« Financial Market » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 153 : | Ligne 153 : | ||

[[Fichier:Intromacro bulle immobiliere usa 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Intromacro bulle immobiliere usa 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | ||

= | = Savings and investment: national balance = | ||

== | == National balance == | ||

Let us consider the case of a closed economy, an economy without any exchange with the rest of the world. The national accounts identity <math>Y \equiv C + I + G + EXP - IMP</math> (EXP and IMP, respectively, for exports and imports) then turns into the following : | |||

::<math>Y = C + I + G</math> | ::<math>Y = C + I + G</math> | ||

where <math>Y</math> represents GDP, <math>C</math> consumption, <math>I</math> investment and <math>G</math> public expenditure. (NB: the previous equation represents at the same time the equilibrium condition of the economic system and the identity of the national accounts, which is always verified ex-post). | |||

The national income accounting identity can be rewritten as: <math>Y - C - G = I</math> | |||

The term <math>Y - C - G</math> refers to production that remains after consumer and government demand has been met. This is called ''national savings'' and is indicated with the letter <math>S</math>. At equilibrium, <math>S = I</math>. | |||

In more detail, being <math>T</math> taxes, total savings is equal to the sum of private savings <math>S_p = (Y - T - C)</math>, and public savings, <math>SG = (T - G)</math>. (NB: if <math>T > G</math> → public savings; if <math>T < G</math> → public deficit) | |||

By introducing <math>T</math> in our equilibrium equation, we have <math>Y - C - T - G + T = I</math> ⇒ the macroeconomic equilibrium condition becomes : | |||

::<math>S = (Y - T - C) + (T - G) = SP + SG = I</math> | ::<math>S = (Y - T - C) + (T - G) = SP + SG = I</math> | ||

At any given moment in a closed economy, private savings finance investment and the eventual public deficit : | |||

::<math>SP = I + SG = I + (G-T)</math>. | ::<math>SP = I + SG = I + (G-T)</math>. | ||

Version du 27 mars 2020 à 11:25

| Professeur(s) | |

|---|---|

| Cours | Introduction à la macroéconomie |

Lectures

- Aspects introductifs de la macroéconomie

- Le Produit Intérieur Brut (PIB)

- L'indice des prix à la consommation (IPC)

- Production et croissance économique

- Chômage

- Marché financier

- Le système monétaire

- Croissance monétaire et inflation

- La macroéconomie ouverte : concepts de base

- La macroéconomie ouverte: le taux de change

- Equilibre en économie ouverte

- L'approche keynésienne et le modèle IS-LM

- Demande et offre agrégée

- L'impact des politiques monétaires et fiscales

- Trade-off entre inflation et chômage

- La réaction à la crise financière de 2008 et la coopération internationale

This chapter explores the importance of financial institutions (financial markets and financial intermediaries) to the economy.

The functioning of the financial system affects two major macroeconomic variables that, in turn, are important determinants of productivity :

- savings () → offers loanable funds;

- investment () → demand for loanable funds.

The demand and supply of loanable funds make it possible to establish the conditions under which the economy is in equilibrium.

At the end of the chapter we will see how government policies can encourage savings and investment.

Financial Institutions

The financial institutions

The main role of financial institutions is to allocate capital (one of the scarce resources in the economy) from savers (supply) to investors who need it (demand) → market for loanable funds (or capital).

They are grouped into two categories:

- the financial markets:

- the bond market;

- the equity market.

- financial intermediaries :

- banks;

- Mutual funds.

Through the financial markets, savers make their capital directly available to investors.

Through financial intermediaries, savers indirectly make their capital available to investors.

Bonds

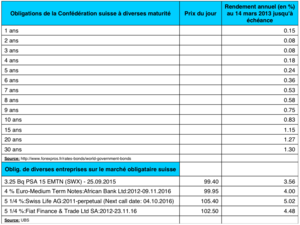

A bond is an acknowledgement of debt owed by a company (or government) to the holder of the bond. The company borrows directly from the public without going through the banking system. There are two essential characteristics of a bond:

- the term of the bond (expiry date);

- the signature risk (or probability of non-repayment).

These two characteristics will determine the fixed interest (or coupon) that will be paid for this loan: "junk bonds" (very risky bonds) pay more than government bonds and a 10-year bond pays a higher interest than a 1-year bond.

The price of a bond will be determined by the market according to the term, the signature risk and the nominal market interest rate. Ceteris paribus, if the market interest rate decreases, the price of the bond increases. There is an inverse relationship between market interest and price, the market rate being the yield on new issue bonds.

