The social costs of the Industrial Revolution

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

During the 19th century, Europe witnessed a profound metamorphosis - the Industrial Revolution - marked by unprecedented economic growth and a drive towards modernity. However, this period of growth and innovation was also synonymous with tumultuous social transformations and considerable humanitarian challenges. Delve into the English towns of the 1820s, walk through the steaming workshops of Le Creusot in the 1840s, or peer into the darkened alleys of East Belgium in the 1850s, and you'll see a striking contrast: technological progress and prosperity rubbed shoulders with exacerbated precariousness and chaotic urbanisation.

Rampant urbanisation, insalubrious housing, endemic diseases and deplorable working conditions defined the daily lives of many workers, with life expectancy dropping dramatically to 30 years in industrial centres. Hardy and bold people left the countryside to throw themselves into the arms of voracious industry, contributing to a relative improvement in mortality in rural areas, but at the cost of an overwhelming urban existence. The deadly influence of the environment was even more pernicious than the rigours of factory work.

In the midst of this era of glaring inequality, epidemics such as cholera highlighted the failings of modern society and the vulnerability of underprivileged populations. The social and political reaction to this health crisis, from the repression of workers' movements to the bourgeois fear of insurrection, revealed a growing divide between the classes. This division was no longer dictated by blood, but by social status, reinforcing a hierarchy that further marginalised the workers.

Against this backdrop, the writings of social thinkers like Eugène Buret become poignant testaments to the industrial age, expressing both criticism of an alienating modernity and hope for a reform that would integrate all citizens into the fabric of a fairer political and social community. These historical reflections offer us a perspective on the complexity of social change and the enduring challenges of equity and human solidarity.

The new spaces[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Industrial basins and towns[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

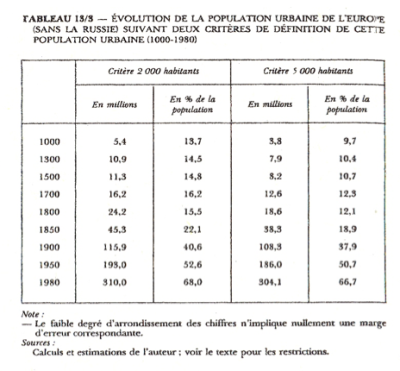

This table gives an historical overview of the growth of the urban population in Europe, excluding Russia, through the ages, highlighting two population thresholds for defining a city: those with more than 2,000 inhabitants and those with more than 5,000 inhabitants. At the start of the second millennium, around the year 1000, Europe already had a significant proportion of its population living in urban areas. Towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants were home to 5.4 million people, making up 13.7% of the total population. If we raise the threshold to 5,000 inhabitants, we find 5.8 million people, representing 9.7% of the population. As we move towards 1500, we see a slight proportional increase in the urban population. In towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, it rose to 10.9 million, or 14.5% of the population. In towns with more than 5,000 residents, the number rose to 7.9 million, equivalent to 10.4% of the total population. The impact of the Industrial Revolution became clearly visible in 1800, with a significant jump in the number of city dwellers. There were 26.2 million people living in towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, who now accounted for 16.2% of the total population. For towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants, the number rises to 18.6 million, representing 12.5% of the population. Urbanisation accelerated further in the mid-nineteenth century, and by 1850 there were 45.3 million people living in towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, corresponding to 22.1% of the total population. Towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants were home to 38.3 million people, or 18.9% of the population. The twentieth century marked a turning point with massive urbanisation. By 1950, the population of towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants had risen to 193.0 million, representing a majority of 53.6% of the total population. Cities with more than 5,000 inhabitants were not to be outdone, with a population of 186.0 million, or 50.7% of all Europeans. Finally, in 1980, the urban phenomenon reached new heights, with 310.0 million Europeans living in towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, representing 68.0% of the population. The figure for towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants was 301.1 million, equivalent to 66.7% of the population. The table thus reveals a spectacular transition from a predominantly rural to a predominantly urban Europe, a process that accelerated with industrialisation and continued throughout the 20th century.

According to the economic historian Paul Bairoch, the society of the Ancien Régime was characterised by a natural limit of the urban population to around 15% of the total population. This idea stems from the observation that, until 1800, the vast majority of the population - between 70% and 75%, and even 80% during the winter months when agricultural activity slowed down - had to work in agriculture to produce enough food. Food production thus limited the size of urban populations, as agricultural surpluses had to feed city dwellers, who were often regarded as "parasites" because they did not contribute directly to agricultural production. The population not involved in agriculture, around 25-30%, was spread across other sectors of activity. But not all were urban dwellers; some lived and worked in rural areas, such as parish priests and other professionals. This meant that the proportion of the population that could live in the city without overburdening the productive capacity of agriculture was a maximum of 15%. This figure was not due to any formal legislation but represented an economic and social constraint dictated by the level of agricultural and technological development at the time. With the advent of the industrial revolution and advances in agriculture, the capacity of societies to feed larger urban populations increased, allowing this hypothetical limit to be exceeded and paving the way for increasing urbanisation.

The demographic and social landscape of Europe has undergone considerable change since the mid-19th century. Around 1850, the beginnings of industrialisation began to alter the balance between rural and urban populations. Technological advances in agriculture began to reduce the amount of labour needed to produce food, and expanding factories in the cities began to attract workers from the countryside. However, even with these changes, peasants and rural life remained predominant at the end of the 19th century. The majority of Europe's population still lived in farming communities, and it was only gradually that towns grew and societies became more urbanised. It was not until the mid-twentieth century, particularly in the 1950s, that we saw a major change, with the rate of urbanisation in Europe crossing the 50% threshold. This marked a turning point, indicating that for the first time in history, a majority of the population was living in cities rather than in rural areas. Today, with an urbanisation rate in excess of 70%, cities have become the dominant living environment in Europe. England, with cities such as Manchester and Birmingham, was the starting point for this change, followed by other industrial regions such as the Ruhr in Germany and Northern France, both of which were rich in resources and industries that attracted large workforces. These regions were the nerve centres of industrial activity and served as models for urban expansion across the continent.

