State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance

Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory ● The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic ● Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory ● The notion of "concept" in social sciences ● History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts ● Marxism and Structuralism ● Functionalism and Systemism ● Interactionism and Constructivism ● The theories of political anthropology ● The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas ● Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science ● An analytical approach to institutions in political science ● The study of ideas and ideologies in political science ● Theories of war in political science ● The War: Concepts and Evolutions ● The reason of State ● State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance ● Theories of violence in political science ● Welfare State and Biopower ● Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes ● Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences ● The system of government in democracies ● Morphology of contestations ● Action in Political Theory ● Introduction to Swiss politics ● Introduction to political behaviour ● Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy ● Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation ● Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation ● Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations ● Introduction to Political Theory

The modern state is a central concept in political science. It refers to a territorial entity that exercises sovereign authority and whose government has the power to make and enforce laws, administer justice and control resources. This entity is characterised by its legitimacy, its sovereignty, its delimited territory and its people.

As a discipline, political science is devoted to the study of the modern state, its institutions and the processes that shape public policy. It also examines power structures, ideologies, international politics and various forms of governance. The modern state plays an essential role in defining a country's political identity. It is the entity that organises and defines the political, social and economic life of a nation. The modern state is also responsible for protecting human rights and ensuring social justice. The concept of the modern state has evolved over time. Today, it is often associated with concepts such as the welfare state, which suggests that the state has a responsibility for the social and economic well-being of its citizens. Moreover, with globalisation and contemporary challenges such as climate change and cyber security, the role and nature of the modern state are constantly evolving. By analysing these transformations and studying different models of the state around the world, political science plays a crucial role in our understanding of the modern state.

The state can be understood and analysed from a number of angles, highlighting different facets of how it functions.

- The State as a set of norms - normative political theories: From this perspective, the State is seen as a set of principles, rules and norms that govern the way it functions and the way its citizens are expected to behave. It is the study of the ideal of the state, the ethical and moral principles that should guide its actions. Normative political theories seek to define what a good state should be, what its objectives should be and how it should achieve these objectives.

- The state as a site of power and authority: Here, the focus is on the state as the entity that holds and exercises power. The state is seen as the ultimate authority that controls society and has the power to enforce its laws and rules. The aim is to explore how the state uses this power, how it is contested, negotiated and distributed, and how it influences social and political relations.

- The state as a set of institutions and their effects: In this perspective, attention is focused on the state as a set of institutions - such as the government, the judiciary, public administration, etc. - that have concrete effects on society. - which have concrete effects on society and citizens' lives. This approach examines how these institutions are structured, how they interact, how they influence public policy and how they affect the well-being of citizens.

These three approaches provide a useful analytical framework for understanding the modern state, its roles and functions, and its impact on society. They also provide a basis for understanding the challenges and opportunities facing the state in the contemporary context.

The Concept of the State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Definition of the State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The state is a complex concept that has evolved over time and varies according to historical and cultural contexts. Basically, the state is a political entity with sovereignty over a defined territory and population. It has the power to make and enforce laws, impose order, control and defend its territory, and conduct relations with other states.

The foundations of the state can be traced back to antiquity, with early examples in Egypt, Greece and China.

- In ancient Egypt, the concept of the state was linked to the figure of the pharaoh, who was considered a living god and held absolute power over the territory and the people. The state bureaucracy was organised to serve the pharaoh and administer the country.

- In ancient Greece, the idea of the city-state emerged, where an urban territory and its surrounding countryside formed an independent political unit, or "polis". It was a community of free citizens who participated directly in political decision-making, a concept that laid the foundations for democracy.

- In ancient China, the state was organised around the notion of the 'Mandate of Heaven', according to which the ruler, or emperor, had the right to govern as long as he maintained order and prosperity. The role of the state was to ensure social harmony and maintain cosmic order.

The modern concept of the state as we know it today began to take shape in Western Europe at the end of the Middle Ages, with the decline of feudalism and the advent of the Renaissance. During the feudal period, power was largely decentralised. Local lords held considerable power over their lands and subjects, and the king's authority was often limited. In addition, the papacy and the empire had a major influence on political and social life. However, with the decline of the feudal system and the rise of cities and trade during the Renaissance, power began to be centralised. Kings began to consolidate their authority, establish centralised administrations and assert control over their territories. It was at this time that the first nation-states emerged, with defined borders and centralised authority. The declining influence of the papacy and imperial institutions also played a key role. With the decline of these supra-national authorities, kings were able to assert their sovereignty and take control of their territory and population. These transformations laid the foundations of the modern state. However, it should be noted that the process of state formation differed greatly from region to region and country to country, and that the concept of the state has continued to evolve and develop to the present day.

The emergence of the modern state is a vast and complex subject for study, and many scholars have contributed to our understanding of this process. One of the most important is undoubtedly Charles Tilly, the American sociologist and political scientist best known for his work on the evolution of European states. Tilly put forward the idea that the emergence of the modern state in Europe was closely linked to war. In his book "Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1992", he argues that those states that succeeded in mobilising resources for war succeeded in centralising and developing. In other words, the need to raise armies, collect taxes to finance wars, and maintain internal order led to the creation of centralised administrations and the consolidation of state authority. He also emphasised the importance of internal social conflict in state formation, in particular the way states responded to revolts and uprisings. Tilly's theory has had a significant influence on our understanding of the evolution of the state. However, it should be noted that his theory applies primarily to Europe, and that the emergence of the modern state can vary considerably according to historical, cultural and geographical contexts.

For Charles Tilly, in order to account for the formation of the modern state, three major historical dynamics need to be taken into account:

- importance of war and the growing tendency of the state to monopolise coercion, which will therefore lead to a contrast between the state sphere, where violence reigns, and the sphere of civil life, where non-violence prevails. In his view, war played a central role in the emergence of the modern state in Europe, because of its impact on political and social organisation. According to Tilly, the need for sovereigns to commit significant resources to warfare, particularly as a result of developments in military technology (such as the introduction of gunpowder in the 15th century), led to increased centralisation of power. To finance increasingly costly wars, sovereigns had to develop an efficient bureaucracy to collect taxes on a regular and systematic basis. This led to the creation of a "state budget", a major innovation in the organisation of the state. In addition, the need to recruit men for war and to provide equipment and food supplies led to the creation of specialised government departments. This also contributed to the growth of the state bureaucracy. Finally, the state's ability to levy taxes on its subjects was accompanied by a growing demand from them to have a say in government. This led to the emergence of public assemblies and the establishment of certain forms of political representation. Increasingly costly wars required growing resources, prompting rulers to develop more efficient and regular systems of taxation. The management of these funds led to the conceptualisation of the 'state budget', an innovation that remains central to the management of modern states. To support these war efforts, the rulers also had to develop an increasingly complex bureaucracy. This included the creation of government departments dedicated to the mobilisation and maintenance of armies, the provision of war material and the supply of food. Bureaucracy was also required to administer the more robust taxation system. In addition, as the state increased its capacity to levy taxes, subjects began to demand greater representation and accountability from their rulers. This dynamic contributed to the emergence of public assemblies and the establishment of certain forms of political representation. In short, Tilly's thesis suggests that the dynamics of war were a major factor in the emergence of the modern state and its bureaucracy. However, it should be noted that this theory has its critics, and that other factors may also have played an important role in the evolution of the state.

