|

|

| (3 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) |

| Ligne 17 : |

Ligne 17 : |

| }} | | }} |

|

| |

|

| During the 19th century, Europe witnessed a profound metamorphosis - the Industrial Revolution - marked by unprecedented economic growth and a drive towards modernity. However, this period of growth and innovation was also synonymous with tumultuous social transformations and considerable humanitarian challenges. Delve into the English towns of the 1820s, walk through the steaming workshops of Le Creusot in the 1840s, or peer into the darkened alleys of East Belgium in the 1850s, and you'll see a striking contrast: technological progress and prosperity rubbed shoulders with exacerbated precariousness and chaotic urbanisation.

| | 19 世纪,欧洲经历了一场深刻的变革--工业革命,其标志是前所未有的经济增长和现代化进程。然而,这一增长和创新时期也伴随着动荡的社会变革和巨大的人道主义挑战。深入 19 世纪 20 年代的英国城镇,漫步于 19 世纪 40 年代勒克鲁索热气腾腾的车间,或窥探 19 世纪 50 年代比利时东部阴暗的小巷,你会发现一个鲜明的对比:技术进步和繁荣与加剧的不稳定性和混乱的城市化并存。 |

|

| |

|

| Rampant urbanisation, insalubrious housing, endemic diseases and deplorable working conditions defined the daily lives of many workers, with life expectancy dropping dramatically to 30 years in industrial centres. Hardy and bold people left the countryside to throw themselves into the arms of voracious industry, contributing to a relative improvement in mortality in rural areas, but at the cost of an overwhelming urban existence. The deadly influence of the environment was even more pernicious than the rigours of factory work.

| | 猖獗的城市化、肮脏的住房、地方病和恶劣的工作条件决定了许多工人的日常生活,工业中心的预期寿命急剧下降至 30 岁。勤劳勇敢的人们离开农村,投入贪婪的工业怀抱,使农村地区的死亡率有了相对改善,但代价是城市的生存环境不堪重负。环境的致命影响甚至比工厂的严酷工作更为有害。 |

|

| |

|

| In the midst of this era of glaring inequality, epidemics such as cholera highlighted the failings of modern society and the vulnerability of underprivileged populations. The social and political reaction to this health crisis, from the repression of workers' movements to the bourgeois fear of insurrection, revealed a growing divide between the classes. This division was no longer dictated by blood, but by social status, reinforcing a hierarchy that further marginalised the workers.

| | 在这个明显不平等的时代,霍乱等流行病凸显了现代社会的缺陷和弱势群体的脆弱性。对这场健康危机的社会和政治反应,从镇压工人运动到资产阶级对暴动的恐惧,揭示了阶级之间日益加剧的鸿沟。这种分化不再由血缘决定,而是由社会地位决定,强化了等级制度,使工人进一步边缘化。 |

|

| |

|

| Against this backdrop, the writings of social thinkers like Eugène Buret become poignant testaments to the industrial age, expressing both criticism of an alienating modernity and hope for a reform that would integrate all citizens into the fabric of a fairer political and social community. These historical reflections offer us a perspective on the complexity of social change and the enduring challenges of equity and human solidarity.

| | 在这一背景下,欧仁-布勒(Eugène Buret)等社会思想家的著作成为工业时代的凄美见证,既表达了对异化的现代性的批判,也表达了对改革的希望,改革将使所有公民融入一个更加公平的政治和社会结构中。这些历史反思为我们提供了一个视角,让我们了解社会变革的复杂性以及公平和人类团结所面临的持久挑战。 |

|

| |

|

| = The new spaces = | | = 新空间 = |

|

| |

|

| == Industrial basins and towns == | | == 工业盆地和城镇 == |

|

| |

|

| [[Fichier:Évolution de la population urbaine de l'europe 1000 - 1980.png|vignette|400px]] | | [[Fichier:Évolution de la population urbaine de l'europe 1000 - 1980.png|vignette|400px]] |

|

| |

|

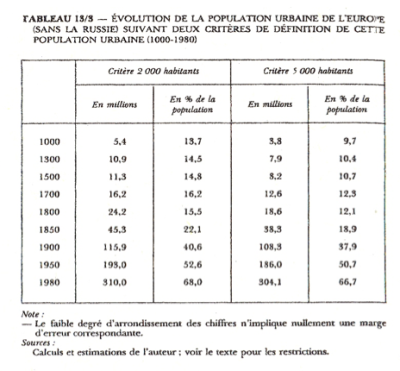

| This table gives an historical overview of the growth of the urban population in Europe, excluding Russia, through the ages, highlighting two population thresholds for defining a city: those with more than 2,000 inhabitants and those with more than 5,000 inhabitants. At the start of the second millennium, around the year 1000, Europe already had a significant proportion of its population living in urban areas. Towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants were home to 5.4 million people, making up 13.7% of the total population. If we raise the threshold to 5,000 inhabitants, we find 5.8 million people, representing 9.7% of the population. As we move towards 1500, we see a slight proportional increase in the urban population. In towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, it rose to 10.9 million, or 14.5% of the population. In towns with more than 5,000 residents, the number rose to 7.9 million, equivalent to 10.4% of the total population. The impact of the Industrial Revolution became clearly visible in 1800, with a significant jump in the number of city dwellers. There were 26.2 million people living in towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, who now accounted for 16.2% of the total population. For towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants, the number rises to 18.6 million, representing 12.5% of the population. Urbanisation accelerated further in the mid-nineteenth century, and by 1850 there were 45.3 million people living in towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, corresponding to 22.1% of the total population. Towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants were home to 38.3 million people, or 18.9% of the population. The twentieth century marked a turning point with massive urbanisation. By 1950, the population of towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants had risen to 193.0 million, representing a majority of 53.6% of the total population. Cities with more than 5,000 inhabitants were not to be outdone, with a population of 186.0 million, or 50.7% of all Europeans. Finally, in 1980, the urban phenomenon reached new heights, with 310.0 million Europeans living in towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants, representing 68.0% of the population. The figure for towns with more than 5,000 inhabitants was 301.1 million, equivalent to 66.7% of the population. The table thus reveals a spectacular transition from a predominantly rural to a predominantly urban Europe, a process that accelerated with industrialisation and continued throughout the 20th century.

| | 本表从历史角度概述了除俄罗斯以外的欧洲历代城市人口的增长情况,并突出强调了定义城市的两个人口门槛:居民超过 2000 人的城市和居民超过 5000 人的城市。在第二个千年之初,即 1000 年左右,欧洲已经有相当一部分人口居住在城市地区。居民超过 2000 人的城镇有 540 万人,占总人口的 13.7%。如果我们将门槛提高到 5000 人,就会发现有 580 万人,占总人口的 9.7%。随着人口数量向 1500 人迈进,我们发现城市人口的比例略有上升。在居民人数超过 2000 人的城镇,人口增至 1 090 万,占总人口的 14.5%。在居民超过 5000 人的城镇,这一数字上升到 790 万,相当于总人口的 10.4%。1800 年,工业革命的影响开始显现,城市居民人数大幅增加。当时有 2,620 万人居住在人口超过 2,000 人的城镇,占总人口的 16.2%。居民人数超过 5000 人的城镇居民人数增至 1 860 万人,占总人口的 12.5%。十九世纪中期,城市化进程进一步加快,到 1850 年,有 4530 万人居住在居民人数超过 2000 人的城镇,占总人口的 22.1%。居民超过 5000 人的城镇有 3830 万人,占总人口的 18.9%。二十世纪是大规模城市化的转折点。到 1950 年,居民超过 2000 人的城镇人口增至 1.93 亿,占总人口的 53.6%。居民超过 5000 人的城市也不甘示弱,人口达到 1.86 亿,占欧洲总人口的 50.7%。最后,在 1980 年,城市现象达到了新的高度,有 3.10 亿欧洲人居住在人口超过 2000 人的城镇,占总人口的 68.0%。居民超过 5000 人的城镇人口为 3.011 亿,占总人口的 66.7%。因此,该表揭示了欧洲从以农村为主向以城市为主的惊人转变,这一过程随着工业化的发展而加速,并持续了整个 20 世纪。 |

|

| |

|

| According to the economic historian Paul Bairoch, the society of the Ancien Régime was characterised by a natural limit of the urban population to around 15% of the total population. This idea stems from the observation that, until 1800, the vast majority of the population - between 70% and 75%, and even 80% during the winter months when agricultural activity slowed down - had to work in agriculture to produce enough food. Food production thus limited the size of urban populations, as agricultural surpluses had to feed city dwellers, who were often regarded as "parasites" because they did not contribute directly to agricultural production. The population not involved in agriculture, around 25-30%, was spread across other sectors of activity. But not all were urban dwellers; some lived and worked in rural areas, such as parish priests and other professionals. This meant that the proportion of the population that could live in the city without overburdening the productive capacity of agriculture was a maximum of 15%. This figure was not due to any formal legislation but represented an economic and social constraint dictated by the level of agricultural and technological development at the time. With the advent of the industrial revolution and advances in agriculture, the capacity of societies to feed larger urban populations increased, allowing this hypothetical limit to be exceeded and paving the way for increasing urbanisation.

| | 经济史学家保罗-贝罗赫(Paul Bairoch)认为,旧制度社会的特点是城市人口自然限制在总人口的 15%左右。这一观点源于这样一种观察,即在 1800 年之前,绝大多数人口--70% 至 75%,在农业活动放缓的冬季甚至达到 80%--必须务农才能生产足够的粮食。因此,粮食生产限制了城市人口的规模,因为农业盈余必须养活城市居民,而城市居民往往被视为 "寄生虫",因为他们对农业生产没有直接贡献。非农业人口约占 25-30%,分布在其他活动部门。但并非所有人都是城市居民;有些人在农村地区生活和工作,如教区牧师和其他专业人员。这就意味着,在不对农业生产能力造成过重负担的情况下,能够居住在城市的人口比例最多为 15%。这个数字并不是由于任何正式的法律规定,而是当时的农业和技术发展水平所决定的经济和社会限制。随着工业革命的到来和农业的进步,社会养活更多城市人口的能力不断提高,从而使这一假设的限制被突破,并为城市化的不断发展铺平了道路。 |

|

| |

|

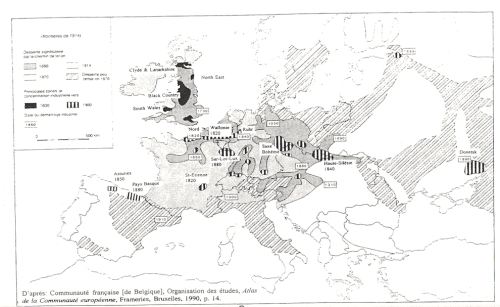

| The demographic and social landscape of Europe has undergone considerable change since the mid-19th century. Around 1850, the beginnings of industrialisation began to alter the balance between rural and urban populations. Technological advances in agriculture began to reduce the amount of labour needed to produce food, and expanding factories in the cities began to attract workers from the countryside. However, even with these changes, peasants and rural life remained predominant at the end of the 19th century. The majority of Europe's population still lived in farming communities, and it was only gradually that towns grew and societies became more urbanised. It was not until the mid-twentieth century, particularly in the 1950s, that we saw a major change, with the rate of urbanisation in Europe crossing the 50% threshold. This marked a turning point, indicating that for the first time in history, a majority of the population was living in cities rather than in rural areas. Today, with an urbanisation rate in excess of 70%, cities have become the dominant living environment in Europe. England, with cities such as Manchester and Birmingham, was the starting point for this change, followed by other industrial regions such as the Ruhr in Germany and Northern France, both of which were rich in resources and industries that attracted large workforces. These regions were the nerve centres of industrial activity and served as models for urban expansion across the continent.[[Fichier:Bassins et villes industrielles révolutoin industrielle.png|vignette|centre|500px]]

