« Sources of International Law » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

m (Révocation des modifications de Simon (discussion) vers la dernière version de Arthur) |

||

| (17 versions intermédiaires par 2 utilisateurs non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 3 : | Ligne 3 : | ||

| image_caption = | | image_caption = | ||

| cours = [[International Public Law]] | | cours = [[International Public Law]] | ||

| faculté = | | faculté = | ||

| département = | | département = | ||

| professeurs = [[Robert Kolb]] | | professeurs = [[Robert Kolb]] | ||

| enregistrement = | | enregistrement = | ||

| Ligne 29 : | Ligne 29 : | ||

}} | }} | ||

= | = The typology of sources of international law = | ||

[[Fichier:STATUT DE LA COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE - article 38.png|vignette|centré|700px|[http://www.un.org/fr/documents/icjstatute/pdf/icjstatute.pdf Statut de la Cour Internationale de Justice] - Article 38]] | [[Fichier:STATUT DE LA COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE - article 38.png|vignette|centré|700px|[http://www.un.org/fr/documents/icjstatute/pdf/icjstatute.pdf Statut de la Cour Internationale de Justice] - Article 38]] | ||

A source of law is an old term used from the reworking of Roman law in the Middle Ages. These are the places where the applicable law for its passive component can be found. The right can be found in the sources of the law, such as the various codes where one can find the right. While the active component says that the sources are the mechanisms of legal production, there are ways through which the law is produced, so the legislation of the state through the parliament and all its procedures make the process by which the law is done is also a source of law. | |||

== | == What are the sources of international law? == | ||

Let us think about the fact that in international law there are no higher authorities, because each State is sovereign, allowing us to reach the conclusion that the sources of international law are covered by agreement and custom. Both sources are based on the fact that the subjects of law cooperate to make the rule of law binding on them. | |||

*''' | *'''Agreement''' | ||

An agreement is the most compatible with sovereignty because it is a reciprocal manifestation of a willingness to be bound to benefit from its rules. It is an exercise of sovereignty to decide to submit to a treaty. | |||

*''' | *'''The custom''' | ||

Making an agreement is an act of practice, but beyond that, it is possible to practice other things on a regular basis because they are considered useful and must be enforced in law. For a long time, States have recognized jurisdictional immunity before the courts, i. e., an individual cannot cite the acts of one State before the acts of another State. Customary law is also something that can be practiced in a parity society, because each one practices and then there is convergence that can be summed up as a rule of law. | |||

Legislation presupposes a superior who can enact a law at a lower level, in international law no one has legislative power, no one can compel States to comply with it. International law is a science that thinks its own violation. | |||

== The main sources == | |||

They make it possible to function within the framework of sovereign states that are not subject to a senior executive. The regulation is found in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which is the oldest jurisdiction for the settlement of interstate disputes. This court, which has been in existence since 1921, can and must deal with disputes under international law. In 1945, it was considered useful to explicitly state international law and list its sources. | |||

# '''Agreements / Treaties'''; | |||

# The '''general customary law''', which is therefore universal and binding on all States; | |||

# The '''general principles of law''' recognized by "civilized nations". | |||

These sources are the main ones, as they can be directly applied to a particular case to give it a legal solution. | |||

A State asks for a legal opinion: it is necessary to deal with a legal issue such as delimiting the continental shelf between the DRC and Angola. It is possible to rely directly on a treaty, as it is a source of law applicable between the two States, but also on customary law by referring to the general practice of delimitation. On the other hand, if doctrine and jurisprudence are used as auxiliary means, the fact that they are auxiliary sources means that one cannot rely directly on doctrine or jurisprudence to base a legal solution. | |||

== Auxiliary means == | |||

States are the "legislators", the doctrine is not lawful, but it can be useful, because those who have written fundamental books have examined the practice and provide practical tools for interpreting applicable rules. The same is true of jurisprudence, contrary to common law, the foregoing, in international law, does not do justice. It is not possible to rely on jurisprudence or arbitral awards, it is possible to consult the arbitration, because the lawyer of the time will have set out legal rules, but an arbitrator only allows the dispute between the two States that have referred it to him. It is only if we are convinced and if this has not changed since the time of arbitration that we can apply a jurisprudence. | |||

It is clear that the applicable sentence of the time based on a treaty that is not applicable now cannot be applied. Doctrine and jurisprudence are consulted only in the sense that they can contribute something. | |||

If the parties to the proceedings agree, the court may also judge in fairness. This means that in some cases the court may judge by not applying international law, but fairness, i.e. what the sense of justice suggests to it in an individual case. For a court of justice or any operator, the power to decide or propose things in fairness cannot be abrogated. | |||

Fairness means a change in the rule of law. This is only possible if the parties agree to do so. The Court has been allowed to play an additional role when the strict application of the law is not considered by the parties to be appropriate for resolving their disputes. | |||

