Switzerland's state structure, political system and neutrality

Dome du Palais fédéral, avec la devise "Unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno" (un pour tous, tous pour un) inscrite dans la partie centrale.

| Professeur(s) | Victor Monnier[1][2][3][4][5][6] |

|---|---|

| Cours | Introduction au droit |

Lectures

- Définition du droit

- L’État

- Les différentes branches du droit

- Les sources du droit

- Les grandes traditions formatrices du droit

- Les éléments de la relation juridique

- L’application du droit

- La mise en œuvre d’une loi

- L’évolution de la Suisse des origines au XXème siècle

- Le cadre juridique interne de la Suisse

- La structure d’État, le régime politique et la neutralité de la Suisse

- L’évolution des relations internationales de la fin du XIXe au milieu du XXe siècle

- Les organisations universelles

- Les organisations européennes et leurs relations avec la Suisse

- Les catégories et les générations de droits fondamentaux

- Les origines des droits fondamentaux

- Les déclarations des droits de la fin du XVIIIe siècle

- Vers l’édification d’une conception universelle des droits fondamentaux au XXe siècle

The Federal State and the main organs of the Confederation and the Cantons

Historical reminder: the federal state is a compromise. Indeed, the competence of the federal State is not total, because the cantons retain a certain sovereignty. The least worse solution was therefore bicameralism. In addition, there are also elements that weigh change as soon as restructuring takes place: for example, a double majority is required to amend the Constitution.

The progressives wanted the cantons' sovereignty to be abolished; now they are represented by the National Council (the people) and the Federal Council (before 1848, Switzerland had no executive, no Federal Council). The latter also enabled the country to stay on course during the difficulties of the 19th century.

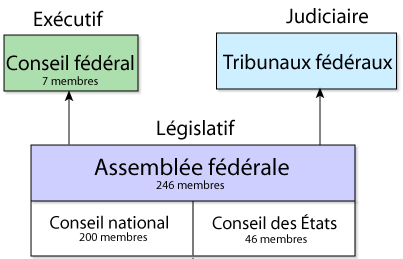

At the federal level

The Federal Assembly

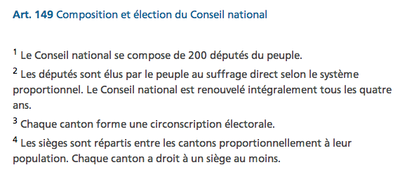

The Federal Assembly, or Federal Parliament, represents the supreme authority of the Confederation composed of two chambers:

- the National Council, which is composed of 200 deputies of the elected people in proportion to the population of the cantons.

- the Council of States is composed of 46 deputies from the cantons.

The two Chambers sit in two different chambers, but they both have the same weight and competence. This perfect parity is called perfect bicameralism.

Members of Parliament have a militia function: this function is not their job. On the other hand, they are not bound by an "imperative mandate", i.e. they are free in the way they vote. In order to carry out their task of representation, Members shall enjoy immunity.

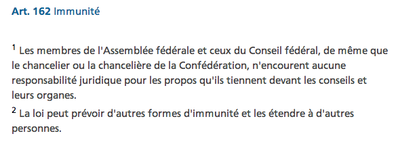

Immunity is a privilege that causes a person, because of a quality of his or her own, to escape a duty, or subjection, that affects others. There are two categories:

- Irresponsibility: immunity by virtue of which the parliamentarian is exempt from any legal action for opinions or votes expressed in the performance of his or her duties.

- Inviolability: protection of the physical and intellectual freedom of parliamentarians as citizens - a member cannot be prosecuted during his or her term of office to avoid interfering with parliamentary debate. It may only be continued with the authorization of the Board of which it is a member.

National Council

Each canton is entitled to at least one seat. The National Council is elected by proportional representation.

Council of States

The method of elections is defined by the cantons. Generally, the system is a two-round majority mode. To exercise certain powers, the Federal Assembly sits and deliberates in a single college.

Not to be confused with the Council of State, the name given to the governments of the French-speaking Swiss cantons: cantonal executive.

The aims and tasks of the Federal Assembly

The Federal Assembly is responsible for all constitutional and foreign affairs revisions (Art. 166 Cst), draws up the budget, approves the accounts, ensures that relations between the Federal State and the cantons are maintained (Art. 172 Cst) and is responsible for the supreme supervision of the Federal Council, the Federal Court and the Federal Administration.

The aim of the Federal Assembly is therefore to make laws in all areas of the Confederation's competence.