| | 自 19 世纪中期以来,欧洲的人口和社会面貌发生了巨大变化。1850 年前后,工业化的开端开始改变农村和城市人口之间的平衡。农业技术的进步开始减少生产粮食所需的劳动力,城市中不断扩大的工厂开始吸引来自农村的工人。然而,即使发生了这些变化,农民和农村生活在 19 世纪末仍占主导地位。欧洲的大多数人口仍然生活在农业社区,只是到了后来,城镇才逐渐发展起来,社会也变得更加城市化。直到二十世纪中叶,特别是二十世纪五十年代,我们才看到一个重大变化,欧洲的城市化率超过了 50%。这标志着一个转折点,表明历史上第一次有大多数人口居住在城市而不是农村地区。如今,城市化率已超过 70%,城市已成为欧洲最主要的生活环境。拥有曼彻斯特和伯明翰等城市的英格兰是这一变化的起点,紧随其后的是德国鲁尔区和法国北部等其他工业地区,这两个地区都拥有丰富的资源和吸引大量劳动力的工业。这些地区是工业活动的神经中枢,是整个欧洲大陆城市扩张的典范。[[Fichier:Bassins et villes industrielles révolutoin industrielle.png|vignette|centre|500px]] |

|

| |

|

| This map is a graphic representation of Europe in the pre-industrial era, highlighting the areas that were major industrial centres before the First World War. It highlights the intensity and specialisation of industrial activities through different symbols and patterns that identify the predominant types of industry in each region. Dark areas marked by symbols of blast furnaces and coal mines indicate industrial basins focused on metallurgy and mining. Places like the Ruhr, Northern France, Silesia, the Black Country region of Belgium and South Wales stand out as key industrial centres, showing the importance of coal and steel in the European economy at the time. Areas with stripes indicate regions where the textile industry and mechanical engineering were strongly represented. This geographical distribution shows that industrialisation was not uniform but rather concentrated in certain places, depending on available resources and capital investment. Distinct features denote regions specialising in iron and steel, notably Lorraine and parts of Italy and Spain, suggesting that the steel industry was also widespread, though less dominant than the coal industry. Maritime symbols, such as ships, are positioned in areas such as the North East of England, suggesting the importance of shipbuilding, which was consistent with the expansion of European colonial empires and international trade. This map provides a striking illustration of how the Industrial Revolution changed the economic and social landscape of Europe. The industrial regions identified were probably hotspots for internal migration, attracting workers from the countryside to the growing cities. This had a profound effect on demographic structure, leading to rapid urbanisation, the development of the working classes and the emergence of new social challenges such as pollution and substandard housing. The map highlights the unevenness of industrial development across the continent, reflecting the regional disparities that have emerged in terms of economic opportunities, living conditions and population growth. These industrial regions exerted a decisive influence on the economic and social trajectories of their respective countries, an influence that lasted well beyond the classical industrial era.

| | 这幅地图以图形的形式展示了前工业时代的欧洲,突出了第一次世界大战前的主要工业中心地区。它通过不同的符号和图案来识别每个地区的主要工业类型,从而突出了工业活动的强度和专业化程度。用高炉和煤矿符号标出的深色区域表示以冶金和采矿为主的工业盆地。鲁尔、法国北部、西里西亚、比利时黑土地区和南威尔士等地都是重要的工业中心,显示了煤炭和钢铁在当时欧洲经济中的重要性。带条纹的区域则表示纺织业和机械工程发达的地区。这种地理分布表明,工业化并不是千篇一律的,而是集中在某些地方,这取决于可用资源和资本投资。有明显特征的区域表示专门从事钢铁工业的地区,特别是洛林以及意大利和西班牙的部分地区,这表明钢铁工业也很普遍,尽管不如煤炭工业占主导地位。船只等海事标志位于英格兰东北部等地区,表明造船业的重要性,这与欧洲殖民帝国的扩张和国际贸易是一致的。这幅地图形象地说明了工业革命如何改变了欧洲的经济和社会面貌。所确定的工业地区可能是国内移民的热点地区,吸引了来自农村的工人前往不断发展的城市。这对人口结构产生了深远的影响,导致了快速的城市化、工人阶级的发展以及新的社会挑战(如污染和不合标准的住房)的出现。该地图凸显了整个非洲大陆工业发展的不平衡性,反映了在经济机会、生活条件和人口增长方面出现的地区差异。这些工业地区对各自国家的经济和社会发展轨迹产生了决定性的影响,这种影响远远超过了古典工业时代。 |

|

| |

|

| The historical map of pre-industrial Europe depicts two main types of industrial region that were crucial to the continent's economic and social transformation: the 'black countries' and the textile towns. The "black countries" are represented by areas darkened with icons of blast furnaces and mines. These regions were the heart of heavy industry, centred mainly on coal mining and steel production. Coal was the basis of the industrial economy, powering the machines and factories that underpinned the Industrial Revolution. Regions such as the Ruhr in Germany, Northern France, Silesia and the Black Country in Belgium were notable industrial centres, characterised by a dense concentration of coal- and steel-related activities. In contrast, the textile towns, indicated by striped areas, specialised in the production of textiles, a sector that was also vital during the Industrial Revolution. These towns took advantage of mechanisation to mass-produce fabrics, which elevated them to the status of major industrial centres. The textile revolution began in England and quickly spread to other parts of Europe, giving rise to numerous industrial towns centred on spinning and weaving. The distinction between these two types of industrial region is crucial. Whereas the black countries were often characterised by pollution, difficult working conditions and a significant environmental impact, textile towns, while also having their own social and health challenges, were generally less polluting and could be more dispersed in character, as textile mills required less concentration of heavy resources than blast furnaces and mines. The map therefore highlights not only the geographical distribution of industrialisation, but also the diversity of industries that made up the economic fabric of Europe at that time. Each of these regions had distinct social effects, influencing the lives of workers, the structure of social classes, urbanisation and the evolution of urban and rural societies in the context of the Industrial Revolution.

| | 前工业化欧洲的历史地图描绘了对欧洲大陆经济和社会转型至关重要的两大类工业地区:"黑人国家 "和纺织城。黑色国家 "以高炉和矿山图标的深色区域为代表。这些地区是重工业的中心,主要以煤矿和钢铁生产为中心。煤炭是工业经济的基础,为支撑工业革命的机器和工厂提供动力。德国鲁尔区、法国北部、西里西亚和比利时黑土区等地区都是著名的工业中心,其特点是煤炭和钢铁相关活动密集。相比之下,以条纹区域为标志的纺织城则专门从事纺织品生产,这一行业在工业革命期间也至关重要。这些城镇利用机械化优势大规模生产纺织品,从而提升了它们作为主要工业中心的地位。纺织革命始于英国,并迅速蔓延到欧洲其他地区,催生了众多以纺纱和织布为中心的工业城镇。这两类工业地区之间的区别至关重要。黑人国家通常以污染、艰苦的工作条件和对环境的严重影响为特征,而纺织城镇虽然也有其自身的社会和健康挑战,但通常污染较少,而且由于纺织厂与高炉和矿山相比对重型资源的集中度要求较低,因此可以更加分散。因此,这幅地图不仅突出了工业化的地理分布,也突出了构成当时欧洲经济结构的工业的多样性。在工业革命的背景下,每个地区都产生了独特的社会效应,影响了工人的生活、社会阶层的结构、城市化以及城乡社会的演变。 |

|

| |

|

| Black Country" is an evocative term used to describe the regions that became the scene of coal mining and metal production during the Industrial Revolution. The term refers to the omnipresent smoke and soot in these areas, the result of the intense activity of blast furnaces and foundries that transformed peaceful villages into industrial towns in a very short space of time. The atmosphere was so polluted that the sky and buildings were literally blackened, hence the name "black countries". This phenomenon of rapid industrialisation turned the static world of the time on its head, marking the start of an era in which economic growth became the norm and stagnation synonymous with crisis. Coalmining in particular catalysed this transformation by requiring a huge workforce. The coal mines and iron and steel industries became the driving force behind a dazzling demographic expansion, as in the case of Seraing, where the arrival of the industrialist Cockerill saw the population rise from 2,000 to 44,000 in the space of a century. Workers, often recruited from the rural population, were employed en masse in the coal mines, which required considerable physical strength, particularly for pick-axe work before automation in the 1920s. This demand for labour contributed to a rural exodus towards these centres of industrial activity. Ironworks required large open spaces because of the weight and size of the materials handled, so they could not be established in already dense towns. Industrialisation therefore moved to the countryside, where space was available and coal was within reach. This led to the creation of vast industrial basins, radically changing the landscape as well as the social and economic structure of the regions concerned. These industrial transformations also brought profound changes to society. Daily life was radically altered, with the birth of the working class and the deterioration of living conditions due to pollution and rapid urbanisation. The "black countries" became symbols of progress, but also witnesses to the social and environmental costs of the industrial revolution.

| | 黑土地 "是一个令人回味的术语,用来描述工业革命期间煤炭开采和金属生产的地区。这个词指的是这些地区无处不在的浓烟和煤灰,这是高炉和铸造厂剧烈活动的结果,它们在很短的时间内将宁静的村庄变成了工业城镇。大气污染严重,天空和建筑物都被熏黑,因此被称为 "黑色国家"。这种快速工业化的现象颠覆了当时的静态世界,标志着一个经济增长成为常态、停滞成为危机代名词的时代的开始。煤矿开采业需要大量劳动力,从而推动了这一转变。煤矿和钢铁工业成为令人眼花缭乱的人口扩张背后的驱动力,例如在塞拉英,工业家科克里尔的到来使人口在一个世纪内从 2000 人增加到 44000 人。煤矿需要大量体力,尤其是在 20 世纪 20 年代自动化之前的镐头工作。对劳动力的这种需求导致农村人口大量涌向这些工业活动中心。由于所处理的材料重量大、体积大,炼铁厂需要很大的空地,因此无法建在已经很密集的城镇中。因此,工业化转移到了农村,因为那里有可用的空间,煤炭也近在咫尺。这就形成了巨大的工业盆地,从根本上改变了相关地区的景观以及社会和经济结构。这些工业变革也给社会带来了深刻变化。随着工人阶级的诞生以及污染和快速城市化导致的生活条件恶化,日常生活发生了翻天覆地的变化。黑色国家 "成为进步的象征,同时也见证了工业革命的社会和环境代价。 |

|

| |

|

| Victor Hugo described these landscapes: "When you pass the place called Petite-Flémalle, the sight becomes inexpressible and truly magnificent. The whole valley seems to be pitted with erupting craters. Some of them spew out swirls of scarlet steam spangled with sparks behind the undergrowth; others gloomily outline the black silhouette of villages against a red background; elsewhere flames appear through the cracks in a group of buildings. You would think that an enemy army had just crossed the country, and that twenty villages had been sacked, offering you at the same time in this dark night all the aspects and all the phases of the fire, some engulfed in flames, some smoking, others blazing. This spectacle of war is given by peace; this appalling copy of devastation is made by industry. You are simply looking at Mr Cockerill's blast furnaces.

