The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, pre-industrial Europe was the scene of a fascinating demographic equilibrium known as demographic homeostasis. This historical period, rich in transformations, saw societies and economies develop against the backdrop of a demographic regime in which population growth was carefully counterbalanced by regulatory forces such as epidemics, armed conflicts and famines. This natural demographic self-regulation has proved to be an engine of stability, orchestrating measured and sustainable economic and social development.

This delicate demographic balance has not only fostered moderate and sustainable population growth in Europe, but has also laid the foundations for coherent economic and social progress. Thanks to this phenomenon of homeostasis, Europe has managed to avoid extreme demographic upheaval, allowing its pre-industrial economies and societies to flourish within a framework of gradual, controlled change.

In this article, we take a closer look at the dynamics of this ancient demographic regime and its crucial influence on the fabric of European economies and communities before the advent of industrialisation, highlighting how this delicate balance facilitated an orderly transition to more complex economic and social structures.

Mortality crises under the Ancien Régime[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

During the Ancien Régime, Europe was faced with frequent and devastating mortality crises, often described through the metaphor of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Each of these horsemen represented one of the major calamities that struck society and contributed to a high mortality rate.

Famine, resulting from poor harvests, extreme weather conditions or economic disruption, was a recurring scourge. It weakened the population, reduced its resilience to disease and led to a dramatic increase in mortality among the poorest. Periods of famine were often followed or accompanied by epidemics which, in a context of widespread weakness, found a fertile breeding ground for their spread. Wars were another major source of mortality. In addition to deaths on the battlefield, conflicts had deleterious effects on agricultural production and infrastructure, leading to a deterioration in living conditions and an increase in deaths indirectly linked to war. Epidemics, for their part, were perhaps the most merciless of the horsemen. Diseases such as the plague and cholera struck indiscriminately, sometimes wiping out entire districts or villages. The absence of effective treatments and a lack of medical knowledge exacerbated their lethal impact. Finally, the horseman representing death embodied the fatal outcome of these three plagues, as well as the daily mortality caused by ageing, accidents and other natural or violent causes. These mortality crises, through their direct and indirect consequences, regulated European demography, keeping the population at a level that the resources of the time could sustain.

The impact of these riders on Ancien Régime society was immense, indelibly shaping the demographic, economic and social structures of the time and leaving a deep imprint on European history.

The hunger[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Jusqu'aux années 1960, la vision prédominante était que la faim constituait le principal facteur de mortalité au Moyen Âge. Cependant, cette perspective a évolué avec la reconnaissance de la nécessité de distinguer la disette de la famine. Si la famine était un événement catastrophique avec des conséquences mortelles massives, la disette était plutôt une occurrence courante dans la vie médiévale, marquée par des périodes de pénurie alimentaire plus modérées mais fréquentes. Dans des villes comme Florence, le cycle agricole était ponctué de périodes de disette presque rythmiques, avec des épisodes de pénurie alimentaire survenant environ tous les quatre ans. Ces épisodes étaient liés aux fluctuations de la production agricole et à la gestion des ressources céréalières. À la fin de chaque saison de récolte, la population se retrouvait devant un dilemme : consommer la production de l'année pour satisfaire les besoins immédiats ou en conserver une part pour ensemencer les champs pour la prochaine saison. Une année de disette pouvait survenir lorsque les récoltes étaient simplement suffisantes pour subvenir aux besoins immédiats de la population, sans pour autant permettre un excédent pour les réserves ou les semences futures. Cette situation précaire était exacerbée par le fait qu'il était impératif de réserver une portion des grains pour les semailles. L'insuffisance de la production signifiait alors que la population devait endurer une période de restrictions alimentaires, avec des rations diminuées jusqu'à la prochaine récolte, en espérant que celle-ci soit plus abondante. Ces périodes de disette ne menaient pas systématiquement à une mortalité de masse comme c'était le cas lors des famines, mais elles avaient néanmoins un impact considérable sur la santé et la longévité de la population. La malnutrition chronique affaiblissait la résistance aux maladies et pouvait augmenter indirectement la mortalité, en particulier chez les individus les plus vulnérables comme les enfants et les personnes âgées. Ainsi, la disette jouait son rôle dans le fragile équilibre démographique du Moyen Âge, façonnant subtilement la structure de la population médiévale.