Sits in different sessions, some of which may be extraordinary.

During the sessions, members of the Federal Assembly can speak, express their feelings and take decisions. The means at the disposal of parliamentarians are called "referral". This right affects legislation on the one hand and the constitutional domain on the other.

Referral is the action of bringing before a body a question on which it is called upon to rule.

Element 1: PARLIAMENTARY INITIATIVE

- allows a draft legislative act or a general proposal for a proposal for such an act to be submitted to Parliament itself.

2nd element : MOTION

- A parliamentarian may make a motion to introduce a bill or take action. It must be approved by the other board.

3rd element : THE POSTULATE

- Instructs the Federal Council to examine the advisability of either tabling a bill or taking a measure or presenting a report on the subject.

4th element : THE QUESTIONING

- Instructs the Federal Council to provide information.

Element 5: THE QUESTION

- Instructs the Federal Council to provide information on matters concerning the federation.

Element 6 : QUESTION TIME

- The Federal Council answers questions orally.

Over the past four years, parliamentarians have tabled more than 6,000 interventions:

- 400 private members' business;

- 1300 motions;

- 700 postulates;

- 1700 arrests;

- 850 questions;

- 200 - 300 written questions.

The Federal Council also has the right to refer a bill to Parliament.

After the fall of Napoleon, the confederal structure, with the achievements of the revolution, remained in place until 1848.

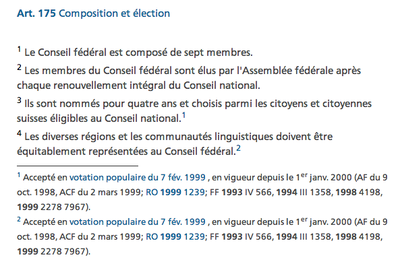

The Federal Council

The Swiss government has seven members, elected for an administrative period of four years by the Federal Assembly (United Chambers). The President of the Confederation is a "prima inter pares" (the first of her peers). It is elected for one year by the combined Houses. It directs the meetings of the Federal Council and performs certain representational functions. The Chancellor of Confederation is in a way the "first secretary" of the government.

- The supreme managerial and executive authority of the confederation.

- Exercises legislative activity through government powers.

- Is elected for 4 years after each full renewal of the National Council (art 175 cst).

Councillors could be compared to the French federal executive and government, they are more than ministers because they embody the executive.

The Federal Council is a coalition council representing most political parties.

When there is a disagreement between the chambers, the people decide whether or not there should be a review. In case of approval by the people who show the need for a revision, at that time the chambers are dissolved leading to new elections.

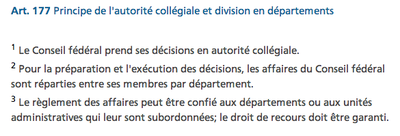

The Federal Council is a collegiate body (art. 177 cst) subject to the formal review of the governmental college by the President of the Confederation.

The 7 members of the Federal Council are equal so that none of them is superior to the others. However, in the event of a tie, the President's votes count as double.

Decisions are taken on behalf of the Federal Council.

Each Federal Councillor is head of the department assigned to him or her and a member of the College Council.

The Federal Council is represented by the country's main parties as a result of an agreement between the major political parties.

It is customary for a member of the Federal Council to be elected President of the Confederation after having served under the chairmanship of all his colleagues before him. It is seniority that is sanctioned-

The presidency has the function of representing the government college either within or outside the country.

The Federal Council is responsible for:

- foreign relations;

- heads Swiss diplomacy;

- proposes the Treaties to Parliament for approval;

- directs the affairs between the Confederation and the cantons;

- take measures to ensure the internal and external protection of the country;

- is in charge of the preliminary phase of the legislative procedure;

- administers the finances of the confederation.

The Federal Chancellery

The Federal Chancellery dates back to 1803 and represents the General Staff, which participates in the deliberations of the Federal Assembly in an advisory capacity.

The Chancellor is appointed by the Federal Assembly and is appointed as a college. The Chancellor of the Confederation has a consultative channel, it does not vote, but participates in the meetings of the Federal Council.

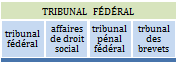

Federal Court

It is the supreme judicial authority of the Confederation. The powers of the Federal Court will be extended at the same time as those of the Confederation. It became a permanent court in 1874 as the cantonal powers were transferred to the confederation.

Composed of three courses:

- the Federal Court itself: Lausanne;

- labour law matters: Lucerne;

- Federal Criminal Court: Bellinzona;

- Patent Court: St. Gallen.

