Une brève histoire du capitalisme international

Ce cours va fournir au lecteur une brève histoire du capitalisme mondial. Ce que l'on entend par capitalisme mondial ou économie politique internationale est la structure et la dynamique des relations économiques internationales.

Il ne s'agit pas d'une histoire typique de l'économie internationale dans la mesure où nous n'allons pas nous pencher sur des questions telles que l'évolution de la productivité dans les différents pays ou les niveaux de production dans les différents pays. Il s'agit là d'une question purement économique, qui se réfère à la dynamique des économies nationales.

Ce n'est donc pas une histoire typique de l'économie internationale. Il s'agit d'une tentative de fournir une histoire de l'évolution de la manière dont les relations économiques internationales se sont développées au cours du 19e siècle.

Nous allons examiner quatre périodes distinctes. Dans chacune d'elles, nous examinerons le commerce, les relations commerciales internationales, les investissements et la structure de la production, la monnaie et les finances, ainsi que certaines considérations sur la dynamique géopolitique et le développement idéologique. Il s'agit d'une tentative de périodiser l'histoire politique des 200 dernières années, avec des phases distinctes de développement du capitalisme mondial au cours des 200 dernières années.[1]

La première est appelée la Première Mondialisation ce que d'autres appellent les années du libéralisme classique, l'âge d'or qui est la période allant du milieu du XIXe siècle à la Première Guerre mondiale. Nous examinerons ensuite l'intégration du capitalisme mondial dans l'entre-deux-guerres. La troisième période est appelée le libéralisme intégré et se réfère à la première étape de l'après-guerre, de la fin des années 1940 jusqu'au milieu des années 1970, puis à la dernière étape qui est l'étape actuelle de la deuxième mondialisation qui commence au milieu des années 1970 et qui continue à se développer.

La première mondialisation

Les origines de la première mondialisation

Quand la mondialisation a-t-elle commencé ?[2]

Certains auteurs affirment qu'il y a toujours eu une économie mondiale, et qu'il y a toujours eu des interactions économiques, des échanges entre des entités éloignées les unes des autres. D'autres disent que cela commence avec le commerce triangulaire lié à la découverte des Amériques. D'autres encore disent qu'en fait, le capitalisme mondial est apparu dans le premier tiers du XIXe siècle et à cause de la révolution des transports de la fin du XVIIIe siècle qui a conduit à une intégration beaucoup plus poussée des marchés, à une convergence des prix entre des économies distinctes, qui sont entrées progressivement en contact les unes avec les autres et se sont progressivement intégrées.[3][4]

Pour Kevin O’Rourke et John Williamson, le capitalisme mondial émerge dans les années 1820. Dans Globalization and history: the evolution of a nineteenth-century Atlantic economy ils documentent le fait qu'à partir des années 1820, il existe un processus séculaire de convergence des prix, ce qui signifie qu'une division internationale du travail se met en place et caractérise la caractéristique distinctive d'une économie mondiale intégrée.[5] C'est un facteur clé sans lequel nous ne pourrions pas parler de capitalisme mondial.

En termes idéologiques, la "révolution des transports" et l'"intégration des marchés" au 18e siècle s'accompagnent du déclin du mercantilisme et de la montée du libéralisme qui est l'essor de l'idéologie du libre-échange.[6][7]

Portrait de David Ricardo par Thomas Phillips, vers 1821. Ce tableau montre Ricardo, âgé de 49 ans, deux ans avant sa mort.

Entre la fin du XVIIIe siècle et les années 1820, de nombreuses personnes en Angleterre et surtout, Adam Smith et David Ricardo ont développé la théorie de des avantages comparatifs qui est devenu un principe fondamental de la théorie du commerce international. Elle fait référence à la capacité d'une économie à produire des biens et des services à un coût d'opportunité inférieur à celui des partenaires commerciaux. Un avantage comparatif donne à une entreprise la capacité de vendre des biens et des services à un prix inférieur à celui de ses concurrents et de réaliser des marges de vente plus importantes.[8]

L'idée de la théorie développée par Ricardo dans Des principes de l'économie politique et de l'impôt publié en 1817 est que les États devraient cesser de se préoccuper de la balance commerciale, qu'ils devraient cesser de se préoccuper des États qui exportent plus qu'ils n'importent et qu'ils devraient cesser de se soucier de produire tout ce qu'ils consomment dans leur économie.[9] Si une chose est produite plus efficacement et qu'elle est moins chère à importer, les États devraient l'importer, afin de libérer le pouvoir d'achat du consommateur. L'excédent peut donc être réinvesti dans l'économie nationale et développer les capacités de production. Selon la théorie de l'avantage comparatif, tous les acteurs peuvent, à tout moment, tirer mutuellement profit de la coopération et du commerce volontaire.

Ce qui suit est le libéralisme manchestérien qui s'est développée autour de Manchester, site de la première révolution industrielle, et notamment centre de l'industrie textile mondiale, à la fin du XVIIIe siècle et au début du XIXe siècle.[10][11][12] Cette école de pensée en est venue à dominer idéologiquement d'abord en Angleterre, puis elle s'est diffusée par différents canaux, d'abord en France, puis dans le reste de l'Europe à quelques exceptions près. Le libéralisme manchestérien fait également référence à un groupe d'hommes qui ont été responsables de l'abolition des Corn Laws et l'adoption du libre-échange par la Grande-Bretagne après 1846, comme Richard Cobden et Herbert Spencer. Les Corn Laws a bloqué l'importation de céréales bon marché, d'abord en interdisant simplement l'importation en dessous d'un prix déterminé, puis en imposant des droits d'importation élevés, rendant trop coûteuse l'importation de céréales de l'étranger, même lorsque les réserves alimentaires étaient insuffisantes. L'abolition des lois sur le maïs a permis aux travailleurs du Royaume-Uni de consommer des denrées alimentaires moins chères et d'assurer un emploi plus régulier, ce qui a symboliquement lancé la grande ère du libre-échange qui a duré jusqu'à la Première Guerre mondiale.

A cela s'ajoute un contexte géopolitique dans lequel l'Angleterre est la puissance dominante, que certains auteurs qualifient de Pax Britannica avec une économie mondiale qui est centrée et structurée autour de Londres.[13][14] Today, New York is the capital of global capitalism; in the 19th century, London was the capital of capitalism.[15][16]

Que font Londres et le Royaume-Uni ? Quelles sont les fonctions qu'ils assument ?

Face à ce capitalisme mondial, le Royaume-Uni a agi comme un hégémon qui a ancré le système en assumant plusieurs fonctions. Premièrement, il a fourni un libre accès au marché intérieur. Un libre-échange dominé par l'Angleterre signifiait que les autres pays pouvaient exporter librement vers le Royaume-Uni. Comme le Royaume-Uni avait la plus grande économie, il fournissait également les plus grands marchés d'exportation aux autres économies qui utilisaient cet accès à ce marché pour développer leur économie.

Par conséquent, le Royaume-Uni offrait un libre accès à son marché ainsi qu'aux capitaux pour les investissements dans le monde entier. La plupart des investissements dans les infrastructures qui ont eu lieu avant la Première Guerre mondiale dans le monde entier, y compris et surtout dans les chemins de fer américains[17], venait du Royaume-Uni, et cela a eu un puissant effet de développement pour l'économie mondiale dans son ensemble.

Enfin, le Royaume-Uni et le marché financier de Londres, en particulier, ont ancré le système monétaire international par le biais du étalon-or et par les fonctions que les banquiers londoniens ont exercées en prêtant de l'argent à différentes personnes et différentes entreprises dans le monde entier. Cela a permis de stabiliser les monnaies et de stabiliser les transactions commerciales.

Ce sont les origines de la première mondialisation ou les années du libéralisme classique.

Commerce

Le traité Cobden-Chevalier et les colonies

À quoi ressemblaient les relations économiques internationales entre l'abolition de la loi sur le maïs en 1846 et le traité de Versailles en 1919 ?

