« The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (41 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 1 : | Ligne 1 : | ||

{{Translations | {{Translations | ||

| | | fr = Aux origines de la chute de la République de Weimar | ||

| es = Los orígenes de la caída de la República de Weimar | | es = Los orígenes de la caída de la República de Weimar | ||

| it = Le origini della caduta della Repubblica di Weimar | | it = Le origini della caduta della Repubblica di Weimar | ||

| Ligne 11 : | Ligne 11 : | ||

{{hidden | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to Political Science]] | |[[Introduction to Political Science]] | ||

|[[ | |[[Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory]] ● [[The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic]] ● [[Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory]] ● [[The notion of "concept" in social sciences]] ● [[History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts]] ● [[Marxism and Structuralism]] ● [[Functionalism and Systemism]] ● [[Interactionism and Constructivism]] ● [[The theories of political anthropology]] ● [[The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas]] ● [[Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science]] ● [[An analytical approach to institutions in political science]] ● [[The study of ideas and ideologies in political science]] ● [[Theories of war in political science]] ● [[The War: Concepts and Evolutions]] ● [[The reason of State]] ● [[State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance]] ● [[Theories of violence in political science]] ● [[Welfare State and Biopower]] ● [[Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes]] ● [[Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences]] ● [[The system of government in democracies]] ● [[Morphology of contestations]] ● [[Action in Political Theory]] ● [[Introduction to Swiss politics]] ● [[Introduction to political behaviour]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation]] ● [[Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations]] ● [[Introduction to Political Theory]] | ||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |headerstyle=background:#ffffff | ||

|style=text-align:center; | |style=text-align:center; | ||

}} | }} | ||

The democratic experiment of the Weimar Republic, which lasted just over a decade, was marked by intense social tensions and notorious political instability. We aim to unravel the process by which the Nazis peacefully seized power, triggering the advent of the Third Reich. This radical change led to Hitler's rapid suspension of individual and political freedoms, which paved the way for the extermination of the Jews and the declaration of the Second World War. It was a pivotal period in history when the inability to form stable governments legitimised Hitler, his political programme and his extreme actions. | |||

In our study of this subject, we will approach the question in a way that is both comprehensive and causal. Institutionalists tend to ask 'big questions', seeking to understand social and political structures as a whole. On the other hand, rational choice theory, with its rigorous methodological approach, selects its object of study with particular precision. | |||

Several schools of thought, such as constructivism, maintain that it is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish between cause and effect in the social sciences clearly. Constructivists argue that the conflicts inherent in social relations are complex to account for because of their inherently subjective and changeable nature. The Marxist perspective, on the other hand, is reluctant to identify direct causal relationships. This methodology conceives of the world through a historical dialectic in which each factor can influence an outcome, and this outcome in turn affects the initial variable. In this framework, cause and effect are seen as interdependent and mutually influential rather than as separate and distinct elements. | |||

The central question of our study is: what factors contributed to the fall of the Parliamentary Weimar Republic and the rise to power of Adolf Hitler? What specific factors can explain this major historical phenomenon? Can the various factors be attributed to individual responsibility, economic circumstances such as the drastic rise in unemployment, dysfunctional political institutions, or to the irresistible appeal of a charismatic leader like Adolf Hitler? By examining these different dimensions, we seek to develop a nuanced understanding of this critical period in German and world history. | |||

The period in question, nestled at the heart of an era of revolutions, such as that in Russia and major conflicts, is of intrinsic interest. The period was also marked by major issues relating to industrialisation and the unification of nations such as Italy and Germany. The inter-war period in Germany was particularly crucial, with the Second World War looming on the horizon. | |||

In terms of democratic theory, Germany inaugurated its first democratic experiment after the First World War. This period is rich in key concepts related to democracy, such as electoral systems, the role of institutions, political parties and ideologies. Consequently, studying the fall of the Weimar Republic offers valuable insights into the fragility of democracy in a tumultuous socio-political environment. | |||

= | = Describing the Weimar Republic = | ||

== | == What was the Weimar Republic? == | ||

The Weimar Republic was the name given to the political order in force in Germany from 1919 to 1933. This regime was established following Germany's defeat in the First World War and the German Revolution of 1918-1919. This period marked a significant break with the former imperial regime, establishing a parliamentary and democratic form of government in Germany profoundly transformed by the tumult of war and revolution. | |||

The Weimar Republic was established following Germany's defeat in the First World War and the German Revolution of 1918-1919. Germany's defeat in the First World War led to a major political and social crisis. Kaiser Wilhelm II was forced to abdicate in November 1918, and a republic was proclaimed. However, the new government, led by Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), faced many challenges, including revolutionary unrest on the far left and widespread dissatisfaction with the Treaty of Versailles. In addition, the German Revolution of 1918-1919 was a period of political and social upheaval in Germany. The revolution began in November 1918 with a series of strikes and demonstrations against the war and culminated in the abolition of the monarchy and the creation of the Weimar Republic. The Weimar Republic was therefore established against a backdrop of major political upheaval and serious socio-economic challenges. | |||

The German Revolution of 1918-1919 resulted from a series of revolts and actions, notably communist, that led to the fall of the German Empire and its semi-parliamentary monarchy. The starting point of this revolution is often associated with the mutiny of sailors in the Imperial Fleet at Kiel. Faced with Germany's imminent defeat in the First World War, the German military high command had envisaged a final naval offensive against the British navy, which would have been essentially suicidal. The sailors of Kiel, refusing to sacrifice their lives needlessly, mutinied on 3 November 1918. This revolt spread rapidly and was supported by the German working class, which, tired of war, deprivation and oppression, rallied to their demands. Demonstrations and strikes soon broke out across the country, forcing the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II and leading to the proclamation of the Weimar Republic. | |||

During the German Revolution of 1918-1919, the German working class and socialist movement were divided into different factions, considerably influencing the course of events. On the one hand, there was the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which advocated a transition to parliamentary democracy. The SPD, led by Friedrich Ebert and Philipp Scheidemann among others, was the largest party at the end of the First World War and sought to establish a democratic republic to replace the old imperial regime. On the other side was the USPD (Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany), which had a more left-wing orientation. The USPD, founded in 1917, criticised the SPD for its cooperation with conservative forces during the war and aspired to a socialist republic rather than a simple parliamentary democracy. In addition, there was the Spartakus League, a revolutionary communist group led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, which aspired to a socialist revolution similar to that which had taken place in Russia a year earlier. However, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were critical of the authoritarian approach adopted by the Bolsheviks in Russia. This division among the forces of the left contributed to the failure of the revolution to establish a socialist republic, ultimately leading to the establishment of the Weimar Republic. | |||

Following the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and against a backdrop of revolutionary unrest, Friedrich Ebert, then leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the last Chancellor of the German Empire, entered into a pact with the German military leadership known as the "Ebert-Groener Pact". Wilhelm Groener, General Ludendorff's successor as First Quartermaster General, agreed to use the army to help maintain order and support the new republican government. In exchange, Ebert promised not to call into question the army's privileges or officers' status. This pact temporarily stabilised the situation in Germany. Still, it also laid the foundations for a problematic relationship between the new republic and the army, many of whose members were deeply conservative and unenthusiastic about the idea of a republican and democratic Germany. This situation ultimately contributed to the fragility of the Weimar Republic and its eventual downfall in the face of the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party. | |||