It is not said that Article 38 must necessarily be exhaustive. We must distinguish between limiting and illustrative provisions. Actually, it's illustrative except that at the same time it's a little bit exhaustive/limitative, because all the important gears are mentioned and you can't invoke others. This is not exhaustive in the sense that there cannot be other specific sources. | |||

== Other sources == | |||

Broadly speaking, Article 38 is exhaustive, but in detail it is not. Other sources are less important, however. The special custom is not mentioned, Article 38 (b) contains a general provision, but there are regional customs not covered by the status that do exist. For example, the International Court of Justice has recognized that there are rights and duties between India and Portugal to run along the coast to the Portuguese enclaves. | |||

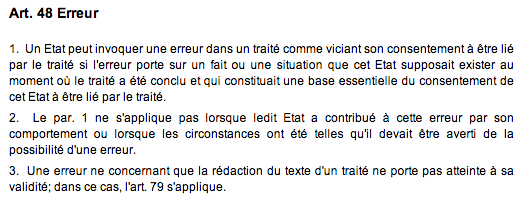

Secondary sources are also not indicated. If a treaty establishes the power of a certain body to impose binding conditions on states, such as the UN Security Council's case of the UN Charter of the United Nations, what is here is a particular source of law, it is a source of law, because it contains legally binding and enforceable standards.[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 41 et 42.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/chap7.shtml Chapitre VII : Action en cas de menace contre la paix, de rupture de la paix et d'acte d'agression - articles 41 et 42]]] | |||

These are derived standards adopted under the Charter of the United Nations, it is treaty law, secondary law also known as "derived". A particular standard can only be dealt with in a specific case that will apply and sanction in a particular case. This is a relatively common phenomenon, but not contemplated, as it falls within the framework of treaty law. | |||

In conclusion, there are some minor, derived, and sometimes non-core sources that have not been conducted in Article 38, making the type of provision non-exhaustive in a sense. Reference may be made to Article 38 of the ICJ Statute for an overview of these sources. | |||

= The question of the hierarchy between sources = | |||

There could be a lot of talk about it. The question of hierarchy is whether we have superiority and inferiority in the sources of international law. The answer is no, it is fairly easy to understand why it is negative. | |||

The hierarchy of sources is fundamentally a matter of democratic legitimacy. The constituent with the greatest democratic legitimacy either because the combined chambers vote or the people have to vote; the ordinary right is already less, etc.. It is understandable that in this type of state organization, it reflects an order. | |||

It is the States that legislate and always they do. The treaty is an act of ratification stemming from reciprocal wishes. There is no reason to give the will of one State greater weight than another, all States are on an equal footing, all sources are coordinated and have the same degree of prominence. | |||

A collision problem cannot be solved based on a hierarchy of sources that do not exist. For example, if the article of a convention X and contrary to a customary rule Y, one cannot invoke the argument of the hierarchy of sources, each is at the same level as the others. | |||

== How do we resolve a conflict between norms? == | |||

In the above example, the collision is between two norms: between an article and a customary rule. We therefore have here a collision between two standards and not between two sources, it is not at the content level, it is Article X against Rule Y. Article X is a conventional norm and rule Y is a customary norm, i. e. an injunction or organizational rule. It is on this level that the collision between two standards will have to be resolved through the rules on the collision of standards. | |||

There are essentially two: | |||

*'''rule LEX SPECIALIS''' : the most special law derogates from the more general rule,"lex specialis derogat legis generalis". This means that the most special rule takes precedence over the general rule. It is quite logical, because it is quite intelligent to think that States wanted the most detailed rule to take precedence, because they have considered the function of this more specific rule. For example, universal investment standards serve as an illustration: if two States decide on a bilateral convention, it makes perfect sense to say that between the two States that have concluded the convention, it has priority over the more general rules. Both states have adopted the treaty because they do not agree with the general rules. | |||

*'''rule LEX POSTERIOR''' : « lex posterior derogat legi priori »,the later law derogates from the earlier law. The rule makes perfect sense, because if we have a multilaterally concluded 1958 law of the sea treaty and another one in 1982, and now we have States that are party to the 1958 Convention and at the same time to the 1982 Convention. The posteriority rule, because the most recent rule was intended to normalize a more recent situation. If these States have concluded only the 1958 Treaty, only this rule will apply until both States are parties to the 1982 Convention | |||

== Knowing when two rules are in conflict and what rules to apply == | |||

It is a question of substance and interpretation; we must interpret the standards and see if there is a conflict between them. The presumption rule is that there are no conflicts between the standards. If the problem with interpretation cannot be solved at this time, there is a conflict. The application of the rule depends on the case at hand, as both rules may draw in the same direction. There may be a case where they draw in different directions where the oldest rule is the most special rule and the newest general rule. There are maxims in the maxims to try to harmonize. | |||

