The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973)

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

The period of the Trente Glorieuses, from 1945 to 1973, represented an era of major economic and social transformation for developed countries, particularly those that were members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This period, marked by exceptional economic growth, was closely linked to post-war reconstruction and the emergence of new economic and social paradigms.

The impact of the Second World War, with its massive destruction and colossal human and economic costs, laid the foundations for a worldwide reconstruction effort. The devastated economies of Europe and Asia enjoyed a remarkable renaissance, supported by initiatives such as the Marshall Plan and the establishment of new international economic institutions. At the same time, Keynesian policies were adopted, favouring state intervention to stimulate demand and support employment.

The example of the German "miracle" is a perfect illustration of this renaissance. Thanks to international aid, notably the Marshall Plan, and the introduction of the "soziale Marktwirtschaft" (social market economy), Germany underwent a remarkable economic transformation, characterised by an economic policy combining liberalism and interventionism, an emphasis on investment and wage moderation, and an openness to free trade and European integration. Countries such as Switzerland also followed similar economic models, reflecting a common economic and social development in Europe.

At the same time, the United States underwent its own transformation, with the development of the consumer society. This period saw a revolution in lifestyles, marked by improvements in public services and household appliances, freeing up time for consumption and stimulating a flourishing leisure economy. The consumer society, analysed critically by economists such as John Kenneth Galbraith, called into question the relationship between material well-being and the satisfaction of basic human needs.

Understanding the Glorious Thirty: Definition and Context[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The "Glorious Thirty" refers to the period of strong economic growth experienced by most developed countries, many of them members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), between 1945 and 1973. This era is notable for its exceptional economic growth, technological innovations and improved living standards. The period saw the rebuilding of many nations after the devastation of the Second World War, fuelled by factors such as the Marshall Plan, increased world trade and technological advances. It was a time of rapid industrialisation, urbanisation and the expansion of the welfare state in many countries. This era also witnessed the emergence of a consumer culture, with significant increases in household incomes leading to greater consumer spending on goods and services. This period is often contrasted with the economic challenges and stagnation that many of these countries experienced in the following years, underlining the unique and exceptional nature of the 'Trente Glorieuses'.

The expression "Les Trente Glorieuses" was coined by the economist Jean Fourastié. He used it in his book "Les Trente Glorieuses ou la révolution invisible de 1946 à 1975", published in 1979. This expression draws a parallel with the "Trois Glorieuses", the revolutionary days of 27, 28 and 29 July 1830 in France, which led to the fall of King Charles X. In his book, Fourastié analyses the period of profound economic and social transformation that France and other developed countries experienced after the Second World War. He highlights how this period, although less visible or dramatic than the political revolutions, had a revolutionary impact on society, the economy and culture. The term 'invisible revolution' therefore reflects the substantial and lasting changes that took place over these thirty years, marking an era of unprecedented prosperity and progress.

From Destruction to Prosperity: Post-War Economic Growth[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Economic Repercussions of the Second World War[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

A comparison of the First and Second World Wars reveals a dramatic increase in violence and social upheaval. During the First World War, the death toll was estimated at between 14 and 16 million people, an already tragic figure that reflects the extent of human loss across the world. However, during the Second World War, this number rose alarmingly to between 37 and 44 million, including a large number of civilians, underlining the unprecedented brutality of the conflict. In terms of population displacement, the First World War saw between 3 and 5 million people displaced, a phenomenon resulting directly from the fighting and changes in borders. But the Second World War saw this number rise considerably, with 28 to 30 million people displaced. This increase can be explained by the intensity of the fighting on several fronts, ethnic and political persecution, and post-war territorial readjustments. These figures illustrate the intensification of violence between the two wars and put into perspective the profound and lasting impact of the Second World War, especially on Europe, which was one of the main theatres of conflict. The consequences of this war shaped the world order in the decades that followed, paving the way for periods such as the Trente Glorieuses, marked by an era of reconstruction and economic and social renewal.

The devastating impact of the Second World War on the global economy is often underestimated, especially when compared with the immense human loss. Estimates by economists suggest that the destruction caused by the war resulted in a decline equivalent to 10 to 12 years of production to reach the economic level of 1939. This perspective highlights not only the scale of the material damage, but also the depth of the resulting economic crisis. The war ravaged essential infrastructure, destroyed industrial capacity and paralysed transport networks. This damage was not limited to the loss of material goods; it also represented a colossal delay in the potential for economic development. Ruined towns, devastated factories and disrupted communication lines are just a few examples of the major obstacles to economic recovery. The task of reconstruction was of unprecedented complexity and scale, requiring concerted efforts on an international scale, as illustrated by the Marshall Plan. Recovery to the 1939 level of production was not simply a matter of physical reconstruction. It involved an overhaul of the economy, social reorganisation and political modernisation. These challenges were met with remarkable resilience, laying the foundations for an unprecedented period of prosperity. The Trente Glorieuses that followed were not just the result of economic recovery, but also a testament to the extraordinary capacity of societies to rebuild, reinvent themselves and move forward after a period of profound adversity. This underlines the importance of resilience and innovation in post-conflict reconstruction.

The dramatic situation after the Second World War was part of a political context that was profoundly transformed by the emergence of a bipolar world, dominated by two ideologically opposed superpowers: the United States, representing the liberal world, and the Soviet Union, embodying the Soviet bloc. This new geopolitical structure marked the beginning of an era of tension and rivalry known as the Cold War. The confrontation between these two blocs did not materialise in a direct war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but rather through local wars and proxy conflicts. These proxy confrontations took place in various parts of the world, where the two superpowers supported opposing sides in order to spread their respective influence and ideologies. The end of the Second World War thus marked the beginning of an opposition between the Soviet bloc and the Atlanticist bloc, led by the United States. This opposition shaped international politics for several decades, resulting in the division of the world into two distinct and often antagonistic spheres of influence. The impact of this bipolarity extended far beyond foreign policy, influencing the domestic politics, economies and even cultures of the countries involved. This period of world history was characterised by a series of crises and confrontations, including the arms race, the Cuban missile crisis, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. These events illustrate the complex and often perilous nature of the Cold War, when the world regularly seemed to be on the brink of large-scale nuclear conflict. The bipolar dynamic that emerged after the Second World War profoundly redefined international relations, creating a world divided and often in conflict, the repercussions of which are still felt in contemporary world politics.

