中東の帝国と国家

古代文明発祥の地であり、文化・商業交流の交差点である中東は、特に中世において世界史の中心的役割を果たしてきた。このダイナミックで多様な時代には、数多くの帝国や国家が興亡を繰り返し、それぞれがこの地域の政治的、文化的、社会的景観に消えない足跡を残した。文化的、科学的に頂点に達したイスラムのカリフの拡大から、ビザンチン帝国の長期にわたる影響力、十字軍の侵入やモンゴルの征服を経て、中世の中東は絶えず進化する権力のモザイクであった。この時代は、この地域のアイデンティティを形成しただけでなく、世界史の発展にも大きな影響を与え、東洋と西洋の架け橋となった。中世における中東の帝国や国家を研究することは、征服、回復力、革新、文化的相互作用の物語を明らかにし、人類史における重要な時代を知るための魅力的な窓を提供する。

=オスマン帝国

オスマン帝国の建国と拡大

13世紀末に建国されたオスマン帝国は、3つの大陸の歴史に大きな影響を与えた帝国権力の魅力的な例である:アジア、アフリカ、ヨーロッパ。その建国は一般に、アナトリア地方のトルコ人部族の指導者オスマン1世によるとされている。この帝国の成功は、広大な領土を急速に拡大し、効率的な行政を確立したことにある。14世紀半ばからオスマン帝国はヨーロッパに領土を拡大し始め、バルカン半島の一部を徐々に征服した。この拡大は、地中海と東ヨーロッパのパワーバランスに大きな転換点をもたらした。しかし、一般に信じられているのとは異なり、オスマン帝国はローマを滅ぼしたわけではない。実際、オスマン帝国はビザンチン帝国の首都コンスタンティノープルを包囲し、1453年に征服してその帝国に終止符を打った。この征服は、ヨーロッパにおける中世の終わりと近代の始まりを告げる歴史的大事件であった。

オスマン帝国は、その複雑な行政構造と宗教的寛容性で知られ、特に非ムスリム共同体にある程度の自治を認めたキビ制度が有名である。最盛期は15世紀から17世紀にかけてで、その間、貿易、文化、科学、芸術、建築に多大な影響を及ぼした。オスマン帝国は多くの革新をもたらし、東西間の重要な仲介者であった。しかし、18世紀以降、オスマン帝国はヨーロッパ列強の台頭と国内問題に直面し、衰退し始めた。この衰退は19世紀に加速し、最終的には第一次世界大戦後の帝国解体へと至った。オスマン帝国の遺産は、支配した地域に深く根を下ろし、今日に至るまでそれらの社会の文化的、政治的、社会的側面に影響を与えている。

オスマン帝国は、13世紀末にオスマン1世によって建国された傑出した政治的・軍事的存在であり、ユーラシア大陸の歴史に多大な影響を与えてきた。政治的分断とアナトリアの王朝間の対立を背景に誕生したこの帝国は、瞬く間にその影響力を拡大し、この地域の支配的な大国としての地位を確立した。14世紀半ばは、オスマン帝国にとって決定的な転換期となった。特に1354年のガリポリ征服がそうである。この勝利は単なる武力的な偉業にとどまらず、ヨーロッパにおけるオスマン帝国の最初の定住地となり、バルカン半島における一連の征服への道を開いた。こうした軍事的成功と巧みな外交が相まって、オスマン・トルコは戦略的領土の支配を強化し、ヨーロッパ情勢への干渉を可能にした。

1453年のコンスタンティノープル征服で有名なメフメト2世のような支配者のもと、オスマン帝国は東地中海の政治的景観を再構築しただけでなく、文化的・経済的に大きな変革期を迎えた。ビザンチン帝国に終止符を打ったコンスタンティノープルの占領は、中世の終わりと近代の始まりを告げる、世界史の極めて重要な瞬間だった。ビザンツ帝国は、その規律正しく革新的な軍隊のおかげで戦争技術に秀でていたが、中央集権的な行政システムのもとで多様な民族や宗教を統合するという、統治への実際的なアプローチによっても優れていた。この文化的多様性は、政治的安定と相まって、芸術、科学、商業の繁栄を促した。

オスマン帝国の紛争と軍事的課題

オスマン帝国はその歴史を通じて、壮大な征服と大きな挫折を繰り返し、その運命と支配した地域の運命を形作った。オスマン帝国の拡大には大きな勝利がつきものであったが、戦略的な失敗もあった。オスマン帝国のバルカン半島への侵攻は、ヨーロッパ進出の第一歩であった。この征服は領土を拡大しただけでなく、この地域の支配者としての立場を強化した。メフメト征服王として知られるメフメト2世が1453年にイスタンブールを占領したことは、歴史的に大きな出来事であった。この勝利はビザンチン帝国の終焉を意味するだけでなく、オスマン帝国が超大国として台頭した紛れもない象徴でもあった。オスマン帝国の拡大は1517年のカイロ占領まで続き、エジプトの帝国への統合とアッバース朝カリフの終焉を示す重要な出来事となった。スレイマン大帝のもと、オスマン・トルコは1533年にバグダッドも征服し、メソポタミアの豊かで戦略的な土地への影響力を拡大した。

しかし、オスマン帝国の拡張に障害がなかったわけではない。1529年のウィーン包囲は、ヨーロッパでの影響力をさらに拡大しようとする野心的な試みだったが、失敗に終わった。1623年のさらなる試みも失敗に終わり、オスマン帝国の中央ヨーロッパにおける拡大の限界が示された。これらの失敗は、組織化されたヨーロッパの防衛を前にしたオスマン帝国の軍事力と兵站力の限界を示す重要な出来事であった。もう一つの大きな挫折は、1571年のレパントの海戦での敗北である。この海戦でオスマン帝国艦隊はヨーロッパのキリスト教勢力の連合軍に敗れ、オスマン帝国の地中海支配の転機となった。オスマン帝国はこの敗北からなんとか立ち直り、この地域で強力なプレゼンスを維持することができたが、レパントはオスマン帝国の無制限な拡張の終わりを象徴し、地中海におけるよりバランスのとれた海洋ライバル関係の時代の幕開けとなった。これらの出来事を総合すると、オスマン帝国の膨張のダイナミズムがよくわかる。これらの出来事は、このような広大な帝国を管理することの複雑さと、組織化され抵抗力を増した敵に直面しながら絶え間ない拡大を維持することの難しさを浮き彫りにしている。

オスマン帝国の改革と内部変革

1768年から1774年にかけてのオスマン・ロシア戦争は、オスマン帝国の歴史において極めて重要なエピソードであり、オスマン帝国の重大な領土喪失の始まりとなっただけでなく、政治的・宗教的正統性の構造にも変化をもたらした。この戦争の終結は、1774年のキュチュク・カイナルカ条約(またはクチュク・カイナルジ条約)の調印によって示された。この条約はオスマン帝国に大きな影響を与えた。まず、黒海とバルカン半島の一部など、重要な領土をロシア帝国に割譲することになった。この損失は帝国の規模を縮小させただけでなく、東ヨーロッパと黒海地域における戦略的地位を弱めた。第二に、この条約は、オスマン帝国のヨーロッパにおける地位を弱めるという、当時の国際関係の転換点となった。地域情勢における主要かつしばしば支配的なプレーヤーであったオスマン帝国は、ヨーロッパ列強からの圧力や介入に弱い衰退国家として認識され始めたのである。

最後に、そしておそらく最も重要なこととして、この戦争の終結とキュチュク・カイナルカ条約は、オスマン帝国の内部構造にも大きな影響を与えた。こうした敗北を前に、帝国は正統性の源泉としてカリフの宗教的側面をより重視するようになった。オスマン帝国のスルタンは、すでに帝国の政治的指導者として認められていたが、イスラム共同体の宗教的指導者であるカリフとしてより評価されるようになった。このような展開は、内外の挑戦に直面してスルタンの権威と正統性を強化する必要性に応えたものであり、統一的な力と力の源泉としての宗教に依拠したものであった。このように、オスマン・ロシア戦争とその結果として結ばれた条約は、オスマン帝国の歴史の転換点となり、領土の衰退と帝国の正統性の変化を象徴するものとなった。

外国からの影響と国際関係

1801年のエジプト介入は、イギリス軍とオスマン帝国軍が共同でフランス軍を駆逐したもので、エジプトとオスマン帝国の歴史における重要な転換点となった。オスマン帝国がアルバニア人将校のメフメト・アリをエジプトのパシャに任命したことで、エジプトはオスマン帝国から大きく変貌し、半独立の時代を迎えた。近代エジプトの創始者とされるメフメト・アリは、エジプトの近代化を目指した一連の急進的な改革に着手した。これらの改革は、軍隊、行政、経済など様々な側面に影響を与え、ヨーロッパのモデルに触発された部分もあった。彼の指導の下、エジプトは大きな発展を遂げ、メフメト・アリはエジプト国外への影響力の拡大を目指した。このような背景のもと、ナフダ(アラブ・ルネッサンス)は大きな勢いを得た。アラブ文化を活性化し、現代の課題に適応させようとするこの文化的・知的運動は、メフメト・アリによって始められた改革と開放の風潮の恩恵を受けた。

メフメト・アリの息子イブラヒム・パシャは、エジプトの拡張主義的野心において重要な役割を果たした。1836年、彼は当時弱体化し衰退していたオスマン帝国に対して攻勢を開始した。この対決は1839年に頂点に達し、イブラヒム軍はオスマン帝国に大敗を喫した。しかし、イギリス、オーストリア、ロシアをはじめとするヨーロッパ列強の介入により、エジプトの完全勝利は阻まれた。国際的な圧力の下、和平条約が締結され、メフメト・アリとその子孫の支配下におけるエジプトの事実上の自治が承認された。この承認は、エジプトがオスマン帝国から分離する重要な一歩となったが、エジプトは名目上オスマン帝国の宗主国であることに変わりはなかった。イギリスの立場は特に興味深いものだった。当初はエジプトにおけるフランスの影響力を封じ込めるためにオスマン帝国と同盟を結んでいたが、この地域の政治的・戦略的現実の変化を認識し、最終的にはメフメト・アリのもとでのエジプトの自治を支持することを選択した。この決定は、重要な貿易ルート、特にインドにつながるルートを支配しながら、この地域を安定させたいというイギリスの願望を反映したものだった。19世紀初頭のエジプトのエピソードは、オスマン帝国、エジプト、ヨーロッパ列強の間の複雑なパワー・ダイナミクスだけでなく、当時の中東の政治的・社会的秩序に起きていた重大な変化を物語っている。

近代化と改革運動

1798年のナポレオン・ボナパルトのエジプト遠征は、オスマン帝国にとって啓示的な出来事であり、近代化と軍事力の面でヨーロッパ列強に遅れをとっているという事実を浮き彫りにした。この認識は、帝国の近代化と衰退を食い止めるために1839年に開始された、タンジマートとして知られる一連の改革の重要な原動力となった。トルコ語で「再編成」を意味するタンジマートは、オスマン帝国に大きな変革期をもたらした。この改革の重要な側面のひとつは、帝国の非ムスリム市民であるディミの組織の近代化であった。これには、様々な宗教共同体にある程度の文化的・行政的自治を与えるミレー制度の創設も含まれた。その目的は、これらの共同体をオスマン帝国の構造により効果的に統合する一方で、それぞれのアイデンティティを維持することであった。

第二の改革は、宗教的・民族的分裂を超越したオスマン・トルコの市民権を創設する試みであった。しかし、この試みは、多民族・多宗教の帝国内の深い緊張を反映して、しばしば共同体間の暴力によって妨げられた。同時に、こうした改革は軍隊の特定の派閥内で大きな抵抗に会い、彼らは自分たちの伝統的な地位や特権を脅かすと思われる変化に敵対した。この抵抗は反乱や内部の不安定化を招き、帝国が直面する課題を悪化させた。

このような激動の背景の中、19世紀半ばに「若きオスマン」として知られる政治的・知的運動が勃興した。このグループは、近代化と改革の理想をイスラム教とオスマン帝国の伝統の原則と調和させようとした。彼らは憲法、国民主権、より包括的な政治・社会改革を提唱した。タンジマートの努力とヤング・オスマンの理想は、急速に変化する世界の中でオスマン帝国が直面する課題に対応する重要な試みであった。こうした努力はいくつかの前向きな変化をもたらしたが、同時にオスマン帝国内の深い亀裂と緊張を明らかにし、オスマン帝国末期の数十年間に起こるであろうさらに大きな試練を予感させた。

1876年、オスマン帝国初の君主制憲法を導入したスルタン・アブデュルハミド2世が即位し、タンジマートの過程において重要な局面を迎えた。この時期は、近代化の原則と帝国の伝統的な構造を調和させようとする重要な転換点となった。1876年に制定された憲法は、帝国の行政を近代化し、当時のヨーロッパで流行していた自由主義と立憲主義の理想を反映した立法制度と議会を確立しようとするものだった。しかし、アブデュルハミド2世の治世は、欧米列強との対立の激化を背景に、帝国内外のムスリム間の結びつきを強めることを目的としたイデオロギー、汎イスラム主義が強く台頭した時期でもあった。

アブデュルハミド2世は、汎イスラーム主義を自らの権力を強化し、外部からの影響に対抗するための手段として用いた。イスラム教の指導者や高官をイスタンブールに招き、彼らの子供たちをオスマン帝国の首都で教育することを提案した。しかし1878年、アブデュルハミド2世は驚くべき方向転換を行い、憲法を停止して議会を閉鎖し、独裁的な支配に戻った。この決定の背景には、政治プロセスに対する統制が不十分であったことと、帝国内で民族主義運動が台頭してきたことへの懸念があった。こうしてスルタンは、政府に対する直接支配を強化する一方で、正当化の手段として汎イスラム主義を推進し続けた。

このような状況の中で、第一世代のイスラームの実践への回帰を目指す運動であるサラフィズムは、汎イスラーム主義とナハダ(アラブ・ルネサンス)の理想の影響を受けた。現代のサラフィズム運動の先駆者とされるジャマール・アル=ディン・アル=アフガーニーは、こうした思想の普及に重要な役割を果たした。アル=アフガーニーは、技術的・科学的な近代化のある種の導入を奨励する一方で、イスラームの本来の原理への回帰を提唱した。このように、タンズィマート時代とアブデュルハミド2世の治世は、近代化の要求と伝統的な構造やイデオロギーの維持の間で引き裂かれたオスマン帝国における改革の試みの複雑さを物語っている。この時代の影響は、帝国の滅亡を越えて、現代のイスラム世界全体の政治的・宗教的運動に影響を与えた。

オスマン帝国の衰退と滅亡

「東方問題」とは、主に19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて使われた用語で、徐々に衰退していくオスマン帝国の将来に関する複雑かつ多角的な議論を指す。この問題は、帝国の相次ぐ領土喪失、トルコ・ナショナリズムの台頭、特にバルカン半島における非イスラム地域からの分離の進展の結果として浮上した。早くも1830年、ギリシャの独立によってオスマン帝国はヨーロッパ領土を失い始めた。この傾向はバルカン戦争で続き、第一次世界大戦で加速し、1920年のセーヴル条約と1923年のムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルク率いるトルコ共和国の建国に至った。これらの敗北は、この地域の政治的地理を大きく変えた。

こうした中、トルコのナショナリズムが勢いを増した。この運動は、それまでの多民族・多宗教モデルとは対照的に、トルコ的要素を中心に帝国のアイデンティティを再定義しようとするものだった。このようなナショナリズムの台頭は、帝国が徐々に解体し、新たな国民的アイデンティティを形成する必要性に直接反応したものであった。同時に、汎イスラム主義を掲げたスルタン・アブデュルハミド2世を中心に、一種の「イスラムの国際」を形成しようという構想が生まれた。この考え方は、国境を越えて民族を団結させようとする国際主義のヨーロッパにおける同様の考え方に触発され、イスラム諸国間の連合や協力を構想したものであった。その目的は、イスラムの領土の利益と独立を守りながら、西欧列強の影響と介入に抵抗するために、イスラム諸国民の統一戦線を作ることであった。

しかし、このような思想の実現は、多様な国益、地域的対立、民族主義思想の影響力の増大のために困難であることが判明した。さらに、第一次世界大戦やオスマン帝国各地での民族主義運動の台頭をはじめとする政治的展開によって、「イスラムの国際」というビジョンはますます実現不可能なものとなっていった。したがって、「東方問題」全体は、この時期にこの地域で起こった地政学的・イデオロギー的な大変革を反映している。

19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてドイツが採用した「世界政策」(Weltpolitik)は、オスマン帝国を巻き込んだ地政学的力学において重要な役割を果たした。カイザー・ヴィルヘルム2世の時代に始まったこの政策は、特に植民地拡大と戦略的同盟関係を通じて、国際舞台におけるドイツの影響力と威信を拡大することを目的としていた。ロシアとイギリスからの圧力から逃れようとしていたオスマン帝国は、ドイツに有用な同盟国の可能性を見出したのである。この同盟は、特にベルリン・バグダッド鉄道(BBB)建設プロジェクトに象徴される。ビザンティウム(イスタンブール)を経由してベルリンとバグダッドを結ぶこの鉄道は、戦略的・経済的に非常に重要なものだった。この鉄道は、貿易と通信を容易にするだけでなく、この地域におけるドイツの影響力を強化し、中東におけるイギリスとロシアの利害に対抗するためのものだった。

パントゥルキストやオスマン帝国支持者にとって、ドイツとの同盟は好意的に受け止められていた。トルコ語圏諸民族の統一と連帯を主張するパントゥルキストは、この同盟にオスマン帝国の地位を強化し、対外的脅威に対抗する機会を見出した。ドイツとの同盟は、長い間オスマン帝国の政治や情勢に影響を及ぼしてきたロシアやイギリスといった伝統的な大国からの圧力に代わる選択肢を提供するものであった。オスマン帝国とドイツのこの関係は、第一次世界大戦中に両国の同盟関係が中央列強の中でピークに達した。この同盟はオスマン帝国にとって軍事的にも政治的にも重要な結果をもたらし、最終的には戦後の帝国解体へとつながる出来事の一翼を担った。ドイツのヴェルトポリティークとベルリン・バグダッド鉄道計画は、列強からの圧力に直面しながらもオスマン帝国の完全性と独立性を維持するための戦略における重要な要素であった。この時期は、20世紀初頭における同盟関係と地政学的利害の複雑さを示す、帝国の歴史における重要な瞬間であった。

1908年、オスマン帝国の歴史において決定的な転機となったのは、主に統一進歩委員会(CUP)に代表される青年トルコ人運動が引き起こした第二次憲法制定期の開始であった。この運動は当初、オスマン帝国の改革派将校や知識人によって結成され、帝国の近代化と崩壊からの救済を目指した。

CUPの圧力により、スルタン・アブデュルハミド2世は1878年以来停止していた1876年憲法を復活させ、第二次憲法時代の幕開けとなった。この憲法の復活は、帝国の近代化と民主化への一歩と見なされ、より広範な市民的・政治的権利と議会政治の確立が約束された。しかし、この改革期はすぐに大きな試練に直面した。1909年、伝統的な保守派と宗教界は、改革と連合派の影響力の拡大に不満を抱き、立憲政府を転覆させてスルタンの絶対的権威を再確立するクーデターを企てた。この試みは、青年トルコ人が推進した急速な近代化と世俗化政策への反対、特権と影響力の喪失への懸念が動機となっていた。しかし、青年トルコ人はこの反革命のエピソードを口実に、抵抗勢力を鎮圧し、権力を強化することに成功した。この時期、反対派に対する弾圧が強まり、CUPの手に権力が集中した。

1913年、この状況は、しばしばクーデターと形容される、CUP指導者による議会占拠で頂点に達した。これにより、オスマン帝国の短期間の立憲制と議会制の試みは終わりを告げ、青年トルコ人によるますます権威主義的な体制が確立された。彼らの支配下でオスマン帝国は大幅な改革を行ったが、同時に中央集権的で民族主義的な政策も強め、第一次世界大戦中とその後に展開される出来事の基礎を築いた。この激動の時代は、オスマン帝国内部の緊張と闘争を反映しており、変化と伝統の力の間で引き裂かれ、帝国の晩年に続く急進的な変革の基礎を築いた。

