旧政体的人口制度:平衡状态

根据米歇尔-奥利斯(Michel Oris)的课程改编[1][2]

地结构与乡村社会: 前工业化时期欧洲农民分析 ● 旧政体的人口制度:平衡状态 ● 十八世纪社会经济结构的演变: 从旧制度到现代性 ● 英国工业革命的起源和原因] ● 工业革命的结构机制 ● 工业革命在欧洲大陆的传播 ● 欧洲以外的工业革命:美国和日本 ● 工业革命的社会成本 ● 第一次全球化周期阶段的历史分析 ● 各国市场的动态和产品贸易的全球化 ● 全球移民体系的形成 ● 货币市场全球化的动态和影响:英国和法国的核心作用 ● 工业革命时期社会结构和社会关系的变革 ● 第三世界的起源和殖民化的影响 ● 第三世界的失败与障碍 ● 不断变化的工作方法: 十九世纪末至二十世纪中叶不断演变的生产关系 ● 西方经济的黄金时代: 辉煌三十年(1945-1973 年) ● 变化中的世界经济:1973-2007 年 ● 福利国家的挑战 ● 围绕殖民化:对发展的担忧和希望 ● 断裂的时代:国际经济的挑战与机遇 ● 全球化与 "第三世界 "的发展模式

15 世纪至 18 世纪期间,前工业化时期的欧洲出现了一种奇妙的人口均衡状态,即 "人口均衡"。在这一充满变革的历史时期,社会和经济在人口制度的背景下发展,人口增长受到流行病、武装冲突和饥荒等调节力量的谨慎制衡。事实证明,这种自然的人口自我调节是稳定的引擎,协调了经济和社会的有序和可持续发展。

这种微妙的人口平衡不仅促进了欧洲人口的适度和可持续增长,也为经济和社会的协调发展奠定了基础。得益于这种平衡现象,欧洲成功地避免了极端的人口动荡,使其前工业化时期的经济和社会得以在渐进、可控的变革框架内蓬勃发展。

在这篇文章中,我们将仔细研究这一古老的人口机制的动态及其对工业化到来之前欧洲经济和社会结构的重要影响,并强调这种微妙的平衡如何促进了向更复杂的经济和社会结构的有序过渡。

旧制度下的死亡率危机

在旧政体时期,欧洲经常面临毁灭性的死亡危机,人们经常用 "天启四骑士 "的比喻来描述这种危机。这四位骑士分别代表了社会中的一种主要灾难,它们导致了高死亡率。

歉收、极端天气或经济混乱导致的饥荒是一种反复出现的灾难。饥荒削弱了人口的体质,降低了他们对疾病的抵抗力,导致最贫穷人口的死亡率急剧上升。饥荒期之后或与之相伴的往往是流行病,在普遍虚弱的情况下,流行病找到了滋生蔓延的肥沃土壤。战争是造成死亡的另一个主要原因。除了战场上的死亡外,冲突还对农业生产和基础设施造成有害影响,导致生活条件恶化以及与战争间接相关的死亡人数增加。流行病可能是最无情的杀手。瘟疫和霍乱等疾病不分青红皂白地肆虐,有时甚至会摧毁整个地区或村庄。缺乏有效的治疗方法和医学知识,加剧了它们的致命影响。最后,代表死亡的骑士体现了这三种瘟疫的致命后果,以及衰老、事故和其他自然或暴力原因造成的日常死亡。这些死亡危机通过其直接和间接的后果,调节着欧洲的人口结构,使人口保持在当时资源所能承受的水平上。

这些骑手对旧制度社会的影响是巨大的,不可磨灭地塑造了当时的人口、经济和社会结构,并在欧洲历史上留下了深刻的烙印。

饥饿

直到 20 世纪 60 年代,占主导地位的观点一直认为饥饿是中世纪死亡的主要原因。然而,随着人们认识到有必要区分饥荒和饥荒,这种观点发生了变化。饥荒是一种灾难性事件,会造成巨大的致命后果,而饥荒则是中世纪生活中常见的现象,其特点是较为温和但频繁的食物短缺时期。在佛罗伦萨这样的城市,农业周期几乎被有节奏的饥荒期所打断,大约每四年就会发生一次粮食短缺。这些饥荒与农业生产和谷物资源管理的波动有关。在每个收获季节结束时,人们都会面临一个两难的选择:是消耗当年的产量以满足当下的需求,还是保留一部分用于下一季的播种。如果收成仅能满足人们的当下需求,而没有盈余用于储备或未来播种,就会出现饥荒年。由于必须保留一部分粮食用于播种,这种岌岌可危的状况更加严重。产量不足意味着人们不得不忍受一段时期的粮食限制,减少口粮,直到下一次收获,希望下一次能有更多的粮食。这些粮食短缺时期并不会像饥荒时期那样系统性地导致大规模死亡,但却对人口的健康和寿命产生了相当大的影响。长期营养不良会削弱对疾病的抵抗力,间接增加死亡率,尤其是儿童和老人等最脆弱人群的死亡率。因此,饥荒在中世纪脆弱的人口平衡中发挥了作用,微妙地塑造了中世纪的人口结构。

