« Externalities and the role of government » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (15 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 11 : | Ligne 11 : | ||

{{hidden | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to microeconomics]] | |[[Introduction to microeconomics]] | ||

|[[Microeconomics Principles and Concept]] ● [[Supply and demand: How markets work]] ● [[Elasticity and its application]] ● [[Supply, demand and government policies]] ● [[Consumer and producer surplus]] ● [[Externalities and the role of government]] ● [[The costs of production]] ● [[Firms in competitive markets]] ● [[Monopoly]] ● [[Oligopoly]] ● [[Monopolisitc competition]] | |[[Microeconomics Principles and Concept]] ● [[Supply and demand: How markets work]] ● [[Elasticity and its application]] ● [[Supply, demand and government policies]] ● [[Consumer and producer surplus]] ● [[Externalities and the role of government]] ● [[Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy]] ● [[The costs of production]] ● [[Firms in competitive markets]] ● [[Monopoly]] ● [[Oligopoly]] ● [[Monopolisitc competition]] | ||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |headerstyle=background:#ffffff | ||

|style=text-align:center; | |style=text-align:center; | ||

| Ligne 24 : | Ligne 24 : | ||

When externalities are present, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently, leading to what is known as "market failure". In such situations, state intervention may be justified to correct these failures. This can be done through regulations, taxes (such as the carbon tax on polluters) or subsidies (to encourage activities that generate positive externalities). | When externalities are present, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently, leading to what is known as "market failure". In such situations, state intervention may be justified to correct these failures. This can be done through regulations, taxes (such as the carbon tax on polluters) or subsidies (to encourage activities that generate positive externalities). | ||

= | = Understanding Externalities and their Impact on Market Efficiency = | ||

==Clarification | == Clarification of Terms: Externalities Explained == | ||

An externality occurs when an action by an individual or a firm has a direct impact on the welfare of a third party without this impact being compensated or regulated by the market price system. This concept is crucial in economics as it represents one of the main market failures. | |||

There are two main types of externalities: | |||

# | # Negative Externalities: These occur when the action of an individual or company has a negative impact on a third party. A classic example is pollution: a company that emits pollutants into the atmosphere affects the health and quality of life of people living nearby, but these costs are not reflected in the price of its products. | ||

# | # Positive Externalities: Conversely, a positive externality occurs when the action of an individual or company benefits others without them paying for the benefit. For example, the planting of trees by an individual may improve the air quality and aesthetics of the neighbourhood, benefiting all the residents of the area without them contributing financially to the planting. | ||

The problem with externalities is that they can lead to a sub-optimal allocation of resources. In the case of negative externalities, they can lead to overproduction or overconsumption of the goods that generate these externalities. Conversely, positive externalities can lead to under-production or under-consumption of the goods that generate them, because producers are not compensated for the benefits they provide to society. | |||

To correct these inefficiencies, state intervention is often necessary. This can take the form of regulations, taxes for negative externalities, or subsidies to encourage activities that generate positive externalities. For example, a carbon tax aims to internalise the environmental costs of pollution, by making polluters pay for the impact of their emissions. | |||

Negative externalities take many forms and have a considerable impact on society and the environment. Take the example of cigarette smoke, often cited for its secondary effects on non-smokers. People exposed to passive smoke suffer increased risks of respiratory and cardiovascular disease, even though they have not chosen to be exposed to these dangers. Another striking example is car exhaust fumes. Air pollution from car traffic affects public health and the environment, even for those who make little or no use of their vehicles. This illustrates how individual transport choices can have widespread and unintended consequences. In urban and residential areas, problems such as dogs barking excessively or leaving faeces on pavements also constitute negative externalities. These behaviours cause inconvenience to residents, ranging from noise nuisance to an increased need for cleaning and maintenance of public spaces. Noise nuisance in general, whether from industry, construction work or leisure activities, is another source of negative externality. It can disrupt daily life, affecting the well-being, sleep and mental health of people living or working nearby. A less obvious but equally important example is antibiotic resistance, exacerbated by the overuse of drugs. Excessive use of antibiotics causes pathogens to adapt, making treatment less effective for the whole population, not just those taking the drugs. Finally, environmental pollution or degradation in various forms - such as the dumping of industrial waste, deforestation or greenhouse gas emissions - has major negative repercussions. These activities damage ecosystems, affect human and animal health, and contribute to climate change, with effects often felt far beyond the immediate areas of impact. These examples highlight the need for government intervention to regulate activities that generate negative externalities. Solutions can include regulations, taxes to discourage harmful behaviour, or awareness campaigns to inform the public of the consequences of certain actions. By proactively addressing these issues, societies can better manage the unwanted side-effects of certain activities and promote a healthier, more sustainable environment for all. | |||

Positive externalities, where the actions of one person or company benefit others without direct compensation, play a crucial role in the economy and society. Take, for example, the phenomenon of a car being sucked up by a lorry on the motorway. When a lorry is travelling at high speed, it creates a wake of air that can reduce wind resistance for the following vehicles, thereby improving their fuel efficiency. Although this is not the truck driver's main intention, it benefits other drivers by reducing their fuel consumption. Vaccines are a classic example of a positive externality. When people are vaccinated, they not only protect themselves against certain diseases, but also reduce the likelihood of these diseases being transmitted to others. This herd immunity benefits the whole community, especially those who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons. The restoration of historic buildings or any activity that attracts tourists also brings significant benefits to the local community. These projects not only increase the aesthetic appeal of an area, but also stimulate the local economy by attracting visitors who spend money in hotels, restaurants and other local businesses. Another fascinating example is the interaction between an orchard and the hives of a neighbouring beekeeper. The beekeeper benefits from the presence of the orchard, as his bees find an abundant source of nectar, improving the quality and quantity of their honey. In return, the orchards benefit from pollination by the bees, which is essential for fruit production. It's a fine example of symbiosis where both parties mutually benefit from their respective activities. Finally, research into new technologies is often a source of positive externalities. Innovations and discoveries can benefit society as a whole by improving quality of life, introducing new solutions to existing problems and stimulating economic growth. Often, the benefits of such research far outweigh the direct spin-offs for the researchers or the organisations that fund them. These examples illustrate the importance of positive externalities in our society. They also highlight the role that government intervention, for example by subsidising or supporting activities that generate such externalities, can play in maximising collective well-being. | |||

== | == The Consequences of Externalities on the Market Economy == | ||

Externalities, whether positive or negative, create a mismatch between private costs and benefits and social costs and benefits, leading to market inefficiencies. | |||

In the case of negative externalities, the external costs of production or consumption are not taken into account by producers or consumers. For example, a factory that pollutes does not pay for the environmental and health damage that its pollution causes. This leads to an overproduction of polluting goods, because the market price does not reflect the true social cost of these products. In other words, if external costs were internalised in the price of the product, the cost would be higher, reducing demand and bringing production into line with a more socially optimal level. | |||

For positive externalities, the scenario is reversed. The benefits that the actions of an individual or a company bring to society are not financially compensated. Take the example of vaccination: individuals who are vaccinated not only protect themselves, but also reduce the risk of spreading disease within the community. However, this external benefit is not reflected in the price of the vaccine. As a result, fewer people choose to be vaccinated than would be ideal from a social point of view. If the external benefits were taken into account, vaccination would be more attractive, and the level of vaccination in society could move closer to the social optimum. | |||

Left to their own devices, markets tend to produce an excessive quantity of goods or services generating negative externalities and an insufficient quantity of those generating positive externalities. To correct these inefficiencies, interventions such as taxes (for negative externalities) or subsidies (for positive externalities) are often necessary to align private costs and benefits with social costs and benefits. | |||

