中東の帝国と国家

古代文明発祥の地であり、文化・商業交流の交差点である中東は、特に中世において世界史の中心的役割を果たしてきた。このダイナミックで多様な時代には、数多くの帝国や国家が興亡を繰り返し、それぞれがこの地域の政治的、文化的、社会的景観に消えない足跡を残した。文化的、科学的に頂点に達したイスラムのカリフの拡大から、ビザンチン帝国の長期にわたる影響力、十字軍の侵入やモンゴルの征服を経て、中世の中東は絶えず進化する権力のモザイクであった。この時代は、この地域のアイデンティティを形成しただけでなく、世界史の発展にも大きな影響を与え、東洋と西洋の架け橋となった。中世における中東の帝国や国家を研究することは、征服、回復力、革新、文化的相互作用の物語を明らかにし、人類史における重要な時代を知るための魅力的な窓を提供する。

=オスマン帝国

オスマン帝国の建国と拡大

13世紀末に建国されたオスマン帝国は、3つの大陸の歴史に大きな影響を与えた帝国権力の魅力的な例である:アジア、アフリカ、ヨーロッパ。その建国は一般に、アナトリア地方のトルコ人部族の指導者オスマン1世によるとされている。この帝国の成功は、広大な領土を急速に拡大し、効率的な行政を確立したことにある。14世紀半ばからオスマン帝国はヨーロッパに領土を拡大し始め、バルカン半島の一部を徐々に征服した。この拡大は、地中海と東ヨーロッパのパワーバランスに大きな転換点をもたらした。しかし、一般に信じられているのとは異なり、オスマン帝国はローマを滅ぼしたわけではない。実際、オスマン帝国はビザンチン帝国の首都コンスタンティノープルを包囲し、1453年に征服してその帝国に終止符を打った。この征服は、ヨーロッパにおける中世の終わりと近代の始まりを告げる歴史的大事件であった。

オスマン帝国は、その複雑な行政構造と宗教的寛容性で知られ、特に非ムスリム共同体にある程度の自治を認めたキビ制度が有名である。最盛期は15世紀から17世紀にかけてで、その間、貿易、文化、科学、芸術、建築に多大な影響を及ぼした。オスマン帝国は多くの革新をもたらし、東西間の重要な仲介者であった。しかし、18世紀以降、オスマン帝国はヨーロッパ列強の台頭と国内問題に直面し、衰退し始めた。この衰退は19世紀に加速し、最終的には第一次世界大戦後の帝国解体へと至った。オスマン帝国の遺産は、支配した地域に深く根を下ろし、今日に至るまでそれらの社会の文化的、政治的、社会的側面に影響を与えている。

オスマン帝国は、13世紀末にオスマン1世によって建国された傑出した政治的・軍事的存在であり、ユーラシア大陸の歴史に多大な影響を与えてきた。政治的分断とアナトリアの王朝間の対立を背景に誕生したこの帝国は、瞬く間にその影響力を拡大し、この地域の支配的な大国としての地位を確立した。14世紀半ばは、オスマン帝国にとって決定的な転換期となった。特に1354年のガリポリ征服がそうである。この勝利は単なる武力的な偉業にとどまらず、ヨーロッパにおけるオスマン帝国の最初の定住地となり、バルカン半島における一連の征服への道を開いた。こうした軍事的成功と巧みな外交が相まって、オスマン・トルコは戦略的領土の支配を強化し、ヨーロッパ情勢への干渉を可能にした。

1453年のコンスタンティノープル征服で有名なメフメト2世のような支配者のもと、オスマン帝国は東地中海の政治的景観を再構築しただけでなく、文化的・経済的に大きな変革期を迎えた。ビザンチン帝国に終止符を打ったコンスタンティノープルの占領は、中世の終わりと近代の始まりを告げる、世界史の極めて重要な瞬間だった。ビザンツ帝国は、その規律正しく革新的な軍隊のおかげで戦争技術に秀でていたが、中央集権的な行政システムのもとで多様な民族や宗教を統合するという、統治への実際的なアプローチによっても優れていた。この文化的多様性は、政治的安定と相まって、芸術、科学、商業の繁栄を促した。

オスマン帝国の紛争と軍事的課題

オスマン帝国はその歴史を通じて、壮大な征服と大きな挫折を繰り返し、その運命と支配した地域の運命を形作った。オスマン帝国の拡大には大きな勝利がつきものであったが、戦略的な失敗もあった。オスマン帝国のバルカン半島への侵攻は、ヨーロッパ進出の第一歩であった。この征服は領土を拡大しただけでなく、この地域の支配者としての立場を強化した。メフメト征服王として知られるメフメト2世が1453年にイスタンブールを占領したことは、歴史的に大きな出来事であった。この勝利はビザンチン帝国の終焉を意味するだけでなく、オスマン帝国が超大国として台頭した紛れもない象徴でもあった。オスマン帝国の拡大は1517年のカイロ占領まで続き、エジプトの帝国への統合とアッバース朝カリフの終焉を示す重要な出来事となった。スレイマン大帝のもと、オスマン・トルコは1533年にバグダッドも征服し、メソポタミアの豊かで戦略的な土地への影響力を拡大した。

しかし、オスマン帝国の拡張に障害がなかったわけではない。1529年のウィーン包囲は、ヨーロッパでの影響力をさらに拡大しようとする野心的な試みだったが、失敗に終わった。1623年のさらなる試みも失敗に終わり、オスマン帝国の中央ヨーロッパにおける拡大の限界が示された。これらの失敗は、組織化されたヨーロッパの防衛を前にしたオスマン帝国の軍事力と兵站力の限界を示す重要な出来事であった。もう一つの大きな挫折は、1571年のレパントの海戦での敗北である。この海戦でオスマン帝国艦隊はヨーロッパのキリスト教勢力の連合軍に敗れ、オスマン帝国の地中海支配の転機となった。オスマン帝国はこの敗北からなんとか立ち直り、この地域で強力なプレゼンスを維持することができたが、レパントはオスマン帝国の無制限な拡張の終わりを象徴し、地中海におけるよりバランスのとれた海洋ライバル関係の時代の幕開けとなった。これらの出来事を総合すると、オスマン帝国の膨張のダイナミズムがよくわかる。これらの出来事は、このような広大な帝国を管理することの複雑さと、組織化され抵抗力を増した敵に直面しながら絶え間ない拡大を維持することの難しさを浮き彫りにしている。

オスマン帝国の改革と内部変革

1768年から1774年にかけてのオスマン・ロシア戦争は、オスマン帝国の歴史において極めて重要なエピソードであり、オスマン帝国の重大な領土喪失の始まりとなっただけでなく、政治的・宗教的正統性の構造にも変化をもたらした。この戦争の終結は、1774年のキュチュク・カイナルカ条約(またはクチュク・カイナルジ条約)の調印によって示された。この条約はオスマン帝国に大きな影響を与えた。まず、黒海とバルカン半島の一部など、重要な領土をロシア帝国に割譲することになった。この損失は帝国の規模を縮小させただけでなく、東ヨーロッパと黒海地域における戦略的地位を弱めた。第二に、この条約は、オスマン帝国のヨーロッパにおける地位を弱めるという、当時の国際関係の転換点となった。地域情勢における主要かつしばしば支配的なプレーヤーであったオスマン帝国は、ヨーロッパ列強からの圧力や介入に弱い衰退国家として認識され始めたのである。

最後に、そしておそらく最も重要なこととして、この戦争の終結とキュチュク・カイナルカ条約は、オスマン帝国の内部構造にも大きな影響を与えた。こうした敗北を前に、帝国は正統性の源泉としてカリフの宗教的側面をより重視するようになった。オスマン帝国のスルタンは、すでに帝国の政治的指導者として認められていたが、イスラム共同体の宗教的指導者であるカリフとしてより評価されるようになった。このような展開は、内外の挑戦に直面してスルタンの権威と正統性を強化する必要性に応えたものであり、統一的な力と力の源泉としての宗教に依拠したものであった。このように、オスマン・ロシア戦争とその結果として結ばれた条約は、オスマン帝国の歴史の転換点となり、領土の衰退と帝国の正統性の変化を象徴するものとなった。

外国からの影響と国際関係

1801年のエジプト介入は、イギリス軍とオスマン帝国軍が共同でフランス軍を駆逐したもので、エジプトとオスマン帝国の歴史における重要な転換点となった。オスマン帝国がアルバニア人将校のメフメト・アリをエジプトのパシャに任命したことで、エジプトはオスマン帝国から大きく変貌し、半独立の時代を迎えた。近代エジプトの創始者とされるメフメト・アリは、エジプトの近代化を目指した一連の急進的な改革に着手した。これらの改革は、軍隊、行政、経済など様々な側面に影響を与え、ヨーロッパのモデルに触発された部分もあった。彼の指導の下、エジプトは大きな発展を遂げ、メフメト・アリはエジプト国外への影響力の拡大を目指した。このような背景のもと、ナフダ(アラブ・ルネッサンス)は大きな勢いを得た。アラブ文化を活性化し、現代の課題に適応させようとするこの文化的・知的運動は、メフメト・アリによって始められた改革と開放の風潮の恩恵を受けた。

メフメト・アリの息子イブラヒム・パシャは、エジプトの拡張主義的野心において重要な役割を果たした。1836年、彼は当時弱体化し衰退していたオスマン帝国に対して攻勢を開始した。この対決は1839年に頂点に達し、イブラヒム軍はオスマン帝国に大敗を喫した。しかし、イギリス、オーストリア、ロシアをはじめとするヨーロッパ列強の介入により、エジプトの完全勝利は阻まれた。国際的な圧力の下、和平条約が締結され、メフメト・アリとその子孫の支配下におけるエジプトの事実上の自治が承認された。この承認は、エジプトがオスマン帝国から分離する重要な一歩となったが、エジプトは名目上オスマン帝国の宗主国であることに変わりはなかった。イギリスの立場は特に興味深いものだった。当初はエジプトにおけるフランスの影響力を封じ込めるためにオスマン帝国と同盟を結んでいたが、この地域の政治的・戦略的現実の変化を認識し、最終的にはメフメト・アリのもとでのエジプトの自治を支持することを選択した。この決定は、重要な貿易ルート、特にインドにつながるルートを支配しながら、この地域を安定させたいというイギリスの願望を反映したものだった。19世紀初頭のエジプトのエピソードは、オスマン帝国、エジプト、ヨーロッパ列強の間の複雑なパワー・ダイナミクスだけでなく、当時の中東の政治的・社会的秩序に起きていた重大な変化を物語っている。

近代化と改革運動

1798年のナポレオン・ボナパルトのエジプト遠征は、オスマン帝国にとって啓示的な出来事であり、近代化と軍事力の面でヨーロッパ列強に遅れをとっているという事実を浮き彫りにした。この認識は、帝国の近代化と衰退を食い止めるために1839年に開始された、タンジマートとして知られる一連の改革の重要な原動力となった。トルコ語で「再編成」を意味するタンジマートは、オスマン帝国に大きな変革期をもたらした。この改革の重要な側面のひとつは、帝国の非ムスリム市民であるディミの組織の近代化であった。これには、様々な宗教共同体にある程度の文化的・行政的自治を与えるミレー制度の創設も含まれた。その目的は、これらの共同体をオスマン帝国の構造により効果的に統合する一方で、それぞれのアイデンティティを維持することであった。

第二の改革は、宗教的・民族的分裂を超越したオスマン・トルコの市民権を創設する試みであった。しかし、この試みは、多民族・多宗教の帝国内の深い緊張を反映して、しばしば共同体間の暴力によって妨げられた。同時に、こうした改革は軍隊の特定の派閥内で大きな抵抗に会い、彼らは自分たちの伝統的な地位や特権を脅かすと思われる変化に敵対した。この抵抗は反乱や内部の不安定化を招き、帝国が直面する課題を悪化させた。

このような激動の背景の中、19世紀半ばに「若きオスマン」として知られる政治的・知的運動が勃興した。このグループは、近代化と改革の理想をイスラム教とオスマン帝国の伝統の原則と調和させようとした。彼らは憲法、国民主権、より包括的な政治・社会改革を提唱した。タンジマートの努力とヤング・オスマンの理想は、急速に変化する世界の中でオスマン帝国が直面する課題に対応する重要な試みであった。こうした努力はいくつかの前向きな変化をもたらしたが、同時にオスマン帝国内の深い亀裂と緊張を明らかにし、オスマン帝国末期の数十年間に起こるであろうさらに大きな試練を予感させた。

1876年、オスマン帝国初の君主制憲法を導入したスルタン・アブデュルハミド2世が即位し、タンジマートの過程において重要な局面を迎えた。この時期は、近代化の原則と帝国の伝統的な構造を調和させようとする重要な転換点となった。1876年に制定された憲法は、帝国の行政を近代化し、当時のヨーロッパで流行していた自由主義と立憲主義の理想を反映した立法制度と議会を確立しようとするものだった。しかし、アブデュルハミド2世の治世は、欧米列強との対立の激化を背景に、帝国内外のムスリム間の結びつきを強めることを目的としたイデオロギー、汎イスラム主義が強く台頭した時期でもあった。

アブデュルハミド2世は、汎イスラーム主義を自らの権力を強化し、外部からの影響に対抗するための手段として用いた。イスラム教の指導者や高官をイスタンブールに招き、彼らの子供たちをオスマン帝国の首都で教育することを提案した。しかし1878年、アブデュルハミド2世は驚くべき方向転換を行い、憲法を停止して議会を閉鎖し、独裁的な支配に戻った。この決定の背景には、政治プロセスに対する統制が不十分であったことと、帝国内で民族主義運動が台頭してきたことへの懸念があった。こうしてスルタンは、政府に対する直接支配を強化する一方で、正当化の手段として汎イスラム主義を推進し続けた。

このような状況の中で、第一世代のイスラームの実践への回帰を目指す運動であるサラフィズムは、汎イスラーム主義とナハダ(アラブ・ルネサンス)の理想の影響を受けた。現代のサラフィズム運動の先駆者とされるジャマール・アル=ディン・アル=アフガーニーは、こうした思想の普及に重要な役割を果たした。アル=アフガーニーは、技術的・科学的な近代化のある種の導入を奨励する一方で、イスラームの本来の原理への回帰を提唱した。このように、タンズィマート時代とアブデュルハミド2世の治世は、近代化の要求と伝統的な構造やイデオロギーの維持の間で引き裂かれたオスマン帝国における改革の試みの複雑さを物語っている。この時代の影響は、帝国の滅亡を越えて、現代のイスラム世界全体の政治的・宗教的運動に影響を与えた。

オスマン帝国の衰退と滅亡

「東方問題」とは、主に19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて使われた用語で、徐々に衰退していくオスマン帝国の将来に関する複雑かつ多角的な議論を指す。この問題は、帝国の相次ぐ領土喪失、トルコ・ナショナリズムの台頭、特にバルカン半島における非イスラム地域からの分離の進展の結果として浮上した。早くも1830年、ギリシャの独立によってオスマン帝国はヨーロッパ領土を失い始めた。この傾向はバルカン戦争で続き、第一次世界大戦で加速し、1920年のセーヴル条約と1923年のムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルク率いるトルコ共和国の建国に至った。これらの敗北は、この地域の政治的地理を大きく変えた。