Following the end of the German Revolution and the temporary stabilisation of the country, a National Constituent Assembly was convened to draft a new constitution for Germany. Due to the instability in Berlin, the Assembly met in Weimar, a town in the state of Thuringia. This meeting took place from February to August 1919. The resulting constitution, known as the Weimar Constitution, was adopted on 11 August 1919 and came into force on 14 August of the same year. It marked the birth of a parliamentary democratic republic in Germany, ending the imperial monarchy. The Weimar Constitution established several democratic principles, including universal suffrage for men and women over the age of 20, freedom of speech, press and association, and the protection of individual rights. However, it also included a provision, Article 48, which allowed the President of the Republic to assume extraordinary powers in the event of a national emergency, a measure that Adolf Hitler later used to consolidate his power. | |||

In the Weimar Republic, the political system was organised in such a way that the President was elected by direct universal suffrage for a seven-year term. The President's role was primarily representative, but he also had significant powers under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed him to govern by decree in the event of a national emergency. However, the Chancellor exercised day-to-day executive power, who the President appointed but also needed the support of a majority of the Reichstag (the lower house of the German parliament) to govern effectively. This was intended to ensure a certain balance of power within the German political system. However, practice has revealed weaknesses in this system. The need for the Chancellor to have the support of a majority in the Reichstag led to governments that were often unstable and short-lived, as it was difficult to maintain a coherent majority among the many political parties in the Reichstag. In addition, the President's use of Article 48 to rule by decree ultimately contributed to the erosion of democracy in Germany and the rise of Adolf Hitler. | |||

The Weimar Republic was marked by great political instability, with twenty separate governments in its fourteen years of existence, from 1919 to 1933. These governments were often short-lived due to political divisions within the Reichstag, the lower house of the German parliament. As laid down in the Weimar Constitution, the proportional representation system resulted in a fragmented political landscape, with many political parties and no single party capable of securing a clear majority. This made it difficult to form stable and lasting coalition governments. In addition, Germany's difficult economic situation in the 1920s and 1930s, marked by hyperinflation, unemployment and the global economic crisis, added to social and political tensions and contributed to the country's political instability. These factors weakened the Weimar Republic and ultimately contributed to the rise of the Nazi party and Adolf Hitler, who was able to exploit public frustrations and political divisions to consolidate his power. | |||

The appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg on 30 January 1933 marked a decisive turning point in German history. It led to the advent of the Third Reich. Although the Nazi Party failed to win an absolute majority in the November 1932 elections, Hitler persuaded Hindenburg to appoint him Chancellor in a coalition government. Once in power, Hitler and the Nazi party moved quickly to consolidate their control and establish an authoritarian regime. In February 1933, following the Reichstag fire, Hitler persuaded Hindenburg to issue an emergency decree "For the Protection of the People and the State", which suspended many civil liberties and gave the Nazis sweeping powers to repress their political opponents. The transition from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich was thus marked by a rapid erosion of democracy and human rights in Germany. This radical change ultimately led to the Second World War and the horrors of the Holocaust. | |||

== | == Factors contributing to Hitler's rise to power == | ||

Although Hitler's seizure of power was peaceful and in accordance with the legal provisions of the Weimar Republic, the context in which this transition took place was far from ideally democratic. President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor on 30 January 1933, hoping that by incorporating Hitler into a coalition government, he would be able to moderate the Nazi party and avoid a possible violent seizure of power. In doing so, Hindenburg respected the constitutional provisions of the time, although the Nazi party did not have an absolute majority in the Reichstag. However, although this appointment respected the legal framework of the Weimar Republic, it took place in a climate of intense political tension and violence against the Nazi party's political opponents. Moreover, once in power, Hitler moved swiftly to dismantle existing democratic structures and establish a totalitarian regime. After the Reichstag fire in February 1933, Hitler convinced Hindenburg to issue an emergency decree that suspended many civil liberties and authorised massive repression of political opponents. So, although Hitler's transition of power was formally peaceful and legal, to describe it as democratic would be misleading. This transition took place in a climate of political violence and rapidly led to the collapse of democracy in Germany. | |||

The fall of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany coincided with January 1933. President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler to the post on 30 January 1933, marking the end of the Weimar Republic. In the following weeks and months, Hitler and his government worked rapidly to consolidate their power and transform Germany into a totalitarian state. The decree of 28 February 1933, which followed the burning of the Reichstag, suspended many civil liberties. Subsequently, the law of 23 March 1933, known as the "Full Powers Act", gave Hitler the right to legislate without parliamentary approval. These measures marked the beginning of the Third Reich and the beginning of Nazi Germany. | |||

=== | === The process of transferring and consolidating power === | ||

The government of the Weimar Republic was primarily led by a coalition known as the "Weimar coalition", which included the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Catholic Centre Party and the German Democratic Party. Although representing different ideologies and segments of society, these parties shared a commitment to parliamentary democracy and sought to govern in a moderate manner. However, this coalition was constantly threatened by internal conflicts, ideological differences, and external tensions and pressures, particularly from political parties on the right and left that were hostile to the Weimar Republic. When Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, he exploited these weaknesses and worked quickly to dismantle the Weimar coalition and consolidate the power of the Nazi party. Through a series of legal and extra-legal measures, including violence and intimidation against political opponents, Hitler transformed the Weimar Republic into a totalitarian state under the control of the Nazi party. | |||

The functioning of the Weimar Republic was based in part on two key pacts: | |||

# | # The government-military pact: There was a tacit agreement between the government of the Weimar Republic and the army. The government agreed to preserve the status and privileges of the army, and in exchange the army undertook to support the government and maintain order. | ||

# | # The pact between industry and the working class: At the same time, the Weimar government sought to promote a social partnership between industry and the working class, thus avoiding potentially destructive class struggles. They sought to encourage cooperation with a view to economic modernisation and social stability. | ||

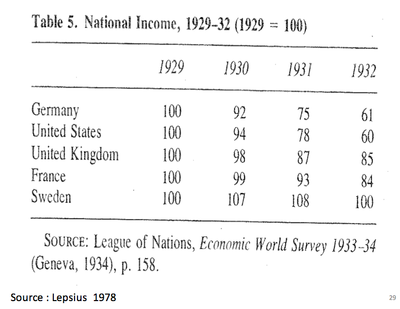

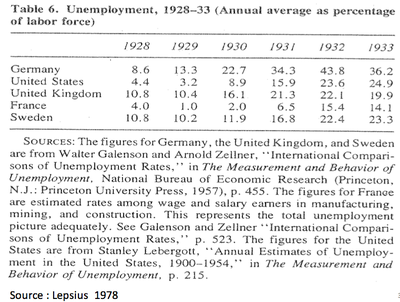

However, these pacts were fragile and under constant economic, social and political pressure. The Great Depression, which began in 1929, created massive economic tensions and exacerbated class divisions, ultimately contributing to the collapse of these arrangements and the rise of Nazism. | |||

A power struggle between conservatives and progressives marked the political situation during the Weimar Republic. The conservatives, including elements of the army, industry and the upper classes, were suspicious of parliamentary democracy and preferred a more authoritarian regime or a traditional monarchical form of government. On the other hand, the Progressives, which included the Social Democratic Party and other left-wing parties, supported parliamentary democracy, social and economic reform, and sought to turn the Weimar Republic into a genuine democratic republic. This power struggle contributed to the political instability of the Weimar Republic, and was exploited by right-wing extremists, notably the Nazis, to undermine confidence in the democratic system and increase their own support. | |||