It's a complicated question, because there is nothing mechanical, it's a question of interpretation and conventions that requires the lawyer's support to solve the problem. | |||

*First, we have a hierarchy that even exists at the source level within international organizations. | |||

It would already be necessary to show that domestic law was in line with public international law. The domestic law of international organizations is international law. On the formal aspect, the law of international organizations derives from an international treaty; the law deriving from a treaty must be of the same nature as a treaty that carries it. | |||

In international organizations, there is a hierarchy of sources, as there is exactly within states. In States, there is the constituent and the legislature that are not placed on an equal footing, but placed hierarchically in a subordinate relationship, so the constitution is higher than simple legislation. | |||

In international organizations, the founding treaty is the founding treaty, all decisions taken must be in conformity with the founding treaty. States adopting resolutions must do so in accordance with the constituent treaty, otherwise it is a null resolution. | |||

Internally, it is the secretariat with the Secretary General that refers to the executive of the organization. It also adopts rules such as, for example, the Staff Regulations. These rules are inferior to the constitutional treaty, but also to the texts adopted by the General Assembly. If the meeting orders the secretary to issue a rule, he or she is bound to carry out what the senior complainant body says. | |||

Thus there is an organization as in domestic law, the constitution, the texts adopted in the general assembly and then the texts adopted by the secretariat which incarnates the executive. The hierarchy, however, is not similar to domestic law because it is stricter, in domestic law the constitution does not simply override ordinary law. There are, if necessary, procedures for invalidating the law if you have a constitutional court, as is the case, for example, in Germany. Legislation passed by parliament in Switzerland may be unconstitutional, but it is not repealed and remains in force. Municipal law may sometimes prevail over cantonal law. | |||

There is a hierarchy between the various texts, which sometimes translates into a strict hierarchy, sometimes it is an indicative hierarchy as in some internal legal systems where there is no sanction mechanism. | |||

*Second, the doctrine perceives another hierarchy that refers to the phenomenon of normative hierarchy. | |||

In Article 103 of the Charter of the United Nations, this provision reads as follows:"In the event of a conflict between the obligations of the Members of the United Nations under this Charter and their obligations under any other international agreement, the former shall prevail". This provision, if we take its text, indicates that for members of the United Nations, when they have obligations under the Charter, for example to implement Security Council sanctions, and they come into conflict with a treaty other than the Charter, such as a trade treaty; then the former will prevail. | |||

Charter obligations are superior to other treaties. The provisions of the Charter are superior to the provisions of the other agreement which contains lower obligations. However, it is a conflict rule, but not a priority rule exactly like lex speciali or lex posterior. | |||

There is something like a desire for hierarchy, the obligations of the Charter are considered to be higher than those contained in other treaties. The aim in 1945 was to protect, above all, the functions of the United Nations in peacekeeping and the Security Council. | |||

The Security Council enacts sanctions against State B because it believes that it threatens peace and calls on UN members to implement sanctions. Without Article 103, the trade treaty would be applied because it would be the lex speciali and the superior rule. | |||

There have been no real hierarchies in international law because states are always equal to themselves and when they legislate there is no reason to privilege a piece of legislation. Conflicts must be resolved on a case-by-case basis in accordance with interpretative principles. | |||

= The Treaties = | |||

Treaties are a very important area of international law, because we work in a subject with fundamentally written texts, it is like the law for domestic law. For customary law it requires specialists, because it is unwritten law. | |||

There are a whole series of advantages of agreements over custom, but we will mention two. The benefits of custom are exactly the opposite of those of treaties. | |||

First and foremost, the advantage is legal certainty. Foreign policy will fluctuate according to the circumstances and interests involved. Foreign policy is an area in which the positions of states are constantly changing. However, there are issues that need to be laid down by rules that provide some legal certainty for the future, for example with regard to investments. If a State wishes to attract investors, it is interested in providing them with a framework that does not depend on domestic law, which can be changed at any time. By adopting treaties that cannot be unilaterally amended, legal certainty is created. It may also be to delimit a territory between what is a State A and a State B. We can go further, in the case of immunities, States have a certain interest in knowing that they cannot be brought before a court, as this would cause them considerable harm. There are old rules on immunity that have now been codified. So there is a collective interest in having some security against attacks from all sides that could be subordinate to one court of another. | |||

All these subjects require a certain legal regulation in order to be sufficiently sure that they must be written. | |||

The Treaties alone allow for a detailed regime. Customary law is a good way to determine the main lines of action. If we want to create a specific regime or an international organization with special functions, we cannot do this on the basis of customary law, we can only do it on the basis of the law of treaties. If we want to do humanitarian law, the rules must be codified to apply them, because the military are not lawyers. Codification of the Treaties is necessary. As, therefore, international society has become increasingly important and States wish to have legal certainty for a certain period of time, and since international society is becoming increasingly complex and requires increasingly specific regimes, this explains why treaties have taken an increasingly important place. | |||

