History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts

La pensée sociale d'Émile Durkheim et Pierre Bourdieu ● Aux origines de la chute de la République de Weimar ● La pensée sociale de Max Weber et Vilfredo Pareto ● La notion de « concept » en sciences-sociales ● Histoire de la discipline de la science politique : théories et conceptions ● Marxisme et Structuralisme ● Fonctionnalisme et Systémisme ● Interactionnisme et Constructivisme ● Les théories de l’anthropologie politique ● Le débat des trois I : intérêts, institutions et idées ● La théorie du choix rationnel et l'analyse des intérêts en science politique ● Approche analytique des institutions en science politique ● L'étude des idées et idéologies dans la science politique ● Les théories de la guerre en science politique ● La Guerre : conceptions et évolutions ● La raison d’État ● État, souveraineté, mondialisation, gouvernance multiniveaux ● Les théories de la violence en science politique ● Welfare State et biopouvoir ● Analyse des régimes démocratiques et des processus de démocratisation ● Systèmes Électoraux : Mécanismes, Enjeux et Conséquences ● Le système de gouvernement des démocraties ● Morphologie des contestations ● L’action dans la théorie politique ● Introduction à la politique suisse ● Introduction au comportement politique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : définition et cycle d'une politique publique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise à l'agenda et formulation ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise en œuvre et évaluation ● Introduction à la sous-discipline des relations internationales

Political science, as we know it today, is in fact a relatively young discipline. Its development as a distinct academic field of study dates back about a century. However, the foundations of political thought can be found in much earlier philosophical and literary works.

The tradition of Western political thought has its roots in ancient Greece, with thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle. Their writings on subjects such as justice, power, authority, the role of the state, citizenship and governance laid the foundations for thinking about politics. These ideas were then developed and enriched over the centuries by thinkers such as Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Marx and many others. However, it was not until the 20th century that political science emerged as an academic field in its own right, with its own institutions, academic journals and research methods. This coincided with a movement towards a more empirical and scientific approach to the study of politics, characterised by the use of quantitative methods and a particular focus on the systematisation and verification of theories.

Today, political science is a diverse discipline that encompasses a variety of sub-fields, such as political theory, comparative politics, international relations, public policy, public administration, and gender politics, to name but a few. However, despite this diversity, all political scientists share a common interest in understanding political phenomena.

Defining political science: an intellectual challenge

According to Harold Lasswell, in his 1936 book Politics: Who Gets What, When, How, political science is defined by who gets what, when, and how.[1] In other words, it is the eternal struggle within society for control of scarce resources. These conflicts, between individuals and between social groups, are generated by the desire to share out the resources of an inevitably limited society. This perspective focuses on conflicts relating to the redistribution of scarce resources in a society.

Robert E. Goodin, in 'The State of the Discipline, The Discipline of the State' published in 2009, sees politics as the limited use of social power, presented as the essence of politics.[2] The central concept here is the notion of power, a subject widely explored in the social sciences. According to Max Weber, A's power over B is A's ability to make B do something that B would not have done without A's intervention. This general definition refers to the ability to influence other individuals, groups or states by constraining their behaviour. One of the interests of this definition is to show that power is relational. According to Goodin, power can take many forms, but it is always limited, because even the most powerful cannot impose their will on the dominated by coercion. Power is therefore multidimensional, but always constrained, and the task of political science is to account for these power relations at different levels.

Goodin also proposes another definition, according to which political science is the discipline of the state. Here, the state is understood as a set of norms, institutions and power relations. In terms of norms, the history of the modern state is closely linked to liberal democracy, with specific norms such as the separation of powers, political competition, individual political participation and the political accountability of elected representatives to the electorate. The State is also a set of institutions that embody different forms of politics. The State is thus the privileged locus of power relations between individuals and between groups.

During the twentieth century, political science underwent a significant process of autonomisation, distinguishing itself from related disciplines, particularly history. Historically, political science was largely considered a sub-discipline of history, since it was largely based on the study of the history of institutions, political ideas and social movements. However, as the discipline evolved in the twentieth century, political science began to develop its own methodological approaches, theoretical frameworks and areas of application. One of the key factors in this empowerment was the development of quantitative methodologies and the application of game theory, rationality theory and other concepts from psychology and economics to the analysis of political behaviour. These methodological advances have enabled political science to move away from the narrative study methods of history, to become a more analytical and data-driven discipline. In addition, political science has gradually broadened its field of study to include a wider range of political phenomena, including the analysis of electoral behaviour, the study of decision-making processes within political institutions and the understanding of international power dynamics. Finally, the creation of independent political science departments in universities and the publication of specialist journals have strengthened the discipline's identity as a distinct area of academic research.

James Duesenberry, a renowned economist, highlights the different perspectives that economics and sociology take when studying human behaviour: 'economics only talks about how individuals make choices, sociology only talks about how they have no choices to make'. [3] In economics, the emphasis is on the idea that individuals are rational agents who make choices according to their preferences and the constraints imposed on them, such as income or time. This is based on the concept of economic man or "homo economicus", a hypothetical individual who always seeks to maximise his utility or well-being by making rational choices based on available information. Sociology, on the other hand, is more concerned with the social and cultural context in which individuals are placed, and how these environments shape their behaviour and life options. In other words, sociology often highlights how social structures limit or determine individual choices. For example, a person born into a certain social class may have different opportunities from someone born into another social class, which may limit their choices in terms of education, employment or even lifestyle. In this way, Duesenberry illustrates the tension between methodological individualism, which is typical of economics, and methodological holism, which is more characteristic of sociology. It is important to note that these are two complementary approaches to understanding human behaviour and societies, and that they each offer unique and valuable insights.

What Duesenberry says highlights two contrasting conceptions of the human in neoclassical sociology and economics. On the one hand, sociology tends to have a conception of the 'supersocialised' human, where the behaviour of individuals is largely determined by external social forces. In other words, in this model, the individual is largely influenced by the social structure in which he or she lives. This can include factors such as cultural norms, social roles, social expectations and social institutions. From this perspective, the individual has limited scope to act outside social expectations and constraints. On the other hand, neoclassical economics tends to have an 'under-socialised' view of man, where the individual is seen as operating relatively independently of social influences. In this model, the individual is seen primarily as a rational economic agent who seeks to maximise personal welfare by making rational choices based on available information. Social interactions are often seen as economic transactions, where individuals exchange goods and services to maximise their utility. These two contrasting conceptions of human beings highlight the tension between individualism and collectivism in the analysis of human behaviour. They also highlight the importance of considering both individual and social factors in understanding human behaviour and societies.

Marx highlights the tension between the capacity of individuals to shape their own history and the constraints imposed by existing social and historical conditions: "Men make their own history, but they do not make it arbitrarily under conditions chosen by them, but under conditions directly given to them and inherited from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs heavily on the brain of the living. And even when it seems busy transforming itself, them and things to create something quite new, it is precisely at these times of revolutionary crisis that they fearfully evoke the spirits of the past, that they borrow from them their names, their watchwords, their costumes in order to appear on the new stage of history in this respectable disguise and with this borrowed language." [4]

Marx recognised that individuals play an active role in creating their own history. However, he argues that this process is not arbitrary, but is strongly influenced by the given social and historical conditions inherited from the past. The second part of the quotation highlights the way in which individuals often turn to the past during periods of change and revolution. Even when they seek to create something new, they often resort to historical references, borrowing names, watchwords and costumes from the past. This, according to Marx, shows the extent to which the past weighs heavily on the present, even in moments of radical transformation. In short, Marx sees history not as a simple product of human actions, but as a complex interaction between individual agency and social and historical structures. He emphasises the way in which the past informs and limits the possibilities for change in the present.

