The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

Tensions between the North and South of the United States over the issue of slavery have formed a deep fissure in the nation since its inception. The North, industrialised and increasingly urbanised, came to regard slavery as morally reprehensible and economically archaic. The South, on the other hand, whose agricultural economy depended heavily on slave labour, saw slavery as a fundamental and inseparable aspect of its society and economy. This divergence was exacerbated by marked economic, cultural and political differences between the two regions, highlighting the antagonism that already prevailed in the young republic. Judicial decisions played a role in exacerbating these tensions, notably the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v Sandford in 1857, which denied citizenship to African-Americans and affirmed the pre-eminence of states' rights to legislate on slavery. Opposing views on this crucial issue eventually led to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, a tragic and bloody event that remains the deadliest conflict in American history, with around 620,000 soldiers and an unknown number of civilians losing their lives.

The Civil War and subsequent Reconstruction are a key period in understanding the struggles for freedom, equality, and citizenship in American history. The 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution, adopted after the war, marked major legislative advances for the rights of African-Americans. However, these gains were largely hampered during the Reconstruction period by judicial decisions such as the Slaughter-House Cases of 1873, and by the adoption of discriminatory laws in the Southern states, known as Jim Crow laws. The implementation of these laws maintained systematic racial segregation, marking a step backwards in the evolution towards equality. This dark period of de jure and de facto inequality spanned almost a century, and its vestiges were only fully confronted with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

The Civil War and Reconstruction thus illustrate not only the conflicts and compromises that shaped the American nation, but also the complexity of the road to justice and equality. The lessons learned from this period are a reminder that social progress often requires sustained effort and struggle, and that advances can be fragile and reversible in the face of deeply entrenched societal inequalities.

The causes of war[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The causes of the American Civil War are rooted in a complex and multifaceted set of socio-economic and political factors, with slavery and its westward expansion as a central point of contention. The westward expansion of the United States exacerbated the issue of slavery, highlighting the profound differences between North and South over the expansion of slavery into the new territories. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, which allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state, in an attempt to maintain a balance between slave and non-slave states, was only a temporary solution. The Compromise of 1850, which encompassed a series of legislative measures aimed at easing tensions between the slave and non-slaveholding states, also acted as a band-aid on an open wound, without addressing the fundamental problem. In addition, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed territories to decide for themselves whether or not they would be slaveholding, led to increased violence and heightened tensions between supporters and opponents of slavery. The Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v Sandford, by denying African-Americans citizenship and affirming the right of states to legislate on slavery, inflamed passions even further. These compromises and political decisions were merely palliative measures that left the fundamental question of slavery unanswered. Instead, they served to exacerbate tensions and widen the gap between the states of the North and South, highlighting the inability of the political system to find a lasting solution acceptable to both sides. These growing tensions and inadequate compromises were reflected in the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, marking the culmination of a deep and persistent disagreement that had been brewing since the birth of the nation.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, one of the key provisions of the Compromise of 1850, became a potent symbol of the irreconcilable differences between North and South over the issue of slavery. By requiring the federal authorities, as well as ordinary Northern citizens, to contribute to the capture and return of fugitive slaves to Southern owners, the Act aroused the indignation and opposition of many Northerners. Not only was the law seen as an intolerable intrusion by the federal government into the affairs of the free states, it was also seen as a moral affront to those who opposed slavery. This led to active resistance in the North, where networks such as the Underground Railroad developed to help fugitive slaves reach safety. The law fuelled growing mistrust and animosity between the two regions, highlighting the deep moral and legal divide over the issue of slavery. The Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v Sandford in 1857 only exacerbated these tensions. By concluding that a slave remained a slave even if he resided in a free state, and by denying citizenship to African Americans, the Court not only dealt a severe blow to abolitionist efforts, but also sent a clear message that the rights and wishes of free states were subordinate to slaveholding interests. Together, the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision created a climate of heightened distrust and antagonism between North and South, shattering attempts at compromise and highlighting the nation's moral and political bankruptcy on the issue of slavery. These events cast a harsh light on the challenges and contradictions inherent in trying to maintain a fragile union in a nation deeply divided by issues of race, rights and freedom, and paved the way for the inevitable conflict that would erupt in 1861.

The issue of slavery and its expansion into the new territories was at the heart of the tensions that eventually led to the American Civil War. At the heart of this conflict was a deep and irreconcilable difference between North and South over the very nature of slavery and its role within the nation. The North, with its booming industrial economy, was increasingly moving away from reliance on slavery and saw the institution as morally reprehensible and economically backward. Many Northerners saw slavery as incompatible with the ideals of freedom and equality on which the nation had been founded. Opposition to the expansion of slavery into the new territories and states was seen as a means of containing an institution that was considered fundamentally unjust. The South, for its part, relied heavily on slavery to support its agricultural economy, particularly on the cotton plantations. For many Southerners, slavery was seen not only as a legal right, but also as a vital and inalienable aspect of their way of life and culture. The expansion of slavery into the new territories was seen as essential to the economic survival and prosperity of the South. Efforts to find common ground through legislative compromises, such as the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, only postponed the problem without solving it. Measures such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v Sandford in 1857 exacerbated tensions and eroded trust between the two sides. The inability to reconcile these fundamental differences created a rift that widened over time, going beyond legislative and economic issues to touch on the values, identities and aspirations of the two regions. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, a candidate opposed to the expansion of slavery, was the straw that broke the camel's back, prompting the Southern states to secede. The American Civil War was the inevitable outcome of a prolonged struggle between two diametrically opposed visions of what America should be. It reflected a deep and insurmountable division over fundamental issues of rights, freedom and national identity, which could not be resolved politically and were finally settled on the battlefield.

From 1850 onwards, with the adoption of the Fugitive Slave Act, part of the Compromise of 1850, the situation of fugitive slaves in the United States became dramatically more complicated. The Act obliged federal and local authorities, as well as ordinary citizens, to assist in the capture and return of fugitive slaves to their owners in the slave states. This meant that even in Northern states where slavery was outlawed, fugitive slaves were not safe and could be arrested and returned to the South. Faced with this increased threat, many fugitive slaves sought refuge in Canada, where slavery had been abolished in 1834. Canada became a destination of choice on the Underground Railroad, an organised network of secret routes and safe houses used to help slaves escape to freedom. The increase in the number of fugitive slaves seeking refuge in Canada was not only a direct result of the Fugitive Slave Act; it also had a significant impact on the abolitionist movement in the North. The stories of fugitive slaves and the efforts made to help them strengthened the determination and commitment of abolitionists. They poignantly illustrated the horrors and injustices of slavery and galvanised increased public support for the abolitionist cause. In addition, the Fugitive Slave Act provoked outrage among many Northern citizens who were not necessarily abolitionists, but who were outraged by the legal obligation to assist in the capture and return of fugitive slaves. Opposition to the Act helped to politicise the issue of slavery and deepen the divisions between North and South. The Fugitive Slave Act not only changed the dynamic for fugitive slaves themselves, it also influenced the national debate on slavery and helped shape the abolitionist movement in the crucial years leading up to the Civil War. The escape to Canada became a powerful symbol of the quest for freedom and the inhumanity of slavery, helping to fuel a cause that would eventually lead to the war to end the institution.