Today we do not know exactly how many treaties have been concluded. For treaties registered with the League of Nations or the United Nations, the figure is about 60,000. The United Nations Treaty Section estimates that there are approximately 40,000 unregistered treaties. So there would be about 100,000 treaties in force around the world. Many are technical points, protocols added with technical vocabulary. There are only a few hundred treaties that are really important for international political life. | |||

This is not an insignificant figure and it is not easy to manage this number of treaties at the universal level. Especially since there are 5 official languages in the United Nations. | |||

== Definition == | |||

We have somewhat varied terminology for international agreements. This terminology is relevant, on the one hand, because each word has its own meaning, but, on the other hand, it does not have its own meaning, because each legal regime is not identical. | |||

We have different words: agreement, treaty, convention, covenant, pact, protocol, concordat or even minutes. On the one hand, these differences in terminology do not have any legal effects because all these different texts mentioned are all agreements and it is the same law of treaties and international agreements that applies to them. Thus terminology is not necessarily relevant. Each of these agreements is applicable independently of the name. What is important is to verify that it is an agreement within the meaning of international law. | |||

However, we would have every right to wonder if the same legal regime applies. If we have different terminologies it is because the different words make each of these words have their own meaning<ref>OECD Nuclear Energy Agency - [http://www.oecd-nea.org/law/nlbfr/documents/203_233_Accordsbilaterauxetmultilateraux.pdf Accords bilatéraux et multilatéraux]</ref> : | |||

* '''Agreement''': to cover any treaty text or even what is not a text if they are verbal. | |||

* '''Treaty''': used for written texts in the proper sense of the word, what is oral is an agreement. | |||

* '''Convention''': used for multilateral treaties; a multilateral convention is a contradiction. A convention is an open treaty because it is multilateral. | |||

* '''Covenant''': written treaty, but the term pact is intended to emphasize the particular importance attached to the text. These are fundamental texts adopted with increased solemnity, such as the Covenant of the League of Nations. | |||

* '''Protocol''': it is a treaty, but by that we mean a treaty attached to an earlier treaty that modifies the earlier treaty on certain points. In IHL, it is said that the two additional protocols to the 1949 Geneva Convention are complementary to the Geneva Convention, which it amends in some respects and supplements in others. | |||

'''Concordat: normally reserved for the agreements of the Holy See by historical tradition.''' | |||

*'''Procès-verbal''': sign the origin of the agreement, this means that there were discussions and that a record was drawn up. It shows the origin of the agreement, basically, these are summaries of a negotiation signed and therefore enhanced in an agreement. | |||

In law, every word counts and nothing is interchangeable or almost interchangeable. | |||

The legal regime, on the other hand, is the same, but there are slight distinctions. The vocabulary does not provide differences in treatment, but indicates the nuances in the type of text. | |||

There are four building blocks, four "check points" to see if a given text constitutes an agreement in the sense of international law; these four elements are cumulative, meaning that the existence of the four must be verified. If one of them is lacking, we are faced with a text that may be of a treaty nature, but it is not an agreement within the meaning of public international law: | |||

#'''There must be concordant wishes''': an agreement is always based on a convergence agreement between the various parties. The subjects, in principle, must agree on something, there must be a minimum of common denominators. If, on the other hand, agreement cannot be reached on any point because the differences continue to the end, then we are dealing with dissent. This point is self-evident, but it should not be forgotten, particularly with regard to oral agreements, and it is exactly the same in domestic law. | |||

#'''The conclusion of an agreement on international law requires a subject of international law''': an authority vested with the legal personality of international law. It is quite natural that the agreements of a given legal order should be concluded by subjects of that legal order. The subjects of international law are an area that has already been addressed; it is States, but especially others that can conclude international agreements under public international law. The only subject of international law so limited in its powers that it cannot conclude treaties is the individual we are. The individual may enjoy certain rights under international law. It may also be subject to certain obligations. However, the individual can only exercise his or her human rights, which are engraved as much as the criminal obligations imposed on him or her, he or she is not a political subject with autonomy of action and cannot therefore conclude international agreements. When companies or individuals enter into a concession contract with a concession State, an investor enters into a contract with another treaty State that is binding but not based on international law. The parties will make a choice of law by choosing a legal order other than international law. The parties can of course choose to submit this contract under the principles of international law because they have called it, but spontaneously this agreement is outside international law. | |||

