« The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 130 : | Ligne 130 : | ||

== Territorial expansion == | == Territorial expansion == | ||

{{Article détaillé| | {{Article détaillé|The conquest of the territory}} | ||

The United States of 1800 will expand rapidly. The [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_and_Clark_Expedition Lewis and Clark Expedition] crosses territories then in Indian hands<ref>[https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/ Full text of the Lewis and Clark journals online – edited by Gary E. Moulton, University of Nebraska–Lincoln]</ref><ref>"[https://web.archive.org/web/20080212142331/http://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/images2.html National Archives photos dating from the 1860s–1890s of the Native cultures the expedition encountered]". [https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/images/people_places Archived from the original on February 12, 2008].</ref><ref>[https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/lewisandclark/ Lewis and Clark Expedition, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary]</ref><ref>"[https://www.wdl.org/en/item/107/ History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark: To the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean]" published in 1814; from the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Digital_Library World Digital Library]</ref><ref>[http://www.lewis-clark.org/ Lewis & Clark Fort Mandan Foundation: Discovering Lewis & Clark]</ref><ref>[http://lcatlas.lclark.edu/ Corps of Discovery Online Atlas, created by Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College].</ref> | |||

<gallery mode="packed" widths=200px heights=200px> | <gallery mode="packed" widths=200px heights=200px> | ||

Fichier:Lewis and clark-expedition.jpg| | Fichier:Lewis and clark-expedition.jpg|"Lewis and Clark on the Columbia River", painted by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Marion_Russell Charles Marion Russell]. | ||

Fichier:Louisiana Purchase New Orleans Thure de Thulstrup.jpg| | Fichier:Louisiana Purchase New Orleans Thure de Thulstrup.jpg|The Star-Spangled Banner of the United States replaces the flag of France on the Place d'Armes in New Orleans. | ||

File:UnitedStatesExpansion.png| | File:UnitedStatesExpansion.png|The purchase of Louisiana was one of many territorial additions to the United States. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Version du 28 avril 2020 à 15:07

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The objective of this course is to understand the development of the United States Constitution that is still in force today in order to see its contradictions and the tensions it generated leading to the Civil War, also known as the Civil War of 1861 - 1865. Changes in politics, religion, and society led to the Monroe Doctrine.

Studying the United States around 1800 provides an understanding of the United States today in terms of both its foreign and domestic political systems.

The Articles of Confederation and the Constitutions of the various States

Shortly after independence in 1776, the States of the Union signed the Articles of Confederation. They are written as a reaction against England limiting the powers of the central government, which otherwise would not allow the union to survive.

At the same time, these 13 states plus a 14th, which is Vermont, each adopts its own constitution. Each of them shows the differences between the states and the preamble to the constitution states: "We, the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, to establish justice, to maintain peace within the United States, to provide for the common defense, to develop the general welfare, and to secure the benefits of liberty for ourselves and our posterity, do hereby enact and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Some states like Pennsylvania are fairly egalitarian states that give the right to vote to all free men who pay taxes. In Pennsylvania we have only one assembly with a collegial executive. Other states, such as Maryland, with a tendency towards slavery, create an assembly and a senate concentrating executive power in the hands of an all-powerful governor elected by the big landowners who also have the right to vote.

In New Jersey, suffrage is limited to those with a certain level of property ownership, including women who have been rich for a long time.

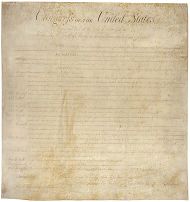

All this shows the great diversity. Moreover, many States are adopting the Bill of Rights which is a declaration of fundamental rights that guarantees the equality of men, their rights to property and fundamental freedoms being those of religion, expression and peaceful association.

In all states except South Carolina, Georgia and Virginia, there is no exclusion of blacks. In some states there are almost no slaves, while in others there are hardly any slaves at all. In some states, such as Vermont, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, slavery was abolished shortly after independence. Other states passed very gradual abolition laws. Throughout the South, however, slavery hardened after independence and slaves became more and more numerous through imports and natural growth.