第一次世界大戦中の1915年、オスマン帝国は、現在ではアルメニア人大虐殺として広く認識されている、歴史上の悲劇的で暗いエピソードに着手した。この政策は、帝国内に居住するアルメニア人を組織的に追放し、大量殺戮し、殺害するというものであった。アルメニア人に対するキャンペーンは、逮捕、処刑、大量追放から始まった。アルメニア人の男性、女性、子供、老人は家を追われ、シリアの砂漠を死の行進に送られ、多くの者が飢え、渇き、病気、暴力で死んだ。この地域で長く豊かな歴史を築いてきた多くのアルメニア人コミュニティが破壊された。

犠牲者数の見積もりはさまざまだが、一般に80万人から150万人のアルメニア人がこの期間に亡くなったと考えられている。ジェノサイドは、世界のアルメニア人コミュニティに永続的な影響を与え、少なくとも一部のグループによる否定や軽視のために、大きな感受性と論争の対象であり続けている。アルメニア人虐殺は、しばしば最初の近代的大量虐殺のひとつとみなされ、20世紀における他の集団残虐行為の暗い先駆けとしての役割を果たした。また、現代のアルメニア人のアイデンティティの形成にも重要な役割を果たし、ジェノサイドの記憶はアルメニア人の意識の中心であり続けている。これらの出来事の認識と記念は、国際関係、特に人権とジェノサイドの防止に関する議論において、重要な問題であり続けている。

ペルシャ帝国

ペルシア帝国の起源と完成

現在イランとして知られるペルシア帝国の歴史は、王朝交代や外国からの侵略にもかかわらず、文化的・政治的に印象的な連続性を持っていることが特徴である。この継続性は、この地域の歴史的、文化的進化を理解する上で重要な要素である。

紀元前7世紀初頭に成立したメデス帝国は、イランの歴史における最初の大国のひとつである。この帝国は、イラン文明の基礎を築く上で重要な役割を果たした。しかし、紀元前550年頃、キュロス大王としても知られるペルシアのキュロス2世によって打倒された。キュロスによるメディア征服は、アケメネス朝の始まりであり、この時代には大きな拡大と文化的影響力があった。アケメネス朝はインダス川からギリシャに至る広大な帝国を築き、その統治は効率的な行政と帝国内の異なる文化や宗教に対する寛容な政策によって特徴づけられた。この帝国は、紀元前330年にアレクサンダー大王によって滅亡させられたが、ペルシャの文化的な連続性に終止符が打たれたわけではなかった。

ヘレニズム支配と政治的分裂の時代を経て、西暦224年にサーサーン朝が勃興した。アルダシール1世によって建国されたこの王朝は、西暦624年まで続き、この地域の新しい時代の幕開けとなった。サーサーン朝のもと、大イランは文化的・政治的ルネッサンス期を迎えた。首都クテシフォンは、帝国の壮大さと影響力を反映し、権力と文化の中心となった。サーサーン朝は、この地域の芸術、建築、文学、宗教の発展に重要な役割を果たした。彼らはゾロアスター教を支持し、ペルシャ文化とアイデンティティに大きな影響を与えた。彼らの帝国はローマ帝国、後にビザンチン帝国との絶え間ない対立に見舞われ、その結果、両帝国を弱体化させる高価な戦争に発展した。7世紀のイスラムによる征服の後、サーサーン朝は滅亡したが、ペルシアの文化と伝統は、後のイスラム時代においても、この地域に影響を与え続けた。この回復力と、独特の文化的核を維持しながら新しい要素を統合する能力が、ペルシャ史における継続性の概念の核心である。

イスラーム支配下のイラン征服と変容

642年以降、イランはイスラム教徒の征服を受け、イスラム時代が始まり、その歴史において新たな時代を迎えた。この時代は、この地域の政治史のみならず、社会的、文化的、宗教的構造においても重要な転換点となった。イスラム軍によるイランの征服は、632年の預言者モハメッドの死後まもなく始まった。642年、サーサーン朝の首都クテシフォンを占領すると、イランは新興のイスラム帝国の支配下に入った。この移行は、軍事衝突と交渉の両方を含む複雑なプロセスであった。イスラムの支配下で、イランは大きな変化を遂げた。それまでの帝国下で国教であったゾロアスター教に代わって、イスラム教が徐々に支配的な宗教となった。しかし、この移行は一夜にして起こったわけではなく、異なる宗教的伝統の共存と相互作用の時期があった。

イランの文化と社会はイスラムの影響を大きく受けたが、イスラム世界にも大きな影響を及ぼした。イランはイスラム文化と知識の重要な中心地となり、哲学、詩、医学、天文学などの分野で目覚ましい貢献をした。詩人ルーミーや哲学者アヴィセンナ(イブン・シーナ)といったイランを象徴する人物は、イスラムの文化的・知的遺産において大きな役割を果たした。この時代には、ウマイヤ朝、アッバース朝、サファリ朝、サーマーン朝、ブーイド朝、後のセルジューク朝といった歴代王朝も登場し、それぞれがイランの歴史の豊かさと多様性に貢献した。これらの王朝はそれぞれ、この地域の統治、文化、社会に独自のニュアンスをもたらした。

セフェヴィト朝の出現と影響

1501年、シャー・イスマイル1世がアゼルバイジャンにセフェヴィト朝を建国し、イランと中東の歴史に大きな出来事が起こった。これはイランだけでなく、この地域全体にとって新しい時代の幕開けとなった。国教としてドゥオデシマン・シーア派が導入され、この変化はイランの宗教的・文化的アイデンティティに大きな影響を与えた。1736年まで君臨したセフェヴィド帝国は、イランを独自の政治的・文化的存在として確固たるものにする上で重要な役割を果たした。カリスマ的指導者であり、才能豊かな詩人でもあったシャー・イスマーイール1世は、さまざまな地域を支配下にまとめ、中央集権的で強力な国家を作り上げることに成功した。彼の最も重要な決断のひとつは、十二進法のシーア派を帝国の公式宗教として押し付けたことであり、この行為はイランと中東の将来に重大な影響を及ぼした。

このイランの「シーア派化」は、スンニ派住民やその他の宗教集団を強制的にシーア派に改宗させるもので、イランをスンニ派の隣国、特にオスマン帝国と差別化し、セフェヴィト朝の権力を強化するための意図的な戦略であった。この政策はまた、イランのシーア派のアイデンティティを強化する効果もあり、それは今日に至るまでイラン国家の特徴となっている。セフェヴィー朝の時代、イランは文化・芸術のルネッサンス期を迎えた。首都イスファハーンは、イスラム世界で最も重要な芸術、建築、文化の中心地のひとつとなった。セフェヴィト朝は、絵画、書道、詩、建築などの芸術の発展を奨励し、豊かで永続的な文化遺産を築いた。しかし、オスマン帝国やウズベク族との戦争など、帝国内外の紛争にも見舞われた。これらの紛争は、内部的な課題とともに、最終的には18世紀の帝国の衰退につながった。

1514年に起こったチャルディランの戦いは、セファルディ帝国とオスマン帝国の歴史において重要な出来事であり、軍事的な転換点となっただけでなく、2つの帝国の間に重要な政治的分水嶺が形成されたことを示すものである。この戦いでは、シャー・イスマイル1世率いるセフェヴ朝軍が、スルタン・セリム1世率いるオスマン帝国軍と激突した。セフェヴ朝軍は勇敢に戦ったものの、オスマン帝国軍の技術的優位、特に大砲の効果的な使用により、オスマン帝国軍に敗北した。この敗北はセファルディ帝国に大きな影響を与えた。カルディランの戦いの直接的な結果のひとつは、セフェヴィッド朝にとって大きな領土の喪失であった。オスマン・トルコはアナトリアの東半分を占領することに成功し、この地域におけるセフェヴィト朝の影響力を大幅に縮小させた。この敗北はまた、両帝国の間に永続的な政治的境界線を築き、この地域の重要な地政学的指標となった。セフェヴィト朝の敗北は、シャー・イスマイル1世と彼のシーア派化政策を支持していた宗教共同体であるアレヴィ派にも影響を与えた。セフェヴィト朝のシャーへの忠誠と、オスマン帝国の支配的なスンニ派の慣習とは相容れない独自の宗教的信条が原因だった。

チャルディランでの勝利の後、スルタン・セリム1世は拡大を続け、1517年にはカイロを征服し、アッバース朝カリフ制に終止符を打った。この征服は、オスマン帝国をエジプトにまで拡大しただけでなく、イスラム教スンニ派世界に対する宗教的・政治的権威を象徴するカリフの称号を得たことで、有力なイスラム指導者としてのスルタンの地位を強化した。したがって、チャルディランの戦いとその余波は、当時の2大イスラム勢力間の激しい対立を物語っており、中東の政治的、宗教的、領土的歴史を大きく形成した。

カージャール朝とイランの近代化

1796年、イランではアガ・モハンマド・ハーン・カージャールによって新たな支配王朝カージャール朝が誕生した。トルクメン出身のこの王朝は、ザンド朝に代わって20世紀初頭までイランを支配した。アガ・モハンマド・ハーン・カジャールは、イランのさまざまな派閥と領土を統一した後、1796年に自ら国王を宣言し、カジャール朝による支配が正式に始まった。この時代は、イランの歴史においていくつかの重要な意味を持つ。カージャール朝の下、イランは長年の混乱と内部分裂の後、権力の集中化と領土の統合を経験した。首都はシーラーズからテヘランに移され、テヘランはイランの政治と文化の中心となった。この時代には、複雑な国際関係、特に当時の帝国主義大国であったロシアやイギリスとの関係も顕著であった。カージャール朝は困難な国際環境を切り抜けなければならず、イランはしばしば大国の地政学的対立、特にロシアとイギリスの「グレート・ゲーム」に巻き込まれた。このような相互作用によって、イランはしばしば領土を失い、経済的・政治的に大きな譲歩を余儀なくされた。

文化面では、カージャール朝はその独特な芸術、特に絵画、建築、装飾芸術で知られている。カージャール朝宮廷は芸術の庇護の中心であり、この時代には伝統的なイランの様式と近代的なヨーロッパの影響がユニークに融合していた。しかし、カージャール朝は国の近代化を効果的に進めることができず、国民のニーズに応えられなかったという批判もあった。この失敗は国内の不満につながり、20世紀初頭に起こった改革運動や憲法革命の基礎を築いた。カージャール朝はイランの歴史において重要な時期であり、中央集権化への努力、外交的挑戦、文化的貢献が顕著であった。

20世紀のイラン:立憲君主制へ向けて

1906年、イランは立憲政体時代の開始という歴史的瞬間を経験した。この発展は、君主の絶対的権力の制限と、より代表的で立憲的な統治を求める社会的・政治的運動の影響を大きく受けた。イラン立憲革命により、1906年にイラン初の憲法が採択され、イランは立憲君主制へと移行した。この憲法は、議会(マジュリス)の創設を規定し、イランの社会と政府を近代化・改革するための法律と機構を整備した。しかし、この時期は、外国からの干渉や国内の勢力圏の分裂が顕著であった。イランはイギリスとロシアの対立に巻き込まれ、それぞれがこの地域での影響力を拡大しようとしていた。これらの大国はそれぞれ異なる「国際秩序」や勢力圏を確立し、イランの主権を制限した。

1908年から1909年にかけての石油の発見は、イランの状況に新たな局面をもたらした。マスジェド・ソレイマン地域で発見されたこの石油は、イランの石油資源を支配しようとする諸外国、特にイギリスの注目を一気に集めた。この発見は、国際舞台におけるイランの戦略的重要性を著しく高めるとともに、イラン国内の力学を複雑にした。このような外圧や天然資源にまつわる利害にもかかわらず、イランは中立政策を維持し、特に第一次世界大戦のような世界的な紛争の際には中立を貫いた。この中立は、自国の自治を守り、資源を開発し政治を支配しようとする外国の影響に抵抗しようとする試みでもあった。20世紀初頭は、イランにとって変化と挑戦の時代であり、政治的近代化への努力、石油の発見による新たな経済的挑戦の出現、複雑な国際環境における航海などが特徴的であった。

第一次世界大戦におけるオスマン帝国

外交工作と同盟の形成

オスマン帝国が1914年に第一次世界大戦に参戦する以前には、イギリス、フランス、ドイツをはじめとする複数の大国を巻き込んだ複雑な外交・軍事工作が行われていた。イギリス、フランスとの同盟の可能性を模索した後、オスマン帝国は最終的にドイツとの同盟を選択した。この決定には、オスマン帝国とドイツとの間にすでに存在した軍事的・経済的関係や、他のヨーロッパの大国の意図に対する認識など、いくつかの要因が影響した。

この同盟にもかかわらず、オスマン帝国は国内の困難と軍事的限界を認識していたため、紛争に直接参戦することには消極的であった。しかし、ダーダネルス海峡事件で状況は一変した。オスマン帝国は軍艦(一部はドイツから譲り受けた)を使って黒海のロシアの港を砲撃した。この行動により、オスマン帝国は中央列強とともに、ロシア、フランス、イギリスをはじめとする連合国との戦争に巻き込まれた。

オスマン帝国の参戦を受けて、イギリスは1915年にダーダネルス海峡作戦を開始した。その目的は、ダーダネルス海峡とボスポラス海峡を掌握し、ロシアへの海路を開くことだった。しかし、この作戦は連合軍にとって失敗に終わり、双方に多くの犠牲者を出す結果となった。同じ頃、イギリスはエジプトに対する支配権を正式に確立し、1914年にイギリス領エジプト保護領を宣言した。この決定は戦略的な動機に基づくもので、イギリスの航路、特にアジアの植民地へのアクセスに不可欠なスエズ運河を確保することが主な目的だった。これらの出来事は、第一次世界大戦中の中東における地政学的状況の複雑さを物語っている。オスマン帝国が下した決断は、自らの帝国にとってだけでなく、戦後の中東の構成にも重要な影響を及ぼした。

アラブの反乱と中東のダイナミクスの変化

第一次世界大戦中、連合国は南部に新たな戦線を開くことでオスマン帝国の弱体化を図り、1916年の有名なアラブの反乱を引き起こした。この反乱は中東の歴史において重要な出来事であり、アラブ民族主義運動の始まりとなった。メッカのシェリフ、フセイン・ベン・アリはこの反乱で中心的な役割を果たした。彼の指導の下、「アラビアのロレンス」として知られるT.E.ロレンスなどの励ましと支援を受けて、アラブ人はオスマン帝国の支配に対抗し、統一アラブ国家の樹立を目指して立ち上がった。この独立と統一への熱望は、民族解放への願望と、イギリス、特にヘンリー・マクマホン将軍による自治の約束が動機となっていた。

アラブの反乱はいくつかの重要な成功を収めた。1917年6月、フセイン・ベン・アリの息子であるファイサルがアカバの戦いに勝利した。この勝利により、オスマン帝国に対する重要な戦線が開かれ、アラブ軍の士気が高まった。アラビアのロレンスやその他のイギリス人将校の協力を得て、ファイサルはヒジャーズのアラブ諸部族をまとめることに成功し、1917年のダマスカス解放につながった。1920年、ファイサルはシリア国王を宣言し、自決と独立を求めるアラブの願望を肯定した。しかし、彼の野心は国際政治の現実に直面した。1916年のサイクス・ピコ協定(英仏間の秘密協定)は、すでに中東の大部分を勢力圏に分割しており、アラブ統一王国への期待は失われていた。アラブの反乱は、戦争中にオスマン帝国を弱体化させる決定的な要因となり、近代アラブ・ナショナリズムの基礎を築いた。しかし、戦後はヨーロッパの委任統治下で中東は多くの国民国家に分割され、フセイン・ベン・アリとその支持者が構想したアラブ統一国家の実現は遠のいた。

内乱とアルメニア人虐殺

第一次世界大戦は、1917年のロシア革命の結果、ロシアが紛争から撤退するなど、複雑な展開と力学の変化によって特徴づけられた。この撤退は、戦争の行方と他の交戦国に大きな影響を与えた。ロシアの撤退により、中央列強、特にドイツへの圧力が緩和され、ドイツはフランスとその同盟国に対して西部戦線に兵力を集中させることができるようになった。この変化は、パワーバランスを維持する方法を模索していたイギリスとその同盟国を悩ませた。

ボリシェヴィキのユダヤ人に関しては、1917年のロシア革命とボリシェヴィズムの台頭が、ロシア国内のさまざまな要因に影響された複雑な現象であったことに注意することが重要である。当時の多くの政治運動と同様、ボリシェヴィキの中にもユダヤ人は存在したが、その存在を過度に解釈したり、単純化した反ユダヤ主義的な物語の推進に利用すべきではない。オスマン帝国に関しては、青年トルコ運動の指導者の一人であり陸軍大臣でもあったエンヴェル・パシャが戦争遂行に重要な役割を果たした。1914年、彼はコーカサス地方でロシア軍に対する悲惨な攻勢を開始し、その結果、サリカミシュの戦いでオスマン帝国は大敗北を喫した。

エンヴェル・パシャの敗北は、アルメニア人大虐殺の勃発など悲劇的な結果をもたらした。エンヴェル・パシャをはじめとするオスマン帝国の指導者たちは、敗戦を説明するスケープゴートを求めて、帝国の少数民族であるアルメニア人がロシアと結託していると非難した。この告発は、アルメニア人に対する組織的な強制送還、虐殺、絶滅のキャンペーンを煽り、現在アルメニア人大虐殺として認識されているものにまで発展した。この大虐殺は、第一次世界大戦とオスマン帝国の歴史における最も暗いエピソードのひとつであり、大規模な紛争と民族憎悪政策の恐怖と悲劇的な結末を浮き彫りにしている。

戦後の和解と中東の再定義

1919年1月に始まったパリ講和会議は、第一次世界大戦後の世界秩序を再定義する上で極めて重要な出来事であった。この会議では、主要連合国の首脳が一堂に会し、破綻したオスマン帝国の領土を含む和平の条件と地政学的将来について話し合った。会議で話し合われた主要な問題のひとつは、中東におけるオスマン帝国領の将来に関するものだった。連合国は、石油資源の支配を含むさまざまな政治的、戦略的、経済的配慮に影響され、この地域の国境線の引き直しを検討していた。会議では理論上、関係諸国がそれぞれの見解を示すことができたが、実際にはいくつかの代表団は疎外されたり、要求が無視されたりした。たとえば、エジプトの独立を議論しようとしたエジプト代表団は、メンバーの一部がマルタに亡命するなど、障害に直面した。このような状況は、ヨーロッパ列強の利害が優先されることが多かった会議での不平等なパワー・ダイナミクスを反映している。

フセイン・ビン・アリの息子でアラブ反乱の指導者であったファイサルは、会議で重要な役割を果たした。彼はアラブの利益を代表し、アラブの独立と自治の承認を主張した。彼の努力にもかかわらず、会議での決定は独立統一国家を求めるアラブの願望を十分に満たすものではなかった。ファイサルはシリアに国家を建設し、1920年にシリア国王を宣言した。1916年のサイクス・ピコ協定に基づくヨーロッパ列強の中東分割の一環であった。したがって、パリ会議とその成果は中東に大きな影響を与え、今日まで続く多くの地域的緊張と紛争の基礎を築いた。下された決定は、第一次世界大戦の戦勝国の利益を反映したものであり、しばしばこの地域の人々の民族的願望を損なうものであった。

フランスを代表するジョルジュ・クレマンソーとアラブ反乱の指導者ファイサルとの間の協定、および中東における新国家創設をめぐる議論は、この地域の地政学的秩序を形成した第一次世界大戦後の重要な要素である。クレマンソーとフェイサルの合意は、フランスにとって非常に有利なものと見なされた。アラブ領土の自治権を確保しようとしたフェイサルは、大幅な譲歩を余儀なくされた。この地域に植民地的・戦略的利益を持つフランスは、パリ会議での立場を利用して、特にシリアやレバノンなどの領土に対する支配権を主張した。レバノン代表団は、フランスの委任統治下に大レバノンという独立国家を創設する権利を獲得した。この決定には、レバノンのマロン派キリスト教社会が、フランスの指導の下、国境を拡大し、ある程度の自治権を持つ国家の樹立を望んでいたことが影響していた。クルド人問題については、クルディスタンの創設が約束された。この約束は、クルド人の民族主義的願望を認め、オスマン帝国を弱体化させる手段でもあった。しかし、この約束の履行は複雑であることが判明し、戦後の条約ではほとんど無視された。

