The implementation of a law

| Professeur(s) | Victor Monnier[1][2][3][4][5][6] |

|---|---|

| Cours | Introduction au droit |

Lectures

- Définition du droit

- L’État

- Les différentes branches du droit

- Les sources du droit

- Les grandes traditions formatrices du droit

- Les éléments de la relation juridique

- L’application du droit

- La mise en œuvre d’une loi

- L’évolution de la Suisse des origines au XXème siècle

- Le cadre juridique interne de la Suisse

- La structure d’État, le régime politique et la neutralité de la Suisse

- L’évolution des relations internationales de la fin du XIXe au milieu du XXe siècle

- Les organisations universelles

- Les organisations européennes et leurs relations avec la Suisse

- Les catégories et les générations de droits fondamentaux

- Les origines des droits fondamentaux

- Les déclarations des droits de la fin du XVIIIe siècle

- Vers l’édification d’une conception universelle des droits fondamentaux au XXe siècle

Action and jurisdiction

The law is only applicable if it can be enforced. To do this, the action / jurisdiction pair intervenes.

Action: The field of law enforcement is defined as the legal process designed to ensure the sanction of the law with the help of the courts. The right only exists if the holder of a right has the possibility to enforce it with the assistance of the State or other authorities.

Jurisdiction: It is the activity of the State that determines the right extended to the bodies established to exercise the mission of judging and rendering justice, by application of law. These services are entrusted to the judiciary in order to resolve conflicts.

Thus, the legal system allows a general right of action; any subjective right allows action to be taken before State bodies to enforce or establish its existence.

Actions may be civil, criminal or administrative.

Alternative modes of conflict rules

There is the possibility of applying to the court, but there are also courts other than those of the State. However, this does not affect the State judge.

It can only be used with the authorization of the State, it affects private law, public law and international law.

Negotiations and "talks"

Negotiation is a mode used in the field of public international law. The two parties in conflict discuss with a view to resolving the differences between them.

During negotiations, there may be the intervention of a third party who makes himself available to the parties (good offices). It does not participate directly, but through the means it makes available to the parties it promotes discussions.

Good offices" allow a third country to act as an intermediary allowing the parties to negotiate under optimal conditions; the parties are free to negotiate.

In some crises, Switzerland has played the role of "good offices", particularly with Cuba.

Mediation

Mediation consists in relying on a mediator chosen according to the prestige he or she exercises. It proposes a solution, but does not impose it on the parties to the conflict who have the choice of accepting or rejecting it.

Generally, mediation concerns both private law (labour disputes, family disputes) and international law.

Conciliation

Conciliation consists in bringing the parties in conflict closer together to find an amicable solution. The term amicable comes from the Latin word "amicabilis" which belongs only to the legal vocabulary.

Conciliation refers to a negotiated solution that cannot be strictly limited to the law, the judge does not decide, but seeks to reach an agreement

This is often the first step that a judge in a dispute can or should take (for example, family law). However, acceptance is always the will of the parties.

The arbitration

Arbitration is the submission of a dispute to one or more arbitrators chosen by the parties that results in a binding decision. Unlike the court, you can choose your judge.

Arbitration may be agreed prior to the recognition of a dispute under the arbitration clause that if there is a dispute, it is anticipated that the dispute will be resolved by arbitration.

Arbitration can be conducted ad hoc, i.e. it is applied to a special case after a dispute has arisen, so the parties agree to settle their dispute through alternative arbitration.

An arbitral agreement is an agreement at the time of the dispute, decided by arbitration.

Nowadays, arbitration is a widely used method in international law. On the other hand, arbitration has found a preferred field in the life of large companies (simpler, more efficient, faster, more discreet procedure). In the field of commercial business, 80% of international commercial contracts contain an arbitration clause. It is the European Chambers of Commerce that have organised arbitration courts.

Unlike judges, arbitrators have extensive practical experience, particularly in commercial cases.

The parties shall choose the arbitrators competent in the areas where there are conflicts.

Alabama Arbitration: September 15, 1872, Great Britain was ordered to pay the United States a very heavy compensation for failing to comply with its obligations of strict neutrality in the Civil War. Guilty of negligence in tolerating the delivery to the southerners of some twenty boats. Will contribute to the international base in Geneva.

