Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami[1][2][3]

Microeconomics Principles and Concept ● Supply and demand: How markets work ● Elasticity and its application ● Supply, demand and government policies ● Consumer and producer surplus ● Externalities and the role of government ● Principles and Dilemmas of Public Goods in the Market Economy ● The costs of production ● Firms in competitive markets ● Monopoly ● Oligopoly ● Monopolisitc competition

Public goods are a fundamental concept in the study of public economics and market failures. These goods, characterised by their intrinsic non-divisible nature and their availability for collective consumption, pose unique challenges to private markets. Non-excludability and non-rivalry are key properties of public goods, meaning that their use by one person does not prevent others from benefiting from them, and that it is not possible to exclude individuals from their consumption. This leads to the free rider problem, where individuals benefit from a good without contributing to its financing.

Moreover, state intervention is often necessary in markets where externalities, i.e. effects on third parties not considered in the market process, are important. This can be seen in sectors such as motor vehicles or refrigerators, where pollutant emissions affect air quality for society as a whole. Similarly, conservation and biodiversity raise important questions about the exploitation of natural resources. Some plant and animal species are threatened with extinction as a result of over-exploitation by unregulated markets, often due to a lack of clear property rights.

In this context, market failure occurs when the market mechanism alone fails to allocate resources efficiently to achieve a social optimum. This requires the intervention of the state or public authorities to correct these failures and ensure that resources are allocated efficiently and equitably. This introduction to public goods highlights the complexity and importance of their management in a modern economy.

Understanding the Nature of Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Definition and Characteristics of Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Public goods and externalities share a number of common characteristics that place them at the heart of discussions on economics and public policy. These goods often face misallocation by the market, which means that the market alone fails to provide these goods in optimal quantity or quality. This is largely due to the presence of strong externalities associated with these goods.

Externalities, whether positive or negative, are effects induced by an economic activity that affect other parties without these effects being reflected in market prices. For example, pollution is a negative externality, while education has positive externalities. In the case of public goods, these externalities are often so important that they lead to underproduction or even a lack of production in a completely private economy.

This is mainly because private producers may find it difficult to make the production of these goods profitable, because they cannot easily exclude non-payers (free rider problem) or because the consumption of these goods does not reduce their availability to others (non-rivalry).

In these situations, the state or public institutions can play a crucial role. Public policy can compensate for these market failures by taking responsibility for the supply of public goods. This can be done by producing these goods directly, financing them through taxation, or regulating and providing incentives to encourage their production and consumption. By doing so, the state can increase overall well-being by ensuring that these essential goods are available to society as a whole.

Public goods, a key concept in economics, can be concisely characterised by three main features.

Firstly, the production of public goods is often associated with strong economies of scale. This means that the average cost of producing these goods decreases as the quantity produced increases. This property is particularly relevant for public goods because it suggests that their production by a centralised entity, often the state, can be more efficient than dispersed production by multiple private players. Indeed, the greater the volume of production, the lower the unit cost, making large-scale production economically advantageous.

Secondly, public goods are characterised by their "shared" nature. In other words, they benefit society as a whole rather than specific individuals or groups. This characteristic is often described in terms of non-exclusion and non-rivalry. Non-exclusion implies that no one can be prevented from consuming the good, while non-rivalry means that the consumption of the good by one person does not impede its consumption by another. Typical examples include national defence, public lighting and road infrastructure.

Finally, a third important aspect concerns property rights. For many public goods, property rights are non-existent, vague or poorly respected. This can lead to difficulties in managing and conserving these resources. The absence of clearly defined property rights can lead to over-use or under-use, as illustrated in the concept of the tragedy of the commons, where shared resources are depleted by unregulated individual use.

These characteristics together underline why public goods often pose a challenge to market mechanisms and why state intervention is frequently necessary to ensure their adequate provision and effective management.

The Key Properties of Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The distinctions between public and private goods in economics are essentially based on two key properties that determine how these goods can be provided in the market: non-excludability and non-rivalry.

Non-exclusion refers to the difficulty, if not the impossibility, for the producer to exclude consumers from using a good. In the case of public goods, this characteristic means that no one can be prevented from benefiting from the good, regardless of whether or not they have contributed to its financing. A classic example is national defence: once it has been set up, it is impossible to exclude citizens from its protection, whether they have paid taxes or not.

Non-rivalry, on the other hand, refers to the situation where the consumption of the good by one person does not prevent or reduce the consumption of the same good by another person. In other words, the marginal cost of supplying the good to an additional consumer is zero. This is typical of public goods such as television programmes or radio, where consumption by one individual does not prevent others from enjoying it as well.

In contrast, private goods are generally characterised by the possibility of exclusion and rivalry. For example, if you buy an apple, you can exclude others from consuming it (exclusion), and your consumption prevents anyone else from eating that same apple (rivalry).

These fundamental differences between public and private goods greatly influence the way they are produced, distributed and financed in an economy. Public goods, because of their nature, often require public intervention or financing to ensure that they are provided adequately, as private markets may not produce them optimally because of these unique characteristics.

The Non-Rivality of Public Goods Explained[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The notion of non-rivalry in consumption is a fundamental element in the understanding of public goods. It arises when, once a good has been produced, the additional cost of enabling an additional person to consume that good is zero. This concept plays a crucial role in differentiating public goods from private goods. Take the example of a lighthouse: once it has been built and lit, the cost of lighting an additional boat represents no additional cost. The lighthouse works in the same way, whether for a single boat or for several boats at sea. This is a perfect illustration of non-rivalry, because the consumption of the good (the light from the lighthouse) by one boat does not prevent or reduce its availability to other boats.

In the same way, infrastructure such as bridges and motorways demonstrate this characteristic. Once built, the cost of an additional car using them is negligible. Similarly, the enjoyment of a landscape or the security provided by the police or national defence services are examples where consumption by one individual does not hinder that of others. This characteristic of non-rivalry is essential because it means that the good can be consumed simultaneously by multiple people without incurring significant additional costs. As a result, this poses challenges for the financing and provision of these goods by the private sector, as it is difficult to charge users directly for their consumption. This often leads to the need for public intervention to ensure that these goods are available for the benefit of all, reflecting their importance to society as a whole.

Private goods are distinguished from public goods by their characteristic of rivalry in consumption. Rivalry means that the consumption of a good by one person prevents or limits its consumption by another. This is typical of the majority of goods and services that we consume on a daily basis. The example of the chocolate bar illustrates this notion perfectly. When one person consumes a bar of chocolate, they remove it from availability to others. The consumption of this bar of chocolate is exclusive; once it has been eaten by someone, it can no longer be consumed by anyone else. This is the principle of rivalry: consumption of the good by one person directly reduces the quantity available to others.

This characteristic of rivalry in private goods leads to market dynamics that are different from those of public goods. In a private goods market, producers can exclude those who do not pay for the good, and consumption is regulated by price. Consumers who are willing and able to pay the price can obtain the good, while others are excluded. This market logic is less complex to manage than that of public goods, where non-exclusion and non-rivalry often require external intervention, such as that of the state, for efficient and equitable distribution.