| | 维克多-雨果曾这样描述这些风景:"当你经过一个叫小弗莱马勒的地方时,眼前的景象变得难以言喻,真正壮丽无比。整个山谷仿佛都是喷发的火山口。有的火山口喷出猩红色的蒸汽漩涡,在灌木丛后闪烁着火花;有的火山口在红色的背景下阴沉地勾勒出村庄的黑色轮廓;还有的火山口从建筑群的缝隙中喷出火焰。你会以为一支敌军刚刚越过这个国家,二十个村庄被洗劫一空,在这个漆黑的夜晚,你可以同时看到大火的各个方面和各个阶段,有的被火焰吞没,有的在冒烟,有的在燃烧。这战争的景象是和平造成的;这骇人听闻的破坏是工业造成的。你们现在看到的只是科克里尔先生的高炉。 |

|

| |

|

| This quotation from Victor Hugo, taken from his "Journey along the Rhine" written in 1834, is a powerful testimony to the visual and emotional impact of industrialisation in Europe. Hugo, known for his literary work but also for his interest in the social issues of his time, describes here with dark and powerful lyricism the Meuse valley in Belgium, near Petite-Flémalle, marked by John Cockerill's industrial installations. Hugo uses images of destruction and war to describe the industrial scene before him. The blast furnaces light up the night, resembling erupting craters, burning villages, or even a land ravaged by an enemy army. There is a striking contrast between peace and war; the scene he describes is not the result of armed conflict but of peaceful, or at least non-military, industrialisation. The "erupting craters" evoke the intensity and violence of industrial activity, which marks the landscape as indelibly as war itself. This dramatic description underlines both the fascination and the repulsion that industrialisation can arouse. On the one hand, there is the magnificence and power of human transformation; on the other, the destruction of a way of life and an environment. The references to fires and the black silhouettes of villages project the image of a land in the grip of almost apocalyptic forces, reflecting the ambivalence of industrial progress. To put this quotation into context, we need to remember that Europe in the 1830s was in the midst of an industrial revolution. Technological innovations, the intensive use of coal and the development of metallurgy were radically transforming the economy, society and the environment. Cockerill was a leading industrial entrepreneur of this era, having developed one of the largest industrial complexes in Europe in Seraing, Belgium. The rise of this industry was synonymous with economic prosperity, but also with social upheaval and considerable environmental impact, including pollution and landscape degradation. With this quote, Victor Hugo invites us to reflect on the dual face of industrialisation, which is both a source of progress and devastation. In so doing, he reveals the ambiguity of an era when human genius, capable of transforming the world, must also reckon with the sometimes dark consequences of these transformations.

| | 这段引文出自维克多-雨果 1834 年创作的《莱茵河畔的旅行》,有力地证明了欧洲工业化所带来的视觉和情感冲击。雨果以文学创作著称,同时也关注当时的社会问题,他在这里以黑暗而有力的抒情笔触描绘了比利时的默兹河谷,在小弗莱马勒附近,约翰-考克里尔的工业设施是这里的标志。雨果用破坏和战争的形象来描述他眼前的工业场景。高炉照亮了黑夜,就像喷发的火山口、燃烧的村庄,甚至是被敌军蹂躏的土地。和平与战争形成了鲜明的对比;他所描述的场景不是武装冲突的结果,而是和平或至少是非军事工业化的结果。喷发的弹坑 "让人联想到工业活动的强度和暴力,而工业活动就像战争本身一样在这片土地上留下了不可磨灭的印记。这种戏剧性的描述强调了工业化既能引起人们的兴趣,也能引起人们的反感。一方面是人类变革的伟大和力量,另一方面是对生活方式和环境的破坏。作品中提到的大火和村庄的黑色轮廓,投射出这片土地被近乎世界末日的力量所控制的形象,反映出工业进步的矛盾性。要理解这段引文的背景,我们需要记住,19 世纪 30 年代的欧洲正处于工业革命之中。技术革新、煤炭的大量使用以及冶金业的发展从根本上改变了经济、社会和环境。科克里尔是这一时代领先的工业企业家,他在比利时塞拉英开发了欧洲最大的工业综合体之一。这一工业的兴起是经济繁荣的代名词,但同时也带来了社会动荡和相当大的环境影响,包括污染和景观退化。维克多-雨果通过这句话让我们反思工业化的两面性,它既是进步的源泉,也是破坏的根源。他通过这句话揭示了一个时代的模糊性,即人类的天才能够改变世界,但也必须面对这些改变有时带来的黑暗后果。 |

|

| |

|

| The textile towns of the Industrial Revolution represent a crucial aspect of the economic and social transformation that began in the 18th century. In these urban centres, the textile industry played a driving role, facilitated by the extreme division of labour into distinct processes such as weaving, spinning and dyeing. Unlike the heavy coal and steel industries, which were often located in rural or peri-urban areas for logistical and space reasons, textile factories were able to take advantage of the verticality of existing or purpose-built urban buildings to maximise limited floor space. These factories became a natural part of the urban landscape, helping to redefine the towns and cities of northern France, Belgium and other regions, which saw their population density increase dramatically. The transition from craft and proto-industry to large-scale industrial production led to the bankruptcy of many craftsmen, who then turned to factory work. Textile industrialisation transformed towns into veritable industrial metropolises, leading to rapid and often disorganised urbanisation, marked by unbridled construction in every available space. The massive increase in textile production was not accompanied by an equivalent increase in the number of workers, thanks to the productivity gains achieved through industrialisation. The textile towns of the time were therefore characterised by an extreme concentration of the workforce in the factories, which became the centre of social and economic life, eclipsing traditional institutions such as the town hall or public squares. Public space was dominated by the factory, which defined not only the urban landscape, but also the rhythm and structure of community life. This transformation also influenced the social composition of towns, attracting merchants and entrepreneurs who had benefited from the economic growth of the 19th century. These new elites often supported and invested in the development of industrial and residential infrastructures, thereby contributing to urban expansion. In short, textile towns embody a fundamental chapter in industrial history, illustrating the close link between technological progress, social change and the reconfiguration of the urban environment.

| | 工业革命时期的纺织城代表了始于 18 世纪的经济和社会变革的一个重要方面。在这些城市中心,纺织业发挥了推动作用,而纺织、纺纱和印染等不同工序的极端分工则促进了纺织业的发展。与重型煤炭和钢铁工业不同的是,由于物流和空间的原因,它们通常位于农村或城市周边地区,而纺织厂则能够利用现有或专门建造的城市建筑的垂直性,最大限度地利用有限的建筑面积。这些工厂成为城市景观的自然组成部分,帮助重新定义了法国北部、比利时和其他地区的城镇,这些地区的人口密度急剧增加。从手工业和原始工业向大规模工业生产的过渡导致许多手工业者破产,转而在工厂工作。纺织品工业化将城镇变成了名副其实的工业大都市,导致了快速且往往是无序的城市化,其特点是在每一个可用的空间都进行无节制的建设。由于工业化提高了生产率,纺织品产量的大幅增长并没有带来工人数量的相应增加。因此,当时纺织城的特点是劳动力极度集中在工厂,工厂成为社会和经济生活的中心,使市政厅或公共广场等传统机构黯然失色。工厂主导了公共空间,不仅决定了城市景观,也决定了社区生活的节奏和结构。这种转变也影响了城镇的社会构成,吸引了从 19 世纪经济增长中获益的商人和企业家。这些新的精英往往支持并投资于工业和住宅基础设施的发展,从而推动了城市的扩张。总之,纺织城体现了工业史的基本篇章,说明了技术进步、社会变革和城市环境重构之间的密切联系。 |

|

| |

|

| == Two types of demographic development == | | == 两种人口发展类型 == |

|

| |

|

| [[File:Vue de Verviers. Joseph Fussell (1818-1912).jpg|thumb|right|upright=1.1|View of Verviers (mid-19th c.)Watercolour by J. Fussell.]] | | [[File:Vue de Verviers. Joseph Fussell (1818-1912).jpg|thumb|right|upright=1.1|韦尔维耶风景(19 世纪中叶)水彩画,J. Fussell 创作。]] |

|

| |

|

| The Industrial Revolution led to major migration from rural to urban areas, irreversibly transforming European societies. In the context of textile towns, this rural exodus was particularly pronounced. Craftsmen and proto-industrial workers, traditionally dispersed in the countryside where they worked at home or in small workshops, were forced to congregate in the industrial cities. This was due to the need to be close to the factories, as long journeys between home and work became impractical with the increasingly regulated work structure of the factory. The concentration of workers in cities had several consequences. On the one hand, the proximity of workers to production sites enabled more efficient management and rationalisation of the work process, leading to an explosion in productivity without necessarily increasing the number of workers employed. Indeed, innovations in production techniques, such as the use of steam engines and the automation of weaving and spinning processes, have considerably increased yields while maintaining or reducing the workforce required. In cities, the concentration of the population also led to rapid densification and urbanisation, as shown by the example of Verviers. The population of this Belgian textile town almost tripled over the course of the nineteenth century, rising from 35,000 at the start to 100,000 by the end of the century. This rapid expansion of the urban population often led to hasty urbanisation and difficult living conditions, as the existing infrastructure was rarely adequate to cope with such an influx. The concentration of the workforce also changed the social structure of cities, creating new classes of industrial workers and altering existing socio-economic dynamics. It also had an impact on the urban fabric, with the construction of housing for workers, the expansion of urban services and facilities, and the development of new forms of community life centred around the factory rather than the traditional structures of the city. Ultimately, the phenomenon of textile towns during the Industrial Revolution illustrates the transformative power of industrialisation on settlement patterns, the economy and society as a whole.

| | 工业革命导致大量人口从农村迁往城市,不可逆转地改变了欧洲社会。就纺织城而言,农村人口的外流尤为明显。传统上分散在农村家庭或小作坊工作的手工业者和原产业工人被迫聚集到工业城市。这是由于需要靠近工厂,因为工厂的工作结构越来越规范,从家到工作地点之间的长途跋涉变得不切实际。工人集中在城市产生了几种后果。一方面,由于工人靠近生产基地,因此可以更有效地管理和合理安排工作流程,从而在不增加工人数量的情况下实现生产率的激增。事实上,生产技术的创新,如蒸汽机的使用以及纺织和纺纱工序的自动化,在保持或减少所需劳动力的同时,大大提高了产量。在城市,人口的集中也导致了快速的人口密集化和城市化,韦尔维耶(Verviers)就是一个例子。这座比利时纺织城的人口在十九世纪几乎增加了两倍,从最初的 35,000 人增加到世纪末的 100,000 人。城市人口的快速扩张往往导致城市化进程仓促,生活条件艰苦,因为现有的基础设施很少足以应对如此大量的人口涌入。劳动力的集中也改变了城市的社会结构,产生了新的产业工人阶层,并改变了现有的社会经济动态。它还对城市结构产生了影响,为工人建造了住房,扩大了城市服务和设施,发展了以工厂而非传统城市结构为中心的新型社区生活。最终,工业革命时期的纺织城现象说明了工业化对居住模式、经济和整个社会的变革力量。 |