# '''An agreement in the sense of international law must produce legal effects, also known as "legal effects"'''; if it does not produce legal effects, it is not an agreement in the sense of legally binding. Of course, agreements under international law are voluntary under the law. Here this is not the case, there may be certain agreements between States; they are not agreements, but concerted non-Convention acts. We are told that this is a concerted act, but it is unconventional in the sense that it is not binding. We are also talking about political agreements and the "gentleman agreement". A whole series of examples of such agreements are, for example, the final act of the Helsinki Accords of 1905, from which the OSCE is emerging. The final act of the Helsinki conference is made as a treaty, but it is not a treaty because states do not want to bind themselves legally, they want to assume political obligations. This means that States believe that these obligations should remain in the realm of politics and that, in the event of a violation, legal mechanisms such as liability should not be implemented; States are not obliged to conclude treaties, but rather engage on a purely political level. | |||

#'''The agreement must be governed by public international law''': in order for it to be an agreement, the law that governs that agreement must be public international law. We have, for example, a whole series of agreements between governments that are legally binding and have legal effects concluded by States. The first three conditions are met, however, but they are not international agreements in the legal sense, because the applicable law is a different law than that of the international order; this may be international trade law or Swiss law. States do it because there are areas that are not political. A state can sell an aircraft, a ship or paper to another state, to exchange an airplane a treaty can be concluded, but it is not worth it because it has solemnity. If States so wish, they may conclude agreements by choosing another legal system that is not international law. | |||

These are the four conditions of general international law. This refers to the general rules on the existence of agreements. However, there may be special rules. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties is the codification of the law of treaties. If we have treaties or an agreement, we can ask ourselves legal questions about this recurring agreement is important. For example, the International Law Commission has proposed to draft a convention that contains all the information on treaties. The Vienna Convention is the law of treaties, but applies only to certain treaties because it governs the life of certain treaties. | |||

In the Vienna Convention, we are in the field of treaties and this applies only to texts, only to written agreements. By this alone, we can have divergences between general law and particular definitions contained, for example, in the Vienna Convention. This difference means that an agreement within the meaning of general law makes it possible to distinguish between agreements. On the other hand, in order to be able to apply the Vienna Convention, the treaty in question must meet the conditions of that Convention, otherwise it will not be applied to it. However, customary law is applicable because it is covered by an agreement under international law. | |||

There is an articulation between customary law which is general, but if you have special law, customary law becomes a lex speciali. | |||

The Vienna Convention applies to treaties. In article 2 of the 1969 Vienna Convention, the term "treaty" is defined as meaning an international agreement concluded in writing between States and governed by international law, whether it is contained in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments, and, whatever its particular denomination. | |||

There are two elements that stand out and stand out. This Convention shall therefore only apply to agreements concluded in writing, otherwise it shall not apply as well as to an oral agreement. Thus, the Vienna Convention is more restrictive than general law. In other words, in order to be able to apply the Vienna Convention, four conditions are required: | |||

# an agreement | |||

# written | |||

# concluded between States | |||

# but above all it must have been ratified by the Contracting States. For example, an investment treaty will only be valid in the context of the Vienna Convention if the contracting parties have ratified it. | |||

The second Vienna Convention of 1986 was concluded to govern treaties concluded between States and international organizations and treaties concluded between international organizations. The 1986 Convention concerns treaties between States and international organizations, or States between States, or international organizations between international organizations. For example, the treaty between Switzerland and the United Nations on the headquarters of the United Nations in Geneva. | |||

The 1986 Convention has not yet entered into force because it has not yet received sufficient ratifications. For agreements between States, the 1969 Convention is applied, while for international organizations, the 1986 Convention is applied, but since it has not entered into force, customary law is applied. | |||

We are doing all of this because the legal regime is potentially different. In customary law, these may not be the same rules, but at the same time, the situation is quite simple as in IHL. In the treaties, we are fortunate because they are the same rules, that is, if we take customary law or one of the conventions in general terms, we have the same rules. | |||

The 1969 Convention photographed the practice of States while the 1986 Convention was aligned with the 1969 Convention. It is always important to determine which title applies what. It is always necessary to ascertain whether it can be applied either as a rule of customary law or as a convention between States. The substantive aspects of treaty law lead to the same rules, which makes the task easier. | |||

This is a happy circumstance in treaty law, but it is not always the case. The customary case is not fully aligned. | |||

We now know what a treaty and an agreement is, but there is often an impression among philistines that a treaty must always be very solemn and formalistic, that a treaty must be concluded with lengthy procedures. Ritualization is an important treaty to mark solemnity because it is politically useful. | |||

However, the law of treaties does not provide any rule in this regard, which is the will of States. Treaty law is fully flexible on questions of form. The law of treaties is sovereign and adult. | |||

In the Aegean Continental Shelf case brought before the Court of Justice in 1978, the legal question is whether a treaty can be concluded in a press release. There is a very special condition for bringing a case before the International Court of Justice; it requires the consent of all the parties involved, an agreement, a consent. The question is whether a joint press release of the two ministers could be an agreement in the sense of international law because if it was an agreement it could have founded the competence of the agreement; it was said that if the ministers could not reach an agreement the court could be seized. Therefore, the content of this agreement was a consent, but in order for the court's jurisdiction then to have been given, it had to be verified whether this press release was a joint agreement. Only after a legally binding agreement can the Court's clemency be founded. | |||