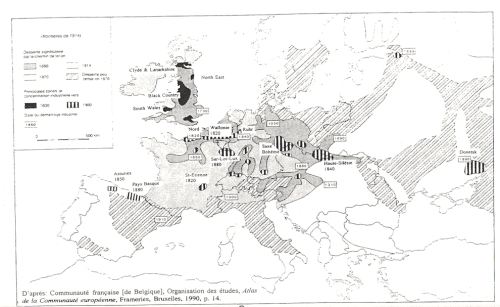

This map is a graphic representation of Europe in the pre-industrial era, highlighting the areas that were major industrial centres before the First World War. It highlights the intensity and specialisation of industrial activities through different symbols and patterns that identify the predominant types of industry in each region. Dark areas marked by symbols of blast furnaces and coal mines indicate industrial basins focused on metallurgy and mining. Places like the Ruhr, Northern France, Silesia, the Black Country region of Belgium and South Wales stand out as key industrial centres, showing the importance of coal and steel in the European economy at the time. Areas with stripes indicate regions where the textile industry and mechanical engineering were strongly represented. This geographical distribution shows that industrialisation was not uniform but rather concentrated in certain places, depending on available resources and capital investment. Distinct features denote regions specialising in iron and steel, notably Lorraine and parts of Italy and Spain, suggesting that the steel industry was also widespread, though less dominant than the coal industry. Maritime symbols, such as ships, are positioned in areas such as the North East of England, suggesting the importance of shipbuilding, which was consistent with the expansion of European colonial empires and international trade. This map provides a striking illustration of how the Industrial Revolution changed the economic and social landscape of Europe. The industrial regions identified were probably hotspots for internal migration, attracting workers from the countryside to the growing cities. This had a profound effect on demographic structure, leading to rapid urbanisation, the development of the working classes and the emergence of new social challenges such as pollution and substandard housing. The map highlights the unevenness of industrial development across the continent, reflecting the regional disparities that have emerged in terms of economic opportunities, living conditions and population growth. These industrial regions exerted a decisive influence on the economic and social trajectories of their respective countries, an influence that lasted well beyond the classical industrial era.

The historical map of pre-industrial Europe depicts two main types of industrial region that were crucial to the continent's economic and social transformation: the 'black countries' and the textile towns. The "black countries" are represented by areas darkened with icons of blast furnaces and mines. These regions were the heart of heavy industry, centred mainly on coal mining and steel production. Coal was the basis of the industrial economy, powering the machines and factories that underpinned the Industrial Revolution. Regions such as the Ruhr in Germany, Northern France, Silesia and the Black Country in Belgium were notable industrial centres, characterised by a dense concentration of coal- and steel-related activities. In contrast, the textile towns, indicated by striped areas, specialised in the production of textiles, a sector that was also vital during the Industrial Revolution. These towns took advantage of mechanisation to mass-produce fabrics, which elevated them to the status of major industrial centres. The textile revolution began in England and quickly spread to other parts of Europe, giving rise to numerous industrial towns centred on spinning and weaving. The distinction between these two types of industrial region is crucial. Whereas the black countries were often characterised by pollution, difficult working conditions and a significant environmental impact, textile towns, while also having their own social and health challenges, were generally less polluting and could be more dispersed in character, as textile mills required less concentration of heavy resources than blast furnaces and mines. The map therefore highlights not only the geographical distribution of industrialisation, but also the diversity of industries that made up the economic fabric of Europe at that time. Each of these regions had distinct social effects, influencing the lives of workers, the structure of social classes, urbanisation and the evolution of urban and rural societies in the context of the Industrial Revolution.

Black Country" is an evocative term used to describe the regions that became the scene of coal mining and metal production during the Industrial Revolution. The term refers to the omnipresent smoke and soot in these areas, the result of the intense activity of blast furnaces and foundries that transformed peaceful villages into industrial towns in a very short space of time. The atmosphere was so polluted that the sky and buildings were literally blackened, hence the name "black countries". This phenomenon of rapid industrialisation turned the static world of the time on its head, marking the start of an era in which economic growth became the norm and stagnation synonymous with crisis. Coalmining in particular catalysed this transformation by requiring a huge workforce. The coal mines and iron and steel industries became the driving force behind a dazzling demographic expansion, as in the case of Seraing, where the arrival of the industrialist Cockerill saw the population rise from 2,000 to 44,000 in the space of a century. Workers, often recruited from the rural population, were employed en masse in the coal mines, which required considerable physical strength, particularly for pick-axe work before automation in the 1920s. This demand for labour contributed to a rural exodus towards these centres of industrial activity. Ironworks required large open spaces because of the weight and size of the materials handled, so they could not be established in already dense towns. Industrialisation therefore moved to the countryside, where space was available and coal was within reach. This led to the creation of vast industrial basins, radically changing the landscape as well as the social and economic structure of the regions concerned. These industrial transformations also brought profound changes to society. Daily life was radically altered, with the birth of the working class and the deterioration of living conditions due to pollution and rapid urbanisation. The "black countries" became symbols of progress, but also witnesses to the social and environmental costs of the industrial revolution.

Victor Hugo described these landscapes: "When you pass the place called Petite-Flémalle, the sight becomes inexpressible and truly magnificent. The whole valley seems to be pitted with erupting craters. Some of them spew out swirls of scarlet steam spangled with sparks behind the undergrowth; others gloomily outline the black silhouette of villages against a red background; elsewhere flames appear through the cracks in a group of buildings. You would think that an enemy army had just crossed the country, and that twenty villages had been sacked, offering you at the same time in this dark night all the aspects and all the phases of the fire, some engulfed in flames, some smoking, others blazing. This spectacle of war is given by peace; this appalling copy of devastation is made by industry. You are simply looking at Mr Cockerill's blast furnaces.

This quotation from Victor Hugo, taken from his "Journey along the Rhine" written in 1834, is a powerful testimony to the visual and emotional impact of industrialisation in Europe. Hugo, known for his literary work but also for his interest in the social issues of his time, describes here with dark and powerful lyricism the Meuse valley in Belgium, near Petite-Flémalle, marked by John Cockerill's industrial installations. Hugo uses images of destruction and war to describe the industrial scene before him. The blast furnaces light up the night, resembling erupting craters, burning villages, or even a land ravaged by an enemy army. There is a striking contrast between peace and war; the scene he describes is not the result of armed conflict but of peaceful, or at least non-military, industrialisation. The "erupting craters" evoke the intensity and violence of industrial activity, which marks the landscape as indelibly as war itself. This dramatic description underlines both the fascination and the repulsion that industrialisation can arouse. On the one hand, there is the magnificence and power of human transformation; on the other, the destruction of a way of life and an environment. The references to fires and the black silhouettes of villages project the image of a land in the grip of almost apocalyptic forces, reflecting the ambivalence of industrial progress. To put this quotation into context, we need to remember that Europe in the 1830s was in the midst of an industrial revolution. Technological innovations, the intensive use of coal and the development of metallurgy were radically transforming the economy, society and the environment. Cockerill was a leading industrial entrepreneur of this era, having developed one of the largest industrial complexes in Europe in Seraing, Belgium. The rise of this industry was synonymous with economic prosperity, but also with social upheaval and considerable environmental impact, including pollution and landscape degradation. With this quote, Victor Hugo invites us to reflect on the dual face of industrialisation, which is both a source of progress and devastation. In so doing, he reveals the ambiguity of an era when human genius, capable of transforming the world, must also reckon with the sometimes dark consequences of these transformations.

