Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

The transformation of production relations between the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th century is a fascinating period that has shaped the modern world. This era was characterised by a rapid evolution in industrial methods, from traditional crafts and small businesses to highly rationalised mass production. The transition from Taylorism, with its careful analysis of labour movements, to Fordism, which introduced higher wages and increased consumption, brought about profound changes in the structure of society. In this introduction, we explore how the organisation of relations of production not only revolutionised manufacturing and trade, but also reshaped the economic and social landscape, laying the foundations for post-war prosperity and consumerism. We will examine the dynamics between technological advances, remuneration strategies and consumption patterns, which together created a virtuous circle of economic growth that dominated the West in the first half of the twentieth century.

Dynamics of the Organisation of Production Relationships[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant transformation in the organisation of production relationships, with notable changes in the size of companies and the relationship between employers and employees.

At the start of the Industrial Revolution, businesses were generally small. This modest scale encouraged a close relationship between employers and employees. The structures were simple, with few intermediaries, enabling direct communication and rapid decision-making. What's more, many of these businesses were extensions of craft trades, where manual labour and specific skills were highly valued. As the Industrial Revolution progressed, businesses began to expand, leading to major changes in their organisation. This growth was mainly driven by increased demand for manufactured goods, technological advances and expanding markets. This evolution led to increased complexity in business management.

As companies expanded, so did the need for additional levels of management and supervision. New intermediate roles were created, establishing a more pronounced hierarchy within organisational structures. This hierarchisation widened the gap between employees and owners or senior managers, making working relationships more impersonal and less direct. Industrialisation also encouraged the standardisation of production processes and a stricter division of labour. Tasks became more repetitive and less skilled, often reducing workers' autonomy. These changes had a profound influence not only on production methods, but also on the nature of working relationships, transforming the working environment in a lasting way.

These developments had a considerable impact on working conditions, class relations and the social landscape, reflecting the changing dynamics of the times.

The Ascent of Engineers and Work Restructuring[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

From the 1870s and 1880s onwards, industry witnessed a significant change with the rise of engineers in decision-making and technical positions. Their expertise in technology and production processes made them indispensable within industrial companies. They were not only involved in technical aspects, but also in operational decision-making, becoming central figures in the day-to-day management and running of companies. This period saw engineers establish themselves as key players, combining their technical knowledge with management skills. They played a crucial role in the strategy and improvement of production processes, marking their growing importance in the industrial environment. However, this predominant role of engineers began to change with the arrival of business school graduates, particularly from HEC. These newcomers brought a different perspective, often focusing on finance, marketing and global strategy. This transition introduced more commercial management into companies, gradually shifting authority from the hands of engineers to these managers trained in financial and commercial aspects. This change has sometimes been a challenge for engineers, who were used to occupying a central position in technical and operational decisions. The introduction of a more commercially and financially oriented management approach has created tensions, reflecting a change in management priorities and methods within companies. These changes reflect the constant evolution of organisational structures and power dynamics within companies, highlighting how changing economic needs and advances in various fields can influence hierarchy and management practices.

During the inter-war period, a period marked by social and economic upheaval, engineers played a crucial role in transforming the way work was viewed. They introduced concepts of rationalisation and mechanisation into production processes, profoundly influencing the way work was organised and performed. This era saw engineers adopt a rational and structured approach to analysing production. They focused on efficiency and optimisation, seeking to make production processes more effective by breaking them down into smaller tasks and standardising them. The aim was to reduce waste, improve productivity and maximise the use of resources. An important part of this transformation involved bringing man and machine closer together. Engineers saw the machine as superior in terms of productivity, speed, endurance and precision. They therefore sought to adapt human work to bring it more into line with the principles of the machine. This approach was partly inspired by the ideas of Taylorism, a theory of work management developed by Frederick Taylor, which advocated optimising and simplifying tasks to increase efficiency. This vision of engineering had a profound impact on the workforce. It led to greater specialisation and a more advanced division of labour. At the same time, it has sometimes led to a dehumanisation of work, with employees treated more as extensions of the machine rather than as individuals with their own needs and abilities. These developments have also had an impact on working relationships and organisational culture within companies. As processes became more mechanised and the role of the engineer intensified, working relationships evolved, often to the detriment of human interaction and job satisfaction.