|

| |

|

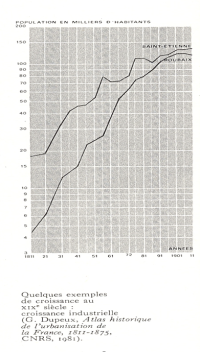

| The steel regions, often referred to as 'black countries' because of the soot and pollution from factories and mines, illustrate another facet of the impact of industrialisation on demography and urban development. The black countries were centred on the coal and iron industries, which were essential catalysts for the industrial revolution. The demographic explosion in these regions was due less to an increase in the number of workers per mine or factory than to the emergence of new labour-intensive industries. Although mechanisation was progressing, it was not yet replacing the need for workers in coal mines and ironworks. For example, although the steam engine made it possible to ventilate the galleries and increase the productivity of the mines, extracting coal was still a very laborious job requiring large numbers of workers. The demographic growth in towns such as Liège, where the population rose from 50,000 to 400,000, bears witness to this industrial expansion. The coalfields and steelworks became centres of attraction for workers looking for work, leading to rapid growth in the surrounding towns. These workers were often migrants from the countryside or other less industrialised regions, attracted by the job opportunities created by these new industries. These industrial towns grew at an impressive rate, often without the planning or infrastructure needed to adequately accommodate their new population. The result was precarious living conditions, with overcrowded and unhealthy housing, public health problems and growing social tensions. These challenges would eventually lead to urban and social reforms in the following centuries, but during the Industrial Revolution, these regions were marked by rapid and often chaotic transformation.[[Fichier:Développement démographique saint Etienne vs Roubaix.png|200px|vignette]]

| | 由于工厂和矿山产生的烟尘和污染而经常被称为 "黑色国家 "的钢铁地区,从另一个侧面说明了工业化对人口和城市发展的影响。黑色国家以煤炭和钢铁工业为中心,而煤炭和钢铁工业是工业革命的重要催化剂。这些地区人口爆炸的原因与其说是每个矿山或工厂工人数量的增加,不如说是新的劳动密集型产业的出现。虽然机械化在不断进步,但尚未取代煤矿和炼铁厂对工人的需求。例如,虽然蒸汽机使矿井通风成为可能,提高了矿井的生产率,但采煤仍然是一项非常费力的工作,需要大量工人。列日等城镇的人口从 5 万增加到 40 万,见证了这种工业扩张。煤田和钢铁厂成为吸引工人寻找工作的中心,导致周边城镇迅速发展。这些工人通常是来自农村或其他工业化程度较低地区的移民,被这些新兴工业创造的就业机会所吸引。这些工业城镇以惊人的速度发展,但往往缺乏必要的规划或基础设施来充分容纳新增人口。结果是生活条件岌岌可危,住房拥挤、不卫生、公共卫生问题和社会矛盾日益加剧。这些挑战最终导致了随后几个世纪的城市和社会改革,但在工业革命期间,这些地区却经历了快速且往往是混乱的转型。[[Fichier:Développement démographique saint Etienne vs Roubaix.png|200px|vignette]] |

|

| |

|

| This graph shows the significant demographic growth of Saint-Étienne and Roubaix, two emblematic cities of the French industrial epic, over the period from 1811 to 1911. Over the course of the century, these towns saw their populations grow considerably as a result of rampant industrialisation. In Roubaix, the growth was particularly striking. Known for its flourishing textile industry, the town grew from fewer than 10,000 inhabitants at the start of the century to around 150,000 at its end. The labour-intensive textile industry led to a massive migration of rural populations to Roubaix, radically transforming its social and urban landscape. Saint-Étienne followed a similar upward curve, although its numbers remained lower than those of Roubaix. As a strategic centre for metallurgy and arms manufacture, the town also created a huge demand for skilled and unskilled workers, which contributed to its demographic boom. Industrialisation was the catalyst for a major social change, reflected in the metamorphosis of these small communities into dense urban centres. This transformation has not been without its difficulties: rapid urbanisation has led to overcrowding, poor housing and health challenges. The need to develop appropriate infrastructure to meet the growing needs of the population has become obvious. While the growth of these populations has stimulated the local economy, it has also raised questions about quality of life and social disparities. The evolution of Saint-Étienne and Roubaix is representative of the impact of industrialisation on the transformation of small rural communities into large modern urban centres, with their share of benefits and challenges.

| | 该图显示了圣埃蒂安和鲁贝这两个法国工业史诗中的标志性城市在 1811 年至 1911 年期间的人口增长情况。在这一世纪中,由于工业化的蓬勃发展,这两个城市的人口大幅增长。鲁贝的人口增长尤为显著。该镇以蓬勃发展的纺织业而闻名,居民人数从世纪初的不到 10,000 人增长到世纪末的约 150,000 人。劳动密集型纺织业导致大量农村人口向鲁贝迁移,从根本上改变了鲁贝的社会和城市面貌。圣埃蒂安的人口数量虽然低于鲁贝,但也呈现出类似的上升趋势。作为冶金和武器制造的战略中心,圣艾蒂安对技术工人和非技术工人的需求巨大,从而推动了人口的增长。工业化推动了重大的社会变革,这些小社区蜕变为密集的城市中心就反映了这一点。这种转变并非没有困难:快速城市化导致过度拥挤、住房条件差和健康问题。显然,需要发展适当的基础设施来满足人口日益增长的需求。虽然这些人口的增长刺激了当地经济的发展,但也引发了生活质量和社会差距的问题。圣埃蒂安和鲁贝的演变代表了工业化对小型农村社区转变为大型现代化城市中心的影响,其中既有好处,也有挑战。 |

|

| |

|

| Industrialisation led to the rapid and disorganised growth of industrial towns and cities, resulting in a marked contrast with the large cities that were modernising at the same time. Towns such as Seraing in Belgium, which rapidly industrialised thanks to its steelworks and mines, saw a considerable increase in their population without the urban planning necessary to accompany such expansion. These industrial towns, while having a population density equivalent to that of large cities, often lacked the corresponding infrastructure and services. Instead, their rapid growth had the characteristics of a sprawling village, with rudimentary organisation and inadequate public services, particularly in terms of public hygiene and education. The lack of infrastructure and public services was all the more problematic given the rapid growth in population. In these towns, the need for primary schools, health services and basic infrastructure far exceeded the capacity of local administrations to meet it. The finances of industrial towns were often precarious: they took on huge debts to build schools and other necessary infrastructure, as shown by the example of Seraing, which only repaid its last school building loan in 1961. The low tax base of these towns, due to the low wages of their workers, limited their ability to invest in the necessary improvements. So while the big cities were beginning to enjoy the attributes of modernity - running water, electricity, universities and efficient administrations - the industrial towns were struggling to provide basic services for their inhabitants. This situation reflects the social and economic inequalities inherent in the industrial era, where prosperity and technical progress coexisted with precarious and inadequate living conditions for a large proportion of the working population.

| | 工业化导致工业城镇和城市迅速而无序地发展,与同时现代化的大城市形成了明显的对比。比利时的塞拉因(Seraing)等城镇因其钢铁厂和矿山而迅速实现工业化,人口大幅增加,但却没有伴随这种扩张而进行必要的城市规划。这些工业城镇的人口密度与大城市相当,但往往缺乏相应的基础设施和服务。相反,它们的快速发展具有无序扩张的村庄的特征,组织机构简陋,公共服务不足,尤其是在公共卫生和教育方面。由于人口的快速增长,基础设施和公共服务的匮乏就更成问题了。在这些城镇中,对小学、医疗服务和基本基础设施的需求远远超出了当地政府的能力。工业城镇的财政状况往往岌岌可危:它们为建造学校和其他必要的基础设施背负了巨额债务,塞拉因就是一个例子,它直到 1961 年才偿还了最后一笔建校贷款。由于工人工资低,这些城镇的税基也很低,这限制了它们投资进行必要改善的能力。因此,当大城市开始享受现代化的特质--自来水、电力、大学和高效的行政管理时,工业城镇却在努力为居民提供基本服务。这种情况反映了工业时代固有的社会和经济不平等,在工业时代,繁荣和技术进步与大部分劳动人口不稳定和不充分的生活条件并存。 |

|

| |

|

| == Housing conditions and hygiene == | | == 住房条件和卫生 == |

| The industrial revolution revolutionised urban landscapes, and textile towns are a striking example of this. These areas, already densely populated before industrialisation, had to adapt quickly to a new wave of demographic influx. This was mainly due to the concentration of the textile industry in specific urban areas, which attracted workers from all over. To meet the resulting housing shortage, towns were forced to densify existing housing. Extra storeys were often added to buildings, exploiting every available square metre, even over narrow alleyways. This impromptu modification of the urban infrastructure created precarious living conditions, as these additional constructions were not always built with the necessary safety and comfort in mind. The infrastructure of these cities, such as sanitation, water supply and waste management systems, was often insufficient to cope with the rapid increase in population. Health and education services were struggling to keep up with growing demand. This rapid, sometimes anarchic, urbanisation led to difficult living conditions, with long-term consequences for the health and well-being of residents. These challenges reflect the tension between economic development and social needs in the rapidly changing cities of the Industrial Revolution. The authorities of the time were often overwhelmed by the scale of the changes and struggled to fund and implement the public services needed to keep pace with this explosive population growth.

| | 工业革命彻底改变了城市面貌,纺织城就是一个鲜明的例子。这些地区在工业化之前就已经人口稠密,必须迅速适应新一轮的人口流入。这主要是由于纺织工业集中在特定的城市地区,吸引了来自各地的工人。为了解决由此造成的住房短缺问题,城镇不得不对现有住房进行密集化改造。人们往往在建筑物上加盖楼层,利用一切可用的平方米,甚至是狭窄的小巷。这种对城市基础设施的临时改造造成了不稳定的居住条件,因为这些加盖的建筑并不总是考虑到必要的安全性和舒适性。这些城市的基础设施,如卫生、供水和废物管理系统,往往不足以应对人口的快速增长。卫生和教育服务也难以满足日益增长的需求。这种快速的、有时是无政府状态的城市化导致了艰难的生活条件,对居民的健康和福祉造成了长期影响。这些挑战反映了工业革命时期快速变化的城市中经济发展与社会需求之间的矛盾。当时的政府当局往往被规模巨大的变化压得喘不过气来,并竭力资助和实施所需的公共服务,以跟上人口爆炸式增长的步伐。 |

|

| |

|

| Dr. Kuborn was a doctor who worked in Seraing, Belgium, at the beginning of the 20th century. He witnessed at first hand the consequences of rapid industrialisation on the living conditions of workers and their families. Dr. Kuborn had a professional, and perhaps personal, interest in public health issues and urban hygiene. Doctors of the time were beginning to establish links between health and the environment, particularly the way in which substandard housing contributed to the spread of disease. They often played a key role in reforming living conditions by advocating improved urban planning, sanitation and housing standards. Dr. Kuborn shows that he was concerned about these issues and that he used his platform to draw attention to the unsanitary conditions in which the workers were forced to live.

| | 库伯恩博士是 20 世纪初在比利时塞拉英工作的一名医生。他亲眼目睹了快速工业化对工人及其家庭生活条件造成的影响。库伯恩医生对公共卫生问题和城市卫生有着专业的兴趣,或许也是个人兴趣。当时的医生开始将健康与环境联系起来,特别是不达标的住房会导致疾病的传播。他们往往通过倡导改善城市规划、卫生和住房标准,在改革生活条件方面发挥关键作用。库伯恩博士表明,他关注这些问题,并利用自己的平台提请人们注意工人们被迫生活在不卫生的环境中。 |

|

| |

|

| Dr. Kuborn depicts the deplorable state of workers' housing at the time. Referring to Seraing, he reports: "Dwellings were built as they were, most of them unsanitary, without a general plan in place. Low, sunken houses, without air or light; one room on the ground floor, no pavement, no cellar; an attic as an upper floor; ventilation through a hole, fitted with a pane of glass fixed into the roof; stagnation of household water; absence or inadequacy of latrines; overcrowding and promiscuity". He mentions poorly built houses, lacking fresh air, natural light and basic sanitary conditions such as adequate latrines. This image illustrates the lack of urban planning and disregard for the welfare of workers who, because of the need to house a growing working-class population near the factories, were forced to live in deplorable conditions.