La distinction entre famine et disette est cruciale pour comprendre les conditions de vie et les facteurs de mortalité au Moyen Âge. Alors que la disette se réfère à des périodes de pénurie alimentaire récurrentes et gérables jusqu'à un certain point, la famine désigne des crises alimentaires aiguës où les individus meurent de faim, souvent en résultat de récoltes dramatiquement insuffisantes causées par des catastrophes climatiques. Un exemple frappant est l'éruption d'un volcan islandais aux alentours de 1696, qui a déclenché un refroidissement climatique temporaire en Europe, parfois décrit comme un "mini âge glaciaire". Cet événement extrême a provoqué une réduction drastique des rendements agricoles, plongeant le continent dans des famines dévastatrices. En Finlande, cette période a été si tragique que près de 30% de la population a péri, soulignant l'extrême vulnérabilité des sociétés préindustrielles face aux aléas climatiques. À Florence, l'histoire démontre que bien que la disette était un visiteur régulier, avec des périodes difficiles tous les quatre ans environ, la famine était un fléau beaucoup plus sporadique, survenant tous les quarante ans en moyenne. Cette différence met en lumière une réalité importante : bien que la faim soit une compagne presque constante pour de nombreuses personnes à l'époque, la mort massive due à la famine était relativement rare. Ainsi, contrairement aux perceptions antérieures largement répandues jusqu'aux années 1960, la famine n'était pas la cause principale de la mortalité à l'époque médiévale. Les historiens ont révisé cette conception en reconnaissant que d'autres facteurs, tels que les épidémies et les conditions sanitaires précaires, jouaient un rôle beaucoup plus significatif dans la mortalité de masse. Cette compréhension nuancée aide à peindre un tableau plus précis de la vie et des défis auxquels étaient confrontées les populations du Moyen Âge.

Les guerres[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

This graph shows the number of war actions in Europe over a 430-year period, from 1320 to 1750. From the curve, we can see that military activity fluctuated considerably over this period, with several peaks that could correspond to periods of major conflict. These peaks could represent major wars such as the Hundred Years' War, the Italian Wars, the Wars of Religion in France, the Thirty Years' War, and the various conflicts involving European powers in the 17th and early 18th centuries. The 'rolling three-year sum' method used to compile the data indicates that the figures have been smoothed over three-year periods to give a clearer picture of trends, rather than reflecting annual variations which may be more chaotic and less representative of long-term trends. It is important to note that this type of historical graph allows researchers to identify patterns and cycles in military activity and correlate them with other historical, economic or demographic events for a better understanding of historical dynamics.

Throughout the Middle Ages and right up to the dawn of the modern period, wars were an almost constant reality in Europe. However, the nature of these conflicts changed significantly over the centuries, reflecting wider political and social developments. In the 14th century, the conflict landscape was dominated by small-scale feudal wars. These clashes, which were often localised, were mainly the result of rivalries between lords over control of land or the settlement of succession disputes. Although these skirmishes may have been violent and destructive at a local level, they were not comparable in scale or consequences to the wars that were to follow. With the consolidation of nation states and the emergence of sovereigns seeking to extend their power beyond their traditional borders, the 14th and 15th centuries saw the emergence of conflicts of unprecedented scale and destructiveness. These new state wars were waged by larger and better organised standing armies, often supported by a burgeoning bureaucratic complex. War thus became an instrument of national policy, with objectives ranging from territorial conquest to the assertion of dynastic supremacy. The impact of these conflicts on the civilian population was often indirect but devastating. As the logistics of armies were still primitive, military stewardship relied heavily on requisitioning and plundering the resources of the regions they passed through. Armies in the field took their sustenance directly from local economies, seizing crops and livestock, destroying infrastructure and spreading famine and disease among civilians. War thus became a calamity for the non-combatant population, depriving them of the means of subsistence they needed to survive. It was not so much the fighting itself that caused the greatest number of civilian deaths, but rather the collapse of local economic structures due to the insatiable needs of the armies. This form of food warfare had a considerable demographic impact, reducing populations not only through direct violence, but also by creating precarious living conditions that encouraged disease and death. War, in this context, was both an engine of destruction and a vector of demographic crisis.

The military history of the pre-modern era clearly shows that armies were not only instruments of conquest and destruction, but also powerful vectors for the spread of disease. Troop movements across continents and borders played a significant role in the spread of epidemics, amplifying their scope and impact. The historical example of the Black Death is a tragic illustration of this dynamic. When the Mongol army laid siege to Caffa, a Genoese trading post in the Crimea, in the 14th century, it unwittingly initiated a chain of events that would lead to one of the greatest health disasters in human history. Bubonic plague, already present among the Mongol troops, was transmitted to the besieged population through attacks and trade. Infected by the disease, the inhabitants of Caffa then fled by sea and returned to Genoa. At the time, Genoa was a major city in the world's trade networks, which facilitated the rapid spread of the plague throughout Italy and, eventually, the whole of Europe. Ships leaving Genoa with infected people on board brought the plague to many Mediterranean ports, from where the disease spread inland, following trade routes and population movements. The impact of the Black Death on Europe was cataclysmic. It is estimated that the pandemic killed between 30% and 60% of the European population, causing massive demographic decline and profound social change. It was a stark reminder of how war and trade could interact with disease to shape the course of history. The Black Death thus became synonymous with a time when disease could reshape the contours of societies with unprecedented speed and scale.

