Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

The 18th century marked the advent of a revolutionary era in the course of human history, indelibly shaping the future of Europe and, by extension, the world. Anchored between ancient traditions and modern visions, this century was a crossroads of contrasts and contradictions. At the beginning of the century, Europe was still largely a mosaic of agrarian societies, governed by ancestral feudal structures and a hereditary nobility holding power and privileges. Daily life was punctuated by agricultural cycles and the vast majority of the population lived in small rural communities, dependent on the land for their livelihood. However, the seeds of change were already present beneath the surface, ready to blossom.

As the century progressed, a wind of change blew across the continent. The influence of the Enlightenment philosophers, who advocated reason, individual freedom and scepticism towards traditional authority, began to challenge the established order. Literary salons, cafés and newspapers became forums for progressive ideas, fuelling the desire for social, economic and political reform. Europe's economic dynamic was also undergoing a radical transformation. The introduction of new farming methods and crop rotation improved land yields, encouraging population growth and increasing social mobility. International trade intensified thanks to advances in navigation and colonial expansion, and cities such as Amsterdam, London and Paris became buzzing centres of commerce and finance. The Industrial Revolution, although in its infancy, was beginning to show its face by the end of the 18th century. Technological innovations, particularly in textiles, transformed production methods and shifted the focus of the economy from rural areas to the expanding urban cities. Water power and later the steam engine revolutionised industry and transport, paving the way for mass production and a more industrialised society.

Yet this period of growth and expansion also witnessed growing inequality. Mechanisation often led to unemployment among manual workers, and living conditions in industrialising cities were frequently miserable. The wealth generated by international trade and the colonisation of the Americas was not evenly distributed, and the benefits of progress were often tempered by exploitation and injustice. Political upheavals, such as the French Revolution and the American War of Independence, demonstrated the potential and desire for representative government, undermining the foundations of absolute monarchy and laying the foundations for modern republics. The notion of the nation state began to emerge, redefining identity and sovereignty. The end of the 18th century was therefore a period of dramatic transition, as the old world gradually gave way to new structures and ideologies. The imprint of these transformations shaped European societies and established the premises of the contemporary world, inaugurating debates that continue to resonate in our society today.

Notions of structure and economic conditions

In the jargon of the economic and social sciences, the term 'structure' refers to the enduring features and institutions that make up and define the way an economy functions. These structural elements include laws, regulations, social norms, infrastructures, financial and political institutions, as well as patterns of ownership and resource allocation. Structural elements are considered stable because they are woven into the fabric of society and the economy and do not change quickly or easily. They serve as the foundation for economic activities and are crucial to understanding how and why an economy works the way it does.

The concept of equilibrium in economics, often associated with the economist Léon Walras, is a theoretical state in which resources are allocated in the most efficient way possible, i.e. supply meets demand at a price that satisfies both producers and consumers. In such a system, no economic actor has the incentive to change his or her production, consumption or exchange strategy, because the existing conditions maximise utility for all within the given constraints. In reality, however, economies are rarely, if ever, in a state of perfect equilibrium. Structural changes, such as those observed during the eighteenth century with the transition to more industrialised and capitalist economic systems, involve a dynamic process in which economic structures evolve and adapt. This process can be disrupted by technological innovations, scientific discoveries, conflicts, government policies, social movements or economic crises, all of which can lead to imbalances and require structural adjustments. Economists study these structural changes to understand how economies develop and respond to various disturbances, and to inform policies that aim to promote stability, growth, and economic well-being.

In the context of capitalism, structure can be thought of as the set of regulatory frameworks, institutions, business networks, markets and cultural practices that shape and sustain economic activity. This structure is essential for the proper functioning of capitalism, which is based on the principles of private ownership, capital accumulation and competitive markets for the distribution of goods and services. The structural integrity of a capitalist system, i.e. the robustness and resilience of its components and institutions, is crucial to its stability and ability to regulate itself. In such a system, each element - be it a financial institution, a company, a consumer or a government policy - must function efficiently and autonomously, while being consistent with the system as a whole. Capitalism is theoretically designed to be a self-regulating system where the interaction of market forces - principally supply and demand - leads to economic equilibrium. For example, if demand for a product increases, the price tends to rise, which means a greater incentive for producers to produce more of that product, which should eventually restore the balance between supply and demand. However, economic history shows that markets and capitalist systems are not always self-correcting and can sometimes be subject to persistent imbalances, such as speculative bubbles, financial crises or growing inequality. In these cases, elements of the system may not adapt effectively or quickly, leading to instability that may require external intervention, such as government regulation or monetary and fiscal policies, to restore stability. So, although capitalism tends towards some form of equilibrium thanks to the flexibility and adaptability of its structures, the reality of how it works can be much more complex and often requires careful management and regulation to avoid dysfunction.

The Ancien Régime structure

The economy of the Ancien Régime, which prevailed in Europe until the end of the 18th century and is particularly associated with pre-revolutionary France, was mainly dominated by agriculture. This agrarian predominance was strongly marked by cereal monoculture, with wheat as the standard of production. This specialisation reflected the basic food needs of the time, climatic and environmental conditions, and farming practices rooted in tradition. Land was the main source of wealth and the symbol of social status, resulting in a rigid socio-economic structure that was reluctant to change and adopt new farming methods. The productivity of Ancien Régime agriculture was low. Land yields were limited by the use of traditional farming techniques and a glaring lack of innovation. Three-year crop rotation and dependence on the vagaries of nature, in the absence of advanced technology, limited agricultural efficiency. Investment in technologies that could improve the situation was rare, hampered by a combination of lack of knowledge, lack of capital, and a social system that did not value agricultural entrepreneurship.

In terms of demographics, population balance was maintained by social customs such as late marriage and a high rate of permanent celibacy, practices that were particularly widespread in north-western Europe. These customs, combined with high infant mortality and recurring periods of famine or pandemic, naturally regulated population growth despite meagre agricultural production.

The development of means of transport and communication was also very limited, resulting in an economy characterised by the existence of micro-markets. High transport costs made it prohibitively expensive to trade goods over long distances, with the exception of high-value-added products such as watches produced in Geneva. These luxury items, aimed at a wealthy clientele, could absorb the transport costs without compromising their competitiveness on distant markets.

Finally, industrial and craft production under the Ancien Régime was mainly focused on the manufacture of everyday consumer goods, dictated by the "law of consumer urgency", i.e. the necessities of eating, drinking and dressing. Industries, particularly textiles, were often small-scale, spread across the country and tightly controlled by guilds that restricted competition and innovation. This limited production was consistent with the immediate needs and economic capacities of the majority of the population at the time.

This set of characteristics defined an economy and society where the status quo prevailed, leaving little room for innovation and dynamic change. The rigidity of the structures of the Ancien Régime therefore played a part in delaying the entry of countries like France into the Industrial Revolution, compared with England, where social and economic reforms paved the way for more rapid modernisation.