The erosion of the democratic order in the Weimar Republic was a gradual process, exacerbated by key events such as the dissolution of the agreement between capitalists and workers, and the repercussions of the Great Depression. In June 1933, the partnership between capitalists and workers, which had been a pillar of social and economic stability in the Weimar Republic, began to crumble. This coincided with the rise to power of Hitler, who sought to break the unions and establish a more authoritarian economic system. In addition, the Great Depression that began in 1929 created an uncertain and precarious economic environment. Employers sought to remove social legislation to cut costs and maintain profitability. This not only jeopardised workers' living conditions, but also undermined confidence in the democratic Weimar government and contributed to the rise in support for the Nazi party. | |||

During the Weimar Republic, the army, particularly the senior military hierarchy, began to feel increasingly alienated and marginalised. Many of the military elite were dissatisfied with parliamentary democracy, seeing it as weak and ineffective. They were also unhappy with some of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, particularly the restrictions placed on the size and capabilities of the German army. Conflicts with the civilian government exacerbated these feelings of alienation and marginalisation over issues such as military funding and foreign policy. Over time, parts of the army gradually turned towards more authoritarian political options, including the Nazi party, which promised to restore Germany's military power and prestige. The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party ultimately benefited from these feelings of alienation within the army. Hitler exploited these frustrations to gain the support of large army sections, which was a key factor in his rise to power and the fall of the Weimar Republic. | |||

As the Weimar Republic progressed, the coalition that had supported it weakened. This coalition, often called the "Weimar coalition", comprised the Social Democrats, the Left Democrats and the centre parties. However, in the face of economic pressure, social unrest and the rise of political extremism, this coalition began to fragment. Against this backdrop, conservative forces, which had been relatively marginalised in the early years of the Weimar Republic, began to regain ground. Many of these conservatives were suspicious of parliamentary democracy and preferred a more authoritarian regime. As these pacts unravelled, the instability of the Weimar Republic worsened. This eventually created a vacuum that the Nazis could fill, leading to the end of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of the Third Reich. | |||

The breakdown of the Weimar Republic began long before Hitler came to power in 1933. A key step was the appointment of Heinrich Brüning as Chancellor in 1930 by President Paul von Hindenburg. Brüning, a member of the Catholic Centre, was appointed Chancellor at a time of economic crisis and growing political polarisation. Unfortunately, Brüning could not overcome these challenges and was forced to govern mainly by presidential decree due to parliamentary opposition. This not only contributed to political instability, but also eroded confidence in parliamentary democracy. Brüning himself was forced to resign in 1932, and the two chancellors who succeeded him were equally unable to stabilise the situation. In the end, this period of political instability and economic crisis paved the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler, who was appointed Chancellor in January 1933. | |||

After Heinrich Brüning resigned in 1932, President Paul von Hindenburg used his power of appointment to nominate Franz von Papen as Chancellor. Von Papen, a conservative aristocrat, tried unsuccessfully to form a stable government with the support of nationalist conservatives and the Nazi party. However, his efforts failed and he was replaced later in 1932 by a German army general, Kurt von Schleicher. Von Schleicher also failed to form a stable government, eventually leading to Adolf Hitler's appointment as Chancellor in January 1933. Hermann Göring, a leading member of the Nazi party, played a key role in consolidating Nazi power after Hitler's appointment. As Prussia's Minister of the Interior, Göring purged the Prussian police of non-Nazi elements and used it to crack down on opponents of the Nazi regime. Although legal under the Weimar constitution, these appointments by presidential decree undermined confidence in parliamentary democracy and contributed to the rise of Nazism. | |||

By 1932, Adolf Hitler's position as the dominant figure of the radical right in Germany had become increasingly clear. His party, the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP, or Nazi Party), had achieved significant success in the Reichstag elections that year, becoming the largest party in the German parliament. However, despite the Nazi party's electoral success, Hitler was not yet in power. President Paul von Hindenburg was reluctant to appoint him Chancellor, and other conservative German politicians hoped to use the influence of the Nazi party without allowing Hitler to take complete control. However, these attempts failed. Due to the polarisation of German politics and the ongoing economic crisis, no other political leader or party was able to gather sufficient support to form a stable government. In this context, Hitler appeared to many as the only leader capable of overcoming the crisis. As a result, he was appointed Chancellor by Hindenburg in January 1933. | |||

President Paul von Hindenburg finally appointed Adolf Hitler Chancellor in January 1933 despite his initial reluctance. Hindenburg, a Prussian conservative and former army officer, was not a supporter of Nazism. However, faced with political instability and increasing pressure from those around him, he finally gave in. Hindenburg hoped that Hitler, once appointed Chancellor, would be controllable through a coalition with non-Nazi conservatives, who would have a majority in the government. Hitler had also promised to govern in accordance with the Weimar Constitution. However, these expectations proved false. Once in power, Hitler and the Nazi party quickly consolidated their control over the German state, removing constitutional checks and balances and suppressing all opposition. As a result, Hitler's appointment marked the beginning of the end for the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the totalitarian regime of the Third Reich. | |||

Hindenburg's decision to appoint Hitler as Chancellor was a serious miscalculation. Although he hoped that Hitler and the Nazis would be contained by the rest of the government and by constitutional constraints, these hopes quickly evaporated once Hitler was in power. Hitler skilfully manipulated Germany's political and institutional system to consolidate his power. After the Reichstag fire in February 1933, Hitler persuaded Hindenburg to declare a state of emergency, which allowed the Nazis to suspend many civil liberties and arrest their political opponents. Then, following elections in March 1933, the Nazi Party succeeded in passing the Act of Full Power (Ermächtigungsgesetz), which essentially gave Hitler the power to legislate without the consent of parliament or the president. Overall, Hitler's appointment opened the door to the installation of a totalitarian regime. He used the institutional framework of the Weimar Republic to dismantle democracy from within, transforming Germany into a dictatorial state. | |||

After being appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Hitler and the Nazi party began a rapid consolidation of power, gradually dismantling the democratic institutions of the Weimar Republic and establishing a totalitarian state. The burning of the Reichstag in February 1933 provided Hitler with an opportunity to convince President Hindenburg to declare a state of emergency, allowing the Nazis to suspend civil liberties and suppress political opposition. The Nazi government also used a series of decrees to restrict the press and freedom of expression and to tighten their control over the judiciary and police forces. In March 1933, the Nazi government passed the Act of Full Power (Ermächtigungsgesetz) in the Reichstag, which essentially gave Hitler the power to legislate without the consent of parliament. By July 1933, all other political parties had been banned, making Germany a one-party state. In the years that followed, the Nazi regime continued its expansion of state control, setting up a vast apparatus of propaganda and surveillance, reorganising education and culture according to Nazi ideals, and launching massive campaigns of persecution against those it considered enemies of the regime, including Jews, Communists, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and other marginalised groups. In sum, the seizure of power by Hitler and the Nazi Party marked the beginning of a dark period in German and world history, in which the fundamental principles of democracy and human rights were systematically dismantled and replaced by an authoritarian and oppressive regime. | |||

[[Image:VO zum Schutz von Volk und Staat 1933.JPG|thumb|Reichstagsbrandverordnung du 28 février 1933.]] | [[Image:VO zum Schutz von Volk und Staat 1933.JPG|thumb|Reichstagsbrandverordnung du 28 février 1933.]] | ||

