The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007

Based on a lecture by Michel Oris[1][2]

Agrarian Structures and Rural Society: Analysis of the Preindustrial European Peasantry ● The demographic regime of the Ancien Régime: homeostasis ● Evolution of Socioeconomic Structures in the Eighteenth Century: From the Ancien Régime to Modernity ● Origins and causes of the English industrial revolution ● Structural mechanisms of the industrial revolution ● The spread of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe ● The Industrial Revolution beyond Europe: the United States and Japan ● The social costs of the Industrial Revolution ● Historical Analysis of the Cyclical Phases of the First Globalisation ● Dynamics of National Markets and the Globalisation of Product Trade ● The Formation of Global Migration Systems ● Dynamics and Impacts of the Globalisation of Money Markets : The Central Role of Great Britain and France ● The Transformation of Social Structures and Relations during the Industrial Revolution ● The Origins of the Third World and the Impact of Colonisation ● Failures and Obstacles in the Third World ● Changing Methods of Work: Evolving Production Relationships from the End of the Nineteenth to the Middle of the Twentieth Century ● The Golden Age of the Western Economy: The Thirty Glorious Years (1945-1973) ● The Changing World Economy: 1973-2007 ● The Challenges of the Welfare State ● Around colonisation: fears and hopes for development ● Time of Ruptures: Challenges and Opportunities in the International Economy ● Globalisation and modes of development in the "third world"

In our exploration of economic developments from 1973 to 2007, we delve into a crucial period that has shaped the contemporary global economic landscape. This era, marked by profound changes and major challenges, saw the world go through significant economic and social transitions. Beginning with the first oil shock in 1973, which shook the foundations of the global economy, we have witnessed a series of events and policies that have redefined international economic relations, labour market structures and the management of environmental resources.

This period also saw the rise of neo-liberalism, with figures such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan challenging the principles of the welfare state and ushering in an era of market liberalisation and economic globalisation. The impact of these policies, coupled with rapid technological change and globalisation, led to profound transformations in the structure of employment, exacerbating inequalities and reshaping social dynamics.

In exploring this pivotal period, we seek to understand how the decisions, crises and innovations of these thirty-four years not only shaped the course of economic history, but also continue to influence the economic and social realities of today. This review offers an insight into the forces that have shaped our modern world and the lessons we can learn to navigate the uncertain future of the global economy.

Global Impact of Oil Shocks and Ecological Awakening[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

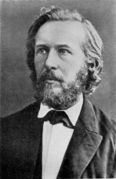

The evolution of ecology and environmental awareness, as you have described it, dates back to the 19th century and includes major contributions to the field of environmental science. Ernst Haeckel, a German naturalist, played a pioneering role by introducing the term "ecology" in 1866. This term, derived from the Greek "oikos" meaning "home" or "environment", and "logos" meaning "study", was used by Haeckel to describe the science of the relationships of organisms with their environment and with each other. This definition laid the foundations for modern understanding of ecological interactions. Long before Haeckel, the French physicist Joseph Fourier had already theorised about the greenhouse effect in 1825. He proposed that the Earth's atmosphere could act like the envelope of a greenhouse, retaining heat and thus affecting the planet's climate. This theory was later verified by the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius, who established a relationship between carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere and the Earth's temperature, laying the foundations for our current understanding of climate change. At the same time, George Perkins Marsh, a British naturalist, highlighted the impact of human activity on nature in 1864. In his book, he highlighted the way in which human actions modified the environment, marking one of the first acknowledgements of human ecological impact. These discoveries and theories laid the foundations for modern ecology and environmental science. However, although these concepts were developed in the nineteenth century, they did not immediately lead to significant changes in policy or public perception. It was not until the twentieth century that the importance of these ideas was fully recognised, leading to their deeper integration into environmental policy and public awareness.

The Club of Rome's "Stop Growth" report in 1972 represented a significant turning point in global awareness of environmental and economic issues. The report brought together politicians, academics and scientists, uniting diverse fields of expertise to theorise scientific ecology in a global context. At the heart of the report was the modelling of interactions between human activities and the natural environment. The team used advanced computer models to simulate the impacts of human actions on nature and their potential feedback on human societies. These models have brought to light the reality of our planet's environmental limits and finite resources, a concept that has received little media coverage until now. One of the most striking aspects of the report concerned essential resources such as coal and oil. The Club of Rome drew attention to the fact that these resources are not only finite, but that their uncontrolled exploitation could lead to their exhaustion. The modelling of the end of oil fields particularly sounded the alarm, given the central role of oil in the economies of Western countries. The report also emphasised that even renewable resources are not inexhaustible. Over-exploitation can lead to a point of no return, where the natural capacity for regeneration is exceeded, leading to their exhaustion. "Stop Growth" has played a crucial role in raising awareness of ecological limits and the need for sustainable resource management. It paved the way for more in-depth discussions on sustainable development and the environmental impact of economic policies, considerably influencing ecological and economic thinking in the decades that followed.

The first oil shock in 1973, triggered by the Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur war, marked a crucial moment in the world's awareness of the finiteness of resources, particularly oil. The attack on Israel by Egyptian and Syrian forces led to a major retaliation by the member countries of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which reduced their production and marketing of oil. This action resulted in a spectacular rise in oil prices and shortages in several countries, particularly in the industrialised West. This oil shock had a profound impact on the global economy, but it also played an important role in raising awareness of the world's dependence on non-renewable energy resources. The event reinforced the legitimacy of the Club of Rome's warnings, expressed a year earlier in their "Stop Growth" report, which warned of the dangers of over-exploiting limited natural resources. Trips to the Moon, notably NASA's Apollo missions, also played a role in changing the world's perception of planet Earth. Seeing the Earth from space offered a unique and unifying perspective on the planet, emphasising its finite and fragile nature. This 'externalisation' of our planet, as you have described it, has contributed to a growing awareness of the existence of a common planet and has had a significant impact on international relations. It has served to reinforce the idea that environmental challenges require cooperation and a global approach. The oil crisis of 1973, combined with space exploration and the warnings of the Club of Rome, contributed to a fundamental change in the way the Earth's resources are perceived and managed, leading to policies more geared towards sustainability and international cooperation on environmental issues.

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, more commonly known as the Rio Conference of 1992, marked a decisive step in the way the world approaches development and environmental conservation issues. The conference introduced the concept of sustainable development to the heart of international policy, a concept that seeks to balance the need for economic and social development with the preservation of natural resources for future generations. The principle of sustainable development, as established at Rio, represents a significant paradigm shift. It recognised that economic growth should not be achieved at the expense of the environment, and emphasised the importance of considering long-term environmental impacts in the planning and implementation of development policies. This concept encouraged nations to rethink their approaches to economic progress, orienting them towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly methods. The conference also highlighted the tension between national interests and globalisation. Environmental challenges, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, know no national boundaries and require international cooperation to be effectively addressed. This has posed challenges to the system for representing the world, as the interests and capacities of different states vary considerably. The Rio Conference laid the foundations for a new way of thinking and acting on a global scale, recognising that the well-being of people and the health of our planet are inextricably linked. This recognition led to the adoption of more sustainable policies and practices in many countries, and has influenced international discussions and actions in the decades since.

