工业革命的社会成本

根据米歇尔-奥利斯(Michel Oris)的课程改编[1][2]

地结构与乡村社会: 前工业化时期欧洲农民分析 ● 旧政体的人口制度:平衡状态 ● 十八世纪社会经济结构的演变: 从旧制度到现代性 ● 英国工业革命的起源和原因] ● 工业革命的结构机制 ● 工业革命在欧洲大陆的传播 ● 欧洲以外的工业革命:美国和日本 ● 工业革命的社会成本 ● 第一次全球化周期阶段的历史分析 ● 各国市场的动态和产品贸易的全球化 ● 全球移民体系的形成 ● 货币市场全球化的动态和影响:英国和法国的核心作用 ● 工业革命时期社会结构和社会关系的变革 ● 第三世界的起源和殖民化的影响 ● 第三世界的失败与障碍 ● 不断变化的工作方法: 十九世纪末至二十世纪中叶不断演变的生产关系 ● 西方经济的黄金时代: 辉煌三十年(1945-1973 年) ● 变化中的世界经济:1973-2007 年 ● 福利国家的挑战 ● 围绕殖民化:对发展的担忧和希望 ● 断裂的时代:国际经济的挑战与机遇 ● 全球化与 "第三世界 "的发展模式

19 世纪,欧洲经历了一场深刻的变革--工业革命,其标志是前所未有的经济增长和现代化进程。然而,这一增长和创新时期也伴随着动荡的社会变革和巨大的人道主义挑战。深入 19 世纪 20 年代的英国城镇,漫步于 19 世纪 40 年代勒克鲁索热气腾腾的车间,或窥探 19 世纪 50 年代比利时东部阴暗的小巷,你会发现一个鲜明的对比:技术进步和繁荣与加剧的不稳定性和混乱的城市化并存。

猖獗的城市化、肮脏的住房、地方病和恶劣的工作条件决定了许多工人的日常生活,工业中心的预期寿命急剧下降至 30 岁。勤劳勇敢的人们离开农村,投入贪婪的工业怀抱,使农村地区的死亡率有了相对改善,但代价是城市的生存环境不堪重负。环境的致命影响甚至比工厂的严酷工作更为有害。

在这个明显不平等的时代,霍乱等流行病凸显了现代社会的缺陷和弱势群体的脆弱性。对这场健康危机的社会和政治反应,从镇压工人运动到资产阶级对暴动的恐惧,揭示了阶级之间日益加剧的鸿沟。这种分化不再由血缘决定,而是由社会地位决定,强化了等级制度,使工人进一步边缘化。

在这一背景下,欧仁-布勒(Eugène Buret)等社会思想家的著作成为工业时代的凄美见证,既表达了对异化的现代性的批判,也表达了对改革的希望,改革将使所有公民融入一个更加公平的政治和社会结构中。这些历史反思为我们提供了一个视角,让我们了解社会变革的复杂性以及公平和人类团结所面临的持久挑战。

新空间

工业盆地和城镇

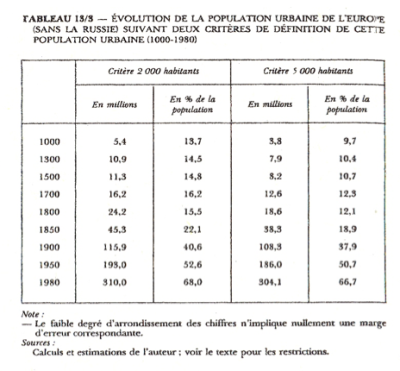

本表从历史角度概述了除俄罗斯以外的欧洲历代城市人口的增长情况,并突出强调了定义城市的两个人口门槛:居民超过 2000 人的城市和居民超过 5000 人的城市。在第二个千年之初,即 1000 年左右,欧洲已经有相当一部分人口居住在城市地区。居民超过 2000 人的城镇有 540 万人,占总人口的 13.7%。如果我们将门槛提高到 5000 人,就会发现有 580 万人,占总人口的 9.7%。随着人口数量向 1500 人迈进,我们发现城市人口的比例略有上升。在居民人数超过 2000 人的城镇,人口增至 1 090 万,占总人口的 14.5%。在居民超过 5000 人的城镇,这一数字上升到 790 万,相当于总人口的 10.4%。1800 年,工业革命的影响开始显现,城市居民人数大幅增加。当时有 2,620 万人居住在人口超过 2,000 人的城镇,占总人口的 16.2%。居民人数超过 5000 人的城镇居民人数增至 1 860 万人,占总人口的 12.5%。十九世纪中期,城市化进程进一步加快,到 1850 年,有 4530 万人居住在居民人数超过 2000 人的城镇,占总人口的 22.1%。居民超过 5000 人的城镇有 3830 万人,占总人口的 18.9%。二十世纪是大规模城市化的转折点。到 1950 年,居民超过 2000 人的城镇人口增至 1.93 亿,占总人口的 53.6%。居民超过 5000 人的城市也不甘示弱,人口达到 1.86 亿,占欧洲总人口的 50.7%。最后,在 1980 年,城市现象达到了新的高度,有 3.10 亿欧洲人居住在人口超过 2000 人的城镇,占总人口的 68.0%。居民超过 5000 人的城镇人口为 3.011 亿,占总人口的 66.7%。因此,该表揭示了欧洲从以农村为主向以城市为主的惊人转变,这一过程随着工业化的发展而加速,并持续了整个 20 世纪。

经济史学家保罗-贝罗赫(Paul Bairoch)认为,旧制度社会的特点是城市人口自然限制在总人口的 15%左右。这一观点源于这样一种观察,即在 1800 年之前,绝大多数人口--70% 至 75%,在农业活动放缓的冬季甚至达到 80%--必须务农才能生产足够的粮食。因此,粮食生产限制了城市人口的规模,因为农业盈余必须养活城市居民,而城市居民往往被视为 "寄生虫",因为他们对农业生产没有直接贡献。非农业人口约占 25-30%,分布在其他活动部门。但并非所有人都是城市居民;有些人在农村地区生活和工作,如教区牧师和其他专业人员。这就意味着,在不对农业生产能力造成过重负担的情况下,能够居住在城市的人口比例最多为 15%。这个数字并不是由于任何正式的法律规定,而是当时的农业和技术发展水平所决定的经济和社会限制。随着工业革命的到来和农业的进步,社会养活更多城市人口的能力不断提高,从而使这一假设的限制被突破,并为城市化的不断发展铺平了道路。

