Action in Political Theory

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

In the sphere of political theory, the importance of understanding action - the ways in which individuals or groups engage with the political context - has become increasingly crucial. The term 'action' is constantly evolving, becoming increasingly complex as our understanding of human behaviour deepens and the global political context changes. This leads us to continually rethink and reassess theories of action, with the ultimate aim of providing a more nuanced and sophisticated framework for interpreting political actors.

As the world has become increasingly interconnected, action in the political context has also become more complex. Today, political actors are no longer simply individuals or groups of individuals; they can be organisations, institutions and even nations. They are also influenced by an ever-wider range of factors, from economic dynamics and social pressures to environmental and technological challenges. In response to the increasing complexity of action, theories of action have had to evolve. We have seen traditional approaches, such as rational choice theory, complemented and sometimes challenged by new perspectives, such as structuralist, constructivist and relational approaches. Each of these theories offers a unique lens through which to understand action, and all have contributed to broadening our understanding of the behaviour of political actors. The evolution of theories of action has opened the way to new ways of interpreting political actors. Instead of seeing political actors simply as autonomous entities seeking to maximise their own self-interest, we can now understand them as complex entities, rooted in a web of social relations, shaped by social and political structures and acting according to socially constructed norms and ideas.

Thus, by continually revisiting and reassessing theories of action, we can hope to better understand the complexity of action in the contemporary political context. Moreover, this approach allows us to interpret political actors through a more refined lens, giving us the tools we need to navigate today's complex political landscape.

Definition and issues of action in political theory[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The essence of action is intrinsically linked to the environment in which it takes place. It is this environment that provides the context, the framework and the resources necessary for action. The environment, whether social, political, economic, technological or natural, offers both opportunities and constraints that shape the possibilities for action. For example, a country's political environment can influence the actions of individuals and groups by determining the laws, regulations and norms that govern behaviour. Similarly, the social environment, including culture, social norms, relationships and networks, can also influence action by shaping expectations, obligations and opportunities.

When the environment changes, whether through political events, social changes, technological advances, environmental crises or economic transformations, the conditions for action also change. A change in the environment can make certain actions more difficult, by introducing new constraints, or it can open up new possibilities for action, by offering new opportunities. This means that to understand action, it is crucial to understand the environment in which it takes place. It is also important to recognise that action itself can influence the environment, creating a complex cycle of interaction between action and environment. The actions of individuals and groups can transform their environment, creating new conditions for future action.

The concept of action is fundamental to political philosophy and was studied in depth by classical Greek philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato. For these thinkers, the question of action was intrinsically linked to the understanding of man as a political animal and to the nature of good and evil, ethics and justice.

Plato defined action in ethical and political terms in his vision of the ideal republic. In "The Republic", he argues that right action is that which contributes to the harmony of the city, where each individual plays his appropriate role according to his natural abilities. For Plato, action is intrinsically linked to virtue and the achievement of the common good. Aristotle, on the other hand, broadened the understanding of action in his notion of 'praxis'. For Aristotle, praxis (action) is a conscious and voluntary human activity, directed by reason, which aims at the good and the realisation of eudaimonia (a good and fulfilled life). For Aristotle, action is distinct from "poiesis" (production), which is the activity of creating something for an end outside itself. Praxis, on the other hand, is an end in itself. In his work Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle explored in depth the way in which ethical action, guided by virtue, contributes to the realisation of the individual and common good.

The work of these philosophers laid the foundations for many subsequent political and ethical theories on action. Their thinking continues to influence our understanding of action and the role of the individual in society, and is still relevant to understanding action in the contemporary political context.

The notion of action is central to political science. It is seen as the expression of man's engagement with his environment, an environment that can be both social and natural.

- Action as natural movement: From this perspective, action can be seen as an extension of natural movement, where human beings are constantly interacting with their environment. Action is not just a response to external stimuli, but also a self-affirmation, a way for human beings to assert themselves in the world. Action is thus an expression of human will, a manifestation of our ability to influence our environment rather than simply being influenced by it.

- Action as a necessity: Man, as a social and political being, needs to act. Action is often a response to a situation perceived as unsatisfactory, or to a desire to change existing conditions. In this sense, action is often motivated by some form of necessity - be it the need for survival, justice, equality, freedom or personal fulfilment.

- Action as an attentive endeavour: Political action is not an impulsive or thoughtless activity. It requires attention, preparation and reflection. Attention is needed to understand the environment, to assess the potential consequences of different actions and to make informed choices. In the political context, careful action is often necessary to navigate complex and uncertain environments, to manage power relationships and to promote the common good.

Thus, the notion of action in political science refers to an image of man as a committed, attentive and needy being who is constantly on the move and interacting with his environment. This understanding of action underlines the importance of human agency in shaping our societies and our world.

The idea of action, rooted in movement, is a central concept for philosophy and political theory. It is based on the notion that action is not a sterile activity, but a dynamic process that involves change or movement towards some goal or end. In philosophy, action is often discussed in terms of finality or teleology - the idea that there is a goal or end towards which action is directed. This view is largely influenced by classical philosophers such as Aristotle, who argued that all action has some end in view, and that the ultimate end of human action is happiness or eudaimonia. In political theory, the idea of action as movement towards a certain goal is also crucial. In particular, in the context of democracy, action is often seen as directed towards the public good or the common good. Citizens act - whether through voting, participation in civic life, or commitment to social and political causes - with the aim of influencing politics and society in ways that promote the well-being of all. Moreover, in a democracy, the idea of action is linked to the notion of civic responsibility. Acting for the common good is seen as an obligation for citizens. This can take a variety of forms, ranging from compliance with the law to participation in political decision-making and a commitment to equality, justice and sustainability. That said, the idea of action in philosophy and political theory is complex and multifaceted. It involves both an individual dimension (the individual acting according to his or her own motivations and objectives) and a collective dimension (individuals acting together for the good of society).

The notion of action in classical and Christian philosophy is intimately linked to reflection, intelligence and the concept of God. In these philosophical and theological traditions, God is often seen as the primary agent, the one who sets everything in motion. In classical philosophy, Aristotle, for example, spoke of God as the "immobile prime mover", a first cause which, although immobile itself, is the origin of all movement and action in the universe. For Aristotle, movement is a fundamental characteristic of reality, and all action is directed towards a certain end or good, reflecting the natural order established by the First Mover. In Christian philosophy, the notion of action is also closely linked to the understanding of God. God is often described as being in constant action, through his creation, his providence, and his plan of salvation for mankind. In this tradition, man is called to participate in God's action by conforming to his will and acting for good. Human action is thus seen as a response to divine action and as a participation in God's work in the world. This conception of action as movement and participation in divine action has profound implications for the way we understand human responsibility, ethics and the role of man in the world. It underlines the importance of conscious, thoughtful, good-oriented action, and emphasises the spiritual and moral dimension of action. Furthermore, it invites us to see action not only as a human activity, but also as a participation in a greater and deeper reality.

