不断变化的工作方法: 十九世纪末至二十世纪中叶不断演变的生产关系

根据米歇尔-奥利斯(Michel Oris)的课程改编[1][2]

地结构与乡村社会: 前工业化时期欧洲农民分析 ● 旧政体的人口制度:平衡状态 ● 十八世纪社会经济结构的演变: 从旧制度到现代性 ● 英国工业革命的起源和原因] ● 工业革命的结构机制 ● 工业革命在欧洲大陆的传播 ● 欧洲以外的工业革命:美国和日本 ● 工业革命的社会成本 ● 第一次全球化周期阶段的历史分析 ● 各国市场的动态和产品贸易的全球化 ● 全球移民体系的形成 ● 货币市场全球化的动态和影响:英国和法国的核心作用 ● 工业革命时期社会结构和社会关系的变革 ● 第三世界的起源和殖民化的影响 ● 第三世界的失败与障碍 ● 不断变化的工作方法: 十九世纪末至二十世纪中叶不断演变的生产关系 ● 西方经济的黄金时代: 辉煌三十年(1945-1973 年) ● 变化中的世界经济:1973-2007 年 ● 福利国家的挑战 ● 围绕殖民化:对发展的担忧和希望 ● 断裂的时代:国际经济的挑战与机遇 ● 全球化与 "第三世界 "的发展模式

19 世纪末至 20 世纪中叶的生产关系变革是塑造现代世界的迷人时期。这个时代的特点是工业方法的快速演变,从传统的手工业和小企业到高度合理化的大规模生产。从对劳动力流动进行细致分析的泰勒主义,到提高工资和增加消费的福特主义,社会结构发生了深刻的变化。在本导论中,我们将探讨生产关系的组织不仅如何彻底改变了制造业和贸易,还如何重塑了经济和社会格局,为战后的繁荣和消费主义奠定了基础。我们将研究技术进步、薪酬战略和消费模式之间的动态关系,它们共同创造了经济增长的良性循环,在二十世纪上半叶主导了西方。

生产关系的组织动态

工业革命标志着生产关系组织的重大变革,企业规模和雇主与雇员之间的关系发生了显著变化。

工业革命初期,企业规模普遍较小。这种适度的规模促进了雇主和雇员之间的密切关系。企业结构简单,中间环节少,能够直接沟通并快速决策。此外,许多企业都是手工业的延伸,手工劳动和特定技能受到高度重视。随着工业革命的推进,企业开始扩张,导致其组织结构发生重大变化。这种增长主要是由制成品需求的增加、技术进步和市场扩大所驱动的。这种演变导致企业管理日益复杂。

随着公司规模的扩大,也需要更多层次的管理和监督。新的中间角色应运而生,在组织结构中形成了更加明显的等级制度。这种层级化扩大了员工与企业主或高级管理人员之间的差距,使工作关系变得更加不近人情和不那么直接。工业化还促进了生产流程的标准化和更严格的劳动分工。工作变得更加重复,技术含量越来越低,工人的自主性往往被削弱。这些变化不仅对生产方式,而且对工作关系的性质产生了深远影响,持久地改变了工作环境。

这些发展对工作条件、阶级关系和社会面貌产生了相当大的影响,反映了时代的动态变化。

工程师的崛起与工作重组

从十九世纪七八十年代开始,随着工程师在决策和技术岗位上的崛起,工业发生了重大变化。他们在技术和生产工艺方面的专业知识使他们成为工业企业中不可或缺的人才。他们不仅参与技术方面的工作,还参与运营决策,成为公司日常管理和运营的核心人物。在这一时期,工程师将自己的技术知识与管理技能相结合,成为企业的关键人物。他们在制定战略和改进生产流程方面发挥了至关重要的作用,这标志着他们在工业环境中的重要性与日俱增。然而,随着商学院毕业生,尤其是高等商学院毕业生的到来,工程师的主导地位开始发生变化。这些新来者带来了不同的视角,通常侧重于金融、市场营销和全球战略。这种转变为公司引入了更多的商业管理,逐渐将权力从工程师手中转移到这些受过财务和商业方面培训的经理人手中。对于习惯于在技术和运营决策中占据核心地位的工程师来说,这种转变有时是一种挑战。引入更注重商业和财务的管理方法造成了紧张关系,反映了公司内部管理重点和方法的变化。这些变化反映了公司内部组织结构和权力动态的不断演变,凸显了不断变化的经济需求和各领域的进步如何影响等级制度和管理实践。