- The advent and economic development of market capitalism. From the 15th century onwards, there was a profound economic transformation linked to the rise of trade and finance. From the 15th century onwards, the rise of trade and finance led to profound economic transformations. The development of merchant capitalism, with its predominance of commercial and banking activities, led to growing urbanisation and an intensification of trade. This led to the emergence of a new social group, the bourgeoisie, comprising merchants and traders who profited from the production and trade of goods. Unlike the peasantry, the bourgeoisie was a politically free social group that played a key role in financing states, as it accumulated capital and lent money to rulers. Charles Tilly also emphasised the importance of the monetarisation of the economy in this process. In his view, in regions where the economy was highly monetarised, the most centralised and powerful states tended to emerge. Moreover, the presence of trading cities within a state's territory had a significant influence on its ability to mobilise resources for war.

- changes in ideology and collective representations that will lead to a strengthening of the state's legitimacy. Changes in ideologies and collective representations have also played an important role in strengthening the legitimacy of the modern state. One major transformation was the emergence of individualism, which marked a break with the collective consciousness of the feudal era. As the historian George Duby illustrated in his book "Les trois ordres", feudal ideology was structured around a trifunctional order: those who pray (the clergy), those who fight (the knights) and those who work (the peasants). In this system, individual membership of an order was largely predetermined. With the emergence of individualism, however, this concept began to change. Individuals began to see themselves not as members of a predetermined order, but as contracting parties in relations with the sovereign, the rulers and the government. For example, a merchant might see himself as an individual capable of negotiating his relationship with different rulers, and might choose to offer his loyalty to the one who levied the fewest taxes. This development has had a significant impact on the legitimacy of the state. Whereas the legitimacy of the feudal state was often based on respect for tradition and established hierarchies, the legitimacy of the modern state is increasingly based on its ability to respect and protect individual rights and interests. This has led to major changes in the way the state is organised and governed.

The predominant form of state today is the nation state. In fact, the idea of the nation state is closely linked to the idea of national sovereignty, which means that a state is governed in the interests of its own national population. The idea of the nation state began to grow in importance in Europe in the 19th century, when it was put into practice as part of the unification movements in Italy and Germany. These movements sought to bring together linguistically and culturally similar territories and populations into a single political entity, thereby creating a "nation state". In the twentieth century, the concept of the nation state spread well beyond Europe. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, for example, led to the creation of Turkey as a nation state. The decolonisation of the 1950s and 1960s also gave rise to a large number of new nation states. In many of these cases, the borders of the new states were drawn by the retreating colonial powers, often without taking into account the ethnic or cultural realities on the ground. This often led to tensions and conflicts that continue to this day.

According to Weber, an influential German sociologist, the state is a "human community which, within the limits of a determined territory... successfully claims for itself the monopoly of legitimate physical violence."[1] This definition emphasises three main aspects of the state:

- Territoriality: the state must control a specific territory. This is the spatial dimension of the state, referring to the geographical area over which the state exercises its power.

- Community: the state is a community of people. This is the human dimension of the state, referring to the population that the state governs.

- Monopoly of legitimate violence: the state has the exclusive right to use force to maintain order and enforce its rules. This is what distinguishes the state from other types of political organisation.

Weber's definition puts forward the idea that the legitimacy of the state rests largely on its ability to monopolise the use of physical violence in a legitimate manner. This capacity is essential for maintaining social order and for the state to be able to exercise its authority effectively. It should be noted that although this definition is widely accepted, it has also been criticised and debated. Some argue, for example, that the legitimacy of the state rests not only on its monopoly of violence, but also on its ability to provide public goods, protect human rights, promote social justice and so on.

The Territory as part of the State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Territory is an essential element in the definition of the State, and distinguishes it from the notion of "nation". In simple terms, territory refers to the geographical space delimited and controlled by a state. It includes not only land, but also resources, airspace and, in some cases, territorial waters and exclusive economic zones.

On the other hand, the notion of "nation" is often defined in more cultural or ethnic terms. A nation is generally understood as a group of people who share a common identity based on characteristics such as language, culture, ethnicity, religion, traditions or a common history. A nation may or may not coincide with the borders of a state. For example, the "Navajo nation" in the United States, or the "Kurdish nation" in the Middle East, are nations that do not correspond to a specific territorial state.

The idea of the nation state attempts to combine these two concepts, proposing the ideal of a state where the population shares a common national identity. In practice, however, many states are multinational or multicultural, and the perfect alignment of nation and state is rare.

The concepts of state and nation are not necessarily strictly linked. The nation generally refers to a group of people who share a common identity based on cultural, ethnic, linguistic or historical characteristics, and this identity may exist independently of a specific territory or state.

The example of the Jewish community before the creation of the State of Israel illustrates this idea perfectly. For thousands of years, the Jews saw themselves as part of a nation, despite the fact that they were scattered across many different countries and regions. This sense of belonging to a Jewish nation has persisted despite the absence of a specifically Jewish territory or state.

It should also be noted that there are nations that do not have their own state, sometimes referred to as "stateless nations". The Kurds, for example, are often cited as a nation without a state, because although they have a strong sense of national identity, they do not have their own independent country. Conversely, many states are multinational or multi-ethnic, home to several groups that may consider themselves separate nations. Belgium, for example, includes both Flemings and Walloons, each with their own distinct language and culture.

In short, while the state refers to a political and territorial entity, the nation is a more fluid and subjective concept, based on a sense of belonging to a community. The two do not always coincide.

Population: essential to the structure of the State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The nation state, as the dominant model of political organisation, has strengthened the link between nation and state, and by extension, the link between nation and territory. The idea behind the concept of the nation state is that each 'nation', or people with a common cultural identity, should have its own state. In an ideal nation state, the borders of the state would coincide perfectly with the extent of the nation.

However, the reality is often more complex. There are many nations that do not have their own state. The Kurds are a commonly cited example. On the other hand, many states are multi-ethnic or multinational and do not have a single 'nation' that corresponds exactly to their borders.

As far as "diaspora nations" are concerned, this is a term that is generally used to refer to groups of people who share a common national identity but who are scattered across different countries or regions. Gypsies, also known as Roma, are an example of this. Although they have no specific territory or state associated with them, they have a common culture, language and history that constitute a national identity.

These examples show that the relationship between nation, state and territory can vary considerably and is often much more complex than it first appears.

The state, as a concept and as a tangible reality, is a human construct. It is a product of history, power relations, ideologies and institutions created by human beings. The State is not only a political and legal entity that governs a certain territory, it is also a community of people. Without its citizens, a state would have no raison d'être. The people who live in a State are both the subjects of its power and the beneficiaries of its services. They contribute to its prosperity through their work, pay taxes to finance its activities, obey its laws and participate (in most cases) in its political process. In addition, the state has a responsibility to its citizens: to protect their rights and freedoms, to provide public services, to maintain order, and to promote the general welfare. The relationship between a state and its citizens is therefore fundamental to its legitimacy and functioning.

This is why it can be said that a State without inhabitants is inconceivable. Without people to constitute it, govern it and be governed by it, a State would have neither substance nor meaning.

