« The monetary system » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 77 : | Ligne 77 : | ||

[[Fichier:Intromacro agrégats monétaires zone euro 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|Les trois mesures du stock de monnaie dans la zone EURO en 2005 (MT).]] | [[Fichier:Intromacro agrégats monétaires zone euro 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|Les trois mesures du stock de monnaie dans la zone EURO en 2005 (MT).]] | ||

= | = Central banks and the money supply = | ||

== | == History of money and banking == | ||

The history of money is intimately linked to that of the banks (see video). | |||

From the XVIth-XVIIth century : | |||

* | *Depositing gold with a goldsmith to protect it from theft → received. | ||

* | * Use of receipts as a means of payment (beginning of fiat money). | ||

* | * Loan of gold on deposit against interest → goldsmiths become bankers. | ||

* | * For each gold bullion, issuing several notes → confidence in the repayment ability of the goldsmiths-bankers → reserves. | ||

*Increase of reserves against the risk of bankruptcies and creation of national banks controlling the issue of banknotes which were granted legal tender status. | |||

Until the First World War metal banknotes were convertible at the issuing institute at a rate established by the central bank (gold standard system). Convertibility was abandoned in the 1920s (coins and banknotes have a value conferred on them by general agreement, but no intrinsic value and they can no longer be exchanged for gold). | |||

== | == The role of central banks == | ||

In most countries, the quantity of money available (money supply) is controlled by the state and its supervision is delegated to an institution more or less independent of political power: the central bank. Central banks: | |||

:(i) | :(i)supervise the banking system and | ||

:(ii) | :(ii) ensure the stability of the monetary system by regulating the quantity of money in circulation in the economy and thereby influencing interest rates and sometimes the exchange rate. | ||

These instruments may affect inflation and the levels of output and employment in the short term, as will be discussed in the following chapters. | |||

The set of actions put in place by the central bank to influence the money supply and to supervise the proper functioning of the monetary system constitutes monetary policy. | |||

== | == The European Central Bank and the Eurosystem == | ||

The European Central Bank (ECB), located in Frankfurt, Germany, was created on June 1, 1998 by the 12 European countries (then 11, now 17) that make up the European Monetary Union, i.e. the 12 countries that have decided to adopt a single currency (the euro) and a common monetary policy. | |||

The ECB and all the central banks of the European Union Member States that have adopted the euro make up the Eurosystem. | |||

The main objective of the ECB is to promote financial and price stability in order to ensure non-inflationary growth. | |||

The ECB is supposed to be independent of political power. | |||

== The Bank of England | == The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve == | ||

The '''Bank of England''' is the central bank of the United Kingdom. Established in 1694, it obtained independence in interest rate management only in 1997. As with the ECB, the main objective of the Bank of England is to promote price stability, but it is the government that defines this objective in concrete terms. | |||

The '''Federal Reserve''' is the central bank of the United States. Created in 1913, the "FED", is composed of a board of governors (of which Ben Bernanke is the president, since 2006), the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), twelve regional banks (Federal Reserve Banks). The FOMC is the committee responsible for monetary policy and is made up of the seven members of the Board of Governors and the twelve presidents of the regional banks (of which only five have voting rights at any given time). | |||

== | == Role of the money supply == | ||

The size of the money supply is expected to change in line with the quantity of transactions taking place on the market, i.e. in line with the development of GDP (= proxy of the volume of transactions). | |||

As will become clearer in the rest of our lecture, when money supply and GDP do not move at the same pace or in the same direction, this is when economic problems (inflation, unemployment) may begin to arise. | |||

Central banks therefore undertake monetary policy actions aimed at influencing the evolution of the money supply. Measuring the money supply therefore enables the BC (Central Bank) to know whether it is necessary to act on the quantity of money available in the economy in the event of imbalances (inflation in particular). | |||

But: the quantity of money in circulation in the economic system is greater than the monetary base, which is directly controlled by the CB (<math>M1 > H</math>) and, to understand its evolution, it is also necessary to analyse the role played by the commercial banks... | |||

== | == Central bank instruments == | ||

THREE MAIN TOOLS | |||

Central banks govern the amount of currency in circulation in the country through money market interventions (open-market operations), which involve buying or selling government bonds (or other non-monetary assets): | |||

: | :If selling bonds → reduction of the money supply. | ||

: | :If buying → bonds, increase the supply of money. | ||

Central banks also control the activities of commercial banks, especially the issuance of book money, by means of the discount rate and the reserve requirement ratio. | |||