The parties to the trial

The trial can oppose two parties, this is particularly the case of the civil trial:

- PLAINTIFF is the one who has initiated a trial

- DEFENDER is the person against whom a legal claim is made

The mission of repression is over at the State. Criminal proceedings are a little different, because their mission is to repair, it is the State that takes care of them. This action is automatically initiated by the public prosecutor on his or her own initiative or by a public official.

The Public Prosecutor's Office refers to all magistrates who are responsible for representing the law and the interests of the State before the courts.

- In the cantons: the public prosecutor's office is headed by a public prosecutor elected by the people in charge of criminal proceedings.

- In the Confederation: the Public Prosecutor's Office is headed by the Attorney General of the Confederation, who is elected by the Federal Assembly.

The action is automatically triggered, the public prosecutor does not need to be requested in advance to be implemented.

The criminal procedure

The rules of law triggered by criminal procedure are totally mandatory, they are rules of law that have a strict form. This ensures the security of the accused's right to be charged. For example, a search must follow strict rules in order to defend the interests of the accused.

The adversarial and inquisitorial proceedings

Criminal procedure, also known as criminal investigation, is the search for and taking of evidence relating to a crime or misdemeanour.

Accusatory

This is the oldest procedure, it takes its name from the fact that criminal proceedings are initiated by a charge, it takes the form of a fight organised in solemn forms between the plaintiff and the defendant, which is arbitrated by a judge in order to put an end to this simulated fight by giving reason to one or the other party. It is the expression of political regimes with high citizen participation.

The prosecution is indicted, the judge is an arbitrator. He ensures that the fight between the two parties goes well and he must decide on the evidence he receives.

This procedure is:

- oral;

- public;

- contradictory.

It takes into consideration both parties without taking any initiative. Since the procedure is public, the citizen can check that it is running smoothly.

The prosecution and investigation of offences is left to the private sector, as the prosecution's resources are insufficient. There is a lack of evidence because the judge cannot intervene directly. As a result, the interests of the accused are somewhat harmed.

On the other hand, there is a lack of investigation: Investigation, the phase of the criminal trial during which the investigating magistrate carries out investigations aimed at identifying the perpetrator of the offence, clarifying his personality, establishing the circumstances and consequences of this offence, in order to decide on the action to be taken in public proceedings. This procedure exists mainly in the United States.

Procedural law deals with the resolution of conflicts and offences that harm a community (Crime). In his Germania, Tacitus talks about the existence of courts to settle disputes; the principles, elected, were required to include people of the people.

According to the Salian Franks code (around 500), the judge directed the entire procedure, from the summons to execution, while the proposed sentence belonged to the "rachimburg", i. e. seven men chosen as judges from the injured community, and had to be approved by the Thing, i. e. all men entitled to bear arms (Barbarian laws). According to the Alaman law (lex Alamannorum, circa 720), the judge had to be appointed by the Duke and approved by the people. The Carolingian judicial reform (circa 770) deferred the ability to pass judgment to aldermen, permanent judges, and the sentence no longer had to be approved by the Thing. The procedural subdivision into low justice (causae minores) and high justice or criminal justice (causae majores) is at the origin of the distinction between civil procedure and criminal procedure (Criminal Law).

Inquisitory

This procedure originates in ecclesiastical jurisdictions and canon law. It became widespread in the 13th century and then spread to most secular jurisdictions.

This system meets the needs of an authoritarian regime that places the interests of society above the individual.

This procedure takes its name from an initial formality that designates the subsequent conduct of a trial procedure and weighs on the investigation, the inquisitio. The investigation determines the conduct of the trial. It is the magistrate who carries out this investigation and it begins ex officio, i.e. at the initiative of the magistrate or a public official. On the other hand, the magistrate leads the debates.

The magistrate's power of investigation is not limited to the parties' conclusions and is secret, written and non-adversarial.

With the investigation entrusted to judges, few guilty parties escape punishment. On the other hand, the disadvantages are that the defenseless nature of the accused leads to the conviction of innocent people. From a technical point of view, the inquisitorial procedure is too long, its written nature resulting in a complete dehumanization of the criminal trial.