饥荒与饥荒之间的区别对于理解中世纪的生活条件和死亡因素至关重要。饥荒指的是在一定程度上可以控制的反复出现的粮食短缺时期,而饥荒指的是人们饿死的严重粮食危机,通常是由于气候灾害造成的严重收成不足。一个突出的例子是,1696 年左右冰岛火山爆发,引发了欧洲暂时性的气候变冷,有时被称为 "小冰河时期"。这一极端事件导致农业产量急剧下降,使欧洲大陆陷入毁灭性的饥荒。在芬兰,这一时期的惨剧几乎造成 30% 的人口死亡,凸显了前工业社会在气候灾害面前的极端脆弱性。在佛罗伦萨,历史表明,虽然粮食短缺是常客,每四年左右就会出现一次困难时期,但饥荒却是一种更为零星的灾难,平均每四十年就会发生一次。这一差异凸显了一个重要事实:尽管饥饿几乎是当时许多人的常伴,但饥荒造成的大规模死亡却相对罕见。因此,与 20 世纪 60 年代之前人们普遍持有的看法相反,饥荒并不是中世纪的主要死因。历史学家对这一观点进行了修正,认识到其他因素,如流行病和恶劣的卫生条件,在大规模死亡中所起的作用要大得多。这种细致入微的理解有助于更准确地描绘中世纪人们的生活和面临的挑战。

战争

该图显示了从 1320 年到 1750 年的 430 年间欧洲的战争次数。从曲线中我们可以看出,在此期间,军事活动起伏很大,有几个高峰可能与重大冲突时期相对应。这些高峰可能代表了百年战争、意大利战争、法国宗教战争、三十年战争等重大战争,以及 17 世纪和 18 世纪早期涉及欧洲列强的各种冲突。在编制数据时使用的 "三年滚动总和 "方法表明,这些数字是经过三年期平滑处理的,以便更清晰地反映趋势,而不是反映年度变化,因为年度变化可能更混乱,更不能代表长期趋势。值得注意的是,这种历史图表可以让研究人员找出军事活动的模式和周期,并将其与其他历史、经济或人口事件联系起来,从而更好地了解历史动态。

在整个中世纪直至近代初期,战争几乎是欧洲永恒不变的现实。然而,几个世纪以来,这些冲突的性质发生了显著变化,反映了更广泛的政治和社会发展。14 世纪,冲突的主要形式是小规模的封建战争。这些冲突往往是局部性的,主要是领主之间为争夺土地控制权或解决继承纠纷而发生的。尽管这些小规模冲突在地方层面上可能具有暴力性和破坏性,但其规模和后果都无法与后来的战争相提并论。随着民族国家的巩固和寻求将权力扩展到传统边界之外的君主的出现,14 世纪和 15 世纪出现了规模空前、破坏性空前的冲突。这些新的国家战争是由规模更大、组织更严密的常备军发动的,通常还得到新兴官僚机构的支持。战争因此成为国家政策的工具,其目标从征服领土到维护王朝霸权不一而足。这些冲突对平民的影响往往是间接的,但却是毁灭性的。由于当时军队的后勤保障还很原始,军事管理在很大程度上依赖于征用和掠夺所经地区的资源。战场上的军队直接从当地经济中获取养料,抢夺庄稼和牲畜,破坏基础设施,在平民中传播饥荒和疾病。战争因此成为非战斗人口的灾难,剥夺了他们生存所需的生活资料。造成平民死亡人数最多的并不是战争本身,而是军队贪得无厌的需求导致当地经济结构的崩溃。这种形式的粮食战争对人口产生了相当大的影响,不仅通过直接暴力减少了人口,还创造了不稳定的生活条件,助长了疾病和死亡。在这种情况下,战争既是破坏的引擎,也是人口危机的载体。