At the confederation level, appeals by the cantonal authorities are subject to review by this supreme judicial authority of the confederation.

To summarize

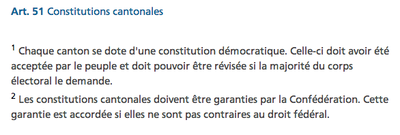

At the cantonal level

Thus, for the application of federal law, he cannot apply it at his own discretion. The cantons must designate the bodies responsible for carrying out federal tasks. The cantons must create institutions and bodies in accordance with federal legislation.

The cantons enjoy a certain degree of autonomy: this is reflected in the freedom that the cantons have to organise themselves and to distribute cantonal power among the bodies they set up. However, their action is limited by the constitution.

The cantons have a central state organisation and their territory is divided into municipalities.

The central organization has three main bodies:

1. The Legislative Assembly - Great Council, Parliament

- Its membership ranges from 55 members to 200 in Bern. Members of the federal parliament have immunities that allow them to fully carry out their duties as members of parliament, as do members of the federal chambers, who also enjoy immunity from irresponsibility. the parliament sets taxes and the budget vote. Like federal parliamentarians, they are not so-called "professional" parliamentarians.

2. The collegial executive

- The cantons have a collegiate executive that is elected by the people of the canton by a majority vote; they are composed of 5 or 10 people and are elected by the citizens of the cantons by a majority vote. In some cantons there are still militia governments. As in the Federal Council, the members of this cantonal government executive are each at the head of a department.

The President of the government chosen from among the members of the executive may be appointed:

- or by the people;

- or by the Grand Council;

- or by the Council of State (Geneva).

The attributions is the superior executive authority of the canton, it supervises the administrations and appoints the cantonal civil servants. On the other hand, he represents the canton outside the canton.

Power is vested collectively, which implies a certain honesty and intellectual probity.

3. The courts

- Civil and criminal proceedings are the domain of the federal state. Each canton has courts that are organized in a relatively diverse way. For this purpose, it is necessary to refer to the cantonal judicial laws.

At the municipal level

The municipality determines our presence in a canton. The tasks are divided between three levels: federal, cantonal, communal. Small municipalities that do not necessarily have enough structures often decide to group together in order to better manage the territory. At the time, the cantons and the federation did not exist, the municipality of Berne for example is very old, more so than its canton or the federation. Some of the municipalities are therefore very old. There are a total of 2324 municipalities in Switzerland, but the number of these municipalities is decreasing. They are grouping together to manage increasingly complex tasks. In the canton of Basel-Stadt, there are 3 municipalities compared to 180 in Graubünden, for example. Some municipalities such as Zurich are huge (more than 400,000 inhabitants) while others have only a few hundred inhabitants. There is therefore a difference in financial assistance following population variations.

Municipalities are public-law entities, they are governed by cantonal law and not federal law, so cantonal legislation takes precedence. There is a different organization from one municipality to another according to the legislation of the canton.

The organization of municipalities is done in Switzerland in two ways:

- For some, the organization is bipartite, with two bodies. There is the communal electoral body that exercises "legislative" powers in a communal (or primary) assembly. The entire electorate (each citizen) is part of the communal assembly and can participate in it by simply presenting the ballot paper. Besides that, we have an elected executive council. This organisation is specific to the smallest municipalities, as populated municipalities and cities would have organisational problems with this system.

- Most cantons and large cities have a tripartite organization. Here the electorate elects its representatives:

- dans l’exécutif communal (nommé conseil communal, conseil administratif ou municipalité selon les localités). C’est le conseil exécutif, il est identique à celui du système bipartite.

- au Parlement communal (nommé conseil général, communal, municipal). C’est l’organe législatif, il remplace l’assemblée communale de l’organisation bipartite.

Selon les communes, l’organe exécutif et législatif peuvent avoir des noms différents, le conseil communal est l’exécutif en Valais ou dans le canton de Fribourg et il est le législatif dans le canton de Vaud.

Il n’y a pas de pouvoir judiciaire au niveau communal.

Le conseil exécutif est un organe collégial élu par le corps électoral. À sa tête se trouve le président (maire) qui exerce sa fonction, souvent à plein temps. L’administration varie selon la taille de la commune.

L’exécutif communal rédige les projets d’actes législatifs qui seront débattus et adoptés (ou non) par le parlement communal ou l’assemblée communale

La démocratie

Qu’est-ce que la démocratie ? C’est le régime politique dans lequel le pouvoir est attribué au peuple qui l’exerce lui-même ou par l’intermédiaire des représentants qu’il élit.