Post-War Reconstruction: A Global Challenge[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Reconstruction after the Second World War, which took place surprisingly quickly in just 3 to 4 years, contrasts sharply with the period of reconstruction after the First World War, which took between 7 and 9 years. This notable difference in the speed of reconstruction can be attributed to several key factors. Firstly, the scale and nature of the destruction caused by the two wars were different. Although the Second World War was more devastating in terms of loss of life and material destruction, the nature of the destruction often enabled faster reconstruction. For example, bombing destroyed infrastructure, but sometimes left industrial bases intact, allowing production to resume more quickly. Secondly, the experience of the First World War undoubtedly played a role. Nations already had some experience of reconstruction after a major conflict, which may have contributed to better planning and execution of reconstruction efforts after the Second World War. Thirdly, external aid, in particular the Marshall Plan, had a significant impact. This programme, set up by the United States to help rebuild Europe, provided funds, equipment and support, speeding up the reconstruction process. The Marshall Plan not only helped to rebuild physically, but also helped to stabilise European economies and promote political and economic cooperation between European countries. Finally, the rapid reconstruction after the Second World War can also be attributed to a greater sense of urgency and political commitment. Having suffered two major wars in the space of a few decades, there was a strong desire, both nationally and internationally, to rebuild quickly and create more stable structures to prevent future conflict.

The Marshall Plan, officially known as the European Recovery Programme, was a crucial initiative in the reconstruction of Europe after the Second World War. With a budget of 13.2 billion dollars allocated for the period 1948 to 1952, the plan represented around 2% of the total wealth of the United States at the time, illustrating the scale of the American commitment to European reconstruction. The plan had a significant strategic dimension. In 1947, US Secretary of State George C. Marshall made a strong appeal for the United States to become actively involved in the reconstruction of Western Europe. The main objective was to create a "defensive glacis" against the expansion of the Soviet bloc in Europe. At the time, the Cold War was beginning to take shape, and the Marshall Plan was seen as a way of countering Soviet influence by helping European nations to rebuild themselves economically and socially, making them less likely to fall under Communist influence. The Marshall Plan had a profound and lasting effect on Europe. Not only did it help in the rapid reconstruction of infrastructure, industry and national economies, but it also played a key role in the political stabilisation of Western Europe. In addition, it strengthened economic and political ties between the United States and European nations, laying the foundations for transatlantic cooperation that continues to influence international relations. By providing financial resources, equipment and advice, the Marshall Plan contributed to Europe's rapid post-war recovery, supporting not only material reconstruction but also the strengthening of democratic institutions and European economic integration. This commitment had an undeniable impact on the political and economic landscape of post-Second World War Europe, and was instrumental in preventing the spread of communism in Western Europe.

The post-Second World War era saw the establishment of a new international economic order, largely dominated by the United States. This restructuring was initiated by a number of major agreements and institutions, which laid the foundations for modern economic practices and shaped the global economy in the decades that followed. A key element of this new order was the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, which established the rules for financial and trade relations between the world's most industrialised countries. This conference gave birth to two major institutions: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which became part of the World Bank. The purpose of these institutions was to stabilise exchange rates, assist reconstruction and economic development, and promote international trade. The Bretton Woods system also instituted fixed exchange rates, with currencies pegged to the US dollar, which was itself convertible into gold. This structure placed the United States at the heart of the world economy, with its dollar becoming the main international reserve currency. The GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) agreements of 1947 also played a crucial role. Their aim was to reduce customs barriers and promote free trade, thereby contributing to an increase in international trade and global economic integration. These initiatives, most of which were supported by the United States, not only helped to rebuild the economies devastated by the war, but also paved the way for the era of economic globalisation. They solidified the position of the United States as the dominant economic superpower, influencing economic and trade policies around the world. The post-war era saw the establishment of a new international economic order, characterised by strong institutions, stabilising rules for financial and trade exchanges, and US economic hegemony, which profoundly shaped the global economy for decades to come.

The Bretton Woods Agreement, signed in July 1944, was a crucial turning point in world economic history. They marked the birth of a "new world" by establishing an institutional framework to regulate the international economy, a framework that remains influential to this day. These agreements led to the creation of two major institutions: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), later integrated into the World Bank Group, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IBRD's role was to facilitate post-war reconstruction and promote economic development, while the IMF's aim was to oversee the international monetary system, helping to stabilise exchange rates and providing a platform for international economic consultation and cooperation. A key element of the Bretton Woods agreements was the establishment of the US dollar as the reference currency for international trade. The currencies of member countries were pegged to the dollar, which was itself convertible into gold. This decision not only stabilised exchange rates, but also secured the value of international trade, which was crucial to post-war economic reconstruction and growth. The Bretton Woods agreements can be seen as the result of an intellectual and political drive to avoid the mistakes of the past, particularly those that led to the economic crisis of the 1930s and the Second World War. By establishing mechanisms for economic cooperation and creating stable institutions for the management of global economic affairs, these agreements laid the foundations for a period of unprecedented economic growth and stability. In this way, the Bretton Woods agreements and the institutions they created played a decisive role in shaping the world economic order of the twentieth century, shaping economic policies and practices on a global scale and establishing a framework that continues to influence the management of the international economy.

The GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), signed in January 1948, marked an important milestone in the establishment of an international trading system based on free trade principles. The main aim of this treaty was to reduce tariff barriers and limit recourse to protectionist policies, thereby encouraging greater openness of international markets. The GATT was conceived in a spirit of international economic cooperation, with the intention of facilitating steady economic growth and promoting job creation in the post-war period. It provided a regulatory framework for international trade negotiations, contributing to the gradual reduction in customs duties and the significant increase in world trade. In 1994, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) was created, succeeding the GATT. The WTO expanded the GATT framework to include not only trade in goods, but also trade in services and intellectual property rights. This transition from the GATT to the WTO represented a move towards a more formal and structured institution to oversee international trade. At the same time, these trade agreements came at a time when economic policies were largely influenced by Keynesian ideas. The economist John Maynard Keynes advocated active state intervention in the economy to regulate aggregate demand, particularly in times of recession. These Keynesian policies, which focused on stimulating employment and demand through public spending and monetary regulation, played a significant role in post-war reconstruction and economic growth. Thus, the GATT, and subsequently the WTO, in tandem with Keynesian economic policies, shaped a new era of international trade and economic management. These initiatives helped to stabilise and energise the world economy in the decades following the Second World War, laying the foundations for the economic interdependence and globalisation we know today.

