Supply and demand: How markets work

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami[1][2][3]

Microeconomics Principles and Concept ● Supply and demand: How markets work ● Elasticity and its application ● Supply, demand and government policies ● Consumer and producer surplus ● Externalities and the role of government ● Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy ● The costs of production ● Firms in competitive markets ● Monopoly ● Oligopoly ● Monopolisitc competition

The concept of the market is central to economics. It is based on the idea that markets are spaces where the forces of demand and supply interact to determine the prices and quantities of goods and services exchanged. Market equilibrium occurs when the quantity of goods or services that consumers are willing and able to buy (demand) is equal to the quantity that producers are willing and able to sell (supply). This equilibrium point indicates the price at which the good or service will be sold and the quantity that will be traded.

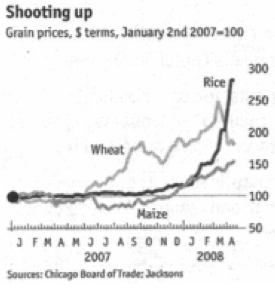

The example of food prices in the 2000s illustrates market dynamics. Price increases can be caused by changes in demand or supply. An increase in demand may be due to a rise in income, population growth or a change in consumer preferences. On the other hand, a decrease in supply may be due to factors such as adverse weather conditions, increases in production costs, or trade restrictions. These market dynamics are important because they affect not only prices, but also the availability of goods and services, having a direct impact on consumers and producers. Understanding these principles is essential for analysing economic policies and market decisions.

In their analysis of the surge in agricultural commodity prices in 2008, ING, in "Directional Economics" of February 2008, makes a critical observation: "There is keen interest in the soft commodity bull run at present. We are not convinced by either the "world population growth" or "Chinese meat eaters" argument. After all neither of these happened overnight, yet the 22% rise global food prices was a one-year jump. Rather it is soaring oil prices, leading to greater demand for bio-fuels and the poor output of key swing producers that have seemed to play the largest role."

This perspective highlights that the significant 22% rise in world food prices cannot be attributed exclusively to global population growth or the increase in meat consumption in China, as these phenomena are not sudden. Instead, ING highlights the role of high oil prices in stimulating demand for biofuels, leading to a reallocation of agricultural crops from food to energy production. In addition, they highlight the low yields of the main food producers, which have also played a significant role in this price rise. This analysis illustrates the complexity of the factors influencing world markets for agricultural commodities. It highlights the interdependence of different economic sectors, showing how changes in one sector, such as energy, can have significant effects on other sectors, such as agriculture and food.

The Economist article of 19 April 2008, "The new face of hunger", sheds light on the formation of equilibrium prices on agricultural commodity markets, emphasising the importance of changes in demand. According to this article, "The price mainly reflects changes in demand - not problems of supply, such as harvest failure. The changes include the gentle upward pressure from people in China and India eating more grain and meat as they grow rich and the sudden, voracious appetites of western biofuels programmes, which convert cereals into fuel. ... Such shifts have not been matched by comparable changes on the farm. ... The era of cheap food is over.

This quote highlights the fact that the main factors influencing prices are not linked to a fall in supply, such as harvest failures, but rather to an increase in demand. This increase is partly due to economic growth in China and India, where people are consuming more cereals and meat as they become wealthier. In addition, biofuel programmes in the West, which convert cereals into fuel, have also contributed to a rapid rise in demand. These changes in demand have not been matched by corresponding increases in agricultural supply, leading to higher prices and the end of the era of cheap food. This perspective reinforces the fundamental economic principle that the equilibrium price on a market results from the interaction between supply and demand. In this context, the imbalance caused by a significant increase in demand without a proportional increase in supply has led to a rise in world food prices.

= Perfectly competitive markets

The market: definition and functioning[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In economics, a market is considered to be a place, whether physical or virtual, where suppliers (producers, suppliers) and demanders (consumers, buyers) meet. The interaction between these two groups determines the price and quantity of goods or services exchanged, leading to what is known as market equilibrium. Market equilibrium occurs when the quantity of goods or services that consumers are willing and able to buy (demand) is equal to the quantity that producers are willing and able to supply (supply). At this equilibrium point, the market price is set to balance demand and supply. If the price is too high, demand falls and excess supply pushes the price down. Conversely, if the price is too low, supply falls and excess demand pushes the price up. This concept of market equilibrium is fundamental to microeconomics and helps to understand how prices and quantities of goods and services are determined in a market economy. It also reflects the way in which markets adjust in response to changes in supply and demand conditions, such as technological innovations, changes in government policy, variations in production costs, or changes in consumer preferences.

This mechanism may be regulated or spontaneous. Depending on the different assumptions, a distinction can be made between a market with pure and perfect competition and one with imperfect competition. In a market characterised by pure and perfect competition, several assumptions are essential. Firstly, there is atomicity, where no buyer or seller has sufficient power to influence the market price. In addition, the products offered are considered to be homogeneous, i.e. identical, making consumers indifferent between different suppliers. Complete transparency of information is also required, ensuring that all market players have access to all relevant information. In addition, companies can freely enter and leave the market without barriers. Finally, perfect mobility of the factors of production is a condition, allowing free readjustment of resources without cost or delay. On the other hand, an imperfectly competitive market is characterised by conditions where one or more of these assumptions are not met. This includes various market structures such as monopoly, where a single seller dominates, oligopoly, dominated by a small number of major firms, monopolistic competition, with many sellers offering slightly differentiated products, and monopsony, with a single dominant buyer. The reality of markets is often somewhere between these two extremes. Government regulation may be necessary, especially where the conditions of pure and perfect competition are not satisfied. Government intervention can be crucial to correcting market failures, encouraging fair competition, protecting consumers and ensuring a fairer distribution of resources.

Analysis of the different market powers of participants in an economic exchange reveals varying dynamics depending on the market structure.

- In a competitive market context characterised by the atomicity of consumers, there are a large number of individuals and each has minimal influence on the market. In this situation, consumers are so small relative to the size of the market that their individual consumption and production choices have no impact on market prices. This ideal scenario of pure and perfect competition allows prices to be determined based on the sum total of the interactions between supply and demand, with no individual player being able to influence these prices in any significant way.

- In contrast, in a monopoly scenario, there is only one seller who dominates the market. This single seller, because of its significant size relative to the market, has considerable power to influence prices. In such a framework, the monopolist has the ability to set prices at a higher level than in a competitive market, because it is not constrained by the presence of competitors. This can lead to market inefficiencies and higher prices for consumers

- On the other hand, a monopsony scenario arises when there is a single dominant buyer facing several sellers. The single buyer, as the only consumer in the market, has considerable market power and can influence prices. In this situation, the monopsonist often has the ability to negotiate lower prices than would prevail in a more competitive market, which can be disadvantageous to sellers and reduce the quantities traded on the market. These varied market structures highlight the way in which market power and the concentration of players influence prices and the efficiency and fairness of economic transactions.

