The study of ideas and ideologies in political science

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

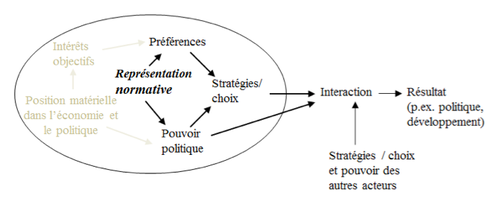

Ideas and ideologies have a significant influence on political outcomes and policies. Ideas, which represent the beliefs and perceptions of individuals, and ideologies, which are broader systems of ideas, play a crucial role in shaping public opinion. They shape the way political issues are perceived and influence the positions taken by individuals on different issues. In addition, ideas and ideologies guide the choices made by political decision-makers when formulating specific policies. Political parties and governments, aligned with particular ideologies, adopt policies in line with them. Consequently, ideas and ideologies can mobilise citizens and voters around certain political objectives. They are also used to form political coalitions, where like-minded groups come together to influence political outcomes. Although other factors such as economic interests and institutional constraints also play a role, ideas and ideologies provide an essential ideological framework that shapes political outcomes and policies.

Definition and Importance of Ideas in Political Science[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

According to Goldstein and Keohane in their 1993 book Ideas and Foreign Policy: Beliefs, Institutions, and Political Change, ideas can be understood as normative representations, causal representations, or worldviews.[1] These different forms of ideas play a key role in how foreign policies are formulated and implemented.

Ideologies can play a significant role as policy-makers, particularly in influencing the global vision of governments and policy-makers. However, the extent of the influence of ideologies can vary according to the political context, institutional constraints and other factors.

The three types of ideas mentioned by Goldstein and Keohane - normative representations, causal representations and worldviews - can all contribute to the creation of policy:

- Normative representations refer to the principles, values and norms that guide political actions. They define what is considered good, right or moral in the field of international relations. Normative representations can include ideas such as democracy, human rights, equality, social justice, freedom and so on. These normative ideas influence the objectives and orientations of a state's foreign policies, as well as the choices it makes on the international stage.

- Causal representations refer to beliefs about cause-and-effect relationships in international relations. They involve ideas about the factors that determine political outcomes and the behaviour of international actors. For example, some causal ideas may consider that international conflicts are mainly caused by economic factors, while others may favour explanations based on political or cultural factors. Causal representations shape politicians' and policy-makers' understanding of global problems and influence the policies they implement in response to these problems.

- Worldviews, on the other hand, represent broader frameworks that encompass both normative and causal representations. They provide a holistic view of how the world works, integrating ideas about values, causes and consequences into a coherent system. Worldviews can be ideological, cultural, religious or philosophical, and they play a major role in shaping foreign policy. They determine a state's priorities, alliances, strategies and political choices on the international stage.

Ideas, whether in the form of normative or causal representations or worldviews, are key elements influencing the formulation and implementation of foreign policies. They shape the objectives, orientations, choices and behaviour of political actors in the field of international relations.

Principled beliefs[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Normative representations, also known as principled beliefs, provide criteria for making distinctions between what is considered right, good, moral or ethical as opposed to what is considered wrong, bad or immoral. These normative ideas are based on principles, values and standards that guide the moral and ethical judgements of a society or an individual. They provide an evaluative framework for determining desirable actions and policies in different areas of life, including the political sphere. These normative representations may vary from one culture to another and from one ideology to another, reflecting differences in values and belief systems. They influence the way individuals and societies evaluate and make decisions about political, social and moral issues.

Normative representations, or principled beliefs, are assumptions or beliefs about how the world should be and what actions should be taken. They provide a criterion for drawing distinctions between what is considered good and what is considered bad, just or unjust, desirable or undesirable. These normative representations are rooted in principles, values and moral standards that guide the choices and actions of individuals and societies. They express ideals and aspirations about human behaviour, justice, fairness, freedom, equality and other fundamental values. Principled beliefs influence the way individuals assess situations, make decisions and formulate policies, seeking to align actions with the moral standards and ideals they consider to be the most just and appropriate.

The statement "I believe that slavery is not humane" expresses a clear normative representation. It draws a distinction between what is considered human and what is not, and indicates that the action to be taken should be the abolition of slavery. This normative representation is based on a moral assessment that slavery is unjust, immoral and contrary to human dignity. It reflects the belief that all people should be free and equal, and that slavery runs counter to these principles. This normative representation can serve as a basis for justifying and promoting political action to end slavery and to establish social and legal norms that protect people's fundamental rights.

Even if two people share a similar worldview, it is quite possible to have different normative representations. Normative representations are influenced by many factors such as culture, individual values, education, personal experiences and social contexts. Consequently, even within a common ideology or worldview, individuals may interpret and apply these principles differently, which can lead to divergent normative representations. For example, two people who share a liberal worldview may have different positions on specific issues such as abortion, gay marriage, economic interventionism, etc. Their normative representations may be influenced by their ideology or worldview. Their normative representations may be influenced by individual nuances, different priorities or varying interpretations of fundamental liberal principles.

This diversity of normative representations is an inherent feature of the complexity of human thought and social interaction. It reflects the plurality of perspectives and opinions within a society. The debates and discussions that emerge from these differences can be essential for democracy and for reaching political compromises and solutions that reflect the aspirations and needs of diverse groups and individuals. It is therefore important to recognise that normative representations can vary despite shared worldviews, and this can influence policy formulation and the way in which different ideas are implemented in practice.

Causal beliefs[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Causal representations are suppositions or beliefs about how the world works, with the emphasis on cause-and-effect relationships. They seek to explain why certain situations, events or phenomena occur, by identifying the factors behind them.

Causal representations play a crucial role in policy formulation, as they provide explanations of social, economic and political problems, as well as possible solutions. They influence the understanding of cause-and-effect relationships and help to assess the likely consequences of policy actions. For example, a causal representation may assert that poverty is mainly caused by structural economic inequalities. This belief can lead to policies to redistribute wealth and promote social equity. Another causal representation may hold that violence is the result of the disintegration of family structures, which could steer policies towards measures to support families and strengthen community ties.

Causal representations may vary according to ideological perspectives, research paradigms and individual experiences. Different interpretations of causal relationships can lead to divergent policy approaches, which underlines the importance of debate and discussion in reaching consensus on the best actions to take. Causal representations are based on assumptions and may be subject to errors of judgement or cognitive biases. It is therefore essential to rely on solid empirical evidence and rigorous analysis to assess the validity of causal representations and to guide the formulation of policies based on these beliefs.