There is an important distinction in understanding public goods: the difference between the marginal cost of production and the marginal cost of consumption by an additional consumer. The marginal cost of producing a good, such as a motorway, can increase as the density of the network increases. This means that as the network grows, the cost of building each additional kilometre can increase, due to factors such as increased complexity, space constraints, or the materials required.

However, once the motorway is built, the cost associated with the consumption of this good by an additional user is zero or very low. This illustrates non-rivalry: an additional driver on the motorway costs virtually nothing extra in terms of resources or infrastructure, as long as the motorway is not saturated. This situation also highlights the indivisibility of public goods. Once a good, such as a motorway, has been created, it is supplied as a block and it is difficult, if not impossible, to split it up according to individual demand. Unlike private goods, where each unit can be sold separately, public goods are often used collectively. This poses challenges in terms of financing and management, as it is not easy to allocate the cost of these goods to individual users, which often reinforces the role of the state or public institutions in the provision and maintenance of these goods.

The Principle of Non-Exclusion in Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Non-exclusion in consumption is a key concept in public goods theory. It refers to the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of preventing individuals from consuming a good, regardless of their contribution to its production or financing. This characteristic is one of the main reasons why private markets may not be efficient in providing certain types of goods. In the context of public goods, non-exclusion means that when the good is available to one person, it is also available to others at no significant additional cost. Take the example of national security: once a country has set up its defence forces, it is virtually impossible to exclude specific citizens from the protection they offer. Similarly, goods such as television broadcasting or public lighting are accessible to everyone within their reach, with no possibility of excluding specific individuals.

This inability to exclude non-payers often leads to the free-rider problem, where some people benefit from the good without contributing to its cost. This can lead to under-provision of the good if the costs are borne only by a subset of the beneficiaries, making provision by the private market inefficient or insufficient. As a result, such goods often require government or community intervention for their provision. The state, using collective funding mechanisms such as taxation, can ensure that these goods are produced and maintained for the benefit of society as a whole, thereby overcoming the challenge posed by non-exclusion.

In the field of public goods economics, there is a category of goods for which consumer exclusion is difficult, if not impossible. This characteristic is particularly relevant for a number of essential elements in our everyday environment.

Take the example of headlights and road signs. A lighthouse, when switched on, provides vital signals to all vessels in its vicinity, without it being possible to restrict its use to certain specific vessels. The same applies to road signs, which provide guidance and safety for all road users, regardless of their individual contribution to the funding of these facilities.

Natural landscapes and fireworks represent another set of goods where non-exclusion is obvious. A picturesque landscape or a fireworks display is accessible to all those in the field of vision, without it being possible to limit their enjoyment to specific individuals. These experiences are shared collectively, and their beauty or spectacle is open to all, regardless of their willingness or ability to pay.

Street lighting and cleanliness are also essential services that benefit the community as a whole. Street lighting improves the safety and practicability of public roads for all residents and visitors, while street cleanliness contributes to public health and the aesthetics of the community space. Once again, it is virtually impossible to exclude individuals from these benefits.

National defence and neighbourhood safety are services that protect the population of a region or a country as a whole. These services benefit everyone, without distinction or exclusion based on individual financial contribution. The safety provided by these services is a common good, essential to collective well-being.

Finally, the quality of air, water and the environment in general are perfect examples of goods that are not only difficult to exclude, but also essential to the health and well-being of all. Environmental degradation affects every individual, and efforts to preserve and improve the environment benefit society as a whole.

These examples underline the crucial role of public and community institutions in the management and provision of these goods. Since the non-excludable nature of these goods makes it difficult to finance and regulate them through private market mechanisms, intervention by the state and other collective organisations is often necessary to ensure their availability and maintenance for the benefit of the community as a whole.

It should be emphasised that the difficulty of excluding consumers from certain goods is not always technical, but can often be economic. In many cases, non-exclusion results not from the technical impossibility of excluding consumers, but rather from the prohibitive cost or economic inefficiency associated with such exclusion. Let's take the example of fireworks. Technically, it would be possible to erect barriers to restrict access to a space from which the show can be seen, thus transforming the fireworks display into a private good. However, implementing such measures would be extremely costly and complex. It would involve high costs for the installation of barriers, surveillance and access management, which would make the venture unprofitable and impractical overall. Furthermore, the very nature of a firework display, designed to be seen from a distance and by a large number of people, makes it economically unwise to privatise it.

The same logic applies to other assets such as public lighting, national security or environmental quality. Even if it were technically possible to devise mechanisms to exclude non-payers, the costs associated with such exclusion would often be prohibitive and would far outweigh the benefits. Moreover, it would run counter to the public interest and the social value that these goods represent. This is why, in such cases, intervention by the State or public authorities is crucial. Through general taxation or other collective funding mechanisms, these goods can be provided more efficiently and equitably, ensuring that they are accessible to the whole population without the prohibitive costs associated with excluding non-payers.

Summary of the Characteristics of Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

This table classifies the different types of goods according to two criteria: the possibility of excluding consumers (Exclusion vs Non-exclusion) and the rivalry or non-rivalry of the goods (Rivalry vs Non-Rivalry).

In the top left-hand quadrant, we have "Pure Private Goods", which are both exclusive and rivalrous. This means that consumers can be prevented from using these goods if they do not buy them, and that the use of these goods by one person prevents their simultaneous use by another. The examples given here are clothes and ice cream, which can only be consumed by one person at a time, and whose consumption by one individual prevents another from using them.

In the top right-hand quadrant, we have "Mixed goods" in the context of non-rivalry. These goods are non-rival, meaning that their consumption by one person does not prevent their consumption by another. However, unlike pure public goods, it is possible to exclude individuals from using them. Examples include natural monopolies and toll roads. Television is also a good example; although a programme can be watched by many people simultaneously without interfering with each other, access to channels can be restricted by subscription.

In the bottom left-hand corner, the table shows "Mixed goods", which are non-exclusive but rivalrous. These goods do not allow easy exclusion of non-payers, but their use by one person may reduce the quantity available to others. Natural resources and fish are classic examples of this type of good. Motorways with traffic jams also illustrate this point: although theoretically open to all, once a motorway becomes congested, each additional car reduces the quality of service (speed, comfort) for others.

Finally, in the bottom right-hand quadrant, we find "pure public goods". These goods are characterised by non-rivalry and non-exclusion. National defence and universal knowledge are examples of pure public goods. They are available to all, and use by one person does not impede use by another. Such goods often present challenges in terms of funding and provision, as the incentives to provide them privately are weak since the beneficiaries cannot be easily excluded and do not compete for their consumption.

This table is a useful tool for understanding the diversity of goods in an economy and the challenges associated with their provision. It also helps to identify where state intervention may be justified to ensure the adequate provision of public goods and to correct market inefficiencies.

