinforced the idea that death was not always inevitable or a fate to be accepted without a struggle. It symbolised a turning point when death, once inextricably woven into everyday life and accepted as an integral part of it, began to be seen as an event that could be postponed, managed and, in some cases, avoided thanks to advances in medicine and science.

Smallpox was one of the most feared diseases before the first effective methods of prevention were developed. The disease has had a profound impact on societies throughout the centuries, causing mass deaths and leaving those who survive often with serious physical after-effects. The metaphor that smallpox took over from the plague illustrates the constant burden of disease within populations before the modern understanding of pathology and the advent of public health.

The observation that humanity could not have withstood two simultaneous plagues such as the plague and smallpox highlights the vulnerability of the population to infectious diseases before the 18th century. The case of famous figures such as Mirabeau, who was disfigured by smallpox, is a reminder of the terror that this disease inspired. Despite the ignorance of what a virus was at the time, the eighteenth century marked a time of transition from superstition and powerlessness in the face of disease to more systematic and empirical attempts to understand and control it. Practices such as variolisation, which involved the inoculation of an attenuated form of the disease to induce immunity, were developed long before science understood the underlying mechanisms of immunology. It was Edward Jenner who, at the end of the 18th century, developed the first vaccination, using pus from cowpox (vaccinia) to immunise against human smallpox, with significantly safer results than traditional variolisation. This discovery was not based on a scientific understanding of the disease at molecular level, which would only come much later, but rather on empirical observation and the application of experimental methods. The victory over smallpox thus symbolised a decisive turning point in humanity's fight against epidemics, paving the way for future advances in vaccination and the control of infectious diseases, which were to transform public health and human longevity in the centuries that followed.

Inoculation, practised before vaccination as we know it, was a primitive form of smallpox prevention. This practice involved the deliberate introduction of the smallpox virus into the body of a healthy person, usually through a small incision in the skin, in the hope that this would result in a mild infection but sufficient to induce immunity without causing full-blown disease. In 1721, the practice of inoculation was introduced to Europe by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who discovered it in Turkey and brought it to England. She inoculated her own children. The idea was that inoculation with an attenuated form of the disease would provide protection against subsequent infection, which could be much more severe or even fatal. This method had significant risks. Inoculated individuals could develop a full form of the disease and become vectors for smallpox transmission, contributing to its spread. In addition, there was mortality associated with the inoculation itself, although this was lower than the mortality from smallpox in its natural state. Despite its dangers, inoculation was the first systematic attempt to control an infectious disease by immunisation, and it laid the foundations for the later vaccination practices developed by Edward Jenner and others. The acceptance and practice of inoculation varied, with much controversy and debate, but its use marked an important step in the understanding and management of smallpox before vaccination with Jenner's safer and more effective vaccine became common in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In 1796, Edward Jenner, an English physician, achieved a major medical breakthrough when he perfected vaccination against smallpox. Observing that milkmaids who had contracted vaccinia, a disease similar to smallpox but much less severe, transmitted by cows, did not contract human smallpox, he postulated that exposure to vaccinia could confer protection against human smallpox. Jenner tested his theory by inoculating James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy, with pus taken from vaccinia lesions. When Phipps subsequently resisted exposure to smallpox, Jenner concluded that inoculation with vaccinia (what we now call vaccinia virus) offered protection against smallpox. He called this process "vaccination", from the Latin word "vacca" meaning "cow". Jenner's vaccine proved to be much safer than previous methods of inoculating against smallpox, and was adopted in many countries despite the wars and political tensions of the time. Despite the ongoing conflict between England and France, Jenner ensured that his vaccine reached other nations, including France, illustrating a remarkable early understanding of public health as a transnational concern. This breakthrough symbolised a turning point in the fight against infectious diseases. It laid the foundations of modern immunology and represented a significant first step towards conquering the epidemic diseases that had afflicted humanity for centuries. The practice of vaccination spread and eventually led to the eradication of smallpox in the twentieth century, marking the first time that a human disease had been eliminated through coordinated public health efforts.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries marked a fundamental change in the attitude of Western societies towards nature. With the decline in mortality from diseases such as smallpox and the increase in scientific knowledge, nature was gradually transformed from an indomitable and often hostile force into a set of resources to be exploited and understood. The Age of Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason and the accumulation of knowledge, led to the creation of encyclopaedias and the wider dissemination of knowledge. Figures such as Carl Linnaeus worked to classify the natural world, imposing a human order on the diversity of living things. This period saw the rise of a scholarly culture in which the exploration, classification and exploitation of nature were seen as ways of improving society. It was also at this time that the first concerns about the sustainability of natural resources began to emerge, in response to the acceleration of industrial exploitation. Debates about deforestation for shipbuilding, coal and mineral extraction, and other intensive exploitation activities reflect an emerging awareness of environmental limits. The anthropocentrism of the time, which placed man at the centre of all things and as master of nature, stimulated industrial and economic development. Over time, however, it also led to a growing awareness of the environmental and social effects of this approach, laying the foundations for the ecological and conservation movements that would later emerge. Thus, the development of a scholarly culture and the valuing of nature not only as an object of study but also as a source of material wealth were key elements in changing humanity's relationship with its environment, a relationship that continues to evolve in the face of contemporary environmental challenges.