During the inter-war period, the division of labour initiated by engineers aimed to significantly transform industrial production, working relationships and interactions with customers. One of the main aims of this division was to control and measure the productivity of each individual worker with precision. By standardising tasks and setting performance standards, managers could now determine exactly how much each worker was expected to produce each day. This represented a major change compared with previous periods, when productivity measurement was less rigorous. What's more, this new way of organising work had a direct impact on customer relations. With more standardised and streamlined production processes, it was possible to calculate delivery times reliably. This enabled companies to offer stronger guarantees to their customers, such as penalties for late delivery or refundable deposits if products were not delivered on time. This approach strengthened customer confidence and introduced a commercial and contractual dimension to production, underlining the importance of customer satisfaction and reliability as key elements of business strategy. Thus, the division of labour during this period marked a turning point in labour management and customer relations in the industry, introducing more methodical production methods and emphasising reliability and trust as essential components of business relationships.

Foundations and Principles of Taylorism[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Taylorism, developed by Frederick W. Taylor in the early 20th century, is an approach to production management that revolutionised industrial practices. This system focuses on increasing efficiency and productivity through a number of key methods. The first stage of Taylorism involves breaking down tasks into elementary operations. This decomposition aims to simplify each task so that it can be carried out more efficiently and quickly. By reducing the complexity of tasks, workers can specialise in specific operations, which increases their speed and efficiency. Taylorism then standardises these operations. This means establishing uniform working methods and clearly defined procedures for each task. Standardisation helps to ensure consistency and predictability in production, reducing errors and variations in product quality. Another crucial element of Taylorism is the use of measurement tools to assess and improve worker performance. These tools may include stopwatches to measure the time taken to complete each task, allowing managers to set time and productivity standards. Workers are then encouraged or incentivised to meet or exceed these standards. The adoption of Taylorism offered a number of advantages for companies. By increasing the speed and quantity of production while maintaining or reducing labour costs, companies can significantly improve their profitability. This gain in efficiency can enable mass production, reducing unit costs and potentially increasing the company's market share.

Taylorism, developed around 1880 by the American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, is a revolutionary approach to industrial production management. This method emerged from the study and accumulation of knowledge by a number of engineers, with Taylor providing rigorous systematisation and formalisation. The essence of Taylorism lies in the scientific study of manual labour. Taylor and his contemporaries sought to break down workers' movements and gestures in order to eliminate unnecessary actions and optimise those that added value. This approach aimed to maximise the efficiency of each movement, thereby reducing the time and effort required to complete each task. A central part of this method was the scientific organisation of work. This involved a meticulous analysis of production methods, including the movements, rhythms and paces of workers. The aim was to determine the most efficient way of producing. Taylor also advocated a change in the structure of remuneration, from task wages to hourly wages, to encourage greater productivity. To analyse and improve work techniques, Taylor and his colleagues used methods such as timing and filming workers. These techniques enabled them to understand workers' actions in detail and identify ways of improving efficiency. Taylorism had advantages for both employers and workers. For employers, the application of Taylorism meant improved production through increased efficiency. For workers, work became theoretically easier and less dangerous thanks to the elimination of unnecessary gestures and the simplification of tasks.

