十八世纪社会经济结构的演变: 从旧制度到现代性

根据米歇尔-奥利斯(Michel Oris)的课程改编[1][2]

地结构与乡村社会: 前工业化时期欧洲农民分析 ● 旧政体的人口制度:平衡状态 ● 十八世纪社会经济结构的演变: 从旧制度到现代性 ● 英国工业革命的起源和原因] ● 工业革命的结构机制 ● 工业革命在欧洲大陆的传播 ● 欧洲以外的工业革命:美国和日本 ● 工业革命的社会成本 ● 第一次全球化周期阶段的历史分析 ● 各国市场的动态和产品贸易的全球化 ● 全球移民体系的形成 ● 货币市场全球化的动态和影响:英国和法国的核心作用 ● 工业革命时期社会结构和社会关系的变革 ● 第三世界的起源和殖民化的影响 ● 第三世界的失败与障碍 ● 不断变化的工作方法: 十九世纪末至二十世纪中叶不断演变的生产关系 ● 西方经济的黄金时代: 辉煌三十年(1945-1973 年) ● 变化中的世界经济:1973-2007 年 ● 福利国家的挑战 ● 围绕殖民化:对发展的担忧和希望 ● 断裂的时代:国际经济的挑战与机遇 ● 全球化与 "第三世界 "的发展模式

18 世纪标志着人类历史进程中一个革命性时代的到来,它不可磨灭地塑造了欧洲乃至世界的未来。这个世纪介于古老传统与现代愿景之间,是一个充满对比和矛盾的十字路口。本世纪初,欧洲在很大程度上仍是一个农业社会,受祖传封建结构和世袭贵族权力与特权的统治。日常生活被农业周期所打断,绝大多数人生活在小型农村社区,以土地为生。然而,变革的种子已在地表下悄然萌发,蓄势待发。

随着世纪的推进,变革之风吹遍了整个大陆。启蒙哲学家倡导理性、个人自由和对传统权威的怀疑,他们的影响开始挑战既定秩序。文学沙龙、咖啡馆和报纸成为进步思想的阵地,激发了人们对社会、经济和政治改革的渴望。欧洲的经济活力也发生了根本性的转变。新耕作法和轮作法的引入提高了土地产量,促进了人口增长,增加了社会流动性。由于航海技术的进步和殖民扩张,国际贸易得到加强,阿姆斯特丹、伦敦和巴黎等城市成为热闹的商业和金融中心。工业革命虽处于萌芽阶段,但在 18 世纪末已初露端倪。技术革新,尤其是纺织业的技术革新,改变了生产方式,并将经济重心从农村地区转移到不断扩大的城市。水力发电以及后来的蒸汽机彻底改变了工业和交通,为大规模生产和更加工业化的社会铺平了道路。

然而,在这一增长和扩张时期,不平等现象也日益加剧。机械化往往导致体力劳动者失业,工业化城市的生活条件往往十分恶劣。国际贸易和美洲殖民化所带来的财富分配不均,剥削和不公正往往削弱了进步所带来的好处。法国大革命和美国独立战争等政治动荡展示了代议制政府的潜力和愿望,破坏了绝对君主制的基础,为现代共和制奠定了基础。民族国家的概念开始出现,重新定义了身份和主权。因此,18 世纪末是一个急剧转型的时期,旧世界逐渐让位于新结构和意识形态。这些变革的印记塑造了欧洲社会,确立了当代世界的前提,引发的辩论至今仍在我们的社会中产生共鸣。

结构和经济条件的概念

在经济和社会科学的行话中,"结构 "一词指的是构成和界定经济运行方式的持久特征和机构。这些结构要素包括法律、法规、社会规范、基础设施、金融和政治体制,以及所有权和资源分配模式。结构性要素被认为是稳定的,因为它们与社会和经济结构交织在一起,不会迅速或轻易发生变化。它们是经济活动的基础,对于理解经济如何以及为何以这种方式运行至关重要。

经济学中的均衡概念通常与经济学家莱昂-瓦尔拉斯(Léon Walras)有关,它是一种理论状态,在这种状态下,资源以尽可能最有效的方式进行分配,即供给满足需求,价格令生产者和消费者都满意。在这样的体系中,没有任何经济行为体有动力改变其生产、消费或交换策略,因为在现有条件下,所有人都能在给定的约束条件下实现效用最大化。然而,在现实中,经济很少(如果有的话)处于完全均衡状态。结构性变化,如十八世纪向更加工业化和资本主义经济体系的过渡,涉及经济结构演变和适应的动态过程。这一过程可能会被技术创新、科学发现、冲突、政府政策、社会运动或经济危机所破坏,所有这些都可能导致失衡,需要进行结构调整。经济学家研究这些结构变化,以了解经济如何发展和应对各种干扰,并为旨在促进稳定、增长和经济福祉的政策提供信息。

在资本主义的背景下,结构可以被认为是塑造和维持经济活动的一系列监管框架、机构、商业网络、市场和文化习俗。这种结构对于资本主义的正常运作至关重要,而资本主义的基础是私有制、资本积累以及商品和服务分配的竞争性市场。资本主义制度的结构完整性,即其组成部分和机构的稳健性和复原力,对其稳定性和自我调节能力至关重要。在这样一个体系中,每个要素--无论是金融机构、公司、消费者还是政府政策--都必须高效、自主地运作,同时与整个体系保持一致。从理论上讲,资本主义是一个自我调节的系统,在这个系统中,市场力量(主要是供求力量)的相互作用会导致经济平衡。例如,如果对某种产品的需求增加,价格往往会上涨,这意味着生产者有更大的动力去生产更多的产品,最终应能恢复供需平衡。然而,经济史表明,市场和资本主义体系并不总是能够自我纠正,有时会出现持续的失衡,如投机泡沫、金融危机或日益加剧的不平等。在这些情况下,系统中的一些要素可能无法有效或迅速地适应,从而导致不稳定,这可能需要外部干预,如政府监管或货币和财政政策,以恢复稳定。因此,尽管资本主义因其结构的灵活性和适应性而趋向于某种形式的平衡,但其运作的现实可能要复杂得多,往往需要谨慎的管理和监管,以避免功能失调。