The Economic Situation: Analysis and Impact

Economic and social history is marked by long-term cycles of growth and recession, crises and periods of recovery. Changing socio-economic structures is an arduous process, not least because it involves upsetting the balance of systems that have been in place for centuries. However, these structures are not set in stone and reflect the constant dynamics of a society that is constantly evolving, even if the ways in which this evolution occurs can be subtle and complex to discern.

Crises are often the result of an accumulation of tensions within a system that has enjoyed a long period of apparent stability. These tensions can be exacerbated by catastrophic events that force a reorganisation of the existing system. Crises can also lead to greater social polarisation, with more distinct winners and losers as society adapts and reacts to change.

The image of "rising and falling, like successive tides" is a powerful metaphor for these economic and social cycles. There are periods of demographic or economic growth that seem to be reversed or cancelled out by periods of crisis or depression. These 'ebbs and flows' are characteristic of human history, and studying them offers valuable insights into the forces that shape societies over time. It also suggests an inherent resilience in social systems, which although facing regular 'breakdowns', are able to recover and rise again, although never quite in the same way as before. Each cycle brings with it changes, adaptations and sometimes profound transformations of existing structures.

The Dawn of Economic Growth

The 18th century was marked by a demographic expansion unprecedented in European history. The population of the United Kingdom, for example, grew impressively, from around 5.5 million at the beginning of the century to 9 million at the dawn of the 19th century, an increase of almost 64%. This demographic growth was one of the most remarkable of the period, reflecting improved living conditions and technological and agricultural progress. France was no exception, with its population rising from 22 to 29 million, an increase of 32%. This rate of growth, while less spectacular than that of the UK, nonetheless reflects a significant change in French demographics, benefiting also from improvements in agriculture and relative political stability. On the European continent as a whole, the overall population grew by around 58%, a remarkable figure given that Europe had been subject to recurring demographic crises in previous centuries. Unlike previous periods, this growth was not followed by major demographic crises, such as famines or large-scale epidemics, which could have significantly reduced the number of inhabitants.

These demographic changes are all the more remarkable in that they have occurred without the traditional mortality "corrections" that have historically accompanied population increases. There are many reasons for this phenomenon: improved agricultural production thanks to the Agricultural Revolution, advances in public health, and the start of the Industrial Revolution, which created new jobs and encouraged urbanisation. These population increases played a crucial role in the economic development and social transformations of the period, providing an abundant workforce for fledgling industries and stimulating demand for manufactured goods, thus laying the foundations of modern European societies.

The exceptional demographic growth of 18th-century Europe can be attributed to a number of interdependent factors that together altered the continent's socio-economic landscape. Agricultural innovation was a key driver of this growth. The introduction of crops from different continents diversified and enriched the European diet. Maize and rice, imported from Latin America and Asia respectively, transformed agriculture in southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy, which adapted to intensive rice cultivation. In northern and western Europe, the potato played a similar role. Its rapid spread over the course of the century increased calorie intake compared with traditional cereals, and it became the staple food of the working classes. Trade also made a significant contribution to prosperity and population growth, especially in the British Isles. The United Kingdom, in particular, built up a robust merchant fleet, establishing itself as the "world's trader". The development of the Industrial Revolution enabled the mass production of goods that were then distributed across the continent. In 1740, when a bad harvest hit Western Europe, England was able to avoid a mortality crisis by importing wheat from Eastern Europe thanks to its fleet, while France, less well connected by sea, suffered the consequences of this shortage. The Netherlands also enjoyed considerable commercial power thanks to its merchant navy. Finally, the change in economic structures had a profound impact. The transition from the domestic system, where production took place in the home, to proto-industrialisation created new economic dynamics. Proto-industrialisation, which involved an increase in small-scale, often rural production prior to full industrialisation, laid the foundations for an industrial revolution that would transform local economies into economies of scale, amplifying the capacity to produce and distribute goods. These factors, combined with advances in public health and better management of food resources, not only enabled Europe's population to grow substantially, but also paved the way for a future in which industrialisation and world trade would become the pillars of the global economy.

The Domestic System or Verlagsystem: Foundations and Mechanisms

The Verlagsystem was a key precursor to industrialisation in Europe. Characteristic of certain regions of Germany and other parts of Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries, this system marked an intermediate stage between artisanal work and the industrial factory production that would later predominate. In this system, the Verleger, often a wealthy entrepreneur or merchant, played a central role. He distributed the necessary raw materials to the workers - generally craftsmen or peasants looking to supplement their income. These workers, using the space of their own homes or small local workshops, concentrated on producing goods to the specifications provided by the Verleger. They were paid on a piecework basis, rather than a fixed wage, which encouraged them to be as productive as possible. Once the goods had been produced, the Verleger collected them, took care of the finishing if necessary, and sold them on the local market or for export. The Verlagsystem facilitated the expansion of trade and allowed greater specialisation of work. It was particularly dominant in the textile industries, where items such as garments, fabrics and ribbons were mass-produced.

This system had several advantages at the time: it offered considerable flexibility in terms of labour, allowing workers to adapt to seasonal demand and market fluctuations. It also allowed entrepreneurs to minimise fixed costs, such as those associated with maintaining a large factory, and to bypass some of the restrictions of the guilds, which strictly controlled production and trade in the towns. However, the Verlagsystem was not without its flaws. Workers, tied to the piece, could find themselves in a situation of virtual dependence on the Verleger, and were vulnerable to economic pressures such as falling prices for finished goods or rising costs for raw materials. With the advent of the industrial revolution and the development of factory production, the Verlagsystem gradually declined, as new machines enabled faster, more efficient production on a larger scale. Nevertheless, it was a crucial step in Europe's transition to an industrial economy and laid the foundations for some modern production principles.

The domestic system was particularly prevalent in the textile industry in Europe from the 16th century onwards. It was a method of organising work that preceded industrialisation and involved dispersed production in the home rather than centralised production in a factory or workshop. Under this system, raw materials were supplied to homeworkers, who were often farmers or family members looking to earn extra income. These workers used simple tools to spin wool or cotton, and to weave cloth or other textile goods. The process was usually coordinated by entrepreneurs or merchants who supplied the raw materials and, after production, collected the finished goods to sell on the market. This method of working had advantages for both merchants and workers. Merchants could bypass the restrictions of the urban guilds, which strictly regulated trade and crafts in the towns. For workers, this meant they could work from home, which was particularly advantageous for rural families, who could supplement their farming income with textile production. However, the domestic system had its limits. Production was often slow and the quantities produced relatively small. What's more, the quality of the goods could vary considerably. Over time, these disadvantages became more apparent, particularly when the industrial revolution introduced more efficient machinery and factory production. The invention of machines such as the power loom and the spinning machine greatly increased productivity, leading to the obsolescence of the domestic system and the rise of factories. The domestic system was therefore a significant stage in the evolution of industrial production, serving as a bridge between traditional craftwork and the large-scale production methods that followed it. It witnessed the first stages of industrial capitalism and the emergence of a more modern market economy.

