« The War: Concepts and Evolutions » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (15 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 9 : | Ligne 9 : | ||

{{hidden | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to Political Science]] | |[[Introduction to Political Science]] | ||

|[[ | |[[Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory]] ● [[The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic]] ● [[Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory]] ● [[The notion of "concept" in social sciences]] ● [[History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts]] ● [[Marxism and Structuralism]] ● [[Functionalism and Systemism]] ● [[Interactionism and Constructivism]] ● [[The theories of political anthropology]] ● [[The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas]] ● [[Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science]] ● [[An analytical approach to institutions in political science]] ● [[The study of ideas and ideologies in political science]] ● [[Theories of war in political science]] ● [[The War: Concepts and Evolutions]] ● [[The reason of State]] ● [[State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance]] ● [[Theories of violence in political science]] ● [[Welfare State and Biopower]] ● [[Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes]] ● [[Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences]] ● [[The system of government in democracies]] ● [[Morphology of contestations]] ● [[Action in Political Theory]] ● [[Introduction to Swiss politics]] ● [[Introduction to political behaviour]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation]] ● [[Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations]] ● [[Introduction to Political Theory]] | ||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |headerstyle=background:#ffffff | ||

|style=text-align:center; | |style=text-align:center; | ||

}} | }} | ||

War is a complex phenomenon that has undergone numerous conceptions and evolutions over the course of history. Different eras and societies have had different perspectives on war, and these conceptions have evolved in response to political, economic, technological and social changes. | |||

War is armed conflict between states or groups, often characterised by extreme violence, social disruption and economic disruption. It generally involves the deployment and use of military forces and the application of strategies and tactics to defeat the adversary. War can have many causes, including territorial, political, economic or ideological disagreements. Modern warfare is generally considered to have originated with the emergence of the nation state in the 17th century. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 marked the end of the Thirty Years' War in Europe and established the concept of national sovereignty. This created an international system based on independent nation-states that could legitimately resort to war. Increasing the size of armies, improving military technology and evolving tactics and strategies also contributed to the birth of modern warfare. In an age of terrorism and globalisation, the nature of warfare is changing. We are now faced with asymmetric conflicts in which non-state actors, such as terrorist groups, play a major role. In addition, the rise of cybernetics has led to the emergence of cyberwarfare. Finally, information warfare, in which information is used to manipulate or mislead public opinion or the adversary, has become a common tactic. | |||

The idea of the end of war is debated. Some argue that globalisation, economic interdependence and the spread of democratic values have made war less likely. Others argue that war is not about to disappear, citing the existence of ongoing armed conflicts, the persistence of international tensions and the possibility of future conflicts over limited resources or due to climate instability. What's more, while traditional conflicts between states may be diminishing, new forms of conflict, such as terrorism or cybernetics, are persisting. The future of war is uncertain, but what is certain is that the pursuit of diplomacy, dialogue and disarmament is essential to prevent war and promote lasting peace. | |||

First, we will explore the fundamental nature of war, before looking at the emergence of modern warfare. We will see that war transcends mere violence and acts as a regulating element in our international system, which has been shaped over several centuries. We will then examine contemporary developments in warfare, particularly in the context of terrorism and globalisation, and ask whether the nature of warfare is changing and whether its fundamental principles are evolving. Finally, we look at the future of war: is it coming to an end, or does it persist in other forms? | |||

= | = What is war? = | ||

== | == Definition of war == | ||

We're going to ask ourselves what war is and look at some of the warnings and preconceived ideas about war. There are many definitions of war, but one of the most relevant is that of Hedley Bull, the founder of the English school, who, in his 1977 book The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics, gives the following definition: "an organised violence carried on by political units against each other". | |||

Hedley Bull's definition of war highlights several key aspects of this complex phenomenon. | |||

1 | 1 "Organised violence": The use of this phrase suggests that war is not a random or chaotic series of violent acts. It is organised and planned, often in great detail. This organisation may involve the mobilisation of troops, the development of strategies and tactics, the production and acquisition of weapons, and many other logistical aspects. The violence in question is also extreme, generally involving death and serious injury, destruction of property and social instability. | ||

2. " | 2. "Conducted by political units": Here, Bull emphasises that war is an act committed by political actors - typically nation-states, but also potentially politically organised non-state groups. This reflects the fact that war is often the product of political decisions and is used to achieve political objectives. This can include objectives such as the seizure of territory, regime change, the assertion of national power, or defence against a perceived threat. | ||

3. " | 3. "Against each other": This part of the definition emphasises that war involves conflict. It is not a question of unilateral acts of violence, but of a situation in which several parties actively oppose each other. This implies an interactive dynamic where the actions of each side influence the actions of the other, creating a cycle of violence that can be difficult to break. | ||

This definition, while simple, encompasses many aspects of war. However, it is important to note that war is a complex phenomenon that cannot be fully understood or explained by a single definition. Many other perspectives and theories can also provide valuable insights into the nature of war, its origin, course and consequences. | |||

The distinction between interpersonal violence, such as crime and aggression, and war, as organised violence carried out by political units, is crucial: | |||

* Interpersonal violence: This refers to acts of violence committed by individuals or small groups, often in the context of crimes such as theft, assault, murder, etc. It is generally not coordinated or organised on a large scale, and is not intended to achieve political objectives. It is generally not coordinated or organised on a large scale, and is not intended to achieve political objectives. Motivations can be varied, ranging from personal conflict to the pursuit of material gain. | |||

* War: Unlike interpersonal violence, war is a form of large-scale violence that is carefully organised and planned by political units, usually nation states or structured political groups. War aims to achieve specific, often political, objectives through the use of force. Combatants are usually trained and equipped soldiers or militants, and conflicts are often fought according to certain rules or conventions. | |||

Hedley Bull's point about the official nature of war is crucial to understanding its nature. In his view, war is waged by political units, usually states, against other political entities. It is an action that is officially sanctioned and conducted in the name of the state. This distinction is important because it separates the notion of war from that of crime-fighting, which is also a form of organised violence but operates within a different framework. Whereas war is generally a conflict between states or political groups, crime control is an action undertaken by the state within its own borders to maintain order and security. Crime control is generally carried out by law enforcement agencies, such as the police, whose mission is to prevent and suppress crime. The aim is not to achieve political or strategic objectives, as is the case in war, but rather to protect citizens and uphold the law. This differentiation underlines the exceptional nature of war as an act of organised violence that transcends political boundaries, contrasts with internal violence, and is sanctioned by the state or political entity. War is inherently a political phenomenon, aimed at changing the status quo, often through the use of armed force, and therefore represents a distinct dimension of violence in society. | |||

Hedley Bull's definition of war is fairly complete and precise. It aptly describes the nature of modern warfare by highlighting its key aspects: it is organised violence, carried out by political units, between themselves, and generally directed outside these political units. This definition captures what many people mean by 'war', including those who study it in an academic or military context. It captures the notion that war is a structured phenomenon, with specific actors (political units), an official character, and an external orientation. This definition also serves as a basis for understanding the complexity of modern conflicts, where the lines between state and non-state actors can be blurred, and where conflicts can involve international actors and transcend national boundaries. | |||