The monopoly of legitimate physical coercion: a unique aspect of the State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In many historical societies, power, violence and coercion were much more diffuse. The monopoly of legitimate violence by the state is a characteristic of the modern state system, but this was not always the case. Before the emergence of modern states, the capacity to exercise violence was often distributed between different groups and institutions. For example, in the Middle Ages in Europe, legitimate violence was shared between a variety of actors, such as feudal lords, the Church, autonomous towns and so on. Each of these actors could exercise a form of legitimate violence in certain contexts. With the emergence of the modern state, the process of centralising power gradually led to the establishment of the state's monopoly on legitimate violence. This development is often linked to the need to maintain order, secure borders and control internal conflicts. However, even in modern states, violence and coercion can sometimes be exercised by other actors, such as criminal groups or paramilitary organisations. These situations are generally seen as challenges to the authority of the state and its monopoly on violence.

According to Tilly, "the activity of the state in general, and hence its emergence, has created a sharp contrast between the violence of the state sphere and the non-violence of civilian life. The European states provoked this contrast, and they did so by setting up reserved means of coercion and by forbidding civilian populations access to these means. The difficulty or significance of the change should not be underestimated; for most of European history, most men were always armed. Moreover, in all states, local and regional potentates had sufficient means of coercion at their disposal, far greater than that of the state if they were brought together in a coalition. For a long time in many parts of Europe, nobles had the right to wage private wars, and bandits flourished almost everywhere throughout the 17th century. In Sicily, the mafiosi, professionals of patented and protected violence, continue to terrorise the population today. Outside the control of the state, people often profited fruitfully from the reasoned use of violence. Nevertheless, since the seventeenth century, rulers have succeeded in tilting the balance in favour of the state rather than their rivals; they have made the carrying of personal weapons illegal and unpopular, outlawed private militias and succeeded in justifying clashes between armed police and armed civilians. At the same time, the expansion of the state's own armed forces began to outstrip the arsenal available to potential domestic rivals".

This passage from Charles Tilly highlights a key change in the transition to modern states: the growing monopoly of legitimate violence by the state. This process has not been easy or quick, because in the past many actors could legitimately use force. For example, feudal lords could wage private wars, and many ordinary men were armed. However, over time, states gradually succeeded in restricting access to the means of coercion and monopolising violence. They banned private militias, made the carrying of personal weapons illegal and unpopular, and established powerful state police forces and armies. At the same time, they delegitimised the use of force by other actors, such as nobles and bandits. However, Tilly notes that this process was not entirely complete or uniform. In Sicily, for example, organisations such as the mafia continued to use violence effectively, despite state control. Moreover, in many parts of the world, private and non-state violence remains a major challenge to public order and the legitimacy of the state. Tilly's quote therefore highlights the importance of the monopoly of legitimate violence for the constitution of modern states, but also reminds us that this monopoly is never absolute and is often contested.

One of the key aspects of Max Weber's definition of the modern state is the monopoly of legitimate violence. In other words, in a well-organised and stable society, only the state has the right to use force to maintain order and enforce the law. This monopoly is crucial to the functioning of the modern state. It enables the state to maintain public order, protect citizens' rights and freedoms, and enforce laws effectively. At the same time, it limits the scope for non-state actors, such as criminal groups or individuals, to use violence to achieve their ends. However, it should be noted that this monopoly of the state is not always complete or uncontested. There are many cases where non-state actors exert significant violence, whether through organised crime, domestic violence or armed rebellion. Moreover, in certain circumstances, the state itself can abuse its monopoly on violence, leading to human rights violations and tyranny. Overall, the state's monopoly of violence is a key feature of the modern state, but it is also a source of many challenges and tensions.

Le concept de l'État ayant le monopole de la force légitime est une idéalisation qui ne reflète pas toujours la réalité complexe et nuancée sur le terrain. De nombreux pays à travers le monde ont des groupes armés non étatiques qui contestent le monopole de l'État sur l'usage de la force. En effet, dans de nombreux cas, ces groupes sont capables de contrôler des territoires, d'exercer une autorité substantielle sur les populations locales et de mener des opérations militaires ou paramilitaires contre l'État ou d'autres acteurs. L'Armée Républicaine Irlandaise (IRA) en Irlande du Nord et le Hamas dans les Territoires palestiniens sont des exemples notables de tels groupes. Ces situations soulèvent de nombreuses questions difficiles concernant la légitimité, l'autorité et le contrôle de la violence. Par exemple, quand un groupe non étatique contrôle un territoire et exerce une autorité sur sa population, peut-il être considéré comme un État de facto ? Et si un groupe non étatique a le soutien d'une grande partie de la population locale, est-ce que cela lui donne une certaine légitimité pour utiliser la force ? Ces questions sont très controversées et il n'y a pas de réponses simples. Cependant, elles soulignent le fait que la réalité de la politique, du pouvoir et de la violence est souvent beaucoup plus complexe que les théories simplifiées de l'État et du monopole de la violence peuvent le laisser croire.

The legitimacy of the use of force by the state is a concept that depends largely on perspective and context. The use of force may be considered legitimate if the government exercising it is itself considered legitimate and if the use of force is considered necessary and proportionate to maintain public order, national security or to enforce the law. However, it is important to stress that even if a government is generally considered legitimate, this does not mean that all its uses of force will necessarily be seen as legitimate. There are many examples in history where governments have used force in abusive or oppressive ways, which have been widely condemned as illegitimate. In addition, the question of legitimacy can be heavily influenced by factors such as culture, religion, history, political ideologies and power relations. For example, what is considered a legitimate use of force in one society may be considered totally illegitimate in another. Finally, it should be noted that the notion of legitimacy is not always clearly defined or universally accepted. What may be considered a "freedom fighter" for some may be seen as a "terrorist" for others. This ambiguity and subjectivity can often make discussions about the legitimacy of the use of force very complex and controversial.

In some cases, armed groups may justify the use of force as a response to repression or perceived injustice committed by the state or other legitimate authorities. These groups may argue that they are using violence to defend themselves, their community or an oppressive authority. This is a common reason for armed conflict, guerrilla warfare or resistance movements. However, it is important to note that although these groups may claim legitimacy for their use of violence, this does not necessarily mean that their use will be recognised as legitimate by others, including the international community, other citizens or even other members of their own community. Moreover, the use of violence by these groups can often result in human rights violations, collateral damage and other negative consequences for innocent civilians. Ultimately, the question of whether or not the use of force is legitimate can be very complex and controversial, and can depend on a multitude of factors, including the specific context, the motivations of the actors involved, and the norms and values of the society.

Contemporary definitions of the State[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The complex and multidimensional nature of the state means that it cannot be reduced to a simple or universal definition. The multiple definitions of the state reflect different disciplinary perspectives, theoretical approaches, historical and political contexts, as well as cultural and regional variations.

In different disciplines such as political science, law, sociology, economics or history, the approach to understanding the state varies. For example, a jurist might examine the state from the point of view of legal structure and laws, while a sociologist might focus on power relations and social institutions. Moreover, the conception of the state has evolved over time and varies according to historical contexts. Contemporary definitions of the state may therefore reflect different phases in its historical development. The nature of the state may also vary from one region or culture to another. Western definitions of the state may not apply in the same way in non-Western contexts. Furthermore, the interpretation of the state may be influenced by political ideologies. A Marxist perspective, for example, might see the state as an instrument of the ruling class, whereas a liberal perspective might see it as a neutral arbiter between different social interests. Finally, given the inherent complexity of the state, which comprises a multitude of actors, institutions, rules and processes, it is not surprising that there are many ways of defining it. These various definitions help us to grasp the different facets of the state, and to better understand its role and functioning in different contexts.