在以社会和经济动荡为标志的二战期间,工程师在改变工作方式方面发挥了至关重要的作用。他们将合理化和机械化的概念引入生产流程,深刻影响了工作的组织和执行方式。在这个时代,工程师们采用理性和结构化的方法来分析生产。他们注重效率和优化,通过将生产流程分解成更小的任务并使其标准化,从而提高生产流程的效率。这样做的目的是减少浪费,提高生产率,最大限度地利用资源。这一转变的一个重要部分是拉近人与机器的距离。工程师们认为,机器在生产率、速度、耐力和精确度方面更胜一筹。因此,他们试图调整人类的工作,使其更加符合机器的原理。这种方法部分受到泰勒主义思想的启发,泰勒主义是弗雷德里克-泰勒提出的一种工作管理理论,主张优化和简化任务以提高效率。这种工程理念对劳动力产生了深远的影响。它带来了更大的专业化和更先进的分工。与此同时,它有时也导致了工作的非人化,员工更多地被视为机器的延伸,而不是具有自身需求和能力的个体。这些发展也对公司内部的工作关系和组织文化产生了影响。随着生产流程的机械化程度越来越高,工程师的作用越来越大,工作关系也随之发生了变化,这往往不利于人际交往和工作满意度的提高。

在二战期间,由工程师发起的劳动分工旨在显著改变工业生产、工作关系以及与客户的互动。这种分工的主要目的之一是精确控制和衡量每个工人的生产率。通过标准化任务和设定绩效标准,管理人员现在可以准确确定每个工人每天应生产多少产品。这与以往生产率衡量不够严格的时期相比,是一次重大变革。此外,这种新的工作组织方式还对客户关系产生了直接影响。由于生产流程更加标准化和合理化,因此可以可靠地计算交货时间。这样,公司就能向客户提供更有力的保证,例如,如果产品不能按时交付,就会对延迟交付进行罚款或退还押金。这种方法增强了客户的信心,为生产引入了商业和合同层面,强调了客户满意度和可靠性作为企业战略关键要素的重要性。因此,这一时期的劳动分工标志着该行业劳动管理和客户关系的转折点,引入了更有条不紊的生产方法,并强调可靠性和信任是商业关系的重要组成部分。

泰勒主义的基础和原则

泰勒制由弗雷德里克-W-泰勒于 20 世纪初提出,是一种彻底改变工业实践的生产管理方法。该体系的重点是通过一系列关键方法提高效率和生产力。泰勒制的第一阶段是将任务分解为基本操作。这种分解的目的是简化每项任务,使其能够更有效、更快速地执行。通过降低任务的复杂性,工人可以专门从事特定的操作,从而提高他们的速度和效率。然后,泰勒主义将这些操作标准化。这意味着要为每项任务制定统一的工作方法和明确的程序。标准化有助于确保生产的一致性和可预测性,减少错误和产品质量差异。泰勒制的另一个关键要素是使用测量工具来评估和提高工人的绩效。这些工具可能包括用于测量完成每项任务所需时间的秒表,使管理人员能够设定时间和生产率标准。然后鼓励或激励工人达到或超过这些标准。泰勒制的采用为企业带来了许多好处。通过提高生产速度和数量,同时保持或降低劳动力成本,企业可以显著提高盈利能力。效率的提高可以实现大规模生产,降低单位成本,并有可能增加公司的市场份额。