The philosopher Immanuel Kant explored in depth the relationship between action and morality. For Kant, morality is not measured by the effect of an action, but rather by the intention that motivates it. In his theory of duty or 'deontology', Kant postulated that moral action is that which is performed out of duty, out of respect for the universal moral law. This universal moral law is formulated by Kant in what he called the categorical imperative, which is an unconditional moral law that applies to all rational beings. The categorical imperative is formulated in several ways, but one of the most famous is: "Act only according to the maxim that makes you able to will at the same time that it becomes a universal law." This means that for an action to be moral, it must be capable of being universalised - that is, we should be prepared to accept that everyone acts in the same way in similar circumstances. If an action does not meet this criterion, it is considered immoral. As far as the common good is concerned, Kant recognised that some actions might run counter to the common good or collective interest. However, for him, morality is not determined by the consequences of the action (as is the case in consequentialist theory of ethics), but rather by whether the action corresponds to the categorical imperative. Consequently, even though an action may seem beneficial to the common good, it would be immoral if it violated the categorical imperative. From this perspective, action in the political sphere, including public policy, must also adhere to the principles of Kantian ethics. For example, a public policy that violates the fundamental rights of individuals would be considered immoral, even if it appears to serve the collective interest, because it would violate Kant's categorical imperative, which demands respect for the dignity and autonomy of each individual.

Political science, as a distinct academic discipline, developed out of moral and political science in the nineteenth century. It is primarily concerned with the study of power, political structures and political behaviour, but its roots in moral and political science mean that it is also concerned with ethical and moral issues. Political action, in particular, is an area where moral issues are particularly relevant. Political actions can have significant consequences for individuals and society as a whole, raising questions about what is right or wrong, fair or unfair, ethical or unethical. Moreover, political action is often motivated by moral or ethical convictions and aims at objectives that are considered morally important, such as justice, equality, freedom, or the common good. That said, it is important to note that, although political science is concerned with moral issues, it is first and foremost an empirical discipline. That is, it aims to study political phenomena as they are, rather than prescribing how they should be. In this sense, political science can help us to understand the nature of political action and to analyse its causes and consequences, but it often leaves it to other disciplines, such as political philosophy or ethics, to determine what is morally right or wrong in political action.

A number of problems emerge which highlight the complexity of action in political science:

- Action and decision: Action is often linked to decision. In many situations, before taking action, a person or political entity must first make a decision. It is in this decision-making process that actors evaluate different options, consider the potential consequences, and finally choose a course of action. Consequently, understanding action in politics often requires an understanding of decision-making processes.

- Action as support for the world: In classical political theory, action (and the decision that precedes it) is often seen as a means of shaping, structuring and supporting the world. By making decisions and taking action, political actors contribute to the creation and preservation of social and political order.

- Action and competence: The effectiveness of an action often depends on the competence of the actor. In the political context, making the "right" decision or taking the "right" action requires a precise understanding of the problems to be solved, the forces at play, and the potential consequences of different options. Assessing action and decisions from this perspective raises questions about the competence and responsibility of political actors.

- Action for social preservation: Finally, action can be seen as a means of preserving society. This can be done in different ways, for example by maintaining social order, promoting justice and equality, or defending the interests of the community. From this perspective, action is not only a means of achieving individual goals, but also a tool for collective well-being and social stability.

Action in political science is a complex concept involving decision, competence, world support and social preservation. These dimensions underline the importance of action for understanding politics and societies.

Decision-making is a fundamental element of action. It serves as a prelude to action, because it is through the decision-making process that the actor determines what action to take. To act without a decision would be to act without reflection or knowledge, which is generally inadequate in complex contexts such as politics.

The dimensions of decision can include :

- Evaluating options: Before making a decision, the stakeholder must identify and evaluate the different possible options for action. This may involve considering the advantages and disadvantages of each option, forecasting the potential consequences, and assessing the feasibility of each option.

- Consideration of values and objectives: The decision is also influenced by the actor's values, objectives and preferences. For example, a political actor may decide to act in a certain way because he believes it is most consistent with his values or political objectives.

- Judgement under uncertainty: Decision-making often involves making judgements under uncertainty. In politics, it is rare for all the necessary information to be available, and the actor often has to make decisions on the basis of incomplete or uncertain information.

- The social and institutional context: Decision-making is also influenced by the social and institutional context in which it takes place. For example, social norms, institutional constraints and the expectations of other stakeholders can all influence the way decisions are made.

Decision-making is a crucial aspect of political action. It enables the actor to define and plan his action, and involves a complex process of evaluating options, taking into account values and objectives, making judgements under uncertainty, and navigating the social and institutional context.

The action/decision pair is fundamental to political science, as it is to many other fields. This pair conceptualises the idea that decision precedes and informs action: we make a decision, then act on it. Through this process, we try to limit randomness and introduce a form of rationality into our actions.

- Reducing randomness: When we make decisions, we often try to take into account all the available information, evaluate the different options and choose the one that seems to be the best. This reduces randomness and increases the chances that our actions will produce the desired results. It should be noted, however, that all decisions involve a degree of uncertainty and risk.

- Rationality: In theory, decision-making is a rational process. We weigh up the pros and cons of each option, foresee the potential consequences, and choose the option that seems best to us. In practice, however, decision-making is often influenced by non-rational factors, such as emotions, cognitive biases and social pressures.

- Present-past relationship: Action and decision are embedded in a temporal relationship. Our present decisions and actions are informed by our past - by our experiences, our knowledge, and the lessons we have learned. At the same time, our decisions and actions in the present determine our future. For example, a political decision taken today can have long-term consequences for a society.

The action/decision pair is a fundamental characteristic of human activity. It is particularly relevant in the political context, where decisions and actions can have significant consequences for individuals and society as a whole.

The way in which we theorise and conceptualise action is closely linked to the conditions and context in which the action takes place. And since these conditions are constantly changing, our understanding of action must also evolve.

- Changing conditions: Political, economic, social, technological, environmental and other conditions can all influence the way in which action is taken. For example, the emergence of new technologies can create new opportunities for action, but also new challenges and dilemmas. Similarly, changes in the political or social climate can affect the motivations, opportunities and constraints faced by actors.

- Evolving theory of action: As conditions change, it becomes necessary to adapt and refine our understanding of action. This may involve developing new theories or modifying existing ones to take account of new realities. For example, the rise of social media has led to new theories of collective action and social movement.

- Interdependence of theory and practice: The theory and practice of action are closely linked. Theories of action help to inform and guide action, while observation of actual action can help to test, refine and develop theories. It is a process of continuous interaction, where theory and practice inform and shape each other.