The example of the aluminium market is a perfect illustration of how negative externalities can affect the total social cost of production. In this case, the pollution generated by aluminium plants represents an external cost that is not initially taken into account when calculating the cost of producing aluminium. The private cost of production is the cost that the aluminium producer must bear directly to manufacture the product. This cost includes items such as raw materials, labour, energy, equipment maintenance and other operating expenses. These are the costs on which the company bases its selling price and profitability. | |||

However, if aluminium plants pollute, there are external costs that affect other parts of society. These external costs can include adverse effects on public health, damage to the environment, reduced quality of life, and other negative impacts that are not reflected in the price of aluminium. For example, pollution can lead to additional health costs for the community, environmental clean-up and restoration costs, and a loss of biodiversity. The social cost of aluminium production is therefore the sum of the private cost of production (the cost borne by producers) and the external cost (the costs incurred by society as a result of pollution). This addition shows that the market price of aluminium, based solely on the private cost, is lower than the true social cost of its production. | |||

This discrepancy leads to an overproduction of aluminium compared to what would be produced if external costs were included, which is a typical example of market inefficiency due to negative externalities. To correct this, measures such as imposing an environmental tax on the pollution produced by aluminium plants could be introduced. This tax would aim to internalise external costs, thereby aligning the private cost with the social cost and leading to production that is closer to the social optimum. | |||

Social cost = private cost of production (supply) + external cost | |||

Here's a closer look at this equation: | |||

* | * Private Cost of Production: These are the costs that the aluminium producer has to bear to make the product. This includes expenditure on raw materials, labour, energy, equipment and other operational costs. These costs determine the price at which the company is willing to offer its product on the market. | ||

* | * External cost: These are the costs incurred by the company that are not taken into account by the producer. In the case of aluminium, if production involves pollution, external costs may include impacts on public health, the environment, quality of life and other aspects that are not reflected in the market price of aluminium. These costs are often diffuse and difficult to quantify precisely, but they are real and significant. | ||

* | * Social cost: The social cost is the sum of the private cost of production and the external cost. It represents the total cost to society of aluminium production. This social cost is higher than the private cost of production due to the addition of external costs. | ||

When social costs are not factored into production and consumption decisions, this leads to overproduction of aluminium compared with what would be socially optimal. In other words, more aluminium is produced than would be the case if the costs of pollution were taken into account. This situation is a classic example of market failure due to negative externalities. To remedy this, public policies can intervene, for example by imposing pollution taxes so that producers internalise these external costs, or by imposing environmental regulations to limit pollution. The aim of these interventions is to ensure that the private cost more closely reflects the social cost, leading to a more efficient allocation of resources from society's point of view. | |||

== | == Pollution and Social Optimum Analysis == | ||

In an economic framework, the intersection of the demand and social cost curves is crucial to understanding how to achieve an efficient equilibrium that takes account of both private interests and social impacts. | |||

Here's how it works: | |||

# Demand curve: The demand curve reflects the willingness of consumers to pay for different quantities of a good or service. It shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded, usually with an inverse relationship: as the price rises, the quantity demanded falls, and vice versa. # Social Cost Curve: The social cost curve encompasses both the private cost of production (the direct costs incurred by the producer) and the external costs (the uncompensated costs incurred by society as a result of producing the good). For example, in the case of aluminium, this would include the costs of production plus the environmental and public health costs associated with pollution. # Intersection for Optimal Quantity: When the demand curve intersects the social cost curve, this indicates the optimal quantity of the good from the point of view of society as a whole. At this point, the price that consumers are prepared to pay corresponds to the total cost (private + external) of producing the good. This quantity is different from the one that would be reached if only the private cost were taken into account, because it incorporates the total impact on society. | |||

If markets only take private costs into account, there will be a tendency for overproduction (in the case of negative externalities) or underproduction (in the case of positive externalities) in relation to this optimal quantity. This is why interventions such as taxes (to internalise external costs) or subsidies (to encourage the production of goods generating positive externalities) may be necessary to align market quantities with socially optimal quantities. | |||

This approach aims to achieve an equilibrium where production and consumption choices reflect not only private costs and benefits, but also the costs and benefits to society as a whole. | |||

The distinction between the market equilibrium quantity and the socially optimal quantity is a key point in economics, particularly when considering the impact of externalities. | |||

# Market Equilibrium Quantity: In a free market without external intervention, equilibrium occurs at the point where the private cost of production (the cost to the producer) equals the private profit (the price consumers are willing to pay). At this equilibrium point, the quantity of goods produced and the quantity demanded by consumers are equal. However, this equilibrium does not take into account the external costs or benefits that affect society as a whole. | |||

# Socially Optimal Quantity: The socially optimal quantity, on the other hand, occurs at a level of production where the social cost (which includes private costs and external costs) is equal to the social benefit (which includes private benefits and external benefits). This quantity takes into account the total impact on society, not just on direct producers and consumers. | |||

In the case of negative externalities, such as pollution, the social cost of production is higher than the private cost. As a result, the socially optimal quantity is generally lower than the market equilibrium quantity. This means that reducing production to the socially optimal quantity would reduce external costs (such as environmental damage) and would therefore be more beneficial for society as a whole. To achieve this socially optimal quantity, policy interventions such as pollution taxes (to internalise external costs) or regulations (to limit the quantity produced) may be necessary. These interventions aim to align private interests with social interests, ensuring that the costs and benefits to society are taken into account in production and consumption decisions. | |||

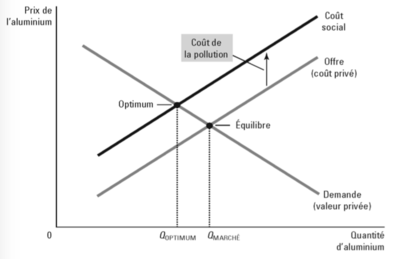

[[Fichier:Pollution et optimum social 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

This graph represents a classic economic graph illustrating the concepts of market equilibrium and social optimum in the context of aluminium production and its negative externalities, in particular pollution. | |||

On the horizontal axis, we have the quantity of aluminium produced, and on the vertical axis, the price of aluminium. Three curves are drawn: | |||

# The demand curve (private value): This shows the relationship between the price consumers are prepared to pay and the quantity demanded. It is decreasing, which means that the lower the price, the higher the quantity demanded, and vice versa. # The supply curve (private cost): This represents the cost to producers of producing aluminium. It rises, indicating that the greater the quantity produced, the higher the cost of production (and therefore the selling price). | |||

# The social cost curve: This curve is above the supply curve and represents the total cost of aluminium production, including the cost of pollution. The social cost is higher than the private cost because it takes into account the negative external effects of pollution on society. | |||

The point where the demand curve crosses the supply curve (private cost) is the market equilibrium point (QMARCHEˊ). This is where the market, in the absence of regulation, tends to stabilise: the quantity that producers are prepared to supply at the market price equals the quantity that consumers are prepared to buy. | |||

However, this equilibrium point does not take into account the cost of pollution. If we include the cost of pollution, we obtain the social cost curve, which intersects the demand curve at a different point, marked "Optimum". This social optimum point (QOPTIMUM) represents the quantity of production that would be ideal if external costs were taken into account. At this quantity, the total cost to society (including the cost of pollution) is equal to the price that consumers are prepared to pay. | |||

