地结构与乡村社会: 前工业化时期欧洲农民分析

根据米歇尔-奥利斯(Michel Oris)的课程改编[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

15 世纪至 18 世纪期间,前工业化时期的欧洲基本上是由一片片广阔的农村社区组成的,在那里,农民的生活绝不仅仅是背景,而是文明跳动的心脏。农民的就业率约占总人口的 90%,他们不仅耕种土地,还是经济的中坚力量,他们塑造景观,培育民族,编织社会纽带,将村庄和土地联系在一起。他们每天在土地上辛勤劳作,不仅仅是为了生存;这是基本自给自足的经济背后的驱动力,是为市场和城市提供食物的伟大社会机器的关键组成部分。

在这一农业棋盘中,每个农民都扮演着决定性的角色,参与到密集的职责网络中,不仅要对当地领主负责,还要发扬相互团结的精神。农民的生活条件往往很艰苦,受制于严酷的季节和贵族的任意要求,但他们以顽强的毅力塑造了他们时代的经济。把他们仅仅描绘成一个弱势和无权无势的阶级是简单化了;他们代表了前工业化欧洲最大的社会群体,是塑造欧洲未来的关键角色,有时甚至是革命性的角色。

我们将深入探讨前工业化时代欧洲农民鲜为人知的日常生活,不仅揭示他们的耕作方式,而且揭示他们在社会等级制度中的地位,以及他们能够产生的反抗和变革的动力。通过将他们重新置于分析的中心,我们重新发现了欧洲前工业化经济和社会的根本基础。

农业占主导地位: 15 世纪 - 17 世纪

农业是旧制度经济的支柱,在塑造当时的社会职业结构方面起着主导作用。这一经济组织的核心是三大活动分支:涵盖农业活动的第一产业[1]、涵盖工业的第二产业[2]和涵盖服务业的第三产业[3]。16 世纪,欧洲的人口构成基本上是农村和农业人口,约有 80% 的居民务农。这一数字表明,每五个人中就有四个人与土地相依为命,这一压倒性的比例证明了农民在当时的经济生活中根深蒂固。第一产业不仅是最大的雇主,也是人们日常生活的基石,欧洲大部分劳动力都从事耕种土地、饲养牲畜和其他许多农业工作。

本表显示了发达市场经济国家(日本除外)劳动人口在第一产业(农业)、第二产业(工业)和第三产业(服务业)之间的分布变化情况。所给出的百分比反映了从 1500 年到 1995 年各部门在总劳动人口中所占的比例。在研究期开始时,即 1500 年,农业雇用了约 80%的劳动人口,而工业和服务业各占约 10%。1750 年,这一分布略有变化,农业略微下降到 76%,工业上升到 13%,服务业上升到 11%。1800 年,农业仍占 74%,但工业继续上升到 16%,服务业仍占 11%。1913 年发生了重大转变,农业占劳动人口的 40%,工业紧随其后,占 32%,服务业占 28%。这一转变在 20 世纪下半叶变得更加明显。1950 年,农业就业人口占劳动人口的 23%,工业占 37%,服务业占 40%,这表明经济日益多样化。到 1970 年,服务业超过了所有其他行业,占 52%,工业占 38%,农业仅占 10%。这一趋势在随后的几十年中一直持续:1980 年,农业下降到 7%,工业占 34%,服务业占 58%。到 1990 年,服务业增加到 66%,农业只占 5%,工业占 29%。最后,在 1995 年,服务业基本上占主导地位,达到 67%,而工业则略微下降到 28%,农业保持在 5%,这反映出世界经济正大力向服务业倾斜。这组数据显示了发达经济体从农业占主导地位到服务业占主导地位的明显转变,说明了几个世纪以来经济结构的深刻变化。

要理解农业在旧制度经济中的主导地位,必须牢记农业生产的货币价值远远超过其他生产部门。事实上,当时社会的财富是以农业为基础的,农业生产在相当大的程度上主导着经济,成为主要的收入来源。因此,财富的分配与农业有着内在的联系。在这种情况下,占人口大多数的农民完全依靠农业为生。他们的食物直接来自于自己的种植和收获。这些社会的特点是经济货币化程度低,明显倾向于以物易物,即直接交换商品和服务的制度。然而,尽管倾向于以物易物,农民仍然需要钱来支付教会和各级政府要求的税收。这种对货币的需求在一定程度上与农民日常经济的非货币化性质相矛盾,凸显了农民在管理资源和履行纳税义务时所面临的矛盾需求。

在旧制度社会中,经济结构带有强烈的社会分层和阶级特权特征。贵族和教士是当时的精英阶层,他们的收入主要来自第三阶层,即占人口绝大多数的农民和资产阶级的贡献。这些精英阶层通过对农田(通常由农民耕种)征收的宗主权和教会什一税致富。农民则必须将其生产或收入的一部分以税收和地租的形式缴纳,从而构成了贵族土地收入和神职人员教会收入的基础。这种税收制度对第三等级来说负担更重,因为贵族和神职人员都不需要纳税,而是享受各种豁免和特权。因此,税收负担几乎完全落在了农民和其他非特权阶层的肩上。这种经济态势凸显了精英阶层与农民生活条件之间的鲜明对比。前者虽然在数量上处于劣势,但其生活费用却来自于对后者的经济剥削,后者尽管对经济和社会结构做出了重要贡献,却不得不承担与其财力不相称的税收负担。这导致财富和权力集中在少数人手中,而大众则生活在持续的物质不安全中。