The domestic system, which was widespread before the advent of industrialisation, was characterised by its decentralised production structure and the dynamic between craftsmen and merchants. At the heart of this system were the peasants who, outside the demanding seasons of agricultural work such as sowing and harvesting, devoted their time to craft production, particularly in the textile sector. This model offered workers a way of supplementing their often insufficient income, while guaranteeing them a degree of flexibility in their employment. In return, merchants benefited from an affordable and adaptable workforce. Merchants also played a pivotal role in the economic organisation of the system. Not only did they supply craftsmen with the raw materials they needed, but they were also responsible for distributing tools and managing orders. His ability to centralise the purchase and distribution of resources enabled him to reduce transport costs and exercise control over the production and sales chain. What's more, by regulating the pace of work according to orders, the merchant adapted supply to demand, a practice that heralded the principles of flexibility in modern capitalism. Overall, the domestic system was marked by the dominant figure of the merchant-entrepreneur, who orchestrated the production and marketing of finished products, relying on intermittent farm labour. This system was to evolve gradually, paving the way for more centralised production methods and the industrial revolution that would follow.

In the domestic system that prevailed before the Industrial Revolution, the role of the peasant was characterised by a high degree of economic dependence. This depended on a number of factors. Firstly, the peasant's life was governed by the seasons and agricultural cycles, making his income uncertain and variable. As a result, craft production, particularly in the textile sector, provided a necessary income supplement to make up for the shortfall in earnings from farming. The nature of this dependence was twofold: not only did the peasant depend on agriculture for his main livelihood, but he was also dependent on the additional income provided by craft work. Secondly, the relationship between the peasant and the merchant was asymmetrical. The merchant, who controlled the distribution of raw materials and the marketing of finished products, had considerable influence over the peasant's working conditions. By supplying the tools and placing the orders, the merchant dictated the work flow and indirectly determined the peasant's level of income. This dependence was exacerbated by the fact that the peasant himself did not have the means to market his products on a significant scale, forcing him to accept the terms dictated by the merchant. The peasant's dependence on the merchant was reinforced by his precarious economic status. With little opportunity to negotiate or alter the conditions of their craft work, farmers were vulnerable to fluctuations in demand and the decisions of the merchant. This situation lasted until the advent of industrialisation, which radically transformed production methods and economic relations within society.

The textile guilds, strong institutions from the Middle Ages to the modern period, played an essential role in regulating the production and quality of goods, as well as in the economic and social protection of their members. When the decentralised production system, known as the Verlagsystem or putting-out system, began to develop, it presented an alternative model in which merchants outsourced work to craftsmen and peasants working in their own homes. This new model created significant tensions with traditional guilds for a number of reasons. Corporations were based on strict rules governing the training, production and sale of goods. They imposed high standards of quality and guaranteed a certain standard of living for their members, while limiting competition to protect local markets. The Verlagsystem, however, operated outside these regulations. Merchants were able to bypass the constraints of the guilds, offering products at lower cost and often on a much larger scale. For the guilds, this form of production represented unfair competition as it did not abide by the same rules and could threaten the economic monopoly they maintained over the production and sale of textiles. As a result, the corporations often sought to limit or prohibit the activities of the Verlagsystem in order to preserve their own practices and advantages. This opposition sometimes led to open conflict and attempts to introduce stricter regulations to curb the expansion of the system. Despite this, the Verlagsystem gained ground, particularly where corporations were less powerful or less present, foreshadowing the economic and social changes that were to characterise the Industrial Revolution.

The organisation of production that emerged with the domestic system offered an innovation in the management of agricultural labour. The system enabled peasants to take advantage of their slack periods by working part-time for merchants or manufacturers. The peasant thus became a cheap and flexible workforce for the merchant, who could adapt to fluctuations in demand without the constraints of a full-time commitment. Despite this innovation, the domestic system remained a relatively marginal phenomenon and did not have the transformative impact that capitalist merchants might have expected. The latter held the capital needed to buy the raw materials and pay the peasants for their labour, often at the lowest price, before selling the finished products on the market. This represented an early form of commercial capitalism, but this economic model came up against a major obstacle: weak demand. The social and economic reality of the time was that of a "society of mass misery", where famine was commonplace and consumption was limited to the bare necessities. Clothes, for example, were bought to last and were patched and reused rather than replaced. Mass consumption required a level of purchasing power that was simply not present in the majority of the population, with the exception of a few minority groups such as the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the clergy. So, despite its innovative aspects, the domestic system did not grow significantly, partly because of this weak demand and limited overall purchasing power. This helped to keep the economic system in a state of "gridlock", where technological and organisational progress alone could not trigger wider economic development without a concomitant increase in market demand.

The emergence of proto-industrialisation

Proto-industry, which developed mainly before the Industrial Revolution, was an intermediate stage between the traditional agricultural economy and the industrial economy. This form of economic organisation emerged in Europe, particularly in rural areas where farmers sought to supplement their income outside the planting and harvesting seasons. Under this system, production was not centralised, as it was in the factories of the later industrial era, but dispersed across numerous small workshops or homes. Craftsmen and small-scale producers, who often worked in families, specialised in the production of specific goods such as textiles, pottery or metals. These goods were then collected by merchants, who were responsible for distributing them to wider markets, often well beyond local ones.

Proto-industrialisation implied a mixed economy in which agriculture remained the main activity, but in which the production of manufactured goods played an increasing role. This period was marked by a still rudimentary division of labour and limited use of specialised machinery, but it nonetheless laid the foundations for the subsequent development of industrialisation, notably by accustoming part of the population to work outside agriculture, stimulating the development of skills in the production of goods and promoting the accumulation of capital needed to finance larger, more technologically advanced businesses.

Franklin Mendels (1972): Thesis on Flanders in the 18th Century

Franklin Mendels conceptualised the term 'proto-industrialisation' to describe the evolutionary process that took place in the European countryside, particularly in Flanders, during the 18th century, foreshadowing the Industrial Revolution. His thesis highlights the coexistence of agriculture with the small-scale production of manufactured goods in peasant households. This dual economic activity enabled rural families to increase their income and reduce their vulnerability to agricultural hazards. According to Mendels, proto-industrialisation was characterised by a scattered distribution of manufactured production, often carried out in small workshops or within households, rather than in large, concentrated factories. Farmers were often dependent on local merchants who supplied the raw materials and took care of marketing the finished products. This system stimulated productivity and promoted efficiency in the production of manufactured goods, which in turn boosted the economy of the regions concerned. This period also saw significant changes in family and social structures. Farming families adapted by adopting economic strategies that combined agriculture and manufacturing. This had the effect of familiarising the workforce with manufacturing activities and weaving distribution networks for the goods produced, thereby facilitating the accumulation of capital. Proto-industrialisation therefore not only changed the economic landscape of these regions, but also had an impact on their demography, social mobility and family relations, laying the foundations for modern industrial societies.