| | 库博恩博士描述了当时工人住房的糟糕状况。在谈到塞拉英时,他写道 他说:"住宅都是按原样建造的,大多数都不卫生,没有总体规划。低矮的下沉式房屋,不通风也不采光;底层只有一个房间,没有人行道,没有地窖;阁楼作为上层;通过一个洞通风,屋顶上安装了一块玻璃;生活用水停滞;没有厕所或厕所不足;过度拥挤和杂乱无章"。他提到房屋建筑简陋,缺乏新鲜空气、自然光和基本的卫生条件,如足够的厕所。这幅图显示了城市规划的缺失和对工人福利的漠视,由于需要在工厂附近安置日益增多的工人阶级,工人们被迫在恶劣的条件下生活。 |

|

| |

|

| As Dr. Kuborn describes it: "It is in these insalubrious places, in these vile haunts, that epidemic diseases strike like a bird of prey swooping down on its victim. Cholera has shown us this, influenza reminds us of it, and perhaps typhus will give us a third example one of these days", he points out the disastrous consequences of these poor living conditions for the health of the inhabitants. Dr. Kuborn makes the link between unsanitary housing and the spread of epidemic diseases such as cholera, influenza and potentially typhus. The metaphor of the bird of prey swooping down on its victim is a powerful one, evoking the vulnerability of the workers who are like helpless prey in the face of the diseases proliferating in their unhealthy environment.

| | 正如库伯恩博士所描述的那样: "正是在这些不卫生的地方,在这些肮脏的地方,流行病就像猛禽一样扑向它的受害者。霍乱让我们看到了这一点,流感让我们想起了这一点,也许斑疹伤寒会在某一天给我们提供第三个例子",他指出了这些恶劣的生活条件对居民健康造成的灾难性后果。库伯恩博士将不卫生的住房与霍乱、流感和潜在的斑疹伤寒等流行病的传播联系起来。鸷鸟扑向受害者的比喻非常有力,让人联想到工人的脆弱性,他们在不卫生的环境中面对疾病泛滥就像无助的猎物。 |

|

| |

|

| These testimonies are representative of living conditions in European industrial towns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They reflect the grim reality of the Industrial Revolution, which, despite its technological and economic advances, often neglected the human and social aspects, leading to public health problems and marked social inequalities. These quotations call for reflection on the importance of urban planning, decent housing and access to adequate health services for all, issues that are still topical in many parts of the world.

| | 这些证词代表了 19 世纪末 20 世纪初欧洲工业城镇的生活状况。它们反映了工业革命的严峻现实,尽管工业革命取得了技术和经济上的进步,但往往忽视了人和社会方面的问题,导致公共卫生问题和明显的社会不平等。这些引文呼吁人们反思城市规划、体面住房和人人享有适当医疗服务的重要性,这些问题在世界许多地方仍然是热门话题。 |

|

| |

|

| The development of the so-called "Black Country" regions, frequently associated with industrial areas where coal mining and steelmaking were predominant, was often rapid and disorganised. This anarchic growth was the result of accelerated urbanisation, where the need to house a large and growing workforce took precedence over urban planning and infrastructure. In many cases, living conditions in these areas were extremely precarious. Workers and their families were often housed in shanty towns or hastily constructed dwellings with little regard for durability, hygiene or comfort. These dwellings, often built without solid foundations, were not only unhealthy, but also dangerous, liable to collapse or become breeding grounds for disease. The density of the buildings, the lack of ventilation and light, and the absence of basic infrastructure such as running water and sanitation systems exacerbate public health problems. The cost of improving these areas was prohibitive, especially given their size and the poor quality of the existing buildings. As Dr. Kuborn pointed out in his comments on Seraing, setting up water and sewerage systems required major investments that local authorities were often unable to finance. Indeed, with a small tax base due to the low wages of the workers, these communities had few resources for investment in infrastructure. As a result, these communities found themselves caught in a vicious circle: inadequate infrastructure led to a deterioration in public health and quality of life, which in turn discouraged the investment and urban planning needed to improve the situation. In the end, the only viable solution often seemed to be to demolish existing structures and rebuild, a costly and disruptive process that was not always possible or achieved.

| | 所谓的 "黑土地 "地区通常与以煤矿开采和炼钢为主的工业区有关,其发展往往迅速而无序。这种无序的发展是城市化加速的结果,在城市化进程中,容纳大量不断增长的劳动力的需求优先于城市规划和基础设施。在许多情况下,这些地区的生活条件极不稳定。工人及其家人往往住在棚户区或匆忙建造的住宅中,很少考虑到耐用性、卫生或舒适度。这些住房往往没有坚实的地基,不仅不卫生,而且很危险,容易倒塌或成为疾病的滋生地。建筑密度大、缺乏通风和采光,以及缺乏自来水和卫生系统等基本基础设施,都加剧了公共卫生问题。改善这些地区的成本过高,特别是考虑到这些地区的面积和现有建筑的质量较差。正如 Kuborn 博士在关于塞拉英的评论中所指出的,建立供水和排污系统需要大量投资,而地方当局往往无力承担。事实上,由于工人工资低,税基小,这些社区用于基础设施投资的资源很少。结果,这些社区发现自己陷入了恶性循环:基础设施不足导致公共卫生和生活质量下降,这反过来又阻碍了改善现状所需的投资和城市规划。最后,唯一可行的解决办法似乎往往是拆除现有建筑并进行重建,但这一过程成本高昂且具有破坏性,而且并非总能实现。 |

|

| |

|

| Louis Pasteur's discoveries in the mid-nineteenth century about microbes and the importance of hygiene were fundamental to public health. However, the application of these hygiene principles in industrialised urban areas was complicated by a number of factors. Firstly, anarchic urbanisation, with development carried out without proper planning, has led to the creation of unsanitary housing and a lack of essential infrastructure. Installing water and sewerage systems in already densely built-up towns was extremely difficult and costly. Unlike planned neighbourhoods, where an efficient network of pipes could serve many inhabitants in a small area, sprawling shantytowns required kilometres of piping to connect each scattered dwelling. Secondly, land subsidence due to abandoned underground mining posed considerable risks to the integrity of the new infrastructure. The pipes could easily be damaged or destroyed by these ground movements, wiping out the efforts and investment made to improve hygiene. Thirdly, air pollution exacerbated the health problems even further. Smoke from factories and furnaces literally covered the towns with a layer of soot and pollutants, which not only made the air unhealthy to breathe but also contributed to the deterioration of buildings and infrastructure. All these factors confirm the difficulty of establishing hygiene and public health standards in already established industrial urban environments, especially when they have been developed hastily and without a long-term vision. This underlines the importance of urban planning and forecasting in the management of cities, particularly in the context of rapid industrial development.

| | 路易-巴斯德在十九世纪中叶发现了微生物并认识到卫生的重要性,这对公共卫生至关重要。然而,这些卫生原则在工业化城市地区的应用因多种因素而变得复杂。首先,无政府主义的城市化,在没有适当规划的情况下进行的开发,导致了不卫生的住房和基本基础设施的缺乏。在已建成的密集城镇中安装供水和排污系统极其困难,而且成本高昂。与规划好的居民区不同,高效的管道网络可以为小范围内的众多居民提供服务,而无序扩张的棚户区则需要铺设数公里长的管道才能连接每一个分散的住宅。其次,废弃的地下采矿造成的地面沉降对新基础设施的完整性构成了巨大风险。这些地面运动很容易损坏或毁坏管道,使为改善卫生状况所做的努力和投资化为乌有。第三,空气污染进一步加剧了健康问题。工厂和熔炉冒出的浓烟使城镇笼罩在一层烟尘和污染物中,这不仅使空气呼吸不健康,而且还导致建筑物和基础设施老化。所有这些因素都证明,在已经建成的工业化城市环境中建立卫生和公共健康标准非常困难,尤其是在仓促开发和缺乏长远规划的情况下。这凸显了城市规划和预测在城市管理中的重要性,尤其是在工业快速发展的背景下。 |

|

| |

|

| Germany, as a latecomer to the industrial revolution, has had the advantage of observing and learning from the mistakes and challenges faced by its neighbours such as Belgium and France. This enabled it to adopt a more methodical and planned approach to industrialisation, particularly with regard to workers' housing and town planning. The German authorities implemented policies that encouraged the construction of better quality housing for workers, as well as wider and better organised streets. This contrasted with the often chaotic and unhealthy conditions in industrial cities elsewhere, where rapid and unregulated growth had led to overcrowded and poorly equipped neighbourhoods. A key aspect of the German approach was a commitment to more progressive social policies, which recognised the importance of worker welfare to overall economic productivity. German industrial companies often took the initiative to build housing for their employees, with facilities such as gardens, baths and laundries, which contributed to workers' health and comfort. In addition, social legislation in Germany, such as the laws on health insurance, accident insurance and pension insurance introduced under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s, helped to establish a safety net for workers and their families. These efforts to improve workers' housing and living conditions, combined with preventive social legislation, helped Germany avoid some of the worst effects of rapid industrialisation. It also laid the foundations for a more stable society and for Germany's role as a major industrial power in later years.

| | 作为工业革命的后来者,德国的优势在于可以观察和学习比利时和法国等邻国所犯的错误和面临的挑战。这使德国在工业化过程中,特别是在工人住房和城市规划方面,采取了更有条理、更有计划的方法。德国当局实施的政策鼓励为工人建造质量更好的住房,以及更宽阔、更有组织的街道。这与其他地方的工业城市往往混乱和不健康的状况形成了鲜明对比,在其他地方,快速和无序的发展导致居民区过度拥挤和设施简陋。德国做法的一个重要方面是致力于推行更进步的社会政策,承认工人福利对整体经济生产力的重要性。德国的工业企业通常会主动为员工建造住房,并配备花园、浴室和洗衣房等设施,这有助于工人的健康和舒适。此外,德国的社会立法,如奥托-冯-俾斯麦总理在 19 世纪 80 年代推出的医疗保险、意外保险和养老保险法,也有助于为工人及其家庭建立一个安全网。这些改善工人住房和生活条件的努力与预防性社会立法相结合,帮助德国避免了快速工业化带来的一些最坏影响。这也为德国日后成为一个更加稳定的社会和工业大国奠定了基础。 |

|

| |

|

| == Poor nutrition and low wages == | | == 营养不良和工资低 == |

|

| |

|

| [[Fichier:Une alimentation déficiente et des salaires bas.png|300px|vignette]] | | [[Fichier:Une alimentation déficiente et des salaires bas.png|300px|vignette]] |