The introduction of censorship marked a turning point in the rise to power of Hitler and the Nazis. From 4 February 1933, with the promulgation of the "Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the German People", severe censorship was imposed on the media, with a specific ban targeting socialist and communist newspapers. This measure was part of the Nazi strategy to suppress all political opposition and control the information disseminated to the public, intending to shape public opinion in line with their ideology. The institutional framework of the Weimar Republic was systematically dismantled, paving the way for the Nazi dictatorship. | |||

The burning of the Reichstag on 27 February 1933 was a key event in the Nazi takeover. The Nazis blamed the fire on Marinus van der Lubbe, an unemployed Dutch communist. This incident enabled Hitler to convince President Hindenburg to issue the "Reichstag Decree for the Protection of the People and the State" on 28 February 1933. This decree, often called the "Reichstag Fire Decree", suspended many civil liberties, including freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to a fair trial, confidentiality of mail and telephone communications, and protection from illegal search and seizure. This decree also allowed the Nazi regime to arrest thousands of members of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and other opposition parties, and imprison them without trial. In addition, the government used the decree to justify a series of laws that consolidated Nazi power and established the structure of Hitler's dictatorship. In March 1933, the German parliament passed the "Full Powers Act", which gave Hitler the power to rule by decree, marking the end of democracy in Germany. | |||

The elections of 5 March 1933 took place against a backdrop of widespread political repression and terror directed against left-wing parties. Although the elections were not entirely free and fair, they marked an important turning point in the consolidation of power by the Nazi Party. The Nazi party won 43.9% of the vote, a significant increase on previous elections. With the support of the German National Centre Party (DNVP), which obtained 8% of the vote, they could form a majority. However, it should be noted that this electoral victory would not have been possible without the mass arrests of communist and socialist activists that took place after the Reichstag fire. These arrests, along with the banning of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), created a climate of fear and intimidation that favoured the Nazi Party. As a result, the legitimacy of the elections was widely contested. Nevertheless, they enabled the Nazi party to consolidate its power and establish an authoritarian regime that would last until the end of the Second World War. | |||

On 23 March 1933, the German Parliament passed the Enabling Act, which suspended the constitution of the Weimar Republic for a period of four years. This Act gave Adolf Hitler and his government the power to legislate without the intervention of Parliament, and even to amend the Constitution. This act marked a crucial stage in Hitler's rise to absolute power in Germany. Only members of the Social Democratic Party voted against the Act, while Communist Party MPs had already been imprisoned or banned from sitting in Parliament following the Reichstag fire. The Full Powers Act paved the way for establishing the totalitarian regime of the Third Reich, where Hitler's personal dictatorship was to last until the end of the Second World War. | |||

In the space of just seven weeks, beginning with his appointment as Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg on 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler succeeded in consolidating his power and establishing an authoritarian regime in Germany. Using both legal strategies, such as the manipulation of the political process, and illegal ones, such as intimidation and repression, Hitler neutralised the opposition and gained almost absolute control over the German government. This rapid chain of events marked the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the Nazi dictatorship, also known as the Third Reich. This period had disastrous consequences for Germany and the whole world, ultimately leading to the Second World War and the Holocaust. | |||

Having solidified his position in power in the spring of 1933, Hitler continued to consolidate his control over Germany throughout the summer of 1933 and into 1934. Among the measures taken was abolishing all political parties other than the Nazi Party, making Germany a one-party state. The independent trade unions were dissolved and replaced by a Nazi organisation, the German Labour Front, thus completely controlling the labour sector. Germany's regions also lost their autonomy, and their governments were replaced by Nazi administrators, centralising power in Hitler's hands. The summer of 1934 was also marked by the purge of members of the SA (the "brown shirts") during the "Night of the Long Knives", which allowed Hitler to eliminate any potential opposition from within his own party. In August 1934, after the death of President Paul von Hindenburg, Hitler proclaimed himself "Führer", merging the posts of Chancellor and President and assuming total control of the German state. This period marked the definitive end of democracy in Germany and the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship under the Third Reich. | |||

In 1934, Adolf Hitler consolidated his grip on power in Germany in two significant ways. Firstly, in July, he eliminated any potential opposition within the Nazi Party in the "Night of the Long Knives", a purge during which the leaders of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the paramilitary force of the Nazi Party, were arrested and killed. This strengthened Hitler's control over the party and eliminated a potential rival for power. Then, on the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in early August 1934, Hitler merged the posts of President and Chancellor, proclaiming himself "Führer und Reichskanzler" (Leader and Chancellor of the Reich). This meant that Hitler now held supreme authority over the German state, controlling both the executive and the presidency. Thus, in the course of that year, Hitler succeeded in establishing a totalitarian dictatorship in Germany, with all political power concentrated in his hands. The Nazi Party, under his leadership, was the only authorised party, and any opposition, political or otherwise, was brutally suppressed. | |||

Following Adolf Hitler's accession to the presidency and the post of Chancellor in 1934, Germany underwent a radical political regime change. The parliamentary democracy of the Weimar Republic gave way to the authoritarian regime of the Third Reich. This was the period when German society was completely transformed and aligned with the ideals of the Nazi party, a process known as "Gleichschaltung", or coordination. During this period, all institutions, including political parties, trade unions and the media, were controlled and manipulated by the Nazi party. Opposition was eradicated, either through persecution or intimidation. Anti-Semitic laws were enacted, beginning with the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which reduced Jews to the status of sub-citizens. These changes laid the foundations for what is generally recognised as a totalitarian regime, characterised by an absence of individual freedom, absolute state control over all aspects of life, the existence of a single party and omnipresent propaganda. The aim was to create a homogenous, ideologically pure Nazi state, ready to realise Hitler's expansionist ambitions that would lead to the Second World War. | |||

=== | === The democratic potential of the Weimar Republic === | ||

The Weimar Republic's ability to develop as a democracy was limited and confined. This can be interpreted through the prism of the different political visions advocated by the various political parties at the time. Were these visions oriented towards democracy, authoritarianism, socialism or communism? | |||

The democracy established by the Weimar Republic was an innovation for Germany. Democratic ideas and practices were still new and alien to many of the population and elites, who had lived under an authoritarian empire for generations. Weimar democracy certainly had democratic potential, but it was limited and faced many internal and external challenges. The political parties that developed during this period represented various political ideologies - democratic, authoritarian, socialist and communist. The Social Democratic Party (SPD), for example, had a democratic vision and supported a mixed economy with elements of socialism. On the other hand, the Communist Party (KPD) sought to overthrow the system of the Weimar Republic and establish a workers' republic based on the Soviet model. The Catholic Centre and right-wing parties such as the DNVP were more conservative, and some of their members were sceptical or opposed to Weimar democracy. Finally, Hitler's National Socialist Party (NSDAP) eventually came to power, was explicitly anti-democratic and favoured authoritarian rule based on fascist ideology. As a result, the political environment of the Weimar Republic was in reality a complex amalgam of competing visions of political order. These deep ideological divisions and severe economic and political crises hampered the development of a stable and widely accepted democratic culture. | |||

The democratic dimension of a regime can be assessed by the number or percentage of votes attributed to political parties that support a democratic political system. The greater the number of political factions supporting democratic institutions, the stronger democracy becomes, consolidating its base. A redistribution of partisan forces can have direct and immediate consequences for the character of the political regime in place. | |||