こうした中、トルコのナショナリズムが勢いを増した。この運動は、それまでの多民族・多宗教モデルとは対照的に、トルコ的要素を中心に帝国のアイデンティティを再定義しようとするものだった。このようなナショナリズムの台頭は、帝国が徐々に解体し、新たな国民的アイデンティティを形成する必要性に直接反応したものであった。同時に、汎イスラム主義を掲げたスルタン・アブデュルハミド2世を中心に、一種の「イスラムの国際」を形成しようという構想が生まれた。この考え方は、国境を越えて民族を団結させようとする国際主義のヨーロッパにおける同様の考え方に触発され、イスラム諸国間の連合や協力を構想したものであった。その目的は、イスラムの領土の利益と独立を守りながら、西欧列強の影響と介入に抵抗するために、イスラム諸国民の統一戦線を作ることであった。

しかし、このような思想の実現は、多様な国益、地域的対立、民族主義思想の影響力の増大のために困難であることが判明した。さらに、第一次世界大戦やオスマン帝国各地での民族主義運動の台頭をはじめとする政治的展開によって、「イスラムの国際」というビジョンはますます実現不可能なものとなっていった。したがって、「東方問題」全体は、この時期にこの地域で起こった地政学的・イデオロギー的な大変革を反映している。

19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてドイツが採用した「世界政策」(Weltpolitik)は、オスマン帝国を巻き込んだ地政学的力学において重要な役割を果たした。カイザー・ヴィルヘルム2世の時代に始まったこの政策は、特に植民地拡大と戦略的同盟関係を通じて、国際舞台におけるドイツの影響力と威信を拡大することを目的としていた。ロシアとイギリスからの圧力から逃れようとしていたオスマン帝国は、ドイツに有用な同盟国の可能性を見出したのである。この同盟は、特にベルリン・バグダッド鉄道(BBB)建設プロジェクトに象徴される。ビザンティウム(イスタンブール)を経由してベルリンとバグダッドを結ぶこの鉄道は、戦略的・経済的に非常に重要なものだった。この鉄道は、貿易と通信を容易にするだけでなく、この地域におけるドイツの影響力を強化し、中東におけるイギリスとロシアの利害に対抗するためのものだった。

パントゥルキストやオスマン帝国支持者にとって、ドイツとの同盟は好意的に受け止められていた。トルコ語圏諸民族の統一と連帯を主張するパントゥルキストは、この同盟にオスマン帝国の地位を強化し、対外的脅威に対抗する機会を見出した。ドイツとの同盟は、長い間オスマン帝国の政治や情勢に影響を及ぼしてきたロシアやイギリスといった伝統的な大国からの圧力に代わる選択肢を提供するものであった。オスマン帝国とドイツのこの関係は、第一次世界大戦中に両国の同盟関係が中央列強の中でピークに達した。この同盟はオスマン帝国にとって軍事的にも政治的にも重要な結果をもたらし、最終的には戦後の帝国解体へとつながる出来事の一翼を担った。ドイツのヴェルトポリティークとベルリン・バグダッド鉄道計画は、列強からの圧力に直面しながらもオスマン帝国の完全性と独立性を維持するための戦略における重要な要素であった。この時期は、20世紀初頭における同盟関係と地政学的利害の複雑さを示す、帝国の歴史における重要な瞬間であった。

1908年、オスマン帝国の歴史において決定的な転機となったのは、主に統一進歩委員会(CUP)に代表される青年トルコ人運動が引き起こした第二次憲法制定期の開始であった。この運動は当初、オスマン帝国の改革派将校や知識人によって結成され、帝国の近代化と崩壊からの救済を目指した。

CUPの圧力により、スルタン・アブデュルハミド2世は1878年以来停止していた1876年憲法を復活させ、第二次憲法時代の幕開けとなった。この憲法の復活は、帝国の近代化と民主化への一歩と見なされ、より広範な市民的・政治的権利と議会政治の確立が約束された。しかし、この改革期はすぐに大きな試練に直面した。1909年、伝統的な保守派と宗教界は、改革と連合派の影響力の拡大に不満を抱き、立憲政府を転覆させてスルタンの絶対的権威を再確立するクーデターを企てた。この試みは、青年トルコ人が推進した急速な近代化と世俗化政策への反対、特権と影響力の喪失への懸念が動機となっていた。しかし、青年トルコ人はこの反革命のエピソードを口実に、抵抗勢力を鎮圧し、権力を強化することに成功した。この時期、反対派に対する弾圧が強まり、CUPの手に権力が集中した。

1913年、この状況は、しばしばクーデターと形容される、CUP指導者による議会占拠で頂点に達した。これにより、オスマン帝国の短期間の立憲制と議会制の試みは終わりを告げ、青年トルコ人によるますます権威主義的な体制が確立された。彼らの支配下でオスマン帝国は大幅な改革を行ったが、同時に中央集権的で民族主義的な政策も強め、第一次世界大戦中とその後に展開される出来事の基礎を築いた。この激動の時代は、オスマン帝国内部の緊張と闘争を反映しており、変化と伝統の力の間で引き裂かれ、帝国の晩年に続く急進的な変革の基礎を築いた。

第一次世界大戦中の1915年、オスマン帝国は、現在ではアルメニア人大虐殺として広く認識されている、歴史上の悲劇的で暗いエピソードに着手した。この政策は、帝国内に居住するアルメニア人を組織的に追放し、大量殺戮し、殺害するというものであった。アルメニア人に対するキャンペーンは、逮捕、処刑、大量追放から始まった。アルメニア人の男性、女性、子供、老人は家を追われ、シリアの砂漠を死の行進に送られ、多くの者が飢え、渇き、病気、暴力で死んだ。この地域で長く豊かな歴史を築いてきた多くのアルメニア人コミュニティが破壊された。

犠牲者数の見積もりはさまざまだが、一般に80万人から150万人のアルメニア人がこの期間に亡くなったと考えられている。ジェノサイドは、世界のアルメニア人コミュニティに永続的な影響を与え、少なくとも一部のグループによる否定や軽視のために、大きな感受性と論争の対象であり続けている。アルメニア人虐殺は、しばしば最初の近代的大量虐殺のひとつとみなされ、20世紀における他の集団残虐行為の暗い先駆けとしての役割を果たした。また、現代のアルメニア人のアイデンティティの形成にも重要な役割を果たし、ジェノサイドの記憶はアルメニア人の意識の中心であり続けている。これらの出来事の認識と記念は、国際関係、特に人権とジェノサイドの防止に関する議論において、重要な問題であり続けている。

ペルシャ帝国

ペルシア帝国の起源と完成

現在イランとして知られるペルシア帝国の歴史は、王朝交代や外国からの侵略にもかかわらず、文化的・政治的に印象的な連続性を持っていることが特徴である。この継続性は、この地域の歴史的、文化的進化を理解する上で重要な要素である。

紀元前7世紀初頭に成立したメデス帝国は、イランの歴史における最初の大国のひとつである。この帝国は、イラン文明の基礎を築く上で重要な役割を果たした。しかし、紀元前550年頃、キュロス大王としても知られるペルシアのキュロス2世によって打倒された。キュロスによるメディア征服は、アケメネス朝の始まりであり、この時代には大きな拡大と文化的影響力があった。アケメネス朝はインダス川からギリシャに至る広大な帝国を築き、その統治は効率的な行政と帝国内の異なる文化や宗教に対する寛容な政策によって特徴づけられた。この帝国は、紀元前330年にアレクサンダー大王によって滅亡させられたが、ペルシャの文化的な連続性に終止符が打たれたわけではなかった。

ヘレニズム支配と政治的分裂の時代を経て、西暦224年にサーサーン朝が勃興した。アルダシール1世によって建国されたこの王朝は、西暦624年まで続き、この地域の新しい時代の幕開けとなった。サーサーン朝のもと、大イランは文化的・政治的ルネッサンス期を迎えた。首都クテシフォンは、帝国の壮大さと影響力を反映し、権力と文化の中心となった。サーサーン朝は、この地域の芸術、建築、文学、宗教の発展に重要な役割を果たした。彼らはゾロアスター教を支持し、ペルシャ文化とアイデンティティに大きな影響を与えた。彼らの帝国はローマ帝国、後にビザンチン帝国との絶え間ない対立に見舞われ、その結果、両帝国を弱体化させる高価な戦争に発展した。7世紀のイスラムによる征服の後、サーサーン朝は滅亡したが、ペルシアの文化と伝統は、後のイスラム時代においても、この地域に影響を与え続けた。この回復力と、独特の文化的核を維持しながら新しい要素を統合する能力が、ペルシャ史における継続性の概念の核心である。

イスラーム支配下のイラン征服と変容

642年以降、イランはイスラム教徒の征服を受け、イスラム時代が始まり、その歴史において新たな時代を迎えた。この時代は、この地域の政治史のみならず、社会的、文化的、宗教的構造においても重要な転換点となった。イスラム軍によるイランの征服は、632年の預言者モハメッドの死後まもなく始まった。642年、サーサーン朝の首都クテシフォンを占領すると、イランは新興のイスラム帝国の支配下に入った。この移行は、軍事衝突と交渉の両方を含む複雑なプロセスであった。イスラムの支配下で、イランは大きな変化を遂げた。それまでの帝国下で国教であったゾロアスター教に代わって、イスラム教が徐々に支配的な宗教となった。しかし、この移行は一夜にして起こったわけではなく、異なる宗教的伝統の共存と相互作用の時期があった。

イランの文化と社会はイスラムの影響を大きく受けたが、イスラム世界にも大きな影響を及ぼした。イランはイスラム文化と知識の重要な中心地となり、哲学、詩、医学、天文学などの分野で目覚ましい貢献をした。詩人ルーミーや哲学者アヴィセンナ(イブン・シーナ)といったイランを象徴する人物は、イスラムの文化的・知的遺産において大きな役割を果たした。この時代には、ウマイヤ朝、アッバース朝、サファリ朝、サーマーン朝、ブーイド朝、後のセルジューク朝といった歴代王朝も登場し、それぞれがイランの歴史の豊かさと多様性に貢献した。これらの王朝はそれぞれ、この地域の統治、文化、社会に独自のニュアンスをもたらした。

セフェヴィト朝の出現と影響

1501年、シャー・イスマイル1世がアゼルバイジャンにセフェヴィト朝を建国し、イランと中東の歴史に大きな出来事が起こった。これはイランだけでなく、この地域全体にとって新しい時代の幕開けとなった。国教としてドゥオデシマン・シーア派が導入され、この変化はイランの宗教的・文化的アイデンティティに大きな影響を与えた。1736年まで君臨したセフェヴィド帝国は、イランを独自の政治的・文化的存在として確固たるものにする上で重要な役割を果たした。カリスマ的指導者であり、才能豊かな詩人でもあったシャー・イスマーイール1世は、さまざまな地域を支配下にまとめ、中央集権的で強力な国家を作り上げることに成功した。彼の最も重要な決断のひとつは、十二進法のシーア派を帝国の公式宗教として押し付けたことであり、この行為はイランと中東の将来に重大な影響を及ぼした。

このイランの「シーア派化」は、スンニ派住民やその他の宗教集団を強制的にシーア派に改宗させるもので、イランをスンニ派の隣国、特にオスマン帝国と差別化し、セフェヴィト朝の権力を強化するための意図的な戦略であった。この政策はまた、イランのシーア派のアイデンティティを強化する効果もあり、それは今日に至るまでイラン国家の特徴となっている。セフェヴィー朝の時代、イランは文化・芸術のルネッサンス期を迎えた。首都イスファハーンは、イスラム世界で最も重要な芸術、建築、文化の中心地のひとつとなった。セフェヴィト朝は、絵画、書道、詩、建築などの芸術の発展を奨励し、豊かで永続的な文化遺産を築いた。しかし、オスマン帝国やウズベク族との戦争など、帝国内外の紛争にも見舞われた。これらの紛争は、内部的な課題とともに、最終的には18世紀の帝国の衰退につながった。

1514年に起こったチャルディランの戦いは、セファルディ帝国とオスマン帝国の歴史において重要な出来事であり、軍事的な転換点となっただけでなく、2つの帝国の間に重要な政治的分水嶺が形成されたことを示すものである。この戦いでは、シャー・イスマイル1世率いるセフェヴ朝軍が、スルタン・セリム1世率いるオスマン帝国軍と激突した。セフェヴ朝軍は勇敢に戦ったものの、オスマン帝国軍の技術的優位、特に大砲の効果的な使用により、オスマン帝国軍に敗北した。この敗北はセファルディ帝国に大きな影響を与えた。カルディランの戦いの直接的な結果のひとつは、セフェヴィッド朝にとって大きな領土の喪失であった。オスマン・トルコはアナトリアの東半分を占領することに成功し、この地域におけるセフェヴィト朝の影響力を大幅に縮小させた。この敗北はまた、両帝国の間に永続的な政治的境界線を築き、この地域の重要な地政学的指標となった。セフェヴィト朝の敗北は、シャー・イスマイル1世と彼のシーア派化政策を支持していた宗教共同体であるアレヴィ派にも影響を与えた。セフェヴィト朝のシャーへの忠誠と、オスマン帝国の支配的なスンニ派の慣習とは相容れない独自の宗教的信条が原因だった。

チャルディランでの勝利の後、スルタン・セリム1世は拡大を続け、1517年にはカイロを征服し、アッバース朝カリフ制に終止符を打った。この征服は、オスマン帝国をエジプトにまで拡大しただけでなく、イスラム教スンニ派世界に対する宗教的・政治的権威を象徴するカリフの称号を得たことで、有力なイスラム指導者としてのスルタンの地位を強化した。したがって、チャルディランの戦いとその余波は、当時の2大イスラム勢力間の激しい対立を物語っており、中東の政治的、宗教的、領土的歴史を大きく形成した。

カージャール朝とイランの近代化

1796年、イランではアガ・モハンマド・ハーン・カージャールによって新たな支配王朝カージャール朝が誕生した。トルクメン出身のこの王朝は、ザンド朝に代わって20世紀初頭までイランを支配した。アガ・モハンマド・ハーン・カジャールは、イランのさまざまな派閥と領土を統一した後、1796年に自ら国王を宣言し、カジャール朝による支配が正式に始まった。この時代は、イランの歴史においていくつかの重要な意味を持つ。カージャール朝の下、イランは長年の混乱と内部分裂の後、権力の集中化と領土の統合を経験した。首都はシーラーズからテヘランに移され、テヘランはイランの政治と文化の中心となった。この時代には、複雑な国際関係、特に当時の帝国主義大国であったロシアやイギリスとの関係も顕著であった。カージャール朝は困難な国際環境を切り抜けなければならず、イランはしばしば大国の地政学的対立、特にロシアとイギリスの「グレート・ゲーム」に巻き込まれた。このような相互作用によって、イランはしばしば領土を失い、経済的・政治的に大きな譲歩を余儀なくされた。