泰勒制由美国工程师弗雷德里克-温斯洛-泰勒于 1880 年左右提出,是一种革命性的工业生产管理方法。这种方法产生于一些工程师对知识的研究和积累,泰勒将其严格系统化和正规化。泰勒主义的精髓在于对体力劳动的科学研究。泰勒和他同时代的人试图分解工人的动作和手势,以消除不必要的动作,优化那些能增加价值的动作。这种方法旨在最大限度地提高每个动作的效率,从而减少完成每项任务所需的时间和精力。这种方法的核心部分是科学地组织工作。这涉及对生产方法的细致分析,包括工人的动作、节奏和步伐。其目的是确定最有效的生产方式。泰勒还主张改变薪酬结构,从任务工资改为小时工资,以鼓励提高生产率。为了分析和改进工作技术,泰勒和他的同事们使用了计时和拍摄工人等方法。这些技术使他们能够详细了解工人的行动,并找出提高效率的方法。泰勒制对雇主和工人都有好处。对雇主而言,泰勒制的应用意味着通过提高效率来改善生产。对工人来说,由于消除了不必要的手势和简化了任务,理论上工作变得更轻松,危险性更低。

十九世纪末二十世纪初,泰勒制在美国的传播在很大程度上受到了这一时期大量移民潮的影响,尤其是来自斯拉夫和意大利地区的移民。这些移民通常不识字,也没有正式的资格证书,他们组成了一支数量庞大且易于塑造的劳动力队伍,完全符合泰勒制的要求。由于缺乏资历和技能,移民工人特别适合泰勒主义倡导的标准化和简化的工作方法。因此,公司可以迅速培训这些工人从事特定的工作,提高生产效率,同时保持相对较低的劳动力成本。这给工业企业的雇主带来了相当大的优势,使他们能够最大限度地提高工厂的生产率。从社会和文化的角度来看,这一趋势的后果喜忧参半。对于移民来说,它提供了就业机会和融入美国社会的途径。然而,这也导致工作条件艰苦,任务单调重复,个人技能几乎得不到认可。工作场所往往受到高度控制,强调的是生产而不是工人的福利。泰勒制在美国的采用是由于当时劳动力市场的独特性,即移民众多和劳动力缺乏技能。虽然这种方法提高了工业效率,但也引发了有关工作条件和系统内员工待遇的问题。

在欧洲,接受泰勒制的观念和环境与美国不同。最初,采用泰勒主义原则遇到了一些阻力,主要是因为担心这些原则会对传统手工业和劳动力产生影响。起初,许多欧洲人认为泰勒制是对手工业的威胁,因为手工业重视工人的技能、创造性和自主性。机器会让工人变得 "愚蠢",使他们不再需要思考和决策,这种观点引起了人们的极大关注。这种方法不仅被视为对工作过程的过度简化,而且还可能使工人变得愚笨,使他们的角色沦为重复性、无创造性任务的执行者。然而,随着第一次世界大战的爆发,情况发生了变化。由于许多传统上受雇于工业部门的男性被派往前线,工厂面临着熟练劳动力短缺的问题。为了填补这一缺口,工业部门广泛雇用了妇女和来自殖民地的工人,这些人一般都没有技能。这些新的工人群体更容易接受泰勒主义工作方法,因为这种方法不需要大量的技能或培训。战争期间,快速高效的生产对支持战争至关重要。因此,注重效率和生产率的泰勒制特别适合这种情况。由于劳动力更加温顺,不太习惯传统的工作方法,他们更容易适应标准化和重复性的工作系统。因此,在战时环境的独特需求的推动下,泰勒制开始在欧洲逐渐流行起来。虽然泰勒制最初在欧洲受到抵制,因为人们担心手工艺和工作非人化,但第一次世界大战创造了有利于采用泰勒制的条件。对高效生产的需求和非传统劳动力的可用性促进了这些生产管理方法在欧洲大陆的传播。

泰勒制的经济和运营效益

泰勒制作为一种生产管理制度,具有许多优点,尤其是在工业化背景下为雇主带来了好处。首先,它可以解决劳动力短缺问题。通过简化和标准化任务,泰勒制可以有效地使用技术含量较低的工人。在熟练劳动力有限或昂贵的情况下,这种方法尤为有利。

其次,泰勒制为雇主提供了一种严格控制工人阶级的手段。通过精确定义任务和衡量生产率,管理者可以严格控制工作进度和质量,从而减少绩效差异和非生产性行为。

提高生产率是泰勒制的另一大优势。通过优化每项任务和消除多余的动作,工人可以在更短的时间内完成更多的工作。效率的提高转化为更高的产出,这对企业的发展和竞争力至关重要。