旧制度的结构

直到 18 世纪末,欧洲一直处于旧政体时期,尤其是革命前的法国,其经济主要以农业为主。这种农业主导地位带有强烈的谷物单一种植特征,以小麦为生产标准。这种专业化反映了当时的基本粮食需求、气候和环境条件以及根植于传统的耕作方式。土地是财富的主要来源和社会地位的象征,导致社会经济结构僵化,不愿改变和采用新的耕作方法。旧制度下的农业生产力低下。由于使用传统耕作技术,土地产量有限,而且明显缺乏创新。在缺乏先进技术的情况下,三年轮作和依赖变化无常的大自然限制了农业效率。由于缺乏知识、资金和不重视农业创业精神的社会制度,投资于可改善现状的技术的情况很少见。

在人口统计方面,晚婚和长期独身的高比例等社会习俗维持着人口平衡,这些习俗在欧洲西北部尤为普遍。这些习俗,再加上婴儿死亡率高、饥荒或流行病频发,自然而然地调节了人口增长,尽管农业产量微薄。

交通和通信手段的发展也非常有限,导致经济以微型市场为特征。除了日内瓦生产的手表等高附加值产品外,高昂的运输成本使得远距离货物贸易成本过高。这些奢侈品面向富裕的客户群,可以承受运输成本而不影响其在远距离市场上的竞争力。

最后,旧政体时期的工业和手工业生产主要集中在日常消费品的制造上,这是由 "消费紧迫法则 "决定的,即吃喝拉撒的必需品。工业,尤其是纺织业,通常规模较小,分布在全国各地,受到行会的严格控制,限制了竞争和创新。这种有限的生产符合当时大多数人的迫切需要和经济能力。

这一系列特征决定了当时的经济和社会普遍维持现状,几乎没有创新和动态变化的空间。因此,与英国相比,旧政体结构的僵化在一定程度上推迟了法国等国进入工业革命的时间,而英国的社会和经济改革则为更迅速的现代化铺平了道路。

经济形势: 分析与影响

经济和社会历史的特点是增长与衰退、危机与复苏的长期循环。改变社会经济结构是一个艰巨的过程,尤其是因为这涉及到打破几个世纪以来形成的制度平衡。然而,这些结构并不是一成不变的,它们反映了一个不断发展的社会的持续动态,尽管这种发展的方式可能是微妙而复杂的。

危机往往是一个长期保持表面稳定的系统内部紧张关系累积的结果。灾难性事件会加剧这些紧张局势,迫使现有体系重组。危机还可能导致社会两极分化加剧,在社会适应和应对变革的过程中,赢家和输家更加分明。

潮起潮落,此起彼伏 "是对这些经济和社会周期的有力比喻。有些时期的人口或经济增长似乎被危机或萧条时期所逆转或抵消。这些 "潮起潮落 "是人类历史的特征,对它们的研究为我们了解塑造社会的力量提供了宝贵的视角。它还表明,社会系统具有内在的韧性,虽然经常面临 "崩溃",但能够恢复并重新崛起,尽管其方式与以前大不相同。每个周期都会带来变化、适应,有时还会对现有结构进行深刻变革。

经济增长的曙光

18 世纪的人口扩张在欧洲历史上前所未有。例如,英国的人口增长令人印象深刻,从世纪初的约 550 万增长到 19 世纪初的 900 万,增长了近 64%。这种人口增长是这一时期最显著的增长之一,反映了生活条件的改善以及技术和农业的进步。法国也不例外,其人口从 2200 万增至 2900 万,增长了 32%。这一增长率虽然没有英国那么惊人,但也反映了法国人口结构的重大变化,同时也得益于农业的改善和相对稳定的政治局势。就整个欧洲大陆而言,总人口增长了约 58%,考虑到欧洲在过去几个世纪中反复出现人口危机,这是一个了不起的数字。与以往时期不同的是,这种增长之后并没有出现重大的人口危机,如饥荒或大规模流行病,而这些危机可能会使居民人数大幅减少。

这些人口变化更为显著的是,它们是在没有传统的死亡率 "修正 "的情况下发生的,而死亡率 "修正 "历来伴随着人口的增长。造成这一现象的原因有很多:农业革命提高了农业产量,公共卫生事业取得了进步,工业革命的开始创造了新的就业机会并鼓励了城市化进程。这些人口增长在这一时期的经济发展和社会变革中发挥了至关重要的作用,为新兴工业提供了充足的劳动力,刺激了对制成品的需求,从而奠定了现代欧洲社会的基础。

18 世纪欧洲异常的人口增长可归因于一系列相互依存的因素,这些因素共同改变了欧洲大陆的社会经济格局。农业创新是这一增长的主要驱动力。从各大洲引进的农作物使欧洲人的饮食更加多样化和丰富。分别从拉丁美洲和亚洲引进的玉米和水稻改变了南欧的农业,特别是意大利北部,那里适应了密集型水稻种植。在北欧和西欧,马铃薯也发挥了类似的作用。与传统谷物相比,马铃薯在本世纪的迅速传播增加了卡路里的摄入量,并成为工人阶级的主食。贸易也对繁荣和人口增长作出了重大贡献,尤其是在不列颠群岛。特别是英国,它建立了一支强大的商船队,确立了自己 "世界贸易商 "的地位。工业革命的发展实现了商品的大规模生产,这些商品随后被运往欧洲大陆各地。1740 年,西欧遭遇歉收,英国凭借其船队从东欧进口小麦,避免了死亡危机,而海运不发达的法国则承受了小麦短缺的后果。荷兰也因其商船海军而享有相当大的商业实力。最后,经济结构的变化也产生了深远的影响。从家庭生产体系向原工业化的过渡创造了新的经济动力。在全面工业化之前,原工业化涉及小规模生产的增加,通常是农村生产的增加,这为工业革命奠定了基础,工业革命将地方经济转变为规模经济,扩大了生产和分销商品的能力。这些因素,再加上公共卫生的进步和对食物资源的更好管理,不仅使欧洲人口大幅增长,也为工业化和世界贸易成为全球经济支柱的未来铺平了道路。