With this instruction, the accused has little chance of getting away with it and the hearing of the judgment is only pure finality, because the instruction occupies most of the time.

Most European countries in the second millennium switched from one system to another. With the Age of Enlightenment and the resolutions, there has been a certain upheaval. From the 19th century onwards, there was a change in the system: the best elements of both procedures were used to create a criminal procedure that took both aspects into account.

Two major criminal proceedings:

- Preliminary phase: inquisitorial type (secret, written and non-adversarial), it includes police investigation and investigation;

- Decisive phase: adversarial, trial and judgment.

From the Enlightenment onwards, there was a mixed system that took the advantages of the inquisitorial and accusatory type for the decisive phase.

Principles governing criminal procedure

The substantive rules and criminal procedure are subject to the principle of legality.

Principle of legality

The principle of legality requires that the administration acts only within the framework set by law. On the one hand, the administration must respect, in all its activities, all the legal provisions that govern it, as well as the hierarchy of these provisions: this is the principle of the primacy - or, in more traditional terminology, the supremacy - of the law. On the other hand, the administration can only act if the law allows it to do so; in other words, any action by the administration must have a basis in a law: this is the principle of the requirement of the legal basis.

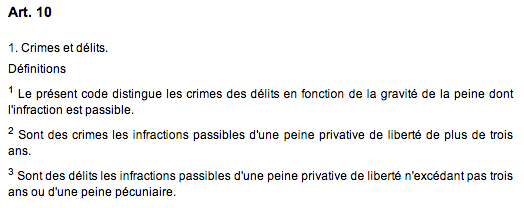

The law is the only source of the Criminal Code, it alone defines the offences and penalties applicable to it.

This principle of legality has three consequences:

- nullum crimen sine lege: no crime without law;

- nulla poena sine lege: no punishment without law;

- nulla poena sine crimine: no punishment without a crime.

These consequences imply that the rules of procedure must find their sources in the law and they must be in conformity with the law.

The rule of legality is a constitutional principle:

- principle of the supremacy of the law to be applied by all;

- requirement of the legal basis: any activity of the State must be based and based on the law;

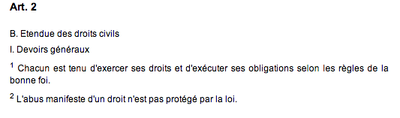

- the rules of procedure must be applied in accordance with the principle of good faith.

The procedure must not become an end in itself, as it risks supplanting justice. Therefore, the agents who apply the procedure must not go against the principle of good faith.

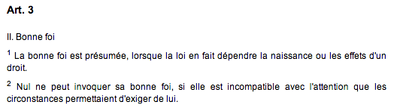

Principle of good faith

The principle of good faith (good faith in the objective sense) is the principle that obliges the State and individuals to behave honestly and fairly in their legal relations (see art. 5 para. 3 Cst. ; art. 2 para. 1 CC). Good faith in the objective sense must be distinguished from good faith in the subjective sense (Art. 3 CC), which refers to the fact that a person ignores a legal defect affecting a specific factual situation.

The law must harmoniously combine the interests of individuals and the interests of society. It is therefore important that procedural provisions are neither too strict for the accused nor overly formal. The defence must express itself freely and it is the criminal procedure that indicates this without, however, jeopardizing the task of the State and the task of repression.

On the other hand, criminal procedure is driven and determined by a set of principles that impose certain fundamental duties on criminal authorities.

These principles generally derive from the federal constitution, but also from international treaties such as, for example, the Convention on Human Rights or the UN covenants on the subject.