これらの要素は1920年のセーヴル条約に集約され、オスマン帝国の分割が正式に決定された。この条約によって中東の国境が塗り替えられ、フランスとイギリスの委任統治下に新しい国家が誕生した。この条約では、クルド人の自治組織の創設も規定されたが、この規定は実施されることはなかった。セーヴル条約は完全には批准されず、後に1923年のローザンヌ条約に取って代わられたが、この地域の歴史において決定的な出来事だった。この条約は中東の近代的な政治構造の基礎を築いたが、同時に、この地域の民族的、文化的、歴史的現実を無視したために、将来の多くの紛争の種をまいた。

共和制への移行とアタテュルクの台頭

第一次世界大戦終結後、弱体化し圧力を受けていたオスマン帝国は、1920年にセーヴル条約に調印することに同意した。オスマン帝国を解体し、領土を再分配したこの条約は、帝国の命運をめぐる長年にわたる「東方問題」の終結を意味するように思われた。しかし、セーブル条約はこの地域の緊張を終わらせるどころか、民族主義的感情を悪化させ、新たな紛争を引き起こした。

トルコでは、セーヴル条約に反対するムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルク率いる強力な民族主義レジスタンスが結成された。この民族主義運動は、オスマン帝国領土に深刻な領土損失を課し、外国の影響力を増大させる条約の条項に反対した。レジスタンスは、アルメニア人、アナトリアのギリシア人、クルド人などさまざまな集団と戦い、新しい均質なトルコ民族国家を建設することを目指した。続くトルコ独立戦争は、激しい対立と領土の再編成の時代であった。トルコ民族主義勢力はアナトリアでギリシャ軍を押し返し、他の反乱軍に対抗することに成功した。この軍事的勝利は、1923年のトルコ共和国建国の重要な要素となった。

これらの出来事の結果、1923年、セーヴル条約はローザンヌ条約に取って代わられた。この新しい条約は、新トルコ共和国の国境を承認し、セーヴル条約の最も懲罰的な条項を取り消した。ローザンヌ条約は、近代トルコが主権を持つ独立国家として確立する上で重要な段階を示し、この地域と国際情勢におけるトルコの役割を再定義した。これらの出来事は中東の政治地図を塗り替えただけでなく、オスマン帝国の終焉を意味し、トルコの歴史に新たな1ページを開いた。

カリフ制の廃止とその波紋

1924年のカリフ制の廃止は、何世紀にもわたって続いたイスラム制度の終焉を意味し、中東の近代史における大きな出来事であった。この決定は、トルコ共和国の建国者であるムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクが、新トルコ国家の世俗化と近代化を目指した改革の一環として下したものであった。カリフ制の廃止は、伝統的なイスラムの権威構造に打撃を与えた。カリフは預言者モハメッドの時代から、イスラム共同体(ウンマ)の精神的・時間的な長であると考えられていた。カリフの廃止によって、このスンニ派イスラムの中心的な制度は消滅し、イスラム指導者の空白が残された。

トルコのカリフ制廃止に対抗して、オスマン帝国崩壊後にヒジャーズ王となったフセイン・ベン・アリがカリフを宣言した。フセインは預言者ムハンマドの直系子孫であるハシェミット家の一員であり、イスラム世界における精神的・政治的連続性を維持するためにこの地位を主張しようとした。しかし、フセインのカリフに対する主張は広く認められることはなく、短命に終わった。フセインの地位は、アラビア半島の大部分を支配していたサウド家の反対など、内外の挑戦によって弱体化した。アブデラズィーズ・イブン・サウード率いるサウード家の台頭は、やがてヒジャーズの征服とサウジアラビア王国の成立につながった。サウードによるフセイン・ビン・アリーの追放は、アラビア半島における権力の急進的な変化を象徴し、カリフ制への野望の終焉を意味した。この出来事はまた、イスラム世界で進行中の政治的・宗教的変革を浮き彫りにし、多くのイスラム諸国で政治と宗教がより明確な道を歩み始める新時代の幕開けとなった。

第一次世界大戦後の時期は、中東の政治的再定義にとって極めて重要な時期であり、特にフランスとイギリスをはじめとするヨーロッパ列強による重要な介入があった。1920年、シリアで大きな出来事が起こり、この地域の歴史に転機が訪れた。フセイン・ベン・アリの息子でアラブ反乱の中心人物であったファイサルは、オスマン帝国崩壊後のシリアにアラブ王国を樹立し、アラブ統一国家の夢を実現しようとしていた。しかし、彼の野望はフランスの植民地利益という現実に直面することになる。1920年7月のメイサルーンの戦いの後、国際連盟の委任統治下にあったフランスはダマスカスを支配下に置き、ファイサルのアラブ国家を解体し、彼のシリア支配を終わらせた。このフランスの介入は、中東諸国民の民族的願望がしばしばヨーロッパ列強の戦略的利益の影に隠れてしまうという、戦後の複雑な力学を反映していた。シリアの王位を追われたフェイサルは、それでもイラクに新たな運命を見出した。1921年、イギリスの支援のもと、彼はイラクのハシェミット王国の初代国王に任命された。これは、石油が豊富なこの地域に有利な指導力と安定性を確保するためのイギリス側の戦略的な動きであった。

同じ頃、トランスヨルダンでは、イギリスによる別の政治工作が行われた。パレスチナにおけるシオニストの願望を阻止し、委任統治領の均衡を保つため、1921年にトランスヨルダン王国を創設し、フセイン・ベン・アリのもう一人の息子アブダッラーをそこに据えた。この決定は、パレスチナをイギリスの直接支配下に置きつつ、アブダラに統治する領土を提供することを意図したものだった。トランスヨルダンの設立は、近代ヨルダン国家形成の重要な一歩であり、植民地的利害がいかに近代中東の国境と政治構造を形成したかを示すものであった。第一次世界大戦後のこの地域におけるこうした動きは、戦間期における中東政治の複雑さを示している。自国の戦略的・地政学的利益に影響されたヨーロッパの代理国が下した決断は永続的な結果をもたらし、中東に影響を与え続ける国家構造や紛争の基礎を築いた。これらの出来事はまた、この地域の人々の民族的願望とヨーロッパの植民地支配の現実との間の闘争を浮き彫りにしている。

サンレモ会議の波紋

1920年4月に開催されたサンレモ会議は、第一次世界大戦後の歴史、特に中東の歴史にとって決定的な出来事であった。この会議では、オスマン帝国の敗戦と解体後、かつてのオスマン帝国の地方に対する委任統治権の割り当てが焦点となった。この会議で、勝利した連合国は委任統治領の分配を決定した。フランスはシリアとレバノンの委任統治権を獲得し、戦略的に重要で文化的にも豊かな2つの地域を支配することになった。イギリスはトランスヨルダン、パレスチナ、メソポタミアの委任統治権を与えられ、後者はイラクと改名された。これらの決定は、植民地支配国の地政学的、経済的利益、特に資源へのアクセスと戦略的支配の利益を反映したものであった。

こうした動きと並行して、トルコはムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの指導の下、国家の再定義のプロセスに取り組んでいた。戦後、トルコは新たな国境を確立しようとした。この時期には悲劇的な紛争、特に戦争中に行われたアルメニア人大虐殺に続くアルメニア人潰しがあった。1923年、数年にわたる闘争と外交交渉の末、ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクはセーヴル条約の再交渉に成功した。セーヴル条約は1920年にトルコに課されたもので、トルコの民族主義者にとっては屈辱的で受け入れがたいものであった。1923年7月に調印されたローザンヌ条約は、セーヴル条約に代わり、新トルコ共和国の主権と国境を承認した。この条約はオスマン帝国の公式な終焉を意味し、近代トルコ国家の基礎を築いた。

ローザンヌ条約は、ムスタファ・ケマルとトルコの民族主義運動にとって大きな成功だったと考えられている。トルコの国境を再定義しただけでなく、新共和国はセーヴル条約の制約から解放され、国際舞台で新たなスタートを切ることができた。サンレモ会議からローザンヌ条約調印に至るこれらの出来事は、中東に多大な影響を与え、国境、国際関係、そしてこの地域の政治力学をその後数十年にわたって形成した。

連合国の約束とアラブの要求

第一次世界大戦中、オスマン帝国の解体と分割は、イギリス、フランス、ロシアを中心とする連合国の関心の中心であった。これらの列強は、中央列強の同盟国であるオスマン帝国に対する勝利を予期し、その広大な領土の分割を計画し始めた。

第一次世界大戦が激化していた1915年、コンスタンチノープルでイギリス、フランス、ロシアの代表が参加する重要な交渉が行われた。この話し合いの中心は、当時中央列強と同盟関係にあったオスマン帝国の領土の将来についてだった。オスマン帝国は弱体化し、衰退していたため、連合国側は勝利の暁には分割される領土とみなしていた。コンスタンチノープルでの交渉は、戦略的、植民地的な利害によって強く動機づけられていた。各勢力は、地理的位置と資源から戦略的に重要なこの地域での影響力を拡大しようとした。ロシアは特に、地中海へのアクセスに不可欠なボスポラス海峡とダーダネルス海峡の支配に関心を寄せていた。一方、フランスとイギリスは植民地帝国を拡大し、この地域の資源、特に石油へのアクセスを確保しようとしていた。しかし、これらの話し合いはオスマン帝国領の将来に大きな影響を及ぼしたものの、その分割に関する最も重要で詳細な合意は、特に1916年のサイクス・ピコ協定において、後に正式なものとなったことに留意することが重要である。

イギリスの外交官マーク・サイクスとフランスの外交官フランソワ・ジョルジュ=ピコによって締結された1916年のサイクス=ピコ協定は、中東の歴史における重要な瞬間であり、第一次世界大戦後のこの地域の地政学的構成に大きな影響を与えた。この協定は、オスマン帝国の領土をイギリス、フランス、そしてある程度ロシアとの間で分割することを定めたものであったが、ロシアの参加は1917年のロシア革命によって無効となった。サイクス・ピコ協定は、中東におけるフランスとイギリスの勢力圏と支配圏を確立した。この協定により、フランスはシリアとレバノンを直接支配または影響力を得ることになり、イギリスはイラク、ヨルダン、パレスチナ周辺地域を同様に支配することになった。しかし、この協定は将来の国家の国境を正確に定めたものではなく、後の交渉と協定に委ねられた。

サイクス・ピコ協定の重要性は、中東の地理的空間に関する集団的記憶の「起源」としての役割にある。この協定は、しばしば現地の民族的、宗教的、文化的アイデンティティを無視した、ヨーロッパ列強のこの地域への帝国主義的介入と操作を象徴している。この協定は中東における国家の創設に影響を与えたが、これらの国家の実際の国境は、その後のパワーバランス、外交交渉、第一次世界大戦後に発展した地政学的現実によって決定された。サイクス・ピコ協定の結果は、戦後フランスとイギリスに与えられた国際連盟の委任統治に反映され、いくつかの近代中東国家の形成につながった。しかし、国境が引かれ、決定されたことは、しばしば現地の民族的、宗教的現実を無視するものであり、この地域に将来の紛争と緊張の種をまいた。この協定の遺産は、現代の中東でも議論と不満の対象であり続け、外国勢力による介入と分裂を象徴している。

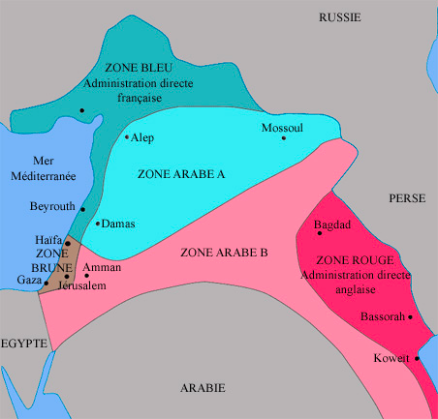

この地図は、1916年にフランスとイギリスの間で結ばれたサイクス・ピコ協定で定められたオスマン帝国の領土分割を、直接統治地域と影響力地域に分けて示したものである。

フランスの直接統治を示す「ブルーゾーン」は、後にシリアとレバノンとなる地域をカバーしていた。これは、フランスが戦略的な都市と沿岸地域を直接支配するつもりだったことを示している。イギリスの直接統治下にある「レッドゾーン」は、バグダッドやバスラといった主要都市を擁する将来のイラクと、分離された形で代表されたクウェートを包含していた。この地帯は、産油地域へのイギリスの関心と、ペルシャ湾への玄関口としての戦略的重要性を反映していた。パレスチナ(ハイファ、エルサレム、ガザなどを含む)を代表する「ブラウン・ゾーン」は、サイクス・ピコ協定では直接的な支配という点では明確に定義されていないが、一般的にはイギリスの影響力と関連している。後にイギリスの委任統治領となり、バルフォア宣言とシオニスト運動の結果、政治的緊張と対立の焦点となった。

アラブ地域A」と「アラブ地域B」は、それぞれフランスとイギリスの監督下でアラブの自治が認められた地域である。これは、戦時中に連合国がオスマン帝国に対するアラブの支持を獲得するために奨励した、ある種の自治や独立を求めるアラブの願望に対する譲歩と解釈された。この地図が示していないのは、連合国が戦時中に行った複雑で複数の約束であり、それらはしばしば矛盾していたため、合意が明らかになった後に地元住民の間に裏切られたという感情が生まれた。この地図はサイクス・ピコ協定を単純化したもので、実際はもっと複雑で、政治的発展や紛争、国際的圧力の結果、時とともに変化していった。

1917年のロシア革命後、ロシアのボリシェヴィキがサイクス・ピコ協定を暴露したことは、中東地域だけでなく、国際的にも大きな衝撃を与えた。ボリシェヴィキはこれらの密約を暴露することで、西欧列強、特にフランスとイギリスの帝国主義を批判し、自決と透明性の原則に対する自らのコミットメントを示そうとした。サイクス・ピコ協定は、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけてヨーロッパ列強を悩ませてきた複雑な外交問題である「東洋問題」の長いプロセスの始まりではなく、むしろ集大成であった。このプロセスは、衰退しつつあったオスマン帝国の領土に対する影響力の管理と共有に関わるものであり、サイクス=ピコ協定はこのプロセスにおける決定的な一歩であった。

この協定の下で、フランスはシリアとレバノンに勢力圏を確立し、イギリスはイラク、ヨルダン、パレスチナ周辺地域の支配権または影響力を獲得した。その意図は、大国の勢力圏の間に緩衝地帯を作ることであり、この地域で競合する利害を持つイギリスとロシアの間にもあった。このような構成は、インドやその他の地域での競争によって示された、これらの大国間の共存の難しさへの対応でもあった。サイクス・ピコ協定の公表はアラブ世界で強い反発を招き、戦争中にアラブの指導者たちと交わした約束に対する裏切りとみなされた。この暴露は欧米列強に対する不信感を悪化させ、この地域の民族主義的、反帝国主義的願望を煽った。中東の近代的な国境と、この地域に影響を与え続ける政治力学の基礎を築いたのである。

=アルメニア人虐殺

歴史的背景とジェノサイドの始まり(1915-1917年)

第一次世界大戦は、激しい紛争と政治的動乱の時代であったが、20世紀初頭の最も悲劇的な出来事の一つであるアルメニア人大虐殺によっても特徴づけられた。この大虐殺は1915年から1917年の間にオスマン帝国の青年トルコ政府によって行われたが、暴力行為や国外追放はそれ以前から始まり、それ以降も続いた。

この悲劇的な時期に、オスマン帝国の少数キリスト教民族であるアルメニア人は、強制追放、大量処刑、死の行進、計画的飢饉などのキャンペーンによって組織的に標的にされた。オスマン帝国当局は、「アルメニア人問題」と見なされるものを解決するための隠れ蓑と口実として戦争を利用し、アナトリアと帝国の他の地域からアルメニア人を排除する目的で、これらの行動を組織化した。犠牲者数の見積もりはさまざまだが、最大150万人のアルメニア人が死亡したと広く受け入れられている。アルメニア人虐殺は、アルメニア人の集団的記憶に深い足跡を残し、世界のアルメニア人コミュニティに永続的な影響を与えた。それは最初の近代的大量虐殺のひとつとされ、1世紀以上にわたってトルコとアルメニアの関係に影を落とした。

アルメニア人大虐殺の認定は、依然として微妙で議論の多い問題である。多くの国や国際機関がジェノサイドを公式に承認しているが、特にジェノサイドとすることに異議を唱えているトルコとの間では、一定の議論や外交的緊張が続いている。アルメニア人虐殺は国際法にも影響を及ぼし、ジェノサイドの概念の発展に影響を与え、将来的にこのような残虐行為を防止するための努力を促すことになった。この沈痛な出来事は、理解と和解に基づく共通の未来を築く上で、歴史的記憶と過去の不正義を認識することの重要性を強調している。

アルメニアの歴史的ルーツ

アルメニア人の歴史は豊かで古く、キリスト教時代のはるか昔にさかのぼる。アルメニアの民族主義的伝統と神話によれば、彼らのルーツは紀元前200年、あるいはそれ以前にまでさかのぼる。このことは、アルメニア人が何千年もの間、アルメニア高原を占領してきたことを示す考古学的、歴史的証拠によって裏付けられている。歴史上のアルメニアは、しばしば上アルメニアまたは大アルメニアと呼ばれ、現代のトルコ東部、アルメニア、アゼルバイジャン、グルジア、現代のイラン、イラクの一部を含む地域に位置していた。この地域は、紀元前9世紀から6世紀にかけて栄えた古代アルメニアの前身とされるウラルトゥ王国発祥の地である。アルメニア王国は、ウラルトゥ王国の滅亡後、アケメネス朝への統合を経て、紀元前6世紀初頭に正式に成立し、承認された。紀元前1世紀、ティグラン大王の治世に最盛期を迎え、一時はカスピ海から地中海まで広がる帝国を形成するまでに拡大した。

この地域におけるアルメニア人の存在の歴史的な深さは、西暦301年にアルメニアが初めてキリスト教を国教として公式に採用したことにも示されている。アルメニア人は、侵略やさまざまな外国帝国の支配にもかかわらず、何世紀にもわたって独自の文化的・宗教的アイデンティティを維持してきた。この長い歴史は、20世紀初頭のアルメニア人大虐殺のような深刻な苦難に直面しても、時代を超えて生き延びてきた強い民族的アイデンティティを形成してきた。アルメニアの神話や歴史的記述は、時に民族主義的な精神で誇張されることもあるが、アルメニア人の文化的豊かさと回復力に貢献してきた現実の重要な歴史に基づいている。

最初のキリスト教国家アルメニア

アルメニアは、キリスト教を国教として公式に採用した最初の王国という歴史的な称号を持っている。この記念すべき出来事は、ティリダテス3世の治世、西暦301年に起こったもので、アルメニア教会の初代教主となった聖グレゴリウス・イルミナトールの布教活動に大きな影響を受けた。アルメニア王国のキリスト教への改宗は、コンスタンティヌス帝の下、313年のミラノ勅令以降、キリスト教を支配的な宗教として採用し始めたローマ帝国の改宗に先行した。アルメニア人の改宗は、アルメニア人の文化的・民族的アイデンティティに大きな影響を与えた重要な過程であった。キリスト教の導入は、アルメニア教会や修道院の独特な建築を含むアルメニア文化や宗教芸術の発展につながり、5世紀初頭には聖メスロップ・マシュトッツによってアルメニア文字が創作された。このアルファベットのおかげで、聖書やその他の重要な宗教文書の翻訳を含むアルメニア文学が繁栄し、アルメニア人のキリスト教徒としてのアイデンティティが強化された。アルメニアは、しばしば競合する大帝国の国境に位置し、非キリスト教的な近隣諸国に囲まれていたため、最初のキリスト教国家としての地位は、政治的・地政学的な意味合いも持っていた。この区別は、何世紀にもわたってアルメニアの役割と歴史を形成するのに役立ち、キリスト教の歴史においても、中東とコーカサスの地域史においても、アルメニアを重要な存在にしている。