储蓄在旧政体的经济中发挥着至关重要的作用,因为储蓄是投资的基础。事实上,正是由于有了储蓄能力,个人和家庭才有能力购买生产性资产。在农业是经济基石的背景下,投资土地正成为一种常见的潜在获利方式。因此,购买森林或其他大片农田成为一种受青睐的投资方式。资产阶级,尤其是像日内瓦这样的繁华都市的资产阶级,认识到了这种投资的价值,往往将积蓄用于购买葡萄园。这种被认为比手工业或服务业更有利可图的活动吸引了那些有投资能力的人的注意。他们从农民的劳动中获利,农民代表他们耕种土地,使他们能够从生产中获利,而不一定直接参与耕作。即使是城市商人,只要积累了足够的财富,也会在农村购买土地,扩大投资组合,使收入来源多样化。这说明,即使在城市中,经济也与土地及其开发密切相关。然而,必须指出的是,农业部门并非千篇一律。农业部门的特点是情况千差万别:一些地区专门种植特定作物,另一些地区则以畜牧业著称,而耕作效率则因耕作方法和现行产权的不同而大相径庭。这种差异反映了农业经济的复杂性以及土地创收的不同方式。

耕作制度的多样性

随着中世纪的结束和随后时期的发展,欧洲内部出现了显著的地区差异,尤其是东西部和南北部之间的差异。这种差异尤其体现在农民的地位和现行的土地制度上。

西欧的大多数农民在现代开始时获得了某种形式的自由。这种解放是逐步实现的,这主要归功于封建结构的削弱以及生产和财产关系的变化。在西方,这些发展使农民成为自由农民,拥有更大的权利和更好的生活条件,尽管他们仍然受到各种形式的经济限制和依赖。然而,在想象中的圣彼得堡--特里亚斯特一线以东,情况却有所不同。所谓的 "第二农奴制 "正是在这一地区形成的。这种现象的特点是,农民身上的重重束缚加强了,他们发现自己再次被一种依附于领主并对领主承担义务的制度拴在了土地上。农民的权利受到很大限制,他们往往被迫在没有足够补偿的情况下耕种领主的土地,或将其生产的很大一部分作为地租支付。这种地理上的两极分化反映了前工业化欧洲在社会经济和法律方面的深刻分化。它还影响了不同地区的经济和社会发展,其后果将持续几个世纪,并影响着欧洲历史的发展。

国有财产制度

17 世纪,东欧经历了重大的社会和经济变革,对农民的地位产生了直接影响。在乌克兰、波兰、罗马尼亚和巴尔干半岛广袤肥沃的平原上,出现了一种特殊的现象:重新实行农奴制,即所谓的 "第二次农奴制"。农奴制的复兴主要是由 "波罗的海男爵 "策划的,他们通常是在这些地区拥有大片土地的军阀或贵族。这些男爵的权力依赖于他们的军事和经济实力,他们力图最大限度地提高土地收益,以便使自己富裕起来,并为他们的政治或军事野心提供资金。农民回归农奴制意味着他们失去了自主权,生活条件回到了中世纪封建社会的水平。农民被迫在领主的土地上劳作,却无法主张土地所有权。同时,他们还必须承担苦役和版税,这削弱了他们从劳动成果中获益的能力。此外,农民往往被禁止在未经许可的情况下离开领主的土地,这就将他们与领主及其土地捆绑在一起,严重限制了他们的人身自由。这些政策的影响遍及相关地区的社会和经济结构。虽然这些土地的产量很高,对供应非洲大陆的小麦和其他谷物至关重要,但耕种这些土地的农民生活艰苦,社会地位很低。东欧奴役制的加强与同时代欧洲其他地区的大自由运动形成了鲜明对比。

东欧的领地制是一种农业组织形式,领主通常是贵族或上层贵族成员,他们建立了庞大的农业庄园。在这些庄园内,他们几乎完全控制着大量的农奴,这些农奴被捆绑在土地上,被迫为领主工作。这种制度也被称为农奴制,在沙皇俄国一直持续到 1861 年农奴解放。在这种制度下,农民被非人化地称为 "灵魂",这个词强调了他们在地主登记册上仅仅是经济单位。他们作为拥有权利和愿望的人的地位在很大程度上被忽视了。他们的生活条件一般都很悲惨:他们不拥有自己耕种的土地,被迫将大部分产品交给领主,自己只保留生存所必需的东西。因此,他们几乎没有提高产量或创新耕作技术的动力,因为任何盈余都只会增加领主的财富。这些庄园的耕作基本上是自给农作,主要目的是避免饥荒,而不是最大限度地提高产量。然而,尽管只注重生存,大庄园还是生产了大量剩余产品,尤其是小麦,出口到德国和法国等国家。这得益于广袤的土地和密集的农奴。这些大量出口的谷物使这些庄园在市场经济中扮演了近乎资本主义的角色,尽管这种制度本身是建立在封建生产关系和农奴剥削的基础上的。这一悖论凸显了欧洲前工业化经济的复杂性和矛盾性,它能够将市场经济要素与古老的社会结构相结合。