最后,泰勒制有助于降低劳动力成本。工作任务的简化和工作流程的标准化意味着可以雇佣技术含量较低的工人,他们的成本通常也较低。此外,生产率的提高意味着可以用更少的劳动力生产出更多的产品,从而降低单位生产的劳动力成本。

这些优势使泰勒制在工业界大受欢迎,尤其是在其最初发展和实施的时候。然而,该方法也因其对工人福利的潜在影响而受到批评,例如工作单调、自主性降低以及实现高生产率目标的压力增大。

生产优化: 装配线时代

Line work is a production system based on the division of labour and the organisation of workers into different stations or posts. In this system, each worker is responsible for a specific, repetitive task, contributing to one stage in the manufacture of a final product. This method organises workers into production lines, where products move from one station to another, with each worker adding his or her contribution in a predefined order. This system is designed to maximise efficiency and productivity. By standardising tasks and minimising the transition time between different stages of production, assembly line working speeds up the manufacturing process and enables efficient mass production. This leads to a significant increase in the quantity of finished products available and a reduction in production costs. However, despite its advantages in terms of efficiency, assembly line working can have negative effects on workers. The tasks assigned are often monotonous and repetitive, which can lead to a feeling of alienation. Workers can feel disconnected from the final product and their own contributions, due to the fragmented nature of their work. In addition, the fast pace and repetitive nature of the tasks can lead to physical and mental stress, as well as reduced job satisfaction. Although assembly line work has revolutionised industrial production by increasing efficiency and productivity, it also raises important questions about the well-being of workers and the impact of standardisation on the human experience of work.

Henri Ford is famous for having been one of the main instigators of assembly line work in the car industry. In his factories in Detroit, Michigan, from the 1910s onwards, he implemented this system, revolutionising mass production. Ford introduced the concept of breaking down tasks into small, simple operations. Each worker on the assembly line was assigned a specific, repetitive task, which standardised the production process. By standardising these tasks and making them as efficient as possible, Ford was able to significantly reduce the time needed to assemble a vehicle. This methodology has had several major consequences. Firstly, it has led to a spectacular increase in production speed. The Ford Model T, one of the first mass-produced vehicles using this method, could be assembled much more quickly than cars produced using traditional methods. As a result, production quantities also increased dramatically, meeting the growing demand of the automotive market. In addition, Ford's approach helped to reduce labour costs. By simplifying tasks, it was possible to use less skilled labour, which could be trained quickly and efficiently for specific tasks. It also allowed Ford to offer higher wages to its workers, such as the famous five-dollar-a-day wage, while reducing overall production costs. Ford's introduction of the assembly line not only transformed his company and the automotive industry, but also had a significant impact on industrial production practices around the world. This innovation marked a turning point in industrial history, laying the foundations for modern mass production.

Henri Ford not only adopted assembly-line working in his factories, but also introduced technological innovations that greatly improved its efficiency. Among these innovations, moving conveyors played a crucial role. These conveyors transported the products being manufactured from one workstation to another, facilitating the continuity of the production process and reducing the time wasted moving parts around. In addition, Ford implemented the use of specially designed assembly tools for each task on the production line. These tools were adapted to a specific use, minimising errors and interruptions in the assembly process. This standardisation of tools, combined with the continuous movement of parts on conveyors, enabled fast and efficient production. Thanks to these innovations, Ford was able to produce cars at an unprecedented rate. The Ford Model T, in particular, became a symbol of the efficient mass production made possible by these technological and organisational advances. Ford's ability to rapidly produce large quantities of cars at relatively low cost transformed the company into one of the largest car manufacturers in the world. Ford's impact on the concept of the assembly line was a key element of the Industrial Revolution. He demonstrated how the effective application of this system could not only increase productivity, but also improve the profitability of companies. Ford's innovations in mass production had a lasting impact, influencing industrial production methods far beyond the car industry.