前现代的军事史清楚地表明,军队不仅是征服和毁灭的工具,也是疾病传播的强大媒介。跨越大陆和边界的军队调动在流行病的传播中发挥了重要作用,扩大了流行病的范围和影响。历史上黑死病的例子就是这一动态的悲惨写照。14 世纪,当蒙古军队围攻克里米亚的热那亚贸易站卡法时,无意中引发了一连串事件,导致了人类历史上最严重的健康灾难之一。在蒙古军队中已经存在的鼠疫通过袭击和贸易传播给了被围困的居民。卡法的居民感染了这种疾病,随后从海上逃回热那亚。当时,热那亚是世界贸易网络中的一个重要城市,这促进了瘟疫在意大利乃至整个欧洲的迅速传播。载有受感染者的船只从热那亚出发,将瘟疫带到了地中海的许多港口,并随着贸易路线和人口流动从这些港口向内陆传播。黑死病对欧洲的影响是灾难性的。据估计,这一大流行病导致 30% 至 60% 的欧洲人口死亡,造成大规模的人口衰退和深刻的社会变革。它严酷地揭示了战争和贸易如何与疾病相互作用,从而影响历史进程。因此,黑死病成为了一个时代的代名词,疾病可以以前所未有的速度和规模重塑社会的轮廓。

流行病

本图是一张历史图表,显示了 1347 年至 1800 年期间西北欧受鼠疫影响的地区数量,其中的三年滚动总和平滑了短时间内的变化。该图清楚地显示了几次主要的流行病,不同时期的高峰显示了疾病的强烈传播。第一个也是最明显的高峰是始于 1347 年的黑死病大流行。这一波疫情对当时的人口造成了毁灭性的后果,在短短几年内造成了大量欧洲人死亡。在第一个主要高峰之后,该图显示了其他几个重要事件,在这些事件中,受影响的地方数量有所增加,反映了疾病的周期性再现。这些高峰可能与一些事件相对应,如通过贸易或部队调动将病原体引入人群,以及有利于携带疾病的老鼠和跳蚤扩散的条件。在图表的末端,即 1750 年之后,流行病的频率和强度有所下降,这可能表明人们对这种疾病有了更好的了解、公共卫生水平有所提高、城市发展、气候变化或其他有助于减少鼠疫影响的因素。这些数据对于了解鼠疫对欧洲历史的影响以及人类应对流行病的演变非常有价值。

营养不良、疾病和死亡率之间的关系是了解历史人口动态的重要组成部分。在前工业社会,不确定且往往不稳定的食物供应导致人们更容易感染传染病。饥饿的人口由于无法定期获得充足的营养食品而变得虚弱,对感染的抵抗力大大降低,这大大增加了流行病期间的死亡风险。特别是鼠疫,在整个中世纪和中世纪之后的很长一段时间里,它都是欧洲反复出现的灾难,对社会和经济产生了深远的影响。14 世纪的 "黑死病 "也许是最臭名昭著的例子,它使欧洲大部分人口死亡。鼠疫一直持续到 18 世纪,证明了人类、老鼠等动物载体和鼠疫耶尔森氏菌等致病细菌之间复杂的相互作用。老鼠是感染这种细菌的跳蚤的载体,在人口稠密的城市和船上随处可见,这为疾病的传播提供了便利。然而,鼠疫的传播不能仅仅归咎于啮齿动物,人类的活动也起到了至关重要的作用。迁徙的军队和在贸易路线上旅行的商人是有效的传播媒介,因为他们将疾病从一个地区带到另一个地区,其速度之快往往是当时的社会所不具备的。这种疾病传播模式凸显了社会和经济基础设施在公共卫生方面的重要性,即使在古代也是如此。瘟疫流行的背景揭示了贸易和部队调动等看似无关的因素对人口健康产生直接和破坏性影响的程度。

14 世纪中叶袭击欧洲的黑死病被认为是人类历史上最具破坏性的大流行病之一。据估计,在 1348 年至 1351 年期间,欧洲大陆多达三分之一的人口被消灭。这一事件深刻影响了欧洲的历史进程,导致了重大的社会经济变革。鼠疫是由鼠疫耶尔森菌引起的一种传染病。它主要与老鼠有关,但实际上是跳蚤将细菌传播给人类。鼠疫的特点是出现气泡、淋巴结肿大,尤其是在腹股沟、腋窝和颈部。这种疾病极其痛苦,往往致命,传染率很高。鼠疫迅速传播的部分原因是当时恶劣的卫生条件。过度拥挤、缺乏公共卫生知识以及与啮齿动物的亲密共处为疾病的传播创造了理想的条件。根据一些理论,在这次大流行中发生了一种自然选择。最虚弱的个体最先倒下,而幸存下来的往往是那些具有天然抵抗力或已产生免疫力的人。这就解释了为什么在第一波致命的疫情过后,疾病会暂时消退。然而,这种免疫力并不是永久性的;随着时间的推移,没有天然免疫力的新一代变得易受感染,使疾病再次爆发。17 世纪,欧洲出现了新一轮的鼠疫。虽然这些流行病都是致命的,但并没有达到黑死病的灾难性程度。在法国,17 世纪很大一部分死亡仍然是由鼠疫造成的,这导致了 "超额死亡率"。瘟疫对旧政体人口结构的影响是,人口的自然增长(出生人数与死亡人数之间的差额)往往被瘟疫死亡人数所吸收。这导致了人口的相对稳定或停滞,由于瘟疫和其他疾病时不时地侵袭人口,长期净增长很少。