Stability and Acceleration of Economic Growth[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Economic growth in developed countries has accelerated markedly over the centuries, peaking in the post-war period, particularly between 1950 and 1973. In the initial phase from 1750 to 1830, corresponding to the era of proto-industry, average annual economic growth was around 0.3%. This period marked the beginnings of industrialisation, with the introduction of new technologies and production methods, although these changes were gradual and geographically limited. The period from 1830 to 1913 saw a marked acceleration in growth, averaging 1.3%. This era was characterised by the generalisation and spread of the industrial revolution, particularly on the European continent. The adoption of advanced technologies, the expansion of international trade and rapid urbanisation all contributed to this increase in production and income. Between 1920 and 1939, growth increased further, reaching an average of 2.0%. This period was marked by the introduction and spread of Taylorism, a scientific method of work management, and by the pioneering role of Fordism, which revolutionised mass production techniques and product standardisation, particularly in the car industry. However, it was after the Second World War, between 1950 and 1973, that economic growth reached unprecedented levels, averaging 3.9%. This period, often referred to as the "Trente Glorieuses", was marked by rapid and sustained growth, exceptional economic stability and an absence of major economic crises. Factors contributing to this growth included post-war reconstruction, technological innovation, increased productivity, the expansion of international trade and the adoption of Keynesian economic policies. This historical progression of economic growth illustrates the evolution of technologies, production methods and economic policies, with the post-World War II period representing a peak in this trajectory, characterised by a unique combination of favourable factors that led to historic economic expansion.

The period of strong economic growth between 1950 and 1973, known as the "Trente Glorieuses", was marked by significant geographical disparities in terms of per capita GNP (Gross National Product) growth. Although the developed countries as a whole experienced impressive growth averaging 3.9% a year, growth rates varied considerably from region to region. In Western Europe, GNP per capita growth averaged 3.8%, reflecting the successful reconstruction after the Second World War and the increasing economic integration between European countries. This growth was underpinned by significant investment in infrastructure, technological innovation and the expansion of trade, partly as a result of the Marshall Plan and the establishment of the European Economic Community. In the United States, per capita GNP growth was more modest, at around 2.1%. Despite this slower growth compared to other regions, the US remained a dominant economy, benefiting from a solid industrial base, strong domestic consumption and a leading position in technological and scientific innovation. Japan, on the other hand, saw its per capita GNP grow at a dazzling rate of 7.7%. This spectacular growth is the result of its rapid modernisation process, effective industrial policy and export orientation, making Japan one of the most remarkable examples of post-war economic development. Finally, Eastern Europe also posted high growth rates, fluctuating between 6% and 7%. These economies, although operating under a different economic model due to their alignment with the Soviet bloc, also benefited from a period of industrial growth and improvements in living standards, even if this growth was often accompanied by political and economic constraints. This period therefore showed that, despite a general trend towards economic growth, growth rates in GNP per capita varied considerably from one region to another, reflecting the diversity of economic, political and social contexts in the post-war developed world.

The strong economic growth in Eastern Europe during the Trente Glorieuses period can be attributed in part to the initial situation of these countries. Being poorer than their Western European neighbours, these nations benefited from what is known as the economic catch-up effect. The systematic destruction suffered during the Second World War necessitated large-scale reconstruction, providing an opportunity for rapid modernisation and industrialisation. This reconstruction, often directed by centralised economic plans typical of the communist regimes of the time, led to a significant increase in economic activity and high growth rates. As for Japan, its economic rise after the Second World War is remarkable and is often compared to historical attempts at modernisation, such as that of Egypt under Mehmet Ali in the nineteenth century. Unlike Egypt at that time, which experienced difficulties in its efforts to modernise and industrialise, Japan succeeded in transforming itself into a major economic power. This success is due to a combination of factors, including major structural reforms, strong political will, a skilled and disciplined workforce, and an effective strategy focused on exports and technological innovation. The Japanese case is exemplary in that it was able not only to rebuild its war-torn economy, but also to redirect it towards rapid and sustainable growth. Japan benefited from American aid in the immediate post-war period, but it was above all thanks to its own industrial policies and its commitment to education and research and development that it was able to establish a solid base for economic growth. In just a few decades, Japan has gone from a war-torn nation to one of the most advanced and innovative economies in the world.

The period of reconstruction after the Second World War played a crucial role in boosting the economy and significantly improving living standards, leading to what might be termed 'life security' for a large proportion of the population in developed countries. This era has seen a significant decline in poverty, thanks to rapid and sustained economic growth and the creation and expansion of the welfare state. The social security systems put in place during this period were essential in providing a safety net for citizens, offering protection against economic and social risks such as sickness, old age, unemployment and poverty. These systems included health insurance, retirement pensions, unemployment benefits and other forms of social assistance. Their development reflected a new approach to governance, in which the state took a more active role in guaranteeing the well-being of its citizens. This development was partly inspired by Keynesian ideas, which advocated greater state intervention in the economy to regulate demand and ensure economic stability. In addition, economic growth led to higher wages and better working conditions, contributing to a general rise in living standards. Increased access to education and healthcare has played an important role in improving quality of life and social mobility. Overall, the post-war reconstruction period marked a transition towards more prosperous and equitable societies in developed countries. The rise of the welfare state, combined with unprecedented economic growth, not only helped to repair the damage of war, but also laid the foundations for an era of prosperity and security for millions of people.

The development of the consumer society in the post-war period played a fundamental role in establishing a consumption and production dynamic that contributed significantly to economic growth. This period was marked by a significant increase in demand for, and accessibility to, everyday consumer goods such as household equipment and means of transport. Rising incomes, combined with the mass production made possible by technological advances and efficient production methods such as Fordism, made consumer goods more affordable for a greater number of people. Household items such as fridges, washing machines and televisions became commonplace in homes, symbolising a rise in living standards. Similarly, means of transport, particularly cars, have undergone massive expansion. The car became not only a means of transport but also a symbol of status and independence. The democratisation of the car brought about significant changes in lifestyles, encouraging individual mobility and contributing to the expansion of suburbs. This consumer society has also stimulated production. Growing demand for consumer goods encouraged companies to increase production, which in turn led to economic growth. It also encouraged product innovation and diversification, as companies sought to respond to changing consumer needs and desires. Advertising and marketing played a key role in this era, encouraging consumption and shaping consumer desires. Mass media, such as television, have enabled advertising messages to be disseminated more widely and more effectively, contributing to the growth of consumer culture. The development of the consumer society in the post-war period created a powerful economic dynamic, characterised by increased demand for consumer goods, increased mass production, and overall economic growth. This period laid the foundations for the modern market economy and profoundly influenced lifestyles and cultures in developed countries.

In the post-war period, the United States assumed the role of leader of the Atlanticist bloc, but in terms of economic growth, its performance was not as exceptional as that of Western Europe. This may seem surprising, given the dominant position of the United States on the world economic and political stage. One of the main reasons for this difference lies in the catch-up effect enjoyed by Western Europe. Having suffered massive destruction during the Second World War, European countries were in a phase of intense reconstruction and modernisation. This reconstruction dynamic led to rapid growth, especially with the support of the Marshall Plan, which helped to modernise infrastructure and industry. Starting from a weaker economic base, Europe thus had greater growth potential. In contrast, the United States, which had not suffered any destruction at home, already had an advanced economy with its infrastructure largely intact after the war. This limited its growth potential compared with Europe, which was rebuilding and modernising. In addition, the US economy had already expanded significantly during the war, and the transition from a war economy to a peace economy presented its own challenges. Economic integration also played a key role in Europe, notably with the creation of the European Economic Community. This integration has stimulated trade and economic cooperation between European countries, fostering their growth. Europe has also been the scene of major economic innovations and reforms, contributing to an acceleration in its economic growth.