Le régime politique et la forme de gouvernement d’un État.

La démocratie directe est le régime dans lequel le peuple, sans intermédiaire, adopte lui-même les lois et décisions importantes et choisit lui-même les agents d’exécution. Ce régime n’existe plus qu’à Glaris et a Appenzell Rhodes-Intérieures.

La démocratie indirecte ou représentative est le régime dans lequel le rôle du peuple se borne à élire des représentants.

- À l’échelon fédéral, il n’y a pas de démocratie directe

- À l’échelon cantonal, la démocratie directe existe (ex- landsgemeinde de Glaris)

- À l’échelon communal : démocratie directe à travers les assemblées communales

Le régime politique de démocratie semi-directe

La démocratie peut être semi-directe, c’est-à-dire qu’elle est normalement exercée par des représentants, mais les citoyens peuvent intervenir dans son exercice par le referendum et l’initiative.

Le régime politique de la démocratie directe

La démocratie directe est un régime dans lequel le peuple, sans intermédiaire, adopte lui-même les lois et décisions importantes et choisit lui-même les agents d’exécution.

En Suisse, la démocratie est le régime politique qui fait du peuple le souverain.

Le souverain, tant en matière législative que constitutionnelle exerce la démocratie à tous les niveaux.

- Élection populaire: caractérisé par le choix de la représentation populaire- C’est le peuple qui procède à l’élection de ceux qui vont le représenter.

- referendum populaire : permet au peuple de se prononcer sur un acte adopté par une autorité étatique, le plus souvent le parlement. Cet acte peut être constitutionnel ou législatif. Il est prévu par la législation pour les révisions constitutionnelles, l’adhésion à des organisations supranationales ou de sécurité collective, mais aussi pour les lois fédérales déclarées urgentes n’ayant pas de base constitutionnelle.

- referendum obligatoire : procédure qui soumet obligatoirement au scrutin populaire un objet en principe après son adoption par l’organe parlementaire. Il est prévu pour l’adhésion de la Suisse à des organisations supranationales et de sécurité collective (Art.140. cst)

- referendum facultatif : si 50 000 citoyens et citoyennes ayant le droit de vote ou huit cantons le demandent dans les 100 jours à compter de la publication officielle de l’acte, sont soumis au vote du peuple : les lois fédérales, les lois fédérales déclarées urgentes, les arrêtés fédéraux, les traités internationaux (Art. 141, cst). Dans ce domaine facultatif, le fédéralisme n’intervient pas, ce n’est que le peuple qui décide, il n’y a pas la double majorité ; ainsi le referendum facultatif prend aussi lieu dans les communes.

- initiative populaire : il confère à une fraction du corps électoral soit 100 000 citoyens une mesure, qui permet de conduire à l’abrogation d’un acte normatif. (ex-révision de la constitution). En droit fédéral, l’initiative ne peut être que constitutionnelle.

Certaines landsgemeindes qui est l’assemblée souveraine sont une assemblée publique de tous les souverains actifs du canton qui se regroupe généralement au printemps sur une place publique du chef-lieu du canton, elle est présidée par la landsgemeinde. Ces assemblées détiennent aussi la compétence de :

- nominer les hauts fonctionnaires ;

- élire les magistrats des tribunaux ;

- décider de certaines dépenses ;

- voter les traités ;

- voter les lois ;

- prendre des décisions administratives importantes.

Cette assemblée permet la participation aux décisions de la commune.

Actuellement, ce régime de démocratie n’est maintenu que dans deux cantons :

- Glaris ;

- Appenzell Rhodes intérieure.

Le régime de la démocratie directe est cependant toujours représenté dans une majorité de communes à l’échelon communal et notamment dans le système bipartite. L’Assemblée communale délibère publiquement.

La neutralité

William Emmanuel Rappard

William Emmanuel Rappard est né à New York en 1883 et décède à Genève en 1958, il fut notamment professeur, recteur et diplomate suisse. Défenseur de la neutralité suisse.

Jeunesse

Né d’une famille thurgovienne qui vivait aux États-Unis à New York d’un père négociant en broderie et d’une mère travaillant dans son entreprise pharmaceutique familiale. Il passa son enfance et le début de son adolescence aux États-Unis. La famille Rappard quitta les USA pour s’installer à Genève où William termina son cursus scolaire et entama son parcours académique.