在欧洲前工业化时期的农业中,谷物是最主要的作物,垄断了多达四分之三的农田。一些历史学家将谷物,尤其是小麦的这种优势描述为 "小麦暴政"。小麦之所以至关重要,是因为它构成了人们赖以生存的食物基础:面包是人们的主食,因此种植小麦对生存至关重要。然而,尽管小麦至关重要,这片土地的产量却不尽如人意。产量普遍较低,这是原始耕作技术和缺乏技术创新的直接后果。耕作方法往往很陈旧,依靠的是几百年来都没有发展的传统知识和简陋工具。更重要的是,缺乏使耕作方式现代化和提高产量所需的投资。普遍的贫困和以物易物为基础的经济体系没有为进行此类投资所需的资本积累提供肥沃的土壤。精英阶层通过税收和租金吸收了大部分货币流,他们没有以刺激农业发展的方式重新分配财富。农民本身在经济上也没有能力采用先进技术。国家和教会施加的沉重税收负担,以及满足土地领主需求的需要,使他们几乎没有资源投资于自己的土地。因此,本可以彻底改变农业和改善农民生活条件的技术进步并没有实现,直到随后几个世纪的社会和经济动荡才改变了欧洲农业的面貌。

事实证明,土壤肥力和牲畜管理问题是限制工业化前农业发展的另一个因素。无论是动物粪便还是人类粪便,都发挥着天然肥料的重要作用,可以肥沃土壤,提高作物产量。然而,当时的粪肥供应往往不足以满足所有耕地的需要,导致农业生产率低下。放牧与谷物种植的比较凸显了一个核心难题:一公顷用于放牧的土地只能养活有限数量的牛,由此产生的肉类和奶制品也只能养活有限数量的人,而同样一公顷用于谷物种植的土地却有可能养活十倍于此的人,因为谷物可以直接生产人类食用的粮食。在粮食安全是一个重大关切问题的背景下,在大多数人口依赖谷物食品生存的情况下,理所当然要优先考虑谷物种植。然而,对谷物的偏爱却损害了轮作和畜牧业,而轮作和畜牧业本可以改善土壤条件,长期提高产量。因此,由于缺乏足够的肥料供应和保持土壤肥力的耕作方法,谷物产量一直保持在较低水平,造成了生产率低下和农村贫困的恶性循环。这充分说明了工业化前的农民所面临的制约因素以及当时自给农作所固有的困难。

在前工业时代,简陋的耕作技术和有限的土壤科学知识导致土壤养分迅速枯竭。持续耕种同一块土地而不给其恢复时间的普遍做法使土壤变得贫瘠,降低了土壤肥力,进而降低了作物产量。因此,休耕--一种让土地休息一个或多个生长季节的传统方法--成为了一种必要而非选择。在此期间,土地不被耕种,通常让野生植物生长,帮助恢复土壤中的有机物和必要养分。这是一种原始的轮作方式,可以让土壤自然再生。然而,休耕具有明显的经济弊端:它减少了任何时候可用于粮食生产的土地数量,这在人口压力和粮食需求不断增长的情况下尤其成问题。由于缺乏现代化肥和先进的土壤管理技术,农民主要依靠自然方法来保持土壤肥力,如休耕、轮作和有限使用动物粪便。直到农业革命的到来和化肥的发现,农业生产率才有了显著的飞跃,实现了连续耕作,土壤没有了必须的休耕期。

第二次农奴制 "指的是发生在中欧和东欧的一种现象,特别是在 14 世纪至 17 世纪期间,在此期间,农民的境况大大恶化,在经历了早先的相对自由时期之后,农民的境况更接近于中世纪的农奴状态。造成这种逆转的因素有很多,包括贵族的土地兼并、经济压力以及对出口农产品(尤其是谷物)日益增长的需求。农民失去自由意味着他们要服从土地和地主的意志,这往往意味着被迫劳动而得不到足够的报酬,或者报酬由地主自己确定。农民还需缴纳任意的税收和地租,没有领主的允许,他们不能离开自己的土地或将子女嫁出去。这导致了普遍的贫困化,农民无法积累资产或改善自己的命运,陷入了代代相传的贫困循环。农民的贫困化也对这些地区的社会和经济结构产生了影响,限制了经济发展,加剧了社会不稳定。直到 19 世纪进行了各种土地改革并废除了农奴制,这种状况才开始有所改变,尽管第二次农奴制的影响在这些改革之后仍持续了很长时间。