Causal representation focuses on causal and economic relationships and can be used, for example, to explain why slavery is considered wrong. The belief is that slavery is not economically efficient and that it leads to violence. Consequently, economic considerations of productivity and efficiency become reasons for getting rid of the slave system and adopting other, more efficient means of production. This causal representation highlights the role of economic motivations in understanding and evaluating social and political practices. It underlines the idea that economic efficiency can be a determining factor in the questioning and rejection of certain practices, even though ethical and moral considerations may also be present.

Different causal representations can be formulated to explain why slavery is considered wrong, and these may vary according to individual perspectives, historical contexts and conceptual frameworks. Causal representations may be influenced by a combination of economic, social, moral and cultural factors, and different people may attach more or less importance to each of these elements. Ultimately, causal representations contribute to our understanding of the causes and consequences of social and political phenomena, and can influence policy decisions and actions taken to promote change and social improvement.

World Visions[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Worldviews are systems of thought and belief that encompass both causal and normative representations. They provide a comprehensive and coherent perspective on how the world works, integrating values, principles, causal beliefs and political objectives. Worldviews are often influenced by ideologies, cultural, religious, philosophical or political perspectives, and they shape the way individuals and societies understand and interpret the reality around them. They can influence attitudes, behaviours and policies in a variety of areas, including foreign policy, economics, social issues, etc.

For example, a liberal worldview may be based on causal representations that emphasise the importance of individual rights, freedom and the free market in promoting prosperity and human flourishing. In normative terms, this worldview may support principles such as equality of opportunity, the protection of human rights and the primacy of individual freedom. Similarly, a conservative worldview may draw on causal representations that emphasise the importance of tradition, social order and stability in maintaining cohesion and continuity. It may be guided by principles such as the preservation of moral and cultural values, respect for authority and the promotion of social order.

Worldviews can vary considerably from one person to another, depending on various factors such as education, experience, cultural influences and individual values. They can give rise to differences of opinion and debate on political, economic and social issues. Ultimately, worldviews play a fundamental role in shaping political attitudes, assessing problems and formulating policies. They provide a conceptual framework and ideological orientation that influence a society's political choices and decisions.

Culture plays a fundamental role in determining individual values and perceptions of reality. Culture is a set of norms, beliefs, values, traditions, behaviours and meanings shared within a community or society. It shapes the way people see and understand the world around them. Values are central to culture. They represent what is considered important, desirable and right within a given society. Cultural values can vary from one society to another, influencing people's attitudes and behaviours towards different aspects of life such as family, religion, work, education, politics, and so on. For example, some cultures may value cooperation and social harmony, while others may place greater emphasis on individualism and competition. Culture also influences perceptions of reality. Cultural values, beliefs and norms provide an interpretative framework that influences how individuals perceive and understand their environment. Culture determines the patterns of thought, frames of reference and expectations that guide the way individuals interpret information, evaluate situations and make decisions. Consequently, cultural differences can lead to different interpretations and understandings of reality, even in similar situations. Culture is not static and evolves over time. Interactions between individuals, external influences, social changes and historical developments can lead to cultural transformations. However, culture remains a powerful factor influencing the values and perceptions of individuals, as well as collective behaviour within a society. Understanding cultural diversity and its impact on values and perceptions is essential for effective intercultural communication and for understanding the differences and similarities between societies.

Religions provide a framework of beliefs, practices and values that give meaning to human existence and to the relationship between human beings and the divine. On the one hand, religions offer normative representations by setting out moral, ethical and spiritual teachings that guide the behaviour and actions of their followers. These normative representations include principles of conduct, moral precepts and codes of behaviour based on divine values and prescriptions. For example, the Ten Commandments in Christianity or the Five Pillars of Islam set out normative principles that guide believers in their daily lives.

On the other hand, religions propose causal representations, providing explanations of the origin and functioning of the universe and the human condition. They offer interpretations of cause-and-effect relationships and divine designs. For example, some religions may teach that human actions are linked to karmic consequences, while others may explain natural events in terms of divine will or cosmic forces. Religions are therefore complete worldviews that encompass both normative and causal representations. They provide a spiritual, moral and philosophical framework that influences the understanding of reality, moral conduct and political and social choices of individuals and religious communities. However, it is important to note that religious interpretations and practices can vary within different religious traditions, which can give rise to a diversity of expressions and understandings within the same religion.

In the Catholic perspective of Christianity, there are both normative and causal representations that influence their position on issues such as euthanasia and abortion. From a normative point of view, the Catholic vision considers human life to be sacred and a gift from God. Consequently, euthanasia and abortion are considered to run counter to these fundamental values. According to the teachings of the Catholic Church, human life must be protected and respected from the moment of conception until its natural end. Thus, euthanasia, which deliberately involves ending a person's life, is considered a violation of this intrinsic value of human life. From a causal point of view, Catholic belief is based on the conviction that God is the creator of life and its sole owner. This causal representation influences the Catholic position that the act of ending human life, whether through euthanasia or abortion, is tantamount to arrogating to ourselves a power that does not belong to us. The causal vision emphasises humanity's relationship of dependence on God as regards the origin and purpose of life. These normative and causal representations have a profound influence on the Catholic Church's position on euthanasia and abortion. They guide the ethical and moral reflection of Catholics, as well as the Church's official positions on these issues. However, it is important to note that these positions may be subject to interpretation and debate within the Catholic community, and there may be diversity of opinion among the faithful.

Max Weber, an early 20th century German sociologist, developed a theory on the link between religion, particularly Protestantism, and economic development. In his book "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism", Weber argues that the religious values and beliefs of Protestantism, particularly the Calvinist branch of Protestantism, have played an important role in promoting capitalism and economic development. According to Weber, the Protestant ethic, characterised by principles such as hard work, frugality, discipline and the pursuit of material success, fostered the emergence of an entrepreneurial spirit and a mentality focused on the accumulation of wealth. Calvinist Protestants believed in predestination, according to which God had already chosen those who would be saved and those who would be condemned. To prove their divine election, Calvinists emphasised material success as a sign of divine favour. This encouraged them to work hard, save and invest in economic activities, thus contributing to the development of capitalism and economic growth. However, it should be noted that Weber's theory has given rise to debate and criticism over time. Some scholars have questioned the scope and universality of his conclusions, pointing out that other economic, social and historical factors must also be taken into account when explaining the economic development of countries. Despite this, the idea that religious beliefs can influence economic behaviour and economic development continues to be a subject of study and debate within the social sciences. There are a variety of complex factors that contribute to the economic trajectory of countries, and religion can play a role among other cultural, political, institutional and economic influences.