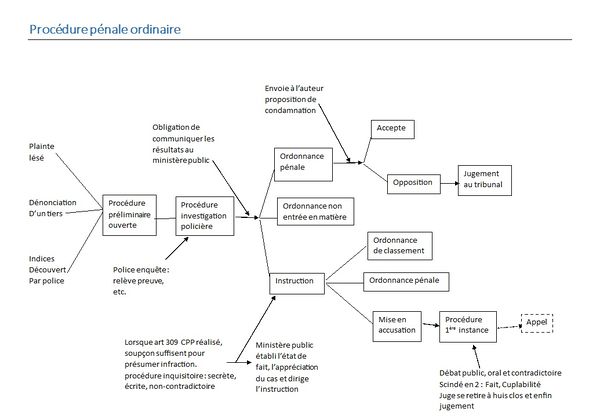

The stages of the criminal procedure

On 1 January 2011, criminal proceedings were transferred to the federal state. This event is marked by the entry into force of the Civil Procedure Codes and Criminal Procedure Codes.

It was the people and the cantons that amended the constitution in March 2000 by transferring criminal jurisdiction to the confederation. The Federal State has exercised it by introducing a law on civil procedure and a law on criminal procedure.

Civil proceedings are characterized by two phases:

PHASE 1: Preliminary

- Investigation (police investigation)

- Instruction

The cantonal public prosecutor's office conducts investigations, investigates and prepares the indictment before the court. Thus, the indictment, investigation and prosecution are the sole responsibility of the public prosecutor. This body will make criminal prosecution very effective.

The Public Prosecutor's Office refers to all magistrates who are responsible for representing the law and the interests of the State before the courts.

Investigation, the phase of the criminal proceedings during which the investigating magistrate carries out investigations aimed at identifying the perpetrator of the offence, clarifying his personality, establishing the circumstances and consequences of this offence, in order to decide on the action to be taken in public proceedings.

Investigation following a denunciation the authorities will proceed to an investigation. On the basis of the investigations, the Public Prosecutor's Office will determine whether an investigation should be opened: an investigation is opened when there are sufficient grounds for suspecting that an offence has indeed been committed.

Opening of the investigation

In light of the evidence, the Crown will make the decision to charge the accused.

PHASE 2: Decisory

The transmission of the indictment triggers the decisive phase. The public prosecutor becomes a simple part of the accusation: public accuser. The president of the court is the one who directs the procedure.

First step: the examination of the charge (inquisitorial principle)

- le ministère public fait passer au tribunal l’acte d’accusation

- le tribunal vérifie si l’acte d’accusation a été élaboré régulièrement

- si le comportement dénoncé dans un acte d’accusation est punissable, s’il existe des soupçons suffisants permettant d’étayer un acte d’accusation alors le juge va initier le procès

- le président prépare les débats, met les dossiers en circulation, fixe la date du procès et convoque les personnes dans le cadre de l’affaire

Deuxième étape : le débat devant le tribunal (principe accusatoire)

La procédure est accusatoire publique, orale. Le juge est l’acteur de cette phase, mais il est aussi arbitre.

Les débats suivent une procédure précise :

- début : acte d’accusation

- procédure probatoire

- auditions des témoins, prévenus, experts

- examen des preuves

- plaidoiries : le ministère public commence suivit par la partie plaignante, un second tour de plaidoirie peut être demandé

- le dernier mot revient toujours au prévenu

Troisième étape : jugement Le tribunal se retire à huis clos afin d’établir le jugement

- La délibération est d’abord orale puis écrite

- comporte plusieurs questions :

- le prévenu est-il coupable ou non ? (art. 351 Code de procédure pénale) : le tribunal doit trancher en faveur de l’accusé (in dubio proreo : le doute profite à l’accusé)

- la sanction : fixation de la peine dans les limites légales en fonction des faits dont le prévenu a été déclaré coupable

- les intérêts civils : lorsque le lésé réclame des dommages et intérêts, le tribunal doit se prononcer sur les dommages et intérêts

La justice des mineurs

Les modèles régissant la justice des mineurs

On distingue trois grands modèles :

- le modèle punitif (dans les pays anglo-saxons)

- le modèle protecteur (Brésil, Portugal, Espagne)

- le modèle intermédiaire (Suisse)

Le modèle punitif ne fait pas de grandes différences avec la justice adulte. Dans ce système répressif, le mineur est frappé de lourdes sanctions et est placé dans des institutions fermées. Le juge ne s’occupe pas de protéger le délinquant mineur. L’objectif est de privilégier la protection de la société, sans se soucier de la protection du mineur. → 80% de récidive

Dans le modèle protecteur, le juge va chercher à comprendre pourquoi le délinquant mineur a dérapé. Ce délinquant mineur est considéré comme une victime et a donc besoin d’être soigné et encadré. Le juge dispose d’une très grande marge d’appréciation. Ce modèle protecteur se désintéresse de la victime du délinquant mineur et privilégie la réinsertion de ce dernier.