What is notable about this graph is the difference between Q MARKET and Q OPTIMUM. The quantity produced at the market equilibrium point is higher than the socially optimal quantity, which implies that the market itself produces more aluminium than would be socially desirable because of external costs not taken into account (pollution). To reduce aluminium production from Q MARKET to Q OPTIMUM, political interventions such as pollution taxation, the introduction of quotas or environmental regulations may be necessary. In short, this graph clearly illustrates the implications of negative externalities on market efficiency and highlights the importance of regulatory intervention to achieve a level of production that is in harmony with social interests. | |||

==Impact of Negative Externalities on Society== | |||

A negative externality is a cost incurred by a third party who is not directly involved in an economic transaction. This means that part of the production costs are not borne by the producer or consumer of the good or service in question, but by other members of society. Negative externalities tend to reduce overall well-being, because the social costs of these economic activities are higher than the private costs. | |||

Let's take a concrete example: a factory that produces aluminium emits pollutants into the atmosphere. These emissions have consequences for public health, such as respiratory illnesses, and for the environment, such as damage to the ecosystem. These additional costs to society, which can include increased medical costs and loss of biodiversity, are not reflected in the price of aluminium. If the plant does not pay for these external costs, it has little incentive to reduce pollution and may even produce aluminium at an artificially low cost, leading to overproduction and overconsumption of the metal. | |||

From a welfare perspective, this creates a problem. Members of society suffer damage that they did not choose and for which they are not compensated. As a result, overall well-being is lower than it could be if these external costs were taken into account. | |||

Economic theory and public policy seek to resolve this problem of negative externality through various interventions: | |||

* Taxation of polluting activities: Taxes can be imposed on pollution to encourage companies to reduce their emissions. These taxes aim to internalise the external cost, which means that the producer will have to take the cost of pollution into account in its production decisions. | |||

* Environmental regulations and standards: Laws can be put in place to directly limit the amount of pollution that a company can emit, thus forcing companies to adopt cleaner technologies or change their production processes. | |||

* Emissions trading markets: In some cases, it is possible to create markets where companies can buy and sell rights to pollute, thereby achieving pollution reductions at the lowest cost. | |||

These measures aim to reduce negative externalities and, as a result, improve society's well-being by ensuring that the social and private costs of production are better aligned. By incorporating the cost of pollution into the price of goods and services, businesses and consumers can make more informed decisions that reflect the true cost of their activities, leading to a more efficient and equitable outcome for society as a whole. | |||

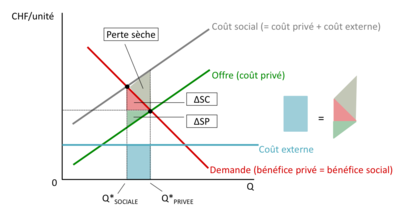

[[Fichier:Externalité et bien être 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

This is an economic graph detailing the effects of negative externalities on well-being in a market, in this case the hypothetical market for a good measured in Swiss francs per unit. The downward sloping demand curve shows the value that consumers place on different quantities of the good, reflecting the private and social benefits associated with its consumption. At the same time, the upward sloping supply curve reflects the private cost incurred by producers in supplying each additional unit of the good. Normally, in a market without externalities, equilibrium would be found at the intersection of these two curves, marking the quantity where private cost equals private benefit. | |||

However, when we take into account external costs, such as pollution or other damage to society not included in the cost of production, a new curve, the social cost curve, is introduced. This curve, positioned above the supply curve, integrates these external costs into the private cost, showing the true cost to society. The intersection of this curve with the demand curve then marks the socially optimal quantity of the good, which is less than the market equilibrium quantity. | |||

The graph highlights an area of deadweight loss, represented by a hatched area between the market equilibrium and socially optimal quantities. This dry loss symbolises the economic welfare lost as a result of production in excess of the social optimum. It is the value of the units produced in excess that society would have preferred not to produce if all the costs, including those of pollution, had been taken into account. This loss is a market inefficiency because it represents a cost to society that is not offset by an equivalent gain elsewhere in the economy. | |||

The blue band at the bottom of the graph shows the external cost, which remains the same for each unit produced, regardless of the number of units. This external cost, constant per unit, is not reflected in the private cost of production and must be taken into account when assessing the total impact on society. | |||

The graph clearly shows that without intervention, a market can operate inefficiently, producing more than is socially desirable because external costs are not taken into account. This leads not only to harmful overproduction but also to a sub-optimal allocation of society's resources. This is why policies such as pollution taxation are often proposed to realign production with the social optimum, thereby reducing deadweight loss and increasing collective well-being. These measures aim to make producers responsible for the costs they impose on society, encouraging production that is more respectful of the environment and more in line with the interests of society as a whole. | |||

==The Impact of Education as a Positive Externality== | |||

In the context of externalities and social well-being, determining the optimal quantity of a good or service to produce and consume takes into account not only private benefits and costs but also external benefits and costs to society. When we talk about social benefit, we are referring to the sum of private benefits, which are the direct benefits for the consumers and producers involved in the transaction, and external benefits, which are the unaccounted benefits that accrue to third parties not directly involved in the economic exchange. | |||

The intersection of the social benefit curve and the cost curve reflects the point at which collective well-being is maximised. At this point, the last unit produced brings as much additional benefit to society as it costs to produce it. This is what we call the socially optimal quantity. This contrasts with the market equilibrium point, which takes account only of private benefits and costs and ignores external effects. | |||

For goods that generate positive externalities, such as vaccination or education, the social benefit curve would be higher than the private benefit curve, suggesting that the socially optimal quantity is greater than what the market would produce on its own. This often justifies incentives or subsidies to increase the production and consumption of these goods to the socially optimal level. | |||

Conversely, for goods that generate negative externalities, such as pollution from industrial production, the social cost curve is higher than the private cost curve. This implies that the quantity produced at market equilibrium exceeds the socially optimal quantity, because producers and consumers do not take external costs into account in their decisions. In this case, interventions such as Pigouvian taxes or regulations are needed to reduce production to a level that reflects the true costs to society. | |||

The point of intersection between social benefit and cost reflects the optimal trade-off between the benefits of goods and services and their cost of production, including externalities. Reaching this point often requires active political action to correct market failures and align private incentives with social objectives. | |||

The socially optimal level of production relative to the market equilibrium quantity depends on the nature of the externality concerned. | |||

For goods with positive externalities, the socially optimal level of production is often higher than the market equilibrium quantity. This is because the social benefits of an additional unit of the good are greater than perceived by consumers and producers. As a result, the market, left to its own devices, does not produce enough of the good to maximise social welfare. Vaccinations are a classic example of this; they benefit society more than they cost to produce, but without intervention, fewer people are vaccinated than would be socially ideal, because individuals do not take into account the benefits that their vaccination brings to others. | |||

For goods with negative externalities, the socially optimal level of production is in fact often lower than the market equilibrium quantity. This is because the social costs of an additional unit of the good (such as pollution) are higher than the producer takes into account. Without regulatory intervention or taxation, producers will produce too much of this good, exceeding the quantity that would be optimal for society. | |||

To sum up | |||

* Market equilibrium quantity: The quantity that producers are willing to sell is equal to the quantity that consumers are willing to buy, without taking externalities into account. | |||

* Socially optimal quantity: The quantity at which the total cost to society (including external costs) is equal to the total benefit to society (including external benefits). For goods with positive externalities, this quantity is higher than the market equilibrium; for those with negative externalities, it is lower. | |||