== | == The central bank's balance sheet == | ||

The central bank is a true bank of banks: its main customers are commercial banks (and not households or companies): it provides them with banknotes and scriptural money and manages interbank payments on their giro accounts. | |||

[[Fichier:Bilan des banques commerciales 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|Bilan simplifié d’une banque centrale (Par convention on inscrit dans la partie gauche du bilan les avoirs (actifs) et dans la partie droite les engagements (passifs).)]] | [[Fichier:Bilan des banques commerciales 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|Bilan simplifié d’une banque centrale (Par convention on inscrit dans la partie gauche du bilan les avoirs (actifs) et dans la partie droite les engagements (passifs).)]] | ||

== | == Creation of the monetary base == | ||

The monetary base (= asset or liability on the CB's balance sheet) is the currency issued by the central bank (coins and banknotes) + giro accounts. It is directly under the control of the BC. | |||

The central bank exchanges banknotes (or giro account assets) with commercial banks only as a counterpart: | |||

* | *gold | ||

* | *of foreign currency (foreign currency) | ||

* | *of acknowledgements of debt (the bank makes credit) | ||

BC therefore buys gold, foreign currency or securities with its currency (constitution of reserves). It never provides secondary banks with currency without a counterpart. By building up reserves, the BC therefore gives itself the means to recover the currency it has issued at a later date, i.e. either : | |||

* | *by selling its assets (gold or foreign exchange) | ||

* | *by getting the loans made to the banks reimbursed... | ||

Constitution | Constitution of reserves → increase in the supply of money Dissolution of reserves → decrease in the supply of money. | ||

== | == Commercial banks and the supply of money == | ||

The amount of money in circulation is influenced by the central bank's interventions in the asset market and its control over commercial banks and also by the commercial banks' decisions on deposits and loans to their customers. | |||

At any given time commercial banks must hold a certain fraction of the deposits received as reserves and they can lend the rest, thereby creating (scriptural) money → reinjecting money into the system. | |||

The fraction of the amount of deposits that banks are obliged to hold in the form of reserve requirements is the reserve requirement ratio. This coefficient is set by the central bank and can be changed according to the needs of monetary policy. NB: the effective reserve ratio of banks does not necessarily coincide with the reserve requirement ratio (banks may hold more reserves than those imposed by the central bank). | |||

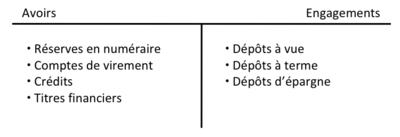

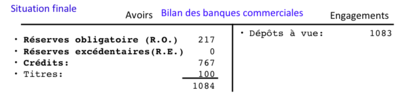

== | == The balance sheet of commercial banks == | ||

The financial position of banks at a given point in time is summarized in their balance sheets. By convention, the assets (assets) are shown on the left side of the balance sheet and the liabilities (liabilities) on the right side. | |||

[[Fichier:Bilan simplifié d’une banque commerciale 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|Bilan simplifié d’une banque commerciale.]] | [[Fichier:Bilan simplifié d’une banque commerciale 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|Bilan simplifié d’une banque commerciale.]] | ||

== | == Bank Money Creation and the Money Multiplier == | ||

The creation of scriptural money is exercised through the mechanism of credit: each time a bank that has excess reserves uses them to make credits, scriptural money is created. In general, the credits in turn give rise to deposits that make it possible to make new credits (once the required reserves have been subtracted) → phenomenon of multiplication of credits and deposits. | |||

== | == The Credit Multiplication Mechanism == | ||

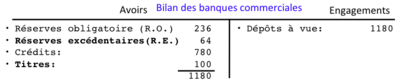

1. Les banques n’ont, par hypothèse, que des dépôts à vue et le montant des réserves couvrent leurs avoirs en numéraire et en comptes de virement. Par ailleurs, dans la situation initiale, la banque <math>A</math> n’a pas de réserves excédentaires. Par ailleurs, le coefficient des réserves obligatoires, r = 20%. | 1. Les banques n’ont, par hypothèse, que des dépôts à vue et le montant des réserves couvrent leurs avoirs en numéraire et en comptes de virement. Par ailleurs, dans la situation initiale, la banque <math>A</math> n’a pas de réserves excédentaires. Par ailleurs, le coefficient des réserves obligatoires, r = 20%. | ||