国内体系或 Verlagsystem: 基础与机制

出版社制度是欧洲工业化的一个重要先驱。在 17 世纪至 19 世纪期间,这种制度是德国某些地区和欧洲其他地区的特色,它标志着手工劳动与后来占主导地位的工厂工业生产之间的中间阶段。在这一体系中,Verleger(通常是富有的企业家或商人)扮演着核心角色。他将必要的原材料分发给工人,这些工人通常是希望增加收入的手工业者或农民。这些工人利用自己家中的空间或当地的小作坊,按照 Verleger 提供的规格集中生产产品。他们按件计酬,而不是固定工资,这鼓励他们尽可能提高生产效率。货物生产出来后,Verleger 负责回收,必要时进行加工,然后在当地市场销售或出口。出版社系统促进了贸易的扩展,并使工作更加专业化。它在纺织业中尤为突出,服装、织物和丝带等产品都是在纺织业中批量生产的。

这种制度在当时有几个优点:它在劳动力方面提供了相当大的灵活性,使工人能够适应季节性需求和市场波动。它还允许企业家最大限度地降低固定成本,例如与维持大型工厂相关的成本,并绕过行会的一些限制,因为行会严格控制着城镇的生产和贸易。然而,Verlagsystem 并非没有缺陷。被捆绑在一块的工人可能会发现自己实际上依赖于出版社,很容易受到成品价格下降或原材料成本上升等经济压力的影响。随着工业革命的到来和工厂生产的发展,由于新机器的出现使生产速度更快、效率更高、规模更大,Verlagsystem 逐渐衰落。尽管如此,它仍是欧洲向工业经济转型的关键一步,并为一些现代生产原则奠定了基础。

16 世纪以来,家务制在欧洲纺织业尤为盛行。这是一种先于工业化的工作组织方式,涉及家庭的分散生产,而非工厂或车间的集中生产。在这种制度下,原材料被供应给家庭工人,他们通常是农民或希望赚取额外收入的家庭成员。这些工人使用简单的工具纺羊毛或棉花,织布或其他纺织品。这一过程通常由企业家或商人协调,他们提供原材料,并在生产后收集成品在市场上出售。这种工作方式对商人和工人都有好处。商人可以绕过城市行会的限制,因为城市行会对城镇的贸易和手工业进行严格管理。对工人来说,这意味着他们可以在家工作,这对农村家庭尤其有利,因为他们可以通过纺织品生产来补充农业收入。然而,家庭制度也有其局限性。生产速度往往很慢,产量也相对较小。此外,产品的质量也会有很大差异。随着时间的推移,这些缺点变得越来越明显,特别是当工业革命引入了更高效的机器和工厂生产时。动力织布机和纺纱机等机器的发明极大地提高了生产率,从而导致家庭生产方式的淘汰和工厂的兴起。因此,家务制是工业生产演变过程中的一个重要阶段,是传统手工艺与随后出现的大规模生产方式之间的桥梁。它见证了工业资本主义的最初阶段和更现代的市场经济的出现。

在工业化到来之前普遍存在的家庭体系,其特点是分散的生产结构以及手工业者和商人之间的动态关系。农民是这一体系的核心,他们在播种和收割等繁重的农活季节之外,将时间投入到手工业生产中,尤其是纺织业。这种模式为工人提供了一种补充收入不足的途径,同时保证了他们就业的灵活性。作为回报,商人也从负担得起、适应性强的劳动力中获益。商人在这一体系的经济组织中也扮演着举足轻重的角色。他们不仅为工匠提供所需的原材料,还负责分配工具和管理订单。他集中采购和分配资源的能力使他能够降低运输成本,并对生产和销售链进行控制。此外,商人根据订单调节工作进度,使供应适应需求,这种做法预示着现代资本主义的灵活性原则。总体而言,国内制度的特点是商人企业家占据主导地位,他们依靠间歇性的农业劳动力协调成品的生产和销售。这种制度逐渐演变,为更集中的生产方式和随后的工业革命铺平了道路。

在工业革命之前盛行的家庭制度中,农民的角色以高度的经济依赖性为特征。这取决于多个因素。首先,农民的生活受季节和农业周期的制约,这使得他们的收入不稳定且多变。因此,手工业生产(尤其是纺织业)提供了必要的收入补充,以弥补农业收入的不足。这种依赖具有双重性质:农民不仅以农业为主要生计,而且还依赖手工业提供的额外收入。其次,农民与商人之间的关系是不对称的。商人控制着原材料的分销和成品的销售,对农民的工作条件有相当大的影响。通过提供工具和下订单,商人主宰着工作流程,并间接决定着农民的收入水平。由于农民本身没有能力大规模推销自己的产品,这种依赖性更加严重,迫使他接受商人规定的条件。农民岌岌可危的经济地位加剧了他对商人的依赖。农民几乎没有机会谈判或改变他们的手工业工作条件,很容易受到需求波动和商人决定的影响。这种状况一直持续到工业化时代的到来,工业化从根本上改变了社会的生产方式和经济关系。

从中世纪到近代,纺织行会都是强有力的机构,在调节商品的生产和质量,以及为其成员提供经济和社会保护方面发挥着至关重要的作用。当被称为 "Verlagsystem "或 "put-out system "的分散生产系统开始发展时,它提供了另一种模式,即商人将工作外包给在自己家中工作的工匠和农民。由于种种原因,这种新模式与传统行会之间产生了巨大的矛盾。公司建立在严格的培训、生产和销售规则之上。它们对质量实行高标准,并保证其成员享有一定的生活水平,同时限制竞争以保护当地市场。然而,Verlagsystem 的运作却不受这些规定的限制。商人们可以绕过行会的限制,以更低的成本提供产品,而且往往规模更大。对于行会来说,这种生产方式是不公平的竞争,因为它不遵守同样的规则,可能会威胁到行会对纺织品生产和销售的经济垄断。因此,企业经常试图限制或禁止 Verlagsystem 的活动,以维护自己的做法和优势。这种反对有时会导致公开冲突,并试图引入更严格的法规来遏制该系统的扩张。尽管如此,出版社制度还是得到了发展,尤其是在那些实力较弱或企业较少的地方,这预示着工业革命所带来的经济和社会变革。