|

| |

|

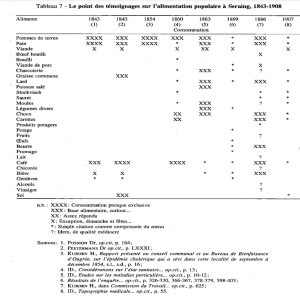

| This table provides a historical window on eating habits in Seraing, Belgium, from 1843 to 1908. Each column corresponds to a specific year or period, and the consumption of different foods is coded to indicate their prevalence in the local diet. The codes range from "XXXX" for almost exclusive consumption, to "X" for lesser consumption. An asterisk "*" indicates a simple mention of the food, while annotations such as "Accessory" or "Exception, party..." suggest occasional consumption or consumption linked to particular events. Question marks "?" are used when consumption is uncertain or undocumented, and the words "of mediocre quality" suggest lower quality products at certain times. An analysis of this table reveals several notable aspects of the diet of the period. Potatoes and bread emerge as fundamental elements, reflecting their central role in the diet of the working classes in Europe during this period. Meat, with a notable presence of boiled beef and charcuterie, was consumed less regularly, which may indicate variations in income or seasonal food preferences. Coffee and chicory seem to be gaining in popularity, which could correspond to an increase in the consumption of stimulants to cope with long working hours. The mention of fats such as lard and common fat indicates a calorie-rich diet, essential to support the demanding physical work of the time. Alcohol consumption is uncertain towards the end of the period studied, suggesting changes in drinking habits or perhaps in the availability of alcoholic beverages. Fruit, butter and milk show variability that could reflect fluctuations in food supply or preferences over time. The changes in eating habits indicated by this table may be linked to the major socio-economic transformations of the period, such as industrialisation and improvements in transport and distribution infrastructures. It also suggests a possible improvement in living standards and social conditions within the Seraing community, although this would require further analysis to confirm. Overall, this table is a valuable document for understanding food culture in an industrial town, and may give some indication of the state of health and quality of life of its residents at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

| | 本表提供了 1843 年至 1908 年比利时塞林饮食习惯的历史窗口。每一列对应一个特定年份或时期,不同食物的消费情况用代码表示,以显示它们在当地饮食中的普遍程度。代码范围从 "XXXX "表示几乎完全食用,到 "X "表示较少食用。星号 "*"表示只提及该食物,而 "附属品 "或 "例外、聚会...... "等注释表示偶尔食用或与特定事件有关的食用。问号"? "表示消费不确定或没有记录,而 "质量一般 "则表示某些时候的产品质量较差。对该表的分析揭示了这一时期饮食的几个值得注意的方面。土豆和面包成为基本要素,反映了它们在这一时期欧洲工人阶级饮食中的核心作用。肉类,尤其是水煮牛肉和烤肉的食用频率较低,这可能表明收入或季节性饮食偏好的变化。咖啡和菊苣似乎越来越受欢迎,这可能与人们为应付长时间工作而增加食用兴奋剂有关。猪油和普通脂肪等油脂的摄入表明当时的饮食热量很高,这对于当时繁重的体力劳动是必不可少的。在所研究时期的末期,饮酒量并不确定,这表明饮酒习惯发生了变化,或许是酒精饮料的供应发生了变化。水果、黄油和牛奶的消费量变化不定,这可能反映了食品供应或偏好随时间推移而发生的波动。该表所显示的饮食习惯的变化可能与这一时期的重大社会经济变革有关,如工业化以及交通和分销基础设施的改善。它还表明塞拉英社区的生活水平和社会条件可能有所改善,但这需要进一步分析才能证实。总之,这份表格是了解工业城镇饮食文化的一份宝贵资料,它可以在一定程度上说明工业革命初期城镇居民的健康状况和生活质量。 |

|

| |

|

| The emergence of markets in industrial towns in the 19th century was a slow and often chaotic process. In these newly-formed towns, or those expanding rapidly as a result of industrialisation, the commercial structure struggled to keep pace with population growth and the influx of workers. Grocers and shopkeepers were rare and, because of their scarcity and lack of competition, they could afford to set high prices for foodstuffs and everyday consumer goods. This situation had a direct impact on the workers, the majority of whom were already living in precarious conditions, with wages often insufficient to cover their basic needs. Shopkeepers exploited workers through price gouging, driving workers into debt. This economic insecurity was exacerbated by low wages and vulnerability to economic and health hazards. Against this backdrop, companies were looking for solutions to compensate for the lack of services and shops, and to ensure a degree of control over their workforce. One such solution was the truck-system, a system of payment in kind whereby part of the workers' wages was paid in the form of foodstuffs or household goods. The company bought these products in bulk and redistributed them to its employees, often at prices determined by the company itself. The advantage of this system was that the company could retain and control its workforce, while guaranteeing an outlet for certain products. However, the truck-system had major disadvantages for the workers. It limited their freedom of choice in terms of consumption and made them dependent on the company for their basic needs. What's more, the quality of the goods supplied could be mediocre, and the prices set by the company were often high, further increasing the workers' indebtedness. The introduction of this system highlights the importance of the company in the daily lives of workers at the time, and illustrates the difficulties they faced in accessing consumer goods independently. It also reflects the social and economic dimension of industrial work, where the company is not just a place of production but also a central player in the lives of workers, influencing their food, housing and health.

| | 19 世纪工业城镇市场的兴起是一个缓慢且往往混乱的过程。在这些新形成的城镇或因工业化而迅速扩张的城镇中,商业结构难以跟上人口增长和工人涌入的步伐。杂货店主和店主非常稀少,由于他们的稀缺性和缺乏竞争,他们有能力为食品和日常消费品制定高价。这种情况对工人产生了直接影响,他们中的大多数人已经生活在不稳定的条件下,工资往往不足以满足他们的基本需求。店主通过哄抬物价剥削工人,使工人负债累累。工资低、容易受到经济和健康危害,加剧了这种经济上的不安全感。在这种背景下,公司开始寻找解决方案,以弥补服务和商店的不足,并确保对劳动力的一定程度的控制。其中一个解决方案是卡车系统,这是一种实物支付系统,工人的部分工资以食品或生活用品的形式支付。公司大量购买这些产品,然后重新分配给员工,价格通常由公司自己决定。这种制度的好处是,公司可以保留和控制其劳动力,同时保证某些产品的销路。然而,卡车系统对工人来说有很大的弊端。它限制了工人在消费方面的自由选择,使他们的基本需求依赖于公司。此外,供应的商品可能质量一般,公司定价往往很高,进一步增加了工人的负债。这一制度的引入凸显了公司在当时工人日常生活中的重要性,也说明了他们在独立获取消费品时所面临的困难。这也反映了工业工作的社会和经济层面,即公司不仅是生产场所,也是工人生活的核心角色,影响着他们的食物、住房和健康。 |

|

| |

|

| The perception of the worker as immature in the nineteenth century is a facet of the paternalistic mentality of the time, when factory owners and social elites often believed that workers lacked the discipline and wisdom to manage their own welfare, particularly where finances were concerned. This view was reinforced by class prejudice and by observing the difficulties workers had in rising above the conditions of poverty and the often miserable environment in which they lived. In response to this perception, as well as to the abject living conditions of the workers, a debate began about the need for a minimum wage that would allow workers to support themselves without falling into what the elites considered depraved behaviour ('debauchery'). Debauchery, in this context, could include alcoholism, gambling, or other activities deemed unproductive or harmful to social order and morality. The idea behind the minimum wage was to provide basic financial security that could, in theory, encourage workers to lead more stable and 'moral' lives. It was assumed that if workers had enough money to live on, they would be less inclined to spend their money irresponsibly. However, this approach did not always take into account the complex realities of working-class life. Low wages, long hours and difficult living conditions could lead to behaviour that elites considered debauchery, but which could be ways for workers to cope with the harshness of their existence. The minimum wage movement can be seen as an early recognition of workers' rights and a step towards the regulation of work, although it was also tinged with condescension and social control. This debate laid the foundations for later discussions on workers' rights, labour legislation and corporate social responsibility, which continued to evolve well into the nineteenth century.

| | 19 世纪认为工人不成熟的观点是当时家长式思想的一个方面,当时的工厂主和社会精英往往认为工人缺乏管理自身福利的纪律和智慧,尤其是在财务方面。阶级偏见以及观察到工人难以摆脱贫困和悲惨的生活环境,强化了这种观点。针对这种看法以及工人的悲惨生活条件,一场关于是否需要最低工资的辩论开始了,最低工资应使工人能够养活自己,而不至于陷入精英们所认为的堕落行为("放荡")。这里的 "放荡 "包括酗酒、赌博或其他被认为无益或有害于社会秩序和道德的活动。最低工资背后的理念是提供基本的经济保障,理论上可以鼓励工人过上更加稳定和 "道德 "的生活。人们假定,如果工人有足够的钱生活,他们就不会倾向于不负责任地花钱。然而,这种方法并不总是考虑到工人阶级生活的复杂现实。低工资、长工时和艰苦的生活条件可能会导致被精英阶层视为放荡的行为,但这也可能是工人应对恶劣生存环境的方式。最低工资运动可以看作是对工人权利的早期承认,也是朝着规范工作迈出的一步,尽管它也带有居高临下和社会控制的色彩。这场辩论为后来关于工人权利、劳动立法和企业社会责任的讨论奠定了基础,这些讨论一直持续到 19 世纪。 |

|

| |

|

| Engel's Law, named after the German economist Ernst Engel, is an empirical observation that points to an inverse relationship between household income and the proportion of it spent on food. According to this law, the poorer a household is, the greater the proportion of its limited resources it has to devote to essential needs such as food, because these expenses are incompressible and cannot be reduced beyond a certain point without affecting survival. This law has become an important indicator for measuring poverty and living standards. If a household spends a large part of its budget on food, this often indicates a low standard of living, as there is little left over for other aspects of life such as housing, health, education and leisure. In the 19th century, in the context of the industrial revolution, many workers lived in conditions of poverty and their wages were so low that they could not pay tax. This reflected not only the extent of poverty, but also the lack of financial resources available to governments to improve infrastructure and public services, as a broader tax base is often required to fund such developments. Over time, as the industrial revolution progressed and economies developed, real wages slowly began to rise. This was partly due to the increase in productivity brought about by new technologies and mechanisation, but also because of workers' struggles and demands for better working conditions and higher wages. These changes have contributed to a better distribution of wealth and a reduction in the proportion of expenditure devoted to food, reflecting an improvement in the general standard of living.

| | 恩格尔定律是以德国经济学家恩斯特-恩格尔的名字命名的,它是一项经验观察,指出家庭收入与用于食品的支出比例之间存在反比关系。根据这一定律,一个家庭越贫穷,其有限资源中用于食品等基本需求的比例就越大,因为这些支出是不可压缩的,不能减少到一定程度而不影响生存。这一规律已成为衡量贫困和生活水平的重要指标。如果一个家庭的大部分预算都花在食物上,这往往表明其生活水平较低,因为用于住房、健康、教育和休闲等其他方面的开支所剩无几。19 世纪,在工业革命的背景下,许多工人生活在贫困之中,他们的工资低到无法纳税。这不仅反映了贫困的程度,也反映了政府缺乏财政资源来改善基础设施和公共服务,因为通常需要更广泛的税收基础来为这些发展提供资金。随着时间的推移,随着工业革命的推进和经济的发展,实际工资开始缓慢上升。这一方面是由于新技术和机械化带来了生产力的提高,另一方面也是由于工人们为改善工作条件和提高工资而进行的斗争和提出的要求。这些变化促进了财富的更好分配,降低了食品支出的比例,反映了总体生活水平的提高。 |

|

| |

|

| The law does not stipulate that food expenditure decreases in absolute terms as income rises, but rather that its relative share of the total budget decreases. So a better-off person or household can absolutely spend more in absolute terms on food than someone less well-off, while devoting a smaller proportion of their total budget to this category of expenditure. For example, a low-income family might spend 50% of its total income on food, while a well-off family might spend only 15%. However, in terms of the actual amount, the well-off family may spend more on food than the low-income family simply because their total income is higher. This observation is important because it makes it possible to analyse and understand consumption patterns according to income, which can be crucial for the formulation of economic and social policies, particularly those relating to taxation, food subsidies and social assistance programmes. It also provides valuable information about the socio-economic structure of the population and changes in lifestyles as living standards improve.