キリスト教が国教として採用された後のアルメニアの歴史は複雑で、しばしば波乱に満ちていた。数世紀にわたる近隣の帝国との紛争や相対的な自治の時代を経て、アルメニア人は7世紀のアラブ征服によって大きな変化を経験した。

預言者モハメッドの死後、イスラム教が急速に広まり、アラブ軍は西暦640年頃、アルメニアの大部分を含む中東の広大な地域を征服した。この時期、アルメニアはビザンチンの影響とアラブのカリフとの間に分断され、アルメニア地域の文化的・政治的分裂を招いた。アラブ支配の時代、そしてその後のオスマン帝国の時代、アルメニア人はキリスト教徒として、一般的に「ディミー」(イスラム法の下で保護されるが劣等な非ムスリムのカテゴリー)に分類された。この地位は彼らに一定の保護を与え、宗教を実践することを許したが、特定の税金や社会的・法的な制限も課された。歴史的アルメニアの大部分は、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけてオスマン帝国とロシア帝国の間に挟まれた。この時期、アルメニア人は自分たちの文化的・宗教的アイデンティティを守ろうと努める一方で、政治的課題の増大に直面した。

スルタン・アブデュルハミド2世の治世下(19世紀後半)、オスマン帝国は汎イスラム主義政策を採用し、オスマン帝国の力の衰退と内外の圧力に対応するため、帝国内の多様なイスラム民族を統合しようとした。この政策はしばしば帝国内の民族的・宗教的緊張を悪化させ、アルメニア人や他の非イスラム集団に対する暴力につながった。数万人のアルメニア人が殺害された19世紀末のハミディアンの虐殺は、1915年のアルメニア人虐殺に先行し、その伏線となった暴力の悲劇的な例である。これらの出来事は、ナショナリズムの台頭と帝国の衰退に直面し、政治的・宗教的統一を求める帝国において、アルメニア人やその他の少数民族が直面した困難を浮き彫りにした。

サン=ステファノ条約とベルリン会議

1878年に調印されたサン=ステファノ条約は、国際的な関心事となったアルメニア問題にとって極めて重要な出来事であった。この条約は、ロシア帝国の手によってオスマン帝国が大敗を喫した1877年から1878年にかけての露土戦争の末期に締結された。サン・ステファノ条約で最も注目すべき点のひとつは、オスマン帝国にキリスト教徒、特にアルメニア人に有利な改革を実施し、彼らの生活条件を改善することを要求した条項である。これは暗黙のうちに、アルメニア人が受けた虐待と国際的な保護の必要性を認めたものであった。しかし、条約で約束された改革の実施はほとんど効果がなかった。戦争と内圧で弱体化したオスマン帝国は、外国による内政干渉と受け取られかねない譲歩を認めたがらなかった。さらに、サン=ステファノ条約の条項は同年末のベルリン会議によって見直され、イギリスやオーストリア=ハンガリーをはじめとする他の大国の懸念に応える形で調整された。

それでもベルリン会議はオスマン帝国に改革を求める圧力をかけ続けたが、実際にはアルメニア人の状況を改善することはほとんどできなかった。このような行動の欠如は、帝国内の政治的不安定と民族的緊張の高まりと相まって、最終的には1890年代のハミディアンの虐殺、そして後の1915年のアルメニア人大虐殺へとつながる環境を作り出した。サン・ステファノ条約によるアルメニア問題の国際化は、ヨーロッパ列強がキリスト教少数派の保護を名目に、オスマン帝国により直接的な影響力を行使し始めた時代の幕開けとなった。しかし、改革の約束とその実行の間のギャップは、アルメニア人に悲劇的な結末をもたらす、果たされなかった約束の遺産を残した。

19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけては、オスマン帝国のアルメニア人とアッシリア人の共同体にとって、大きな暴力の時代であった。特に1895年と1896年は、スルタン・アブデュルハミド2世にちなんでハミディアンの虐殺と呼ばれる大規模な虐殺が行われた。これらの虐殺は、抑圧的な税金、迫害、サンステファノ条約で約束された改革の欠如に対するアルメニア人の抗議に対応して実行された。1908年のクーデターで政権を握った改革派民族主義運動である青年トルコ人は、当初オスマン帝国内の少数民族の希望の源とみなされていた。しかし、この運動の急進派は、結局、前任者たちよりもさらに攻撃的で民族主義的な政策を採用した。均質なトルコ国家を建設する必要性を確信した彼らは、アルメニア人やその他の非トルコ系少数民族を国家構想の障害物とみなした。アルメニア人に対する組織的な差別が強まり、反逆罪や帝国の敵、特にロシアとの共謀に対する非難が煽られた。この疑惑と憎悪の雰囲気が、1915年に始まった大量虐殺の温床となった。この大量虐殺キャンペーンの最初の行為のひとつが、1915年4月24日にコンスタンチノープルで行われたアルメニア人知識人と指導者の逮捕と殺害であった。

集団追放、シリアの砂漠への死の行進、虐殺が続き、殺害されたアルメニア人は150万人にのぼると推定されている。死の行進に加え、黒海で意図的に沈められた船にアルメニア人が強制的に乗せられたという報告もある。こうした恐怖に直面し、生き延びるためにイスラム教に改宗したアルメニア人もいれば、身を隠したり、クルド人など同情的な隣人に保護されたアルメニア人もいた。同じ頃、アッシリア人も1914年から1920年にかけて同様の残虐行為に苦しんでいた。オスマン帝国に認められたミレット(自治共同体)として、アッシリア人はある程度の保護を享受していたはずだった。しかし、第一次世界大戦とトルコのナショナリズムの中で、彼らは組織的な絶滅作戦の対象となった。これらの悲劇的な出来事は、差別、非人間化、過激主義がいかに集団暴力行為につながるかを示している。アルメニア人虐殺とアッシリア人虐殺は、このような残虐行為が二度と起こらないようにするために、追悼、認識、虐殺防止の重要性を強調する歴史の暗黒の章である。

トルコ共和国とジェノサイドの否定へ向けて

1919年、連合国によるイスタンブールの占領と、戦争中に行われた残虐行為に責任を負うオスマン・トルコ政府高官を裁くための軍法会議の設置は、特にアルメニア人虐殺をはじめとする犯罪に正義をもたらす試みであった。しかし、アナトリアの情勢は不安定で複雑なままだった。ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクに率いられたトルコの民族主義運動は、オスマン帝国を解体し、トルコに厳しい制裁を課した1920年のセーヴル条約の条項を受けて急速に発展した。ケマル派はこの条約を屈辱であり、トルコの主権と領土保全に対する脅威であるとして拒否した。

条約によって保護されていたトルコ国内のギリシア正教徒が、ギリシアとトルコの対立に巻き込まれたのである。1919年から1922年にかけてのギリシャとトルコの戦争によって、ギリシャ系住民とトルコ系住民の間の緊張は大規模な暴力と人口交換に発展した。第一次世界大戦中、ダーダネルス海峡の防衛者として名を馳せたムスタファ・ケマルは、青年トルコの有力メンバーであったが、アルメニア人虐殺を「恥ずべき行為」と述べたと引用されることがある。しかし、こうした主張には論争や歴史的な議論がつきまとう。大虐殺に関するケマルと新生トルコ共和国の公式見解は、大虐殺を否定し、意図的な絶滅政策ではなく、戦時状況や内乱によるものだとするものだった。

アナトリアへの抵抗とトルコ共和国樹立の闘争の間、ムスタファ・ケマルとその支持者たちは、統一されたトルコの国民国家を建設することに集中し、この国家プロジェクトを分裂させたり弱体化させたりしたかもしれない過去の出来事を認めることは避けられた。それゆえ、第一次世界大戦後の時期は、大きな政治的変化、紛争後の正義の試み、そしてこの地域における新たな国民国家の出現によって特徴づけられ、新生トルコ共和国はオスマン帝国の遺産から独立して独自のアイデンティティと政治を定義しようとした。

トルコの建国

ローザンヌ条約と新しい政治的現実(1923年)

1923年7月24日に調印されたローザンヌ条約は、トルコと中東の現代史において決定的な転換点となった。主にムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルク率いるトルコ国民の抵抗によるセーブル条約の失敗後、連合国は再交渉を余儀なくされた。戦争で疲弊し、領土保全に固執するトルコの現実に直面した連合国は、トルコの民族主義者たちによって確立された新たな政治的現実を認めざるを得なかった。ローザンヌ条約は、国際的に認められた現代トルコ共和国の国境を確立し、クルド人国家の創設を規定し、アルメニア人の一定の保護を認めていたセーヴル条約の条項を取り消した。ローザンヌ条約は、クルド人国家の創設やアルメニア人に対するいかなる措置も盛り込まなかったことで、「クルド人問題」と「アルメニア人問題」に対する国際レベルでの扉を閉ざし、これらの問題は未解決のまま残された。

同時に、この条約はギリシャとトルコの間の人口交換を正式なものとし、「トルコ領土からのギリシャ人の追放」という、強制的な人口移動とアナトリアとトラキアにおける歴史的共同体の終焉という痛ましいエピソードにつながった。ローザンヌ条約調印後、第一次世界大戦中に政権を握っていた青年トルコ人として知られる連合進歩委員会(CUP)は正式に解散した。その指導者の何人かは亡命し、何人かはアルメニア人虐殺や戦争の破壊的政策に関与したことへの報復として暗殺された。

その後の数年間で、トルコ共和国は統合され、アナトリアの主権と完全性を守ることを目的とした民族主義団体がいくつか生まれた。宗教はナショナル・アイデンティティの構築に一役買い、「キリスト教西側」と「イスラム教アナトリア」の区別がしばしば描かれた。この言説は、国家の結束を強化し、トルコ国家への脅威とみなされる外国の影響や介入に対する抵抗を正当化するために用いられた。それゆえ、ローザンヌ条約は現代トルコ共和国の礎石とみなされており、その遺産はトルコの国内政策や外交政策、近隣諸国や国境内の少数民族との関係を形成し続けている。

ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの到着とトルコ民族抵抗運動(1919年)

1919年5月、ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクがアナトリアに到着したことは、トルコの独立と主権を求める闘いの新たな局面の始まりを意味した。連合国の占領とセーヴル条約に反対した彼は、トルコ民族抵抗運動の指導者としての地位を確立した。その後の数年間、ムスタファ・ケマルはいくつかの重要な軍事作戦を指揮した。1921年のアルメニア人との戦い、国境を再定義するための南アナトリアでのフランスとの戦い、1919年にイズミル市を占領し西アナトリアに進出してきたギリシャ人との戦いなどである。これらの紛争は、オスマン帝国の廃墟に新しい国家を樹立しようとするトルコの民族主義運動の重要な要素であった。この地域におけるイギリスの戦略は複雑だった。一方ではギリシア人とトルコ人、他方ではトルコ人とイギリス人の対立が拡大する可能性に直面したイギリスは、ギリシア人とトルコ人を互いに戦わせることで、特に石油が豊富で戦略的に重要な領土であるイラクなど、他の場所に努力を集中させることができるという利点を考えた。

ギリシャ・トルコ戦争は1922年、トルコの勝利とギリシャのアナトリアからの撤退で頂点に達し、ギリシャにとっては小アジアの大惨事となり、トルコ民族主義勢力にとっては大勝利となった。ムスタファ・ケマルによる軍事作戦の勝利により、セーヴル条約の再交渉が可能となり、1923年にはトルコ共和国の主権を認め、国境を再定義するローザンヌ条約が締結された。ローザンヌ条約と同時に、ギリシャとトルコの人口交換条約が締結された。これにより、ギリシャ正教徒とトルコ系イスラム教徒が両国の間で強制的に交換され、より民族的に均質な国家を目指すことになった。フランス軍を撃退し、国境協定を締結し、ローザンヌ条約に調印した後、ムスタファ・ケマルは1923年10月29日にトルコ共和国を宣言し、初代大統領に就任した。共和国宣言は、多民族・多宗教国家であったオスマン帝国の残滓の上に、近代的で世俗的かつ民族主義的なトルコ国家を建設しようとしたムスタファ・ケマルの努力の集大成であった。

国境の形成とモスルとアンティオキア問題

1923年にローザンヌ条約が締結され、トルコ共和国が国際的に承認され、国境が再定義された後も、特にアンティオキアとモスル地域に関する未解決の国境問題が残っていた。これらの問題を解決するためには、さらなる交渉と国際機関の介入が必要であった。アンティオキア市は、歴史的に豊かで文化的に多様なアナトリア南部に位置し、アンティオキアを含むシリアの委任統治権を行使していたトルコとフランスの間で争いの対象となっていた。多文化的な過去と戦略的重要性を持つこの都市は、両国の緊張の的だった。結局、交渉の末、アンティオキアはトルコに与えられたが、この決定は論争と緊張の種となった。モスル地域の問題はさらに複雑だった。石油が豊富なモスル地域は、トルコとイラクを委任統治していたイギリスの両方が領有権を主張していた。トルコは、歴史的、人口学的な論拠に基づいて、モスル地域を自国の国境に含めたいと考え、イギリスは、戦略的、経済的な理由、特に石油の存在から、モスル地域をイラクに含めることを支持した。

この紛争を解決するため、国際連合の前身である国際連盟が介入した。交渉の末、1925年に合意に達した。この協定では、モスル地域はイラクの一部となるが、トルコは特に石油収入の分配という形で金銭的補償を受けることになった。この協定には、トルコがイラクとその国境を公式に承認することも定められていた。この決定は、トルコ、イラク、イギリス間の関係を安定させる上で極めて重要であり、イラクの国境を定義する上で重要な役割を果たし、中東の将来の発展に影響を与えた。これらの交渉とその結果としての合意は、中東における第一次世界大戦後の力学の複雑さを物語っている。この地域の近代的な国境が、歴史的な主張、戦略的・経済的な考慮、国際的な介入などが入り混じって形成され、しばしば地元住民の利益よりも植民地支配国の利益を反映したものであったことを示している。

ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの急進的改革

第一次世界大戦後のトルコは、新トルコ共和国の近代化と世俗化を目指したムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクによる急進的な改革と変革によって特徴づけられる。1922年、トルコ議会がオスマン・トルコのスルタン制を廃止するという重要な一歩を踏み出し、数世紀にわたる帝国支配に終止符を打ち、トルコの新首都アンカラに政治権力を集中させた。1924年には、カリフ制の廃止というもうひとつの大きな改革が行われた。この決定により、オスマン帝国の特徴であったイスラム教の宗教的・政治的指導力が排除され、国家の世俗化への決定的な一歩となった。この廃止と並行して、トルコ政府は、国内の宗教問題を監督・規制するための機関であるディヤネット(宗教問題大統領府)を創設した。この組織の目的は、宗教問題を国家の管理下に置き、宗教が政治的目的のために利用されないようにすることだった。その後、ムスタファ・ケマルは、しばしば「権威主義的近代化」と呼ばれる、トルコの近代化を目指した一連の改革を実施した。これらの改革には、教育の世俗化、服装規定の改革、グレゴリオ暦の採用、イスラム宗教法に代わる民法の導入などが含まれた。

均質なトルコ国民国家を作る一環として、少数民族や異なる民族グループに対する同化政策が実施された。これらの政策には、すべての国民にトルコ姓を名乗らせること、トルコ語とトルコ文化を採用するよう奨励すること、宗教学校を閉鎖することなどが含まれた。これらの施策は、トルコ人という共通のアイデンティティのもとに国民を統一することを目指したが、同時に少数民族の文化的権利や自治の問題も提起した。これらの急進的な改革はトルコ社会を変革し、近代トルコの基礎を築いた。ムスタファ・ケマルの、近代的で世俗的で単一的な国家を作りたいという願望を反映したものであり、同時に戦後の複雑な民族主義的願望を反映したものであった。これらの変化はトルコの歴史に大きな影響を与え、今日もトルコの政治と社会に影響を与え続けている。

1920年代から1930年代にかけてのトルコは、ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの指導の下、国の近代化と西欧化を目指した一連の急進的な改革によって特徴づけられた。これらの改革は、トルコの社会、文化、政治生活のほとんどすべての側面に影響を与えた。最初の施策のひとつが教育省の創設であり、教育制度の改革とケマル主義イデオロギーの推進において中心的な役割を果たした。1925年、最も象徴的な改革のひとつは、トルコ国民の外見と服装を近代化する政策の一環として、伝統的なフェズに代わってヨーロッパ帽を着用させたことである。

法改正も重要なもので、スイス民法をはじめとする西欧のモデルに触発された法規範が採用された。これらの改革の目的は、シャリーア(イスラム法)に基づくオスマン帝国の法制度を、近代的で世俗的な法制度に置き換えることだった。トルコはまた、メートル法とグレゴリオ暦を採用し、休息日を(イスラム教国で伝統的に守られてきた)金曜日から日曜日に変更することで、西欧の標準に合わせた。最も急進的な改革のひとつは、1928年にアルファベットをアラビア文字から修正ラテン文字に変更したことである。この改革の目的は、識字率の向上とトルコ語の近代化にあった。1931年に設立されたトルコ歴史研究所は、トルコの歴史を再解釈し、トルコの国民的アイデンティティを促進するための幅広い取り組みの一環であった。同じ精神で、トルコ語の純化政策はアラビア語やペルシャ語の借用を排除し、トルコ語とトルコ文化の古代の起源と優位性を主張する民族主義的イデオロギーである「太陽語」理論を強化することを目的としていた。

クルド人問題については、ケマル主義政府は同化政策を追求し、クルド人を「山のトルコ人」とみなし、彼らをトルコの国民的アイデンティティに統合しようとした。この政策は、特に1938年のクルド人および非イスラム系住民への弾圧において、緊張と対立を招いた。ケマリスト時代はトルコにとって大きな変革の時代であり、近代的で世俗的かつ均質な国民国家を作ろうとする努力が顕著であった。しかし、こうした改革は、近代化を目指した進歩的なものであった一方で、権威主義的な政策や同化への努力も伴っており、現代のトルコに複雑で、時に物議を醸す遺産を残している。

1923年の共和国建国から始まったトルコのケマリスト時代は、国家の中央集権化、国有化、世俗化、そして社会のヨーロッパ化を目指した一連の改革によって特徴づけられた。ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクが主導したこれらの改革は、進歩と近代化の障害とみなされていたオスマン帝国の帝国的・イスラム的過去との決別を目指した。その目的は、西洋の価値観や基準に沿った近代的なトルコを作ることだった。このような観点から、オスマン帝国とイスラムの遺産はしばしば否定的に描かれ、後進性や蒙昧主義と結びつけられた。西側へのシフトは、政治、文化、法律、教育、そして日常生活においても顕著であった。

多党制と近代化と伝統の緊張関係(1950年以降)

しかし、1950年代に多党制が導入されると、トルコの政治状況は変わり始めた。共和国人民党(CHP)の下で一党独裁国家として運営されてきたトルコは、政治的多元主義に門戸を開き始めた。この移行に緊張がなかったわけではない。ケマル主義時代に疎外されがちだった保守派は、ケマル主義改革の一部、特に世俗主義と西欧化に関する改革に疑問を呈し始めた。世俗主義と伝統的価値観、西欧化とトルコ的・イスラム的アイデンティティの間の論争は、トルコ政治において繰り返し取り上げられるテーマとなった。保守主義政党やイスラム主義政党が台頭し、ケマル主義の遺産に疑問を呈し、特定の伝統的・宗教的価値観への回帰を訴えている。

この政治的ダイナミズムは時に弾圧や緊張を招き、さまざまな政権が多様化する政治環境の中で権力を強化しようとしている。特に1960年、1971年、1980年の軍事クーデター、そして2016年のクーデター未遂のような政治的緊張と抑圧の時期は、近代化と伝統、世俗主義と宗教性、西欧化とトルコ的アイデンティティのバランスを取るというトルコが直面した挑戦の証である。1950年以降のトルコでは、ケマリストの遺産と伝統的価値観への回帰を求める一部の国民の願望との間で、複雑かつ時に相反するバランスの再構築が見られ、現代トルコ社会における近代化と伝統の間の継続的な緊張を反映している。