At the end of the war, all these tensions came to the fore, especially as the new federation suffered an economic crisis. A stronger, more central government, of which Washington was a part, obtained a new constitutional revision.

The Philadelphia Constitutional Convention

During this convention, all are men, mostly lawyers and 19 out of 55 are large slave owners. They first of all clash over a legitimate government representing the governed and the question of who will be able to vote.

We are already forgetting the declaration of independence ensuring equality between men, the question is whether the right to vote will be reserved for landowners or whether it is a natural right of every free man. One of the other issues is slavery and the status of free slaves.

Silences, concessions and achievements of the Constitution of 1787

The U.S. Constitution is a compromise often with vague and malleable language explaining why it has survived to the present day.

In order not to break the fragile unity, the convention ratifies a constitution that begins with "we the people," which, moreover, never provides any definition of who is part of the people. On the other hand, the constitution does not mention slavery.

It is a federal constitution that gives each state its own constitution and its own definition of citizenship.

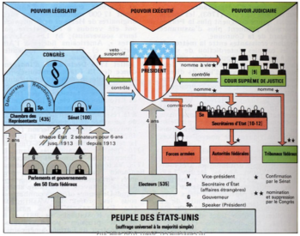

There is a lot of debate, or there is a separation of the legislative, executive and judicial powers. Delegates decide that the legislature should be bicameral with a House of Representatives and a Senate. The senate is composed of two senators per state. In contrast, the House of Representatives is a chamber that is proportional to the population of each state.

There are many debates, or there is a separation of the legislative, executive and judicial powers. The delegates decide that the legislative branch should be bicameral with a House of Representatives and a Senate. The senate is composed of two senators per state. In contrast, the House of Representatives is a chamber that is proportional to the population of each state.

In 1787, the delegates from the northern states made a huge concession to the slaveholding south, accepting that the number of representatives from the slaveholding states should correspond to the number of free inhabitants plus 3/5 of the slave population of their state. Thus they concede that a slave is worth 3/5 of a human being.

On the question of the executive, some want a very strong president with a kind of constitutional monarchy, while others oppose anything resembling a monarchy with an elected representative. It is a president with a veto over parliament and a vice-president not elected by suffrage but by an electoral college of electors.

Basically, the electoral college is for each state the number of representatives that state has in the House of Representatives plus two senators. The rules will change over the years.

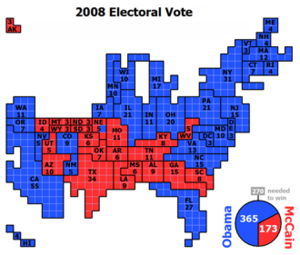

Today, on Presidential Election Day, voters elect Electoral College electors, who are the ones who will cast ballots for the election of the president and vice president. What is shocking is that every state uses the "winner takes all" method. In each state, the party that wins the majority of votes wins all the votes for president. That explains why Democrats and Republicans go where the states have the largest populations. For example, all of Florida's votes went to Obama.

U.S. citizens do not elect their president by universal suffrage; a predictor can be elected without having a majority of the votes.

In 1787, the delegates agreed to create a strong judiciary that controls Congress and can declare certain decisions unconstitutional. It is an established supreme court made up of 6 judges (now 9) appointed by the president, but elected by parliament and appointed for life. The Supreme Court is the citizens' last resort in all matters relating to constitutional law.

During this convention of 1787, the northern delegates made further concessions to the slave-owning southern states showing the racial limits of the concept of equality.

The northern states approved a clause that forced states that had already abolished slavery to return fugitive slaves from the south to the southern states. The other concession was that the northern delegates agreed to postpone the ban on importing new slaves from Africa for 20 years, i.e. until 1808. This will lead to massive imports of Africans until 1800.

At the same time, the slave trade within the United States continued until the abolition of slavery in 1865.

Much more than the compromise, it is the reduction of prerogatives in relation to the central federal state that will cause the most tension. It was the idea that the federal state could levy taxes on the whole territory, the other and the fear of the small states of losing their freedoms in relation to the large states.