自 19 世纪中期以来,欧洲的人口和社会面貌发生了巨大变化。1850 年前后,工业化的开端开始改变农村和城市人口之间的平衡。农业技术的进步开始减少生产粮食所需的劳动力,城市中不断扩大的工厂开始吸引来自农村的工人。然而,即使发生了这些变化,农民和农村生活在 19 世纪末仍占主导地位。欧洲的大多数人口仍然生活在农业社区,只是到了后来,城镇才逐渐发展起来,社会也变得更加城市化。直到二十世纪中叶,特别是二十世纪五十年代,我们才看到一个重大变化,欧洲的城市化率超过了 50%。这标志着一个转折点,表明历史上第一次有大多数人口居住在城市而不是农村地区。如今,城市化率已超过 70%,城市已成为欧洲最主要的生活环境。拥有曼彻斯特和伯明翰等城市的英格兰是这一变化的起点,紧随其后的是德国鲁尔区和法国北部等其他工业地区,这两个地区都拥有丰富的资源和吸引大量劳动力的工业。这些地区是工业活动的神经中枢,是整个欧洲大陆城市扩张的典范。

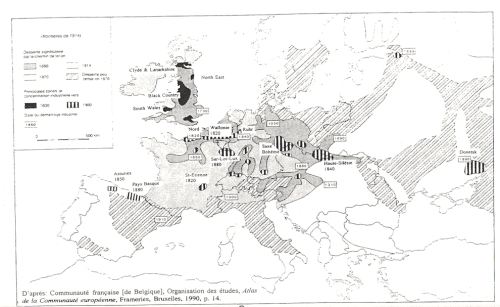

这幅地图以图形的形式展示了前工业时代的欧洲,突出了第一次世界大战前的主要工业中心地区。它通过不同的符号和图案来识别每个地区的主要工业类型,从而突出了工业活动的强度和专业化程度。用高炉和煤矿符号标出的深色区域表示以冶金和采矿为主的工业盆地。鲁尔、法国北部、西里西亚、比利时黑土地区和南威尔士等地都是重要的工业中心,显示了煤炭和钢铁在当时欧洲经济中的重要性。带条纹的区域则表示纺织业和机械工程发达的地区。这种地理分布表明,工业化并不是千篇一律的,而是集中在某些地方,这取决于可用资源和资本投资。有明显特征的区域表示专门从事钢铁工业的地区,特别是洛林以及意大利和西班牙的部分地区,这表明钢铁工业也很普遍,尽管不如煤炭工业占主导地位。船只等海事标志位于英格兰东北部等地区,表明造船业的重要性,这与欧洲殖民帝国的扩张和国际贸易是一致的。这幅地图形象地说明了工业革命如何改变了欧洲的经济和社会面貌。所确定的工业地区可能是国内移民的热点地区,吸引了来自农村的工人前往不断发展的城市。这对人口结构产生了深远的影响,导致了快速的城市化、工人阶级的发展以及新的社会挑战(如污染和不合标准的住房)的出现。该地图凸显了整个非洲大陆工业发展的不平衡性,反映了在经济机会、生活条件和人口增长方面出现的地区差异。这些工业地区对各自国家的经济和社会发展轨迹产生了决定性的影响,这种影响远远超过了古典工业时代。

前工业化欧洲的历史地图描绘了对欧洲大陆经济和社会转型至关重要的两大类工业地区:"黑人国家 "和纺织城。黑色国家 "以高炉和矿山图标的深色区域为代表。这些地区是重工业的中心,主要以煤矿和钢铁生产为中心。煤炭是工业经济的基础,为支撑工业革命的机器和工厂提供动力。德国鲁尔区、法国北部、西里西亚和比利时黑土区等地区都是著名的工业中心,其特点是煤炭和钢铁相关活动密集。相比之下,以条纹区域为标志的纺织城则专门从事纺织品生产,这一行业在工业革命期间也至关重要。这些城镇利用机械化优势大规模生产纺织品,从而提升了它们作为主要工业中心的地位。纺织革命始于英国,并迅速蔓延到欧洲其他地区,催生了众多以纺纱和织布为中心的工业城镇。这两类工业地区之间的区别至关重要。黑人国家通常以污染、艰苦的工作条件和对环境的严重影响为特征,而纺织城镇虽然也有其自身的社会和健康挑战,但通常污染较少,而且由于纺织厂与高炉和矿山相比对重型资源的集中度要求较低,因此可以更加分散。因此,这幅地图不仅突出了工业化的地理分布,也突出了构成当时欧洲经济结构的工业的多样性。在工业革命的背景下,每个地区都产生了独特的社会效应,影响了工人的生活、社会阶层的结构、城市化以及城乡社会的演变。

黑土地 "是一个令人回味的术语,用来描述工业革命期间煤炭开采和金属生产的地区。这个词指的是这些地区无处不在的浓烟和煤灰,这是高炉和铸造厂剧烈活动的结果,它们在很短的时间内将宁静的村庄变成了工业城镇。大气污染严重,天空和建筑物都被熏黑,因此被称为 "黑色国家"。这种快速工业化的现象颠覆了当时的静态世界,标志着一个经济增长成为常态、停滞成为危机代名词的时代的开始。煤矿开采业需要大量劳动力,从而推动了这一转变。煤矿和钢铁工业成为令人眼花缭乱的人口扩张背后的驱动力,例如在塞拉英,工业家科克里尔的到来使人口在一个世纪内从 2000 人增加到 44000 人。煤矿需要大量体力,尤其是在 20 世纪 20 年代自动化之前的镐头工作。对劳动力的这种需求导致农村人口大量涌向这些工业活动中心。由于所处理的材料重量大、体积大,炼铁厂需要很大的空地,因此无法建在已经很密集的城镇中。因此,工业化转移到了农村,因为那里有可用的空间,煤炭也近在咫尺。这就形成了巨大的工业盆地,从根本上改变了相关地区的景观以及社会和经济结构。这些工业变革也给社会带来了深刻变化。随着工人阶级的诞生以及污染和快速城市化导致的生活条件恶化,日常生活发生了翻天覆地的变化。黑色国家 "成为进步的象征,同时也见证了工业革命的社会和环境代价。

维克多-雨果曾这样描述这些风景:"当你经过一个叫小弗莱马勒的地方时,眼前的景象变得难以言喻,真正壮丽无比。整个山谷仿佛都是喷发的火山口。有的火山口喷出猩红色的蒸汽漩涡,在灌木丛后闪烁着火花;有的火山口在红色的背景下阴沉地勾勒出村庄的黑色轮廓;还有的火山口从建筑群的缝隙中喷出火焰。你会以为一支敌军刚刚越过这个国家,二十个村庄被洗劫一空,在这个漆黑的夜晚,你可以同时看到大火的各个方面和各个阶段,有的被火焰吞没,有的在冒烟,有的在燃烧。这战争的景象是和平造成的;这骇人听闻的破坏是工业造成的。你们现在看到的只是科克里尔先生的高炉。