瘟疫无情地侵袭着整个人口,但某些因素会使个别人更容易受到感染。青壮年由于参与贸易、旅行甚至当兵,往往流动性较大,因此更容易感染鼠疫。这个年龄段的人也更有可能有广泛的社会接触,这增加了他们接触传染病的风险。鼠疫流行期间青壮年的高死亡率对人口产生了深远的影响,尤其是减少了未来的生育数量。未生育就死亡的个体代表着 "失去的生育",这种现象降低了后代的人口增长潜力。这种现象并非瘟疫时代独有。第一次世界大战后也出现了类似的现象。战争导致数百万年轻人死亡,这一代人在很大程度上成为 "失落的一代"。失落的一代 "指的是这些人如果幸存下来可能会有的孩子。这些损失对人口的影响远远超出了战场,影响了几十年的人口结构。这两次历史性灾难的后果可以从这些事件之后的年龄金字塔中看出,相应年龄段的人口出现了赤字。育龄人口的减少导致出生率自然下降、人口老龄化以及社会和经济结构的变化。这些变化往往需要进行重大的社会和经济调整,以应对新的人口挑战。

例如,在黑死病期间,最脆弱的人口--就抵御疾病的能力而言,通常被称为 "弱者"--损失惨重。那些幸存下来的人一般都有较强的抗病能力,他们或是幸运地受到了较轻的感染,或是天生或后天获得了抗病能力。这种自然选择的直接效果是降低了总死亡率,因为存活下来的人口比例更具复原力。然而,这种恢复力并不一定是永久性的。随着时间的推移,这个 "更强大 "的种群会逐渐老化,变得更容易受到其他疾病或同一种疾病复发的影响,尤其是在疾病发展的情况下。因此,死亡率可能会再次上升,这反映了复原力和脆弱性的循环。因此,死亡率曲线会出现连续的高峰和低谷。流行病发生后,由于抵抗力最强的个体存活下来,死亡率会下降,但随着时间的推移和其他压力因素(如饥荒、战争或新疾病的出现)的影响,死亡率可能会再次上升。这种 "孵化曲线 "反映了环境压力因素与人口动态之间的持续互动。瘟疫使出生人口超过死亡人口。因此,法国的人口无法增长,出现了人口停滞,因为出生人数超过死亡人数的盈余被疾病消灭了。今天,我们知道流行病是中世纪的主要死因。

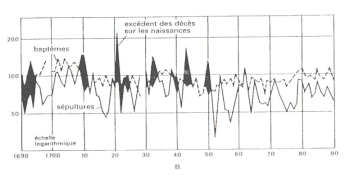

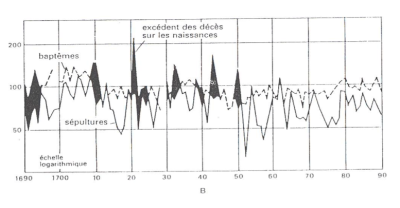

图中的黑白图表说明了 1690 年至 1790 年期间的洗礼率和埋葬率,Y 轴上的对数刻度用于测量频率。上部曲线用黑色实线和阴影区域表示洗礼,下部曲线用黑色虚线表示埋葬。图中显示了受洗人数超过埋葬人数的时期,即上部曲线高于下部曲线的区域。这些时期代表人口自然增长,即出生人数超过死亡人数。相反,也有埋葬人数超过洗礼人数的时候,这表明死亡率高于出生率,埋葬人数曲线高于洗礼人数曲线的区域就是这种情况。图中的剧烈波动说明了死亡人数超过出生人数的时期,其中的显著峰值表明发生了大规模死亡事件,如流行病、饥荒或战争。A 线似乎是一条趋势线或移动平均线,有助于直观地反映出这一世纪期间死亡人数超过出生人数的总体趋势。该图所涵盖的时期正值欧洲历史上的动荡时期,社会、政治和环境发生了重大变化,对当时的人口结构产生了深远影响。