At the end of the 17th century, population growth in Europe led to significant changes in the social composition of the countryside. This demographic growth led to the distinction of two main groups within the rural population. On the one hand, there were the landless peasants. This group was made up of people who did not own any agricultural plots and who often depended on seasonal or day labour to survive. These people were particularly vulnerable to economic fluctuations and poor harvests. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution, they were to become an essential workforce, often described as the 'reserve army' of industrial capitalism, as they were available to work in the new factories and plants due to their lack of ties to the land. On the other hand, there were the peasants who, faced with demographic pressure and the increasing scarcity of available land, sought alternative sources of income. These peasants began to turn to non-agricultural activities, such as craft production or work at home within the framework of systems such as the domestic system or proto-industrialisation. In this way, they contributed to the economic diversification of the countryside and to preparing rural populations for the industrial transformations to come. These dynamics led to a socio-economic reorganisation of the countryside, with an impact on the traditional structures of agriculture and a growing involvement of rural areas in the wider economic circuits of trade and manufacturing production.

Characteristics of the Proto-industry ("Putting-Out System")

The eighteenth century was a period of profound economic transformation in Europe, and particularly in regions such as Flanders. The economic historian Franklin Mendels, in his landmark thesis on eighteenth-century Flanders, identified several key elements that characterised proto-industry, a system that paved the way for the Industrial Revolution. One of Mendels' most surprising findings is that, unlike earlier periods in history, population growth in the eighteenth century was mainly centred in the countryside rather than the towns. This marks a reversal of historical demographic trends in which cities were usually the engines of growth. This expansion of the rural population led to a surplus of labour available for new forms of production. Furthermore, Mendels identified that the basic economic unit during this period was neither the town nor the village, but rather the household. The household functioned as the nucleus of production and reproduction. Rather than relying solely on agriculture, rural families diversified their activities by taking part in proto-industrial production, often as part of the domestic system. These households produced goods at home, such as textiles, for merchants or entrepreneurs who supplied them with raw materials and collected the finished products for sale. This economic structure allowed greater flexibility and adaptability to fluctuations in demand and the seasons, contributing to sustained economic growth that would eventually lead to the Industrial Revolution. Protoindustry was therefore a key factor in economic growth in the 18th century, preparing rural populations for the major changes that were to come with industrialisation.

Franklin Mendels' meticulous studies of eighteenth-century Flanders offer a detailed insight into the economic and social dynamics of rural Western Europe. By analysing the archives of some 5,000 households, Mendels was able to identify three distinct social groups, whose growth reflected the tensions and changes of the time. The landless peasants were a growing group, a direct consequence of population growth that outstripped the capacity of the land to provide for everyone. With inheritance practices dividing the land between several heirs, many farms became unviable and went bankrupt. These farmers were under pressure from demographic and economic imperatives, sometimes leading to bankruptcy. For some, working for large landowners was an option, while others would become what Marx called "the reserve army of capitalism", ready to join the workforce of nascent industry in their desperate search for work. A second group was made up of peasants who chose to emigrate to avoid the excessive subdivision of their family plot of land and the consequent dilution of income. These peasants sought economic opportunities in town or even abroad, often on a seasonal basis, establishing migration patterns that became common in the eighteenth century. Finally, there were those who remained attached to their land but were forced to innovate in order to survive. This group adopted proto-industry, combining agricultural work with small-scale industrial production, often in the home. By integrating these new forms of production, they managed to maintain their rural lifestyle while generating the additional income needed to support their families. These three social groups, observed by Mendels, illustrate the complexity and diversity of the responses to the economic and demographic challenges of the time, and their central role in the transformation of pre-industrial rural society.

Proto-industry represents an intermediate phase of economic development that took place mainly in the countryside, characterised by a system of home-based work. It is a form of rural craft industry that remains largely invisible in traditional economic statistics, as it takes place in the interstices of agricultural time. The workers, often peasants, use the periods when farming requires less attention to engage in production activities such as spinning or weaving, enabling them to diversify their sources of income. The proto-industrial system is perfectly compatible with the seasonal rhythm of farming, as it capitalises on the slack periods in agriculture. In this way, farmers can continue to meet their food needs through agriculture while increasing their income through proto-industrial activities. In the event of a poor harvest and rising wheat prices, the additional income generated by the proto-industry provides economic security, enabling them to buy food. Conversely, if a crisis hits the textile sector, agricultural harvests can provide a guarantee against famine. The duality of this economy therefore offers a degree of resilience in the face of crises, since the survival of farmers does not depend exclusively on a single sector. Only the misfortune of a simultaneous crisis in the agricultural and proto-industrial sectors could threaten their livelihoods, a rare occurrence historically. This demonstrates the strength of a diversified economic system, even at the microeconomic level of the rural household.

The introduction of a second source of income marked a significant turning point in the lives of farmers. Although poverty continued to be widespread and the majority of people lived on modest means, the ability to generate additional income through proto-industry helped to reduce the precariousness of their existence. This diversification of income has led to greater economic security, reducing farmers' vulnerability to seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of agriculture. So, even if the overall standard of living did not rise spectacularly, the impact on the security and stability of rural households was substantial. Families were better able to cope with years of poor harvests or periods of rising food prices. What's more, this greater security could translate into a certain improvement in social well-being. With the extra income, families potentially had access to goods and services they would not otherwise have been able to afford, such as better clothes, tools, or even education for their children. In short, proto-industry played a fundamental role in improving the condition of peasants by providing them with a safety net that went beyond subsistence and paved the way for the social and economic changes of the Industrial Revolution.

Triangular Trade: An Overview

L'intégration de la proto-industrie dans le commerce mondial a marqué une transformation significative de l'économie globale. Ce système, également connu sous le nom de putting-out system ou système de la domesticité, a ouvert la voie aux producteurs ruraux pour qu'ils participent pleinement à l'économie de marché, en fabriquant des biens destinés à l'exportation. Ce développement a entraîné une série de conséquences interconnectées. La proto-industrie a conduit à une hausse significative de la demande pour les produits manufacturés, en partie grâce à la mise en place du commerce triangulaire. Ce dernier désigne un circuit commercial entre l'Europe, l'Afrique et les Amériques, où les marchandises produites en Europe étaient échangées contre des esclaves en Afrique, qui étaient ensuite vendus dans les Amériques. Les matières premières des colonies étaient ramenées en Europe pour être transformées par la proto-industrie.

Ce commerce a alimenté l'accumulation de capital en Europe, capital qui a par la suite financé la Révolution industrielle. De plus, l'expansion des marchés pour les biens proto-industriels au-delà des frontières locales a favorisé l'émergence d'une économie de marché plus intégrée et mondialisée. Les structures économiques ont commencé à changer, la proto-industrie ayant pavé le chemin vers la Révolution industrielle en orientant les producteurs vers la production pour le marché et non plus seulement pour leur subsistance personnelle. Toutefois, il est essentiel de reconnaître que le commerce triangulaire comprenait également le commerce des esclaves, un aspect profondément inhumain de cette période historique. Les avancées économiques se sont parfois produites au prix de grandes souffrances humaines, et bien que l'économie ait prospéré, elle l'a fait en causant des torts irréparables à de nombreuses vies, dont l'impact se ressent encore de nos jours.