Recession: Analysis from 1973 to 1990[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Great Depression that marked the end of the twentieth century in the Western world is distinguished by its unique nature and characteristics, different from previous economic crises. This period was defined by a series of economic phenomena which, taken together, created a difficult and complex economic context. One of the most significant aspects of this period was the marked slowdown in the growth of per capita Gross National Product (GNP). Between 1971-1973 and 1991-1993, this growth fell to around 1.9% per annum, a marked decline compared with the average of 3.1% observed between 1950 and 1971. This slowdown in growth signalled a decline in economic momentum and a reduction in the increase in per capita wealth. This period was also characterised by a combination of inflation and economic stagnation, a phenomenon often referred to as "stagflation". Inflation, which manifests itself as a general increase in prices, occurred simultaneously with low or non-existent economic growth. This presented unique challenges for policymakers, as traditional strategies to combat inflation could exacerbate stagnation, and vice versa. In addition, rising unemployment was another key feature of this period. Rising unemployment, together with slower economic growth and inflation, created a climate of uncertainty and economic hardship for many people. This period was not an economic crisis in the traditional sense. Unlike a recession or economic depression characterised by a rapid and deep contraction of the economy, this period can be better described as a prolonged phase of weak economic growth, accompanied by a variety of other economic problems. This situation required innovative political and economic responses to stimulate growth, while managing inflation and unemployment.

Dynamics of the Slowdown in Economic Growth[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The slowdown in economic growth during this period, although less severe than the Great Depression of the 1930s, bears some similarities to periods of low economic growth in the past. The comparison with the inter-war years is apt, as this period was also marked by economic instability and fluctuating growth rates. It is important to note that economic terms such as "recession" and "depression" are often defined by specific criteria. A depression is generally characterised by a deeper and more prolonged economic contraction than that seen in a recession. Although the slowdown at the end of the 20th century did not reach the scale or severity of the Great Depression of the 1930s, it nevertheless represented a period of significant economic difficulty, with stagnant growth, high inflation and increased unemployment. This interpretation highlights the complexity of the economic situation at the time and shows how, even in the absence of a major economic crisis like that of the 1930s, a prolonged downturn can have considerable repercussions on society and the economy. This period therefore required tailored political and economic responses to meet these unique challenges.

Triptych of the Causes of the Economic Slowdown[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Impact and repercussions of the 1973-1974 and 1979-1980 oil shocks[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The year 1973 represented a major turning point for Western economies, particularly in terms of their dependence on oil. The oil crisis of 1973, triggered by the Yom Kippur War, had a profound impact on the world economy, particularly on Western countries. The Yom Kippur War began with a surprise attack by Arab armies on Israel. The Israeli counter-attack provoked a significant reaction from the Arab oil-producing countries. In response to Western support for Israel, these countries, members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decided to drastically reduce their oil production. This reduction in supply, combined with persistently high demand, has led to a spectacular rise in oil prices. The price of oil tripled in 1973, making the Western economy much more expensive to run. This rise in energy costs led to widespread inflation and affected many sectors of the economy, including transport, manufacturing and even home heating. This crisis has highlighted the vulnerability of Western economies to fluctuating oil prices and their dependence on imported oil. It also stimulated the search for alternative sources of energy and reflection on energy policies and energy security, concerns that remained relevant in the decades that followed.

The second oil crisis in 1979 served as a stark reminder to European countries and other industrialised nations of their heavy dependence on imported oil. This crisis was triggered by a number of factors, not least the Iranian revolution, which led to a significant drop in oil production in Iran, one of the main oil exporters at the time. The drop in Iranian production, combined with fears of increased political instability in the region, led to a sharp rise in oil prices. Prices almost doubled, with considerable economic effects around the world. As with the first oil shock in 1973, this price rise had a direct impact on economies that relied heavily on imported oil, particularly European economies. The second oil shock highlighted the vulnerability of oil-importing countries and underlined the need to diversify energy sources. This led to a growing awareness of the need to develop alternative and renewable energy sources, as well as to improve energy efficiency. In addition, the crisis has stimulated increased interest in national and international energy policies aimed at reducing dependence on oil and enhancing energy security.

Consequences of the end of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1973[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The end of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1973 marked a decisive turning point in the international monetary system. Set up in 1944, these agreements had established a system of fixed exchange rates, in which the currencies of the member countries were linked to the US dollar, itself convertible into gold. The dissolution of this system led to profound changes in global economic dynamics. With the break-up of the Bretton Woods agreement, exchange rates are no longer fixed but floating, meaning that they can vary freely in response to market forces. This transition to floating exchange rates has introduced a much higher level of uncertainty and volatility into international economic relations. Exchange rate stability, hitherto guaranteed by the Bretton Woods system, was fundamental to international trade and investment. The end of this stability has had major consequences. Currencies considered to be weak were particularly vulnerable to speculation and were often devalued. In addition, as the US dollar was no longer pegged to gold, its value became subject to greater fluctuations, adding to the uncertainty and complexity of international trade. This period of transition also required adjustments in national economic policies and prompted further reflection on the mechanisms for regulating foreign exchange markets and international monetary cooperation. The end of the Bretton Woods agreements marked a new era in world finance, characterised by greater flexibility but also by greater currency instability.

The formation of the European Union (EU) and its evolution in monetary policy reflect a response to the challenges posed by exchange rate fluctuations, particularly after the end of the Bretton Woods agreements. Initially, the EU was primarily a free trade market, where the free movement of goods, services and capital was a fundamental principle. However, exchange rate volatility after 1973 posed significant challenges to maintaining economic and trade stability within the Union. In response to this instability, several European countries took the initiative of linking their currencies to the Deutschemark, which was considered to be one of the strongest and most stable currencies at the time. This gave rise to the "European currency snake", a mechanism designed to limit exchange rate fluctuations between certain European currencies. The currency snake was an attempt to stabilise exchange rates by keeping them within limited fluctuation margins against the Deutschemark. The European currency snake can be seen as a precursor to the deeper monetary integration that led to the creation of the euro. By attempting to stabilise exchange rates between the currencies of the member countries, this mechanism laid the foundations for closer economic and monetary cooperation in Europe. It has also underlined the importance of monetary policy coordination for the success of a free trade market, particularly in a context where economies are closely interconnected. The European monetary snake was an important step in the process of European integration, ultimately leading to the creation of the euro and the establishment of Economic and Monetary Union, which has strengthened economic integration and monetary stability within the EU.