The textile towns of the Industrial Revolution represent a crucial aspect of the economic and social transformation that began in the 18th century. In these urban centres, the textile industry played a driving role, facilitated by the extreme division of labour into distinct processes such as weaving, spinning and dyeing. Unlike the heavy coal and steel industries, which were often located in rural or peri-urban areas for logistical and space reasons, textile factories were able to take advantage of the verticality of existing or purpose-built urban buildings to maximise limited floor space. These factories became a natural part of the urban landscape, helping to redefine the towns and cities of northern France, Belgium and other regions, which saw their population density increase dramatically. The transition from craft and proto-industry to large-scale industrial production led to the bankruptcy of many craftsmen, who then turned to factory work. Textile industrialisation transformed towns into veritable industrial metropolises, leading to rapid and often disorganised urbanisation, marked by unbridled construction in every available space. The massive increase in textile production was not accompanied by an equivalent increase in the number of workers, thanks to the productivity gains achieved through industrialisation. The textile towns of the time were therefore characterised by an extreme concentration of the workforce in the factories, which became the centre of social and economic life, eclipsing traditional institutions such as the town hall or public squares. Public space was dominated by the factory, which defined not only the urban landscape, but also the rhythm and structure of community life. This transformation also influenced the social composition of towns, attracting merchants and entrepreneurs who had benefited from the economic growth of the 19th century. These new elites often supported and invested in the development of industrial and residential infrastructures, thereby contributing to urban expansion. In short, textile towns embody a fundamental chapter in industrial history, illustrating the close link between technological progress, social change and the reconfiguration of the urban environment.

Two types of demographic development[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Industrial Revolution led to major migration from rural to urban areas, irreversibly transforming European societies. In the context of textile towns, this rural exodus was particularly pronounced. Craftsmen and proto-industrial workers, traditionally dispersed in the countryside where they worked at home or in small workshops, were forced to congregate in the industrial cities. This was due to the need to be close to the factories, as long journeys between home and work became impractical with the increasingly regulated work structure of the factory. The concentration of workers in cities had several consequences. On the one hand, the proximity of workers to production sites enabled more efficient management and rationalisation of the work process, leading to an explosion in productivity without necessarily increasing the number of workers employed. Indeed, innovations in production techniques, such as the use of steam engines and the automation of weaving and spinning processes, have considerably increased yields while maintaining or reducing the workforce required. In cities, the concentration of the population also led to rapid densification and urbanisation, as shown by the example of Verviers. The population of this Belgian textile town almost tripled over the course of the nineteenth century, rising from 35,000 at the start to 100,000 by the end of the century. This rapid expansion of the urban population often led to hasty urbanisation and difficult living conditions, as the existing infrastructure was rarely adequate to cope with such an influx. The concentration of the workforce also changed the social structure of cities, creating new classes of industrial workers and altering existing socio-economic dynamics. It also had an impact on the urban fabric, with the construction of housing for workers, the expansion of urban services and facilities, and the development of new forms of community life centred around the factory rather than the traditional structures of the city. Ultimately, the phenomenon of textile towns during the Industrial Revolution illustrates the transformative power of industrialisation on settlement patterns, the economy and society as a whole.

The steel regions, often referred to as 'black countries' because of the soot and pollution from factories and mines, illustrate another facet of the impact of industrialisation on demography and urban development. The black countries were centred on the coal and iron industries, which were essential catalysts for the industrial revolution. The demographic explosion in these regions was due less to an increase in the number of workers per mine or factory than to the emergence of new labour-intensive industries. Although mechanisation was progressing, it was not yet replacing the need for workers in coal mines and ironworks. For example, although the steam engine made it possible to ventilate the galleries and increase the productivity of the mines, extracting coal was still a very laborious job requiring large numbers of workers. The demographic growth in towns such as Liège, where the population rose from 50,000 to 400,000, bears witness to this industrial expansion. The coalfields and steelworks became centres of attraction for workers looking for work, leading to rapid growth in the surrounding towns. These workers were often migrants from the countryside or other less industrialised regions, attracted by the job opportunities created by these new industries. These industrial towns grew at an impressive rate, often without the planning or infrastructure needed to adequately accommodate their new population. The result was precarious living conditions, with overcrowded and unhealthy housing, public health problems and growing social tensions. These challenges would eventually lead to urban and social reforms in the following centuries, but during the Industrial Revolution, these regions were marked by rapid and often chaotic transformation.

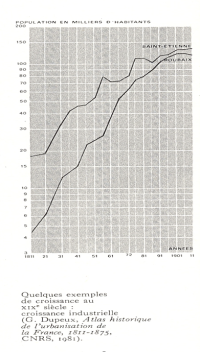

This graph shows the significant demographic growth of Saint-Étienne and Roubaix, two emblematic cities of the French industrial epic, over the period from 1811 to 1911. Over the course of the century, these towns saw their populations grow considerably as a result of rampant industrialisation. In Roubaix, the growth was particularly striking. Known for its flourishing textile industry, the town grew from fewer than 10,000 inhabitants at the start of the century to around 150,000 at its end. The labour-intensive textile industry led to a massive migration of rural populations to Roubaix, radically transforming its social and urban landscape. Saint-Étienne followed a similar upward curve, although its numbers remained lower than those of Roubaix. As a strategic centre for metallurgy and arms manufacture, the town also created a huge demand for skilled and unskilled workers, which contributed to its demographic boom. Industrialisation was the catalyst for a major social change, reflected in the metamorphosis of these small communities into dense urban centres. This transformation has not been without its difficulties: rapid urbanisation has led to overcrowding, poor housing and health challenges. The need to develop appropriate infrastructure to meet the growing needs of the population has become obvious. While the growth of these populations has stimulated the local economy, it has also raised questions about quality of life and social disparities. The evolution of Saint-Étienne and Roubaix is representative of the impact of industrialisation on the transformation of small rural communities into large modern urban centres, with their share of benefits and challenges.