The Stowaway Dilemma[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Non-Exclusion and the Stowaway Problem[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Non-exclusion is closely linked to the stowaway problem. This problem arises when individuals benefit from a good or service without contributing to its cost. This is particularly problematic for public goods, where the characteristic of non-excludability means that suppliers cannot prevent people from consuming the good, even if they do not pay for it. In such a context, some individuals may choose not to pay for the good or service in question, knowing that they will still be able to benefit from it thanks to the payments of others. This can lead to under-supply of the good, as suppliers do not have the revenue to cover the costs of producing or maintaining the good. If enough individuals choose not to pay, the good may not be supplied at all, despite being socially beneficial.

This problem is also linked to that of unrevealed preferences, as individuals who choose not to pay for the good do not reveal their true valuation or demand for it. This makes it difficult for suppliers to measure real demand and plan the supply of the good effectively. The difficulty of exclusion therefore leads to market failure, because the price mechanism does not work as it should to ration access to the good and to finance its provision. This is why public goods are often financed by compulsory mechanisms such as taxes, where the individual contribution is not directly linked to consumption, but rather imposed to cover the collective cost of the good.

The free rider problem manifests itself in various situations where an individual or entity benefits from a good or service without contributing to its cost, thereby exploiting the system to its advantage. A classic example is a lighthouse that provides light for navigation. Lighthouses are built to guide all passing ships, ensuring their safety and direction. However, there is no practical way of forcing every ship that benefits from the light of the lighthouse to pay for this service. As a result, some shipowners may choose not to participate in the funding of the lighthouse while benefiting from its services, which may compromise the maintenance and long-term viability of these essential aids to navigation.

In the field of television broadcasting, the situation is similar. Public television channels are financed by licence fees, contributions charged to households that own a television set. Nevertheless, broadcasts are accessible to all, regardless of their status as contributors. So even those who avoid paying the licence fee can watch the programmes, either by devious means or by taking advantage of viewing in public places. This diversion creates a deficit in the funding of public television and raises questions about fairness and financial responsibility. Another example illustrating this problem is the collective immunity conferred by vaccinations. When a majority of the population is vaccinated, the transmission of infectious diseases is considerably reduced, creating an environment in which even the non-vaccinated are less likely to be infected. As a result, people who choose not to vaccinate indirectly benefit from the efforts of those who do, while potentially avoiding the costs and risks associated with vaccination. This can lead to a lower proportion of the population choosing vaccination, which can compromise the effectiveness of herd immunity and public health as a whole.

These examples highlight a central challenge in the provision of public goods: how to ensure that those who benefit from the goods contribute fairly to their creation and maintenance. Solutions to this problem vary, but often involve some form of compulsory funding, such as taxes or charges, to ensure that these essential services remain available for the common good.

The Impact of the Strategic Behaviour of Stowaways[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Game theory is a branch of mathematics and economics that analyses the strategies adopted by individuals in situations where their choices are interdependent. One of the best-known concepts in this field is the prisoner's dilemma, which highlights the difficulties of cooperation between parties with interdependent interests. John Nash, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1994 for his contributions, developed a key concept known as the Nash equilibrium. This equilibrium arises in a game when each player has chosen the best possible strategy, given the choices of the other players. No player then has an incentive to change strategy unilaterally.

In the prisoner's dilemma, two prisoners are faced with a choice: cooperate with the other by remaining silent or betray the other by confessing. The choice to betray may seem rational to one individual because it maximises his personal gain, regardless of the impact of that choice on the other prisoner or on the collective outcome. If both prisoners opt for betrayal, believing they are acting in their own best interests, they both end up worse off than if they had cooperated. This situation is analogous to the stowaway problem in the provision of public goods. Each individual can choose not to contribute to the financing of a public good (betrayal in the prisoner's dilemma), which is rational from an individual point of view if we consider only immediate self-interest. However, if everyone adopts this strategy, the public good will either not be funded or will be underfunded, which is detrimental to all individuals in society. So while the individual choice not to pay may seem rational, it leads to a sub-optimal collective situation where no one benefits from the public good, mirroring the sub-optimal outcome of the prisoner's dilemma. Game theory, and in particular Nash equilibrium, helps to understand these dynamics and to explain why individual incentives can lead to insufficient cooperation, thus justifying the intervention of external mechanisms such as government regulation or incentives to encourage contribution to the financing of public goods.

Nash theory, often illustrated by the Nash equilibrium in game theory, reveals a profound tension between individual and collective interests. According to this theory, individuals acting rationally in pursuit of their own interests can lead to outcomes that are not only sub-optimal but also unfavourable for the group as a whole. This contrasts with Adam Smith's idea of the 'invisible hand', according to which individual actions guided by self-interest can lead to optimal collective welfare. The invisible hand suggests that competitive markets transform selfish actions into socially desirable outcomes, naturally regulating the economy without the need for external intervention. On the other hand, Nash equilibrium shows that in many cases, especially where there are coordination dilemmas or non-zero-sum games, the purely selfish actions of individuals can lead to dead-ends or inefficient outcomes for society.

The example of the prisoner's dilemma, which Nash helped to popularise, is typical: it shows that if each prisoner individually chooses the best strategy for him (betraying the other), the result is worse for both than if they had cooperated. Applied to economics, this theory suggests that without cooperation or regulation, individuals can consume resources inefficiently, pollute without restraint, or fail to contribute to public goods, all of which is detrimental to society as a whole. The importance of the Nash equilibrium is that it highlights the need for coordination and cooperation mechanisms - such as regulations, social norms or contracts - to align individual interests with the collective interest. This may involve government intervention to provide public goods, regulate externalities, or ensure market justice and stability. Nash theory therefore invites us to recognise and manage situations where actions guided by self-interest do not naturally lead to the social optimum.

An Illustrative Example: The Stowaway[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

This table shows a matrix of net gains, which is a tool used in game theory to represent the benefits and costs associated with the different strategies that players can adopt, in this case two neighbours faced with the decision to invest in lighting a road.

In this fictitious example, two neighbours A and B are planning to install street lamps to light a path leading to the village, which is currently in darkness at night. They have a choice between financing the installation of a streetlight or doing nothing. If both neighbours choose to finance a streetlight, the road will be fully lit, giving them each a net welfare gain of 4,000, but at a cost of 3,000 each for the installation, leaving them with a net gain of 1,000 each (4,000 welfare minus 3,000 outlay). If only one neighbour finances a streetlight and the other does nothing, the neighbour who pays for the streetlight has a partial increase in well-being of 2000, but after deducting the cost, ends up with a net loss of -1000 (2000 in well-being minus 3000 in expenditure). The neighbour who doesn't pay gets some benefit from the lighting without having to pay, resulting in a net gain of +2000. If neither of them pays for a streetlight, there is no change in their well-being and therefore no net gain or loss.