Uniformity and Interchangeability: Standardisation of Components

The assembly line, as introduced and popularised by industrialists such as Henry Ford, relies heavily on the standardisation of parts. This standardisation is crucial to the smooth running of the assembly line production system, as it ensures consistent uniformity and compatibility between the parts and components used in the manufacturing process. In an assembly line production system, it is essential that each part fits perfectly into the final product without the need for modifications or adjustments. This is because the production line is designed to be a continuous, fluid process. Stopping the line to make repairs or adjustments to a part would disrupt the entire production process, leading to delays and loss of efficiency. Before the advent of assembly-line production, parts were often manufactured and adjusted manually by craftsmen such as fitters. The role of these professionals was to adapt and perfect each part to fit the object being manufactured, a process that required a high degree of skill and attention to detail. However, this method was much slower and less efficient than assembly-line production. Standardisation and mechanisation changed this approach. By producing perfectly standardised parts, manufacturers were able to speed up the production process and reduce costs. Each mechanically manufactured part had exactly the same dimensions and specifications as the others, ensuring smooth integration into the production process without the need for manual adjustments. This move towards standardisation was a key factor in the rise of mass production and has greatly influenced modern industrial practices. It has made production faster, more efficient and cheaper, although it has also reduced the need for traditional craft skills in industrial production.

Assembly line working, as adopted in the car industry by companies such as Ford, has encouraged uniform production, marked by a repetitive manufacturing process and the production of a limited range of models. This method has had significant implications for the nature of the products manufactured, particularly in terms of design and functionality. In the case of Ford, for example, the mass production of the Model T is a perfect illustration of this concept. The Model T was available in a limited number of variants, which was a direct consequence of the assembly-line production approach. This standardisation enabled Ford to produce vehicles more efficiently and economically, but it also limited the diversity of products available to consumers. The emphasis on uniform production and standardisation led to a focus on product design. In a context where functional differences between products were minimised by their uniform manufacture, design became a key means of differentiating products. For companies like Ford, this meant that design had to be not only aesthetically pleasing, but also functional, eliminating unnecessary parts and optimising the product for sale. This focus on functionality and simplicity led to the elimination of superfluous components, which not only reduced costs but also improved product reliability. By concentrating on the essentials, manufacturers could ensure better quality and greater efficiency, while creating products that were attractive to consumers. Assembly line working led to more uniform production and a reduced product range, with a particular emphasis on functional design. This approach transformed the way products were manufactured and marketed, emphasising efficiency, functionality and aesthetics, while limiting the variety of products available.

Line production, characterised by its uniform nature and reduced product range, led to increased efficiency in the manufacturing process. One of the key advantages of this system is the immediate adjustment of production operations, with no significant delays or waiting times. Each stage of production is carefully synchronised with the others, allowing smooth and continuous manufacturing. In terms of design and function, in-line production has made it possible to incorporate a degree of modularity into the products. This modularity, combined with standardised design, facilitates mass production while offering a degree of flexibility in the final assembly of the product. Design, in this context, is not just limited to the aesthetics of products; it also encompasses aspects such as the performance and durability of parts. An important aspect of design in assembly line production is the consideration of product life. Manufacturers, in some cases, may design products with a limited lifespan, a practice known as programmed obsolescence. This approach aims to encourage regular renewal of consumption by creating products that require replacement after a certain period. While this can stimulate sales and demand for new products, it also raises questions about sustainability and environmental impact. Chain production has transformed not only the way products are made, but also the way they are designed. The emphasis on efficiency, modularity and functional design has enabled rapid and cost-effective mass production, while introducing strategies such as programmed obsolescence to stimulate consumption. These practices have had profound implications for both the economy and society in general.

Functionalism and design in the context of assembly-line production reflect a resolutely industrial approach, in which the main aim is to optimise production to meet commercial objectives. This approach is characterised by a focus on the manufacture of products designed specifically for sale, encouraging mass production and stimulating consumption. From this perspective, design and functionalism are not limited to the simple aesthetics or ergonomics of products. They encompass a broader vision that includes production efficiency, cost reduction, and the creation of products that meet specific market needs. The idea is to design products that are not only attractive and functional, but also easy and economical to produce in large quantities. The emphasis on mass production means designing products that can be manufactured quickly, in series, and at a low unit cost. This enables companies to sell these products at an affordable price to a wide audience, thereby encouraging mass consumption. In the car industry, for example, this principle has made cars accessible to a much wider section of the population. In addition, this industrial approach often includes strategies to encourage regular renewal of products by consumers, such as programmed obsolescence. By limiting the lifespan of products, manufacturers can stimulate continuous demand for new models or versions, fuelling a continuous cycle of production and consumption. This approach has profoundly influenced industrial and economic development, fostering the rise of consumer-based market economies. However, it also raises questions about the sustainability, environmental impact and ethical implications of mass production and consumption.