It will be some time before the convention is adopted. It was only three years later, in 1790, that the most reluctant states finally signed the Constitution, but before that, amendments had to be attached to the constitution.

Bill of Rights

These amendments form the Bill of Rights[4] that protect fundamental freedoms:

- religion;

- expression;

- press;

- peaceful assembly;

- petition;

- weaponry for state defense militias; *

- protection against abuses by the state, police and justice.

The Bill of Rights is preceded by very little of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in France. However, the Bill of Rights is much more concerned with the common good and very individualistic. There are also rights that protect individuals against arbitrary action by the state.

One amendment that continues to attract a lot of ink is the freedom to bear arms: "Since a well-organized militia is necessary for security, the right of the people to keep and bear arms must not be restricted. This shows how malleable this is.

One clause limits the rights of the federal state to those contained in the Constitution. On the other hand, it must be seen that it contains fundamental freedoms that are totally incompatible with slavery; its adoption without calling slavery into question tacitly confirms the exclusion of blacks and women.

Society at the beginning of the 19th century

Territorial expansion

The United States of 1800 will expand rapidly. The Lewis and Clark Expedition crosses territories then in Indian hands[5][6][7][8][9][10]

"Lewis and Clark on the Columbia River", painted by Charles Marion Russell.

Un évènement qui va doubler le territoire et l’achat de la Louisiane à la France de Napoléon. La Louisiane avait été rendue par l’Espagne à la France, mais finalement achetée pour 15 millions de dollars à Napoléon afin de financer la guerre à Haïti[11][12][13][14][15][16][17]. C’est un territoire où il y a des postes, mais surtout des populations amérindiennes. Les États-Unis acquièrent la Floride en 1818 sans indemniser l’Espagne. D’un coup, le territoire double.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26].

Bipartisme

Très vite, les oppositions qui sont apparues lors des débats constitutionnels sont apparues entre deux partis principaux à savoir :

- les fédéralistes avec George Washington qui sont pour un gouvernement fédéral fort ainsi que de bonnes relations avec la Grande-Bretagne, opposés à la Révolution française. C’est un parti très fort parmi les marchands, les propriétaires, les artisans liés au commerce et soutenus principalement dans le nord.

- le républicains-démocrates : ils sont en faveur d’un pouvoir central limité, proche en certain aspect de la Révolution française, car pas en faveur de l’égalité raciale, opposée à la Grande-Bretagne. Ils sont forts parmi les planteurs du sud et les agriculteurs du nord.

Déjà en 1800, il y a une campagne électorale aux États-Unis avec les républicains-démocrates qui accusent les fédéralistes d’être monarchique et vendu à la Grande-Bretagne tandis que les fédéralistes accusent les républicains-démocrates d’être jacobin, anarchistes et sans-culotte.

Religion

Un « grand réveil » se fait dans toute la région de la Louisiane et avec l’avancée de la frontière aux dépens des Indiens. Ce sont de protestantismes plus militants et évangélistes qui vont faire le réveil au son de sermons avec des prédicateurs qui mobilisent des milliers de fidèles dans des camps de rencontre[27][28][29][30][31].

La participation des femmes est importante permettant l’entrée des femmes dans la politique.

Dans le Kentucky, un camp a réuni 20 000 personnes. L’autre chose importante est le développent des sectes religieuses est un phénomène qui se comprend avec l’évolution de la frontière. Pour les nouveaux migrants, dans chaque nouveau territoire conquis il y aura de la religiosité afin de créer du lien entre les différents migrants.

Ce « grand réveil » touche les femmes, mais surtout les noirs. Tout d’abord, ce sont les noirs libres qui vont former une première église noire avec l’église apostolique évangélique africaine en réponse au racisme qui commence à se développer dans les églises blanches.

Le « grand réveil » touche les esclaves déplacés de force, car c’est avec les esclaves et à coup de fouet que l’on va conquérir ces nouveaux territoires.