In this case, the players are price-takers because they take the price imposed on them. In such a market, individuals, whether buyers or sellers, accept the market price as it is, because none of them has sufficient power to influence it. In a competitive market characterised by atomicity, where many buyers and sellers exist, each player is in a situation where he has to "take" the price established by the market as a whole. This means that sellers sell their products at the market price and buyers buy them at the same price, without being able to negotiate. The price is determined by the overall intersection of demand and supply for the market as a whole, and not by the decisions or actions of a single player or a small group of players. However, in market structures such as monopolies or monopsonies, this dynamic changes. In a monopoly, the single seller has the power to set the price, while in a monopsony, the single buyer has the power to influence the price. In these cases, the players are not price-takers, but rather price-makers, as they have the ability to determine or influence the market price because of their dominant position.

Pure and perfect competition: criteria and implications[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Pure and perfect competition is considered an "ideal type" of market in economics, where certain ideal conditions are met to allow an efficient allocation of resources without government intervention. In such a market, several key conditions are required to achieve this ideal. Firstly, there is complete atomicity of market participants, i.e. there are a large number of buyers and sellers, and none of them has sufficient market power to influence prices. Secondly, products are homogeneous, meaning that all goods offered on the market are considered identical by consumers, making products perfectly substitutable. Another condition is perfect market transparency. This implies that all relevant information, such as prices, product quality and production costs, is freely available to all participants. In addition, there must be free entry and exit from the market, which means that there must be no barriers preventing new companies from entering or exiting the market.

Under these conditions, markets operate efficiently and fairly, with an optimal allocation of resources. Prices are determined solely by the forces of supply and demand, and reflect the true balance between what consumers are prepared to pay and what producers are prepared to accept. However, it is important to note that pure and perfect competition is a theoretical model. In practice, many markets do not meet all these conditions and exhibit varying degrees of imperfect competition. Government intervention may sometimes be necessary to correct market failures and ensure fairer and more efficient competition.

Adam Smith's theory of the invisible hand is a fundamental concept in economics which suggests that free markets, when functioning properly, can lead to an optimal allocation of resources. Smith postulated that, in a free market, individuals seeking to maximise their own self-interest may unwittingly contribute to an efficient and socially desirable allocation of resources. However, for this theory to work as intended, a set of assumptions must be satisfied.

- Perfect mobility of products and factors of production: This condition stipulates that products and resources (such as labour and capital) must be able to move freely through markets without hindrance. This means that there are no restrictions or significant costs associated with moving resources from one job to another or from one market to another. Product homogeneity: Products on a given market must be considered identical by consumers. This implies the absence of differentiation between products, whether real or perceived, and ensures that consumers do not prefer one product over another for reasons other than price.

- Atomicity of buyers and sellers: The market must be made up of a large number of buyers and sellers, none of whom has sufficient market power to influence the price. This condition ensures that the market price is a given to which buyers and sellers adapt. * No obstacles to the free entry of producers into the market: There must be no significant barriers preventing new companies from entering the market. This promotes competition, prevents market power and ensures that prices remain competitive.

- Market transparency and absence of uncertainty: All market participants must have full and fair access to all relevant information, and there must be no significant uncertainty affecting market decisions. This implies that consumers and producers are fully informed about prices, product quality and other relevant factors.

When these conditions are met, the theory of the invisible hand suggests that the market can operate efficiently and fairly, leading to an optimal allocation of resources without the need for direct state intervention. In practice, however, these ideal conditions are rarely fully satisfied, which may justify some government intervention to correct market failures.

Although Adam Smith's theory of the invisible hand and the model of pure and perfect competition offer ideal theoretical frameworks for understanding markets, their application in reality comes up against numerous imperfections and market failures. The perfect mobility of products and factors of production is often hampered by obstacles such as regulations, customs duties and transport costs. In addition, factors of production such as labour are not always flexible because of constraints such as specialised skills and geographical attachments. Regarding product homogeneity, in reality, many products are differentiated by aspects such as quality, brand and design. This differentiation affects consumer choices beyond price considerations.

In addition, many markets are not characterised by the atomicity of buyers and sellers, but rather by oligopolies or monopolies, where a few companies or a single company have sufficient market power to influence prices. Free market entry is also a challenge, with barriers such as high start-up costs, patents, and regulations that can prevent new companies from competing effectively with established players. Finally, real markets often suffer from a lack of transparency and asymmetric information, where not all participants have access to the same information. Uncertainty is also a common feature affecting economic decisions. These imperfections can lead to inefficiencies, such as sub-optimal prices and misallocation of resources. Consequently, government intervention in the form of regulation, correction of externalities, or protection of property rights may be necessary to mitigate these failures and improve market efficiency and equity.

Demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Fundamental principles of demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The law of demand is a fundamental principle in economics that describes the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity of that good or service that consumers are willing to buy. It states that as the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded of that good tends to increase, all other things being equal (ceteris paribus). Conversely, when the price of a good increases, the quantity demanded tends to decrease.

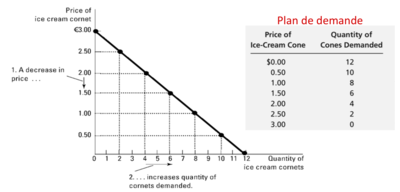

The demand curve is a key graphical tool in economics that illustrates the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity of that good or service that consumers are prepared to buy, taking into account the condition that 'all other things being equal' (ceteris paribus). This condition implies that all other factors influencing demand, such as consumer income, tastes and preferences, and the price of substitute or complementary goods, remain constant during the analysis of the effect of price on the quantity demanded.

The demand curve generally slopes downwards from left to right, meaning that as the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded of that good increases, and vice versa. This downward slope captures the essence of the law of demand: an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. This curve is a fundamental tool for analysing and understanding consumer behaviour and how they react to price changes. It is also useful for companies when making decisions about pricing and production, and for governments when considering fiscal and economic policies that may affect prices and demand in markets. The demand curve helps to forecast the consequences of various market scenarios, such as changes in taxation, regulations, or overall economic conditions.

The image shows a typical demand curve graph, accompanied by a table illustrating the demand pattern for ice cream cones. The graph represents a decreasing demand curve, which means that as the price of ice cream cones decreases, the quantity demanded increases, in accordance with the law of demand. On the vertical axis (the y-axis) we have the price of ice cream cones in euros, and on the horizontal axis (the x-axis) we have the quantity of ice cream cones demanded. The graph clearly shows that when the price decreases from €3.00 to €0.50, the quantity demanded increases from 0 to 10 cones. This illustrates point 1 on the graph: "A decrease in price...". Then, point 2 indicates "...increases the quantity of cones requested". For example, if the price is set at €1.50, the quantity requested would be 6 ice cream cones. The table, entitled "Demand plan", displays a series of prices with the corresponding quantity of ice cream cones requested. As the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases, which is consistent with what the demand curve shows on the graph.

This image clearly demonstrates the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded, and how this relationship can be represented both in tabular and graphical form. This is a fundamental concept in microeconomics that helps to understand consumer behaviour and is essential for the analysis of most markets for goods and services.

Market demand: aggregation of individual demands[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

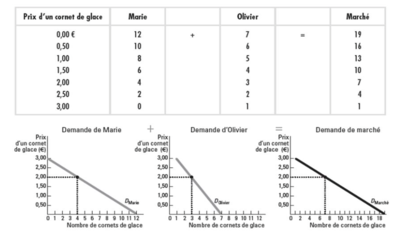

Market demand for a product or service represents the total quantity of that good that all consumers in the market are willing to buy at different price levels. It is obtained by adding together horizontally the quantities demanded at each price by all the individual buyers.