The most common definitions include the following:

- Legal definition: A state is a subject of international law with a defined territory, a permanent population, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. This definition, widely used in international law, is often associated with the Montevideo Convention of 1933.

- Max Weber definition: For the sociologist Max Weber, a state is an entity that successfully claims a monopoly on legitimate physical violence in a given territory. This definition emphasises the state's ability to maintain order and enforce the law through its monopoly of legitimate violence.

- Institutional definition: Some political theorists define the state in terms of organisations and institutions. According to this view, a state is a set of political institutions (such as the government, bureaucracies, armed forces, etc.) that possess authority over a specific territory and its population.

As defined by Charles Tilly in his 1985 article War Making and State Making as Organized Crime, states are "[States are] relatively centralized, differentiated organizations, the officials of which, more or less, successfully claim control over the chief concentrated means of violence within a population inhabiting a large contiguous territory."[2] Charles Tilly's quotation from his 1985 article, "War Making and State Making as Organized Crime", offers a succinct but profound definition of the state. According to Tilly, states are "relatively centralised, differentiated organisations, whose leaders claim, more or less, control over the principal concentrated means of violence within a population inhabiting a vast contiguous territory".

This highlights a few key points in his conception of the state:

- Centralisation: States are organisations where power is concentrated and organised around a central authority. This centralisation allows for better coordination and more effective control over the various functions and responsibilities of the state.

- Differentiation: States are made up of many different parts, each with its own roles and responsibilities. This differentiation allows the state to perform a multitude of functions necessary for its survival and effective functioning.

- Control of violence: A crucial aspect of Tilly's definition is the assertion that states claim control over the principal means of violence. This means that they have a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within their territory. This monopoly is essential for maintaining order and the authority of the state.

- Population and territory: The state is also defined by the population it governs and the territory it controls. These two aspects are crucial to the existence and functioning of a state.

Tilly's definition offers a pragmatic and realistic vision of the state, emphasising its coercive capacities and its role as an organised entity with a monopoly on violence.

The definition of the state proposed by Douglass North in his 1981 book "Structure and Change in Economic History" emphasises the importance of violence and fiscal power in structuring the boundaries of the state. North defines the state as "an organisation with a comparative advantage in violence, extending over a geographical area whose boundaries are determined by its power to tax its constituents".[3]

- Comparative advantage in violence: This concept refers to the idea that the state has a greater capacity than other entities to exercise violence legitimately. This enables it to impose its authority and maintain order within its borders.

- Borders determined by the power to tax: North also emphasises the importance of the power to tax in defining the state's borders. The state's ability to levy taxes on its constituents is an essential element of its sovereignty and its ability to function effectively.

- Geographical area: The State is defined by a certain geographical area. The boundaries of this area are determined by the power of the state to exercise violence legitimately and to levy taxes on its constituents.

This definition emphasises the importance of economic and coercive aspects in the conception of the state, while recognising that the power and scope of the state may vary according to its ability to mobilise resources through taxation.

The definition of the state proposed by Clark and Golder in their book "Principles of Comparative Politics" published in 2009 focuses on the use of coercion and the threat of force to rule over a given territory. According to them, "A state is an entity that uses coercion and the threat of force to rule over a given territory. A failed state is a state-like entity that cannot coerce and is unable to effectively control the inhabitants of a given territory."[4] This definition highlights the crucial role of coercion in the exercise of state power. The use of force and the threat of force are seen as key elements of state authority. Clark and Golder also introduced the notion of the failed state. According to them, a failed state is an entity that resembles a state but is incapable of effectively exercising coercion or controlling the inhabitants of a given territory. This concept is important because it allows us to understand the fragility of certain states and the problems that can arise from their inability to exercise authority effectively. In short, this definition emphasises the state's ability to control and reign over a territory through the use of coercion and the threat of force.

In some modern definitions of the state, the notion of legitimacy and monopoly over the use of violence may be attenuated. This may in part reflect the complex reality of a world where non-state actors may also exercise some form of coercion or violence, as is the case with some terrorist or organised crime groups. Yet the notion of territory remains central to most definitions of the state. A state is generally recognised as having control over a specific territory, even if the reality of this control may vary in practice. A state's coercive capacity is not limited to the actual use of force. Sometimes the mere threat of coercion can be enough to maintain order and ensure compliance. Indeed, coercion often works through deterrence: fear of potential consequences can prevent individuals from behaving in undesirable or illegal ways. It is important to note that these definitions are not exhaustive and may vary according to theoretical perspectives and historical and geographical contexts. Ultimately, the study of the state requires a nuanced and multidimensional understanding of its different aspects and functions.

The state, whatever its political regime, maintains its power and order by using some form of coercion or the threat of coercion. This coercion can take many forms, including the enforcement of laws and regulations, the administration of justice, the collection of taxes and the maintenance of public order. Tax coercion is a good example. Taxes are compulsory, and those who fail to pay them can face penalties, fines and even imprisonment. It is through this threat of coercion that the state can raise the revenue needed to provide public goods and services. However, the legitimacy of this coercion is crucial. In a democracy, for example, state coercion is generally perceived as legitimate because it is exercised as part of a political system in which citizens have the power to choose their leaders and influence public policy. In a dictatorship, on the other hand, state coercion may be perceived as illegitimate, particularly if it is used to suppress dissent and violate human rights.

In reality, absolute control of coercion by the state is rarely, if ever, fully achieved. In every society, there are a variety of non-state actors who have some capacity to exercise coercion or resist state coercion. This may take the form of criminal organisations, militant groups, private security companies, religious or traditional communities, among others. These actors can sometimes challenge or complement the state's ability to exert coercion, particularly in areas where the state is weak or absent. For example, in some parts of the world, organised criminal groups or armed militias may exercise effective control over particular territories, openly challenging the state's monopoly on violence. This is why the notion of "comparative advantage" introduced by North is important. Rather than describing the state as having an absolute monopoly on violence, North suggests that the state simply has a comparative advantage in the exercise of coercion. This recognises that, although the state is generally the most powerful actor in a given society, it is not the only actor capable of exercising coercion.

The notion of differentiation is central to the concept of the state. It refers to the distinction between the state and civil society, where the state maintains a degree of autonomy from the social, economic and political forces operating in society. Taxation is a good example of this differentiation. By levying taxes, the state exercises its authority and control over citizens and economic resources. It uses these resources to finance a variety of public functions, including defence and security, but also social services, education, infrastructure and other activities. By controlling these resources and deciding how they are allocated, the state distinguishes itself from civil society and asserts its authority. As Charles Tilly has pointed out, taxation has played a key role in the historical development of modern states. It has enabled states to accumulate the resources needed to finance armies and wars, reinforcing their authority and control over their territories. In addition, taxation has often been used as a tool to unify diverse territories and populations under a single state authority. As a result, the ability to raise and manage taxes effectively is often seen as an essential characteristic of a functional state.