Études

Étudiant, il a fréquenté de nombreuses universités : à Paris, il a été l’élève d’Adolphe Landry (1874-1956) qui, semble-t-il, l’a marqué et d’Halévy ; en Allemagne, à Berlin, il a suivi les cours de Wagner et de Schmoller, à Harvard, de Taussig et à Vienne de Philippovich qui l’a encouragé à s’intéresser à l’Organisation internationale du Travail.

Vie active

Professeur assistant à Harvard de 1911 à 1912, il est nommé en 1913 professeur d’histoire économique à l’Université de Genève. Ami d’Abbott Lawrence Lowell, président de Harvard de 1909 à 1933, connaissant le colonel House et Walter Lippmann, il a joué un rôle important dans l’attribution du siège de la Société des Nations à Genève. Il présida la commission des mandats de la Société des Nations. Il travailla aussi en tant que juriste. Il possédait donc une formation pluridisciplinaire.

En 1927, il fonda l’Institut Universitaire de Hautes Études internationales de Genève, il y accueillit de nombreux réfugiés en provenance des États totalitaires voisins. Il fut également membre dans les années trente du “Comité international pour le placement des intellectuels réfugiés”. Il fut aussi recteur de l’université de Genève à 2 reprises.

En 1942, le Conseil fédéral le désigne comme interlocuteur pour d’importantes négociations (entre autres renouer les relations avec les pays alliés), alors qu’il n’est pas fonctionnaire fédéral, mais professeur à l’université. Il plaidera également pour le retour des organisations internationales à Genève.

À la fin des années trente, il s’opposa à la fondation Rockefeller qui aurait voulu que l’IUHEI se consacre aux études économiques et abandonne l’enseignement comme l’avait fait la Brookings Institution. À cette occasion, il reçut le soutien de Lionel Robbins qui le tenait en haute estime. Membre de la délégation suisse auprès de l’OIT de 1945 à 1956. Un des fondateurs de la Société du Mont-Pèlerin.

Sa bibliographie touche au droit, à l’histoire, à la statistique ainsi qu’aux relations internationales. Rappard a abordé la neutralité en tant que chercheur et en tant qu’acteur.

La neutralité de la Suisse, des origines au XXème siècle

Pour Rappard, le terme neutralité ne suscite pas l’enthousiasme. Il relève, « en français, l’adjectif neutre rime trop bien avec l’épithète pleutre avec laquelle il est souvent accouplé pour ne pas subir d’emblée une véritable dépréciation ; de plus il sert aux biologistes à définir les organes asexués, les chimistes les substances sans saveur. La neutralité est l’attitude d’un pays qui refuse ou de s’interdire d’intervenir dans les conflits qui opposent les uns aux autres les États tiers ».

La neutralité est l’aptitude d’un pays qui refuse ou s’interdit de s’opposer à des conflits qui impliquent des pays tiers.

L’historien Rappard montre que cette politique de neutralité remonte à Marignan conférence. La neutralité remonte à la défaite de Marignan en 1515 lorsque les Suisses ont été battus par François Ier. C’est alors que la neutralité est devenue le principe directeur de la politique étrangère suisse.

À l’époque, la Suisse avait deux possibilités pour assurer son existence :

- soit s’allier à la France des Bourbons soit à l’Autriche des Habsbourg, le risque étant de devenir sujet de l’un de ces deux pays ;

- soit s’abstenir de toute intervention dans les guerres continuelles entre la France et l’Autriche.

Ainsi, la neutralité était une manière pour les Suisses de maintenir leur indépendance.

Après la réforme, la neutralité va être une manière de maintenir les confédérés. En s’alliant étroitement avec les coreligionnaires étrangers, la Suisse risquait d’éclater. Le principe de neutralité élaboré dans le conflit entre l’Autriche et la France va être également utilisé dans le domaine religieux.

La neutralité suisse devint un principe ayant pour but d’assurer la sécurité extérieure, mais aussi de préserver la sécurité intérieure afin d’éviter que des conflits confessionnels ne viennent faire éclater l’unité.

Cette politique de neutralité poursuivie au cours des siècles était aussi conforme à l’intérêt des belligérants. La guerre de la ligue des Habsbourg menaçait les frontières de la confédération, Louis XIV et Léopold Ier avaient engagé les Suisses à défendre leur territoire contre d’éventuelles incursions de leurs ennemies. Cependant, les Suisses vont demander que les Français et Autrichiens participent aux frais de mobilisations ; ils s’exécutèrent.