During the era of the Weimar Republic, three main political currents can be identified: democratic, authoritarian, and two distinct left-wing currents, communism and independent socialism. | |||

==== The democratic trend ==== | |||

The democratic trend was carried and supported by the "Weimar Coalition", comprised of the Social Democratic Party, the (Catholic) Centre Party and the left-wing Liberal Party. These political players were the guardians of the democratic order, working to ensure the stability and maintenance of the parliamentary system. This coalition, often referred to as the "Weimar coalition", was truly the foundation on which the democracy of the Weimar Republic was built. It played a decisive role at several key levels in establishing and defending this democratic regime. Firstly, it was the driving force behind the peace process after the First World War, signing the armistice. This decision ended the war and enabled the emergence of an environment conducive to establishing a new political and social structure. The Weimar coalition then played a key role in laying the constitutional foundations for the new Republic. | |||

The coalition parties - the Social Democrats, the Centre Party (Catholic) and the Left Liberals - worked together to draw up a constitution that established a parliamentary democracy, a first for Germany. This was a decisive step towards consolidating the democratic order. Finally, as the Weimar Republic endured periods of instability in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the coalition staunchly defended the democratic system. Despite economic crises, rising unemployment and the rise of political extremism, notably Nazism, the coalition maintained its support for democracy, constantly seeking to strengthen its stability. | |||

==== Authoritarian parties ==== | |||

Authoritarian parties, such as the Right Liberals and the Conservative Party, were mainly composed of those who aspired to return to the old order of the Empire and the monarchy. These political factions were largely made up of middle-class members who were worried about social and socialist reforms. Their apprehension was motivated by the fear that these reforms would upset the economic and social balance and threaten their societal position. Moreover, this authoritarian ideology was strongly imbued with a deep-seated belief in Germany's unique political and social trajectory. In their view, Germany had a unique path to follow towards modernity and democracy, different from that followed by other European countries. They were convinced that Germany had its own traditions and values to guide its development rather than conforming to the political and social models prevailing elsewhere in Europe. | |||

By 1919, several Western European countries, such as France and Great Britain, had already established stable democracies. However, Germany was in a different position following the Empire's fall and the Weimar Republic's establishment. Germany's path to democracy was unique, marked by its own historical, cultural and social realities. Advocates of Germany's own path believed that we should not simply imitate the democratic models of our neighbours but rather develop a form of democracy tailored to Germany's specific characteristics. This conviction was based on the idea that Germany had its own traditions, its own social and political structures, which could not simply be replicated on the model of Western democracies. | |||

The advocates of an authoritarian path in Germany valued the notion of a competent elite holding power. For them, the political ideal was a form of government in which those who were best qualified, often from a particular social class or educational background, would assume leadership roles. They believed that this model would provide the stability and competence needed to navigate effectively through the complex challenges of the time. This vision is often described as elitist and undemocratic, as it is clearly distinct from the democratic idea of power derived from the people, with fair participation and representation of all citizens. This highlighted the tension that existed in Germany between different visions of political and social organisation. This tension played a major role in the struggle for Germany's political future during the Weimar Republic. | |||

Supporters of the authoritarian vision in Germany argued for a strong state that would be able to regulate and suppress conflicts between different interest groups within civil society. In their view, the state should play the role of ultimate arbiter, ensuring that particular interests do not prevail over the common good. In this model, the state should not simply be a neutral body that manages public affairs but rather a force that can actively shape society and promote national unity. They also favoured strong social and political integration, emphasising a sense of belonging to a wider community. They believed this form of integration would help promote social cohesion and strengthen national solidarity. It was part of a more general desire to create a strong collective identity that could serve as the basis for a strong and stable government. While these ideas clashed with the democratic vision of governance, they resonated with many Germans at the time, particularly those dissatisfied with the economic and social challenges facing Germany during the Weimar Republic. | |||

Supporters of authoritarianism during the period of the Weimar Republic in Germany emphasised their distrust of democracy and the plurality of social groups. For them, democracy, with its propensity to allow many voices and opinions, could potentially lead to disorder and instability. They firmly believed in the ability of educated and skilled elites to govern more effectively and balanced than the general public. Elitism was, therefore, a key component of their ideology. They also defended the state's role as an active agent in establishing and maintaining order and security. State interventionism was therefore seen as an essential means of guaranteeing the common good rather than letting the market or other unregulated social forces determine the direction of society. | |||

==== Communists and independent socialists ==== | |||

Divisions within the socialist movement played a major role in German politics during the Weimar Republic. After the end of the First World War, a radical faction of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) split off to form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). The leaders of this new political formation, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, were known for their revolutionary tendencies and their criticism of social democracy for supporting the war and refusing to transform the capitalist system. Their group, initially called the Spartakist League, played a key role in the German revolutions of 1918-1919. However, this split weakened the German left, leaving the SPD and KPD at odds on many issues and unable to form a stable coalition. This division ultimately facilitated the rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party. | |||

The Communist Party and a fraction of the Socialist Party (especially after the split that led to the creation of the Communist Party) supported a political order based on communism. They sought to overthrow the existing capitalist system and establish a society in which the means of production were held in common and wealth was distributed equally among all members of society. Their vision was revolutionary, as they believed this transformation could only be achieved through a radical break with the existing system. This vision was rooted in Marxist philosophy, which advocates proletarian revolution as the means to end capitalist exploitation. In practice, however, the German Left was divided and at odds over how to achieve this transformation. This contributed to their inability to effectively resist the rise of the Nazi party, which exploited these divisions to consolidate its own power. | |||

= | ==== Analysis of political opinions in the population ==== | ||

[[Fichier:National_election_in_germany,_1907_-_33.png|center|thumb|400px]] | |||

When analysing these data, it is clear that during the Weimar Republic, there was a plurality of political opinions among the population. Almost half the electorate on average supported a democratic political order, while a third preferred a more authoritarian structure. Radical left-wing parties, which promoted a revolutionary transformation of society, attracted a significant but minority share of the electorate, between 10% and 20%. Finally, around 10% of the electorate was undecided, voting for more "particularist" parties, often representing specific or regional interests. These undecided voters played a crucial role. Given the fragmented political system of the Weimar Republic, these votes could often tip the balance in favour of one party or another in elections, thereby influencing the country's political direction. This situation was further complicated by the proportional representation system used at the time, which often led to the formation of unstable coalition governments. | |||

A change of government had the potential to lead to a complete transformation of the political order. This was demonstrated in 1933, when the conservatives and right-wing liberals returned to power under Hitler. This event marked a radical break with the democratic principles of the Weimar Republic and ushered in a new era of totalitarianism under the Third Reich. | |||

The Weimar Republic was characterised by its limited democratic potential and lack of progress. This highlighted the fragility of democratic institutions, which were constantly under considerable political and socio-economic pressure. Numerous governments and coalitions have been formed and then dissolved, illustrating the political instability and the difficulty of maintaining a lasting political consensus. Conflicts between different political factions, economic upheaval, soaring inflation and mass unemployment have fuelled social discontent and uncertainty, undermining public confidence in the democratic system. In addition, Germany's lack of a strong democratic tradition has complicated the situation. The shifting and uncertain political order created a vacuum that anti-democratic forces, notably the Nazis, could exploit, ultimately leading to the Weimar Republic's collapse and Adolf Hitler's rise. | |||