To understand market demand, take a demand curve for a single consumer. Market demand is obtained by adding together horizontally the quantities that each consumer wishes to buy at each price level. So, if at a price of €1.50, consumer A wants to buy 6 cones and consumer B wants 4, the total market demand at this price is 10 cones. Repeat this addition for all price levels and plot these cumulative quantities to obtain the market demand curve. This curve, like the individual curves, will be decreasing, illustrating the law of demand at a global level. It is the market demand curve that is commonly used in economics to represent the total demand for a product or service across the whole market.

This example illustrates how market demand is derived from the individual demands of two consumers, Mary and Oliver. It consists of three main parts: a table of individual and market demands, and two graphs showing individual demands and the combined graph of market demand.

In the first part, we have a table with three columns showing the price of an ice cream cone and the quantities demanded by Mary, by Oliver, and the total quantity demanded on the market. At each price level, the quantity demanded by each individual is added together to give the total market demand. For example, if an ice cream cone costs €0.50, Mary will ask for 10 and Olivier for 6, for a total market demand of 16 cones. The two graphs below the table show the individual demand curves for Mary and Olivier. Each curve shows a typical inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded, in accordance with the law of demand. Mary has a higher demand at all price levels than Olivier, which is reflected in a demand curve further to the right on the graph. Finally, the last graph on the right combines the individual demands to illustrate the market demand. This market demand curve is obtained by horizontally summing the quantities demanded by Mary and Olivier at each price level. The market demand curve shows that, for a given price, the total quantity demanded on the market is simply the sum of the quantities demanded by each consumer.

The importance of this illustration lies in its demonstration of how individual preferences and choices interact to form aggregate demand in a market. It helps to understand that market demand is not simply a linear aggregation of individual demands, but a horizontal sum that must take into account the quantities demanded at each price by all consumers. This is essential for companies when planning production and setting prices, and for decision-makers when assessing the impact of economic policies.

Determinants of demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Influence of price on demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The price of a good is one of the main variables influencing the quantity demanded of that good. When the price of the good changes and the other factors remain constant (ceteris paribus), there is a movement along the existing demand curve, rather than a shift in the curve itself. This movement is called a "movement along the curve".

If the price of the good falls, consumers are generally willing to buy more of that good, causing a downward and rightward movement along the demand curve. Conversely, if the price rises, the quantity demanded falls, resulting in an upward and leftward movement along the curve.

This reaction is due to the substitution effect (consumers choose relatively cheaper goods) and the income effect (consumers have greater effective purchasing power when the price falls), two principles underlying the law of demand. It is important to note that this movement is different from a shift in the demand curve, which would occur in response to a change in another factor influencing demand, such as consumer income or preferences.

The effect of changes in income on demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Changes in consumer income are another determinant of demand that can cause a shift in the demand curve, rather than a movement along the curve.

For normal goods, which are generally goods and services whose demand increases when consumer income increases, the demand curve shifts to the right. This means that at each price level, consumers are prepared to buy more of these goods because they have greater purchasing power. The propensity to consume these goods increases as income rises, reflecting their greater desirability and consumers' ability to buy them. On the other hand, for inferior goods, an increase in income leads to a reduction in the quantity demanded. These are goods for which consumers choose out of budgetary constraint rather than preference. When their income rises, they replace them with better quality or more expensive goods. The demand curve for an inferior good therefore shifts to the left.

As for essential goods, their demand is relatively inelastic in relation to income: consumers have to buy them in the quantities they need, regardless of their income. Changes in income therefore have less effect on demand for these essential goods, but for certain basic necessities considered inferior, we can see a fall in demand as income rises.

These relationships illustrate how the demand function can be influenced by economic changes within a population and how different categories of goods react differently to changes in income. This knowledge is crucial for companies when planning production and market strategies, and for political decision-makers when formulating economic and social policies.

Impact of changes in the prices of associated goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Changes in the prices of other goods can shift the demand curve for a given product, depending on the nature of the relationship between the goods.

Complementary goods are goods that are used together, so demand for one good is often linked to the price of its complement. When the price of one complementary good falls, demand for the other increases, because it is cheaper to use both together. For example, if the price of oil falls, this can lead to an increase in demand for cars, particularly those that consume a lot of fuel, as the cost of using them becomes more affordable. Similarly, if the price of tea falls, this could increase demand for sugar or milk if people tend to consume them together. The demand curve for the main good then shifts to the right to reflect the increase in demand.

Substitutable goods are those that can replace each other in consumption. When the price of a substitutable good rises, consumers look for cheaper alternatives, thereby increasing demand for the substitute good. For example, if the price of coffee rises, consumers may turn to tea as an alternative, thereby increasing demand for tea. In this case, the demand curve for tea shifts to the right, indicating an increase in demand at all price levels.

These interactions show how the market for each product is interconnected with the markets for other products, and how companies need to monitor not only the prices and demand for their own products, but also those for related goods. Similarly, policies that affect the prices of complementary or substitutable goods can have significant knock-on effects on related markets.

The role of consumer tastes and preferences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Consumer tastes and preferences are key determinants of demand. Changes in these tastes and preferences can cause a shift in the demand curve for a product or service.

For example, a successful anti-smoking campaign can change consumers' attitudes towards smoking, reducing their desire to smoke cigarettes. If consumers perceive smoking as less desirable, or if they are more aware of the health risks associated with smoking, their demand for tobacco products will fall. In this scenario, the demand curve for cigarettes would shift to the left, indicating that at each price level, consumers would demand fewer cigarettes than before.

Similarly, if a product becomes fashionable or consumers develop a preference for healthier products, the demand curve for these goods will shift to the right, showing an increase in the quantity demanded at each price. These changes can be influenced by advertising campaigns, cultural changes, fashion trends, technological advances, scientific research publications, etc.

These adjustments in tastes and preferences are important for businesses, which need to adapt quickly to changing trends to remain competitive. Policy-makers must also take this into account when considering interventions in the market, such as public health campaigns or educational policies.

Influence of future expectations on demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Consumers' expectations or forecasts about the future can also influence current demand and cause a shift in the demand curve. When consumers anticipate future changes that may affect the value or utility of a good, they may adjust their current demand accordingly.

Let's take the example of seaside houses in the context of global warming. If consumers expect that global warming will lead to a rise in sea levels that could make seaside homes less safe or susceptible to damage, demand for these properties could fall. Consumers may fear that the value of these homes will fall in the future or that the cost of insurance will rise, making them less attractive as investments. In response to these expectations, the demand curve for seaside homes would shift to the left, reflecting a reduction in the quantity demanded at all price levels. Conversely, if consumers anticipate a future shortage or an increase in the price of a property, they may increase their current purchases to avoid higher costs or limited availability at a later date. This would shift the demand curve to the right.

These expectations are based on forecasts, speculation or proven information about future trends, and they play a crucial role in household economic planning. For businesses and decision-makers, understanding these dynamics is essential for risk management, strategic planning and the implementation of adaptive policies.