La théorie de l'action est un domaine dynamique et évolutif, qui doit constamment s'adapter pour rester pertinent face aux conditions changeantes dans lesquelles l'action se déroule.

There are four main roles or objectives that decision making can fulfil in a given context, in this case within the framework of political theory. These functions are key aspects of what decision-making does in that context, i.e. the roles it plays or the objectives it serves. Here is a more detailed explanation:

- Enable the actor to act: By taking a decision, an actor (individual, group or institution) defines a path to follow, an action to undertake. The decision is therefore the prerequisite for any action.

- Enabling citizens to support the world: The ability to make decisions gives citizens a degree of control over their environment. This can help give them a sense of control and active involvement in the world.

- Fragmenting actions into respective skills: The decision-making process can help to divide complex tasks into simpler, more manageable skills or roles. This can facilitate collaboration, delegation and efficiency in collective actions.

- Ensuring social preservation: Decisions taken by political actors can contribute to the preservation of society by maintaining social order, promoting justice and equality, or defending the interests of the community.

Thus, the decision is not just an individual process of choosing between different options. It is also a social process that has implications for the organisation and preservation of society as a whole.

Action is a central theme in political philosophy, and many philosophers have developed different theories on the subject. Aristotle introduced a theory of action centred on the concept of 'telos' or ultimate goal. In his work Nicomachean Ethics, he argued that all human action is aimed at a certain good and that the ultimate goal of all action is eudaimonia, often translated as happiness or well-being. In the 17th century, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes proposed a different vision of action. In his work Leviathan, he argues that human actions are motivated by desires and fears. Man's natural state is a "state of war of all against all". Political action is therefore necessary to create a "Leviathan", a sovereign state that maintains peace and order. Immanuel Kant, an eighteenth-century philosopher, developed a theory of action based on morality and duty. For Kant, an action is moral if it is performed out of respect for the moral law, regardless of its consequences. In the twentieth century, John Rawls proposed in his theory of justice that a just action is one that respects the principles of justice that rational individuals in an "original position" of equality would have chosen. Finally, the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas put forward a theory of communicative action. According to him, social action is primarily directed towards mutual understanding rather than individual success. Each of these theories offers a unique perspective on what motivates human action and how we should act, reflecting the complexity and diversity of factors that can influence action.

Exploring the different theories of action[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Action as a condition of modern man: Hannah Arendt's perspective[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Hannah Arendt, a twentieth-century German political philosopher, developed a theory of action that highlights its importance for human nature and political life. According to Arendt, action is fundamental to human existence and to politics. In her major work, The Human Condition, Arendt draws a distinction between work, work and action. For her, action is the domain of human life that is directly linked to the public sphere, to politics. Action, for Arendt, is what allows us to distinguish ourselves as unique individuals and to participate in the life of the community. Arendt argues that action is what makes man a political being. By acting, we reveal ourselves to others, we express ourselves and we participate in the construction of the common world. For Arendt, the ability to act is what enables people to remain human, in other words to exist as unique individuals within a community. In this sense, Arendt's theory of action is a celebration of the human capacity to act freely and influence the world. It is also an affirmation of the importance of the public sphere and political life as places where this capacity for action can be fully expressed.

Hannah Arendt's thinking on action is deeply rooted in her analysis of the human condition. For her, action is the means by which human beings engage with the world and affirm their existence. By acting, we create and shape our shared world, and assert ourselves as autonomous and free beings. For Arendt, acting is fundamentally linked to our mortal condition. It is because we are aware of our mortality that we seek to act, to leave our mark on the world. Action is therefore, in a sense, an affirmation of life in the face of death, an affirmation of our power to create and change the world despite the finiteness of our existence. For Arendt, belonging to the world is also a fundamental condition for action. We do not act in a vacuum, but always in the context of a shared world, a public sphere. It is in this public sphere that our action takes on its meaning, because it is there that it is seen and heard by others. So, according to Arendt, politics, as a space for action, is fundamentally linked to the human condition. It is through political action that we affirm our existence, our freedom and our belonging to the world. And it is through political action that we help to create and shape that world.

According to Hannah Arendt, the ability to act is intrinsic to human nature and a fundamental expression of our humanity. This capacity to act is all the more vital in difficult situations where giving up may seem tempting. For Arendt, action is not just a personal choice, but a collective and intergenerational responsibility. Each generation inherits a world shaped by the actions of those that preceded it, and in turn has a duty to engage with it and transform it through its own actions. This responsibility transcends the individual and is part of a collective and historical dimension. This vision of action as a duty is deeply rooted in Arendt's commitment to democracy and citizen participation. She maintains that politics, as a field of action, is essential to the life of a democratic community. Every citizen has not only the right but also the duty to participate actively in the political life of his or her community. For Arendt, to be human and to be political means to be an active agent, capable of acting and having the duty to act, whatever the circumstances.

One of the fundamental principles of democracy is the ability of citizens to act, also known as agency. In a democracy, individuals have the power to express their ideas, to participate in political decision-making and to influence the direction of their society. Voting, for example, is a form of action that enables citizens to participate directly in the governance of their country. By contrast, in a totalitarian regime, people's ability to act is generally severely limited. Citizens generally do not have the right to express themselves freely, to organise or to participate in political decision-making. Totalitarian regimes seek to control all aspects of social and political life, leaving little room for individual action. Arendt herself has written eloquently about totalitarian regimes, having fled Nazi Germany and studied totalitarian systems in works such as "The Origins of Totalitarianism". In her view, totalitarianism seeks to destroy the public sphere of action and to eliminate human plurality, the prerequisite for all political action. Speech, according to Arendt, is an essential form of action in a democracy. Through speech, citizens can express their ideas, debate important issues and participate in political life. Freedom of speech is thus inseparable from the ability to act in a democracy.

Hannah Arendt defended the idea that the essence of the human condition lies in our capacity to act - to initiate new actions spontaneously and unpredictably. In her view, this capacity for action is intimately linked to our mortality and our birth. Each birth, according to Arendt, represents the arrival of a new and unique actor in the world - an actor capable of taking new actions and giving a new direction to the course of things. This spontaneity, this ability to initiate new actions, is what enables change and progress in the world. Arendt also argues that speech is an essential form of action. Through speech, we reveal ourselves to others, we engage the world and we participate in the construction of the common world. Speech is therefore a means of integration and action in the world. According to Arendt, it is this capacity to act and to speak that underpins our humanity. Without it, we would be incapable of participating in the life of the community or leaving our mark on the world. For Arendt, the ability to act is therefore at the heart of the human condition and political life.