Financial rating scale according to major rating agencies

Junk bond" (or "high-yield debt"), also called "junk bond" in French, is the colloquial name for high-risk bonds in the United States, bonds that are classified as "speculative" by the rating agencies, i.e. those with a financial rating below investment grade.

The existence of a separate but active market for these bonds stems from two particularities of the US financial system :

- the use of direct capital market fundraising has been common among large US SMEs since the late 1970s, much more so than in Europe, where the financing of this type of business is still mainly carried out by banks;

- At the same time, many institutional investors are prohibited by internal or external regulations from holding assets that are not investment grade.

For issuers, this type of financing is cheaper than bank loans.

Junk bonds ?

The evolution of the price

This graph shows the evolution of the market price of Greek bonds with a July 2019 maturity giving a nominal interest rate of 6% between March 2009 and March 2010. The evolution of the spread in relation to German bonds can be seen online.

Les actions

A share is a partial title of ownership in a company entitling the holder to a corresponding share of the profits made in the future and in principle also to a right to vote at the shareholders' meeting. In other words, a share is a title deed issued by a corporation (e.g. a public limited company or a company limited by shares). It confers on its holder the ownership of a part of the capital, with the associated rights: to intervene in the management of the company and to receive an income called a dividend.[11].

The holder of shares qualifies as a shareholder and the shareholders as a whole constitute the shareholding.

If Nestlé has issued a total of 1 million shares, each share corresponds to 1 millionth of its future profits.

The share price is determined on the stock market (LSE, NYSE...).

Generally, a share implies more risk than a bond, and therefore a higher average return.

Price of the day and minimum and maximum of the day and/or over the year

Newspaper information :

- Volume: the amount of shares that were traded in the previous session.

- Price change at the last session

- Dividend ratio: the amount of earnings distributed to shareholders as a percentage of the share value (= return on equity).

- Price/Earning ratio (P/E) or cost/benefit: the ratio between the share price and total earnings per share (= share value). Historically a value of 15 is considered normal. If this ratio is higher, it means that the market expects an acceleration of earnings and if it is lower, it means that the market expects a decrease in future earnings.

Financial Intermediaries

Not all companies can issue shares or bonds. There are intermediaries that link investors and savers. These are financial intermediaries such as banks or mutual funds.

Banks take deposits from savers and use them to make loans to investors, but they also pay interest to savers that is slightly lower than the interest they charge to borrowers (profit margin for the bank).

Mutual funds sell units to the public and then buy a portfolio of different types of stocks and bonds. This allows individuals with limited budgets to diversify their portfolio of financial assets.

There are also pension funds, insurance companies...

Asset prices: analysis of fundamentals

What price should a share have?

First method of price evaluation: analysis of the fundamentals, i.e. the determinants (there are many!) underlying the company's future profits (type of sector, degree of competition, unionized or non-unionized workers, etc.). Under the hypothesis of efficient markets and rational agents, all publicly available information concerning the fundamentals of a firm is already incorporated in the share price (a margin between the market price and the value suggested by the analysis of the fundamentals indicates a profit opportunity that has not been exploited) => if the markets are efficient, at any time the share prices are correctly valued (no systematic over- or underestimation).

Consequence: asset prices only change in response to new and unpredictable information about fundamentals => the evolution of stock prices will follow a random path (evolution over time of an unpredictable variable).

Irrational markets

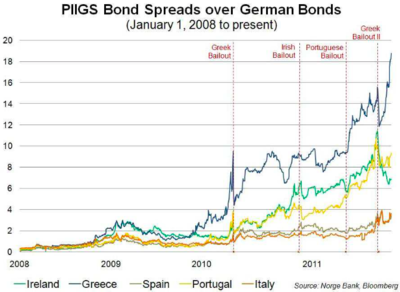

The market efficiency hypothesis is strongly criticised by many economists: evidence of systematic market price disruption (in some cases prices fluctuate much more than would be justified by changes in fundamentals) or irrational behaviour by investors who, for example, rather than analysing fundamentals, simply look at past movements in a stock's value and expect them to continue in the future.

Risk of sharp fluctuations in share prices, sometimes leading to major economic problems. Two recent examples:

- The new technology (or Internet) bubble that burst at the end of the 1990s: share prices on the new technology market are difficult to justify → With the bursting of the bubble, shares lost 2/3 of their value → crisis 2001 → high unemployment.

- The real estate bubble (see below), which caused the last economic crisis (NB: the same type of fears for the Geneva real estate market today).

USA Real Estate Bubble

Between 2000 and 2006 huge increase in house prices in the USA: in 2006 house prices in large cities more than twice as much as in 2000.