Marx's quote illustrates the complex interaction between individual agency - that is, the capacity of individuals to act autonomously and make decisions - and the social and institutional structures in which they find themselves. These structures can include political and economic institutions, cultural norms, class structures, environmental constraints, and more. The tension Marx describes is that between freedom and determination: on the one hand, individuals are free to make decisions and act; on the other hand, the possibilities for action open to them are shaped and constrained by structures that are often beyond their control and largely the product of history. For example, an individual may choose to work hard to achieve economic success, but his or her success will also depend on structural factors such as available education and economic opportunities, social and economic background, the wider political and economic context, and other factors which are largely determined by the history and society in which he or she lives. Moreover, these structures are not only constraints, they also shape the way in which individuals perceive and interpret the world, influencing their aspirations, motivations and conception of what is possible or desirable. Marx reminds us that if individuals make history, they do so under conditions that are not of their own choosing, but inherited from the past.

From ancient origins to modern theories

Ancient Greece, and in particular the 5th century BC, is often regarded as the cradle of Western political thought. During this period, known as the Golden Age of Athens, many fundamental political concepts were developed and debated.

In ancient Greece, politics was a central preoccupation of philosophy. Thinkers of this period concentrated on analysing political ideas and ideals, exploring the properties of different political systems, questioning the essence of citizenship, the role and action of governments, and the intervention of the state in public affairs and foreign policy.

Two emblematic figures of this period are Plato and Aristotle. Plato, in his work The Republic, explored questions of justice, equality and the best form of government. His pupil Aristotle, in his 'Politics', examined the different forms of government, citizenship, and the nature of the political community. These writings laid the foundations of Western political thought and had a considerable influence on the subsequent development of political science.

Plato, the ancient Greek philosopher (427-347 BC), is often regarded as one of the founding fathers of political science. His famous work, "The Republic", is a major text not only for philosophy, but also for political thought. In "The Republic", Plato proposes a typology of different political systems. In particular, he distinguishes between monarchy (which he calls "royalty"), aristocracy, timocracy (government based on honour), oligarchy, democracy and tyranny. Each regime is evaluated according to its justice and efficiency. In addition to this typology, Plato also offers a vision of what he considers to be the ideal state. For him, a just society is one in which each individual fulfils the function best suited to him or her. According to his famous theory of the three classes, society should be divided into rulers (the "guardians"), auxiliaries (the "warriors") and producers (the craftsmen and farmers). Plato's contribution to political science is not limited to the Republic. In other works, such as The Laws, he continued to explore questions relating to political and social organisation. His ideas have had a profound influence on Western political thought and continue to be studied and debated by contemporary political scientists.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) is another major thinker of ancient Greece and a key contributor to political science. His Politics is a fundamental text of political thought, in which he addresses many of the issues that remain central to the discipline to this day. Unlike Plato, Aristotle adopts an empirical and inductive approach to the study of political affairs. Instead of starting with abstract ideas and deducing conclusions, Aristotle preferred observing existing societies and drawing lessons from them. He is known to have studied 158 constitutions of Greek cities to understand the nature and advantages of different political systems. In Politics, Aristotle also proposes his own typology of political regimes, which he divides into six forms: monarchy, aristocracy, polity (a mixture of aristocracy and democracy), tyranny, oligarchy and democracy. Each of these forms is analysed in terms of its advantages and disadvantages, and Aristotle argues in favour of polity as the best form of government. In addition, Aristotle is famous for his conception of politics as fundamentally linked to human well-being. According to him, the purpose of the city (polis) is to enable its citizens to lead a good life. This vision of politics has had a lasting influence on Western political thought.

During the Ancient Greek period, two major themes crystallised that continue to occupy a central place in the field of political science:

- The Institutional Forms of Politics: This question examines the different types of institutional arrangements that structure the political realm. This includes different forms of government, electoral systems, the division of powers, the relationship between government and citizens, etc. In ancient Greece, political thinkers such as Aristotle analysed a variety of city-state constitutions to understand their characteristics and workings.

- L'Evaluation of Institutional Forms: This theme is linked to the normative question of what are the best forms of government or political organisation. This often involves reflection on political and ethical values, such as justice, freedom, equality, etc. For example, Plato in his Republic proposed an ideal vision of the city-state. At the same time, Aristotle argued in favour of polity (a mixture of aristocracy and democracy) as the best form of government.

These two themes recur in debates and research in contemporary political science, albeit with new nuances and different methodological approaches.

The renewal of ideas during the Renaissance

The medieval period was strongly influenced by Christian thought and the theory of natural law. The latter presupposed the existence of a universal law, derived from divine transcendence, that would dictate human conduct and the principles of justice. According to this view, the state or city should structure its institutions and governance in accordance with this natural law.

However, the philosophical and intellectual changes associated with the Renaissance marked a break with this tradition. From that time onwards, political thought began to turn towards a more humanist and secular vision, centred on man rather than divinity. Political thinkers began to explore new conceptions of power, sovereignty and the state, marking a new phase in the evolution of political science.

Machiavelli (1469 - 1527) is best known for his political treatise The Prince, which explores the legitimacy of political regimes and rulers. He is often regarded as a precursor of the realist school, which gave rise to the realist theory of international relations in the 20th century. In a break with the dominant Christian thinking of the time, which saw morality as an end in itself, Machiavelli also saw morality as a means to political ends. In his view, morality could be used as an instrument to achieve certain political ends. This instrumentalist vision of morality marked a significant break with previous conceptions, and had a profound influence on subsequent political thought.

Jean Bodin (1529 - 1596) is best known as a theorist of state sovereignty. In his major work, The Six Books of the Republic, he set out the nature of the state, which he defined by the notion of sovereignty. For Bodin, sovereignty is the fundamental attribute of the State, which holds ultimate and independent power over its territory and population. This concept of sovereignty has had a profound influence on political theory and forms the basis of our modern understanding of the nation state.

The Enlightenment was a period of intellectual ferment and major contributions to political theory. Eminent philosophers and thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Hume and Smith laid the foundations for many of the fundamental notions in the Anglo-Saxon tradition of political science. Thomas Hobbes (1588 - 1679), in his work "Leviathan", developed a theory of absolutism and the social contract, proposing that individuals agree to cede part of their freedom to a sovereign in exchange for security. John Locke (1632 - 1704), often regarded as the father of liberalism, developed a theory of government based on the consent of the governed in his "Two Treatises of Government", and laid the foundations for the theory of natural rights. David Hume (1711 - 1776) contributed to political theory by examining the foundations of society and governance, particularly in his "Essays on Commerce". Adam Smith (1723 - 1790) is best known for his work "The Wealth of Nations", in which he formulated the theory of the market economy and the concept of the "invisible hand". Finally, Alexander Hamilton (1755 - 1804) is one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and played a key role in drafting the American Constitution and defining the American system of government. These thinkers brought diverse and complementary perspectives to bear on subjects such as the role of the state, the nature of individual rights, the organisation of the economy and the structure of government, which continue to influence contemporary political science.