The link between the "European monetary snake" and the 1973 oil crisis, as well as the labelling of oil in dollars, is indeed significant in the context of monetary developments in Europe. The oil crisis highlighted the vulnerability of European economies to fluctuations in the US dollar, since oil, a vital resource, was mainly traded in dollars. This situation exacerbated the effects of the oil crisis in Europe, making European economies even more sensitive to variations in the dollar exchange rate. Against this backdrop, the "European currency snake" was an attempt to stabilise European currencies by pegging them to the Deutschemark, thereby reducing their vulnerability to fluctuations in the dollar. By harmonising the values of the various European currencies around the Deutschemark, the member countries sought to mitigate the impact of external shocks and promote greater economic stability within Europe. The adoption of the euro can be seen as a continuation and amplification of this logic. The euro began as a financial currency, used in accounting and financial transactions, before becoming a real currency in circulation. This process was both a simplification - replacing several national currencies with a single common currency - and a major political decision, reflecting a deep commitment to European unification and integration. The creation of the euro marked an important stage in the process of European integration. It represented not only monetary unification but also a shared commitment to deeper economic integration. This underlined the willingness of EU member countries to work closely together to address global economic challenges, and to consolidate their integration to strengthen their economic stability and prosperity.

Analysis of the slowdown in productivity gains[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

During the period in question, Western economies, particularly in Europe and the United States, faced a significant slowdown in productivity gains, which posed considerable challenges to their economic growth. After a period of rapid productivity growth in the decades following the Second World War, largely due to technological innovations and improvements in industrial efficiency, the 1970s marked a change. The pace of productivity gains began to decline, a phenomenon attributable to a number of factors, including a plateau in technological innovation, reduced investment in certain key sectors, and saturation in the improvement of existing production processes. This slowdown in innovation has had a direct impact on productivity growth. Innovation is a key driver of productivity growth, and when it falters, this tends to slow the economy as a whole. This can be the result of reduced investment in research and development, a lack of revolutionary new technologies, or the difficulty of continuing to improve existing production methods. Alongside this slowdown in productivity growth, Western economies have also experienced periods of high inflation and rising unemployment, a situation often referred to as 'stagflation'. This combination of economic stagnation and high inflation has presented a complex challenge for policymakers. Traditional measures to combat inflation could exacerbate the problem of unemployment, and vice versa, making management of the economy particularly difficult. These economic challenges required nuanced policy responses and led to reforms in various areas. Governments have had to revise their monetary policies, regulate the labour market more effectively and encourage innovation and investment to stimulate growth and combat economic stagnation. This period has therefore been marked by a search for balance between various economic objectives, while trying to navigate a changing global economic environment.

Inflation: Origins and Consequences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Inflation, which translates into higher retail prices, is closely linked to the law of supply and demand. This fundamental economic principle states that when demand for goods and services exceeds available supply, prices tend to rise. Conversely, if supply is abundant and demand is low, prices tend to fall. In a context where consumption is high and supply is unable to keep up, as you mentioned, upward pressure on prices arises, leading to inflation. This can happen for a variety of reasons, such as limitations in production capacity, logistical problems, or shortages of raw materials. On the other hand, if the economy is able to produce goods and services at low cost and in sufficient quantity to meet demand, inflation can be kept relatively low. During a normal period, an inflation rate of 9% is indeed considered high. Such a level of inflation can reduce the purchasing power of consumers and have a negative impact on the economy. In the European context of the time you mention, characterised by economic challenges such as oil shocks and exchange rate variations after the end of the Bretton Woods agreements, a high inflation rate was not unusual. These external factors, combined with domestic economic policies, contributed to higher than normal inflation. This period of high inflation posed considerable challenges for European governments and central banks, which had to find ways of balancing economic growth with inflation control, often by adjusting monetary and fiscal policies. Managing inflation has become a major concern, underlining the importance of prudent and responsive economic policy in maintaining economic stability.

Inflation can occur in different ways and with varying intensity, depending on economic circumstances and the policies implemented by individual countries. The oil shocks of the 1970s are classic examples of external factors causing rapid and high inflation, often referred to as "inflationary surges". These shocks led to a sudden increase in energy costs, which spread throughout the economy and caused prices to rise rapidly. Apart from these exceptional events, inflation can be more gradual and sustained, often referred to as 'substantial inflation'. This type of inflation develops over a longer period and can be the result of various factors, such as expansionary monetary policies, rising production costs, or strong demand outstripping available supply. The way in which different countries have managed inflation over this period varies considerably. France and Germany, for example, adopted distinct approaches to dealing with inflation. Germany, in particular, has been recognised for its strict monetary policy and commitment to price stability, often attributed to the influence of the Bundesbank, its central bank. This policy has helped to keep inflation rates relatively low in Germany compared to other countries. France, on the other hand, has also implemented effective policies to control inflation, although its economic strategies and challenges have been different. French policies have often included a combination of price controls, fiscal policies and sometimes monetary devaluations to manage inflation. These differences in inflation management reflect the diversity of economic contexts and policy approaches within European countries. They also illustrate how national economic and monetary policy strategies can significantly influence a country's overall economic performance.

The 1970s and early 1980s represented a complex period for the global economy, characterised by challenges such as high inflation, slowing growth and rising unemployment. This period was particularly difficult for workers, as even in contexts of good economic performance, many experienced wage stagnation. Despite economic growth in some sectors, real wage increases were limited, which had a negative impact on people's purchasing power. This wage stagnation, coupled with an unstable global economic environment marked by oil shocks and political uncertainty, led to a period of economic insecurity for many citizens. Around the mid-1980s, the situation began to change for the better. The macroeconomic policies implemented by governments and central banks began to bear fruit, and many countries managed to emerge from the period of high inflation that had marked the previous decade. The fight against inflation was waged mainly through tighter monetary policies, including raising interest rates to reduce inflationary pressure. Although these measures were controversial because of their potential effects on economic growth and unemployment, they ultimately succeeded in stabilising the economies. The success of these policies in controlling inflation has been a major development for world economies. By regaining control of inflation, countries have created an environment more conducive to stable, long-term economic growth. This stabilisation helped to restore confidence in the capabilities of monetary and economic policies, laying the foundations for periods of economic prosperity in the years that followed. The lessons learned during this turbulent period have had a significant influence on future economic policies, demonstrating the importance of the responsiveness and adaptability of economic policies in the face of global challenges.