According to a number of economists this price increase was excessive and was due to unrealistic expectations about future prices. According to others (including Alan Greenspan, Governor of the Federal Reserve), it was in line with the fundamentals and therefore perfectly justified.

The former were right → huge bubble at the national level → property prices are falling → huge economic difficulties and crisis (we will see a little later how the property bubble spread to the economic system).

Savings and investment: national balance

National balance

Let us consider the case of a closed economy, an economy without any exchange with the rest of the world. The national accounts identity (EXP and IMP, respectively, for exports and imports) then turns into the following :

where represents GDP, consumption, investment and public expenditure. (NB: the previous equation represents at the same time the equilibrium condition of the economic system and the identity of the national accounts, which is always verified ex-post).

The national income accounting identity can be rewritten as:

The term refers to production that remains after consumer and government demand has been met. This is called national savings and is indicated with the letter . At equilibrium, .

In more detail, being taxes, total savings is equal to the sum of private savings , and public savings, . (NB: if → public savings; if → public deficit)

By introducing in our equilibrium equation, we have ⇒ the macroeconomic equilibrium condition becomes :

At any given moment in a closed economy, private savings finance investment and the eventual public deficit :

- .

Les décisions d’épargne et d’investissement

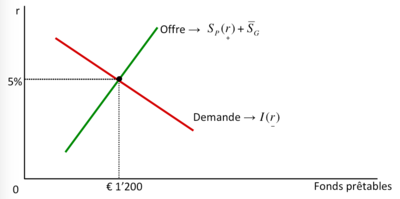

L’identité de comptabilité nationale montre qu’à tout moment l’épargne est égale à l’investissement: . Le marché financier coordonne l’épargne et l’investissement sur le marché des fonds prêtables, le marché où ceux qui épargnent offrent des prêts et ceux qui investissent demandent des emprunts.

L’offre de fonds prêtables émane principalement des décisions des ménages qui décident d’épargner une partie de leur revenu et de la prêter sur le marché financier.

La demande de fonds prêtables émane des décisions des ménages et des entreprises qui décident d’emprunter des fonds pour financer leurs décisions d’investissement.

Le taux d’intérêt réel () est le prix d’un prêt: il représente ce que les demandeurs d’emprunts paient et ce que les offrants reçoivent pour les prêts → demande de fonds prêtables décroissante et offre croissante.

La détermination du taux d’intérêt réel

Le marché financier fonctionne comme tous les autres marchés de l’économie: l’équilibre entre la demande et l’offre pour les fonds prêtables détermine le taux d’intérêt réel d’équilibre. Au taux d’intérêt d’équilibre, les ménages souhaitent épargner ce que les entreprises désirent investir et l’offre des fonds est égale à la demande.

Plus la rémunération sur les prêts est élevée, plus on a une incitation à épargner => offre de fonds croissante.

Plus les emprunts sont chers, moins d'investissements on finance => demande de fonds décroissante.

Politiques gouvernementales influençant S et I

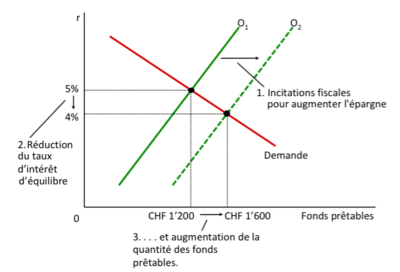

Taxes sur le revenu: une baisse des impôts sur le revenu découlant des intérêts donne une incitation aux ménages à épargner plus ⇒ à parité de taux d’intérêt la courbe d’offre de fonds se déplace vers la droite, le taux d’intérêt d’équilibre diminue et la quantité de fonds d’équilibre (et donc d’investissement) augmente (cf. graphique)

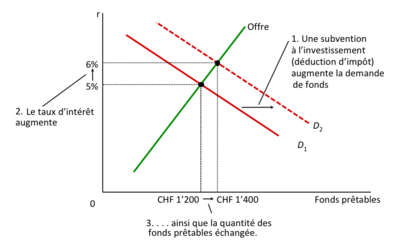

Impôts sur l’investissement: une réduction de l’imposition des investissements en capital neuf (sous forme d’un crédit d’impôt, par exemple) fait déplacer la courbe de demande de fonds vers l’extérieur ⇒ le taux d’intérêt d’équilibre s’accroît et la quantité de fonds d’équilibre (et donc d’épargne) augmente (cf. graphique).