Ideologies can contain both normative elements (ethical principles and values) and causal elements (explanations of cause-and-effect relationships) as well as philosophical principles. Ideologies provide a systematic and coherent framework of thought that guides the understanding of reality, moral judgements, causal explanations and political objectives.

The ethical and normative principles of an ideology determine what is considered right, good, moral or desirable. They guide actions and policies by proposing standards of conduct, values and social objectives. For example, a liberal ideology may advocate individual freedom, equality of opportunity and the protection of human rights as fundamental ethical principles. These normative principles will influence the political positions adopted by this ideology.

The causal principles of an ideology seek to explain cause-and-effect relationships in different social, economic or political fields. They provide interpretations of the causes of problems and the consequences of actions. For example, a socialist ideology may argue that economic inequality is caused by the structures of capitalism, while a liberal ideology may emphasise the principles of free markets and competition as factors promoting economic growth.

Ideologies can also incorporate philosophical principles, such as conceptions of human nature, ideas about justice, ethics and the role of the state. These philosophical principles provide a broader conceptual framework that gives general direction to the ideology and influences its political positions. Ideologies may differ in their ethical, causal and philosophical principles. Different ideologies may have divergent views on how the world should be, what the causes of social problems are and what the appropriate solutions are. Debates between ideologies often reflect differences over these fundamental principles.

An ideology provides both a vision of reality as it is perceived and a vision of the ideal future society as it should be according to that specific ideology. An ideology offers an interpretation of current social, economic and political reality, highlighting the problems, conflicts and inequalities that exist. On the other hand, an ideology also proposes a vision of the ideal future society. This ideal vision is generally based on the ideology's ethical principles, values and objectives. It represents an aspiration towards a better society that meets the needs, values and ideals defended by that specific ideology. This means that ideologies are often oriented towards a project of social transformation, seeking to influence policies and actions to achieve this ideal vision of society. For example, a progressive ideology may aim to promote social equality, economic justice and inclusion, and propose policies and actions to achieve this.

Visions of the ideal future society can vary considerably between different ideologies. Ideal visions are influenced by the specific values, principles and goals of each ideology. As a result, there can be significant divergences in proposals and conceptions of the ideal society between different ideologies. Ideologies play an important role in formulating visions of reality and of the ideal future society. They provide conceptual frameworks and political orientations that influence the discourses, policies and actions of individuals, groups and political movements.

Scientific rationality and scientific knowledge play an important role in understanding the world and shaping worldviews. Science seeks to make the world intelligible by providing explanations based on verifiable observations, data and theories. It relies on rigorous methods and logical reasoning processes to explore and explain observable phenomena. In this context, the scientific view of the world is often characterised by an approach based on causal representations and rational explanations of natural and social phenomena. Scientists seek to identify the causes and mechanisms underlying phenomena, using theories and models that are constantly challenged and improved in the light of new data and discoveries.

However, even in science, normative elements can be present. Normative beliefs such as Enlightenment humanism and faith in progress can influence the orientations and values that guide scientific research and technological applications. These normative beliefs can be important underpinnings for motivating and guiding scientists in their efforts to understand and transform the world. Science itself is influenced by social, cultural and political factors. Research choices, priorities, funding and applications of science can be influenced by normative considerations and societal values. The ethical debates surrounding issues such as stem cell research, genetic manipulation and artificial intelligence are examples of this. The scientific view of the world is based on the principles of rationality, the search for causes and empirical explanations. However, normative elements may also be present, influencing the values, orientations and applications of science. The combination of causal and normative representations in the scientific vision contributes to the formation of worldviews and the understanding of observed phenomena.

Ideologies in Political Science[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Ideologies are systematic, organised and coherent bodies of knowledge made up of philosophical, ethical and causal principles that help us to understand, evaluate and act in the world. They provide a framework for interpreting and assessing social, economic and political reality. Ideologies are often adopted by groups of people to give meaning to their social experience and to guide their collective action.

Ideologies can manifest themselves in a variety of fields, such as politics, economics, religion, education and so on. They can also be centred around different issues, such as equality, freedom, justice, authority, property, identity, etc. For example, capitalism and socialism are two economic ideologies with different perspectives on the ownership and distribution of resources. Capitalism values private property and the market economy, while socialism values collective property and economic equality.

Ideologies can also influence the way individuals and groups perceive and interact with others. For example, a racist ideology might lead to discrimination and inequality, while a feminist ideology might promote gender equality. Ideologies are not static; they evolve over time and according to context. Moreover, it is not uncommon for individuals and groups to adopt elements of several ideologies, creating hybrid or composite ideologies.

Finally, it is also crucial to understand that ideologies can have both positive and negative consequences. They can inspire positive action, such as the struggle for equality and justice, but they can also justify oppressive and discriminatory behaviour. Consequently, the critical study of ideologies is an important task in many disciplines, including sociology, political science, philosophy and psychology.

Normative representations and their impact[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Normative representations are collective ideas or beliefs that describe how things should be, rather than how they actually are. They involve value judgements and standards of conduct that guide action and evaluation. They are closely related to the notion of norms, which are shared rules or expectations that govern behaviour in a society. For example, in many societies there is a normative representation that people should be treated fairly, regardless of their race, gender, religion or ethnic origin. This normative representation is often codified in anti-discrimination laws and promoted by human rights organisations.

In the political sphere, normative representations can take the form of ideologies, such as democracy, liberalism, socialism, etc. These ideologies provide normative models for the organisation of society and the functioning of government. Normative representations may vary from one culture to another and may evolve over time. Moreover, they may be the subject of debate and contestation, as different individuals and groups may have different views of what is desirable or acceptable. Finally, normative representations can have a significant influence on individual and collective behaviour. For example, they can encourage people to act ethically, support social causes, obey the law and so on. They can also influence the policies and decisions of governments and international organisations.

Normative ideas and representations can significantly influence the preferences and power of groups and states. Here are some of the ways in which this can happen:

- Definition of interests and objectives: Normative ideas and representations can help define the interests and goals of groups and states. For example, an economic ideology such as capitalism may lead a state to favour policies favouring the free market, while an ideology such as socialism may lead a state to favour policies favouring the redistribution of wealth.

- Identity formation: Ideas and normative representations can contribute to the formation of the identity of groups and states. This identity can in turn influence their preferences and power. For example, the idea of democracy can reinforce a state's identity as 'free' and 'just', which can give it legitimacy and influence on the international stage.

- Influence on behaviour: Normative ideas and representations can influence the behaviour of groups and states. For example, the idea of human rights may encourage a state to respect certain standards of behaviour, while a belief in the supremacy of a race or religion may encourage discriminatory or aggressive behaviour.