Importance of the number of buyers in market demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The number of buyers in the market is another factor determining overall demand for a good or service. Changes in the population, such as population growth or ageing, can lead to a shift in the demand curve.

For example, an ageing population can lead to an increase in demand for retirement homes. As the proportion of elderly people in the population increases, so does the demand for housing adapted to their specific needs. In response to this increase in the number of potential buyers for retirement homes, the demand curve for these services will shift to the right. This means that at each price level, more retirement homes will be in demand than before. Conversely, if the number of buyers falls, for example because of a fall in the birth rate or net emigration, demand for certain goods and services, such as schools or family housing, could fall. The demand curve for these goods and services would then shift to the left.

Demographic changes are therefore key indicators for urban planners, property developers, health service providers and political decision-makers, as they affect not only property markets, but also the planning of infrastructure, health services, education and other community services.

Analysis of movements on the demand curve and curve shifts[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The image shows a demand curve graph illustrating how demand for a good, in this case ice cream, can vary in response to different factors. Three distinct demand curves are represented by red dotted lines, labelled D1, D2 and D3, on a graph with the price of ice cream on the vertical axis and the quantity of ice cream on the horizontal axis.

Curve D1 could represent the initial demand for ice cream. When we see a shift to the right of this curve, from D1 to D2, this indicates an increase in demand. This means that at each price, consumers are prepared to buy more ice cream than before. This shift could be due to various factors, such as an increase in consumer income, the arrival of summer increasing the desire for refreshing products, or a drop in the price of a complementary good such as ice cream cones. Conversely, a shift of the demand curve to the left, from D1 to D3, indicates a decrease in demand. At each price, consumers are now buying less ice cream. This could be the result of a fall in consumer income, colder weather conditions reducing the desire for ice cream, or an increase in the price of a complementary good.

In addition, the graph also shows an arrow entitled "Price variation" pointing downwards along the D2 demand curve, indicating a movement along the demand curve. This movement is due to a change in the price of ice cream, not a change in market conditions. If the price of ice cream falls, the quantity demanded increases, which is illustrated by a downward movement on the D2 curve. This graph is an excellent tool for visualising the concepts of 'movement along a demand curve' in response to changes in price, and 'shifting of the demand curve' in response to changes in other non-price factors. Understanding these concepts is crucial for companies and policy makers, as it helps them to anticipate how changes in the economic environment or in consumer preferences may affect demand for their products or services.

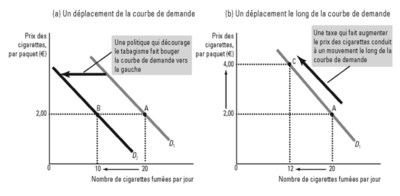

Case study: two strategies for reducing tobacco demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The image illustrates two different ways of reducing the demand for cigarettes through public policy, each with a distinct effect on the cigarette demand curve.

In the first part of image (a), we see a shift of the demand curve to the left, from D1 to D2. This indicates a decrease in overall demand for cigarettes. A policy that discourages smoking, such as awareness campaigns about the harmful effects of tobacco, a ban on advertising tobacco products or restrictions on where smoking is permitted, can reduce the desire to smoke cigarettes, whatever the price. As a result, at all price levels, consumers want to buy fewer cigarettes than before. Point A represents the original quantity of cigarettes smoked per day at a given price, and point B shows the new reduced quantity smoked after the application of the policy.

The second part of image (b) shows a movement along the demand curve. This movement is caused by an increase in the price of cigarettes due to a tax. Point A shows the quantity of cigarettes smoked per day before the tax increase, and point C shows the reduced quantity smoked after the tax increase. In this case, the demand curve does not move; rather, we see a movement along curve D1 towards a higher point on the curve, indicating a lower quantity demanded at a higher price.

These two illustrations demonstrate the impact of policy interventions on tobacco consumption. The first approach changes consumer preferences or behaviour, while the second makes smoking more expensive, thereby reducing the amount of tobacco consumers are willing or able to buy.

The demand function: mathematical expression and analysis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In general , with .

The demand function is a mathematical representation of the relationship between the demand for a specific good and various factors that influence it. Here is an explanation of the notation and what it represents:

- : This is the quantity demanded of the good . This variable is what we are trying to explain or predict using the demand function.

- : This is the price of the good . According to the law of demand, there is an inverse relationship between the price of the good and the quantity demanded, which means that when the price of the good increases, the quantity demanded decreases, hence the partial derivative .

- : This is the price of substitute goods. Substitute goods are those that consumers can use instead of the good . If the price of substitute goods increases, then demand for good may increase.

- : This is the price of complementary goods. If the price of complementary goods falls, this can lead to an increase in demand for the good .

- : Represents consumers' income. If income increases, demand for a normal good also increases

- : Represents consumer tastes or preferences. Changes in tastes can increase or decrease demand for the good .

This demand function describes how these variables interact to determine the quantity demanded of a good and is fundamental in economics.

In a two-dimensional space where only the price variable of good i is allowed to vary while all other variables are held constant (indicated by the bar above the variables), the demand function is simplified to a direct relationship between the quantity demanded of good i and its price. The notation would be as follows:

where:

is the quantity demanded of good i, is the price of good i, , , , and represent respectively the prices of substitute and complementary goods, income and consumer tastes, all considered constant in this analysis. The derivative of the demand function with respect to the price of good i, denoted , is negative, which is consistent with the law of demand:

This means that there is an inverse relationship between the price of the good and the quantity demanded: if the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases and vice versa, assuming that all other factors influencing demand remain constant.

The linear demand function is a specific form of representation of the relationship between the quantity demanded of a good and its price. It is expressed as a simple linear equation. Here is a description of this function:

- The standard form of the linear demand function is given by : , where a and b are constants with . The constant a represents the intercept of the demand curve with the y-axis, or the quantity demanded when the price is zero. The constant b represents the slope of the demand curve and indicates the response of quantity demanded to a change in the price of good i. The condition confirms that the slope of the demand curve is negative.

- The inverse demand function is expressed as . This form shows the price p_i as a function of the quantity demanded and is often used to analyse how the price required to sell a certain quantity of good varies with that quantity. In () space, this is the shape of the demand curve we usually plot with price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. This linear approach simplifies demand analysis by providing a clear and straightforward representation of how price affects quantity demanded.

The offer[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Essential components of supply[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The law of supply is a fundamental principle in economics that describes the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity of that good or service that producers are willing to sell. According to this law, provided that all other factors influencing supply remain constant (ceteris paribus), the quantity of a good offered tends to increase when its price rises. Conversely, if the price of the good falls, the quantity offered tends to fall.

The supply curve illustrates the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity of that good or service that producers are prepared to offer on the market, assuming that all other factors influencing supply remain constant (ceteris paribus). This curve generally slopes upwards from left to right, reflecting the law of supply: when the price of a good increases, the quantity offered of that good also tends to increase, and vice versa. This positive relationship is explained by the fact that higher prices can increase profitability and enable higher production costs to be covered, thus encouraging producers to increase their supply.

A movement along the supply curve occurs when the price of the good changes, leading to a variation in the quantity offered. For example, if the market price of a good rises due to increased demand, producers will have an incentive to offer more of that good, moving towards a higher point on the supply curve. Conversely, a fall in price will lead to a reduction in the quantity offered.