领地制度

罗马帝国衰落后,西欧从农奴制向某种形式的农民解放的过渡是一个由多种因素造成的复杂现象。随着封建结构的确立,农民和农奴发现自己处于一种僵化的社会等级制度中,但改变其地位的机会开始出现。随着中世纪经济的发展,由于财富的生产和流通发生了变化,特别是货币的使用和市场的发展,对领主来说,债役变得越来越无利可图。面对这些变化,领主们有时会发现,将土地出租给自由农民或佃户比依靠奴役制度更有利,因为自由农民或佃户需要支付地租。城镇的扩张也为农民提供了农业以外的就业机会,使他们能够更好地协商生活条件,或摆脱封建束缚,寻求更好的生活。大量农民涌入城市中心,给领主带来了压力,迫使他们改善农民的生活条件,以便将他们留在自己的土地上。农民起义和起义也影响了封建关系。这些事件有时会导致谈判,为农民提供更宽松的条件。此外,当局有时会进行立法改革,限制领主对农奴的权力,改善农奴的生活条件。在某些山区,如瓦莱州和比利牛斯山,农业社区受益于特殊的条件。这些社区通常是牧场的集体所有者,享有相对的自治权,使他们能够保持一定程度的独立性。尽管他们有义务为领主做家务,但他们是自由的,有时还能通过谈判获得对他们有利的条件。西部这些不同地区的现实见证了农民经历的多样性,也凸显了当时社会和经济结构的复杂性。农业社区适应和协商自身地位的能力是欧洲社会和经济史演变的决定性因素。

在中世纪和工业化之前的西欧,两年制和三年制轮作制度的区别反映了对当地气候条件和土壤能力的适应。这些耕作方式在农村经济和人口生存中发挥了至关重要的作用。在南欧,意大利、希腊、西班牙和葡萄牙等地区普遍采用两年轮作制。这种制度将农田分为两部分:一部分在生长季节播种,另一部分则休耕休养。这种休耕使养分得以自然更新,但意味着农田每年都无法得到充分利用。另一方面,在气候条件和土壤肥力允许的北欧,农民实行三年轮作。土地被分成三块:一块用于种植冬季作物,一块用于种植春季作物,一块用于休耕。这种方法能更好地利用土地,因为任何时候都只有三分之一的土地处于休耕状态,而两年轮作一次则只有一半的土地处于休耕状态。三年轮作的效率更高,因为它优化了土地利用,提高了农业产量。这样做的效果是增加了粮食资源的供应量,支持了更多的人口。这项技术还有助于增加牲畜数量,因为休耕地可用于放牧,而两年制则不然。在化肥和现代耕作方法出现之前,北方向三年耕作法的过渡是提高复原力和扩大人口的因素之一。这种地区差异反映了欧洲农村社会的智慧和对当时环境和经济条件的适应。

东欧和西欧之间的社会经济鸿沟并非完全是现代现象。它源于欧洲大陆悠久的历史,特别是中世纪以来的历史,几个世纪以来一直延续着农业和社会发展的鲜明特征。在东方,由于中世纪后出现了 "第二农奴制 "现象,农民的自由受到严重限制,使他们不得不受当地贵族和大地主的奴役。在这种情况下,出现了以大地主农场为特征的农业结构,农民由于不能直接从劳动成果中获益,往往没有提高产量的积极性。另一方面,在西方,虽然封建结构也很普遍,但农民逐渐获得解放,农业发展有利于提高生产力和作物多样性。三年轮作、畜牧业和轮作等做法提高了粮食产量,从而有可能养活不断增长的人口并促进城市发展。东欧和西欧之间的这种差异导致了经济和社会发展的显著不同。在西方,农业变革为工业革命奠定了基础,而东方往往保持着更为传统和僵化的农业结构,这推迟了其工业化进程,并助长了两个地区之间经济和社会不平等的长期存在。这些历史差异产生了持久的影响,这些影响在欧洲当代的政治、经济和文化动态中依然可见。

生计农业

The transition of peasants from servile status to freedom in Europe in the Middle Ages took place through a multitude of factors that often interacted with each other, and the process was far from uniform across the continent. As the population increased and towns grew, opportunities for work outside traditional agriculture began to emerge, allowing some serfs to aspire to a different life as city dwellers. Changes in farming practices, rising productivity and the beginnings of capitalism with its expanding trade required a freer and more mobile workforce, helping to challenge the traditional servile system. The serfs, for their part, did not always accept their fate unchallenged. Peasant revolts, although often crushed, could sometimes lead to concessions from the nobility. At the same time, certain regions saw legislative reforms that abolished servitude or improved the condition of peasants, under the influence of various factors ranging from economics to ethics. Paradoxically, crises such as the Black Death also played a role in this transformation. The mass death of the population created a labour shortage, giving the surviving peasants greater leeway to negotiate their status and wages. However, despite these advances towards freedom, in the 18th century, while the majority of peasants in Western Europe were free in their own right, their economic freedom often remained limited. Systems of land tenure still required them to pay rents or provide services in exchange for access to land. This was in stark contrast to many parts of Eastern Europe, where servitude persisted, even intensifying in some cases, before finally being abolished in the nineteenth century. The emancipation of Western peasants did not mean, however, that they achieved social equality or total economic independence. Power structures and land ownership remained highly unequal, keeping a large proportion of the rural population in a state of economic dependence, even though their legal status had changed.