La proto-industrie, souvent confondue avec le domestic system, se distingue de ce dernier par son ampleur et son impact économique. La proto-industrie a touché un grand nombre de paysans, avec peu de régions agricoles épargnées par ce phénomène. Cette large diffusion est principalement due à la transition des producteurs ruraux des micromarchés locaux vers une économie globale, permettant l'exportation de leurs produits. L'exportation de biens tels que les textiles, les armes et même des articles aussi basiques que les clous a considérablement augmenté la demande globale et stimulé la croissance économique. Cette expansion des marchés a également été le moteur du commerce triangulaire. Ce système a vu les produits de la proto-industrie en Europe échangés contre des esclaves en Afrique, qui étaient ensuite transportés vers les Amériques pour travailler dans les économies de plantation produisant du coton, du sucre, du café et du cacao, lesquels étaient finalement exportés vers l'Europe. Ce flux commercial a non seulement contribué à une hausse de la demande pour les biens proto-industriels mais a aussi provoqué une augmentation du travail dans la construction navale, un secteur offrant de l'emploi à des millions de paysans, réduisant ainsi les coûts de transport et favorisant une croissance économique soutenue. Cependant, il est primordial de rappeler que le commerce triangulaire reposait sur l'esclavage, un système profondément tragique et inhumain, dont les séquelles sont toujours présentes dans la société moderne. La croissance économique qu'il a engendrée est indissociable de ces réalités historiques douloureuses.

La relation entre la croissance de la population et la proto-industrie au XVIIIe siècle est une question de cause à effet complexe qui a été largement débattue par les historiens économiques. D'une part, l'accroissement de la population peut être vu comme un facteur incitant à la recherche de nouvelles formes de revenus, conduisant ainsi au développement de la proto-industrie. Avec une population en augmentation, en particulier dans les campagnes, les terres deviennent insuffisantes pour subvenir aux besoins de tous, forçant ainsi les paysans à trouver des sources de revenus complémentaires, comme le travail proto-industriel qui peut être réalisé à domicile et ne nécessite pas de déplacements importants. D'autre part, la proto-industrie elle-même a pu encourager la croissance démographique en améliorant le niveau de vie des familles rurales et en leur permettant de subvenir mieux aux besoins de leurs enfants. L'accès à des revenus supplémentaires hors de l'agriculture a probablement réduit les taux de mortalité et permis aux familles de soutenir plus d'enfants jusqu'à l'âge adulte. De plus, avec l'augmentation des revenus, les populations étaient mieux nourries et plus résistantes aux maladies, ce qui pouvait également contribuer à une croissance démographique. La proto-industrie représente ainsi une phase de transition entre les économies traditionnelles, basées sur l'agriculture et l'artisanat à petite échelle, et l'économie moderne caractérisée par l'industrialisation et la spécialisation du travail. Elle a permis l'intégration des économies rurales dans les marchés internationaux, aboutissant à une augmentation de la production et à une diversification des sources de revenus. Cela a eu pour effet de dynamiser les économies locales et de les intégrer dans le réseau commercial mondial en expansion.

Les effets démographiques

Impacts sur la Mortalité

Au XVIIIe et au début du XIXe siècle, l'Europe a connu une transformation démographique significative, caractérisée par une baisse de la mortalité, en partie grâce à une série d'améliorations et de changements dans la société. Les avancées dans l'agriculture ont permis d'augmenter la production alimentaire, diminuant ainsi le risque de famines. Parallèlement, des progrès en matière d'hygiène et des initiatives en santé publique ont commencé à réduire la propagation des maladies infectieuses. Même si les avancées majeures en médecine ne surviendront qu'à la fin du XIXe siècle, certaines découvertes préliminaires ont déjà eu un impact positif sur la santé. De plus, la proto-industrialisation a créé des opportunités de revenus supplémentaires en dehors de l'agriculture, permettant ainsi aux familles de mieux résister en période de récoltes médiocres et d'améliorer leur niveau de vie, y compris leur accès à une alimentation de qualité et aux soins de santé. Cette époque a également vu un changement dans la structure économique et sociale, avec des familles qui pouvaient désormais se permettre de se marier plus tôt et d'élever plus d'enfants grâce à une sécurité économique accrue. Le travail industriel à domicile, comme le textile, offrait une sécurité financière supplémentaire qui, associée à l'agriculture, assurait un revenu plus stable et diversifié. Cela a contribué à éroder l'ancien régime démographique où le mariage était souvent retardé par manque de ressources économiques. La convergence de ces facteurs a donc joué un rôle dans la réduction des crises de mortalité, menant à une croissance démographique soutenue et à une transformation des mentalités et des modes de vie. La proto-industrialisation, en offrant un complément de revenu et en favorisant une certaine stabilité économique, a été un élément clé de cette transition, bien que son influence varie grandement d'une région à l'autre.

Influence sur l’Âge au Mariage et la Fécondité

La proto-industrialisation a eu un impact sur la structure sociale et économique des sociétés rurales, et parmi ces effets, on note un recul de l'âge au mariage. Avant cette période, de nombreux petits paysans devaient retarder le mariage jusqu'à ce qu'ils aient les moyens de soutenir une famille, car leurs ressources étaient limitées à ce que leur terre pouvait produire. Avec l'avènement de la proto-industrialisation, ces petits paysans ont pu compléter leurs revenus grâce à des activités industrielles à domicile, telles que le tissage, qui devenaient de plus en plus demandées avec l'expansion du marché. Cette nouvelle source de revenu a rendu le mariage plus accessible à un âge plus jeune, car les couples pouvaient compter sur des revenus additionnels pour subvenir à leurs besoins. De plus, dans ce nouveau modèle économique, les enfants représentaient une main-d'œuvre supplémentaire qui pouvait contribuer au revenu familial dès leur jeune âge. Ils pouvaient, par exemple, travailler sur les métiers à tisser à domicile. Cela signifiait que les familles avaient un incitatif économique pour avoir plus d'enfants et que ces derniers pouvaient contribuer économiquement bien avant d'atteindre l'âge adulte. Cette dynamique a renforcé la viabilité économique du mariage et de la famille élargie, permettant une augmentation de la natalité et contribuant à une croissance démographique accélérée. Cette transition démographique a eu des répercussions profondes sur la société, menant éventuellement à des changements structurels qui ont pavé la voie à l'industrialisation complète et à la modernisation économique.

Le phénomène de proto-industrialisation a eu des effets variables sur les comportements matrimoniaux et la fécondité selon les régions. Dans les zones où la proto-industrialisation fournissait des revenus supplémentaires significatifs, les gens ont commencé à se marier plus tôt et la fécondité a augmenté en conséquence. La possibilité de compléter les revenus agricoles avec ceux provenant du travail industriel à domicile a réduit les obstacles économiques au mariage précoce, car les familles pouvaient nourrir plus de bouches et soutenir des ménages plus larges. Cependant, dans d'autres régions, la prudence économique prévalait et les paysans avaient tendance à reporter le mariage jusqu'à ce qu'ils aient accumulé suffisamment de ressources pour devenir propriétaires fonciers. L'acquisition de terres était souvent considérée comme une garantie de sécurité économique, et les paysans préféraient retarder le mariage et la création d'une famille jusqu'à ce qu'ils puissent assurer une certaine stabilité matérielle. Cette différence régionale dans les comportements de mariage reflète la diversité des stratégies économiques et des valeurs culturelles qui influençaient les décisions des paysans. Alors que la proto-industrialisation offrait de nouvelles opportunités, les réponses à ces opportunités étaient loin d'être uniformes et étaient souvent façonnées par les conditions locales, les traditions et les aspirations individuelles.