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (1689 - 1755), generally known as Montesquieu, is one of the most influential French philosophers in the field of political science. In his work "De l'Esprit des Lois", published in 1748, he formulated essential ideas on the structuring of political power in a society. Montesquieu proposed a division of political power into three distinct branches: the legislative branch (which makes the laws), the executive branch (which executes the laws) and the judicial branch (which interprets and applies the laws). This idea, known as the theory of the separation of powers, has had a considerable impact on the design of modern political institutions, particularly in democratic systems. According to Montesquieu, the separation of powers aims to prevent the abuse of power and guarantee individual freedoms, by establishing a system of checks and balances between the various powers. The theory of the separation of powers influenced the drafting of the United States Constitution and remains a fundamental principle of constitutional law in many countries.

Late 18th - 19th century: A period of transition

The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the emergence of a number of important thinkers who greatly influenced social theory and political science. They developed complex theories about the structure of society, the nature of power, the relationships between individuals and groups, and other aspects of how society works.

The period from the late eighteenth to the nineteenth century saw the birth of a number of influential thinkers in the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Italy. These thinkers played important roles in the development of political, economic and social philosophy. Their work has influenced a variety of fields, including sociology, philosophy and political science.

- Adam Smith (1723-1790): Known as the father of modern economics, Smith laid the foundations of the market economy and the division of labour. In his book "The Wealth of Nations", he established the principle of the "invisible hand" that guides free markets.

- David Ricardo (1772-1823): Ricardo was an influential economist, best known for his theory of labour-value and his theory of comparative advantage, which is still the basis of most arguments in favour of free trade. His best-known work is "On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation".

- John Stuart Mill (1806-1873): Mill is one of the greatest thinkers of liberalism. He defended individual liberty against state interference in his work "On Liberty". He also contributed to utilitarian theory, arguing that actions should be judged according to their utility or ability to produce happiness.

- Auguste Comte (1798-1857): Considered the father of sociology, Comte introduced the concept of positivism, which advocates the use of the scientific method to understand and explain the social world.

- Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859): Tocqueville is best known for his analysis of American democracy in his book "Democracy in America". He was also a perceptive observer of the social and political trends of his time, including the rise of equality and democratic despotism.

- Herbert Spencer (1820-1903): Spencer had a significant influence advocated a social and economic laissez-faire philosophy and is known for applying Darwin's theory of evolution to human society, a concept often summarised by the phrase survival of the fittest.

- Émile Durkheim (1858-1917): Durkheim is another founding father of sociology. He emphasised the importance of social institutions and introduced concepts such as the social fact, anomie and social solidarity. His work laid the foundations for functionalist sociology.

- Karl Marx (1818-1883): Marx is one of the most influential thinkers in modern history. Together with Friedrich Engels, he developed Marxism, a critical theory of capitalism and class society. His works, including "The Communist Manifesto" and "Capital", laid the foundations of socialism and communism, and influenced a wide variety of disciplines, including political science, sociology and economics.

- Max Weber (1864-1920): Weber is regarded as one of the founders of modern sociology. His work covered a wide range of subjects, including bureaucracy, authority, religion and capitalism. His concept of "ethics of conviction" and "ethics of responsibility" is still widely used in political analysis. His book "Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism" is often cited as a seminal study of the influence of religion on economic development.

- Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923): An Italian economist and sociologist, Pareto is best known for his work on the distribution of wealth and his theory of elites. He introduced the concept of the "Pareto optimum" to economics, which states that a state is optimal if no improvement can be made without worsening an individual's situation.

- Gaetano Mosca (1858-1941): Also a theorist of elites, Mosca emphasised the idea that, in any society, an organised minority will always rule over a disorganised majority. His most famous work, "The Political Class", details this theory.

- Robert Michels (1876-1936): An Italian sociologist of German origin, Michels is known for his theory of the iron oligarchy. In his book "Political Parties", he argued that all forms of organisation, whether democratic or not, inevitably lead to oligarchy, due to the bureaucratic tendencies inherent in all organisations.

19th century: Classical period of social theory

The classical period of social theory in the 19th century saw the emergence of a number of new perspectives on society and human history. Among the most influential was the historical materialism of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, which proposed a deterministic view of history based on class struggle and the development of productive forces. According to Marx and Engels, human history is essentially a history of class conflict, in which economic structures largely determine the political and ideological structures of society. From this perspective, history develops in a linear and progressive fashion, with each mode of production (slavery, feudalism, capitalism) being replaced by the next as a result of internal contradictions and class conflicts. This deterministic and progressive conception of history played a key role in the political philosophy of Marx and Engels, who saw the end of capitalism and the advent of socialism and communism as inevitable stages in human history. These ideas have had a profound and lasting influence on social and political theory, although their implications and validity continue to be debated today.

Against these deterministic and often highly theoretical views of society, a body of empirical work began to emerge in the second half of the nineteenth century. This work sought to examine social realities in a more concrete and detailed way, based on direct observation and the analysis of empirical data. This led to the emergence of new disciplines such as sociology, initiated by figures like Émile Durkheim in France, who stressed the importance of the systematic study of social facts. At the same time, in Germany, Max Weber developed a comprehensive approach to sociology, seeking to understand individual actions and social processes from the point of view of the actors themselves. This empirical work often called into question the great deterministic narratives of history and society, by showing the complexity and variability of social phenomena. They have highlighted the importance of specific historical and cultural contexts, as well as the possibility of multiple trajectories of social and political development. This marked a major break with previous approaches and laid the foundations for many contemporary branches of social science, including political science. It also paved the way for a variety of new methodologies, from ethnography to statistical analysis, which are now standard tools in social and political research.

In reaction to the deterministic trend, many researchers began to undertake detailed descriptive studies of political institutions. It was during this period that Woodrow Wilson, who was to become the 28th President of the United States, wrote "The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics". In this book, Wilson offered an in-depth study of political institutions, constructing a typology of political regimes based on their institutional structure and practices. This reflects an empirical and comparative approach to political science, seeking to understand political systems in terms of their specific characteristics and historical context. This approach can be seen as a modern revival of the classical typologies developed by Plato and Aristotle, but with a greater emphasis on direct observation and detailed analysis. This represented an important contribution to the development of political science as an autonomous discipline, emphasising the value of the systematic study of political institutions for understanding how political systems function.

Woodrow Wilson was not only the 28th President of the United States, but also an eminent academic and political scientist. Before entering politics, Wilson taught at Princeton University, where he was recognised for his important work in political science. One of Wilson's most notable contributions to the discipline was his institutional approach to the study of politics. He argued for particular attention to the analysis of political institutions as key elements of any political system. In addition, he emphasised the importance of practical politics, stressing the need for scholars to understand how political institutions actually work in practice, not just in theory. During his time as President during the First World War, Wilson was able to put some of his political ideas into practice. His presidency was marked by many progressive reforms, and he is best known for his role in creating the League of Nations after the First World War, an institution designed to promote peace and international cooperation.

Both Max Weber and Émile Durkheim made important contributions to sociological theory, addressing themes of modernisation, economic and social development, and democratisation. Max Weber is best known for his concept of the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, which argues that rationalisation, or the process of adopting rational and efficient ways of thinking and behaving, has been a key factor in the development of modern capitalism. He also explored bureaucracy and the concept of rational-legal authority, which lie at the heart of modern governance. Émile Durkheim is regarded as one of the founders of modern sociology. He is famous for his theory of social fact, which argues that social phenomena exist independently of individuals and influence their behaviour. Durkheim also explored the themes of modernisation and social change, notably through his study of suicide and religion. In short, both Weber and Durkheim contributed to our understanding of the processes of modernisation and social change, including economic and political development.