Frederick Douglass is one of the most emblematic and influential figures of the abolitionist movement in the United States. Born into slavery, he managed to escape at the age of 20 and devoted the rest of his life to fighting against this inhumane institution. Douglass was a gifted and charismatic speaker who could captivate and persuade his audience. He used his talent to tell his own story and give a voice to thousands of slaves who could not speak for themselves. Through his speeches and writings, he revealed the brutal realities of slavery to an audience that might otherwise only have had an abstract understanding of these atrocities. His book, "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave", published in 1845, came as a shock to many of its readers. In this detailed autobiography, Douglass describes his life as a slave, including the daily physical abuse and degradation he suffered. But more than that, he tells the story of his intellectual awakening and his yearning for freedom, which made him one of the most important thinkers and activists of his time. Douglass's account was not simply an autobiography; it was an indictment of the institution of slavery and a powerful weapon in the fight for abolition. It highlighted not only the physical cruelties of slavery but also the dehumanisation and mental enslavement of enslaved people. Douglass showed how slavery also corrupted slave owners and undermined the founding principles of American democracy. Douglass's story and impassioned speeches helped to change public opinion and rally support for the abolitionist cause. He became a living symbol of the capacity of the human spirit to overcome oppression and fight for freedom and dignity. In addition to his work as a writer and orator, Douglass was an active campaigner, supporting efforts to help fugitive slaves, working closely with other leading abolitionists and even serving as an advisor to presidents such as Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. Frederick Douglass' contribution to the cause of abolishing slavery is incalculable. He transformed his own suffering into a powerful appeal for justice and humanity, helping to set in motion the forces that would eventually lead to the abolition of slavery in the United States.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin", published in 1852, was a fundamental literary work that galvanised the abolitionist movement and profoundly influenced American public consciousness. The novel portrayed with poignant realism and deep empathy the daily life, suffering and humanity of enslaved people in the Southern states. The impact of Uncle Tom's Cabin was immediate and profound. It offered a unique and humane perspective on slavery, which enabled readers in the North, who were often far removed from the reality of slavery, to understand its horrors. The book's characters, such as Uncle Tom, little Eva, and mother Eliza, became symbols of the slavery debate, humanising slaves and eliciting empathy and sympathy from readers. The commercial success of the book was unprecedented for its time. The fact that it sold over 10 million copies in 10 years, in a population of 30 million, testifies to its immense popularity and influence. It has been translated into several languages and adapted for the stage, extending its impact beyond the borders of the United States. In the South, the novel was greeted with indignation and derision. Slave owners and supporters of the institution saw it as an unfair attack and a distortion of the reality of slavery. Some Southern states even banned the book, and many Southern critics published responses attempting to refute or minimise Stowe's allegations. What made Uncle Tom's Cabin so powerful was its ability to touch the hearts and minds of its readers. It transformed a complex political and economic issue into a human story, making the abstraction of slavery palpable and urgent. Abraham Lincoln is even reported to have said to Stowe when they met in 1862: "So it was this little lady who started this great war", illustrating the novel's perceived influence on the outbreak of the Civil War. Stowe's book is a striking example of how literature can shape public opinion and have a tangible impact on historical and social events. By giving a voice to the voiceless and exposing the brutalities of slavery, "Uncle Tom's Cabin" helped create an irresistible momentum towards the abolition of slavery and remains a lasting testament to the power of the written word.

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 marked a crucial moment in the rising tensions between North and South, exacerbating regional divisions over the issue of slavery. Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who promoted the law, intended to gain support for the construction of a transcontinental railway through the region. However, the Act had a far more profound and lasting impact on American politics. The Kansas-Nebraska Act nullified the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had established a clear line of demarcation above which slavery was prohibited in the new territories. Instead, the law adopted the principle of "popular sovereignty", allowing settlers in each territory to decide by vote whether they wanted to be a slave state or a free state. This paved the way for the possible expansion of slavery into areas that had previously been presumed to be free. The immediate effect of the law was to trigger a rush of settlers from both sides of the slavery debate to Kansas, each seeking to influence the vote on slavery in the territory. This led to a period of violence and chaos known as "Bleeding Kansas", where supporters and opponents of slavery clashed in gun battles and massacres. In the North, the law was greeted with indignation, as it seemed to favour the interests of the slave states and open the door to the expansion of slavery. Abolitionists and many other Northerners saw the Act as a betrayal of the fundamental principles of liberty and equality. The Kansas-Nebraska Act also led to the fragmentation of the Whig Party and the birth of the Republican Party, which was strongly opposed to the expansion of slavery. In the South, the Act was seen by many as a victory, allowing the possible expansion of slavery and strengthening their influence in the federal government. However, the violence that followed in Kansas and the fierce opposition in the North demonstrated that the law was far from an acceptable compromise. In the end, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was not just a legislative act to facilitate the construction of a railway. It became a symbol of the bitter struggle between North and South over the future of slavery in the United States, exacerbating divisions and helping to lay the foundations for the Civil War that would break out less than a decade later.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, by repealing the Missouri Compromise, injected new urgency and volatility into the national debate over slavery. By replacing the bright line established by the Compromise of 1820 with the principle of "popular sovereignty", the act left it to the settlers of each new territory to decide whether or not they would allow slavery. This policy opened up the possibility of slavery expanding far beyond its previous boundaries, causing widespread consternation and anger in the North. The question of the balance between free and slave states had long been at the heart of American politics, and the Missouri Compromise had provided an apparently stable, if fragile, solution. The Kansas-Nebraska Act shattered this balance, prompting both sides to fight with greater determination to influence the future of the newly opened territories. In the North, the Act was seen as a blow to the principles of freedom and equality, and galvanised the abolitionist movement. The possibility of slavery being extended to Canada was alarming to many Northerners who saw slavery as a corrupt and declining institution and feared its expansion. In the South, the Act was received more favourably, but it also rekindled fears that the federal government might seek to limit or eliminate slavery. The possibility of an expansion of slavery was welcomed by many as an opportunity to strengthen the Southern economy and culture, but the violent Northern opposition to the Act also showed that the debate over slavery was far from resolved. In the end, the Kansas-Nebraska Act did not ease national tensions, but rather exacerbated them, fuelling hostility and mistrust on both sides. By reopening the question of the balance between the free and slave states, the Act highlighted the depth of regional and ideological divisions and set the nation on the road to civil war. The debate over slavery, far from being resolved or contained by legislative compromise, flared up into a confrontation that would ultimately tear the nation apart.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act, by leaving the question of slavery in the hands of the settlers themselves, triggered a competing scramble between pro- and anti-slavery groups to populate the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. The struggle to determine the status of these territories quickly escalated into violence, leading to the period known as "Bleeding Kansas." During this period, armed militias from each side clashed, and incidents such as the Potawatomi Creek Massacre, perpetrated by abolitionist John Brown, splattered the nation with blood. Street battles, assassinations and acts of terrorism were commonplace. Tensions even spilled over into Congress, where, in one famous episode, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina violently assaulted Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts with a cane, in response to an anti-slavery speech. "Bleeding Kansas" not only highlighted the inability to peacefully resolve the issue of slavery through legislative compromise, but also dramatically demonstrated that the division over slavery was not simply an abstract political dispute. It was rooted in deeply held values and regional identities that were ready to be translated into armed violence. The brutality of "Bleeding Kansas" shocked the country and made the debate about slavery even more intransigent and polarised. It also foreshadowed the larger-scale violence that was to come. The failure of the Kansas-Nebraska Act to resolve the issue of slavery, and the bloodshed that ensued, were key milestones on the road to the American Civil War. It was no longer a question of whether the North and South could find common ground; the question was how violent the conflict would become. "Bleeding Kansas was a grim answer to that question, a foreshadowing of the terrible struggle that would soon engulf the entire nation.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act, passed in 1854, marked a major turning point in the growing conflict between the North and South of the United States over the issue of slavery. By repealing the Missouri Compromise and leaving it to the settlers of these new territories to decide whether to permit or prohibit slavery, it sparked a race between pro-slavery and abolitionists for a majority of votes. The rivalry quickly degenerated into a series of violent confrontations known as "Bleeding Kansas", further exacerbating tensions between the Northern and Southern states. Both sides, convinced of the justness of their cause, invested significant resources in the effort to colonise the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and influence the vote on slavery. Many Northern abolitionist groups financed and organised the migration of anti-slavery settlers, while Southern slave owners and their allies did the same for pro-slavery supporters. The result was a series of brutal and bloody clashes that left their mark on public opinion at the time. From street battles to murder to acts of terrorism, Bleeding Kansas became a symbol of the growing and irreconcilable divide between North and South. It also showed that the issue of slavery could no longer be resolved by legislative compromise and was ready to erupt into a full-blown confrontation. "Bleeding Kansas not only further polarised the country, but also foreshadowed the violence and intensity of the conflict to come. Inflamed passions, divergent interests, and the inability to find a peaceful solution to the issue of slavery ultimately led to the American Civil War. The events in Kansas and Nebraska were a preview of the national cataclysm that was to follow, a warning that the divisions between North and South had deepened to the point where war seemed inevitable.