However, it should be noted that this definition, while useful, is only one of many possible ways of defining and understanding war. Other perspectives may emphasise other aspects of war, such as its social, economic or psychological dimensions. As with any complex phenomenon, a complete understanding of war requires a multidimensional approach that takes into account its multiple facets and implications. | |||

== Deconstructing conventional wisdom == | |||

War as a concept has infiltrated our collective consciousness through history, the media, literature and other forms of cultural communication. However, our intuitive perceptions of war can be shaped by preconceptions that do not necessarily reflect the complexity of reality. | |||

== | |||

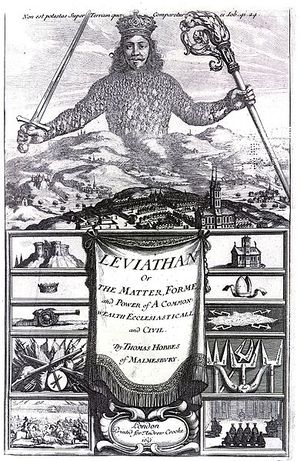

[[File:Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes.jpg|thumb|right|Frontispiece of ''Leviathan''.]] | [[File:Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes.jpg|thumb|right|Frontispiece of ''Leviathan''.]] | ||

=== | === Thomas Hobbes' approach: "the war of all against all". === | ||

For Thomas Hobbes in The Leviathan, published in 1651, war is "the war of all against all". In this book, Hobbes describes the state of nature, a hypothetical condition in which there is no government or central authority to impose order. He defines the state of nature as a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes in Latin), where individuals are in constant competition with each other for survival and resources. According to Hobbes, without a central authority to maintain order, human beings would be in constant conflict, leading to a life that would be "solitary, poor, unpleasant, brutish and short". This is why, in his view, human beings agree to give up part of their freedom in favour of a government or sovereign (Leviathan), which is capable of imposing peace and order. | |||

In "Leviathan", Hobbes argues that without a state or central authority, the lives of individuals would be in a constant state of "war of all against all". It is anarchy, Hobbes argues, that reigns in the absence of the state. Anarchy, in this context, does not necessarily mean chaos or disorganisation, but rather the absence of a central authority to impose rules and standards of conduct. For Hobbes, the state is therefore a necessary instrument for regulating inter-individual relations, preventing conflict and ensuring the security of individuals. According to Hobbes, individuals agree to give up part of their freedom in exchange for the security and stability that the state can provide. | |||

In reality, even in situations of extreme social or political instability, human beings tend to form structures and organisations to preserve order and facilitate survival. Perpetual war, as described by Hobbes in the State of Nature, is practically impossible from an empirical point of view. Moreover, waging war requires a degree of organisation and coordination that individuals in a state of anarchy would find difficult to achieve. Individuals are more inclined to band together for their own defence or to achieve common goals, which in itself can be seen as a primitive form of state or governance. It is important to note that Hobbes uses the state of nature and the 'war of all against all' as conceptual tools to argue for the importance of the state and the social contract. He does not necessarily suggest that this state of nature ever existed literally. | |||

Armed conflicts, particularly those that rise to the level of war, involve much more complex dynamics than simple aggression or individual conflict. They require significant organisation, strategic planning and substantial resources. | |||

Wars generally involve political actors - states or groups seeking to achieve specific political objectives. Thus, war is not only an extension of individual aggression or selfishness, but is also strongly linked to politics, ideology and power structures. Moreover, wars often have far-reaching social and political consequences. They can reshape borders, topple governments, bring about major societal changes, and have lasting effects on individuals and communities. For these reasons, the study of war requires a thorough understanding of many different aspects of human society, including politics, psychology, economics, technology and history. | |||

Hobbes' vision of 'war of all against all' focuses on selfishness and conflict as inherent aspects of human nature. However, war, as we know it, is not simply the product of individual selfishness or aggression. It is in fact a complex social creation that requires substantial organisation and coordination. The idea that war is in fact a product of our sociality, and not of our egoism, is very enlightening. To wage war, you need not only resources, but also an organisational structure to coordinate efforts, an ideology or goal to unify participants, and norms or rules to regulate conduct. All these elements are the product of life in society. This perspective suggests that to understand war, we need to look beyond simple instincts or individual behaviour and consider the social, political and cultural structures that enable and shape armed conflict. It also emphasises that the prevention of war requires attention to these structures, and not just to human nature. | |||

Although the Hobbesian theory of "war of all against all" suggests that war is rooted in the selfish nature of individuals, the reality is much more complex. War requires a degree of organisation, planning and coordination, all of which are characteristics of human societies rather than isolated individuals. Consequently, war can best be understood as a social phenomenon, rather than as a simple extension of individual egoism or aggression. War is often influenced by, and in turn influences, a variety of social structures and processes, including politics, economics, culture, and social norms and values. Armed conflicts do not occur in a vacuum, but are deeply rooted in specific social and historical contexts. | |||

War is much more than a simple manifestation of human aggression or selfishness. Rather, it is the result of a vast array of social and organisational factors that enable, facilitate and motivate large-scale conflict. To start a war, you need much more than a simple will or desire to fight. It requires organisational structures capable of mobilising resources, coordinating strategies and directing armed forces. These structures include bureaucratic administrations, military chains of command and logistical support systems, among others. These organisations cannot exist without the social framework that supports them. In addition, there must also be a certain type of culture and ideology that justifies and values war. Beliefs, values and social norms play a crucial role in the creation and maintenance of these organisations, as well as in motivating individuals to take part in war. War is therefore a profoundly social and structural phenomenon. It is the product of our ability to live together in society, and not of our selfishness or individual aggression. This perspective can offer important avenues for preventing conflict and promoting peace. | |||

=== Heraclitus' approach: War is the father of all things, and of all things it is king === | |||

We have just seen how to make war and make it possible, and now, with the second preconception, we are going to look at the "when". The second received wisdom is that of Heraclitus' perpetual war, which postulates that "War is the father of all things, and of all things it is king". However, this view oversimplifies reality. | |||

War, as we know it today, is a specific phenomenon that requires a certain level of social and organisational structure, as we discussed earlier. In other words, war is not simply a manifestation of human violence, but rather an organised and structured form of conflict that has evolved over time as a function of social, political, economic and technological factors. The presence of organised violence is not a universal feature of all human societies throughout history. Some societies have experienced prolonged periods of peace, while others have experienced higher levels of violence and conflict. Moreover, the nature of war itself has also changed significantly over time. Ancient warfare, for example, was very different from modern warfare in terms of strategy, technology, tactics and consequences. | |||

If we take a slightly more sociological view, we could say that war is a relatively recent phenomenon in human history, or at least it is not a timeless characteristic. Archaeological and anthropological evidence indicates that war, as we understand it today as large-scale organised conflict between political entities, is a relatively recent phenomenon in human history. It is only with the emergence of more complex and hierarchical societies, often accompanied by sedentarisation and agriculture, that we begin to see clear signs of organised warfare. Before that, although interpersonal violence and small-scale conflicts certainly existed, there is no convincing evidence of large-scale conflicts involving complex coordination and political objectives. This is not to say that human societies were peaceful or without violence, but rather that the nature of this violence was different and did not correspond to what we generally call "war". | |||