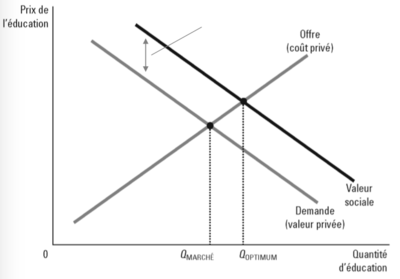

[[Fichier:Education et optimum social 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

The graph represents an economic analysis of education as a good on a market, taking into account the effects of positive externalities. The supply curve, which rises, shows that providing more education costs educational institutions more, incorporating elements such as teachers' salaries, infrastructure and teaching resources. On the other hand, the falling demand curve shows that the quantity of education that individuals are prepared to consume decreases as the price rises, which is typical of most goods and services. | |||

Where these two curves cross, we find the equilibrium quantity of the market, which is the point where the quantity of education offered corresponds to the quantity that consumers are prepared to buy. However, this equilibrium quantity does not necessarily reflect the optimal level for society as a whole due to the presence of positive externalities associated with education, such as better informed citizens, increased productivity and public health benefits that extend beyond the educated individual. | |||

The socially optimal quantity of education is therefore assumed to be higher than the market equilibrium quantity, reflecting the full social benefit of education, which exceeds the private benefits perceived by individuals. These external benefits are not taken into account by consumers or providers when they make their decisions based solely on private costs and benefits, resulting in a sub-optimal investment in education from society's point of view. | |||

The graph suggests that intervention, such as public policies providing subsidies or funding for education, may be required to increase the quantity of education from the market equilibrium quantity to the socially optimal quantity. These interventions are designed to reduce the cost of education to consumers or to increase supply through direct investment in educational institutions, thereby allowing society to fully realise the benefits of education that would otherwise be lost due to market failures. In sum, the graph highlights the crucial role that government intervention can play in supporting education to achieve a resource allocation that maximises social welfare. | |||

==Benefits of Positive Externalities on General Welfare== | |||

A positive externality occurs when an economic activity provides benefits to third parties who are not involved in the transaction. These third parties enjoy positive effects without having to pay for these benefits, leading to a situation where the total value of these activities for society is greater than the private value for the individuals or companies directly involved. | |||

In the context of welfare, positive externalities are important because they can lead to under-production of the good or service in question if the market is left to its own devices. Producers do not receive payment for the external benefits they provide, so they have no incentive to produce the socially optimal quantity of that good or service. | |||

Take education as an example: it benefits not only the student who acquires skills and knowledge, but also society as a whole. A better educated population can lead to a more skilled workforce, greater innovation, better governance and lower crime rates. These benefits are not reflected in the price of education and, as a result, without intervention, fewer resources will be allocated to education than would be ideal for society. | |||

To address this mismatch, governments can intervene in a number of ways: | |||

* Direct subsidies: Lowering the cost of education for students or institutions can encourage greater consumption or supply of educational services. | |||

* Tax credits: Offering tax benefits for education costs can also encourage individuals to invest more in their education. | |||

* Public provision: The government can provide education directly, ensuring that the quantity produced is closer to the optimal quantity for society. | |||

When the positive externalities are properly internalised by these interventions, society's well-being improves. Individuals benefit from higher levels of consumption of the good or service, and society as a whole benefits from the positive effects that spread beyond the immediate consumers and producers. This leads to a more efficient allocation of resources and an improvement in overall social well-being. | |||

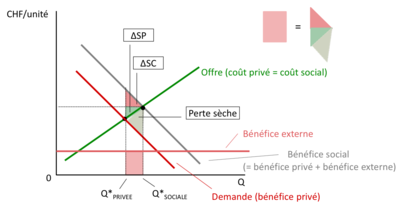

[[Fichier:Externalité positive et bien être 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

This graph represents an economic situation where a positive externality is present on the market. In this case, the social cost of production is equal to the private cost, which indicates that external costs are not significant or that negative externalities are not the focus here. On the other hand, the social benefit curve, which is the sum of private benefits and external benefits, is above the private benefit curve, indicating that the production or consumption of the good or service concerned has additional benefits for society that are not captured by the market. | |||

The demand curve, representing the private benefit, shows the price that consumers are prepared to pay for each quantity of good or service. The social benefit curve, which is above, shows the true benefit to society, including external benefits not paid for by individuals. This could include, for example, benefits such as better public health due to increased vaccination or higher economic productivity due to a better educated population. | |||

The market equilibrium quantity, QPRIVEˊE∗, is the point where the demand curve (private benefit) intersects supply. It is the level of output that the market would achieve without intervention. However, the socially optimal quantity, QSOCIALE∗, is higher because it takes into account external benefits. The market, by itself, does not produce enough to reach this point because producers are not compensated for the external benefits they generate. | |||

The area of deadweight loss, indicated by the hatched area, represents the welfare that society misses out on because the good or service is not produced in the socially optimal quantity. This is market inefficiency, because if production were increased to Q∗SOCIAL, the additional social benefit (the area under the social benefit curve between Q∗PRIVEE and Q∗SOCIAL) would be greater than the additional cost of production (the area under the supply curve between Q∗PRIVEE∗ and Q∗SOCIAL). | |||

The graph suggests that an intervention, such as subsidies or public provision of the good or service, might be required to increase production from Q∗PRIVEE to Q∗SOCIALE, thereby eliminating the deadweight loss. This would allow society to reap the full social benefits of the good or service, improving overall welfare. | |||

== Methods for Internalising Externalities == | |||

The internalisation of externalities is a central concept in economic theory which aims to resolve market inefficiencies caused by the external effects of economic activities. When externalities are present, whether positive or negative, the costs or benefits are not fully reflected in the market. The individuals or companies that generate these externalities do not incur the costs or receive the benefits associated with their actions, which leads them to make decisions that are not socially optimal. | |||

To internalise a negative externality, we could impose a tax that reflects the external cost (such as a carbon tax on polluters), so that the private cost of the activity now includes the external cost. As a result, producers and consumers would have an incentive to reduce production or consumption of the good to a level closer to the social optimum. | |||

Conversely, to internalise a positive externality, the state could offer subsidies or tax credits that increase private profits so that they better reflect social benefits. This would encourage greater production or consumption of the good, as in the case of vaccinations or education. | |||

The private solution to internalising externalities, often associated with the Coase theorem, states that if property rights are well defined and transaction costs are low, the parties involved can negotiate a solution without outside intervention. For example, if a company pollutes a river and harms fishermen downstream, the fishermen could potentially pay the company to reduce the pollution or the company could pay for the damage caused. In theory, as long as the parties can negotiate and their rights are clearly established, they can reach a solution that internalises the externality and achieves efficiency. | |||

However, in practice, the conditions required for a private solution are often difficult to achieve. Property rights may be poorly defined or difficult to enforce, and transaction costs, particularly in terms of negotiation and information, may be prohibitive. Moreover, when many agents are affected, as is often the case with environmental pollution, coordination between all the agents becomes virtually impossible without some kind of collective intervention. Internalising externalities through modified incentives is crucial to achieving an allocation of resources that is not only efficient from a market perspective but also beneficial to society as a whole. Well-designed policies can help achieve this balance, leading to increased social welfare. | |||

In the context of both negative and positive externalities, the state plays a crucial role in putting policies in place to correct market failures and to align market outcomes with social welfare. | |||

For negative externalities, where the activities of companies or individuals have harmful effects on third parties, the state can intervene in several ways: | |||

# Behavioural standards: The state can establish regulations that directly limit harmful activities. These standards can include restrictions on the amount of pollution a plant can emit or requirements for the use of clean technologies. | |||