The exceptional economic growth of the post-war period can be attributed to a combination of global economic factors. Firstly, the liberalisation of international trade played a crucial role. The GATT agreements encouraged free trade by reducing tariff barriers and establishing rules for international trade. At the same time, the Bretton Woods system provided essential monetary stability by pegging currencies to the US dollar, which was itself convertible into gold. These elements created an environment conducive to world trade, facilitating economic growth. At the same time, the transport revolution, particularly in the naval and air transport sectors, enabled international trade to expand rapidly. Improvements in the efficiency and capacity of sea and air transport reduced costs and delays, enabling the exchange of goods on an unprecedented scale and speed. The period was also marked by what is known as the Third Industrial Revolution, characterised by the emergence of new technological sectors such as electronics, automation and the harnessing of atomic energy. These advances have not only created new markets and employment opportunities, but have also stimulated innovation and efficiency in many other sectors of the economy. Moreover, the Cold War arms race had a paradoxical effect on the global economy. On the one hand, it supported traditional defence and arms-related industries, preserving older sectors. On the other, it has stimulated the development of cutting-edge technologies, particularly in aerospace and electronics. This dynamic has encouraged both the preservation of existing industries and the emergence of new, innovative sectors. These factors combined to create an era of unprecedented economic growth, characterised by an expansion in international trade, major technological innovations, and a mix of development in traditional and cutting-edge sectors. This synergy helped shape the post-war global economy, laying the foundations for the prosperity and economic development we enjoy today.

The German "Miracle": Recovery and Success for Defeated Countries[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The "Wirtschaftswunder" or German economic miracle, which took place between 1951 and 1960, is a remarkable phenomenon in German economic history. During this decade, the country experienced impressive growth of 9% per annum, a rate that far exceeded expectations and marked a rapid and robust recovery from the massive destruction of the Second World War. The key to this success has been the adoption of a unique economic model, known as the social market economy. This innovative model effectively merged the principles of free enterprise with a strong social policy component. By putting this model into practice, Germany has succeeded in stimulating private initiative and market competitiveness while ensuring social justice and security for its citizens. This balanced approach not only fostered rapid economic growth, but also ensured a fairer distribution of wealth, thereby contributing to lasting political and social stability.

The currency reform of 1948, which saw the introduction of the Deutsche Mark, played a crucial role in stabilising the German economy. This reform not only helped to keep inflation under control, but also restored confidence in the country's financial system, creating an environment conducive to investment and economic growth. Germany has also benefited from significant investment in its reconstruction, thanks in particular to the Marshall Plan. This investment was crucial in rebuilding the destroyed infrastructure and revitalising German industry, laying the foundations for a rapid and sustainable economic recovery. Germany's integration into the European economy, notably through its membership of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and later the European Economic Community (EEC), also played an important role. The opening up of new markets and the facilitation of trade across these economic blocs stimulated economic growth in Germany. Finally, the implementation of social policies has ensured a degree of equality and security, playing an important role in stabilising German society. These policies, including benefits such as retirement pensions and health insurance, have not only improved the quality of life of citizens, but have also contributed to the country's political and social stability. The German economic miracle demonstrates the effectiveness of an economic approach that effectively combines free market principles with a solid social policy. This model not only enabled Germany to rebuild rapidly after the war, but also transformed it into one of the most powerful and stable economies in the world.

The Impact of International Aid[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

From 1947, in the context of the emerging Cold War, Allied policy towards West Germany underwent a significant change. The penalties imposed on Germany after the Second World War began to be suspended. This decision was largely motivated by the desire to counter Soviet influence and domination in Eastern Europe and to integrate West Germany into the Western liberal camp. This strategy was part of a wider policy of containing Communism, aimed at limiting the expansion of Soviet influence in Europe and the rest of the world. Against this backdrop, the Marshall Plan, officially named the European Recovery Programme, was introduced in 1948. The aim of this programme was to support the reconstruction of European countries ravaged by war, including Germany. A significant sum of 1.5 billion dollars was allocated to the German economy as part of this plan. Investment in the reconstruction of Germany was intended not only to re-establish the country as an economic power, but also to solidify it as an important strategic partner in the Western bloc against the USSR. The Marshall Plan played a crucial role in revitalising the German economy. By providing the funds needed to rebuild infrastructure, revitalise industry and stimulate economic growth, the plan helped Germany recover quickly from the ravages of war. In addition, West Germany's integration into the Western economy strengthened its position as a key member of the Western bloc, contributing to the political and economic stabilisation of the region in the face of the Communist bloc.

The emergence of "Soziale Marktwirtschaft" in Germany[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The economic and political thinking that guided Germany's reconstruction after the Second World War had its roots in the ideas of liberal German intellectuals, in particular in a school of thought known as 'ordo-liberalism'. This movement, which emerged in the 1930s and 1940s, represented a response to the economic and political challenges of the time, in particular the rise of Nazism and totalitarianism. Ordo-liberalism differed from traditional forms of liberalism mainly in that it was constructed in opposition to Nazism. Whereas classical liberalism often developed in reaction to left-wing policies and state expansion, post-war German ordo-liberalism sought to establish a third way, distinct from both totalitarianism and state socialism.

This school of thought recognised a legitimate and active role for the state, not as a centralised agent of control, but as a regulator and guarantor of market order. Ordo-liberals argued that the state should create a legal and institutional framework that allowed the market economy to function efficiently and fairly. This approach implied careful regulation of markets to prevent monopolies and abuses of economic power, while preserving competition and private initiative. Ordo-liberalism also incorporated a significant social dimension, emphasising the importance of social policy in ensuring stability and justice within a market economy. This vision led to the creation of a social security system and the adoption of policies designed to guarantee a degree of equality of opportunity and to protect citizens against economic risks.

Founded on a broad anti-communist consensus, ordo-liberalism played a crucial role in the post-war reconstruction of Germany, strongly influencing the economic policy of the Wirtschaftswunder era. This new form of liberalism helped shape a German economy that was not only prosperous and internationally competitive, but also socially responsible and stable.