The idea that war is a recent phenomenon on the scale of human history is supported by a great deal of research in anthropology and archaeology. Before the advent of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution around 7000 BC, humans generally lived in small hunter-gatherer groups. These groups did have conflicts, but they were generally small-scale and did not resemble the organised wars we know today. We can't really talk about war. War, as we define it today, requires a certain social organisation and specialisation of work, including the formation of groups dedicated to combat. Moreover, war often involves conflicts over the control of resources, which becomes more relevant with the emergence of agriculture and the sedentarisation of populations, when resources become more localised and limited. This is why most researchers agree that war, as a structured and organised phenomenon, probably did not exist before the Neolithic Revolution, around 10,000 years ago. This means that for most of human history, war as we know it did not exist, which calls into question the idea that it is a natural and inevitable aspect of human society. So, if we assume that man appeared 200,000 years ago, war would only have affected 5% of our history. We are far from an anhistorical and universal phenomenon that has always existed. | |||

It is important to avoid essentializing war as something that is in us. If we look empirically at the facts, war has not always existed and it is linked to a developed social organisation. This form of social organisation appeared from the Neolithic period onwards and coincided with functional specialisation, i.e. the appearance of the first towns. Thus, war as an organised and institutionalised phenomenon is intrinsically linked to the emergence of more complex societies, particularly with the birth of the first cities. City life led to a much more marked division of labour, with individuals specialising in specific trades, some of which were linked to defence and warfare. Hunter-gatherer societies often have a division of labour based on sex and age, but the diversity of roles is generally limited compared with what we see in more complex agricultural societies. With the development of agriculture and the first cities, the division of labour widened considerably, allowing the formation of classes of specialised warriors. This also coincided with the emergence of the first states, which had the resources and organisation needed to wage war on a large scale. It was at this time that we saw the emergence of forms of organised and prolonged violence that we recognise as wars. | |||

It is an idea that is quite fundamental to the very idea of state-building and the development of our societies. The ability to organise and wage war has become a key element in the formation of states. In many cases, the threat of violence or war has contributed to the unification of diverse groups under a central authority, leading to the creation of nation states. This is reflected in Hobbes' theory of the social contract, in which he postulates that individuals agree to give up certain freedoms and grant authority to a supreme entity (the state) in exchange for security and order. In this sense, war (or the threat of war) can serve as a catalyst for the formation of states. Moreover, the management of war, through the raising of armies, the defence of territory, the application of international law and diplomacy, has become an essential part of the responsibilities of modern states. This is reflected in the development of dedicated bureaucracies, tax systems to fund military efforts, and internal and external policies focused on military and security issues. Thus, warfare and state formation are deeply intertwined, each influencing and shaping the other throughout human history. | |||

Professional specialisation has been a key factor in the development of human societies. This is known as the division of labour, a concept that has been widely explored by thinkers such as Adam Smith and Emile Durkheim. The division of labour can be described as a process by which the tasks necessary for the survival and functioning of a society are divided between its members. For example, some people may specialise in agriculture, while others specialise in construction, commerce, teaching or security. This specialisation allows each individual to develop skills and knowledge specific to their role, which generally increases the efficiency and productivity of the society as a whole. In turn, individuals depend on each other to meet their needs, creating a complex web of interdependence. In terms of security and the application of violence, specialisation has led to the creation of police forces and armies. These entities are responsible for maintaining order, protecting society and enforcing laws and regulations. This specialisation has also had significant implications for the conduct of war and the structuring of modern societies. | |||

War, as we understand it today, coincides with the Neolithic Revolution, a period when humans began to settle down and create more complex social structures. Prior to this, inter-group conflicts existed, but they probably didn't have the same scale or level of organisation as what we now classify as 'war'. The Neolithic Revolution saw humans evolve from nomadic hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers. This led to the creation of the first significant population density - cities - as well as the emergence of new forms of social and political structure. This increased population density and more complex structures probably increased competition for resources, which may have led to more organised conflict. In addition, with the emergence of cities, the specialisation of occupations began to develop. This specialisation included roles dedicated to the protection and defence of the community, such as warriors or soldiers, who could devote themselves entirely to these tasks rather than also having to worry about farming or hunting. This specialisation led to the emergence of more organised and effective military forces, contributing to the escalation of war as a social phenomenon. | |||

After the Neolithic Revolution, we witnessed a rapid increase in social and political complexity. Sedentarisation and agriculture led to more stable and wealthier societies, capable of supporting a growing population. With this increase in population and wealth, competition for resources intensified, leading to an increase in conflicts. The first city-states, such as those of Sumer in Mesopotamia around 5000 BC, are an excellent example of this increase in complexity. These city-states were highly organised, hierarchical societies with a clear division of labour, including military roles. They had their own governments, legal systems, religions and, very often, they owned and controlled their own territory. These city-states competed for control of resources and territory, and this competition often resulted in war. The wars of the time were often official affairs, led by kings or similar rulers, and were an important part of the politics of the day. Over time, these city-states evolved into larger and more complex kingdoms and empires, such as the Egyptian Empire, the Assyrian Empire, and later the Persian, Greek and Roman empires. These empires led to even bigger and more complex wars, often involving thousands or even tens of thousands of soldiers. | |||

== The Phalanx: Origins of Modern Organised Violence == | |||

During classical antiquity, and especially during the era of the Roman Empire, warfare took a qualitative leap forward in terms of organisational and technological complexity. | |||

In organisational terms, the Roman army became a veritable war machine, with a clear hierarchy, strict discipline, rigorous training and sophisticated logistics. The Roman army model, based on the legion as the basic unit, enabled the Romans to deploy forces quickly and efficiently over a vast territory. In terms of technology, the period also saw the introduction and spread of new weapons and war equipment. The Romans, for example, developed the pilum, a type of javelin designed to penetrate shields and armour. They also innovated in the construction of siege engines, such as catapults and battering rams. | |||

The technological dimension of warfare was not limited to weapons and equipment. The Romans were particularly effective in using engineering to support their military efforts. For example, they built an extensive network of roads and bridges to facilitate the rapid movement of their troops. They also used their engineering know-how to build forts and fortifications, and to conduct complex siege operations. These organisational and technological innovations made warfare an increasingly complex and costly undertaking. However, they also helped to strengthen the power of empires like Rome, enabling them to conquer and control vast territories. | |||

The evolution of warfare is closely linked to the growing complexity of societies. The phalanx is a perfect example of this. The phalanx was a combat formation used by the armies of ancient Greece. It was a heavy infantry unit made up of soldiers (hoplites) who stood side by side in close ranks. Each soldier carried a shield and was equipped with a long spear (sarissa), which he used to attack the enemy while remaining protected behind the shield of his neighbour. The phalanx was a highly organised and disciplined formation that required intensive training and precise coordination. Its main objective was to crush the enemy on initial impact, using the collective strength of the soldiers to break through the enemy lines. | |||