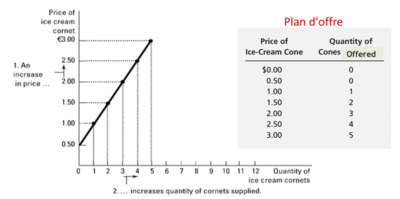

The image shows a graph of the supply curve for ice cream cones and a table, called the "Supply Plan", which shows the relationship between the price of ice cream cones and the quantity offered by producers. The graph shows a supply curve with an upward slope, illustrating the law of supply: when the price increases, the quantity offered also increases. On the vertical axis (the y-axis) we have the price of ice cream cones in euros, and on the horizontal axis (the x-axis) we have the quantity of ice cream cones offered. The point on the curve where the price is €3.00 corresponds to an offer of 5 ice cream cones, while when the price is €0.50, no cones are offered.

The table to the right of the graph provides a tabular representation of the data points on the supply curve. It starts at a price of €0.00 with a quantity offered of 0 cones, indicating that producers are not willing to offer cones for free. As the price rises, the quantity offered increases, reaching 5 free cones when the price reaches €3.00.

The upward arrow marked "1" indicates that the increase in price leads to an increase in the quantity offered, a movement along the supply curve from bottom to top. The arrow to the right marked "2" emphasises that this increase in price leads to an increase in the quantity of cones supplied, indicating movement along the horizontal axis.

Analysis of this graph and the associated table shows how suppliers react to price changes by adjusting the quantity of goods they put on the market. This can be useful for companies to plan their production and for economists to understand market dynamics.

Market supply: sum of individual offers[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Market supply is the sum of the quantities offered by all producers at each price level. To calculate total supply, we simply add up the quantities that each producer is prepared to supply at a given price. For example, if at a price of €1.50, one producer is prepared to sell 200 units of a product and another producer 300 units, the total market supply at this price is 500 units. By performing this operation for each possible price, we draw the market supply curve, which shows the total quantity that producers make available on the market at different price levels. This curve follows the same bottom-up logic as the individual supply curves, reflecting the tendency of producers to increase their supply as the price rises. This aggregation is essential for economic analysis, as it enables us to understand the impact of prices on overall market supply.

This image illustrates how the market offer for ice cream cones is determined by adding together the offers from two separate producers, Häagen and Dasz. It consists of a table and three corresponding graphs.

The table shows the quantities of ice cream cones that each of the two producers is prepared to offer at different price levels, ranging from €0.00 to €3.00. For each price, the quantities offered by Häagen and Dasz are added together to give the total market supply. For example, at a price of €2.50, Häagen offers 3 cones and Dasz offers 4, giving a total market offer of 7 cones at this price.

The first two graphs show the individual bids from Häagen and Dasz, with price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. Each curve shows a direct and positive relationship between price and quantity offered, consistent with the law of supply. These two curves are then added together horizontally to form the third graph, which represents total market supply. In the market supply graph, we can see that the combined supply of Häagen and Dasz at each price creates a new supply curve with an upward slope. At a price of €3.00, for example, the market offer is 13 cones, resulting from the addition of the 5 cones offered by Häagen and the 8 cones by Dasz.

This illustration clearly shows the principle of aggregation of supply and how market supply can be affected by the entry or exit of individual producers. This is an important aspect of market analysis, as it helps to understand how variations in market conditions, such as changes in production costs or government policies, can affect the total supply available to consumers.

Factors influencing supply[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Impact of price on supply[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The price of a good is an essential factor influencing the quantity of that good that a producer is prepared to offer on the market. According to the law of supply, if the price of a good rises, while holding other factors constant, producers will generally be prepared to sell more of that good, as they can obtain a higher income from their sales. This results in an upward movement along the supply curve.

Conversely, if the price of the good falls, producers will be inclined to offer less of that good on the market, as the sale of each unit becomes less profitable. This change is represented by a downward movement along the supply curve.

The supply curve itself does not change as a result of price changes; instead, there is a movement along the existing curve. Other factors, such as changes in production costs, technology, the number of producers in the market, or government policies, can shift the supply curve to the left or right.

Consequences of changes in input prices[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The price of inputs, or factors of production, is another element that influences the supply of a good. When the cost of raw materials, labour, energy or other inputs rises, so do the overall production costs for the companies that produce the good. As a result, unless the increase in costs is offset by an increase in the price of the good produced, companies could reduce the quantity offered, as the production of each additional unit becomes less profitable.

Let's take the example of soya and oil again: if the price of oil rises, the costs associated with the transport and agricultural production of soya may increase because oil is a direct or indirect input into these activities. This rise in production costs can make soya production less profitable at unchanged selling prices, leading farmers to offer less soya on the market. The supply curve for soya would then shift to the left, illustrating a reduction in supply at each price level.

Companies may also seek to pass on higher input costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. If the market cannot bear the higher price, the company may be forced to reduce production. This responsiveness of supply to changes in input prices is crucial to understanding how fluctuations in input costs affect the overall economy and supply levels in different markets.

[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

An increase in the price of soya can lead to a shift in the supply curve for other goods that use the same resources, such as land for livestock farming in Argentina. If Argentine farmers find it more profitable to grow soya than to devote their land to livestock farming, they may decide to convert pastureland into soya fields. This would reduce the space available for livestock farming, thereby reducing the supply of livestock or meat on the market.

As a result, the supply curve for livestock products would shift to the left, meaning that, at each price level, less meat would be available on the market. This shift reflects a reallocation of resources in response to changes in the relative prices of goods.

This phenomenon illustrates how the supply of one good can be affected by changes in the relative profitability of other goods, especially in industries where resources such as land can be used for different productions. It also highlights the importance of production decisions based on price signals and how they can have wider consequences for the economy and for the markets concerned.

Technology's impact on supply[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Technological progress is a key driver of change in supply conditions and can shift the supply curve. When technology in a given sector improves, it can make production more efficient, reduce costs and increase productivity. This is often the case in agriculture, where the introduction of new technologies can have a significant impact on the supply of agricultural products.

The example of transgenic soya illustrates this phenomenon perfectly. The introduction of genetically modified soya varieties has enabled farmers to increase their yields per unit area thanks to improved resistance to pests and diseases, a reduction in the need for chemical inputs, and better tolerance of certain climatic conditions. As a result, the amount of soya that farmers can produce has increased. This translates into a shift of the supply curve to the right, indicating that at any given price, more soya is available to be offered on the market. This increase in supply can also lead to a drop in prices, which can benefit consumers and stimulate the use of soya in various food and industrial products.

The impact of such technological innovations is profound, as they can not only transform entire industries, but also have effects on national and global economies, particularly in sectors where goods are traded on world markets.

Effect of forecasts on supply decisions[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Expectations or forecasts about the future can significantly influence companies' production decisions and, as a result, shift the supply curve. If producers anticipate events that could negatively affect their ability to sell or produce in the future, they may choose to reduce their current production levels.