The crisis caused by the Kansas-Nebraska Act highlighted the deep divisions within the Whig party, exacerbating existing tensions and accelerating its decline. Already weakened and divided on various national issues, the party was at a crossroads on the crucial question of slavery. In the North, many Whigs were increasingly opposed to slavery and found a voice in the new Republican party, which had formed in direct opposition to the expansion of slavery into the new territories. These Northern Whigs felt increasingly disconnected from their Southern counterparts, who supported the expansion of slavery and opposed attempts to end it. The Kansas-Nebraska Act exacerbated this division, forcing the party to take a stand on an issue that cut directly through its ranks. Attempts to find common ground or formulate a coherent party position were futile, and the Whigs found themselves torn apart by diametrically opposed interests and beliefs. The result was the disintegration of the Whig party as a viable political force. Unable to overcome its internal divisions and formulate a coherent response to the slavery crisis, the party collapsed. Many of its members in the North joined the ranks of the nascent Republican Party, while those in the South found refuge in the Democratic Party or other pro-slavery political movements. The collapse of the Whig Party is a testament to the way in which the issue of slavery dominated and shaped American politics in the run-up to the Civil War. It also reflects the inability of the political system of the time to manage or resolve this divisive issue, highlighting the fragility of political compromise and the power of moral and ideological conviction. The end of the Whig Party marked the end of an era in American politics and signalled the emergence of a new political landscape in which the struggle for and against slavery would play a central role.

In addition to the heightened tensions around the issue of slavery, the Whig Party was also grappling with the emerging issue of immigration. During the 1840s and 1850s, a massive influx of Irish and German immigrants had arrived in the United States, provoking a diverse reaction within the party. In some areas, particularly the urban North, these newcomers were seen as an essential workforce and a vital part of the growing community. Others, however, saw them as a threat to the existing culture and social order, fearing that they would take jobs and influence American political and religious culture. This division over immigration added to the already existing fissures within the Whig party over slavery, and attempts to reconcile these divergent views failed. Tensions crystallised, and the party found itself unable to forge a consensus or a unified vision. The collapse of the Whig Party was not just the result of a single issue, but rather the consequence of a series of deep and irreconcilable divisions. The party was unable to navigate the choppy waters of these national debates and ultimately collapsed under the weight of its internal contradictions. As a result, the political landscape was reorganised, with the rise of the Republican party in the North, which strongly opposed slavery and sought to limit its expansion, and the consolidation of the Democratic party in the South, which actively supported states' rights to maintain and expand the institution. This polarisation of political parties around the issue of slavery ultimately contributed to the inevitability of the Civil War, a struggle that would determine not only the future of slavery in the United States, but the very character of the nation.

The presidential election of 1856 highlighted the simmering tensions in the United States over the issue of slavery. James Buchanan, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, won the election, but his term was marked by controversy and division. Although not a slave owner himself, Buchanan was seen as having pro-Southern sympathies and was prepared to conciliate with Southern states that defended the institution of slavery. The political polarisation of the time was intense. The campaign was marked by inflammatory rhetoric, unrest and even violence, reflecting the country's deep divisions over slavery, states' rights and the future of the nation. Buchanan inherited a tense situation with the Bleeding Kansas affair, where clashes between supporters and opponents of slavery had become increasingly violent. Instead of resolving the tensions, his administration often found itself exacerbating them. His attempts at compromise were viewed with suspicion by both sides, and his actions often seemed to favour the interests of the slaveholding South. The election of 1856 was a harbinger of the coming collapse of the Union. It showed that it was increasingly difficult to find common ground on fundamental issues and revealed how personal and passionate divisions had become. Buchanan, despite his best efforts, failed to heal these divisions, and the country continued to march inexorably towards civil war. The fragility of the national consensus and the rise of partisan passions in that election were a harbinger of the devastating conflict to come.

The presidential election of 1856 was marked by deep divisions, not only on the issue of slavery, but also on other key issues such as immigration. The campaign highlighted these divisions, with three main candidates representing three different points of view. Frémont was an exciting choice for the young Republican party. A famous explorer and military officer, he was strongly opposed to the expansion of slavery into the western territories. His campaign slogan, "Free Soil, Free Men, and Frémont", resonated with many Northerners who opposed slavery. The Democrats were divided on the issue of slavery, and Buchanan's nomination reflected an attempt at compromise. Although he was from Pennsylvania, a free state, he had pro-Southern sympathies and was prepared to appease the slave states. He won the election, but his term in office was marked by continued polarisation. The American Party was strongly opposed to immigration, particularly Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany. Fillmore, a former president, was the party's candidate, seeking to capitalise on the anti-immigrant fears and prejudices of the time. The election of 1856 was a pivotal moment in American politics, reflecting the growing tensions and deep divisions that would eventually lead to the Civil War. The result showed how polarised the nation was, with the North supporting Frémont, the South supporting Buchanan, and Fillmore winning votes in the border states. The issues of slavery and immigration were central to the debates, and no candidate was able to create a national consensus on these controversial issues.