The process of modernisation, for example, remains a key subject of research and debate, particularly in relation to issues of development and democratisation. Researchers continue to examine how societies change as they become more 'modern', how these changes affect governance and politics, and how best to facilitate positive economic and political development. Similarly, social and economic development remains a major concern for political scientists. Researchers are looking at issues such as how economic growth affects social inequalities, how government policies can support development, and how social changes, such as those linked to migration or climate change, affect politics. Finally, democratisation is also an important area of study in political science. Researchers examine how and why democracies emerge, stabilise or fail, and what strategies can support the transition to democracy and its maintenance. These questions are particularly relevant in the current context, where many countries around the world are facing challenges related to democratic governance.

The scientific approach to political science has developed considerably over time. It is characterised by greater rigour in the analysis of political phenomena, a more coherent logic in the arguments presented, and a predominance of the inductive approach over prior assumptions about human nature, as was the case during the Middle Ages. This inductive approach relies on empirical observation and data analysis to formulate hypotheses and theories. Instead of starting from pre-established theories about human nature or the structure of society, researchers observe behaviour and political events, collect data and use this information to develop theories that explain the phenomena observed. This does not mean that political science is devoid of theoretical or philosophical debates. On the contrary, these debates are crucial for guiding empirical research and interpreting results. However, the emphasis on an empirical and inductive approach has helped to reinforce the scientific character of the discipline. In addition, the use of quantitative methods, such as statistics and econometric models, and the increasing accessibility of data, have also contributed to the advancement of political science as a scientific discipline. These tools enable researchers to test their hypotheses rigorously and provide empirical evidence to support their arguments.

The use of the comparative method in political science began to grow during the twentieth century. This method allows researchers to analyse and compare political systems, regimes, policies and processes in different national and international contexts. However, for much of this century, the use of this method was still in its infancy and was not always systematic. The comparative approach aims to identify similarities and differences between the cases studied in an attempt to explain why certain political phenomena occur. For example, it can help to understand why some countries succeed in establishing a stable democracy, while others do not. Over time, the comparative method has developed and become more sophisticated. It has become more systematic, particularly with the development of statistical techniques that make it possible to compare a large number of cases at the same time. Despite this evolution, it is important to note that the comparative method presents challenges. It requires in-depth knowledge of the specific contexts of each case studied, and it can be difficult to control all the variables that could influence the results. In addition, researchers must be careful not to draw too general conclusions from a limited number of cases.

Much of traditional political science has focused on the study of the formal institutions of government, such as parliaments, courts, constitutions and public administrations. These studies have often taken a descriptive, legal and formal approach, focusing on the structure, function and organisation of these institutions. However, it is important to note that the field of political science has evolved and broadened significantly in recent decades. Today, researchers in political science are not limited to the study of the formal institutions of government. They are also interested in a variety of other political phenomena, such as electoral behaviour, social movements, identity politics, global governance, comparative politics, international conflict, and much more. Moreover, the methodologies used in political science have also evolved. Instead of focusing solely on a descriptive approach, many political scientists now use more diverse research methods, including quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods and formal modelling approaches. In sum, although the study of the formal institutions of government remains an important part of political science, the field has broadened and diversified considerably, reflecting a much wider range of topics of interest and research methodologies.

Late 19th and early 20th century: An era of change

It was at the beginning of the twentieth century that political science became truly professional and an autonomous discipline. Several factors contributed to this development. Firstly, the founding of professional organisations, such as the American Political Science Association (APSA) in 1903, played a crucial role. These organisations helped to standardise the practice of political science, establish ethical standards for research and promote the dissemination of research work through conferences and publications. Secondly, the development of doctoral programmes in political science in universities has helped to train a new generation of professional researchers. These programmes have provided a framework for systematic training in political theory, research methods, and the various sub-fields of the discipline. Thirdly, the evolution of political science has been stimulated by the introduction of new research methods, notably quantitative approaches based on statistics. These methods have enabled researchers to examine political issues with an unprecedented degree of rigour and precision. Finally, political science has also benefited from the support of various foundations and funding agencies, which have helped to fund research and promote the development of the discipline. It is thanks to these developments that political science has become a distinct academic discipline, with its own body of knowledge, research methods and professional standards.

Political science as a distinct academic discipline took root primarily in the United States in the early 20th century. The creation in 1880 of the first doctoral school at Columbia University in New York marked the beginning of the institutionalisation of political science as an autonomous field of study in the United States. This step was crucial in establishing political science as a distinct field of academic study. The American Political Science Association (APSA) was then founded in 1903. The APSA became a key organisation for political scientists, providing a platform for the sharing and dissemination of research, as well as a space for professional development and collaboration between scholars. These steps not only set political science apart from other disciplines, but also laid the foundations for the further development of the discipline, both in terms of theoretical research and practical application. Today, political science is a dynamic and diverse field that addresses a wide range of issues related to power, governance and international relations.

According to the British historian Edward Augustus Freeman, "History is past politics, and politics is present history"[5] This quotation highlights the close relationship between political science and history. Indeed, political science can be seen as a branch of history that focuses on the analysis of political systems, institutions and processes, while history can provide a valuable context for understanding the origins and evolution of these systems and processes. However, a key difference between the two disciplines lies in their temporal focus. While history concentrates on the study of the past, political science focuses primarily on the present and the future. It examines contemporary trends and patterns in politics and tries to make predictions or provide policy recommendations for the future. This is why it is often said that "politics is present history". Nevertheless, although the two disciplines have different temporal orientations, they are intimately linked and mutually reinforcing. A thorough understanding of history can enrich our understanding of contemporary politics, while the study of contemporary politics can help us to interpret and understand history.

The approach of political science differs from that of history in terms of generalisation. Whereas history focuses on the uniqueness of each event and its specific circumstances, political science aims to establish theories and models that can be applied to various contexts and moments. This does not mean that political science neglects the specific details or context of an event or phenomenon. On the contrary, it uses these details to identify trends, patterns or factors that can explain a variety of political phenomena. One of the main aims of political science is to create theories that can be generalised, tested and validated under different conditions. This makes it possible to understand the mechanisms underlying political phenomena and to predict how these phenomena may evolve in the future. For example, political science theories can help us understand why some countries are more democratic than others, how political institutions influence the behaviour of citizens and leaders, or what factors can lead to war or peace between nations. In this way, political science complements history by providing conceptual frameworks for understanding large-scale political processes, while benefiting from historical insights to illuminate these frameworks.

Formal, legal and descriptive approaches in political science have certain limitations:

- Description over explanation: Descriptive approaches often provide a detailed view of political events, institutions or processes, but may lack in-depth explanations of why and how these phenomena occur.

- Dependence on law and formal institutions: Legal and institutional analysis is crucial to understanding how political systems work. However, they may neglect non-institutional or non-legal influences on political behaviour, such as social norms, economic pressures, informal power dynamics, etc.

- Weak use of comparative analysis: Comparative analysis is a powerful tool for political science research because it can identify trends, patterns and factors that are constant across different political contexts. However, in the early stages of the discipline, this approach was less widely used, limiting the ability to generalise research findings.

- Lack of empirical approaches: Although political science has increasingly turned to empirical methods, they were not as widespread in the early stages of the discipline. This means that some theories or hypotheses have not been rigorously tested by empirical data, which can limit their validity and reliability.