In the pre-industrial era, agriculture was the basis of survival for the vast majority of Europeans. This agriculture was strongly oriented towards cereal production, with wheat and barley being the main crops. Peasants produced what they consumed, working essentially to feed their families and to ensure a bare minimum for survival. Cereals were so important that they accounted for three quarters of their diet, hence the expression "tyranny of the wheat", which illustrates the dependence on these crops. At that time, an individual consumed between 800 grams and 1 kilogram of cereals every day, compared with only 150 to 200 grams in modern societies. This high consumption reflects the importance of cereals as a main source of calories. Cereals were preferred to livestock because they were around ten times more productive in terms of food produced per hectare. Cereals could feed a large population, whereas livestock farming required vast tracts of land for a much lower yield in terms of human calories. However, this type of agriculture was characterised by low yields and great vulnerability to crop failure. In the Middle Ages, sowing one grain could yield an average of five to six grains at harvest time. In addition, part of this harvest had to be set aside for future sowing, which meant a lean period when food reserves dwindled before the new harvest. This period was particularly critical, and famines were not uncommon when harvests were insufficient. As a result, the population lived constantly on a knife-edge, with little margin to cope with climatic hazards or epidemics that could decimate the crops and, consequently, the population itself.

Medieval farming techniques were limited by the technology of the time. Iron production was insufficient and expensive, which had a direct impact on agricultural tools. Ploughshares were often made of wood, a much less durable and efficient material than iron. A wooden ploughshare wore out quickly, reducing the efficiency of ploughing and limiting farmers' ability to cultivate the land effectively. The vicious circle of poverty exacerbated these technical difficulties. After the harvest, farmers had to sell much of their grain for flour and pay various taxes and debts, leaving them with little money to invest in better tools. The lack of money to buy an iron ploughshare, for example, prevented improvements in agricultural productivity. Better equipment would have enabled the land to be cultivated more deeply and more efficiently, potentially increasing yields. Moreover, reliance on inefficient tools limited not only the amount of land that could be cultivated, but also the speed at which it could be cultivated. This meant that even if agricultural knowledge or climatic conditions allowed for better production, material limitations placed a ceiling on what the agricultural techniques of the time could achieve.

Soil fertilisation was a central issue in pre-industrial agriculture. Without the use of modern, effective chemical fertilisers, farmers had to rely on animal and human excrement to maintain the fertility of arable land. The Île-de-France region is a classic example where dense urbanisation, as in Paris, could provide substantial quantities of organic matter which, once processed, could be used as fertiliser for the surrounding farmland. However, these practices were limited by the logistics of the time. The concentration of livestock farming in mountainous regions was partly due to the geographical characteristics that made these areas less suitable for intensive cereal farming but more suited to grazing due to their poor soil and rugged terrain. The Alps, Pyrenees and Massif Central are examples of such areas in France. Transporting manure over long distances was prohibitively expensive and difficult. Without a modern transport system, moving large quantities of something as heavy and bulky as manure represented a major logistical challenge. The "tyranny of cereals" refers to the priority given to growing cereals to the detriment of livestock farming, and this prioritisation had consequences for soil fertility management. Where livestock farming was practised, manure could be used to fertilise the soil locally, but this did not benefit remote cereal-growing regions, which needed it badly to increase crop yields. Managing soil fertility was complex and was subject to the constraints of the agrarian economy of the time. Without the means to transport fertiliser efficiently or the existence of chemical alternatives, maintaining soil fertility remained a constant challenge for pre-industrial farmers.

Low cereal yields

Yields remain low

Agricultural yield is the ratio between the quantity of product harvested and the quantity sown, generally expressed in terms of grain harvested for each grain sown. In pre-industrial agricultural societies, low yields could have disastrous consequences. Poor harvests were often caused by adverse weather conditions, pests, crop diseases or inadequate farming techniques. When the harvest failed, the people who depended on it for their livelihood faced food shortages. Famine could result, with devastating effects. The "law of the strongest" can be interpreted in several ways. On the one hand, it can mean that the most vulnerable members of society - the young, the old, the sick and the poor - were often the first to suffer in times of famine. On the other hand, in social and political terms, it could mean that the elites, with better resources and more power, were able to monopolise the remaining resources, thereby reinforcing existing power structures and accentuating social inequalities. Famine and chronic malnutrition were drivers of high mortality in pre-industrial societies, and the struggle for food security was a constant in the lives of most peasants. This led to various adaptations, such as food storage, diversified diets and, over time, technological and agricultural innovation to increase yields and reduce the risk of famine.