文化面では、カージャール朝はその独特な芸術、特に絵画、建築、装飾芸術で知られている。カージャール朝宮廷は芸術の庇護の中心であり、この時代には伝統的なイランの様式と近代的なヨーロッパの影響がユニークに融合していた。しかし、カージャール朝は国の近代化を効果的に進めることができず、国民のニーズに応えられなかったという批判もあった。この失敗は国内の不満につながり、20世紀初頭に起こった改革運動や憲法革命の基礎を築いた。カージャール朝はイランの歴史において重要な時期であり、中央集権化への努力、外交的挑戦、文化的貢献が顕著であった。

20世紀のイラン:立憲君主制へ向けて

1906年、イランは立憲政体時代の開始という歴史的瞬間を経験した。この発展は、君主の絶対的権力の制限と、より代表的で立憲的な統治を求める社会的・政治的運動の影響を大きく受けた。イラン立憲革命により、1906年にイラン初の憲法が採択され、イランは立憲君主制へと移行した。この憲法は、議会(マジュリス)の創設を規定し、イランの社会と政府を近代化・改革するための法律と機構を整備した。しかし、この時期は、外国からの干渉や国内の勢力圏の分裂が顕著であった。イランはイギリスとロシアの対立に巻き込まれ、それぞれがこの地域での影響力を拡大しようとしていた。これらの大国はそれぞれ異なる「国際秩序」や勢力圏を確立し、イランの主権を制限した。

1908年から1909年にかけての石油の発見は、イランの状況に新たな局面をもたらした。マスジェド・ソレイマン地域で発見されたこの石油は、イランの石油資源を支配しようとする諸外国、特にイギリスの注目を一気に集めた。この発見は、国際舞台におけるイランの戦略的重要性を著しく高めるとともに、イラン国内の力学を複雑にした。このような外圧や天然資源にまつわる利害にもかかわらず、イランは中立政策を維持し、特に第一次世界大戦のような世界的な紛争の際には中立を貫いた。この中立は、自国の自治を守り、資源を開発し政治を支配しようとする外国の影響に抵抗しようとする試みでもあった。20世紀初頭は、イランにとって変化と挑戦の時代であり、政治的近代化への努力、石油の発見による新たな経済的挑戦の出現、複雑な国際環境における航海などが特徴的であった。

第一次世界大戦におけるオスマン帝国

外交工作と同盟の形成

オスマン帝国が1914年に第一次世界大戦に参戦する以前には、イギリス、フランス、ドイツをはじめとする複数の大国を巻き込んだ複雑な外交・軍事工作が行われていた。イギリス、フランスとの同盟の可能性を模索した後、オスマン帝国は最終的にドイツとの同盟を選択した。この決定には、オスマン帝国とドイツとの間にすでに存在した軍事的・経済的関係や、他のヨーロッパの大国の意図に対する認識など、いくつかの要因が影響した。

この同盟にもかかわらず、オスマン帝国は国内の困難と軍事的限界を認識していたため、紛争に直接参戦することには消極的であった。しかし、ダーダネルス海峡事件で状況は一変した。オスマン帝国は軍艦(一部はドイツから譲り受けた)を使って黒海のロシアの港を砲撃した。この行動により、オスマン帝国は中央列強とともに、ロシア、フランス、イギリスをはじめとする連合国との戦争に巻き込まれた。

オスマン帝国の参戦を受けて、イギリスは1915年にダーダネルス海峡作戦を開始した。その目的は、ダーダネルス海峡とボスポラス海峡を掌握し、ロシアへの海路を開くことだった。しかし、この作戦は連合軍にとって失敗に終わり、双方に多くの犠牲者を出す結果となった。同じ頃、イギリスはエジプトに対する支配権を正式に確立し、1914年にイギリス領エジプト保護領を宣言した。この決定は戦略的な動機に基づくもので、イギリスの航路、特にアジアの植民地へのアクセスに不可欠なスエズ運河を確保することが主な目的だった。これらの出来事は、第一次世界大戦中の中東における地政学的状況の複雑さを物語っている。オスマン帝国が下した決断は、自らの帝国にとってだけでなく、戦後の中東の構成にも重要な影響を及ぼした。

アラブの反乱と中東のダイナミクスの変化

第一次世界大戦中、連合国は南部に新たな戦線を開くことでオスマン帝国の弱体化を図り、1916年の有名なアラブの反乱を引き起こした。この反乱は中東の歴史において重要な出来事であり、アラブ民族主義運動の始まりとなった。メッカのシェリフ、フセイン・ベン・アリはこの反乱で中心的な役割を果たした。彼の指導の下、「アラビアのロレンス」として知られるT.E.ロレンスなどの励ましと支援を受けて、アラブ人はオスマン帝国の支配に対抗し、統一アラブ国家の樹立を目指して立ち上がった。この独立と統一への熱望は、民族解放への願望と、イギリス、特にヘンリー・マクマホン将軍による自治の約束が動機となっていた。

アラブの反乱はいくつかの重要な成功を収めた。1917年6月、フセイン・ベン・アリの息子であるファイサルがアカバの戦いに勝利した。この勝利により、オスマン帝国に対する重要な戦線が開かれ、アラブ軍の士気が高まった。アラビアのロレンスやその他のイギリス人将校の協力を得て、ファイサルはヒジャーズのアラブ諸部族をまとめることに成功し、1917年のダマスカス解放につながった。1920年、ファイサルはシリア国王を宣言し、自決と独立を求めるアラブの願望を肯定した。しかし、彼の野心は国際政治の現実に直面した。1916年のサイクス・ピコ協定(英仏間の秘密協定)は、すでに中東の大部分を勢力圏に分割しており、アラブ統一王国への期待は失われていた。アラブの反乱は、戦争中にオスマン帝国を弱体化させる決定的な要因となり、近代アラブ・ナショナリズムの基礎を築いた。しかし、戦後はヨーロッパの委任統治下で中東は多くの国民国家に分割され、フセイン・ベン・アリとその支持者が構想したアラブ統一国家の実現は遠のいた。

内乱とアルメニア人虐殺

第一次世界大戦は、1917年のロシア革命の結果、ロシアが紛争から撤退するなど、複雑な展開と力学の変化によって特徴づけられた。この撤退は、戦争の行方と他の交戦国に大きな影響を与えた。ロシアの撤退により、中央列強、特にドイツへの圧力が緩和され、ドイツはフランスとその同盟国に対して西部戦線に兵力を集中させることができるようになった。この変化は、パワーバランスを維持する方法を模索していたイギリスとその同盟国を悩ませた。

ボリシェヴィキのユダヤ人に関しては、1917年のロシア革命とボリシェヴィズムの台頭が、ロシア国内のさまざまな要因に影響された複雑な現象であったことに注意することが重要である。当時の多くの政治運動と同様、ボリシェヴィキの中にもユダヤ人は存在したが、その存在を過度に解釈したり、単純化した反ユダヤ主義的な物語の推進に利用すべきではない。オスマン帝国に関しては、青年トルコ運動の指導者の一人であり陸軍大臣でもあったエンヴェル・パシャが戦争遂行に重要な役割を果たした。1914年、彼はコーカサス地方でロシア軍に対する悲惨な攻勢を開始し、その結果、サリカミシュの戦いでオスマン帝国は大敗北を喫した。

エンヴェル・パシャの敗北は、アルメニア人大虐殺の勃発など悲劇的な結果をもたらした。エンヴェル・パシャをはじめとするオスマン帝国の指導者たちは、敗戦を説明するスケープゴートを求めて、帝国の少数民族であるアルメニア人がロシアと結託していると非難した。この告発は、アルメニア人に対する組織的な強制送還、虐殺、絶滅のキャンペーンを煽り、現在アルメニア人大虐殺として認識されているものにまで発展した。この大虐殺は、第一次世界大戦とオスマン帝国の歴史における最も暗いエピソードのひとつであり、大規模な紛争と民族憎悪政策の恐怖と悲劇的な結末を浮き彫りにしている。

戦後の和解と中東の再定義

1919年1月に始まったパリ講和会議は、第一次世界大戦後の世界秩序を再定義する上で極めて重要な出来事であった。この会議では、主要連合国の首脳が一堂に会し、破綻したオスマン帝国の領土を含む和平の条件と地政学的将来について話し合った。会議で話し合われた主要な問題のひとつは、中東におけるオスマン帝国領の将来に関するものだった。連合国は、石油資源の支配を含むさまざまな政治的、戦略的、経済的配慮に影響され、この地域の国境線の引き直しを検討していた。会議では理論上、関係諸国がそれぞれの見解を示すことができたが、実際にはいくつかの代表団は疎外されたり、要求が無視されたりした。たとえば、エジプトの独立を議論しようとしたエジプト代表団は、メンバーの一部がマルタに亡命するなど、障害に直面した。このような状況は、ヨーロッパ列強の利害が優先されることが多かった会議での不平等なパワー・ダイナミクスを反映している。

フセイン・ビン・アリの息子でアラブ反乱の指導者であったファイサルは、会議で重要な役割を果たした。彼はアラブの利益を代表し、アラブの独立と自治の承認を主張した。彼の努力にもかかわらず、会議での決定は独立統一国家を求めるアラブの願望を十分に満たすものではなかった。ファイサルはシリアに国家を建設し、1920年にシリア国王を宣言した。1916年のサイクス・ピコ協定に基づくヨーロッパ列強の中東分割の一環であった。したがって、パリ会議とその成果は中東に大きな影響を与え、今日まで続く多くの地域的緊張と紛争の基礎を築いた。下された決定は、第一次世界大戦の戦勝国の利益を反映したものであり、しばしばこの地域の人々の民族的願望を損なうものであった。

フランスを代表するジョルジュ・クレマンソーとアラブ反乱の指導者ファイサルとの間の協定、および中東における新国家創設をめぐる議論は、この地域の地政学的秩序を形成した第一次世界大戦後の重要な要素である。クレマンソーとフェイサルの合意は、フランスにとって非常に有利なものと見なされた。アラブ領土の自治権を確保しようとしたフェイサルは、大幅な譲歩を余儀なくされた。この地域に植民地的・戦略的利益を持つフランスは、パリ会議での立場を利用して、特にシリアやレバノンなどの領土に対する支配権を主張した。レバノン代表団は、フランスの委任統治下に大レバノンという独立国家を創設する権利を獲得した。この決定には、レバノンのマロン派キリスト教社会が、フランスの指導の下、国境を拡大し、ある程度の自治権を持つ国家の樹立を望んでいたことが影響していた。クルド人問題については、クルディスタンの創設が約束された。この約束は、クルド人の民族主義的願望を認め、オスマン帝国を弱体化させる手段でもあった。しかし、この約束の履行は複雑であることが判明し、戦後の条約ではほとんど無視された。

これらの要素は1920年のセーヴル条約に集約され、オスマン帝国の分割が正式に決定された。この条約によって中東の国境が塗り替えられ、フランスとイギリスの委任統治下に新しい国家が誕生した。この条約では、クルド人の自治組織の創設も規定されたが、この規定は実施されることはなかった。セーヴル条約は完全には批准されず、後に1923年のローザンヌ条約に取って代わられたが、この地域の歴史において決定的な出来事だった。この条約は中東の近代的な政治構造の基礎を築いたが、同時に、この地域の民族的、文化的、歴史的現実を無視したために、将来の多くの紛争の種をまいた。

共和制への移行とアタテュルクの台頭

第一次世界大戦終結後、弱体化し圧力を受けていたオスマン帝国は、1920年にセーヴル条約に調印することに同意した。オスマン帝国を解体し、領土を再分配したこの条約は、帝国の命運をめぐる長年にわたる「東方問題」の終結を意味するように思われた。しかし、セーブル条約はこの地域の緊張を終わらせるどころか、民族主義的感情を悪化させ、新たな紛争を引き起こした。

トルコでは、セーヴル条約に反対するムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルク率いる強力な民族主義レジスタンスが結成された。この民族主義運動は、オスマン帝国領土に深刻な領土損失を課し、外国の影響力を増大させる条約の条項に反対した。レジスタンスは、アルメニア人、アナトリアのギリシア人、クルド人などさまざまな集団と戦い、新しい均質なトルコ民族国家を建設することを目指した。続くトルコ独立戦争は、激しい対立と領土の再編成の時代であった。トルコ民族主義勢力はアナトリアでギリシャ軍を押し返し、他の反乱軍に対抗することに成功した。この軍事的勝利は、1923年のトルコ共和国建国の重要な要素となった。

これらの出来事の結果、1923年、セーヴル条約はローザンヌ条約に取って代わられた。この新しい条約は、新トルコ共和国の国境を承認し、セーヴル条約の最も懲罰的な条項を取り消した。ローザンヌ条約は、近代トルコが主権を持つ独立国家として確立する上で重要な段階を示し、この地域と国際情勢におけるトルコの役割を再定義した。これらの出来事は中東の政治地図を塗り替えただけでなく、オスマン帝国の終焉を意味し、トルコの歴史に新たな1ページを開いた。

カリフ制の廃止とその波紋

1924年のカリフ制の廃止は、何世紀にもわたって続いたイスラム制度の終焉を意味し、中東の近代史における大きな出来事であった。この決定は、トルコ共和国の建国者であるムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクが、新トルコ国家の世俗化と近代化を目指した改革の一環として下したものであった。カリフ制の廃止は、伝統的なイスラムの権威構造に打撃を与えた。カリフは預言者モハメッドの時代から、イスラム共同体(ウンマ)の精神的・時間的な長であると考えられていた。カリフの廃止によって、このスンニ派イスラムの中心的な制度は消滅し、イスラム指導者の空白が残された。

トルコのカリフ制廃止に対抗して、オスマン帝国崩壊後にヒジャーズ王となったフセイン・ベン・アリがカリフを宣言した。フセインは預言者ムハンマドの直系子孫であるハシェミット家の一員であり、イスラム世界における精神的・政治的連続性を維持するためにこの地位を主張しようとした。しかし、フセインのカリフに対する主張は広く認められることはなく、短命に終わった。フセインの地位は、アラビア半島の大部分を支配していたサウド家の反対など、内外の挑戦によって弱体化した。アブデラズィーズ・イブン・サウード率いるサウード家の台頭は、やがてヒジャーズの征服とサウジアラビア王国の成立につながった。サウードによるフセイン・ビン・アリーの追放は、アラビア半島における権力の急進的な変化を象徴し、カリフ制への野望の終焉を意味した。この出来事はまた、イスラム世界で進行中の政治的・宗教的変革を浮き彫りにし、多くのイスラム諸国で政治と宗教がより明確な道を歩み始める新時代の幕開けとなった。