The presidential election of 1856 was marked by intense political polarisation and violent incidents. Tensions over the issue of slavery raged, particularly in the border states where the stakes were highest. James Buchanan, the Democratic candidate, won the election, but by a narrow margin. His victory did not ease tensions between North and South, and the issue of slavery remained a major source of conflict and division. Regional and political divisions over slavery continued to grow, undermining any attempt at compromise or reconciliation. The country was on a dangerous trajectory, and the rift of 1856 simply reinforced the fissures that would eventually lead to civil war in 1861. Buchanan's victory was a symbol of this fracture, revealing a nation deeply divided and unable to find common ground on a fundamental issue of justice and human rights.

The administration of James Buchanan, which took office in 1857, found itself deeply mired in the issue of slavery. Despite the hopes of some that his tenure might bring some relief, Buchanan proved unable to resolve the issue or reduce the growing tensions between North and South. Disagreements over slavery festered, compromises proved elusive, and regional and political divisions deepened. The country continued to move inexorably towards conflict, and the failure of the Buchanan administration to find a peaceful solution to the issue of slavery helped lay the foundations for the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. This period has become emblematic of how political and societal divisions can become inextricable and degenerate into violent conflict. The Buchanan administration's inability to resolve the issue of slavery was a grim reminder that leadership, understanding and a willingness to compromise were essential to prevent internal divisions from becoming insurmountable fractures.

The presidential election of 1860 was a major turning point in the rising tensions that eventually led to the American Civil War. The Democratic Party was deeply divided over the issue of slavery, with Northern and Southern factions unable to agree on a single candidate. Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas, while the Southern Democrats, unhappy with Douglas's stance against the expansion of slavery, nominated John C. Breckinridge as their candidate. In addition, a faction of conservative Democrats and former Whigs formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell as their candidate. This deep division within the Democratic Party paved the way for the Republican Party, which had been formed six years earlier on a platform strongly opposed to the expansion of slavery into the new territories. The Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer and politician from Illinois, as its candidate. The election took place in a climate of extreme tension and passion, with fiery rhetoric on both sides. Lincoln's victory, despite winning only a minority of the popular vote, was a direct result of the split in the Democratic Party. Lincoln's victory provoked anger and outrage in the South, where he was seen as a direct threat to the institution of slavery. Shortly after his election, several Southern states began to take steps towards secession, triggering a constitutional crisis that eventually led to civil war.

The nomination of Abraham Lincoln by the Republican Party in 1860 is a powerful reflection of the American dream. His story is one of a man born in a log cabin to a poor Kentucky family, who through intelligence, hard work and determination rose to one of the highest offices in the land. Lincoln had little formal education, but he was hungry for knowledge and learning. He taught himself law and became a respected Illinois lawyer and politician. Despite his humble origins, or perhaps because of them, he was able to connect with people in a way that touched them deeply. As a candidate, his relative obscurity outside Illinois was an advantage in such a politically charged time. He didn't have a long history of taking positions on controversial issues that could be used against him, and his ability to articulate a vision that transcended regional and partisan divisions contributed to his appeal. Lincoln embodied a vision of America where opportunity was available to all, regardless of background. His personal story and rise to the presidency were an inspiration to many and a symbol of the promise inherent in American democracy. This added particular weight to his leadership at a time when the nation was on the verge of tearing itself apart.

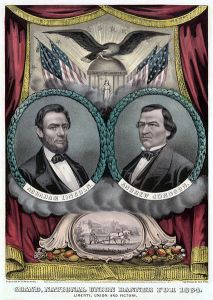

In nominating Hannibal Hamlin as its vice-presidential candidate, the Republican Party sought to balance the presidential ticket and strengthen its appeal among different groups of voters. Hamlin, a senator from Maine, had a reputation as a moderate Republican and was known for his opposition to the expansion of slavery, while being seen as less radical than some other Republicans. Hamlin's selection helped to give the Republican ticket a more national character. Whereas Lincoln came from the West, from the new state of Illinois, Hamlin came from New England. This helped the party to unite different parts of the North around the Republican candidate. The combination of Lincoln and Hamlin proved effective in a complex and divided election. With the Democratic Party divided and multiple candidates, the Lincoln-Hamlin ticket managed to unite enough votes to win the election, despite fierce opposition from the South and heated debates over the issue of slavery and its expansion. Lincoln's victory triggered a series of events that eventually led to the secession of several Southern states and the Civil War.

The election of 1860 was a major turning point in American history. With the victory of Abraham Lincoln, tensions between North and South, already exacerbated by years of conflict over slavery, reached a breaking point. Lincoln's vision of a united country where slavery would not be extended to new territories was in total opposition to the interests of the Southern states, whose economies were heavily dependent on the institution of slavery. Lincoln's victory prompted seven Southern states to secede and form the Confederate States of America even before his inauguration. Four more states followed suit after the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, triggering the Civil War. During the war, Lincoln demonstrated exceptional leadership, guiding the nation through one of its darkest and most tumultuous periods. Despite the military, political and social challenges, he remained firmly committed to the Union and the cause of freedom. Lincoln's presidency culminated in the adoption of the 13th Amendment in 1865, definitively abolishing slavery in the United States. His Gettysburg Address, Emancipation Proclamation and Second Inaugural Address remain fundamental texts of American democracy and the fight for equality and human dignity. Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, shortly after the end of the war, marked a tragic end to his presidency, but his legacy continues to influence the nation and the world. He is often cited as one of the greatest presidents in American history for his role in preserving the Union and ending slavery.

Abraham Lincoln was strongly opposed to the expansion of slavery into new territories and states. However, he was not initially in favour of the immediate abolition of slavery in states where it already existed. He believed that the expansion of slavery would be detrimental to white settlers seeking to establish themselves in the new territories. Lincoln expressed views that could be considered racist by modern standards. He repeatedly stated that he did not believe that blacks and whites were equal in every way. He did, however, firmly believe in the equal protection of natural rights, as defined in the Declaration of Independence. As the Civil War progressed, Lincoln saw the emancipation of slaves as a strategic means of undermining the Southern economy and as a moral objective. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 declared slaves in the rebellious states free, and Lincoln worked actively for the passage of the 13th Amendment, permanently abolishing slavery. At various times in his career, Lincoln considered the possibility of colonising freed blacks in Africa or the Caribbean. He considered that this might be a solution to the racial problem in the United States, but these ideas were eventually abandoned. Towards the end of his life, Lincoln began to think about how black people could be integrated into American society after the war. He even suggested that some blacks, particularly veterans and the highly educated, could be given the right to vote. Lincoln's views on race and slavery must be understood in the context of his time, which was marked by deep-rooted racial prejudice and political and social divisions. His commitment to the Union and to the ideal of a republican democracy in which all men are created equal remains at the heart of his legacy.