这段引文出自维克多-雨果 1834 年创作的《莱茵河畔的旅行》,有力地证明了欧洲工业化所带来的视觉和情感冲击。雨果以文学创作著称,同时也关注当时的社会问题,他在这里以黑暗而有力的抒情笔触描绘了比利时的默兹河谷,在小弗莱马勒附近,约翰-考克里尔的工业设施是这里的标志。雨果用破坏和战争的形象来描述他眼前的工业场景。高炉照亮了黑夜,就像喷发的火山口、燃烧的村庄,甚至是被敌军蹂躏的土地。和平与战争形成了鲜明的对比;他所描述的场景不是武装冲突的结果,而是和平或至少是非军事工业化的结果。喷发的弹坑 "让人联想到工业活动的强度和暴力,而工业活动就像战争本身一样在这片土地上留下了不可磨灭的印记。这种戏剧性的描述强调了工业化既能引起人们的兴趣,也能引起人们的反感。一方面是人类变革的伟大和力量,另一方面是对生活方式和环境的破坏。作品中提到的大火和村庄的黑色轮廓,投射出这片土地被近乎世界末日的力量所控制的形象,反映出工业进步的矛盾性。要理解这段引文的背景,我们需要记住,19 世纪 30 年代的欧洲正处于工业革命之中。技术革新、煤炭的大量使用以及冶金业的发展从根本上改变了经济、社会和环境。科克里尔是这一时代领先的工业企业家,他在比利时塞拉英开发了欧洲最大的工业综合体之一。这一工业的兴起是经济繁荣的代名词,但同时也带来了社会动荡和相当大的环境影响,包括污染和景观退化。维克多-雨果通过这句话让我们反思工业化的两面性,它既是进步的源泉,也是破坏的根源。他通过这句话揭示了一个时代的模糊性,即人类的天才能够改变世界,但也必须面对这些改变有时带来的黑暗后果。

工业革命时期的纺织城代表了始于 18 世纪的经济和社会变革的一个重要方面。在这些城市中心,纺织业发挥了推动作用,而纺织、纺纱和印染等不同工序的极端分工则促进了纺织业的发展。与重型煤炭和钢铁工业不同的是,由于物流和空间的原因,它们通常位于农村或城市周边地区,而纺织厂则能够利用现有或专门建造的城市建筑的垂直性,最大限度地利用有限的建筑面积。这些工厂成为城市景观的自然组成部分,帮助重新定义了法国北部、比利时和其他地区的城镇,这些地区的人口密度急剧增加。从手工业和原始工业向大规模工业生产的过渡导致许多手工业者破产,转而在工厂工作。纺织品工业化将城镇变成了名副其实的工业大都市,导致了快速且往往是无序的城市化,其特点是在每一个可用的空间都进行无节制的建设。由于工业化提高了生产率,纺织品产量的大幅增长并没有带来工人数量的相应增加。因此,当时纺织城的特点是劳动力极度集中在工厂,工厂成为社会和经济生活的中心,使市政厅或公共广场等传统机构黯然失色。工厂主导了公共空间,不仅决定了城市景观,也决定了社区生活的节奏和结构。这种转变也影响了城镇的社会构成,吸引了从 19 世纪经济增长中获益的商人和企业家。这些新的精英往往支持并投资于工业和住宅基础设施的发展,从而推动了城市的扩张。总之,纺织城体现了工业史的基本篇章,说明了技术进步、社会变革和城市环境重构之间的密切联系。

两种人口发展类型

工业革命导致大量人口从农村迁往城市,不可逆转地改变了欧洲社会。就纺织城而言,农村人口的外流尤为明显。传统上分散在农村家庭或小作坊工作的手工业者和原产业工人被迫聚集到工业城市。这是由于需要靠近工厂,因为工厂的工作结构越来越规范,从家到工作地点之间的长途跋涉变得不切实际。工人集中在城市产生了几种后果。一方面,由于工人靠近生产基地,因此可以更有效地管理和合理安排工作流程,从而在不增加工人数量的情况下实现生产率的激增。事实上,生产技术的创新,如蒸汽机的使用以及纺织和纺纱工序的自动化,在保持或减少所需劳动力的同时,大大提高了产量。在城市,人口的集中也导致了快速的人口密集化和城市化,韦尔维耶(Verviers)就是一个例子。这座比利时纺织城的人口在十九世纪几乎增加了两倍,从最初的 35,000 人增加到世纪末的 100,000 人。城市人口的快速扩张往往导致城市化进程仓促,生活条件艰苦,因为现有的基础设施很少足以应对如此大量的人口涌入。劳动力的集中也改变了城市的社会结构,产生了新的产业工人阶层,并改变了现有的社会经济动态。它还对城市结构产生了影响,为工人建造了住房,扩大了城市服务和设施,发展了以工厂而非传统城市结构为中心的新型社区生活。最终,工业革命时期的纺织城现象说明了工业化对居住模式、经济和整个社会的变革力量。

由于工厂和矿山产生的烟尘和污染而经常被称为 "黑色国家 "的钢铁地区,从另一个侧面说明了工业化对人口和城市发展的影响。黑色国家以煤炭和钢铁工业为中心,而煤炭和钢铁工业是工业革命的重要催化剂。这些地区人口爆炸的原因与其说是每个矿山或工厂工人数量的增加,不如说是新的劳动密集型产业的出现。虽然机械化在不断进步,但尚未取代煤矿和炼铁厂对工人的需求。例如,虽然蒸汽机使矿井通风成为可能,提高了矿井的生产率,但采煤仍然是一项非常费力的工作,需要大量工人。列日等城镇的人口从 5 万增加到 40 万,见证了这种工业扩张。煤田和钢铁厂成为吸引工人寻找工作的中心,导致周边城镇迅速发展。这些工人通常是来自农村或其他工业化程度较低地区的移民,被这些新兴工业创造的就业机会所吸引。这些工业城镇以惊人的速度发展,但往往缺乏必要的规划或基础设施来充分容纳新增人口。结果是生活条件岌岌可危,住房拥挤、不卫生、公共卫生问题和社会矛盾日益加剧。这些挑战最终导致了随后几个世纪的城市和社会改革,但在工业革命期间,这些地区却经历了快速且往往是混乱的转型。