Distinguishing between the Legal Framework and the Economic Process[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The economic approach adopted by Germany in the post-war period, strongly influenced by ordo-liberalism, emphasised the regulatory role of the state while preserving the principles of the market economy. This strategy focused on a number of key areas, demonstrating a balance between state intervention and free competition. Firstly, the State played a crucial role in imposing and enforcing economic rules. This included putting in place policies to ensure competition in markets to avoid the formation of monopolies, which could distort the market economy. By ensuring that the rules of competition were respected, the State helped to create a healthy and fair economic environment. At the same time, the State ensured that contracts were respected, thereby reinforcing confidence in commercial transactions and business relationships. This state guarantee was essential to maintaining order and predictability in the economy. In terms of monetary policy, the State guaranteed the stability of the currency. A stable currency is crucial to a healthy economy, as it reduces uncertainty for investors and consumers, and helps to control inflation. Investment in education and scientific research has also been a central pillar of German economic strategy. The government has encouraged the development of technical universities and the training of high-quality technicians. This focus on education and research has made it possible to develop a pool of highly skilled and innovative workers, crucial to the competitiveness of the German economy on the global market. These policies have enabled the German economy to build on solid foundations, with a balance between effective state regulation and the maintenance of a free and competitive market. This combination was essential to Germany's rapid recovery and sustained growth in the post-war period, making the country a model of economic success.

Germany's post-war economic approach was characterised by the protection of economic freedom while avoiding a direct takeover of the economic process by the state. This strategy represented a subtle balance between regulation and freedom, embodying the principles of ordo-liberalism. In this model, the state did not position itself as a direct player in the economy, i.e. it did not intervene in the production or distribution of goods in any significant way. Instead, its role was to create and maintain a regulatory framework that ensured the proper functioning of the market economy. The aim was to preserve the free market dynamic, while ensuring that this freedom did not drift into abuses or monopolies that could harm the overall economy and society. The State was therefore involved in key areas to support the economy, such as guaranteeing monetary stability, implementing anti-trust legislation to safeguard competition, enforcing contracts, and investing in education and research. These interventions were designed to support and strengthen the market economy, rather than replace it with state control. This model of a committed but non-intrusive state in the economy made it possible to reconcile economic freedom with effective regulation and responsible social policy. It has contributed to the creation of a robust and dynamic economy in Germany, capable of competing internationally while ensuring a degree of social justice and economic stability.

Policies to encourage investment and consumption[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The post-war period in Germany was also marked by a process of coming to terms with the legacy of Nazism, a crucial aspect of the country's economic and social reconstruction. An important part of this legacy was the economic and monetary collapse that Germany had suffered before and during the Nazi period, a situation that had contributed to Hitler's rise to power. In the years leading up to Hitler's rise to power, Germany experienced severe economic and monetary instability, exacerbated by the war reparations imposed after the First World War and the global economic crisis of the 1930s. Hyperinflation, particularly in the early 1920s, had eroded the value of the German currency and severely affected the German economy and society. This economic instability created fertile ground for social and political discontent, which Hitler and the Nazi party capitalised on to win voter support. The resulting economic collapse and social distress were key factors in the rise of Nazism. Hitler promised a restoration of pride and economic stability, promises that resonated with many Germans suffering from the economic crisis. In the post-war period, Germany's economic reconstruction had to take account of these historical lessons. The currency reform of 1948, which introduced the Deutsche Mark, was a crucial step in overcoming the legacy of currency instability. This reform, along with the ordo-liberal economic policies adopted, aimed to restore economic stability and prevent a return to the conditions that had contributed to the rise of Nazism. By establishing a stable and prosperous economy, post-war Germany sought to turn the page on the economic mistakes of the past and build a more secure and just future for its citizens.

At the end of the Second World War, Germany was faced with major economic difficulties, including a dramatically devalued currency, the Reichsmark. To meet these challenges and restore economic stability, a significant monetary reform was introduced in 1948, marking the introduction of the Deutsche Mark (DM) to replace the Reichsmark. This monetary reform involved a major revaluation of the currency. Under this revaluation, ten Reichsmarks were exchanged for one Deutsche Mark. This decision had several important economic and political implications. On the one hand, the reform favoured employees and investment. By reducing the amount of money in circulation and stabilising the value of the new currency, the reform helped to control inflation, a major problem in post-war Germany. This created a more favourable environment for investment and contributed to a healthier economic recovery. For employees, the stabilisation of the currency meant that their incomes were less likely to be eroded by inflation, thus preserving their purchasing power. On the other hand, this reform had an unfavourable impact on savings. Savers who held Reichsmarks saw the value of their savings fall considerably following the exchange at a rate of 10 to 1. This represented a substantial loss for those who had accumulated savings in Reichsmarks. In addition, monetary reform indirectly encouraged consumption. With a stable currency and a reduced incentive to save, people were more inclined to spend their money, thereby stimulating economic activity and domestic demand. The 1948 monetary reform in Germany was a crucial political arbitrage that laid the foundations for economic stabilisation and recovery. Although it had negative consequences for savers, it was essential in turning around the German economy, encouraging investment, supporting wages and stimulating consumption, thereby making a significant contribution to the post-war German 'economic miracle'.

Consistent investment strategies[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Germany's post-war economic policy was strongly focused on investment promotion, a strategy that played a crucial role in the country's economic recovery and growth. This policy was based on a combination of fiscal and budgetary measures aimed at creating a business-friendly environment and stimulating economic activity. A central aspect of this approach was the maintenance of a relatively low rate of corporation tax. The aim of this policy was to allow companies to retain a greater proportion of their profits, thereby encouraging reinvestment in areas such as expansion, research and development, and infrastructure improvements. By increasing the ability of companies to reinvest their profits, the government has encouraged growth and innovation in the private sector. At the same time, the government has worked to keep social charges low. This has reduced the overall cost of employment for companies, making it more attractive to hire new staff. This reduction in charges has had a dual beneficial effect: it has helped to reduce the unemployment rate and stimulated consumption by increasing workers' purchasing power. Germany has also adopted a policy of budgetary orthodoxy, characterised by prudent and balanced management of public finances. By avoiding excessive budget deficits and limiting borrowing, the government has helped to keep inflation low. This monetary stability was essential to ensure a stable economic environment conducive to investment. Low inflation guaranteed the value of corporate profits and predictability for investors, key elements in fostering healthy economic growth. The combination of these policies created a framework conducive to investment and economic growth in Germany. By fostering a stable and attractive economic environment for business, Germany was able to rebuild rapidly after the war and lay the foundations for a strong and dynamic economy for decades to come.