The contrast you describe between the economic crisis and the social crisis during the 1970s and 1980s is a complex and significant phenomenon. Although there was a small economic crisis around the 1980s, the social problems were more pronounced and persistent. On the one hand, there was wage stagnation, mass redundancies and high inflation, which created an employment crisis and reduced purchasing power for many workers. This situation led to considerable social tensions, as many people found themselves in a precarious financial situation. On the other hand, certain sectors have experienced different dynamics. For example, the import of American wheat contributed to a crisis in European agriculture, but it also led to a fall in food prices, which offered a form of compensation to consumers. This illustrates the complexity of the global economy, where changes in one sector can have unexpected effects on others. Despite these nuances, the years 1973, 1980 and 1985 were marked by relatively good economic growth. However, this growth was not uniformly beneficial in social terms. The antagonism between a growing economy and the social difficulties encountered by many citizens is a characteristic of what is known as "stagflation". This term describes an economic situation in which stagnation (marked by slowing economic growth and rising unemployment) coexists with inflation (a general rise in prices). Stagflation represents a particular challenge for economic policy, as traditional measures to stimulate growth or control inflation may not be effective or may even exacerbate the other aspect of the problem.

The Evolution and Challenges of Unemployment[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The transition of unemployment from cyclical to structural during this period represents a significant change in the dynamics of the labour market. Cyclical unemployment is generally linked to temporary economic recessions and tends to diminish as the economy recovers. Structural unemployment, on the other hand, is more deeply rooted and can persist even when the overall economy shows signs of improvement. This phenomenon, where unemployment becomes persistent and less responsive to economic growth, was particularly marked in several countries during the 1970s and 1980s. This situation can be attributed to various factors, such as technological change, changes in the skills required on the labour market, regional imbalances and labour market rigidities. Germany's experience between 1958 and 1962 illustrates a striking contrast with this period. Germany had an exceptionally low unemployment rate, falling to around 1%, a situation close to full employment. This success was partly due to strong post-war economic growth, industrial reconstruction and modernisation, and effective economic policy. Other countries, such as Switzerland and Japan, also managed to achieve full employment during the Trente Glorieuses, a period of strong economic growth and social stability following the Second World War. These successes were the result of a combination of factors, including appropriate economic policies, a strong demand for labour, and in some cases, a highly skilled workforce and internationally competitive industry. However, with subsequent economic and social changes, including oil shocks, increased global competition and technological change, the unemployment challenge has evolved, leading to an increase in structural unemployment in many countries. This evolution has necessitated new approaches to employment and training policy to adapt to the changing realities of the labour market.

The concept of frictional unemployment plays an important role in labour market analysis, particularly in the United States where occupational mobility is more common. Frictional unemployment refers to the short, temporary transition period during which individuals change jobs. This type of unemployment is generally considered to be a normal and healthy aspect of the economy, reflecting the fluidity and flexibility of the labour market. In the United States, the labour market is characterised by relatively high occupational mobility, with individuals frequently changing jobs or careers throughout their working lives. This mobility is often seen as a positive feature of the US economy, as it enables a better match between workers' skills and employers' needs, thereby promoting innovation and economic efficiency. This tradition of changing jobs contributes to higher frictional unemployment, but it also makes the US labour market more dynamic. The ease of changing jobs encourages workers to seek out positions that better match their skills, interests and career goals. It also makes it easier for companies to adapt to market and technological changes by recruiting employees with the necessary skills. However, it is important to note that, while beneficial in many ways, high levels of frictional unemployment can also pose challenges, particularly in terms of job security for workers and the costs to businesses of recruitment and training. Effective management of frictional unemployment therefore requires policies that support both labour market flexibility and job stability for workers.

The difficulty of returning to the full employment levels of the Trente Glorieuses has effectively marked a turning point in the understanding and management of modern economies. The Trente Glorieuses, the post-war period up to the early 1970s, were characterised by exceptional economic growth, increased output and low unemployment rates in many developed countries. It was a period of reconstruction, technological innovation and sustained economic expansion. However, with the end of this period, marked in particular by the oil shocks of the 1970s and the slowdown in economic growth, the model of full employment began to crumble. The most significant change was the break in the traditional correlation between output and unemployment. Historically, there had been a fairly direct relationship: when output rose, unemployment fell, and vice versa. But since this period of change, this relationship is no longer so obvious. This new reality has manifested itself in the phenomenon where an increase in output does not necessarily lead to a reduction in unemployment. This can be explained by a number of factors, such as automation, which allows an increase in output without a corresponding increase in jobs, or structural changes in the economy, where the new jobs created require different skills to those lost. Breaking this traditional rule has meant that the economy can sometimes generate jobs, but not systematically. This development has posed significant challenges for economic and social policies, requiring more nuanced and tailored approaches to managing the labour market. It has also highlighted the importance of training and retraining, and the need for policies that encourage job creation in growth sectors.

The 1990s: Between Economic Renewal and Growing Uncertainty[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Economic Renaissance: Back to Growth[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

During the 1990s, the United States enjoyed a period of remarkable economic prosperity, positioning itself as a hegemonic power on the world economic stage. The decade was characterised by strong economic growth, controlled inflation and significant job creation, consolidating the United States' dominant position in the global economy. US economic growth in the 1990s was driven by several key factors. One of the most important was the rapid expansion of the digital economy, notably with the emergence and popularisation of the Internet and information and communication technologies. These technological advances have transformed economic sectors and led to the creation of new markets and employment opportunities. For example, US GDP grew impressively during this period, from around $9.6 trillion in 1990 to over $12.6 trillion in 2000. At the same time, the US managed to keep inflation relatively low throughout the decade. This price stability was largely the result of effective monetary policies pursued by the US Federal Reserve. Under the leadership of Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve was able to navigate between stimulating economic growth and preventing inflation, by strategically adjusting interest rates. The inflation rate, which was around 5.4% in 1990, fell significantly to around 3.4% in 2000. This period was also marked by substantial job creation. The growth of the technology and service industries has opened up many new employment opportunities, helping to reduce unemployment and improve the quality of life of citizens. The unemployment rate in the United States fell significantly during this decade, from almost 7.5% in the early 1990s to around 4% by the end of the decade.

Collapse of the Stock Market Bubble: A New Reality[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The bursting of the stock market bubble in 2001 marked a turning point in the US economy, bringing to an end an era of rapid economic growth and technological hegemony. This stock market crisis, which was closely linked to the bursting of the information and communication technology bubble, had a considerable and far-reaching impact well beyond the stock market. The stock market bubble of the 1990s was largely fuelled by speculative investment in the technology sector, particularly Internet companies and technology start-ups. Many of these companies, valued at astronomical sums despite often non-existent profits, saw their shares reach dizzying heights. However, this meteoric growth was based more on speculation than on solid economic foundations. When the bubble finally burst in 2001, many technology companies saw their value plummet, triggering a major stock market crisis and a loss of confidence in the technology sector. The economic impact of this crisis was profound. The US GDP growth rate, which had reached 4.1% in 2000, fell to around 1.2% in 2001. This marked slowdown was caused by a decline in investment in the technology sector, as well as a general drop in consumer and business confidence. This led to a slowdown in the economy as a whole, affecting various sectors and contributing to an increase in unemployment, particularly in the technology sector. The repercussions of the bursting of the stock market bubble extended far beyond the borders of the United States, affecting global markets and underlining the interconnected nature of the world economy. The crisis highlighted the risks associated with excessive speculation and overconfidence in fast-growing sectors. It has also demonstrated the need for greater regulation and oversight of financial markets to prevent similar crises in the future. In short, the bursting of the stock market bubble in 2001 not only marked the end of a period of economic prosperity in the United States, but also served as an important lesson in the volatility of financial markets and the importance of prudence in investment and economic management.