| | 法律并没有规定食品支出的绝对值会随着收入的增加而减少,而是规定其在总预算中所占的相对份额会减少。因此,经济条件较好的个人或家庭绝对可以比经济条件较差的个人或家庭在食品上花费更多的绝对支出,而将总预算中较小的比例用于此类支出。例如,一个低收入家庭的食品支出可能占其总收入的 50%,而一个富裕家庭可能只花 15%。然而,就实际数额而言,富裕家庭在食品上的支出可能比低收入家庭多,原因很简单,因为他们的总收入更高。这一观察结果非常重要,因为它使我们有可能分析和了解按收入划分的消费模式,这对制定经济和社会政策,特别是与税收、粮食补贴和社会援助计划有关的政策至关重要。它还提供了有关人口的社会经济结构以及随着生活水平提高生活方式变化的宝贵信息。 |

|

| |

|

| = The ultimate judgement: the mortality of industrial populations = | | = 终极审判:工业人口的死亡率 = |

|

| |

|

| == The growth paradox == | | == 增长悖论 == |

| The 19th century era of industrial revolution and economic expansion was a period of profound and contrasting transformations. On the one hand, there was significant economic growth and unprecedented technical progress. On the other hand, this often translated into extremely difficult living conditions for workers in rapidly expanding urban centres. One dark reality of this period needs to be highlighted: rapid, unregulated urbanisation (what some call "uncontrolled urbanisation") led to unhealthy living conditions. Industrial towns, which grew at a frenetic pace to house an ever-increasing workforce, often lacked adequate infrastructure for sanitation and access to drinking water, leading to the spread of disease and a decline in life expectancy. In cities such as the English towns of the early 19th century, Le Creusot in France in the 1840s, the region of eastern Belgium around 1850-1860, or Bilbao in Spain at the turn of the 20th century - industrialisation was accompanied by devastating human consequences. Workers and their families, often crammed into overcrowded and precarious housing, were exposed to a toxic environment, both at work and at home, with life expectancy falling to levels as low as 30 years, reflecting the harsh working and living conditions. The contrast between urban and rural areas was also marked. While the industrial cities suffered, the countryside was able to enjoy improvements in quality of life thanks to a better distribution of the resources generated by economic growth and a less concentrated, less polluted environment. This period of history poignantly illustrates the human costs associated with rapid, unregulated economic development. It underlines the importance of balanced policies that promote growth while protecting the health and well-being of citizens.

| | 19 世纪是工业革命和经济扩张的时代,在这一时期发生了深刻而又截然不同的变革。一方面,经济大幅增长,技术空前进步。另一方面,在迅速扩张的城市中心,工人的生活条件往往极为艰苦。需要强调的是,这一时期的一个黑暗现实是:快速、无序的城市化(有人称之为 "失控的城市化")导致了不健康的生活条件。为了容纳越来越多的劳动力,工业城镇以疯狂的速度发展,但往往缺乏足够的卫生基础设施和饮用水,导致疾病传播和预期寿命下降。在 19 世纪初的英国城镇、19 世纪 40 年代的法国勒克鲁索、1850-1860 年左右的比利时东部地区或 20 世纪之交的西班牙毕尔巴鄂等城市,工业化伴随着对人类造成的毁灭性后果。工人及其家人往往挤在拥挤不堪、朝不保夕的住房中,在工作和家庭中都暴露在有毒的环境中,预期寿命低至 30 岁,这反映了恶劣的工作和生活条件。城乡之间的反差也很明显。在工业城市遭受苦难的同时,由于经济增长所带来的资源得到了更好的分配,环境的集中度较低、污染较少,农村的生活质量得以改善。这段历史生动地说明了快速、无序的经济发展所带来的人类代价。它强调了在促进增长的同时保护公民健康和福祉的平衡政策的重要性。 |

|

| |

|

| The origins of trade unionism date back to the Industrial Revolution, a period marked by a radical transformation in working conditions. Faced with long, arduous working days, often in dangerous or unhealthy environments, workers began to unite to defend their common interests. These first trade unions, often forced to operate underground because of restrictive legislation and strong employer opposition, set themselves up as champions of the workers' cause, with the aim of achieving concrete improvements in their members' living and working conditions. The trade union struggle focused on several key areas. Firstly, reducing excessive working hours and improving hygiene conditions in industrial environments were central demands. Secondly, the unions fought to obtain wages that would not only enable workers to survive, but also to live with a minimum of comfort. They also worked to ensure a degree of job stability, protecting workers from arbitrary dismissal and avoidable occupational hazards. Finally, trade unions have fought for the recognition of fundamental rights such as freedom of association and the right to strike. Despite adversity and resistance, these movements gradually won legislative advances that began to regulate the world of work, paving the way for a gradual improvement in working conditions at the time. In this way, the first trade unions not only shaped the social and economic landscape of their time, but also paved the way for the development of contemporary trade union organisations, which are still influential players in the defence of workers' rights around the world.

| | 工会主义的起源可以追溯到工业革命时期,这一时期的特点是工作条件发生了翻天覆地的变化。面对漫长、艰苦的工作日,而且往往是在危险或不健康的环境下工作,工人们开始联合起来捍卫他们的共同利益。由于限制性立法和雇主的强烈反对,这些首批工会往往被迫在地下运作,他们将自己定位为工人事业的捍卫者,旨在切实改善会员的生活和工作条件。工会斗争集中在几个关键领域。首先,减少过长的工作时间和改善工业环境的卫生条件是核心诉求。其次,工会努力争取工资,使工人不仅能够生存,而且能够过上最起码的舒适生活。工会还努力确保一定程度的工作稳定性,保护工人免遭任意解雇和可避免的职业危害。最后,工会还争取承认结社自由和罢工权等基本权利。尽管面临逆境和阻力,这些运动逐渐赢得了立法方面的进步,开始规范工作世界,为当时工作条件的逐步改善铺平了道路。这样,第一批工会不仅塑造了当时的社会和经济面貌,还为当代工会组织的发展铺平了道路,这些工会组织至今仍在世界各地捍卫工人权利方面发挥着重要作用。 |

|

| |

|

| The low adult mortality rate in industrial towns, despite precarious living conditions, can be explained by a phenomenon of natural and social selection. The migrant workers who came from the countryside to work in the factories were often those with the best health and the greatest resilience, qualities necessary to undertake such a change of life and endure the rigours of industrial work. These adults, then, represented a subset of the rural population characterised by greater physical strength and above-average boldness. These traits were advantageous for survival in an urban environment where working conditions were harsh and health risks high. On the other hand, children and young people, who were more vulnerable because of their incomplete development and lack of immunity to urban diseases, suffered more and were therefore more likely to die prematurely. On the other hand, adults who survived the first few years of working in the city were able to develop a certain resistance to urban living conditions. This is not to say that they did not suffer from the harmful effects of the unhealthy environment and the exhausting demands of factory work; but their ability to persevere despite these challenges was reflected in a relatively low mortality rate compared with younger, more fragile populations. This dynamic is an example of how social and environmental factors can influence mortality patterns within a population. It also highlights the need for social reform and improved working conditions, particularly to protect the most vulnerable segments of society, especially children.

| | 尽管生活条件岌岌可危,但工业城镇的成人死亡率却很低,这可以用自然和社会选择现象来解释。从农村来到工厂工作的外来务工人员往往具有最好的健康状况和最强的应变能力,这些都是改变生活方式和忍受艰苦工业劳动所必需的素质。因此,这些成年人代表了农村人口中的一个子集,其特点是体力充沛、胆识过人。这些特点有利于他们在工作条件恶劣、健康风险高的城市环境中生存。另一方面,儿童和年轻人由于发育不完全,对城市疾病缺乏免疫力,因此更容易受到伤害,也更容易过早死亡。另一方面,在城市工作头几年幸存下来的成年人能够对城市生活条件产生一定的抵抗力。这并不是说他们没有受到不健康环境的有害影响和工厂工作的疲惫要求;但与更年轻、更脆弱的人群相比,他们在这些挑战面前坚持下来的能力反映在相对较低的死亡率上。这种动态是社会和环境因素如何影响人口死亡率模式的一个例子。它还凸显了社会改革和改善工作条件的必要性,尤其是保护社会最弱势群体,特别是儿童的必要性。 |

|

| |

|

| == The environment more than work == | | == 环境比工作更重要 == |

| The observation that the environment had a greater lethal impact than work itself during the Industrial Revolution highlights the extreme conditions in which workers lived at the time. Although factory work was extremely difficult, with long hours, repetitive and dangerous work, and few safety measures, it was often the domestic and urban environment that was the most lethal. Unsanitary housing conditions, characterised by overcrowding, lack of ventilation, little or no waste disposal infrastructure and poor sewage systems, led to high rates of contagious diseases. Diseases such as cholera, tuberculosis and typhoid spread rapidly in these conditions. In addition, air pollution from burning coal in factories and homes contributed to respiratory and other health problems. Narrow, overcrowded streets, a lack of green areas and clean public spaces, and limited access to clean drinking water exacerbate public health problems. The impact of these deleterious environmental conditions was often immediate and visible, leading to epidemics and high mortality rates, particularly among children and the elderly, who were less able to resist disease. This highlighted the critical need for health and environmental reforms, such as the improvement of housing, the introduction of public health laws, and the creation of sanitation infrastructures, to improve the quality of life and health of urban populations.

| | 在工业革命期间,环境比工作本身具有更大的致命影响,这一观察结果凸显了当时工人的极端生活条件。虽然工厂工作极其艰苦,时间长,工作重复且危险,安全措施少,但最致命的往往是家庭和城市环境。住房条件不卫生,其特点是过度拥挤、缺乏通风、几乎没有或根本没有垃圾处理基础设施以及下水道系统不完善,导致传染病高发。在这种条件下,霍乱、肺结核和伤寒等疾病迅速蔓延。此外,工厂和家庭燃煤造成的空气污染也引发了呼吸道和其他健康问题。狭窄、拥挤的街道,缺乏绿地和清洁的公共空间,以及难以获得清洁的饮用水,都加剧了公共卫生问题。这些有害环境条件的影响往往是直接而明显的,导致流行病和高死亡率,尤其是抵抗疾病能力较弱的儿童和老年人。这凸显了卫生和环境改革的迫切需要,如改善住房、出台公共卫生法、建立卫生基础设施等,以提高城市人口的生活质量和健康水平。 |

|

| |

|

| The Le Chapelier law, named after the French lawyer and politician Isaac Le Chapelier who proposed it, is an emblematic law of the post-revolutionary era in France. Enacted in 1791, the law aimed to abolish the guilds of the Ancien Régime, as well as any form of professional association or grouping of workers and craftsmen. The historical context is important for understanding the reasons for this law. One of the aims of the French Revolution was to destroy feudal structures and privileges, including those associated with guilds and corporations, which controlled access to trades and could set prices and production standards. In this spirit of abolishing privileges, Le Chapelier's law aimed to liberalise labour and promote a form of equality before the market. The law also prohibited coalitions, i.e. agreements between workers or employers to set wages or prices. In this sense, it opposed the first movements of workers' solidarity, which could threaten the freedom of trade and industry advocated by the revolutionaries. However, by prohibiting any form of association between workers, the law also had the effect of severely limiting the ability of workers to defend their interests and improve their working conditions. Trade unions did not develop legally in France until the Waldeck-Rousseau law of 1884, which reversed the ban on workers' coalitions and authorised the creation of trade unions.