Industrialisation led to the rapid and disorganised growth of industrial towns and cities, resulting in a marked contrast with the large cities that were modernising at the same time. Towns such as Seraing in Belgium, which rapidly industrialised thanks to its steelworks and mines, saw a considerable increase in their population without the urban planning necessary to accompany such expansion. These industrial towns, while having a population density equivalent to that of large cities, often lacked the corresponding infrastructure and services. Instead, their rapid growth had the characteristics of a sprawling village, with rudimentary organisation and inadequate public services, particularly in terms of public hygiene and education. The lack of infrastructure and public services was all the more problematic given the rapid growth in population. In these towns, the need for primary schools, health services and basic infrastructure far exceeded the capacity of local administrations to meet it. The finances of industrial towns were often precarious: they took on huge debts to build schools and other necessary infrastructure, as shown by the example of Seraing, which only repaid its last school building loan in 1961. The low tax base of these towns, due to the low wages of their workers, limited their ability to invest in the necessary improvements. So while the big cities were beginning to enjoy the attributes of modernity - running water, electricity, universities and efficient administrations - the industrial towns were struggling to provide basic services for their inhabitants. This situation reflects the social and economic inequalities inherent in the industrial era, where prosperity and technical progress coexisted with precarious and inadequate living conditions for a large proportion of the working population.

Housing conditions and hygiene[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The industrial revolution revolutionised urban landscapes, and textile towns are a striking example of this. These areas, already densely populated before industrialisation, had to adapt quickly to a new wave of demographic influx. This was mainly due to the concentration of the textile industry in specific urban areas, which attracted workers from all over. To meet the resulting housing shortage, towns were forced to densify existing housing. Extra storeys were often added to buildings, exploiting every available square metre, even over narrow alleyways. This impromptu modification of the urban infrastructure created precarious living conditions, as these additional constructions were not always built with the necessary safety and comfort in mind. The infrastructure of these cities, such as sanitation, water supply and waste management systems, was often insufficient to cope with the rapid increase in population. Health and education services were struggling to keep up with growing demand. This rapid, sometimes anarchic, urbanisation led to difficult living conditions, with long-term consequences for the health and well-being of residents. These challenges reflect the tension between economic development and social needs in the rapidly changing cities of the Industrial Revolution. The authorities of the time were often overwhelmed by the scale of the changes and struggled to fund and implement the public services needed to keep pace with this explosive population growth.

Dr. Kuborn was a doctor who worked in Seraing, Belgium, at the beginning of the 20th century. He witnessed at first hand the consequences of rapid industrialisation on the living conditions of workers and their families. Dr. Kuborn had a professional, and perhaps personal, interest in public health issues and urban hygiene. Doctors of the time were beginning to establish links between health and the environment, particularly the way in which substandard housing contributed to the spread of disease. They often played a key role in reforming living conditions by advocating improved urban planning, sanitation and housing standards. Dr. Kuborn shows that he was concerned about these issues and that he used his platform to draw attention to the unsanitary conditions in which the workers were forced to live.

Dr. Kuborn depicts the deplorable state of workers' housing at the time. Referring to Seraing, he reports: "Dwellings were built as they were, most of them unsanitary, without a general plan in place. Low, sunken houses, without air or light; one room on the ground floor, no pavement, no cellar; an attic as an upper floor; ventilation through a hole, fitted with a pane of glass fixed into the roof; stagnation of household water; absence or inadequacy of latrines; overcrowding and promiscuity". He mentions poorly built houses, lacking fresh air, natural light and basic sanitary conditions such as adequate latrines. This image illustrates the lack of urban planning and disregard for the welfare of workers who, because of the need to house a growing working-class population near the factories, were forced to live in deplorable conditions.

As Dr. Kuborn describes it: "It is in these insalubrious places, in these vile haunts, that epidemic diseases strike like a bird of prey swooping down on its victim. Cholera has shown us this, influenza reminds us of it, and perhaps typhus will give us a third example one of these days", he points out the disastrous consequences of these poor living conditions for the health of the inhabitants. Dr. Kuborn makes the link between unsanitary housing and the spread of epidemic diseases such as cholera, influenza and potentially typhus. The metaphor of the bird of prey swooping down on its victim is a powerful one, evoking the vulnerability of the workers who are like helpless prey in the face of the diseases proliferating in their unhealthy environment.

These testimonies are representative of living conditions in European industrial towns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They reflect the grim reality of the Industrial Revolution, which, despite its technological and economic advances, often neglected the human and social aspects, leading to public health problems and marked social inequalities. These quotations call for reflection on the importance of urban planning, decent housing and access to adequate health services for all, issues that are still topical in many parts of the world.

The development of the so-called "Black Country" regions, frequently associated with industrial areas where coal mining and steelmaking were predominant, was often rapid and disorganised. This anarchic growth was the result of accelerated urbanisation, where the need to house a large and growing workforce took precedence over urban planning and infrastructure. In many cases, living conditions in these areas were extremely precarious. Workers and their families were often housed in shanty towns or hastily constructed dwellings with little regard for durability, hygiene or comfort. These dwellings, often built without solid foundations, were not only unhealthy, but also dangerous, liable to collapse or become breeding grounds for disease. The density of the buildings, the lack of ventilation and light, and the absence of basic infrastructure such as running water and sanitation systems exacerbate public health problems. The cost of improving these areas was prohibitive, especially given their size and the poor quality of the existing buildings. As Dr. Kuborn pointed out in his comments on Seraing, setting up water and sewerage systems required major investments that local authorities were often unable to finance. Indeed, with a small tax base due to the low wages of the workers, these communities had few resources for investment in infrastructure. As a result, these communities found themselves caught in a vicious circle: inadequate infrastructure led to a deterioration in public health and quality of life, which in turn discouraged the investment and urban planning needed to improve the situation. In the end, the only viable solution often seemed to be to demolish existing structures and rebuild, a costly and disruptive process that was not always possible or achieved.

Louis Pasteur's discoveries in the mid-nineteenth century about microbes and the importance of hygiene were fundamental to public health. However, the application of these hygiene principles in industrialised urban areas was complicated by a number of factors. Firstly, anarchic urbanisation, with development carried out without proper planning, has led to the creation of unsanitary housing and a lack of essential infrastructure. Installing water and sewerage systems in already densely built-up towns was extremely difficult and costly. Unlike planned neighbourhoods, where an efficient network of pipes could serve many inhabitants in a small area, sprawling shantytowns required kilometres of piping to connect each scattered dwelling. Secondly, land subsidence due to abandoned underground mining posed considerable risks to the integrity of the new infrastructure. The pipes could easily be damaged or destroyed by these ground movements, wiping out the efforts and investment made to improve hygiene. Thirdly, air pollution exacerbated the health problems even further. Smoke from factories and furnaces literally covered the towns with a layer of soot and pollutants, which not only made the air unhealthy to breathe but also contributed to the deterioration of buildings and infrastructure. All these factors confirm the difficulty of establishing hygiene and public health standards in already established industrial urban environments, especially when they have been developed hastily and without a long-term vision. This underlines the importance of urban planning and forecasting in the management of cities, particularly in the context of rapid industrial development.