Vers 1810, 100 000 esclaves ont été déplacés de force vers l’Ouest. L’esclavage s’étend et se durcit. En 1770, il y avait 450 000 esclaves dans les 13 colonies, ils sont 1,5 million en 1820.

Chez les esclaves se fait un parallèle avec le peuple juif asservi en Égypte. Dans ce mouvement, des prédicateurs noirs surgissent.

La religion joue un rôle de couverture pour les femmes, mais aussi pour les esclaves qui permet à travers le fait religieux de se tailler une place dans la société.

Croissance de l’esclavage

Depuis l’achat de la Louisiane en 1803, la question de l’esclave et de l’équilibre entre États esclavagistes et non-esclavagistes croît.

Depuis 1800, 20 nouveaux États sont entrés dans l’Union. Sur les 22 États que compte l’Union en 1819, il y a un équilibre précaire entre États esclavagistes et non-esclavagistes.

En 1819, le Missouri demande son entrée dans l’Union comme État esclavagiste. S’en suit un long débat au Congrès, car la grande question est le sénat. Si on a une grande majorité d’États esclavagistes, cela signifie que la majorité des sénateurs sont esclavagistes ce qui induit que l’on pourrait introduire de force l’esclavagisme dans les États non-esclavagistes. Cela va mener à la guerre de Sécession.

Après un an de débat, le « compromis du Missouri » est trouvé avec la création d’un État libre pour avoir toujours 12 États esclavagistes et 12 États non-esclavagistes[32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44].

Le début du nationalisme étatsunien

Le renouveau du nationalisme

C’est un nationalisme qui va rejaillir en 1812 quand les États-Unis lancent une nouvelle guerre contre l’Angleterre pour agrandir leurs frontières au nord[45][46][47][48]. L’idée est de repousser les Anglais vers le nord, mais ce fut un échec.

En plus, les États-Unis n’ont pas de marine, la Grande-Bretagne impose un blocus sur les mers et les côtes des États-Unis qui va avoir pour effet de renforcer le nationalisme.

Les États-Unis ne gagnent pas un mètre carré, mais les grands perdants sont les nations indiennes battues qui ouvrent tous les territoires du sud des Grands Lacs aux nouveaux colons blancs. Toute cette partie encore très indienne va voir des massacres et des exodes.

Cette guerre a pour conséquence un regain de nationalisme et une forte confiance en soi. Des artistes commencent à représenter le mythe d’une société agraire. L’embargo anglais permet le premier développement de manufactures principalement sur la côte est des États-Unis faisant concurrence aux Anglais.

C’est aussi une époque où on se rend compte que pour contrôler le territoire on doit construire des routes et des canaux ce qui est très important pour développer la colonisation du territoire.

D’autre part, les gouvernants s’intéressent à l’éducation, à la santé publique menant à l’élaboration d’infrastructures. C’est aussi la naissance d’une architecture américaine, mais qui en fait imite le style gréco-romain. Thomas Jefferson va aller jusqu’à dessiner sa propre maison inspirée de constructions antiques.

Le nationalisme se traduit aussi par le renforcement de l’armée avec la création de l’académie militaire de West Point.

La doctrine Monroe

Cette doctrine marque le début de la vision impérialiste des États-Unis[49][50][51][52][53]. Son contexte est la victoire de la révolution haïtienne, les indépendances du Brésil et des colonies espagnoles du Mexique jusqu’au tout bas du sud de l’Amérique. Cela va attiser la convoitise de la Grande-Bretagne. C’est une déclaration unilatérale du gouvernement des États-Unis sous la présidence de Adams qui est contre toute ingérence de l’Europe dans les Amériques qui sont déjà en grande partie indépendantes en 1823.

Cette doctrine comprend la demande de la non-colonisation par des puissances européennes de l’hémisphère ouest concernant notamment l’Alaska ainsi que la non-intervention des puissances européennes dans les affaires du continent américain.

- non-ingérence des États-Unis dans les affaires de l’Europe y compris dans les colonies européennes.