However, political science has evolved considerably since its early days and has incorporated new methodologies, including more sophisticated empirical approaches, systematic comparative analysis and attention to non-institutional factors in political behaviour.empirical rock. Comparative analysis remains in an embryonic state, as yet underdeveloped.

According to the motto of the time: political science focuses on the contemporary period and history on the past. This motto illustrates the classic distinction between political science and history. History, in general, is concerned with an exhaustive and detailed understanding of past events, people, ideas and contexts. It seeks to describe and explain the past in all its complexity and specificity. Historians often focus on single events and specific contexts, striving to understand the past for its own sake, rather than seeking to draw generalisations or theories. Political science, on the other hand, is primarily concerned with the study of power and political systems in the present and the future. It focuses on concepts such as the state, government, politics, power, ideology and so on. Rather than focusing solely on the detailed study of specific cases, political science seeks to develop theories and models that can be generally applied to various contexts and periods. That said, it is important to note that political science and history are not mutually exclusive. Political scientists can draw valuable lessons from history to understand trends and patterns in political phenomena, while historians can use tools and concepts from political science to analyse the past. The two disciplines complement and enrich each other.

The Chicago School: Towards a behavioural approach

The Chicago School is famous for having advanced sociology by adopting an empirical and quantitative methodology for studying human behaviour in the urban environment. It was this tradition that inspired the behavioural revolution in political science in the 1950s and 1960s. The behavioural revolution marked a major turning point in political science. Instead of focusing primarily on the institutions and formal structures of government, researchers began to take a greater interest in the study of individual behaviour and informal political processes. They began to collect empirical data through surveys, interviews and other research methods to understand how people participate in politics, how they make political decisions, how they interact with the political system and so on. This new approach has greatly enriched our understanding of politics. It also introduced new research methods and techniques to the discipline, such as statistical analysis, the use of formal models and rational choice theories, and the adoption of more systematic comparative frameworks.

The Chicago School was a major force in promoting a new approach to political science. Charles Merriam, who played a key role in the creation of the Chicago School, argued that political science needed to move away from its traditional historical and legal orientation to focus more on the empirical analysis of political behaviour. In his 1929 manifesto, Merriam argued for a 'scientific' approach to political science that would focus on the collection and analysis of empirical data. He also argued that political scientists should adopt an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating ideas and methods from other disciplines, such as psychology, sociology and economics.

The Chicago School became known for its application of empirical and quantitative methods to the study of political behaviour. For example, its researchers used surveys and polls to study political attitudes and voting behaviour, and took a comparative approach to analysing the political systems of different countries. The influence of the Chicago School has been profound and lasting. It laid the foundations for the 'behavioural revolution' that transformed political science in the 1950s and 1960s. And although the behavioural approach has itself been criticised and modified since then, many of the principles of the Chicago School continue to influence the way political science is practised today.

Harold Lasswell, Leonard White and Quincy Wright were key figures in the Chicago School, each making a significant contribution to the behaviourist development of political science. Harold Lasswell, known for his work on models of communication, analysed the role of the media and propaganda in society, developing in particular the "Who says what, to whom, through what channel, with what effect" model. This contribution has had a significant impact on communication and political studies. Leonard White, a pioneer in the study of public administration, helped transform this field into an academic discipline in its own right, and his historical work on public administration in the United States remains an essential reference. Finally, Quincy Wright, a specialist in international relations, produced works such as "A Study of War", in which he attempted to understand scientifically the causes of war and the conditions for peace. This work influenced the way in which international relations are studied, emphasising the importance of empirical and comparative analysis. Together, these scholars shaped political science, focusing particularly on the empirical and behavioural study of political processes.

The Chicago School was particularly interested in the study of political behaviour. From this perspective, two areas of study in particular came to the fore: voting behaviour and social mobilisation in politics. The study of voting behaviour seeks to understand the factors that influence the way individuals vote in elections. This research looks at a wide range of factors, including political attitudes, party affiliations, policy preferences, the influence of the media, as well as socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, race, social class and education. The study of social mobilisation in politics focuses on the processes by which individuals and groups engage in political action. This research explores the motivations of individuals to participate in politics, the tactics and strategies used by groups to mobilise their members and support their causes, and the social and institutional structures that facilitate or hinder political mobilisation. These two areas of study have led to a better understanding of the political behaviour of individuals and groups, and have helped to shape political science as we know it today.

In 1939, Harold Lasswell co-published a study entitled "World Revolutionary Propaganda: A Chicago Study", which examined the impact of the Great Depression of 1929 on the political mobilization capabilities of the unemployed in the city of Chicago.[6] The Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash of 1929, had a devastating economic impact in the United States and elsewhere, leading to massive unemployment and financial hardship for many people. Lasswell's study sought to understand how these difficult economic circumstances affected the ability of unemployed people to engage in political activity. The study used an innovative approach for its time, combining quantitative and qualitative methods to understand political behaviour. It also helped establish the Chicago School as an important centre for the study of political behaviour, and helped lay the foundations for the behavioural revolution in political science that followed.

The Chicago School marked an important turning point in the history of political science by introducing a more empirical and rigorous approach to the study of political behaviour. Rather than focusing solely on political institutions or major historical events, this approach emphasised the importance of individual attitudes and behaviour in the political process. By using more sophisticated and rigorous research methods, including surveys and statistical analysis, the Chicago School was able to produce more accurate and nuanced knowledge about political behaviour. This has improved understanding of a range of political phenomena, from the political mobilisation of the unemployed during the Great Depression to the dynamics of voting in modern elections. In this way, the Chicago School played a key role in the professionalisation and empowerment of political science as an academic discipline, proving that a genuine advance in political knowledge is possible through rigorous empirical study.

The post-behavioural period (1950-1960): New challenges and directions

The behavioural revolution of the 1950s and 1960s marked a significant change in the way political science was studied and understood. This revolution was characterised by an increased focus on the behaviour of individuals and groups in the political context, rather than on formal structures and institutions. Political scientists began to use empirical methods to study how individuals perceive, interpret and respond to political stimuli. This included opinion surveys, media content analysis, and studies of voting behaviour, among others. One of the consequences of this revolution was the development of rational choice theory, which assumes that individuals act to maximise their own benefit. This theory has become a major tool for analysing political behaviour. This period also saw the emergence of new approaches to comparative politics and international relations, which also benefited from the use of empirical and quantitative methods to study political behaviour.

The behavioural revolution marked a major transformation in the study of political science. It was characterised by two main ideas:

- Broadening the scope of political science: The proponents of this revolution challenged the traditional view that limited political science to the study of the formal institutions of government. They sought to go beyond this limitation by integrating the study of informal procedures and the political behaviour of individuals and groups, such as political parties. These informal procedures can include processes for formulating new public policies, which often involve consultation with organised interest groups such as trade unions and other civil society associations. These processes, although not institutionalised, play a key role in politics and can be described as informal institutions.

- The desire to make political science more scientific: The proponents of the behavioural revolution questioned the empirical approach, which is not informed by theory. They advocated rigorous and systematic theoretical reasoning that could be tested by empirical studies. This approach led to the establishment and testing of theoretical hypotheses, using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

The behavioural revolution had a major impact on political science, broadening its field of study and insisting on a more rigorous and scientific approach.