According to Hannah Arendt, action is the means by which we manifest our individuality and humanity in the world. She sees action as the fundamental expression of our freedom - the freedom to start something new, to initiate change, to make a difference. By taking action, we are not just doing something in the outside world; we are also shaping and defining ourselves as individuals. Every action we take is a manifestation of our personality, our values and our choices. So, by acting, we 'become' ourselves in a very real sense. This is why Arendt places such importance on the capacity to act as an essential characteristic of the human condition. Without the capacity to act, we would be deprived of the possibility of manifesting ourselves as unique and free individuals. Action is therefore not only a means of interacting with the world, but also an essential means of realising and constructing ourselves as human beings.

For Hannah Arendt, three fundamental conditions define human existence: natality, mortality and plurality.

- The birth rate is the ability to start something new, to be spontaneous and free. It's what enables us to act and change the world.

- Mortality is the awareness that our time is limited, which gives value to our actions and makes our existence meaningful.

- Finally, plurality is the fact that we are all different and yet share the same world. It is this condition of plurality that makes us political beings, capable of dialogue, debate and taking decisions together.

Arendt emphasises that these conditions of existence place us all on an equal footing. Whatever our gender, race, social class or nationality, we all face the same basic conditions. This is why we all have a duty to act, to participate in the life of the community and to care for the world we share.

The notion of plurality, as developed by Hannah Arendt, captures a fundamental double truth about human existence: on the one hand, we are all equal as human beings, sharing the same basic conditions of existence; on the other hand, we are all unique, possessing a distinct individuality and identity that cannot be reduced or erased. For Arendt, this duality lies at the heart of political life. Politics is where we negotiate both our equality (we are all citizens, with the same fundamental rights) and our distinction (we all have different ideas, values and goals). It is the place where we demonstrate both our individuality (through our actions, our words, our choices) and our belonging to a wider community. Plurality is therefore an essential principle of democracy: it requires us to recognise and respect both our common humanity and our unique individuality. This is what makes peaceful coexistence, dialogue and cooperation between different people possible. It is also what makes politics both difficult and necessary.

The "common world" is a key concept in Hannah Arendt's political philosophy. For her, human beings live not only in their physical environment or in their particular society, but also in a world shared by all human beings, a world made up of language, traditions, institutions, works of art and all the other products of human activity. For Arendt, this shared world is both the context and the product of human action. It is the framework within which we act, and it is shaped and transformed by our actions. It is in this shared world that we reveal ourselves to ourselves and to others, and leave our distinctive mark. Arendt also emphasises that caring for and preserving this common world is an essential political responsibility. Indeed, the common world is what gives meaning to our individual lives, and it is what we leave as a legacy to future generations. Consequently, we all have an interest in ensuring that this world is fair, sustainable and liveable for all. In this sense, Arendt's concept of the 'common world' has important implications for a range of contemporary political issues, from social justice to environmental protection.

For Hannah Arendt, action is the highest manifestation of human freedom. It is through action that we show initiative, influence the world and reveal ourselves and each other. Action is also the means by which we assume our responsibility towards the common world and towards others. By acting, we make decisions that have consequences for ourselves and for others, and we take responsibility for these consequences. Arendt particularly emphasises the crucial role of speech in action. For her, speech is what gives meaning to action, what makes it intelligible and recognisable. It is through speech that we express our intentions, justify our actions and commit ourselves to others. Speech is therefore not only a complement to action, but also a form of action in itself. This is why, for Arendt, politics is essentially a matter of speech and action: it is the domain where we deliberate together about what we should do, where we make collective decisions and where we act together to implement those decisions. It is in this process of speaking and acting that democracy is realised as a form of living together based on freedom and responsibility.

For Hannah Arendt, action and speech are intimately linked. Speech, particularly in the form of dialogue, is a fundamental vehicle for political action. Through speech, we can not only articulate our understanding of the world and our intentions, but also coordinate our actions with those of others, negotiate compromises, resolve conflicts and build alliances. Dialogue is therefore an essential mode of political action. It is the means by which we can share our perspectives, listen to those of others, learn from each other and come to a common understanding. It is through dialogue that we can reach consensus on what is right and what is necessary, and develop collective action plans. At the same time, dialogue is also a form of action in itself. By engaging in dialogue, we are actively participating in political life, contributing to the formation of public opinion, and helping to shape the common world. It is in this sense that Arendt speaks of politics as a space for speech and action, where freedom and responsibility come together. Arendt's concept of political action thus highlights the crucial role of communication, deliberation and dialogue in democracy. It reminds us that politics is not simply a question of power and interests, but also and above all a question of speaking, listening and mutual understanding.

Hannah Arendt's analysis of the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century highlights several fundamental characteristics of these systems of power:

- The suppression of plurality: For Arendt, a central element of totalitarianism is its tendency to eradicate plurality, which lies at the heart of the human condition. Totalitarian regimes seek to homogenise society by eliminating or repressing differences. In so doing, they deny the singularity of each individual and seek to transform him or her into a mere part of an undifferentiated mass.

- The single man: Totalitarianism seeks to mould all individuals according to a single ideal or model. From this perspective, anything that does not correspond to this ideal is seen as a threat and must be eliminated.

- Political universalisation: Totalitarian regimes often seek to universalise their ideology, claiming that it represents the only truth valid for all human beings, everywhere and at all times. This claim to universality is used to justify the regime's total domination of society and the elimination of all opposition.

- The suppression of speech: For Arendt, totalitarianism seeks to eliminate the public space where speech and action are possible. This is done by controlling information, censoring free speech and repressing all forms of dissent. By suppressing the possibility of speech and dialogue, totalitarian regimes seek to prevent individuals from thinking for themselves and acting on their own judgements. Thus, for Arendt, totalitarianism is a form of "terror" that seeks to destroy people's capacity for action and judgement.

For Hannah Arendt, the aim of a totalitarian regime is to destroy people's capacity for political action, and this is largely achieved by suppressing speech. It is through speech, and in particular through dialogue, that individuals express their thoughts, make their voices heard, share their points of view, discuss common issues, take collective decisions and act in the world. In a totalitarian regime, speech is censored, controlled and manipulated to prevent any form of dissent or criticism, and to impose a single version of reality, that of the regime. Individuals are reduced to forced silence, deprived of their ability to think and judge for themselves, and transformed into anonymous members of an undifferentiated mass. This has the effect of eliminating the public sphere as a place for debate, deliberation and collective action. Politics, in the sense of a democratic process involving a plurality of actors engaged in mutual interaction, is replaced by a system of totalitarian domination that denies freedom and human dignity. According to Arendt, the ability to think, to speak and to act are essential to the human condition and to democratic life. The suppression of speech in totalitarian regimes is therefore a fundamental attack on humanity itself. This is why she places so much emphasis on the importance of resistance, political commitment and the defence of freedom of speech and thought.