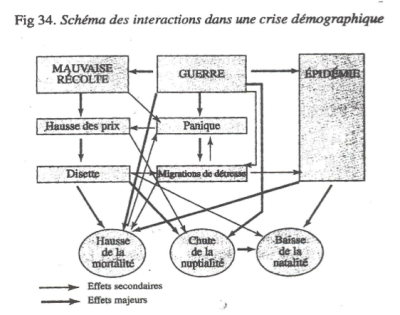

图中的概念图描述了人口危机中复杂的相互作用。引发危机的主要因素由图中央突出的三个大矩形表示:作物歉收、战争和流行病。这些中心事件相互关联,其影响波及一系列社会经济和人口现象。歉收是催化剂,导致价格上涨和粮食短缺,引发灾民迁移。战争造成恐慌,并通过类似的移民使局势恶化,而流行病则直接增加死亡率,同时也影响出生率和结婚率。这些重大危机影响着人口生活的各个方面。例如,物价上涨和饥荒导致经济困难,对婚姻和生育模式产生影响,表现为结婚率下降和出生率下降。此外,饥荒和战争造成的人口流动往往会加剧流行病,从而导致死亡率大幅上升。图中实线表示直接影响,虚线表示次要影响,显示了这些不同事件影响的等级。整个图表突出显示了危机引发的连锁效应,说明了歉收如何引发一系列超出其直接后果的事件,引发战争、移民和促进流行病的传播,从而导致死亡率上升和人口停滞或下降。

通过控制人口增长实现平衡

平衡的概念

平衡是一项基本原则,适用于许多生物和生态系统,包括人类及其与环境的互动。它是指一个系统在外部变化的情况下保持稳定内部状态的能力。在技术和作用于环境的手段有限的旧制度下,人口必须不断适应,才能利用现有资源维持这种动态平衡。饥荒、流行病和战争等危机考验着这种平衡的韧性。然而,即使面对这些破坏,社区也努力通过各种生存和适应战略重建平衡。尤其是农民,他们在维持人口平衡方面发挥着至关重要的作用。他们受作物歉收或气候变化的影响最为直接,但他们也是最先应对这些挑战的人。凭借对自然周期的经验知识和调整耕作方式的能力,他们能够减轻这些危机的影响。例如,他们可以交替种植作物,为困难年份储备粮食,或调整饮食以应对粮食短缺。此外,农村社区往往拥有团结和互助体系,使他们能够分散风险,并在发生危机时帮助最脆弱的成员。这种社会复原力是平衡的另一个方面,社会的凝聚力和组织有助于维持人口和社会平衡。因此,在这种情况下,"稳态 "与其说是一个主动控制环境的问题,不如说是一个适应性反应的问题,它使人口能够从干扰中生存和恢复,继续稳定和变化的循环。

在现代医学进步和工业革命之前,人类人口在很大程度上受到平衡原则的影响,该原则调节着可用资源和依赖资源的人口数量之间的平衡。为了生存,社会必须设法适应环境的限制。两年和三年轮作等农业技术是对粮食生产挑战的平衡反应。这些方法通过交替种植作物和休耕期,使土壤肥力得到恢复和再生,从而有助于防止土地枯竭,维持能够满足人口需求的生产水平。由于在工业革命的技术和农业革新之前,粮食资源无法大幅增加,因此人口调节通常是通过社会和文化机制来实现的。例如,欧洲的晚婚和永久独身制度通过缩短妇女的生育期从而降低出生率来限制人口增长。自然选择在人口动态中也发挥了作用。瘟疫等流行病和饥荒往往会消灭最脆弱的个体,留下的人口要么具有自然抵抗力,要么具有有助于生存的社会习俗。这种同态动态反映了生物和社会系统吸收干扰并恢复平衡状态的能力,尽管这种平衡可能与干扰前的水平不同。在生态系统中,一场大火可能会毁掉一片森林,但随后又会再生,人类社会也发展出了管理和克服危机的机制。

长期微观和宏观稳定

长期以来,人们在面对重大危机,尤其是死亡和疾病时无能为力,这种历史观受到了明显缺乏了解和控制这些事件的手段的影响。事实上,在现代和科学医学兴起之前,许多疾病和死亡的确切原因往往是神秘的。因此,中世纪和前现代社会严重依赖宗教、迷信和传统疗法来试图应对这些危机。然而,这种完全被动的观点受到了最新历史研究的挑战。现在人们认识到,即使面对瘟疫流行或饥荒等看似无法控制的力量,当时的人们也并非完全逆来顺受。农民和其他社会阶层制定了减轻危机影响的策略。例如,他们采用创新的耕作方法,引入检疫措施,甚至迁移到受饥荒或疾病影响较小的地区。所采取的措施也可以以社区为基础,例如组织慈善活动,为受危机影响最严重的人提供支持。此外,社会和家庭结构可以通过共享资源和支持最脆弱的成员,提供一定程度的复原力。第二次世界大战后,随着许多国家社会保障体系的建立、现代医疗保健的出现以及信息获取渠道的增加,情况发生了翻天覆地的变化,人们对公共卫生危机有了更好的了解和预防。由于这些发展,生活保障得到了改善,大大减少了面对疾病和死亡时的无力感。