= Analysis of the causes of the fall of the Weimar Republic = | |||

== The influence of the party system == | |||

During the Weimar Republic, Germany's political landscape was highly fragmented. It was marked by the presence of four major political currents: democratic, authoritarian, independent socialist and communist. | |||

# The democratic current was mainly driven by the "Weimar coalition", which brought together the Social Democratic Party, the (Catholic) Centre Party and the left-wing Liberal Party. They supported the establishment and defence of a democratic constitutional order. | |||

# The authoritarian current was supported by the right-wing liberals and the conservative party, who were nostalgic for the Empire and the monarchy and sought to promote a specific German path to modernity, distinct from that of other European countries. | |||

# The Independent Socialists, on the other hand, represented a faction of the left that had broken away from the main Social Democratic party. They were generally more radical in their political and social positions. | |||

# Finally, the Communists sought to promote a revolutionary and egalitarian political order. This current was embodied by the Communist Party, formed after the split between the radical and social-democratic left. | |||

Each of these groups had distinct visions of the desired political order for Germany, which led to intense political competition and governmental instability. | |||

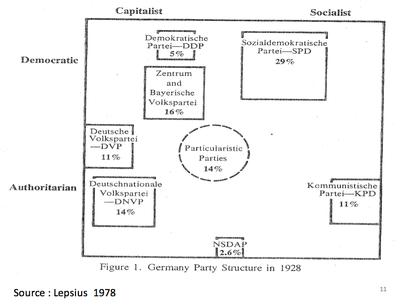

[[Image:Germany_party_structure_in_1928.png|center|thumb|400px]] | |||

This graph is a representation of the different parties with two axes: | |||

* The vertical axis would represent the position of the parties on the political spectrum ranging from democratic (top) to authoritarian (bottom). | |||

* The horizontal axis would represent the parties' position on the economic spectrum, ranging from capitalism (on the right) to socialism (on the left). | |||

The percentages refer to the results of the German parliamentary elections of May 1928. This was the Weimar Republic's parliamentary election with the highest turnout and was widely regarded as a victory for the pro-democratic parties. In these elections, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) came out on top with around 30% of the vote, followed by the Centre Party with around 12%. The National People's Party of Germany, a more authoritarian political force, received around 14% of the vote, and the Communist Party of Germany around 10%. The rest of the votes were split between several smaller parties. | |||

The DNVP mainly represented the interests of the landed aristocracy and conservative Protestants, who were often sceptical of parliamentary democracy. The liberal landscape was fragmented, with the Progressive Democrats (DDP) having a more left-wing orientation and supporting parliamentary democracy. In contrast, the German People's Party (DVP) had a more right-wing orientation and was often sceptical of the Weimar Republic. The Centre (Zentrum) was a Christian-democratic political party with a strong base among Catholics, particularly in western and southern Germany's rural and industrialised areas. Finally, the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) was the largest left-wing party at the time, with a strong base among working-class people in the major urban centres. The SPD played a key role in establishing the Weimar Republic and supported a democratic and social vision of Germany. | |||

Political instability and the increasing fragmentation of the political landscape were defining features of the Weimar Republic. In 1919, the Communists split from the Social Democratic Party to form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which weakened the left and contributed to political polarisation. In Bavaria, the Bavarian People's Party (BVP) split from the Zentrum in 1919, representing the specific interests of Bavarian Catholics. This also contributed to the fragmentation of the political landscape. Among the liberals, the German People's Party (DVP) emerged in 1918 as a right-wing liberal party, while the German Democratic Party (DDP) was a left-wing liberal party. This division weakened the liberal camp. Finally, with the emergence of the Nazi party (NSDAP) in the 1920s, the political spectrum became even more polarised. The Nazi party gained ground by exploiting economic and social discontent after the Treaty of Versailles and the Great Depression, and by stirring up fear and hostility towards Communists and Jews. These developments contributed to the instability and fragmentation of the political landscape during the Weimar Republic, paving the way for the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party. | |||

It should be remembered that the formation of this party structure took place in the period 1870 - 1890, which reflected multiple and long-standing social cleavages such as the cleavage between those who wanted a marked order between a State religion and secular trends. There were also divisions between the urban and rural worlds (town and country) and regional divisions such as Bavaria's desire to have a party that would represent its own interests at national level. | |||

The rapid industrialisation of Germany from the 1870s onwards caused a significant split in society. On the one hand, there were those who benefited directly from industrialisation, such as entrepreneurs, industrialists and certain middle class sectors, who supported capitalism and generally opposed any form of meaningful social legislation. On the other hand, there were those directly affected by the negative effects of industrialisation, such as industrial workers, who demanded more social protection. They demanded better working conditions, higher wages, legislation on child labour and other social protection measures. These demands led to the creation of workers' political parties, such as the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which supported these demands and sought to implement social reforms through legislation. This tension between supporters of unregulated capitalism and those who argued for state intervention to protect workers and regulate working conditions was one of the main political cleavages of the period. | |||

The existence of these multiple social cleavages profoundly shaped the political landscape of the time, leading to a plurality of political parties rather than a two-party system. Instead of having two clearly defined and opposing political forces, the Germany of the Weimar Republic was characterised by many parties representing different strata and segments of society. These parties varied considerably regarding ideology and political objectives, making it difficult to form stable and lasting coalitions. This also created a climate of political fragmentation, where competition was not limited to two main blocs, but involved many parties vying for power. As a result, the Weimar Republic was politically unstable, with coalition governments often short-lived and no single party or political bloc able to secure a clear and stable majority. This political fragmentation contributed to the instability and volatility that eventually led to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the advent of the Nazi regime. | |||

Despite the political fragmentation, two government coalitions emerged during the Weimar Republic, both centred around the Centre Party. | |||

* | * The Democratic Coalition: This comprised the Social Democratic Party (SDP), the left-wing liberals of the German Democratic Party (DDP), the Zentrum (Centre Party) and the Bayerische Volkspartei (Bavarian People's Party). This coalition tended to favour democratic principles and represented an alliance of the left and centre-left. | ||

* | * The bourgeois coalition: This coalition was formed by the Centre Party, the two liberal parties (the left-wing DDP and the right-wing German People's Party - DVP) and the conservatives of the German National People's Party (DNVP). This coalition represented a more conservative alliance and tended to favour liberal economic policies. | ||

These coalitions were the main governmental configurations in Germany during the Weimar Republic, from 1919 to 1933. However, political fragmentation and deep ideological divisions made these coalition governments unstable and short-lived, ultimately contributing to the collapse of the Weimar Republic. | |||

The second coalition, which we might call the "bourgeois coalition", was united by its support for capitalist economic policies. Still, there were deep differences within the coalition regarding Germany's ideal political structure. These differences were mainly based on differing visions of democracy and authority. The left-wing liberals (German Democratic Party - DDP) favoured democratic principles, including representative government and civil rights. They believed in the rule of law, and many strongly opposed any return to authoritarianism or monarchy. On the other hand, right-wing liberals (German People's Party - DVP) and conservatives (German National People's Party - DNVP) had more authoritarian tendencies. They tended to be more sceptical of democracy, supporting a more elitist and authoritarian vision of the state. Some of them were nostalgic for the German Empire and might support a return to a form of monarchy or a more authoritarian regime. These ideological differences made cooperation within the coalition difficult and contributed to the political instability of the Weimar Republic period. | |||