第一次世界大戦後の時期は、中東の政治的再定義にとって極めて重要な時期であり、特にフランスとイギリスをはじめとするヨーロッパ列強による重要な介入があった。1920年、シリアで大きな出来事が起こり、この地域の歴史に転機が訪れた。フセイン・ベン・アリの息子でアラブ反乱の中心人物であったファイサルは、オスマン帝国崩壊後のシリアにアラブ王国を樹立し、アラブ統一国家の夢を実現しようとしていた。しかし、彼の野望はフランスの植民地利益という現実に直面することになる。1920年7月のメイサルーンの戦いの後、国際連盟の委任統治下にあったフランスはダマスカスを支配下に置き、ファイサルのアラブ国家を解体し、彼のシリア支配を終わらせた。このフランスの介入は、中東諸国民の民族的願望がしばしばヨーロッパ列強の戦略的利益の影に隠れてしまうという、戦後の複雑な力学を反映していた。シリアの王位を追われたフェイサルは、それでもイラクに新たな運命を見出した。1921年、イギリスの支援のもと、彼はイラクのハシェミット王国の初代国王に任命された。これは、石油が豊富なこの地域に有利な指導力と安定性を確保するためのイギリス側の戦略的な動きであった。

同じ頃、トランスヨルダンでは、イギリスによる別の政治工作が行われた。パレスチナにおけるシオニストの願望を阻止し、委任統治領の均衡を保つため、1921年にトランスヨルダン王国を創設し、フセイン・ベン・アリのもう一人の息子アブダッラーをそこに据えた。この決定は、パレスチナをイギリスの直接支配下に置きつつ、アブダラに統治する領土を提供することを意図したものだった。トランスヨルダンの設立は、近代ヨルダン国家形成の重要な一歩であり、植民地的利害がいかに近代中東の国境と政治構造を形成したかを示すものであった。第一次世界大戦後のこの地域におけるこうした動きは、戦間期における中東政治の複雑さを示している。自国の戦略的・地政学的利益に影響されたヨーロッパの代理国が下した決断は永続的な結果をもたらし、中東に影響を与え続ける国家構造や紛争の基礎を築いた。これらの出来事はまた、この地域の人々の民族的願望とヨーロッパの植民地支配の現実との間の闘争を浮き彫りにしている。

サンレモ会議の波紋

1920年4月に開催されたサンレモ会議は、第一次世界大戦後の歴史、特に中東の歴史にとって決定的な出来事であった。この会議では、オスマン帝国の敗戦と解体後、かつてのオスマン帝国の地方に対する委任統治権の割り当てが焦点となった。この会議で、勝利した連合国は委任統治領の分配を決定した。フランスはシリアとレバノンの委任統治権を獲得し、戦略的に重要で文化的にも豊かな2つの地域を支配することになった。イギリスはトランスヨルダン、パレスチナ、メソポタミアの委任統治権を与えられ、後者はイラクと改名された。これらの決定は、植民地支配国の地政学的、経済的利益、特に資源へのアクセスと戦略的支配の利益を反映したものであった。

こうした動きと並行して、トルコはムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの指導の下、国家の再定義のプロセスに取り組んでいた。戦後、トルコは新たな国境を確立しようとした。この時期には悲劇的な紛争、特に戦争中に行われたアルメニア人大虐殺に続くアルメニア人潰しがあった。1923年、数年にわたる闘争と外交交渉の末、ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクはセーヴル条約の再交渉に成功した。セーヴル条約は1920年にトルコに課されたもので、トルコの民族主義者にとっては屈辱的で受け入れがたいものであった。1923年7月に調印されたローザンヌ条約は、セーヴル条約に代わり、新トルコ共和国の主権と国境を承認した。この条約はオスマン帝国の公式な終焉を意味し、近代トルコ国家の基礎を築いた。

ローザンヌ条約は、ムスタファ・ケマルとトルコの民族主義運動にとって大きな成功だったと考えられている。トルコの国境を再定義しただけでなく、新共和国はセーヴル条約の制約から解放され、国際舞台で新たなスタートを切ることができた。サンレモ会議からローザンヌ条約調印に至るこれらの出来事は、中東に多大な影響を与え、国境、国際関係、そしてこの地域の政治力学をその後数十年にわたって形成した。

連合国の約束とアラブの要求

第一次世界大戦中、オスマン帝国の解体と分割は、イギリス、フランス、ロシアを中心とする連合国の関心の中心であった。これらの列強は、中央列強の同盟国であるオスマン帝国に対する勝利を予期し、その広大な領土の分割を計画し始めた。

第一次世界大戦が激化していた1915年、コンスタンチノープルでイギリス、フランス、ロシアの代表が参加する重要な交渉が行われた。この話し合いの中心は、当時中央列強と同盟関係にあったオスマン帝国の領土の将来についてだった。オスマン帝国は弱体化し、衰退していたため、連合国側は勝利の暁には分割される領土とみなしていた。コンスタンチノープルでの交渉は、戦略的、植民地的な利害によって強く動機づけられていた。各勢力は、地理的位置と資源から戦略的に重要なこの地域での影響力を拡大しようとした。ロシアは特に、地中海へのアクセスに不可欠なボスポラス海峡とダーダネルス海峡の支配に関心を寄せていた。一方、フランスとイギリスは植民地帝国を拡大し、この地域の資源、特に石油へのアクセスを確保しようとしていた。しかし、これらの話し合いはオスマン帝国領の将来に大きな影響を及ぼしたものの、その分割に関する最も重要で詳細な合意は、特に1916年のサイクス・ピコ協定において、後に正式なものとなったことに留意することが重要である。

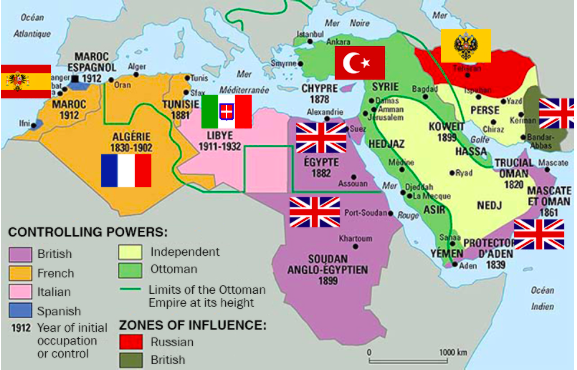

イギリスの外交官マーク・サイクスとフランスの外交官フランソワ・ジョルジュ=ピコによって締結された1916年のサイクス=ピコ協定は、中東の歴史における重要な瞬間であり、第一次世界大戦後のこの地域の地政学的構成に大きな影響を与えた。この協定は、オスマン帝国の領土をイギリス、フランス、そしてある程度ロシアとの間で分割することを定めたものであったが、ロシアの参加は1917年のロシア革命によって無効となった。サイクス・ピコ協定は、中東におけるフランスとイギリスの勢力圏と支配圏を確立した。この協定により、フランスはシリアとレバノンを直接支配または影響力を得ることになり、イギリスはイラク、ヨルダン、パレスチナ周辺地域を同様に支配することになった。しかし、この協定は将来の国家の国境を正確に定めたものではなく、後の交渉と協定に委ねられた。

サイクス・ピコ協定の重要性は、中東の地理的空間に関する集団的記憶の「起源」としての役割にある。この協定は、しばしば現地の民族的、宗教的、文化的アイデンティティを無視した、ヨーロッパ列強のこの地域への帝国主義的介入と操作を象徴している。この協定は中東における国家の創設に影響を与えたが、これらの国家の実際の国境は、その後のパワーバランス、外交交渉、第一次世界大戦後に発展した地政学的現実によって決定された。サイクス・ピコ協定の結果は、戦後フランスとイギリスに与えられた国際連盟の委任統治に反映され、いくつかの近代中東国家の形成につながった。しかし、国境が引かれ、決定されたことは、しばしば現地の民族的、宗教的現実を無視するものであり、この地域に将来の紛争と緊張の種をまいた。この協定の遺産は、現代の中東でも議論と不満の対象であり続け、外国勢力による介入と分裂を象徴している。

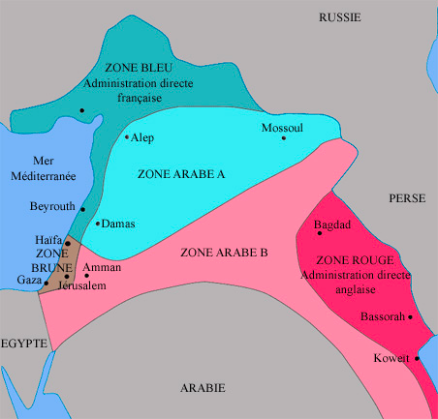

この地図は、1916年にフランスとイギリスの間で結ばれたサイクス・ピコ協定で定められたオスマン帝国の領土分割を、直接統治地域と影響力地域に分けて示したものである。

フランスの直接統治を示す「ブルーゾーン」は、後にシリアとレバノンとなる地域をカバーしていた。これは、フランスが戦略的な都市と沿岸地域を直接支配するつもりだったことを示している。イギリスの直接統治下にある「レッドゾーン」は、バグダッドやバスラといった主要都市を擁する将来のイラクと、分離された形で代表されたクウェートを包含していた。この地帯は、産油地域へのイギリスの関心と、ペルシャ湾への玄関口としての戦略的重要性を反映していた。パレスチナ(ハイファ、エルサレム、ガザなどを含む)を代表する「ブラウン・ゾーン」は、サイクス・ピコ協定では直接的な支配という点では明確に定義されていないが、一般的にはイギリスの影響力と関連している。後にイギリスの委任統治領となり、バルフォア宣言とシオニスト運動の結果、政治的緊張と対立の焦点となった。

アラブ地域A」と「アラブ地域B」は、それぞれフランスとイギリスの監督下でアラブの自治が認められた地域である。これは、戦時中に連合国がオスマン帝国に対するアラブの支持を獲得するために奨励した、ある種の自治や独立を求めるアラブの願望に対する譲歩と解釈された。この地図が示していないのは、連合国が戦時中に行った複雑で複数の約束であり、それらはしばしば矛盾していたため、合意が明らかになった後に地元住民の間に裏切られたという感情が生まれた。この地図はサイクス・ピコ協定を単純化したもので、実際はもっと複雑で、政治的発展や紛争、国際的圧力の結果、時とともに変化していった。

1917年のロシア革命後、ロシアのボリシェヴィキがサイクス・ピコ協定を暴露したことは、中東地域だけでなく、国際的にも大きな衝撃を与えた。ボリシェヴィキはこれらの密約を暴露することで、西欧列強、特にフランスとイギリスの帝国主義を批判し、自決と透明性の原則に対する自らのコミットメントを示そうとした。サイクス・ピコ協定は、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけてヨーロッパ列強を悩ませてきた複雑な外交問題である「東洋問題」の長いプロセスの始まりではなく、むしろ集大成であった。このプロセスは、衰退しつつあったオスマン帝国の領土に対する影響力の管理と共有に関わるものであり、サイクス=ピコ協定はこのプロセスにおける決定的な一歩であった。

この協定の下で、フランスはシリアとレバノンに勢力圏を確立し、イギリスはイラク、ヨルダン、パレスチナ周辺地域の支配権または影響力を獲得した。その意図は、大国の勢力圏の間に緩衝地帯を作ることであり、この地域で競合する利害を持つイギリスとロシアの間にもあった。このような構成は、インドやその他の地域での競争によって示された、これらの大国間の共存の難しさへの対応でもあった。サイクス・ピコ協定の公表はアラブ世界で強い反発を招き、戦争中にアラブの指導者たちと交わした約束に対する裏切りとみなされた。この暴露は欧米列強に対する不信感を悪化させ、この地域の民族主義的、反帝国主義的願望を煽った。中東の近代的な国境と、この地域に影響を与え続ける政治力学の基礎を築いたのである。

=アルメニア人虐殺

歴史的背景とジェノサイドの始まり(1915-1917年)

第一次世界大戦は、激しい紛争と政治的動乱の時代であったが、20世紀初頭の最も悲劇的な出来事の一つであるアルメニア人大虐殺によっても特徴づけられた。この大虐殺は1915年から1917年の間にオスマン帝国の青年トルコ政府によって行われたが、暴力行為や国外追放はそれ以前から始まり、それ以降も続いた。

この悲劇的な時期に、オスマン帝国の少数キリスト教民族であるアルメニア人は、強制追放、大量処刑、死の行進、計画的飢饉などのキャンペーンによって組織的に標的にされた。オスマン帝国当局は、「アルメニア人問題」と見なされるものを解決するための隠れ蓑と口実として戦争を利用し、アナトリアと帝国の他の地域からアルメニア人を排除する目的で、これらの行動を組織化した。犠牲者数の見積もりはさまざまだが、最大150万人のアルメニア人が死亡したと広く受け入れられている。アルメニア人虐殺は、アルメニア人の集団的記憶に深い足跡を残し、世界のアルメニア人コミュニティに永続的な影響を与えた。それは最初の近代的大量虐殺のひとつとされ、1世紀以上にわたってトルコとアルメニアの関係に影を落とした。

アルメニア人大虐殺の認定は、依然として微妙で議論の多い問題である。多くの国や国際機関がジェノサイドを公式に承認しているが、特にジェノサイドとすることに異議を唱えているトルコとの間では、一定の議論や外交的緊張が続いている。アルメニア人虐殺は国際法にも影響を及ぼし、ジェノサイドの概念の発展に影響を与え、将来的にこのような残虐行為を防止するための努力を促すことになった。この沈痛な出来事は、理解と和解に基づく共通の未来を築く上で、歴史的記憶と過去の不正義を認識することの重要性を強調している。

アルメニアの歴史的ルーツ

アルメニア人の歴史は豊かで古く、キリスト教時代のはるか昔にさかのぼる。アルメニアの民族主義的伝統と神話によれば、彼らのルーツは紀元前200年、あるいはそれ以前にまでさかのぼる。このことは、アルメニア人が何千年もの間、アルメニア高原を占領してきたことを示す考古学的、歴史的証拠によって裏付けられている。歴史上のアルメニアは、しばしば上アルメニアまたは大アルメニアと呼ばれ、現代のトルコ東部、アルメニア、アゼルバイジャン、グルジア、現代のイラン、イラクの一部を含む地域に位置していた。この地域は、紀元前9世紀から6世紀にかけて栄えた古代アルメニアの前身とされるウラルトゥ王国発祥の地である。アルメニア王国は、ウラルトゥ王国の滅亡後、アケメネス朝への統合を経て、紀元前6世紀初頭に正式に成立し、承認された。紀元前1世紀、ティグラン大王の治世に最盛期を迎え、一時はカスピ海から地中海まで広がる帝国を形成するまでに拡大した。

この地域におけるアルメニア人の存在の歴史的な深さは、西暦301年にアルメニアが初めてキリスト教を国教として公式に採用したことにも示されている。アルメニア人は、侵略やさまざまな外国帝国の支配にもかかわらず、何世紀にもわたって独自の文化的・宗教的アイデンティティを維持してきた。この長い歴史は、20世紀初頭のアルメニア人大虐殺のような深刻な苦難に直面しても、時代を超えて生き延びてきた強い民族的アイデンティティを形成してきた。アルメニアの神話や歴史的記述は、時に民族主義的な精神で誇張されることもあるが、アルメニア人の文化的豊かさと回復力に貢献してきた現実の重要な歴史に基づいている。