Jusqu'en 1880 environ, la politique du Royaume-Uni a entraîné un démantèlement progressif des protections. Le Royaume-Uni a commencé à libéraliser son commerce extérieur de manière unilatérale dans un premier temps, puis à signer des traités bilatéraux de libre-échange, notamment avec la France et le traité Cobden-Chevalier en 1860. Le traité a mis fin aux droits de douane sur les principaux produits commerciaux tels que le vin, le brandy et les articles en soie en provenance de France, et le charbon, le fer et les produits industriels en provenance de Grande-Bretagne. Les effets économiques ont été faibles, mais la nouvelle politique a été largement copiée dans toute l'Europe.[18]

Le traité Cobden-Chevalier est important parce que la France est la plus importante puissance continentale à ce moment-là. Avant l'unification de l'Allemagne, la France n'est toujours pas une puissance hégémonique sur le continent, mais une puissance dominante sur le continent. Ainsi, le fait que l'acteur dominant du système mondial, le Royaume-Uni, signe des accords de libre-échange avec la puissance régionale dominante en Europe continentale, qui est le centre du monde à l'époque, a eu un impact significatif sur le fonctionnement de l'économie mondiale à cette époque.

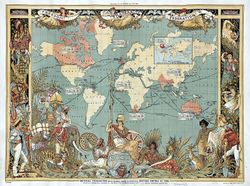

Un autre aspect critique de la libéralisation progressive des relations commerciales a été l'extension des possessions coloniales. Il est important de rappeler que le Royaume-Uni et la France, notamment, ont eu quelques colonies avant le XIXe siècle. Mais la propagation du colonialisme a lieu au cours du 19ème siècle. C'est important car les possessions coloniales se sont ouvertes à la zone de libre-échange.

Le Royaume-Uni et la France s'étaient convertis au libre-échange, et par la domination qu'ils exerçaient sur le plan politique par le biais de leurs possessions coloniales, ils ont ouvert les marchés du monde entier au libre-échange. Ils l'ont fait par l'intermédiaire de leurs dépendances et aussi par le libre-échange des anciennes colonies, notamment en Amérique latine, et en particulier en Argentine.

À l'époque, l'Argentine était un marché très important. L'Argentine était un État très important pour l'économie mondiale de l'âge d'or.[19] Elle était aussi riche que la France, plus riche que l'Italie et l'Allemagne. Dans les années 1870, les salaires réels en Argentine étaient d'environ 76% par rapport à la Grande-Bretagne, et sont passés à 96% dans la première décennie du XXe siècle.[20] Le PIB par habitant est passé de 35 % de la moyenne américaine en 1880 à environ 80 % en 1905,[21] similaire à celle de la France, de l'Allemagne et du Canada.[22][23]

L'exception : les États-Unis et l'Allemagne

Il y a deux grandes exceptions à cette règle.

La première est celle des États-Unis. À partir de Guerre de Sécession et tout au long du XIXe siècle et jusqu'au milieu des années 1930, les États-Unis ont été le pays le plus protectionniste. Son marché intérieur était pratiquement fermé aux intrants du Royaume-Uni. Cela a été rendu possible par la victoire du Nord sur le Sud pendant la guerre civile, car avant cela, les propriétaires terriens du Sud et les propriétaires d'esclaves étaient les principales forces politiques de libre-échange au sein des États-Unis.[24][25][26] La victoire des industriels du Nord et de la classe ouvrière industrielle pendant la guerre civile a ouvert la voie à la protection du marché intérieur et à la promotion et à la mise en œuvre de politiques de promotion industrielle infinies sur le plan du développement.[27]

La deuxième grande exception est l'Allemagne peu après l'unification, lorsque les propriétaires terriens représentés par les alliés de Bismarck avec les capitalistes montants, la bourgeoisie montante contre le SPD, contre le mouvement socialiste, contre la classe ouvrière ont mis en œuvre des politiques de protectionnisme généralisé.[28][29]En 1879, le Reichstag (sous la direction du chancelier Otto von Bismarck) a imposé des droits de douane sur les importations industrielles et agricoles dans l'Allemagne impériale.[30] Comme l'explique Asaf Zussman, les droits de douane ont été imposés sur une grande variété de produits industriels et agricoles, marquant ainsi un tournant dans l'histoire tarifaire européenne du XIXe siècle : les décennies précédentes ont été caractérisées par la libéralisation des échanges tandis que les décennies suivantes ont été marquées par un retour au protectionnisme en Europe continentale.[31][32]

La principale différence entre l'Allemagne et les États-Unis est que les propriétaires fonciers allemands sont protectionnistes. En revanche, les propriétaires fonciers des États-Unis sont favorables au libre-échange. Dans Commerce and Coalitions: How Trade Affects Domestic Political Alignments published in 1989, Ronald Rogowsky applique modèle Heckscher-Ohli à l'économie internationale pour montrer comment les coalitions entre les facteurs de production des classes se sont déroulées au cours du XIXe siècle et ont abouti aux trois résultats mentionnés précédemment : le libre-échange au Royaume-Uni et la protection aux États-Unis et en Allemagne.[33][34][35][36]

Tendances du commerce international

En ce qui concerne la dynamique globale du système, la part des exportations dans le monde a été choisie juste avant la Première Guerre mondiale en 1913. Bien que le ratio des exportations par rapport à la production mondiale ait chuté dans les années 1900, cette part augmente en 1913, moment où l'économie mondiale est la plus ouverte de l'ère classique.[37]

Malgré le fait que le XIXe siècle se soit terminé par un fort protectionnisme, le commerce entre les pays du monde entier connaît une croissance historique. La croissance annuelle est de 3,5% au cours du 19ème siècle contre 1% de 1500 à 1800. En conséquence, l'importance du commerce extérieur des pays par rapport à leurs économies augmente clairement, et ces économies sont de plus en plus ouvertes.

Les exportations représentaient 2 % du PNB en 1830, 9 % en 1860 et 14 % en 1913. L'ouverture de l'économie européenne s'accroît. L'expansion des échanges commerciaux touche les différents pays de manière inégale. Ces différences reflètent plusieurs facteurs, mais surtout la taille différente des économies. On le voit bien avec les États-Unis, car si on regarde le niveau des exportations, elles arrivent à peu près au même niveau en valeur absolue que celles de la Grande-Bretagne, mais ne représentent que 6 % du PIB alors qu'au Royaume-Uni on parle de 18 %.

L'importance du commerce du tiers monde augmente également. Si l'on regarde les estimations, la part des exportations entre 1830 et 1913 passe d'environ 2 % à 19 %.

Les pays européens dominent le commerce international des produits manufacturés. Plus généralement, la participation du pays au commerce international est étroitement liée à la structure de son économie. En fin de période, l'excédent des exportations est impressionnant pour la Grande-Bretagne alors que pour l'Amérique latine, c'est le contraire. Cette situation est typique car il s'agit d'une région qui a du mal à s'industrialiser.

Nous devons reconnaître qu'en dépit du fait que nous assistons à une intensification de l'industrialisation, lorsque nous examinons la répartition du commerce international dans le monde, même si ce commerce devient de plus en plus important, nous constatons que, malgré cela, le commerce international en termes de produit brut devient de plus en plus important. La Grande-Bretagne dépend d'autres pays pour ses produits bruts, l'ampleur du déficit augmente pendant cette période. Pour l'Amérique latine, la situation est différente.

Il y a des cas où il y a les deux à la fois avec des capacités de produits manufacturés et des ressources naturelles à exploiter.

Investissement

Comme indiqué précédemment, Londres a fourni des capitaux d'investissement pour des infrastructures dans le monde entier. Mais comment cela s'est-il produit ?

C'est très important, et c'est la question de la composition des investissements internationaux pendant l'âge d'or. La forme qu'ils ont prise était principalement des prêts bancaires pour les investissements dans les infrastructures et les activités d'extraction telles que l'exploitation minière et la production de matières premières.