Version du 27 mars 2020 à 10:48

| Professeur(s) | |

|---|---|

| Cours | Introduction à la macroéconomie |

Lectures

- Aspects introductifs de la macroéconomie

- Le Produit Intérieur Brut (PIB)

- L'indice des prix à la consommation (IPC)

- Production et croissance économique

- Chômage

- Marché financier

- Le système monétaire

- Croissance monétaire et inflation

- La macroéconomie ouverte : concepts de base

- La macroéconomie ouverte: le taux de change

- Equilibre en économie ouverte

- L'approche keynésienne et le modèle IS-LM

- Demande et offre agrégée

- L'impact des politiques monétaires et fiscales

- Trade-off entre inflation et chômage

- La réaction à la crise financière de 2008 et la coopération internationale

Types of currency

The functions of money

Currency is the stock of assets that can be readily mobilized for transactions.

Beware of common parlance:

- "Have money" or "pay in cash" refers to cash. Around 10% of money is made up of cash.

- "Having money" or "earning a lot of money" refers to wealth or income. However, money is not wealth (assets or fortune) nor is it income.

It essentially has three functions:

- Reserve value (money is a means of transferring purchasing power from the present to the future).

- Unit of account (the unit of account by which economic transactions are measured).

- Intermediary of exchange (means used to purchase goods and services). In a barter economy, exchange requires the double coincidence of needs and economic agents can carry out only simple transactions. Money makes more indirect exchanges possible and reduces transaction costs.

Liquidity: the ease with which an asset can be converted into the medium of exchange of the economic system. Currency = the most liquid asset of all.

Types of currency

Money can be seen as a good with important positive externalities. The more people who accept it, the more useful it is for each individual.

Commodity money: most societies of the past used one or the other good with an intrinsic value (example: gold, but also camels, furs, salt... as the case may be).

'Fiduciary money (or fiat money): (Tangible) money devoid of any intrinsic value and which owes its status as money to the fact that the State has conferred legal tender on it (all metal coins and banknotes in circulation).

scriptural money: intangible money, represented by an accounting entry that can be transformed into fiduciary money at any time (all assets held at the bank or post office).

NB: Credit cards are simple media allowing the transfer of scriptural money over time.

Monetary aggregates

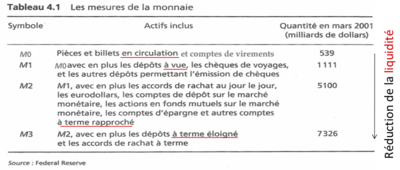

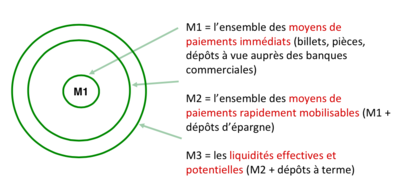

How is currency measured? Four types of monetary aggregates :

Normally "money" is understood to mean the aggregate M1. M0 (or, hereafter, H) is also referred to as the monetary base.

Monetary aggregates: euro area

Central banks and the money supply

History of money and banking

The history of money is intimately linked to that of the banks (see video).

From the XVIth-XVIIth century :

- Depositing gold with a goldsmith to protect it from theft → received.

- Use of receipts as a means of payment (beginning of fiat money).

- Loan of gold on deposit against interest → goldsmiths become bankers.

- For each gold bullion, issuing several notes → confidence in the repayment ability of the goldsmiths-bankers → reserves.

- Increase of reserves against the risk of bankruptcies and creation of national banks controlling the issue of banknotes which were granted legal tender status.

Until the First World War metal banknotes were convertible at the issuing institute at a rate established by the central bank (gold standard system). Convertibility was abandoned in the 1920s (coins and banknotes have a value conferred on them by general agreement, but no intrinsic value and they can no longer be exchanged for gold).

The role of central banks

In most countries, the quantity of money available (money supply) is controlled by the state and its supervision is delegated to an institution more or less independent of political power: the central bank. Central banks:

- (i)supervise the banking system and

- (ii) ensure the stability of the monetary system by regulating the quantity of money in circulation in the economy and thereby influencing interest rates and sometimes the exchange rate.

These instruments may affect inflation and the levels of output and employment in the short term, as will be discussed in the following chapters.

The set of actions put in place by the central bank to influence the money supply and to supervise the proper functioning of the monetary system constitutes monetary policy.