- Resource mobilisation: Normative ideas and representations can help mobilise resources for a group or state. For example, a nationalist ideology can generate popular support for a government, thereby strengthening its power. Similarly, a feminist ideology can help mobilise resources for gender equality.

- Coalition building: Ideas and normative representations can help to build coalitions. Like-minded groups or states can band together to achieve common goals, thereby strengthening their power.

How ideas and normative representations influence the preferences and power of groups and states depends on many factors, including historical, cultural and political context. Analysing these influences, therefore, requires a nuanced and contextual approach.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a fundamental document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives of different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the UDHR was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (Resolution 217 A) as a common standard to be achieved by all peoples and all nations. The Declaration sets out, for the first time, the fundamental human rights to be universally protected. It consists of 30 articles describing civil and political rights (such as the right to life, liberty, security, a fair trial, freedom of expression, thought, religion, etc.), as well as economic, social and cultural rights (such as the right to work, education, health, an adequate standard of living, etc.).

The UDHR was adopted in the aftermath of the Second World War, a period marked by a growing awareness of the horror of war crimes and genocide. The Declaration represented the hope that such events would never happen again and the commitment of the world's nations to respect and protect the dignity and rights of all individuals. The UDHR has become the basis for many international human rights treaties and continues to influence national laws and international policies. Although it is not a treaty in itself, and therefore technically non-binding, many provisions of the UDHR have been incorporated into other international treaties that are legally binding. In addition, some provisions of the UDHR are considered part of customary international law, which is binding on all states.

The post-Second World War era saw a major shift in the way the international community viewed human rights and state sovereignty. The atrocities committed during the war, including the Holocaust, revealed the dangers of allowing states to act with impunity within their borders. According to Kathryn Sikkink, a specialist in international relations, this shift in normative representations has led to a "justice cascade" in which international human rights standards have begun to influence national policy. Sikkink suggests that the adoption of and adherence to these standards has created a domino effect, where the pressure to respect human rights has spread to more and more countries.

The principle of the international community's shared responsibility to protect human rights means that human rights violations are no longer seen as a matter of exclusive national sovereignty. States have an obligation to respect the human rights of their citizens, but the international community also has a collective responsibility to prevent human rights violations. This led to the creation of international organisations such as the United Nations, and later the International Criminal Court, to monitor and act against human rights violations. Human rights standards are now codified in international treaties, and states that fail to meet these standards can be subject to international pressure and sanctions.

The post-war emphasis on human rights has influenced the way in which states perceive their long-term interests and political preferences. This influence can be seen in a number of ways:

- Recognition of legitimacy: States have begun to understand that respect for human rights is essential to their legitimacy on the international stage. States that systematically violate human rights can be considered international pariahs, which can lead to diplomatic isolation, economic sanctions or even military intervention. In contrast, states that respect human rights are more likely to benefit from favourable international relations, foreign aid and trade.

- Internal stability: States have also begun to understand that respect for human rights is crucial to their internal stability. Violations of human rights can lead to social conflict, rebellion and even revolution. On the other hand, respect for human rights can contribute to social cohesion, confidence in state institutions and civil peace.

- Political preferences: Human rights have also influenced the political preferences of states. For example, liberal democracies tend to value civil and political rights, while socialist states may emphasise economic and social rights. Human rights preferences can influence a range of policies, from domestic legislation to international treaties.

- Human rights networks: Finally, states have begun to participate in transnational human rights networks, which can influence their interests and preferences. For example, states may join international human rights conventions, support human rights non-governmental organisations (NGOs), or work with other states to promote human rights.

These changes did not happen overnight, and not all states adopted human rights in the same way. Nevertheless, it is clear that ideas about human rights have played a crucial role in shaping world politics since the Second World War.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) is a key institution for the protection of human rights in Europe. It was established in 1959 in Strasbourg, France, by the Council of Europe, an international organisation dedicated to promoting human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. The ECHR is responsible for applying the European Convention on Human Rights, an international treaty that establishes a series of fundamental rights that all signatory states are obliged to respect. These rights include, among others, the right to life, the right to a fair trial, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of expression, and the right to respect for private and family life. One of the unique aspects of the ECHR is that it allows individuals, non-governmental organisations and groups of people to bring applications directly to the Court if they believe that their rights, as guaranteed by the Convention, have been violated by a Member State. This is highly unusual, as in most international legal systems, only States can lodge complaints against other States. States may also lodge applications against other States if they believe that there has been a violation of the Convention. When the Court receives an application, it first examines whether it is admissible. If it is, the Court then examines the merits of the case. If it finds a violation, the Court may ask the State to take steps to remedy the situation. The Court's judgments are legally binding. The ECHR plays a crucial role in promoting and protecting human rights in Europe. Through its decisions, it has helped to develop and clarify human rights standards, and to ensure that states respect their human rights commitments.

Human rights are considered inalienable and universal, which means that they cannot be suppressed or neglected under any circumstances, including in the context of the fight against terrorism. After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, for example, many countries stepped up their security measures and introduced stricter anti-terrorism laws. However, these measures raised concerns about respect for human rights. It has become clear that the fight against terrorism must be conducted with respect for human rights and the rule of law.

The idea is that even in times of crisis or threat, states are obliged to respect the fundamental rights of their citizens. Governments cannot invoke national security or the raison d'état to justify human rights violations. This is reflected in various international human rights documents. For example, Article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights states that certain rights are inalienable and may not be restricted, even in time of war or other public emergency. Similarly, Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides that certain restrictions may be imposed in times of crisis, but also specifies that certain rights, such as the right to life and the right not to be subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment, may never be restricted.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, and particularly since the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, there has been a fundamental shift in the way states view their responsibilities to their citizens and to the international community. This shift has been from a narrow conception of national interests to a broader one that includes respect for human rights as an essential component of state legitimacy and security. This is not to say that tensions between human rights and national security have disappeared. In certain situations, particularly where there is a serious threat to national security, such as terrorism, some states may be tempted to restrict human rights in the name of security. However, it is increasingly recognised that security cannot be sustained without respect for human rights, and that human rights violations can in fact contribute to instability and insecurity. Furthermore, the development of international human rights law has created mechanisms through which human rights violations can be exposed and sanctioned, thereby increasing the cost to States of failing to respect human rights. As a result, while some states may sometimes be tempted to violate human rights, they may also see that respecting these rights is in their long-term interests. This shift in preferences and interests has not been uniform across all states and regions. There are still significant differences in how different states and cultures view human rights, and how they balance these rights with other priorities. However, the emergence of international human rights standards has certainly had a profound impact on the way states view their role and responsibilities.