What is highlighted here is a classic prisoner's dilemma. The best collective solution would be for the two neighbours to cooperate and each pay for a streetlight, leading to a net gain of +1000 each. However, because of individual incentives, each neighbour would prefer to benefit from the streetlight financed by the other, leading to the temptation not to pay and to act as a free rider. If the two neighbours act according to their individual interests without cooperating, they will end up doing nothing, which is the worst collective outcome with a net gain of 0 for each.

This situation demonstrates the need for cooperation or some form of coordination or intervention, such as mutual agreement or community action, to overcome the free rider problem and achieve the collective optimum.

The Coordination Problem in Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The classical coordination problem is a classic scenario where uncoordinated individual actions lead to a less favourable outcome than that which could be achieved by joint and coordinated action. Indeed, if the two neighbours A and B could reach an agreement to share the costs of lighting, each would benefit from a positive net gain of +1000. This represents the social optimum where the lighting is complete and the benefits shared equally. However, because of the incentive to minimise the importance of lighting and to benefit without paying from the streetlight potentially financed by the other, the two neighbours are faced with a dominant strategy which is inaction. Thus, without coordination, each neighbour chooses to do nothing, as this option seems to them individually the safest way of avoiding costs with no guarantee of reciprocity. The Nash equilibrium of this game is therefore when both neighbours choose not to finance the lighting, even if this leads to a sub-optimal result, with a net gain of 0 for each.

This equilibrium is sub-optimal because it does not maximise the collective welfare of the neighbours. This is the essence of the prisoner's dilemma: although cooperation can lead to the best collective outcome, mutual distrust and uncertainty about each other's actions push individuals to adopt strategies that are detrimental to both themselves and the community. To solve this kind of coordination problem, mechanisms such as contracts, economic incentives, regulation or community or state intervention are often needed to encourage or impose cooperation and ensure that collective well-being is achieved.

The problem of unrevealed preferences is intrinsically linked to the problem of the free rider: individuals have an incentive to conceal their true appreciation of a public good in order to avoid contributing to its funding. If everyone claims not to benefit from or value the good, then no one will voluntarily pay for it, even if the good in question brings them real benefit. This leads to the public good being under-provided, or not provided at all, because funding decisions based on self-reporting do not reflect real demand. The classic solution to this problem is for the state to provide the public good and make contributions to its funding compulsory, often through taxation. This ensures that the good is financed and that all individuals benefit from the public good, regardless of their willingness to reveal their preference or pay voluntarily.

The question of the extent to which everyone should contribute to financing the public good is more complex. Ideally, the contribution should be proportional to the benefit that each individual derives from the public good. However, this requires knowledge of individual preferences, which is difficult because of the problem of unrevealed preferences. One method of solving this problem is to use taxation principles that aim to distribute costs fairly. For example, the benefit rule suggests that those who benefit most from a public good should pay the most for its funding. Capacity to pay is another principle, according to which those with greater economic capacity should contribute more to the financing of public goods.

In practice, it is common to use a combination of general and specific taxes to finance different types of public good. General taxes allow costs to be spread widely across all taxpayers, while specific taxes, such as road tolls, allow the users of certain public goods to be targeted. Whichever method is chosen, the aim is to finance the public good efficiently while maintaining equity among citizens. This may require careful planning and often political adjustments to effectively balance the interests and contributions of all members of society.

The Mixed Good Category[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

A mixed good, also known as a semi-public good or quasi-public good, is a type of good that has characteristics of both private and public goods. These goods may be exclusive, but not necessarily rival in consumption, or vice versa. They may be provided by the market but often with some state intervention to correct market inefficiencies or to ensure that the good is accessible to those who need it.

Issues of Exclusion and Non-Rivality[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Mixed goods can be non-rival in consumption up to a certain point, while allowing the exclusion of non-payers. These goods can be exclusive thanks to pricing or access control mechanisms, but only become rivalrous when capacity is exceeded, leading to congestion or a reduction in the quality of experience for all.

Take the example of a bridge or motorway: as long as traffic flows freely, these infrastructures can be used by an additional vehicle at no significant marginal cost and without adversely affecting the experience of other users. However, when maximum capacity is reached, each additional vehicle begins to reduce the quality of experience for others, for example by causing traffic jams. So rivalry emerges once a certain consumption threshold is reached. The same logic applies to cinemas or swimming pools: until the cinema or swimming pool reaches capacity, an additional spectator or swimmer does not harm the experience of others. But once capacity is reached, each additional person can get in the way, reducing the quality of the experience for others. Television, on the other hand, is generally non-rival in consumption, because the fact that one person is watching a programme does not prevent millions of others from watching it simultaneously. However, access can be exclusionary, for example if access to channels requires a paid subscription.

Mixed goods can be provided either by private companies or by the state, and this decision often depends on political, economic and social considerations, which vary greatly from country to country. Practices for the provision and financing of mixed goods reflect a society's values and priorities, particularly in terms of equity and access. For example, some countries may choose to subsidise services such as public transport or education to ensure wider access, even though these services could technically be offered on a purely private market. Congestion and the quality of service associated with the consumption of these mixed goods raise important questions about how to manage and regulate access to maintain quality. Mechanisms such as dynamic tolling, quotas, reservations or peak pricing are all ways in which providers attempt to regulate usage and prevent or manage congestion. These tools can help to maintain non-rivalry in consumption for as long as possible, while ensuring that costs are covered and access remains equitable.

Education is an eloquent example of a mixed good that embodies the property of exclusion as well as non-rivalry, while being strongly influenced by public policy considerations. In many public education systems around the world, exclusion is practised to some extent: while access to primary and secondary education is often free and universal, access to higher education may be restricted by tuition fees, entrance exams or quotas. These exclusion mechanisms are designed to manage available resources and maintain the quality of education. However, once admitted to a school or university, education becomes a non-rival good: the presence of an extra student in a classroom does not prevent others from learning, until the capacity of the room or the ability of a teacher to manage a large number of students is exceeded.

Education is often provided at less than the cost of production, or even free of charge, because of the societal benefits it generates. By providing equal access to education, governments seek to promote social mobility and ensure that the talents and skills of each individual can be developed for the benefit of society as a whole. This aligns with the notion of education as a fundamental right and an essential resource for personal and economic development. In addition to the redistributive objective, the public provision of education is also justified by the considerable positive externalities it generates. A well-educated individual contributes to society in many ways: increased productivity, civic participation, innovation, and much more. These benefits extend far beyond the individual to society as a whole, which justifies public support for education.

However, when public education becomes congested, for example because of overcrowded classrooms or insufficient resources, the quality of education may suffer, and the redistributive objective may be compromised. Those with more resources may then turn to private institutions, exacerbating inequalities in access to quality education. This can create a two-tier system where the benefits of education are unevenly distributed, which runs counter to the ideal of equality of opportunity. Managing the access and quality of public education while ensuring that it remains inclusive and equitable is a major public policy challenge. This requires adequate funding, strategic planning, and often reforms to ensure that public education can continue to serve its role as a lever of social mobility and a generator of positive externalities for society.