If, for example, farmers in Uruguay are expecting a reappearance of foot-and-mouth disease, a disease affecting cattle, they may be reluctant to invest in livestock because of the risk of significant losses. This could include investment in the livestock itself, in livestock infrastructure, or in livestock technology.

Such a forecast may cause the supply curve to shift to the left, reflecting reduced supply at each price level. Farmers could sell more livestock now in anticipation of future problems, reduce the size of their herds or not expand them at the previous rate, leading to an overall reduction in the supply of meat and other livestock-related products on the market.

This shows how expectations about the future play a crucial role in production planning and decisions. Producers react not only to current market conditions, but also to their perceptions of future developments, which can lead to proactive adjustments in supply.

Importance of the number of sellers on overall supply[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The number of sellers in a market is a key determinant of the total supply available. When new sellers enter the market, they bring with them additional production capacity, which can increase the total supply of goods or services.

Let's take the example of the appearance of new telephone companies on the telecommunications market. The entry of these new players can significantly increase the supply of telecommunications services, as each new company adds its own offering to that already present on the market. This results in a shift of the supply curve to the right, reflecting an increase in the quantity offered at all price levels.

A market with a greater number of sellers can also become more competitive, which can lead to lower prices, improved quality and greater innovation as a result of competitive pressure. Increased competition can encourage existing businesses to become more efficient and look for new ways to attract customers.

The impact of the entry of new sellers is not limited to an increase in the quantity on offer; it can also change the dynamics of the market in more complex ways, influencing the pricing strategies, marketing investments and innovation efforts of all the companies involved.

Examining movements on the supply curve and shifts in the curve[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

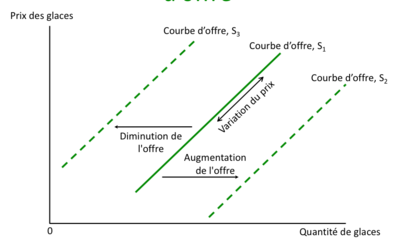

The image below shows a graph representing three different supply curves for ice cream, labelled , , and , with the price of ice cream on the vertical axis and the quantity of ice cream on the horizontal axis.

The curve can be seen as the initial supply curve. If we observe a shift to the right to arrive at the curve, this indicates an increase in supply: at each price level, producers are willing to sell more ice cream than before. This shift could be due to a variety of factors, such as technological improvements, lower production costs, or new producers entering the market.

Conversely, a shift of the supply curve to the left, to arrive at the curve, indicates a decrease in supply: at each price level, producers offer less ice cream than before. This shift to the left could be caused by factors such as increased production costs, stricter government regulations, or natural disasters that disrupt production.

The arrow labeled "Price Change" illustrates a movement along the supply curve, indicating that if the price of ice cream increases, the quantity offered also increases, which is consistent with the law of supply. It is important to note that a movement along the supply curve occurs in response to a change in price and not due to changes in external conditions.

The graph is therefore an excellent teaching tool for showing the difference between a 'movement on' the supply curve, which is caused by changes in price, and a 'movement off' the supply curve, which is caused by changes in production or market conditions. Understanding this distinction is crucial for analysing producers' responses to market changes and for formulating economic policies.

The supply function: representation and interpretation[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The supply function represents the relationship between the quantity of a good on offer and a number of factors that influence that supply. In mathematical terms, the general supply function could be written as follows:

, where each variable represents a specific factor that affects supply:

- is the quantity offered of the good .

- is the price of the good , and according to the law of supply, there is a direct relationship between the price of the good and the quantity offered, hence the positive partial derivative .

- represents the price of labour, or the cost of labour, which is one of the costs of production. Changes in the price of labour can influence the cost of production and thus the quantity offered of the good.

- is the price of capital, which includes machinery, buildings, and other forms of investment. The cost of capital is also an important cost factor for producers.

- represents the state of technology. Technological improvements can increase efficiency and reduce production costs, which can increase the supply of a good

- Other variables indicated by can include factors such as environmental conditions, government policies, subsidies, taxes, and other external influences that could affect the quantity offered of the good . The supply function captures how these variables interact to determine the quantity of a good that producers are willing and able to sell on the market.

In a two-dimensional space where only the price variable of good i is allowed to vary while all other variables such as the price of labour w, the price of capital r, and the state of technology A are held constant (indicated by the bar above each variable), the supply function is simplified to a direct relationship between the quantity offered of good i and its price. This relationship is expressed as follows:

where:

is the quantity offered of the good , is the price of the good , The barred variables , , and represent the price of labour, the price of capital, and the state of technology, respectively, all of which are assumed constant in this supply analysis. The derivative of the supply function with respect to the price of the good , denoted , is positive:

This means that there is a direct relationship between the price of the good and the quantity offered: if the price increases, the quantity offered also increases, which is consistent with the law of supply. This simplification is useful for economic analysis because it allows us to focus on the relationship between price and quantity offered, temporarily eliminating the effects of other variables.

In the context of a linear supply function, we have a direct and simple relationship between the quantity offered of a good and the price of that good:

The specific form of the linear supply function is expressed as: , where c and d are constants. The constant c represents the quantity offered when the price is zero (the intercept of the supply curve with the quantity axis), and d is the slope of the supply curve. In accordance with the law of supply, the slope d is positive, as indicated by the partial derivative .

The inverse supply function, which rearranges the formula to express the price as a function of the quantity offered, is given by : . This inverse equation is used to determine the price required to sell a certain quantity of the good on the market. In a graph representing this supply function in space, the price is usually on the vertical axis and the quantity offered on the horizontal axis.

These linear formulations of the supply function are useful for modelling simple economic relationships and for economic analysis, as they provide a clear way of visualising and understanding how changes in price affect the quantity of a good that producers are willing to offer on the market.

Market equilibrium[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Determining market equilibrium[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The image shows a typical graph of market equilibrium in economic analysis, showing the demand and supply curves for ice cream. The price is measured on the vertical axis in Swiss francs (CHF), and the quantity of ice cream is measured on the horizontal axis.

The demand curve is represented by the red line descending from left to right, showing that the lower the price of ice cream, the greater the quantity demanded, following the law of demand. The supply curve is the green line rising from left to right, showing that the higher the price, the greater the quantity offered, which follows the law of supply.

Market equilibrium is reached at the point where the two curves cross. At this point, the quantity demanded by consumers is equal to the quantity offered by producers. The "Equilibrium Price" () is the price at which this crossing occurs, and the "Equilibrium Quantity" () is the corresponding quantity. In this state of equilibrium, there is neither a surplus nor a shortage of ice cream on the market.

The text at the top of the graph, "Demand meets supply: System of two equations in two unknowns", explains that market equilibrium can be conceptualised as a system where the demand function is equal to the supply function , which gives a set of values for the equilibrium quantity () and the equilibrium price ().

This equilibrium model is fundamental to microeconomics because it describes how market forces interact to determine price and output levels in a free market. Variations in market conditions, such as changes in production costs or consumer preferences, will result in shifts in the demand or supply curves, leading to a new equilibrium.

Market forces: adjustment mechanisms towards equilibrium[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In a competitive market, there are restoring forces that tend to return the market to equilibrium if it moves away from it. These forces are the consequence of the way consumers and producers react to market prices.