Transformation des Rapports Humains: Corps et Environnement

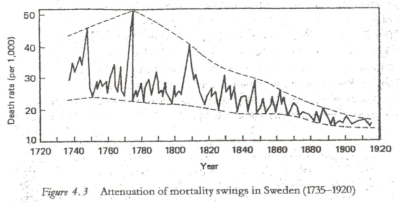

Le graphique représente le taux de mortalité pour 1 000 individus sur l'axe des ordonnées et les années de 1720 à 1920 sur l'axe des abscisses. Une tendance claire est visible sur le graphique : le taux de mortalité, qui présente d'importantes fluctuations avec des pics élevés dans les premières années (notamment autour de 1750 et juste avant 1800), s'aplanit progressivement au fil du temps, les pics devenant moins marqués et le taux global de mortalité diminuant. La ligne pointillée représente une ligne de tendance indiquant la trajectoire générale à la baisse du taux de mortalité sur cette période de deux siècles. Cette représentation visuelle suggère qu'avec le temps, les instances et la sévérité des crises de mortalité (telles que les épidémies, les famines et les guerres) ont diminué, en raison des améliorations dans la santé publique, la médecine, les conditions de vie et des changements dans les structures sociales.

Évolution de la Perception de la Mort

Le changement dans la perception de la mort en Occident pendant le passage du XVIème au XVIIIème siècle reflète une transformation profonde des mentalités et de la culture. Au XVIème et au XVIIème siècles, la mortalité élevée et les fréquentes épidémies faisaient de la mort une présence constante et familière dans la vie quotidienne. Les gens étaient habitués à coexister avec la mort, tant au niveau communautaire qu'individuel. Les cimetières se trouvaient souvent au cœur des villages ou des villes, et les morts faisaient partie intégrante de la communauté, comme en témoignent les rituels et les commémorations. Cependant, au XVIIIème siècle, notamment avec les progrès de la médecine, de l'hygiène et de l'organisation sociale, la mortalité a commencé à reculer, et avec elle, la présence omniprésente de la mort a diminué. Cette diminution de la mortalité quotidienne a conduit à une transformation de la perception de la mort. Elle n'était plus perçue comme une compagne constante, mais plutôt comme un événement tragique et exceptionnel. Les cimetières ont été déplacés à l'extérieur des zones habitées, signifiant une séparation physique et symbolique entre les vivants et les morts. Cette « mise à distance » de la mort coïncide avec ce que de nombreux historiens et sociologues considèrent comme le début de la modernité occidentale. Les mentalités se sont tournées vers la valorisation de la vie, du progrès et de l'avenir. La mort est devenue quelque chose à combattre, à repousser, et, idéalement, à vaincre. Ce changement d'attitude a également conduit à une certaine fascination pour la mort, qui est devenue un sujet de réflexion philosophique, littéraire et artistique, réfléchissant une certaine anxiété face à l'inconnu et à l'inévitable. Cette nouvelle vision de la mort reflète un changement plus large dans la compréhension humaine de soi et de sa place dans l'univers. La vie, la santé et le bonheur sont devenus des valeurs centrales, tandis que la mort est devenue une limite à repousser, un défi à relever. Cela a profondément influencé les pratiques culturelles, sociales et même économiques, et continue de façonner la manière dont la société contemporaine aborde la fin de vie et le deuil.

Le recul de la mortalité au XVIIIème siècle et les changements dans les perceptions et pratiques autour de la mort ont eu des conséquences sur de nombreux aspects de la vie sociale, y compris la justice pénale et les pratiques d'exécution. À l'époque médiévale et au début de l'époque moderne, les exécutions publiques étaient courantes et souvent accompagnées de tortures et de méthodes particulièrement brutales. Ces exécutions avaient une fonction sociale et politique : elles étaient censées être un spectacle dissuasif, un avertissement adressé à la population contre la transgression des lois. Elles étaient souvent mises en scène avec un haut degré de cruauté, ce qui reflétait la familiarité de l'époque avec la violence et la mort. Cependant, au XVIIIème siècle, sous l'influence des Lumières et de la nouvelle sensibilité envers la vie humaine et la dignité, on assiste à une transformation des pratiques juridiques et punitives. Les philosophes des Lumières, comme Cesare Beccaria dans son ouvrage "Des délits et des peines" (1764), ont argumenté contre l'utilisation de la torture et des peines cruelles, plaidant pour une justice plus rationnelle et humaine. Dans ce contexte, les exécutions publiques commencent à être remises en question. Elles sont peu à peu perçues comme barbares et non civiles, et en contradiction avec les nouvelles valeurs de la société. Ce changement de perspective conduit à des réformes dans le système pénal, avec une tendance vers des exécutions plus "humaines" et, finalement, vers l'abolition des exécutions publiques. L'exécution, plutôt que d'être un spectacle public de torture, devient un acte rapide et moins douloureux, avec pour but de mettre fin à la vie du condamné plutôt que de lui infliger une longue souffrance. L'introduction de méthodes comme la guillotine en France à la fin du XVIIIème siècle était en partie justifiée par l'idée d'une exécution plus rapide et moins inhumaine. Le recul de la mortalité et les changements de mentalité qui l'accompagnent ont joué un rôle dans la transformation des pratiques judiciaires, menant à la diminution et finalement à l'arrêt des exécutions publiques et des tortures associées, reflétant une humanisation progressive de la société et de ses institutions.

Au XVIIIe siècle, les cimetières commencent à être déplacés hors des villes, signe d'une transformation profonde dans la façon dont la société considère la mort et les morts. Pendant des siècles, les défunts avaient été enterrés près des églises, au cœur même des communautés, mais cela a commencé à changer pour diverses raisons.

Les préoccupations de santé publique ont gagné en importance avec l'urbanisation croissante. Les cimetières surpeuplés au sein des villes étaient vus comme des menaces potentielles pour la santé, d'autant plus en période d'épidémies. Cette prise de conscience a amené les autorités à repenser l'organisation des espaces urbains pour limiter les risques sanitaires. L'influence des Lumières a également encouragé une nouvelle approche de la mort. Elle n'était plus un spectacle quotidien, mais une affaire personnelle et privée. Il y avait une tendance croissante à considérer les rites mortuaires et le deuil comme devant être vécus de manière plus intime, à l'écart du regard public. En même temps, les conceptions de l'individu évoluaient. On accordait plus de dignité à la personne humaine, vivante comme morte, ce qui s'est traduit par un besoin d'espaces funéraires traitant les dépouilles avec respect et décence. L'esprit de rationalisme de l'époque a aussi joué un rôle. On croyait davantage en la capacité humaine à aménager et à contrôler son environnement. Déplacer les cimetières était une manière de réorganiser l'espace pour améliorer le bien-être collectif, en alignant l'agencement de la ville avec les principes de rationalité et de progrès. Ce déménagement des cimetières était une expression concrète d'un éloignement de la mort de la vie quotidienne, reflétant une volonté de la gérer de manière plus méthodique, et montrait un respect grandissant pour la dignité des morts, tout en marquant un pas vers un contrôle accru sur les facteurs environnementaux affectant la vie publique.