Germany's post-war economic policy not only helped to create a favourable environment for local businesses, but also strengthened their competitiveness on international markets. Between 1950 and 1970, this strategy bore fruit, as demonstrated by the impressive annual growth in investment, which reached 9.5%. This substantial increase in investment reflects the effectiveness of the measures adopted to stimulate the economy. The combination of favourable taxation, moderate social charges and a stable fiscal policy has made German companies particularly competitive. These conditions have enabled companies to effectively reinvest their profits in key areas such as research and development, equipment modernisation and production capacity expansion. As a result, German companies have been able to improve their productivity, innovate and expand their presence on international markets. During this period, the German economy not only grew rapidly, it also improved continuously. The focus on innovation and efficiency has led to technological advances and an increase in the quality of products and services, further strengthening Germany's position as a major economic power. In addition, this impressive economic growth and Germany's political and monetary stability have attracted foreign capital. International investors, attracted by the strength of the German economy and its growth potential, contributed to an influx of capital, which further stimulated the economy. The period from 1950 to 1970 witnessed a booming German economy, stimulated by sound economic policies and a focus on innovation and competitiveness. This success not only benefited local businesses, but also enhanced Germany's attractiveness as a destination for international investment.

Salary Restraint Policy[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Wage moderation was a key element of Germany's economic policy during the Thirty Glorious Years. This approach involved slower wage growth than in other developed countries, a strategy that had a number of important implications for the German economy. Inflation control played a central role in this strategy of wage moderation. By keeping inflation low, the cost of living has remained stable, making long-term investments more secure and predictable. This stability was crucial to investor confidence and economic planning.

A notable aspect of this period was the social consensus between business and labour in Germany. The unions, aware that they were participating in a virtuous circle of economic growth and stability, often moderated their wage demands. This cooperation contributed to a stable working environment and sustained economic growth, without the frequent disruption caused by industrial disputes. The situation of full employment in West Germany was also an influential factor. The abundance of labour, partly due to the influx of German refugees - around 10 million - who settled in West Germany after the war, created a labour market where unemployment was virtually non-existent. These refugees, often willing to accept less demanding and less well-paid jobs, formed an abundant and inexpensive workforce for the rebuilding economy.

As West Germans rose up the social ladder, foreign labour was called upon to replace German workers in less skilled jobs. This period of the "Trente Glorieuses" coincided with major migratory flows, with foreign workers coming to Germany to meet the growing demand for labour. This helped to maintain a differentiated wage structure and sustain economic growth. Wage moderation, combined with an abundant workforce and social consensus, played an important role in Germany's economic success during the Trente Glorieuses. These factors helped to create a stable economic environment conducive to investment, growth and innovation.

Free trade and European integration[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Remarkable expansion of German trade[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

During the Trente Glorieuses period, Germany underwent a major transformation in its trade, characterised by impressive expansion on international markets and a strong sense of economic patriotism within its domestic market. The spectacular expansion of German foreign trade was one of the pillars of its economic success. Germany has established itself as a leading exporting power, thanks to the exceptional quality and innovation of its products. The automotive, machinery and chemicals sectors, among others, have enjoyed particular success on international markets. This export orientation has been supported by a favourable economic policy, which has not only stimulated the country's economic growth, but has also strengthened its position in the global economy. In parallel with this international expansion, the German domestic market has shown a strong tendency towards economic patriotism. German consumers have shown a marked preference for local products and services, which has greatly benefited domestic companies. This support from local consumers has enabled German companies to strengthen and grow solidly in the domestic market, providing a stable base for their export activities. This preference for domestic products has also played an important role in creating and maintaining jobs in Germany, contributing to the overall robustness of the economy. By combining a strong presence in international markets with solid domestic support, Germany has succeeded in building a dynamic and resilient economy. This two-pronged strategy was crucial to Germany's economic success during this period, affirming its status as a major economic power in Europe and beyond.

Between 1950 and 1970, the German economy experienced significant growth in foreign trade, which had a major impact on the structure of its economy. The share of exports in Germany's Gross National Product (GNP) more than doubled from 8.5% to 21%, a clear indicator of the increasingly outward-looking orientation of the German economy. At the same time, Germany's share of world exports rose remarkably, increasing by eight points to 11%. These figures testify not only to the success of German economic policies, but also to the growing competitiveness of German products and services on the world market. The spectacular increase in trade between Germany and France also illustrates this dynamism. Exports between the two countries have increased 25-fold over this period, underlining the growing economic integration within Europe. This expansion was not limited to bilateral relations with France, but also included other European countries, indicating greater economic collaboration and integration within the continent. This period saw Germany not only rebuild after the devastation of the Second World War, but also establish itself as a central economic power in Europe. Germany's commercial success with its European partners was a key factor in this development. It contributed to the creation of a more integrated single European market and laid the foundations for subsequent European economic cooperation, including the formation of the European Economic Community, the forerunner of today's European Union. The period from 1950 to 1970 witnessed a remarkable transformation of the German economy, characterised by an impressive expansion of its foreign trade and increasing integration with European economies. These developments played a crucial role in establishing Germany as an economic leader in Europe.

Strengthening trade within the EEC[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The intensification of trade within the European Economic Community (EEC) in the post-war period marks a major turning point in European economic history, in marked contrast to the mercantilist theories and practices of the 16th century. Mercantilism, which prevailed in Europe from the 16th century onwards, was an economic theory associated with the era of absolute monarchy. This economic doctrine was based on the idea that the wealth and power of a state were intrinsically linked to the accumulation of material wealth, particularly precious metals such as gold and silver. From this perspective, international trade was seen as a zero-sum game in which exports had to be maximised and imports minimised. Mercantilism therefore favoured protectionist policies, state monopolies and strict regulation of foreign trade.

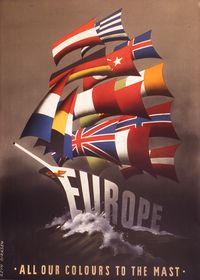

Under mercantilism, population was often seen as a means of achieving national greatness. Mercantilist policies aimed to enrich the royal treasury and strengthen the state, often to the detriment of economic freedoms and the well-being of the people. This approach was closely linked to the notion of the greatness of the king and the state, where the accumulation of wealth was a key indicator of power and prestige. In contrast, the intensification of trade within the EEC in the post-war years reflects a move towards greater economic integration and cooperation between European nations. This development marks a move away from mercantilist principles towards principles of free trade and economic interdependence. The EEC encouraged the abolition of trade barriers between Member States, fostering a common market where goods, services, capital and labour could move more freely. This economic integration was a key driver of growth and stability in Europe, contributing to the collective prosperity of the member nations and the emergence of a common European identity.