Que très peu de sociétés multinationales qui existaient à l'époque étaient dans le secteur primaire dans les secteurs des mines et des matières premières et dans l'agriculture. Elles étaient organisées, et cela s'est passé le long de la structure hub and spokes de cette époque. Les pays avancés exportaient des capitaux vers les pays en développement, mais aussi vers les États-Unis, tandis que les pays moins développés exportaient des matières premières et des produits de base vers les pays avancés.

Jusqu'à la guerre civile, il est important de noter qu'un pays comme les États-Unis pouvait être considéré comme faisant partie du monde en développement. Pourquoi ? Parce que la façon dont il s'est inséré dans le capitalisme mondial était d'être l'un des pivots et des rayons, le cœur étant l'Angleterre, et la France dans une moindre mesure. Ainsi, avant la guerre civile, les États-Unis exportaient principalement des matières premières et du coton en particulier du Sud vers le Royaume-Uni et la France.

C'était un schéma qui prévalait à l'époque classique dans les relations entre l'Europe et l'Amérique latine, l'Asie et l'Afrique. C'était la structure de base des relations entre le monde avancé et le monde en développement, que ce dernier soit un État indépendant en Amérique latine ou des possessions coloniales en Afrique et en Asie.

Le régime international d'investissement était basé sur le colonialisme parce que le colonialisme fournissait un cadre juridique dans lequel les droits des investisseurs essentiellement anglais en Afrique, en Amérique latine, en Afrique et en Asie, et donc dans une moindre mesure les terres en Amérique, pouvaient être protégés. Le colonialisme était dans une certaine mesure une garantie légale que si vous étiez assis quelque part à Londres et que vous investissiez dans des obligations ou des actions en Afrique du Sud, vous étiez sûr que vos droits seraient protégés car le gouvernement de Sa Majesté s'en occupait.[38]

Il y a aussi la diffusion de la Common Law du Royaume-Uni comme principal cadre juridique qui a été utilisé pour organiser l'activité économique internationale.[39][40][41]

Le deuxième pilier était l'étalon-or. L'étalon-or est un système monétaire dans lequel la monnaie ou le papier-monnaie d'un pays a une valeur directement liée à l'or.[42] L'étalon-or a fonctionné comme un sceau d'approbation de bonne gestion, par lequel les investisseurs savaient que si un pays était attaché à l'étalon-or, il poursuivait des politiques microéconomiques qui protégeaient les intérêts des investisseurs.

C'est à partir de cet endroit de l'Atlantique Nord qu'une grande partie de l'économie mondiale était organisée. Par répercussion, le reste de l'économie mondiale était organisé autour de l'Empire britannique. Et bien sûr, la Chine était sous l'influence de puissances étrangères et, dans une large mesure, du Royaume-Uni.

Argent

How was the international monetary system organized?

À mesure que la Pax Britannica se répandait dans le monde, l'étalon monétaire utilisé au Royaume-Uni est devenu l'étalon monétaire du monde, à savoir l'étalon-or. Peu à peu, le monde a abandonné l'étalon argent ou étalon bimétallique, combinant deux étalons or et argent en établissant la parité entre les prix des deux métaux. Parfois, après 1870, l'étalon-or est plus ou moins devenu l'étalon monétaire international. C'est Bank Charter Act de 1844 au Royaume-Uni qui a officialisé l'adoption de l'étalon-or.[43] Cette loi, adoptée sous le gouvernement de Robert Peel, était une tentative pour limiter la forte croissance de la masse monétaire permise par la multiplication des banques dans les années 1830.[44][45] Le Bank Charter Act impose le principe de circulation sur le Royaume-Uni, confère à la Banque d'Angleterre le monopole de l'émission des billets de banque et l'oblige à détenir des réserves d'or égales à 100 % des billets émis.[46] C'est le triomphe de l'étalon-or.

Il est important de savoir que, tout comme aujourd'hui, le système monétaire international est basé sur le dollar et que, par conséquent, les marchés financiers de New York jouent un rôle dominant dans la régulation du fonctionnement du système. C'était la même chose à l'époque avec la City de Londres. Aujourd'hui, la City de Londres joue un rôle similaire à celui de New York, mais elle le fait en dollars et en livres sterling. Londres est une plaque tournante mondiale majeure pour la finance, mais elle est une plaque tournante pour la finance en dollars et non en livres sterling. D'une certaine manière, elle n'est pas une annexe de New York, mais elle joue un rôle similaire à celui de New York dans le système actuel.

À l'époque, la ville de Londres fournissait la monnaie de réserve internationale. Les gens savaient que, tout comme sous le système de Bretton Woods, Le dollar était aussi bon que l'or. À l'époque, ils savaient que la livre sterling était aussi bonne que l'or. Si vous déteniez des livres sterling et des biens en livres sterling, vous étiez sûr que leur valeur serait préservée. C'est pourquoi les banques centrales du monde entier, des investisseurs privés, étaient désireuses de détenir des livres sterling. La livre sterling est devenue la monnaie mondiale en quelque sorte, une monnaie de réserve internationale, et a fourni des liquidités pour stabiliser les systèmes monétaires internationaux pour les prêts bancaires organisés par la finance privée.

L'étalon-or était un sceau d'approbation de bonne gestion.[47] Car en théorie, l'étalon-or fonctionne de manière automatique. Si un pays enregistre un déficit commercial, c'est-à-dire qu'il importe plus qu'il n'exporte, il y a des sorties d'or. Il y avait une sortie nette d'or. Pourquoi ? Parce que les pays devaient payer leurs importations en or et que s'ils gagnaient autant d'or qu'ils devaient payer leurs entrées, il y avait une sortie nette d'or.[48]

Comme les prix et les salaires étaient liés à l'or, s'il y avait une sortie nette d'or, il y avait un effet déflationniste qui entraînait les prix et qui était juste à la baisse et qui conduisait à un processus automatique d'ajustement macroéconomique. Si les prix et les salaires, en particulier, diminuaient dans l'économie nationale qui enregistrait un déficit commercial, il était évident que le pouvoir d'achat de cette économie nationale baissait, diminuait et, par conséquent, le volume des intrants diminuait et s'équilibrait. Telle est la théorie. Ce n'était pas exactement comme cela, mais c'était une façon dominante de faire fonctionner l'économie internationale au niveau macroéconomique à l'époque.

Il est important de comprendre que cela signifiait que la stabilité extérieure et la stabilité monétaire sont soit liées entre les monnaies nationales et que la masse monétaire intérieure à l'or prévalait sur la primauté des considérations intérieures. Il n'était pas possible sous l'étalon-or de dire que vous vouliez refléter votre économie en augmentant les prix, en augmentant les dépenses alors que dans le même temps vous aviez un déficit commercial. Il était impossible de faire cela, ou il était nécessaire de quitter l'étalon-or. Et si un État ne voulait pas quitter l'étalon-or parce que l'étalon-or était la bonne gestion de l'approbation. Si un État faisait cela, alors les investissements étrangers en provenance du Royaume-Uni et de l'Europe cesseraient, et il y aurait eu un problème de financement des projets d'investissement, etc.

Jusqu'alors, les ajustements étaient entièrement nationaux. Ils étaient entièrement basés sur la déflation des prix et des salaires. Ainsi, il fallait une élasticité totale des prix dans les salaires.

La désintégration du capitalisme mondial dans l'entre-deux-guerres

L'hégémon absent

Commençons par les conditions géopolitiques et idéologiques. La transition entre les deux premières étapes du capitalisme mondial est principalement géopolitique avec le déclin de la Pax Britannica et l'absence, pendant la période de guerre intérieure, d'un remplaçant, d'un nouvel hégémon qui reprendrait le rôle joué par le Royaume-Uni à l'époque classique et la Pax Britannica. En d'autres termes, Pax Britannica n'était plus, mais Pax Americana n'était pas encore arrivé. C'est l'histoire de base. Et bien sûr, c'est la théorie développée par Charles Kindleberger dans son livre, et qui a donné l'impulsion au premier grand débat théorique en économie politique internationale dans les années 1970, à savoir la théorie de la stabilité hégémonique.