The European Central Bank and the Eurosystem

The European Central Bank (ECB), located in Frankfurt, Germany, was created on June 1, 1998 by the 12 European countries (then 11, now 17) that make up the European Monetary Union, i.e. the 12 countries that have decided to adopt a single currency (the euro) and a common monetary policy.

The ECB and all the central banks of the European Union Member States that have adopted the euro make up the Eurosystem.

The main objective of the ECB is to promote financial and price stability in order to ensure non-inflationary growth.

The ECB is supposed to be independent of political power.

The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom. Established in 1694, it obtained independence in interest rate management only in 1997. As with the ECB, the main objective of the Bank of England is to promote price stability, but it is the government that defines this objective in concrete terms.

The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the United States. Created in 1913, the "FED", is composed of a board of governors (of which Ben Bernanke is the president, since 2006), the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), twelve regional banks (Federal Reserve Banks). The FOMC is the committee responsible for monetary policy and is made up of the seven members of the Board of Governors and the twelve presidents of the regional banks (of which only five have voting rights at any given time).

Role of the money supply

The size of the money supply is expected to change in line with the quantity of transactions taking place on the market, i.e. in line with the development of GDP (= proxy of the volume of transactions).

As will become clearer in the rest of our lecture, when money supply and GDP do not move at the same pace or in the same direction, this is when economic problems (inflation, unemployment) may begin to arise.

Central banks therefore undertake monetary policy actions aimed at influencing the evolution of the money supply. Measuring the money supply therefore enables the BC (Central Bank) to know whether it is necessary to act on the quantity of money available in the economy in the event of imbalances (inflation in particular).

But: the quantity of money in circulation in the economic system is greater than the monetary base, which is directly controlled by the CB () and, to understand its evolution, it is also necessary to analyse the role played by the commercial banks...

Central bank instruments

THREE MAIN TOOLS

Central banks govern the amount of currency in circulation in the country through money market interventions (open-market operations), which involve buying or selling government bonds (or other non-monetary assets):

- If selling bonds → reduction of the money supply.

- If buying → bonds, increase the supply of money.

Central banks also control the activities of commercial banks, especially the issuance of book money, by means of the discount rate and the reserve requirement ratio.

The central bank's balance sheet

The central bank is a true bank of banks: its main customers are commercial banks (and not households or companies): it provides them with banknotes and scriptural money and manages interbank payments on their giro accounts.

Creation of the monetary base

The monetary base (= asset or liability on the CB's balance sheet) is the currency issued by the central bank (coins and banknotes) + giro accounts. It is directly under the control of the BC.

The central bank exchanges banknotes (or giro account assets) with commercial banks only as a counterpart:

- gold

- of foreign currency (foreign currency)

- of acknowledgements of debt (the bank makes credit)

BC therefore buys gold, foreign currency or securities with its currency (constitution of reserves). It never provides secondary banks with currency without a counterpart. By building up reserves, the BC therefore gives itself the means to recover the currency it has issued at a later date, i.e. either :

- by selling its assets (gold or foreign exchange)

- by getting the loans made to the banks reimbursed...

Constitution of reserves → increase in the supply of money Dissolution of reserves → decrease in the supply of money.

Commercial banks and the supply of money

The amount of money in circulation is influenced by the central bank's interventions in the asset market and its control over commercial banks and also by the commercial banks' decisions on deposits and loans to their customers.

At any given time commercial banks must hold a certain fraction of the deposits received as reserves and they can lend the rest, thereby creating (scriptural) money → reinjecting money into the system.

The fraction of the amount of deposits that banks are obliged to hold in the form of reserve requirements is the reserve requirement ratio. This coefficient is set by the central bank and can be changed according to the needs of monetary policy. NB: the effective reserve ratio of banks does not necessarily coincide with the reserve requirement ratio (banks may hold more reserves than those imposed by the central bank).

The balance sheet of commercial banks

The financial position of banks at a given point in time is summarized in their balance sheets. By convention, the assets (assets) are shown on the left side of the balance sheet and the liabilities (liabilities) on the right side.

Bank Money Creation and the Money Multiplier

The creation of scriptural money is exercised through the mechanism of credit: each time a bank that has excess reserves uses them to make credits, scriptural money is created. In general, the credits in turn give rise to deposits that make it possible to make new credits (once the required reserves have been subtracted) → phenomenon of multiplication of credits and deposits.