最初のキリスト教国家アルメニア

アルメニアは、キリスト教を国教として公式に採用した最初の王国という歴史的な称号を持っている。この記念すべき出来事は、ティリダテス3世の治世、西暦301年に起こったもので、アルメニア教会の初代教主となった聖グレゴリウス・イルミナトールの布教活動に大きな影響を受けた。アルメニア王国のキリスト教への改宗は、コンスタンティヌス帝の下、313年のミラノ勅令以降、キリスト教を支配的な宗教として採用し始めたローマ帝国の改宗に先行した。アルメニア人の改宗は、アルメニア人の文化的・民族的アイデンティティに大きな影響を与えた重要な過程であった。キリスト教の導入は、アルメニア教会や修道院の独特な建築を含むアルメニア文化や宗教芸術の発展につながり、5世紀初頭には聖メスロップ・マシュトッツによってアルメニア文字が創作された。このアルファベットのおかげで、聖書やその他の重要な宗教文書の翻訳を含むアルメニア文学が繁栄し、アルメニア人のキリスト教徒としてのアイデンティティが強化された。アルメニアは、しばしば競合する大帝国の国境に位置し、非キリスト教的な近隣諸国に囲まれていたため、最初のキリスト教国家としての地位は、政治的・地政学的な意味合いも持っていた。この区別は、何世紀にもわたってアルメニアの役割と歴史を形成するのに役立ち、キリスト教の歴史においても、中東とコーカサスの地域史においても、アルメニアを重要な存在にしている。

キリスト教が国教として採用された後のアルメニアの歴史は複雑で、しばしば波乱に満ちていた。数世紀にわたる近隣の帝国との紛争や相対的な自治の時代を経て、アルメニア人は7世紀のアラブ征服によって大きな変化を経験した。

預言者モハメッドの死後、イスラム教が急速に広まり、アラブ軍は西暦640年頃、アルメニアの大部分を含む中東の広大な地域を征服した。この時期、アルメニアはビザンチンの影響とアラブのカリフとの間に分断され、アルメニア地域の文化的・政治的分裂を招いた。アラブ支配の時代、そしてその後のオスマン帝国の時代、アルメニア人はキリスト教徒として、一般的に「ディミー」(イスラム法の下で保護されるが劣等な非ムスリムのカテゴリー)に分類された。この地位は彼らに一定の保護を与え、宗教を実践することを許したが、特定の税金や社会的・法的な制限も課された。歴史的アルメニアの大部分は、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけてオスマン帝国とロシア帝国の間に挟まれた。この時期、アルメニア人は自分たちの文化的・宗教的アイデンティティを守ろうと努める一方で、政治的課題の増大に直面した。

スルタン・アブデュルハミド2世の治世下(19世紀後半)、オスマン帝国は汎イスラム主義政策を採用し、オスマン帝国の力の衰退と内外の圧力に対応するため、帝国内の多様なイスラム民族を統合しようとした。この政策はしばしば帝国内の民族的・宗教的緊張を悪化させ、アルメニア人や他の非イスラム集団に対する暴力につながった。数万人のアルメニア人が殺害された19世紀末のハミディアンの虐殺は、1915年のアルメニア人虐殺に先行し、その伏線となった暴力の悲劇的な例である。これらの出来事は、ナショナリズムの台頭と帝国の衰退に直面し、政治的・宗教的統一を求める帝国において、アルメニア人やその他の少数民族が直面した困難を浮き彫りにした。

サン=ステファノ条約とベルリン会議

1878年に調印されたサン=ステファノ条約は、国際的な関心事となったアルメニア問題にとって極めて重要な出来事であった。この条約は、ロシア帝国の手によってオスマン帝国が大敗を喫した1877年から1878年にかけての露土戦争の末期に締結された。サン・ステファノ条約で最も注目すべき点のひとつは、オスマン帝国にキリスト教徒、特にアルメニア人に有利な改革を実施し、彼らの生活条件を改善することを要求した条項である。これは暗黙のうちに、アルメニア人が受けた虐待と国際的な保護の必要性を認めたものであった。しかし、条約で約束された改革の実施はほとんど効果がなかった。戦争と内圧で弱体化したオスマン帝国は、外国による内政干渉と受け取られかねない譲歩を認めたがらなかった。さらに、サン=ステファノ条約の条項は同年末のベルリン会議によって見直され、イギリスやオーストリア=ハンガリーをはじめとする他の大国の懸念に応える形で調整された。

それでもベルリン会議はオスマン帝国に改革を求める圧力をかけ続けたが、実際にはアルメニア人の状況を改善することはほとんどできなかった。このような行動の欠如は、帝国内の政治的不安定と民族的緊張の高まりと相まって、最終的には1890年代のハミディアンの虐殺、そして後の1915年のアルメニア人大虐殺へとつながる環境を作り出した。サン・ステファノ条約によるアルメニア問題の国際化は、ヨーロッパ列強がキリスト教少数派の保護を名目に、オスマン帝国により直接的な影響力を行使し始めた時代の幕開けとなった。しかし、改革の約束とその実行の間のギャップは、アルメニア人に悲劇的な結末をもたらす、果たされなかった約束の遺産を残した。

19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけては、オスマン帝国のアルメニア人とアッシリア人の共同体にとって、大きな暴力の時代であった。特に1895年と1896年は、スルタン・アブデュルハミド2世にちなんでハミディアンの虐殺と呼ばれる大規模な虐殺が行われた。これらの虐殺は、抑圧的な税金、迫害、サンステファノ条約で約束された改革の欠如に対するアルメニア人の抗議に対応して実行された。1908年のクーデターで政権を握った改革派民族主義運動である青年トルコ人は、当初オスマン帝国内の少数民族の希望の源とみなされていた。しかし、この運動の急進派は、結局、前任者たちよりもさらに攻撃的で民族主義的な政策を採用した。均質なトルコ国家を建設する必要性を確信した彼らは、アルメニア人やその他の非トルコ系少数民族を国家構想の障害物とみなした。アルメニア人に対する組織的な差別が強まり、反逆罪や帝国の敵、特にロシアとの共謀に対する非難が煽られた。この疑惑と憎悪の雰囲気が、1915年に始まった大量虐殺の温床となった。この大量虐殺キャンペーンの最初の行為のひとつが、1915年4月24日にコンスタンチノープルで行われたアルメニア人知識人と指導者の逮捕と殺害であった。

集団追放、シリアの砂漠への死の行進、虐殺が続き、殺害されたアルメニア人は150万人にのぼると推定されている。死の行進に加え、黒海で意図的に沈められた船にアルメニア人が強制的に乗せられたという報告もある。こうした恐怖に直面し、生き延びるためにイスラム教に改宗したアルメニア人もいれば、身を隠したり、クルド人など同情的な隣人に保護されたアルメニア人もいた。同じ頃、アッシリア人も1914年から1920年にかけて同様の残虐行為に苦しんでいた。オスマン帝国に認められたミレット(自治共同体)として、アッシリア人はある程度の保護を享受していたはずだった。しかし、第一次世界大戦とトルコのナショナリズムの中で、彼らは組織的な絶滅作戦の対象となった。これらの悲劇的な出来事は、差別、非人間化、過激主義がいかに集団暴力行為につながるかを示している。アルメニア人虐殺とアッシリア人虐殺は、このような残虐行為が二度と起こらないようにするために、追悼、認識、虐殺防止の重要性を強調する歴史の暗黒の章である。

トルコ共和国とジェノサイドの否定へ向けて

1919年、連合国によるイスタンブールの占領と、戦争中に行われた残虐行為に責任を負うオスマン・トルコ政府高官を裁くための軍法会議の設置は、特にアルメニア人虐殺をはじめとする犯罪に正義をもたらす試みであった。しかし、アナトリアの情勢は不安定で複雑なままだった。ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクに率いられたトルコの民族主義運動は、オスマン帝国を解体し、トルコに厳しい制裁を課した1920年のセーヴル条約の条項を受けて急速に発展した。ケマル派はこの条約を屈辱であり、トルコの主権と領土保全に対する脅威であるとして拒否した。

条約によって保護されていたトルコ国内のギリシア正教徒が、ギリシアとトルコの対立に巻き込まれたのである。1919年から1922年にかけてのギリシャとトルコの戦争によって、ギリシャ系住民とトルコ系住民の間の緊張は大規模な暴力と人口交換に発展した。第一次世界大戦中、ダーダネルス海峡の防衛者として名を馳せたムスタファ・ケマルは、青年トルコの有力メンバーであったが、アルメニア人虐殺を「恥ずべき行為」と述べたと引用されることがある。しかし、こうした主張には論争や歴史的な議論がつきまとう。大虐殺に関するケマルと新生トルコ共和国の公式見解は、大虐殺を否定し、意図的な絶滅政策ではなく、戦時状況や内乱によるものだとするものだった。

アナトリアへの抵抗とトルコ共和国樹立の闘争の間、ムスタファ・ケマルとその支持者たちは、統一されたトルコの国民国家を建設することに集中し、この国家プロジェクトを分裂させたり弱体化させたりしたかもしれない過去の出来事を認めることは避けられた。それゆえ、第一次世界大戦後の時期は、大きな政治的変化、紛争後の正義の試み、そしてこの地域における新たな国民国家の出現によって特徴づけられ、新生トルコ共和国はオスマン帝国の遺産から独立して独自のアイデンティティと政治を定義しようとした。

トルコの建国

ローザンヌ条約と新しい政治的現実(1923年)

1923年7月24日に調印されたローザンヌ条約は、トルコと中東の現代史において決定的な転換点となった。主にムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルク率いるトルコ国民の抵抗によるセーブル条約の失敗後、連合国は再交渉を余儀なくされた。戦争で疲弊し、領土保全に固執するトルコの現実に直面した連合国は、トルコの民族主義者たちによって確立された新たな政治的現実を認めざるを得なかった。ローザンヌ条約は、国際的に認められた現代トルコ共和国の国境を確立し、クルド人国家の創設を規定し、アルメニア人の一定の保護を認めていたセーヴル条約の条項を取り消した。ローザンヌ条約は、クルド人国家の創設やアルメニア人に対するいかなる措置も盛り込まなかったことで、「クルド人問題」と「アルメニア人問題」に対する国際レベルでの扉を閉ざし、これらの問題は未解決のまま残された。

同時に、この条約はギリシャとトルコの間の人口交換を正式なものとし、「トルコ領土からのギリシャ人の追放」という、強制的な人口移動とアナトリアとトラキアにおける歴史的共同体の終焉という痛ましいエピソードにつながった。ローザンヌ条約調印後、第一次世界大戦中に政権を握っていた青年トルコ人として知られる連合進歩委員会(CUP)は正式に解散した。その指導者の何人かは亡命し、何人かはアルメニア人虐殺や戦争の破壊的政策に関与したことへの報復として暗殺された。

その後の数年間で、トルコ共和国は統合され、アナトリアの主権と完全性を守ることを目的とした民族主義団体がいくつか生まれた。宗教はナショナル・アイデンティティの構築に一役買い、「キリスト教西側」と「イスラム教アナトリア」の区別がしばしば描かれた。この言説は、国家の結束を強化し、トルコ国家への脅威とみなされる外国の影響や介入に対する抵抗を正当化するために用いられた。それゆえ、ローザンヌ条約は現代トルコ共和国の礎石とみなされており、その遺産はトルコの国内政策や外交政策、近隣諸国や国境内の少数民族との関係を形成し続けている。

ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの到着とトルコ民族抵抗運動(1919年)

1919年5月、ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクがアナトリアに到着したことは、トルコの独立と主権を求める闘いの新たな局面の始まりを意味した。連合国の占領とセーヴル条約に反対した彼は、トルコ民族抵抗運動の指導者としての地位を確立した。その後の数年間、ムスタファ・ケマルはいくつかの重要な軍事作戦を指揮した。1921年のアルメニア人との戦い、国境を再定義するための南アナトリアでのフランスとの戦い、1919年にイズミル市を占領し西アナトリアに進出してきたギリシャ人との戦いなどである。これらの紛争は、オスマン帝国の廃墟に新しい国家を樹立しようとするトルコの民族主義運動の重要な要素であった。この地域におけるイギリスの戦略は複雑だった。一方ではギリシア人とトルコ人、他方ではトルコ人とイギリス人の対立が拡大する可能性に直面したイギリスは、ギリシア人とトルコ人を互いに戦わせることで、特に石油が豊富で戦略的に重要な領土であるイラクなど、他の場所に努力を集中させることができるという利点を考えた。

ギリシャ・トルコ戦争は1922年、トルコの勝利とギリシャのアナトリアからの撤退で頂点に達し、ギリシャにとっては小アジアの大惨事となり、トルコ民族主義勢力にとっては大勝利となった。ムスタファ・ケマルによる軍事作戦の勝利により、セーヴル条約の再交渉が可能となり、1923年にはトルコ共和国の主権を認め、国境を再定義するローザンヌ条約が締結された。ローザンヌ条約と同時に、ギリシャとトルコの人口交換条約が締結された。これにより、ギリシャ正教徒とトルコ系イスラム教徒が両国の間で強制的に交換され、より民族的に均質な国家を目指すことになった。フランス軍を撃退し、国境協定を締結し、ローザンヌ条約に調印した後、ムスタファ・ケマルは1923年10月29日にトルコ共和国を宣言し、初代大統領に就任した。共和国宣言は、多民族・多宗教国家であったオスマン帝国の残滓の上に、近代的で世俗的かつ民族主義的なトルコ国家を建設しようとしたムスタファ・ケマルの努力の集大成であった。

国境の形成とモスルとアンティオキア問題

1923年にローザンヌ条約が締結され、トルコ共和国が国際的に承認され、国境が再定義された後も、特にアンティオキアとモスル地域に関する未解決の国境問題が残っていた。これらの問題を解決するためには、さらなる交渉と国際機関の介入が必要であった。アンティオキア市は、歴史的に豊かで文化的に多様なアナトリア南部に位置し、アンティオキアを含むシリアの委任統治権を行使していたトルコとフランスの間で争いの対象となっていた。多文化的な過去と戦略的重要性を持つこの都市は、両国の緊張の的だった。結局、交渉の末、アンティオキアはトルコに与えられたが、この決定は論争と緊張の種となった。モスル地域の問題はさらに複雑だった。石油が豊富なモスル地域は、トルコとイラクを委任統治していたイギリスの両方が領有権を主張していた。トルコは、歴史的、人口学的な論拠に基づいて、モスル地域を自国の国境に含めたいと考え、イギリスは、戦略的、経済的な理由、特に石油の存在から、モスル地域をイラクに含めることを支持した。