The paradox of the US economy in the 1990s and early 2000s lay in its ability to display apparent health while concealing underlying structural fragilities. This period was marked by robust economic growth, but this growth was partly underpinned by factors that also threatened its long-term stability. One of the main drivers of economic growth was household over-indebtedness. The positive economic climate of the 1990s encouraged consumers to increase their spending, often on credit. This rise in credit consumption stimulated the consumer and producer economy, making a significant contribution to economic growth. However, this model was based on the ability of households to repay their debts, an ability that could be jeopardised by a change in the economic context, such as a rise in interest rates or an economic slowdown. Businesses, particularly in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector, also contributed to this growth dynamic through over-indebtedness. In order to invest and innovate, many companies in the ICT sector have taken on large amounts of debt. While this debt has enabled rapid expansion and significant innovation, it has also made these companies vulnerable to market fluctuations and changes in financing conditions. An economic crisis occurs when the debt accumulated by both households and businesses can no longer be repaid. This creates difficulties not only for debtors, but also for lenders, who may find themselves faced with defaults and declining assets. In short, while debt played a key role in stimulating US economic growth, it also introduced an element of fragility, revealing an underlying vulnerability that could quickly turn a period of prosperity into an economic crisis.

The stock market bubble of the 1990s, particularly in the field of New Information and Communication Technologies (NICT), was a striking phenomenon characterised by a spectacular and ultimately unsustainable rise in the value of the shares of companies in the sector. This period saw a convergence of several factors that contributed to the formation of this speculative bubble. With the advent of the digital age and the explosion of Internet technologies, many innovative start-ups emerged, attracting the attention and investment of both large capitalist companies and small investors. The latter, often attracted by the prospect of quick profits, engaged in speculation, helping to artificially inflate the value of shares in NICT companies. This phenomenon has been accentuated by the opening up of markets and easier access to investment for the general public, leading to what is known as "popular capitalism". This term reflects the growing participation of individual investors in the stock market, often motivated by the attraction of rapid growth in stock market values in the NICT sector. However, the formation of the bubble revealed a growing divorce between the real economy and the financial economy. There was a significant distortion between financial value (the stock market valuation of companies) and real value (based on economic fundamentals such as revenues and profits). This situation led to a brutal corrective process when the bubble burst. Values, which were completely overestimated, collapsed, resulting in major losses for both private and individual investors. The bursting of the stock market bubble therefore led to an economic and social disaster, affecting not only companies in the NICT sector, but also the many investors who had bet on the continued rapid growth of stock market values. The crisis underlined the risks associated with excessive speculation and highlighted the dangers of a market disconnected from fundamental economic realities.

The financial crisis that began in the early 2000s and culminated in the crisis of 2008 is rooted in a series of problematic practices within listed companies, particularly in the New Information and Communication Technologies (NICT) sector. This period was characterised by the falsification of the balance sheets of many companies, a practice that misled investors and undermined confidence in the integrity of the financial markets. This was particularly damaging for investors in "popular capitalism", who depended on reliable and transparent information for their investment decisions. These dubious practices highlighted what can best be described as the 'structural demon' of the US economy: a growing reliance on debt. This trend has been exacerbated by the duality of the dollar, which is both a global reserve currency and a national currency, making monetary and financial management more complex. Excessive household debt, encouraged by years of easy credit and expansionary monetary policy, has created significant vulnerabilities in the economy. At the same time, excessive corporate debt has increased the risk of bankruptcies and market corrections. These factors, combined with a persistent negative trade balance, created fertile ground for the financial crisis of 2008. The crisis was triggered by the bursting of the housing bubble and exacerbated by the sub-prime crisis, where massive defaults on sub-prime mortgages triggered a meltdown in the banking and financial sector. This crisis revealed profound shortcomings in the global financial system, particularly in terms of financial market regulation and risk management. Ultimately, the run-up to the 2008 crisis was marked by a series of risky economic and financial decisions that ultimately led to one of the worst financial crises in modern history. The crisis highlighted the need for stricter regulation and improved governance in the financial sector, as well as the dangers of excessive reliance on debt and an economy based on speculation.

Towards the Financial Crisis of 2008: Premises and Triggers[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The 2008 financial crisis, one of the most serious since the Great Depression, was indeed the result of a combination of interconnected factors that exposed the structural weaknesses of the global economy. This economic cataclysm can be attributed to several key causes. Firstly, excessive debt played a central role in the genesis of the crisis. Both households and businesses, particularly in the United States, took on large amounts of debt, often beyond their ability to repay. This dynamic was particularly pronounced in the property sector, where the practice of sub-prime mortgages encouraged the acquisition of property by borrowers with poor credit ratings. The US trade deficit also contributed to the crisis. A persistent trade imbalance led to a build-up of debt and increased dependence on foreign financing, leaving the US economy, and by extension the global economy, vulnerable to external shocks. The falsification of balance sheets by many companies has exacerbated the problem. This practice distorted cyclical assessments and misled investors, regulators and the public about the true health of companies and the financial market. When these manipulations were revealed, confidence in the financial markets collapsed. Finally, a growing distortion between the financial economy and economic fundamentals was an aggravating factor. Speculation on the financial markets, disconnected from the real economy, led to a dangerous overvaluation of financial assets. When the speculative bubble burst, it triggered a cascade of financial failures. The 2008 crisis was therefore the product of these interdependent factors, highlighting flaws in financial regulation, risk management and global economic imbalances. It highlighted the need for far-reaching reforms in the financial sector and triggered debates on the need to realign the financial economy with economic fundamentals.

The 2008 financial crisis revealed that traditional economic fundamentals are no longer the only determining parameters in analysing and understanding global economic dynamics. The introduction and growing importance of the financial parameter has added a significant layer of complexity and uncertainty to the global economy. The interaction between the real economy and financial markets has taken on a new dimension. Previously, financial markets were seen primarily as reflections of the real economy, meaning that financial market performance was largely dependent on economic fundamentals such as GDP growth, unemployment and inflation. However, with the rise of financialisation - the increasing importance of the financial sector in the overall economy - the relationship between the real economy and the financial markets became more complex and sometimes disconnected. Financial markets have begun to exert a more direct and sometimes dominant influence on the real economy. Complex financial products, speculative investment strategies and increased global integration of financial markets have created an environment where fluctuations in financial markets can have immediate and profound repercussions on the global economy, independently of traditional economic indicators. This new reality has introduced a greater degree of uncertainty into the global economy. Financial crises can now arise and spread rapidly, even in the absence of any apparent problems in economic fundamentals. This has highlighted the need for better understanding and management of the financial sector, more effective regulation of financial markets, and increased oversight of financial risks to prevent or mitigate future crises. The 2008 crisis marked a turning point, illustrating that the stability and health of the global economy now depends not only on traditional economic fundamentals, but also on the complex and interconnected dynamics of financial markets.