随着国内制度的出现,生产组织为农业劳动力的管理提供了创新。这种制度使农民能够利用农闲时间为商人或制造商打零工。这样,农民就成了商人廉价而灵活的劳动力,可以适应需求的波动,而不受全职工作的限制。尽管有了这种创新,家政制度仍然是一种相对边缘化的现象,并没有产生资本主义商人所期望的变革性影响。后者拥有购买原材料所需的资本,通常以最低价格向农民支付劳动报酬,然后在市场上出售成品。这代表了商业资本主义的早期形式,但这种经济模式遇到了一个主要障碍:需求疲软。当时的社会和经济现实是一个 "大众苦难社会",饥荒司空见惯,消费仅限于最基本的必需品。例如,人们买衣服是为了穿得更久,而且是修补和重复使用,而不是更换。大众消费需要一定的购买力,而除了贵族、资产阶级和神职人员等少数群体外,大多数人根本不具备这种购买力。因此,尽管有创新的一面,国内制度并没有显著增长,部分原因是需求疲软和总体购买力有限。这使得经济体系陷入了 "僵局",如果市场需求没有随之增长,仅靠技术和组织方面的进步是无法推动经济更广泛发展的。

原工业化的出现

原工业主要是在工业革命之前发展起来的,是传统农业经济与工业经济之间的中间阶段。这种经济组织形式出现在欧洲,特别是在农村地区,农民们在种植和收获季节之外寻求补充收入。在这种体系下,生产不像后来工业时代的工厂那样集中进行,而是分散在许多小作坊或家庭中。手工业者和小生产者通常以家庭为单位,专门生产纺织品、陶器或金属等特定产品。这些商品随后被商人收集起来,由他们负责分销到更广阔的市场,通常远远超出当地市场的范围。

原工业化意味着一种混合经济,其中农业仍是主要活动,但制成品的生产在其中扮演着越来越重要的角色。这一时期的特点是劳动分工仍然初级,专业机械的使用有限,但它为后来的工业化发展奠定了基础,特别是使部分人口习惯于从事农业以外的工作,刺激了商品生产技能的发展,并促进了为规模更大、技术更先进的企业提供资金所需的资本积累。

富兰克林-门德尔斯(1972 年): 关于 18 世纪佛兰德斯的论文

Franklin Mendels conceptualised the term 'proto-industrialisation' to describe the evolutionary process that took place in the European countryside, particularly in Flanders, during the 18th century, foreshadowing the Industrial Revolution. His thesis highlights the coexistence of agriculture with the small-scale production of manufactured goods in peasant households. This dual economic activity enabled rural families to increase their income and reduce their vulnerability to agricultural hazards. According to Mendels, proto-industrialisation was characterised by a scattered distribution of manufactured production, often carried out in small workshops or within households, rather than in large, concentrated factories. Farmers were often dependent on local merchants who supplied the raw materials and took care of marketing the finished products. This system stimulated productivity and promoted efficiency in the production of manufactured goods, which in turn boosted the economy of the regions concerned. This period also saw significant changes in family and social structures. Farming families adapted by adopting economic strategies that combined agriculture and manufacturing. This had the effect of familiarising the workforce with manufacturing activities and weaving distribution networks for the goods produced, thereby facilitating the accumulation of capital. Proto-industrialisation therefore not only changed the economic landscape of these regions, but also had an impact on their demography, social mobility and family relations, laying the foundations for modern industrial societies.

At the end of the 17th century, population growth in Europe led to significant changes in the social composition of the countryside. This demographic growth led to the distinction of two main groups within the rural population. On the one hand, there were the landless peasants. This group was made up of people who did not own any agricultural plots and who often depended on seasonal or day labour to survive. These people were particularly vulnerable to economic fluctuations and poor harvests. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution, they were to become an essential workforce, often described as the 'reserve army' of industrial capitalism, as they were available to work in the new factories and plants due to their lack of ties to the land. On the other hand, there were the peasants who, faced with demographic pressure and the increasing scarcity of available land, sought alternative sources of income. These peasants began to turn to non-agricultural activities, such as craft production or work at home within the framework of systems such as the domestic system or proto-industrialisation. In this way, they contributed to the economic diversification of the countryside and to preparing rural populations for the industrial transformations to come. These dynamics led to a socio-economic reorganisation of the countryside, with an impact on the traditional structures of agriculture and a growing involvement of rural areas in the wider economic circuits of trade and manufacturing production.

Characteristics of the Proto-industry ("Putting-Out System")

The eighteenth century was a period of profound economic transformation in Europe, and particularly in regions such as Flanders. The economic historian Franklin Mendels, in his landmark thesis on eighteenth-century Flanders, identified several key elements that characterised proto-industry, a system that paved the way for the Industrial Revolution. One of Mendels' most surprising findings is that, unlike earlier periods in history, population growth in the eighteenth century was mainly centred in the countryside rather than the towns. This marks a reversal of historical demographic trends in which cities were usually the engines of growth. This expansion of the rural population led to a surplus of labour available for new forms of production. Furthermore, Mendels identified that the basic economic unit during this period was neither the town nor the village, but rather the household. The household functioned as the nucleus of production and reproduction. Rather than relying solely on agriculture, rural families diversified their activities by taking part in proto-industrial production, often as part of the domestic system. These households produced goods at home, such as textiles, for merchants or entrepreneurs who supplied them with raw materials and collected the finished products for sale. This economic structure allowed greater flexibility and adaptability to fluctuations in demand and the seasons, contributing to sustained economic growth that would eventually lead to the Industrial Revolution. Protoindustry was therefore a key factor in economic growth in the 18th century, preparing rural populations for the major changes that were to come with industrialisation.