社会法规:欧洲的晚婚和终身独身制度

实施: 16 世纪 - 18 世纪

从中世纪到前工业时代末期,欧洲人实施了一种人口调节策略,即欧洲晚婚和永久独身制度。历史数据显示,这种做法导致了相对较高的结婚年龄和相当高的独身率,尤其是在妇女当中。例如,根据历史学家的记载,在 16 世纪,女性的平均初婚年龄在 19 至 22 岁之间,而到了 18 世纪,许多地区的这一年龄上升到了 25 至 27 岁之间。这些数字表明,与中世纪的标准相差甚远,与世界其他地区结婚年龄更低、独身更少的情况形成鲜明对比。从未结婚的女性比例也很高。据估计,在 16 世纪到 18 世纪之间,10% 到 15%的女性终生单身。这种独身率导致了人口数量的自然限制,这在以土地为主要财富和生计来源的经济中尤为重要。这种婚姻和出生率制度可能受到经济和社会因素的影响。由于土地无法支持快速增长的人口,晚婚和永久独身成为一种人口控制机制。此外,由于继承制度趋向于平均分配土地,少生孩子意味着避免过度分割土地,这可能会导致农民家庭经济衰退。

圣彼得堡-的里雅斯特线路

晚婚和终身独身制是欧洲某些地区的特点,尤其是在西部和北部地区。西欧和东欧在婚姻习俗方面存在着巨大的社会和经济差异。在实行这种制度的西方,一条从圣彼得堡延伸到的里雅斯特的假想线标志着这种人口模式的边界。西部的农民和家庭通常拥有自己的土地或对土地拥有重要的权利,继承权通过家族世系传递。这些条件有利于实施限制生育战略,以保持家庭农场的完整性和活力。家庭力图避免土地世代分散,以免削弱其经济地位。然而,在这条线以东,特别是在农奴制地区,情况则有所不同。东欧的农民通常是农奴,他们被束缚在领主的土地上,没有财产可以继承。在这种情况下,没有通过晚婚或独身限制家庭规模的直接经济压力。婚姻习俗更为普遍,婚姻往往是出于社会和经济原因而安排的,并不直接考虑保护家族土地的策略。东西方之间的这种对立反映了工业革命大动荡之前欧洲社会经济结构的多样性,工业革命最终改变了整个欧洲大陆的婚姻制度和家庭结构。

人口效应

妇女的生育期通常估计为 15 至 49 年,这对了解历史人口动态至关重要。在一个女性平均结婚年龄不断提高的社会中(如 16 至 18 世纪的西欧),对总体生育率的影响是巨大的。当结婚年龄从 20 岁提高到 25 岁时,妇女开始生育的时间就会推迟,从而减少了她们可能受孕的年数。青春期后的几年往往是最容易受孕的时期,推迟 5 年结婚会使妇女失去生命中最容易受孕的许多年。这可能导致每个妇女的平均子女数下降,因为在其生育期内怀孕的机会会减少。如果我们考虑到妇女婚后平均每两年可以生育一个孩子,那么如果取消 5 年的潜在高生育期,就相当于每个妇女减少生育 2 到 3 个孩子。这一减少将对人口的总体增长产生重大影响。事实上,这种晚婚和限制生育的做法并不是因为对生殖生物学或避孕措施有了更好的了解,而是对生活条件的一种社会经济反应。通过限制子女数量,家庭可以更好地分配有限的资源,避免过度分割土地,保障后代的经济福祉。在现代计划生育出现之前,这种现象促成了一种自然的人口调节。

晚婚和终身独身

The system for regulating the birth rate in Western Europe, particularly from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, was largely based on social and religious norms that discouraged childbearing outside marriage. In this context, a significant number of women did not marry, remaining single or becoming widows without remarrying. If we take into account that, in some regions, up to 50% of women could be in this situation at any given time, the impact on overall birth rates would be considerable. Being unmarried and widowed meant, for most women in those days, that they had no legitimate children, partly because of strict social conventions and the teachings of the Catholic Church, which promoted chastity outside marriage. Late marriages were encouraged and sexual relations outside marriage were strongly condemned, reducing the likelihood of out-of-wedlock births. Illegitimate births were rare, with estimates around 2% to 3%. This suggests a relatively high level of conformity to social and religious norms, as well as effective control over sexuality and reproduction outside marriage. This social dynamic has therefore had the effect of significantly reducing overall fertility, with an estimated reduction of up to 30%. This played an essential role in the demographic regulation of the time, ensuring a balance between population and available resources in a context where there were few means of increasing the production of environmental resources. In this way, social structures and cultural norms served as a population control mechanism, maintaining demographic stability in the absence of modern contraceptive methods or medical interventions to regulate the birth rate.