Le fait essentiel était que la politique étrangère américaine n'était pas encore totalement internationaliste et libérale. En outre, l'économie américaine était encore très repliée sur elle-même.[49] Jeffrey Frieden documente comment, pendant l'entre-deux-guerres, le secteur bancaire et financier américain ainsi que certains secteurs industriels à forte intensité de capital se sont tournés vers l'extérieur parce qu'ils avaient commencé à s'internationaliser et à générer d'importants bénéfices à l'étranger. Ils ont donc fourni la base de l'internationalisme libéral. Toutefois, leur poids dans l'économie nationale n'était pas encore assez dominant pour que la politique étrangère des États-Unis s'oriente résolument vers l'internationalisme libéral et s'éloigne du protectionnisme et de l'isolement.

Il est important de noter que dans l'histoire de la politique étrangère américaine, vous avez deux grandes étapes : le XIXe siècle et jusqu'à l'entre-deux-guerres, vous avez le protectionnisme et l'isolationnisme. Les États-Unis protègent les marchés systémiques et se tiennent à l'écart des affaires politiques du monde. Et puis à partir de l'entre-deux-guerres, l'Amérique est devenue une puissance mondialiste. Le 24 septembre 2019, Donald Trump a prononcé un discours aux Nations unies, et il a déclaré que les mondialistes ne vont pas façonner le 21e siècle, mais que les patriotes le feront.[50][51] He is trying to reverse the secular course of American policy. From the interwar period, America became a globalist power, a liberal internationalist power that promoted free trade in open global capitalism and at the same time, both became interventionists abroad.

The issue that crystallized this geopolitical dynamic was the ratification of the League of Nations treaty. The League of Nations was the project first and foremost of President Wilson, it was an American project. However, the treaty was negotiated, but the United States Senate refused to ratify the treaty. Therefore, the United States never took part in the look off.[52]

In terms of international economics, there was a gradual turn to protectionism in the 1920s under the Republican administrations.[53] It happened when the Republicans regained power after the war and restored the usual high rates, with the Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922.[54] So, until the 1940s, the Republican party was the party of protectionism and isolation, while the Democratic party was the party of free trade engaging with Europe. Before, the Republican Party was the party of the industrialists in the North. In contrast, the Democratic Party was the party of the slave owners in the South.

There was a turn to trade protectionism in the 1920s with a series of hikes in tariffs resulting in the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930.[55] This act is often referred to as being linked to the Great Depressi,on and it is true that this act plays a role in triggering reactions on the part of the United States' trading partners. The act raised US tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods.[56]

In terms of finance, the United States refused to play the role of lender of last resort to stabilise the international system by extending credit after 1929 when panic ensued after the Wall Street crash. The United States went off the gold standard in 1933 by giving primacy to domestic considerations. This was made through the Executive Order 6102 signed on April 5, 1933, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[57][58] Franklin D. Roosevelt, the President of that time, said so in so many words that crystallized isolationism in the 1930s. However, there has been a shift from the 1930s onwards towards liberal internationalism, but that shift did not culminate until the Marshall Plan in 1945.

In terms of ideology, the interwar period sees the decline of free trade and liberal economic doctrines and the associated rise of Keynesianism in terms of macroeconomic management, the idea that you cannot allow the macroeconomy to operate automatically as the gold standard prescribed. The idea of the welfare state is that there had to be some way of securing the incomes of workers. Along with the welfare state comes the idea of collective bargaining recognition of unions to set a floor below which wages cannot fall, and state interventionism in macroeconomic policies of the state taking over corporations regulating economic activity.

In terms of foreign economic policy, there is the rise of economic nationalism that in some cases assumes the form of economic autarky in particular in Nazi Germany, but also in the Soviet Union. In other cases, such as in the case of the United Kingdom, it assumes the form of imperial trade preferences and imperial protectionism within the British Empire. In contrast, before, the British Empire was opened to the trade of the world. From 1932, it ceases to be so.

Keynes wrote two pamphlets that marked the period namely A Revision of the Treaty in 1922 to advocate a reduction of German reparations and in A Tract on Monetary Reform published in 1823 he denounces the post-World War I deflation policies.[59] One was a critique of the Versailles Treaty and the way that the Allies tried to settle the issue and the other one is this critique of the attempt by the United Kingdom government to go back onto gold in 1925 by applying a deflationary policy.

Trend in protectionism in the 1920s and 1930s

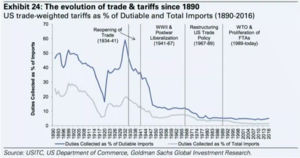

There is a trend of protectionism in the 1920s, and it culminates in the early 1930s leading to a general turn into economic nationalism and autarky. The key date to remember is the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, formally United States Tariff Act of 1930, a law that implemented protectionist trade policies in the United States.

It is possible to see the spike in the tariff level in the United States that’s the highest point of protectionism in the United States history, and it happened in 1930. It reversed in 1934, but 1930 is the culmination of American protectionism.

The imperial preference system set up by the United Kingdom in 1932 at the Commonwealth Conference on Economic Consultation and Co-operation held in Ottawa whereby the dominions and colonial possessions agree to raise tariffs for inputs from outside the British Empire.[60][61] It was considered as a method of promoting unity within the British Empire and sustaining Britain's position as a global power as a response to increased competition from the protectionist of Germany and United States.[62][63] Thus, the United Kingdom is promoting an inward-looking trading block centred around the Empire. France also turns towards its empire, which is much smaller and so it is less of a problem.

There are German and Japanese attempts to form close regional trade blocks in the 1930s. That begins before Hitler takes power in 1933 with an attempt in 1931 to form a customs union between Germany and Austria.[64] It took also other forms, such as attempting to form preferential trade agreements with states in Eastern Europe as with the Schacht Agreements.[65][66][67][68][69] Japan tries to set up the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It was an attempt initiated during the Shōwa era to create, for the benefit of the Empire of Japan, a self-sufficient bloc of Asian countries led by Japan and not dependent on Western countries. Japan invaded China in 1937, takes over the Philippines, and attempts to proceed in the same way as Nazi Germany, but in the East Asian economy.[70]

The Soviet Union turned toward self-sufficiency after Stalin decided to abandon the New Economic Policy in 1928. The USSR was rushing toward a degree of economic isolation unparalleled by any industrial ecnocy at peace.[71] According to Dohan, the motive for autarky most frequently cited by Western observers is Soviet fear of capitalist aggression, both military and economic.[72] But it can also be cited the other causes for the decline in Soviet trade such as Stalin's xenophobia and distaste for the uncontrollability of the foreign sector, effects of the world depression, and systemic characteristics of a Soviet-type economy which hinder the coordination of a highly variable foreign trade sector with a central plan. However, for Dohan, these explanations although insightful are not sufficient. The collapse of Soviet foreign trade in the 1930s had its roots in the pre-World War I structure of the Russian economy and foreign trade sector.[73] The USSR was probably the most closed of these national economies in the 1930s and the 1940s.[74][75]

Then Latin America, in particular, Argentina abandoned free trade in the 1930s. trade openness significantly declined during the 1930s while Argentina showed high openness ratios ranging from 30 to 40 per cent during the first globalization era.[76] Until the 1930s, the economy of Argentina and other Latin american countries were centred on the export of raw materials and the dominance of landowners over capital and the working class. This can be explained as following the 1929 crisis, raw materials prices collapsed while the prices of manufactured imports do not falling.[77]

If one were to determine the point at which this dynamic was reversed, one would have to choose the Reciprocal Tariff Act of 1934 that authorizes the American president to pass trade agreements with other nations, particularly Latin American countries, without ratification by Congress.[78][79][80][81][82] From that point onwards, the American president becomes a bastion of free trade as opposed to the more protectionist-inclined Congress. American industry also becomes much more internationalized and abandoned the traditional policy of protectionism and isolationism. The Republican Party from the late 1930s onwards started to advocate liberal internationalism, culminating with the administration of Dwight Eisenhower in the 1950s.[83][84]

A new pattern of international investment

This period is the beginning of a major shift in the way the international economy operates. That is the most important fact that distinguishes what happens after the Second World War with what happened in the classical era before the First World War.