Non-Exclusion and Rivalry: The Associated Challenges[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In the case of a mixed good characterised by non-exclusion and rivalry, we are faced with a situation where it is difficult, if not impossible, to prevent people from accessing a resource, but where the use of this resource by one person reduces the quantity or quality available to others. These goods are often common resources or common property, and are subject to problems of over-exploitation because they are accessible to all but limited in quantity.

Natural resources such as fish stocks in the oceans, grazing land and forests are typical examples. In these cases, the absence of control mechanisms or clearly defined ownership often leads to unregulated use and competition for access, which can result in rapid over-exploitation. This phenomenon is well known as the 'tragedy of the commons', a term popularised by ecologist Garrett Hardin in his influential 1968 article. Hardin pointed out that individuals, acting independently according to their own self-interest, behave in rational ways that are ultimately destructive to the community as a whole, as the shared resource is depleted.

However, Hardin's vision is not without challenge. Elinor Ostrom, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics, has demonstrated through her research that communities can, in fact, effectively manage the commons without outside intervention or privatisation, through community management systems. She has studied how different groups around the world have developed a variety of institutional arrangements to manage rivalry and avoid over-exploitation of common resources.

The key to the sustainable management of mixed assets lies in the ability to establish rules and standards that regulate use and encourage conservation. This can include the introduction of quotas, permits, systems for rotating use, or penalties for those who fail to comply with the rules laid down. Ostrom has highlighted the importance of local participation, monitoring, appropriate sanctions and respect for community rules as essential factors in the successful management of commons. Thus, managing mixed goods with non-exclusion and rivalry requires a nuanced understanding of the social, economic and environmental dynamics at play, as well as a collaborative approach to resolving the dilemmas associated with their use.

The Tragedy of the Commons[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The tragedy of the commons is a phenomenon that occurs when a resource shared by many is over-exploited by individuals acting independently according to their own immediate self-interest, leading to the depletion of that resource to the detriment of all. Let's imagine a pasture open to all the herders in a village. If each farmer tries to maximise his profit by grazing as many of his own animals as possible, the pasture will quickly be overused and its quality will decline, until it is no longer able to regenerate naturally. Eventually, the pasture becomes unusable for the whole community, including the farmers who benefited from it in the first place.

This situation results from unlimited freedom of access and a lack of regulation regarding the use of the resource. Each user has an individual incentive to consume as much of the resource as possible. Since the resource is rivalled, each unit of the resource consumed by one individual is a unit that cannot be consumed by another. When all individuals take from the resource without restraint or coordination, exploitation becomes excessive and the resource is exhausted. The concept, popularised by Garrett Hardin, illustrates a failure of individual rationality where, although each user acts logically to maximise his or her own benefit, the overall result of these actions is detrimental to the group. The tragedy of the commons suggests that without some form of control or management of the resource, the natural selfishness of individuals leads to collective ruin.

In response to this problem, solutions such as privatising the resource (granting private property rights), setting limits on exploitation (quotas), or introducing community management systems have been proposed. Elinor Ostrom has challenged the inevitability of the tragedy of the commons by demonstrating that groups of individuals are capable of creating sustainable management systems for common resources through effective self-management rules and penalties for non-compliance. Management approaches vary considerably, but they share a common recognition of the need to regulate the use of shared resources to avoid depletion and ensure their availability for future generations.

Cooperation between Livestock Farmers to Manage the Commons[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

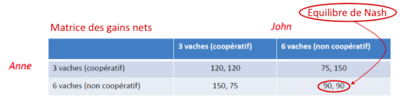

This table shows a matrix of net gains for two farmers, Anne and John, who have to decide how many cows to graze on a common field. The Nash equilibrium is shown in the matrix, highlighting the result where both Anne and John choose to graze six cows, which is a non-cooperative strategy.

In this example, the Nash equilibrium occurs when the two farmers act in a non-cooperative manner, maximising their own immediate gain without taking into account the effect of their action on the other. If Anne and John both decide to graze three cows (the cooperative strategy), the field can support this number without degrading, and they both benefit from a net gain of 120. However, if one of them decides to graze six cows while the other stays at three, the non-cooperative one gains more at the expense of the other. For example, if Anne grazes three cows and John grazes six, Anne gets a net gain of 75 while John gets 150.

The individual incentive to maximise personal profits leads both farmers to choose the non-cooperative strategy of grazing six cows, resulting in a net gain of 90 for each. This situation is sub-optimal compared with cooperation, but it is the stable equilibrium of the strategy because neither farmer has any incentive to deviate from this strategy as long as the other does not change. The consequence of this non-cooperative joint action is that the field is over-exploited, the grass cannot renew itself, which reduces the quality of the field for all the farmers.

This situation illustrates the "tragedy of the commons", where individuals, acting independently and rationally according to their own self-interest, end up depleting a shared resource, despite the fact that this goes against the long-term interests of the community, including their own. Responsible' management of the common field is not attractive to individuals because the benefit of such management is minimal, especially if other farmers do not behave responsibly. The direct consequence is a degradation of the shared resource to the detriment of all.

[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The problem of fishing zones is a perfect illustration of the complexity of managing common property, which is subject to rivalry and the difficulty of exclusion. The oceans are vast and it is often technically or economically impractical to exclude new players from exploiting fishing grounds. However, the fish resource, although apparently abundant, is in reality limited and extremely sensitive to overfishing.

When too many boats fish in a given area, they compete for a dwindling resource, which is a classic case of rivalry. Even if every fisherman understands that it would be beneficial in the long term to limit catches to allow fish stocks to regenerate, there is an immediate incentive to fish as much as possible. This is due to the risk that if one fisherman doesn't catch the fish, another will. This logic leads to overexploitation of fish stocks, which can lead to the collapse of fish populations, damaging the marine ecosystem and the fishing communities that depend on these resources for their survival.

This is where the need for regulation by a public authority comes in. Such regulations can include fishing quotas, which limit the amount of fish that a boat can catch, closed seasons during which fishing is prohibited to allow fish to reproduce, or regulations that determine the types of fishing gear authorised in order to reduce the accidental capture of non-target species.

Implementing these regulations requires international cooperation, as fish know no borders and fishing zones can span several national jurisdictions. International organisations and fisheries agreements therefore play a crucial role in coordinating fisheries conservation and management efforts. In addition, conservation measures must be accompanied by monitoring and enforcement to be effective, which can be difficult on the high seas.

Ultimately, regulating fishing zones is a complex issue that requires a balanced approach to protect the livelihoods of fishing communities while preserving the sustainability of marine ecosystems for future generations.

Regulatory Mechanisms and their Importance[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

When natural resources, such as fishing grounds, are shared between several countries, the need for cross-border management and regulation becomes particularly acute. The oceans know no borders, and fish stocks migrate and mix across international waters and the exclusive economic zones of different countries. In such contexts, unilateral action is not enough to ensure the long-term sustainability of fish stocks, and international cooperation becomes imperative.