Agricultural yields in the Middle Ages were significantly lower than those that modern agriculture has managed to achieve thanks to technological advances and improved cultivation methods. Yields of 5-6 to 1 are considered typical for certain European regions during this period, although these figures can vary considerably depending on local conditions, cultivation methods, soil fertility and climate. The case of Geneva, with a yield of 4:1, is a good illustration of these regional variations. It is important to remember that yields were limited not only by the technology and agricultural knowledge of the time, but also by climatic variability, pests, plant diseases and soil quality. Medieval agriculture relied on systems such as three-year crop rotation, which improved yields somewhat compared with even earlier methods, but productivity remained low by modern standards. Farmers also had to save part of their harvest for sowing the following year, which limited the amount of food available for immediate consumption.

Reasons for poor performance

The "tyranny of cereals" characterises the major constraints of pre-industrial agriculture. Soil fertility, crucial for good harvests, depended heavily on animal manure and human waste, in the absence of chemical fertilisers. This dependence posed a particular problem in mountainous areas, where the remoteness of livestock farms limited access to this natural fertiliser, reducing crop yields. The cost and logistics of transport, at a time when there were no modern means of transport, made the transfer of goods such as manure, essential for fertilising fields, both costly and impractical over long distances. The farming methods of the time, with their rudimentary tools and poorly-developed ploughing and sowing techniques, did nothing to improve the situation. Wooden ploughs, less efficient than their metal counterparts, were unable to exploit the full potential of cultivated land. What's more, the diet of the time was dominated by the consumption of cereals, seen as a reliable and storable source of calories for times of shortage, particularly in winter. This focus on cereals hindered the development of other forms of agriculture, such as horticulture or agroforestry, which could have proved more productive. The social and economic structure of the feudal system only exacerbated these difficulties. Peasants, weighed down by the weight of royalties and taxes, had little means or incentive to invest in improving their farming practices. And when the weather turned out to be unfavourable, harvests could be seriously affected, as medieval societies had few strategies for managing the risks associated with climatic hazards. In such a context, agricultural production focused more on survival than on profit or the accumulation of wealth, limiting the possibilities for the evolution and development of agriculture.

The low level of investment in pre-industrial agriculture is a phenomenon rooted in several structural aspects of the period. Farmers were often hampered by a lack of financial resources to improve the quality of their tools and farming methods. This lack of capital was exacerbated by an oppressive tax system that left peasants little room to accumulate savings. The tax burden imposed by the nobility and feudal authorities meant that most harvests and income went towards meeting the various taxes and levies, rather than being reinvested in the farm. What's more, the socio-economic system was not conducive to capital accumulation, as it was structured in such a way as to keep peasants in a position of economic dependence. Such was the precariousness of the peasants' situation that they often had to concentrate on satisfying immediate survival needs, rather than on long-term investments that could have improved yields and living conditions. This lack of means for investment was reinforced by the lack of access to credit and an aversion to risk justified by the frequency of natural hazards, such as bad weather or plagues like locust infestations and plant diseases, which could wipe out harvests and, with them, the investments made.

The stereotype of the conservative peasant has its roots in the material and socio-economic conditions of pre-industrial societies. In these societies, subsistence farming was the norm: it aimed to produce enough to feed the farmer and his family, with little surplus for trade or investment. This mode of production was closely linked to natural rhythms and traditional knowledge, which had proved its worth over generations. Farmers depended heavily on the first harvest to see them through to the next. So any change in farming methods represented a considerable risk. If they failed, the consequences could be disastrous, ranging from famine to starvation. As a result, deviating from tried and tested practices was not only seen as imprudent, it was a direct threat to survival. Resistance to change was therefore not simply a question of mentality or attitude, but a rational reaction to conditions of uncertainty. Innovation meant risking upsetting a fragile balance, and when the margin between survival and starvation is thin, caution takes precedence over experimentation. Farmers could not afford the luxury of mistakes: they were the managers of a system in which every grain, every animal and every tool was of vital importance. Moreover, this caution was reinforced by social and economic structures that discouraged risk-taking. Opportunities for diversification were limited, and social support systems or insurance against crop failure were virtually non-existent. Farmers often had debts or obligations to landowners or the state, forcing them to produce safely and constantly to meet these commitments. The stereotype of the conservative peasant is therefore part of a reality where change was synonymous with danger, and where adherence to tradition was a survival strategy, dictated by the vagaries of the environment and the imperatives of a precarious life.

Maintaining soil fertility was a constant challenge for medieval farmers. Their dependence on natural fertilisers such as animal and human dung underlines the importance of local nutrient loops in agriculture at the time. The concentration of population in urban centres such as Paris created abundant sources of organic matter which, when used as fertiliser, could significantly improve the fertility of the surrounding soils. This partly explains why regions such as the Île-de-France were renowned for their fertile soil. However, the agricultural structure of the time meant that there was a geographical separation between livestock farming and cereal-growing areas. Livestock farms were often located in mountainous areas with less fertile soils, where the land was unsuitable for intensive cereal growing but could support grazing. Grazing areas such as the Pyrenees, the Alps and the Massif Central were therefore far from cereal-growing regions. Transporting the fertiliser was therefore problematic, both in terms of distance and cost. Transport techniques were rudimentary and costly, and infrastructure such as roads was often in poor condition, making the movement of bulky materials such as manure economically unviable. As a result, cereal fields often lacked the nutrients they needed to maintain or improve their fertility. This situation created a vicious circle in which the land was depleted faster than it could be regenerated naturally, leading to lower yields and increased pressure on farmers to feed a growing population.