The epidemics[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

This image represents a historical graph showing the number of places affected by the plague in north-west Europe from 1347 to 1800, with a rolling three-year sum to smooth out variations over short periods. This graph clearly illustrates several major epidemics, with peaks indicating a strong spread of the disease at different times. The first and most pronounced peak corresponds to the Black Death pandemic that began in 1347. This wave had devastating consequences for the population of the time, causing the death of a large proportion of Europeans in the space of a few years. After this first major peak, the graph shows several other significant episodes in which the number of places affected increased, reflecting periodic reappearances of the disease. These peaks may correspond to events such as new introductions of the pathogen into the population through trade or troop movements, as well as conditions favouring the proliferation of rats and fleas carrying the disease. Towards the end of the graph, after 1750, there was a decline in the frequency and intensity of epidemics, which may indicate a better understanding of the disease, improvements in public health, urban development, climate change or other factors that helped to reduce the impact of the plague. These data are valuable for understanding the impact of the plague on European history and the evolution of human responses to pandemics.

The relationship between malnutrition, disease and mortality is a crucial component in understanding historical demographic dynamics. In pre-industrial societies, an uncertain and often precarious food supply contributed to increased vulnerability to infectious diseases. Starving populations, weakened by the lack of regular access to adequate and nutritious food, were much less resistant to infection, which considerably increased the risk of mortality during epidemics. The plague, in particular, was a recurrent scourge in Europe throughout the Middle Ages and long after, having a profound effect on society and the economy. The Black Death of the 14th century is perhaps the most notorious example, having decimated a substantial proportion of the European population. The persistence of the plague well into the 18th century bears witness to the complex interaction between human beings, animal vectors such as rats, and pathogenic bacteria such as Yersinia pestis, which causes the plague. Rats, carriers of fleas infected with the bacterium, were omnipresent in densely populated cities and on ships, facilitating the transmission of the disease. However, the spread of the plague could not be attributed to rodents alone; human activities also played an essential role. Armies on the move and merchants travelling trade routes were effective agents of transmission, as they carried the disease with them from one region to another, often at speeds that societies of the time were ill-equipped to manage. This pattern of disease spread highlights the importance of social and economic infrastructures in public health, even in ancient times. The context of plague epidemics reveals the extent to which seemingly unrelated factors, such as trade and troop movements, can have a direct and devastating impact on the health of populations.

The Black Death, which struck Europe in the mid-14th century, is considered to be one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. The demographic impact of the disease was unprecedented, with estimates indicating that up to a third of the continent's population was wiped out between 1348 and 1351. This event profoundly shaped the course of European history, leading to significant socio-economic changes. The plague is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. It is mainly associated with rats, but it is actually fleas that transmit the bacteria to humans. The bubonic version of the plague is characterised by the appearance of buboes, swollen lymph nodes, particularly in the groin, armpits and neck. The disease is extremely painful and often fatal, with a high rate of contagion. The rapid spread of the bubonic plague was partly due to the deplorable hygiene conditions of the time. Overcrowding, a lack of public health knowledge and close cohabitation with rodents created ideal conditions for the spread of the disease. According to some theories, a form of natural selection took place during this pandemic. The weakest individuals were the first to succumb, while those who survived were often those with a natural resistance or who had developed immunity. This could explain the temporary regression of the disease after the first fatal waves. However, this immunity was not permanent; over time, a new generation with no natural immunity became vulnerable, allowing the disease to re-emerge. The 17th century saw new waves of plague in Europe. Although these epidemics were fatal, they did not reach the catastrophic levels of the Black Death. In France, a large proportion of deaths in the 17th century were still due to the plague, which led to "excess mortality". The effect of the plague on the demography of the Ancien Régime was such that natural population growth (the difference between births and deaths) was often absorbed by plague deaths. This led to a relatively stable or stagnant population, with little long-term net growth due to the plague and other diseases that continued to strike the population at regular intervals.