The spread of Taylorism in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was largely influenced by the large waves of immigration during this period, particularly from the Slavic and Italian regions. These immigrants, often illiterate and with no formal qualifications, formed an abundant and easily malleable workforce, which corresponded perfectly to the demands of Taylorism. Because of their lack of prior qualifications and skills, immigrant workers were particularly well suited to the standardised and simplified working methods advocated by Taylorism. Companies could therefore quickly train these workers for specific tasks, increasing production efficiency while keeping labour costs relatively low. This gave industrial employers a considerable advantage, enabling them to maximise productivity in their factories. From a social and cultural perspective, this trend had mixed consequences. For immigrants, it offered employment opportunities and a means of integrating into American society. However, it also led to difficult working conditions, with monotonous and repetitive tasks, and little recognition of individual skills. The workplace was often highly controlled, with an emphasis on production rather than the well-being of workers. The adoption of Taylorism in the United States was fuelled by the unique characteristics of the labour market at the time, which was characterised by high immigration and an unskilled workforce. Although this approach promoted industrial efficiency, it also raised questions about working conditions and the treatment of employees within the system.

In Europe, the reception of Taylorism was marked by different perceptions and circumstances from those in the United States. Initially, there was some resistance to the adoption of Taylorist principles, mainly because of concerns about their effects on traditional crafts and on the labour force. At first, many Europeans saw Taylorism as a threat to craft trades, which valued the skills, creativity and autonomy of workers. The idea that the machine could make the worker 'stupid' by depriving him of the need to think and make decisions was a major concern. This methodology was seen not only as an oversimplification of the work process, but also as a potential dumbing-down of workers, reducing their role to mere performers of repetitive, uncreative tasks. However, the situation changed with the outbreak of the First World War. With many men traditionally employed in industry being sent to the front, factories were faced with a shortage of skilled labour. To fill the gap, women and workers from the colonies, who were generally unskilled, were widely employed in industry. These new groups of workers were more likely to accept Taylorist working methods, which did not require extensive prior skills or training. During the war, the need for fast and efficient production was vital to support the war effort. Taylorist practices, focused on efficiency and productivity, were therefore particularly well suited to this context. The workforce, being more docile and less accustomed to traditional working methods, adapted more easily to standardised and repetitive work systems. As a result, Taylorism began to gain ground in Europe, facilitated by the unique demands of the wartime context. While Taylorism met with initial resistance in Europe due to concerns about craftsmanship and the dehumanisation of work, the First World War created conditions that favoured its adoption. The need for efficient production and the availability of non-traditional labour contributed to the spread of these production management methods across the European continent.

The Economic and Operational Benefits of Taylorism[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Taylorism, as a production management system, offered a number of advantages, particularly for employers in the context of industrialisation. Firstly, it made it possible to remedy labour shortages. By simplifying and standardising tasks, Taylorism made it possible to use less skilled workers effectively. This approach is particularly advantageous in situations where skilled labour is limited or expensive.

Secondly, Taylorism gave employers a means of tightly controlling the working class. By precisely defining tasks and measuring productivity, managers can exercise rigorous control over the pace and quality of work, thereby reducing variations in performance and unproductive behaviour.

Increased productivity is another major advantage of Taylorism. By optimising each task and eliminating superfluous movements, workers can produce more in less time. This improved efficiency translates into higher output, which is essential for business growth and competitiveness.

Finally, Taylorism can help reduce labour costs. The simplification of tasks and standardisation of work processes meant that less skilled workers could be hired, who were generally less expensive. In addition, increased productivity means that more products can be produced with less labour, thereby lowering labour costs per unit produced.

These advantages made Taylorism popular in the industrial world, particularly when it was first developed and implemented. However, the method has also been criticised for its potential effects on worker well-being, such as monotonous work, reduced autonomy and increased pressure to achieve high productivity targets.

Production Optimisation: The Era of the Assembly Line[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Line work is a production system based on the division of labour and the organisation of workers into different stations or posts. In this system, each worker is responsible for a specific, repetitive task, contributing to one stage in the manufacture of a final product. This method organises workers into production lines, where products move from one station to another, with each worker adding his or her contribution in a predefined order. This system is designed to maximise efficiency and productivity. By standardising tasks and minimising the transition time between different stages of production, assembly line working speeds up the manufacturing process and enables efficient mass production. This leads to a significant increase in the quantity of finished products available and a reduction in production costs. However, despite its advantages in terms of efficiency, assembly line working can have negative effects on workers. The tasks assigned are often monotonous and repetitive, which can lead to a feeling of alienation. Workers can feel disconnected from the final product and their own contributions, due to the fragmented nature of their work. In addition, the fast pace and repetitive nature of the tasks can lead to physical and mental stress, as well as reduced job satisfaction. Although assembly line work has revolutionised industrial production by increasing efficiency and productivity, it also raises important questions about the well-being of workers and the impact of standardisation on the human experience of work.