トルコとその内的課題:民族と宗教の多様性の管理

西側諸国の戦略的同盟国として、特に1952年のNATO加盟以来、トルコは西側諸国との関係と自国内の政治力学を調和させなければならなかった。1950年代に導入された複数政党制は、より民主的な統治形態への移行を反映したものであり、この和解における重要な要素であった。しかし、この移行は不安定な時期や軍事介入によって特徴づけられてきた。実際、トルコは1960年、1971年、1980年、そして2016年と、およそ10年ごとに軍事クーデターを経験している。これらのクーデターは、秩序を回復し、トルコ共和国の原則、特にケマル主義と世俗主義を守るために必要であるとして、しばしば軍によって正当化された。各クーデターの後、軍は一般的に文民統治に戻すために新たな選挙を招集したが、軍はケマル主義イデオロギーの保護者としての役割を果たし続けた。

しかし、2000年代以降、トルコの政治情勢は、特に公正発展党(AKP)をはじめとする保守・イスラム主義政党の台頭によって大きく変化した。レジェップ・タイイップ・エルドアン率いるAKPは、いくつかの選挙で勝利し、長期にわたって政権を維持した。AKP政権は、より保守的でイスラム的な価値観を標榜しているにもかかわらず、軍によって打倒されたことはない。これは、ケマル主義の原則から逸脱しているとみなされた政権がしばしば軍事介入の対象となった過去数十年とは異なることを意味する。トルコの保守政権が相対的に安定していることは、軍と民間の政党間の力の均衡が崩れていることを示唆している。この背景には、軍の政治力を削ぐことを目的とした一連の改革と、保守的でイスラム的な価値観を反映した統治をますます受け入れるようになったトルコ国民の態度の変化がある。現代トルコの政治力学は、世俗的なケマリスト主義の伝統と、保守的でイスラム主義的な傾向の高まりの間を行き来しながら、複数政党主義と西側諸国との同盟へのコミットメントを維持している国の課題を反映している。

現代のトルコは、民族的・宗教的多様性の管理など、さまざまな内的課題に直面してきた。特にクルド人に対する同化政策は、トルコのナショナリズムを強化する上で重要な役割を果たしてきた。このような状況は、特にオスマン帝国下で特定の宗教的少数派に与えられたミレット(自治共同体)の地位の恩恵を受けていない少数派クルド人との緊張や対立につながっている。20世紀におけるヨーロッパの反ユダヤ主義や人種差別主義の影響もトルコに及んだ。1930年代、ヨーロッパの政治的・社会的潮流の影響を受けた差別的・排外主義的な思想がトルコにも現れ始めた。このため、1934年にトラキアでユダヤ人に対するポグロムが発生し、ユダヤ人社会が標的となり、攻撃され、避難を余儀なくされるなど、悲劇的な出来事が起こった。

さらに、1942年に導入された富裕税法(Varlık Vergisi)も、ユダヤ人、アルメニア人、ギリシア人など、トルコ人やイスラム教徒以外の少数民族に主に影響を与えた差別的措置であった。この法律は、非イスラム教徒に不釣り合いなほど高い法外な税金を富に課し、払えない者は、特にトルコ東部のアシュカレの労働収容所に送られた。これらの政策や出来事は、トルコ社会における民族的・宗教的緊張を反映したものであり、トルコのナショナリズムが時に排他的・差別的に解釈された時代でもあった。また、多数の民族や宗教集団が共存するアナトリアのような多様な地域で国民国家が形成される過程の複雑さを浮き彫りにした。この時期のトルコにおける少数民族の扱いは、国内の多様性を管理しながら統一された国民的アイデンティティを模索するトルコが直面した課題を反映し、今でも繊細で論争の的となっている。これらの出来事は、トルコの異なる民族・宗教間の関係にも長期的な影響を与えた。

世俗主義と世俗主義の分離:ケマリスト時代の遺産

世俗化と世俗主義の区別は、異なる歴史的・地理的文脈における社会的・政治的力学を理解する上で重要である。世俗化とは、社会、制度、個人が宗教的影響や規範から離れ始める歴史的・文化的プロセスを指す。世俗化された社会では、宗教が公共生活、法律、教育、政治、その他の分野に対する影響力を徐々に失っていく。このプロセスは、必ずしも個人が個人レベルで宗教的でなくなることを意味するのではなく、むしろ宗教が公的な問題や国家から切り離された私的な問題となることを意味する。世俗化は多くの場合、近代化、科学技術の発展、社会規範の変化と関連している。一方、世俗主義とは、国家が宗教問題に関して中立であることを宣言する制度的・法的政策である。国家を宗教機関から切り離し、政府の決定や公共政策が特定の宗教教義に影響されないようにする決定である。世俗主義は、深い宗教社会と共存することが可能である。理論的には、世俗主義は信教の自由を保障し、すべての宗教を平等に扱い、特定の宗教を優遇することを避けることを目的としている。

歴史的、現代的な例を見ると、この2つの概念の組み合わせはさまざまである。例えば、ヨーロッパ諸国の中には、国家と特定の教会との公式な結びつきを維持しながら、大幅な世俗化を行った国もある(イギリスとイングランド国教会など)。一方、フランスのように厳格な世俗主義(ライシテ)を採用しながらも、歴史的に宗教的伝統が色濃く残っている国もある。トルコでは、ケマル主義の時代にモスクと国家の分離という厳格な世俗主義が導入されたが、一方でイスラム教が人々の私生活において重要な役割を果たし続けた社会でもあった。ケマリストの世俗主義政策は、西欧のモデルからインスピレーションを得ながら、イスラム教を中心とした社会的・政治的組織の長い歴史を持つ社会の複雑な背景を乗り越え、トルコの近代化と統一を目指した。

第二次世界大戦後のトルコでは、特に少数民族に影響を及ぼし、国内の民族的・宗教的緊張を悪化させる事件が頻発した。その中でも、1955年にテッサロニキ(当時ギリシャ)にあったムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの生家が爆破された事件は、トルコ近代史における最も悲劇的な出来事のひとつ、イスタンブール・ポグロムのきっかけとなった。イスタンブール・ポグロムは、1955年9月6日から7日にかけての事件としても知られ、主に市内のギリシャ人コミュニティに対するものであったが、アルメニア人やユダヤ人をはじめとする他の少数民族に対しても行われた一連の暴力的な襲撃事件であった。これらの攻撃は、アタテュルクの生家が爆破されるという噂に端を発し、ナショナリストや反マイノリティの感情によって悪化した。暴動は大規模な財産の破壊、暴力、多くの人々の避難という結果をもたらした。

この出来事はトルコにおけるマイノリティの歴史の転換点となり、イスタンブールのギリシャ人人口は大幅に減少し、他のマイノリティの間では全般的な不安感が広がった。イスタンブールのポグロムはまた、国民的アイデンティティ、民族的・宗教的多様性、多様な国民国家における調和の維持という課題をめぐるトルコ社会の根底にある緊張を明らかにした。それ以来、トルコにおける民族的・宗教的マイノリティの割合は、移住や同化政策、時には共同体間の緊張や対立など、さまざまな要因によって大幅に減少してきた。現代のトルコは寛容で多様性のある社会というイメージを広めようとしているが、このような歴史的事件の遺産は、異なるコミュニティ間の関係や、少数民族に対する国の政策に影響を与え続けている。トルコにおける少数民族の状況は、多様性を管理し、国境内のすべての共同体の権利と安全を守る上で、多くの国家が直面している課題を示しており、依然として微妙な問題である。

アレビ人

トルコ共和国建国がアレヴィ派に与えた影響(1923年)

1923年のトルコ共和国建国とムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクによる世俗主義改革は、アレヴィ派を含むトルコのさまざまな宗教的・民族的集団に大きな影響を与えた。イスラム教の中でも独特の宗教的・文化的集団であり、主流のスンナ派とは異なる信仰を実践するアレヴィは、トルコ共和国の建国をある種の楽観主義をもって迎えた。世俗主義と世俗化が約束されたことで、しばしば差別の対象となり、時には暴力の対象となっていたオスマン帝国時代と比べ、より大きな平等と信教の自由が期待されたのである。

しかし、1924年にカリフ制が廃止されると、トルコ政府は宗教問題を規制し、管理しようとした。ディヤネットは宗教を国家が統制し、共和制的・世俗的価値観に適合したイスラム教を推進することを目的としていたが、実際にはトルコの多数派であるスンニ派を優遇することが多かった。この政策はアレヴィ・コミュニティに問題を引き起こしてきた。アレヴィ・コミュニティは、自分たちの宗教的信条や慣習にそぐわないイスラム教を国家が推進することで、疎外されていると感じてきた。トルコ共和国時代のアレヴィの状況は、頻繁に迫害を受けていたオスマン帝国時代に比べればはるかに改善されたものの、宗教的承認や権利に関する課題に直面し続けた。

長年にわたり、アレヴィ教徒は自分たちの礼拝所(セメヴィ)を公式に認め、宗教問題における公正な代表権を求めて闘ってきた。トルコでは世俗主義と市民権の面で進歩が見られるものの、アレヴィ問題は依然として重要な問題であり、世俗的な枠組みの中で宗教と民族の多様性を管理するというトルコの広範な課題を反映している。したがって、トルコにおけるアレヴィの状況は、近代化と世俗化の文脈における国家、宗教、マイノリティの複雑な関係の一例であり、国家政策がいかに国家内の社会的・宗教的力学に影響を与えうるかを示している。

1960年代におけるアレヴィの政治的関与

1960年代、トルコは政治的・社会的に大きな変革期を迎え、さまざまな意見や利害を代表する政党や運動が出現した。1960年代は政治的ダイナミズムの時代であり、アレビのような少数民族を含む政治的アイデンティティや要求がより明確に表現されるようになった。この時期に最初のアレヴィ政党が設立されたことは重要な進展であり、このコミュニティが政治プロセスに関与し、その特定の利益を守ろうとする意欲が高まったことを反映している。独特の信仰と慣習を持つアレヴィは、しばしば自分たちの宗教的・文化的権利の承認と尊重の拡大を求めてきた。しかし、他の政党、特に左派や共産主義の政党が、クルド人やアレヴィの有権者の要求に応えてきたことも事実である。社会正義、平等、マイノリティの権利という理念を推進することで、これらの政党はこれらのコミュニティから大きな支持を集めてきた。少数者の権利、社会正義、世俗主義の問題は、しばしば彼らの政治綱領の中心にあり、それはアレヴィやクルド人の懸念と共鳴していた。

政治的緊張の高まりとイデオロギー的分裂が顕著だった1960年代のトルコでは、左翼政党は下層階級や少数民族、社会から疎外された人々の支持者と見なされることが多かった。そのため、アレヴィ政党はこのコミュニティを直接代表するものの、社会正義や平等といったより広範な問題を扱う、より確立された政党の影に隠れてしまうこともあった。このように、この時期のトルコ政治は、政治的アイデンティティと所属の多様性と複雑性の高まりを反映しており、マイノリティの権利、社会正義、アイデンティティの問題がトルコの新興政治状況においていかに中心的な役割を果たしたかを物語っている。

1970年代と1980年代、過激主義と暴力に直面するアレヴィ派

1970年代は、トルコの社会的・政治的緊張が非常に高まった時期であり、二極化の進展と過激派グループの出現が顕著であった。この時期、トルコでは、民族主義・超国家主義グループに代表される極右勢力が知名度と影響力を増した。このような過激主義の台頭は、特にアレヴィのような少数民族に悲劇的な結果をもたらした。アレヴィは、多数派のスンニ派イスラム教とは異なる信仰と実践を持つため、しばしば超国家主義的・保守的集団の標的にされてきた。これらのグループは、民族主義的、時には宗派的なイデオロギーに煽られ、虐殺やポグロムを含むアレヴィ・コミュニティに対する暴力的な攻撃を行ってきた。最も悪名高い事件としては、1978年のマラシュや1980年のチョルムでの虐殺が挙げられる。これらの事件の特徴は、極端な暴力、大量殺人、斬首や切断のシーンを含むその他の残虐行為であった。これらの襲撃事件は孤立した事件ではなく、アレヴィに対する暴力と差別のより広い傾向の一部であり、トルコの社会的分裂と緊張を悪化させた。

1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけての暴力は、1980年の軍事クーデターへとつながる不安定化の一因となった。クーデター後、軍は秩序と安定を回復するため、極右や極左を含む多くの政治グループを取り締まる体制を確立した。しかし、根底にある差別や異なるコミュニティ間の緊張の問題は依然として残っており、トルコの社会的・政治的結束に継続的な課題を投げかけている。したがって、トルコにおけるアレヴィの状況は、政治的分極化と過激主義の台頭という状況の中で、宗教的・民族的マイノリティが直面する困難の痛切な例である。また、社会平和と国民統合を維持するためには、すべてのコミュニティの権利を尊重する包括的なアプローチが必要であることも浮き彫りにしている。

1990年代のシヴァスとガジの悲劇

1990年代のトルコでは、特にアレヴィ・コミュニティに対する緊張と暴力が続き、いくつかの悲劇的な攻撃の標的となった。1993年、特に衝撃的な事件がトルコ中部の町シヴァスで起こった。1993年7月2日、ピル・スルタン・アブダルの文化祭開催中に、アレヴィの知識人、芸術家、作家の一団と観客が過激派の暴徒に襲撃された。彼らが滞在していたマドゥマク・ホテルは放火され、37人が死亡した。シヴァスの大虐殺あるいはマドゥマクの悲劇として知られるこの事件は、トルコ現代史における最も暗い出来事のひとつであり、過激主義と宗教的不寛容に対するアレヴィの脆弱性を浮き彫りにした。その2年後の1995年、イスタンブールのガジ地区(アレヴィの人口が多い地区)でも暴力事件が起きた。アレヴィ教徒がよく利用するカフェに何者かが発砲し、1人が死亡、数人が負傷した後、激しい衝突が発生した。その後も暴動や警察との衝突が続き、多くの死傷者を出した。

これらの事件は、アレヴィ・コミュニティとトルコ国家間の緊張を悪化させ、アレヴィに対する偏見と差別の根強さを浮き彫りにした。また、トルコにおける少数民族の保護や、すべての国民の安全と正義を保障する国家の能力についても疑問を投げかけた。シヴァスとガジでの暴力事件は、トルコにおけるアレヴィの状況に対する認識の転換点となり、アレヴィの権利の承認と、アレヴィ独自の文化的・宗教的アイデンティティに対する理解と尊重を求める声が高まった。これらの悲劇的な出来事はトルコの集団的記憶に刻まれたままであり、宗教の多様性と平和的共存という点でトルコが直面している課題を象徴している。

AKP政権下のアレヴィ:アイデンティティの課題と対立

2002年にレジェップ・タイイップ・エルドアン率いる公正発展党(AKP)が政権に就いて以来、トルコではアレヴィ・コミュニティを含むイスラム教と宗教的少数派に対する政策に大きな変化が見られた。AKPはイスラム主義や保守的な傾向を持つ政党として認識されることが多いが、スンニ派を優遇していると批判され、宗教的少数派、特にアレヴィ教徒の間で懸念が高まっている。AKP政権下で、政府はディヤネット(宗教総裁府)の役割を強化したが、ディヤネットはスンニ派のイスラム教を推進していると非難された。これは、支配的なスンナ派とは明らかに異なるイスラム教を実践するアレヴィ・コミュニティに問題を引き起こした。アレヴィ教徒は伝統的なモスクには礼拝に行かず、宗教儀式や集会には「セメヴィ」を使う。しかし、ディヤネットは公式にセメヴィを礼拝所として認めておらず、これがアレヴィの不満と対立の原因となっている。政府はすべての宗教的・民族的共同体を均質なスンニ派トルコ人のアイデンティティに統合しようとしていると受け止められているため、同化の問題もアレヴィにとっては懸念事項である。この政策は、動機と文脈は異なるものの、ケマリスト時代の同化努力を彷彿とさせる。

アレヴィは民族的にも言語的にも多様な集団であり、トルコ語を話すメンバーとクルド語を話すメンバーがいる。彼らのアイデンティティは、その明確な信仰によって定義される部分が大きいが、文化的、言語的な面では他のトルコ人やクルド人とも共通している。しかし、彼ら独自の宗教的実践と疎外されてきた歴史が、トルコ社会の中で彼らを際立たせている。2002年以降のトルコにおけるアレヴィの状況は、国家と宗教的少数派との間に続く緊張関係を反映している。それは、信教の自由、マイノリティの権利、そして世俗的で民主的な枠組みの中で多様性を受け入れる国家の能力に関する重要な問題を提起している。トルコがこれらの問題をどのように処理するかは、国内政策と国際舞台におけるトルコのイメージの重要な側面であり続けている。

イラン

20世紀初頭の課題と外部からの影響

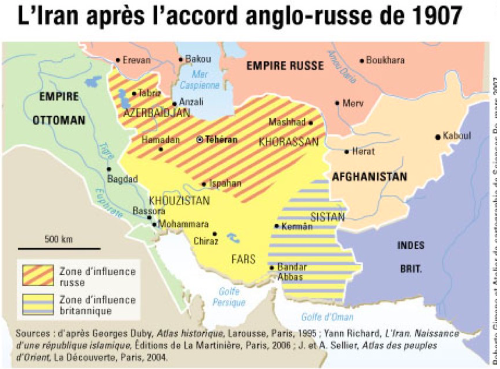

イランにおける近代化の歴史は、外部からの影響と内部の力学がどのように国の行く末を形作るかを示す、興味深いケーススタディである。20世紀初頭、イラン(当時はペルシャ)は権威主義的な近代化の過程で頂点に達する複数の課題に直面した。第一次世界大戦までの数年間、特に1907年、イランは崩壊の危機に瀕していた。イランは領土を大きく失い、行政的・軍事的弱体化に苦しんでいた。特にイラン軍は、国家の影響力を効果的に管理することも、外国の侵入から国境を守ることもできなかった。この困難な状況は、帝国主義大国、特にイギリスとロシアの利害の対立によって悪化した。1907年、歴史的な対立にもかかわらず、イギリスとロシアは英露同盟を締結した。この協定の下で、両者はイランにおける勢力圏を共有し、ロシアは北部を、イギリスは南部を支配することになった。この協定は、この地域におけるそれぞれの帝国主義的利益を黙認するものであり、イランの政策に大きな影響を与えた。

英露同盟はイランの主権を制限しただけでなく、強力な中央勢力の育成を妨げた。特にイギリスは、自国の利益、特に石油へのアクセスと通商路の支配を脅かす可能性のある中央集権的で強力なイランという構想に懐疑的であった。このような国際的な枠組みは、イランに大きな試練をもたらし、近代化への道筋に影響を与えた。外国の帝国主義的利益と国内の国家改革・強化の必要性との間を行き来する必要性から、20世紀を通じて、より権威主義的な近代化の試みが繰り返された。こうした試みは、レザー・シャー・パーレビーの治世に頂点に達し、彼はイランを近代的な国民国家に変貌させることを目的として、しばしば権威主義的な手段で近代化と中央集権化の野心的なプログラムに取り組んだ。

1921年のクーデターとレザー・ハーンの台頭

レザー・ハーン(後のレザー・シャー・パーレビー)率いる1921年のクーデターは、イランの近代史における決定的な転換点となった。軍人であったレザー・ハーンは、政治的弱体化と不安定化の中で、中央集権化とイランの近代化という野望を抱いて政権を掌握した。クーデター後、レザー・ハーンは国家の強化と権力の強化を目的とした一連の改革を行った。中央集権政府を樹立し、行政を再編成し、軍隊を近代化した。これらの改革は、国の発展と近代化を推進できる強力で効果的な国家機構を確立するために不可欠であった。レザー・ハーンの権力強化の重要な側面は、外国勢力、特にイランに大きな経済的・戦略的利益をもたらしていたイギリスとの協定交渉であった。特に石油の問題は極めて重要であった。イランにはかなりの石油の潜在力があり、この資源の支配と開発は地政学的な利害の中心にあったからである。