The plague mercilessly attacked the entire population, but certain factors could make individuals more vulnerable. Young adults, who were often more mobile due to their involvement in trade, travel or even as soldiers, were more likely to be exposed to the plague. This age group is also more likely to have extensive social contacts, which increases their risk of exposure to infectious diseases. The high mortality among young adults during plague epidemics had far-reaching demographic implications, notably by reducing the number of future births. Individuals who died before having children represented 'lost births', a phenomenon that reduces the population's growth potential for subsequent generations. This phenomenon was not unique to the plague era. A similar effect was observed after the First World War. The war resulted in the deaths of millions of young men, making up a largely lost generation. Lost births" refer to the children these men might have had had they survived. The demographic impact of these losses reverberated far beyond the battlefields, affecting population structure for decades. The consequence of these two historic disasters can be seen in the age pyramids following these events, where there is a deficit in the corresponding age groups. The decline in the population of childbearing age has led to a natural decline in the birth rate, an ageing population and a change in the social and economic structure of society. These changes have often required major social and economic adjustments to meet the new demographic challenges.

During the Black Death, for example, the most vulnerable population - often referred to as "the weak" in terms of resilience to disease - suffered heavy losses. Those who survived were generally more resilient, either through the good fortune of less severe exposure, or through innate or acquired resistance to disease. The immediate effect of this natural selection of some kind was to reduce overall mortality because the proportion of the population that survived was more resilient. However, this resilience is not necessarily permanent. Over time, this 'stronger' population ages and becomes more vulnerable to other diseases or to the recurrence of the same disease, especially if the disease progresses. As a result, mortality could rise again, reflecting a cycle of resilience and vulnerability. The mortality curve would therefore be marked by successive peaks and troughs. After an epidemic, mortality would fall as the most resistant individuals survive, but over time and under the effect of other stress factors such as famine, war or the emergence of new diseases, it could rise again. This "hatched curve" reflects the ongoing interaction between environmental stressors and population dynamics. The plague wiped out the surplus of births over deaths. The population of France was therefore unable to grow, and there was a demographic standstill, as the surplus of births over deaths was wiped out by the disease. Today, we know that epidemics were the main cause of death in the Middle Ages.

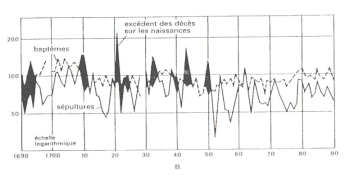

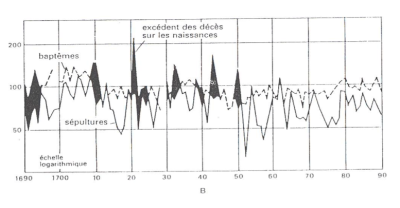

The image shows a black and white graph illustrating baptism and burial rates over what appears to be a period from 1690 to 1790, with a logarithmic scale on the y-axis to measure frequencies. The upper curve, marked by a solid black line and shaded areas, indicates baptisms, while the lower curve, represented by a dotted black line, represents burials. The graph shows periods when baptisms exceed burials, indicated by the areas where the upper curve is above the lower curve. These periods represent natural population growth, where the number of births exceeds the number of deaths. Conversely, there are times when burials outnumber baptisms, demonstrating a mortality rate higher than the birth rate, which is represented by the areas where the burials curve rises above the baptisms curve. The sharp fluctuations in the graph illustrate periods when deaths exceeded births, with significant peaks suggesting mass mortality events, such as epidemics, famines or wars. Line A, which appears to be a trend line or moving average, helps to visualise the general trend in the excess of deaths over births over this century-long period. The period covered by this graph corresponds to tumultuous moments in European history, marked by significant social, political and environmental changes, which had a profound impact on the demography of the time.