Representations, or the way in which ideas and beliefs are formulated and shared, can have a significant influence on the political power of agents, be they individuals, groups or states. Here are a few ways in which this can happen:

- Formation of public opinion: Representations can shape public opinion, which in turn can influence political decisions. For example, the way in which the media present a particular issue can influence the way in which the public understands it, which in turn can influence the pressure the public exerts on politicians to act in a certain way.

- Legitimacy: Representations can also influence the perceived legitimacy of a political actor. For example, a leader who is perceived as defending the values and interests of his community is more likely to be seen as legitimate, which can strengthen his political power.

- Mobilisation: Representations can help mobilise support for a cause or political movement. For example, speeches and symbols can be used to inspire people to take action.

- Alliance formation: Representations can also influence the way in which political actors form alliances. For example, states that share common values or goals, as represented in their rhetoric and policies, are more likely to work together to achieve these goals.

- International norms: At the international level, representations can influence the creation and adoption of international norms, which in turn can influence the behaviour of states and other actors.

While representations can influence political power, the process is also reciprocal. Political actors often use representations to reinforce their power, for example by using speeches and symbols to mobilise support or by using propaganda to influence public opinion.

The American Civil War, also known as the American Civil War, was a major conflict between the Northern States (the Union) and the Southern States (the Confederate States) that took place from 1861 to 1865. Disagreement over the issue of slavery was a key factor that led to the war. The Northern States, industrialised and largely anti-slavery, supported policies to limit the expansion of slavery in the new territories of the United States. Abraham Lincoln, elected President in 1860, was a member of the Republican Party, which was firmly opposed to the expansion of slavery. The Southern states, on the other hand, were heavily agricultural and depended on slavery as a key component of their economy and way of life. They saw efforts to limit the expansion of slavery as a threat to their states' rights and autonomy. When Lincoln was elected, several Southern states responded by seceding from the Union to form the Confederate States of America. Soon after, war broke out. While the war was not started solely because of slavery, it was this issue that became the focus of the conflict. In 1862, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared slaves in the Confederate States free. Although this proclamation did not immediately free all slaves, it changed the character of the war by making the abolition of slavery an explicit war aim of the Union.

After the Civil War, the political dynamics of the United States were largely defined by the regional and economic differences between North and South, as well as by the rapid industrialisation of the country. The Republicans of this era were the party of the urban industrial areas of the North and Midwest, but it was they who generally favoured high tariffs, not the Democrats. Tariffs were seen as a way of protecting fledgling Northern industries from foreign competition. The Democrats, on the other hand, were generally associated with the rural and agrarian South, which depended heavily on the export of agricultural products and was therefore generally in favour of free and open trade. Over time, however, these alignments changed. From the 1930s and especially after the 1960s, the Democratic Party became more associated with urban and industrial interests and civil rights, while the Republican Party became more associated with rural and agricultural interests and a more conservative approach to social issues. This shows how political representations and alignments can evolve and transform over time, often in response to changes in the economic and social structure of society.

The American Civil War was a pivotal moment in the history of the United States and strengthened the legitimacy of the abolitionist movement. Abolitionist ideas went from being radical positions to being more widely accepted. This change occurred partly because of the events of the war itself and partly because of the efforts of abolitionists who worked tirelessly to change attitudes towards slavery. After the war, the Republicans, Abraham Lincoln's party, became dominant in American politics for a period, especially in the North and Midwest. The Republicans sought to introduce policies to support the rapid industrialisation taking place in these regions, including protectionist tariffs to help infant industries develop. These policies were widely supported by urban workers and capitalists in the North, who saw protectionism as a way of protecting their interests. In this way, the victory of the Republicans and their ability to implement protectionist policies strengthened their legitimacy and political power.

Causal representations: Definition and Effects[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The influence of causal representations on the actions and strategies of states and groups[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

"Analogies at War: Korea, Munich, Diên Biên Phu, and the Vietnam Decisions of 1965" is a highly influential book written by Yuen Foong Khong. In it, Khong focuses on the importance of historical analogies in the decision-making process, particularly in relation to foreign policy.[2] Khong argues that political leaders often rely on analogies to past events to understand and make decisions about current issues. These analogies can help leaders make sense of complex situations, identify possible options and justify their actions to a wider audience. However, Khong also notes that these analogies can be misleading or inaccurate, and can lead to errors of judgement. For example, he argues that US leaders erred during the Vietnam War by relying too heavily on the Munich analogy - the idea that any form of appeasement would inevitably lead to aggression. This book has been widely acclaimed for its contribution to our understanding of how political leaders make foreign policy decisions. It highlights the importance of ideas and beliefs in the decision-making process and shows how lessons from history can both illuminate and obscure our understanding of current challenges.

Historical analogies often play a central role in the political decision-making process, especially when it comes to foreign and security policy issues. They help decision-makers to make sense of complex or ambiguous situations and to deduce patterns from past events that can be applied to the current situation. However, it is important to note that the use of historical analogies also carries risks. Firstly, analogies can be misleading or inaccurate. Historical events are rarely identical and the differences between situations can be just as important as the similarities. Relying on an incorrect or inappropriate analogy can therefore lead to errors of judgement. Furthermore, analogies can limit the options perceived by decision-makers. If a certain approach has worked in the past, decision-makers may be tempted to apply it again, even if the situation has changed or other options might be more effective. In this sense, analogies can sometimes get in the way of creative or innovative thinking. Finally, it is important to remember that historical analogies are often used to justify or explain decisions after the event. This means that they can be used to defend decisions that were made for other reasons, or to persuade others to support a certain policy. While historical analogies can be a valuable tool for understanding and navigating policy challenges, they must be used with caution and discernment.

Yuen Foong Khong, in his book "Analogies at War", argues that human intelligence often operates by analogy, i.e. it draws connections between past and present events to facilitate understanding and decision-making. These analogies enable decision-makers to make sense of new or complex situations by relating them to previous events or experiences. For example, a leader might compare a current diplomatic crisis to a similar crisis in the past, to understand what worked and what didn't work then, and how those lessons can be applied to the current situation. However, Khong also warns of the dangers of using historical analogies. If misused or misunderstood, analogies can lead to errors of judgement or misinterpretation of the current situation. Therefore, although analogies can be a valuable decision-making tool, they must be used with discernment and a clear understanding of the differences between past and present situations.