That is when American corporations begin to invest for production abroad. There is a new pattern of international investment. It doesn’t happen within the hub and spoke structure, and it is no longer North-South. It is no longer developed countries exporting manufactured goods and importing raw material from the south. It takes more the form of North-North foreign direct investment within the same sectors of activity in particular industrial sectors.

Bank loans as a share of international investment decline and foreign direct investment (FDI) operate themselves. Economic operations abroad take over. That is the beginning of multinational enterprise as we know it today.[85] Before, in the classical era, there were no multinational enterprises in the form that we know them today.

In the case of Europe that sparks. It took of commercial invasion of Europe and stimulated the surge for a large unified market with Europe to rival the size of the American and imitate the size of American corporations. That is where the beginnings of the idea of European unification come from. While looking at the history of Europeanism and ideologies in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s, it is clearly a reaction to American economic dominance, and American economic dominance and advance are perceived as a function of the size of the American domestic market. The idea is that Europe has to have the same domestic market as the United States or at least equal to that of the United States to be able to develop large corporations, just like the American had done. Similarly, Japan attempts to broaden its domestic market through the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (GEACPS).

In less developed countries, there is a decoupling that initiates from global capitalism. There was an inward turn because of the degradation in terms of trade which initiated a wave of expropriations of foreign multinational corporations in particular in the oil sector.

The oil sector was the sector that typified the hub and spoke structure of international investment and international production. The key date characterizing that turn towards expropriating for investment is the Mexican oil expropriation of 1938 that created the national oil corporation Pemex in Mexico and then was followed in particular by Saudi Aramco.

The end of Gold Standard

The gold standard broke down in 1914 and countries, including the United Kingdom, started issuing fiat currencies.[86] What are fiat currencies? Fiat currencies are what you have in your pockets today, namely paper money. It is a currency without intrinsic value that has been established as money, often by government regulation.[87] That value is not fixed to a metallic standard or to precious metal. Its value depends on the money supply, on the volume of money, and that is a decision of the central banks.

Central banks now can decide the value of a currency interactively, and that is the question of monetary policy related to inflation. It is what happened during the First World War to facilitate war finance.

From 1919 onward there was an attempt to restore some the gold standard. The major problem here is that for the United Kingdom it would result in deflating its domestic economy, make the British pound too strong for effective exporting, and pushdown wages. With policies associated with Winston Churchill, the standard was reinstated in 1925.[88] Ten months later the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) called a general strike in the United Kingdom that lasted nine days, from 3 May 1926 to 12 May 1926, and the attempt goes down the drain. There is a general strike because workers did not want to take deflation, lengthening the workday and reducing wages. So the gold standard is history because of the general strike in the United Kingdom in the 1920s.

A new reality emerged, which is that external monetary stability will no longer prevail over domestic economic considerations and policies. There has to be some accommodation between external constraints and domestic imperatives.

The basic political fact behind that is the rise of the labour and the socialist movement which led to wage rigidity and the end of perfectly elastic wages. Because workers are now organized, they can organize and strike to resist pay cuts. Therefore, it is no longer possible to have a monetary system that works automatically by deflating prices and wages.

In practice, the gold standard was over in 1926. Formally it ended in 1930 when the United Kingdom abandoned the gold standard in 1931 under a Labour government.[89][90] It led to a sharp devaluation in sterling and helped the United Kingdom to recover from the crisis.[91]

In 1933, in the middle of the London Economic Conference that attempts to rebuild international monetary cooperation and win agreement on measures to fight the Great Depression, Roosevelt announced that the United States will not support the Conference agenda as outlined.[93][94] Roosevelt did not want to tie his hands by tying the value of the dollar to gold to allow the external value of the Dollar and the exchange rate to float according to the vagaries of his domestic economies.

That corresponds to the collapse of the international trading system in the early 1930s. There is one date that marks the reversal of that trend. It is 1936 and the Tripartite Agreement of 1936 between the United States, the United Kingdom and France. Subscribing nations agreed to refrain from competitive depreciation to maintain currency values at existing levels, as long as that attempt did not interfere seriously with internal prosperity.[95] That is the first attempt to restore some kind of international monetary system based on active cooperation between central banks. Central banks from now pledge to help each other, counteract outflows of gold and money in order to stabilize exchange rates between the major currencies that make up the world economy. The agreement stabilized exchange rates, ending the currency war of 1931 - 1936, but failed to help the recovery of world trade.[96]

The postwar economic order: Embedded Liberalism

The third stage in the history of global capitalism is the stage called Embedded liberalism. The concept of embedded liberalism was introduced by John Ruggie in this article International regimes, transactions, and change: embedded liberalism in the postwar economic order published in 1982.[97] According to Ruggie, embedded liberalism is a commitment to a new kind of liberal multilateralism compatible with 'domestic interventionism' aiming at supporting domestic social security and economic stability within Western industrialized countries.[98] Embedded liberalism is a term designed to convey the fact that the operating principle of this stage of global capitalism was a way to accommodate the imperative of external stability and the imperative of domestic policy autonomy.[99]

The advent of Pax Americana

The major shift takes place after 1947 with the advent of the Pax Americana and the replacement of the previous hegemon before the First World War, Pax Britannica.

During the second half of the 1930s and the 1940s, liberal internationalism prevails over isolationism and protectionism in the United States. Just at the same time as in the 1930s, American industry turned to free trade, converts to free trade, and the Republican Party gradually also became a pro-free-trade position.

Why is it so?

Because during the Second World War, most of the sectors in the American economy internationalized developping activities with important sources of profit abroad. Therefore there is a stake in the way the international economy works, and sectors want the American state to play a stabilizing role in order to safeguard their investments and markets abroad.

The United States promotes multilateral liberalization in trade and financial flows. It keeps its domestic market open for its allies, and that is a significant feature of the few decades following the end of the Second World War. The United States notably becomes a source of international investment for construction in particular in the late 1940s and the early 1950s operating also in Europe, Japan and Korea. It stabilizes the international economic system by providing finance and creates space by doing so to reconcile external imperatives and domestic policy autonomy across the world.

The Second and Third Worlds

But just as the United States is doing, there are vast chunks of the world that stand aside. Those are the so-called second and third worlds. The second world is the world under the domination of the USSR and China after 1949. The Third World is the former colonial world that will, later on, give rise to the non-aligned movement and the Group of 77 (G77) in the United Nations.

Those states pursue inward-oriented industrialization and development. In the case of Latin America and Asia and particular India that takes the name of Import substitution industrialization (ISI).[100][101][102]

To a large extent, ideologically, this is a return to prescriptions that derived from mercantilist thought, in particular from the thinking of economic nationalists like Alexander Hamilton and Frederick List.[103][104]

The idea is that to develop industrial capacities and technological capacities, a country has to see a lot of itself from the world economy. In order to keep out the imports of more advanced countries that prevent its own industry from acquiring those capacities and developing its own economies of scale, the country has to reserve the domestic market to its own industrial firms. It is, therefore, necessary for them to replace these imports with domestic production to gaining their independence. They do so notably by placing high tariffs on imports and by implementing protectionist and inward-looking trade policies. For those countries, it is an attempt to reduce foreign dependency through local production of industrialized products, whether through national or foreign investment, for domestic or foreign consumption.

In those cases in the Second and the Third worlds, the shift towards neo-economic nationalism goes hand in hand with the political victory of urban classes, industrial capital, intellectuals the industrial working classes over landowners. Those were the forces that dominated Latin America before the 1930s, and those were no longer the forces that dominated Latin America after the 19th. The same goes before India.

Multilateral trade liberalization

Multilarization

How did multilateralization in trade play out?