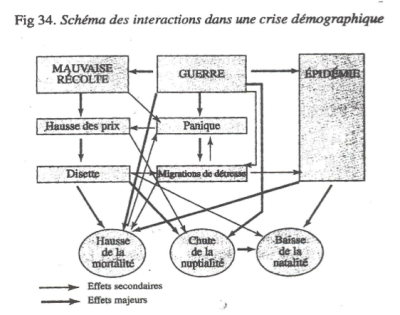

The image shows a conceptual diagram depicting the complex interactions within a demographic crisis. The main factors triggering this crisis are represented by three large rectangles that stand out in the centre of the diagram: crop failure, war and epidemic. These central events are interconnected and their impacts extend across a range of socio-economic and demographic phenomena. A poor harvest is a catalyst, causing prices to rise and food shortages, triggering distress migration. War causes panic and worsens the situation through similar migrations, while epidemics directly increase mortality while also affecting birth rates and marriage rates. These major crises influence various aspects of demographic life. For example, rising prices and famine lead to economic hardship, which has repercussions on marriage and reproduction patterns, illustrated by a fall in the marriage rate and a drop in the birth rate. In addition, epidemics, often exacerbated by famine and population movements due to war, could lead to a significant increase in mortality. The diagram shows the direct effects with solid lines and the secondary effects with dotted lines, showing a hierarchy in the impact of these different events. The diagram as a whole highlights the cascade of effects triggered by crises, demonstrating how a poor harvest can trigger a series of events that spread far beyond its immediate consequences, provoking wars, migrations and facilitating the spread of epidemics, thereby contributing to an increase in mortality and a stagnation or decline in the population.

Homeostasis by controlling population growth[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The concept of homeostasis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Homeostasis is a fundamental principle that applies to many biological and ecological systems, including human populations and their interaction with the environment. It is the ability of a system to maintain a stable internal condition despite external changes. In the context of the Ancien Régime, where technology and the means of acting on the environment were limited, populations had to adapt continuously to maintain this dynamic balance with the available resources. Crises such as famines, epidemics and wars tested the resilience of this balance. However, even in the face of these disruptions, communities strove to re-establish the balance through various survival and adaptation strategies. Farmers, in particular, played an essential role in maintaining demographic homeostasis. They were the most directly affected by crop failure or climate change, but they were also the first to respond to these challenges. Through their empirical knowledge of natural cycles and their ability to adjust their farming practices, they were able to mitigate the impact of these crises. For example, they could alternate crops, store reserves for difficult years, or adapt their diet to cope with food shortages. In addition, rural communities often had systems of solidarity and mutual aid that enabled them to spread risk and help the most vulnerable members in the event of a crisis. This type of social resilience is another aspect of homeostasis, where the cohesion and organisation of society help to maintain demographic and social equilibrium. Homeostasis, in this context, is therefore less a question of active control over the environment than of adaptive responses that enable populations to survive and recover from disturbances, continuing the cycle of stability and change.

Before the advances of modern medicine and the industrial revolution, human populations were heavily influenced by the principles of homeostasis, which regulate the balance between available resources and the number of people who depend on them. Societies had to find ways of adapting to the limitations of their environment in order to survive. Agricultural techniques such as biennial and triennial crop rotation were homeostatic responses to the challenges of food production. These methods allowed soil fertility to be rested and regenerated by alternating crops and fallow periods, thus helping to prevent land exhaustion and maintain a level of production that could meet the needs of the population. Since food resources could not be significantly increased before the technical and agricultural innovations of the industrial revolution, demographic regulation was often achieved through social and cultural mechanisms. For example, the European system of late marriage and permanent celibacy limited population growth by shortening women's fertility period and thus lowering the birth rate. Natural selection also played a role in population dynamics. Epidemics, such as the plague, and famines often eliminated the most vulnerable individuals, leaving behind a population that had either natural resistance or social practices that contributed to survival. This homeostatic dynamism reflects the capacity of biological and social systems to absorb disturbances and return to a state of equilibrium, although this equilibrium may be at a different level from that prior to the disturbance. As in ecosystems, where a fire can destroy a forest but is followed by regeneration, human societies have developed mechanisms to manage and overcome crises.

Long-term micro and macro stability[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The historical perception of people's powerlessness in the face of major crises, particularly death and disease, has long been influenced by the apparent lack of means to understand and control these events. Indeed, before the modern era and the rise of scientific medicine, the exact causes of many illnesses and deaths often remained mysterious. As a result, medieval and pre-modern societies relied heavily on religion, superstition and traditional remedies to try and cope with these crises. However, this vision of complete passivity has been challenged by more recent historical research. It is now recognised that even in the face of seemingly uncontrollable forces, such as plague epidemics or famines, the populations of the time were not entirely resigned. Peasants and other social classes developed strategies to mitigate the impact of crises. For example, they adopted innovative farming practices, introduced quarantine measures, or even migrated to regions less affected by famine or disease. The measures taken could also be community-based, such as organising charity to support those most affected by the crisis. In addition, social and family structures could offer a degree of resilience, by sharing resources and supporting the most vulnerable members. After the Second World War, the situation changed radically with the establishment of social security systems in many countries, the advent of modern healthcare and increased access to information, which led to better understanding and prevention of public health crises. Security of life has improved as a result of these developments, considerably reducing the feeling of powerlessness in the face of illness and death.