The term "Munich analogy" refers to the policy of appeasement adopted by the European powers towards Nazi Germany in the years leading up to the Second World War. The Munich Conference in 1938 resulted in an agreement in which Britain and France essentially allowed Germany to annex parts of Czechoslovakia in the hope of avoiding a wider war. This policy of appeasement proved disastrous as Germany continued its aggressive expansion, eventually triggering the Second World War. In 1950, when the decision was taken to commit the US to Korea, the Munich analogy played a significant role in President Harry Truman's thinking. For Truman and many others, the Munich experience reinforced the belief that unchecked aggression would only encourage further aggression. This lesson from Munich was applied to the situation in Korea, with the belief that the US had to oppose North Korea's invasion of South Korea to avoid a widening of the conflict. However, as Yuen Foong Khong points out, the application of this analogy can be problematic. The situations in Korea and Munich were different in many respects, and over-reliance on a historical analogy can lead to errors of judgement. In the case of the Korean War, this analogy may have led to an underestimation of the costs and difficulties of the war, and an overestimation of the risks of non-intervention.

Recalling the lessons learned from the policy of appeasement that preceded the Second World War, American leaders, including President Harry Truman, concluded that any form of aggression must be countered quickly and decisively to avoid future escalation. The Munich analogy was therefore a key factor in the US decision to intervene militarily in the Korean War in 1950. Truman and others felt that by not responding to North Korea's invasion of South Korea, they would have given the aggressor (in this case, the Communist-backed North) an implicit signal that future aggression would be tolerated. However, it is important to note that while historical analogies can provide useful guidance, they can also be misleading if applied too strictly or without taking into account the contextual differences between past and present situations. Over-reliance on a particular analogy can lead to errors of judgement, as Yuen Foong Khong points out in his work.

The situation in Southeast Asia had become increasingly complex and worrying for the United States by the mid-1960s. Since the beginning of John F. Kennedy's presidency in the 1960s, the United States had become increasingly involved in the region, particularly in Vietnam, where it supported the government of the South against the communist forces of the North. The situation in Laos, a neighbouring country of Vietnam, was also a source of concern. The country was in the grip of a civil war involving communist and non-communist factions, and there was a growing fear that communism would spread throughout the region, a concept known as the 'domino theory'. In 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson took the decision to step up the US military commitment in Vietnam, these concerns were at the forefront of his thinking. Johnson and his advisers feared that withdrawal or perceived weakness would encourage Communist expansion, not only in Vietnam and Laos, but also in other countries in the region. Again, the Munich analogy played a part in their thinking, reinforcing the idea that the best way to deal with aggression was to counter it firmly. However, as we know with hindsight, the Vietnam War proved costly and controversial, and the US eventually withdrew its forces without having achieved its main objectives. This highlights once again the limitations and potential dangers of applying historical analogies to political decision-making.

In 1965, faced with the deteriorating situation in Vietnam, President Lyndon B. Johnson and his advisers were faced with two main options:

- Stay the course with limited involvement in the region: This option would have allowed the policy of supporting South Vietnamese forces to continue, while limiting the direct involvement of US troops. It was essentially a continuation of the strategy that had been put in place by the previous Kennedy administration.

- Deploy new military forces and escalate: This option would have involved a much deeper commitment, with the deployment of large numbers of US troops and an increase in military operations against North Vietnamese forces. It was a more aggressive option, which would have marked a significant departure from previous policy.

These two options represented very different approaches to managing the crisis in Vietnam, and the choice between them had major implications for the future of US involvement in the region. As we know with hindsight, Johnson ultimately opted for military escalation, a decision that had lasting and controversial consequences.

Johnson had five options which can be grouped into two broad strategic orientations: the status quo and military escalation. Each of these options had its advantages and disadvantages, and reflected different visions of what was needed to protect US interests in Southeast Asia.

- Status quo: This option would have involved continuing the existing strategy, with continued support for South Vietnamese forces and limited US troop involvement. This could have limited the costs and risks for the US, while maintaining a presence and influence in the region.

- Military escalation: This option would have involved a much deeper commitment, with several possible variants: a. Sending a contingent of 100,000 troops: This option would have marked a significant increase in the direct involvement of US troops, with all the additional costs and risks that this entails. b. Increase air power: This option could have allowed military operations against North Vietnamese forces to be stepped up without such a major commitment on the ground. c. Call up military reservists and declare a national emergency: This option would have been the most radical and would have represented the deepest US involvement in the conflict.

As we now know, Johnson ultimately opted for military escalation, a decision that had profound implications for the course of events in Vietnam and for US foreign policy in general.

In discussing how to respond to the situation in Vietnam, Johnson's advisers were divided. Some argued that military escalation was necessary to counter Communist aggression, citing the Munich analogy - the idea that appeasement would encourage future aggression - to support their view. However, another adviser took a more cautious stance, recommending a status quo approach rather than military escalation. This approach was supported by the analogy of Diên Biên Phu, a reference to the defeat of French forces by the Viet Minh in 1954 during the Indochina War. This battle is often cited as an example of how a technologically superior military force can be defeated by a well-organised and motivated guerrilla force, despite its apparent superiority in terms of equipment and resources. This analogy was used to warn of the potential dangers of military escalation in Vietnam, suggesting that greater intervention might not lead to success and might even make the situation worse. As we know with hindsight, this warning proved prophetic, as military escalation led to a long and costly war that did not result in a clear victory for the United States.

The position of the fourth advisor, advocating a more cautious approach or the status quo, was less attractive for several reasons. Firstly, he was in a minority, compared to the other three advisers who supported military escalation. Secondly, its analogy with the French defeat at Diên Biên Phu could be seen as devaluing American military power. Leaders, in general, tend to favour arguments that reinforce their worldview and sense of efficacy, and in this context, arguments in favour of military escalation may have been more convincing. Furthermore, it is important to note that political decisions are rarely taken solely on the basis of rational and objective assessments of the situation. Factors such as internal political pressures, public image, personal prejudices and long-term strategic considerations also play a major role. In the case of Johnson's decision to escalate the Vietnam War, all these factors probably influenced the final outcome.

Yuen Foong Khong, in his book "Analogies at War: Korea, Munich, Diên Biên Phu, and the Vietnam Decisions of 1965", examined how historical analogies influenced decision-making during the Vietnam War. He argued that these analogies played a crucial role in the way President Johnson and his advisers assessed the situation and made their decisions. The Munich analogy, for example, probably helped reinforce the idea that military escalation was necessary to avoid the domino effect - the fear that if one country fell to communism, others would follow. The Diên Biên Phu analogy, on the other hand, has served as a warning of the dangers of military escalation, but has been less heeded. This analysis highlights how lessons learned from the past can influence decision-making in the present, and how different interpretations of history can lead to different conclusions about how best to respond to a crisis.