Articles such as The Economist's 2005 article, The tragedy of the commons, and the contemporary challenges of managing common pool resources highlight the difficulty of reaching agreements and taking collective action. To resolve these problems, supranational bodies such as the United Nations and its various agencies, or regional fisheries management organisations, are often called upon to play a coordinating and regulatory role. These organisations can help to negotiate international treaties that set fishing quotas, fishing seasons and conservation measures, and which are binding on the signatory countries.

These issues of managing shared natural resources also have parallels in climate change, particularly with the impact of CO2 emissions on the atmosphere. The atmosphere is a global commons, and a country's CO2 emissions affect the global climate. International agreements such as the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2009 Copenhagen Accord are therefore attempts to regulate these emissions collectively. These agreements aim to establish legally binding frameworks for signatory countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and thereby limit global warming.

However, such agreements face challenges similar to those of the "tragedy of the commons", where each country has an incentive to maximise its economic development and minimise the costs of reducing emissions, while benefiting from the reduction efforts undertaken by other countries. This is why the success of these agreements depends not only on the commitment of developed countries, which are historically the biggest emitters, but also on the involvement of developing countries, which are the biggest sources of emissions growth. Global climate governance therefore depends on the ability of countries to look beyond their immediate interests and work together for the long-term common good.

The Tragedy of the Commons: Comparing Private and Social Costs[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The tragedy of the commons highlights a fundamental mismatch between the private and social costs of using shared resources. In this scenario, the private cost is the personal cost that an individual or company incurs when using a common resource. For example, for a fisherman, this could be the cost of petrol for his boat, the time spent fishing, or the wear and tear on his equipment. The social cost, on the other hand, includes all the private costs plus the external costs that the individual's actions impose on society - in this case, the reduction in fish stocks available to others as a result of overfishing.

In a tragedy of the commons situation, individuals or companies primarily consider their private costs when making decisions about how much to take from the common resource. This leads to overuse of the resource, because social costs are not taken into account in their individual decision-making. If a fisherman can increase his immediate gains by fishing more, he has little incentive to hold back, even though overfishing reduces fish stocks and harms the fishing community as a whole in the long term.

The consequence is that each user of the common resource, by pursuing his own interests, contributes to a situation where the resource is exploited to such an extent that it becomes less available or even depleted for everyone, including those who have contributed to its over-exploitation. End-users therefore find themselves in a worse position than if everyone had limited their consumption of the resource. This demonstrates a conflict between short-term optimality for individuals and long-term optimality for the group.

The traditional solution to the tragedy of the commons is regulation, which can take the form of clearly defined property rights, quotas, taxes or legal standards, encouraging users to take account of the social costs of their actions. These regulations are designed to limit the use of the common resource to a sustainable level, thereby bringing private costs into line with social costs and avoiding the depletion of the resource.

This economic graph illustrates the concept of the tragedy of the commons applied to fishing, showing the difference between private and social marginal costs and how this affects the quantity of fish caught.

In the graph, the vertical axis represents the price of fish, while the horizontal axis represents the quantity of fish. The vertical line labelled "Private/social profit = Demand" reflects the demand for fish; it indicates how much consumers are prepared to pay for each quantity of fish. Demand is considered to be both private benefit (what fishermen receive for their fish) and social benefit (the value of fish to society).

The green line, labelled "Private cm", represents the marginal private cost, which is the cost borne by the fishermen for each additional unit of fish caught. This cost includes fuel, depreciation of the boat, labour, etc. At the intersection of the demand line and the private marginal cost, we find the market quantity and the private price , which are the quantity and price that would be realised in a market without intervention where fishermen consider only their private costs.

The red line, labelled "Social cm", represents the marginal social cost, which includes both private costs and external costs (such as ecosystem degradation, loss of biodiversity, and impacts on fishing communities over the long term). When these external costs are taken into account, the marginal social cost is higher than the marginal private cost. The intersection of the demand line with the social marginal cost gives the socially optimal quantity and the social price PSocial∗. This quantity is lower than the market quantity, reflecting the fact that once external costs are taken into account, the socially optimal quantity of fishing is lower to avoid overfishing.

This graph shows that, without regulation, fishermen are likely to fish a quantity that is greater than the socially optimal quantity , leading to overexploitation of the resource. Regulation, such as the imposition of fishing quotas or other management mechanisms, is needed to reduce the amount fished from to , thereby minimising social costs and preserving the fish resource for future generations.

Strategies for Allocating Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Determining the Optimal Supply of a Public Good[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The provision of a public good poses unique challenges compared to the provision of a private good. For a private good, the market generally determines both the price and the quantity of goods consumed. Individual consumers purchase different quantities of a private good based on their own assessment of the marginal utility of the good and their willingness to pay, which is reflected in the market demand curve. Market equilibrium occurs at the point where the demand curve crosses the supply curve, indicating the optimal quantity of the private good that will be produced and consumed at the market price.

For a public good, however, the process is more complex. Since public goods are characterised by non-rivalry, the consumption of the good by one person does not prevent its consumption by another. This means that the same quantity of the good is available to all individuals, regardless of the amount they pay individually. The question then becomes not how much each person will consume for a given price, but rather how much each person should contribute for the given quantity of the public good.

The efficient provision of a public good requires that the sum of individual marginal benefits, which are the amounts each person is willing to pay for an additional unit of the good, is equal to the marginal cost of producing the good. In other words, the public good should be produced to the point where the cost of providing an additional unit is exactly equal to the total amount that individuals are willing to pay for that additional unit.

However, determining willingness to pay for a public good is difficult because individuals have an incentive to under-report their true willingness to pay in order to benefit from the good without contributing to its cost (the free rider problem). For this reason, individual contributions to the financing of public goods are often determined through taxes or other compulsory mechanisms, rather than through voluntary payments. In the end, the decision on how much public good to provide and how to finance it is usually taken by the government or other public authority, taking into account production costs, marginal benefits to society, and equity considerations.

Understanding Individual and Aggregate Demand for Private Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

For a private good, individual demand is the quantity of that good that a person is willing to buy at different prices. Aggregate demand, or market demand, is the sum of individual demand for the good at each price. It represents the total quantity that all consumers are prepared to buy at each price level.

The process of aggregating individual demands to form market demand is relatively simple for private goods:

- Establishing individual demand curves: Each consumer has a demand curve that reflects their willingness to pay based on their marginal utility for the good. This curve shows how many units of the good the consumer would buy at different prices.

- Horizontal aggregation: Market demand is obtained by horizontally summing the quantities of all consumers at each price level. This means that for a given price, we add up the quantities that each consumer is prepared to buy to obtain the total quantity demanded on the market at that price.