The case of failed states[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Samuel Huntington, in his theory of political order, argues that the form of government (e.g. democracy, autocracy) is less important to the well-being of a society than the degree of government, that is, the ability of a state to effectively administer its policies and maintain order.[5] For Huntington, the effectiveness of a government is measured by its level of bureaucracy, the stability of its institutions and its ability to maintain public order and provide essential public services to its citizens. From this perspective, a strong state is one that can maintain stability, order and provide basic services to its citizens, whether or not it is democratic. Huntington therefore argues that political order must precede modernisation and democratisation. In other words, before attempting to establish a democracy, one must first establish a solid, well-managed state.

The definition given by Clark, Golder and Golder in their 2009 book "Principles of Comparative Politics" focuses on the ability of a state to exercise power through coercion and the threat of force in a given territory: "A state is an entity that uses coercion and the threat of force to rule in a given territory. A failed state is a state like entity that cannot coerce and is unable to successfully control the inhabitants of a given territory."[6] According to them, a state is an entity that uses coercion and the threat of force to rule over a given territory. That is, for a state to be considered as such, it must have the capacity to maintain order, enforce laws and effectively control the population within its borders. This capacity is generally backed up by the use of force, or the threat of force, to deter non-compliance with laws and regulations. In contrast, a "failed state" is a state that cannot exercise coercion and is unable to successfully control the inhabitants of a given territory. A failed state is a state that, for a variety of reasons, can no longer fulfil the basic functions of a state. Such states are often characterised by internal conflict, lack of territorial control, ineffective governance and an inability to provide basic public services to the population.

When a state is unable to apply or enforce its will, this can manifest itself in a number of ways. For example, there may be widespread non-compliance with the law, where citizens do not respect the laws and regulations laid down by the state. This is often the result of a lack of confidence in the legitimacy of the state or its effectiveness in enforcing the law. In addition, there may also be areas of the country where the state does not have effective control, which is often the case in failed or failing states. In these areas, other entities, such as armed groups, militias or criminal organisations, may exercise effective control. Finally, a state may be unable to provide basic public services to its citizens, such as health, education and security. This inability may result from a lack of resources, poor management or corruption.

A state that does not have sufficient means to exercise its constraint, or that does not have the capacity to exercise its authority effectively within its territory, is often referred to as a weak or failing state. The ability to levy taxes is often seen as a fundamental function of the state, as it enables public services to be financed and the machinery of government to function. If a state is unable to levy taxes effectively, this may indicate a lack of authority or control over its territory. It can also mean that the state is having difficulty providing basic services to its citizens, which in turn can erode its legitimacy and stability. In extreme cases, a state's inability to levy taxes can contribute to its collapse or failure, creating a power vacuum that can be exploited by non-state actors, such as armed groups or criminal organisations.

The following countries have faced significant challenges in terms of governance, political instability and conflict, which have undermined the ability of their respective governments to fully exercise their authority and deliver basic services to their citizens. However, it should be noted that the situation can vary considerably from one country to another, and even from one region to another within the same country. Moreover, these countries are working actively, often with the help of the international community, to overcome these challenges and improve their state capacity. Here is a brief description of the situation in each of these countries:

- Afghanistan: Since the withdrawal of US and NATO forces in 2021, the country is once again under Taliban control. The security and political situation remains volatile, and the Taliban government faces enormous challenges in governing the country.

- Somalia: Somalia has been plagued by civil war since the 1990s. However, since 2012, a process of political stabilisation has been underway with the formation of a federal government. However, the country continues to face major security challenges, particularly due to the activities of the militant group Al-Shabaab.

- Haiti: Haiti faced a number of challenges in terms of governance and political stability. The assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021 exacerbated the political crisis in the country. Haiti is also grappling with major economic difficulties and security issues, including kidnapping and banditry.

- Sierra Leone: Sierra Leone experienced a devastating civil war from 1991 to 2002. Since then, the country has made significant progress in reconciliation and reconstruction, but still faces major economic and social difficulties.

- Congo: The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been plagued by conflict and political instability for decades. Although the situation has improved since the end of the Congo war in 2003, the country still faces major challenges in terms of governance, security and development.

- Eritrea: Eritrea is an authoritarian state, and its government has been criticised for human rights violations. The country also faces significant economic challenges.

The Fund for Peace is an independent research and education organisation that works to prevent war and reduce violence. It has created the Fragile States Index (FSI) to assess stability and pressure on states around the world. The index is based on twelve separate indicators that measure different aspects of a state's fragility.

The Fund uses these twelve indicators for Peace to assess state fragility. Here is an explanation of each indicator:

- Demographic pressure: This indicator assesses the potential tensions resulting from demographic factors such as overpopulation, shortages of food and water resources, or lack of adequate infrastructure.

- Emergency humanitarian situation linked to population movements: This measures the scale of humanitarian crises caused by population movements, such as forced population displacement or refugee movements.

- Mobilisation of groups on the basis of grievances (revenge): It examines the extent to which particular groups may mobilise on the basis of real or perceived grievances, thereby threatening the stability of the state.

- Emigration: This measures the degree to which people emigrate from the country, often as a result of precarious political, economic or security conditions.

- Unequal economic development between groups: This indicator assesses the gap in economic development between different groups within the state, which can lead to social and political tensions.

- Poverty, economic decline: This measures the prevalence of poverty and the extent of economic decline, both of which can contribute to state fragility.

- Criminalisation of the state (lack of legitimacy): This indicator assesses the extent to which the state itself is involved in illegal or criminal activities, which can erode its legitimacy in the eyes of the population.

- Progressive deterioration of public services: This looks at how effectively the state is able to provide essential public services to its population, such as education, health and infrastructure.

- Violation of human rights and the rule of law: This indicator measures the extent of violations of human rights and the rule of law committed by the state or with its consent.

- Security apparatus operating as a state within the state: This assesses the extent to which state security forces operate independently of civilian or legal control, acting as a 'state within the state'.

- Division of elites: This indicator measures the degree of division or conflict between different elites within the state, whether political, economic, military or other.

- Intervention by other states or other external agents: This measures the degree of intervention by other states or external actors in the affairs of the state, which may contribute to its fragility.

Each indicator is rated on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 representing the least vulnerability and 10 representing the most vulnerability. Adding up the scores for each indicator gives a total score for each country, which is then used to establish an overall ranking of state fragility. It is important to note that the State Fragility Index is a relative and not an absolute measure of a state's vulnerability. It aims to give a general indication of the situation in a country, but does not claim to provide a complete or accurate picture of the reality on the ground. Moreover, the FSI is subject to criticism and debate among researchers and practitioners in the field of state stability and conflict prevention.

The following four categories defined by the Fund for Peace are used to classify the stability of states on the basis of their total scores on the twelve indicators. Each category represents a different level of stability or vulnerability:

- Alert: This category includes states with the highest scores and which are therefore the most vulnerable. These states present extremely worrying levels of fragility and risk of instability or conflict. They require urgent attention to avoid a major crisis or destabilisation. Examples: Afghanistan, Somalia.

- Warning: States in this category have fairly high scores, indicating a significant level of vulnerability, although not as severe as states on alert. These states often have systemic problems which, if left unresolved, could lead to a crisis. Examples: Iraq, Nigeria.

- Moderate: States in this category have moderate scores, indicating a degree of stability, but also the presence of challenges. They are generally stable, but have problems in certain areas that require attention to avoid further deterioration. Examples: Brazil, India.