The United States promoted the setting up of international organizations to promote multilateral trade liberalization. The original idea was to have an International Trade Organization. A treaty began to be negotiated. It is in this context that, in 1948, the Havana Charter attempted to establish international rules to regulate and facilitate trade between the various signatory countries. But it filtered in 1948 because the United States Senate refused to ratify the Charter of the International Trade Organization.[105][106][107][108][109] In order to understand the reason for this refusal, it is necessary to see that the Havana Charter provides for an organisation fully affiliated to the United Nations. However, the United Nations has a court of justice: the International Court of Justice sits in The Hague replacing the Permanent Court of International Justice of the League of Nations in 1946. The United States, the world's largest economic power at the time, did not want to be under the binding authority of international court judges who would take over the affairs of states.[110] In the absence of an international trade organization to coordinate their commercial policies and deal with problems related to their trade relations, countries will turn from the early 1950s to the only established multilateral international trading institution: the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). It highlights the continuing influence of protectionist and isolationist currents within the United States even if declining. The United States ratifies the United Nations Charter, ratifies the International Monetary Fund Charter, and the World Bank charter. In this regard, the case of the International Trade Organization is an isolated victory for the protectionists.

At the same time as the International Trade Organization fails, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) takes shape. It is not a formal organization, it does not have formal rules, it does not have arbitration panels, it does not have all sorts of instruments standing to some limited extent above the sovereignty of national states. It is a forum for multilateral negotiation where liberalization takes place. As per its preamble, its purpose is the "substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the elimination of preferences, on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis." It is the answer to the World Trade Organization (WTO), which is the ITO reason from its ashes and set up in 1995. And within GATTS are organized a series of rounds of trade liberalization.[111][112]

The reasons why those negotiations are successful is that negotiations in the 1950s the 1960s and even the 1970s are mostly between the United States and Western Europe and to a lesser extent Japan. In particular, after the treaty of Rome comes into effect in 1958, those negotiations until the Uruguay round are mostly a match between Washington and Brussels.

Multilateral trade liberalization is organized along a set of norms and rules that are set to guide the way in which international trade corporation is to take place. There is gradually liberalization. The United States does not push for a total elimination of tariffs and other barriers to trade. However, it promotes a gradual liberalization because it recognizes that to abruptly liberalization can stimulate resistance to trade.

An important principle is the pne of non-discrimination with the most favorite nation rule by which each signatory state undertakes to grant to the other any advantage that it would grant to a third state.[113] In the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements, the most-favoured-nation (MFN) clause states that any trade advantage granted by one country to another must be immediately extended to all WTO members. It is the idea, for example, that if the United States lowers tariffs for the United Kingdom for inputs, it has to do the same across the board for all other trading partners in the system. Therefore, it is the idea that there has to be liberalization across the board and not simply preferential trade liberalization. With this principle, what is given to one is given to all without discrimination.

Preferential Trade Agreements

There are several safeguards against the stabilizing effects of trade liberalization. The norms of the system allow countries to reinstate barriers to trade, to close up their economies temporarily if the effects of liberalisation result in political and economic destabilization.

That is the theory, in practice, things fold out differently. Why is that so?

That is mainly because the most important trade liberalisation effort during the Embedded Liberalism stage is preferential in nature and not multilateral. That is, for example, the setting of the European customs union progressively in the 1950s and the 1960s which is also the origin of the European Union of today.

It is important to realize that the setting of the customs union in Europe in 1957 goes against the spirit of the rules of the system. Because it is a preferential trade agreement, it is a preferential liberalization creating trade diversion and to the detriment of American exporters. American opposed the European customs union because they know that they are going to lose out. However, the United States allows and promotes that kind of liberalization because it sees liberalization of trade within Europe as a key plunk very construction of the Western European economy. That takes precedence over multilateral liberalization.

Most importantly, the customs union in Europe sets a precedent for what is going to come in the next stage, namely from the early 1980s a wave of preferential trade agreements. That becomes much more important in terms of the volume of world trade that what multilateral liberalization will be.

In a way, the system promotes one thing in theory, and, in practice, does something different.

Structural investments and multinational enterprises

Structural investments

There are two aspects to this. One is the way infrastructural investment in the developing world is going to be financed from now. It is no longer done through private funds and bank lending done from London and New York. It is to be done by public credits extended by international organizations or the United States Treasury. That is the origins of the World Bank Group (WBG) composed by five members institutions which are the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The first two are sometimes collectively referred to as the World Bank.[114]

The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) was precisely established in 1944 to offers loans and finance infrastructure projects in middle-income developing countries such as Africa, Latin America and Asia. Along with that, there are American initiatives for reconstruction in Western Europe and Japan. That is the Marshall Plan and its Japanese equivalent introduced in 1947. A functional equivalent to those plans is the boost to the Korean economy that comes out of wars spending during the Korean War in the Korean Peninsula in the 1950s.

To a large extent, the origins of what later on was to be called the Western European economic miracle, the Japanese Economic Miracle, and the Korean Economic Miracle have to do with the fact that early on the American government decided to fund major investments in infrastructure in those countries to provide them with a platform on the basis of which economic development was going to take place in its allies.[115][116][117]

Multinational enterprises

The other important trend is the culmination of the shift away from the hub and spoke structure of the Classical Era towards the years of multinational enterprises. That is a trend that began in the 1920s with American corporations investing in Europe and to a much lesser extent in Japan, but mostly Europe.

That trend comes mature during the 1950s and 1970s. There is a pattern for interactive investments in which investments between developed countries largely dominate in terms of the volume of investment and takes place in global countries. Between 85% to 90% of foreign investments during the Embedded Liberalism period are done between developed economies and no longer between North and South, no longer between advanced and developing countries.

For instance, American car manufacturers invest in Europe and European car manufacturers a bit later begin investing in the United States. So it is a deeper form of economic integration than integration that takes place through trade. It has a major impact in the 1970s, from the 1970s onwards in terms of the resistance of the global economy too. Nevertheless, it is a fundamental shift. It is the most important developed shift change in the way global capitalism operates during the 20th century.

There is an exception to this trend. The Second and Third worlds shun incoming for indirect investment from the United States, Europe and Japan.

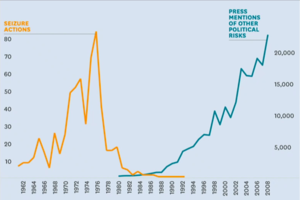

If you look at the chart for expropriations of foreign companies, they pick in the 1970s because it is the time when the attempt to take over for investments is at its highest and so the equivalent attempt to keep out for investment is also at its pick.

Bretton Woods and the International Monetary Fund

That is probably the most well-known feature of in Embedded Liberalism because the pre-war international monetary system was thrashed out at the Bretton Woods Conference that took place at the Mount Washington Hotel in New Hampshire in the United States between July 1 to 22 in 1944, so just before the war ended. It embodied a consensus between American and United Kingdom policymakers in the persons of John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White for the United States.

On the need to reconcile the drive for the liberal global financial system, but also domestic policy autonomy, Keynes and White disagreed on the details and in particular on how much the hegemon would have to do to stabilize the system. Keynes wanted the hegemon to do everything it could to stabilize the system by providing liberal countervailing finance to countries whose money was not the dollar. White was not very keen on that and wanted to limit the extent to which the United States would have to intervene. He wanted to limit the extent to which the international regime would force the United States to intervene in cases of financial destabilization and financial crisis.

The international monetary system created through Bretton Woods was a revised form of the gold standard in that the dollar's value to gold was fixed and the value of all other currencies was fixed to the dollar. It was a system where the dollar was as good as gold, and by extension, countries did not have to hold gold, it was enough for them to hold dollar to know that they had stability. But obviously, that held as long as the dollar's value was packed to the gold and had an anchor and it wasn't allowed to freely float up and down as it will happen from the 1970s.

There were fixed rates between national currencies, but they were adjustable. That is another major difference with the classical gold standard. It is that countries agreed that within the International Monetary Fund (IMF), they could negotiate between themselves the adjustment of exchange rate values to facilitate adjustment of the domestic economies through the exchange rate.