The social and economic structure of pre-industrial Europe had a direct influence on marriage practices. The concept of "marriage equals household" was strongly entrenched in people's minds, meaning that a marriage was not just the union of two people but also the formation of a new, autonomous home. This implied the need to have their own living space, often in the form of a farm or house, where the couple could settle down and live independently. This need for a 'niche' in which to live limited the number of marriages possible at any given time. Marriage opportunities were therefore closely linked to the availability of housing, which in agricultural societies depended on the transmission of property, such as farms, often from generation to generation. Demographic growth was limited by the fixed amount of land and farms, which did not grow at the same rate as the population. As a result, young couples had to wait for a property to become available, either through the death of the previous occupants or when they were ready to give up their place, often to their children or other family members. This contributed to delaying marriage, as young people, particularly men who were often expected to take charge of a farm, had to wait until they had the economic means to support a household before marrying. By delaying marriage, women's fertility periods were also shortened, contributing to a fall in the overall birth rate. Thus, economic and housing limitations played a determining role in marriage and demographic strategies, fostering the emergence of the European model of late marriage and the nuclear household, which had a profound impact on social structures and population dynamics in Europe until the modernisation and urbanisation that accompanied the Industrial Revolution.

The role of family relationships and expectations of children was an important factor in the matrimonial and demographic strategies of pre-industrial European societies. In a context where pension and care systems for the elderly were non-existent, parents depended on their children for support in old age. This often meant that at least one child had to remain single to look after his or her parents. Typically, in a family with several children, it was not uncommon for a tacit or explicit agreement to designate one of the daughters to stay at home and look after her parents. This role was often taken on by a daughter, partly because sons were expected to work the land, generate income and perpetuate the family line. Unmarried daughters also had fewer economic and social opportunities outside the family, making them more available to care for their parents. This practice of permanent celibacy as a form of family 'sacrifice' had several consequences. On the one hand, it ensured a certain amount of support for the older generation, but on the other, it reduced the number of marriages and therefore the birth rate. This functioned as a natural demographic regulation mechanism within the community, contributing to the balance between population and available resources. These dynamics highlight the complexity of the links between family structure, economy and demography in pre-industrial Europe, and how personal choices were often shaped by economic necessity and family duties.

Demographic homeostasis, in the context of pre-industrial societies, reflects a process of natural population regulation in response to external events. When these societies were hit by mortality crises, such as epidemics, famines or conflicts, the population fell considerably. The indirect consequence of these crises was to free up economic and social 'niches', such as farms, jobs or roles in the community, which had previously been occupied by those who had died. This created new opportunities for the surviving generations. Young couples were able to marry earlier because there was less competition for resources and space. As early marriages are generally associated with a longer period of fertility and therefore a potentially higher number of children, the population could bounce back relatively quickly after a crisis. The increased fertility of young married couples compensated for the demographic losses suffered during the crisis, allowing the population to return to a state of equilibrium, according to the principles of homeostasis. This cycle of crisis and recovery demonstrates the resilience of human populations and their ability to adapt to changing conditions, albeit often at the cost of considerable loss of life. It is a demonstration of the concept of homeostasis applied to demography, where after a major external disruption, the social and economic systems inherent in these communities tended to bring the population back to a level that could be sustained by the resources available and the social structures in place.

Nuances in the European system: the three Swiss

The variety of matrimonial and inheritance practices in Switzerland reflects the way in which traditional societies adapted to economic and environmental constraints. In central Switzerland, the matrimonial system was influenced by strict regulations that restricted access to marriage, thereby favouring wealthy families. This restriction was often accompanied by an unequal pattern of land inheritance, generally favouring the eldest son. This dynamic had significant implications for non-heir children, who were forced to seek means of subsistence outside their place of birth. This constraint on marriage and inheritance had the effect of regulating the local population, leading to emigration which contributed to the demographic balance of the region. By leaving the region to seek their fortune elsewhere, the children who did not inherit avoided the overpopulation that could have resulted from an excessively fragmented division of farmland, thereby preserving the rural economy and social stability of their community of origin.

In the Valais, the matrimonial and inheritance situation contrasted sharply with that in central Switzerland. With no legal restrictions on marriage, individuals were able to marry more freely, regardless of their economic status. When it came to inheritance, Valais tradition favoured an egalitarian distribution of property. Brothers who did not become owners were often compensated, an arrangement that enabled them to start their own lives elsewhere, often by emigrating. These egalitarian inheritance practices regularly led to agreements between brothers to keep farmland intact within the family, voluntarily choosing a single heir to manage the land and continue the family business. In doing so, they ensured that the farms remained viable and that land ownership did not become too fragmented to remain productive. At the same time, it also contributed to a demographic balance, as brothers who left sought opportunities outside the Valais, reducing the pressure on local resources.