This represented a great advance on the more haphazard fighting methods used previously. This more complex combat organisation reflected the more complex structure of Greek society at the time. Citizen-soldier armies had to be well disciplined and well trained to be able to use the phalanx effectively. During his military campaigns, Alexander the Great perfected the use of the phalanx, adding elements of cavalry and light infantry to create a more flexible and adaptable military force. This contributed to his military successes and the expansion of his empire. | |||

The evolution of warfare has been greatly influenced by technological progress. As societies developed and became more complex, technology played an increasingly important role in the way wars were fought. From the phalanxes of ancient Greece, to the use of catapults and other siege engines during the Middle Ages, to the use of gunpowder in China and Europe, technology has always helped to shape military strategies. This trend has continued into the modern era with the rise of artillery, steam-powered warships, submarines, aircraft, tanks and finally nuclear weapons. More recently, cyber warfare and armed drones have become key elements of the contemporary battlefield. Technology has not only influenced tactics and combat strategies, but has also transformed logistics, communications and military intelligence. It has enabled military action to be taken faster, more effectively and on a larger scale.[[File:Syntagma phalangis.jpg|thumb|350px|center|Macedonian phalanx.]] | |||

The Middle Ages were marked by a change in the way war was waged. The fall of the Roman Empire meant a loss of the advanced military organisation and technology of the Romans. Conflicts at this time were often more feudal in nature, involving knights and local lords, and battles were often smaller and more dispersed. Warfare focused more on sieges of castles and raids than on large, pitched battles. | |||

In the 15th century, with the onset of the Renaissance and the formation of the first modern nation-states, we witnessed a new transformation in warfare. Technological innovation, in particular the introduction of artillery and firearms, changed the dynamics of warfare. Military organisation has become more centralised and structured, with standing armies commanded by the state. | |||

The modern state also played a major role in the transformation of warfare. Nation states began to assume responsibility for the defence and security of their citizens. This led to the creation of military bureaucracies, recruitment and training systems, and a logistical infrastructure to support standing armies. The modern state has also enabled resources to be mobilised on a much larger scale than was possible under previous feudal systems. These changes had a profound influence on the nature of warfare and laid the foundations for warfare as we know it today. | |||

== The Influence of War on Political Modernity == | |||

Putting the long history of humanity into perspective, war as we understand it today is a relatively recent phenomenon. Its presence is closely linked to the emergence and development of more complex social and political structures. Going back to the Stone Age, we find little evidence of large-scale organised violence. The appearance of war is generally associated with the advent of civilisation, which began with the Neolithic Revolution, when human beings began to settle down and create more organised societies. With the appearance of the first city-states around 5000 BC, war became a more common phenomenon, as these political entities competed for territory and resources. War took on a more organised and structured form, with standing armies and a military strategy. The development of modern warfare from the 17th century onwards coincided with the emergence of the modern state. With greater resources and a centralised administrative structure, nation states were able to wage war on an unprecedented scale and with unprecedented intensity. | |||

The history of war is also the history of the state. On the one hand, the threat of war can encourage the creation of states. Faced with hostile neighbours, communities may choose to unite under a single political authority to defend themselves. The modern state was often born out of this process, as illustrated by Thomas Hobbes' famous quote: "Man is a wolf to man". On the other hand, the conduct of war requires large-scale organisation and coordination. States have provided this structure, by raising armies, imposing taxes to finance military campaigns, and establishing military strategies and policies. In times of war, states have often increased their power and reach, both over their own citizens and over the territory they control. Finally, wars have often changed the form and nature of states. Conflict can lead to the dissolution or creation of new states, as illustrated by the history of the twentieth century, which saw the end of many colonial empires and the creation of new nation states. It is difficult to understand the history of the state without considering the role of war, and vice versa. | |||

War and the modern state are profoundly linked in political history. This relationship is central to understanding the evolution of human societies and the form that armed conflict takes. The modern state, as it developed in Europe from the 17th century onwards, is characterised by the centralisation of power and a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. The formation of nation states and the emergence of the Westphalian system coincided with a major transformation in the nature of warfare. Firstly, the modern state has institutionalised war. The state has a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, and war has become a state affair. This development has led to the establishment of rules and structures for the conduct of war. Secondly, the modern state has professionalised warfare. With the centralisation of power, states were able to maintain standing armies. This has led to increasingly organised and technologically advanced warfare. Thirdly, the modern state has nationalised war. In pre-modern societies, wars were often fought by lords or chiefs acting in their own name. With the modern state, war has become a matter for the nation as a whole. War, as we understand it today, is a creation of the modern state. It is the product of the evolution of human political organisation and the concentration of power in the hands of the state. | |||

The state, as we understand it today, is a specific form of political organisation that emerged at a particular period in history. There are many other forms of political organisation that have existed throughout history and still exist today in certain parts of the world. Empires, for example, were a common form of political organisation in ancient times and up until the beginning of the 20th century. They were characterised by a central authority (usually an emperor or king) that dominated a number of different territories and peoples. City-states were another form of political organisation, particularly widespread in ancient Greece and Renaissance Italy. In this system, a city and its surrounding territory formed an independent political entity. Colonies are also a form of political organisation, although often under the domination of another political entity (such as an empire or a state). Colonies were particularly common during the era of European imperialism from the 16th to the 20th centuries. That said, while the state is a specific and relatively recent form of political organisation, it has had a profound influence on the nature of warfare and how it is conducted. This is why the study of the state is so important to understanding modern warfare.[[File:Arc-et-Senans - Plan de la saline royale.jpg|thumb|250px|right|Arc-et-Senans - Plan of the royal saltworks.]] | |||

The state is often seen as a necessary structure to ensure social stability, security, respect for the law and the provision of essential public services such as education, health, transport, etc. However, this positive perception of the state should not prevent us from understanding the more complex and sometimes problematic aspects of the state's existence. However, this positive perception of the state should not prevent us from understanding the more complex and sometimes problematic aspects of the state's existence. One aspect relates to the state's monopoly of legitimate violence, according to Max Weber's classic sociological theory. This monopoly allows the state to maintain order and enforce the law, but it also allows the state to wage war. The fact that war is generally waged by states, and that it is intrinsically linked to the birth and development of the modern state, is a reminder that the state is not only a force for stability and well-being, but can also be a source of violence and conflict. This is something we need to bear in mind when we think about the state and its role in society. War, violence and conflict are not mere aberrations, but an integral part of the nature of the state. This is why understanding war is so essential to understanding the state. | |||

One of the main functions of the state is to maintain peace and order within its borders. This is achieved through a range of institutions, such as the police force and the judiciary, which are responsible for upholding the law and preventing or resolving conflicts between citizens. The state is often seen as the guarantor of security and stability, and this is one of the reasons why citizens agree to cede some of their freedom and power to it. However, the situation is very different beyond the borders of the state. At international level, there is no entity comparable to a state that is capable of enforcing law and order. Relations between states are often described as being in a state of "anarchy" in the sense that there is no higher central authority. This can lead to conflict and war, as each state has the freedom to act as it sees fit to defend its interests. | |||