Speech is fundamental to action and democracy. Speech provides a means by which individuals can express their thoughts and ideas, discuss various problems, and work together to find solutions. Speech, as a means of communication, enables people to share information, engage in dialogue and participate in deliberation. In the context of democracy, speech plays a central role in enabling active political participation. Through dialogue and debate, citizens can participate in decision-making, which is a fundamental element of any democratic system. Moreover, freedom of speech is often considered a fundamental right in a democracy, as it allows citizens to express their opinions, criticise the government and defend their rights. Consequently, the suppression of speech, as Hannah Arendt points out in her analysis of totalitarian regimes, is an attack on democracy and on the very essence of humanity. By silencing citizens, totalitarian regimes seek to control not only action but also thought, which is an attack on human freedom and dignity.

In Arendt's vision, the 'common world' is a sphere where humanity shares the experience of life through speech and action. These two elements are crucial because they enable the exchange of ideas, cooperation and the development of a collective identity. Speech, in this context, is the means by which individuals express their thoughts and intentions, deliberate on problems and opportunities, and ultimately make decisions. Through action, they put these decisions into practice, thereby influencing the world around them. Arendt also values spontaneity as an essential component of the shared world. For her, human spontaneity is a source of creativity and novelty, a means by which individuals can exercise their freedom, take initiative, innovate, and face unforeseen challenges. Spontaneity enables people to go beyond what is pre-established or predetermined, and thus to transform the world. Finally, the 'common world' is also a place of diversity and equality. For Arendt, plurality - the fact that we are all different and unique - is a richness that enriches our shared experience of the world. However, despite these differences, we all share the same human condition, which establishes a fundamental form of equality between us. Recognition of this diversity and equality is fundamental to democracy and social justice.

The concept of "Action - Decision - Word" is fundamental to democracy, and it is through these tools that man engages with the world as a political animal.

- Action: As political beings, people have the capacity to take action to influence their environment and the society in which they live. These actions can take many forms, from voting in elections to taking part in demonstrations, volunteering or contributing to public debate.

- Decision: Decision-making is the process by which an individual or group chooses one course of action from several alternatives. In a democracy, the decision-making process is generally collective and inclusive, which means that all voices have the right to be heard and decisions are taken on the basis of consensus or a majority vote.

- Speech: Speech is a crucial tool for expressing ideas, opinions and feelings. In a democracy, freedom of expression is a fundamental right that allows every individual to share their views and contribute to public debate. It is through speech that people can defend their rights, criticise political decisions and put forward new ideas for the future of their community or country.

These three elements are intimately linked and mutually reinforcing. Action flows from decisions, which are informed by words. And words can inspire new actions and informed decisions. Together, they form a dynamic cycle that lies at the heart of democracy and political engagement.

In political theory, the interaction between speech and action is fundamental to understanding how individuals and communities function. Speech is the primary tool for communicating, expressing ideas and sharing perspectives. It is used to express our thoughts, feelings and intentions, to negotiate and to debate. Speech can enlighten, inspire, persuade and mobilise. It can ask questions, challenge existing assumptions and propose new visions of the world. Action, on the other hand, is the concrete expression of these discourses. It is through action that ideas and intentions take shape. Action is the means by which we influence the world around us, and how we react to circumstances and events. These two components are interdependent and dynamic. Speech informs action, and action in turn can give rise to more speech and discourse. In this way, speech and action exist in a constant cycle of interaction and reaction. Moreover, speech and action are both essential means by which we escape isolation. Together, they enable us to engage with others, to understand and be understood, to collaborate, to negotiate, to resolve conflicts and to participate in social and political life. They are therefore essential to our humanity and to our participation in the political community.

Action is dynamic and contains an element of uncertainty. Every time we act, we enter into a kind of unknown. We cannot accurately predict all the consequences of our actions, because they are influenced by many factors, some of which are beyond our control or understanding. This is particularly true in politics, where the actions of an individual or group can have unforeseen and sometimes far-reaching repercussions. Sometimes the results of an action can be very different from what was originally intended. That's why it's essential to approach action with a degree of humility, an understanding of its limits, and a willingness to learn and adapt along the way. At the same time, every action brings us new experience and new knowledge. Even when the results are not what we hoped for, we can learn from our mistakes and use these lessons to guide our future actions. In short, action is both a means of exercising our will and of learning, a process that generates both knowledge and non-knowledge. By non-knowledge, we mean an awareness of our limits, of the uncertainties and complexities that characterise human life and political activity.

Man seeks to build a predictable and orderly destiny. It is a natural aspiration that drives us to plan, to set objectives, to seek to control our environment. In politics, this translates into the drafting of laws, policies, action plans, etc., with the aim of creating a stable and predictable framework in which we can live and prosper. However, reality is often unpredictable and does not always bend to our plans. Unexpected events can occur that disrupt our plans and force us to adapt and change course. This is where the ability to react, improvise and demonstrate resilience becomes crucial. Indeed, flexibility and the ability to manage uncertainty are just as important as the ability to plan and forecast. It is in this tension between predictability and unpredictability that human action is situated. We try to create a predictable future, while being aware that we will constantly have to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. This reality, while sometimes frustrating, is also what makes human life and political activity so dynamic and interesting.

Action can be a source of anxiety and uncertainty. Making decisions and taking action inevitably means facing the unknown and the unpredictable. Every choice we make has consequences, sometimes predictable, often not. This is where a large part of the anxiety associated with action lies. What's more, choosing one path often means giving up others. There is an inherent loss in every choice we make, a philosophical notion often referred to as 'opportunity cost'. This can lead us to question what we may have missed out on by taking one decision rather than another. In politics, these issues are multiplying. Leaders are often faced with difficult decisions and have to make choices that affect not only their own lives, but also the lives of many others. This responsibility can certainly intensify the anxiety associated with taking action. But it's important to remember that action, despite its potential for anxiety, is also a source of power and potential. It is through action that we can influence the world around us, face challenges and create positive change. Despite the uncertainty, action is an essential part of human existence and political activity.

Action is a fundamental component of our being and our interpretation of the universe. Our ability to grasp, interact with and influence the world would be considerably diminished without action. Firstly, action is often an extension of our thoughts and beliefs. It is by acting that we test our assumptions and perceptions of the world. For example, we can conceptualise the impact of a given policy, but it is only by putting it into practice that we can really grasp the consequences. Secondly, action allows us to interact with the world in tangible ways. Through our actions, we actively participate in social, political and economic life. So, by taking action, we are not just spectators of the world, but actors who influence its course. Last but not least, it is through action that we can change the world. Our actions, whether large or small, have the potential to shape the future. This is particularly evident in politics, where actions - whether voting, demonstrating or legislating - can bring about major transformations. Action is intrinsically linked to our existence, our understanding of the world and our ability to change it. Without action, our commitment and influence on the world would be severely limited.