Henri Ford is famous for having been one of the main instigators of assembly line work in the car industry. In his factories in Detroit, Michigan, from the 1910s onwards, he implemented this system, revolutionising mass production. Ford introduced the concept of breaking down tasks into small, simple operations. Each worker on the assembly line was assigned a specific, repetitive task, which standardised the production process. By standardising these tasks and making them as efficient as possible, Ford was able to significantly reduce the time needed to assemble a vehicle. This methodology has had several major consequences. Firstly, it has led to a spectacular increase in production speed. The Ford Model T, one of the first mass-produced vehicles using this method, could be assembled much more quickly than cars produced using traditional methods. As a result, production quantities also increased dramatically, meeting the growing demand of the automotive market. In addition, Ford's approach helped to reduce labour costs. By simplifying tasks, it was possible to use less skilled labour, which could be trained quickly and efficiently for specific tasks. It also allowed Ford to offer higher wages to its workers, such as the famous five-dollar-a-day wage, while reducing overall production costs. Ford's introduction of the assembly line not only transformed his company and the automotive industry, but also had a significant impact on industrial production practices around the world. This innovation marked a turning point in industrial history, laying the foundations for modern mass production.

Henri Ford not only adopted assembly-line working in his factories, but also introduced technological innovations that greatly improved its efficiency. Among these innovations, moving conveyors played a crucial role. These conveyors transported the products being manufactured from one workstation to another, facilitating the continuity of the production process and reducing the time wasted moving parts around. In addition, Ford implemented the use of specially designed assembly tools for each task on the production line. These tools were adapted to a specific use, minimising errors and interruptions in the assembly process. This standardisation of tools, combined with the continuous movement of parts on conveyors, enabled fast and efficient production. Thanks to these innovations, Ford was able to produce cars at an unprecedented rate. The Ford Model T, in particular, became a symbol of the efficient mass production made possible by these technological and organisational advances. Ford's ability to rapidly produce large quantities of cars at relatively low cost transformed the company into one of the largest car manufacturers in the world. Ford's impact on the concept of the assembly line was a key element of the Industrial Revolution. He demonstrated how the effective application of this system could not only increase productivity, but also improve the profitability of companies. Ford's innovations in mass production had a lasting impact, influencing industrial production methods far beyond the car industry.

Uniformity and Interchangeability: Standardisation of Components[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The assembly line, as introduced and popularised by industrialists such as Henry Ford, relies heavily on the standardisation of parts. This standardisation is crucial to the smooth running of the assembly line production system, as it ensures consistent uniformity and compatibility between the parts and components used in the manufacturing process. In an assembly line production system, it is essential that each part fits perfectly into the final product without the need for modifications or adjustments. This is because the production line is designed to be a continuous, fluid process. Stopping the line to make repairs or adjustments to a part would disrupt the entire production process, leading to delays and loss of efficiency. Before the advent of assembly-line production, parts were often manufactured and adjusted manually by craftsmen such as fitters. The role of these professionals was to adapt and perfect each part to fit the object being manufactured, a process that required a high degree of skill and attention to detail. However, this method was much slower and less efficient than assembly-line production. Standardisation and mechanisation changed this approach. By producing perfectly standardised parts, manufacturers were able to speed up the production process and reduce costs. Each mechanically manufactured part had exactly the same dimensions and specifications as the others, ensuring smooth integration into the production process without the need for manual adjustments. This move towards standardisation was a key factor in the rise of mass production and has greatly influenced modern industrial practices. It has made production faster, more efficient and cheaper, although it has also reduced the need for traditional craft skills in industrial production.