The culture of nature

Hans Carl von Carlowitz, a Saxon mining administrator, is often credited with being one of the first to formulate the concept of sustainable management of natural resources. In his 1713 work "Sylvicultura oeconomica", he developed the idea that only as much wood should be cut as the forest can naturally reproduce, to ensure that forestry remains productive in the long term. This thinking was largely a response to massive deforestation and the growing need for wood for the mining industry and as a building material. Hans Carl von Carlowitz is credited with pioneering the concept of sustainability, particularly in the context of forestry. In this book, he set out the need for a balanced approach to forestry, which takes into account the regeneration of trees alongside their harvesting, in order to maintain forests for future generations. This was in response to the wood shortages facing Germany in the 18th century, largely due to over-exploitation for mining and smelting activities. The publication is significant because it laid the foundations for the sustainable management of natural resources, in particular the practice of planting more trees than are cut down, which is a cornerstone of modern sustainable forestry practices. Remarkably, the idea of sustainability was conceptualised over 300 years ago, reflecting an early understanding of the environmental impact of human activity and the need for resource conservation.

Although von Carlowitz's concerns centred on forestry and timber use, his idea reflects a basic principle of modern sustainable development: the use of natural resources should be balanced by practices that ensure their renewal for future generations. At the time, this was an avant-garde concept, as it ran counter to the widespread idea of the unlimited exploitation of nature. However, the notion of sustainable development did not immediately take root in public policy or in the collective consciousness. It was only with the development of environmental sciences and the social changes of the following centuries that the idea of prudent management of the Earth's resources became fully established.

The modern era, particularly from the 18th century onwards, was marked by a fundamental change in humanity's relationship with nature. The scientific revolution and the Enlightenment helped to promote a vision of man as master and possessor of nature, an idea philosophically supported by thinkers such as René Descartes. From this perspective, nature is no longer an environment in which man must find his place, but a reservoir of resources to be used for his own development. Anthropocentrism, which places the human being at the centre of all concerns, becomes the guiding principle for the exploitation of the natural world. According to the religious and cultural beliefs of the time, the earth was seen as a gift from God to the people who were responsible for cultivating and exploiting it. Developments in agronomy and forestry were manifestations of this approach, seeking to optimise the use of soil and forests for maximum production. Voyages of exploration, fuelled by a desire for discovery but also by economic motivations, also reflected this desire to exploit new resources and extend the sphere of human influence. This learned culture of nature was expressed through the creation of classification systems for the natural world, improved cultivation techniques, more efficient mining and regulated forestry. Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, for example, aimed to compile all human knowledge, including knowledge of nature, and make it accessible for rational and enlightened use. It was this approach that laid the foundations for the industrial use of natural resources, foreshadowing the industrial revolutions that were to profoundly transform human societies and their relationship with the environment. However, the large-scale exploitation of nature without consideration for long-term environmental impacts would later lead to the ecological crises we are experiencing today, and to the questioning of anthropocentrism as such.

Annexes

- Vieux Paris, jeunes Lumières, par Nicolas Melan (Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2015) Monde-diplomatique.fr,. (2015). Vieux Paris, jeunes Lumières, par Nicolas Melan (Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2015). Retrieved 17 January 2015, from http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2015/01/MELAN/51961

- Grober, Ulrich. "Hans Carl Von Carlowitz: Der Erfinder Der Nachhaltigkeit | ZEIT ONLINE." ZEIT ONLINE. 25 Nov. 1999. Web. 24 Nov. 2015 url: http://www.zeit.de/1999/48/Der_Erfinder_der_Nachhaltigkeit.