Action from the perspective of the rational world[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The view of the world as increasingly rational was a dominant one, particularly in the early and mid 20th century. This was largely due to the growing confidence in science, technology and human reason, which promised to solve social, political and economic problems. Rationality was seen as the path to progress, and many believed that through a more rational approach we could create a fairer, more efficient and more productive society. This perspective was rooted in a belief in 'positive progress', the idea that humanity was inevitably moving towards a better future through advances in knowledge and technology. It was believed that rational approaches to decision-making, whether in economics, politics or science, would lead to better outcomes. This view of the world greatly influenced the political theory of the time. It contributed to the rise of liberalism, socialism and other ideologies that saw rational progress as a means of achieving social and political ideals. Rationality was seen as an essential tool for understanding the world, solving problems and guiding action.

The notion of rational action has been widely explored and developed by a number of theorists and philosophers, particularly within the classical sociological tradition. Max Weber, for example, was one of the first to formalise the concept. For Weber, rational action is action guided by conscientious and systematic calculations of the most effective means of achieving a specific objective. It is action that is determined by logical and reflective considerations, rather than by emotions, traditions or social imperatives. This concept is based on the idea that man, as a rational being, will naturally seek to optimise his actions to achieve his objectives in the most effective way possible. This perspective is part of a wider vision of the rationalisation of society, in which individuals and institutions are increasingly seeking to organise their actions in a rational and systematic way. This view of human action as essentially rational has been highly influential in many fields, including economics, sociology and political science.

Max Weber categorised social action into four main types. These typologies provide a framework for understanding the different motivations that can guide human behaviour:

- Traditional action: This type of action is guided by customs and habits. Individuals act almost automatically, without giving detailed thought to their behaviour.

- Affective or emotional action: In this case, the action is determined by the individual's current emotions and feelings. These actions are often spontaneous and not calculated.

- Rational action in relation to values: Here, action is guided by ethical, religious or moral beliefs or values. People act according to what they believe to be good or right, even if this does not necessarily bring them personal benefit.

- Rational purposeful action: In this type of action, the individual has a specific objective and uses reason to plan and act in order to achieve that objective. The individual evaluates the most effective means of achieving his end, and his action is guided by this rational analysis.

Weber's categories of action provide a useful framework for understanding how individuals decide to act in different situations. It is important to note that these categories are not mutually exclusive, and a particular action can often be understood as falling into more than one of these types at the same time.

According to Max Weber, the modernisation of society is accompanied by a process of increasing rationalisation, i.e. a transition from more traditional or emotional forms of action to more rational forms of action. This process of rationalisation is reflected in many aspects of modern society, including bureaucracy, science, technology and, of course, politics. In politics, rationalisation can manifest itself in a number of ways. For example, it may involve the transition from an authority based on custom or tradition to one based on codified laws and regulations. Similarly, it may involve the replacement of political leaders chosen for their hereditary status or charisma with professionally trained civil servants who are selected and promoted on the basis of merit and competence. On the other hand, Weber argued that this rationalisation of society and politics could have negative effects, particularly in that it leads to a "disenchantment of the world". In other words, while rational actions can be more effective, they can also be perceived as more impersonal and meaningless, leading to a certain alienation. Finally, it is important to stress that, although Weber observed a tendency towards rationalisation, he did not claim that all actions become entirely rational in modern societies. Other types of action - emotional, traditional and value-rational - continue to play an important role in our social and political life.

According to Weber, the process of rationalisation is closely linked to modern institutionalisation. In this context, institutionalisation refers to the way in which actions, behaviour and social interactions are organised and regulated in a modern society. As society becomes more modern and rationalised, we see an increasing formalisation and standardisation of social and political structures. This can take the form of bureaucracies, laws and regulations, or standardised procedures in various sectors, such as education, health, the economy and, of course, politics. Institutionalisation can be seen as a means of codifying rational action and making it predictable. By creating formal institutions with clear rules and procedures, society seeks to minimise uncertainty and facilitate coordination between individuals. This is reflected in concepts such as the rule of law, where decisions are taken according to established principles rather than on the basis of individual discretion, or representative government, where political leaders are elected according to defined processes.

Weber emphasised the importance of rationalisation in modern society, in the process of industrialisation and bureaucratisation. However, it is important to note that this idea of progress towards rationality does not necessarily mean a total suppression of emotion or the irrational. In fact, even in the most modern and rationalised societies, emotions, cultural values and personal beliefs still play an essential role in individual and collective actions. On the other hand, rationalisation itself can sometimes lead to unintended or paradoxical consequences. For example, Weber spoke of the 'steel cage' of rationalisation, to refer to the feeling of constraint and dehumanisation that can be generated by an extremely bureaucratised and rationalised environment. That said, the general idea is that, in the process of modernisation, there is a growing tendency to structure society and the actions of individuals on the basis of logic, efficiency and rational calculation, rather than on traditions or unreflected emotional impulses.

Max Weber, one of the founders of sociology, introduced the notion of rational action to designate human behaviour guided by a logical evaluation of the options available to achieve a given objective. According to Weber, an action is rational if it is guided by a considered calculation of the most effective means of achieving a particular objective. Rational choice theories, which were developed later in the 20th century, are based on this idea of rational action. They assume that individuals are rational actors who make choices to maximise their utility, i.e. the benefit they derive from their actions. These theories are used in many areas of the social sciences, including economics, political science, sociology and psychology. They have been used to explain a variety of human behaviours, from economic decisions to political choices.

Rational choice theory is an important development in the social sciences that stems from the idea of rational action, and has been used to analyse a variety of phenomena, including politics. According to this theory, individuals are seen as rational actors who make choices based on their personal preferences and the information available to them in order to maximise their utility. This approach has been used to explain phenomena such as electoral behaviour, the formation of political coalitions, the development of regulations and many other aspects of political life. From this perspective, political action is seen as a kind of choice 'economy' in which actors (such as voters, legislators, political parties, etc.) make decisions on the basis of their preferences, expected costs and benefits.

Colin Campbell is a political theorist who has used the economic model of the rational actor to explain political behaviour. This is based on the premise that individuals are rational actors who make decisions on the basis of a cost-benefit calculation. This approach, also known as rational choice theory, assumes that individuals seek to maximise their utility, i.e. to obtain the greatest possible benefit while minimising their costs. Applied to politics, this theory suggests that individuals make their political decisions - such as voting for a certain candidate or supporting a particular policy - according to how they believe these decisions will maximise their personal benefit. This benefit can be material (for example, policies that will improve their economic situation), but it can also be immaterial (for example, the feeling of being in line with their values).