The 2008 financial crisis, one of the most devastating since the Great Depression, was the result of a complex combination of interconnected factors. One of the main triggers of the crisis was the rise in interest rates, which had a direct impact on the property market. After a prolonged period of low interest rates, which had encouraged an aggressive expansion of mortgage lending, including to high-risk borrowers, rising rates made mortgages more expensive. This reduced demand for homes, causing house prices to fall. This fall in house prices had serious consequences for borrowers, particularly those who had taken out variable-rate mortgages. Many found themselves in a situation where the value of their loan exceeded the value of their home, making it increasingly difficult to repay their loan. This situation, compounded by falling property values, led to a significant increase in defaults and foreclosures. At the same time, the market had seen a proliferation of sub-prime mortgages, granted to borrowers with poor credit ratings. As interest rates rose, these borrowers found it increasingly difficult to repay their loans, leading to a rise in defaults. The situation was exacerbated by the existence of complex financial instruments, such as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), which bundled together these sub-prime mortgages. The devaluation of these financial instruments, due to the increase in defaults, severely affected the financial institutions that held them. The financial crisis of 2008 was therefore the result of a series of interrelated problems: a rise in interest rates, an excess of subprime mortgages, a fall in demand and property prices, and the complexity of the financial products based on these loans. These elements converged to create a crisis of exceptional scale, revealing numerous weaknesses in the global financial system and underlining the need for stricter reforms and regulations to prevent similar crises in the future.

The 2008 financial crisis was exacerbated by the overvaluation of property assets, a phenomenon directly linked to the creation and distribution of complex financial products. Sub-prime mortgages played a central role in this dynamic. These loans were made to borrowers with low incomes or poor credit histories, and therefore represented a higher risk of default. The overvaluation of property assets was encouraged by a booming property market, where house prices rose significantly and steadily. This rise in prices created a sense of optimism and a belief that property values would continue to rise indefinitely. Against this backdrop, sub-prime mortgages became an attractive way for sub-prime borrowers to become homeowners, and for lenders to generate substantial profits. These subprime mortgages were often bundled together and transformed into complex financial instruments, such as Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) and Asset-Backed Securities (ABSs). These instruments were then sold to banks, pension funds and other investors, often under the impression that these investments were safe and profitable. Credit agency ratings, which often gave these instruments high marks, reinforced this perception. However, when the property market began to weaken and house prices fell, the value of these overvalued property assets began to plummet. This had a knock-on effect on the CDOs and ABSs that were backed by these mortgages. The banks and investors who held these financial instruments suffered huge losses, as the value of the underlying assets fell drastically and default rates on subprime loans soared. The overvaluation of property assets, combined with the proliferation of sub-prime loans and the creation of complex financial products based on these loans, was a key factor in triggering the 2008 financial crisis. This crisis highlighted the dangers of excessive speculation in the property market and the risks associated with poorly understood and insufficiently regulated financial products.

Labour Market Change: Structural Unemployment and the End of Full Employment[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The current labour market situation is marked by a significant distortion, resulting from structural changes in the global economy. These changes are mainly due to deindustrialisation and the rise of the service sector. Since the 1970s, a process of deindustrialisation has been observed in many developed countries. This phenomenon has been characterised by a decline in the importance of the industrial sector in the economy, leading to the closure of many factories and the loss of manufacturing jobs. This de-industrialisation has posed major challenges, particularly in terms of retraining manual workers, whose skills are not always transferable to the service sector. At the same time as the industrial sector has declined, the tertiary sector, which includes services such as finance, education, health and information technology, has grown significantly. This expanding sector requires a different set of skills, often focused on technology, analysis and customer service. This economic shift has created a distortion in the labour market between those seeking to enter or re-enter, often armed with skills suited to a declining industrial sector, and those already integrated into the expanding services sector. This situation is exacerbated by the rapid pace of technological and economic change, making it difficult for many workers to adapt and retrain. In response to these challenges, continuous training and professional retraining policies are needed. These policies should help workers acquire the skills required in growth sectors and facilitate their transition to new areas of employment, thus ensuring a smoother adaptation to the changing realities of the labour market.

The current labour market landscape is strongly influenced by the decline in industrial employment and the rise in service employment, a phenomenon that marks a significant change from the era of the Trente Glorieuses. During this post-war period, despite the existence of sectors that had become obsolete, the industrial world was robust enough to compensate for these losses, often through the creation of new industrial jobs or through transformation within the same sector. However, with the advent of deindustrialisation, this dynamic has changed. The crisis in the industrial sector is no longer limited to problems internal to the secondary sector; it is also creating challenges in terms of professional retraining towards the tertiary sector. This transition is proving particularly difficult for blue-collar workers, who are often the hardest hit by these changes. The skills and experience acquired in the industrial sector do not necessarily match the requirements of the service sector, making their integration into the new labour market more complex. Workers, accustomed to a certain type of work and skills, often find themselves at a disadvantage in this new economic context. The transition to the service sector requires not only new skills, but also adaptation to a different working environment, often more focused on services, technology and interpersonal interaction. This raises important questions about the need for appropriate support and training policies. It is becoming crucial to put in place vocational training and retraining programmes, as well as employment support policies, to help workers in the industrial sector adapt and find opportunities in the expanding tertiary sector. Without these measures, there is a risk that a significant proportion of the industrial workforce will become marginalised in the modern economy.

The contemporary labour market is characterised by the "inside-outside" phenomenon, which illustrates the tendency of the market to close in on itself. This phenomenon makes it particularly complex for newcomers to enter the labour market, while mobility for those who are already integrated is generally easier. One of the main difficulties encountered by new arrivals, particularly young people, is the strong competition for entry-level positions, coupled with high requirements in terms of qualifications and experience. These obstacles are exacerbated by structural changes in the economy, such as de-industrialisation and the rise of the service sector, which require specific skills and appropriate training that are not always accessible to young entrants. This difficulty in accessing the labour market can have lasting implications for their career paths. On the other hand, for workers already established in the market, mobility within it is often facilitated by experience and skills acquired, as well as well-developed professional networks. These assets give them a competitive edge and facilitate their career progression or transition. Changes in the labour market also have gender implications. With the increase in employment in the tertiary sector, which tends to employ more women, and the decline in the secondary sector, traditionally dominated by male jobs, there is a potential rebalancing of opportunities between the genders. This could mean increased job opportunities for women, while men could face greater challenges, particularly in regions heavily affected by deindustrialisation.