The significant ideological differences between the parties within these coalitions hampered their ability to govern coherently and stably. During the 14 years of the Weimar Republic, the "democratic coalition" was in power for around five years, and the "bourgeois coalition" for around two years. For the remaining seven years, no majority coalition could be formed, leading to the establishment of minority governments. These governments were often unstable and found it difficult to gain sufficient support for their policies, which contributed to the general political instability of the period. | |||

From 1919 to 1933, the Weimar Republic experienced chronic political instability, with twenty different governments formed during this period. These governments were often formed in response to immediate crises and were generally oriented towards short-term solutions. For example, they had to deal with challenges such as the Treaty of Versailles, the hyperinflationary crisis of the early 1920s, the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s, and growing political unrest from the far right and left. Coalitions of several political parties often formed these governments. Still, these coalitions were often unstable and found it difficult to maintain a majority in Parliament due to ideological or political disagreements between their members. This chronic political instability ultimately contributed to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the Nazi party and its leader, Adolf Hitler. | |||

The fragmentation of the political landscape during the Weimar Republic did hamper political stability and had repercussions on the perceived legitimacy of the government in power. The parties of the "Weimar coalition", which were largely responsible for implementing the new democratic republic, found themselves facing a major political challenge. Firstly, they were criticised for their inability to effectively manage the economic crisis and social tensions. The terms of the Treaty of Versailles exacerbated the economic difficulties, which imposed heavy economic reparations on Germany. Secondly, the "Weimar coalition" was held responsible for setting up a democratic regime that seemed incapable of guaranteeing stability and security. Their political legitimacy was increasingly contested, especially as they were perceived to be out of touch with the realities of the population. Ultimately, these factors, combined with a rise in political extremism, led to the rise of the Nazi party, which used these weaknesses to fuel their discourse and win support. Political dissent translated into growing support for the Nazi party, eventually leading to the end of the Weimar Republic and the advent of the Third Reich. | |||

As Lepsius explains, the fragmentation of the political system during the Weimar Republic played a significant role in the crisis of democracy that led to the advent of the Third Reich.<ref>Lepsius, M. Ranier. "From Fragmented Party Democracy to Government by Emergency Decree and National Socialist Takeover: Germany." In The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Europe, by Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978, pp. 34-79.</ref> Many political parties with divergent agendas made establishing a stable and effective government difficult. These divisions, exacerbated by the socioeconomic challenges of the time, created an atmosphere of political instability and social discontent. Moreover, this fragmentation allowed extremist parties to gain ground, capitalising on public frustration at the inability of government coalitions to respond effectively to the nation's problems. In short, the lack of cohesion and clear direction within the German political system of the Weimar Republic contributed significantly to the rise of Nazism and the collapse of democracy in Germany. | |||

== | == The implications of the electoral system == | ||

The proportional electoral system, like the one in place during the Weimar Republic, is designed to ensure that the percentage of seats a party wins in parliament reflects as closely as possible the percentage of the electorate it has won. This means that a party that gets 10% of the vote should get around 10% of the seats in Parliament. This is different from the majority system, where the party with the most votes in a constituency gets all the seats in that constituency. This system is often used to encourage a greater diversity of political views in government. However, it can also lead to political fragmentation and governmental instability, as was the case during the Weimar Republic, as it can be more difficult for a single party to secure a clear majority. | |||

A proportional electoral system aims to ensure fair representation of all segments of society, including small parties and minority groups. In such a system, parties with a relatively small vote share can still obtain representation in parliament, which is not generally the case in majority electoral systems. This allows for diverse opinions and political positions in the decision-making process, which can help reflect and respond to a wider range of societal concerns and interests. However, one of the potential disadvantages of a proportional system is that it can lead to political fragmentation and governmental instability. This is because parties can struggle to achieve a clear majority in parliament, often necessitating the formation of coalitions, which can be difficult to maintain and manage effectively. | |||

The question of the electoral threshold is an important feature of proportional electoral systems. The electoral threshold is the minimum percentage of votes that a party must obtain to be eligible for the allocation of seats in parliament. This threshold can vary considerably from country to country, generally ranging from 1% to 10%. The purpose of this threshold is to prevent too much parliamentary fragmentation, which could make government unstable or ineffective. On the other hand, too high a threshold can hinder the representation of small parties and minorities, which contradicts the original aim of the proportional system. In the Weimar Republic, the system was full proportional representation with no electoral threshold. This meant that any party that obtained enough votes for a seat was entitled to representation in parliament. This led to a high degree of parliamentary fragmentation, with many small parties represented, which contributed to the instability of the political system at the time. | |||

The Weimar Republic had a "pure" or "integral" proportional electoral system, meaning that there was no official electoral threshold for a party to win seats in parliament. In practice, the actual threshold was very low, probably around 0.4%, corresponding to the proportion of votes needed to win a single seat in the Reichstag, which had around 600 members. The absence of an electoral threshold in the Weimar Republic system meant that many small parties could enter parliament, exacerbating political fragmentation. While this may have ensured a very accurate representation of public opinion, it also made it more difficult to form stable coalitions in government. It contributed to the political instability of the period. | |||

In a "pure" proportional electoral system, such as that of the Weimar Republic, the absence of an electoral threshold enabled many small parties to obtain representation in parliament. This led to a faithful reproduction of social cleavages and various political tendencies within parliament. However, the consequence of this political fragmentation has been to make it more difficult to form stable government coalitions. With so many small parties with different interests and priorities, it was often necessary to negotiate complex compromises to form a parliamentary majority. Moreover, once formed, these coalitions were often precarious and prone to instability, as a small party could easily bring down the government by withdrawing from the coalition. In addition, this system made the government more vulnerable to political crises and conflicts. Without a clear and stable majority, it was difficult for the government to take quick and effective decisions in response to crises. This contributed to a perception of inefficiency and instability in the democratic system, fuelling discontent and distrust of the Weimar Republic. In short, although the 'pure' proportional electoral system of the Weimar Republic ensured accurate representation of public opinion, it also contributed to the political instability of the period and the undermining of the democratic system. | |||

{| style="border: 1px solid #999; background-color:#FFFFFF" border="0" align="center" | {| style="border: 1px solid #999; background-color:#FFFFFF" border="0" align="center" | ||

| Ligne 220 : | Ligne 228 : | ||

|} | |} | ||

One of the disadvantages of the pure proportional electoral system is that it favours fragmented parliamentary representation, with many small parties. This can make the formation of stable government coalitions more difficult. In the case of the Weimar Republic, many seats were won by parties with a low percentage of the vote, leading to a highly fragmented parliament. This meant that no single party could obtain an absolute majority, and that coalitions between several parties had to be formed to govern. However, these coalitions were often unstable, as they depended on smaller parties' willingness to cooperate. Moreover, as these small parties often represented specific interests or divergent ideologies, finding common ground and maintaining the coalition's unity was difficult. As a result, the pure proportional electoral system of the Weimar Republic not only made it difficult to form stable coalitions but also contributed to political instability in general. This certainly contributed to the weakening of the democratic regime and its ultimate demise with the coming to power of Adolf Hitler in 1933. | |||