The State plays a major role in maintaining international peace. As a participant in international organisations such as the UN, WTO, NATO and others, the state helps to formulate and respect international norms and rules, which are essential for preventing and managing conflicts between nations. Furthermore, by signing and abiding by international treaties, states actively participate in the creation of a rules-based world order, which contributes to international stability and security. In this sense, the state is seen as an essential player in modern civilisation, capable of establishing and maintaining order, promoting cooperation and avoiding chaos and anarchy. This is generally seen as a positive development compared with previous historical periods, when violence and war were more common means of resolving conflicts. | |||

One of the main justifications for the existence of the state is its ability to maintain order and prevent chaos. The concept of "monopoly of legitimate violence" is fundamental here. According to this concept, formulated by the German sociologist Max Weber, the state has the exclusive right to use, threaten or authorise physical force within the limits of its territory. In this sense, the state is often seen as an antidote to the Hobbesian 'state of nature', where, in the absence of any centralised power, life would be 'solitary, poor, brutal and brief'. The state is therefore often seen as the actor that makes it possible to maintain order, prevent chaos and anarchy, and ensure the security of its citizens. | |||

An effective state is generally able to maintain public order, ensure the safety of its citizens and provide essential public services, thereby contributing to social stability and peace. However, in areas where the state is weak, absent or ineffective, situations of chaos can arise. Conflict zones, for example, are often characterised by the absence of a functioning state capable of maintaining law and order. Similarly, in failed or failing states, the inability to provide security and basic services can lead to high levels of violence, crime and instability. | |||

Mass violence, such as genocide, is a phenomenon that has been greatly facilitated by the emergence of the modern state and industrial technology. Bureaucratic efficiency, the ability to mobilise and control vast resources, which are typical features of modern states, can unfortunately be misused for destructive purposes. Take the example of the Shoah during the Second World War. The systematic and large-scale extermination of Jews and other groups by the Nazis was made possible by the modern industrial state and its bureaucratic apparatuses. Similarly, the Rwandan genocide in 1994, in which some 800,000 Tutsis were killed in the space of a few months, was perpetrated on a massive scale and with terrifying efficiency largely thanks to the mobilisation of state structures and resources. | |||

The two world wars are typical examples of total war, a concept that describes a conflict in which the nations involved mobilise all their economic, political and social resources to wage war, and in which the distinction between civilians and military combatants is blurred, exposing the entire population to the horrors of war. The First World War introduced the industrialisation and mechanisation of warfare on an unprecedented scale, with the massive use of new technologies such as heavy artillery, aircraft, tanks and poison gas. The violence of this war was amplified by the total involvement of the belligerent nations, with their economies and societies completely mobilised for the war effort. The Second World War further intensified the concept of total war. It was characterised by the massive bombing of entire cities, the systematic extermination of civilian populations and the use of nuclear weapons. This war also saw the large-scale use of propaganda, the exploitation of the war economy and the massive mobilisation of manpower. Total war is another manifestation of the way in which modernity and the modern state have allowed new forms of violence to emerge on a massive scale. | |||

The twentieth century was marked by unprecedented violence as a result of two world wars, numerous regional conflicts, genocides and totalitarian regimes. This level of violence is often attributed to a combination of factors, including the emergence of powerful modern states, the availability of weapons of mass destruction and extreme ideologies. The world wars caused tens of millions of deaths. In addition, other conflicts such as the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, the Rwandan genocide and the Stalinist and Maoist purges resulted in the deaths of millions more. Internal political violence, often carried out by totalitarian regimes, was also a major source of violence in the twentieth century. Regimes such as Stalin's in the Soviet Union, Mao's in China, Pol Pot's in Cambodia and many others used political violence to eliminate opponents, achieve ideological goals or maintain power. In short, the violence of the twentieth century shows just how double-edged modernity and the modern state have been: on the one hand, they have allowed an unprecedented level of development, prosperity and stability in many parts of the world; on the other, they have allowed an unprecedented level of violence and destruction. | |||

The modern state, with its sovereignty, defined territory, population and government, is expected to offer its citizens protection from violence. It is supposed to guarantee order and stability through the rule of law, efficient administration and the protection of its citizens' rights and freedoms. However, the history of the 20th century shows that the modern state can also be a major source of violence. World wars, regional conflicts, genocide and political purges have largely been perpetrated or facilitated by modern states. These forms of violence are often linked to the exercise of state power, the defence of the established order, or the application of certain ideologies or policies. The modern state therefore has two faces. On the one hand, it can guarantee order, security and stability, and provide a framework for prosperity and development. On the other hand, it can be a major source of violence and oppression, particularly when it is used for the purposes of war, political repression or the achievement of certain ideological goals. It is important to understand this paradox if we are to grasp the complexity of the political and social challenges we face in the modern world. | |||

= | = The evolution of war throughout history = | ||

== War as the Builder of the Modern State == | |||

[[Fichier:Passage de la Seine par armee anglaise et pillage Vitry XIVe siecle.jpg|vignette|droite|The crossing of the Seine and the sack of Whittier by English troops in the 14th century.]] | |||

To study war, we must first focus on its links with the modern state as a political organisation. We are going to see how war today is shaped by and through the emergence of the modern state. We shall begin by seeing that war is a matter for the State. In order to introduce the idea that war is linked to the very construction of the State and the emergence of the State as a form of political organisation in Europe from the end of the Middle Ages, the best way to do this is as the sociohistorian Charles Tilly put it in his article ''War Making and State Making as Organised Crime'', which developed the idea of war making/state making: it was by making war that we made the State, and vice versa. | |||

In 'War Making and State Making as Organized Crime', Charles Tilly offers a provocative socio-historical analysis of modern state-building in Western Europe. He argues that the processes of state-building and warfare are intrinsically linked, and even compares states to criminal organisations to highlight the coercive and exploitative aspects of their formation. According to Tilly, the formation of modern states is largely driven by the efforts of ruling elites to mobilise the resources needed for war. To this end, these elites resort to means such as taxation, conscription and expropriation, which can be likened to forms of racketeering and extortion. Furthermore, Tilly argues that state-building was also facilitated by the monopolisation of the use of legitimate force. In other words, rulers sought to eliminate or subordinate all other sources of power and authority in their territory, including feudal lords, corporations, guilds and armed bands. This process often involved the use of violence, coercion and political manipulation. Finally, Tilly points out that state-building also required the construction of a social consensus, or at least the acquiescence of populations, through the development of a national identity, the establishment of social and political institutions, and the provision of services and protections. This analysis offers a critical and scathing perspective on the construction of modern states, highlighting their violent and coercive roots, while underlining their key role in structuring our contemporary societies. | |||

The conception of the modern state as we know it today is mainly based on the European model, which emerged during the Renaissance and Modern periods, between the 14th and 17th centuries. This evolution was marked by the centralisation of political power, the formation of defined national borders, the development of an administrative bureaucracy and the monopolisation of the use of legitimate force by the state. However, it is important to note that other political models exist elsewhere in the world, based on different historical, cultural, social and economic trajectories. For example, in some societies, the political structure may be more decentralised, or based on different principles, such as reciprocity, hierarchy or equality. Furthermore, the process of exporting the European state model, notably through colonisation and more recently through state-building or nation-building, has often met with resistance and may have led to conflict and tension. This is often due to the fact that these processes can fail to take account of local realities and can sometimes be perceived as forms of cultural or political imposition. | |||