The post-war period saw a significant expansion and diversification of political science research. International relations, for example, became a major sub-discipline, focusing on the phenomena of war, peace and cooperation on a global scale. At the same time, comparative politics has emerged as an essential field of study, offering a comparative perspective on political systems and institutions around the world. Attention to the specific political institutions of the United States has also increased, allowing for a more in-depth analysis of that particular system. New sub-disciplines have emerged, further broadening the spectrum of political science. Security studies, for example, began to focus on national and international security challenges and strategies. In addition, international economic relations have been identified as a crucial area of study, bridging politics and economics on a global scale. Finally, the study of political behaviour took on increasing importance, with a focus on understanding the actions and behaviours of individuals and groups in the political context. In sum, this post-war period marked a turning point in political science, deepening its multidisciplinary nature and broadening its scope for understanding the complexities of politics.

The University of Michigan played a major role in promoting the behavioural approach to political science in the post-war period. Its political science department emphasised empirical studies and fostered a scientific culture in the study of politics. In particular, the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan was a pioneer in research on political behaviour. The centre is famous for launching the American National Election Studies (ANES), a longitudinal study that has collected data on the voting behaviour, political opinions and attitudes of American citizens since 1948. This study has provided invaluable data for understanding how and why individuals participate in political life. The University of Michigan's emphasis on the empirical study of political behaviour has helped move the field of political science beyond purely institutional and legal analysis to include a deeper understanding of how individual actors and groups behave in the political context.

Two major publications of this period, which fully symbolise this behavioural revolution, are "Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics" by Seymour Martin Lipset, published in 1960[7], and "The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations" by Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, published in 1963.[8] These two books were highly influential and marked the period of the behavioural revolution in political science. Seymour Martin Lipset's "Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics" was published in 1960 and has become a classic in the field of political sociology. Lipset uses an empirical approach to examine the social and economic conditions that contribute to democratic stability. In particular, he looks at factors such as the level of economic development, the education system, religion, social status and other social factors to understand patterns of political behaviour. "The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations was published in 1963 by Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba. The book presents a comparative analysis of political cultures in five countries (United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Mexico) and proposes the concept of "civic culture" to explain democratic stability. Almond and Verba argue that a country's political culture, reflected in citizens' attitudes and beliefs towards the political system, plays a crucial role in the functioning and stability of democracy. Both books reflect the behavioural revolution's emphasis on the study of people's attitudes, beliefs and behaviours in order to understand politics.

The behavioural revolution marked a significant turning point in the discipline of political science by emphasising the importance of theories in the analysis and understanding of political phenomena. This reorientation towards a more theoretical approach has made it possible to introduce new concepts and analytical tools, thereby enriching the field of the discipline. One of the main impacts of this revolution has been the strengthening of theoretical arguments in political analysis. Instead of relying solely on descriptive observations and suppositions, researchers began to formulate more solid hypotheses and theories to explain political behaviour. This has led to more nuanced debates and a deeper understanding of political processes. In addition, the behavioural revolution also introduced greater sophistication to political theory. With the adoption of a more scientific approach, researchers have developed more complex and accurate theoretical models to explain a wide variety of political behaviours and phenomena. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the behavioural revolution promoted a more rigorous consideration of the scientific method in the study of politics. This means that researchers have begun to adopt more rigorous and systematic research methods, including the use of statistics and other quantitative tools. This has led to greater reliability and validity of research results, thereby enhancing the credibility of the discipline of political science as a whole.

The third scientific revolution (1989 - present): The new face of political science

La troisième révolution scientifique de la science politique, qui a commencé dans les années 1970, a eu un impact majeur sur la façon dont la recherche politique est menée aujourd'hui. Cette révolution a introduit des méthodes de recherche plus rigoureuses et systématiques, y compris l'utilisation de statistiques et de modèles mathématiques pour tester des hypothèses et mesurer l'impact de différents facteurs sur les phénomènes politiques. Elle a également encouragé les chercheurs à adopter une approche plus empirique, basée sur l'observation et l'expérience plutôt que sur la théorie pure. La troisième révolution scientifique a également vu une expansion des domaines d'étude de la science politique. Les chercheurs ont commencé à explorer de nouveaux domaines tels que le comportement électoral, la politique comparative, la politique de l'identité, la politique environnementale, et d'autres. Ces nouveaux domaines d'étude ont permis d'élargir considérablement notre compréhension du fonctionnement de la politique et du rôle des facteurs politiques dans la société. Cette révolution a également introduit une plus grande diversité dans la recherche en science politique. Les chercheurs ont commencé à étudier une gamme plus large de contextes politiques et à prendre en compte des perspectives plus diverses. En outre, cette révolution a également encouragé une plus grande collaboration interdisciplinaire, avec des chercheurs en science politique travaillant avec des experts d'autres disciplines pour résoudre des problèmes politiques complexes.

La Théorie du choix rationnel (TCR) est une approche importante et influente dans la science politique qui est principalement inspirée de la théorie économique. Cette théorie suppose que les individus sont des acteurs rationnels qui prennent des décisions en fonction de leurs intérêts personnels, en cherchant à maximiser leur utilité, c'est-à-dire le bénéfice ou le plaisir qu'ils tirent d'une certaine action. Les individus, selon la TCR, pèsent les coûts et les bénéfices de différentes options avant de prendre une décision. Cette évaluation des coûts et des bénéfices peut prendre en compte de nombreux facteurs différents, y compris les conséquences matérielles, le temps, l'effort, les risques et les récompenses émotionnelles et sociales. La TCR sert souvent de "métathéorie" dans la recherche en science politique. Cela signifie qu'elle fournit un cadre général pour comprendre comment et pourquoi les individus prennent certaines décisions politiques. Par exemple, elle peut être utilisée pour analyser des questions telles que le comportement électoral (pourquoi les gens votent-ils comme ils le font?), la formation de coalitions (pourquoi certains partis politiques s'allient-ils avec d'autres?), ou la prise de décision en politique étrangère (pourquoi les pays choisissent-ils de déclarer la guerre ou de signer des traités de paix?).

La troisième révolution scientifique en science politique a mis l'accent sur l'utilisation de raisonnements logiques rigoureux et de méthodes formelles. Dans ce contexte, la théorie du choix rationnel (TCR) est un exemple majeur de cette approche. La TCR, et d'autres approches similaires, commencent souvent par établir un ensemble de postulats ou d'hypothèses de base. Ces postulats sont censés représenter certains aspects fondamentaux du comportement humain ou du système politique. Par exemple, la TCR postule généralement que les individus sont des acteurs rationnels qui cherchent à maximiser leur utilité. À partir de ces postulats de base, les chercheurs déduisent ensuite logiquement un certain nombre de propositions ou d'hypothèses. Par exemple, si on suppose que les individus sont rationnels et qu'ils cherchent à maximiser leur utilité, on pourrait en déduire que les individus seront plus susceptibles de voter s'ils pensent que leur vote aura un impact sur le résultat de l'élection. Ces propositions ou hypothèses sont ensuite testées empiriquement, souvent à l'aide de données quantitatives. Par exemple, un chercheur pourrait recueillir des données sur le comportement électoral et utiliser des techniques statistiques pour tester l'hypothèse que les individus sont plus susceptibles de voter s'ils pensent que leur vote a un impact. Cette approche a l'avantage de fournir des prédictions claires et testables, et elle a contribué à améliorer la rigueur et la précision de la recherche en science politique. Cependant, comme mentionné précédemment, elle a également fait l'objet de critiques, notamment en raison de ses hypothèses simplistes sur le comportement humain.