In Italian-speaking Switzerland, the social and demographic dynamic was strongly impacted by the professional mobility of men. A large number of men left their homes for extended periods, ranging from a few months to several years, to find work elsewhere. This migration of workers, often seasonal, resulted in a significant imbalance in the local marriage market, de facto reducing the number of possible marriages due to the prolonged absence of men. This absence reduced the opportunities for new families to form, thus limiting the birth rate. In addition, prevailing social conventions and religious values kept women in traditional roles and encouraged marital fidelity. In such a context, women had few opportunities or social tolerance for having children outside marriage. Thus, cultural norms combined with the absence of men played a key role in maintaining a certain demographic balance, limiting natural population growth in Italian-speaking Switzerland.

These various practices illustrate how the regulation of demographic growth could be indirectly orchestrated by social, economic and cultural mechanisms. They made it possible to manage the size of the population according to the capacities of the environment and resources, ensuring the continuity of family structures and the economic stability of communities.

A return to omnipresent death

The traditional structure of a complete family involves a long-term commitment, with the couple remaining together from the time of their marriage until the end of the woman's fertility period, generally around the age of 50. If this continuity is maintained without interruption, theory suggests that a woman could have an average of seven children during her lifetime. However, this ideal situation is often affected by disruptions such as the premature death of one of the spouses. The premature death of a spouse, whether husband or wife, before the woman reaches the age of 50, can significantly reduce the number of children the couple could have had. Such family breakdowns are common because of health conditions, illness, accidents or other risk factors linked to the times and the social and economic context. When these premature deaths and their effects on family structure are taken into account, the average number of children per family tends to fall, with an average of four to five children per family. This reduction also reflects the challenges of family life and the mortality rates of the time, which had a strong influence on demographics and household size.

Throughout the centuries, childhood has always been a particularly vulnerable period for human survival, and this was even more marked in the pre-modern context where medical knowledge and living conditions were far from optimal. In those days, a considerable number of children - between 20% and 30% - did not survive their first year of life. What's more, only half the children born reached the age of fifteen. This meant that the average couple produced only two to two-and-a-half children who reached adulthood, which was hardly enough for more than simple population replacement. As a result, population growth remained stagnant. This precariousness of existence and familiarity with death profoundly shaped the psyche and social practices of the time. Populations developed homeostasis mechanisms, strategies for maintaining demographic equilibrium despite the uncertainties of life. At the same time, death was so omnipresent that it became an integral part of daily life. The origin of the term "caveau" bears witness to this integration; it refers to the practice of burying family members in the cellar of the house, often because of a lack of space in cemeteries. This relationship with death is striking when we consider the history of Paris in the 18th century. For public health reasons, the city undertook to empty its overcrowded cemeteries within its walls. During this operation, the remains of more than 1.6 million people were exhumed and transferred to the catacombs. This radical measure underlines just how common death was and how little place it left, both literally and figuratively, in the society of the time. Death was not a stranger, but a familiar neighbour that had to be lived with.

The acceptance of and familiarity with death in pre-modern society can also be seen in the existence of guides and manuals teaching how to die appropriately, often under the title of "Ars Moriendi" or the art of dying well. These texts were widespread in Europe as early as the Middle Ages, offering advice on how to die in a state of grace, in accordance with Christian teachings. These manuals offered instructions on how to deal with the spiritual temptations that might arise as death approached, and how to overcome them in order to ensure the soul's salvation. They also dealt with the importance of receiving the sacraments, making peace with God and man, and leaving behind instructions for settling one's affairs and distributing one's possessions. In this context, death was not only an end but also a critical passage that required preparation and reflection. Even in the darkest moments, such as when a person was condemned to death, this culture of death offered a paradoxical form of consolation: unlike many others who died suddenly or without warning, the condemned person had the opportunity to prepare for his last moment, to repent of his sins and to leave in peace with his conscience. This reflected a very different perception of death from the one we have today, where sudden death is often considered the cruellest, whereas in those more ancient times, such an unprepared death was seen as a tragedy for the soul.

Annexes

- Carbonnier-Burkard Marianne. Les manuels réformés de préparation à la mort. In: Revue de l'histoire des religions, tome 217 n°3, 2000. La prière dans le christianisme moderne. pp. 363-380. url :/web/revues/home/prescript/article/rhr_0035-1423_2000_num_217_3_103