Assembly line working, as adopted in the car industry by companies such as Ford, has encouraged uniform production, marked by a repetitive manufacturing process and the production of a limited range of models. This method has had significant implications for the nature of the products manufactured, particularly in terms of design and functionality. In the case of Ford, for example, the mass production of the Model T is a perfect illustration of this concept. The Model T was available in a limited number of variants, which was a direct consequence of the assembly-line production approach. This standardisation enabled Ford to produce vehicles more efficiently and economically, but it also limited the diversity of products available to consumers. The emphasis on uniform production and standardisation led to a focus on product design. In a context where functional differences between products were minimised by their uniform manufacture, design became a key means of differentiating products. For companies like Ford, this meant that design had to be not only aesthetically pleasing, but also functional, eliminating unnecessary parts and optimising the product for sale. This focus on functionality and simplicity led to the elimination of superfluous components, which not only reduced costs but also improved product reliability. By concentrating on the essentials, manufacturers could ensure better quality and greater efficiency, while creating products that were attractive to consumers. Assembly line working led to more uniform production and a reduced product range, with a particular emphasis on functional design. This approach transformed the way products were manufactured and marketed, emphasising efficiency, functionality and aesthetics, while limiting the variety of products available.

Line production, characterised by its uniform nature and reduced product range, led to increased efficiency in the manufacturing process. One of the key advantages of this system is the immediate adjustment of production operations, with no significant delays or waiting times. Each stage of production is carefully synchronised with the others, allowing smooth and continuous manufacturing. In terms of design and function, in-line production has made it possible to incorporate a degree of modularity into the products. This modularity, combined with standardised design, facilitates mass production while offering a degree of flexibility in the final assembly of the product. Design, in this context, is not just limited to the aesthetics of products; it also encompasses aspects such as the performance and durability of parts. An important aspect of design in assembly line production is the consideration of product life. Manufacturers, in some cases, may design products with a limited lifespan, a practice known as programmed obsolescence. This approach aims to encourage regular renewal of consumption by creating products that require replacement after a certain period. While this can stimulate sales and demand for new products, it also raises questions about sustainability and environmental impact. Chain production has transformed not only the way products are made, but also the way they are designed. The emphasis on efficiency, modularity and functional design has enabled rapid and cost-effective mass production, while introducing strategies such as programmed obsolescence to stimulate consumption. These practices have had profound implications for both the economy and society in general.

Functionalism and design in the context of assembly-line production reflect a resolutely industrial approach, in which the main aim is to optimise production to meet commercial objectives. This approach is characterised by a focus on the manufacture of products designed specifically for sale, encouraging mass production and stimulating consumption. From this perspective, design and functionalism are not limited to the simple aesthetics or ergonomics of products. They encompass a broader vision that includes production efficiency, cost reduction, and the creation of products that meet specific market needs. The idea is to design products that are not only attractive and functional, but also easy and economical to produce in large quantities. The emphasis on mass production means designing products that can be manufactured quickly, in series, and at a low unit cost. This enables companies to sell these products at an affordable price to a wide audience, thereby encouraging mass consumption. In the car industry, for example, this principle has made cars accessible to a much wider section of the population. In addition, this industrial approach often includes strategies to encourage regular renewal of products by consumers, such as programmed obsolescence. By limiting the lifespan of products, manufacturers can stimulate continuous demand for new models or versions, fuelling a continuous cycle of production and consumption. This approach has profoundly influenced industrial and economic development, fostering the rise of consumer-based market economies. However, it also raises questions about the sustainability, environmental impact and ethical implications of mass production and consumption.