Le modèle intermédiaire se situe entre les deux modèles précédents. Bien que se souciant de la protection de la société, ce modèle garde comme objectif premier l’éducation du délinquant mineur. Ainsi, le juge n’a pas à répondre par une seule et unique sanction à un délit commis par un mineur, mais il dispose de tout un éventail de mesures. → 35% à 45% de récidive

Le modèle du procureur des mineurs et le modèle du juge des mineurs

Le modèle du procureur des mineurs, qu’on retrouve dans la majorité des cantons alémaniques, prévoit qu’un magistrat mène l’enquête, tranche les cas les moins importants par une ordonnance pénale qui classe l’affaire (art. 32 de la procédure pénale pour les mineurs) et dans les autres cas, rédige lui-même l’acte d’accusation avant de le transmettre au tribunal des mineurs. Ce magistrat ne siège pas lui-même au sein du tribunal, il ne fait que soutenir l’accusation (partie accusatoire), mais il s’occupe aussi de l’après-jugement.

Le modèle du juge des mineurs, qu’on retrouve dans les cantons latins, prévoit que c’est le même juge qui mène et l’enquête, tranchent les cas les moins importants par une ordonnance pénale qui classe l’affaire (art. 32 de la procédure pénale pour les mineurs) et grande différence avec le modèle du procureur des mineurs, siège au sein du tribunal et donc participe pleinement au jugement du mineur. Ce modèle est à l’avantage du délinquant mineur, car le juge le connait personnellement.

Le système des peines et la médiation

Lorsqu’il retient que des infractions ont été commises, le tribunal pénal des mineurs peut prendre les décisions suivantes : ordonner des mesures de protection, exempter le mineur de peine ou alors prononcer une peine.

- Les mesures de protection (surveillance, assistance personnelle…) sont prévues à l’article 10 de la loi fédérale régissant la condition pénale des mineurs et ont pour but de protéger le délinquant mineur, qu’il soit coupable ou non.

- Selon l’article 21 de la loi fédérale régissant la condition pénale des mineurs, le tribunal peut renoncer à prononcer une peine si cette peine risque de compromettre l’objectif visé par une mesure de protection déjà ordonnée.

- La peine prononcée par le tribunal pénal des mineurs peut s’échelonner de la réprimande, à la prestation personnelle, ou à l’amende et dans les cas extrêmes à la privation de liberté.

Dans ce cadre-là et selon l’article 16 de la loi de procédure pénale pour les mineurs, l’autorité d’instruction et le tribunal des mineurs peuvent tenter d’aboutir à une conciliation entre le lésé et le prévenu mineur lorsque la procédure porte sur une infraction poursuivie sur plainte (par exemple les dommages à la propriété, tels des graffitis). Si cette conciliation aboutit alors la procédure est classée.

L’article 17 prévoit lui la médiation : l’autorité d’instruction et les tribunaux peuvent en tout temps suspendre la procédure et charger une personne compétente dans le domaine de la médiation d’engager une procédure de médiation. Le médiateur ou la médiatrice est une personne indépendante de la justice. Si, grâce à la médiation, un accord intervient entre le prévenu mineur et le lésé, on renonce à toute poursuite pénale et la procédure est classée (article 5).

La médiation permet de montrer au mineur que son acte est une infraction qui viole la loi. Celui-ci va donc pouvoir se rendre compte du tort qu’il a causé et de ce qu’il doit faire pour se racheter de l’acte qu’il a commis. La médiation, dans le cadre de la justice pénale des mineurs, a avant tout une dimension sociale et a l’avantage d’intégrer toutes les parties concernées par le conflit. Cette médiation n’est toutefois pas obligatoire et n’est offerte qu’avec le consentement des deux parties. Elle peut être envisagée à tous les stades de la procédure et même pendant l’exécution des mesures, soit après le jugement.