| | 勒夏贝尔法》以提出该法的法国律师和政治家伊萨克-勒夏贝尔命名,是法国大革命后的一部标志性法律。该法于 1791 年颁布,旨在废除旧制度下的行会以及任何形式的专业协会或工人和手工业者团体。历史背景对于理解这部法律的原因非常重要。法国大革命的目标之一是摧毁封建结构和特权,包括与行会和公司相关的特权,因为它们控制着行业准入,可以制定价格和生产标准。本着废除特权的精神,勒沙佩利埃的法律旨在解放劳动力,促进市场面前人人平等。该法还禁止联盟,即工人或雇主之间为确定工资或价格而达成的协议。从这个意义上说,它反对工人的第一次团结运动,因为这可能会威胁到革命者所倡导的贸易和工业自由。然而,由于禁止工人之间任何形式的联合,法律也严重限制了工人维护自身利益和改善工作条件的能力。直到 1884 年《瓦尔德克-卢梭法》(Waldeck-Rousseau law)撤销了对工人联合的禁令,并授权成立工会,工会才在法国合法发展起来。 |

|

| |

|

| Immigration to industrial areas in the 19th century was often a phenomenon of natural selection, with the hardiest and most adventurous leaving their native countryside in search of better economic opportunities. These individuals, because of their stronger constitution, had a slightly higher life expectancy than the average, despite the extreme working conditions and premature physical wear and tear they suffered in the factories and mines. Early old age was a direct consequence of the arduous nature of industrial work. Chronic fatigue, occupational illnesses and exposure to dangerous conditions meant that workers 'aged' faster physically and suffered health problems normally associated with older people. For the children of working-class families, the situation was even more tragic. Their vulnerability to disease, compounded by deplorable sanitary conditions, dramatically increased the risk of infant mortality. Contaminated drinking water was a major cause of diseases such as dysentery and cholera, which led to dehydration and fatal diarrhoea, particularly in young children. Food preservation was also a major problem. Fresh produce such as milk, which had to be transported from the countryside to the towns, deteriorated rapidly without modern refrigeration techniques, exposing consumers to the risk of food poisoning. This was particularly dangerous for children, whose developing immune systems made them less resistant to food-borne infections. So, despite the robustness of adult migrants, environmental and occupational conditions in industrial areas contributed to a high mortality rate, particularly among the most vulnerable populations such as children.

| | 19 世纪向工业地区的移民往往是一种自然选择现象,最坚韧、最富有冒险精神的人离开家乡寻找更好的经济机会。这些人由于体质较强,尽管在工厂和矿井中工作条件极端恶劣,身体过早损耗,但他们的预期寿命略高于普通人。过早衰老是艰苦的工业工作的直接后果。长期疲劳、职业病和暴露在危险环境中意味着工人身体 "衰老 "得更快,并遭受通常与老年人相关的健康问题。对于工人阶级家庭的子女来说,情况则更为悲惨。他们容易生病,再加上恶劣的卫生条件,大大增加了婴儿死亡的风险。受污染的饮用水是导致痢疾和霍乱等疾病的主要原因,这些疾病会导致脱水和致命的腹泻,尤其是对幼儿而言。食品保存也是一个大问题。牛奶等新鲜食品必须从农村运往城镇,如果没有现代冷藏技术,这些食品就会迅速变质,使消费者面临食物中毒的危险。这对儿童尤其危险,因为他们的免疫系统正在发育,对食源性感染的抵抗力较弱。因此,尽管成年移民身体强壮,但工业区的环境和职业条件导致了高死亡率,尤其是在儿童等最脆弱人群中。 |

|

| |

|

| == Cholera epidemics == | | == 霍乱疫情 == |

|

| |

|

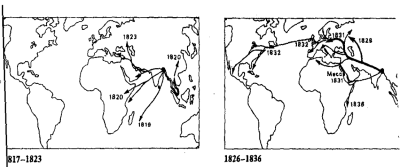

| [[Fichier:Peur bleu choléra cheminement.png|400px|vignette|Progagation of the cholera epidemics of 1817-1923 and 1826-1836]] | | [[Fichier:Peur bleu choléra cheminement.png|400px|vignette|1817-1923 年和 1826-1836 年霍乱流行病的进展情况]] |

|

| |

|

| Cholera is a striking example of how infectious diseases can spread on a global scale, facilitated by population movements and international trade. In the 19th century, cholera pandemics illustrated the increasing connectivity of the world, but also the limits of medical understanding and public health at the time. The spread of cholera began with British colonisation of India. The disease, which is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, was carried by merchant ships and troop movements, following the major trade and military routes of the time. The increase in international trade and the densification of transport networks enabled cholera to spread rapidly around the world. Between 1840 and 1855, during the first global cholera pandemic, the disease followed a route from India to other parts of Asia, Russia, and finally Europe and the Americas. These pandemics hit entire cities, causing massive deaths and exacerbating the fear and stigmatisation of foreigners, particularly those of Asian origin, perceived at the time as the vectors of the disease. This stigmatisation was fuelled by feelings of cultural superiority and notions of 'barbarism' attributed to non-European societies. In Europe, these ideas were often used to justify colonialism and imperialist policies, based on the argument that Europeans were bringing 'civilisation' and 'modernity' to parts of the world considered backward or barbaric. Cholera also stimulated major advances in public health. For example, it was by studying cholera epidemics that British physician John Snow was able to demonstrate, in the 1850s, that the disease was spread by contaminated water, a discovery that led to significant improvements in drinking water and sanitation systems.

| | 霍乱是一个鲜明的例子,说明传染病如何在人口流动和国际贸易的推动下在全球范围内传播。19 世纪,霍乱大流行说明了世界联系的日益紧密,同时也说明了当时医学认识和公共卫生的局限性。霍乱的传播始于英国对印度的殖民统治。霍乱是由霍乱弧菌引起的,通过商船和军队的移动,沿着当时的主要贸易和军事路线传播。国际贸易的增加和交通网络的密集化使霍乱迅速蔓延到世界各地。1840 年至 1855 年,在第一次全球霍乱大流行期间,霍乱沿着一条路线从印度蔓延到亚洲其他地区、俄罗斯,最后到达欧洲和美洲。这些大流行袭击了整个城市,造成大量死亡,加剧了人们对外国人的恐惧和鄙视,尤其是当时被视为疾病传播媒介的亚洲人。非欧洲社会的文化优越感和 "野蛮 "观念助长了这种鄙视。在欧洲,这些观念常常被用来为殖民主义和帝国主义政策辩护,理由是欧洲人将 "文明 "和 "现代性 "带到了世界上被认为落后或野蛮的地区。霍乱还推动了公共卫生领域的重大进步。例如,通过对霍乱流行病的研究,英国医生约翰-斯诺(John Snow)在十九世纪五十年代证明了霍乱是通过被污染的水传播的,这一发现促使饮用水和卫生系统得到了重大改善。 |

|

| |

|

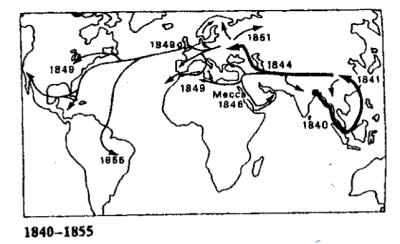

| Economic growth and social change in Europe during the 19th century were accompanied by fears and uncertainties about the consequences of modernisation. With rapid urbanisation, increasing population density in cities and often unsanitary conditions, European societies were confronted with new health risks. The theory that modernity enabled 'weak' individuals to survive was widespread, reflecting an understanding of the world influenced by Darwinian ideas of survival of the fittest. This perspective reinforced fears of a possible 'degeneration' of the population if infectious diseases were to spread among those deemed less resistant. The media coverage of epidemics played a crucial role in the public perception of health risks. News of the arrival of cholera or the first victims of the disease in a particular town was often accompanied by a sense of urgency and anxiety. Newspapers and broadsheets of the time carried this information, exacerbating fear and sometimes panic among the population. The disease also highlighted glaring social inequalities. Cholera disproportionately affected the poor, who lived in more precarious conditions and could not afford good hygiene or adequate food. This difference in mortality between social classes highlighted the importance of the social determinants of health. As for resistance to cholera thanks to a rich diet, the idea that gastric acids kill the cholera virus is partially true in the sense that a normal gastric pH is a defence factor against colonisation by vibrio cholerae. However, it is not a question of eating meat versus bread and potatoes. In fact, people who were malnourished or hungry were more vulnerable to disease, because their immune systems were weakened and their natural defences against infection were less effective. It is important to stress that cholera is not caused by a virus, but by bacteria, and that the survival of the micro-organism in the stomach depends on various factors, including the infectious load ingested and the person's general state of health. These epidemics have forced governments and societies to pay increased attention to public health, leading to investment in improved living conditions, sanitation and drinking water infrastructure, and ultimately to a reduction in the impact of such diseases.[[Fichier:choléra pandémie 1840 - 1855.png|400px|center|vignette|Cholera epidemic of 1840-1855]]

| | 19 世纪欧洲的经济增长和社会变革伴随着对现代化后果的恐惧和不确定性。随着城市化进程的加快、城市人口密度的增加以及卫生条件的恶化,欧洲社会面临着新的健康风险。现代性使 "弱者 "得以生存的理论广为流传,反映了受达尔文适者生存思想影响的对世界的理解。这种观点加剧了人们的担忧,即如果传染病在那些被认为抵抗力较弱的人群中传播,人口可能会 "退化"。媒体对流行病的报道在公众对健康风险的认识中起着至关重要的作用。霍乱来袭或某一城镇出现首例霍乱患者的消息往往伴随着一种紧迫感和焦虑感。当时的报纸和大报刊登了这些信息,加剧了人们的恐惧,有时甚至是恐慌。这种疾病还凸显了明显的社会不平等。霍乱对穷人的影响尤为严重,他们的生活条件更加岌岌可危,无法负担良好的卫生条件或充足的食物。社会阶层之间的死亡率差异凸显了健康的社会决定因素的重要性。至于通过丰富的饮食来抵御霍乱,胃酸杀死霍乱病毒的观点部分是正确的,因为正常的胃酸pH值是抵御霍乱弧菌定植的一个因素。然而,这并不是吃肉与吃面包和土豆的问题。事实上,营养不良或饥饿的人更容易患病,因为他们的免疫系统被削弱,对感染的自然防御能力较弱。必须强调的是,霍乱不是由病毒引起的,而是由细菌引起的,微生物在胃中的存活取决于各种因素,包括摄入的感染负荷和人的总体健康状况。这些流行病迫使各国政府和社会加强对公共卫生的关注,从而对改善生活条件、卫生和饮用水基础设施进行投资,最终减少此类疾病的影响。[[Fichier:choléra pandémie 1840 - 1855.png|400px|center|vignette|Cholera epidemic of 1840-1855]] |

|

| |

|

| [[Fichier:Choéra taux de mortalité par profession en haute marne.png|200px|vignette]] | | [[Fichier:Choéra taux de mortalité par profession en haute marne.png|200px|vignette]] |

|

| |

|