Fordism: the synthesis of mass production and mass consumption

Henry Ford developed an economic model that also had profound political and social ramifications. This model, often referred to as Fordism, was not just about optimising production, but also about how profits and productivity gains should be used. One of Ford's most significant innovations in this area was the indexing of wages to productivity gains. By introducing the "Five Dollar Day" in 1914, Ford doubled the standard daily wage for his employees, a radical decision for the time. This significant increase in wages had several objectives and effects. Firstly, by increasing the wages of its employees, Ford enabled them to purchase the products they were making, in this case cars. This strategy turned workers into consumers, thereby stimulating demand for Ford's products. It was a practical application of the idea that to sustain a consumer economy, workers had to have sufficient purchasing power to buy the goods they produced. In addition, by paying its employees higher wages, Ford sought to improve worker motivation and loyalty. This also helped to reduce the high staff turnover rate and the costs associated with training new employees, a common problem in factories at the time. The model also had wider social and economic implications. It contributed to the emergence of a larger and more solvent middle class, able to participate in the consumer economy. In addition, Ford's approach to worker pay was influential, prompting other companies to reconsider their own pay structures.

Henry Ford's vision and model of mass production played a key role in shaping the Western economy of the twentieth century. The fundamental idea behind this model was that mass production could be supported by mass consumption, a notion that transformed both markets and societies. In this model, increased production and reduced unit product costs made goods more accessible to a wider range of consumers. At the same time, higher wages, such as Ford's 'Five Dollar Day', gave workers greater purchasing power, enabling them to buy the products they helped to make. This cycle of production and consumption contributed to the rise of the middle class and encouraged the growth of the consumer economy. However, this economic model was not without its critics. Neo-Marxist writers, for example, saw in this system a "gentrification" of the European working class. In their view, the consumer society created by Fordism helped to integrate the working class into a capitalist system, making them dependent on the consumption of mass-produced goods and attenuating their revolutionary potential. They argued that this integration served to stabilise and perpetuate the capitalist system, by distancing the working class from the class struggle and reducing their propensity to question the established order. The economic model promoted by Ford and his contemporaries had strong ideological and political dimensions. It reflected and reinforced certain values such as materialism, continuous economic growth and individualism, which became pillars of many Western societies in the twentieth century.

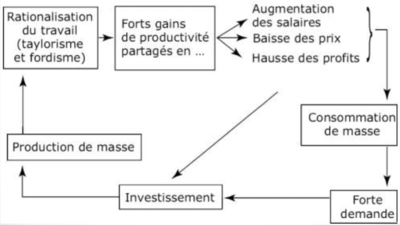

This diagram illustrates the central dynamics of Fordism, an economic model that integrates mass production and mass consumption. At the heart of this model is the rationalisation of work, the principles embodied in Taylorism and Fordism, where efficiency is optimised by standardising tasks and specialising workers. This increased efficiency translates into significant gains in productivity, which are divided between higher wages for employees, lower sales prices for consumers and higher profits for companies. Wage increases, in particular, play a key role in this model. It allows workers to acquire more purchasing power, which turns them into consumers of the products they produce. This increased consumption, supported by lower prices due to economies of scale and the efficiency of mass production, leads to strong demand for products. To meet this demand, companies need to invest more in production, fuelling a virtuous economic cycle of growth and prosperity. In the post-war context, this system supported economic development and the expansion of the middle class in the West. However, critics of Fordism, particularly neo-Marxist thinkers, highlight its ideological and political implications, arguing that the model functioned as an instrument against communism by promoting the gentrification of the working class and integrating them into the capitalist system. The scheme therefore captures the essence of an era when mass production and consumption became the driving forces of the Western economy, a model that was gradually challenged with the rise of the so-called post-Fordist society, characterised by more flexible modes of production and economies.