In his article "War Making and State Making as Organized Crime", Charles Tilly proposes a framework for understanding the state formation process, particularly on Europe between the 15th and 19th centuries. Tilly sees the emergence of the state as the product of two interconnected dynamics: war making and state making. | |||

* War making: Tilly postulates that states have been shaped by a constant need to prepare for, wage and finance war. Wars, particularly in the European context, have been key factors in the development of state structures, not least because of the resources needed to wage them. | |||

* State making: This is the process by which the central power of a state is consolidated. For Tilly, this involved controlling and neutralising its internal rivals (notably the feudal lords) and imposing its authority over the entire territory under its control. | |||

These two processes are closely linked, as wars provide the impetus for the consolidation of the state, while themselves being made possible by this consolidation. For example, to finance wars, states had to set up more efficient tax and administrative systems, strengthening their authority. | |||

=== War and the Modern State === | |||

[[Fichier:Einhard vita-karoli 13th-cent.jpg|vignette|right|Ilustración manuscrita del siglo XIII de Vita Karoli Magni.]] | |||

The feudal system was a complex structure of relations between lords and the king, based on land ownership (or "fiefs") and loyalty. Lords had a great deal of autonomy over their lands and were generally responsible for security and justice on their lands. In exchange for their fief, they had to swear allegiance to the king and provide him with military support when he needed it. This system of vassalage formed the basis of power during the Middle Ages. However, with the advent of the modern state, this system was gradually replaced. The consolidation of the state was accompanied by an effort to centralise power, which often involved abolishing or reducing the power of feudal lords. A key element in this process was the need to finance and support warfare. Kings began to develop administrative and fiscal structures to raise funds and recruit armies directly, rather than relying on feudal lords. This strengthened their authority and enabled the formation of more centralised and bureaucratic states. | |||

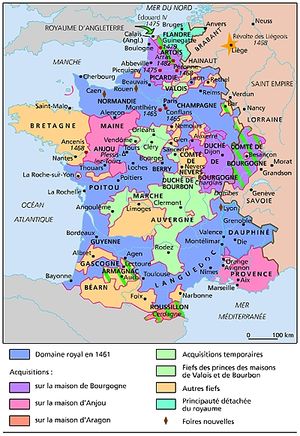

According to Charles Tilly, war was a powerful driving force behind the formation of the modern state. In the Middle Ages, competition between lords to expand their territory and increase their power often led to conflict. Lords were constantly at war with each other, seeking to gain control of each other's lands and resources. What's more, these local conflicts were often linked to wider conflicts between kingdoms. Kings needed a solid power base to support their war efforts, which led them to seek to strengthen their control over their lords. These dynamics created constant pressure for greater centralisation and more efficient organisation. The kings developed more sophisticated administrations and more efficient tax systems to support their war efforts. At the same time, they sought to limit the power of the feudal lords and assert their own authority. These processes laid the foundations of the modern state.[[Fichier:France sous Louis XI.jpg|300px|vignette|right]] | |||

Norbert Elias, a German sociologist, developed the concept of "eliminatory struggle" in his work "The Civilizing Process". In this context, it refers to a competition in which the players eliminate each other until only a few, or even one, remain. In the context of state formation, this can be seen as a metaphor for the way in which feudal lords fought for power and territory during the Middle Ages. Over time, some lords were eliminated, either by military defeat or by assimilation into larger entities. This process of elimination contributed to the centralisation of power and the formation of the modern state. | |||

Over the centuries, many French kings gradually strengthened their power, seizing territories from the feudal nobility and consolidating central authority. These efforts were often supported by strategic marriage alliances, military conquests, political arrangements and, in some cases, the natural or forced extinction of certain noble lines. Louis XI, in particular, played a crucial role in this process. King from 1461 to 1483, he was nicknamed "l'Universelle Aragne" or "the Universal Spider" because of his cunning and manipulative policies. Louis XI worked hard to centralise royal power, reducing the influence of the great feudal lords and establishing a more efficient and direct administration throughout the kingdom. This contributed to the formation of the modern state, with centralised power and organised administration, which would be strengthened over the centuries, notably with Francis I and Louis XIV, the "Sun King". | |||

France and Great Britain are often cited as typical examples of the emergence of the modern state. In France, the kings gradually centralised power, creating a more direct and efficient administration. The apogee of this centralisation was probably reached during the reign of Louis XIV, who declared "I am the State" and ruled directly from his palace at Versailles. However, this process was interspersed with periods of conflict and revolt, such as the Fronde and, later, the French Revolution. Great Britain, on the other hand, followed a slightly different path towards the formation of the modern state. King Henry VIII consolidated royal power by establishing the Church of England and abolishing monasteries, but Britain also saw a strong movement to limit royal power. This culminated in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the establishment of a constitutional system in which power was shared between the King and Parliament. In both cases, war played a major role in the formation of the state. The need to raise armies, levy taxes to finance wars and maintain internal order contributed greatly to the centralisation of power and the creation of efficient administrative structures. | |||

External competition, particularly from the Renaissance onwards and during the modern era, was a major driving force in the formation of states and the structuring of the international system as we know it today. This can be seen in the development of diplomacy, alliances and treaties, wars for the conquest and control of territories, and even colonial expansion. It also led to the clearer definition of national borders and the recognition of state sovereignty. In particular, the involvement of Louis XI and his successors in the wars in Italy and against England played an important role in consolidating France as a state and in defining its borders and national interests. Similarly, the competition between European powers for territories abroad during the era of colonisation also helped to shape the international system. | |||

The imperial ambitions of rulers such as Louis XI were partly motivated by the desire to consolidate their power and authority, both internally and externally. They needed resources to wage wars, which often meant demanding higher taxes from their subjects. These wars also often had a religious dimension, with the idea of reunifying the Christian world. As these kingdoms developed and began to clash with each other, an international system began to take shape. It was a slow and often confrontational process, with many wars and political conflicts. But over time, these states began to recognise each other's sovereignty, to establish rules for international interactions and to develop institutions to facilitate these interactions. | |||

All this has led to the formation of a system of interconnected nation-states, in which each state has its own interests and objectives, but also a certain obligation to respect the sovereignty of other states. This is the foundation of the international system we have today, although the specifics have evolved over time. | |||

=== The Role of War in the Interstate System === | |||

To wage war (war-making), a state must mobilise significant resources. This includes material resources, such as money to finance the army and buy weapons, food to feed the army, and materials to build fortifications and other military infrastructure. It also requires human resources, such as soldiers to fight and workers to produce the necessary goods. To obtain these resources, the state must be able to exercise effective control over its territory and its inhabitants. This is where state-making comes in. The state must set up effective taxation systems to collect the money needed to finance the war. It must also be able to recruit or conscript soldiers, which may require efforts to instil a sense of loyalty or duty to the state. In addition, it must be able to maintain order and resolve conflicts within its borders, so that it can concentrate on the war outside. So war and state-building are intimately linked. One requires the other, and the two reinforce each other. As Charles Tilly wrote, "States make wars and wars make States". | |||