Ainsi, la neutralité devint un élément essentiel du patrimoine institutionnel des confédérés jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe siècle.

À la chute de Napoléon, ce statut est de nouveau reconnu le 20 novembre 1815 : la neutralité et l’indépendance de la Suisse sont dans les brefs intérêts de l’Europe entière. L’acte du 20 novembre 1815 qui est un traité international signé par les puissances européennes disait « la neutralité et l’inviolabilité de la Suisse et son indépendance de toute influence étrangère sont dans le vrai intérêt de l’Europe tout entière ».

Durant tout le XIXème siècle, la Suisse va maintenir sa politique de neutralité.

The War of 1914 - 1918

Switzerland is divided in two:

- the German Germans are in favour of the German Empire and William II;

- the French-speaking Romans are outraged by the atrocities and the violation of Belgium's neutrality by German troops.

Rappard will intervene in the political debate to defend neutrality, denounces the dangers that potentially call into question Switzerland's neutrality. It works to ensure that the divided Swiss remain united in their desire to remain outside the external conflict, ready to defend the nation against any aggressor.

In 1917, Rappard was sent to the United States to make neutral Switzerland heard and ensure its supply. The interviews and interviews he has with journalists and those around him will enable him to promote Switzerland's interests and its principle of neutrality.

It shows that the Swiss need political support as much as the economic support of the United States, succeeding in rallying American opinion.

During his meeting with Wilson, Reminder to the presence of mind to remind the President of the United States of the passages he had devoted in one of his books to Switzerland, namely the principle of mutual assistance, respect for the freedoms of each other and mutual tolerance.

The evocation of his book places Wilson on an expensive ground exposing his drawing of a new world order: the future of Switzerland depends on the future of Europe.

Rappard suggests a statement by the United States suggesting Switzerland's neutrality. On December 5, 1917, the United States recognized Swiss neutrality and undertook to supply wheat.

In 1918, during another one-on-one meeting with President Wilson, they decided that the League of Nations must be born of peace. Only peace-making nations will be admitted to the negotiating table. As Switzerland is not a belligerent, it will not be able to join the League of Nations until after its creation.

The Peace Conference

Work began in Paris in 1919 to create the League of Nations. In order for Switzerland to be informed about the debates, Rappard is the unofficial envoy of the Swiss, as it cannot participate in the negotiations setting up the Charter of the League of Nations.

These contacts with the Allied delegations and particularly with the American delegation will contribute to the designation of Geneva as the seat of the League of Nations and to Switzerland's entry with its neutral status.

The allies consider that a status of neutrality cannot find its place in the League of Nations forming a new international order based on law.

The allies are against the status of neutrality, because in the new world order, neutrality undermines global solidarity.

Rappard proposes to the Federal Council that the maintenance of Swiss neutrality is in the interest of the international community: he advises the Federal Council against making membership conditional on the recognition of neutrality.

At the end of January 1919, rumours spread in Paris that Geneva would be the future headquarters of the League of Nations. This would create a special status for the host country, which would be one of neutrality without having the name.

However, in April 1919, the Allies did not support the creation of a special status.

Max Huber, a lawyer from the Federal Political Department, currently known as the Department of Foreign Affairs, came to Paris with the idea that Switzerland's guarantee of neutrality could be interpreted in the light of Article 21 "international commitments, such as arbitration treaties, and regional agreements, such as the Monroe doctrine, which ensure peacekeeping, shall not be considered incompatible with any of the provisions of the present Covenant".

It was essential that Switzerland obtain a special status or else the Swiss people will refuse to enter the League of Nations categorically. Rappard spoke with Wilson recalling that if Switzerland was to join the League of Nations, the people and the cantons would have to vote.

On 28 April, the Peace Conference, meeting at Quai d'Orsay, made Geneva the seat of the League of Nations, excluding Brussels and The Hague.

However, no positive assurances can be given regarding the special status of the host country. Rappard believes that Switzerland can hope at best to be accepted by the allies in the League of Nations without opposing the maintenance of neutrality resulting from the interpretation of Article 21. Finally, Swiss neutrality is recognized, whereas no one expected it anymore.

The 1815 Treaty is a treaty that guaranteed Switzerland's neutrality; in the event of a conflict with the confederation's neighbours, neutrality was to extend to Northern Savoy. At that time, these provinces belonged to the Duke of Savoy, King of Sardinia. This singular situation still persisted in 1919, even though Savoy became French in 1860.