Franklin Mendels' meticulous studies of eighteenth-century Flanders offer a detailed insight into the economic and social dynamics of rural Western Europe. By analysing the archives of some 5,000 households, Mendels was able to identify three distinct social groups, whose growth reflected the tensions and changes of the time. The landless peasants were a growing group, a direct consequence of population growth that outstripped the capacity of the land to provide for everyone. With inheritance practices dividing the land between several heirs, many farms became unviable and went bankrupt. These farmers were under pressure from demographic and economic imperatives, sometimes leading to bankruptcy. For some, working for large landowners was an option, while others would become what Marx called "the reserve army of capitalism", ready to join the workforce of nascent industry in their desperate search for work. A second group was made up of peasants who chose to emigrate to avoid the excessive subdivision of their family plot of land and the consequent dilution of income. These peasants sought economic opportunities in town or even abroad, often on a seasonal basis, establishing migration patterns that became common in the eighteenth century. Finally, there were those who remained attached to their land but were forced to innovate in order to survive. This group adopted proto-industry, combining agricultural work with small-scale industrial production, often in the home. By integrating these new forms of production, they managed to maintain their rural lifestyle while generating the additional income needed to support their families. These three social groups, observed by Mendels, illustrate the complexity and diversity of the responses to the economic and demographic challenges of the time, and their central role in the transformation of pre-industrial rural society.

Proto-industry represents an intermediate phase of economic development that took place mainly in the countryside, characterised by a system of home-based work. It is a form of rural craft industry that remains largely invisible in traditional economic statistics, as it takes place in the interstices of agricultural time. The workers, often peasants, use the periods when farming requires less attention to engage in production activities such as spinning or weaving, enabling them to diversify their sources of income. The proto-industrial system is perfectly compatible with the seasonal rhythm of farming, as it capitalises on the slack periods in agriculture. In this way, farmers can continue to meet their food needs through agriculture while increasing their income through proto-industrial activities. In the event of a poor harvest and rising wheat prices, the additional income generated by the proto-industry provides economic security, enabling them to buy food. Conversely, if a crisis hits the textile sector, agricultural harvests can provide a guarantee against famine. The duality of this economy therefore offers a degree of resilience in the face of crises, since the survival of farmers does not depend exclusively on a single sector. Only the misfortune of a simultaneous crisis in the agricultural and proto-industrial sectors could threaten their livelihoods, a rare occurrence historically. This demonstrates the strength of a diversified economic system, even at the microeconomic level of the rural household.

The introduction of a second source of income marked a significant turning point in the lives of farmers. Although poverty continued to be widespread and the majority of people lived on modest means, the ability to generate additional income through proto-industry helped to reduce the precariousness of their existence. This diversification of income has led to greater economic security, reducing farmers' vulnerability to seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of agriculture. So, even if the overall standard of living did not rise spectacularly, the impact on the security and stability of rural households was substantial. Families were better able to cope with years of poor harvests or periods of rising food prices. What's more, this greater security could translate into a certain improvement in social well-being. With the extra income, families potentially had access to goods and services they would not otherwise have been able to afford, such as better clothes, tools, or even education for their children. In short, proto-industry played a fundamental role in improving the condition of peasants by providing them with a safety net that went beyond subsistence and paved the way for the social and economic changes of the Industrial Revolution.

Triangular Trade: An Overview

The integration of proto-industry into world trade marked a significant transformation of the global economy. This system, also known as the putting-out system or domesticity system, paved the way for rural producers to participate fully in the market economy by manufacturing goods for export. This development has had a series of interconnected consequences. Proto-industry led to a significant increase in demand for manufactured goods, partly thanks to the establishment of triangular trade. The latter refers to a trade circuit between Europe, Africa and the Americas, where goods produced in Europe were exchanged for slaves in Africa, who were then sold in the Americas. Raw materials from the colonies were brought back to Europe to be processed by the proto-industry.

This trade fuelled the accumulation of capital in Europe, which subsequently financed the Industrial Revolution. In addition, the expansion of markets for proto-industrial goods beyond local borders fostered the emergence of a more integrated, globalised market economy. Economic structures began to change, as proto-industry paved the way for the Industrial Revolution by directing producers to produce for the market and not just for personal subsistence. However, it is essential to recognise that the triangular trade also included the slave trade, a profoundly inhumane aspect of this historical period. Economic advances sometimes came at the cost of great human suffering, and although the economy prospered, it did so with irreparable damage to many lives, the impact of which is still felt today.

Proto-industry, often confused with the domestic system, differs from the latter in its scale and economic impact. Proto-industry affected a large number of farmers, with few agricultural regions spared by the phenomenon. This widespread diffusion is mainly due to the transition of rural producers from local micro-markets to a global economy, enabling them to export their products. The export of goods such as textiles, weapons and even items as basic as nails has considerably increased global demand and stimulated economic growth. This expansion of markets was also the driving force behind triangular trade. This system saw the products of proto-industry in Europe traded for slaves in Africa, who were then transported to the Americas to work in plantation economies producing cotton, sugar, coffee and cocoa, which were eventually exported to Europe. This trade flow not only contributed to an increase in demand for proto-industrial goods, but also led to an increase in shipbuilding work, a sector that provided employment for millions of peasants, reducing transport costs and promoting sustained economic growth. However, it is important to remember that the triangular trade was based on slavery, a deeply tragic and inhumane system, the after-effects of which are still present in modern society. The economic growth it generated is inseparable from these painful historical realities.