President Johnson ultimately chose to escalate the US military commitment in Vietnam, partly because of the influence of the Munich analogy. He sent an additional 100,000 troops, beginning a deeper and longer US involvement in the conflict. Unfortunately, this decision led to a war that lasted almost a decade and cost the lives of thousands of American soldiers, not to mention the considerable civilian casualties in Vietnam. The conflict also significantly impacted American society, provoking deep divisions and massive protests against the war. This shows how normative representations, in the form of historical analogies, can profoundly impact political and military decisions. In this case, the Munich analogy may have led to an overestimation of the threat posed by North Vietnam and an underestimation of the difficulties of military engagement in the region, contributing to the escalation of a costly and controversial conflict.

Yuen Foong Khong argued that the Munich analogy strongly influenced President Johnson and his advisers, leading them to rule out certain options and favour military escalation. By focusing on the need to contain communism (the lesson of Munich), they may have overlooked other important lessons, such as France's failure at Diên Biên Phu. Khong is not alone in criticising this decision. Many historians have questioned the wisdom of escalating American involvement in Vietnam. However, it is important to note that foreign policy decision-making is complex and depends on many factors, some of which may not be obvious retrospectively. The importance of Khong's analysis lies in his demonstration of the impact of historical analogies on decision-making, even though these analogies may not always be accurate or appropriate.

The role of causal representations in the structuring of political power[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Neoliberal ideology and its logic of "There Is No Alternative" (TINA) have a significant impact on the distribution of power, both nationally and internationally. When a causal idea such as neoliberalism becomes dominant, it can give rise to asymmetries of power.

Social globalisation, characterised by increased cross-border dissemination of information via the media and the internet, has an impact on people's perceptions of their position in the global economy. Workers in rich countries may feel threatened by international competition and the relocation of production. These factors can exert downward pressure on wages and working conditions, and increase job insecurity. What's more, the notion of flexibility has become a central labour issue in the age of globalisation. Employers often demand greater flexibility from workers, in terms of working hours, skills and the ability to adapt to new technologies or working practices. Increased international competition can also lead workers to accept more flexible working conditions in order to keep their jobs. Consequently, social globalisation, by circulating information about the global economy, can change workers' perceptions and attitudes towards international trade and the multinationalisation of production. This can affect power dynamics in the world of work, and potentially reinforce socio-economic inequalities.

Globalisation has created a more competitive business environment. As a result, many employers feel they need more flexibility to remain competitive. This flexibility can manifest itself in a number of ways:

- Flexible working: Employers may ask workers to be more flexible in their working hours, often by requiring them to work outside normal hours or to adapt their hours to suit the needs of the business.

- Role flexibility: Employers can ask workers to take on a variety of tasks and roles, rather than focusing on a single specialist task. This may involve asking workers to acquire new skills or learn new technologies.

- Flexible contracts: Employers may seek to use more flexible employment contracts, such as fixed-term contracts, part-time contracts or zero-hours contracts. These types of contracts can make it easier for employers to change the number of hours they offer according to their needs.

The issue of flexible working is an important and controversial one, and France is no exception. The idea is that increasing flexibility can enable companies to be more competitive and adapt more quickly to changes in the market. However, it can also raise concerns about job security and working conditions for employees. In France, the term 'flexibility' is often associated with changes such as the relaxation of employment protection laws, the increase in part-time or fixed-term work, and the reduced involvement of trade unions in negotiations on working conditions. These reforms are sometimes perceived as a threat to workers' rights, hence the 'taboo' nature of flexibility. However, it is also important to note that flexibility does not necessarily mean a reduction in workers' rights. It is possible to increase flexibility while maintaining protections for workers. For example, some forms of 'flexicurity', a model used in countries such as Denmark, aim to balance flexibility for employers with security for workers.

The idea that globalisation and international competition require greater labour flexibility can have a powerful effect on the dynamics of employment relations, regardless of the actual material benefits of these changes. This is sometimes referred to as the 'discursive' or 'ideological' effect of globalisation. If workers are convinced that their jobs are threatened by international competition - for example, because of increased production in China and India - they may be more inclined to accept more flexible working conditions, even if these changes may lead to less job security or more precarious working conditions. This is an illustration of how ideas and beliefs can influence economic behaviour. However, this type of discourse should not be accepted uncritically. It is essential to think critically about who benefits from these changes and who is harmed, and to ensure that workers' rights are respected. Furthermore, governments have a role to play in ensuring that economic change benefits everyone, not just a small group of employers or investors.

Neoliberal ideology, with its logic of "There Is No Alternative" (TINA), postulates that in order to remain competitive in the global market, it is necessary to adopt economic measures such as reducing wages, making working conditions more flexible, liberalising trade and reducing state intervention in the economy. However, it is important to understand that this is an ideology, a way of seeing the world, and not a natural law. Other economic ideologies argue that different policies can also promote economic growth and people's well-being. For example, some economic approaches argue that investment in human capital (education, health) and infrastructure, and the introduction of regulations to protect workers and the environment, can also contribute to a strong and sustainable economy.

Interpreting the State through causal representations: Impact on the preferences of States, groups and individuals[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

An individual's identity can be defined by the many roles they occupy in society, and these different roles can influence their preferences and behaviour. For example, a person may identify as both a producer and a consumer.

- As a producer, the individual may be a worker, an entrepreneur or an investor. In this role, he tends to favour policies that promote productivity, economic growth, investment and trade. He might prefer policies that reduce taxes and regulations on business, encourage innovation and investment, and open up new markets for products and services.

- As a consumer, the individual is concerned with access to a variety of good quality products and services at affordable prices. In this role, he or she may prefer policies that protect consumer rights, regulate industries to prevent abuses of power and promote competition to keep prices down.

These two identities can sometimes come into conflict, for example when a policy favours producers at the expense of consumers, or vice versa. Individuals must then navigate between these identities to form their preferences and make decisions.

How an individual perceives themselves in terms of their identity as a producer versus their identity as a consumer can influence their views on free trade policies.

- As a producer: If the low-skilled worker in Switzerland sees himself primarily as a producer, he may see free trade as a threat. This is because opening up markets to foreign competition could lead to increased competition for their jobs, particularly if low-skilled workers from other countries are prepared to do the same work for lower pay. This could lead him to oppose free trade policies.

- As a consumer: On the other hand, if the same worker sees himself primarily as a consumer, he might view free trade more positively. This is because free trade can lead to a greater variety of goods and services being available, as well as potentially lower prices due to increased competition between suppliers. This could lead him to support free trade policies.