Germany, as a latecomer to the industrial revolution, has had the advantage of observing and learning from the mistakes and challenges faced by its neighbours such as Belgium and France. This enabled it to adopt a more methodical and planned approach to industrialisation, particularly with regard to workers' housing and town planning. The German authorities implemented policies that encouraged the construction of better quality housing for workers, as well as wider and better organised streets. This contrasted with the often chaotic and unhealthy conditions in industrial cities elsewhere, where rapid and unregulated growth had led to overcrowded and poorly equipped neighbourhoods. A key aspect of the German approach was a commitment to more progressive social policies, which recognised the importance of worker welfare to overall economic productivity. German industrial companies often took the initiative to build housing for their employees, with facilities such as gardens, baths and laundries, which contributed to workers' health and comfort. In addition, social legislation in Germany, such as the laws on health insurance, accident insurance and pension insurance introduced under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s, helped to establish a safety net for workers and their families. These efforts to improve workers' housing and living conditions, combined with preventive social legislation, helped Germany avoid some of the worst effects of rapid industrialisation. It also laid the foundations for a more stable society and for Germany's role as a major industrial power in later years.

Poor nutrition and low wages[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

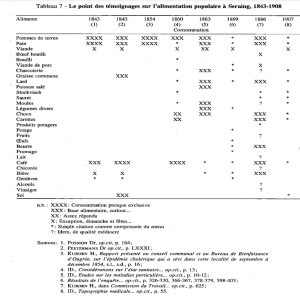

This table provides a historical window on eating habits in Seraing, Belgium, from 1843 to 1908. Each column corresponds to a specific year or period, and the consumption of different foods is coded to indicate their prevalence in the local diet. The codes range from "XXXX" for almost exclusive consumption, to "X" for lesser consumption. An asterisk "*" indicates a simple mention of the food, while annotations such as "Accessory" or "Exception, party..." suggest occasional consumption or consumption linked to particular events. Question marks "?" are used when consumption is uncertain or undocumented, and the words "of mediocre quality" suggest lower quality products at certain times. An analysis of this table reveals several notable aspects of the diet of the period. Potatoes and bread emerge as fundamental elements, reflecting their central role in the diet of the working classes in Europe during this period. Meat, with a notable presence of boiled beef and charcuterie, was consumed less regularly, which may indicate variations in income or seasonal food preferences. Coffee and chicory seem to be gaining in popularity, which could correspond to an increase in the consumption of stimulants to cope with long working hours. The mention of fats such as lard and common fat indicates a calorie-rich diet, essential to support the demanding physical work of the time. Alcohol consumption is uncertain towards the end of the period studied, suggesting changes in drinking habits or perhaps in the availability of alcoholic beverages. Fruit, butter and milk show variability that could reflect fluctuations in food supply or preferences over time. The changes in eating habits indicated by this table may be linked to the major socio-economic transformations of the period, such as industrialisation and improvements in transport and distribution infrastructures. It also suggests a possible improvement in living standards and social conditions within the Seraing community, although this would require further analysis to confirm. Overall, this table is a valuable document for understanding food culture in an industrial town, and may give some indication of the state of health and quality of life of its residents at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

The emergence of markets in industrial towns in the 19th century was a slow and often chaotic process. In these newly-formed towns, or those expanding rapidly as a result of industrialisation, the commercial structure struggled to keep pace with population growth and the influx of workers. Grocers and shopkeepers were rare and, because of their scarcity and lack of competition, they could afford to set high prices for foodstuffs and everyday consumer goods. This situation had a direct impact on the workers, the majority of whom were already living in precarious conditions, with wages often insufficient to cover their basic needs. Shopkeepers exploited workers through price gouging, driving workers into debt. This economic insecurity was exacerbated by low wages and vulnerability to economic and health hazards. Against this backdrop, companies were looking for solutions to compensate for the lack of services and shops, and to ensure a degree of control over their workforce. One such solution was the truck-system, a system of payment in kind whereby part of the workers' wages was paid in the form of foodstuffs or household goods. The company bought these products in bulk and redistributed them to its employees, often at prices determined by the company itself. The advantage of this system was that the company could retain and control its workforce, while guaranteeing an outlet for certain products. However, the truck-system had major disadvantages for the workers. It limited their freedom of choice in terms of consumption and made them dependent on the company for their basic needs. What's more, the quality of the goods supplied could be mediocre, and the prices set by the company were often high, further increasing the workers' indebtedness. The introduction of this system highlights the importance of the company in the daily lives of workers at the time, and illustrates the difficulties they faced in accessing consumer goods independently. It also reflects the social and economic dimension of industrial work, where the company is not just a place of production but also a central player in the lives of workers, influencing their food, housing and health.

The perception of the worker as immature in the nineteenth century is a facet of the paternalistic mentality of the time, when factory owners and social elites often believed that workers lacked the discipline and wisdom to manage their own welfare, particularly where finances were concerned. This view was reinforced by class prejudice and by observing the difficulties workers had in rising above the conditions of poverty and the often miserable environment in which they lived. In response to this perception, as well as to the abject living conditions of the workers, a debate began about the need for a minimum wage that would allow workers to support themselves without falling into what the elites considered depraved behaviour ('debauchery'). Debauchery, in this context, could include alcoholism, gambling, or other activities deemed unproductive or harmful to social order and morality. The idea behind the minimum wage was to provide basic financial security that could, in theory, encourage workers to lead more stable and 'moral' lives. It was assumed that if workers had enough money to live on, they would be less inclined to spend their money irresponsibly. However, this approach did not always take into account the complex realities of working-class life. Low wages, long hours and difficult living conditions could lead to behaviour that elites considered debauchery, but which could be ways for workers to cope with the harshness of their existence. The minimum wage movement can be seen as an early recognition of workers' rights and a step towards the regulation of work, although it was also tinged with condescension and social control. This debate laid the foundations for later discussions on workers' rights, labour legislation and corporate social responsibility, which continued to evolve well into the nineteenth century.