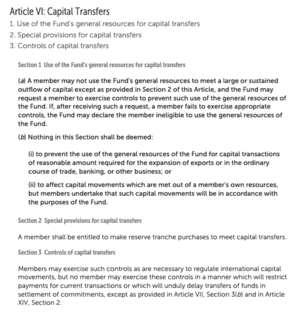

Another major feature was countervailing finance. The idea that if there was an outflow of capital in countries that suffered a dollar shortage, the IMF and the United States Treasury would provide dollars to the country experiencing the capital outflow in order to neutralize the effect of the capital outflow. In a way, the United States Treasury was pledging to fight speculators by annulling the effect of capital outflow in particular from Western Europe.

The third major feature was capital control.[118][119][120] It is the idea that countries could just refuse to accept capital outflows, and they could simply tell the speculators that their money was captive and would not continue to be held in the domestic banks. It was an administrative block to the free movement of capital across.[121][122] Types of capital controls include exchange controls that prevent or limit the purchase and sale of a national currency at the market rate, caps on the volume of permitted international sales or purchases of various financial assets, transaction taxes, or even limits on the amount of money a private citizen is allowed to take out of the country.

Keynes maintained that capital control was an essential feature of the system to be held in place for as long as necessary in order to stabilize international monetary systems. Probably capital control is the key feature that characterizes Embedded Liberalism, the fact that you both had a gold standard and at the same time you had capital controls.

The International Monetary Fund embodies these set of rules, and New York became the centre of international finance.

This stage broke ended in the 1970s ushering into the stage of the second globalization which is still underway.

The Second Globalization

Geopolitical developements

The same developments that were at the basis of the development of international political economy as an academic discipline were also at the basis of the birth of the liberalism stage and the beginning of the second globalization namely the relative decline of American hegemony in the 1970s.

Apart from the United Kingdom, most other major economies in the world economy grew more quickly than the United States in the 1950s and in the 1960s. From a situation where the United States’s share of industrial production was around 50% at the end of the Second World War, that came down to about 30% in the 1970s. On the opposite, the share of industrial production of Western Europe and Japan went up by a lot, in particular in the cases of Germany and Japan the major antagonists of the Second World War.

The fact that crystallized the relative decline of American hegemony was the crisis of the dollar that began sometime in the 1960s culminated in 1968 and 1971 and became an open feature of the global economy in the 1970s with the policy of the American administration of letting the dollar float and letting it depreciate that became known as the B9 neglect on the part of the American administration.[123][124]

At the outset, many people said that American hegemony itself was over. It has been the first major theoretical debate in international political economy.[125] International political economy itself is to begin with a discipline that emerged as a debate about the future of American hegemony. Today, there is a debate about the future of the distribution of power in the global economic system.[126] Some authors debate the extent to which China is threatening American hegemony, and some authors used to debate in the early 2000s the extent of which the emergence of the European Union was a challenge to American hegemony.[127][128] In the field of international political economy today, there is no debate over that most academics take it for granted that American hegemony has declined to some extent, but it is still very much around.

There was also the idea that the United States was losing ground and very quickly the very opposite happened as a result of the collapse of the USSR in the 1990s. During the same time in the 1970s and the 1980s, the Second and Third worlds opened up and decided to reintegrate global capitalism.

In the 1990s, after the second and third worlds stopped pretending to pose a challenge to the American economy, reintegrated fully the global economy dominated by the United States. There was a lot of talks about the American unipolar moment, a moment of unprecedented dominance by one single grade power of the global system.[129]

Another feature of the geopolitical picture that is important is the rise of China. And again, the rise of China begins with a realignment of China away from the Communist world and towards the United States with the famous [130] and the opening up of the Chinese economy to inward investments under Deng Xiaoping in 1979.[131] That initial stage of the rise of China is synonymous with alignment with the United States.[132]

That lasts more or less until the early 2000s. From the early 2000s, there are growing discussions about how China poses a challenge to the United States, and there is debate within the United States about revising its China policy from the quality of cooperation promotion shifting towards the quality of containment.[133] To a large extent it remains the main debate about the future of global capitalism today.

Ideologically, Keynesianism is on the decline from the 1970s onwards because it is accused of fostering inflation and because a greater proportion of domestic electorates become inflation adverse. Before, under the gold standard, it was mostly investors and wealth-holders that were averse to inflation and were also the first sections of the electorate. After suffrage became the norm in the first half of the 20th century that change, and moreover because the vast majority of people before the Second World War had a lower stake in the fight against inflation or state because they did not have financial assets.

That changes to a large extent after the 1950s because a good share of the working class develops savings of its own and so the share of the total population that has a stake in low inflation goes up. In this regard, the importance of fighting inflation becomes more important.

Along with the relative decline of Keynesianism ideology, there is the rise of what many people call neoliberalism or the Washington Consensus as it was coined by John Williamson, an economist in 1990 describing policy reforms that the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and U.S. Treasury advocated for emerging-market economies.[135][136][137][138][139] According to Williamson it "refer to the lowest common denominator of policy advice being addressed by the Washington-based institutions to Latin American countries as of 1989.”[140] It is a set of broadly free-market economic ideas with the dominant view of that the economy has to be privatized, has to be deregulated and has to be opened up to international. Williamson identified ten principles which are:[141]

- Low government borrowing. Avoidance of large fiscal deficits relative to GDP;

- Redirection of public spending from subsidies (“especially indiscriminate subsidies”) toward broad-based provision of key pro-growth, pro-poor services like primary education, primary health care and infrastructure investment;

- Tax reform, broadening the tax base and adopting moderate marginal tax rates;

- Interest rates that are market determined and positive (but moderate) in real terms;

- Competitive exchange rates;

- Trade liberalization: liberalization of imports, with particular emphasis on elimination of quantitative restrictions (licensing, etc.); any trade protection to be provided by low and relatively uniform tariffs;

- Liberalization of inward foreign direct investment;

- Privatization of state enterprises;

- Deregulation: abolition of regulations that impede market entry or restrict competition, except for those justified on safety, environmental and consumer protection grounds, and prudential oversight of financial institutions;

- Legal security for property rights.

Global trade liberalization: from multilateral trade liberalization to new regionalism

How does that play out in terms of the international trade system?

There is a wave of protectionism called New Protectionism in the late 1970s.[142][143][144] At the time, one of the major debates in international political economy is the fracturing of the world global capitalism as it did during the interwar period.

However, this time it does not. Helen Milner explores this topic in her article published in 1988 Trading Places: Industries for Free Trade.[145] And why doesn't that happen? It does not happen because of the rise of multinational production, the rise of multinational enterprises.[146][147][148][149][150]

Justice and cooperation have begun to spread across state borders. Firms have begun to have to earn a major share of the profits abroad either through export or production abroad itself. Therefore they have begun to conduct what economists called intra-firm trade which corresponds to international flows of goods and services between parent companies and their affiliates or among these affiliates. Thus, intra-firm trade arises only when firms invest abroad.[151][152] Because companies do that and they do that because it is more efficient to produce things now that way, they do not want protectionist barriers to go up because that would have as consequence to interfere with their intra-firm trade and will raise costs and to manage profitability.

The 1970s see a lot of trade liberalization. There is a new GATT round, the Tokyo Round that lasted from 1973 to 1979 and involved 102 countries with the aim to progressively reduce tariffs.[153][154][155][156][157] The share of exports in international trade grows more quickly than the international economy does, so the share of international trade in international economic activity goes up. The new protectionism is a dog that does not bark.

Liberalization is also spurred by the fact that less developed countries abandoned input substitution industrialization. This happens first in Eastern Europe opening up gradually most importantly in Poland and Hungary. It is also the case for Latin America who starts importing capital from abroad to fund the growing share of inputs in its economy who therefore turns towards the global market.[158]

The way trade liberalization is going to deepen during the stage of the second globalization is not through multilateral trade liberalisation. It's not mostly through multilateral trade liberalization, but through the new regionalism with the spread of preferential trade agreements, just as the customs union was set up in Western Europe in 1957.