# Pigouvian taxes: Named after the economist Arthur Pigou, these taxes aim to internalise the cost of negative externalities by including them in the cost of production. The tax is set equal to the cost of the externality for each unit produced, thus encouraging producers to reduce production or find less harmful means of production. In theory, the Pigouvian tax should be equal to the marginal external cost of the socially optimal quantity. | |||

For positive externalities, where the actions of individuals or companies benefit society, the state can also adopt various measures: | |||

# Obligations and Recommendations : Policies can be put in place to encourage behaviour that produces positive externalities. For example, public health campaigns to encourage vaccination or education to promote practices that benefit society. | |||

# Subsidies: By subsidising the production of a good that generates positive externalities, the state can reduce the cost to producers and encourage them to increase production. This can include, for example, subsidies for renewable energy or for research and development in areas of public interest. | |||

# Property rights: Granting property rights or patents on innovations can encourage the creation and dissemination of beneficial technologies or ideas. This allows innovators to benefit directly from their inventions, which might otherwise be under-produced due to the non-excludable nature of their benefits. | |||

These policies aim to align private incentives with social benefits or costs, so that economic activities more accurately reflect their true cost or value to society. By carefully adjusting these interventions, the state aims to achieve an allocation of resources that maximises social well-being. | |||

= Private Approaches to Managing Externalities = | |||

== The Coase Theorem == | |||

The Coase Theorem, formulated by the economist Ronald Coase, offers an interesting perspective on how externalities can be managed by the market without government intervention. According to this theorem, if property rights are clearly defined and transaction costs are negligible, the parties affected by the externality can negotiate with each other to reach an efficient solution that maximises total welfare, regardless of the initial distribution of rights. In this context, property rights are the legal rights to own, use and exchange a resource. A clear definition of these rights is essential because it determines who is responsible for the externality and who has the right to negotiate about it. For example, if a property right is granted to a polluter, the parties affected by the pollution (such as local residents) should theoretically negotiate with the polluter and potentially compensate him for reducing the pollution. Conversely, if local residents have the right to enjoy a clean environment, the polluter should compensate them for continuing to pollute. | |||

Coase's theorem also indicates that the efficient allocation of resources will be achieved whatever the distribution of property rights, as long as the parties can negotiate freely. This means that the parties will continue to negotiate until the cost of the externality to the polluter is equal to the cost to society. The essence of this proposition is that the end result (in terms of efficiency) should be the same regardless of who initially holds the rights, a principle known as Coase invariance. However, in practice, the conditions required for the application of Coase's theorem are often not met. Transaction costs may be significant, property rights may be difficult to establish or enforce, and the parties may not have complete or symmetrical information to negotiate effectively. Furthermore, when many parties are involved or the effects of an externality are diffuse and not localised, the coordination required to negotiate private agreements becomes extremely complex. | |||

In these situations where the conditions of Coase's theorem are not met, state intervention through regulations, taxes or subsidies may be necessary to achieve an allocation of resources that reflects the social cost or benefit of the externalities. This helps to ensure that externalities are internalised, leading to a solution that is closer to the social optimum. | |||

The problems raised are major challenges when it comes to solving externalities by market means or private solutions, as described in Coase's theorem. | |||

Problem I - High Transaction Costs: Transaction costs include all the costs associated with negotiating and executing an exchange. In the case of externalities, these costs may include the costs of finding information about the affected parties, the costs of negotiating to reach an agreement, the legal costs of formalising the agreement, and the monitoring and enforcement costs of ensuring that the terms of the agreement are respected. When these costs are prohibitive, the parties cannot reach an agreement that would internalise the externality. As a result, the market alone fails to correct the externality, and external intervention, such as by the state, may become necessary to facilitate a more efficient solution. | |||

Problem II - Free-Rider Problem: The free-rider problem is particularly relevant in the case of public goods or when positive externalities are involved, such as environmental protection or vaccination. If a good is non-excludable (it is difficult to prevent someone from benefiting from it) and non-rival (consumption by one person does not prevent consumption by another), individuals may be encouraged not to reveal their true value of the good or service in the hope that others will pay for its provision while themselves enjoying the benefits without contributing to the cost. This leads to under-provision of the good or service as everyone expects someone else to pay for the positive externality, resulting in less than the socially optimal quantity being produced. | |||

These two problems illustrate why markets can often fail to resolve externalities on their own and why government intervention may be necessary. The state can help reduce transaction costs by introducing laws and regulations that facilitate private agreements, and it can overcome the free-rider problem by supplying public goods itself or subsidising their production to encourage provision closer to the social optimum. | |||

== The Power of Private Negotiation and the Definition of Property Rights == | |||

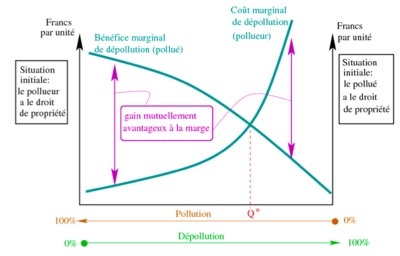

This graph illustrates a negotiation situation between a polluter and a polluted party concerning pollution abatement, in the context of Coase's theorem. The graph shows two curves: the marginal cost of clean-up for the polluter and the marginal benefit of clean-up for the polluted. | |||

[[Fichier:Négociation privée et droits de propriété 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|NB: the socially optimal level of pollution is not zero!]] | |||

This graph illustrates an economic approach to solving the problem of negative externalities by means of negotiations between parties, in accordance with Coase's theorem. It describes a situation where a polluter and a party affected by the pollution, the polluted party, are involved in a negotiation aimed at finding a level of pollution abatement that maximises collective well-being. | |||

In this representation, the cost to the polluter of reducing pollution, or depolluting, increases with each additional unit of depollution undertaken. This is represented by the rising curve, indicating that the first few units of pollution abatement are relatively inexpensive for the polluter, but that the cost increases progressively. At the same time, the benefit to the polluter of reducing pollution decreases with each additional unit. The first reductions in pollution bring great benefits to the polluter, but these benefits diminish as the air or water becomes cleaner. | |||

The point where these two curves cross, marked Q∗, represents the level of pollution abatement where the marginal benefit of cleaning is exactly equal to the marginal cost of cleaning. This is the ideal level of clean-up from the point of view of economic efficiency, as it perfectly balances the marginal cost and benefit of clean-up. | |||

The framework provided by the graph suggests that, regardless of who initially holds the property rights, whether the polluter or the polluted, there is an opportunity for a mutually beneficial agreement. If the polluter has the right to pollute, the polluted can potentially compensate the polluter financially for reducing pollution, to the point where it is no longer advantageous for the polluted to pay for additional pollution abatement. Conversely, if the polluted party holds the right to a clean environment, the polluter could pay for the right to pollute, until the additional cost of reducing pollution outweighs the benefits to the polluter. | |||

However, in reality, negotiations between the polluter and the polluted are often hampered by high transaction costs. These costs can include the legal costs of establishing and enforcing agreements, the costs of information gathering and negotiation, and the challenges of coordinating a large number of parties. In addition, information asymmetries and the free-rider problem, where individuals benefit from bargaining outcomes without actively participating, can also complicate the private resolution of externalities. | |||

As a result, although Coase's theorem offers an elegant solution on paper, the need for state intervention in the form of environmental regulations or taxes is often unavoidable in order to manage externalities effectively and achieve an allocation of resources that reflects the social cost and benefit of depollution. | |||