The relationship between population growth and proto-industry in the 18th century is a complex question of cause and effect that has been widely debated by economic historians. On the one hand, population growth can be seen as an incentive to seek new forms of income, leading to the development of proto-industry. With a growing population, particularly in the countryside, land is becoming insufficient to meet everyone's needs, forcing farmers to find additional sources of income, such as proto-industrial work that can be carried out at home and does not require extensive travel. On the other hand, proto-industry itself has been able to encourage demographic growth by improving the standard of living of rural families and enabling them to provide better for their children. Access to additional off-farm income has probably reduced mortality rates and enabled families to support more children into adulthood. In addition, as incomes increased, populations were better nourished and more resistant to disease, which could also contribute to population growth. Proto-industry thus represents a transitional phase between traditional economies, based on small-scale agriculture and crafts, and the modern economy characterised by industrialisation and the specialisation of labour. It has enabled the integration of rural economies into international markets, leading to an increase in production and a diversification of sources of income. This has had the effect of boosting local economies and integrating them into the expanding global trade network.

The demographic effects

Impact on Mortality

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, Europe underwent a significant demographic transformation, characterised by a fall in mortality, thanks in part to a series of improvements and changes in society. Advances in agriculture led to increased food production, reducing the risk of famine. At the same time, advances in hygiene and public health initiatives have begun to reduce the spread of infectious diseases. Although major advances in medicine would not come until the end of the 19th century, some early discoveries had already had a positive impact on health. In addition, proto-industrialisation created additional income opportunities outside agriculture, enabling families to better withstand periods of poor harvests and improve their standard of living, including their access to quality food and healthcare. This era also saw a change in economic and social structure, with families now able to afford to marry earlier and bring up more children thanks to greater economic security. Home-based industrial work, such as textiles, offered additional financial security which, combined with farming, provided a more stable and diversified income. This helped to erode the old demographic regime where marriage was often delayed for lack of economic resources. The convergence of these factors therefore played a role in reducing mortality crises, leading to sustained demographic growth and a transformation of mentalities and lifestyles. Proto-industrialisation, by providing additional income and economic stability, was a key element in this transition, although its influence varied greatly from region to region.

Influence on Age at Marriage and Fertility

Proto-industrialisation had an impact on the social and economic structure of rural societies, and one of these effects was a lowering of the age at marriage. Before this period, many small farmers had to delay marriage until they could afford to support a family, as their resources were limited to what their land could produce. With the advent of proto-industrialisation, these small farmers were able to supplement their income with home-based industrial activities, such as weaving, which became increasingly in demand as the market expanded. This new source of income made marriage more accessible at a younger age, as couples could count on additional income to support themselves. What's more, in this new economic model, children represented an additional workforce that could contribute to the family income from an early age. They could, for example, work on the looms at home. This meant that families had an economic incentive to have more children, and that children could contribute economically long before they reached adulthood. This dynamic reinforced the economic viability of marriage and the extended family, allowing an increase in the birth rate and contributing to accelerated population growth. This demographic transition had profound repercussions on society, eventually leading to structural changes that paved the way for full industrialisation and economic modernisation.

The phenomenon of proto-industrialisation had varying effects on marital behaviour and fertility, depending on the region. In areas where proto-industrialisation provided significant additional income, people began to marry earlier and fertility increased accordingly. The ability to supplement agricultural incomes with those from home-based industrial work reduced the economic barriers to early marriage, as families could feed more mouths and support larger households. However, in other regions, economic prudence prevailed and peasants tended to postpone marriage until they had accumulated sufficient resources to become landowners. The acquisition of land was often seen as a guarantee of economic security, and peasants preferred to postpone marriage and the creation of a family until they could ensure a certain degree of material stability. This regional difference in marriage behaviour reflects the diversity of economic strategies and cultural values that influenced peasants' decisions. While proto-industrialisation offered new opportunities, responses to these opportunities were far from uniform and were often shaped by local conditions, traditions and individual aspirations.

Transforming Human Relationships: Body and Environment

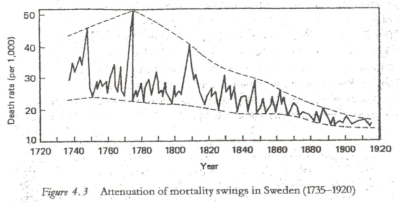

The graph shows the mortality rate per 1,000 individuals on the y-axis and the years from 1720 to 1920 on the x-axis. A clear trend can be seen on the graph: the mortality rate, which shows wide fluctuations with high peaks in the early years (particularly around 1750 and just before 1800), gradually flattens out over time, with the peaks becoming less pronounced and the overall mortality rate falling. The dotted line represents a trend line indicating the general downward trajectory of the mortality rate over this two-century period. This visual representation suggests that, over time, the instances and severity of mortality crises (such as epidemics, famines and wars) have decreased, due to improvements in public health, medicine, living conditions and changes in social structures.

Evolution of the Perception of Death

The change in the perception of death in the West between the 16th and 18th centuries reflects a profound transformation in mentality and culture. In the 16th and 17th centuries, high mortality rates and frequent epidemics made death a constant and familiar presence in daily life. People were used to coexisting with death, both as a community and as individuals. Cemeteries were often located in the heart of villages or towns, and the dead were an integral part of the community, as evidenced by rituals and commemorations. However, in the 18th century, particularly with advances in medicine, hygiene and social organisation, mortality began to decline, and with it, the omnipresent presence of death. This reduction in daily mortality led to a transformation in the perception of death. It was no longer perceived as a constant companion, but rather as a tragic and exceptional event. Cemeteries were moved outside inhabited areas, signifying a physical and symbolic separation between the living and the dead. This "distancing" of death coincides with what many historians and sociologists consider to be the beginning of Western modernity. Attitudes turned to valuing life, progress and the future. Death became something to be fought, pushed back and, ideally, conquered. This change in attitude has also led to a certain fascination with death, which has become a subject of philosophical, literary and artistic reflection, reflecting a certain anxiety in the face of the unknown and the inevitable. This new vision of death reflects a wider shift in human understanding of ourselves and our place in the universe. Life, health and happiness have become central values, while death has become a limit to be pushed back, a challenge to be met. This has had a profound influence on cultural, social and even economic practices, and continues to shape the way contemporary society approaches the end of life and bereavement.