The need to wage war led states to develop an efficient bureaucracy capable of collecting resources and organising an army. This process strengthened the state's ability to govern its territory and its inhabitants, in other words its sovereignty. To register the population, collect taxes and recruit soldiers, the state had to set up an administration capable of managing these tasks. This involved developing systems to record information about the inhabitants, establishing laws on taxes and conscription, and creating bodies to enforce these laws. Over time, these bureaucratic systems evolved to become increasingly efficient and sophisticated. They also helped to reinforce the authority of the state, by ensuring that its legitimacy was accepted by the people. People were more inclined to pay taxes and serve in the army if they believed that the state had the right to ask them to do so. War played a central role in the process of state-building, not only by encouraging the development of an efficient bureaucracy, but also by reinforcing the authority and legitimacy of the state. | |||

According to Charles Tilly, the modern state developed out of a long-term process known as 'war making' and 'state making'. This theory argues that wars were the main driving force behind the growth of state power and authority in society. Tilly's theory suggests that the modern state was formed in a context of conflict and violence, where the ability to wage war and effectively control territory were key factors in the survival and success of the state. | |||

After the end of the Middle Ages, Europe entered a period of intense competition between emerging nation states. These states sought to extend their influence and assert their dominance over others, which often led to wars. One of the most emblematic examples of this era is Napoleon Bonaparte. As Emperor of France, Napoleon sought to establish French dominance over the European continent, creating an empire that stretched from Spain to Russia. His attempt to create a borderless and inclusive empire was in reality an attempt to subjugate other nations to the will of France. However, this period of rivalry and war also saw the consolidation of the nation state as the principal form of political organisation. States strengthened their control over their territory, centralised their authority, and developed bureaucratic institutions to administer their affairs. The emergence of the modern nation-state in the post-medieval period was largely the product of imperial ambitions and inter-state rivalries. These factors led to the establishment of an interstate system based on sovereignty and war as a means of resolving conflicts. And this development has had a profound impact on our world today. | |||

After a period of intense war and conflict, a certain balance of power was established between the European nation states. This balance, often referred to as the "balance of power", has become a fundamental principle of international politics. The balance of power assumes that national security is ensured when military and economic capabilities are distributed in such a way that no single state is able to dominate the others. This encourages cooperation and peaceful competition and, in theory, helps prevent wars by discouraging aggression. This process has also led to the stabilisation of borders. States finally recognised and respected each other's borders, which helped to ease tensions and maintain peace. | |||

From there, the idea of sovereignty emerged, meaning that the idea of authority over territory was divided between areas over which sovereignties were exercised that were mutually exclusive. Sovereignty is a fundamental principle of the modern international system, based on the notion that each state has supreme and exclusive authority over its territory and population. This authority includes the right to make laws, to enforce those laws and to punish those who break them, to control borders, to conduct diplomatic relations with other states and, if necessary, to declare war. Sovereignty is intrinsically linked to the notion of the nation state and is fundamental to understanding the dynamics of international relations. Each state is considered to have the right to manage its own internal affairs without external interference, which is recognised as a right by other states in the international system. | |||

Ultimately, the principle of sovereignty gave rise to a universalism of the nation-state that was not that of the Empire, since the principle of sovereignty was recognised by all as the organising principle of the international system. The principle of sovereignty and equality between all States is the foundation of the international system and of the United Nations. This means that, in theory, every state, whether large or small, rich or poor, has a single vote at the United Nations General Assembly, for example. This follows from the principle of sovereign equality, which is enshrined in the United Nations Charter. Article 2, paragraph 1 of the UN Charter states that the Organisation is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its members. | |||

The idea of the United Nations stems from the idea of the principle of sovereignty as the organiser of the international system. This interstate system that is being set up is organised around the idea that there is a logic of internal equilibrium where the State administers a territory, i.e. the "police"; and external equilibrium where it is the States among themselves that settle their affairs. This distinction is central to the concept of state sovereignty. It is the state that has the prerogative and duty to manage internal affairs, including implementing laws, ensuring public order, providing public services and administering justice. This is known as internal sovereignty. External sovereignty is the right and capacity of a state to act autonomously on the international stage. This includes the right to enter into relations with other states, to sign international treaties, to participate in international organisations, and to conduct its foreign policy in accordance with its own interests. | |||

Once all these states have been formed, they must communicate with each other. Since each of them has to survive as a state and there are other states, how are they going to communicate? If we start from the principle that war is an institution, it serves to do exactly that. War, as an institution, has been a way for states to communicate with each other. This does not necessarily mean that war is desirable or inevitable, but it has certainly played a role in the formation of states and the definition of relations between them. In European history, for example, wars have often been used to resolve conflicts over territory, power, resources or ideology. The results of these wars have often led to changes in borders, alliances and the balance of power between states. | |||

According to John Vasquez, war is a learned form of political decision-making in which two or more political units allocate material goods or goods of symbolic value on the basis of violent competition. John Vasquez's definition highlights the violent competition aspect of war. According to this view, war is a mechanism by which political units, usually states, resolve their disagreements or rivalries. This may involve issues of power, territory, resources or ideologies. This definition underlines a vision of war that is firmly rooted in a realist tradition of thought in international relations, which sees international politics as a struggle of all against all, where conflict is inevitable and war is a natural tool of politics. | |||

We are moving away from the idea of war as something anarchic or violent; war is something that has been developed in its modern conception in order to settle disputes between states, it is a conflict resolution mechanism. This seems counter-intuitive because war is generally associated with anarchy and violence. However, in the context of international relations and political theory, war can be understood as a mechanism for resolving conflicts between states, despite its tragic consequences. This perspective does not seek to minimise the violence and destruction caused by war, but rather to understand how and why states choose to use military force to resolve their disagreements. According to this perspective, war is not a state of chaos, but a form of political conduct governed by certain norms, rules and strategies. This is why war is often described as a "continuation of politics by other means" - a famous phrase by the military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. This means that war is used by states as a tool to achieve political objectives when other means fail. | |||

[[Fichier:1280px-Ajaccio tempesti bataille.JPG|vignette|left|Scène de bataille au Musée Fesch d'Ajaccio par Antonio Tempesta.]] | War can be understood as an ultimate conflict resolution mechanism, used when disagreements cannot be resolved by other means. This process requires the mobilisation of significant resources, such as armed forces, financed by the tax revenues of the belligerent states. The ultimate aim is to reach an agreement, often determined by the outcome of the fighting. However, victory does not necessarily mean a final settlement of the conflict in favour of the victor. The outcome of the war may lead to compromises, political and territorial changes, and sometimes even the emergence of new disputes.[[Fichier:1280px-Ajaccio tempesti bataille.JPG|vignette|left|Scène de bataille au Musée Fesch d'Ajaccio par Antonio Tempesta.]] | ||