Engel's Law, named after the German economist Ernst Engel, is an empirical observation that points to an inverse relationship between household income and the proportion of it spent on food. According to this law, the poorer a household is, the greater the proportion of its limited resources it has to devote to essential needs such as food, because these expenses are incompressible and cannot be reduced beyond a certain point without affecting survival. This law has become an important indicator for measuring poverty and living standards. If a household spends a large part of its budget on food, this often indicates a low standard of living, as there is little left over for other aspects of life such as housing, health, education and leisure. In the 19th century, in the context of the industrial revolution, many workers lived in conditions of poverty and their wages were so low that they could not pay tax. This reflected not only the extent of poverty, but also the lack of financial resources available to governments to improve infrastructure and public services, as a broader tax base is often required to fund such developments. Over time, as the industrial revolution progressed and economies developed, real wages slowly began to rise. This was partly due to the increase in productivity brought about by new technologies and mechanisation, but also because of workers' struggles and demands for better working conditions and higher wages. These changes have contributed to a better distribution of wealth and a reduction in the proportion of expenditure devoted to food, reflecting an improvement in the general standard of living.

The law does not stipulate that food expenditure decreases in absolute terms as income rises, but rather that its relative share of the total budget decreases. So a better-off person or household can absolutely spend more in absolute terms on food than someone less well-off, while devoting a smaller proportion of their total budget to this category of expenditure. For example, a low-income family might spend 50% of its total income on food, while a well-off family might spend only 15%. However, in terms of the actual amount, the well-off family may spend more on food than the low-income family simply because their total income is higher. This observation is important because it makes it possible to analyse and understand consumption patterns according to income, which can be crucial for the formulation of economic and social policies, particularly those relating to taxation, food subsidies and social assistance programmes. It also provides valuable information about the socio-economic structure of the population and changes in lifestyles as living standards improve.

The ultimate judgement: the mortality of industrial populations[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The growth paradox[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The 19th century era of industrial revolution and economic expansion was a period of profound and contrasting transformations. On the one hand, there was significant economic growth and unprecedented technical progress. On the other hand, this often translated into extremely difficult living conditions for workers in rapidly expanding urban centres. One dark reality of this period needs to be highlighted: rapid, unregulated urbanisation (what some call "uncontrolled urbanisation") led to unhealthy living conditions. Industrial towns, which grew at a frenetic pace to house an ever-increasing workforce, often lacked adequate infrastructure for sanitation and access to drinking water, leading to the spread of disease and a decline in life expectancy. In cities such as the English towns of the early 19th century, Le Creusot in France in the 1840s, the region of eastern Belgium around 1850-1860, or Bilbao in Spain at the turn of the 20th century - industrialisation was accompanied by devastating human consequences. Workers and their families, often crammed into overcrowded and precarious housing, were exposed to a toxic environment, both at work and at home, with life expectancy falling to levels as low as 30 years, reflecting the harsh working and living conditions. The contrast between urban and rural areas was also marked. While the industrial cities suffered, the countryside was able to enjoy improvements in quality of life thanks to a better distribution of the resources generated by economic growth and a less concentrated, less polluted environment. This period of history poignantly illustrates the human costs associated with rapid, unregulated economic development. It underlines the importance of balanced policies that promote growth while protecting the health and well-being of citizens.

The origins of trade unionism date back to the Industrial Revolution, a period marked by a radical transformation in working conditions. Faced with long, arduous working days, often in dangerous or unhealthy environments, workers began to unite to defend their common interests. These first trade unions, often forced to operate underground because of restrictive legislation and strong employer opposition, set themselves up as champions of the workers' cause, with the aim of achieving concrete improvements in their members' living and working conditions. The trade union struggle focused on several key areas. Firstly, reducing excessive working hours and improving hygiene conditions in industrial environments were central demands. Secondly, the unions fought to obtain wages that would not only enable workers to survive, but also to live with a minimum of comfort. They also worked to ensure a degree of job stability, protecting workers from arbitrary dismissal and avoidable occupational hazards. Finally, trade unions have fought for the recognition of fundamental rights such as freedom of association and the right to strike. Despite adversity and resistance, these movements gradually won legislative advances that began to regulate the world of work, paving the way for a gradual improvement in working conditions at the time. In this way, the first trade unions not only shaped the social and economic landscape of their time, but also paved the way for the development of contemporary trade union organisations, which are still influential players in the defence of workers' rights around the world.

The low adult mortality rate in industrial towns, despite precarious living conditions, can be explained by a phenomenon of natural and social selection. The migrant workers who came from the countryside to work in the factories were often those with the best health and the greatest resilience, qualities necessary to undertake such a change of life and endure the rigours of industrial work. These adults, then, represented a subset of the rural population characterised by greater physical strength and above-average boldness. These traits were advantageous for survival in an urban environment where working conditions were harsh and health risks high. On the other hand, children and young people, who were more vulnerable because of their incomplete development and lack of immunity to urban diseases, suffered more and were therefore more likely to die prematurely. On the other hand, adults who survived the first few years of working in the city were able to develop a certain resistance to urban living conditions. This is not to say that they did not suffer from the harmful effects of the unhealthy environment and the exhausting demands of factory work; but their ability to persevere despite these challenges was reflected in a relatively low mortality rate compared with younger, more fragile populations. This dynamic is an example of how social and environmental factors can influence mortality patterns within a population. It also highlights the need for social reform and improved working conditions, particularly to protect the most vulnerable segments of society, especially children.

The environment more than work[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The observation that the environment had a greater lethal impact than work itself during the Industrial Revolution highlights the extreme conditions in which workers lived at the time. Although factory work was extremely difficult, with long hours, repetitive and dangerous work, and few safety measures, it was often the domestic and urban environment that was the most lethal. Unsanitary housing conditions, characterised by overcrowding, lack of ventilation, little or no waste disposal infrastructure and poor sewage systems, led to high rates of contagious diseases. Diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis and typhoid spread rapidly in these conditions. In addition, air pollution from burning coal in factories and homes contributed to respiratory and other health problems. Narrow, overcrowded streets, a lack of green areas and clean public spaces, and limited access to clean drinking water exacerbate public health problems. The impact of these deleterious environmental conditions was often immediate and visible, leading to epidemics and high mortality rates, particularly among children and the elderly, who were less able to resist disease. This highlighted the critical need for health and environmental reforms, such as the improvement of housing, the introduction of public health laws, and the creation of sanitation infrastructures, to improve the quality of life and health of urban populations.