In the economic system, rational choice theory assumes that each individual acts to maximise his or her own self-interest based on a cost-benefit analysis. This analysis consists of evaluating the advantages (benefits) and disadvantages (costs) of each possible option, in order to make a choice that maximises their net gain. For example, a consumer may weigh up the cost of buying a good against the utility or pleasure he or she will derive from it. An investor can weigh the cost of an investment (the purchase price and the potential risk) against its expected return. Similarly, a company can weigh up the cost of hiring an additional employee against the potential benefit of increased productivity.

Rational choice theory, which originated in economics, is often seen as a utilitarian view of human action. According to this theory, individuals make decisions by seeking to maximise their personal utility, in other words by weighing up the costs and benefits of each option. As for the collectivist aspect, this is another angle of discussion. Although individuals seek to maximise their own benefit in rational choice theory, the aggregation of these individual behaviours can lead to outcomes that are beneficial for society as a whole. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes, what an individual does to maximise his or her own benefit can have negative consequences for the group or society, leading to what is known as a "prisoner's dilemma" or a "commons problem". In any case, the application of rational choice theory to politics has led to a variety of models and theories, including voting theory, game theory in politics, and the theory of political institutions.

John Campbell and James Rule contributed to rational choice theory in sociology and political science, emphasising the idea that individuals seek to maximise their self-interest in a context of constraints and opportunities. This approach is based on the idea that political action, like economic action, is guided by the logic of rational calculation. In this view, an individual makes political decisions by weighing up the potential costs and benefits of each option, just as an economic consumer or producer might do. For example, a voter might decide who to vote for by evaluating the positions of each candidate on issues that are important to him or her and estimating the probability that each candidate will be able to implement his or her preferred policies. According to the framework of rational choice theory, an actor (whether economic or political) will weigh the potential benefits of an action (the benefits) against its costs. If the benefits are greater than the costs, then the action is considered "profitable" and so, in theory, the actor will choose to carry it out. In the political context, for example, an elected official may consider a new policy or initiative. To determine whether it is worth implementing, he or she can weigh up the costs (such as the resources needed to implement it and potential political opposition) against the benefits (such as popular support gained, improved community well-being, etc.). If the benefits are perceived to outweigh the costs, then the policy can be adopted.

By relying solely on a cost/benefit analysis, we risk favouring a purely opportunistic logic, sometimes to the detriment of taking other important considerations into account. This can lead to decisions that favour personal or immediate interest over collective or long-term well-being. For example, a politician might be tempted to avoid unpopular but necessary policies for fear of losing votes at the next election. In an economic context, a company might be tempted to make choices that maximise its profits in the short term, even if this means ignoring the environmental or social consequences of its actions. This is why it is essential to integrate ethical and moral values into decision-making, as well as taking into account the long-term effects and impacts on society as a whole. This is where government regulation and a commitment to social responsibility can play a crucial role. In the political arena, altruism and a sense of public service are essential values. Leaders must be prepared to take difficult decisions, even if they may be unpopular, if they are in the long-term interests of society. Similarly, in the economic sphere, the notion of corporate social responsibility underlines the importance of companies taking into account the impact of their actions on society and the environment, and not just on their profits.

Rational choice theory postulates that in politics, as in other areas of life, individuals are largely motivated by cost-benefit considerations. They seek to maximise their own benefit (or utility) and minimise their cost. This logic is often applied to explain a multitude of behaviours, from a citizen's decision to vote (or not to vote) to a political leader's negotiation of an international agreement. According to this view, individuals are seen as instrumentally motivated, i.e. they seek to achieve specific goals through their actions. The emphasis is on effectiveness and efficiency in achieving these objectives. This is why we speak of a "utilitarian" logic, where each decision is evaluated in terms of its expected advantages and disadvantages.

In the context of political reality, the idea is that individuals are motivated by objectives that can be measured in terms of costs and benefits. It is important to stress that these 'costs' and 'benefits' can be not only material (such as money or power), but also immaterial (such as prestige, influence, or even personal satisfaction). However, while this utilitarian and rational choice perspective can help explain much political behaviour, it is not without its limitations. Firstly, not all individuals are necessarily motivated by the same set of costs and benefits, and their motivations may change over time. Secondly, it can be difficult to measure costs and benefits accurately, particularly when they are intangible. In addition, this perspective may tend to underestimate the role of values, emotions, ideology, and other non-economic factors in driving political action. For example, some individuals or groups may be prepared to bear significant costs (including personal risks) to defend their beliefs or principles.

Within the framework of rational choice theory, there are two major constraints that guide an individual's action:

- Minimising costs: This means that the individual will seek to achieve his objective with the fewest possible resources, whether material (money, time) or immaterial (effort, stress). This constraint encourages efficiency, i.e. the achievement of a maximum of objectives with a minimum of resources.

- Maximising benefits: In other words, the individual will seek to gain the greatest possible advantage from his action. This benefit may be material (gain of money, acquisition of goods or services) or immaterial (personal satisfaction, social recognition, feeling of power or influence).

These two constraints are often in tension. Minimising costs may mean sacrificing certain benefits, while maximising benefits may mean accepting higher costs. So rational choice is often a balancing act between these two constraints.

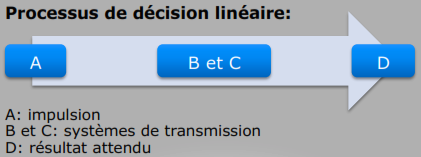

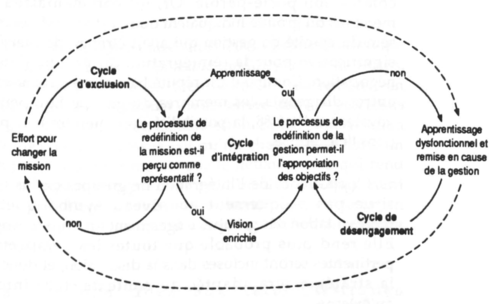

Rational choice theory is based on a linear and predictable view of the decision-making process. In this model, an individual or group of individuals begins by identifying an objective (point A), then determines the means to achieve it (points B and C), anticipating that this action will lead to a certain result or "output" (point D). This process assumes that the individual has perfect or at least sufficient knowledge of the situation, the options available and their potential consequences. In reality, however, the decision-making process is not always so linear or predictable. Individuals may not have complete knowledge of the situation, the options available may change along the way, and the outcome may be influenced by unforeseen factors. Furthermore, the decision taken may itself change the situation and create new options or constraints for future decisions. For these reasons, although rational choice theory is a useful tool for understanding and analysing human behaviour, it has its limitations and cannot account for all the complexities and uncertainties of real-life decision-making.