War can be viewed from a number of angles, depending on the perspective adopted. Viewed from a humanitarian perspective, it is often seen in terms of the suffering and loss of life it causes. From this perspective, questions emerge about the protection of civilians, human rights and the consequences for the socio-economic development of the affected areas. From a legal point of view, war involves a complex set of regulations and international laws, including international humanitarian law, the law of war and various international agreements and treaties. These regulations aim to limit the impact of war, in particular by protecting civilians and banning certain practices and weapons. However, despite these regulations, the legal stakes remain high, especially when it comes to determining the legitimacy of an armed intervention, assessing responsibilities in the event of a violation of international law, and managing post-conflict consequences such as transitional justice and reconstruction. | |||

In short, war, as a conflict resolution mechanism, is a complex phenomenon that involves humanitarian, political, economic and legal issues. This course takes a political science angle to look at where this phenomenon comes from and what it is used for. We are not interested here in the normative dimension of war. | |||

We are coming to the idea that war is a mechanism for resolving conflicts and that therefore, if strategy has an end, the end and the goal of this strategy is peace. The ultimate aim of military strategy is often to establish or restore peace, even if the path to achieving it involves the use of force. This idea has its origins in the writings of several military thinkers, the most famous of whom is perhaps Carl von Clausewitz. In his book "On War", Clausewitz described war as "the continuation of politics by other means". This perspective suggests that war is not an end in itself, but a means to achieve political objectives, which may include the establishment of peace. Moreover, in the tradition of international relations theory, war is often seen as an instrument that states can use to resolve disputes when they fail to reach agreement by peaceful means. Thus, although war is a violent and destructive act, it can be seen as part of a wider process aimed at restoring stability and peace. | |||

The two are linked. We have a concept where peace is intimately linked to war and, above all, the definition of peace is intimately linked to war. Peace is understood as the absence of war. It's interesting to see how the aim of strategy is to win and return to a state of peace. It is really war that determines this state. There is a very strong dialectic between the two. We are interested in the relationship between war and the state, but also between war and peace. This is a fundamental relationship that we won't be looking at today. In many theoretical frameworks, peace is defined in opposition to war. In other words, peace is often conceptualised as the absence of armed conflict. This view is called "negative peace", in the sense that peace is defined by what it is not (i.e. war) rather than by what it is. Military strategy often aims to restore this state of 'negative peace' by winning the war or achieving favourable conditions for ending the conflict. | |||

We speak of peace because what is important is that in the conception of war that is being put in place with the emergence of this interstate system, i.e. with states being formed internally and competing with each other externally, war is not an end in itself, the goal is not the conduct of war itself, but peace; war is waged in order to obtain something. This is Raymond Aron's view. Raymond Aron, a French philosopher and sociologist, is famous for his work on the sociology of international relations and political theory. In his view, war is not an end in itself, but a means to achieve peace. This means that war is a political instrument, a tool used by states to achieve specific objectives, generally with the aim of resolving conflicts and achieving peace. From this perspective, war is an extreme form of diplomacy and negotiation between states. It is an extension of politics, carried out when peaceful means fail to resolve disputes. It is for this reason that Aron declared that "peace is the end, war is the means". | |||

The concept of war as a conflict resolution mechanism is based on the idea that war is a tool of politics, a form of dialogue between states. It is used when peaceful means of conflict resolution have failed or when the objectives cannot be achieved by other means. From this perspective, states use war to achieve their strategic objectives, whether to protect their territorial interests, extend their influence or strengthen their security. These objectives are generally guided by a clearly defined military strategy, which aims to maximise the effectiveness of the use of force while minimising losses and costs. | |||

== | == Carl von Clausewitz's Approach to War == | ||

[[Fichier:Clausewitz.jpg|vignette|200px|droite|Carl von Clausewitz.]] | [[Fichier:Clausewitz.jpg|vignette|200px|droite|Carl von Clausewitz.]] | ||

Carl von Clausewitz, | Carl von Clausewitz, a Prussian officer in the early 19th century, played a decisive role in the theorisation of war. He wrote "On War" (Vom Kriege in German), which has become one of the most influential texts on military strategy and the theory of war. | ||

Carl von Clausewitz | Carl von Clausewitz served in the Prussian army during the Napoleonic Wars, which lasted from 1803 to 1815. During this period, he gained valuable experience of combat and military strategy, which influenced his theories of war. Clausewitz took part in several major battles against Napoleon's army, and witnessed the dramatic changes in the way wars were fought in the early 19th century. It was during this period that he began to develop his theory that war is an extension of politics. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Clausewitz continued to serve in the Prussian army and began writing his major work, "On War". However, he died before he could complete the work, which was published posthumously by his wife. | ||

Clausewitz | Clausewitz said that war is "the continuation of politics by other means". This quotation, probably Clausewitz's most famous, expresses the idea that war is an instrument of national policy, and that military objectives must be guided by political objectives. In other words, war is a political tool, not an end in itself. Clausewitz also emphasised the importance of the "fog of war" and "friction" in the conduct of military operations. He argued that war is inherently uncertain and unpredictable, and that commanders and strategists must be able to manage these uncertainties. Despite his death in 1831, Clausewitz's thinking continues to exert a major influence on military and strategic theory. His work is studied in military academies around the world and remains an essential reference in the field of military strategy. | ||

Clausewitz | Clausewitz defines war as an act of violence designed to force an adversary to carry out our will. This is a very rational framework, not the logic of a "war madman". War is fought to achieve something. Carl von Clausewitz conceptualised war as an act of violence aimed at forcing an adversary to carry out our will. According to him, war is not an irrational or chaotic undertaking, but rather an instrument of policy, a rational means of pursuing a state's objectives. In his major work "On War", Clausewitz develops this idea by asserting that war is simply the continuation of politics by other means. In other words, states use war to achieve political objectives that they cannot achieve by peaceful means. | ||

Imagine a state that is a government with the objective of acquiring fertile land to improve its economy or food security. As its neighbour is unwilling to give up this land voluntarily, the state chooses to resort to war to achieve its objective. If the warring state is victorious, it is likely that a peace treaty will be drawn up to formalise the land transfer. This treaty could also include other provisions, such as war indemnities, arrangements for displaced populations and a promise of future non-aggression. The initial objective (the acquisition of fertile land) was thus achieved by means of war, which was used as an instrument of policy. | |||

This conception of war, as expressed by Clausewitz, highlights the fact that war is an extension of politics by other means. In this context, war is seen as a tool of politics, an option that can be employed when other methods, such as diplomacy or trade, have failed to resolve conflicts between states. | |||

It is essential to understand that, according to Clausewitz, war is not an autonomous entity, but rather an instrument of policy that is controlled and directed by the political authorities. In other words, the decision to declare war, as well as the management and conduct of the war, are the responsibility of political leaders. Military objectives are therefore subordinate to political objectives. In Clausewitzian thinking, war is a means of achieving political objectives that cannot be achieved by other methods. However, it is always seen as a temporary solution and not as a permanent state. War is therefore not an end in itself, but a means to an end: the political objective defined by the state. Once this objective has been achieved, or when it is no longer possible to achieve it, the war ends and we return to a state of peace. This is why the notion of peace is intrinsically linked to that of war: war aims to create a new state of peace that is more favourable to the state waging it. | |||

== | == The Westphalian system == | ||