Lincoln believed that slavery was morally wrong, a violation of the principles of the Declaration of Independence. He asserted that all men are created equal and have a right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. He saw slavery as a stain on these ideals, incompatible with the nation's fundamental values. Lincoln was also strongly opposed to the extension of slavery into the new territories and states. He believed that allowing slavery in these areas would hinder the development of a free and democratic society, undermining the principles on which the nation was founded. However, Lincoln's views on African Americans were more nuanced. Although he recognised their humanity, he did not believe they were immediately ready to exercise the full rights of citizenship. He envisaged gradual assimilation into white society rather than the immediate granting of full civil rights. Lincoln was not an abolitionist in the traditional sense. He did not advocate the immediate abolition of slavery, particularly in states where it already existed. He focused more on preventing its spread, while recognising that slavery was legal where it had already been established. Lincoln's views on slavery and the rights of African Americans evolved over time, particularly during his term as President. He eventually took decisive action to end slavery and began to consider the possibility of granting some African Americans the right to vote. These nuances in his thinking reflect the challenges and contradictions of his time, and his willingness to navigate through them in a pragmatic and thoughtful way.

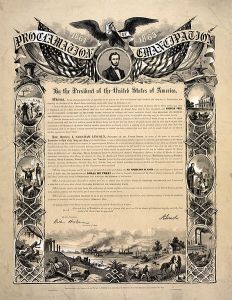

In 1863, Lincoln took the historic step of signing the Emancipation Proclamation. Although primarily an act of war to weaken the Confederate States, the proclamation had profound symbolic and practical significance. It declared free all slaves in Confederate territories still in rebellion against the Union, and changed the nature of the Civil War by making the fight against slavery a central objective. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln continued to promote the rights of African Americans by strongly supporting the adoption of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery throughout the United States, without exception. Lincoln used his influence and political power to push the amendment through, seeing it as an essential step towards the realisation of the nation's ideals of freedom and equality. The evolution of Lincoln's views during his presidency reflected a growing understanding of the importance of emancipation and equal rights. Although his views were more nuanced and conservative at the beginning of his political career, his actions as President show a growing determination to end the institution of slavery and promote civil rights for African Americans. Lincoln's presidency was marked by bold and progressive measures in the field of civil rights. His decisions had a profound and lasting impact, not only by ending slavery, but also by laying the foundations for future efforts to ensure equality and justice for all American citizens. His leadership and vision continue to be a source of inspiration and a model for future generations.

Secession and the outbreak of the Civil War[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

1860 - 1861[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The election of 1860 saw the victory of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican president, at a time of heightened tensions between North and South. Lincoln, known for his opposition to the expansion of slavery, became President without a Republican majority in Congress or on the Supreme Court. This raised deep concerns among Southern leaders. For many in the South, Lincoln's election symbolised an imminent threat to the institution of slavery. Slavery was not only essential to the economy of the South, it was also deeply rooted in its social and cultural structure. The fear that Lincoln's presidency might lead to the abolition of slavery prompted several Southern states to consider drastic measures. The Southern response to Lincoln's election was swift and determined. Several states, including South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida and others, took the unprecedented step of seceding from the Union. These acts of secession were driven by the belief that Lincoln's administration posed an existential threat to their way of life. The secession of the Southern states triggered a constitutional and political crisis. Despite attempts at compromise and negotiation, the divisions between North and South were too deep to be overcome. The situation continued to escalate until conflict erupted in April 1861 with the attack on Fort Sumter, marking the start of the Civil War. Lincoln's election in 1860 was more than just a political event. It became the catalyst for a series of events that tore the nation apart and led to the deadliest war in American history. The issues, fears and ideologies at stake in this election resonated deeply across the country, and the repercussions of this moment were felt well beyond the end of the Civil War.

The rapid and consecutive secession of the Southern states following the election of Abraham Lincoln was a key event that precipitated the American Civil War. South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union on 20 December 1860, a bold move that came just weeks after Lincoln's election. The decision was prompted by fears that Lincoln's presidency would lead to restrictions on slavery, which was essential to the economy of the South. The secession of South Carolina was closely followed by that of other Southern states. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia and Texas also seceded and joined South Carolina to form the Confederate States of America. This coalition was a strong statement against Lincoln's administration and its views on slavery. Lincoln and the Northern States did not recognise the legitimacy of the Confederacy. They considered that the seceding states were still part of the United States and that their acts of secession were illegal. This created a political and constitutional impasse, and tensions rose rapidly. The disagreements over secession and the legitimacy of the Confederacy crystallised into a military conflict. Hostilities erupted in April 1861 when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, a Union fort in South Carolina. This marked the beginning of the Civil War, a bloody struggle that would last four years. The secession of the Southern States and the formation of the Confederacy are crucial events in American history. They illustrate the deep divisions and intense passions that defined this period. The speed with which these states left the Union and the intransigence of the North in its response created an explosive situation where war was almost inevitable. The resulting Civil War had a lasting impact on the nation, shaping its collective memory and identity to this day.

The Constitution of the Confederacy, which governed the Confederate States of America during the Civil War, was similar to that of the United States in many respects, but it also had some notable differences. The Constitution of the Confederacy largely mirrored the structure and language of the Constitution of the United States. It established a federal government with executive, legislative and judicial powers. As in the US Constitution, it recognised individual liberties and delimited the powers of government. One of the key differences between the two constitutions was the balance of power between the federal government and the states. The Confederation Constitution gave more power to the individual states, reflecting the dominant political philosophy in the South at the time. The states had the right to regulate internal trade and had more control over their internal affairs. The Constitution of the Confederacy explicitly protected the institution of slavery. It prohibited the federal government from interfering with slavery and guaranteed the rights of slave owners in the territories. This reflected the economic and social importance of slavery in the South and was in direct contrast to the abolitionist tendencies of the North. Jefferson Davis, a large Mississippi slave owner and veteran of the Mexican-American War, was elected President of the Confederacy. He had previously been a United States Senator and Secretary of War. As a moderate Democrat, Davis served as President of the Confederate States of America from 1861 until the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865. The Constitution of the Confederacy illustrates the values and priorities of the South during this period. It highlights the tensions and disagreements that led to the Civil War, including the balance of power between the federal government and the states, and the controversial issue of slavery. The election of Jefferson Davis as President also reflects the values and interests of the South during this crucial period in American history.