レザー・ハーンは、外国勢力との協力とイランの主権を守ることのバランスを取りながら、この複雑な海域をうまく航海した。特に石油開発に関しては譲歩せざるを得なかったが、彼の政府はイランが石油収入のより公平な分配を受けられるようにし、内政における外国の直接的な影響を制限するよう努めた。1925年、レザ・ハーンはレザ・シャー・パーラヴィーに即位し、パーラヴィー朝の初代国王となった。彼の治世下、イランは経済の近代化、教育改革、社会的・文化的規範の西洋化、工業化政策など、急激な変革を遂げた。これらの改革は、しばしば権威主義的な方法で行われたものの、イランが近代的な時代に入ったことを示し、その後の発展の基礎を築いた。

=== レザー・シャー・パーレビーの時代:近代化と中央集権化 === 1925年、イランにレザー・シャー・パーレビーが登場すると、イランの政治と社会は激変した。カジャール朝の崩壊後、レザー・シャーはトルコのムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの改革に触発され、イランの近代化と強力な中央集権国家への発展を目指した一連の大改革に着手した。彼の治世は権威主義的な近代化を特徴とし、権力は高度に集中し、改革はトップダウンで行われた。権力の中央集権化は極めて重要なステップであり、レザー・シャーは部族長や地方の名士といった伝統的な中間勢力を排除しようとした。この権力の強化は、中央政府を強化し、国全体に対する統制を強化することを目的としていた。近代化の一環として、彼はメートル法を導入し、新しい道路や鉄道を建設して交通網を近代化し、イランを西洋の標準に合わせるために文化や服装の改革も行った。

レザー・シャーはまた、強力なナショナリズムを推進し、ペルシャ帝国の過去とペルシャ語を称揚した。このようなイランの過去の称揚は、イランの多様な人々の間に国民の一体感と共通のアイデンティティを生み出すことを意図していた。しかし、こうした改革は個人の自由という点では大きな代償を払った。レザー・シャー政権の特徴は、検閲、表現の自由と政治的反対意見の抑圧、政治機構の厳格な統制にあった。立法面では、近代的な民法や刑法が導入され、国民の外見を近代化するために服装改革が行われた。これらの改革はイランの近代化に貢献したが、民主的な参加はなく、権威主義的なやり方で実施されたため、将来の緊張の種をまいた。したがって、レザー・シャー時代はイランにおける矛盾の時代であった。一方では、国の近代化と中央集権化において大きな飛躍を意味した。他方では、権威主義的なアプローチと自由な政治的表現手段の不在により、将来の紛争の基礎を築いた。そのため、この時期はイランの近代史において決定的であり、今後数十年にわたる政治、社会、経済の軌跡を形作るものであった。

名称の変更:ペルシャからイランへの改名

1934年12月のペルシャからイランへの改名は、国際政治とイデオロギーの影響がいかに国のアイデンティティを形成するかを示す興味深い例である。レザー・シャー・パーレビの治世下、それまで歴史的かつ西欧的な国名であったペルシャは、国内で長く使われてきた「アーリア人の国」を意味するイランと正式に呼ばれるようになった。この国名変更は、ヨーロッパにおける民族主義的・人種的イデオロギーの台頭を背景に、西側諸国との結びつきを強め、アーリア人の伝統を強調するための努力でもあった。当時、ナチスのプロパガンダは、イランを含む中東のいくつかの国でも反響を呼んでいた。イランにおける英ソの影響力に対抗しようとしていたレザー・シャーは、ナチス・ドイツを潜在的な戦略的同盟国と見なしていた。しかし、彼のドイツとの融和政策は、連合国、特にイギリスとソ連の懸念を呼び起こし、彼らは第二次世界大戦中にイランがナチス・ドイツと協力することを恐れた。

こうした懸念と、ソ連軍への物資輸送ルートとしてのイランの戦略的役割の結果、イランは戦争の焦点となった。1941年、イギリス軍とソ連軍がイランに侵攻し、レザー・シャーは息子のモハメド・レザー・パフラヴィーに退位させられた。モハメッド・レザはまだ若く、経験も浅かったが、国際的な緊張と外国軍の駐留を背景に即位した。連合軍のイラン侵攻と占領はイランに大きな影響を与え、レザー・シャーの中立政策の終焉を早め、イランの歴史に新しい時代をもたらした。モハメッド・レザー・シャーのもと、イランは冷戦期には西側諸国の重要な同盟国となるが、その一方で、1979年のイラン革命で頂点に達することになる内政上の課題や政治的緊張が生じることになる。

石油国有化とモサデグ政権崩壊

イランにおける石油国有化と1953年のモハンマド・モサデグ政権崩壊のエピソードは、中東史の重要な一章を構成し、冷戦期の勢力図と地政学的利害を明らかにするものである。1951年、首相に選出された民族主義政治家モサデグは、当時イギリスのアングロ・イラニアン・オイル・カンパニー(AIOC、現BP)が支配していたイランの石油産業の国有化という大胆な行動に出た。モサデグは、イランの経済的・政治的独立のためには、国の天然資源、とりわけ石油の管理が不可欠だと考えた。石油国有化の決定はイラン国内で大きな反響を呼んだが、同時に国際的な危機を引き起こした。イランの石油資源への特権的なアクセスを失った英国は、石油禁輸を含む外交的・経済的手段でこの動きを阻止しようとした。イランとの行き詰まりに直面し、従来の手段では事態を解決できなかった英国政府は、米国に助けを求めた。当初は難色を示していた米国も、冷戦の緊張が高まり、イランにおける共産主義者の影響力を恐れていたこともあり、最終的には説得に応じた。

1953年、CIAはイギリスのMI6の支援を得て、モサデグを罷免し、国王モハンマド・レザ・パフラヴィーの権力を強化するクーデター「エイジャックス作戦」を開始した。このクーデターはイランの歴史に決定的な転換点をもたらし、王政を強化し、イランにおける欧米、特にアメリカの影響力を増大させた。しかし、外国からの介入と民族主義的・民主主義的願望の抑圧は、イランに深い憤りを生み、それがイラン国内の政治的緊張を高め、最終的には1979年のイラン革命につながった。エイジャックス作戦は、イランだけでなく中東地域全体にとって、冷戦時代の介入主義とその長期的帰結の典型例としてしばしば引き合いに出される。

モハンマド・モサデグ首相の罷免に象徴される1953年のイランの出来事は、イランの政治発展に多大な影響を与えた極めて重要な時期であった。モサデグは民主的に選出され、その民族主義的政策、とりわけイラン石油産業の国有化で非常に人気があったが、アメリカのCIAとイギリスのMI6が「エイジャックス作戦」として画策したクーデターによって倒された。

モハンマド・レザ・パフラヴィー国王の「白色革命

モサデグの退陣後、国王モハンマド・レザ・パフラヴィーは権力を強化し、権威主義を強めていった。米国をはじめとする西側諸国の支援を受けた国王は、イランの近代化と発展のための野心的なプログラムを開始した。白色革命」として知られるこのプログラムは1963年に開始され、イランを近代的な工業国へと急速に変貌させることを目指した。国王の改革には、土地の再分配、大規模な識字率向上キャンペーン、経済の近代化、工業化、女性への選挙権付与などが含まれた。これらの改革は、イラン経済を強化し、石油への依存を減らし、イラン国民の生活環境を改善するはずだった。しかし、国王の治世は厳しい政治統制と反対意見の弾圧によって特徴づけられるものでもあった。米国とイスラエルの協力を得て創設された国王の秘密警察SAVAKは、その残忍さと抑圧的な戦術で悪名高かった。政治的自由の欠如、汚職、社会的不平等の拡大により、イラン国民の間に不満が広がった。国王は近代化と開発という点では一定の成果を収めたが、民主的な政治改革の欠如と反対派の声の抑圧は、結局のところ、イラン社会の大部分を疎外する一因となった。このような状況が、王政を打倒しイラン・イスラム共和国を樹立した1979年のイラン革命への道を開いた。

西側諸国との関係強化と社会的影響

1955年以来、イランはモハンマド・レザ・パフラヴィー国王の指導の下、冷戦の中で西側諸国、特に米国との関係強化を図ってきた。1955年のバグダッド協定への加盟は、こうした戦略的志向の重要な要素であった。イラク、トルコ、パキスタン、イギリスも参加したこの協定は、中東におけるソビエト共産主義の拡大を封じ込めることを目的とした軍事同盟であった。西側諸国との和解の一環として、国王はイランの近代化を目指した一連の改革「白の革命」を開始した。これらの改革は、主にアメリカのモデルの影響を受けており、生産と消費のパターンの変更、土地改革、識字率向上キャンペーン、工業化と経済発展を促進する取り組みなどが含まれた。イランの近代化プロセスへの米国の密接な関与は、イラン国内に米国の専門家やアドバイザーが存在することでも象徴された。こうした専門家たちはしばしば特権や免除を享受し、イラン社会のさまざまな部門、特に宗教界や民族主義者の間に緊張をもたらした。

国王の改革は、経済的・社会的な近代化をもたらす一方で、多くの人々には、アメリカ化の一形態であり、イランの価値観や伝統を侵食するものだと受け止められていた。このような認識は、シャー政権の権威主義的性格と政治的自由や民衆参加の不在によって悪化した。イランにおけるアメリカのプレゼンスと影響力、そして「白色革命」の改革は、特に宗教界で高まる憤りを煽った。アヤトラ・ホメイニに率いられた宗教指導者たちは、国王が米国に依存し、イスラムの価値観から逸脱していることを批判し、国王への反発を強めていった。この反対運動は、やがて1979年のイラン革命へとつながる動員において重要な役割を果たした。

1960年代に国王モハンマド・レザ・パフラヴィーによって開始されたイランの「白の革命」改革には、国の社会・経済構造に大きな影響を与えた大規模な土地改革が含まれていた。この改革の目的は、イランの農業を近代化し、石油輸出への依存を減らすと同時に、農民の生活条件を改善することだった。土地改革は、伝統的な慣習、特に導師による供え物などイスラム教に関連する慣習を打ち破った。その代わりに、生産性の向上と経済発展の促進を目的とした市場経済的なアプローチが支持された。土地の再分配が行われ、広大な農地を支配していた大地主や宗教エリートの力が削がれた。しかし、この改革は、他の近代化構想とともに、住民の協議や参加に意味を見出すことなく、権威主義的かつトップダウン的に実施された。左翼や共産主義グループを含む反対派への弾圧もシャー政権の特徴であった。国王の秘密警察であるSAVAKは、その残忍な手法と広範な監視で悪名高かった。

国王の権威主義的アプローチは、改革の経済的・社会的影響と相まって、イラン社会のさまざまな層の不満を増大させた。シーア派の聖職者、民族主義者、共産主義者、知識人、その他のグループは、体制に反対することで共通点を見出した。やがて、この異質な反対運動は、ますます協調的な運動へと統合されていった。1979年のイラン革命は、このような反対運動の収束の結果として見ることができる。国王による抑圧、外国からの影響、破壊的な経済改革、伝統的・宗教的価値観の疎外などが、民衆の反乱のための肥沃な土壌を作り出した。この革命は最終的に王政を打倒し、イラン・イスラム共和国を樹立し、イランの歴史に急進的な転換点をもたらした。

1971年、モハンマド・レザー・パフラヴィー国王が主催したペルシャ帝国建国2500周年記念式典は、イランの偉大さと歴史の連続性を強調するために企画された記念碑的なイベントだった。アケメネス帝国の古都ペルセポリスで開催されたこの豪華な祝典は、国王の政権とペルシャの輝かしい帝国の歴史とのつながりを確立することを目的としていた。イランの国民的アイデンティティを強化し、その歴史的ルーツを強調する努力の一環として、モハンマド・レザー・シャーはイランの暦に大きな変更を加えた。この変更により、ヘギラ(預言者モハメッドがメッカからメディナへ移動した日)に基づくイスラム暦が、紀元前559年にキュロス大王がアケメネス朝帝国を建国したことに始まる帝国暦に置き換えられた。

しかし、この暦の変更は物議を醸し、国王がイランの歴史と文化におけるイスラム教の重要性を軽視し、イスラム教以前の帝国時代の過去を美化しようとしていると多くの人々に見なされた。これは国王の近代化・世俗化政策の一環であったが、宗教団体やイスラムの伝統に固執する人々の不満を煽ることにもなった。数年後、1979年のイラン革命により、イランはイスラム暦の使用に戻った。ホメイニ師が率いるこの革命は、パフラヴィー王政を打倒し、イラン・イスラム共和国を樹立したもので、イランのイスラム以前の歴史に基づくナショナリズムを推進しようとしたことも含め、国王の政策や統治スタイルを深く否定するものだった。暦の問題とペルシア帝国建国2500年の祝典は、歴史と文化がいかに政治に動員されうるか、またそのような行動がいかに国の社会的・政治的力学に大きな影響を与えうるかを示す例である。

1979年のイラン革命とその影響

1979年のイラン革命は、イランだけでなく世界の地政学にとっても、現代史における画期的な出来事であった。この革命により、国王モハンマド・レザー・パフラヴィーによる王政が崩壊し、ルーホッラー・ホメイニ師率いるイスラム共和国が樹立された。革命までの数年間、イランは大規模なデモと民衆不安に揺れた。これらの抗議運動は、国王の権威主義的な政策、汚職や欧米依存の認識、政治的抑圧、急速な近代化政策によって悪化した社会的・経済的不平等など、国王に対する多くの不満が動機となっていた。加えて、国王が病気であったこと、政治的・社会的改革要求の高まりに効果的に対応できなかったことも、全般的な不満と幻滅を助長した。

1979年1月、動揺の激化に直面した国王はイランを去り、亡命した。その直後、革命の精神的・政治的指導者であったホメイニ師が15年間の亡命生活を終えて帰国した。ホメイニはカリスマ的な尊敬を集める人物であり、パフラヴィー王政に反対し、イスラム国家を呼びかけたことで、イラン社会のさまざまな層から広範な支持を得ていた。ホメイニがイランに到着すると、何百万人もの支持者が彼を出迎えた。その直後、イラン軍は中立を宣言し、国王の体制が回復不能なまでに弱体化したことを明確に示した。ホメイニはすぐに政権を掌握し、王政の終結を宣言して臨時政府を樹立した。

イラン革命は、シーア派イスラム教の原則に基づき、宗教聖職者が指導する神権国家、イラン・イスラム共和国の誕生につながった。ホメイニはイランの最高指導者となり、国家の政治的・宗教的側面に対して大きな権力を持つようになった。革命はイランを変貌させただけでなく、特にイランと米国の緊張を激化させ、イスラム世界の他の地域のイスラム主義運動に影響を与えるなど、地域政治や国際政治にも大きな影響を与えた。

1979年のイラン革命は世界的な注目を集め、解放運動あるいは精神的・政治的復興と見なした欧米の知識人を含むさまざまなグループによって支持された。その中でも、フランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーは、革命に関する著作や解説で特に注目された。権力構造と統治に関する批判的分析で知られるフーコーは、イラン革命を現代の政治的・社会的規範に挑戦する重要な出来事として関心を寄せていた。彼は革命の民衆的、精神的側面に魅了され、革命を伝統的な西洋の左派、右派のカテゴリーを超えた政治的抵抗の一形態とみなした。しかし、革命後に誕生したイスラム共和国の性格から、彼の立場は論争と議論の種となった。

イラン革命はシーア派神権政治の確立につながり、シーア派法(シャリーア)に基づくイスラム統治の原則が国家の政治的・法的構造に組み込まれた。ホメイニ師の指導の下、新体制は「ヴェラヤト・エ・ファキーフ(イスラム法学者の指導)」として知られる独自の政治構造を確立し、そこでは最高指導者という宗教的権威が大きな権力を握っている。イランの神権政治への移行は、イラン社会のあらゆる側面に重大な変化をもたらした。革命は当初、聖職者だけでなく、民族主義者、左派、リベラル派などさまざまなグループの支持を得たが、その後の数年間は、シーア派の聖職者の手に権力が集約され、他の政治グループに対する抑圧が強まった。神権政治と民主主義が混在するイスラム共和国のあり方は、イラン内外で議論と分析の対象となり続けた。革命はイランを大きく変貌させ、地域政治と世界政治に永続的な影響を与え、宗教、政治、権力の関係を再定義した。

イラン・イラク戦争とイスラム共和国への影響

1980年、サダム・フセイン政権下のイラクによるイラン侵攻は、イラン・イスラム共和国の強化に逆説的な役割を果たした。イラン・イラク戦争として知られるこの紛争は、1980年9月から1988年8月まで続き、20世紀で最も長く、最も血なまぐさい紛争のひとつとなった。イラク攻撃当時、イラン・イスラム共和国は、パーレビ王政を打倒した1979年の革命後、まだ黎明期にあった。ホメイニ師率いるイラン政権は権力を固めつつあったが、内部では大きな緊張と困難に直面していた。イラク侵攻はイランに統一効果をもたらし、国民感情とイスラム体制への支持を強めた。外的脅威に直面したイラン国民は、それまで政府と対立していた多くのグループを含め、国防のために結集した。戦争はまた、ホメイニ政権がイスラム共和国とシーア派イスラムを守るという旗印のもとに国民を動員し、国への支配力を強めることを可能にした。イラン・イラク戦争はまた、イランにおける宗教的権力の重要性を強化した。イラン・イラク戦争はまた、イランにおける宗教的権力の重要性を強化した。政権は宗教的レトリックを用いて国民を動員し、自らの行動を正当化した。「イスラムの擁護」という概念に依拠して、政治的、社会的説得力の異なるイラン国民を団結させたのである。

イラン・イスラム共和国は正式に宣言されたわけではなく、1979年のイスラム革命によって誕生した。革命後に採択されたイランの新憲法は、シーア派イスラムの原則と価値観を政治体制の中心に据えた独自の神権政治体制を確立した。世俗主義はイラン憲法の特徴ではなく、「ヴェラヤト・エ・ファキーフ」(イスラム法学者の後見)の教義の下、宗教的統治と政治的統治が融合している。

エジプト

古代エジプトとその継承

豊かで複雑な歴史を持つエジプトは、古代文明の発祥地であり、何世紀にもわたって歴代の支配者が誕生してきた。現在のエジプトは、古代ファラオ時代のエジプトをルーツとする、歴史上最も古く偉大な文明の中心地であった。長い間、エジプトは様々な帝国や大国の影響下にあった。ファラオ時代の後、ペルシャ、ギリシャ(アレクサンダー大王の征服後)、ローマの支配下に相次いで置かれた。それぞれの時代がエジプトの歴史と文化に永続的な足跡を残した。639年に始まったアラブによるエジプト征服は、エジプトの歴史の転換点となった。アラブの侵攻はエジプトのイスラム化とアラブ化をもたらし、エジプトの社会と文化を大きく変貌させた。エジプトはイスラム世界の不可欠な一部となり、その地位は今日まで維持されている。

1517年、カイロを占領したエジプトはオスマン帝国の支配下に入った。オスマン帝国の支配下、エジプトはある程度の地方自治を維持したが、オスマン帝国の政治的・経済的な運命にも縛られた。この時代は19世紀初頭まで続き、近代エジプトの創始者とされるムハンマド・アリ・パシャなどの指導者のもと、エジプトは近代化と独立の道を歩み始めた。エジプトの歴史は、文明、文化、影響の交差点であり、それがこの国を豊かで多様なアイデンティティを持つユニークな国へと形成してきた。その歴史の各時代が、アラブ世界と国際政治において重要な役割を果たす国家、現代エジプトの建設に貢献してきた。

18世紀、エジプトは地理的に重要な位置にあり、インドへのルートを支配していたため、ヨーロッパ列強、特にイギリスにとって戦略的な関心を集める領土となった。海洋貿易の重要性が高まり、安全な通商路の必要性が高まるにつれ、イギリスのエジプトに対する関心は高まった。

メフメト・アリと近代化改革

ナハダ(アラブ・ルネサンス)は、19世紀のエジプト、特に近代エジプトの創始者とされるメフメト・アリの治世に根付いた、文化的、知的、政治的な一大運動である。アルバニア出身のメフメト・アリは、1805年にオスマン帝国からエジプト総督に任命され、すぐに国の近代化に着手した。彼の改革には、軍隊の近代化、新しい農法の導入、工業の拡大、近代的な教育制度の確立などが含まれる。エジプトにおけるナハダは、アラブ世界におけるより広範な文化的・知的運動と重なり、文学、科学、知的復興が特徴的であった。エジプトでは、この動きはメフメト・アリの改革とヨーロッパの影響への開放によって刺激された。