この紛争を解決するため、国際連合の前身である国際連盟が介入した。交渉の末、1925年に合意に達した。この協定では、モスル地域はイラクの一部となるが、トルコは特に石油収入の分配という形で金銭的補償を受けることになった。この協定には、トルコがイラクとその国境を公式に承認することも定められていた。この決定は、トルコ、イラク、イギリス間の関係を安定させる上で極めて重要であり、イラクの国境を定義する上で重要な役割を果たし、中東の将来の発展に影響を与えた。これらの交渉とその結果としての合意は、中東における第一次世界大戦後の力学の複雑さを物語っている。この地域の近代的な国境が、歴史的な主張、戦略的・経済的な考慮、国際的な介入などが入り混じって形成され、しばしば地元住民の利益よりも植民地支配国の利益を反映したものであったことを示している。

ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの急進的改革

第一次世界大戦後のトルコは、新トルコ共和国の近代化と世俗化を目指したムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクによる急進的な改革と変革によって特徴づけられる。1922年、トルコ議会がオスマン・トルコのスルタン制を廃止するという重要な一歩を踏み出し、数世紀にわたる帝国支配に終止符を打ち、トルコの新首都アンカラに政治権力を集中させた。1924年には、カリフ制の廃止というもうひとつの大きな改革が行われた。この決定により、オスマン帝国の特徴であったイスラム教の宗教的・政治的指導力が排除され、国家の世俗化への決定的な一歩となった。この廃止と並行して、トルコ政府は、国内の宗教問題を監督・規制するための機関であるディヤネット(宗教問題大統領府)を創設した。この組織の目的は、宗教問題を国家の管理下に置き、宗教が政治的目的のために利用されないようにすることだった。その後、ムスタファ・ケマルは、しばしば「権威主義的近代化」と呼ばれる、トルコの近代化を目指した一連の改革を実施した。これらの改革には、教育の世俗化、服装規定の改革、グレゴリオ暦の採用、イスラム宗教法に代わる民法の導入などが含まれた。

均質なトルコ国民国家を作る一環として、少数民族や異なる民族グループに対する同化政策が実施された。これらの政策には、すべての国民にトルコ姓を名乗らせること、トルコ語とトルコ文化を採用するよう奨励すること、宗教学校を閉鎖することなどが含まれた。これらの施策は、トルコ人という共通のアイデンティティのもとに国民を統一することを目指したが、同時に少数民族の文化的権利や自治の問題も提起した。これらの急進的な改革はトルコ社会を変革し、近代トルコの基礎を築いた。ムスタファ・ケマルの、近代的で世俗的で単一的な国家を作りたいという願望を反映したものであり、同時に戦後の複雑な民族主義的願望を反映したものであった。これらの変化はトルコの歴史に大きな影響を与え、今日もトルコの政治と社会に影響を与え続けている。

1920年代から1930年代にかけてのトルコは、ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの指導の下、国の近代化と西欧化を目指した一連の急進的な改革によって特徴づけられた。これらの改革は、トルコの社会、文化、政治生活のほとんどすべての側面に影響を与えた。最初の施策のひとつが教育省の創設であり、教育制度の改革とケマル主義イデオロギーの推進において中心的な役割を果たした。1925年、最も象徴的な改革のひとつは、トルコ国民の外見と服装を近代化する政策の一環として、伝統的なフェズに代わってヨーロッパ帽を着用させたことである。

法改正も重要なもので、スイス民法をはじめとする西欧のモデルに触発された法規範が採用された。これらの改革の目的は、シャリーア(イスラム法)に基づくオスマン帝国の法制度を、近代的で世俗的な法制度に置き換えることだった。トルコはまた、メートル法とグレゴリオ暦を採用し、休息日を(イスラム教国で伝統的に守られてきた)金曜日から日曜日に変更することで、西欧の標準に合わせた。最も急進的な改革のひとつは、1928年にアルファベットをアラビア文字から修正ラテン文字に変更したことである。この改革の目的は、識字率の向上とトルコ語の近代化にあった。1931年に設立されたトルコ歴史研究所は、トルコの歴史を再解釈し、トルコの国民的アイデンティティを促進するための幅広い取り組みの一環であった。同じ精神で、トルコ語の純化政策はアラビア語やペルシャ語の借用を排除し、トルコ語とトルコ文化の古代の起源と優位性を主張する民族主義的イデオロギーである「太陽語」理論を強化することを目的としていた。

クルド人問題については、ケマル主義政府は同化政策を追求し、クルド人を「山のトルコ人」とみなし、彼らをトルコの国民的アイデンティティに統合しようとした。この政策は、特に1938年のクルド人および非イスラム系住民への弾圧において、緊張と対立を招いた。ケマリスト時代はトルコにとって大きな変革の時代であり、近代的で世俗的かつ均質な国民国家を作ろうとする努力が顕著であった。しかし、こうした改革は、近代化を目指した進歩的なものであった一方で、権威主義的な政策や同化への努力も伴っており、現代のトルコに複雑で、時に物議を醸す遺産を残している。

1923年の共和国建国から始まったトルコのケマリスト時代は、国家の中央集権化、国有化、世俗化、そして社会のヨーロッパ化を目指した一連の改革によって特徴づけられた。ムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクが主導したこれらの改革は、進歩と近代化の障害とみなされていたオスマン帝国の帝国的・イスラム的過去との決別を目指した。その目的は、西洋の価値観や基準に沿った近代的なトルコを作ることだった。このような観点から、オスマン帝国とイスラムの遺産はしばしば否定的に描かれ、後進性や蒙昧主義と結びつけられた。西側へのシフトは、政治、文化、法律、教育、そして日常生活においても顕著であった。

多党制と近代化と伝統の緊張関係(1950年以降)

しかし、1950年代に多党制が導入されると、トルコの政治状況は変わり始めた。共和国人民党(CHP)の下で一党独裁国家として運営されてきたトルコは、政治的多元主義に門戸を開き始めた。この移行に緊張がなかったわけではない。ケマル主義時代に疎外されがちだった保守派は、ケマル主義改革の一部、特に世俗主義と西欧化に関する改革に疑問を呈し始めた。世俗主義と伝統的価値観、西欧化とトルコ的・イスラム的アイデンティティの間の論争は、トルコ政治において繰り返し取り上げられるテーマとなった。保守主義政党やイスラム主義政党が台頭し、ケマル主義の遺産に疑問を呈し、特定の伝統的・宗教的価値観への回帰を訴えている。

この政治的ダイナミズムは時に弾圧や緊張を招き、さまざまな政権が多様化する政治環境の中で権力を強化しようとしている。特に1960年、1971年、1980年の軍事クーデター、そして2016年のクーデター未遂のような政治的緊張と抑圧の時期は、近代化と伝統、世俗主義と宗教性、西欧化とトルコ的アイデンティティのバランスを取るというトルコが直面した挑戦の証である。1950年以降のトルコでは、ケマリストの遺産と伝統的価値観への回帰を求める一部の国民の願望との間で、複雑かつ時に相反するバランスの再構築が見られ、現代トルコ社会における近代化と伝統の間の継続的な緊張を反映している。

トルコとその内的課題:民族と宗教の多様性の管理

西側諸国の戦略的同盟国として、特に1952年のNATO加盟以来、トルコは西側諸国との関係と自国内の政治力学を調和させなければならなかった。1950年代に導入された複数政党制は、より民主的な統治形態への移行を反映したものであり、この和解における重要な要素であった。しかし、この移行は不安定な時期や軍事介入によって特徴づけられてきた。実際、トルコは1960年、1971年、1980年、そして2016年と、およそ10年ごとに軍事クーデターを経験している。これらのクーデターは、秩序を回復し、トルコ共和国の原則、特にケマル主義と世俗主義を守るために必要であるとして、しばしば軍によって正当化された。各クーデターの後、軍は一般的に文民統治に戻すために新たな選挙を招集したが、軍はケマル主義イデオロギーの保護者としての役割を果たし続けた。

しかし、2000年代以降、トルコの政治情勢は、特に公正発展党(AKP)をはじめとする保守・イスラム主義政党の台頭によって大きく変化した。レジェップ・タイイップ・エルドアン率いるAKPは、いくつかの選挙で勝利し、長期にわたって政権を維持した。AKP政権は、より保守的でイスラム的な価値観を標榜しているにもかかわらず、軍によって打倒されたことはない。これは、ケマル主義の原則から逸脱しているとみなされた政権がしばしば軍事介入の対象となった過去数十年とは異なることを意味する。トルコの保守政権が相対的に安定していることは、軍と民間の政党間の力の均衡が崩れていることを示唆している。この背景には、軍の政治力を削ぐことを目的とした一連の改革と、保守的でイスラム的な価値観を反映した統治をますます受け入れるようになったトルコ国民の態度の変化がある。現代トルコの政治力学は、世俗的なケマリスト主義の伝統と、保守的でイスラム主義的な傾向の高まりの間を行き来しながら、複数政党主義と西側諸国との同盟へのコミットメントを維持している国の課題を反映している。

現代のトルコは、民族的・宗教的多様性の管理など、さまざまな内的課題に直面してきた。特にクルド人に対する同化政策は、トルコのナショナリズムを強化する上で重要な役割を果たしてきた。このような状況は、特にオスマン帝国下で特定の宗教的少数派に与えられたミレット(自治共同体)の地位の恩恵を受けていない少数派クルド人との緊張や対立につながっている。20世紀におけるヨーロッパの反ユダヤ主義や人種差別主義の影響もトルコに及んだ。1930年代、ヨーロッパの政治的・社会的潮流の影響を受けた差別的・排外主義的な思想がトルコにも現れ始めた。このため、1934年にトラキアでユダヤ人に対するポグロムが発生し、ユダヤ人社会が標的となり、攻撃され、避難を余儀なくされるなど、悲劇的な出来事が起こった。

さらに、1942年に導入された富裕税法(Varlık Vergisi)も、ユダヤ人、アルメニア人、ギリシア人など、トルコ人やイスラム教徒以外の少数民族に主に影響を与えた差別的措置であった。この法律は、非イスラム教徒に不釣り合いなほど高い法外な税金を富に課し、払えない者は、特にトルコ東部のアシュカレの労働収容所に送られた。これらの政策や出来事は、トルコ社会における民族的・宗教的緊張を反映したものであり、トルコのナショナリズムが時に排他的・差別的に解釈された時代でもあった。また、多数の民族や宗教集団が共存するアナトリアのような多様な地域で国民国家が形成される過程の複雑さを浮き彫りにした。この時期のトルコにおける少数民族の扱いは、国内の多様性を管理しながら統一された国民的アイデンティティを模索するトルコが直面した課題を反映し、今でも繊細で論争の的となっている。これらの出来事は、トルコの異なる民族・宗教間の関係にも長期的な影響を与えた。

世俗主義と世俗主義の分離:ケマリスト時代の遺産

世俗化と世俗主義の区別は、異なる歴史的・地理的文脈における社会的・政治的力学を理解する上で重要である。世俗化とは、社会、制度、個人が宗教的影響や規範から離れ始める歴史的・文化的プロセスを指す。世俗化された社会では、宗教が公共生活、法律、教育、政治、その他の分野に対する影響力を徐々に失っていく。このプロセスは、必ずしも個人が個人レベルで宗教的でなくなることを意味するのではなく、むしろ宗教が公的な問題や国家から切り離された私的な問題となることを意味する。世俗化は多くの場合、近代化、科学技術の発展、社会規範の変化と関連している。一方、世俗主義とは、国家が宗教問題に関して中立であることを宣言する制度的・法的政策である。国家を宗教機関から切り離し、政府の決定や公共政策が特定の宗教教義に影響されないようにする決定である。世俗主義は、深い宗教社会と共存することが可能である。理論的には、世俗主義は信教の自由を保障し、すべての宗教を平等に扱い、特定の宗教を優遇することを避けることを目的としている。

歴史的、現代的な例を見ると、この2つの概念の組み合わせはさまざまである。例えば、ヨーロッパ諸国の中には、国家と特定の教会との公式な結びつきを維持しながら、大幅な世俗化を行った国もある(イギリスとイングランド国教会など)。一方、フランスのように厳格な世俗主義(ライシテ)を採用しながらも、歴史的に宗教的伝統が色濃く残っている国もある。トルコでは、ケマル主義の時代にモスクと国家の分離という厳格な世俗主義が導入されたが、一方でイスラム教が人々の私生活において重要な役割を果たし続けた社会でもあった。ケマリストの世俗主義政策は、西欧のモデルからインスピレーションを得ながら、イスラム教を中心とした社会的・政治的組織の長い歴史を持つ社会の複雑な背景を乗り越え、トルコの近代化と統一を目指した。

第二次世界大戦後のトルコでは、特に少数民族に影響を及ぼし、国内の民族的・宗教的緊張を悪化させる事件が頻発した。その中でも、1955年にテッサロニキ(当時ギリシャ)にあったムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクの生家が爆破された事件は、トルコ近代史における最も悲劇的な出来事のひとつ、イスタンブール・ポグロムのきっかけとなった。イスタンブール・ポグロムは、1955年9月6日から7日にかけての事件としても知られ、主に市内のギリシャ人コミュニティに対するものであったが、アルメニア人やユダヤ人をはじめとする他の少数民族に対しても行われた一連の暴力的な襲撃事件であった。これらの攻撃は、アタテュルクの生家が爆破されるという噂に端を発し、ナショナリストや反マイノリティの感情によって悪化した。暴動は大規模な財産の破壊、暴力、多くの人々の避難という結果をもたらした。

この出来事はトルコにおけるマイノリティの歴史の転換点となり、イスタンブールのギリシャ人人口は大幅に減少し、他のマイノリティの間では全般的な不安感が広がった。イスタンブールのポグロムはまた、国民的アイデンティティ、民族的・宗教的多様性、多様な国民国家における調和の維持という課題をめぐるトルコ社会の根底にある緊張を明らかにした。それ以来、トルコにおける民族的・宗教的マイノリティの割合は、移住や同化政策、時には共同体間の緊張や対立など、さまざまな要因によって大幅に減少してきた。現代のトルコは寛容で多様性のある社会というイメージを広めようとしているが、このような歴史的事件の遺産は、異なるコミュニティ間の関係や、少数民族に対する国の政策に影響を与え続けている。トルコにおける少数民族の状況は、多様性を管理し、国境内のすべての共同体の権利と安全を守る上で、多くの国家が直面している課題を示しており、依然として微妙な問題である。

The Alevis

The Impact of the Foundation of the Republic of Turkey on the Alevis (1923)

The creation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 and the secularist reforms initiated by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had a significant impact on various religious and ethnic groups in Turkey, including the Alevi community. The Alevis, a distinct religious and cultural group within Islam, practising a form of belief that differs from mainstream Sunnism, greeted the founding of the Turkish Republic with a degree of optimism. The promise of secularism and secularisation offered the hope of greater equality and religious freedom, compared with the period of the Ottoman Empire when they had often been the subject of discrimination and sometimes violence.