Social regulations: the European system of late marriage and permanent celibacy[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Implementation: 16th century - 18th century[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

During the period from the Middle Ages to the end of the pre-industrial period, European populations implemented a demographic regulation strategy known as the European system of late marriage and permanent celibacy. Historical data reveals that this practice led to a relatively high age at marriage and substantial rates of celibacy, particularly among women. For example, historians have documented that during the sixteenth century, the average age at first marriage for women ranged from 19 to 22, while by the eighteenth century this age had risen to between 25 and 27 in many regions. These figures show a significant departure from the norms of medieval times, and contrast sharply with other parts of the world where the age at marriage was much lower and celibacy less common. The percentage of women who never married was also notable. Estimates suggest that between the 16th and 18th centuries, between 10% and 15% of women remained single throughout their lives. This rate of celibacy contributed to a natural limitation in population size, which was particularly crucial in an economy where land was the main source of wealth and subsistence. This system of marriage and birth rate was probably influenced by economic and social factors. With land unable to support a rapidly growing population, late marriage and permanent celibacy served as a population control mechanism. In addition, with inheritance systems tending towards the equal division of land, having fewer children meant avoiding excessive division of land, which could have led to an economic decline in peasant families.

The Saint Petersburg - Trieste line[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The system of late marriage and permanent celibacy was characteristic of certain parts of Europe, particularly in the western and northern regions. The distinction between Western and Eastern Europe in terms of marriage practices was marked by considerable social and economic differences. In the West, where this system was in force, an imaginary line stretching from St Petersburg to Trieste marked the border of this demographic model. Peasants and families in the West often owned their land or had significant rights to it, and inheritance passed through the family line. These conditions favoured the implementation of a birth limitation strategy to preserve the integrity and viability of family farms. Families sought to avoid the fragmentation of land across generations, which could have weakened their economic position. To the east of this line, however, and particularly in areas subject to serfdom, the system was different. Peasants in Eastern Europe were often serfs, tied to their lord's land and with no property to pass on. In this context, there was no immediate economic pressure to limit family size through late marriage or celibacy. Matrimonial practices were more universal and marriages were often arranged for social and economic reasons, without the direct consideration of a strategy to preserve family land. This dichotomy between East and West reflects the diversity of socio-economic structures in Europe prior to the major upheavals of the Industrial Revolution, which would ultimately transform marriage systems and family structures across the continent.

The demographic effects[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

A woman's period of fertility, often estimated at between 15 and 49 years, is crucial to understanding historical demographic dynamics. In a society where the average age at marriage for women is increasing, as was the case in Western Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries, the implications for overall fertility are significant. When the age at marriage rises from 20 to 25, women begin their reproductive lives later, reducing the number of years in which they are likely to conceive. The years immediately after puberty are often the most fertile, and delaying marriage by five years can remove many of the most fertile years from a woman's life. This could result in a drop in the average number of children per woman, as there would be fewer opportunities for pregnancy during her reproductive life. If we consider that a woman can have a child on average every two years after marriage, by removing five years of potentially high fertility, this could amount to a reduction in the birth of two to three children per woman. This reduction would have a significant impact on a population's overall demographic growth. In fact, this practice of marrying late and limiting births was not due to a better understanding of reproductive biology or to contraceptive measures, but rather to a socio-economic response to living conditions. By limiting the number of children they had, families could better allocate their limited resources, avoid excessive subdivision of land and safeguard the economic well-being of subsequent generations. This phenomenon contributed to a form of natural population regulation before the advent of modern family planning.

Late marriage and permanent celibacy[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The system for regulating the birth rate in Western Europe, particularly from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, was largely based on social and religious norms that discouraged childbearing outside marriage. In this context, a significant number of women did not marry, remaining single or becoming widows without remarrying. If we take into account that, in some regions, up to 50% of women could be in this situation at any given time, the impact on overall birth rates would be considerable. Being unmarried and widowed meant, for most women in those days, that they had no legitimate children, partly because of strict social conventions and the teachings of the Catholic Church, which promoted chastity outside marriage. Late marriages were encouraged and sexual relations outside marriage were strongly condemned, reducing the likelihood of out-of-wedlock births. Illegitimate births were rare, with estimates around 2% to 3%. This suggests a relatively high level of conformity to social and religious norms, as well as effective control over sexuality and reproduction outside marriage. This social dynamic has therefore had the effect of significantly reducing overall fertility, with an estimated reduction of up to 30%. This played an essential role in the demographic regulation of the time, ensuring a balance between population and available resources in a context where there were few means of increasing the production of environmental resources. In this way, social structures and cultural norms served as a population control mechanism, maintaining demographic stability in the absence of modern contraceptive methods or medical interventions to regulate the birth rate.