Fordism: the synthesis of mass production and mass consumption[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Henry Ford developed an economic model that also had profound political and social ramifications. This model, often referred to as Fordism, was not just about optimising production, but also about how profits and productivity gains should be used. One of Ford's most significant innovations in this area was the indexing of wages to productivity gains. By introducing the "Five Dollar Day" in 1914, Ford doubled the standard daily wage for his employees, a radical decision for the time. This significant increase in wages had several objectives and effects. Firstly, by increasing the wages of its employees, Ford enabled them to purchase the products they were making, in this case cars. This strategy turned workers into consumers, thereby stimulating demand for Ford's products. It was a practical application of the idea that to sustain a consumer economy, workers had to have sufficient purchasing power to buy the goods they produced. In addition, by paying its employees higher wages, Ford sought to improve worker motivation and loyalty. This also helped to reduce the high staff turnover rate and the costs associated with training new employees, a common problem in factories at the time. The model also had wider social and economic implications. It contributed to the emergence of a larger and more solvent middle class, able to participate in the consumer economy. In addition, Ford's approach to worker pay was influential, prompting other companies to reconsider their own pay structures.

Henry Ford's vision and model of mass production played a key role in shaping the Western economy of the twentieth century. The fundamental idea behind this model was that mass production could be supported by mass consumption, a notion that transformed both markets and societies. In this model, increased production and reduced unit product costs made goods more accessible to a wider range of consumers. At the same time, higher wages, such as Ford's 'Five Dollar Day', gave workers greater purchasing power, enabling them to buy the products they helped to make. This cycle of production and consumption contributed to the rise of the middle class and encouraged the growth of the consumer economy. However, this economic model was not without its critics. Neo-Marxist writers, for example, saw in this system a "gentrification" of the European working class. In their view, the consumer society created by Fordism helped to integrate the working class into a capitalist system, making them dependent on the consumption of mass-produced goods and attenuating their revolutionary potential. They argued that this integration served to stabilise and perpetuate the capitalist system, by distancing the working class from the class struggle and reducing their propensity to question the established order. The economic model promoted by Ford and his contemporaries had strong ideological and political dimensions. It reflected and reinforced certain values such as materialism, continuous economic growth and individualism, which became pillars of many Western societies in the twentieth century.

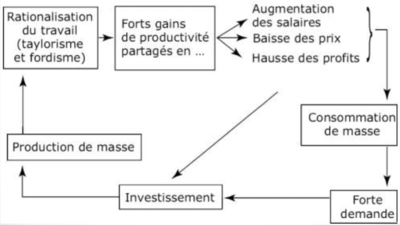

This diagram illustrates the central dynamics of Fordism, an economic model that integrates mass production and mass consumption. At the heart of this model is the rationalisation of work, the principles embodied in Taylorism and Fordism, where efficiency is optimised by standardising tasks and specialising workers. This increased efficiency translates into significant gains in productivity, which are divided between higher wages for employees, lower sales prices for consumers and higher profits for companies. Wage increases, in particular, play a key role in this model. It allows workers to acquire more purchasing power, which turns them into consumers of the products they produce. This increased consumption, supported by lower prices due to economies of scale and the efficiency of mass production, leads to strong demand for products. To meet this demand, companies need to invest more in production, fuelling a virtuous economic cycle of growth and prosperity. In the post-war context, this system supported economic development and the expansion of the middle class in the West. However, critics of Fordism, particularly neo-Marxist thinkers, highlight its ideological and political implications, arguing that the model functioned as an instrument against communism by promoting the gentrification of the working class and integrating them into the capitalist system. The scheme therefore captures the essence of an era when mass production and consumption became the driving forces of the Western economy, a model that was gradually challenged with the rise of the so-called post-Fordist society, characterised by more flexible modes of production and economies.