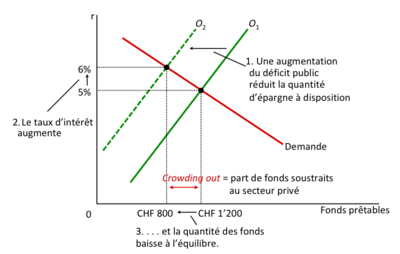

Politiques budgétaires: si → déficit. Le cumul des déficits publics s’appelle dette publique. Quand le gouvernement finance la dépense publique par la dette, il emprunte des fonds pour couvrir son déficit et réduit les fonds prêtables disponibles pour financer les investissements du secteur privé (crowding-out ou éviction de l’épargne privée) ⇒ à parité de taux d’intérêt la courbe d’offre de fonds se déplace vers la gauche, le taux d’intérêt d’équilibre augmente et la quantité de fonds d’équilibre (et donc d’investissement) baisse (cf. graphique).

Incitation à l’épargne

Problèmes liés aux mesures d'incitation à l'épargne :

- Problème potentiel d’équité: une baisse des taxes sur l’épargne favorise d’avantage les individus plus riches (qui épargnent une plus grande partie de revenu). Pour cette raison certains économistes suggèrent de remplacer cette mesure avec une baisse d’impôts sur le revenu.

- Manque de réactivité des décisions d'épargne: l'épargne pourrait être peu sensible aux variations du taux d'intérêt car l'effet de revenu pourrait agir dans la direction opposée à l'effet de substitution (cf. cours de microéconomie). Suite à une hausse des gains découlant des intérêts (due à une réduction des taxes sur le revenu découlant des intérêts), l'effet de substitution pousse les ménages à épargner plus et consommer moins, mais un intérêt plus élevé implique un revenu plus élevé pour un certain niveau d'épargne, ce qui pourrait inciter les individus à consommer davantage et à épargner moins (effet de revenu). D'un point de vue empirique ces deux effets semblent se compenser (dans ce cas la courbe d'offre ne se déplace pas, ou se déplace peu, vers la droite).

Subventions à l’investissement

Déficit public et "crowding out"

L'effet d'éviction est une baisse de l'investissement et de la consommation privée qui est provoquée par une hausse des dépenses publiques.

L'effet d'éviction est d'une manière générale la conséquence de l'extension des activités du secteur public au détriment du secteur privé. Sous ce terme sont pointés — souvent par des auteurs économistes classiques — les excès d'un interventionnisme d'État qui entraverait, voire « évincerait » le secteur privé de certaines de ses possibilités d'action. Les économistes libéraux notamment utilisent cet argument pour critiquer les politiques budgétaires expansionnistes.[12]

Résumé

Le système financier est constitué par des institutions financières telles que les marchés financiers (marchés des actions et des obligations) et des intermédiaires financiers (les banques et les fonds mutuels). Son objectif est d’allouer l’épargne à l’investissement.

Sous l’hypothèse d’efficience des marchés, toutes les informations disponibles publiquement concernant les fondamentaux d’une entreprise sont déjà incorporés dans le prix des actions. Selon un certain nombre d’économistes, en réalité, l’hypothèse de marchés financiers efficients n’est pas vérifiée. Ceci est à l’origine de difficultés économiques très graves.

Dans une économie fermée, l’épargne privée sert à financer l’investissement privé et le déficit public.

Le taux d’intérêt est déterminé par l’offre et la demande de fonds prêtables. L’offre de fonds prêtables provient généralement des ménages qui épargnent une partie de leur revenu.

La demande de fonds prêtables provient généralement des ménages et des entreprises qui veulent emprunter pour pouvoir investir.

Un déficit public réduit l’épargne privée à disposition des emprunteurs et donc réduit l’offre de fonds prêtables. Cela conduit normalement à un taux d’intérêt d’équilibre plus élevé et moins de fonds prêtables. Quand le déficit public réduit l’investissement privé (crowding out) cela réduit la productivité et la croissance.

Annexes

- Efficiency and beyond, The Economist, 16.07.2009

- In defence of the dismal science, The Economist, 06.08.2009 (la réponse de Robert Lucas à l’article précédent)

References

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Neuchâtel

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur Research Gate

- ↑ Researchgate.net - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Google Scholar - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ VOX, CEPR Policy Portal - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Nicolas Maystre's webpage

- ↑ Cairn.ingo - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Linkedin - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Academia.edu - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Action (finance). (2014, septembre 19). Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Page consultée le 01:06, décembre 29, 2014 à partir de http://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Action_(finance)&oldid=107568289.

- ↑ Effet d'éviction. (2014, septembre 17). Wikipédia, l'encyclopédie libre. Page consultée le 11:31, décembre 21, 2014 à partir de http://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Effet_d%27%C3%A9viction&oldid=107535591.