Back row, left to right: Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, U.S. President George H. W. Bush, and Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, at the initialing of the draft North American Free Trade Agreement in October 1992. In front are Mexican Secretary of Commerce and Industrial Development Jaime Serra Puche, United States Trade Representative Carla Hills, and Canadian Minister of International Trade Michael Wilson.

Singapore Declaration Of 1992 Singapore, 28 January 1992. Source

Importantly the United States itself turns towards preferential trade agreement in the early 1980s. Until the late 1970s, the United States itself refused to enter into preferential trade agreements with countries because it did not want to undermine the norms and rules of the international trading system that it had promoted.

From the 1980s onwards as the international position of American industry comes under threat from the Japanese and the Western European challenge, the United States shift gear and adopting regionalism itself. There is a series of agreements that lead up to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The first one is the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement in 1988 that is joined by Mexico in 1992 after Mexico opens up during the 1980s.[159][160][161][162] On January 1, 1994, NAFTA enters into force. It's the opposite of the Spirit of multinational trade liberalization promoted by America in the 1940s and the 1950s.[163][164][165]

On 26 March 1991 Mercosur is created by the Treaty of Asunción, which establishes: "The free movement of goods, services and productive factors between countries in the establishment of a common external arsenal and the adoption of a common commercial policy, the coordination of macroeconomic and sectoral policies between States and the harmonization of legislation in order to achieve a strengthening of the integration process". Mercosur's purpose is to promote free trade and the fluid movement of goods, people, and currency. At the same time, the deepening of the European Union and the debate about the rise of Fortress Europe, which is the fact that as Europe is gradually coming closer together, is going to be detrimental to American export to the European market.[166]

Japan pursues its own network of preferential trade agreements that mostly are done bilaterally instead of bringing its trade partners into a block.[167] Japan signs a series of treaties with individual countries in the East Asian basin mainly with countres of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).[168][169][170][171][172]

On 28 January 1992 is signed in Singapore the AFTA agreement which gives birth to the ASEAN Free Trade Area.[173] ASEAN is one of the largest and most important free trade areas (FTA) trade bloc agreement supporting local trade and manufacturing, and facilitating economic integration with regional and international partners. It is a bloc of developing countries in the Southeast Asian region which notably includes Thailand, Malaysia, Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines that are high-growth economies of the 1990S as Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The global trade system is characterized by competitive liberalisation. That is a term coin by an economist called Fred Bergsten that was very influential in Washington in the international trading policy.[174][175][176] The difference here is that even if there is a competition just as there was a competition in the interwar period; this time, competition does not spur economic nationalism and an inward trend but competitive liberalization. The major powers such as the European Union, Japan, the United States and also China compete with each other for preferential access to third markets so that their own multinationals can better position themselves in the global competitive struggle that takes place.

Another feature of the trading regime that it takes the shape of deep liberalization. That often comes along with bilateral investment treaties. It is no longer just about tariffs. It is also about so-called non-tariff barriers. Why? Because trade is coupled as it wasn't before with production. Therefore, it's important for multinationals to know that not simply will they be able to import and export out of given market commodities but also that they can organize production within those markets without fear of interference from the local government with their property rights.

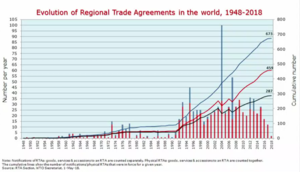

This chart shows the evolution of trade agreement in the world. It is possible to see the tremendous spike in the number of such agreements from 1991 onwards. This is the kind of thing that the GATT and later on the WTO were sets up to prevent. That's the key thing.

Investment Liberalization and Economic Development: the role of bilateral investment treaties

Commençons par la concurrence pour attirer les capitaux. L'abandon de l'industrialisation par substitution d'intrants signifie que la source des investissements industriels pour les pays en développement devient désormais le marché mondial et non plus l'économie nationale. Les pays en développement doivent désormais se faire concurrence pour attirer les capitaux, comme ils le faisaient à l'époque de l'étalon-or et à l'époque classique pour attirer les capitaux.

Cette fois-ci, la situation est cependant différente, car ils sont désormais en concurrence pour attirer les investissements industriels, les entreprises multinationales du secteur manufacturier, dans les secteurs des hautes technologies ; ces entreprises produisent donc leurs biens sur les marchés en développement et non plus sur les marchés avancés.

C'est la politique qui consiste à créer des zones économiques spéciales en Chine, au Mexique, dans les maquiladoras, en Asie du Sud-Est et à accorder un traitement fiscal préférentiel aux entreprises multinationales, etc.

Tout cela prend la forme de traités bilatéraux d'investissement (TBI) qui sont pour la plupart signés entre les pays qui sont à l'origine des investissements multinationaux : les États-Unis, l'Union européenne, le Japon et la Chine croissante, ainsi que les pays qui souhaitent importer des capitaux.[177][178][179][180] Those countries sign bilateral investment treaties in the same way that in the classical era they adopted the gold standard. There is a good housekeeping silver approval as a guarantee to foreign investors: if they bring their money into the host country, their investment will be protected.

A big push in that direction came in the late 1970s and the 1980s with Latin America and Eastern European countries, and then in the 1990s again, there was a big push into Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse USSR.[181][182]

Along with that comes to decline and the disappearance of expropriations of multinational enterprises in the least developed countries (LDCs).

From the late 1980s onwards the number of IIAs has soared. Mostly during the 90s because the 90s were the main time when countries were competing to attract capital. The last thing consequence of this is that there is now a web of legal arrangements Not multilateral but preferential legal arrangements that protect the rights of investors across the globe.

From the point of view of international investors, BITs are the functional equivalent of colonialism.[183] It is not to say that the system is neocolonial, it is just as colonialism in the past was there to safeguard the property rights of investors from the advanced world. Today, bilateral investment treaties play the same role.[184]

From Bretton Woods to ad hoc cooperation

The Bretton Woods system collapsed; the revised gold dollar standard collapse is 1968-71. Why 1968-1971? Because in the late 1960s, it becomes obvious that the stock of dollars held abroad is greater than the stock of gold held in the United States.[185][186][187] Therefore, if all of the holders of dollar assets abroad attempt to redeem their holdings for gold, the United States goes bust.[188][189][190]

In May 1971, West Germany left the Bretton Woods system, unwilling to revalue the Deutsche Mark.[191] In the following three months, this move strengthened its economy. Simultaneously, the dollar dropped 7.5% against the Deutsche Mark.[191] Other nations began to demand redemption of their dollars for gold. Switzerland redeemed $50 million in July.[191] France acquired $191 million in gold.[191][192] On August 5, 1971, the United States Congress released a report recommending devaluation of the dollar, in an effort to protect the dollar against "foreign price-gougers".[191][193][194] On August 9, 1971, as the dollar dropped in value against European currencies, Switzerland left the Bretton Woods system.[191] The pressure began to intensify on the United States to leave Bretton Woods.[195] No one is talking about a gold standard except some libertarians in the fringes of the Republican party in the US are talking about a gold standard today.

What happens is that the dealing of the dollar from the gold, actually reinforced the position of the dollar in the international monetary system. The dollar was as good as gold before. But now the dollar is as good as the dollar. IT means that because the dollar is so important international economic transactions, the United States enjoys an exorbitant privilege in the sense that it can print dollars and pay for whatever it needs to import and suffers no consequences.

The United States is today the only country in the world for which there is no contradiction between external stability and domestic autonomy. The United States can pursue the domestic policies it wants, and that has a negligible impact on the value of the dollar. It was a way to understand the financial crisis happened in 2008. There was an inflow of capital into the US economy just as the giants of American finance world were collapsing.

Just as there was a major crisis in the heart of the system, investors believed that the most safest of assets was still the US government, and so the dollar went up, whereas in the past, any sensible person would be fleeing the dollar. In any economy in which there was a crisis of that scale would have suffered a collapse of its exchange rate. For the dollar, it was different, it was the other way around.