The Welfare State: Rise, Challenges and Questioning[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Jobs Crisis at the Heart of the Welfare State Crisis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The evolution of the welfare state, from its heyday to its questioning, is intimately linked to the transformation of the labour market and technological change. This transition has had a profound impact on the social and economic model of the welfare state, particularly in Europe and North America.

During the Trente Glorieuses, technological innovation was generally associated with job creation. New technologies and industries created more jobs than they destroyed, fostering robust economic growth and a dynamic labour market. This favourable economic environment enabled welfare states to reach their peak between 1973 and 1990, marked by a significant increase in public spending on social protection, reflected in a growing share of GDP devoted to this expenditure.

However, from the 1990s onwards, this dynamic began to change. Innovations, particularly in the fields of automation and artificial intelligence, now seem to be destroying more jobs than ever before. Entire professions are being called into question by the arrival of technologies capable of carrying out tasks previously performed by humans. These developments are having a direct impact on the labour market, with rising unemployment and the casualisation of certain jobs.

The welfare state is thus faced with a twofold challenge. On the one hand, tax revenues, which largely finance social spending, are being affected by rising unemployment and job insecurity. Fewer people in work means less tax revenue from wages. On the other hand, expenditure is rising as more people rely on social benefits because of the difficulty of finding stable employment.

This situation has led to a rethink of welfare state models. Governments are faced with the need to reform their social protection systems to adapt them to this new economic and social reality, while ensuring the financial sustainability of these systems. Striking a balance between providing adequate social protection and managing public finances responsibly has become a central concern for many countries.

Challenges and Criticisms of the Welfare State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Questioning of the welfare state has grown over time, centred around two major criticisms that affect both its financial management and its social effectiveness. The emergence of budget deficits and the accumulation of public debt constitute the first major criticism of the welfare state. As social spending has increased, many governments have found themselves facing growing budget deficits, leading to a significant rise in public debt. This strained financial situation is often seen as the direct result of a system that is deemed to be too costly, or even a drain on public funds. Concerns about the long-term financial viability of the welfare state are exacerbated by falling tax revenues, a problem often linked to high unemployment rates and job insecurity. At the same time, there is a second major criticism of the social effectiveness of the welfare state. This debate focuses on the problems of abuse and fraud, particularly concerning undeclared work and the exploitation of social benefits. Some critics argue that the welfare state, in its current form, can create negative incentives, discouraging formal employment and encouraging a certain dependence on social benefits. This perspective has fuelled a discourse around the 'abusers' of the system, questioning the need for reforms to make social protection programmes more effective, accountable and less vulnerable to abuse. These criticisms highlight the complex challenges facing welfare states in the current economic and social context. On the one hand, there is an imperative need to provide a safety net for the most vulnerable citizens, and on the other, there is growing pressure to manage public finances responsibly and ensure that social protection systems are efficient and equitable. Striking a balance between these divergent objectives is a central challenge in contemporary political and economic debates about the future and shape of the welfare state.

The downsizing of welfare state policies in the 1980s was strongly influenced by the rise of neo-liberalism, an economic and political ideology that stood as a reaction to the dominant Keynesian principles of the post-war era. Neo-liberalism gained popularity during a period marked by an economic slowdown, increasing public spending to support the welfare state, and global political changes, notably the fall of the Soviet bloc. Neo-liberalism advocates a laissez-faire approach to economics, supporting a significant reduction in state intervention in the economy. Market liberalisation, privatisation of state-owned enterprises, deregulation and free competition are seen as the best means of stimulating economic growth and efficiency. Two political figures are often associated with the rise of neo-liberalism in the 1980s: Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, elected in 1979, and Ronald Reagan in the United States, elected in 1981. Both leaders implemented economic policies that reflected neo-liberal principles. Under Thatcher and Reagan, policies of privatisation, cuts in public spending, deregulation of industries and reducing the influence of trade unions were adopted. The aim of these measures was to reduce the role of the state in the economy and encourage greater participation by the private sector. This period marked a significant turning point in global economic policy. Neo-liberalism not only influenced domestic policies in the UK and the US, but also had an impact on global economic governance, with the promotion of market liberalisation on an international scale. Neo-liberal reforms have led to lasting changes in the structure of national economies and the global economic order.

The neo-liberal policies adopted in the 1980s led to significant changes in many aspects of social and economic governance, particularly in the field of education. A notable example of these changes is the transition from the allocation of student grants to the distribution of student loans. This change reflects a broader philosophy of neo-liberalism, according to which the individual is responsible for his or her own life and finances, including education. Under the neo-liberal approach, rather than providing grants to cover tuition fees as a gift, the emphasis is on student loans. These loans are to be repaid by students after completion of their studies, placing the financial responsibility directly on the individual. This approach is based on the idea that education is a personal investment for which the student should bear the costs, with the expectation that this investment will translate into better future income and career opportunities. This philosophy contrasts with the principles of classical and Keynesian liberalism, where access to education is often seen as a right, and where the state plays a more active role in providing educational opportunities, including through grants. Classical liberalism would argue that education should be accessible to all, regardless of their financial situation, and that the state has a role to play in ensuring this access. The move towards student loans is also based on the idea that the best and brightest individuals should be able to use their entrepreneurial spirit and personal initiative to succeed. However, this approach has been criticised for potentially creating financial barriers to education, limiting access to those who can afford the cost of loans, and increasing debt for young graduates. The shift from grants to student loans under the influence of neo-liberalism reflects a philosophy of individual responsibility and self-financing, but also raises questions about the equity and accessibility of education in contemporary society.

Trends in Poverty Rates: Context and Implications[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Rising poverty rates and growing inequalities in income distribution are worrying phenomena in many countries, exacerbated by neo-liberal policies and the effects of economic globalisation. The increase in the poverty rate is the result of several interdependent factors. De-industrialisation and job insecurity have led to a reduction in stable, well-paid jobs, particularly for low-skilled workers. At the same time, cuts in social spending by the welfare state, a pillar of neo-liberal policies, have weakened safety nets for the most vulnerable. Reduced investment in essential public services such as education and health has also contributed to this rise in poverty, leaving individuals and families less protected against the vagaries of the economy. At the same time, income inequalities are widening. Economic policies favouring deregulation, market liberalisation and tax cuts for the wealthiest have often been criticised for reinforcing the concentration of wealth within the richest strata of society. This concentration of wealth is at odds with the stagnation or deterioration of economic conditions for the majority of the population, creating a widening gap between rich and poor. The consequences of these phenomena are profound and varied. Socially, rising poverty and inequality can lead to increased fragmentation and polarisation of society, exacerbating social tensions and eroding social cohesion. Economically, these inequalities can restrict aggregate demand, as low-income people tend to spend a greater proportion of their income, which can limit overall economic growth. In the face of these challenges, there are calls for reform of economic and social policies, calling for a fairer distribution of wealth, stronger social safety nets, and greater investment in public services. These measures aim to establish more balanced and just societies, where opportunities and wealth are better shared between all segments of the population.