== Practical Illustration: A Negotiated Agreement in Detail == | |||

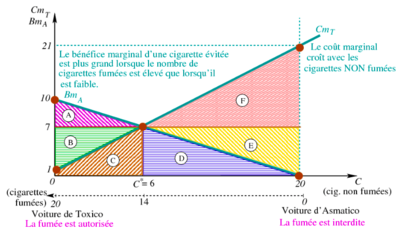

Analysing the marginal costs and benefits for the two brothers, Toxico and Asmatico, gives us a basis for a possible negotiated solution to the issue of smoking in the car on their journeys. | |||

For Toxico, the marginal cost of not smoking a cigarette increases linearly with each cigarette not smoked, which is described by the function <math>Cm_T(C) = 1 + C</math>. This means that each additional cigarette he chooses not to smoke costs him more in terms of personal satisfaction. When he does not smoke in Asmatico's car, the total cost he incurs after giving up a whole pack is 220 welfare units, which is the sum of the marginal costs of each cigarette not smoked. | |||

On the other hand, for Asmatico, who does not like smoking, the marginal benefit of each cigarette not smoked by Toxico decreases with each additional cigarette not smoked. This is represented by the function <math>Bm_A(C) = 10 - \frac{C}{2}</math>. Asmatico's total benefit from abstaining from Toxico is 100 welfare units, which is the sum of the marginal benefits for each cigarette not smoked. | |||

These functions suggest that the two brothers can negotiate compensation that is mutually beneficial. Since the total cost to Toxico of not smoking is higher than the total benefit to Asmatico when Toxico smokes, Asmatico could compensate Toxico for not smoking, up to a point where Toxico's marginal cost equals Asmatico's marginal benefit. The negotiation would consist of determining a quantity of cigarettes that Toxico would be prepared not to smoke and the amount that Asmatico would be prepared to pay for this abstention. | |||

For example, Toxico might agree to reduce the number of cigarettes he smokes if Asmatico pays him a certain amount per cigarette not smoked. They would have to find an agreement that maximises their collective welfare, i.e. find the number of cigarettes that Toxico is prepared not to smoke and that corresponds to the amount that Asmatico is prepared to pay for this reduction. In theory, according to Coase's theorem, they could reach an agreement without the intervention of their parents or any other authority, provided that the transaction costs of negotiating and enforcing this agreement are negligible. | |||

[[Fichier:Externalité Exemple de solution négociée.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Externalité Exemple de solution négociée.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | ||

The graph represents an economic situation involving two parties, Toxico and Asmatico, and their relative preferences for smoking cigarettes while driving. On the horizontal axis we have the number of cigarettes not smoked, C, and on the vertical axis the marginal costs and benefits in terms of well-being or satisfaction, measured in monetary units. | |||

The rising curve, <math>Cm_T</math>, represents the marginal cost to Toxico of not smoking cigarettes. As can be seen, this marginal cost increases with each additional cigarette he chooses not to smoke. This indicates that Toxico finds it increasingly difficult to give up each additional cigarette. | |||

The descending curve, <math>Bm_A</math>, represents the marginal benefit to Asmatico for each cigarette that Toxico does not smoke. The benefit is highest when the number of cigarettes not smoked is low and decreases as more cigarettes are not smoked. | |||

The point where the two curves cross, marked <math>C^* = 6</math>, suggests an optimal trade-off for both parties. At this point, the cost to Toxico of not smoking six cigarettes is equal to the benefit to Asmatico when six cigarettes are not smoked. This implies that Toxico should abstain from smoking exactly six cigarettes for both parties to maximise their combined welfare. | |||

The graph is divided into different coloured areas (A to F), each representing a different cost or benefit to Toxico and Asmatico. For example, areas A and B represent the total cost to Asmatico in Toxico's car when smoking is allowed. Zones C to F represent the total cost to Toxico when he accompanies Asmatico in his car and smoking is prohibited. | |||

The purpose of this illustration is to show how a Coasian negotiation could work between the two parties. If they can negotiate without transaction costs, they could agree to compensate Toxico for smoking only six cigarettes, thereby improving Asmatico's welfare without imposing an excessive cost on Toxico. The negotiation could involve Asmatico paying Toxico for each cigarette not smoked until equilibrium is reached at <math>C^*</math>. | |||

However, if transaction costs were significant or if one party had incomplete information about the other's preferences, reaching this agreement would become more complicated. Furthermore, if Toxico or Asmatico engaged in free-rider behaviour, trying to benefit from the agreement without paying their fair share, this could also prevent an efficient solution from being reached. In the absence of a negotiated solution, external intervention, such as a regulation or policy put in place by the parents or an authority, may be necessary to resolve the situation. | |||

1. PURCHASE OF POLLUTION PERMITS | |||

Toxico decides to buy the right to smoke in Asmatico's car for CHF 7 per cigarette. He continues to smoke until his marginal cost of not smoking reaches CHF 7. At this point, he has given up smoking 6 cigarettes, thus smoking 14 cigarettes out of his usual 20. | |||

The total cost to Toxico is made up of two parts: | |||

#The cost of buying the right to smoke, which corresponds to area D+E in the graph. This is calculated as the price per cigarette multiplied by the number of cigarettes smoked, i.e. <math>7 \times 14 = 98</math> CHF. | |||

#The cost associated with abstaining from the 6 cigarettes he decided not to smoke, corresponding to area C. This cost is represented by the area of a triangle with a base of 6 (the number of cigarettes not smoked) and a height of 7 (the marginal cost of the sixth cigarette not smoked, which starts at CHF 1 for the first cigarette not smoked and increases by CHF 1 for each additional cigarette). Therefore, the area of this triangle is <math>\frac{1}{2} \times 6 \times 7 = 21</math> CHF. The total cost to Toxico is therefore CHF 98 for buying the rights to smoke plus CHF 21 for the cost of abstinence, making a total of CHF 119. However, if he hadn't bought the rights to smoke, smoking all the cigarettes would have cost him CHF 220. So, by not smoking those 6 cigarettes, he makes a gain of <math>220 - 119 = 101</math> CHF, which corresponds to area F. | |||

Asmatico, on the other hand, is prepared to accept this arrangement because up to the thirteenth cigarette, his marginal benefit from not suffering the smoke is less than CHF 7, which is less than he receives from Toxico. He suffers a cost associated with the passive smoke from the 14 cigarettes that Toxico smokes, which corresponds to surface D, valued at CHF 49. However, he earns CHF 98 from Toxico for the right to smoke. So his net gain is <math>98 - 49 = 49</math> CHF, corresponding to surface E. | |||

This example demonstrates how a Coasian negotiation can lead to a solution where both parties improve through voluntary exchanges, despite the presence of negative externalities. | |||

2. PURCHASE OF CLEAN AIR RIGHTS | |||

When Asmatico buys the right to clean air by paying Toxico not to smoke in the car, the calculations show the following results: | |||

Toxico | * The total benefit to Asmatico, if Toxico did not smoke at all during the trip, would be CHF 100. | ||

* The cost to Toxico of not smoking 6 cigarettes is CHF 24, which is the sum of the marginal costs of abstaining from smoking those cigarettes. | |||

* Asmatico pays Toxico CHF 42 to refrain from smoking those 6 cigarettes (CHF 7 per cigarette not smoked). | |||

In terms of net gain for each of the brothers in this scenario: | |||

* Toxico receives CHF 42 from Asmatico, and since his abstinence cost is CHF 24, his net gain is CHF 18. | |||