1861 - 1863[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The context and events described form a crucial sequence in American history, leading to the outbreak of the Civil War. In his inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln approached the secession crisis with a mixture of firmness and conciliation. He declared that the seceding states were not enemies, but rather friends who had made a bad decision. He stressed: "We are not enemies, but friends." While insisting on the need to maintain the Union, he also warned that the federal government would use force if necessary to defend federal property and maintain the authority of the government. Reacting to Lincoln's position, the Confederate States quickly mobilised an army of volunteer soldiers. They prepared to defend their secession and the principles behind it. Tensions continued to rise, with the South determined to defend its right to self-determination. In April 1861, tensions came to a head when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, which was still under Federal control. This attack not only marked the beginning of the Civil War, but also posed a direct challenge to the federal authority that Lincoln had pledged to defend. Lincoln responded by calling up 75,000 volunteers to help quell the rebellion. The Civil War was now underway, a fratricidal struggle that would last four years, with massive loss of life and destruction on both sides. This period in American history is a poignant illustration of how profound political and ideological differences can lead to armed conflict. Lincoln's words and actions during this period reflect a mixture of determination to maintain the Union and a desire for reconciliation. However, the differences were too deep and war was inevitable. The Civil War left a lasting imprint on the nation, influencing its trajectory for generations to come.

The attack on Fort Sumter, in South Carolina, was the start of the American Civil War. The assault on Fort Sumter, orchestrated by Confederate forces, marked the bloody beginning of the American Civil War. After laying siege to the fort, Confederate forces opened fire on 12 April 1861, following several failed attempts to negotiate a peaceful surrender. The Union garrison at Fort Sumter, led by Major Robert Anderson, held out for 36 hours before agreeing to evacuate the fort. Lincoln's swift response, calling for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion, and the rapid mobilisation of armies in the Northern and Southern states, sealed the official start of the American Civil War. This fratricidal conflict was to last four years, defining a pivotal period in American history and leaving deep scars in the national consciousness.

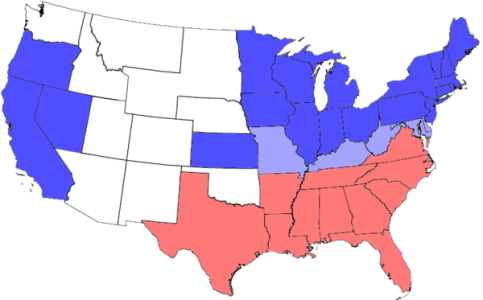

Following the outbreak of the American Civil War, the political and strategic dynamics in the border and slave states were extremely complex. Following the outbreak of the Civil War, four states quickly joined the Confederacy: Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee. Nevertheless, several states where slavery was legal, including Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia and Delaware, made the crucial decision to remain in the Union. These border states were strategically important, as they were at the junction of the Confederacy and the Union, and their choice to remain loyal to the Union undermined the strength of the Confederacy. In addition, the lack of unanimous support for the Confederate cause from all the slave states undermined its position, making it clear that the Confederacy did not represent the full interests of those states whose economies and societies were linked to the institution of slavery.

At the start of the Civil War, the balance of power between North and South seemed to be in favour of the Union, but the reality on the ground was much more nuanced. The Union had several advantages that seemed to promise a swift victory over the Confederates. The population of the North was almost twice that of the South, and it held the majority of the country's industrial production and transport infrastructure. This included a well-developed network of railways, which made it easy to move troops and supplies across the country. In addition, the North had a surplus of food and grain, vital for feeding an army in the field. Nevertheless, the South had its own advantages. Notably, a higher percentage of its population was eligible for military service, and its troops were often better trained and more determined. Southern military leaders were also renowned for their skill and ingenuity. As a result, what initially appeared to be a war that would be quickly won by the North turned into a long and bloody struggle. The Southern forces resisted fiercely, and the North had to wage a prolonged campaign to defeat the Southern rebellion. Initial expectations of a quick victory were replaced by the harsh reality of a conflict that cost lives and resources in devastating ways.

The organisation and composition of the armies at the start of the American Civil War reflected the cultural and geographical differences between the North and the South, and these differences had a significant impact on the conduct of the war. The Union army was predominantly composed of city dwellers, many of whom had no military experience and no understanding of the realities of war. Their lack of familiarity with the difficult terrain of the South and the guerrilla tactics used by the Confederates often put the Union at a disadvantage. Union troops were also less motivated to fight at first, as many saw the war as a battle for principle rather than for home or family. In contrast, Confederate troops were predominantly made up of country men, many of whom were farmers and peasants. Their knowledge of the Southern terrain and experience in hunting and outdoor survival proved to be valuable assets. In addition, many were highly motivated to defend their homes and families, which often led to greater determination and resilience in battle. These differences in troop composition and motivation influenced the way the war was fought, and contributed to the challenges faced by the Union in its efforts to invade and subdue the South. The resilience and determination of Confederate troops were key factors that prolonged the war and made Union victory more difficult to achieve.

The American Civil War was not limited to land battles; it was also marked by major naval conflicts. The Union's maritime strategy centred around blockading Confederate ports, a tactic known as the "Anaconda Plan." This strategy aimed to strangle the Southern economy, preventing the import of essential supplies and weapons, and the sale of products such as cotton to foreign nations. The Union naval blockade was incredibly effective in reducing the resources available to the Confederates. Although some ships managed to break the blockade, most attempts were unsuccessful, and the blockade gradually weakened the Confederacy's ability to wage war. The effectiveness of the blockade was increased by the technological superiority of the Union navy, including the use of armoured ships. In addition to the blockade, the Union pursued a land strategy aimed at occupying key border states such as Kentucky, Missouri and West Virginia. Control of these states allowed the Union to secure vital transportation routes and resources, further limiting the South's capabilities. The combination of these strategies was crucial to the Union's eventual victory. The naval blockade starved the South of vital resources, while control of the border states strengthened the Union's position. Together, these efforts helped erode the Confederacy's ability to continue the war, ultimately leading to its defeat.

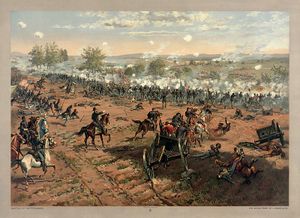

The early months of the American Civil War caught many in the North unprepared. The resilient and skilful opposition of the Confederacy belied expectations of a quick and easy Union victory. The Civil War stands out as one of the first modern wars, marked by the use of advanced tactics and technology. The weapons used in the war were more accurate and deadly than ever before. Rifled muskets, which were more accurate than the smooth-bore muskets of earlier wars, changed the dynamics of combat. Iron-hulled ships, such as the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia, revolutionised naval warfare. Landmines, then called "land torpedoes", were used to protect trenches and fortifications. These technological innovations, combined with tactics that had not yet evolved to take account of these new weapons, led to extremely bloody and destructive battles. Conflicts such as the Battle of Antietam and the Battle of Gettysburg became synonymous with unimaginable carnage. The war also saw the emergence of total war, where the line between combatants and civilians was often blurred. Sherman's March to the Sea is a striking example, where the Union army deliberately targeted Georgia's civilian infrastructure and economy to break the will of the Confederacy to continue fighting. The Civil War would be long and brutal, lasting four difficult years and costing the lives of around 620,000 soldiers, not counting the many civilian casualties. This unprecedented conflict left an indelible mark on American history and continues to be a subject of study and reflection.