- Establishment of the market demand curve: The aggregated market demand curve is then drawn by taking into account the total quantities demanded at each price. This curve generally has a negative slope, showing that the quantity demanded increases as the price decreases.

Market equilibrium for a private good is reached at the point where the demand curve crosses the market supply curve. At this point, the number of units that consumers wish to buy corresponds to the number of units that producers wish to sell, and the price at which these two quantities equal each other is the equilibrium price.

This market mechanism ensures that resources are allocated efficiently: private goods are produced and consumed in quantities that maximise consumer welfare, as long as markets are competitive and there are no market failures such as externalities or imperfect information.

This graph illustrates how individual demands are aggregated to form the market demand for a private good. We have two separate graphs representing two different consumers, each with its own demand curve, indicated by D1 and D2. Each consumer has a point on his or her demand curve where the equilibrium market price, represented by the vertical axis P, corresponds to the quantity he or she is willing to consume, represented by q1 and q2 respectively.

The third graph combines these two individual demands. The market demand curve D is the horizontal sum of the quantities q1 and q2 that the two consumers are prepared to buy at the equilibrium market price. The green horizontal line, labelled Cm=0, indicates that the marginal cost of producing the good is zero. In reality, this would be rare for a private good, but it can be used to illustrate a hypothetical scenario or public good where the marginal cost of supplying the good to an additional consumer is zero.

What is crucial to understand here is that, although the equilibrium price is the same for all consumers in the market, the quantity consumed can vary from one individual to another depending on their personal preferences and willingness to pay. This variation is represented by the different quantities q1 and q2 on the individual demand curves. Market demand reflects the sum of all individual demands at that price.

The graph below, with the dotted curves, appears to show the aggregation of these individual demands to form the market demand curve. The horizontal aggregation is a graphical representation of the sum of the quantities demanded by all individuals at each price level to obtain the total market demand curve. This market demand curve is then used to determine the total quantity of the good that will be consumed at the equilibrium price in the overall market.

Analysis of Individual and Aggregate Demand for Public Goods[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

For a public good, the logic of individual and aggregate demand differs considerably from that of private goods because of the non-rivalry in consumption. For a public good, each individual consumes the same quantity of the good, because consumption by one person does not prevent or reduce consumption by another. For example, once a lighthouse has been built, all boats sailing nearby benefit from its light, regardless of how much they have paid for this service.

The price that each individual pays for this public good can vary considerably and does not necessarily correspond to the marginal cost of providing the good, because the marginal cost of providing the good to an additional person is often zero or very low. If we were to apply the logic of the private market, where prices are set equal to the marginal cost (Cm), we might not supply the public good at all or in insufficient quantity, because the fixed costs of producing a public good are generally high and would not be covered if each user only paid the marginal cost.

Thus, to ensure optimal provision of a public good, it is often necessary for each individual's contribution to be determined by means other than the market. This contribution can be established by taxation, where everyone pays an amount calculated not on the basis of personal use, but rather on the basis of ability to pay, the perceived value of the good, or by other considerations of equity and efficiency.

The aim is for the sum of the contributions to cover the total cost of providing the good. To achieve this, the government or public body providing the good must assess the total willingness to pay for the good and compare it with the cost of providing it. If the sum of the values that individuals place on the good (their willingness to pay) is greater than the cost of production, the good should be provided. The exact method of allocating these costs among individuals can be complex and depends on many factors, including political and social considerations.

These economic graphs describe the demand for a public good by two individuals, as well as aggregate demand. In the first two graphs, we see the individual demands D1 and D2 for two individuals, together with the marginal benefits (Bm) they derive from different quantities of the public good. The marginal benefit is represented on the vertical axis and the quantity of the public good on the horizontal axis.

For each individual, the marginal benefit decreases as the quantity of the good consumed increases, which is a standard representation of the decrease in marginal benefit. The price equal to marginal cost (Price=Cm) is indicated by a horizontal dotted line. For a public good, the marginal cost of supplying an additional consumer is often very low, or even zero, after the good has been produced.

In the third graph, we see the aggregate demand for the public good, which is simply the vertical sum of the individual demands at each quantity level. The vertical sum is used because, unlike private goods, each individual can consume the same quantity of the public good without reducing the quantity available to others. The collective marginal cost is indicated by the horizontal green line (Cm) and is marked as zero, which is typical for many public goods.

What the graph suggests is that to achieve efficiency in the provision of a public good, the sum of marginal benefits (the vertical sums of individuals' willingness to pay at each quantity level) should equal the marginal cost of producing the good. Since the marginal cost is very low or zero, this means that the quantity supplied should be where aggregate demand intersects the marginal cost, which is the maximum total marginal benefit.

However, the graph poses a question in the form of Cm=Price? with a value of zero, which raises the problem of how to finance the good. If the marginal cost is zero, but the total cost of production is not covered, we would have to find a way of financing this cost. This could involve collective financing mechanisms, such as taxes or public contributions, which are not directly linked to individual consumption but rather to each individual's ability to pay or perceived value of the good.

Practical Case Studies[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

For example, if the cost of a given street cleaning service is 100 and John is prepared to pay 20, James 30 and Paul 50, we have the optimal quantity of the public good, because the sum of the willingness-to-pay equals the cost of producing the service. However, a private road company could not finance this service by charging everyone according to their willingness to pay, because of the free rider problem and unrevealed preferences. The State, on the other hand, could assess the benefits of the road service and, once the optimum quantity had been established, use its power of coercion to force citizens to share the financing. (But how can the benefits be assessed and the burden shared as best as possible between citizens if the State itself does not know everyone's preferences? → very tricky questions...)

This example highlights the challenges associated with financing public goods such as road service. In this scenario, the sum of John, James, and Paul's willingness to pay is equal to the cost of producing the service, indicating that the provision of this service is socially optimal. However, a private company cannot easily finance this service by charging each individual according to their willingness to pay, because each individual has an incentive to hide their true willingness to pay in order to avoid contributing to the cost (the free rider problem) or to pay less than their true valuation of the service (unrevealed preferences).

The State, which has the power to levy taxes, can finance this service by distributing the cost among all citizens. It can do this by estimating the total value that the road service brings to the community and using tax mechanisms to collect the necessary funds. However, assessing individual benefits and distributing the tax burden fairly are not simple tasks. The State must take into account not only individuals' ability to pay, but also the indirect benefits and positive externalities that the road service could generate, such as improved public hygiene and greater transport efficiency, which benefit the community as a whole.

To assess these benefits and apportion the costs fairly, the State can use different methods:

- Indirect evaluations: Use economic and social indicators to estimate the value of the service to citizens.

- General taxation: Fund the service through general taxation, where taxes are levied on the basis of ability to pay rather than direct use of the service.

- Surveys and evaluations: Conduct surveys of citizens to gather data on their willingness to pay.

- Shared costs: Allocate costs among residents on the basis of certain criteria, such as road use, property ownership or location.