The social and economic structure of pre-industrial Europe had a direct influence on marriage practices. The concept of "marriage equals household" was strongly entrenched in people's minds, meaning that a marriage was not just the union of two people but also the formation of a new, autonomous home. This implied the need to have their own living space, often in the form of a farm or house, where the couple could settle down and live independently. This need for a 'niche' in which to live limited the number of marriages possible at any given time. Marriage opportunities were therefore closely linked to the availability of housing, which in agricultural societies depended on the transmission of property, such as farms, often from generation to generation. Demographic growth was limited by the fixed amount of land and farms, which did not grow at the same rate as the population. As a result, young couples had to wait for a property to become available, either through the death of the previous occupants or when they were ready to give up their place, often to their children or other family members. This contributed to delaying marriage, as young people, particularly men who were often expected to take charge of a farm, had to wait until they had the economic means to support a household before marrying. By delaying marriage, women's fertility periods were also shortened, contributing to a fall in the overall birth rate. Thus, economic and housing limitations played a determining role in marriage and demographic strategies, fostering the emergence of the European model of late marriage and the nuclear household, which had a profound impact on social structures and population dynamics in Europe until the modernisation and urbanisation that accompanied the Industrial Revolution.

The role of family relationships and expectations of children was an important factor in the matrimonial and demographic strategies of pre-industrial European societies. In a context where pension and care systems for the elderly were non-existent, parents depended on their children for support in old age. This often meant that at least one child had to remain single to look after his or her parents. Typically, in a family with several children, it was not uncommon for a tacit or explicit agreement to designate one of the daughters to stay at home and look after her parents. This role was often taken on by a daughter, partly because sons were expected to work the land, generate income and perpetuate the family line. Unmarried daughters also had fewer economic and social opportunities outside the family, making them more available to care for their parents. This practice of permanent celibacy as a form of family 'sacrifice' had several consequences. On the one hand, it ensured a certain amount of support for the older generation, but on the other, it reduced the number of marriages and therefore the birth rate. This functioned as a natural demographic regulation mechanism within the community, contributing to the balance between population and available resources. These dynamics highlight the complexity of the links between family structure, economy and demography in pre-industrial Europe, and how personal choices were often shaped by economic necessity and family duties.

Demographic homeostasis, in the context of pre-industrial societies, reflects a process of natural population regulation in response to external events. When these societies were hit by mortality crises, such as epidemics, famines or conflicts, the population fell considerably. The indirect consequence of these crises was to free up economic and social 'niches', such as farms, jobs or roles in the community, which had previously been occupied by those who had died. This created new opportunities for the surviving generations. Young couples were able to marry earlier because there was less competition for resources and space. As early marriages are generally associated with a longer period of fertility and therefore a potentially higher number of children, the population could bounce back relatively quickly after a crisis. The increased fertility of young married couples compensated for the demographic losses suffered during the crisis, allowing the population to return to a state of equilibrium, according to the principles of homeostasis. This cycle of crisis and recovery demonstrates the resilience of human populations and their ability to adapt to changing conditions, albeit often at the cost of considerable loss of life. It is a demonstration of the concept of homeostasis applied to demography, where after a major external disruption, the social and economic systems inherent in these communities tended to bring the population back to a level that could be sustained by the resources available and the social structures in place.

Nuances in the European system: the three Swiss[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The variety of matrimonial and inheritance practices in Switzerland reflects the way in which traditional societies adapted to economic and environmental constraints. In central Switzerland, the matrimonial system was influenced by strict regulations that restricted access to marriage, thereby favouring wealthy families. This restriction was often accompanied by an unequal pattern of land inheritance, generally favouring the eldest son. This dynamic had significant implications for non-heir children, who were forced to seek means of subsistence outside their place of birth. This constraint on marriage and inheritance had the effect of regulating the local population, leading to emigration which contributed to the demographic balance of the region. By leaving the region to seek their fortune elsewhere, the children who did not inherit avoided the overpopulation that could have resulted from an excessively fragmented division of farmland, thereby preserving the rural economy and social stability of their community of origin.

In the Valais, the matrimonial and inheritance situation contrasted sharply with that in central Switzerland. With no legal restrictions on marriage, individuals were able to marry more freely, regardless of their economic status. When it came to inheritance, Valais tradition favoured an egalitarian distribution of property. Brothers who did not become owners were often compensated, an arrangement that enabled them to start their own lives elsewhere, often by emigrating. These egalitarian inheritance practices regularly led to agreements between brothers to keep farmland intact within the family, voluntarily choosing a single heir to manage the land and continue the family business. In doing so, they ensured that the farms remained viable and that land ownership did not become too fragmented to remain productive. At the same time, it also contributed to a demographic balance, as brothers who left sought opportunities outside the Valais, reducing the pressure on local resources.