The Le Chapelier law, named after the French lawyer and politician Isaac Le Chapelier who proposed it, is an emblematic law of the post-revolutionary era in France. Enacted in 1791, the law aimed to abolish the guilds of the Ancien Régime, as well as any form of professional association or grouping of workers and craftsmen. The historical context is important for understanding the reasons for this law. One of the aims of the French Revolution was to destroy feudal structures and privileges, including those associated with guilds and corporations, which controlled access to trades and could set prices and production standards. In this spirit of abolishing privileges, Le Chapelier's law aimed to liberalise labour and promote a form of equality before the market. The law also prohibited coalitions, i.e. agreements between workers or employers to set wages or prices. In this sense, it opposed the first movements of workers' solidarity, which could threaten the freedom of trade and industry advocated by the revolutionaries. However, by prohibiting any form of association between workers, the law also had the effect of severely limiting the ability of workers to defend their interests and improve their working conditions. Trade unions did not develop legally in France until the Waldeck-Rousseau law of 1884, which reversed the ban on workers' coalitions and authorised the creation of trade unions.

Immigration to industrial areas in the 19th century was often a phenomenon of natural selection, with the hardiest and most adventurous leaving their native countryside in search of better economic opportunities. These individuals, because of their stronger constitution, had a slightly higher life expectancy than the average, despite the extreme working conditions and premature physical wear and tear they suffered in the factories and mines. Early old age was a direct consequence of the arduous nature of industrial work. Chronic fatigue, occupational illnesses and exposure to dangerous conditions meant that workers 'aged' faster physically and suffered health problems normally associated with older people. For the children of working-class families, the situation was even more tragic. Their vulnerability to disease, compounded by deplorable sanitary conditions, dramatically increased the risk of infant mortality. Contaminated drinking water was a major cause of diseases such as dysentery and cholera, which led to dehydration and fatal diarrhoea, particularly in young children. Food preservation was also a major problem. Fresh produce such as milk, which had to be transported from the countryside to the towns, deteriorated rapidly without modern refrigeration techniques, exposing consumers to the risk of food poisoning. This was particularly dangerous for children, whose developing immune systems made them less resistant to food-borne infections. So, despite the robustness of adult migrants, environmental and occupational conditions in industrial areas contributed to a high mortality rate, particularly among the most vulnerable populations such as children.

Cholera epidemics[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

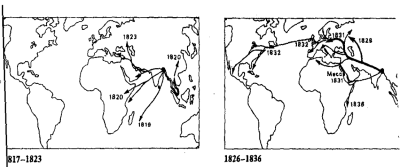

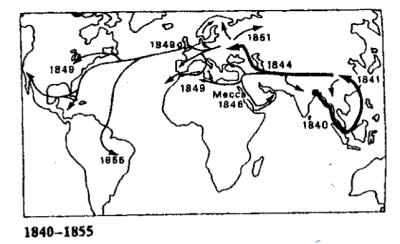

Cholera is a striking example of how infectious diseases can spread on a global scale, facilitated by population movements and international trade. In the 19th century, cholera pandemics illustrated the increasing connectivity of the world, but also the limits of medical understanding and public health at the time. The spread of cholera began with British colonisation of India. The disease, which is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, was carried by merchant ships and troop movements, following the major trade and military routes of the time. The increase in international trade and the densification of transport networks enabled cholera to spread rapidly around the world. Between 1840 and 1855, during the first global cholera pandemic, the disease followed a route from India to other parts of Asia, Russia, and finally Europe and the Americas. These pandemics hit entire cities, causing massive deaths and exacerbating the fear and stigmatisation of foreigners, particularly those of Asian origin, perceived at the time as the vectors of the disease. This stigmatisation was fuelled by feelings of cultural superiority and notions of 'barbarism' attributed to non-European societies. In Europe, these ideas were often used to justify colonialism and imperialist policies, based on the argument that Europeans were bringing 'civilisation' and 'modernity' to parts of the world considered backward or barbaric. Cholera also stimulated major advances in public health. For example, it was by studying cholera epidemics that British physician John Snow was able to demonstrate, in the 1850s, that the disease was spread by contaminated water, a discovery that led to significant improvements in drinking water and sanitation systems.

Economic growth and social change in Europe during the 19th century were accompanied by fears and uncertainties about the consequences of modernisation. With rapid urbanisation, increasing population density in cities and often unsanitary conditions, European societies were confronted with new health risks. The theory that modernity enabled 'weak' individuals to survive was widespread, reflecting an understanding of the world influenced by Darwinian ideas of survival of the fittest. This perspective reinforced fears of a possible 'degeneration' of the population if infectious diseases were to spread among those deemed less resistant. The media coverage of epidemics played a crucial role in the public perception of health risks. News of the arrival of cholera or the first victims of the disease in a particular town was often accompanied by a sense of urgency and anxiety. Newspapers and broadsheets of the time carried this information, exacerbating fear and sometimes panic among the population. The disease also highlighted glaring social inequalities. Cholera disproportionately affected the poor, who lived in more precarious conditions and could not afford good hygiene or adequate food. This difference in mortality between social classes highlighted the importance of the social determinants of health. As for resistance to cholera thanks to a rich diet, the idea that gastric acids kill the cholera virus is partially true in the sense that a normal gastric pH is a defence factor against colonisation by vibrio cholerae. However, it is not a question of eating meat versus bread and potatoes. In fact, people who were malnourished or hungry were more vulnerable to disease, because their immune systems were weakened and their natural defences against infection were less effective. It is important to stress that cholera is not caused by a virus, but by bacteria, and that the survival of the micro-organism in the stomach depends on various factors, including the infectious load ingested and the person's general state of health. These epidemics have forced governments and societies to pay increased attention to public health, leading to investment in improved living conditions, sanitation and drinking water infrastructure, and ultimately to a reduction in the impact of such diseases.

The great epidemics that struck France and other parts of Europe after the revolutions of 1830 and 1848 took place against a backdrop of profound political and social upheaval. These devastating diseases were often perceived by the underprivileged classes as scourges exacerbated, or even provoked, by the miserable living conditions in which they were forced to live, often close to urban centres undergoing rapid expansion and industrialisation. In such a climate, it is not surprising that the suspicion and anger of the working classes was directed at the bourgeoisie, which was accused of negligence and even malice. Conspiracy theories such as the accusation that the bourgeoisie sought to "poison" or suppress "popular fury" through disease resonated with a population desperate for explanations for its suffering. In Russia, during the reign of the Tsar, demonstrations triggered by the distress caused by epidemics were put down by the army. These events reflect the tendency of the authorities of the time to respond to social unrest with force, often without addressing the root causes of discontent, such as poverty, health insecurity and lack of access to basic services. These epidemics highlighted the links between health conditions and social and political structures. They have shown that public health problems cannot be dissociated from people's living conditions, particularly those of the poorest classes. Faced with these health crises, pressure mounted on governments to improve living conditions, invest in health infrastructure and implement more effective public health policies. These periods of epidemics therefore also played a catalytic role in the evolution of political and social thought, underlining the need for greater equality and for governments to take better care of their citizens.