メフメト・アリの息子イブラヒム・パシャもまた、エジプトの歴史において重要な役割を果たした。彼の指揮の下、エジプト軍はいくつかの軍事作戦を成功させ、エジプトの影響力を従来の国境をはるかに超えて拡大しました。1830年代には、エジプト軍はオスマン帝国に挑み、ヨーロッパの大国を巻き込んだ国際危機にまで発展した。メフメト・アリとイブラヒム・パシャの拡張主義は、オスマン帝国の権威に対する直接的な挑戦であり、エジプトをこの地域における重要な政治的・軍事的プレーヤーとして際立たせた。しかし、ヨーロッパ列強、特にイギリスとフランスの介入は、最終的にエジプトの野心を制限し、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけてこれらの列強がこの地域で果たす役割が大きくなることを予見させた。

1869年のスエズ運河の開通は、エジプトの歴史において決定的な出来事となり、国際舞台におけるエジプトの戦略的重要性が著しく高まった。地中海と紅海を結ぶこの運河は、ヨーロッパとアジアの距離を大幅に縮め、海上貿易に革命をもたらした。こうしてエジプトは世界の貿易ルートの中心に位置することになり、帝国主義大国、特にイギリスの注目を集めることになった。しかし同時に、エジプトは経済的な困難に直面した。スエズ運河をはじめとする近代化プロジェクトの建設費用により、エジプト政府はフランスやイギリスを中心とするヨーロッパ諸国に多額の借金を背負わされた。これらの借金を返済できなかったエジプトは、政治的にも経済的にも大きな影響を受けた。

英国保護領と独立闘争

1876年、債務危機の結果、エジプトの財政を監督するために英仏の管理委員会が設置された。この委員会は国の運営に大きな役割を果たし、エジプトの自治権と主権を事実上縮小させた。このような外国からの干渉は、エジプト国民、特に改革と債務返済の経済的影響に苦しむ労働者階級の不満を増大させた。1880年代、状況はさらに悪化した。1882年、アハメド・ウラビによる民族主義者の反乱など、数年にわたる緊張の高まりと内乱の後、イギリスが軍事介入し、エジプトに対する事実上の保護領を確立した。エジプトは公式には第一次世界大戦が終わるまでオスマン帝国の一部であったが、実際はイギリスの支配下にあった。イギリスのエジプト駐留は、イギリスの利益、特に大英帝国の「王冠の宝石」であるインドへの海路にとって重要なスエズ運河を守る必要性によって正当化された。このイギリス統治時代はエジプトに大きな影響を与え、政治、経済、社会の発展を形成し、やがて1952年の革命と国の正式な独立につながるエジプト・ナショナリズムの種をまいた。

第一次世界大戦は、交戦国、特にイギリスにとってスエズ運河の戦略的重要性を際立たせた。スエズ運河は、アジアの植民地、特に当時大英帝国の重要な一部であったインドへの最速の海路を提供するものであり、イギリスの利益にとって不可欠なものであった。1914年に第一次世界大戦が勃発すると、中央列強(特にドイツと同盟を結ぶオスマン帝国)からの攻撃や干渉の可能性からスエズ運河を守ることが、イギリスにとって最優先事項となった。こうした戦略的懸念を受けて、イギリスはエジプトへの支配を強化することを決定した。1914年、イギリスは正式にエジプト保護領を宣言し、名目上オスマン帝国の宗主権をイギリスの直接支配に置き換えた。この宣言は、1517年から続いたオスマン帝国による名目上のエジプト支配の終焉を意味し、同国にイギリスの植民地行政を確立した。

イギリスの保護領はエジプトの内政に直接干渉し、同国に対するイギリスの軍事的・政治的支配を強化した。イギリスはこの措置をエジプトとスエズ運河の防衛のために必要であると正当化したが、エジプト国民には主権侵害として広く受け止められ、エジプトの民族主義感情を煽った。第一次世界大戦はエジプトの経済的、社会的苦難の時代であり、イギリスの戦争努力の要求と植民地政府による制限によって悪化した。このような状況は、より強力なエジプト民族主義運動の勃興につながり、やがて戦争後の数年間、反乱と独立闘争につながった。

ナショナリスト運動と独立の探求

第一次世界大戦後のエジプトは、緊張と民族主義的要求が高まる時期だった。イギリスの資源徴発による苛酷な労働や飢餓など、戦争の苦しみを味わったエジプト人は、独立と自分たちの戦争努力に対する承認を求め始めた。

第一次世界大戦の終結は、国際統治の新たな原則と民族の自決権を求めたウッドロー・ウィルソン米大統領の「十四箇条の御誓文」のおかげもあって、自決と植民地帝国の終焉という考え方が広まりつつある世界的な情勢を作り出していた。エジプトでは、このような情勢を受けて、ワフド(アラビア語で「代表団」の意)に代表される民族主義運動が形成された。ワフドはサード・ザグルール(Saad Zaghloul)に率いられ、彼はエジプトの民族主義的願望の代弁者となった。1919年、ザグルールをはじめとするワフドのメンバーは、エジプトの独立を訴えるためにパリ講和会議に参加しようとした。しかし、エジプト代表団のパリ行きはイギリス当局に妨害された。ザグルとその仲間はイギリスによって逮捕され、マルタ島に追放された。このことが、1919年革命として知られるエジプトの大規模なデモと暴動の引き金となった。この革命は、あらゆる階層のエジプト人が大規模に参加した大規模な民衆蜂起であり、エジプト独立闘争の決定的な転換点となった。

ザグルールの強制亡命とイギリスの抑圧的な対応は、エジプトの民族主義運動を活気づけ、イギリスに対してエジプトの独立を承認するよう圧力を強めた。最終的に、この危機は1922年にエジプトの独立を部分的に承認し、1936年にイギリスの保護領を正式に終了させることにつながったが、1952年の革命まで、エジプトにおけるイギリスの影響力は依然として大きかった。ワフドはエジプトの主要な政治的プレーヤーとなり、その後の数十年間、エジプト政治において重要な役割を果たし、サード・ザグルはエジプト・ナショナリズムの象徴的人物であり続けた。

1919年の革命とサード・ザグルール率いるワフドの指導力によって強化されたエジプトの革命的民族主義運動は、イギリスに対してエジプトでの立場を再考するよう圧力を強めていった。この圧力と第一次世界大戦後の政治的現実の変化に対応するため、イギリスは1922年にエジプトに対する保護領の終了を宣言した。しかし、この「独立」は非常に条件付きで限定的なものだった。実際、独立宣言はエジプトの主権への一歩を示すものではあったが、エジプトにおけるイギリスの影響力を維持するためのいくつかの重要な留保が含まれていた。その中には、イギリスの戦略的・商業的利益にとって極めて重要なスエズ運河周辺のイギリス軍の駐留を維持することや、ナイル川の重要な水源であり地政学的に大きな問題であったスーダンの支配などが含まれていた。

このような背景の中、1917年からエジプトのスルタンであったスルタン・フアドは、保護領の終了を機に1922年にフアド1世を宣言し、独立したエジプト王政を確立した。しかし、彼の治世はイギリスとの密接な関係によって特徴づけられた。フアド1世は、形式的には独立を認めながらも、しばしばイギリス当局と密接に協力して行動したため、イギリスの利益に従属する君主としてエジプトのナショナリストたちから批判を浴びた。そのため、1922年の独立宣言後のエジプトは、国の方向性やイギリスからの真の独立の程度をめぐる内政闘争が繰り広げられ、過渡期と緊張の時代となった。この状況は、王政を打倒しエジプト・アラブ共和国を樹立した1952年の革命を含め、エジプトにおける将来の政治的対立の基礎を築いた。

年にハッサン・アル=バンナがエジプトでムスリム同胞団を創設したことは、エジプトの社会的・政治的歴史における重要な出来事である。この運動は、エジプトにおける急速な近代化と西洋の影響力に対する不満の高まり、またイスラムの価値観や伝統の劣化が認識されるようになったことを背景に創設された。ムスリム同胞団は自らをイスラム主義運動と位置づけ、生活のあらゆる側面においてイスラム原理への回帰を促進することを目指した。彼らは、過度な西洋化やイスラム文化的アイデンティティの喪失として認識されていることに反対し、イスラム法と原則に支配された社会を提唱した。この運動は急速に人気を博し、エジプトの社会的・政治的勢力として影響力を持つようになった。ムスリム同胞団のような運動の出現と並行して、エジプトは1920年代から1930年代にかけて政治的に不安定な時期を経験した。この不安定さは、ヨーロッパにおけるファシスト勢力の台頭と相まって、イギリスにとって憂慮すべき国際情勢を生み出した。

こうした背景から、イギリスはエジプトの独立について譲歩する必要性を認識しながらも、エジプトにおける影響力を強化しようとした。1936年、イギリスとエジプトは英エジプト条約に調印し、エジプトの独立を正式に強化する一方で、特にスエズ運河周辺でのイギリス軍の駐留を認めた。この条約はまた、当時アングロ・エジプシャンの支配下にあったスーダンの防衛におけるエジプトの役割も認めた。1936年条約はエジプトの独立拡大への一歩であったが、同時にイギリスの影響力の重要な側面も維持した。条約の締結は、エジプト情勢を安定させ、第二次世界大戦中にエジプトが枢軸国の影響下に陥らないようにするためのイギリスの試みであった。この条約はまた、エジプトとこの地域の政治的現実の変化に適応する必要性を英国が認識していたことを反映していた。

ナセル時代と1952年革命

1952年7月23日、自由将校団として知られるエジプト軍将校グループによるクーデターがエジプトの歴史に大きな転機をもたらした。この革命はファルーク国王の王政を打倒し、共和制の樹立につながった。自由将校の指導者の中で、ガマル・アブデル・ナセルはすぐに支配的な人物となり、新体制の顔となった。1954年に大統領に就任したナセルは、汎アラブ主義と社会主義の思想の影響を受け、強力な民族主義と第三世界主義政策を採用した。彼の汎アラブ主義は、アラブ諸国を共通の価値観と政治的、経済的、文化的利益のもとに団結させることを目指した。このイデオロギーは、欧米の影響と介入に対する反応でもあった。1956年のスエズ運河の国有化は、ナセルの最も大胆で象徴的な決断のひとつであった。この行動は、エジプト経済にとって不可欠な資源を管理し、欧米の影響から自らを解放したいという欲求に突き動かされたものであったが、フランス、イギリス、イスラエルとの大規模な軍事衝突であるスエズ運河危機の引き金にもなった。

ナセルの社会主義は開発主義であり、社会正義を推進しながらエジプト経済の近代化と工業化を目指した。彼の指導の下、エジプトは大規模なインフラプロジェクトを開始し、中でも最も注目されたのがアスワン・ダムだった。この一大プロジェクトを完成させるため、ナセルはソ連に資金と技術支援を求め、冷戦時代のエジプトとソビエトの和解を印象づけた。ナセルはまた、土地改革や特定の産業の国有化などの社会主義政策を実施しながら、エジプトのブルジョワジーを育成しようとした。これらの政策は、不平等を是正し、より公正で独立した経済を確立することを目的としていた。ナセルの指導力はエジプトだけでなく、アラブ世界全体や第三世界にも大きな影響を与えた。彼はアラブ民族主義と非同盟運動の象徴的な人物となり、冷戦時代の勢力圏の外でエジプトの独立路線を確立しようとした。

サダトから現代エジプトへ

1967年の6日間戦争で、エジプトはヨルダン、シリアとともにイスラエルに敗れ、ナセルの汎アラブ主義は壊滅的な打撃を受けた。この敗戦は、アラブ諸国にとって大きな領土的損失となっただけでなく、アラブの統一と力という理念にも深刻な打撃を与えた。この失敗に深く傷ついたナセルは、1970年に死去するまで権力の座にとどまった。ナセルの後を継いだアンワル・サダトは、異なる方向性を打ち出した。彼は、エジプト経済を外国投資に開放し、経済成長を促すことを目的とした、インフィタと呼ばれる経済改革を開始した。サダトはまた、エジプトの汎アラブ主義へのコミットメントに疑問を呈し、イスラエルとの関係樹立を目指した。1978年のキャンプ・デービッド合意は、米国の協力を得て交渉され、エジプトとイスラエルの和平条約締結につながり、中東史の大きな転換点となった。

しかし、サダトのイスラエルとの和解はアラブ世界で大きな議論を呼び、エジプトはアラブ連盟から追放された。この決定は、汎アラブの原則に対する裏切りとして多くの人々に受け止められ、この地域における汎アラブ・イデオロギーの再評価につながった。サダトは1981年、彼の政策、特に外交政策に反対していたイスラム主義グループ、ムスリム同胞団のメンバーによって暗殺された。サダトの後を継いだのは副大統領のホスニ・ムバラクで、ムバラクは30年近く続く政権を樹立した。

ムバラクの時代、エジプトは比較的安定していたが、特にムスリム同胞団やその他の野党グループに対する政治的抑圧が強まった。しかし、2011年、「アラブの春」の最中、ムバラクは民衆蜂起によって倒され、汚職、失業、政治弾圧に対する広範な不満が示された。2012年にはムスリム同胞団のモハメド・モルシが大統領に選出されたが、任期は短かった。2013年、彼はアブデル・ファタハ・アル・シシ将軍率いる軍事クーデターによって打倒され、その後2014年に大統領に選出された。シシ政権は、ムスリム同胞団のメンバーを含む政治的反体制派への弾圧を強化し、経済の安定化と治安強化に努めてきた。したがって、エジプト史の最近の時期は、エジプトとアラブの政治の複雑でしばしば激動する力学を反映した、大きな政治的変化によって特徴付けられる。

=サウジアラビア

建国の同盟:イブン・サウドとイブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブ

サウジアラビアは、近代国民国家としては比較的若く、その形成と進化を形成してきた独特のイデオロギー的基盤によって特徴づけられる。サウジアラビアの歴史と社会を理解する上で重要な要素は、ワッハーブ派のイデオロギーである。

ワッハーブ派はスンニ派イスラム教の一形態で、厳格で清教徒的なイスラム解釈を特徴とする。現在のサウジアラビアのナジュド地方出身の18世紀の神学者であり宗教改革者であるムハンマド・イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブにその名が由来する。イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブは、イスラム教本来の原理への回帰を唱え、革新(ビッダ)や偶像崇拝とみなされる多くの慣習を否定した。サウジアラビアの形成におけるワッハーブ派の影響は、18世紀におけるムハンマド・イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブとサウジアラビア第一王朝の創始者ムハンマド・イブン・サウードとの同盟と切っても切れない関係にある。この同盟は、イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブの宗教的目的とイブン・サウードの政治的・領土的野心を結びつけ、最初のサウジアラビア国家のイデオロギー的・政治的基盤を作り上げた。

近代サウジアラビア国家の成立

20世紀、近代サウジアラビア王国の創始者アブデラズィーズ・イブン・サウードの治世下、この同盟は強化された。サウジアラビアは1932年に正式に建国され、さまざまな部族や地域が単一の国家権力の下に統合された。ワッハーブ派は国家の公式な宗教教義となり、サウジアラビアの統治、教育、法律、社会生活に浸透した。ワッハーブ主義はサウジアラビア内部の社会・政治構造に影響を与えただけでなく、対外関係、特に外交政策や世界各地のさまざまなイスラム運動への支援にも影響を及ぼしている。サウジアラビアの石油資源は、同王国が自国のイスラム教を国際的に広めることを可能にし、国境を越えてワッハーブ派を広める一助となった。

アル・サウード族の首長ムハンマド・イブン・サウードと宗教改革者ムハンマド・イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブとの間で結ばれた1744年の盟約は、サウジアラビアの歴史における建国の出来事である。この盟約は、イブン・サウードの政治的目的とイブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブの宗教的理想を結びつけ、後のサウジアラビア国家の基礎を築いた。イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブはイスラム教の純血主義的解釈を提唱し、預言者ムハンマドやコーランの教えから逸脱した革新や迷信と考えられる宗教的実践を一掃しようとした。ワッハーブ派として知られるようになった彼の運動は、イスラムの「より純粋な」形式への回帰を求めた。一方、イブン・サウードはイブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブの運動に、自らの政治権力を正統化し拡大する機会を見出した。イブン・サウードはイブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブの教えを擁護し推進することを誓い、イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブはイブン・サウードの政治的権威を支持した。その後数年間、アル・サウードはワッハーブ派の信者の支持を得て、影響力を拡大し、イスラム教の解釈を押し付けるために軍事作戦を展開した。これらの軍事行動は18世紀に最初のサウジアラビア国家を誕生させ、アラビア半島の大部分をカバーすることになった。

しかし、サウジアラビア国家の形成は直線的なプロセスではなかった。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、アル・サウード政体はオスマン帝国とその同盟国であるエジプトによって最初のサウジアラビア国家が破壊されるなど、いくつかの挫折を味わった。1932年に宣言された現代サウジアラビアという安定した永続的な王国の樹立に成功したのは、20世紀初頭のアブデラジズ・イブン・サウドになってからである。サウジアラビアの歴史は、アル・サウド家とワッハーブ運動との同盟と密接に結びついており、この同盟は王国の政治的・社会的構造だけでなく、宗教的・文化的アイデンティティをも形成した。

イブン・サウードのレコンキスタと王国の建国

1803年のサウジアラビア軍によるメッカ攻撃は、アラビア半島の歴史において重要な出来事であり、当時の宗教的・政治的緊張を反映している。ムハンマド・イブン・アブド・アル=ワッハーブが推し進め、サウード家が採用したスンニ派イスラムの厳格な解釈であるワッハーブ派は、特定の慣習、特にシーア派の慣習をイスラム教とは異質なもの、あるいは異端視していた。1803年、サウジアラビアのワッハーブ派はイスラム教の聖地のひとつであるメッカを支配下に置いたが、これは他のイスラム教徒、特にイスラム聖地の伝統的な管理者であったオスマン帝国を挑発する行為と見なされた。この占領は、サウジによる領土拡張とみなされただけでなく、イスラム教の特殊な解釈を押し付けようとする試みともみなされた。

このサウジの進攻に対し、オスマン帝国はこの地域への影響力を維持するため、オスマン帝国のエジプト総督であったメフメト・アリ・パシャの指揮下に軍隊を派遣した。メフメト・アリ・パシャは、その軍事力とエジプト近代化への努力で有名であり、サウジアラビア軍に対して効果的な作戦を指揮した。1818年、メフメト・アリ・パシャの軍隊は一連の軍事的対決の後、サウジアラビア軍を撃破し、その指導者アブドゥッラー・ビン・サウドを捕らえることに成功した。この敗北は、最初のサウジアラビア国家の終焉を意味した。このエピソードは、当時のこの地域の政治的・宗教的力学の複雑さを物語っている。イスラム教の異なる解釈の対立だけでなく、当時の地域勢力、特にオスマン帝国と新興サウジアラビアの権力と影響力をめぐる争いも浮き彫りにしている。

1820年から1840年にかけて行われたサウジアラビア建国の第二の試みもまた、困難に遭遇し、最終的には失敗に終わった。この時期は、オスマン帝国やその地方の同盟国など、さまざまな敵対勢力とサウードとの間で紛争や対立が繰り返された。これらの闘争の結果、サウド家は領土と影響力を失った。しかし、サウジ国家樹立の熱望が消えたわけではない。20世紀に入り、特に1900-1901年頃、アル・サウド家のメンバーが亡命先から帰還し、サウジの歴史における新たな局面が始まった。その中でも、しばしばイブン・サウドと呼ばれるアブデラジズ・イブン・サウドは、サウジアラビアの再生と影響力の拡大に重要な役割を果たした。カリスマ的で戦略的な指導者であったイブン・サウドは、アラビア半島の領土を再征服し、サウード家の旗の下に統一することを目指した。彼の作戦は1902年のリヤド占領から始まり、さらなる征服と王国の拡大の出発点となった。