- Sustainable: These states have the lowest scores, indicating a high level of stability. They generally have strong and effective institutions, robust economies and high levels of respect for human rights and the rule of law. However, no state is totally immune to challenges, so even states in this category must continue their efforts to maintain stability. Examples: Canada, Norway.

These categories provide a means of quickly assessing a state's level of stability and identifying areas that require attention or intervention.

These 2011 statistics clearly indicate that the majority of states around the world were facing significant stability and governance challenges. With 73% of states classified as being in a state of alert or warning, this underlines the global level of vulnerability and the need for effective measures to prevent instability and crisis. On the other hand, with only 15 out of 127 states (less than 12%) classified as stable and sustainable, it is clear that stable governance models such as democracy and the rule of law are far from being the global norm. These stable states are mainly concentrated in North America and Western Europe, indicating a marked geographical divide in terms of political and institutional stability.

According to Max Weber, in his book The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, the modern state is

In "The Theory of Social and Economic Organization", Max Weber offers a definition of the modern state that emphasises several fundamental elements: "the primary formal characteristics of the modern state are as follows: It possesses an administrative and legal order subject to change by legislation, to which the organized corporate activity of the administrative staff, which is also regulated by legislation, is oriented. This system of order claims binding authority, not only over the members of the state, the citizens, most of whom have obtained membership by birth, but also to a very large extent, over all action taking place in the area of its jurisdiction.It is thus a compulsory association with a territorial basis. Furthermore, today, the use of force is regarded as legitimate only so far as it is either permitted by the state or prescribed by it".[7]

First, the state has an administrative and legal order that legislation can modify. This means that the state has a set of rules and structures governing its operation that acts of legislation can modify. Secondly, the organised activity of administrative staff is also regulated by legislation. This indicates that not only the administrative and legal order, but also the day-to-day functioning of the State administration is regulated by law. Thirdly, the State claims binding authority not only over its citizens, but also over all actions that take place within its territory. This makes the state a compulsory association based on territory. Finally, Weber emphasises that the use of force is considered legitimate only insofar as it is authorised or prescribed by the state. This means that the state has a monopoly on legitimate violence, and that any other use of force is considered illegitimate unless the state expressly authorises it.

The modern state is distinguished by its sovereign authority, which is exercised through legislation and respect for the law. The rules and obligations formulated by the State apply to all those residing within its territory, including the State itself. This means that the State is obliged to comply with its own laws and regulations. This idea is at the heart of the concept of the rule of law, according to which all persons, institutions and entities, including the State itself, are accountable to the law, which is applied fairly and equitably. From this perspective, the state's use of coercion or violence is not arbitrary. On the contrary, it is regulated by laws or constitutional provisions that define the circumstances and procedures for its use. This is why the State has a monopoly on "legitimate violence" - because its use of force is limited and regulated by law. This capacity for self-regulation is fundamental to the legitimacy of the State. Without it, the state risks becoming an oppressive and arbitrary entity, thereby losing its legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens.

The law provides the structural framework within which the state operates. It defines the form of government (e.g. republic, constitutional monarchy, etc.), the way in which power is distributed (e.g. unitary, federal, etc.), and the fundamental principles of political organisation (e.g. democracy, autocracy, etc.). In addition to these aspects, the law also establishes the framework for public administration. It defines the responsibilities of the various government bodies, the procedures to be followed in implementing policies, the rights and obligations of civil servants, etc. In addition, in democracies, the law generally provides for democratic control mechanisms, such as elections, public hearings and other forms of citizen participation, to ensure that public administration remains accountable and transparent. Finally, the law plays a crucial role in establishing the social and economic order within the State. It regulates a multitude of aspects of social and economic life, from the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms to the regulation of markets and the economy. In short, the law is an essential tool through which the State structures and organises its own activity and the lives of its citizens. Without the law, the State could not function effectively or fairly.

The notion of sovereignty[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

We have to go back to the sixteenth century to find the first elaboration of this notion by Jean Bodin, which was later examined in greater detail by Thomas Hobbes.

Jean Bodin (1530-1596) is often considered to be one of the first thinkers to have formulated a clear notion of sovereignty in his work "The Six Books of the Republic" (1576). Bodin defined sovereignty as supreme power over citizens and subjects, irresponsible to the latter. For Bodin, sovereignty was a necessary characteristic of the state and was perpetual, indivisible and absolute.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) also made a significant contribution to the idea of sovereignty. In his work Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argues that in order to avoid a state of war between all against all, men enter into a social contract and agree to submit to a sovereign. According to Hobbes, the sovereign, whether a person (as in a monarchy) or a group of people (as in a republic), holds the absolute and indefeasible power to maintain order and peace.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, Europe underwent a period of significant upheaval. This period, often referred to as the "modern age", was marked by wars of religion, particularly in France and Germany, where conflicts between Catholics and Protestants caused major socio-political tensions. The Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in the early 16th century, divided the European continent, leading to political unrest, violent conflict and war. At the same time as these religious wars were taking place, there was political instability due to the emergence of modern sovereign states. Monarchs sought to centralise their power and assert their authority, often through military conflict, in order to strengthen their control over their territories. This process led to the birth of the modern nation state, characterised by distinct territorial sovereignty and centralised authority. The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which devastated much of Europe, is a striking example of this period. It began as a religious war in the Germanic Roman Empire, but developed into a wider political conflict involving several major European powers. The war eventually led to the Peace of Westphalia, which redefined the concept of sovereignty and established the modern idea of independent nation states.

Jean Bodin, a 16th-century French political philosopher, had one major preoccupation: to establish a legitimate and lasting authority at home. In his view, the creation and legitimisation of an internal order was essential to establish justice and guarantee individual freedoms. Bodin used the notion of sovereignty to describe the supreme authority exercised by the prince or monarch over his subjects throughout the kingdom. Later, in the 17th century, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes took up this idea in his major work "Leviathan". For Hobbes, the State was a powerful entity, which he nicknamed "Leviathan", and which held an absolute monopoly on the use of violence. This absolute and unchallengeable authority of the sovereign is necessary to maintain order and peace in society, thus avoiding what he calls the "state of nature", where life would be "solitary, poor, brutish and short". Thus, the notion of sovereignty, as developed by Bodin and Hobbes, refers to the idea of a supreme and absolute power, exercised by the state over a given territory, which is essential to guarantee order, justice and individual freedoms.

For Jean Bodin, sovereign authority is characterised by its absolute and perpetual nature. In his view, sovereignty represents the greatest power of command in a Republic, in other words, the unequalled ability to dictate laws, regulate society and control the use of force. It manifests itself through the exercise of power without restriction or constraint, other than those laid down by natural and divine law. This absolute power is indispensable for maintaining order and peace in society. It is also perpetual, as it cannot be annulled or revoked once it has been established. In other words, the sovereign retains his authority until he voluntarily decides to relinquish it or until he is overthrown by another power.

According to Bodin, the sovereign power is supreme and encompasses all the citizens of the Republic. This power has unlimited authority to create, interpret and apply laws. It is responsible for appointing magistrates and resolving disputes. Consequently, the Prince, as the holder of sovereignty, is considered to be the guardian of the political order. It is under the aegis of sovereignty that the state is able to maintain social and political order, administer justice, protect the rights of citizens and guarantee the well-being of society. Sovereignty is thus the cornerstone of state stability and social peace. It is important to note that this vision of sovereignty as absolute and perpetual power is not without controversy, particularly as regards the limits of sovereign power and respect for citizens' rights and freedoms.