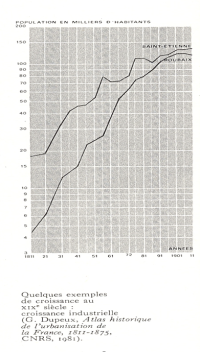

该图显示了圣埃蒂安和鲁贝这两个法国工业史诗中的标志性城市在 1811 年至 1911 年期间的人口增长情况。在这一世纪中,由于工业化的蓬勃发展,这两个城市的人口大幅增长。鲁贝的人口增长尤为显著。该镇以蓬勃发展的纺织业而闻名,居民人数从世纪初的不到 10,000 人增长到世纪末的约 150,000 人。劳动密集型纺织业导致大量农村人口向鲁贝迁移,从根本上改变了鲁贝的社会和城市面貌。圣埃蒂安的人口数量虽然低于鲁贝,但也呈现出类似的上升趋势。作为冶金和武器制造的战略中心,圣艾蒂安对技术工人和非技术工人的需求巨大,从而推动了人口的增长。工业化推动了重大的社会变革,这些小社区蜕变为密集的城市中心就反映了这一点。这种转变并非没有困难:快速城市化导致过度拥挤、住房条件差和健康问题。显然,需要发展适当的基础设施来满足人口日益增长的需求。虽然这些人口的增长刺激了当地经济的发展,但也引发了生活质量和社会差距的问题。圣埃蒂安和鲁贝的演变代表了工业化对小型农村社区转变为大型现代化城市中心的影响,其中既有好处,也有挑战。

工业化导致工业城镇和城市迅速而无序地发展,与同时现代化的大城市形成了明显的对比。比利时的塞拉因(Seraing)等城镇因其钢铁厂和矿山而迅速实现工业化,人口大幅增加,但却没有伴随这种扩张而进行必要的城市规划。这些工业城镇的人口密度与大城市相当,但往往缺乏相应的基础设施和服务。相反,它们的快速发展具有无序扩张的村庄的特征,组织机构简陋,公共服务不足,尤其是在公共卫生和教育方面。由于人口的快速增长,基础设施和公共服务的匮乏就更成问题了。在这些城镇中,对小学、医疗服务和基本基础设施的需求远远超出了当地政府的能力。工业城镇的财政状况往往岌岌可危:它们为建造学校和其他必要的基础设施背负了巨额债务,塞拉因就是一个例子,它直到 1961 年才偿还了最后一笔建校贷款。由于工人工资低,这些城镇的税基也很低,这限制了它们投资进行必要改善的能力。因此,当大城市开始享受现代化的特质--自来水、电力、大学和高效的行政管理时,工业城镇却在努力为居民提供基本服务。这种情况反映了工业时代固有的社会和经济不平等,在工业时代,繁荣和技术进步与大部分劳动人口不稳定和不充分的生活条件并存。

住房条件和卫生

工业革命彻底改变了城市面貌,纺织城就是一个鲜明的例子。这些地区在工业化之前就已经人口稠密,必须迅速适应新一轮的人口流入。这主要是由于纺织工业集中在特定的城市地区,吸引了来自各地的工人。为了解决由此造成的住房短缺问题,城镇不得不对现有住房进行密集化改造。人们往往在建筑物上加盖楼层,利用一切可用的平方米,甚至是狭窄的小巷。这种对城市基础设施的临时改造造成了不稳定的居住条件,因为这些加盖的建筑并不总是考虑到必要的安全性和舒适性。这些城市的基础设施,如卫生、供水和废物管理系统,往往不足以应对人口的快速增长。卫生和教育服务也难以满足日益增长的需求。这种快速的、有时是无政府状态的城市化导致了艰难的生活条件,对居民的健康和福祉造成了长期影响。这些挑战反映了工业革命时期快速变化的城市中经济发展与社会需求之间的矛盾。当时的政府当局往往被规模巨大的变化压得喘不过气来,并竭力资助和实施所需的公共服务,以跟上人口爆炸式增长的步伐。

库伯恩博士是 20 世纪初在比利时塞拉英工作的一名医生。他亲眼目睹了快速工业化对工人及其家庭生活条件造成的影响。库伯恩医生对公共卫生问题和城市卫生有着专业的兴趣,或许也是个人兴趣。当时的医生开始将健康与环境联系起来,特别是不达标的住房会导致疾病的传播。他们往往通过倡导改善城市规划、卫生和住房标准,在改革生活条件方面发挥关键作用。库伯恩博士表明,他关注这些问题,并利用自己的平台提请人们注意工人们被迫生活在不卫生的环境中。

库博恩博士描述了当时工人住房的糟糕状况。在谈到塞拉英时,他写道 他说:"住宅都是按原样建造的,大多数都不卫生,没有总体规划。低矮的下沉式房屋,不通风也不采光;底层只有一个房间,没有人行道,没有地窖;阁楼作为上层;通过一个洞通风,屋顶上安装了一块玻璃;生活用水停滞;没有厕所或厕所不足;过度拥挤和杂乱无章"。他提到房屋建筑简陋,缺乏新鲜空气、自然光和基本的卫生条件,如足够的厕所。这幅图显示了城市规划的缺失和对工人福利的漠视,由于需要在工厂附近安置日益增多的工人阶级,工人们被迫在恶劣的条件下生活。

正如库伯恩博士所描述的那样: "正是在这些不卫生的地方,在这些肮脏的地方,流行病就像猛禽一样扑向它的受害者。霍乱让我们看到了这一点,流感让我们想起了这一点,也许斑疹伤寒会在某一天给我们提供第三个例子",他指出了这些恶劣的生活条件对居民健康造成的灾难性后果。库伯恩博士将不卫生的住房与霍乱、流感和潜在的斑疹伤寒等流行病的传播联系起来。鸷鸟扑向受害者的比喻非常有力,让人联想到工人的脆弱性,他们在不卫生的环境中面对疾病泛滥就像无助的猎物。

这些证词代表了 19 世纪末 20 世纪初欧洲工业城镇的生活状况。它们反映了工业革命的严峻现实,尽管工业革命取得了技术和经济上的进步,但往往忽视了人和社会方面的问题,导致公共卫生问题和明显的社会不平等。这些引文呼吁人们反思城市规划、体面住房和人人享有适当医疗服务的重要性,这些问题在世界许多地方仍然是热门话题。

所谓的 "黑土地 "地区通常与以煤矿开采和炼钢为主的工业区有关,其发展往往迅速而无序。这种无序的发展是城市化加速的结果,在城市化进程中,容纳大量不断增长的劳动力的需求优先于城市规划和基础设施。在许多情况下,这些地区的生活条件极不稳定。工人及其家人往往住在棚户区或匆忙建造的住宅中,很少考虑到耐用性、卫生或舒适度。这些住房往往没有坚实的地基,不仅不卫生,而且很危险,容易倒塌或成为疾病的滋生地。建筑密度大、缺乏通风和采光,以及缺乏自来水和卫生系统等基本基础设施,都加剧了公共卫生问题。改善这些地区的成本过高,特别是考虑到这些地区的面积和现有建筑的质量较差。正如 Kuborn 博士在关于塞拉英的评论中所指出的,建立供水和排污系统需要大量投资,而地方当局往往无力承担。事实上,由于工人工资低,税基小,这些社区用于基础设施投资的资源很少。结果,这些社区发现自己陷入了恶性循环:基础设施不足导致公共卫生和生活质量下降,这反过来又阻碍了改善现状所需的投资和城市规划。最后,唯一可行的解决办法似乎往往是拆除现有建筑并进行重建,但这一过程成本高昂且具有破坏性,而且并非总能实现。