However, with the creation of the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) after the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924, the Turkish government sought to regulate and control religious affairs. Although the Diyanet was designed to exercise state control over religion and promote an Islam compatible with republican and secular values, in practice it has often favoured Sunni Islam, which is the majority branch in Turkey. This policy has caused problems for the Alevi community, who have felt marginalised by the state's promotion of a form of Islam that does not correspond to their religious beliefs and practices. Although the situation of Alevis under the Turkish Republic was much better than under the Ottoman Empire, where they were frequently persecuted, they continued to face challenges regarding their religious recognition and rights.

Over the years, Alevis have fought for official recognition of their places of worship (cemevis) and for fair representation in religious affairs. Despite the progress made in terms of secularism and civil rights in Turkey, the Alevi question remains an important issue, reflecting Turkey's wider challenges in managing its religious and ethnic diversity within a secular framework. The situation of the Alevis in Turkey is therefore an example of the complex relationship between the state, religion and minorities in a context of modernisation and secularisation, illustrating how state policies can influence social and religious dynamics within a nation.

Alevi Political Engagement in the 1960s

In the 1960s, Turkey experienced a period of significant political and social change, with the emergence of various political parties and movements representing a range of views and interests. It was a time of political dynamism, marked by a greater expression of political identities and demands, including those of minority groups such as the Alevis. The creation of the first Alevi political party during this period was an important development, reflecting a growing willingness on the part of this community to engage in the political process and defend its specific interests. Alevis, with their distinct beliefs and practices, have often sought to promote greater recognition and respect for their religious and cultural rights. However, it is also true that other political parties, particularly those of the left or communist persuasion, have responded to the demands of the Kurdish and Alevi electorate. By promoting ideas of social justice, equality and minority rights, these parties have attracted significant support from these communities. Issues of minority rights, social justice and secularism were often at the heart of their political platforms, which resonated with the concerns of Alevis and Kurds.

In the context of 1960s Turkey, marked by growing political tension and ideological divides, left-wing parties were often seen as champions of the underclass, minorities and marginalised groups. This led to a situation where Alevi political parties, although directly representing this community, were sometimes overshadowed by broader, more established parties addressing broader issues of social justice and equality. Thus, Turkish politics in this period reflected a growing diversity and complexity of political identities and affiliations, illustrating how issues of minority rights, social justice and identity played a central role in Turkey's emerging political landscape.

Alevis Facing Extremism and Violence in the 1970s and 1980s

The 1970s were a period of great social and political tension in Turkey, marked by increasing polarisation and the emergence of extremist groups. During this period, the far right in Turkey, represented in part by nationalist and ultranationalist groups, gained in visibility and influence. This rise in extremism has had tragic consequences, particularly for minority communities such as the Alevis. Alevis, because of their beliefs and practices distinct from the majority Sunni Islam, have often been targeted by ultra-nationalist and conservative groups. These groups, fuelled by nationalist and sometimes sectarian ideologies, have carried out violent attacks against Alevi communities, including massacres and pogroms. The most notorious incidents include the massacres at Maraş in 1978 and Çorum in 1980. These events were characterised by extreme violence, mass murder, and other atrocities, including scenes of beheading and mutilation. These attacks were not isolated incidents, but part of a wider trend of violence and discrimination against Alevis, which exacerbated social divisions and tensions in Turkey.

The violence of the 1970s and early 1980s contributed to the instability that led to the military coup of 1980. Following the coup, the army established a regime that cracked down on many political groups, including the far right and the far left, in an attempt to restore order and stability. However, the underlying problems of discrimination and tension between different communities have remained, posing ongoing challenges to Turkey's social and political cohesion. The situation of the Alevis in Turkey is therefore a poignant example of the difficulties faced by religious and ethnic minorities in a context of political polarisation and rising extremism. It also highlights the need for an inclusive approach that respects the rights of all communities in order to maintain social peace and national unity.

The Tragedies of Sivas and Gazi in the 1990s

The 1990s in Turkey continued to witness tensions and violence, particularly against the Alevi community, which was the target of several tragic attacks. In 1993, a particularly shocking event occurred in Sivas, a town in central Turkey. On 2 July 1993, during the Pir Sultan Abdal cultural festival, a group of Alevi intellectuals, artists and writers, as well as spectators, were attacked by an extremist mob. The Madımak Hotel, where they were staying, was set on fire, resulting in the deaths of 37 people. This incident, known as the Sivas massacre or Madımak tragedy, was one of the darkest events in modern Turkish history and highlighted the vulnerability of Alevis to extremism and religious intolerance. Two years later, in 1995, another violent incident took place in the Gazi district of Istanbul, an area with a large Alevi population. Violent clashes broke out after an unknown gunman fired on cafés frequented by Alevis, killing one person and injuring several others. The following days were marked by riots and clashes with the police, which led to many more casualties.

These incidents exacerbated tensions between the Alevi community and the Turkish state, and highlighted the persistence of prejudice and discrimination against Alevis. They also raised questions about the protection of minorities in Turkey and the State's ability to ensure security and justice for all its citizens. The violence in Sivas and Gazi marked a turning point in awareness of the situation of Alevis in Turkey, leading to stronger calls for recognition of their rights and for greater understanding and respect for their unique cultural and religious identity. These tragic events remain etched in Turkey's collective memory, symbolising the challenges the country faces in terms of religious diversity and peaceful coexistence.

Alevis under the AKP: Identity Challenges and Conflicts

Since the Justice and Development Party (AKP), led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, came to power in 2002, Turkey has seen significant changes in its policy towards Islam and religious minorities, including the Alevi community. The AKP, often perceived as a party with Islamist or conservative leanings, has been criticised for favouring Sunni Islam, raising concerns among religious minorities, particularly the Alevis. Under the AKP, the government strengthened the role of the Diyanet (Presidency of Religious Affairs), which was accused of promoting a Sunni version of Islam. This has caused problems for the Alevi community, which practises a form of Islam that is markedly different from the dominant Sunnism. Alevis do not go to traditional mosques to worship; instead, they use "cemevi" for their religious ceremonies and gatherings. However, the Diyanet does not officially recognise cemevi as places of worship, which has been a source of frustration and conflict for the Alevis. The issue of assimilation is also of concern to Alevis, as the government has been perceived as seeking to integrate all religious and ethnic communities into a homogenous Sunni Turkish identity. This policy is reminiscent of the assimilation efforts of the Kemalist era, although the motivations and contexts are different.

The Alevis are an ethnically and linguistically diverse group, with both Turkish-speaking and Kurdish-speaking members. Although their identity is largely defined by their distinct faith, they also share cultural and linguistic aspects with other Turks and Kurds. However, their unique religious practice and history of marginalisation sets them apart within Turkish society. The situation of the Alevis in Turkey since 2002 reflects the continuing tensions between the State and religious minorities. It raises important questions about religious freedom, minority rights and the state's ability to accommodate diversity within a secular and democratic framework. How Turkey manages these issues remains a crucial aspect of its domestic policy and its image on the international stage.

Iran

Challenges and External Influences at the Beginning of the 20th Century

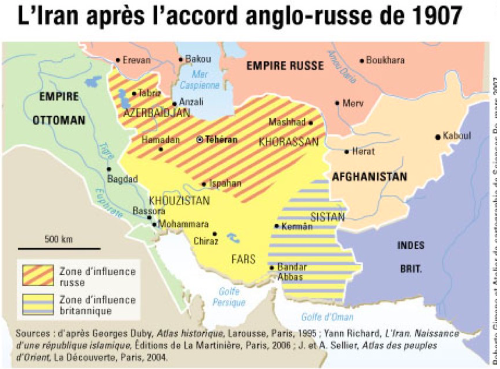

The history of modernisation in Iran is a fascinating case study that illustrates how external influences and internal dynamics can shape a country's course. In the early 20th century, Iran (then known as Persia) faced multiple challenges that culminated in a process of authoritarian modernisation. In the years leading up to the First World War, particularly in 1907, Iran was on the verge of implosion. The country had suffered significant territorial losses and was struggling with administrative and military weakness. The Iranian army, in particular, was unable to effectively manage the influence of the state or protect its borders from foreign incursions. This difficult context was exacerbated by the competing interests of the imperialist powers, particularly Britain and Russia. In 1907, despite their historical rivalries, Great Britain and Russia concluded the Anglo-Russian Entente. Under this agreement, they shared spheres of influence in Iran, with Russia dominating the north and Britain the south. This agreement was a tacit recognition of their respective imperialist interests in the region and had a profound impact on Iranian policy.

The Anglo-Russian Entente not only limited Iran's sovereignty, but also hindered the development of a strong central power. Britain, in particular, was reticent about the idea of a centralised and powerful Iran that could threaten its interests, particularly in terms of access to oil and control of trade routes. This international framework posed major challenges for Iran and influenced its path towards modernisation. The need to navigate between foreign imperialist interests and domestic needs to reform and strengthen the state led to a series of attempts at modernisation, some more authoritarian than others, over the course of the 20th century. These efforts culminated in the period of the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, who undertook an ambitious programme of modernisation and centralisation, often by authoritarian means, with the aim of transforming Iran into a modern nation-state.

The coup of 1921 and the rise of Reza Khan

The 1921 coup in Iran, led by Reza Khan (later Reza Shah Pahlavi), was a decisive turning point in the country's modern history. Reza Khan, a military officer, took control of the government in a context of political weakness and instability, with the ambition of centralising power and modernising Iran. After the coup, Reza Khan undertook a series of reforms aimed at strengthening the state and consolidating his power. He created a centralised government, reorganised the administration and modernised the army. These reforms were essential to establish a strong and effective state structure capable of promoting the country's development and modernisation. A key aspect of Reza Khan's consolidation of power was the negotiation of agreements with foreign powers, notably Great Britain, which had major economic and strategic interests in Iran. The issue of oil was particularly crucial, as Iran had considerable oil potential, and control and exploitation of this resource were at the heart of the geopolitical stakes.

Reza Khan successfully navigated these complex waters, striking a balance between cooperating with foreign powers and protecting Iranian sovereignty. Although he had to make concessions, particularly on oil exploitation, his government worked to ensure that Iran received a fairer share of oil revenues and to limit direct foreign influence in the country's internal affairs. In 1925, Reza Khan was crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi, becoming the first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty. Under his reign, Iran underwent radical transformations, including modernisation of the economy, educational reform, westernisation of social and cultural norms, and a policy of industrialisation. These reforms, although often carried out in an authoritarian manner, marked Iran's entry into the modern era and laid the foundations for the country's subsequent development.

The era of Reza Shah Pahlavi: Modernisation and Centralisation

The advent of Reza Shah Pahlavi in Iran in 1925 marked a radical change in the country's political and social landscape. After the fall of the Kadjar dynasty, Reza Shah, inspired by the reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey, initiated a series of far-reaching transformations aimed at modernising Iran and forging it into a powerful, centralised nation-state. His reign was characterised by authoritarian modernisation, with power highly concentrated and reforms imposed top-down. The centralisation of power was a crucial step, with Reza Shah seeking to eliminate traditional intermediate powers such as tribal chiefs and local notables. This consolidation of authority was intended to strengthen the central government and ensure tighter control over the country as a whole. As part of his modernisation efforts, he also introduced the metric system, modernised transport networks with the construction of new roads and railways, and implemented cultural and dress reforms to bring Iran into line with Western standards.

Reza Shah also promoted a strong nationalism, glorifying the Persian imperial past and the Persian language. This exaltation of Iran's past was intended to create a sense of national unity and common identity among Iran's diverse population. However, these reforms came at a high cost in terms of individual freedoms. Reza Shah's regime was marked by censorship, repression of freedom of expression and political dissent, and strict control of the political apparatus. On the legislative front, modern civil and penal codes were introduced, and dress reforms were imposed to modernise the appearance of the population. Although these reforms contributed to the modernisation of Iran, they were implemented in an authoritarian manner, without any significant democratic participation, which sowed the seeds of future tensions. The Reza Shah period was therefore an era of contradictions in Iran. On the one hand, it represented a significant leap forward in the modernisation and centralisation of the country. On the other, it laid the foundations for future conflicts because of its authoritarian approach and the absence of channels for free political expression. This period was therefore decisive in Iran's modern history, shaping its political, social and economic trajectory for decades to come.

Name change: From Persia to Iran

The change of name from Persia to Iran in December 1934 is a fascinating example of how international politics and ideological influences can shape a country's national identity. Under the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi, Persia, which had been the country's historical and Western name, officially became Iran, a term that had long been used within the country and which means "land of the Aryans". The name change was partly an effort to strengthen ties with the West and to emphasise the nation's Aryan heritage, against the backdrop of the emergence of nationalist and racial ideologies in Europe. At the time, Nazi propaganda had some resonance in several Middle Eastern countries, including Iran. Reza Shah, seeking to counterbalance British and Soviet influence in Iran, saw Nazi Germany as a potential strategic ally. However, his policy of rapprochement with Germany aroused the concern of the Allies, particularly Great Britain and the Soviet Union, who feared Iranian collaboration with Nazi Germany during the Second World War.

As a result of these concerns, and Iran's strategic role as a transit route for supplies to Soviet forces, the country became a focal point in the war. In 1941, British and Soviet forces invaded Iran, forcing Reza Shah to abdicate in favour of his son, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. Mohammed Reza, still young and inexperienced, acceded to the throne against a backdrop of international tensions and foreign military presence. The Allied invasion and occupation of Iran had a profound impact on the country, hastening the end of Reza Shah's policy of neutrality and ushering in a new era in Iranian history. Under Mohammed Reza Shah, Iran would become a key ally of the West during the Cold War, although this would be accompanied by internal challenges and political tensions that would ultimately culminate in the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

Oil nationalisation and the fall of Mossadegh

The episode of the nationalisation of oil in Iran and the fall of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 constitute a crucial chapter in the history of the Middle East and reveal the power dynamics and geopolitical interests during the Cold War. In 1951, Mohammad Mossadegh, a nationalist politician elected Prime Minister, took the bold step of nationalising the Iranian oil industry, which was then controlled by the British Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC, now BP). Mossadegh considered that control of the country's natural resources, particularly oil, was essential for Iran's economic and political independence. The decision to nationalise oil was extremely popular in Iran, but it also provoked an international crisis. The UK, losing its privileged access to Iran's oil resources, sought to thwart the move by diplomatic and economic means, including imposing an oil embargo. Faced with an impasse with Iran and unable to resolve the situation by conventional means, the British government asked the United States for help. Initially reluctant, the United States was eventually persuaded, partly because of rising Cold War tensions and fears of Communist influence in Iran.

In 1953, the CIA, with the support of Britain's MI6, launched Operation Ajax, a coup that led to the removal of Mossadegh and the strengthening of the power of the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. This coup marked a decisive turning point in Iranian history, strengthening the monarchy and increasing Western influence, particularly that of the United States, in Iran. However, foreign intervention and the suppression of nationalist and democratic aspirations also created deep resentment in Iran, which would contribute to internal political tensions and, ultimately, to the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Operation Ajax is often cited as a classic example of Cold War interventionism and its long-term consequences, not just for Iran, but for the Middle East region as a whole.