In 1978, the Court responded in an orthodox manner by saying that there is no reason to believe that a joint press release could be a perfect international agreement. The Court did not need to go any further because it felt that there was no commitment in the agreement to accept the Court's jurisdiction, there was only an agreement to consider going to the Court in a subsequent agreement. To sum up, a joint press release can be an agreement. | |||

In the case of territorial delimitation between Qatar and Bahrain<ref>[http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/afdi_0066-3085_2001_num_47_1_3660 Decaux Emmanuel. Affaire de la délimitation maritime et des questions territoriales entre Qatar et Bahrein, Fond (arrêt du 16 mars 2001 Qatar c. Bahrein). In: Annuaire français de droit international, volume 47, 2001. pp. 177-240].</ref>, the same question was posed almost exactly in the same way. This was a signed record of negotiation. Saudi Arabia had been there to do the good offices of mediation and had also sent a secretary to govern the minutes. Following the discussions, the foreign ministers signed the minutes. In 1993, the Court considered that the minutes signed by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs were informal but valid treaties, and that the content was such that the Court could be involved in the matter. | |||

A treaty can be treated in a totally informal manner. Only whether States were willing to conclude a legally binding instrument or whether a text could be interpreted as meaning that they had accepted a legally binding agreement will be verified. | |||

As Minister of Foreign Affairs, you have to be careful what you sign. Formalism is not necessary, it's a discretionary question, we leave the choice to the States. | |||

== Conclusion == | == Conclusion == | ||

In the conclusion of treaties, there are a whole series of purely political issues, such as the conduct of negotiations involving framework rules, which are far removed from the details of the negotiation, the aim is to maintain the usefulness of the negotiation. This is a question that should be left to politics. | |||

There is a whole practical question concerning the conclusion of treaties. There is a first and very important question of who can negotiate a treaty. | |||

==== Negotiation and signature ==== | |||

Treaties are generally negotiated, there are always preliminary discussions even for a small treaty signed during a dinner. There are very different situations between multilateral treaties and bilateral treaties negotiated at a minimum. | |||

There is always the question of who can conclude, who can negotiate and sign the text, what is at stake is legal certainty; we must see and determine the authorities. The issue is governed by international law, but is partially left to domestic law. That is to say, international law contains certain rules; otherwise it is left to domestic law. | |||

Persons designated by international law as such, who still have the power to conclude a treaty for a State by signature, are mentioned in Article 7 §2 a. of the Vienna Convention vested in the full powers: "Heads of State, Heads of Government and Ministers of Foreign Affairs, for all acts relating to the conclusion of a treaty". | |||

This means that the head of state is traditionally the person entitled to conclude treaties, the head of government who can be described as prime minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs can always bind the state. | |||

Thus the Permanent Court in 1933 had a special case concerning Eastern Greenland: there was an agreement between Norway and Denmark through a simple agreement reached by the Foreign Ministers. The Court held that this agreement bound Norway because its Minister of Foreign Affairs was empowered to make commitments for its State. | |||

As for other persons, as a general rule, the first paragraph of article 7 reverts to the first paragraph, those other persons can only negotiate for a State if they are given full powers. If Switzerland decides to send someone to negotiate a treaty for Switzerland, a formal letter must indicate that a person has the right to represent Switzerland at the conference showing that he or she is the representative of the State that can sign the agreement on the basis of what has been authorised to him or her under the full powers, these powers must also be notified to the other parties. | |||

Three persons are still authorized and a fourth person may be authorized by a letter of full authority. | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 7.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a7 article 7]]] | There is one more development, the Court has said; it is an increasingly common practice, in international law, that the ministers in charge have the right to conclude treaties in their area of competence. For example, the Minister of the Environment goes to environmental conferences and signs agreements for his state. This is a recent development that poses a series of legal problems. In the case of the armed cases between the Congo and Rouanda, paragraph 47 of the 2006 ruling explains the broadening of the practice and in which cases the ministers in charge may conclude treaties, it is empowered to negotiate and sign.[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 7.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a7 article 7]]] | ||

==== Adoption ==== | ==== Adoption ==== | ||

In bilateral negotiations, there are no prescribed rules, there is total flexibility. Delegates or ministers will sign the treaty. In the case of a multilateral treaty, it is much more complex. A text negotiated in the framework of an international organization or a conference, one can have up to 190 States in such a conference, in this case what is important is to authenticate the adopted text. | |||

When there's two of us, we can see what we're working on. In the case of an international conference where thousands of texts circulate with amendments up to the last minute, it is clear that it is essential to authenticate the text. | |||