À l’époque, cette doctrine passe pratiquement inaperçue, car la grande puissance de l’époque est la Grande-Bretagne qui se fait respecter dans les Amériques par sa marine royale.

La doctrine Monroe marque le début des ambitions américaines sur les Amériques puis sur le monde qui va se concrétiser au fil des décennies.

Annexes

- La doctrine de Monroe, un impérialisme masqué par François-Georges Dreyfus, Professeur émérite de l'université Paris Sorbonne-Paris IV.

- La doctrine Monroe de 1823

- Nova Atlantis in Bibliotheca Augustana (Latin version of New Atlantis)

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1998). The Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. Random House.

- Berkin, Carol (2015). The Bill of Rights: The Fight to Secure America's Liberties. Simon & Schuster.

- Bessler, John D. (2012). Cruel and Unusual: The American Death Penalty and the Founders' Eighth Amendment. University Press of New England.

- Brookhiser, Richard (2011). James Madison. Basic Books.

- Brutus (2008) [1787]. "To the Citizens of the State of New York". In Storing, Herbert J. (ed.). The Complete Anti-Federalist, Volume 1. University of Chicago Press.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2015). The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780385353410 – via Google Books.

- Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and Jay, John (2003). Ball, Terence (ed.). The Federalist: With Letters of Brutus. Cambridge University Press.

- Kyvig, David E. (1996). Explicit and Authentic Acts: Amending the U.S. Constitution, 1776–1995. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0931-8 – via Google Books.

- Labunski, Richard E. (2006). James Madison and the struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford University Press.

- Levy, Leonard W. (1999). Origins of the Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Maier, Pauline (2010). Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. Simon & Schuster.

- Rakove, Jack N. (1996). Original Meanings. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Stewart, David O. (2007). The Summer of 1787. Simon & Schuster.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, Keith (November 18, 2013). "Kerry Makes It Official: 'Era of Monroe Doctrine Is Over'". Wall Street Journal.

- Keck, Zachary (November 21, 2013). "The US Renounces the Monroe Doctrine?". The Diplomat.

- "John Bolton: 'We're not afraid to use the word Monroe Doctrine'". March 3, 2019.

- "What is the Monroe Doctrine? John Bolton's justification for Trump's push against Maduro". The Washington Post. March 4, 2019.

References

- ↑ "Bill of Rights". history.com. A&E Television Networks.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights – Facts & Summary". History.com.

- ↑ "The Bill Of Rights: A Brief History". ACLU.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights Transcript". Archives.gov.

- ↑ Full text of the Lewis and Clark journals online – edited by Gary E. Moulton, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- ↑ "National Archives photos dating from the 1860s–1890s of the Native cultures the expedition encountered". Archived from the original on February 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lewis and Clark Expedition, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- ↑ "History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark: To the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean" published in 1814; from the World Digital Library

- ↑ Lewis & Clark Fort Mandan Foundation: Discovering Lewis & Clark

- ↑ Corps of Discovery Online Atlas, created by Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576071885.

- ↑ Burgan, Michael (2002). The Louisiana Purchase. Capstone. ISBN 978-0756502102.

- ↑ Fleming, Thomas J. (2003). The Louisiana Purchase. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26738-6.

- ↑ Gayarre, Charles (1867). History of Louisiana.

- ↑ Lawson, Gary & Seidman, Guy (2008). The Constitution of Empire: Territorial Expansion and American Legal History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300128963.

- ↑ Lee, Robert (March 1, 2017). "Accounting for Conquest: The Price of the Louisiana Purchase of Indian Country". Journal of American History. 103 (4): 921–942. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaw504.

- ↑ Library of Congress: Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- ↑ Bailey, Hugh C. (1956). "Alabama's Political Leaders and the Acquisition of Florida" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly. 35 (1): 17–29. ISSN 0015-4113.

- ↑ Brooks, Philip Coolidge (1939). Diplomacy and the borderlands: the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

- ↑ Text of the Adams–Onís Treaty

- ↑ Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Del Bene, Terry. The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History. OUP USA.