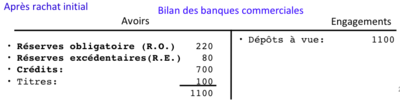

The Credit Multiplication Mechanism

1. Les banques n’ont, par hypothèse, que des dépôts à vue et le montant des réserves couvrent leurs avoirs en numéraire et en comptes de virement. Par ailleurs, dans la situation initiale, la banque n’a pas de réserves excédentaires. Par ailleurs, le coefficient des réserves obligatoires, r = 20%.

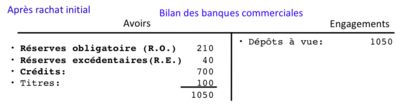

2. Supposons maintenant que la banque centrale décide d’augmenter la base monétaire en rachetant des titres à la banque (pour un montant de 100) et crédite en contrepartie les comptes de virement de la banque .

3. La banque se sert de ses réserves excédentaires pour faire de nouveaux prêts (pour un montant de 100). Cela à deux conséquences :

- a) L’octroi de prêts donne lieu à de nouveaux dépôts (par hypothèse, il n’y a pas de transformation de monnaie scripturale en numéraire pour le moment).

- b) La création de nouveaux dépôts nécessite l’augmentation des réserves obligatoires.

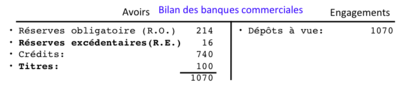

4. Le reste des réserves excédentaires donne lieu à de nouveaux prêts pour un montant de 80. Là encore, il n’y a pas de perte de réserves, mais la création de monnaie et transformation de réserves excédentaires en réserves obligatoires.

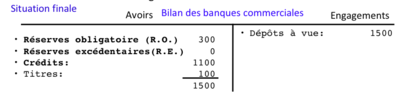

5. Le processus peut continuer jusqu’à ce qu’il n’y ait plus de réserves excédentaires, c’est-à-dire jusqu’à ce que toutes les réserves excédentaires initiales aient été transformées en réserves obligatoires. On obtient alors :

Offre de monnaie totale (maximum)

Au total, il y a eu 500 de monnaie scripturale créée, pour 100 de réserves excédentaires apparues initialement. Le multiplicateur de crédit est donc égal à 5.

Le multiplicateur de crédit est défini comme le rapport entre la variation totale des crédits, ΔCR, et la variation initiale des réserves excédentaires, ΔiRE.

Sous l’hypothèse qu’il n’y ait pas de ‘fuites’ du circuit du multiplicateur de crédit, c.à.d. que le secteur privé ne cherche pas à convertir une partie de la monnaie scripturale nouvellement créée en monnaie fiduciaire. Le multiplicateur de crédit est l’inverse du coefficient de réserves obligatoires ():

Dans l’exemple : => . Si , .

Il y a plusieurs manières de démontrer que . La plus simple consiste à faire remarquer que . Or · . Par conséquent,

En général :

Le multiplicateur monétaire : version complète

Exemple (Same same but different!)

1. Mêmes hypothèse que précédemment, que nous abandonnons l’hypothèse selon laquelle les agents du secteur non bancaires ne cherchent pas à échanger une partie de la monnaie scripturale nouvellement créée en numéraire. Dans ce cas, lorsque la banque fait un crédit, elle doit s’attendre à ce que la monnaie scripturale créée en contrepartie fasse l’objet d’un échange contre du numéraire. Cela signifie que la banque devra puiser dans ses réserves excédentaires pour fournir le numéraire demandé. Il y aura une diminution plus rapide des réserves excédentaires, du fait de cette fuite hors du circuit du multiplicateur de crédit, et ce dernier sera par conséquent moins élevés.

Appelons le coefficient de fuite, c.-à-d. la part de nouveaux crédits convertie en numéraire:

2. Idem

3’. La banque A se sert de ses réserves excédentaires pour faire de nouveaux prêts (pour un montant de 100). Néanmoins, le secteur non-bancaire désire en garder la moitié en numéraire: Hypothèse: .

4’. Le reste des réserves excédentaires donne lieu à de nouveaux prêts pour un montant de 40.