À travers la médiation, les personnes abordent les suites à donner à la procédure pénale en cours et envisagent leurs propres solutions afin d’aboutir à un accord, qui peut comprendre ou non le retrait de la plainte. Le contenu de la médiation (ce qui s’y est dit) est confidentiel à l’égard des autorités judiciaires, ces dernières n’étant informées que de l’éventuel accord trouvé lors la médiation. À la différence de la conciliation, ce sont les parties qui dans la médiation trouvent elles-mêmes les solutions. Ces solutions doivent ensuite être acceptées tant par la victime que par le mineur délinquant. Le médiateur n’impose donc pas de solutions aux parties. La médiation est en règle générale (70%) très appréciée par les personnes qui y ont eu recours.

The remedies available

An remedy is an application against any decision or act. The appeal also refers to the written document containing the appeal.

The remedies fall into two categories: ordinary and extraordinary remedies. In principle, the court that renders a judgment gives every guarantee of justice and rectitude. However, in order to provide an additional guarantee, provision has been made for legal remedies that operate under the rule of a two-tier or two-instance court.

Under this procedure, a dispute may be dealt with in fact and in law successively by two hierarchical bodies:

- Once by a court of first instance or first instance, which renders a judgment.

- A second time by a court of appeal or a court of second instance, which issues a binding judgment.

If the parties are still not satisfied with this second judgment, they may resort to an extraordinary means called an appeal in cassation.

The appeal

An appeal is the ordinary means of appeal in order to obtain a reform of the trial proceedings. The possibility of appeal is the same in all legal systems. However, it is possible that a first instance decision may be rendered without appeal, particularly if the social or economic stakes are negligible. Justice is an expensive service and its implementation requires respect for proportionality.

The appeal has two effects: a suspensive effect that suspends the judgment of the first instance, and a devolutive effect that requires the judge of the first instance to transmit to the judge of appeal the knowledge of the whole case. If necessary, the case will be retried in a new way. In this case, the judge will review both the facts and the law, i.e. the form and substance. An appeal court issues an enforceable judgment that will replace the first instance judgment. This judgment may not be the subject of a new ordinary appeal.

The appeal in cassation

An appeal in cassation is an extraordinary appeal, in which a party asks a superior court to set aside a judgment because it considers that there has been a violation of the law. Therefore, the appeal is not vested and the case is only judged in law, the facts being taken for granted. An appeal in cassation generally has no suspensive effect, except in the case where the judge of cassation so decides.

In principle, the judge of cassation does not issue enforceable judgments by the parties to the proceedings. If he considers that the decision referred is correct, he confirms it and in this case the decision of the lower court will be enforced. If, on the other hand, he considers that the decision is not in accordance with the law, then he breaks it and refers the case back to the Court of Appeal that issued the judgment in question. The power of cassation is subsidiary to the appeal and the law lists restrictively the means that the appellant may invoke in cassation. These are generally serious defects of the law.

In summary, an appeal is an extraordinary means of appeal by which a party seeks to have a Supreme Court set aside the judgment in the event of a serious violation of the law.

The revision

It is an extraordinary remedy by which a party requests the full resumption of a trial that has already entered into force and has therefore already been executed.

To have a trial reviewed, it must be possible to prove that significant new facts, which could not be invoked at the previous trial, have been discovered. In this case, the law admits that when a judgment is vitiated by a serious defect, it may be revised.

Annexes

- Kolb, Robert. La Bonne Foi En Droit International Public: Contribution À L'étude Des Principes Généraux De Droit. Genève: Institut Universitaire De Hautes Études Internationales, 1999.

References

- ↑ Publication de Victor Monnier repertoriées sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Hommage à Victor Monnier sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Publications de Victor Monnier sur Cairn.info

- ↑ Publications de Victor Monnier sur Openedition.org

- ↑ Paage personnelle de Victor Monnier sur le site de l'Université de Aix-Marseille

- ↑ En Hommage À Victor Monnier.” Hommages.ch, 11 Mar. 2019, www.hommages.ch/Defunt/119766/Victor_MONNIER.