The situation in Switzerland regarding pensions and the elderly vote raises important questions about demography, social policy and intergenerational solidarity. In Switzerland, as in many other developed countries, the population is ageing as a result of rising life expectancy and low birth rates. This demographic change has significant implications for retirement and pension systems. The elderly, who make up a growing proportion of the population, often have a direct interest in pension and retirement policies. In Switzerland, where the political system allows for direct citizen participation through referendums and popular initiatives, older people can exert a significant influence on political decisions, particularly those concerning pensions. Rising pension costs are a major concern in Switzerland, as the number of pensioners increases while the number of contributing workers remains relatively stable or grows slowly. This puts financial pressure on the pension system, which has to find ways to fund retirement payments for a growing number of beneficiaries. This situation can lead to intergenerational conflict, as younger generations may feel aggrieved by a system that requires them to make increasing contributions to support pensions that they perceive as uncertain for their own future. On the other hand, retirees depend on these pensions for their financial security. Switzerland, like other countries facing similar demographic challenges, has to strike a balance between the needs and expectations of the elderly and the economic and social realities affecting younger generations. This often involves discussions about reforming pension systems, finding sustainable sources of funding and creating equitable policies that take into account the needs of all generations.

Analysis of Factors Contributing to the Rise in Inequality[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The rise in inequality and poverty in many countries is a complex phenomenon, one of the main causes of which is the retreat of the welfare state and the reduction in public spending. This trend, which began in the 1980s under the influence of neo-liberalism, has led to significant changes in the way governments approach social protection and the distribution of wealth. The retreat of the welfare state is characterised by reduced investment in essential social programmes. These include health, education, social housing, family support and pensions. Historically, the welfare state played a crucial role in reducing inequality by providing a safety net for the most vulnerable individuals and families. However, as public spending in these areas has fallen, the support offered by the state has weakened, increasing the risk of poverty and inequality. Cuts in public spending have had a direct impact on the poorest sections of the population, limiting their access to essential services. For example, budget cuts in education can restrict access to quality education for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, while reductions in health spending can make medical care inaccessible to people on low incomes. In addition, tax cuts for high earners and businesses, often justified by the desire to stimulate the economy, have contributed to an unequal distribution of wealth, with the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a minority. The retreat of the welfare state and cuts in public spending have played a key role in the rise of inequality and poverty. These policies have reduced the capacity of the state to provide adequate support to those most in need and have exacerbated economic and social disparities. Consequently, the fight against poverty and inequality requires a recommitment to more inclusive and equitable social and economic policies.

The weakening of trade unions over recent decades has played a significant role in increasing inequality and poverty. Historically, trade unions have been essential in defending workers' rights, negotiating fair wages and decent working conditions, and establishing labour standards that benefit a wide range of workers. However, various economic, political and social changes have led to their weakening. The changing economic structure, notably deindustrialisation and the emergence of the service sector, has eroded the traditional trade union base. In the service sector, unionisation is less widespread, and new forms of work such as freelance and contract work make unionisation more difficult. In addition, the neo-liberal policies adopted since the 1980s have often favoured the flexibilisation and deregulation of the labour market, weakening the power of trade unions and reducing their ability to protect workers' interests. Employers' attitudes towards unionisation have also changed, with many companies adopting strategies to discourage union formation or minimise their influence. At the same time, changes in labour legislation in some countries have restricted union activities, limiting their ability to act effectively. The impact of the weakening of trade unions on inequality and poverty is profound. Without effective union representation, workers have less power to negotiate fair wages and working conditions. This can lead to wage stagnation, an increase in precarious work and a deterioration in working conditions, exacerbating economic and social inequalities. Faced with this situation, it becomes essential to support workers' rights to organise and bargain collectively, and to recognise the crucial importance of trade unions in promoting equity and social and economic justice.

The globalisation of the labour market has brought about a profound transformation in global economic dynamics, marked by increased competition on the international labour market. This has brought both opportunities and challenges. With globalisation, companies now have access to a global workforce, intensifying competition for jobs. Workers are no longer just competing with their local peers, but also with those from countries where labour costs are often lower. This global competition can exert downward pressure on wages and working conditions, even in developed economies, as companies seek to remain competitive by minimising costs. One of the most visible aspects of this globalisation is the relocation and outsourcing of certain operations to countries where production costs are lower. Although this strategy can generate jobs in emerging economies, it often leads to job losses in developed countries, raising questions about the quality of the jobs created and workers' rights in these new environments. Globalisation also offers new opportunities, such as greater international mobility for some workers and access to enlarged markets for professionals and companies. However, it also presents major challenges, including the need for workers to adapt to an ever-changing global market and to maintain decent working and living standards. Faced with this complex reality, governments, companies and international organisations are faced with the difficult task of balancing the benefits and challenges of globalisation. It is becoming imperative to protect workers' rights and conditions while taking advantage of the opportunities offered by a more open and interconnected labour market. This requires a coordinated approach and appropriate policies to ensure that globalisation benefits all stakeholders fairly.

Thomas Piketty, in his research on the distribution of wealth and income, has made an important contribution to the understanding of contemporary economic inequalities. In particular, he has challenged the Kuznets curve, which postulated that economic inequality would decline as countries developed economically. According to Piketty, contrary to this hypothesis, inequalities have increased, notably due to the accumulation of capital among the richest, many of whom have inherited their wealth rather than having created it. Piketty points out that this accumulation of wealth among a minority leads to an increase in inequality, since this wealth is not redistributed fairly throughout society. This situation is exacerbated by tax systems that often favour the wealthiest and by a lack of investment in public services and social assistance that could benefit the majority of the population. At the same time, the Kuznets curve is also being put to the test by the growing duality of working sectors, particularly in the service sector. This sector is characterised by a wide variety of jobs, ranging from high-paying positions in areas such as finance or technology to insecure, low-paid jobs in services, retail or hospitality. This duality creates a dichotomy where some can earn large sums of money while others, often referred to as the "working poor", struggle to support themselves despite having a job. Migratory flows to developed countries often tend to be concentrated in the least remunerative sectors of the labour market, reinforcing this dualisation of the labour market. Migrants, in search of opportunities, often find themselves in low-skilled, low-paid jobs, which contributes to economic and social stratification. Piketty's observations and the challenges posed to the Kuznets curve highlight a growing duality and complexity in the global economy, marked by increasingly pronounced inequalities. This situation highlights the need for economic and social policies that promote a more equitable distribution of wealth and opportunities, in order to reduce disparities and promote inclusive economic growth.