Rational choice theory assumes that the environment in which decision-making takes place is rational and predictable. This perspective postulates that individuals can obtain all the information they need to carry out a rational cost-benefit analysis, and that conditions will remain stable throughout the decision-making process. However, in the real world, this environment is often full of uncertainties and constantly changing dynamics. Individuals cannot always accurately predict the outcome of their actions or the impact of external factors. Moreover, information is often incomplete or imprecise, and individuals have limited cognitive capacity to process and analyse all the information available. Consequently, although rational choice theory can be useful for analysing certain behaviours and situations, it does not fully capture the complexity and uncertainty of decision-making in a real context. This is why other theories, such as the theory of behaviour related to bounded rationality or prospect theory, have been developed to complement and nuance this perspective.

The assumption remains that the best way to make policy is to limit one's convictions. You have to assess the overall consequences of the action or you move on to a more complicated scheme for preventing action. This underlines the constant debate between idealism and pragmatism in politics. On the one hand, we have idealism, which argues that political actors should act according to their deepest convictions and principles, whatever the situation. On the other hand, pragmatism argues that political decisions should be guided by a realistic assessment of costs, benefits and potential consequences. In this context, the hypothesis suggests that effective policymaking may require limiting one's beliefs (i.e. being more pragmatic) and carefully assessing the overall consequences of actions. In other words, it means taking a more calculated and pre-emptive approach to action, rather than being guided solely by idealistic principles. This can be more complex, as it involves navigating between multiple interests, constraints and uncertainties, but it can also lead to more sustainable and realistic outcomes.

Linearity is described as a form of predictability in action and decision-making. This type of thinking is associated with rationality, assuming an orderly and logical sequence of events with no deviations or unforeseen events. The idea is to follow a straight line from the initial idea to its final outcome, with each stage of the process following one another in a coherent and predictable manner. However, reality can often be more complex, and the course of events can be influenced by a multitude of unforeseen factors. This is why some researchers and theorists argue that action and decision-making need to be more flexible and adaptive, able to respond to uncertainties and changes in context. In this sense, an overly linear approach could be limiting, as it is not capable of adapting to unforeseen events or changes in direction.

In a rational world, individuals are seen as actors capable of making logical and structured choices. They evaluate the options available, consider the advantages and disadvantages of each choice, and select the option that seems most beneficial or appropriate. This decision-making process is often described as rational because it is based on an objective assessment of the facts, logic and the search for the best possible outcome.

One of the major criticisms of rational choice theory is that it can fail to take into account the cultural, social and emotional factors that influence people's decisions. By focusing solely on the economic or utilitarian aspect, this theory can neglect important elements that shape the human experience. For example, cultural rituals may be considered rational in some cultures, even if their purposes are not strictly economic or utilitarian. They may have a profound meaning and be considered indispensable to the members of the culture in question. Similarly, decisions may be influenced by emotional factors, personal beliefs, social pressures or cultural norms that are not necessarily aligned with maximising utility or economic value. This is why it is important to take a more holistic and nuanced approach to understanding human decision-making.

Rational choice theory is an economic approach to decision-making which assumes that individuals are fundamentally "rational actors" who seek to maximise their utility or profit. This theory has been widely applied in economics, politics, sociology and other disciplines to explain various social phenomena. However, despite its usefulness, rational choice theory has also been criticised for its simplicity and its overly individualistic, economic approach to decision-making. In particular, some argue that it ignores or neglects other important factors that can influence human behaviour, such as emotions, social norms, cultural beliefs and moral values. Therefore, although rational choice theory can be a valuable tool for understanding certain aspects of human decision-making, it should not be used alone and should be complemented by other approaches and theories that take into account the complexity and diversity of human experience.

The linear view of the decision-making process can be limiting. In this model, the decision-making process is generally represented as a logical and ordered sequence of steps, where a problem is identified, solutions are generated and evaluated, and a decision is made. In reality, the decision-making process is often far more complex and chaotic, involving a multitude of factors and stakeholders. Decisions are rarely taken in a vacuum, and are often influenced by social dynamics, political pressures, economic constraints, cultural norms and other contextual factors. In addition, the linear view can sometimes be too simplistic and fail to take into account how decisions are actually made in the real world. For example, it may not take into account the uncertainties, ambiguities, emotions, cognitive biases, and human factors that can influence the decision-making process. For these reasons, many researchers and practitioners have begun to adopt more complex and dynamic decision-making models, which take into account the complexity and uncertainty inherent in the decision-making process.

Action through the prism of game theory[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Game theory is another major perspective in the study of rational action, and offers an alternative to the linear approach to decision-making. Rather than assuming that decisions are made in isolation, game theory recognises that the actions of an individual or entity are often interdependent and can influence or be influenced by the actions of others. Within this framework, rationality implies not only evaluating one's own costs and benefits, but also anticipating the actions of others, taking into account their own interests and motivations. It is a fundamental concept in many fields, from economics and politics to the social sciences and even biology.

Game theory helps us to understand how individuals or entities interact and make decisions in a competitive or cooperative environment. It examines situations where the outcomes for an actor depend not only on his own actions, but also on those of others. Consequently, it goes beyond simple cost-benefit analysis to include a strategic assessment of the potential actions of other players. This does not mean, however, that game theory eliminates the idea of rationality. On the contrary, it is based on the idea of strategic rationality, where individuals act in such a way as to maximise their own interests, taking into account the potential reactions of others. Although game theory provides a more complex and nuanced perspective on decision-making, it also has its limitations. For example, it often assumes that players are perfectly rational and have perfect information, which is not always the case in the real world. Furthermore, like all theories, it is a simplification of reality and cannot capture all the subtleties and complexities of human interaction.

Game theory offers an interactionist perspective on action and decision-making. This perspective recognises that the behaviour of individuals is determined not only by their own rational choices, but also by external factors, including the actions and expectations of others. In this context, individuals are not simply autonomous entities making independent choices based on a cost-benefit analysis. Instead, they are seen as actors engaged in a dynamic and mutually influential interaction with other actors. Each of their choices is made in the context of this interaction, taking into account not only their own interests, but also those of others and how their actions may affect the behaviour of others. This interactionist perspective also allows account to be taken of constraints that may limit an individual's choices. These may include external factors, such as social or legal rules, or internal factors, such as personal beliefs or moral values. Ultimately, game theory provides a framework for understanding how individuals navigate these complex interactions and constraints, making strategic choices that take into account both their own interests and those of others.

Game theory is based on the idea that the decisions of an individual or an entity (such as a company or a country) are influenced by the anticipated decisions of others. In this sense, the decision-making process is like a game, where players strategise according to what they expect others to do. Each player, while seeking to maximise its own benefit, must take into account the potential actions and responses of its 'rivals' or other stakeholders. For example, if a company is considering raising its prices, it must take into account the possibility that its competitors may lower theirs in response, which could lead to a loss of market share. Similarly, in the political context, a government or party must take into account the potential responses of its opponents when making decisions. Political choices are therefore not taken in isolation, but are the result of an interactive process that takes account of the whole political 'game'.