This status of neutrality, which was spreading, did not please the French so much according to the principle of double sovereignty in the event of war.

Max Huber proposes a plan to renounce the neutrality status of Northern Savoy in exchange for the recognition of Swiss neutrality. The abandonment of this status was a favour to France, which in return had the task of having Switzerland's neutrality recognised with an explicit mention so that the people and cantons who will be consulted can give a "frank and massive yes".

The French and Swiss governments will reach an agreement leading to Article 435 of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919:

« The High Contracting Parties, while recognising the guarantees stipulated in favour of Switzerland by the Treaties of 1815 and in particular the Act of 20 November 1815, which constitute international commitments for the maintenance of peace, note, however, that the provisions of these Treaties and Conventions, Declarations and other complementary acts relating to the neutralised zone of Savoy, as determined by paragraph 1 of Article 92 of the Final Act of the Vienna Congress and by paragraph 2 of Article 3 of the Treaty of Paris of 20 November 1815 no longer reflect current circumstances. Consequently, the High Contracting Parties take note of the agreement reached between the Government of France and the Government of Switzerland for the repeal of the provisions relating to this zone which are and remain repealed. »

The President of the French Council who was Clemenceau had no intention towards the League of Nations, but supported the status of Swiss neutrality.

William Rappard campaigned for Switzerland to join the League of Nations, so on 16 May 1920, the majority of Swiss and cantons agreed to join the League of Nations.

As a member of the League of Nations, Switzerland must nevertheless show solidarity with measures taken against a nation that violates another. Nevertheless, military neutrality is maintained, but it remains obliged to adopt financial and economic measures against an outlaw country that violates the Charter of the League of Nations.

The 1930s

The 1930s were to deny the hopes placed in the League of Nations. Rappard is at the heart of the League of Nations as it is the privileged witness of this international evolution.

Rappard denounces the danger to individual freedoms posed by totalitarian regimes.

These states have in common that they have rejected liberal individualism and democracy. The nation replaces the individual, everything is imposed on him except what is forbidden to him.

The international situation favours these dictatorial regimes, which do not have to take into account their public opinion.

« ... how can it be accepted that a regime that denies everyone the freedom to think, write, speak, gather, feed, travel, love, hate, be indignant, enthusiastic, work and relax as they please can generate a race of men as energetic, intelligent, inventive, inventive, truly productive and creative as a regime that respects the rights of the individual? »

— William Rappard

Rappard deplores the lack of universality of the League of Nations and its ability to maintain peace. It had to guarantee the territorial integrity and dependence of all its members through the application of the principle of collective security.

The Japanese aggression against Manchuria, followed by the Italian aggression in Ethiopia, dealt a severe blow to the prestige and credibility of this international organization.

The hope she embodied is a great disappointment. The dangers to Swiss neutrality resulting from this instability lead it to refuse involvement in economic, financial and commercial measures, particularly against Italy.

Rappard then considered that the return to complete neutrality was now the only way for Switzerland to protect itself from the "gangsterism" of totalitarian nations.

Chamberlain declared in February 1938: "the League of Nations in its current form cannot guarantee the safety of the collective, we cannot abandon ourselves to an illusion and mislead the small nations that it would protect, when we know perfectly well that we can expect no recourse from Geneva".

All Switzerland's neighbours leave the League of Nations except France. Rappard considered neutrality to be a "parachute" that Switzerland is not about to abandon it as long as the "airspace" is dangerous.

Thus, in the spring of 1938, Switzerland returned to its traditional policy of complete neutrality, exempting it from any sanctions against other nations. Neutrality will be recognized by all members of the League of Nations and by both Italy and Germany.

After Russia's aggression against Finland and the League of Nations' inaction, Switzerland is distancing itself from its obligations towards the League of Nations.

« If neutrality is never glorious in my eyes, it is because it is the negation of active solidarity that responds to a true organization of peace. In fact, it is clear that the neutrality we practice in Switzerland does not inspire us to give any pretext for intervention by our neighbours to the north and south. »

The Second World War

Switzerland is isolated, surrounded by three dictatorships demanding respect for complete neutrality; Rappard reminding that it is not one of the most glorious "it is no less than ever in a conflict where all rights and all truth are on the one hand and all mistakes and lies are on the other".

Rappard is convinced that the policy of silence is the only one that is now appropriate for Switzerland while helping those suffering from the conflict. The outbreak of the Second World War is an all-out war that also involves an economic war, one of the main weapons of which is the economic blockade.