Mercantilists played a central role in the theorisation and implementation of colonisation and the colonial pact, reflecting the fundamental principles of mercantilism. This economic approach, which prevailed from the 16th to the 18th century, had a profound influence on the way in which European nations approached colonial expansion. The colonial pact, a typically mercantilist concept, was based on the idea that the colonies should trade exclusively with the metropolis. This system aimed to maximise the metropolis' profits by limiting the colonies' commercial interactions with other nations. The colonies were seen primarily as sources of raw materials and markets for the metropolis' finished products, creating an economic dependence that benefited the colonising power. This dynamic was perfectly in line with the mercantilist doctrine, which sought to increase national wealth by promoting a positive balance of trade. There are also ideological links between mercantilism and fascist thought, particularly in the way the nation is conceptualised and glorified. Fascism, which emerged in the twentieth century, shared with mercantilism a certain vision of national greatness and central authority. In both cases, the state was seen as the central pillar of society, with a strong emphasis on nationalism and state control. Fascism, like mercantilism, glorified the nation as the supreme place of sacrifice and greatness, and often favoured protectionist and interventionist economic policies. However, it is important to note that, although they shared certain ideological principles, mercantilism and fascism were distinct in their historical context and specific applications. Mercantilism was primarily an economic theory, while fascism was a totalitarian political movement with a broader and more ideological vision of society and the state.

At the same time as mercantilism was predominating in Europe, a new current of economic thought began to emerge: physiocratism. This movement, which originated in France in the 18th century, opposed many of the fundamental principles of mercantilism and laid the foundations for economic liberalism, including English liberalism. The physiocrats also influenced the thinking of the leaders of the American War of Independence. The Physiocrats believed that a nation's wealth derived from the value of its agricultural production and was therefore intrinsically linked to the land. They criticised mercantilist policies, in particular their emphasis on the accumulation of precious metals and their protectionist approach to trade. Instead, the physiocrats advocated an economy based on the natural laws of supply and demand, and supported the idea of laissez-faire economics, where state intervention in the economy should be minimised. In addition to their contributions to economic theory, the physiocrats also had important thoughts on peace and war. They believed that war was not a natural state of humanity and that peace had to be established through fair agreements. This view of peace as preferable to war influenced their approach to international trade. The physiocrats saw international trade as a way out of autarky and a means of promoting the mutual interests of nations. They saw trade as a factor for peace, arguing that trade between nations created beneficial interdependencies that could help prevent conflict. This perspective marked an important break with mercantilism and influenced the subsequent development of economic liberalism and theories of international trade. In this way, the physiocrats played a crucial role in the evolution of economic thought, promoting ideas that encouraged the development of free trade and laying the theoretical foundations for more peaceful international relations based on economic cooperation.

The end of the Second World War marked a decisive turning point in economic policies and international relations, particularly in Europe. Faced with the need to rebuild devastated nations and prevent future conflict, leaders and economists adopted a proactive, pro-active approach to economic cooperation. This strategy was in line with the principles of cooperation and free trade promoted by liberal economic theories, and a far cry from the mercantilist and protectionist policies of the past. An emblematic example of this new approach is the increase in trade between France and Germany in the post-war period. These two countries, historically rivals and deeply marked by conflict, chose to transform their relationship through increased economic cooperation. This decision was a key element in the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), which later evolved into the European Union. The establishment of Franco-German exchanges was a strategic choice to strengthen economic and political ties, in the hope of creating an interdependence that would guarantee peace and stability. The emphasis on economic integration and trade between these two nations has served as a model for other regional cooperation initiatives in Europe. This focus on free trade and economic cooperation was also supported by the implementation of the Marshall Plan, which provided substantial financial assistance for the reconstruction of Europe. The Marshall Plan not only helped to rebuild devastated economies and infrastructure, but also encouraged recipient countries to work together for a common economic recovery. The post-war period saw a marked shift in economic policies in Europe, from isolationism and protectionism to economic openness and cooperation. This transformation was fundamental to the reconstruction of countries devastated by war, and laid the foundations for European integration and long-term peace on the continent.

Focus on Industrial Specialisation[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The notion of industrial specialisation in post-war Germany is closely linked to an idea put forward by the economist Alexander Gerschenkron. Gerschenkron challenged the idea that Germany lagged behind other industrialised nations in terms of industrial development. Instead, he argued that, as a result of the massive destruction suffered during the Second World War, Germany had a unique opportunity to 'start afresh' and rebuild its industry. This perspective paved the way for an approach based on industrial specialisation. Rather than simply restoring pre-war industrial structures and capabilities, Germany was able to reassess and reorientate its industrial sector. This reorientation involved the adoption of new and more advanced technologies, innovation in production processes, and a concentration on industrial sectors in which Germany could become or remain a world leader.

The reconstruction process also enabled Germany to modernise its industrial infrastructure. By building new factories and adopting efficient production methods, German industry became more competitive on the world market. This modernisation led to rapid economic growth and helped establish Germany as a major economic power. In addition, this strategy of industrial specialisation has been underpinned by government policies favouring investment in research and development, as well as strong support for education and vocational training. These policies have strengthened Germany's ability to innovate and excel in key industrial areas.

Gerschenkron's vision steered Germany's post-war industrial reconstruction towards a strategy focused on the future and innovation. This approach not only enabled Germany to recover from the devastation of war, but also laid the foundations for its future economic success, focusing on the development of state-of-the-art economic infrastructures and a specific industrial strategy. A central aspect of this strategy has been a focus on the production of high value-added goods, particularly in the industrial and domestic equipment sectors. This focus on high-quality products has enabled German industry to distinguish itself on the world market. A key element in this differentiation has been the establishment of the "German quality" label. This label means not only that the products are solid and durable, but also that they are accompanied by an efficient and reliable after-sales service. This marketing and branding strategy has helped to establish an international reputation for German products, associating 'Made in Germany' with quality and reliability. The German automotive industry is a particularly striking example of this specialisation. Focusing on the production of high-quality vehicles, the German automotive industry has become synonymous with high value-added products. These vehicles, which are often more expensive, enjoy a reputation for high quality, justifying their price by superior longevity and performance.

This strategy has required a highly skilled workforce capable of producing complex, high-tech goods. As a result, Germany invested heavily in vocational training, ensuring that its workers had the skills needed to support this industrial strategy. These investments in education and vocational training were crucial to the development of a skilled workforce, capable of meeting the demands of modern industrial production. Germany's post-war industrial strategy, with its focus on high value-added, high-quality products, combined with investment in vocational training, has been a key factor in the country's economic transformation. This approach has not only strengthened the competitiveness of German industry on world markets, but has also helped to build a solid and sustainable economy.

Limited but Innovative Social Policy[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The post-war reconstruction period in Germany was marked by major economic and social reforms. One notable aspect of these reforms was the privatisation of companies nationalised by the Nazi regime. This was part of a wider movement to promote "people's capitalism" in the country. The promotion of popular capitalism in Germany involved broadening share ownership to include ordinary citizens, thereby encouraging greater popular participation in the economy. This strategy aimed to democratise economic ownership and spread the benefits of economic growth throughout society. By allowing more people to invest in companies and benefit from market gains, the state sought to build consensus around a more inclusive and socially responsible model of capitalism. In addition, the German state took steps to compensate savers affected by the currency revaluation of 1948. This revaluation resulted in a significant loss for those who had saved in Reichsmarks, particularly the elderly. To mitigate the impact of this loss and to maintain confidence in the economic system, the government introduced compensation for savers, demonstrating its desire to protect citizens from the negative consequences of the necessary economic reforms. To complement these measures, Germany developed an original welfare state system. This system combined elements of social protection with a commitment to the market economy. It included various forms of social insurance, pensions, healthcare and other social support measures. This welfare state model sought to balance economic growth with social justice, guaranteeing a safety net for citizens while promoting innovation and economic efficiency. These policies were essential in shaping post-war Germany, creating a strong and resilient economy that was at the same time socially responsible. The German model demonstrated that it was possible to combine economic success with social progress, a balance that contributed to the country's stability and prosperity in the decades that followed.