路易-巴斯德在十九世纪中叶发现了微生物并认识到卫生的重要性,这对公共卫生至关重要。然而,这些卫生原则在工业化城市地区的应用因多种因素而变得复杂。首先,无政府主义的城市化,在没有适当规划的情况下进行的开发,导致了不卫生的住房和基本基础设施的缺乏。在已建成的密集城镇中安装供水和排污系统极其困难,而且成本高昂。与规划好的居民区不同,高效的管道网络可以为小范围内的众多居民提供服务,而无序扩张的棚户区则需要铺设数公里长的管道才能连接每一个分散的住宅。其次,废弃的地下采矿造成的地面沉降对新基础设施的完整性构成了巨大风险。这些地面运动很容易损坏或毁坏管道,使为改善卫生状况所做的努力和投资化为乌有。第三,空气污染进一步加剧了健康问题。工厂和熔炉冒出的浓烟使城镇笼罩在一层烟尘和污染物中,这不仅使空气呼吸不健康,而且还导致建筑物和基础设施老化。所有这些因素都证明,在已经建成的工业化城市环境中建立卫生和公共健康标准非常困难,尤其是在仓促开发和缺乏长远规划的情况下。这凸显了城市规划和预测在城市管理中的重要性,尤其是在工业快速发展的背景下。

作为工业革命的后来者,德国的优势在于可以观察和学习比利时和法国等邻国所犯的错误和面临的挑战。这使德国在工业化过程中,特别是在工人住房和城市规划方面,采取了更有条理、更有计划的方法。德国当局实施的政策鼓励为工人建造质量更好的住房,以及更宽阔、更有组织的街道。这与其他地方的工业城市往往混乱和不健康的状况形成了鲜明对比,在其他地方,快速和无序的发展导致居民区过度拥挤和设施简陋。德国做法的一个重要方面是致力于推行更进步的社会政策,承认工人福利对整体经济生产力的重要性。德国的工业企业通常会主动为员工建造住房,并配备花园、浴室和洗衣房等设施,这有助于工人的健康和舒适。此外,德国的社会立法,如奥托-冯-俾斯麦总理在 19 世纪 80 年代推出的医疗保险、意外保险和养老保险法,也有助于为工人及其家庭建立一个安全网。这些改善工人住房和生活条件的努力与预防性社会立法相结合,帮助德国避免了快速工业化带来的一些最坏影响。这也为德国日后成为一个更加稳定的社会和工业大国奠定了基础。

营养不良和工资低

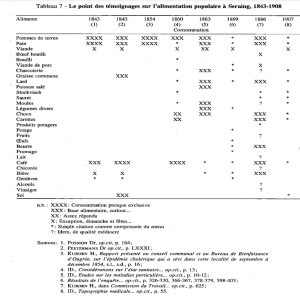

This table provides a historical window on eating habits in Seraing, Belgium, from 1843 to 1908. Each column corresponds to a specific year or period, and the consumption of different foods is coded to indicate their prevalence in the local diet. The codes range from "XXXX" for almost exclusive consumption, to "X" for lesser consumption. An asterisk "*" indicates a simple mention of the food, while annotations such as "Accessory" or "Exception, party..." suggest occasional consumption or consumption linked to particular events. Question marks "?" are used when consumption is uncertain or undocumented, and the words "of mediocre quality" suggest lower quality products at certain times. An analysis of this table reveals several notable aspects of the diet of the period. Potatoes and bread emerge as fundamental elements, reflecting their central role in the diet of the working classes in Europe during this period. Meat, with a notable presence of boiled beef and charcuterie, was consumed less regularly, which may indicate variations in income or seasonal food preferences. Coffee and chicory seem to be gaining in popularity, which could correspond to an increase in the consumption of stimulants to cope with long working hours. The mention of fats such as lard and common fat indicates a calorie-rich diet, essential to support the demanding physical work of the time. Alcohol consumption is uncertain towards the end of the period studied, suggesting changes in drinking habits or perhaps in the availability of alcoholic beverages. Fruit, butter and milk show variability that could reflect fluctuations in food supply or preferences over time. The changes in eating habits indicated by this table may be linked to the major socio-economic transformations of the period, such as industrialisation and improvements in transport and distribution infrastructures. It also suggests a possible improvement in living standards and social conditions within the Seraing community, although this would require further analysis to confirm. Overall, this table is a valuable document for understanding food culture in an industrial town, and may give some indication of the state of health and quality of life of its residents at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

The emergence of markets in industrial towns in the 19th century was a slow and often chaotic process. In these newly-formed towns, or those expanding rapidly as a result of industrialisation, the commercial structure struggled to keep pace with population growth and the influx of workers. Grocers and shopkeepers were rare and, because of their scarcity and lack of competition, they could afford to set high prices for foodstuffs and everyday consumer goods. This situation had a direct impact on the workers, the majority of whom were already living in precarious conditions, with wages often insufficient to cover their basic needs. Shopkeepers exploited workers through price gouging, driving workers into debt. This economic insecurity was exacerbated by low wages and vulnerability to economic and health hazards. Against this backdrop, companies were looking for solutions to compensate for the lack of services and shops, and to ensure a degree of control over their workforce. One such solution was the truck-system, a system of payment in kind whereby part of the workers' wages was paid in the form of foodstuffs or household goods. The company bought these products in bulk and redistributed them to its employees, often at prices determined by the company itself. The advantage of this system was that the company could retain and control its workforce, while guaranteeing an outlet for certain products. However, the truck-system had major disadvantages for the workers. It limited their freedom of choice in terms of consumption and made them dependent on the company for their basic needs. What's more, the quality of the goods supplied could be mediocre, and the prices set by the company were often high, further increasing the workers' indebtedness. The introduction of this system highlights the importance of the company in the daily lives of workers at the time, and illustrates the difficulties they faced in accessing consumer goods independently. It also reflects the social and economic dimension of industrial work, where the company is not just a place of production but also a central player in the lives of workers, influencing their food, housing and health.