Neutral Switzerland, surrounded by the Axis powers, will have to defend its supply abroad, consisting mainly of raw materials essential to the country's survival. To counter this blockade, Switzerland will have to negotiate with both the Allies and the Axis powers. The talks will inevitably be influenced by the vagaries of war. Nazi Germany in particular will obtain substantial aid in its economy, provoking the anger of the allies and their blockade against Switzerland.

Switzerland, surrounded by a single belligerent, is the only country that has not been occupied. Rappard notes that neutrality can only be respected if there is a balance between the states surrounding Switzerland. Rappard is trying to fight against an economic and trade policy of the Federal Council that he considers too lax towards Nazi Germany.

Sent to London in 1942, trying to loosen the Allied blockade, Rappard noted that Switzerland enjoyed strong sympathy. He met De Gaulle who was willing towards the confederation, deserving not to have given in to the dictates of the Axis powers. However, the allies are doing their utmost to prevent the delivery of Swiss products to the Axis powers.

« That is why, while agreeing to our supplies to the extent, perhaps reduced, that they are necessary and possible, we want to tighten the economic blockade at our expense. "If you want raw materials to feed your industries and warn you of unemployment," we are constantly told, "reduce your exports of food, machinery and especially weapons and ammunition to our enemies. We understand the needs of your own national defence and we do not ignore the needs of your labour market, but we do not intend to deprive ourselves of our increasingly limited resources in terms of tonnage, raw materials and above all metals, in order to facilitate your task of collaborating indirectly in the destruction of our aircraft, tanks, cities and the loss of our soldiers.[7] »

Rappard explains that it is impossible to hold the allies accountable for this attitude, ensuring that their commitment must silence critics. 2dd must silence their criticism of us.

In 1945, the Allies sent a delegation to Bern to encourage Switzerland to break with Germany. Switzerland must regain its credibility with the allies. Rappard is present during the negotiations, earning the trust of both parties by defending the interests of the allies, but also by pleading Switzerland's cause.

At the end of these negotiations, the Allied delegation was able to see that the Swiss people had not been voluntary accomplices of the Axis, but sympathizers of the Allies' cause.

The post-war period

While the allies were working on the reorganisation of the world, Rappard wondered about Switzerland's neutrality. He considers that the United Nations is not in a position to ensure the security of the new international order. Switzerland's neutrality would be an obstacle to Switzerland's entry into this organization. To avoid isolation, Switzerland works closely with all the UN's technical bodies, whether economic, social or legal. This path advocated by Rappard is the path that the Swiss authorities will follow.

In conclusion, after the First World War, Rappard was first convinced that the differences between the allies would strengthen Switzerland's neutrality. It therefore favoured accession with differential neutrality rather than full neutrality, considering that it would no longer be necessary because of the security created by this new world order. At the end of the Second World War and at the time of the creation of the UN, the Soviet threat dictated, through his experience, that he should not join the United Nations and maintain the Swiss neutrality regime.

Switzerland's obligations must not make the Swiss forget that they cannot derogate from their commitments. The attitude of young Swiss people who see neutrality as cowardice is certainly an indication of a certain generosity, but also due to a lack of historical and political knowledge.

Neutrality was first of all a security so that France would not attack Austria, while France knew that Switzerland's neutrality was a way of protecting itself from the Habsburgs and the Holy Roman Empire. It is on this guarantee that neutrality has been built.

Annexes

- ForumPolitique.com : La politique en Suisse

- Traité de Versailles

- Le dernier mot au peuple (1874)

- Quel est le contenu du droit de neutralité ?

- Monnet, Vincent. Willliam Rappard, l’homme de l’Atlantique. Université de Genève, Campus N°96. Url: http://www.unige.ch/communication/Campus/campus96/tetechercheuse/0tete.pdf

References

- ↑ Publication de Victor Monnier repertoriées sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Hommage à Victor Monnier sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Publications de Victor Monnier sur Cairn.info

- ↑ Publications de Victor Monnier sur Openedition.org

- ↑ Page personnelle de Victor Monnier sur le site de l'Université de Aix-Marseille

- ↑ En Hommage À Victor Monnier.” Hommages.ch, 11 Mar. 2019, www.hommages.ch/Defunt/119766/Victor_MONNIER.

- ↑ Professor W. Rappard to the Head of the Department of Public Economy, W. Stampf, London, 1 June 1942 (Member of the Swiss delegation in London) url: http://www.amtsdruckschriften.bar.admin.ch/viewOrigDoc.do?ID=60006477