It is important to note that these methods have their own limitations and may require a compromise between efficiency, equity and practicality. The key is to find a balance that ensures the continued provision of the service while maintaining the consent and confidence of citizens in how the funds are used.

Fundamentals of Cost-Benefit Analysis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Cost-benefit analysis is a methodical approach to assessing the economic viability of a public project by comparing the total costs with the total benefits to society. This enables decision-makers to determine whether the expected benefits of a public good justify the expenditure.

In the case of public goods, benefits and costs are not always directly reflected in market prices, as these goods are not generally bought or sold in a traditional market. To estimate the social value of these goods, economists and planners use various methods:

- Contingent valuation: This method involves asking people directly how much they would be prepared to pay for a public good, or how much they would be willing to receive to give up that good. For example, how much would people be prepared to pay to conserve a forest or improve road safety? # Hedonic pricing: This method evaluates the impact of public goods on the prices of private goods. For example, the value of a forest can be partially deducted from the premium that people are prepared to pay for properties near that forest.

- Replacement or restoration cost: To assess the value of a public good, we can calculate how much it would cost to replace or restore it if it were to be lost. For example, how much would it cost to rebuild an embassy or restore a degraded area of biodiversity? # Opportunity cost: We can also look at what society foregoes by allocating resources to the provision of a public good. For example, if funds are used to build a zoo, what other public facilities or services have not been funded instead?

- Statistical value of a life approach: To estimate the value of safer roads, economists sometimes use the notion of the statistical value of a life, which reflects the amount of money society is prepared to spend to reduce the risk of death.

These methods have limitations and may be subject to bias, but they provide frameworks for attempting to assess non-market benefits and costs. The results of these evaluations are crucial to public policy decision-making, particularly in deciding whether a public good should be provided and on what scale. Ultimately, although cost-benefit analysis can help inform decisions, the final choices often also involve value judgements and political considerations.

CBA is a complex assessment tool that often requires subjective judgements to be made, particularly when weighing economic benefits against social and environmental costs. In the example of a hydroelectric dam, benefits may include the generation of renewable energy, water regulation to prevent flooding, and the creation of economic opportunities such as improved infrastructure and tourism. These benefits are often quantifiable in monetary terms and can be compared to the direct costs of building and maintaining the dam. However, the costs to local residents - such as the displacement of communities, the loss of agricultural land, and changes in local lifestyles - and the impacts on biodiversity - such as the disruption of aquatic ecosystems and the modification of natural habitats - require a more subjective assessment. How, for example, can we assess the loss of cultural heritage or the impact on endemic species that could be threatened by the construction of the dam?

The contingent valuation method can be used to ask stakeholders how much they would be prepared to pay to preserve their way of life or the environment, but these assessments are subjective and may not fully capture the intrinsic value of non-economic losses. The value given to each factor varies between stakeholders and decision-makers, and can be influenced by political, economic and ethical considerations. Final decisions may therefore vary according to society's values and priorities at any given time. This underlines the importance of a transparent and inclusive decision-making process, where all voices are heard and impacts are carefully considered and balanced. It is also essential to consider alternative solutions and carry out sensitivity analyses to understand how different assumptions influence the results of the cost-benefit analysis.

Case Study: Cost-Benefit Analysis of a Bridge Project[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The cost-benefit analysis for the construction of a bridge over a river must take into account various economic, social and environmental implications. The benefits of this project can be manifold. In monetary terms, if the bridge is tolled, it could generate substantial revenue depending on the traffic it attracts. This income is not limited solely to toll charges, but also extends to the surplus that motorists would be willing to pay for the advantages that the bridge offers in terms of time savings and comfort compared with alternative routes. In addition, the presence of the bridge can have a significant positive impact on local tourism, as areas that were previously difficult to access may become more attractive to visitors, boosting the local economy. Reducing congestion on other roads may also lead to savings in time and money for motorists, which is another indirect economic benefit.

However, there would also be costs associated with the project. In monetary terms, the immediate costs would include expenditure on construction, such as materials, labour and project management. If construction is financed through increased taxation, this could lead to a loss of economic efficiency as taxes can disrupt the optimal allocation of resources in the market. In addition, there are negative externalities that need to be considered, such as the potential impact on tourism businesses in other regions that could lose revenue, or on ferry services that would be less used or become obsolete. The environmental consequences should not be underestimated either, as the construction of a bridge can alter landscapes, disrupt local ecosystems, affect wildlife and impact on the quality of life of local residents.

All of these factors must be carefully assessed to determine whether the overall benefits justify the associated costs. The difficulty lies in monetising the non-economic benefits and costs, which often requires indirect valuation approaches and can be open to debate. The impact on the environment, for example, may require compensation or mitigation measures that need to be properly assessed and funded.

The final decision regarding the construction of the bridge must then be taken taking into account not only economic calculations, but also social and environmental values. It will involve a trade-off between the needs of economic development and the preservation of the environment and social well-being. Ultimately, it's about making a decision that maximises collective well-being while minimising negative impacts, a challenge that requires careful thought, informed trade-offs and strategic planning.

Assessing the Value of a Lifetime in Public Projects[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Political decision-makers are often faced with difficult decisions when it comes to improving safety in various areas of public life. These improvements, whether they concern the workplace, road traffic or leisure activities, generally involve costs that have to be weighed up against the benefits, particularly in terms of lives potentially saved. The ethical and practical complexity of these situations lies in the need to assign a value to human life, which is both a sensitive and controversial task.

One method of assessing the value of a life is the human capital approach, which measures the economic value of a person in terms of their potential future contribution to the economy, often based on current or expected future income. This method is used in some legal systems, such as courts in the United States, to calculate compensatory damages in the event of death. However, this approach raises significant ethical issues relating to fairness: it can lead to a situation where the lives of people with low incomes or little education are considered to be of less value than those of people with higher incomes or higher levels of education.

Another approach is safety spending, which looks at what people are prepared to pay for additional safety features, such as an airbag, ABS brakes on a car or a fire extinguisher in a house. This reflects a willingness to pay to reduce the risk of injury or death. However, this assumes that people have a clear understanding of the level of risk reduced by such expenditure and that everyone has the same financial means to invest in safety.

The statistical value of a life approach takes into account the risk premium that workers demand to accept a riskier job. These premiums can be used to estimate the value that society places on statistical reductions in the risk of death. This method is widely used to guide public policy, as it is based on observable choices in the labour market.

These different approaches all have limitations and moral implications. For example, the statistical value of a life may vary according to age, socio-economic status or other factors, which raises questions of fairness. Furthermore, no method can fully capture the intrinsic value of human life and the emotional, social and cultural consequences of losing a loved one.

In practice, decision-makers can combine several methods to arrive at a more balanced estimate of the value of a life in the context of public policy decisions. They must also take account of society's ethical values and ensure that the measures taken do not discriminate against certain groups of people. Public participation and debate are essential to ensure that these decisions reflect the values of the community as a whole.

Time Implications in Cost-Benefit Analysis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]