In Italian-speaking Switzerland, the social and demographic dynamic was strongly impacted by the professional mobility of men. A large number of men left their homes for extended periods, ranging from a few months to several years, to find work elsewhere. This migration of workers, often seasonal, resulted in a significant imbalance in the local marriage market, de facto reducing the number of possible marriages due to the prolonged absence of men. This absence reduced the opportunities for new families to form, thus limiting the birth rate. In addition, prevailing social conventions and religious values kept women in traditional roles and encouraged marital fidelity. In such a context, women had few opportunities or social tolerance for having children outside marriage. Thus, cultural norms combined with the absence of men played a key role in maintaining a certain demographic balance, limiting natural population growth in Italian-speaking Switzerland.

These various practices illustrate how the regulation of demographic growth could be indirectly orchestrated by social, economic and cultural mechanisms. They made it possible to manage the size of the population according to the capacities of the environment and resources, ensuring the continuity of family structures and the economic stability of communities.

A return to omnipresent death[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The traditional structure of a complete family involves a long-term commitment, with the couple remaining together from the time of their marriage until the end of the woman's fertility period, generally around the age of 50. If this continuity is maintained without interruption, theory suggests that a woman could have an average of seven children during her lifetime. However, this ideal situation is often affected by disruptions such as the premature death of one of the spouses. The premature death of a spouse, whether husband or wife, before the woman reaches the age of 50, can significantly reduce the number of children the couple could have had. Such family breakdowns are common because of health conditions, illness, accidents or other risk factors linked to the times and the social and economic context. When these premature deaths and their effects on family structure are taken into account, the average number of children per family tends to fall, with an average of four to five children per family. This reduction also reflects the challenges of family life and the mortality rates of the time, which had a strong influence on demographics and household size.

Throughout the centuries, childhood has always been a particularly vulnerable period for human survival, and this was even more marked in the pre-modern context where medical knowledge and living conditions were far from optimal. In those days, a considerable number of children - between 20% and 30% - did not survive their first year of life. What's more, only half the children born reached the age of fifteen. This meant that the average couple produced only two to two-and-a-half children who reached adulthood, which was hardly enough for more than simple population replacement. As a result, population growth remained stagnant. This precariousness of existence and familiarity with death profoundly shaped the psyche and social practices of the time. Populations developed homeostasis mechanisms, strategies for maintaining demographic equilibrium despite the uncertainties of life. At the same time, death was so omnipresent that it became an integral part of daily life. The origin of the term "caveau" bears witness to this integration; it refers to the practice of burying family members in the cellar of the house, often because of a lack of space in cemeteries. This relationship with death is striking when we consider the history of Paris in the 18th century. For public health reasons, the city undertook to empty its overcrowded cemeteries within its walls. During this operation, the remains of more than 1.6 million people were exhumed and transferred to the catacombs. This radical measure underlines just how common death was and how little place it left, both literally and figuratively, in the society of the time. Death was not a stranger, but a familiar neighbour that had to be lived with.

The acceptance of and familiarity with death in pre-modern society can also be seen in the existence of guides and manuals teaching how to die appropriately, often under the title of "Ars Moriendi" or the art of dying well. These texts were widespread in Europe as early as the Middle Ages, offering advice on how to die in a state of grace, in accordance with Christian teachings. These manuals offered instructions on how to deal with the spiritual temptations that might arise as death approached, and how to overcome them in order to ensure the soul's salvation. They also dealt with the importance of receiving the sacraments, making peace with God and man, and leaving behind instructions for settling one's affairs and distributing one's possessions. In this context, death was not only an end but also a critical passage that required preparation and reflection. Even in the darkest moments, such as when a person was condemned to death, this culture of death offered a paradoxical form of consolation: unlike many others who died suddenly or without warning, the condemned person had the opportunity to prepare for his last moment, to repent of his sins and to leave in peace with his conscience. This reflected a very different perception of death from the one we have today, where sudden death is often considered the cruellest, whereas in those more ancient times, such an unprepared death was seen as a tragedy for the soul.

Annexes[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

- Carbonnier-Burkard Marianne. Les manuels réformés de préparation à la mort. In: Revue de l'histoire des religions, tome 217 n°3, 2000. La prière dans le christianisme moderne. pp. 363-380. url :/web/revues/home/prescript/article/rhr_0035-1423_2000_num_217_3_103