La Lutte contre les Maladies: Progrès et Défis

L'externalisation de la mort au XVIIIe siècle reflète une période où les perspectives sur la vie, la santé et la maladie commencent à se transformer significativement. L'homme de l'époque des Lumières, armé d'une foi nouvelle dans la science et le progrès, commence à croire en sa capacité à influencer, voire à contrôler, son environnement et sa santé. La variole était l'une des maladies les plus dévastatrices, provoquant des épidémies régulières et des taux de mortalité élevés. La découverte de l'immunisation par Edward Jenner à la fin du XVIIIe siècle a été une révolution en termes de santé publique. En utilisant le vaccin contre la variole, Jenner a prouvé qu'il était possible de prévenir une maladie plutôt que de simplement la traiter ou d'en subir les conséquences. Cela a marqué le début d'une nouvelle ère où la médecine préventive devenait un objectif réalisable, renforçant ainsi l'impression que l'humanité pouvait triompher sur les épidémies qui avaient décimé des populations entières par le passé. Cette victoire sur la variole a non seulement sauvé d'innombrables vies mais a également renforcé l'idée que la mort n'était pas toujours inévitable ni un destin à accepter sans lutte. Elle a symbolisé un tournant où la mort, autrefois inextricablement tissée dans le quotidien et acceptée comme partie intégrante de la vie, a commencé à être vue comme un événement que l'on pouvait repousser, gérer, et dans certains cas, éviter grâce à l'avancement de la médecine et de la science.

La variole a été une des maladies les plus redoutées avant le développement des premières méthodes efficaces de prévention. La maladie a eu un impact profond sur les sociétés à travers les siècles, causant des décès en masse et laissant ceux qui survivaient souvent avec de graves séquelles physiques. La métaphore que la variole a pris le relais de la peste illustre le fardeau constant de la maladie au sein des populations avant la compréhension moderne de la pathologie et l'avènement de la santé publique.

L'observation que l'humanité n'aurait pas pu supporter deux fléaux simultanés tels que la peste et la variole met en lumière la vulnérabilité de la population face aux maladies infectieuses avant le XVIIIe siècle. Le cas de figures célèbres comme Mirabeau, qui a été défiguré par la variole, rappelle la terreur que cette maladie inspirait. Malgré l'ignorance de ce qu'était un virus à l'époque, le XVIIIe siècle a marqué une époque de transition où l'on est passé de la superstition et de l'impuissance face aux maladies à des tentatives plus systématiques et empiriques de compréhension et de contrôle. Des pratiques telles que la variolisation, qui impliquait l'inoculation d'une forme atténuée de la maladie pour induire une immunité, ont été développées bien avant que la science ne comprenne les mécanismes sous-jacents de l'immunologie. C'est Edward Jenner qui, à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, a mis au point la première vaccination, en utilisant le pus issu de la variole des vaches (vaccinia) pour immuniser contre la variole humaine, avec des résultats significativement plus sûrs que la variolisation traditionnelle. Cette découverte ne se fondait pas sur une compréhension scientifique de la maladie au niveau moléculaire, qui ne viendrait que bien plus tard, mais plutôt sur une observation empirique et l'application de méthodes expérimentales. La victoire sur la variole symbolise donc un tournant décisif dans la lutte de l'humanité contre les épidémies, ouvrant la voie aux progrès futurs en matière de vaccination et de contrôle des maladies infectieuses, qui allaient transformer la santé publique et la longévité humaine dans les siècles suivants.

L'inoculation, pratiquée avant la vaccination telle que nous la connaissons, était une forme primitive de prévention de la variole. Cette pratique impliquait l'introduction délibérée du virus de la variole dans l'organisme d'une personne saine, généralement par l'intermédiaire d'une petite incision dans la peau, dans l'espoir que cela entraînerait une infection légère mais suffisante pour induire une immunité sans provoquer la maladie complète. En 1721, la pratique de l'inoculation a été introduite en Europe par Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, qui l'a découverte en Turquie et l'a amenée en Angleterre. Elle l'a fait inoculer à ses propres enfants. L'idée était que l'inoculation d'une forme atténuée de la maladie procurerait une protection contre une infection ultérieure, qui pourrait être beaucoup plus sévère ou même mortelle. Cette méthode avait des risques significatifs. Les personnes inoculées pouvaient développer une forme complète de la maladie et devenir des vecteurs de transmission de la variole, contribuant à sa propagation. De plus, il y avait une mortalité associée à l'inoculation elle-même, bien que celle-ci fût inférieure à la mortalité de la variole à l'état naturel. Malgré ses dangers, l'inoculation a été la première tentative systématique de contrôler une maladie infectieuse par l'immunisation, et elle a jeté les bases des pratiques ultérieures de vaccination développées par Edward Jenner et d'autres. L'acceptation et la pratique de l'inoculation ont varié, avec beaucoup de controverses et de débats, mais son utilisation a marqué une étape importante dans la compréhension et la gestion de la variole avant que la vaccination avec le vaccin plus sûr et plus efficace de Jenner ne devienne courante à la fin du XVIIIe et au début du XIXe siècle.

En 1796, Edward Jenner, un médecin anglais, a réalisé une avancée médicale majeure en mettant au point la vaccination contre la variole. Observant que les trayeuses qui avaient contracté la vaccine, une maladie semblable à la variole mais bien moins sévère, transmise par les vaches, ne contractaient pas la variole humaine, il a postulé qu'une exposition à la vaccine pouvait conférer une protection contre la variole humaine. Jenner a testé sa théorie en inoculant James Phipps, un garçon de huit ans, avec du pus prélevé sur des lésions de vaccine. Lorsque Phipps a par la suite résisté à une exposition à la variole, Jenner en a conclu que l'inoculation avec la vaccine (que nous appelons maintenant le virus de la vaccine) offrait une protection contre la variole. Il a appelé ce procédé "vaccination", du mot latin "vacca" qui signifie "vache". Le vaccin de Jenner s'est révélé beaucoup plus sûr que les méthodes précédentes d'inoculation de la variole, et il a été adopté dans de nombreux pays malgré les guerres et les tensions politiques de l'époque. Malgré le conflit en cours entre l'Angleterre et la France, Jenner a assuré que son vaccin atteigne d'autres nations, y compris la France, illustrant une compréhension précoce et remarquable de la santé publique comme une préoccupation transnationale. Cette avancée a symbolisé un tournant dans la lutte contre les maladies infectieuses. Elle a posé les bases de l'immunologie moderne et a représenté un premier pas significatif vers la conquête des maladies épidémiques qui avaient affligé l'humanité pendant des siècles. La pratique de la vaccination s'est répandue et a finalement mené à l'éradication de la variole au XXe siècle, marquant la première fois qu'une maladie humaine a été éliminée grâce aux efforts coordonnés de la santé publique.