The 'German consensus' in the post-war period represents a unique model of industrial relations, characterised by the search for a balance between co-determination (Mitbestimmung) and the regulation of the right to strike. This model played a crucial role in Germany's economic and social stability during this period. A central element of this consensus was the introduction of the right of co-determination in companies. Under this principle, union representatives were given seats on company boards, enabling them to play an active part in decision-making. This gave employees a direct voice in the running of the company, a significant departure from traditional industrial relations models. In addition, the fact that union representatives were provided with balance sheets gave them access to essential information, enabling them to tailor their negotiations in an informed manner and to bargain more effectively. However, this right to co-determination was accompanied by compromises, particularly with regard to the right to strike. For a strike to be declared, 75% of the workers had to agree in a secret ballot. This requirement represented a significant restriction on the right to strike, according to some critics. By requiring this level of consensus among workers to call a strike, the German model sought to maintain stability and avoid disruption to the economy and production. For some, this approach represented a severe restriction on the right to strike, but for others it was seen as a means of ensuring constructive dialogue between employers and employees and preventing destabilising industrial disputes. The German consensus, by combining co-determination with regulation of the right to strike, helped to create a collaborative and stable working environment, promoting both economic efficiency and workers' rights. This model of industrial relations was an important component of Germany's economic success in the decades following the Second World War, illustrating how a balanced approach can lead to shared prosperity and social stability.

Switzerland: A Model Close to Germany[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Switzerland, like Germany, exhibited a number of similar economic characteristics in the post-war period, particularly with regard to labour. A key element of the Swiss economic strategy was the abundance of labour, partly due to international agreements, notably with Italy. The agreement with Italy, signed against the backdrop of a booming economy, has enabled Switzerland to attract a large Italian workforce. Italian workers, attracted by the employment opportunities in Switzerland, have played a key role in various sectors of the Swiss economy, particularly in areas such as construction, industry and services. This immigration of workers helped to meet Switzerland's labour needs, a country that was experiencing an economic boom but had a relatively small labour market. The influx of Italian labour not only helped to fill Switzerland's labour shortage, but also contributed to the country's cultural and economic diversity. Immigrant workers have brought new skills and perspectives, contributing to the Swiss economy in a variety of ways. At the same time, as in Germany, Switzerland has focused on training and skills development. Vocational training and education have been key components of Switzerland's economic strategy, ensuring that both local workers and immigrants have the necessary skills to contribute effectively to the economy. Switzerland's approach to labour and immigration, combined with a commitment to training and skills development, has been an important factor in its economic success. It has enabled Switzerland to maintain a highly skilled and adaptable workforce capable of meeting the needs of a constantly evolving economy.

Despite some outdated infrastructure, Switzerland has been able to compensate for these weaknesses and take advantage of a number of key economic assets, including an immigrant workforce and a strong currency. Immigration, particularly of workers willing to accept relatively low wages, has played an important role in the Swiss economy. These immigrant workers have provided essential labour in sectors where the infrastructure may be less modern or in need of renovation. Although this situation has presented challenges, the supply of cheap labour has enabled Switzerland to maintain its competitiveness in certain sectors. Another key factor for the Swiss economy was the strength of the Swiss franc. Combined with low inflation, the Swiss franc has become a safe haven on international markets. This reputation has encouraged investment in Switzerland, from both domestic and international investors, attracted by the stability and reliability of the Swiss economy. These investments have been crucial to the country's economic development, enabling it to modernise its infrastructure and support innovation.

The "Swiss Quality" label is another pillar of the country's economic success. This label is the result of specialisation in the production of products with high added value. Switzerland has distinguished itself in sectors such as watchmaking, pharmaceuticals, technology and finance, where quality, precision and innovation are paramount. This specialisation has reinforced Switzerland's international reputation for quality and excellence, a significant commercial asset. The Swiss economy has been able to leverage its unique strengths - a diverse workforce, a strong currency and a specialisation in high-quality products - to overcome its infrastructural challenges and maintain a strong position on the global economic stage. These factors have combined to make Switzerland a prosperous and respected economic centre.

Social consensus in Switzerland has played a fundamental role in the country's stability and economic development. This approach has helped to maintain a peaceful working climate and has helped to minimise social tensions, particularly in the world of work. One of the key elements of this social consensus in Switzerland has been the concept of "labour peace". This principle is based on the idea that labour disputes should be resolved through dialogue and negotiation, rather than through strikes or confrontation. Social policy in Switzerland, although considered moderate, has played a role in promoting this consensus. In 1937, an important milestone was reached with the signing of the first "labour peace" agreement by the Metal and Mechanical Engineering Federation. This agreement aimed to avoid conflicts in the workplace by adhering to the rule of good faith and favouring negotiation and arbitration to resolve disputes. This agreement marked the beginning of a prolonged period of industrial stability in Switzerland, which lasted until the 1980s. Discipline in behaviour and demands, as well as organisation and order in the management of labour relations, played an essential role in the pacification of social tensions in Switzerland. By appointing arbitrators with binding powers to settle disputes, Switzerland has succeeded in maintaining a harmonious working environment. In addition to these conflict resolution mechanisms, Switzerland has also set up social protection systems. In 1948, Old Age and Survivors' Insurance (AVS) was introduced, providing basic cover for retirement and the risks associated with age. Later, in 1976, full unemployment insurance was introduced, offering additional protection to workers in the event of job loss. These social protection measures, combined with a consensus-based approach to industrial relations, have contributed to Switzerland's stability and prosperity. They have helped to create a balance between economic needs and worker protection, contributing to a balanced social climate conducive to economic development.

Post-war geopolitical restructuring[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Before 1945, there was a coherence between economic and political hegemonies in the world. During this period, the United Kingdom was seen as the dominant power internationally, not only because of its extensive colonial empire, but also because of its leading position in the industrial revolution and world trade. At the same time, the United States was becoming a rising power, both economically and politically. In Europe, France and Germany were engaged in an intense rivalry, which culminated in the First World War. This rivalry was both economic, with competition for resources and markets, and political, linked to national ambitions and territorial tensions.