The American Civil War had a devastating impact on the South. The majority of battles were fought on Confederate territory, and Union military strategies, such as Sherman's campaign in the Carolinas and his march to the sea through Georgia, targeted the civil and economic infrastructure of the South. The Confederacy won notable victories early in the war, including the first battles of Bull Run and the Maryland campaign. However, these victories were not enough to gain foreign support or to deal a decisive blow to the Union. The war had serious consequences for the Southern economy. Union blockades severely limited Southern cotton exports, and the Confederacy's agrarian economy, largely dependent on slavery, collapsed with the abolition of that institution. Infrastructure, including railways and factories, was destroyed during the military campaigns, and post-war reconstruction was a slow and difficult process. In addition, the loss of slave labour and the destruction of the plantations radically changed the socio-economic structure of the South. The transition to a wage-labour system proved complicated, and Reconstruction, the post-war period, was marked by poverty, political instability and persistent racial tensions. By comparison, the North also suffered losses, but its industrial economy actually benefited from the war in many sectors. The armaments, steel and railway industries grew rapidly, and the North quickly resumed its economic expansion after the end of the war. The disproportionate impact of the war on the South left scars that are still visible today in certain economic and social aspects of the region. The Civil War remains a sensitive and complex subject, and its legacy continues to influence American culture and politics.

The economy of the South during the American Civil War was profoundly affected by the Union blockade, the disruption of internal trade and the war itself. The Union naval blockade had a devastating effect on the Southern economy. Cotton, which was the South's main export and a major source of revenue, could no longer reach foreign markets. Major ports such as Charleston, Savannah, and Mobile were blocked, drastically reducing the South's trade revenues. Financing the war was an enormous challenge for the Confederacy. Without a strong banking system and with limited access to foreign loans, the Confederacy was forced to print money to finance the war. This led to hyperinflation, with rates reaching astronomical levels. Inflation made daily life extremely difficult for the citizens of the South, with prices for basic goods soaring. The war itself caused significant damage to the South's infrastructure and agrarian economy. Military campaigns, such as Sherman's march through Georgia, deliberately targeted the economic infrastructure. Fields were destroyed, railways were sabotaged, and resources were depleted. The South lacked the industrial capacity of the North. Without factories to produce arms, munitions, and other supplies, the South had to rely on imports that were reduced by the blockade. The economic hardships were felt throughout Southern society. Shortages of food and essential goods led to riots in some cities. The war also had a lasting impact on the Southern ruling class, with the destruction of the slave-based economy. The economic challenges faced by the Confederacy during the Civil War were a key factor in its defeat. The war devastated the Southern economy, and the effects were felt long after hostilities had ended.

Substitute industrialisation in the South during the American Civil War was a crucial phenomenon that demonstrated both the ingenuity and the limitations of the South. Faced with a naval blockade that hampered its imports, the South had to turn to its own resources. This led to a small-scale development of manufacturing, mainly concentrated in textiles, arms and munitions. Factories such as the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, played a key role in this effort. Despite these efforts, alternative industrialisation in the South was far from sufficient to meet the needs of the war. The region lacked the infrastructure to support large-scale production. There was a crying lack of resources such as coal and iron, which were essential for industrial production. In addition, most of the skilled workforce was concentrated in the North, making it difficult for industry to develop rapidly in the South. The lack of sufficient industrial capacity had a major impact on the Southern war effort. Shortages of ammunition, arms, clothing and other necessary supplies limited the ability of the Confederate armies to fight a prolonged war. Although the attempt at alternative industrialisation was largely a failure as far as the war effort was concerned, it laid the foundations for increased industrial development in the South after the war. The need for economic independence was recognised, and there was a move towards a more diversified and industrialised economy in the reconstruction period. Substitute industrialisation in the South during the Civil War was a response to the need to overcome the Union blockade, but it was insufficient to fully support the war effort. Limitations in resources, skills and infrastructure were major factors in the South's inability to compete industrially with the North, contributing to the defeat of the Confederacy.

The American Civil War had a profound impact on the social and political structures of the time. The war overturned traditional gender roles. While men went off to fight, women took on responsibilities previously reserved for men. They managed farms, plantations, businesses and even certain administrative posts. Many women also served as nurses, supporting the war effort. Mobilisation for the war required close coordination and led to increased centralisation of power at federal government level. This limited the powers of the states and set a precedent for a stronger federal government even after the war was over. The centralisation of power and changes in gender roles also contributed to the erosion of some of the traditional patriarchal structures. As women took on new roles and responsibilities, they began to demand greater rights and autonomy. The traditional idea of the white woman at home was seriously challenged. Many women had to work outside the home to provide for their families, which shattered the gender norms of the time. The Civil War also led to the emancipation of slaves and the struggle for civil rights, laying the foundations for Reconstruction and changes in America's social structure. The American Civil War was a turning point in American history, not only in terms of politics and military strategy, but also in terms of social and cultural structures. It laid the foundations for modernisation and ushered in profound changes in American society that would continue to resonate for decades. The war was a catalyst for change, challenging traditional norms and paving the way for a more egalitarian and centralised America.

The Civil War certainly amplified the social and economic divisions within the South, particularly by accentuating the inequalities between the rich and poor classes. Wealthy individuals often had the means to avoid military service by paying someone to take their place. This allowed the rich to continue to live comfortably while the poor bore the burden of combat. Newspaper notices offering to pay for replacements reflected this practice. As the war intensified, the Confederation was forced to introduce conscription, making military service compulsory for many men. However, exemptions were often granted to the wealthy or those with particular skills, such as doctors and teachers. This left many of the poor with no choice but to serve, while allowing the rich to continue to avoid conscription. This inequality led to resentment and tensions between social classes. Many in the lower classes felt that the war was a cause of the rich, but it was the poor who paid the price. The feeling that the war was a "rich war and a poor struggle" took root. The Southern economy, already struggling because of the Union blockade and dependence on cotton, deteriorated further. Prices soared, and the poor were hit hardest. The rich, with their resources and connections, were often better able to cope with these economic challenges. The civil war highlighted and exacerbated existing social and economic divides within the South. Inequalities between rich and poor increased, with lasting consequences for Southern society. The unequal conscription system and the evasion of military service by the wealthy created deep resentment and helped shape the complex legacy of the war in the South. The conflict left social scars that persisted long after the war ended, fuelling tensions and class divisions.

The gap between rich and poor widened as the Civil War progressed, and this disparity had significant consequences in the South. Wealthy individuals often had the means to avoid military service by buying substitutes. They advertised in newspapers for someone to take their place in the army. Those who could afford to pay were exempted from service, leaving the less fortunate to bear the burden of combat. The Confederation was forced to introduce conscription, making military service compulsory for all able-bodied men. However, exemptions were granted to the wealthy or those with important skills. Particularly controversial was a law that exempted men who owned more than 20 slaves. These inequalities exacerbated the social and economic divide and led to resentment among the poor. The impression that the war was a "rich war and a poor struggle" took root. This led to growing discontent and a perception that the war was being fought by the poor for the benefit of the rich. Inequality in military service also led to a gradual weakening of white Southern unity around the defence of slavery. The poor, who often did not own slaves, began to question why they should risk their lives for an institution that did not directly benefit them. The disparity in military service during the Civil War revealed and accentuated existing social and economic divisions within the South. The resentment and frustration engendered by the evasion of military service by the wealthy and the unequal exemptions undermined Southern unity and helped shape the war's complex legacy. The conflict was not only a fight for or against slavery but also highlighted class tensions and inequalities that persisted long after the war ended.