La fin du XVIIIe siècle et le début du XIXe siècle marquent un changement fondamental dans l'attitude des sociétés occidentales vis-à-vis de la nature. Avec le recul de la mortalité due aux maladies comme la variole et l'augmentation des connaissances scientifiques, la nature est progressivement passée d'un état de force indomptable et souvent hostile à un ensemble de ressources à exploiter et à comprendre. L'ère des Lumières, avec son accent sur la raison et l'accumulation de connaissances, a conduit à la création d'encyclopédies et à une diffusion plus large du savoir. Des figures telles que Carl Linnaeus ont travaillé à classer le monde naturel, imposant un ordre humain à la diversité du vivant. Cette époque a vu l'essor d'une culture savante où l'exploration, la classification et l'exploitation de la nature étaient considérées comme des moyens d'améliorer la société. C'est aussi à cette période que les premières préoccupations concernant la soutenabilité des ressources naturelles commencent à émerger, en réponse à l'accélération de l'exploitation industrielle. Les débats sur la déforestation pour la construction navale, l'extraction du charbon et du minerai, ainsi que d'autres activités d'exploitation intensive reflètent une prise de conscience naissante des limites environnementales. L'anthropocentrisme de l'époque, qui plaçait l'homme au centre de toutes choses et comme maître de la nature, a stimulé le développement industriel et économique. Cependant, avec le temps, il a également entraîné une prise de conscience croissante des effets environnementaux et sociaux de cette approche, jetant les bases des mouvements écologiques et de conservation qui émergeraient plus tard. Ainsi, le développement d'une culture savante et la valorisation de la nature non seulement comme un objet d'étude mais aussi comme une source de richesse matérielle ont été des éléments clés dans le changement de la relation de l'humanité avec son environnement, une relation qui continue d'évoluer face aux défis environnementaux contemporains.

La culture de la nature

Hans Carl von Carlowitz, un administrateur saxon des mines, est souvent crédité d'être l'un des premiers à formuler le concept de gestion durable des ressources naturelles. Dans son ouvrage "Sylvicultura oeconomica" de 1713, il a développé l'idée que l'on ne devrait couper que le volume de bois que la forêt peut reproduire naturellement, pour garantir que la sylviculture reste productive à long terme. Cette réflexion était en grande partie une réponse à la déforestation massive et aux besoins croissants en bois pour l'industrie minière et comme matériau de construction. Hans Carl von Carlowitz est crédité d'être l'un des pionniers du concept de durabilité, en particulier dans le contexte de la foresterie. Dans ce livre, il a exposé la nécessité d'une approche équilibrée de la sylviculture, qui prend en compte la régénération des arbres parallèlement à leur récolte, afin de maintenir les forêts pour les générations futures. Ceci était une réponse aux pénuries de bois auxquelles l'Allemagne était confrontée au 18ème siècle, en grande partie à cause de la surexploitation pour les activités minières et de fusion. La publication est significative car elle a posé les fondations pour la gestion durable des ressources naturelles, en particulier la pratique de planter plus d'arbres qu'on en coupe, qui est une pierre angulaire des pratiques modernes de sylviculture durable. Il est remarquable que l'idée de durabilité a été conceptualisée il y a plus de 300 ans, reflétant une compréhension précoce de l'impact environnemental de l'activité humaine et de la nécessité de la conservation des ressources.

Bien que les préoccupations de von Carlowitz aient été centrées sur la sylviculture et l'utilisation du bois, son idée reflète un principe de base du développement durable moderne : l'utilisation des ressources naturelles devrait être équilibrée par des pratiques qui assurent leur renouvellement pour les générations futures. À l'époque, c'était un concept avant-gardiste, car il allait à l'encontre de l'idée répandue de l'exploitation illimitée de la nature. Cependant, la notion d'un développement qui serait durable n'a pas immédiatement pris racine dans les politiques publiques ou dans la conscience collective. Ce n'est qu'avec l'évolution des sciences environnementales et les changements sociaux des siècles suivants que l'idée d'une gestion prudente des ressources de la Terre s'est pleinement établie.

L'époque moderne, notamment à partir du XVIIIe siècle, est marquée par un changement fondamental dans la relation de l'humanité avec la nature. La révolution scientifique et les Lumières ont contribué à promouvoir une vision de l'homme comme maître et possesseur de la nature, une idée philosophiquement soutenue par des penseurs comme René Descartes. Dans cette perspective, la nature n'est plus un environnement dans lequel l'homme doit trouver sa place, mais un réservoir de ressources à utiliser pour son propre développement. L'anthropocentrisme, qui place l'être humain au centre de toutes les préoccupations, devient le principe directeur de l'exploitation du monde naturel. La terre, selon la croyance religieuse et culturelle de l'époque, est vue comme un don de Dieu aux hommes qui sont chargés de la cultiver et de l'exploiter. Les développements en agronomie et sylviculture sont des manifestations de cette approche, cherchant à optimiser l'usage du sol et des forêts pour une production maximale. Les voyages d'exploration, alimentés par un désir de découverte mais aussi par des motivations économiques, sont aussi le reflet de cette volonté d'exploiter de nouvelles ressources et d'étendre la sphère de l'influence humaine. Cette culture savante de la nature s'est exprimée à travers la création de systèmes de classification du monde naturel, de l'amélioration des techniques de culture, de l'exploitation minière plus efficace, et de l'exploitation forestière régulée. L'Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert, par exemple, visait à compiler tout le savoir humain, y compris la connaissance de la nature, et à le rendre accessible pour une utilisation rationnelle et éclairée. C'est cette démarche qui a jeté les bases de l'utilisation industrielle des ressources naturelles, préfigurant les révolutions industrielles qui allaient profondément transformer les sociétés humaines et leur rapport à l'environnement. Toutefois, l'exploitation à grande échelle de la nature sans considération pour les impacts environnementaux à long terme mènera plus tard aux crises écologiques que nous connaissons aujourd'hui, et à la remise en question de l'anthropocentrisme en tant que tel.

Annexes

- Vieux Paris, jeunes Lumières, par Nicolas Melan (Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2015) Monde-diplomatique.fr,. (2015). Vieux Paris, jeunes Lumières, par Nicolas Melan (Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2015). Retrieved 17 January 2015, from http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2015/01/MELAN/51961

- Grober, Ulrich. "Hans Carl Von Carlowitz: Der Erfinder Der Nachhaltigkeit | ZEIT ONLINE." ZEIT ONLINE. 25 Nov. 1999. Web. 24 Nov. 2015 url: http://www.zeit.de/1999/48/Der_Erfinder_der_Nachhaltigkeit.