The perception of gridlock in medieval agricultural societies stems in part from the economic structure of the time, which was predominantly rural and based on agriculture. Agricultural yields were generally low, and technological innovation slow by modern standards. This was due to a number of factors, including a lack of advanced scientific knowledge, few farming tools and techniques available, and a certain resistance to change due to the risks associated with trying out new methods. In this context, the urban class was often perceived as an additional burden for farmers. Although urban dwellers depended on agricultural production for their survival, they were also often seen as parasites in the sense that they consumed surpluses without contributing directly to the production of these resources. The townsfolk, who included merchants, craftsmen, clerics and the nobility, were dependent on the peasants for their food, but did not always share the burdens and benefits of agricultural production equally. The result was an economic system where the peasants, who formed the majority of the population, worked hard to produce enough food for everyone, but saw a significant proportion of their harvest consumed by those not involved in production. This could create social and economic tensions, especially in years of poor harvests when surpluses were limited. This dynamic was exacerbated by the feudal system, where land was held by the nobility, who often imposed taxes and drudgery on the peasants. This further limited peasants' ability to invest in improvements and accumulate surpluses, maintaining the status quo and hindering economic and technological progress.

The law of 15% by Paul Bairoch

Societies under the Ancien Régime had very strict economic constraints linked to their agricultural base. The ability to support a non-farming population, such as that living in cities, was directly dependent on agricultural productivity. Since agricultural techniques of the time severely limited yields, only a small fraction of the population could afford not to participate directly in food production. The statistics illustrate this dependence. If 75% to 80% of the population had to work in agriculture to meet the food needs of the entire population, this left only 20% to 25% of the population for other tasks, including vital functions within society such as trade, crafts, the clergy, administration and education. In this context, urban dwellers, who represented around 15% of the population, were perceived as 'parasites' in the sense that they consumed resources without contributing directly to their production. However, this perception overlooks the cultural, administrative, educational and economic contribution that these city dwellers made. Their work was essential to the structuring and functioning of society as a whole, although their dependence on agricultural production was an undeniable reality. The activities of city dwellers, including those of craftsmen and tradesmen, did not cease with the seasons, unlike those of peasants, who were less active in winter. This reinforced the image of city dwellers as members of society who lived at the expense of the direct producers, the peasants, whose labour was subject to the vagaries of the seasons and the productivity of the land.

The law of 15% formulated by the historian Paul Bairoch illustrates the demographic and economic limitations of agricultural societies before the industrial era. This law stipulates that a maximum of 15% of the total population could be made up of city dwellers, i.e. people who did not produce their own food and were therefore dependent on agricultural surpluses. During the Ancien Régime, the vast majority of the population - between 75 and 80% - was actively engaged in agriculture. This high proportion reflects the need for an abundant workforce to meet the population's food requirements. However, as farming was a seasonal activity, farmers did not work during the winter, which meant that in terms of the annual workforce, it was estimated that 70-75% was actually invested in agriculture. Based on these figures, this would leave 25 to 30% of the workforce available for activities other than farming. However, it is important to bear in mind that even in rural areas there were non-farm workers, such as blacksmiths, carpenters, priests and so on. Their presence in the countryside reduced the amount of labour that could be allocated to the towns. Taking all these factors into account, Bairoch concluded that the urban population, i.e. those living from non-agricultural activities in the towns, could not exceed 15% of the total. This limit was imposed by the productive capacity of agriculture at the time and the need to provide food for the entire population. As a result, pre-industrial societies were predominantly rural, with urban centres remaining relatively modest in relation to the overall population. This reality underlines the precarious balance on which these societies were based, as they could not support a growing number of city-dwellers without risking their food security.

The concept evoked by Paul Bairoch in his book "From Jericho to Mexico" highlights the link between agriculture and urbanisation in pre-industrial societies. The estimate that urbanisation rates remained below 15% until the Industrial Revolution is based on a historical analysis of available demographic data. Although the adjustment of 3 to 4 may seem arbitrary, it serves to reflect the margin needed for activities other than agriculture, even taking into account craftsmen and other non-agricultural occupations in rural areas. This urbanisation limit was indicative of a society where most resources were devoted to survival, leaving little room for investment in innovations that could have boosted the economy and increased agricultural productivity. Cities, historically the centres of innovation and progress, were unable to grow beyond this 15% threshold because agricultural capacity was insufficient to feed a larger urban population. However, this dynamic began to change with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Technological innovations, particularly in agriculture and transport, led to a spectacular increase in agricultural yields and a reduction in transport costs. These developments freed part of the population from the need for agricultural labour, allowing for increased urbanisation and the emergence of a more economically diverse society, where innovation could flourish in an urban environment. In other words, while the societies of the Ancien Régime were confined to a certain stasis due to their agricultural limitations, technological progress gradually unlocked the potential for innovation and paved the way for the modern era.