Naoi and Kume have studied how producer and consumer identities influence attitudes towards free trade.[3] Their research is based on the idea that individuals have both a producer identity and a consumer identity, and that these identities can be "activated" or "deactivated" in certain situations, influencing their views on free trade. In their experiments, they presented participants with different economic and political situations that called upon their identity as producer or consumer. For example, a situation focusing on the potential loss of jobs in local industry might activate an individual's producer identity, while a situation focusing on lower prices for imported goods might activate their consumer identity. They found that when an individual's producer identity was activated, they were more likely to express negative attitudes towards free trade. Conversely, when their consumer identity was activated, they were more likely to express positive attitudes towards free trade. This suggests that attitudes towards free trade may be strongly influenced by how individuals perceive themselves and their role in the economy, and that these perceptions may be influenced by external factors such as government policies and political discourses.

The idea behind Naoi and Kume's approach is to activate or remind each individual of their own identity as a producer or consumer by showing them specific images before asking questions about free trade. For the group of producers (group 1), they could show images related to production, such as a factory, workers, or agricultural fields. These images could remind people of their own experience as workers and therefore activate their identity as producers. The consumer group (group 2) could show images related to consumption, such as a shopping centre, consumer products, or a family shopping. These images could remind individuals of their experience as consumers and therefore activate their identity. Depending on which identity is activated, individuals may express different attitudes towards free trade. For example, those who see themselves primarily as producers may be more concerned about protecting local employment and therefore more sceptical about free trade. On the other hand, those who see themselves primarily as consumers may be more interested in access to cheaper goods and therefore more supportive of free trade.

The results found are that individual support for free trade is 13 points higher for individuals to whom the consumer identity was activated compared with the control group, and if we compare the group of producers and consumers, individual support for free trade is 13% higher among consumers. These results are interesting and highlight the importance of identities and perceptions in the formation of political and economic preferences. The study suggests that consumer identity, when activated, can make individuals more supportive of free trade. This could be due to the perception that free trade generally leads to lower prices and a greater variety of goods available to consumers. On the other hand, producer identity, when activated, may make individuals more concerned about foreign competition and the potential impact of free trade on local jobs.

Our perception of ourselves - our personal identity - can strongly influence our opinions, attitudes and behaviour. In the case of the economy and international trade, if we identify ourselves primarily as consumers, we may be more inclined to support free trade policies, because of the potential benefits in terms of product cost and diversity of goods available. Conversely, suppose we identify ourselves primarily as producers or workers. In that case, we might be more inclined to be sceptical or hostile to free trade, because of fears of international competition and potential job losses. This is an excellent example of how our personal identities and self-perceptions can influence our political and economic opinions and attitudes.

An individual's social identity, whether as a producer or consumer, is strongly influenced by their social interactions and everyday experiences. Constructivists argue that our identities, interests and preferences are not fixed or innate, but rather the product of continuous and dynamic social processes. For example, a person working in an industry heavily affected by international competition might develop an identity as a 'producer' and, consequently, have preferences for protectionist policies. Conversely, someone who benefits from a wide variety of imported products at competitive prices might develop an identity as a 'consumer' and therefore support free trade. So it is through our social interactions and life experiences that we formulate our identities and determine our public policy preferences.

According to this theory, the interests of an individual or group are not simply given or determined by external factors, but rather are shaped and modified by social interactions. This means that our beliefs, values and preferences are not immutable. They can evolve and change due to our interactions with others and the world around us. As a result, our attitudes and behaviours are also subject to change. This is in marked contrast to other social and political science theories, which often assume that interests are fixed and do not change or are determined primarily by material or economic factors. On the other hand, constructivism greatly emphasises the influence of ideas, values, culture and social norms on the formation of interests and behaviour.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Ideal Approach in Political Science[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The ideas approach, often adopted by constructivists, plays an essential role in our understanding of politics and society. However, like all theories, it has its strengths and weaknesses.

Emphasis on the ideal and normative dimension of human action[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

One of the main advantages of the constructivist or idea-based approach is its ability to take account of the ideational and normative dimensions of human action. This involves analysing how ideas, beliefs and values influence behaviour and decision-making. This contrasts with certain other approaches, such as realism or liberalism in international relations, which tend to focus more on material interests and power structures as determining factors. These approaches may tend to see ideas as relatively constant or secondary to material interests. However, constructivism argues that ideas and norms can change over time and that these changes can have important effects on politics and society. This can help explain phenomena such as policy changes, social movements, or shifts in international norms. However, it is important to note that while ideas are important, they often interact with other factors, such as material interests and power structures. So a balanced approach should take account of both ideas and these other factors.

When we look at political and cultural history and trends over a long period of time, it is clear that ideas and ideologies can and have undergone significant change. For example, consider the evolution of social norms and ideologies on issues such as human rights, gender equality, democracy and the environment. These ideas have evolved considerably over the last few centuries, and these changes have had a major impact on policies and practices worldwide. On the other hand, deeply held ideas and beliefs can be very resistant to change in the short to medium term. This can make ideas seem constant over shorter periods of time. This is why it is important to take a long-term perspective when studying the evolution of ideas and ideologies. At the same time, it is also crucial to understand that ideas do not change in a vacuum - many factors, including material conditions, power relations, and historical events influence them. So a comprehensive approach to the analysis of ideas should also take these dynamics into account.

Organisations, including trade unions, have ingrained ideologies and beliefs shaping their worldview and approach to political and economic issues. These beliefs are often deeply embedded in the culture and identity of the organisation, and they do not change easily or quickly. For example, a union that has long supported Keynesian policies - which advocate state intervention in the economy to stimulate demand and combat unemployment - would not easily or quickly adopt a neo-liberal ideology, which advocates minimal state intervention and free competition. This is not to say that change is impossible, but it would probably be slow and difficult and would require a combination of factors, including changes in the economic and political environment, changing beliefs and attitudes among union members, and leaders capable of promoting and implementing change.

The social artificiality of interest, the economy and the nation[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The constructivist approach in the social sciences emphasises the idea that many aspects of our social, economic and political reality are the product of social constructions rather than natural or inevitable phenomena.

For example, the idea of 'interest', whether personal, economic or national, is not inherent or fixed. Social norms, prevailing ideas, education, experience and other factors shape it. Interests can therefore change over time as these factors evolve. Similarly, the notion of 'the economy' and how it works are also influenced by various social constructs, including ideas about value, work, property, justice, etc. For example, valuing paid work over unpaid work (such as caring for children or the elderly) is a product of social norms and ideas rather than an inevitable reality. Finally, the notion of 'nation' itself is a social construct which has evolved over time and continues to be debated and redefined. The nation is not a fixed or natural entity but an idea that is constantly constructed and reconstructed through discourses, symbols, histories and politics. By highlighting these social constructions, constructivism offers a framework for understanding how ideas and beliefs shape our world and how they can be challenged and changed.