The decline in mortality in the eighteenth century and changes in perceptions and practices around death have had consequences for many aspects of social life, including criminal justice and execution practices. In medieval and early modern times, public executions were commonplace and often accompanied by torture and particularly brutal methods. These executions had a social and political function: they were supposed to be a deterrent, a warning to the population against breaking the law. They were often staged with a high degree of cruelty, reflecting the era's familiarity with violence and death. However, in the eighteenth century, under the influence of the Enlightenment and a new sensitivity towards human life and dignity, there was a transformation in legal and punitive practices. Philosophers of the Enlightenment, such as Cesare Beccaria in his work "Of Crimes and Punishments" (1764), argued against the use of torture and cruel punishments, pleading for a more rational and humane form of justice. Against this backdrop, public executions began to be called into question. They were gradually seen as barbaric and uncivilised, and in contradiction with society's new values. This change in perspective led to reforms in the penal system, with a trend towards more "humane" executions and, ultimately, the abolition of public executions. Execution, rather than being a public spectacle of torture, became a swift and less painful act, with the aim of ending the life of the condemned person rather than inflicting prolonged suffering. The introduction of methods such as the guillotine in France at the end of the 18th century was partly justified by the idea of a quicker and less inhumane execution. The decline in mortality and the accompanying changes in mentality played a part in the transformation of judicial practices, leading to the reduction and eventually the cessation of public executions and associated torture, reflecting a gradual humanisation of society and its institutions.

In the eighteenth century, cemeteries began to be moved out of towns, a sign of a profound transformation in the way society viewed death and the dead. For centuries, the dead had been buried close to churches, in the very heart of communities, but this began to change for a variety of reasons.

Public health concerns gained in importance with increasing urbanisation. Overcrowded cemeteries in towns and cities were seen as potential health threats, especially in times of epidemics. This realisation led the authorities to rethink the organisation of urban spaces to limit health risks. The influence of the Enlightenment also encouraged a new approach to death. It was no longer an everyday spectacle, but a personal and private matter. There was a growing tendency to see death rites and mourning as something to be experienced more intimately, away from the public eye. At the same time, conceptions of the individual were evolving. More dignity was being accorded to the human person, both living and dead, and this translated into a need for funeral spaces that treated the remains with respect and decency. The spirit of rationalism at the time also played a role. There was a greater belief in man's ability to manage and control his environment. Moving cemeteries was a way of reorganising space to improve collective well-being, by bringing the layout of the city into line with the principles of rationality and progress. Moving cemeteries was a concrete expression of a move away from death in everyday life, reflecting a desire to manage it in a more methodical way, and showed a growing respect for the dignity of the dead, while marking a step towards greater control over the environmental factors affecting public life.

The Fight Against Diseases: Progress and Challenges

The externalisation of death in the eighteenth century reflects a period when perspectives on life, health and disease began to change significantly. Enlightenment man, armed with a new faith in science and progress, began to believe in his ability to influence, and even control, his environment and his health. Smallpox was one of the most devastating diseases, causing regular epidemics and high mortality rates. Edward Jenner's discovery of immunisation at the end of the 18th century was a revolution in terms of public health. By using the smallpox vaccine, Jenner proved that it was possible to prevent a disease rather than simply treating it or suffering its consequences. This marked the beginning of a new era in which preventive medicine became an achievable goal, reinforcing the impression that humanity could triumph over the epidemics that had decimated entire populations in the past. This victory over smallpox not only saved countless lives but also reinforced the idea that death was not always inevitable or a fate to be accepted without a struggle. It symbolised a turning point when death, once inextricably woven into everyday life and accepted as an integral part of it, began to be seen as an event that could be postponed, managed and, in some cases, avoided thanks to advances in medicine and science.

Smallpox was one of the most feared diseases before the first effective methods of prevention were developed. The disease has had a profound impact on societies throughout the centuries, causing mass deaths and leaving those who survive often with serious physical after-effects. The metaphor that smallpox took over from the plague illustrates the constant burden of disease within populations before the modern understanding of pathology and the advent of public health.

The observation that humanity could not have withstood two simultaneous plagues such as the plague and smallpox highlights the vulnerability of the population to infectious diseases before the 18th century. The case of famous figures such as Mirabeau, who was disfigured by smallpox, is a reminder of the terror that this disease inspired. Despite the ignorance of what a virus was at the time, the eighteenth century marked a time of transition from superstition and powerlessness in the face of disease to more systematic and empirical attempts to understand and control it. Practices such as variolisation, which involved the inoculation of an attenuated form of the disease to induce immunity, were developed long before science understood the underlying mechanisms of immunology. It was Edward Jenner who, at the end of the 18th century, developed the first vaccination, using pus from cowpox (vaccinia) to immunise against human smallpox, with significantly safer results than traditional variolisation. This discovery was not based on a scientific understanding of the disease at molecular level, which would only come much later, but rather on empirical observation and the application of experimental methods. The victory over smallpox thus symbolised a decisive turning point in humanity's fight against epidemics, paving the way for future advances in vaccination and the control of infectious diseases, which were to transform public health and human longevity in the centuries that followed.