The 1953 event in Iran, marked by the removal of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, was a pivotal period that had a profound impact on the country's political development. Mossadegh, although democratically elected and extremely popular for his nationalist policies, in particular the nationalisation of the Iranian oil industry, was overthrown following a coup d'état orchestrated by the American CIA and British MI6, known as Operation Ajax.

The "White Revolution" of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

After Mossadegh's departure, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi consolidated his power and became increasingly authoritarian. The Shah, supported by the United States and other Western powers, launched an ambitious programme of modernisation and development in Iran. This programme, known as the 'White Revolution', was launched in 1963 and aimed to rapidly transform Iran into a modern, industrialised nation. The Shah's reforms included land redistribution, a massive literacy campaign, economic modernisation, industrialisation and the granting of voting rights to women. These reforms were supposed to strengthen the Iranian economy, reduce dependence on oil, and improve the living conditions of Iranian citizens. However, the Shah's reign was also characterised by strict political control and repression of dissent. The Shah's secret police, the SAVAK, created with the help of the United States and Israel, was notorious for its brutality and repressive tactics. The lack of political freedoms, corruption and growing social inequality led to widespread discontent among the Iranian population. Although the Shah managed to achieve some progress in terms of modernisation and development, the lack of democratic political reform and the repression of opposition voices ultimately contributed to the alienation of large segments of Iranian society. This situation paved the way for the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which overthrew the monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Strengthening ties with the West and social impact

Since 1955, Iran, under the leadership of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, has sought to strengthen its ties with the West, particularly the United States, in the context of the Cold War. Iran's accession to the Baghdad Pact in 1955 was a key element of this strategic orientation. This pact, which also included Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan and the United Kingdom, was a military alliance aimed at containing the expansion of Soviet communism in the Middle East. As part of his rapprochement with the West, the Shah launched the "White Revolution", a set of reforms aimed at modernising Iran. These reforms, largely influenced by the American model, included changes in production and consumption patterns, land reform, a literacy campaign and initiatives to promote industrialisation and economic development. The close involvement of the United States in Iran's modernisation process was also symbolised by the presence of American experts and advisers on Iranian soil. These experts often enjoyed privileges and immunities, which gave rise to tensions within various sectors of Iranian society, particularly among religious circles and nationalists.

The Shah's reforms, while leading to economic and social modernisation, were also perceived by many as a form of Americanisation and an erosion of Iranian values and traditions. This perception was exacerbated by the authoritarian nature of the Shah's regime and the absence of political freedoms and popular participation. The American presence and influence in Iran, as well as the reforms of the "White Revolution", have fuelled growing resentment, particularly in religious circles. Religious leaders, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, began to articulate increasingly strong opposition to the Shah, criticising him for his dependence on the United States and for his departure from Islamic values. This opposition eventually played a key role in the mobilisation that led to the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

The "White Revolution" reforms in Iran, initiated by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in the 1960s, included a major land reform that had a profound impact on the country's social and economic structure. The aim of this reform was to modernise Iranian agriculture and reduce the country's dependence on oil exports, while improving the living conditions of peasants. The land reform broke with traditional practices, particularly those linked to Islam, such as offerings by imams. Instead, it favoured a market economy approach, with the aim of increasing productivity and stimulating economic development. Land was redistributed, reducing the power of the large landowners and religious elites who controlled vast tracts of agricultural land. However, this reform, along with other modernisation initiatives, was carried out in an authoritarian and top-down manner, without any meaningful consultation or participation of the population. Repression of the opposition, including left-wing and communist groups, was also a feature of the Shah's regime. The SAVAK, the Shah's secret police, was infamous for its brutal methods and extensive surveillance.

The Shah's authoritarian approach, combined with the economic and social impact of the reforms, created growing discontent among various segments of Iranian society. Shiite clerics, nationalists, communists, intellectuals and other groups found common ground in their opposition to the regime. Over time, this disparate opposition consolidated into an increasingly coordinated movement. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 can be seen as the result of this convergence of oppositions. The Shah's repression, perceived foreign influence, disruptive economic reforms and the marginalisation of traditional and religious values created fertile ground for a popular revolt. This revolution eventually overthrew the monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran, marking a radical turning point in the country's history.

The celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire in 1971, organised by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was a monumental event designed to underline the greatness and historical continuity of Iran. This lavish celebration, which took place in Persepolis, the ancient capital of the Achaemenid Empire, was intended to establish a link between the Shah's regime and the glorious imperial history of Persia. As part of his effort to strengthen Iran's national identity and highlight its historical roots, Mohammad Reza Shah made a significant change to the Iranian calendar. This change saw the Islamic calendar, which was based on the Hegira (the migration of the prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Medina), replaced by an imperial calendar that began with the founding of the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great in 559 BC.

However, this change of calendar was controversial and was seen by many as an attempt by the Shah to play down the importance of Islam in Iranian history and culture in favour of glorifying the pre-Islamic imperial past. This was part of the Shah's policies of modernisation and secularisation, but it also fuelled discontent among religious groups and those attached to Islamic traditions. A few years later, following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Iran returned to using the Islamic calendar. The revolution, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran, marking a profound rejection of the Shah's policies and style of governance, including his attempts to promote a nationalism based on Iran's pre-Islamic history. The calendar issue and the celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire are examples of how history and culture can be mobilised in politics, and how such actions can have a significant impact on the social and political dynamics of a country.

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 and its Impact

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was a landmark event in contemporary history, not only for Iran but also for global geopolitics. The revolution saw the collapse of the monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the establishment of an Islamic Republic under the leadership of Ayatollah Rouhollah Khomeini. In the years leading up to the revolution, Iran was rocked by massive demonstrations and popular unrest. These protests were motivated by a multitude of grievances against the Shah, including his authoritarian policies, perceived corruption and dependence on the West, political repression, and social and economic inequalities exacerbated by rapid modernisation policies. In addition, the Shah's illness and inability to respond effectively to growing demands for political and social reform contributed to a general feeling of discontent and disillusionment.

In January 1979, faced with intensifying unrest, the Shah left Iran and went into exile. Shortly afterwards, Ayatollah Khomeini, the spiritual and political leader of the revolution, returned to Iran after 15 years in exile. Khomeini was a charismatic and respected figure, whose opposition to the Pahlavi monarchy and call for an Islamic state had won widespread support among various segments of Iranian society. When Khomeini arrived in Iran, he was greeted by millions of supporters. Shortly afterwards, the Iranian armed forces declared their neutrality, a clear sign that the Shah's regime had been irreparably weakened. Khomeini quickly seized the reins of power, declaring an end to the monarchy and establishing a provisional government.

The Iranian Revolution led to the creation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, a theocratic state based on the principles of Shiite Islam and led by religious clerics. Khomeini became Iran's Supreme Leader, a position that gave him considerable power over the political and religious aspects of the state. The revolution not only transformed Iran, but also had a significant impact on regional and international politics, notably by intensifying tensions between Iran and the United States, and by influencing Islamist movements in other parts of the Muslim world.

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 attracted worldwide attention and was supported by various groups, including some Western intellectuals who saw it as a liberation movement or a spiritual and political revival. Among them, the French philosopher Michel Foucault was particularly noted for his writings and commentary on the revolution. Foucault, known for his critical analyses of power structures and governance, was interested in the Iranian Revolution as a significant event that challenged contemporary political and social norms. He was fascinated by the popular and spiritual aspect of the revolution, seeing it as a form of political resistance that went beyond the traditional Western categories of left and right. However, his position was a source of controversy and debate, not least because of the nature of the Islamic Republic that emerged after the revolution.

The Iranian Revolution led to the establishment of a Shia theocracy, where the principles of Islamic governance, based on Shia law (Sharia), were integrated into the political and legal structures of the state. Under the leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini, the new regime established a unique political structure known as "Velayat-e Faqih" (the tutelage of the Islamic jurist), in which a supreme religious authority, the Supreme Leader, holds considerable power. Iran's transition to a theocracy has led to profound changes in all aspects of Iranian society. Although the revolution initially enjoyed the support of various groups, including nationalists, leftists and liberals, as well as clerics, the years that followed saw a consolidation of power in the hands of Shiite clerics and increasing repression of other political groups. The nature of the Islamic Republic, with its mix of theocracy and democracy, continued to be a subject of debate and analysis, both within Iran and internationally. The revolution profoundly transformed Iran and had a lasting impact on regional and global politics, redefining the relationship between religion, politics and power.

The Iran-Iraq War and its Effects on the Islamic Republic

The invasion of Iran by Iraq in 1980, under the regime of Saddam Hussein, played a paradoxical role in the consolidation of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This conflict, known as the Iran-Iraq war, lasted from September 1980 to August 1988 and was one of the longest and bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century. At the time of the attack on Iraq, the Islamic Republic of Iran was still in its infancy, following the 1979 revolution that overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy. The Iranian regime, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, was in the process of consolidating its power, but faced significant internal tensions and challenges. The Iraqi invasion had a unifying effect in Iran, strengthening national sentiment and support for the Islamic regime. Faced with an external threat, the Iranian people, including many groups previously at odds with the government, rallied around national defence. The war also allowed Khomeini's regime to strengthen its grip on the country, mobilising the population under the banner of defending the Islamic Republic and Shia Islam. The Iran-Iraq war also reinforced the importance of religious power in Iran. The regime used religious rhetoric to mobilise the population and legitimise its actions, relying on the concept of "defence of Islam" to unite Iranians of different political and social persuasions.

The Islamic Republic of Iran was not formally proclaimed, but emerged from the Islamic revolution of 1979. Iran's new constitution, adopted after the revolution, established a unique theocratic political structure, with Shiite Islamic principles and values at the heart of the system of government. Secularism is not a feature of the Iranian constitution, which instead merges religious and political governance under the doctrine of "Velayat-e Faqih" (the guardianship of the Islamic jurist).

Egypt

Ancient Egypt and its Successions

Egypt, with its rich and complex history, is a cradle of ancient civilisations and has seen a succession of rulers over the centuries. The region that is now Egypt was the centre of one of the earliest and greatest civilisations in history, with roots going back to ancient Pharaonic Egypt. Over time, Egypt has been under the influence of various empires and powers. After the Pharaonic era, it was successively under Persian, Greek (after the conquest of Alexander the Great) and Roman domination. Each of these periods left a lasting mark on Egypt's history and culture. The Arab conquest of Egypt, which began in 639, marked a turning point in the country's history. The Arab invasion led to the Islamisation and Arabisation of Egypt, profoundly transforming Egyptian society and culture. Egypt became an integral part of the Islamic world, a status it retains to this day.

In 1517, Egypt fell under the control of the Ottoman Empire after the capture of Cairo. Under Ottoman rule, Egypt retained a degree of local autonomy, but was also tied to the political and economic fortunes of the Ottoman Empire. This period lasted until the early 19th century, when Egypt began to move towards greater modernisation and independence under leaders such as Muhammad Ali Pasha, often regarded as the founder of modern Egypt. Egypt's history is therefore that of a crossroads of civilisations, cultures and influences, which has shaped the country into a unique nation with a rich and diverse identity. Each period of its history has contributed to the construction of contemporary Egypt, a state that plays a key role in the Arab world and in international politics.

In the 18th century, Egypt became a territory of strategic interest to European powers, particularly Great Britain, due to its crucial geographical location and control over the route to India. British interest in Egypt increased with the growing importance of maritime trade and the need for secure trade routes.

Mehmet Ali and the Modernising Reforms

The Nahda, or Arab Renaissance, was a major cultural, intellectual and political movement that took root in Egypt in the 19th century, particularly during the reign of Mehmet Ali, who is often regarded as the founder of modern Egypt. Mehmet Ali, of Albanian origin, was appointed governor of Egypt by the Ottomans in 1805 and quickly set about modernising the country. His reforms included modernising the army, introducing new agricultural methods, expanding industry and establishing a modern education system. The Nahda in Egypt coincided with a wider cultural and intellectual movement in the Arab world, characterised by a literary, scientific and intellectual revival. In Egypt, this movement was stimulated by Mehmet Ali's reforms and by the opening up of the country to European influences.

Ibrahim Pasha, Mehmet Ali's son, also played an important role in Egyptian history. Under his command, Egyptian forces carried out several successful military campaigns, extending Egyptian influence far beyond its traditional borders. In the 1830s, Egyptian troops even challenged the Ottoman Empire, leading to an international crisis involving the great European powers. The expansionism of Mehmet Ali and Ibrahim Pasha was a direct challenge to Ottoman authority and marked Egypt out as a significant political and military player in the region. However, the intervention of European powers, particularly Britain and France, ultimately limited Egyptian ambitions, foreshadowing the increased role these powers would play in the region in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 marked a decisive moment in Egypt's history, significantly increasing its strategic importance on the international stage. This canal, linking the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, revolutionised maritime trade by considerably reducing the distance between Europe and Asia. Egypt thus found itself at the centre of the world's trade routes, attracting the attention of the great imperialist powers, in particular Great Britain. At the same time, however, Egypt faced considerable economic challenges. The costs of building the Suez Canal and other modernisation projects led the Egyptian government to incur heavy debts to European countries, mainly France and Britain. Egypt's inability to repay these loans had major political and economic consequences.

The British Protectorate and the Struggle for Independence

In 1876, as a result of the debt crisis, a Franco-British control commission was set up to supervise Egypt's finances. This commission took a major role in the administration of the country, effectively reducing Egypt's autonomy and sovereignty. This foreign interference provoked growing discontent among the Egyptian population, particularly among the working classes, who were suffering from the economic effects of the reforms and debt repayments. The situation worsened still further in the 1880s. In 1882, after several years of growing tension and internal disorder, including Ahmed Urabi's nationalist revolt, Britain intervened militarily and established a de facto protectorate over Egypt. Although Egypt officially remained part of the Ottoman Empire until the end of the First World War, it was in reality under British control. The British presence in Egypt was justified by the need to protect British interests, in particular the Suez Canal, which was crucial to the sea route to India, the "jewel in the crown" of the British Empire. This period of British rule had a profound impact on Egypt, shaping its political, economic and social development, and sowing the seeds of Egyptian nationalism that would eventually lead to the 1952 revolution and the country's formal independence.

The First World War accentuated the strategic importance of the Suez Canal for the belligerent powers, particularly Britain. The Canal was vital to British interests as it provided the fastest sea route to its colonies in Asia, notably India, which was then a crucial part of the British Empire. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the need to secure the Suez Canal against possible attack or interference from the Central Powers (notably the Ottoman Empire, allied to Germany) became a priority for Britain. In response to these strategic concerns, the British decided to strengthen their hold on Egypt. In 1914, Britain officially proclaimed a protectorate over Egypt, nominally replacing the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire with direct British control. The proclamation marked the end of nominal Ottoman rule over Egypt, which had existed since 1517, and established a British colonial administration in the country.