The perception of the worker as immature in the nineteenth century is a facet of the paternalistic mentality of the time, when factory owners and social elites often believed that workers lacked the discipline and wisdom to manage their own welfare, particularly where finances were concerned. This view was reinforced by class prejudice and by observing the difficulties workers had in rising above the conditions of poverty and the often miserable environment in which they lived. In response to this perception, as well as to the abject living conditions of the workers, a debate began about the need for a minimum wage that would allow workers to support themselves without falling into what the elites considered depraved behaviour ('debauchery'). Debauchery, in this context, could include alcoholism, gambling, or other activities deemed unproductive or harmful to social order and morality. The idea behind the minimum wage was to provide basic financial security that could, in theory, encourage workers to lead more stable and 'moral' lives. It was assumed that if workers had enough money to live on, they would be less inclined to spend their money irresponsibly. However, this approach did not always take into account the complex realities of working-class life. Low wages, long hours and difficult living conditions could lead to behaviour that elites considered debauchery, but which could be ways for workers to cope with the harshness of their existence. The minimum wage movement can be seen as an early recognition of workers' rights and a step towards the regulation of work, although it was also tinged with condescension and social control. This debate laid the foundations for later discussions on workers' rights, labour legislation and corporate social responsibility, which continued to evolve well into the nineteenth century.

Engel's Law, named after the German economist Ernst Engel, is an empirical observation that points to an inverse relationship between household income and the proportion of it spent on food. According to this law, the poorer a household is, the greater the proportion of its limited resources it has to devote to essential needs such as food, because these expenses are incompressible and cannot be reduced beyond a certain point without affecting survival. This law has become an important indicator for measuring poverty and living standards. If a household spends a large part of its budget on food, this often indicates a low standard of living, as there is little left over for other aspects of life such as housing, health, education and leisure. In the 19th century, in the context of the industrial revolution, many workers lived in conditions of poverty and their wages were so low that they could not pay tax. This reflected not only the extent of poverty, but also the lack of financial resources available to governments to improve infrastructure and public services, as a broader tax base is often required to fund such developments. Over time, as the industrial revolution progressed and economies developed, real wages slowly began to rise. This was partly due to the increase in productivity brought about by new technologies and mechanisation, but also because of workers' struggles and demands for better working conditions and higher wages. These changes have contributed to a better distribution of wealth and a reduction in the proportion of expenditure devoted to food, reflecting an improvement in the general standard of living.

The law does not stipulate that food expenditure decreases in absolute terms as income rises, but rather that its relative share of the total budget decreases. So a better-off person or household can absolutely spend more in absolute terms on food than someone less well-off, while devoting a smaller proportion of their total budget to this category of expenditure. For example, a low-income family might spend 50% of its total income on food, while a well-off family might spend only 15%. However, in terms of the actual amount, the well-off family may spend more on food than the low-income family simply because their total income is higher. This observation is important because it makes it possible to analyse and understand consumption patterns according to income, which can be crucial for the formulation of economic and social policies, particularly those relating to taxation, food subsidies and social assistance programmes. It also provides valuable information about the socio-economic structure of the population and changes in lifestyles as living standards improve.

The ultimate judgement: the mortality of industrial populations

The growth paradox

The 19th century era of industrial revolution and economic expansion was a period of profound and contrasting transformations. On the one hand, there was significant economic growth and unprecedented technical progress. On the other hand, this often translated into extremely difficult living conditions for workers in rapidly expanding urban centres. One dark reality of this period needs to be highlighted: rapid, unregulated urbanisation (what some call "uncontrolled urbanisation") led to unhealthy living conditions. Industrial towns, which grew at a frenetic pace to house an ever-increasing workforce, often lacked adequate infrastructure for sanitation and access to drinking water, leading to the spread of disease and a decline in life expectancy. In cities such as the English towns of the early 19th century, Le Creusot in France in the 1840s, the region of eastern Belgium around 1850-1860, or Bilbao in Spain at the turn of the 20th century - industrialisation was accompanied by devastating human consequences. Workers and their families, often crammed into overcrowded and precarious housing, were exposed to a toxic environment, both at work and at home, with life expectancy falling to levels as low as 30 years, reflecting the harsh working and living conditions. The contrast between urban and rural areas was also marked. While the industrial cities suffered, the countryside was able to enjoy improvements in quality of life thanks to a better distribution of the resources generated by economic growth and a less concentrated, less polluted environment. This period of history poignantly illustrates the human costs associated with rapid, unregulated economic development. It underlines the importance of balanced policies that promote growth while protecting the health and well-being of citizens.

The origins of trade unionism date back to the Industrial Revolution, a period marked by a radical transformation in working conditions. Faced with long, arduous working days, often in dangerous or unhealthy environments, workers began to unite to defend their common interests. These first trade unions, often forced to operate underground because of restrictive legislation and strong employer opposition, set themselves up as champions of the workers' cause, with the aim of achieving concrete improvements in their members' living and working conditions. The trade union struggle focused on several key areas. Firstly, reducing excessive working hours and improving hygiene conditions in industrial environments were central demands. Secondly, the unions fought to obtain wages that would not only enable workers to survive, but also to live with a minimum of comfort. They also worked to ensure a degree of job stability, protecting workers from arbitrary dismissal and avoidable occupational hazards. Finally, trade unions have fought for the recognition of fundamental rights such as freedom of association and the right to strike. Despite adversity and resistance, these movements gradually won legislative advances that began to regulate the world of work, paving the way for a gradual improvement in working conditions at the time. In this way, the first trade unions not only shaped the social and economic landscape of their time, but also paved the way for the development of contemporary trade union organisations, which are still influential players in the defence of workers' rights around the world.

The low adult mortality rate in industrial towns, despite precarious living conditions, can be explained by a phenomenon of natural and social selection. The migrant workers who came from the countryside to work in the factories were often those with the best health and the greatest resilience, qualities necessary to undertake such a change of life and endure the rigours of industrial work. These adults, then, represented a subset of the rural population characterised by greater physical strength and above-average boldness. These traits were advantageous for survival in an urban environment where working conditions were harsh and health risks high. On the other hand, children and young people, who were more vulnerable because of their incomplete development and lack of immunity to urban diseases, suffered more and were therefore more likely to die prematurely. On the other hand, adults who survived the first few years of working in the city were able to develop a certain resistance to urban living conditions. This is not to say that they did not suffer from the harmful effects of the unhealthy environment and the exhausting demands of factory work; but their ability to persevere despite these challenges was reflected in a relatively low mortality rate compared with younger, more fragile populations. This dynamic is an example of how social and environmental factors can influence mortality patterns within a population. It also highlights the need for social reform and improved working conditions, particularly to protect the most vulnerable segments of society, especially children.

The environment more than work

The observation that the environment had a greater lethal impact than work itself during the Industrial Revolution highlights the extreme conditions in which workers lived at the time. Although factory work was extremely difficult, with long hours, repetitive and dangerous work, and few safety measures, it was often the domestic and urban environment that was the most lethal. Unsanitary housing conditions, characterised by overcrowding, lack of ventilation, little or no waste disposal infrastructure and poor sewage systems, led to high rates of contagious diseases. Diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis and typhoid spread rapidly in these conditions. In addition, air pollution from burning coal in factories and homes contributed to respiratory and other health problems. Narrow, overcrowded streets, a lack of green areas and clean public spaces, and limited access to clean drinking water exacerbate public health problems. The impact of these deleterious environmental conditions was often immediate and visible, leading to epidemics and high mortality rates, particularly among children and the elderly, who were less able to resist disease. This highlighted the critical need for health and environmental reforms, such as the improvement of housing, the introduction of public health laws, and the creation of sanitation infrastructures, to improve the quality of life and health of urban populations.