その後数十年にわたり、イブン・サウードは一連の軍事キャンペーンと政治的作戦を指揮し、アラビア半島の大部分に対する支配権を徐々に拡大していった。このような努力は、同盟交渉、部族間の対立の管理、国家のイデオロギー的基盤としてのワッハーブ派の教えを統合する彼の能力によって促進された。イブン・サウドの成功は、1932年のサウジアラビア王国建国に結実し、さまざまな地域と部族を単一の国家権力の下に統合した。新王国はイブン・サウドが征服したさまざまな領土を統合し、ワッハーブ派を宗教的・思想的基盤とする永続的なサウジアラビア国家を確立した。サウジアラビアの誕生は中東の近代史における重要な節目であり、特に同王国における石油の発見と開発以降、同地域と国際政治の双方に多大な影響を及ぼした。

大英帝国との関係およびアラブ反乱

第一次世界大戦中の1915年、オスマン帝国の弱体化を目指したイギリスは、ハシェミット家の有力者であったメッカのシェリフ・フセインをはじめとするさまざまなアラブ指導者と接触した。同時にイギリスは、アブデラジズ・イブン・サウド率いるサウジアラビアとも、ハシェミット家との関係よりは直接的でないものの、関係を維持した。シェリフ・フセインは、アラブの独立を支援するというイギリスの約束に後押しされ、1916年にオスマン帝国に対するアラブの反乱を起こした。この反乱の動機は、アラブの独立とオスマン帝国支配への反対であった。しかし、イブン・サウード率いるサウジアラビアはこの反乱に積極的に参加しなかった。彼らはアラビア半島の支配を強化し、拡大するための独自のキャンペーンに従事していた。サウジアラビアとハシェミテはオスマン帝国に対する共通の利害を持っていたが、同時にこの地域の支配権をめぐるライバルでもあった。

戦後、(サイクス・ピコ協定で想定された)独立アラブ王国を創設するという英仏の約束が失敗に終わり、シェリフ・フセインは孤立することになった。1924年、フセインはカリフを宣言したが、これはサウジアラビアを含む多くのイスラム教徒にとって挑発的な行為であった。フセインのカリフ宣言は、サウジアラビアが影響力を拡大するために彼を攻撃する口実となった。サウジアラビア軍は1924年についにメッカを制圧し、この地域におけるハシミテの支配を終わらせ、イブン・サウドの権力を強化した。この征服はサウジアラビア王国形成の重要な段階であり、ハシミテ王朝のもとで統一アラブ王国を作ろうというシェリフ・フセインの野望の終焉を意味した。

サウジアラビアの台頭と石油の発見

1926年、アラビア半島の大部分を支配下に置いたアブデラジズ・イブン・サウードは、ヒジャーズ王を宣言した。ヒジャーズは聖地メッカとメディナがあることから宗教的に重要な地域であり、それまではハシミテ王朝の支配下にあった。イブン・サウードがヒジャーズを掌握したことは、サウジアラビアがこの地域で強力な政治主体として確立する重要な一歩となった。ロシア、フランス、イギリスなどの列強がイブン・サウドをヒジャーズ王として承認したことは、彼の支配が国際的に正当化された重要な瞬間であった。これらの承認は、国際関係における重要な変化と、この地域における新たなパワーバランスの受容を意味した。イブン・サウドのヒジャーズ占領は、アラビア半島における政治的指導者としての地位を強化しただけでなく、イスラム世界における彼の威信を高め、イスラムの聖地の守護者としての地位を確立した。それはまた、ヒジャーズにおけるハシミテ王朝の存在の終わりを意味し、ハシミテ王朝の残りのメンバーは中東の他の地域に逃れ、ヨルダンとイラクを中心とした新しい王国を築いた。イブン・サウードがヒジャーズの王として宣言されたことは、近代サウジアラビアの形成における重要な一里塚であり、第一次世界大戦後の中東の政治構造を形成する一助となった。

1932年、アブデラズィーズ・イブン・サウードは領土と政治的強化のプロセスを完了し、サウジアラビア王国の創設に至った。サウジアラビア王国は、ネジ(またはネジュド)とヘジャズという地域を単一の国家権力の下に統合し、近代サウジアラビア国家の誕生を告げた。この統一は、アラビア半島に安定した統一王国を築こうとしたイブン・サウドの努力の集大成であり、彼が長年にわたって成し遂げてきたさまざまな征服と同盟を統合したものであった。1938年にサウジアラビアで石油が発見されたことは、王国だけでなく世界経済にとっても大きな転機となった。アメリカのカリフォルニア・アラビアン・スタンダード・オイル・カンパニー(後のARAMCO)が商業量の石油を発見したのである。この発見により、サウジアラビアは砂漠と農耕が中心だった国から、世界有数の石油産出国へと変貌を遂げた。

第二次世界大戦は、サウジアラビアの石油の戦略的重要性を際立たせた。戦時中、サウジアラビアは公式には中立を保っていたが、戦費を賄うための石油需要の増大により、イギリスやアメリカをはじめとする連合国にとってサウジアラビアは重要な経済パートナーとなった。特にサウジアラビアと米国の関係は戦時中から戦後にかけて強化され、安全保障と石油を中心とした永続的な同盟関係の基礎を築いた。この時期、サウジアラビアは膨大な石油埋蔵量を背景に、世界情勢に大きな影響力を持ち始めた。サウジアラビアは世界経済と中東政治における重要なプレーヤーとなり、その地位は現在も続いている。石油の富によって、サウジアラビアは国家開発に多額の投資を行い、地域政治や国際政治において影響力のある役割を果たすことができた。

現代の挑戦:イスラム主義、石油、国際政治

1979年のイランにおけるイスラム革命は、サウジアラビアを含む中東の地政学的バランスに大きな影響を与えた。ホメイニー師が台頭し、イランにイスラム共和国が樹立されたことで、中東地域の多くの国、特にサウジアラビアでは、シーア派の革命イデオロギーが輸出され、スンニ派が多数を占める湾岸諸国の君主制が不安定化するのではないかと懸念された。サウジアラビアでは、こうした懸念が、米国をはじめとする西側諸国の同盟国としての王国の立場を強化した。冷戦と革命後の米国とイランの敵対関係の高まりの中で、サウジアラビアはこの地域におけるイランの影響力に対する重要な対抗軸とみなされていた。サウジアラビアで実践されているスンニ派イスラム教の厳格で保守的な解釈であるワッハーブ派は、王国のアイデンティティの中心となり、イランのシーア派の影響力に対抗するために利用された。

サウジアラビアはまた、特にアフガン戦争(1979年〜1989年)の間、反ソ連の取り組みにおいて重要な役割を果たした。王国はソ連の侵攻と戦うアフガニスタンのムジャヒディンを財政的にも思想的にも支援し、ソ連の無神論に対するイスラム抵抗の一環としてワッハーブ主義を推進した。1981年、地域協力を強化し、イランの影響力に対抗する戦略の一環として、サウジアラビアは湾岸協力会議(GCC)設立の中心人物となった。GCCはサウジアラビア、クウェート、アラブ首長国連邦、カタール、バーレーン、オマーンで構成される政治・経済同盟である。この組織は、防衛、経済、外交政策などさまざまな分野で湾岸君主国間の協力を促進することを目的としている。GCC内でのサウジアラビアの地位は、地域のリーダーとしての役割を反映し、強化してきた。サウジアラビアはGCCを自国の戦略的利益を促進し、安全保障や政治的課題、とりわけイランとの緊張関係やイスラム主義運動や地域紛争に関連する混乱に直面する地域の安定化を図るためのプラットフォームとして利用してきた。

1990年8月、サダム・フセイン率いるイラクによるクウェート侵攻は、湾岸地域における一連の重大な出来事を引き起こし、サウジアラビアと世界政治に大きな影響を与えた。この侵攻は1991年の湾岸戦争につながり、米国主導の国際連合がクウェート解放のために結成された。イラクの脅威に直面したサウジアラビアは、自国領土への侵攻を恐れ、米軍や他の連合軍の駐留を受け入れた。対イラク作戦を開始するため、サウジアラビアに一時的な軍事基地が設置された。この決定は、イスラム教の2つの聖地メッカとメディナがある国に非イスラム教徒の軍隊を駐留させるという歴史的なものであり、物議を醸した。

サウジアラビアにおける米軍のプレゼンスは、オサマ・ビンラディン率いるアルカイダを含む様々なイスラム主義グループから強く批判された。ビンラディン自身もサウジアラビア出身であり、サウジアラビアにおける米軍の駐留はイスラム教の聖地を冒涜するものだと解釈した。これはアルカイダの米国に対する主な不満のひとつであり、2001年9月11日の同時多発テロを含むテロ攻撃の正当化に使われた。湾岸戦争と米軍のサウジアラビア駐留に対するアルカイダの反応は、西欧の価値観と特定のイスラム過激派グループとの緊張の高まりを浮き彫りにした。また、サウジアラビアが米国との戦略的関係と自国民内の保守的なイスラム感情のバランスを取る上で直面した課題も浮き彫りになった。湾岸戦争後のサウジアラビアは、政治的、イデオロギー的な対立が顕著で、地域的、国際的な力学に影響を与え続けている。

1979年にメッカの大モスクで起きた事件は、サウジアラビアの現代史において画期的な出来事であり、宗教的・政治的アイデンティティの問題と結びついた内的緊張を物語っている。1979年11月20日、ジュヘイマン・アル・オタイビ率いるイスラム原理主義者グループが、イスラム教で最も神聖な場所のひとつであるメッカの大モスクを襲撃した。ジュハイマン・アル=オタイビとその支持者たちは主に保守的で宗教的な背景を持ち、サウジ王室の腐敗、贅沢、西洋の影響に対する開放性を批判した。彼らは、これらの要因が王国の建国の基礎となったワッハーブ派の原則と相反するものであると考えた。アル=オタイビは義弟のムハンマド・アブドゥッラー・アル=カフタニをイスラム教の救世主マハディと宣言した。

グランドモスクの包囲は2週間続き、その間、反乱軍は数千人の巡礼者を人質にとった。この事態はサウジ政府にとって、安全保障の面だけでなく、宗教的、政治的正当性の面でも大きな挑戦となった。サウジアラビアは、通常は暴力が禁じられた平和の聖域であるモスクへの軍事介入を許可するファトワー(宗教令)を求めなければならなかった。1979年12月4日に始まったモスク奪還のための最終攻撃は、フランスのアドバイザーの支援を受けたサウジアラビアの治安部隊によって指揮された。戦闘は激しく、数百人の反乱軍、治安部隊、人質の死者を出した。

この事件は、サウジアラビアとイスラム世界に広範囲に影響を及ぼした。サウジ社会の亀裂を明らかにし、宗教的過激主義の管理という点で王国が直面している課題を浮き彫りにした。この危機を受けて、サウジ政府は保守的な宗教政策を強化し、宗教機関への統制を強めた。この事件はまた、サウジアラビアにおける宗教、政治、権力の関係の複雑さを浮き彫りにした。

Countries created by decree

At the end of the First World War, the United States, under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, had a different vision from that of the European powers regarding the future of the territories conquered during the war. Wilson, with his Fourteen Points, advocated the right of peoples to self-determination and opposed the acquisition of territory by conquest, a position that contrasted with the traditional colonial objectives of the European powers, notably Great Britain and France. The United States was also in favour of an open and equitable system of trade, which meant that territories should not be exclusively under the control of a single power, in order to allow wider commercial access, thus benefiting American interests. In practice, however, British and French interests prevailed, the latter having made significant territorial gains following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the defeat of Germany.

To reconcile these different perspectives, a compromise was found through the League of Nations system of mandates. This system was supposed to be a form of international governance for the conquered territories, in preparation for their eventual independence. Setting up this system required a complex process of negotiations and treaties. The San Remo Conference in 1920 was a key moment in this process, during which the mandates for the territories of the former Ottoman Empire were awarded, mainly to Great Britain and France. Subsequently, the Cairo Conference in 1921 further defined the terms and limits of these mandates. The Treaties of Sèvres in 1920 and Lausanne in 1923 redrew the map of the Middle East and formalised the end of the Ottoman Empire. The Treaty of Sèvres, in particular, dismantled the Ottoman Empire and provided for the creation of a number of independent nation states. However, due to Turkish opposition and subsequent changes in the geopolitical situation, the Treaty of Sèvres was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne, which redefined the borders of modern Turkey and annulled some of the provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres. This lengthy negotiation process reflected the complexities and tensions of the post-war world order, with established powers seeking to maintain their influence while confronting new international ideals and the emergence of the United States as a global power.

After the First World War, the dismantling of the Ottoman and German empires led to the creation of the League of Nations system of mandates, an attempt to manage the territories of these former empires in a post-colonial context. This system, established by the post-war peace treaties, notably the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, was divided into three categories - A, B and C - reflecting the perceived degree of development and readiness for self-government of the territories concerned.

Type A mandates, allocated to the territories of the former Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, were considered to be the most advanced towards self-determination. These territories, considered relatively "civilised" by the standards of the time, included Syria and Lebanon, under the French mandate, as well as Palestine (including present-day Jordan) and Iraq, under the British mandate. The notion of "civilisation" employed at the time reflected the prejudices and paternalistic attitudes of the colonial powers, assuming that these regions were closer to self-governance than others. The treatment of Type A mandates reflected the geopolitical interests of the mandating powers, notably Britain and France, who sought to extend their influence in the region. Their actions were often motivated by strategic and economic considerations, such as control of trade routes and access to oil resources, rather than a commitment to the autonomy of local populations. This was illustrated by the Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which Britain expressed its support for the creation of a "Jewish national home" in Palestine, a decision that had lasting and divisive consequences for the region. Type B and C mandates, mainly in Africa and certain Pacific islands, were considered to require a higher level of supervision. These territories, often underdeveloped and with little infrastructure, were managed more directly by the mandating powers. The system of mandates, although presented as a form of benevolent trusteeship, was in reality very close to colonialism and was widely perceived as such by the indigenous populations.

In short, the League of Nations system of mandates, despite its stated intention to prepare territories for independence, often served to perpetuate the influence and control of the European powers in the regions concerned. It also laid the foundations for many future political and territorial conflicts, particularly in the Middle East, where the borders and policies established during this period continue to have a significant impact on regional and international dynamics.

This map shows the distribution of territories formerly controlled by the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East and North Africa after they were lost by the Empire, mainly as a result of the First World War. The different zones of influence and the territories controlled by the European powers are colour-coded. The territories are divided according to the power that controlled them or exercised influence over them. British-controlled territories are in purple, the French in yellow, the Italians in pink and the Spanish in blue. Independent territories are marked in pale yellow, the Ottoman Empire is in glass with its borders at their height highlighted, and areas of Russian and British influence are also shown.

The map also shows the dates of initial occupation or control of certain territories by colonial powers, indicating the period of imperialist expansion in North Africa and the Middle East. For example, Algeria has been marked as French territory since 1830, Tunisia since 1881 and Morocco is divided between French (since 1912) and Spanish (since 1912) control. Libya, meanwhile, was under Italian control from 1911 to 1932. Egypt has been marked as British-controlled since 1882, although it was technically a British protectorate. Anglo-Egyptian Sudan is also shown, reflecting joint Egyptian and British control since 1899. As far as the Middle East is concerned, the map clearly shows the League of Nations mandates, with Syria and Lebanon under French mandate and Iraq and Palestine (including present-day Transjordan) under British mandate. The Hijaz, the region around Mecca and Medina, is also shown, reflecting the control of the Saud family, while Yemen and Oman are marked as British protectorates. This map is a useful tool for understanding the geopolitical changes that took place after the decline of the Ottoman Empire and how the Middle East and North Africa were reshaped by European colonial interests. It also shows the complexity of power relations in the region, which continue to affect regional and international politics today.

In 1919, following the First World War, the division of the territories of the former Ottoman Empire between the European powers was a controversial and divisive process. The local populations of these regions, having nurtured aspirations to self-determination and independence, often greeted the establishment of European-controlled mandates with hostility. This hostility was part of a wider context of dissatisfaction with Western influence and intervention in the region. The Arab nationalist movement, which had gained momentum during the war, aspired to the creation of a unified Arab state or several independent Arab states. These aspirations had been encouraged by British promises of support for Arab independence in return for support against the Ottomans, notably through the Hussein-McMahon correspondence and the Arab Revolt led by Sherif Hussein of Mecca. However, the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, a secret arrangement between Britain and France, divided the region into zones of influence, betraying promises made to the Arabs.

Anti-Western feelings were particularly strong because of the perception that the European powers were not honouring their commitments to the Arab populations and were manipulating the region for their own imperialist interests. By contrast, the United States was often viewed less critically by local populations. American policy under President Woodrow Wilson was seen as more supportive of self-determination and less inclined towards traditional imperialism. Moreover, the United States did not have the same colonial history as the European powers in the region, which made it less likely to arouse the hostility of local populations. The immediate post-war period was therefore one of profound uncertainty and tension in the Middle East, as local populations struggled for independence and autonomy in the face of foreign powers seeking to shape the region according to their own strategic and economic interests. The repercussions of these events shaped the political and social history of the Middle East throughout the 20th century and continue to influence international relations in the region.

Syria

The Dawn of Arab Nationalism: The Role of Faisal

Faisal, son of Sherif Hussein bin Ali of Mecca, played a leading role in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War and in subsequent attempts to form an independent Arab kingdom. After the war, he went to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, armed with British promises of independence for the Arabs in return for their support during the conflict. However, once in Paris, Faisal soon discovered the complex political realities and intrigues of post-war diplomacy. French interests in the Middle East, particularly in Syria and Lebanon, were in direct contradiction with aspirations for Arab independence. The French were resolutely opposed to the creation of a unified Arab kingdom under Faisal, envisaging instead placing these territories under their control as part of the League of Nations system of mandates. Faced with this opposition, and conscious of the need to strengthen his political position, Faisal negotiated an agreement with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. This agreement aimed to establish a French protectorate over Syria, which was at odds with the aspirations of the Arab nationalists. Faisal kept the agreement secret from his supporters, who continued to fight for full independence.

Meanwhile, a Syrian state was being formed. Under Faisal's leadership, efforts were made to lay the foundations of a modern state, with reforms in education, the creation of a public administration, the establishment of an army and the development of policies to strengthen national identity and sovereignty. Despite these developments, the situation in Syria remained precarious. The secret agreement with Clemenceau and the lack of British support put Faisal in a difficult position. Eventually, France took direct control of Syria in 1920 after the Battle of Maysaloun, ending Faisal's hopes of establishing an independent Arab kingdom. Faisal was expelled from Syria by the French, but would later become King of Iraq, another newly formed state under the British Mandate.

Syria under the French Mandate: The Sykes-Picot Agreements

The Sykes-Picot Accords, concluded in 1916 between Great Britain and France, established a division of influence and control over the territories of the former Ottoman Empire after the First World War. Under the terms of these agreements, France was to gain control of what is now Syria and Lebanon, while Great Britain was to control Iraq and Palestine. In July 1920, France sought to consolidate its control over the territories promised to it by the Sykes-Picot agreements. The Battle of Maysaloun was fought between French forces and troops from the short-lived Syrian Arab Kingdom under the command of King Faisal. The ill-equipped and ill-prepared Faisal forces were greatly outnumbered by the better-equipped and better-trained French army. The defeat at the Battle of Maysaloun was a devastating blow to Arab aspirations for independence and ended Faisal's reign in Syria. Following this defeat, he was forced into exile. This event marked the establishment of the French Mandate over Syria, which was officially recognised by the League of Nations despite the aspirations of the Syrian people for self-determination. The establishment of mandates was supposed to prepare territories for eventual autonomy and independence, but in practice it often functioned as colonial conquest and administration. Local populations largely viewed the mandates as a continuation of European colonialism, and the period of the French mandate in Syria was marked by significant rebellion and resistance. This period shaped many of Syria's political, social and national dynamics, influencing the country's history and identity to this day.

Fragmentation and the French Administration in Syria

After establishing control over the Syrian territories following the Battle of Maysaloun, France, under the authority of the mandate conferred by the League of Nations, set about restructuring the region according to its own administrative and political designs. This restructuring often involved the division of territories along sectarian or ethnic lines, a common practice of colonial policy aimed at fragmenting and weakening local nationalist movements.