In "Du Contrat Social", Rousseau develops the idea of a "state of nature" as a kind of pre-social and pre-political condition in which humanity would have lived before the advent of society and the state. He differs from Hobbes, however, in his view of this state of nature [8] Whereas for Hobbes the state of nature was characterised by a "war of all against all" where insecurity and fear reigned, for Rousseau the state of nature was a period of innocence, peace and equality. In his view, people were essentially good in the state of nature, but the creation of society, with its inequalities and conflicts, had corrupted this natural goodness. Rousseau proposed the social contract as a solution to this corruption. Individuals agree to submit to the general will, which represents the common good, in exchange for the protection of their rights and freedoms. So, for Rousseau, sovereignty belongs to the people, not to a monarch or an elite. It was this vision of sovereignty that would influence the theories of democracy and the republic.

The notion of sovereignty was first significantly developed by Jean Bodin in the 16th century. In his work "The Six Books of the Republic" (1576), Bodin defined sovereignty as "the absolute and perpetual power of a Republic", which is exercised by the State over its territory and population. According to Bodin, sovereignty is indivisible, inalienable and perpetual. It manifests itself in the power to make laws, declare war and peace, administer justice, control the currency and impose taxes. Internal sovereignty, on the other hand, refers to a state's ability to effectively control its territory and exercise authority over its population. This includes the ability to apply and enforce laws, maintain public order, protect citizens' rights and freedoms, and provide public services. A state with strong internal sovereignty is able to maintain order and stability within its borders, without the need for external intervention.

It is important to note that these two conceptions of sovereignty are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are often interdependent. A state may have sovereignty in Bodin's sense (i.e. the ability to make laws and decisions without external interference), but if it does not have strong internal sovereignty (i.e. the ability to enforce those laws and decisions effectively), its overall sovereignty may be compromised. Conversely, a state that has strong internal sovereignty but is subject to strong external pressure or interference may also find its overall sovereignty weakened.

Stephen D. Krasner, a specialist in international politics, has further explored the notion of sovereignty by proposing four distinct conceptions of sovereignty in his book Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy (1999).[9] These conceptions are:

- Domestic sovereignty: This refers to the organisation of public authority within a state and the state's ability to effectively exercise its authority and control its territory. It is linked to the concept of internal sovereignty mentioned above.

- Interdependent sovereignty: This concerns the ability of states to control cross-border movements of people, goods, ideas, etc. With globalisation, this form of sovereignty has become increasingly problematic, as states often find it difficult to control these cross-border flows.

- Westphalian sovereignty: Named after the Treaties of Westphalia (1648) which ended the Thirty Years' War in Europe, this concept refers to the exclusion of external interference in a state's internal affairs. It is a form of sovereignty that is often invoked in international discourse, although it is often violated in practice.

- Legal international sovereignty: This refers to the formal equality of all states within the international legal framework. In other words, all states, regardless of their size, power or wealth, are formally equal under international law.

These different conceptions of sovereignty highlight the complexity of the notion of sovereignty in contemporary international politics. They show that sovereignty is not simply the ability of a state to exercise power within its borders, but also involves issues of control over cross-border movements, non-interference and formal equality between states.

Legal sovereignty in the international context[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

International legal sovereignty is a central concept in international law. It refers to the mutual recognition of states as legally independent entities within the international community. In other words, it is the acceptance by states of the legitimacy of all other states as autonomous actors on the international stage. This means that each state has the right to govern its own territory without outside interference, and that other states must respect this right. This is what is generally understood when we talk about a state's "sovereignty". States also have the right to participate in international life, for example by signing treaties, joining international organisations or taking part in international negotiations.

However, international legal sovereignty does not necessarily guarantee a state's actual ability to exercise authority or control over its territory (known as "de facto sovereignty"). In many cases, a state may be recognised as legally sovereign but lack effective control over its territory or population. For example, a government may be unable to maintain law and order, provide basic public services or defend its borders against foreign invasion. In such cases, we often speak of "weak states" or "failed states". At the same time, international recognition can sometimes be contested or denied. For example, some territories may declare themselves independent and establish their own government, but not be recognised as sovereign states by the international community. Such territories are often referred to as "unrecognised states" or "de facto states".

International recognition of a state is often the result of bilateral processes. For example, Germany was the first country to recognise the independence of Slovenia and Croatia in November 1991, in the context of the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. This recognition was subsequently followed by that of other countries, leading to the integration of these two new entities into the international community as sovereign states. Bilateral recognition is a way for a state to formally express its acceptance of the sovereignty and independence of another state. It generally involves the establishment of diplomatic relations and can also pave the way for bilateral cooperation agreements in various fields, such as trade, defence or culture.

However, bilateral recognition is not always followed by multilateral recognition. In other words, the fact that a State is recognised by another State does not necessarily mean that it will be recognised by the international community as a whole. For example, some States may choose not to recognise a new State because of political disagreements, territorial disputes or strategic considerations. Furthermore, international recognition of a state does not necessarily imply recognition by international organisations. For example, a state may be recognised by a large number of countries, but not admitted to the United Nations because of the veto of one or more permanent members of the Security Council.

International recognition of a state has profound and practical implications. It can open the door to a multitude of opportunities and advantages, both political and financial. Here are a few examples:

- Access to international organisations: Once recognised, a state can apply for membership of international organisations such as the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, etc. These memberships can provide it with a platform from which it can benefit. These memberships can provide a platform to collaborate with other nations, share concerns and perspectives, and participate in global decision-making.

- Financial and capital flows: International recognition can encourage foreign direct investment, access to international loans, development aid and other forms of financial support. It can also facilitate international trade by paving the way for bilateral and multilateral trade agreements.

- Symbolic status and power for leaders: When a state is recognised internationally, its leaders acquire greater domestic and international legitimacy. They are able to attend international summits, negotiate treaties, and represent their nation on the world stage.

While these benefits are potentially significant, international recognition also brings with it responsibilities. For example, a recognised state is expected to respect the principles of international law, such as respect for human rights, non-aggression and the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

Westphalian Sovereignty: its origins and implications[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Westphalian sovereignty is a concept that originated in the 1648 Treaties of Westphalia, which put an end to the Thirty Years' War in Europe. This concept refers to the idea that each state has absolute and indisputable authority over its territory and population, and that no other state can interfere in its internal affairs. According to this concept of sovereignty, each state is independent and equal to others on the international stage, regardless of its size or economic or military power. It is this notion that has largely structured the modern international system. It is important to note, however, that Westphalian sovereignty has been modified and challenged several times over the centuries. From humanitarian interventions to international organisations and global norms on issues such as human rights and the environment, various forces have sought to modulate, restrict or transform Westphalian sovereignty.

The concept of Westphalian sovereignty emphasises the territorial independence and exclusive authority of the state over its territory, rejecting any external interference in the internal affairs of the state. This is a fundamental principle of international law, as clearly stated in the United Nations Charter. Article 2 of the UN Charter, in particular, affirms the sovereign equality of all its member states. This principle means that all States, regardless of their size, wealth or military power, have the same rights and obligations under international law. In addition, the UN Charter also enshrines the principle of non-interference, whereby no state has the right to intervene in the internal affairs of another state. This prohibition is intended to protect the sovereignty and independence of all States, large or small.