The Le Chapelier law, named after the French lawyer and politician Isaac Le Chapelier who proposed it, is an emblematic law of the post-revolutionary era in France. Enacted in 1791, the law aimed to abolish the guilds of the Ancien Régime, as well as any form of professional association or grouping of workers and craftsmen. The historical context is important for understanding the reasons for this law. One of the aims of the French Revolution was to destroy feudal structures and privileges, including those associated with guilds and corporations, which controlled access to trades and could set prices and production standards. In this spirit of abolishing privileges, Le Chapelier's law aimed to liberalise labour and promote a form of equality before the market. The law also prohibited coalitions, i.e. agreements between workers or employers to set wages or prices. In this sense, it opposed the first movements of workers' solidarity, which could threaten the freedom of trade and industry advocated by the revolutionaries. However, by prohibiting any form of association between workers, the law also had the effect of severely limiting the ability of workers to defend their interests and improve their working conditions. Trade unions did not develop legally in France until the Waldeck-Rousseau law of 1884, which reversed the ban on workers' coalitions and authorised the creation of trade unions.

Immigration to industrial areas in the 19th century was often a phenomenon of natural selection, with the hardiest and most adventurous leaving their native countryside in search of better economic opportunities. These individuals, because of their stronger constitution, had a slightly higher life expectancy than the average, despite the extreme working conditions and premature physical wear and tear they suffered in the factories and mines. Early old age was a direct consequence of the arduous nature of industrial work. Chronic fatigue, occupational illnesses and exposure to dangerous conditions meant that workers 'aged' faster physically and suffered health problems normally associated with older people. For the children of working-class families, the situation was even more tragic. Their vulnerability to disease, compounded by deplorable sanitary conditions, dramatically increased the risk of infant mortality. Contaminated drinking water was a major cause of diseases such as dysentery and cholera, which led to dehydration and fatal diarrhoea, particularly in young children. Food preservation was also a major problem. Fresh produce such as milk, which had to be transported from the countryside to the towns, deteriorated rapidly without modern refrigeration techniques, exposing consumers to the risk of food poisoning. This was particularly dangerous for children, whose developing immune systems made them less resistant to food-borne infections. So, despite the robustness of adult migrants, environmental and occupational conditions in industrial areas contributed to a high mortality rate, particularly among the most vulnerable populations such as children.

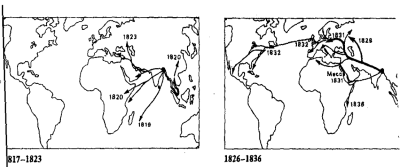

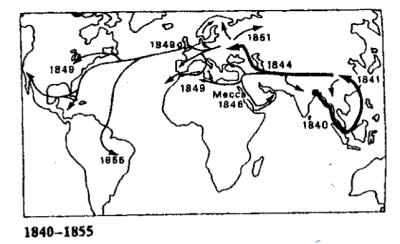

Cholera epidemics

Cholera is a striking example of how infectious diseases can spread on a global scale, facilitated by population movements and international trade. In the 19th century, cholera pandemics illustrated the increasing connectivity of the world, but also the limits of medical understanding and public health at the time. The spread of cholera began with British colonisation of India. The disease, which is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, was carried by merchant ships and troop movements, following the major trade and military routes of the time. The increase in international trade and the densification of transport networks enabled cholera to spread rapidly around the world. Between 1840 and 1855, during the first global cholera pandemic, the disease followed a route from India to other parts of Asia, Russia, and finally Europe and the Americas. These pandemics hit entire cities, causing massive deaths and exacerbating the fear and stigmatisation of foreigners, particularly those of Asian origin, perceived at the time as the vectors of the disease. This stigmatisation was fuelled by feelings of cultural superiority and notions of 'barbarism' attributed to non-European societies. In Europe, these ideas were often used to justify colonialism and imperialist policies, based on the argument that Europeans were bringing 'civilisation' and 'modernity' to parts of the world considered backward or barbaric. Cholera also stimulated major advances in public health. For example, it was by studying cholera epidemics that British physician John Snow was able to demonstrate, in the 1850s, that the disease was spread by contaminated water, a discovery that led to significant improvements in drinking water and sanitation systems.

Economic growth and social change in Europe during the 19th century were accompanied by fears and uncertainties about the consequences of modernisation. With rapid urbanisation, increasing population density in cities and often unsanitary conditions, European societies were confronted with new health risks. The theory that modernity enabled 'weak' individuals to survive was widespread, reflecting an understanding of the world influenced by Darwinian ideas of survival of the fittest. This perspective reinforced fears of a possible 'degeneration' of the population if infectious diseases were to spread among those deemed less resistant. The media coverage of epidemics played a crucial role in the public perception of health risks. News of the arrival of cholera or the first victims of the disease in a particular town was often accompanied by a sense of urgency and anxiety. Newspapers and broadsheets of the time carried this information, exacerbating fear and sometimes panic among the population. The disease also highlighted glaring social inequalities. Cholera disproportionately affected the poor, who lived in more precarious conditions and could not afford good hygiene or adequate food. This difference in mortality between social classes highlighted the importance of the social determinants of health. As for resistance to cholera thanks to a rich diet, the idea that gastric acids kill the cholera virus is partially true in the sense that a normal gastric pH is a defence factor against colonisation by vibrio cholerae. However, it is not a question of eating meat versus bread and potatoes. In fact, people who were malnourished or hungry were more vulnerable to disease, because their immune systems were weakened and their natural defences against infection were less effective. It is important to stress that cholera is not caused by a virus, but by bacteria, and that the survival of the micro-organism in the stomach depends on various factors, including the infectious load ingested and the person's general state of health. These epidemics have forced governments and societies to pay increased attention to public health, leading to investment in improved living conditions, sanitation and drinking water infrastructure, and ultimately to a reduction in the impact of such diseases.