* Asmatico, on the other hand, pays CHF 42 but his total smoke-free benefit is CHF 100, so his net gain is CHF 58. | |||

In this situation, the quantity of cigarettes not smoked is identical to that in the first scenario: Toxico refrains from smoking 6 cigarettes. However, the net gains differ because of the direction of payment. Asmatico pays for clean air, and Toxico receives compensation for not smoking, unlike in the first scenario where Toxico paid for the right to smoke. | |||

This illustrates how the initial distribution of rights affects the distribution of monetary gains between the parties, even if the quantity of the externality (in this case, cigarette smoke) remains the same. This is a practical demonstration of Coase's theorem: as long as transaction costs are negligible and property rights are clearly defined, parties can negotiate compensation to achieve an efficient outcome regardless of the initial distribution of rights. | |||

=Public Action on Externalities= | |||

==The Range of Public Interventions for Externalities== | |||

When the market leads to a misallocation of resources because of an externality and private negotiation is not possible, usually because of high transaction costs, asymmetric information or the free rider problem, the government can intervene to correct this failure. | |||

One approach the government can take is to adopt authoritarian policies, which consist of strict regulations. These regulations can be in the form of obligations or bans on certain behaviours. For example, the government can make vaccination compulsory for all schoolchildren to ensure that society benefits from herd immunity. Similarly, it can set a maximum level of pollution that companies must not exceed to protect public health and the environment. These measures can be effective in achieving a desired result quickly and fairly directly. | |||

However, these policies can also be seen as intrusive and limit individual freedoms or business choices. They must therefore be carefully designed to balance social welfare objectives with respect for individual rights. Moreover, their effectiveness depends on the government's ability to enforce them, which often requires significant monitoring and resources. | |||

When private negotiations fail to resolve externalities and the market fails to achieve an optimal allocation of resources, government may opt for interventions that rely on market mechanisms to realign private incentives with social interests. These so-called 'market-oriented' interventions seek to use prices and economic incentives to encourage desirable behaviour without directly imposing regulations. | |||

Pigouvian taxes are a classic example of such a policy. Named after the economist Arthur Pigou, they are designed to internalise the costs of negative externalities. By taxing activities that produce harmful externalities, such as pollution, the government can encourage businesses and consumers to reduce their polluting behaviour until the social and private costs are aligned. The amount of the tax is generally set to be equal to the marginal external cost of the polluting activity at the socially optimal quantity. | |||

On the other hand, subsidies can be used to encourage behaviour that has positive externalities. For example, the government can offer financial assistance for insulation improvements in private homes, which reduce energy consumption and, consequently, greenhouse gas emissions. Similarly, subsidies could be offered to companies that invest in the research and development of clean technologies or in the training of their workforce, which can have positive spin-offs for the economy as a whole. | |||

These market-oriented policies are often preferred to direct regulation because they can achieve the desired objectives while allowing flexibility in how individuals and companies respond to fiscal incentives. However, their design and implementation require a precise understanding of the nature and size of externalities, as well as the ability to adjust taxes and subsidies appropriately to avoid undesirable side effects or market distortions. | |||

==Comparison of Permit and Tax Systems== | |||

The State has two main approaches for reducing pollution from a plant: | |||

# Regulation: The state can impose strict regulations that require the plant to reduce pollution to a specific level. These regulatory limits are often defined following environmental and health studies and may include ceilings on emissions of specific pollutants. The plant must then adjust its production processes, invest in pollution control technologies or change its raw materials to comply with the imposed standards. This "command and control" approach provides the authorities with an assurance that certain pollution reductions will be achieved, but can be costly for companies and does not provide flexibility as to how these reductions are achieved. | |||

# Pigouvian tax: Alternatively, the state can impose a Pigouvian tax, which is a tax on each unit of pollution emitted. The amount of the tax is ideally equal to the marginal external cost of pollution at the optimal quantity of pollution. This tax gives the plant an incentive to reduce pollution, because it now has to pay for the external impact of its emissions. The Pigouvian tax offers flexibility to the plant on how to reduce pollution, as it can choose to pay the tax, reduce pollution to avoid the tax, or a combination of both. It can also encourage innovation in pollution abatement technologies, as reducing emissions becomes financially advantageous. | |||

Each of these approaches has its advantages and disadvantages. Regulation can be more direct and easier for the public to understand, but it can also be less efficient and less flexible. Pigouvian taxes, on the other hand, are generally considered to be more efficient from an economic point of view, as they allow each plant to find the most cost-effective way of reducing its pollution. However, determining the exact amount of tax to match the marginal external cost of pollution can be complex and subject to political and economic debate. | |||

The cap-and-trade system, also known as the pollution permit market, is a market-oriented method of controlling pollution by providing economic incentives to reduce polluting emissions. Here's how it works: | |||

# Capping: The State sets a cap, i.e. a maximum limit on the total amount of pollution that can be emitted by all the companies concerned. This cap is lower than the current level of emissions to force an overall reduction. | |||

# Distribution of permits: The state allocates or sells pollution permits to companies, where each permit authorises the holder to emit a certain amount of pollution. The total number of permits corresponds to the emissions cap set by the State. | |||

# Trading: Companies that can reduce their emissions at a lower cost than the market price of permits will have an incentive to do so and will be able to sell their surplus permits. This creates a market for rights to pollute. Companies that find it more expensive to reduce emissions can buy additional permits on the market to comply with the regulations. | |||

The cap-and-trade system has several advantages. It gives companies the flexibility to meet emission reduction targets in the most cost-effective way. It also encourages innovation in clean technologies because the savings from more efficient reductions can be profitable. | |||

However, there is a potential problem with this system linked to lobbying. Companies and interest groups can lobby to increase the number of permits allocated, which would raise the cap on emissions allowed and reduce the effectiveness of the scheme in terms of reducing pollution. If the cap is set too high, permits may become too plentiful and cheap, reducing the incentive to invest in pollution reduction. | |||

For the cap-and-trade system to work effectively, it is crucial that the emissions cap is set at a level that reflects genuine pollution reduction objectives and that it is gradually lowered over time to encourage continued reductions. In addition, the permit allocation process must be transparent and fair to prevent market manipulation and ensure fair and effective competition. | |||

== Pigouvian Taxes and Pollution Permits: An Assessment of their Equivalence == | |||

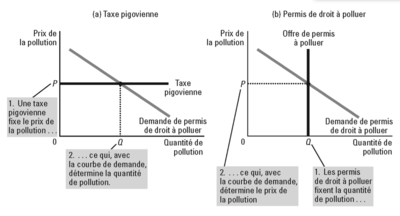

The graphs below compare the Pigouvian tax and tradable emission permits approaches to regulating pollution. Both mechanisms aim to reduce pollution by imposing costs on polluters, but they work in slightly different ways. | |||

[[Fichier:Equivalence des taxes pigouviennes et des droits à polluer 1.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

Pigouvian tax (Graph a): The Pigouvian tax is a price set by the state on pollution. This price is designed to reflect the external cost that pollution imposes on society. The graph shows a horizontal line at a price determined by the tax. The point where this line intersects the pollution demand curve indicates the quantity of pollution that will be produced at the price set by the tax. Polluting companies will pay the tax for each unit of pollution they emit, and this tax is supposed to encourage companies to reduce their emissions until the marginal cost of reducing pollution is equal to the tax. The main advantage of this approach is that it allows companies to decide how they will reduce pollution, giving them the flexibility to find the cheapest solutions. However, the resulting level of pollution is not guaranteed, as it depends on how businesses react to the tax. If the tax is too low, pollution could remain high; if it is too high, it could impose excessive costs on businesses. | |||