Nineteenth-century doctors were often at the heart of health crises, acting as figures of trust and knowledge. They were seen as pillars of the community, not least because of their commitment to the sick and their scientific training, acquired in higher education establishments. These health professionals had great influence and their advice was generally respected by the population. Before Louis Pasteur revolutionised medicine with his germ theory in 1885, understanding of infectious diseases was very limited. Doctors of the time were unaware of the existence of viruses and bacteria as pathogens. Despite this, they were not devoid of logic or method in their practice. When faced with diseases such as cholera, doctors used the knowledge and techniques available at the time. For example, they carefully observed the evolution of symptoms and adapted their treatment accordingly. They tried to warm patients during the "cold" phase of cholera, characterised by cold, bluish skin due to dehydration and reduced blood circulation. They also tried to fortify the body before the onset of the "last phase" of the disease, often marked by extreme weakness, which could lead to death. Physicians also used methods such as bloodletting and purging, which were based on medical theories of the time but are now considered ineffective or even harmful. However, despite the limitations of their practice, their dedication to treating patients and rigorously observing the effects of their treatments testified to their desire to combat disease with the tools at their disposal. The empirical approach of doctors of this era contributed to the accumulation of medical knowledge, which was subsequently transformed and refined with the advent of microbiology and other modern medical sciences.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, known as Baron Haussmann, orchestrated a radical transformation of Paris during the Second Empire, under the reign of Napoleon III. His task was to remedy the pressing problems of the French capital, which was suffering from extreme overcrowding, deplorable sanitary conditions and a tangle of alleyways dating back to the Middle Ages that no longer met the needs of the modern city. Haussmann's strategy for revitalising Paris was comprehensive. He began by taking measures to clean up the city. Before his reforms, Paris struggled with plagues such as cholera, exacerbated by narrow streets and a poor sewage system. He introduced an innovative sewage system that greatly improved public health. Haussmann then focused on improving infrastructure by establishing a network of wide avenues and boulevards. These new thoroughfares were not just aesthetically pleasing but functional, improving the circulation of air and light and making it easier to get around. At the same time, Haussmann rethought the city's urban planning. He created harmonious spaces with parks, squares and alignments of facades, giving Paris the characteristic appearance we know today. However, this process had major social repercussions, notably the displacement of the poorest populations to the outskirts. The renovation work led to the destruction of many small businesses and precarious dwellings, forcing the poorer classes to move to the suburbs. These changes provoked mixed reactions among Parisians at the time. While the bourgeoisie might have feared social unrest and viewed with apprehension the presence of what they saw as the "dangerous classes", Haussmann's ambition was also to make the city more attractive, safer and better adapted to the times. Nevertheless, the cost and social consequences of Haussmann's work were a source of controversy and intense political debate.

The "social question"[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

During the 19th century, with the rise of industrial capitalism, social structures underwent radical changes, replacing the old hierarchy based on nobility and blood with one based on social status and wealth. A new bourgeois elite emerged, made up of individuals who, having succeeded in the business world, acquired the wealth and social credit deemed necessary to govern the country. This elite represented a minority who, for a time, held a monopoly on the right to vote, being considered the most capable of taking decisions for the good of the nation. The workers, on the other hand, were often seen in a paternalistic light, as children incapable of managing their own affairs or resisting the temptations of drunkenness and other vices. This view was reinforced by the moral and social theories of the time, which emphasised temperance and individual responsibility. Fear of cholera, a dreadful and poorly understood disease, fuelled a range of popular beliefs, including the idea that stress or anger could induce illness. This belief contributed to a relative calm among the working classes, who were wary of strong emotions and their potential to cause plagues. In the absence of a scientific understanding of the causes of such illnesses, theories abounded, some of them based on myth or superstition. In this environment, the bourgeoisie developed a form of paranoia about working-class suburbs. The urban peripheries, often overcrowded and unhealthy, were seen as hotbeds of disease and disorder, threatening the stability and cleanliness of the more sanitised urban centres. This fear was accentuated by the contrast between the living conditions of the bourgeois elite and those of the workers, and by the perceived threat to the established order posed by popular gatherings and revolts.

Buret was a keen observer of the living conditions of the working class in the 19th century, and his analysis reflects the social anxieties and criticisms of an era marked by the Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanisation: "If you dare to enter the cursed districts where [the working-class population] live, you will see at every step men and women withered by vice and misery, half-naked children rotting in filth and suffocating in dayless, airless rooms. There, in the home of civilisation, you will meet thousands of men who, by dint of stupefaction, have fallen back into the savage life; there, finally, you will see misery in such a horrible aspect that it will inspire more disgust than pity, and that you will be tempted to see it as the just punishment for a crime [...]. Isolated from the nation, placed outside the social and political community, alone with their needs and their miseries, they are agitating to get out of this frightening solitude, and, like the barbarians to whom they have been compared, they may be plotting an invasion".

The strength of this quotation lies in its graphic and emotional depiction of poverty and human degradation in the working-class districts of industrial cities. Buret uses shocking imagery to elicit a reaction from the reader, depicting scenes of degradation that stand in stark contrast to the ideal of progress and civilisation held by the times. By describing working-class neighbourhoods as "cursed" and evoking images of men and women "withered by vice and misery", he draws attention to the inhuman conditions created by the economic system of the time. The reference to "half-naked children rotting in the dirt" is particularly poignant, reflecting a cruel social reality in which the most vulnerable, children, were the first victims of industrialisation. The reference to "dayless, airless rooms" is reminiscent of the insalubrious, overcrowded dwellings in which working-class families were crammed. Buret also highlights the isolation and exclusion of workers from the political and social community, suggesting that, deprived of recognition and rights, they could become a subversive force, compared to "barbarians" plotting an "invasion". This metaphor of invasion suggests a fear of workers' revolt among the ruling classes, who feared that the distress and agitation of the workers would turn into a threat to the social and economic order. In its historical context, this quotation illustrates the deep social tensions of the 19th century and offers a scathing commentary on the human consequences of industrial modernity. It invites reflection on the need for social integration and political reform, recognising that economic progress cannot be disconnected from the well-being and dignity of all members of society.