- ↑ "Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819". Sons of Dewitt Colony. TexasTexas A&M University.

- ↑ Cash, Peter Arnold (1999), "The Adams–Onís Treaty Claims Commission: Spoliation and Diplomacy, 1795–1824", DAI, PhD dissertation U. of Memphis 1998, 59 (9), pp. 3611-A. DA9905078 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

- ↑ "An Act for carrying into execution the treaty between the United States and Spain, concluded at Washington on the twenty-second day of February, one thousand eight hundred and nineteen"

- ↑ Onís, Luis, “Negociación con los Estados Unidos de América” en Memoria sobre las negociaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos de América, pról. de Jack D.L. Holmes, Madrid, José Porrúa, 1969.

- ↑ Conforti, Joseph. "The Invention of the Great Awakening, 1795–1842". Early American Literature (1991): 99–118. JSTOR 25056853.

- ↑ Griffin, Clifford S. "Religious Benevolence as Social Control, 1815–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1957) 44#3 pp. 423–444. JSTOR 1887019. doi:10.2307/1887019.

- ↑ Mathews, Donald G. "The Second Great Awakening as an organizing process, 1780–1830: An hypothesis". American Quarterly (1969): 23–43. JSTOR 2710771. doi:10.2307/2710771.

- ↑ Shiels, Richard D. "The Second Great Awakening in Connecticut: Critique of the Traditional Interpretation", Church History 49 (1980): 401–415. JSTOR 3164815.

- ↑ Varel, David A. "The Historiography of the Second Great Awakening and the Problem of Historical Causation, 1945–2005". Madison Historical Review (2014) 8#4 [[1]]

- ↑ Brown, Richard H. (1970) [Winter 1966], "Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism", in Gatell, Frank Otto (ed.), Essays on Jacksonian America, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 5–72

- ↑ Miller, William L. (1995), Arguing about Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress, Borzoi Books, Alfred J. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-56922-9

- ↑ Brown, Richard Holbrook (1964), The Missouri compromise: political statesmanship or unwise evasion?, Heath, p. 85

- ↑ Dixon, Mrs. Archibald (1899). The true history of the Missouri compromise and its repeal. The Robert Clarke Company. p. 623.

- ↑ Forbes, Robert Pierce (2007). The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 369. ISBN 9780807831052.

- ↑ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Missouri Compromise" . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ↑ Howe, Daniel Walker (Summer 2010), "Missouri, Slave Or Free?", American Heritage, 60 (2): 21–23

- ↑ Humphrey, D. D., Rev. Heman (1854). THE MISSOURI COMPROMISE. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Reed, Hull & Peirson. p. 32.

- ↑ Moore, Glover (1967), The Missouri controversy, 1819–1821, University of Kentucky Press (Original from Indiana University), p. 383

- ↑ Peterson, Merrill D. (1960). The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. University of Virginia Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-8139-1851-0.

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean (2004), "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited", Journal of the Historical Society, 4 (3): 375–401

- ↑ White, Deborah Gray (2013), Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans, Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, pp. 215–216

- ↑ Woodburn, James Albert (1894), The historical significance of the Missouri compromise, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, p. 297

- ↑ "War of 1812" bibliographical guide by David Curtis Skaggs (2015); Oxford Bibliographies Online

- ↑ Library of Congress Guide to the War of 1812, Kenneth Drexler

- ↑ Benn, Carl (2002). The War of 1812. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-466-5.

- ↑ Latimer, Jon (2007). 1812: War with America. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02584-4.

- ↑ "The Monroe Doctrine (1823)". Basic Readings in U.S. Democracy.

- ↑ Boyer, Paul S., ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 514. ISBN 978-0-19-508209-8.

- ↑ Morison, S.E. (February 1924). "The Origins of the Monroe Doctrine". Economica. doi:10.2307/2547870. JSTOR 2547870.

- ↑ Ferrell, Robert H. "Monroe Doctrine". ap.grolier.com.

- ↑ Lerner, Adrienne Wilmoth (2004). "Monroe Doctrine". Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security.