Pollution Permit Market (Graph b): In the cap-and-trade system, also known as the pollution permit market, the state sets a cap on the total amount of pollution that can be emitted. Permits corresponding to this cap are distributed or sold to polluting companies. These permits are tradable, which means that companies that can reduce pollution more cheaply will sell their surplus permits to other companies for whom the reduction is more expensive. The graph shows that the price of permits is determined by the point at which the permit supply curve (which is vertical because the number of permits is fixed) intersects the demand curve for the right to pollute. The advantage of this system is that it guarantees a level of pollution that does not exceed the set ceiling. However, the price of permits can vary and can be difficult to predict, which can create uncertainty for companies. | |||

The choice between the Pigouvian tax and the permit market depends on the specific objectives and market conditions. If the main objective is to guarantee a maximum level of pollution, the permit market is more appropriate. If the objective is to encourage companies to innovate and find cost-effective ways of reducing pollution, the Pigouvian tax may be preferable because of the flexibility it offers. Both systems face implementation challenges, including the need to accurately measure pollution and monitor compliance. Lobbies can exert significant influence over the setting of tax prices or the number of permits distributed, which can compromise the effectiveness of each system. In addition, both mechanisms can have social and economic consequences, such as the transfer of costs to consumers, the impact on business competitiveness and the need for a fair transition for workers in the affected industries. | |||

In short, the Pigouvian tax and the market in pollution permits are two environmental policy tools that attempt to correct the market failures associated with the negative externalities of pollution. Their success will depend on how they are integrated into a broader regulatory framework and on how well they are accepted by the public and business. | |||

== Comparative Analysis of the Merits and Limits of Emission Permits and Environmental Taxes == | |||

Pollution permits and pigouvian taxes are two of the main methods used to internalise the negative externalities of pollution. Although both aim to achieve the same objective of reducing emissions, they do so through different mechanisms, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. | |||

Economists tend to prefer Pigouvian taxes for several reasons. Firstly, they are seen as less intrusive into the workings of the market, because they allow businesses to choose how they will adjust to the tax. Instead of dictating how and where to reduce emissions, taxes encourage companies to find the most cost-effective methods for themselves. This can lead to technological innovation, as companies seek to reduce the amount of tax they have to pay. Another advantage is the long-term incentive effect. By taxing pollution, governments create an ongoing financial incentive for companies to invest in the research and development of cleaner technologies. This can lead to lasting improvements in energy efficiency and the reduction of pollutants. | |||

However, Pigouvian taxes also have disadvantages. One of the main problems is that the government has to determine the exact social cost of pollution in order to set the tax at a level that will internalise the external costs. This can be extremely difficult, as the damage caused by pollution can vary considerably depending on many factors, including geography, population density, and the sensitivity of local ecosystems. If the tax is set too low, it will not reduce pollution sufficiently; if it is set too high, it could impose unnecessarily high costs on businesses and consumers. | |||

Pigouvian taxes are therefore often preferred for their flexibility and potential for innovation, but they require precise knowledge of the social damage caused by pollution, which is difficult to quantify. The decision whether to use taxes or permits will depend on the specific circumstances, environmental policy objectives, and the state's ability to gather the necessary information and adjust policies accordingly. In practice, a combination of both approaches, and other policy instruments, may be needed to manage pollution effectively and protect the environment while maintaining economic efficiency. | |||

Direct pollution restrictions or regulations are often preferred for their simplicity and the certainty they provide to both regulators and companies. They prescribe specific emission limits that must be met, which can be particularly beneficial in situations where there is a lack of information about the precise social costs of pollution. These regulations set clear standards and provide predictable results: companies know what is expected of them and regulators have a clear framework for monitoring and enforcement. On the other hand, these regulations have significant disadvantages in terms of providing incentives for improvement. Once a company complies with the standard, there is often little or no incentive to reduce pollution further. This can lead to a state of complacency where companies are content to comply with standards without seeking to excel in environmental performance. In addition, regulations can introduce economic distortions by not encouraging companies to look for ways to reduce costs. They could find themselves stuck with expensive technologies specifically designed to meet regulatory requirements, without exploring other potentially more efficient or less costly options. | |||

The costs associated with regulatory compliance can also be high. The technologies required to meet standards can be expensive, and these additional costs are often passed on to consumers. This can have repercussions on the market in terms of competitiveness and accessibility, as the prices of goods and services rise to cover increased capital investment and operating costs. Restrictions are therefore an important tool in the environmental policy toolbox, providing a guarantee that certain emission levels will not be exceeded. However, they can be rigid and not conducive to innovation and continuous improvement beyond the minimum requirements. Thus, a mix of direct regulation with other economic instruments such as Pigouvian taxes and tradable emission permit systems can offer a compromise between certainty, flexibility and incentives for innovation, leading to a more nuanced and effective approach to pollution management. | |||

= Summary of Concepts and Strategies Addressed = | |||

Externalities arise when a transaction between a buyer and a seller has repercussions on third parties who are neither buyers nor sellers in that transaction. These uncompensated side effects can be either beneficial (positive externalities) or harmful (negative externalities). A negative externality, such as pollution from a factory, leads to overproduction compared with what would be socially ideal, because the external cost is not taken into account in the factory's production decision. Conversely, a positive externality, such as vaccination, leads to underproduction because the benefits to society are not fully reflected in the private incentives of individuals or companies. | |||

In some cases, the parties affected by the externalities can find a solution themselves. Coase's theorem states that if property rights are clearly defined and transaction costs are zero, parties can negotiate compensations that will lead to an efficient allocation of resources, regardless of who initially holds the rights. However, in practice, transaction costs are rarely zero and property rights are not always clearly defined, which often complicates private negotiations. | |||

When private negotiations are not sufficient to resolve externalities, government intervention may be necessary. The government may choose to impose standards of behaviour, which are direct regulations dictating obligations or prohibitions. These standards are easy to understand and can be effective in achieving specific objectives, but they can also be rigid and fail to encourage continuous improvement. | |||

An alternative is the use of economic instruments such as Pigouvian taxes, which seek to internalise external costs by imposing a price on pollution, or the creation of markets for pollution permits, where companies can buy and sell the right to pollute. These market-oriented methods can be more effective and flexible than strict standards, as they allow companies to choose the most cost-effective way of reducing their pollution and encourage innovation over the long term. | |||

Ultimately, the choice of environmental policy instruments depends on many factors, including the nature of the externality, the structure of the industry concerned, and the specific objectives of the policy. A mix of direct regulation and economic instruments can often provide an effective balance between certainty, flexibility and incentives for innovation. | |||

=Annexes= | =Annexes= | ||

Version actuelle datée du 11 janvier 2024 à 11:14

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami[1][2][3]

Microeconomics Principles and Concept ● Supply and demand: How markets work ● Elasticity and its application ● Supply, demand and government policies ● Consumer and producer surplus ● Externalities and the role of government ● Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy ● The costs of production ● Firms in competitive markets ● Monopoly ● Oligopoly ● Monopolisitc competition

The notion of the "invisible hand" described by Adam Smith is a central concept in economics, reflecting the idea that individual actions motivated by self-interest can lead to beneficial results for society as a whole. However, this idea is based on the assumption of perfect competition, which is rarely achieved in practice.

In the real world, the market is often imperfect and subject to various dysfunctions, notably due to the existence of externalities. Externalities are the effects that economic transactions have on third parties who are not directly involved in the transaction. These effects can be positive or negative.