According to the principles of Westphalian sovereignty and the United Nations Charter, all states are equal in terms of sovereignty. This means that, regardless of their size, economic or military power, each state has the same authority and control over its territory, and no state can interfere in the internal affairs of another. Therefore, from the point of view of sovereignty, the United States is no more sovereign than Luxembourg or Malta. Each state has full authority over its own territory and is free to conduct its internal policy as it sees fit, without external interference.

Westphalian sovereignty establishes that each state has the exclusive right to exercise power and authority over its territory and population, without external interference. This implies that states are free to determine their own internal policies, including their political system, economy, laws and regulations, and that no other state has the right to interfere in these affairs. In other words, each state is regarded as an independent and autonomous entity, free to act as it wishes within its borders, as long as it does not violate international law. This concept is a fundamental pillar of today's international order and is enshrined in the United Nations Charter.

The principle of non-interference is directly linked to the Westphalian notion of sovereignty. According to this principle, no state has the right to intervene in the internal affairs of another state. This means that a country's political, economic, social and cultural decisions are its sole responsibility and cannot be subject to interference or meddling by another state. The principle of non-interference is also enshrined in the United Nations Charter. Article 2(7) of the Charter states: "Nothing in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state, or shall require the Members to submit such matters to settlement under the present Charter". However, it should be noted that there are certain exceptions to this principle, notably in cases of serious violations of human rights or international humanitarian law, where the international community may be authorised to intervene to protect the individuals concerned, as stipulated in the "Responsibility to Protect" doctrine adopted by the United Nations in 2005.

Internal sovereignty: power and authority within borders[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Internal sovereignty refers to a state's ability to maintain order and exercise authority within its borders. This notion of sovereignty relates to the effectiveness of the structure of government, the extent of governmental control, the degree of cohesion among elites and citizens, and the ability to administer laws and policies effectively.

This form of sovereignty emphasises the state's authority over its citizens, its ability to maintain security, enforce laws and implement public policies. In this sense, internal sovereignty is closely linked to the concept of the state's monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force, as defined by Max Weber.

A state is considered to be fully internally sovereign when it is able to perform these functions effectively and without hindrance. On the other hand, if a state is unable to control its territory, ensure public order, provide basic services to its citizens or maintain the authority of its government, its internal sovereignty can be said to be limited or compromised. This is often the case with so-called "fragile" or "failed" states.

Interdependent Sovereignty: a new concept in a connected world[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Interdependence sovereignty deals with a state's ability to control and regulate transnational flows that cross its borders. These flows can take a variety of forms, including trade, capital movements, population migrations, the spread of information and ideas, and so on.

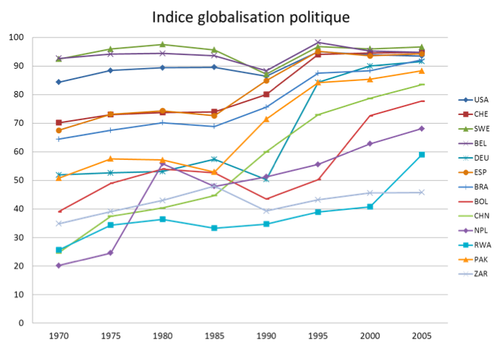

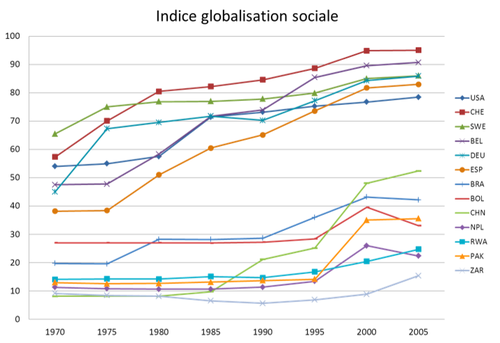

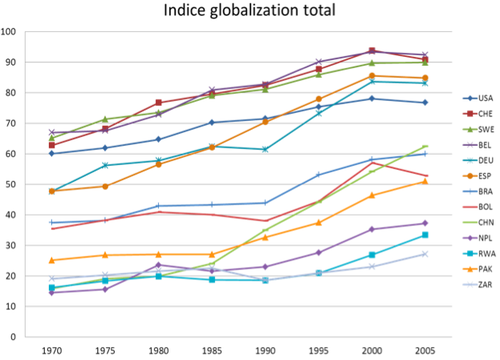

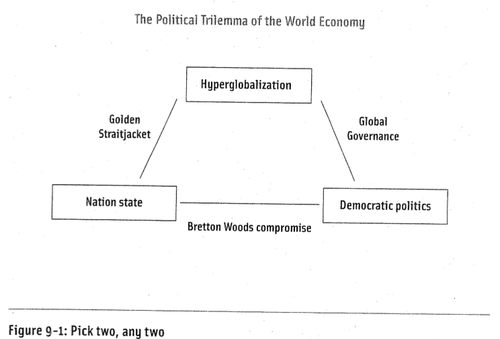

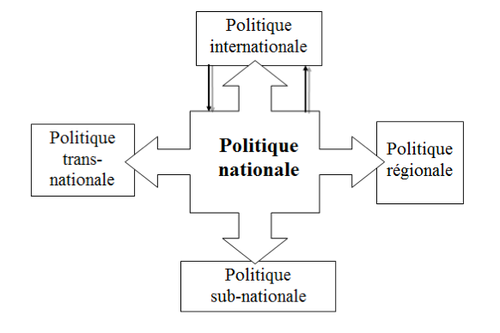

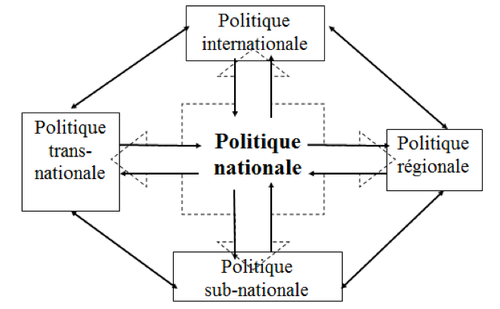

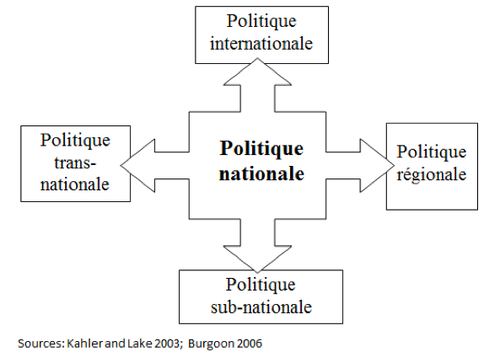

In an increasingly interconnected and globalised world, the notion of interdependent sovereignty has become increasingly important. The intensification of transnational flows can pose significant challenges to a state's sovereignty, insofar as it may limit its ability to control these flows and, consequently, to influence or determine internal outcomes. For example, globalisation has led to growing economic interdependence between states, with increasing international trade and financial flows. However, this has also created challenges for the interdependent sovereignty of states, as they may find themselves unable to control or regulate these flows effectively.