The idea of high wages combined with the power of trade unions in the post-war context, particularly during the Trente Glorieuses (period of exceptional economic growth after the Second World War until the early 1970s), played a crucial role in structuring Western societies. This period saw the emergence of a system in which workers benefited from higher pay and better working conditions, largely thanks to the influence of trade unions. From the point of view of political logic, this development can be interpreted as a response to communism. At a time when communist ideology was gaining ground, partly because of its promises of fairness and protection for workers, Western countries, anxious to counter the appeal of communism, sought to demonstrate that capitalism could also offer significant benefits to the working classes. From a socio-political point of view, the improvement of wages and working conditions in Western countries served as an instrument in the fight against Communist influence, particularly in Western Europe. By offering workers a greater share of the economic benefits, improving their living conditions and guaranteeing more extensive social rights, governments and companies hoped to dissipate the appeal of communism. This strategy helped to stabilise Western societies during this period, reducing social discontent and increasing loyalty to the capitalist system. Workers, benefiting from a better quality of life and greater protection, were less inclined to support revolutionary movements. Wage improvements and advances in workers' rights during the Trente Glorieuses can be seen as part of a wider strategy to counter the appeal of communism by offering a viable and attractive alternative within the capitalist system. This played an important role in the political and social dynamics of the period.

Fordism, as it emerged and developed in the decades following the Second World War, was a key driver in the transformation of major industrial sectors and significantly shaped the socio-political model of the time. It became synonymous with a certain type of economic and social organisation, characterised by mass production, high wages, product standardisation and high consumption. After the Second World War, Fordism was a fundamental element in understanding the post-war economy and society. It helped to shape a period of economic prosperity and social stability in many Western countries, partly through the promise of continued economic growth and improved living conditions for the working class. However, from the last decades of the twentieth century onwards, the Fordist model began to be challenged and gradually gave way to what is known as the post-Fordist society. This transition marks a shift towards more flexible economies, characterised by more diversified production, greater flexibility in working practices, technological innovation, and a change in labour relations. In post-Fordist societies, the emphasis is on adaptability, product customisation, and the ability to respond quickly to market changes. Information and communication technologies play a key role in this new era, facilitating more agile production and more dynamic management of human resources. In addition, there is a shift towards a service economy and a greater emphasis on knowledge and innovation. The transition from Fordism to Post-Fordism reflects changes in global economic conditions, technological advances and shifts in consumer expectations. Whereas Fordism emphasised efficiency through standardisation, Post-Fordism values flexibility, innovation and the ability to adapt quickly to new market conditions. This development also has profound implications for the structure of work, industrial relations and socio-economic dynamics in the contemporary world.

Conclusion on the Evolution of Production Relationships

At the end of our exploration of the organisation of production relations from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, we find that this period was the scene of profound changes that redefined not only industry, but society as a whole. Taylorism and Fordism, as the catalysts of the industrial age, not only optimised working conditions through a series of scientific methods, but also laid the foundations for a new economic and cultural reality.

The productivity gains resulting from these working methods led to wage increases which, like the famous "Five Dollar Day" at Ford, gave a previously marginalised working class unprecedented purchasing power. This development transformed workers into consumers and gave rise to a new market for consumer goods. Ford's Model T cars, mass-produced and sold at affordable prices, became emblematic of this era and symbolised the democratisation of consumerism. This period also saw the rise of the trade unions, which played a crucial role in negotiating working conditions and wages. Their influence contributed to the establishment of social protections and an implicit social contract promising security and prosperity in exchange for productivity. However, this golden period was not without its critics and contradictions. Neo-Marxist thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse argued that the integration of the working class into the capitalist system, facilitated by mass consumption, represented a subtle form of subjugation, a move away from traditional class struggles. They saw the resulting consumer culture as a strategy for containing the revolutionary potential of the masses.

In the contemporary post-Fordist era, the shift to flexible economies underlines the contrast with Fordist practices. Globalisation, information technology and the transition to a service economy have introduced new paradigms of work and consumption. The Fordist model of stability and uniform consumption has given way to an era of personalisation, rapid change and economic uncertainty. The period from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century was an era of unprecedented progress, shaping our modern understanding of work, production and consumption. The impact of Fordism and Taylorism is still felt today, although the global economy has evolved towards more nuanced and adaptive models. This era remains an essential chapter in understanding the evolution of industrial societies and their transition to the complexity of the current era.