La théorie des jeux, une branche de la mathématique qui étudie les situations de décision où plusieurs acteurs interagissent, a été intégrée à la science politique dans le cadre de la troisième révolution scientifique. Elle offre un cadre formel pour analyser des situations où le résultat pour un individu dépend non seulement de ses propres choix, mais aussi de ceux des autres. Elle est souvent utilisée dans des contextes politiques pour modéliser des situations de conflit et de coopération, telles que les négociations, les élections, la formation de coalitions et la prise de décisions en politique étrangère. La théorie des jeux se prête bien à la théorie du choix rationnel, car elle part du principe que les acteurs sont rationnels et cherchent à maximiser leur utilité. Cependant, elle va au-delà de la simple maximisation de l'utilité individuelle pour considérer la manière dont les choix des autres acteurs peuvent influencer les résultats. Quant à l'analyse statistique, elle est devenue une méthode de recherche standard en science politique à partir de la troisième révolution scientifique. Les chercheurs utilisent des méthodes statistiques pour analyser des ensembles de données de grande taille et pour tester des hypothèses sur les relations entre différentes variables. L'analyse statistique peut aider à identifier des tendances, à établir des corrélations, à prédire des résultats futurs et à vérifier l'efficacité de différentes politiques. En utilisant ces outils - la théorie des jeux et l'analyse statistique - la science politique a gagné en rigueur, en précision et en capacité à tester et à valider ses théories. Cependant, comme toujours, ces méthodes ont leurs limites et leurs défis, et les chercheurs continuent à débattre de la meilleure façon de les utiliser dans la pratique.

La troisième révolution scientifique en science politique a eu un impact majeur sur toutes les facettes de la discipline, y compris les méthodes de recherche qualitatives. En réponse à la rigueur et à la précision apportées par les méthodes quantitatives, les chercheurs utilisant des méthodes qualitatives ont cherché à renforcer leurs propres approches. Par exemple, ils ont travaillé à développer des cadres plus systématiques pour la collecte et l'analyse de données qualitatives, et à améliorer la transparence et la reproductibilité de leurs recherches. Ils ont également cherché à intégrer des éléments de rigueur statistique dans leur travail, par exemple en utilisant des méthodes de codage pour analyser systématiquement des textes ou des entretiens. De plus, les chercheurs qualitatifs ont également mis l'accent sur les avantages uniques de leurs méthodes. Par exemple, ils soulignent que la recherche qualitative peut fournir une compréhension plus profonde et plus nuancée des phénomènes politiques, en se concentrant sur le contexte, l'interprétation et le sens. Ils ont également défendu le rôle de la recherche qualitative dans la génération de nouvelles théories et dans l'étude de phénomènes qui sont difficiles à mesurer ou à quantifier. De cette manière, la pression des méthodes quantitatives et de la théorie du choix rationnel a effectivement conduit à un renforcement de la recherche qualitative en science politique. Cela a contribué à un équilibre plus sain entre les méthodes qualitatives et quantitatives dans la discipline, et a encouragé une approche plus intégrative qui valorise la contribution de chaque méthode à la compréhension du politique.

L'influence de la troisième révolution scientifique a eu un impact étendu sur tous les domaines de la science politique, y compris la recherche qualitative. De nombreux ouvrages majeurs ont été écrits pour répondre à ces changements, illustrant comment les chercheurs ont cherché à renforcer la rigueur et la systématicité de la recherche qualitative. Par exemple, "Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research" de King, Keohane et Verba en 1994, est un ouvrage clé qui a mis en avant une approche de la recherche qualitative axée sur des principes de rigueur scientifique similaires à ceux de la recherche quantitative.[9] Brady et Collier ont pris le relais en 2004 avec "Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards", qui plaide pour une complémentarité entre les méthodes quantitatives et qualitatives afin d'approfondir la compréhension des phénomènes sociaux. Ils ont également présenté divers outils et techniques pour améliorer la qualité de la recherche qualitative.[10] Poursuivant dans la même veine, George et Bennett ont publié en 2005 "Case Studies and Theory Development", un ouvrage qui fournit des stratégies pour utiliser les études de cas pour développer et tester des théories en science politique.[11] Enfin, en 2007, Gerring a ajouté à ce corpus avec "Case Study Research: Principles and Practices", qui offre un guide complet pour la recherche basée sur les études de cas.[12] Ces travaux montrent comment la recherche qualitative en science politique a répondu et évolué face à la troisième révolution scientifique. Ils soulignent l'importance d'une approche rigoureuse et systématique de la recherche qualitative tout en reconnaissant les forces uniques de cette méthode.

Pour conclure cette revue générale, nous pouvons simplifier certains de ces paradigmes importants en une seule idée. En effet, chaque approche peut être résumée par un adage qui capture bien les contributions de la théorie du behavioralisme et du choix rationnel :

- Le béhaviorisme, ou behavioralisme, s'intéresse aux actions et au comportement des individus plutôt qu'à la simple structure institutionnelle. En suivant le principe de "ne vous contentez pas de regarder les règles formelles, regardez ce que les gens font réellement", le behavioralisme met l'accent sur l'observation et l'étude des actions réelles des individus et des groupes, en tenant compte à la fois des règles formelles et informelles qui guident ces actions. Il a joué un rôle majeur dans le déplacement de l'analyse politique vers une compréhension plus profonde des comportements individuels et de groupes.

- La théorie du choix rationnel, quant à elle, se fonde sur le principe que "les individus sont motivés par le pouvoir et l'intérêt". Elle soutient que les individus prennent des décisions en fonction de leurs intérêts personnels et cherchent à maximiser leur utilité. En suivant cette ligne de pensée, la théorie du choix rationnel a permis de formaliser l'analyse des actions politiques et de prédire les comportements en se basant sur le postulat de la rationalité.

Ces deux paradigmes ont apporté des contributions significatives à la science politique et continuent de façonner notre compréhension du comportement politique. Cependant, il est également important de noter que chaque paradigme a ses limites et qu'une compréhension complète des phénomènes politiques nécessite souvent une combinaison de différentes approches et méthodes. En plus du behavioralisme et de la théorie du choix rationnel, deux autres grandes écoles de pensée en science politique sont le systémisme et le structuralisme-fonctionnalisme. Le systémisme opère selon le principe que "tout est connecté, les rétroactions sont essentielles". Cette philosophie souligne l'interdépendance de tous les éléments d'un système politique. Il met l'accent sur l'importance des rétroactions qui, en créant des résultats, sont réintégrées dans les nouvelles demandes adressées au système politique, influençant ainsi sa dynamique et son évolution. D'autre part, le structuralisme-fonctionnalisme est guidé par l'idée que "la forme s'adapte à la fonction". Cette perspective postule que les fonctions des institutions politiques déterminent leurs formes. C'est un cadre utile pour comprendre comment les institutions politiques se développent et changent pour répondre aux besoins et aux demandes de la société.

Enfin, l'institutionnalisme est une autre école de pensée importante en science politique, qui opère selon le principe que "les institutions comptent". En effet, une branche entière de cette école, connue sous le nom d'institutionnalisme historique, s'est développée autour de cette idée. L'institutionnalisme historique se concentre sur l'importance des institutions dans la détermination des résultats politiques, en mettant l'accent sur leur rôle en tant que règles du jeu qui façonnent les comportements politiques, et sur la manière dont elles évoluent et changent avec le temps.