Although the North was less affected economically by the Civil War than the South, the region nevertheless experienced significant economic disruption and change. Most of the fighting took place in the South, but some major battles, particularly in Pennsylvania, disrupted industrial production. Being a major centre of production, the battles in this territory had a direct economic impact. Military mobilisation largely affected unskilled workers, immigrants and the poor. These groups were the most likely to be conscripted into the army, affecting the available workforce and changing employment dynamics. Some entrepreneurs and industrialists saw the war as an opportunity for profit. Increased demand for military goods and services led to increased production and, in some cases, price inflation. This generated profits for some, but also led to social tensions, particularly over workers' wages. The war also led to changes in the labour and employment markets. Industries linked to the war effort grew, while others suffered. Economic opportunities and challenges varied considerably by region and industry. Financing the war was a major concern for the Union government. Public debt increased, and new methods of taxation and financing were introduced. This had a long-term impact on the Northern economy. The economy of the North during the Civil War was complex and multifaceted. Although less devastated than the South, the region nevertheless experienced economic disruption, change and challenges. Military mobilisation, economic opportunity and abuse, and changes in markets and employment all shaped the Northern economy during this tumultuous period. How the North managed these challenges had a lasting impact on the economic development of the region and on the US economy as a whole.

The Civil War brought many changes to the North, not only economically, but also socially and culturally. With so many men away at the front, women played an essential role in maintaining the economy of the North. They replaced men in factories and agriculture, taking an active part in the war effort and industrial production. This period was a turning point in the recognition of women's role in the workforce. The lack of male labour in agriculture led to the acceleration of mechanisation. This transformation made it possible to maintain food production despite the shortage of workers. The high mortality rate and economic disruption led to growing opposition to the war in the North. Resistance manifested itself in a variety of ways, including desertions and anti-recruitment riots. The New York draft riots of 1863 were a particularly striking example of this resistance. These riots were violent and deadly, with attacks directed at African-Americans, who were seen as competitors for jobs and resources. With 105 dead and many injured, it was one of the most violent riots in American history. The social and economic changes that took place in the North during the Civil War had a lasting impact on American society. The increased role of women in the workforce, the acceleration of agricultural mechanisation, and the social and racial tensions that emerged during this period continue to influence American society long after the end of the war. The Civil War was a period of profound transformation for the North, with changes that resonated well beyond the end of hostilities. The challenges and opportunities created by the war shaped the region's economic, social and cultural development, leaving a lasting imprint on the nation.

1863 - 1865[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The year 1863 and President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation marked a crucial turning point in the American Civil War. The Proclamation changed the objectives of the war. Instead of simply seeking to preserve the Union, the objective also became that of abolishing slavery. This redefined the cause of the war and gave it a broader moral scope. By declaring all slaves in the Confederate States free, the proclamation weakened the Confederacy's ability to maintain its agricultural and industrial workforce. It undermined the economy of the South. The Proclamation paved the way for the enlistment of African-American soldiers into the Union army. More than 180,000 African-Americans served in Union troops, playing crucial roles in several battles. The Proclamation also had an impact on international relations, making it more difficult for foreign countries (notably the UK and France) to openly support the Confederacy. By aligning the war with the abolition of slavery, Lincoln consolidated international support for the Union cause. Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free all slaves, it was an essential step towards the complete abolition of slavery, which was finally enshrined in the Constitution with the 13th Amendment in 1865. Beyond its legal and military effects, the proclamation became a powerful symbol of freedom and equality. It strengthened the resolve of abolitionists and became a source of inspiration for African Americans and civil rights activists for generations. It should be noted that the proclamation had its limitations. It did not free slaves in the Union border states or in Union-controlled areas of the Confederate states. These limitations were criticised at the time and continue to be debated by historians. The Emancipation Proclamation was therefore a strategic and moral decision that changed the nature of the Civil War. It put the abolition of slavery at the heart of the conflict, influenced military and economic dynamics, and left a lasting legacy in the struggle for civil rights and equality in America.

The Emancipation Proclamation was undoubtedly an important milestone in the American Civil War, particularly in the Union war effort. The Proclamation encouraged free blacks in the North to enlist in the Union army, urging them to see the war as a fight for their own freedom and that of their still enslaved brothers and sisters in the South. This increased Union strength and added a moral dimension to their cause. The Proclamation also encouraged many Southern slaves to flee to Union lines, where they could gain their freedom. These runaway slaves provided not only soldiers but also valuable information about the Southern territories. The flight of slaves and the increased recruitment of free blacks led to the formation of regiments of African-American soldiers. These regiments, although often faced with discrimination and lower pay, played a crucial role in several battles, contributing to the Union's eventual victory. Despite the inequalities and discrimination they faced, African-American soldiers often fought with notable courage and distinction. Their service, sacrifice and exploits on the battlefield not only aided the Union war effort, but also helped change attitudes towards African-Americans in some segments of society. The service of African Americans in the Civil War laid the foundation for the future struggle for civil rights and equality. Their role in the war demonstrated their patriotism, competence and humanity, elements that were used in the following decades to advocate for equal rights. The Emancipation Proclamation was a catalyst for African-American participation in the Union war effort. Not only did it contribute to military victory, but it also laid important groundwork for future struggles for justice and equality in America. The courage and determination of African-American soldiers during the Civil War remains an inspiring part of America's historical legacy.

The commitment and sacrifice of African-American soldiers during the American Civil War is a vital part of the nation's history. Their story is one of indomitable courage and iron will, despite the many obstacles they faced. The fact that almost 20% of adult black males joined the Union army is testament to the depth of their desire for freedom and justice. The Emancipation Proclamation acted as a call to arms, and they responded in large numbers. The estimated loss of 40,000 African-American soldiers is a poignant testament to their determination and sacrifice. Many died not only in battle, but also from disease and neglect, reflecting the difficult and sometimes discriminatory conditions to which they were subjected. Despite the challenges, these soldiers often distinguished themselves on the battlefield. They demonstrated courage and skill that challenged the racial stereotypes of the time, earning the respect of some of their white comrades and commanders. The addition of African-American soldiers strengthened the Union army at a crucial time, contributing to several key victories. Their presence and success also served to undermine Confederate morale. Beyond the military victory, the service of African-American soldiers helped change perceptions and lay the groundwork for the civil rights struggle that would follow. Their story continues to inspire future generations and serve as a reminder of the values of courage, equality and justice. The African-American soldiers of the Civil War did not simply fight for their freedom; they fought for the ideal of a nation where all men are created equal. Their contribution to the Civil War is a vital part of the American identity, a chapter in history that continues to resonate and inspire. Their service played a key role not only in the Union victory but also in writing a new page in American history, ending slavery and paving the way for the continuing struggle for equality and civil rights.