The idea of high wages combined with the power of trade unions in the post-war context, particularly during the Trente Glorieuses (period of exceptional economic growth after the Second World War until the early 1970s), played a crucial role in structuring Western societies. This period saw the emergence of a system in which workers benefited from higher pay and better working conditions, largely thanks to the influence of trade unions. From the point of view of political logic, this development can be interpreted as a response to communism. At a time when communist ideology was gaining ground, partly because of its promises of fairness and protection for workers, Western countries, anxious to counter the appeal of communism, sought to demonstrate that capitalism could also offer significant benefits to the working classes. From a socio-political point of view, the improvement of wages and working conditions in Western countries served as an instrument in the fight against Communist influence, particularly in Western Europe. By offering workers a greater share of the economic benefits, improving their living conditions and guaranteeing more extensive social rights, governments and companies hoped to dissipate the appeal of communism. This strategy helped to stabilise Western societies during this period, reducing social discontent and increasing loyalty to the capitalist system. Workers, benefiting from a better quality of life and greater protection, were less inclined to support revolutionary movements. Wage improvements and advances in workers' rights during the Trente Glorieuses can be seen as part of a wider strategy to counter the appeal of communism by offering a viable and attractive alternative within the capitalist system. This played an important role in the political and social dynamics of the period.

Fordism, as it emerged and developed in the decades following the Second World War, was a key driver in the transformation of major industrial sectors and significantly shaped the socio-political model of the time. It became synonymous with a certain type of economic and social organisation, characterised by mass production, high wages, product standardisation and high consumption. After the Second World War, Fordism was a fundamental element in understanding the post-war economy and society. It helped to shape a period of economic prosperity and social stability in many Western countries, partly through the promise of continued economic growth and improved living conditions for the working class. However, from the last decades of the twentieth century onwards, the Fordist model began to be challenged and gradually gave way to what is known as the post-Fordist society. This transition marks a shift towards more flexible economies, characterised by more diversified production, greater flexibility in working practices, technological innovation, and a change in labour relations. In post-Fordist societies, the emphasis is on adaptability, product customisation, and the ability to respond quickly to market changes. Information and communication technologies play a key role in this new era, facilitating more agile production and more dynamic management of human resources. In addition, there is a shift towards a service economy and a greater emphasis on knowledge and innovation. The transition from Fordism to Post-Fordism reflects changes in global economic conditions, technological advances and shifts in consumer expectations. Whereas Fordism emphasised efficiency through standardisation, Post-Fordism values flexibility, innovation and the ability to adapt quickly to new market conditions. This development also has profound implications for the structure of work, industrial relations and socio-economic dynamics in the contemporary world.

Conclusion on the Evolution of Production Relationships[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

At the end of our exploration of the organisation of production relations from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, we find that this period was the scene of profound changes that redefined not only industry, but society as a whole. Taylorism and Fordism, as the catalysts of the industrial age, not only optimised working conditions through a series of scientific methods, but also laid the foundations for a new economic and cultural reality.

The productivity gains resulting from these working methods led to wage increases which, like the famous "Five Dollar Day" at Ford, gave a previously marginalised working class unprecedented purchasing power. This development transformed workers into consumers and gave rise to a new market for consumer goods. Ford's Model T cars, mass-produced and sold at affordable prices, became emblematic of this era and symbolised the democratisation of consumerism. This period also saw the rise of the trade unions, which played a crucial role in negotiating working conditions and wages. Their influence contributed to the establishment of social protections and an implicit social contract promising security and prosperity in exchange for productivity. However, this golden period was not without its critics and contradictions. Neo-Marxist thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse argued that the integration of the working class into the capitalist system, facilitated by mass consumption, represented a subtle form of subjugation, a move away from traditional class struggles. They saw the resulting consumer culture as a strategy for containing the revolutionary potential of the masses.

In the contemporary post-Fordist era, the shift to flexible economies underlines the contrast with Fordist practices. Globalisation, information technology and the transition to a service economy have introduced new paradigms of work and consumption. The Fordist model of stability and uniform consumption has given way to an era of personalisation, rapid change and economic uncertainty. The period from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century was an era of unprecedented progress, shaping our modern understanding of work, production and consumption. The impact of Fordism and Taylorism is still felt today, although the global economy has evolved towards more nuanced and adaptive models. This era remains an essential chapter in understanding the evolution of industrial societies and their transition to the complexity of the current era.