The great epidemics that struck France and other parts of Europe after the revolutions of 1830 and 1848 took place against a backdrop of profound political and social upheaval. These devastating diseases were often perceived by the underprivileged classes as scourges exacerbated, or even provoked, by the miserable living conditions in which they were forced to live, often close to urban centres undergoing rapid expansion and industrialisation. In such a climate, it is not surprising that the suspicion and anger of the working classes was directed at the bourgeoisie, which was accused of negligence and even malice. Conspiracy theories such as the accusation that the bourgeoisie sought to "poison" or suppress "popular fury" through disease resonated with a population desperate for explanations for its suffering. In Russia, during the reign of the Tsar, demonstrations triggered by the distress caused by epidemics were put down by the army. These events reflect the tendency of the authorities of the time to respond to social unrest with force, often without addressing the root causes of discontent, such as poverty, health insecurity and lack of access to basic services. These epidemics highlighted the links between health conditions and social and political structures. They have shown that public health problems cannot be dissociated from people's living conditions, particularly those of the poorest classes. Faced with these health crises, pressure mounted on governments to improve living conditions, invest in health infrastructure and implement more effective public health policies. These periods of epidemics therefore also played a catalytic role in the evolution of political and social thought, underlining the need for greater equality and for governments to take better care of their citizens.

Nineteenth-century doctors were often at the heart of health crises, acting as figures of trust and knowledge. They were seen as pillars of the community, not least because of their commitment to the sick and their scientific training, acquired in higher education establishments. These health professionals had great influence and their advice was generally respected by the population. Before Louis Pasteur revolutionised medicine with his germ theory in 1885, understanding of infectious diseases was very limited. Doctors of the time were unaware of the existence of viruses and bacteria as pathogens. Despite this, they were not devoid of logic or method in their practice. When faced with diseases such as cholera, doctors used the knowledge and techniques available at the time. For example, they carefully observed the evolution of symptoms and adapted their treatment accordingly. They tried to warm patients during the "cold" phase of cholera, characterised by cold, bluish skin due to dehydration and reduced blood circulation. They also tried to fortify the body before the onset of the "last phase" of the disease, often marked by extreme weakness, which could lead to death. Physicians also used methods such as bloodletting and purging, which were based on medical theories of the time but are now considered ineffective or even harmful. However, despite the limitations of their practice, their dedication to treating patients and rigorously observing the effects of their treatments testified to their desire to combat disease with the tools at their disposal. The empirical approach of doctors of this era contributed to the accumulation of medical knowledge, which was subsequently transformed and refined with the advent of microbiology and other modern medical sciences.

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, known as Baron Haussmann, orchestrated a radical transformation of Paris during the Second Empire, under the reign of Napoleon III. His task was to remedy the pressing problems of the French capital, which was suffering from extreme overcrowding, deplorable sanitary conditions and a tangle of alleyways dating back to the Middle Ages that no longer met the needs of the modern city. Haussmann's strategy for revitalising Paris was comprehensive. He began by taking measures to clean up the city. Before his reforms, Paris struggled with plagues such as cholera, exacerbated by narrow streets and a poor sewage system. He introduced an innovative sewage system that greatly improved public health. Haussmann then focused on improving infrastructure by establishing a network of wide avenues and boulevards. These new thoroughfares were not just aesthetically pleasing but functional, improving the circulation of air and light and making it easier to get around. At the same time, Haussmann rethought the city's urban planning. He created harmonious spaces with parks, squares and alignments of facades, giving Paris the characteristic appearance we know today. However, this process had major social repercussions, notably the displacement of the poorest populations to the outskirts. The renovation work led to the destruction of many small businesses and precarious dwellings, forcing the poorer classes to move to the suburbs. These changes provoked mixed reactions among Parisians at the time. While the bourgeoisie might have feared social unrest and viewed with apprehension the presence of what they saw as the "dangerous classes", Haussmann's ambition was also to make the city more attractive, safer and better adapted to the times. Nevertheless, the cost and social consequences of Haussmann's work were a source of controversy and intense political debate.

The "social question"

During the 19th century, with the rise of industrial capitalism, social structures underwent radical changes, replacing the old hierarchy based on nobility and blood with one based on social status and wealth. A new bourgeois elite emerged, made up of individuals who, having succeeded in the business world, acquired the wealth and social credit deemed necessary to govern the country. This elite represented a minority who, for a time, held a monopoly on the right to vote, being considered the most capable of taking decisions for the good of the nation. The workers, on the other hand, were often seen in a paternalistic light, as children incapable of managing their own affairs or resisting the temptations of drunkenness and other vices. This view was reinforced by the moral and social theories of the time, which emphasised temperance and individual responsibility. Fear of cholera, a dreadful and poorly understood disease, fuelled a range of popular beliefs, including the idea that stress or anger could induce illness. This belief contributed to a relative calm among the working classes, who were wary of strong emotions and their potential to cause plagues. In the absence of a scientific understanding of the causes of such illnesses, theories abounded, some of them based on myth or superstition. In this environment, the bourgeoisie developed a form of paranoia about working-class suburbs. The urban peripheries, often overcrowded and unhealthy, were seen as hotbeds of disease and disorder, threatening the stability and cleanliness of the more sanitised urban centres. This fear was accentuated by the contrast between the living conditions of the bourgeois elite and those of the workers, and by the perceived threat to the established order posed by popular gatherings and revolts.

Buret was a keen observer of the living conditions of the working class in the 19th century, and his analysis reflects the social anxieties and criticisms of an era marked by the Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanisation: "If you dare to enter the cursed districts where [the working-class population] live, you will see at every step men and women withered by vice and misery, half-naked children rotting in filth and suffocating in dayless, airless rooms. There, in the home of civilisation, you will meet thousands of men who, by dint of stupefaction, have fallen back into the savage life; there, finally, you will see misery in such a horrible aspect that it will inspire more disgust than pity, and that you will be tempted to see it as the just punishment for a crime [...]. Isolated from the nation, placed outside the social and political community, alone with their needs and their miseries, they are agitating to get out of this frightening solitude, and, like the barbarians to whom they have been compared, they may be plotting an invasion".

The strength of this quotation lies in its graphic and emotional depiction of poverty and human degradation in the working-class districts of industrial cities. Buret uses shocking imagery to elicit a reaction from the reader, depicting scenes of degradation that stand in stark contrast to the ideal of progress and civilisation held by the times. By describing working-class neighbourhoods as "cursed" and evoking images of men and women "withered by vice and misery", he draws attention to the inhuman conditions created by the economic system of the time. The reference to "half-naked children rotting in the dirt" is particularly poignant, reflecting a cruel social reality in which the most vulnerable, children, were the first victims of industrialisation. The reference to "dayless, airless rooms" is reminiscent of the insalubrious, overcrowded dwellings in which working-class families were crammed. Buret also highlights the isolation and exclusion of workers from the political and social community, suggesting that, deprived of recognition and rights, they could become a subversive force, compared to "barbarians" plotting an "invasion". This metaphor of invasion suggests a fear of workers' revolt among the ruling classes, who feared that the distress and agitation of the workers would turn into a threat to the social and economic order. In its historical context, this quotation illustrates the deep social tensions of the 19th century and offers a scathing commentary on the human consequences of industrial modernity. It invites reflection on the need for social integration and political reform, recognising that economic progress cannot be disconnected from the well-being and dignity of all members of society.