Societies of mass poverty

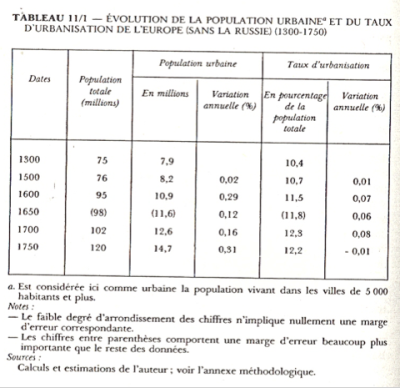

This table provides an overview of the demographic and urbanisation progression in Europe between 1300 and 1750. During this period, the European population grew from 75 million to 120 million, reflecting gradual demographic growth despite historical hazards such as the Black Death, which greatly reduced the population in the 14th century. There has also been a trend towards urbanisation, with the number of people living in cities rising from 7.9 to 14.7 million. This urbanisation is slow, however, and does not reflect large-scale migration to cities, but rather their constant development. The percentage of the population living in urban areas remains below 15%, reinforcing the idea of a pre-industrial, mainly agricultural society. The annual variation in the rate of urbanisation and in the total population is fairly small, indicating gradual demographic changes rather than rapid or radical transformations. This suggests that demographic change and urbanisation in Europe were the result of slow and stable evolutions, marked by a gradual development of urban infrastructures and a growing, albeit modest, capacity of cities to support a larger population. In short, these data depict a Europe that is slowly moving towards a more urbanised society, but whose roots remain deeply rooted in agriculture, with cities serving more as commercial and administrative centres than industrial production hubs.

Living conditions in pre-industrial agricultural societies were extremely harsh and could have a significant impact on people's health and longevity. Subsistence farming, intense physical labour, limited diets, poor hygiene and limited access to medical care contributed to high infant mortality and low life expectancy. An average life expectancy of around 25 to 30 years does not mean, however, that most people died at that age. This figure is an average influenced by the very large number of deaths of infants. Children who survived childhood had a reasonable chance of reaching adulthood and living to 50 or more, although this was less common than it is today. An individual reaching 40 was certainly considered older than by today's standards, but not necessarily an 'old man'. However, the wear and tear on the body due to strenuous manual labour from an early age could certainly give the appearance and aches associated with early old age. People often suffered from dental problems, chronic illnesses and general wear and tear on the body that made them look older than a person of the same age would today, with access to better healthcare and a more varied diet. Epidemics, famines and wars exacerbated this situation, further reducing the prospects of a long and healthy life. This is why the farming population of the time, faced with a precarious existence, often had to rely on community solidarity to survive in such an unforgiving environment.

Malnutrition was a common reality for farmers in pre-industrial societies. The lack of dietary diversity, with a diet often centred on one or two staple cereals such as wheat, rye or barley, and insufficient consumption of fruit, vegetables and proteins, greatly affected their immune systems. Deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals could lead to various deficiency diseases and weaken resistance to infection. Farmers, who often lived in precarious hygiene conditions and in close proximity to animals, were also exposed to a variety of pathogens. A 'simple' flu, in such a context, could prove far more dangerous than in a well-nourished and healthy population. Lack of medical knowledge and limited access to healthcare exacerbated the situation. These populations were also confronted with periods of famine, due to insufficient harvests or natural disasters, which further reduced their ability to feed themselves properly. In times of famine, opportunistic diseases could spread rapidly, transforming benign ailments into fatal epidemics. In addition, periods of war and requisitioning could worsen the food situation of peasants, making malnutrition even more frequent and severe.

In 1588, the Roman Gazette ran the headline "À Rome rien de neuf sinon que l'on meurt-de-faim" (Nothing new in Rome except that people were dying of hunger) while the Pope was giving a banquet. These were societies of mass poverty reflected in a precarious situation. There is a striking contrast between the social classes in pre-industrial societies. By reporting on the famine in Rome at the same time as a papal banquet, the Roman Gazette highlights not only social inequality but also the indifference or powerlessness of the elites in the face of the suffering of the most disadvantaged. Mass poverty was a feature of Ancien Régime societies, where the vast majority of the population lived in constant precariousness. Subsistence depended entirely on agricultural production, which was subject to the vagaries of weather, pests, crop disease and war. A poor harvest could quickly lead to famine, exacerbating poverty and mortality. The elites, be they ecclesiastics, nobles or bourgeois in the towns, had far greater means at their disposal and were often able to escape the most serious consequences of famines and economic crises. Banquets and other displays of wealth in times of famine were seen as signs of opulence out of touch with the realities of the people. This social divide was one of the many reasons that could lead to tensions and popular uprisings. History is punctuated by revolts in which hunger and misery drove people to rise up against an order deemed unjust and insensitive to their suffering.