We proceed to the adoption of the text, which means that when an agreement has been reached and compromises have been reached, the text is put to the vote. The president will check whether the required majority is reached, often it is the rule of two-thirds or a simple majority. If the majority is reached, the text is adopted, but it is from now on that no one can argue it. | |||

Delegations go before the President to initial the text in order to authenticate it. The Chair had the original text initialled page by page by delegations to indicate that all pages had been viewed. On the last page, the delegate signs, sometimes it may be deferred if the Minister has to sign and is not present. At this point the text is adopted and authenticated. Negotiation is now complete and the text can no longer be changed. | |||

When the text is signed, it has certain legal effects. With adoption, this becomes a treaty text, but the signature enhances its status, as some legal effects will follow. | |||

There are two in particular. Most importantly, there is a non-existent effect. The signed text is not binding on States, it is not in force and at the same time the State has not accepted to be bound by the text, the signature does not make the text binding. Exceptionally, signature is binding on States only if the treaty is concluded in the case of a so-called "simplified" or short procedure. In fact, it is not just a signature, but a signature and ratification at the same time. States agreed not to ratify the treaty separately, but to ratify it uni actum, so signature is ratification. | |||

This is hardly ever the case, but more than once in bilateral treaties where ministers can directly engage their states, this is not to accumulate acts for nothing. | |||

In multilateral conventions it is more solemn, ratification is later, the signature is not binding. The simple signature: what is its legal effect? | |||

# | # '''with signature, the transitional provisions enter into force immediately''': when the treaty is signed, the provisions contained in the final clauses which are attractive to the process of implementing the convention enter into force. In 1998, a treaty was concluded on the International Criminal Court in Rome - it is clear that we will not wait until the treaty enters into force to question its creation. Preparatory measures are provided for in the transitional provisions and lead to ratification unless they explicitly state otherwise, they are applicable at the time of signature. If we signed, we were told that we have a favourable provision for the convention. | ||

# | # the second effect is legally much more complex, referring to article 18 of the Vienna Convention. It provides that when a treaty is signed, as a signatory, '''there is an obligation not to empty the treaty of its object and purpose before it enters into force'''. It is impossible to do acts that sabotage the void of meaning. For example, a treaty is concluded between State A and State B under which the two states undertake to reduce customs duties on tomatoes by 50%, which will enter into force in January 2014. State A says to itself, on December 31st, I will double my customs tariffs so that when the treaty came into force, the customs tariffs have not changed, while state B, in good faith, will halve its customs duties, meaning that there was bad faith behaviour by A. Thus, the treaty is emptied. However, it may be difficult to determine what Article 18 establishes and what it does not. | ||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 18.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a18 article 18]]] | [[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 18.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a18 article 18]]] | ||

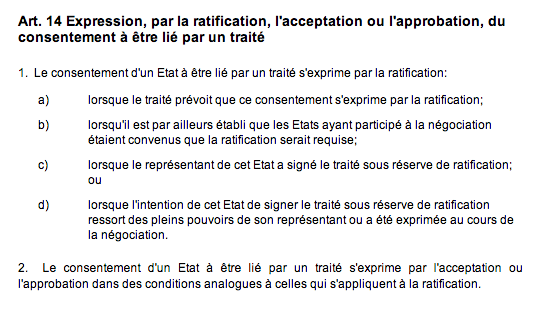

=== Ratification === | === Ratification === | ||

The signed treaty is not binding on the parties, let alone giving effect to it. In articles 11 et seq. of the 1969 Vienna Convention, ratification is the consent to be definitively bound by the treaty. | |||

Since ratification does not necessarily coincide with signature, this means that a State has time to consider whether or not it wants to be bound by the treaty. If he wishes, he will ratify it. | |||

There is a time for reflection; the negotiating States know what to do with it. The time for reflection comes from the democratic institutions of domestic law. At the time of the kings, the signature was worth ratification. With the advent of Republican regimes, the situation has changed. It is therefore the executive branch that negotiates and ratifies the treaty. If, therefore, the entire process of concluding the treaty up to and including the choice to become a party to that treaty is in the hands of the executive branch, it would mean that the executive branch could take decisions of great importance for national life without the democratically elected body representing the people having any say. | |||

All the Republican states, and first and foremost the United States of America, have each time requested that they should be able to sign and refer, decide later on whether or not they want to be bound, because it is necessary to consult beforehand. The legislator must give the "green light". We sign act referendum. That is the reason for the time for reflection. The concern of States is democratic participation; it is a concern of domestic law. | |||