If the price is below the equilibrium price, a shortage is created because the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity offered. Consumers are then prepared to pay a higher price for the good, which puts upward pressure on the price. In response, producers have an incentive to increase production because of the prospect of higher profits, which increases supply. As supply increases, the shortage is alleviated and the price tends to return towards the equilibrium level.

Conversely, if the price is higher than the equilibrium price, there is a surplus: the quantity offered is greater than the quantity demanded. In this case, companies are competing to sell their products and are therefore likely to lower their prices to attract consumers. As the price falls, producers have less incentive to produce as much, and supply falls. The reduction in supply, coupled with the fall in price, reduces the surplus until the market reaches equilibrium again.

These adjustments are often described as an "invisible hand" mechanism that guides markets towards equilibrium. In the absence of external barriers or regulations that impede the functioning of the market, these restoring forces operate automatically through the individual decisions of consumers and producers, all guided by their personal interests.

Situations of market imbalance[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Analysis of excess demand and its implications[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The image shows a graph of market equilibrium for ice cream with the price in Swiss francs (CHF) on the vertical axis and the quantity of ice cream on the horizontal axis. Two curves are shown: the supply curve, which is rising (green), and the demand curve, which is falling (red).

The point where the two curves cross represents market equilibrium. However, the graph illustrates a situation of imbalance where the price is set at CHF 1.50, which is below the equilibrium price (marked by the dotted grey line). At this price of CHF 1.50, the quantity demanded (point on the demand curve) is higher than the quantity offered (point on the supply curve), creating a shortage indicated by the grey space between the two quantities.

(1) Excess demand (shortage): At CHF 1.50, there is a demand for 10 units of ice cream, but only 4 units are offered, creating an excess demand of 6 units. This imbalance is known as a shortage.

The shortage creates pressure for the price to rise, as consumers are prepared to pay more for the product. Theoretically, this pressure on the price will continue until the price reaches the level where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied, i.e. the equilibrium price.

In a market economy, the forces of competition between consumers wishing to acquire the good and producers seeking to maximise their profits will naturally cause the price to converge towards the equilibrium level, assuming there are no barriers to this adjustment, such as price regulation or production quotas.

Assessing oversupply and its consequences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

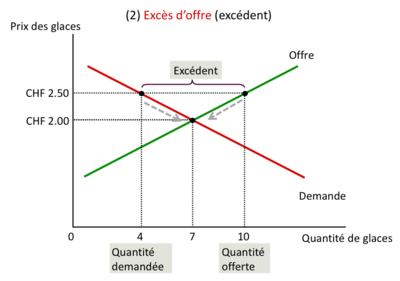

The image shows another example of an imbalance in the ice cream market, with the price in Swiss francs (CHF) on the vertical axis and the quantity on the horizontal axis. The supply and demand curves are represented by the green and red lines respectively.

In this scenario, the price is set at CHF 2.50, which is higher than the equilibrium price (not shown on this graph but inferred by the position of the curves). At this price, the quantity offered (point on the supply curve) exceeds the quantity demanded (point on the demand curve), resulting in a surplus illustrated by the grey space between these two points.

(2) Excess supply (surplus) : At CHF 2.50, there is a supply of 10 units of ice cream, but demand is only 4 units, creating an oversupply of 6 units. This situation is called a surplus.

A surplus creates downward pressure on the price, as producers will seek to sell their surplus ice, potentially by lowering the price to stimulate demand. Theoretically, this pressure on the price will continue until the price falls to the level where the quantity offered equals the quantity demanded, thus returning the market to equilibrium.

These market adjustment forces operate through competition between producers, who, in their search for outlets for their products, have an incentive to lower their prices when there is a surplus. This demonstrates the self-regulation of the market where, in the absence of external intervention, prices and quantities adjust naturally to return to equilibrium.

Market reactions to a demand shock[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The image shows a market equilibrium graph for ice cream with a change in the demand curve, indicating a demand shock. Here are the key elements illustrated on the graph:

- Increase in demand due to a hot summer: The initial demand curve (solid red line) shifts to the right to become the final demand curve (dotted red line). This suggests that due to a very hot summer, demand for ice cream has increased at all price levels.

- Result in a higher price: The increase in demand results in excess demand at the initial equilibrium price (CHF 2.00), illustrated by the vertical distance between the two demand curves at this price. To resolve this excess demand, the price increases until it reaches a new equilibrium point where the supply curve crosses the new demand curve (dotted line).

- Increase in quantity sold: At the new equilibrium price (CHF 2.50), the quantity sold is also greater, as illustrated by the quantity on the horizontal axis at the point where the new supply and demand curves cross.

What the image shows is a classic example of what happens when there is a positive demand shock. The increase in demand for ice cream due to the hot summer has led to both an increase in the equilibrium price and an increase in the equilibrium quantity. Producers respond to the higher price by offering more ice cream, while consumers adjust the quantity they are prepared to buy to the new higher price. This is an example of how markets naturally adjust to changes in demand conditions.

Impact of a supply shock on market equilibrium[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The image shows a graph of the ice cream market undergoing a negative supply shock. Here is what the graph shows and how it is interpreted:

- Negative supply shock: There has been an increase in the price of sugar, an essential ingredient in the manufacture of ice cream. This increase has led to a decrease in the supply of ice cream, as indicated by the shift from the initial supply curve (solid green line) to the final supply curve (dotted green line), which moves upwards and to the left. # Price increase: The shift in the supply curve has created excess demand at the initial equilibrium price (CHF 2.00), where the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. To eliminate this excess demand, the price increases, finding a new equilibrium at CHF 2.50. # Decrease in quantity sold: At the new equilibrium price, the quantity sold is lower than at the initial equilibrium price. This is due to a reduction in the supply of ice cream as a result of higher production costs.

The graph shows that a negative supply shock (such as an increase in input costs) reduces the quantity offered and increases the equilibrium price, which in turn reduces the quantity sold. This is an illustration of how fluctuations in production costs can affect prices and quantities on the market. Consumers end up paying more for less product, while producers may see their surplus fall as a result of higher production costs.

Assessing the effects of simultaneous changes on supply and demand[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

When demand and supply are simultaneously affected by shocks, the combined effect on the market's equilibrium price and quantity can be complex and depends on the relative magnitude of each shock. Here's how these situations can affect the market:

- Simultaneous increase in supply and demand: If demand and supply increase at the same time, it is certain that the equilibrium quantity will increase. However, the effect on the equilibrium price will depend on which of the two increases is greater. If the increase in demand is greater than the increase in supply, the price could rise, while if the increase in supply is greater, the price could fall.

- Simultaneous decrease in supply and demand: In this case, the equilibrium quantity will certainly decrease. For the price, if the fall in demand is more pronounced than the fall in supply, the equilibrium price will fall. Demand increases and supply decreases: This situation will certainly lead to an increase in the equilibrium price, since higher demand pushes up prices and reduced supply means that there is less product available at the same price. The effect on the equilibrium quantity is uncertain and will depend on the relative size of the increase in demand compared to the decrease in supply.

- Demand decreases and supply increases : Here, the equilibrium price will surely fall because the decrease in demand puts downward pressure on prices and the increased supply means that more products are available to sell. The effect on the equilibrium quantity is uncertain and will depend on which of the two changes is more significant.