Inoculation, practised before vaccination as we know it, was a primitive form of smallpox prevention. This practice involved the deliberate introduction of the smallpox virus into the body of a healthy person, usually through a small incision in the skin, in the hope that this would result in a mild infection but sufficient to induce immunity without causing full-blown disease. In 1721, the practice of inoculation was introduced to Europe by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who discovered it in Turkey and brought it to England. She inoculated her own children. The idea was that inoculation with an attenuated form of the disease would provide protection against subsequent infection, which could be much more severe or even fatal. This method had significant risks. Inoculated individuals could develop a full form of the disease and become vectors for smallpox transmission, contributing to its spread. In addition, there was mortality associated with the inoculation itself, although this was lower than the mortality from smallpox in its natural state. Despite its dangers, inoculation was the first systematic attempt to control an infectious disease by immunisation, and it laid the foundations for the later vaccination practices developed by Edward Jenner and others. The acceptance and practice of inoculation varied, with much controversy and debate, but its use marked an important step in the understanding and management of smallpox before vaccination with Jenner's safer and more effective vaccine became common in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In 1796, Edward Jenner, an English physician, achieved a major medical breakthrough when he perfected vaccination against smallpox. Observing that milkmaids who had contracted vaccinia, a disease similar to smallpox but much less severe, transmitted by cows, did not contract human smallpox, he postulated that exposure to vaccinia could confer protection against human smallpox. Jenner tested his theory by inoculating James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy, with pus taken from vaccinia lesions. When Phipps subsequently resisted exposure to smallpox, Jenner concluded that inoculation with vaccinia (what we now call vaccinia virus) offered protection against smallpox. He called this process "vaccination", from the Latin word "vacca" meaning "cow". Jenner's vaccine proved to be much safer than previous methods of inoculating against smallpox, and was adopted in many countries despite the wars and political tensions of the time. Despite the ongoing conflict between England and France, Jenner ensured that his vaccine reached other nations, including France, illustrating a remarkable early understanding of public health as a transnational concern. This breakthrough symbolised a turning point in the fight against infectious diseases. It laid the foundations of modern immunology and represented a significant first step towards conquering the epidemic diseases that had afflicted humanity for centuries. The practice of vaccination spread and eventually led to the eradication of smallpox in the twentieth century, marking the first time that a human disease had been eliminated through coordinated public health efforts.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries marked a fundamental change in the attitude of Western societies towards nature. With the decline in mortality from diseases such as smallpox and the increase in scientific knowledge, nature was gradually transformed from an indomitable and often hostile force into a set of resources to be exploited and understood. The Age of Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason and the accumulation of knowledge, led to the creation of encyclopaedias and the wider dissemination of knowledge. Figures such as Carl Linnaeus worked to classify the natural world, imposing a human order on the diversity of living things. This period saw the rise of a scholarly culture in which the exploration, classification and exploitation of nature were seen as ways of improving society. It was also at this time that the first concerns about the sustainability of natural resources began to emerge, in response to the acceleration of industrial exploitation. Debates about deforestation for shipbuilding, coal and mineral extraction, and other intensive exploitation activities reflect an emerging awareness of environmental limits. The anthropocentrism of the time, which placed man at the centre of all things and as master of nature, stimulated industrial and economic development. Over time, however, it also led to a growing awareness of the environmental and social effects of this approach, laying the foundations for the ecological and conservation movements that would later emerge. Thus, the development of a scholarly culture and the valuing of nature not only as an object of study but also as a source of material wealth were key elements in changing humanity's relationship with its environment, a relationship that continues to evolve in the face of contemporary environmental challenges.

The culture of nature

Hans Carl von Carlowitz, a Saxon mining administrator, is often credited with being one of the first to formulate the concept of sustainable management of natural resources. In his 1713 work "Sylvicultura oeconomica", he developed the idea that only as much wood should be cut as the forest can naturally reproduce, to ensure that forestry remains productive in the long term. This thinking was largely a response to massive deforestation and the growing need for wood for the mining industry and as a building material. Hans Carl von Carlowitz is credited with pioneering the concept of sustainability, particularly in the context of forestry. In this book, he set out the need for a balanced approach to forestry, which takes into account the regeneration of trees alongside their harvesting, in order to maintain forests for future generations. This was in response to the wood shortages facing Germany in the 18th century, largely due to over-exploitation for mining and smelting activities. The publication is significant because it laid the foundations for the sustainable management of natural resources, in particular the practice of planting more trees than are cut down, which is a cornerstone of modern sustainable forestry practices. Remarkably, the idea of sustainability was conceptualised over 300 years ago, reflecting an early understanding of the environmental impact of human activity and the need for resource conservation.

Although von Carlowitz's concerns centred on forestry and timber use, his idea reflects a basic principle of modern sustainable development: the use of natural resources should be balanced by practices that ensure their renewal for future generations. At the time, this was an avant-garde concept, as it ran counter to the widespread idea of the unlimited exploitation of nature. However, the notion of sustainable development did not immediately take root in public policy or in the collective consciousness. It was only with the development of environmental sciences and the social changes of the following centuries that the idea of prudent management of the Earth's resources became fully established.

The modern era, particularly from the 18th century onwards, was marked by a fundamental change in humanity's relationship with nature. The scientific revolution and the Enlightenment helped to promote a vision of man as master and possessor of nature, an idea philosophically supported by thinkers such as René Descartes. From this perspective, nature is no longer an environment in which man must find his place, but a reservoir of resources to be used for his own development. Anthropocentrism, which places the human being at the centre of all concerns, becomes the guiding principle for the exploitation of the natural world. According to the religious and cultural beliefs of the time, the earth was seen as a gift from God to the people who were responsible for cultivating and exploiting it. Developments in agronomy and forestry were manifestations of this approach, seeking to optimise the use of soil and forests for maximum production. Voyages of exploration, fuelled by a desire for discovery but also by economic motivations, also reflected this desire to exploit new resources and extend the sphere of human influence. This learned culture of nature was expressed through the creation of classification systems for the natural world, improved cultivation techniques, more efficient mining and regulated forestry. Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, for example, aimed to compile all human knowledge, including knowledge of nature, and make it accessible for rational and enlightened use. It was this approach that laid the foundations for the industrial use of natural resources, foreshadowing the industrial revolutions that were to profoundly transform human societies and their relationship with the environment. However, the large-scale exploitation of nature without consideration for long-term environmental impacts would later lead to the ecological crises we are experiencing today, and to the questioning of anthropocentrism as such.

Annexes

- Vieux Paris, jeunes Lumières, par Nicolas Melan (Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2015) Monde-diplomatique.fr,. (2015). Vieux Paris, jeunes Lumières, par Nicolas Melan (Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2015). Retrieved 17 January 2015, from http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2015/01/MELAN/51961

- Grober, Ulrich. "Hans Carl Von Carlowitz: Der Erfinder Der Nachhaltigkeit | ZEIT ONLINE." ZEIT ONLINE. 25 Nov. 1999. Web. 24 Nov. 2015 url: http://www.zeit.de/1999/48/Der_Erfinder_der_Nachhaltigkeit.