Le récit que nous venons de parcourir correspond à ce que Almond a défini comme la "perspective progressiste-éclectique" de l'histoire de la science politique.[13] Cette perspective, qui peut être considérée comme le courant dominant de la science politique, reconnaît la valeur de plusieurs approches différentes dans la discipline. Elle met l'accent sur le progrès scientifique réalisé à travers l'intégration d'éléments provenant de différentes écoles de pensée, y compris le behavioralisme, la théorie du choix rationnel, le systémisme, le structuralisme-fonctionnalisme et l'institutionnalisme. Selon cette perspective, chaque approche apporte des outils et des perspectives uniques qui, ensemble, contribuent à une compréhension plus complète des phénomènes politiques.

Cette "perspective progressiste-éclectique" n'est pas universellement acceptée, mais elle est largement acceptée par ceux qui adhèrent à sa définition de la connaissance et de l'objectivité, qui est basée sur la séparation des faits et des valeurs, et l'adhésion à des normes de preuve empirique.

L'idée de "progressiste" se réfère à l'engagement envers l'idée de progrès scientifique, qui se manifeste à la fois par une accumulation quantitative de connaissances - en termes du volume de connaissances accumulées au fil du temps - et par une amélioration qualitative de la rigueur et de la précision de ces connaissances.

L'aspect "éclectique" de la perspective décrit une approche non hiérarchique et intégrative du pluralisme. Cela signifie qu'aucune approche ou école de pensée n'est considérée comme supérieure aux autres. Toutes les perspectives et méthodologies sont accueillies et peuvent contribuer à la somme totale de la connaissance dans cette vision dominante de la science politique. Par conséquent, des approches telles que la théorie du choix rationnel et l'institutionnalisme peuvent produire des travaux qui s'intègrent bien dans cette perspective progressiste-éclectique.

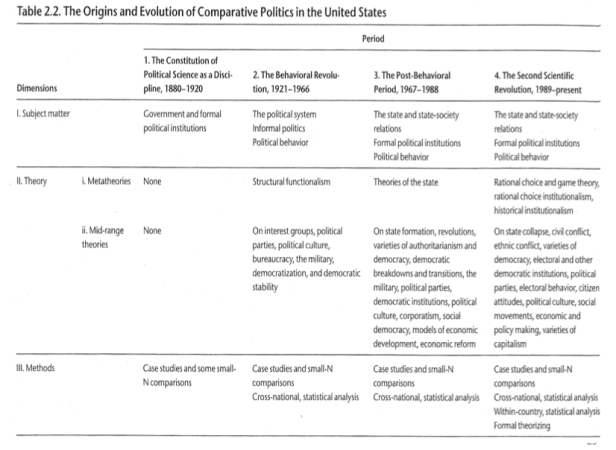

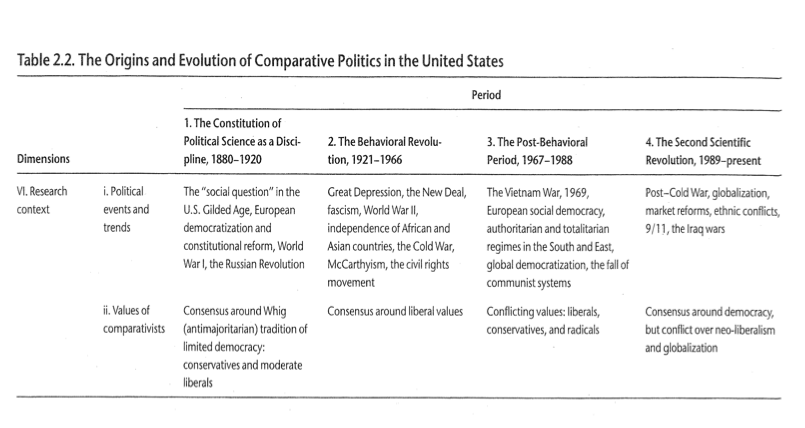

Ces résumés représentent l'évolution de la discipline en décrivant les différentes révolutions et classifications. Ils illustrent également le développement des méthodes au fil du temps :

Histoires alternatives de la discipline

Bien que la "perspective progressiste-éclectique" soit largement acceptée, il est important de noter qu'il existe d'autres écoles de pensée qui offrent des histoires alternatives de la science politique. Ces perspectives peuvent différer sur des questions clés, comme l'importance relative des différentes approches ou l'évolution de la discipline au fil du temps. Elles peuvent également mettre l'accent sur différents aspects de la science politique, ou interpréter différemment les mêmes événements ou tendances. Ces histoires alternatives contribuent à la richesse et à la diversité de la science politique en tant que discipline.

Les courants contestataires : Antiscience et post-science

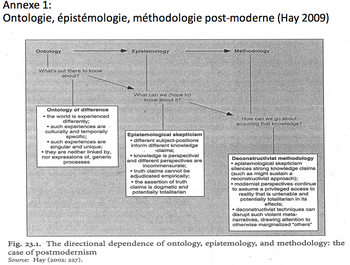

Il existe des courants de pensée en science politique qui rejettent l'idée que la discipline est intrinsèquement scientifique et progressiste. Certains courants postmodernistes et post-structuralistes, par exemple, peuvent remettre en question l'idée que la science politique peut être une entreprise purement objective ou neutre. Ils suggèrent que toutes les connaissances sont enracinées dans des contextes culturels, sociaux et historiques spécifiques, et que la soi-disant "objectivité" peut souvent masquer des formes de pouvoir et de domination. D'autres courants, comme le féminisme ou la théorie critique, peuvent également rejeter l'idée du progrès linéaire en science politique. Ils pourraient souligner que les avancées dans la connaissance ne profitent pas toujours également à tous, et que certaines voix ou perspectives peuvent être marginalisées dans le processus. Ces courants offrent une critique importante de l'orthodoxie dominante en science politique, et ils ont contribué à stimuler un débat et une réflexion importants sur la nature de la connaissance et de la recherche en science politique.

L'antiscience : Une critique du scientisme

La position "antiscience" en science politique est généralement associée à des penseurs comme Claude Lévi-Strauss. Cette perspective critique la division weberienne entre faits et valeurs et remet en question l'idée que nous pouvons objectiver la réalité sociale. De plus, elle rejette le behavioralisme et, plus généralement, le positivisme, qui cherche à étudier les phénomènes politiques de manière causale et empirique.

Pour ceux qui adoptent une perspective antiscience, l'introduction de méthodes scientifiques en science politique est non seulement illusoire, mais elle peut aussi nuire à notre compréhension de la dynamique sociale. Ils suggèrent que l'accent mis sur la rigueur empirique et l'objectivité peut obscurcir les complexités et les nuances de la vie sociale et politique, et réduire ces phénomènes à des éléments triviaux ou simplistes.

Il est important de noter que bien que cette position soit critique à l'égard des méthodes scientifiques traditionnelles, elle n'est pas nécessairement contre toute forme de recherche ou d'analyse. Au contraire, beaucoup de ceux qui adoptent une position antiscience soutiennent des formes alternatives de recherche, qui mettent l'accent sur l'interprétation, le contexte et la signification.

Claude Lévi-Strauss défend une approche de la science sociale qui soit à la fois humaniste et engagée. Cette approche envisage une collaboration intime et passionnée avec les grands philosophes et les grandes philosophies pour discuter et comprendre le sens des idées centrales de la science politique. Pour Lévi-Strauss, la science sociale doit viser à interpréter les phénomènes sociaux plutôt qu'à simplement les expliquer de manière mécanique ou causale.