In practice, economists and market analysts often need to assess the relative size and impact of demand and supply shocks in order to predict price and quantity adjustments. This assessment can be complex and usually requires detailed data on the market and the factors influencing demand and supply.

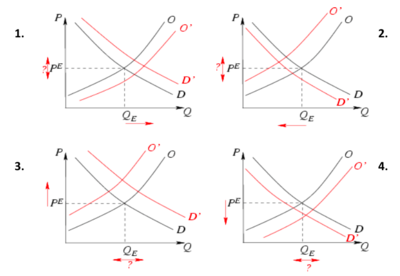

The image shows four graphs illustrating the effects of simultaneous demand and supply shocks on the market. Each graph shows the initial demand and supply curves ( and ) and the new curves after the shocks ( and ).

- Simultaneous increase in demand and supply: The demand curve shifts to the right (), indicating an increase in demand, and the supply curve also shifts to the right (), representing an increase in supply. The result is a higher equilibrium quantity ( increases). The effect on the equilibrium price () is uncertain without additional information on the magnitude of the shifts in and .

- Simultaneous decrease in demand and supply: both curves shift to the left ( and ). The equilibrium quantity decreases ( decreases), but the effect on the equilibrium price () is indeterminate without knowing the relative magnitude of each shock.

- Demand increases and supply decreases: The demand curve shifts to the right (), and the supply curve shifts to the left (). The equilibrium price () increases. The effect on the equilibrium quantity () depends on the relative magnitude of the increase in demand compared to the decrease in supply.

- Demand decreases and supply increases: The demand curve shifts to the left (), and the supply curve to the right (). The equilibrium price () decreases. The equilibrium quantity () could increase or decrease, depending on which curve moves more.

These graphs are fundamental tools in microeconomics for visualising and predicting the effects of market shocks. They illustrate the importance of understanding the direction and magnitude of demand and supply shocks to determine how equilibrium prices and quantities will be affected.

Summary of market dynamics[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

This table provides a systematic view of the interactions between changes in supply and demand and their consequences for the equilibrium price and quantity in a market. Initially, if neither demand nor supply changes, the market remains in equilibrium with a stable price and quantity. When demand increases without any change in supply, more consumers want to buy the good, which pushes up the equilibrium price and quantity. Conversely, if demand falls while supply remains constant, fewer goods are demanded, leading to a fall in the equilibrium price and quantity.

If we look at situations where supply changes, an increase in supply with stable demand leads to a fall in the equilibrium price due to the greater availability of the good, while the equilibrium quantity increases. When this increase in supply is coupled with an increase in demand, the equilibrium price may fluctuate indeterminately due to the tension between upward pressure on the price from increased demand and downward pressure from increased supply; however, the equilibrium quantity is certain to increase. If demand falls at the same time as supply rises, the equilibrium price is certain to fall, but the equilibrium quantity is uncertain because it depends on the relative strength of the fall in demand compared with the rise in supply.

When supply falls with constant demand, there are fewer goods available to consumers, which increases the equilibrium price and reduces the equilibrium quantity. If this reduction in supply occurs at the same time as an increase in demand, then the equilibrium price will undoubtedly rise, as there is increased competition for fewer goods, but the impact on the equilibrium quantity remains ambiguous. Finally, if demand and supply fall simultaneously, the equilibrium price could move in either direction depending on the relative magnitude of the falls, while the equilibrium quantity will necessarily fall as a result of the fall in both demand and supply.

This summary captures the complex dynamics of markets and demonstrates that market equilibrium adjustments are not always straightforward or intuitive, particularly when there are simultaneous changes in supply and demand. These interactions are essential for economic analysts and policy makers to understand and predict market behaviour.

Specific considerations: the oil market as a case study[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Based on this figure, how can we explain the trend in the price of oil and transactions on the world crude oil market?

This chart is a graph with two series of data representing the evolution of the oil price (quotation) and the volume of transactions on the world crude oil market over a given period, with time on the x-axis. Due to the resolution of the image, the specific details and time scale are difficult to discern, but here is a general interpretation based on the information provided:

- Movements in demand and supply: If both curves (price and trading volume) move in the same direction (either both up or both down), this suggests that changes in demand for oil are more pronounced than changes in supply. For example, if prices and volumes are rising simultaneously, this could indicate that demand for oil is increasing faster than supply can keep up, creating upward pressure on prices.

- Opposite directions of prices and trading: When prices and trading volumes move in opposite directions, this could indicate that supply is reacting more volatile than demand. For example, if the price rises but the volume of transactions falls, this could suggest that although supply is contracting (or demand is rising sharply), the reduction in the quantity available on the market is significant enough to push prices up despite a lower volume of transactions.

The chart therefore depicts oil market trends through two key indicators: the oil price and trading volume. Looking at the curves, we can see a general trend towards higher oil prices over time, which could signal growing demand on world markets, probably fuelled by economic growth and increased energy consumption. This rise in prices is often accompanied by an increase in the volume of transactions, suggesting that buyers are prepared to acquire more oil even at higher costs, possibly in anticipation of future needs or in response to forecasts of tighter supply. However, the chart also reveals periods when prices rise while trading volume does not increase as quickly or stabilises. These times could reflect supply constraints or events that limit the availability of oil, such as political decisions, geopolitical conflicts affecting producing regions, or natural disasters disrupting the extraction and transportation of oil. These factors can reduce the supply available on the market and, as a result, push up prices despite lower trading activity.

Analysis of this chart involves considering how various global events and economic cycles influence both the demand for and supply of oil. Changes in these two elements are essential to understanding the dynamics of the oil market. A precise understanding of the trends observed would require a detailed exploration of the exact figures, specific dates, and relevant events that occurred during the periods shown on the x-axis. This would put price and volume movements into context and offer a more nuanced interpretation of the forces at play in the oil market.

Conclusions and general summary[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In the economic analysis of competitive markets, the supply and demand model is a fundamental tool used by economists to study the interactions between buyers and sellers. A competitive market is characterised by a large number of buyers and sellers, none of whom has a significant influence on the market price. In such a market, the price is determined by the collective convergence of buying and selling decisions.

The demand curve illustrates the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity of that good that consumers wish to buy. This relationship is generally inverse, meaning that when the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded increases, and vice versa. This inverse relationship is known as the law of demand, and is reflected in the downward slope of the demand curve. However, demand is also influenced by other factors, such as consumer income, the price of complementary and substitutable goods, tastes and preferences, future expectations and the total number of buyers on the market. When one of these non-price factors changes, the demand curve shifts to the left or right.

Similarly, the supply curve represents the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity that producers are prepared to sell. According to the law of supply, an increase in price leads to an increase in the quantity offered. This direct relationship is reflected in an upward sloping supply curve. Factors other than price that influence production decisions include input costs, technology, expectations about the future and the number of sellers. A change in any of these factors will shift the supply curve.

The point where the supply and demand curves cross is called the market equilibrium. At the equilibrium price, the quantity that consumers are prepared to buy corresponds exactly to the quantity that producers are prepared to sell. Changes or shocks to supply or demand will cause this equilibrium to adjust, thereby altering the equilibrium price and quantity in the market.