5’. Le processus peut continuer jusqu’à ce qu’il n’y ait plus de réserves excédentaires. On obtient alors :

Dans sa version complète (avec fuite), le multiplicateur de crédit devient :

Preuve:

Parce que le processus s’arrête lorsque les mises en réserves obligatoires et les fuites ont épuisé les réserves excédentaires initiales. En remplaçant l’accroissement des réserves obligatoires et les demandes de conversion en numéraire par leur valeur respectives, on a:

- (car et )

- (car )

Dès lors:

Les instruments de contrôle de la CB

Operations d’open-market : comme on a déjà dit, les banques centrales peuvent intervenir dans les marchés des actifs. Quand une CB achète (vend) des obligations de l’Etat la quantité de monnaie en circulation augmente (baisse).

Modification du coefficient de réserve : si la fraction minimale des dépôts qu’il faut garder sous forme de réserves augmente (baisse), la quantité de monnaie en circulation baisse (augmente). NB: traditionnellement les banques centrales n’ont utilisé cette mesure que très rarement, sauf en Chine dans les dernières années. Exemples: 10% USA, 20% CH, rien UK, rien Australie...

Modification du taux d’escompte (ou taux directeur) : les banques commerciales empruntent de l’argent à la banque centrale lorsque leurs réserves sont trop faibles au regard des réserves obligatoires. Si le taux d’escompte ↑ (↓) ⇒ l'offre de monnaie ↓ (↑). La plupart des banques centrales ont baissé ce taux dès le début de la dernière crise financière. Aujourd’hui les taux directeurs sont extrêmement bas.

Efficacité du contrôle de la banque centrale de l’offre de monnaie

Les banques centrales exercent un contrôle sur l’offre de monnaie qui est seulement partiel. En particulier, les banques centrales ne peuvent pas contrôler :

- la quantité de dépôts que les ménages décident de convertir en monnaie fiduciaire (fuites du circuit des crédits). Dans ce cas, si les agents privés détiennent en cash un pourcentage des dépôts, le multiplicateur devient , bonne approximation du vrai multiplicateur si et sont petits.

- le montant global des prêts accordés par les banques commerciales.

En résumé, comme la quantité de monnaie en circulation dans l’économie dépend en partie du comportement des banquiers et des déposants, le contrôle qu’exerce la banque centrale ne peut être qu’imparfait.

Dans la suite nous allons faire l’hp que la banque centrale contrôle parfaitement l’offre de monnaie.

Résumé

Le terme monnaie se réfère à l’ensemble des actifs utilisés par les ménages pour acheter des biens et des services

La monnaie recouvre trois fonctions: intermédiaire des échanges, unité de compte, réserve de valeur

La monnaie-marchandise est une monnaie qui a une valeur intrinsèque

La monnaie fiduciaire n’a aucune valeur intrinsèque

La banque centrale contrôle l’offre de monnaie à travers les opérations ‘open-market’, en modifiant le coefficient des réserves obligatoires, en changeant le taux d’escompte

La banque centrale ne peut pas contrôler le montant de prêts accordés par les banques commerciales ni le décisions de dépôts des ménages. En conséquence, le contrôle de la banque centrale sur l’offre de monnaie est seulement partiel

Certaines causes de l’inflation (= augmentation du niveau général des prix) sont liées aux déterminants de la demande (chapitre suivant) et de l’offre (ce chapitre) de monnaie.

Annexes

- David James Gill and Michael John Gill | The New Rules of Sovereign Debt | Foreignaffairs.com,. (2015). Retrieved 23 January 2015, from http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/142804/david-james-gill-and-michael-john-gill/the-great-ratings-game

References

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Genève

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur le site de l'Université de Neuchâtel

- ↑ Page personnelle de Federica Sbergami sur Research Gate

- ↑ Researchgate.net - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Google Scholar - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ VOX, CEPR Policy Portal - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Nicolas Maystre's webpage

- ↑ Cairn.ingo - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Linkedin - Nicolas Maystre

- ↑ Academia.edu - Nicolas Maystre

![{\displaystyle =100+80+64+51.2+...=100[1+(1-0.2)+(1-0.2)2+(1-0.2)3+...]=\lim _{n\to \infty }\sum _{i=0}^{n}100\times (1-0.2)^{i}={\frac {100}{1-(1-0.2)}}={\frac {100}{0.2}}=500}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9fd72fc4a1fc7a1105acd59867c384c23b9f1f47)

![{\displaystyle =r[(1-c)\Delta CR]+c\Delta CR}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f4f72366cad05c9a6e6a8d2e7b6400ba75ab48c7)

![{\displaystyle =\Delta CR[c+r(1-c)]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e33ca7ccc289e737b13639c4adc03da92f80bdef)