If we consider a parliament of 481 seats and that 16% of the seats are held by parties that obtained 4.5% or less of the popular vote, this means that these small parties hold 77 seats. If we add the parties that received less than 5% of the vote, which account for 21% of all seats, we get around 101 seats. This again illustrates the fragmentation of the political landscape in the Weimar Republic, with many small parties represented in parliament. This would undoubtedly have made it difficult to form stable coalitions, contributing to the political instability of the time. This confirms that the electoral system of the Weimar Republic led to considerable fragmentation of the political landscape, making the formation of stable governments more difficult. This situation is characteristic of proportional representation systems without a high electoral threshold, which favour the representation of small parties but can lead to political instability. | |||

Many scholars argue that the system of proportional representation was one of the factors that contributed to the political instability of the Weimar Republic. However, it should be pointed out that this assertion is often debated and that the failure of the Weimar Republic was the result of many factors, not just the electoral system. The proportional representation system allowed many political parties to be represented in parliament, resulting in political fragmentation. This has made it difficult to form stable governments and take political decisions. It has also allowed extremist parties to gain political representation, contributing to political instability. | |||

After the Second World War, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) made major changes to its electoral system to resolve some of the problems that had plagued the Weimar Republic. The new constitution, the Basic Law, established a system of mixed parliamentary government. Under this system, half of the Bundestag members (the German parliament's lower house) are elected directly from single-member constituencies. In contrast, the other half are elected from party lists on a proportional basis. This system, often called the mixed electoral system or mixed-member electoral system, aims to combine the advantages of proportional representation and single-member constituencies. In addition, a threshold clause was introduced, stipulating that a party must obtain at least 5% of the national vote, or win at least three direct seats, to be entitled to additional seats through proportional representation. This was done to avoid excessive fragmentation of Parliament and promote political stability. Since introducing these reforms, the German political system has been generally stable, with governments lasting full office. | |||

It is possible that the introduction of a representation threshold, such as that adopted in post-war Germany, could have impacted the rise of the National Socialist Party (NSDAP) to power. However, this complex issue depends on a series of other factors. On the one hand, a higher threshold could have excluded some smaller parties from parliament and thus concentrated seats among the larger parties, potentially including the NSDAP, which won a substantial vote in the 1932 and 1933 elections. On the other hand, the threshold may also have prevented some extremist or radical parties from entering parliament, thereby reducing their legitimacy and visibility. This could have impacted the political dynamics of the time and perhaps slowed the rise of the NSDAP. | |||

The proportional system of the Weimar Republic certainly contributed to the political landscape's fragmentation and the government's instability. Still, it was only one factor in the failure of the Republic. Other major factors included the devastating effects of the Treaty of Versailles, the global economic crisis that followed the stock market crash of 1929, power struggles within the government, the erosion of public support for parliamentary democracy, the absence of a strong democratic tradition in Germany, and of course, the rise of National Socialism. The nature of the Weimar Republic's political system - a parliamentary democracy with a weak head of state and full proportional representation - may have facilitated Adolf Hitler's rise to power. Still, it was certainly not the only cause. Ultimately, it was a combination of internal and external factors that led to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the Third Reich. | |||

== | == The impact of the constitutional framework == | ||

Another institutionalist explanation of the constitutional framework refers to the analysis of the causes of the fall of the Weimar Republic from an institutionalist perspective. Institutionalism is an approach in the social sciences that focuses on the roles of institutions (such as rules of governance, norms, legal structures, etc.) in determining social, economic and political outcomes. In the case of the Weimar Republic, an institutionalist explanation of its collapse examines how the constitutional structure, electoral system and other institutions contributed to the political crisis and the rise of Nazism. For example, Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed the President to issue emergency decrees, was used to bypass parliament and thus contributed to the weakening of the parliamentary system and the rise of executive power. | |||

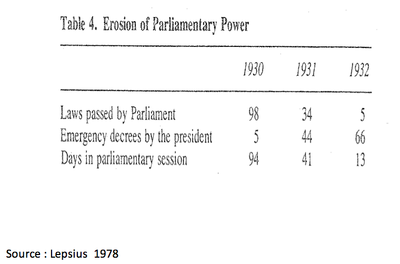

In the final years of the Weimar Republic, parliamentary democracy collapsed, and a more authoritarian regime was established. This is often attributed to Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed the President to issue emergency decrees to "protect public safety and order". In theory, this article was intended to be used only in extreme and temporary situations, but in practice, it was used more frequently and for longer periods. From 1930, Chancellor Heinrich Brüning began to govern almost entirely by presidential decree, bypassing the Reichstag in the process. This marked a significant shift in power from the legislature to the executive and contributed to the rise of authoritarianism. However, it should be noted that the Weimar regime did not develop into a presidential regime in the strict sense of the term. In a typical presidential system, as in the United States, the president is both head of state and head of government, and there is a strict separation of powers between the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. In the Weimar Republic, even at the end, the President remained primarily ceremonial, and the Chancellor retained government control. However, the increased use of presidential powers certainly contributed to the weakening of the parliamentary system. | |||

The constitution of the Weimar Republic, in force from 1919 to 1933, granted several important prerogatives to the President of the Republic, including : | |||

* | * Executive power: The President of the Republic appointed and could dismiss the Chancellor (i.e. the head of government) and government ministers. He, therefore, had a key role in forming the government. | ||

* Article 48 - | * Article 48 - Emergency powers: This was one of the most controversial provisions of the Weimar Constitution. Article 48 allowed the President to take emergency measures to protect public order and national security in the event of a serious threat. These measures could include suspending certain civil rights and using the army to restore order. This article was used on several occasions during the 1930s to govern by decree without parliamentary approval, which contributed to the weakening of the parliamentary government. | ||

* | * Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces: The President of the Republic was also Commander-in-Chief of the German armed forces. | ||

* | * Right to dissolve the Reichstag: The President could dissolve parliament (the Reichstag) and order new elections. This gave him a degree of control over the legislative process. | ||

These prerogatives gave the President considerable power, and their use was a major factor in the political instability of the Weimar Republic and, ultimately, in Adolf Hitler's rise to power. | |||

In the German Empire (1871-1918), the Chancellor was responsible not to parliament (the Reichstag), but to the Emperor. The system of governance was authoritarian, and the emperor had vast powers. In contrast, the Constitution of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) had established a parliamentary system in which the Chancellor was responsible to the Reichstag. In theory, the Constitution of the Weimar Republic was designed to create a parliamentary system in which the Chancellor, who was the head of government, was responsible to parliament, more specifically to the Reichstag (the lower house of parliament). The President of the Republic had the role of Head of State. Although he had the power to appoint and dismiss the Chancellor, it was provided that the Chancellor was responsible to the Reichstag and not to the President. However, in practice, the powers conferred on the President by the Constitution, in particular Article 48, which allowed him to govern by decree in an emergency, allowed a gradual shift of power from parliament to the executive, weakening the parliamentary character of the system and leading to a more presidential system. This shift was all the more marked from 1930 when the rise of the extremes made it difficult to form stable coalitions in the Reichstag, and President Hindenburg began to appoint chancellors who did not have the confidence of parliament but essentially governed by presidential decree using Article 48. This paved the way for Adolf Hitler's rise to power and the transformation of the Weimar Republic into a totalitarian regime under the Third Reich. | |||

The Constitution of the Weimar Republic granted the President sweeping emergency powers, which played a crucial role in the transition from parliamentary democracy to authoritarian dictatorship. Here is a more detailed explanation of these powers: | |||