Ratification from the standpoint of international law refers to articles [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a11 11], [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a12 12], [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a13 13] and [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a14 14] of the Vienna Convention. Ratification is the final consent to be bound, but ratification from the standpoint of international law is a letter sent by the executive branch, someone at the Department of Foreign Affairs will send a letter to the treaty depositary who is the official elected by the contracting states to manage the treaty. Ratification therefore takes the form of a letter sent to the depositary stating that, after referring to it domestically, State X consents to be bound by the treaty. | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 11.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a11 article 11]]] | [[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 11.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a11 article 11]]] | ||

| Ligne 267 : | Ligne 259 : | ||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 14.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a14 article 14]]] | [[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 14.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a14 article 14]]] | ||

It is often believed that it is parliament that ratifies a treaty, which is perhaps not wrong from the constitutional law point of view. In fact, Parliament authorizes ratification. | |||

For example, we ratify a treaty and sign it marking the end of the negotiation procedure. Then the negotiators disperse. International law has nothing to say, it is a matter of domestic law. Assume that the fictitious treaty signed, the negotiator takes it with him and enters State X. The State provides that the text must be submitted to parliament so that it can debate and decide whether the treaty is good for the State or not. The text was discussed and the vote was taken. If Parliament considers that the treaty is sufficiently good by majority vote, then Parliament has given the "green light" for the executive to ratify it. In virtually no state in the world, the executive is obliged to ratify when parliament has said "yes". | |||

The executive still has a margin of decision. If an impromptu event occurs, the executive can slow down ratification and wait. Therefore, Parliament does not ratify the treaty from the point of view of international law, it authorises it. Constitutional law uses the term "ratification" in a different way. If the parliament or people do not authorise ratification, then the executive is obliged not to ratify and will notify the depositary that it will not be obliged to be a party to the treaty because it has not succeeded in obtaining parliamentary approval. | |||

The time for reflection is a matter that depends on domestic law; if parliamentary approval is not required, it can be ratified at the time of signature, which is called the "short conclusion procedure". This avoids uncertainty, buoyancy, the risk of adopting treaties and the risk of waiting decades for states to ratify treaties to become obsolete and ruinous. | |||

Still, it is incumbent on democracy and the separation of powers to allow time for reflection. If domestic law directly authorizes ratification, it makes things easier. However, this is the case for the vast majority of treaties, because they concern subordinate and technical conditions,"treaties on trifles", minor objects of importance. Such treaties can be concluded even in Switzerland or they can be concluded directly. | |||

What if the executive ratifies if it did not have to? | |||

For example, the text is submitted to parliament, which does not authorize ratification and the executive still ratifies, or if the parliament says "yes" and the executive ratifies, but in reality there was no quorum required for the vote. It is a question of treaty validity.[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 46.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a46 article 46]]] | |||

We distinguish between ratification and accession to a treaty also known as "accession to a treaty". What is the meaning of this distinction? | |||

The result of both is the same, it is always the definitive consent to be bound by the treaty. The result is therefore that the acceding or ratifying State is bound by the treaty. Since the distinction is not downstream, it must be upstream. The lawyer often has a reason to distinguish the word. | |||

The distinction is who is entitled to do an act or otherwise. Ratification is reserved for States that have participated in the negotiation of the treaty. Ratification is a right for them, a State that has participated in the negotiation can become a party to the treaty, it is not obliged to become a party to the treaty, but has a right to ratify it even 20 years later. On the other hand, States which have not participated in the negotiation, third States, may become party to the Convention on the terms which the Treaty will make them. Bilateral treaties are in principle closed, even multilateral conventions are more or less open. The North Atlantic Treaty is not as open as that, we have to look at the treaty itself, which will say under what conditions another state can accede to the treaty. If there is no clarification, it means that accession is subject to the consent of all other parties to the treaty. | |||

This becomes an option only if the treaty grants it. Thereafter, it becomes a State bound by the Treaty, without accession, there is no distinction. | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article | We assure you that the treaty has been fortunate, it has been ratified. Now, it's about when it's going to come into effect, sending backà l’article 24 de la convention de Vienne de 1969.[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 24.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a24 article 24]]] | ||

=== Entry into force === | |||

A treaty does not enter into force once it has been ratified. With the second ratification, the treaty can enter into force when there are two parties, but if it is intended to bind all the States of the world, the issue is different. In the final provisions are explained when the treaty enters into force. | |||

In bilateral treaties, these clauses are generally forgotten, but if there are no specific clauses, it is considered that it is at the time of the second ratification that the treaty enters into force when the instruments of ratification are exchanged. | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 84.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a84 article 84]]] | For open multilateral conventions, those that are intended to have many States parties, the rule has gradually crystallized in modern times to have 60 ratifications plus a certain period of applicability. It is at the time of the sixtieth ratification plus the first of the following month.[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 84.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a84 article 84]]] | ||

There is another possibility of bringing the treaty into force provisionally, that is, it has been signed and is awaiting ratification. If it is considered unfortunate because the treaty is urgent and it is in our interest to bring it into force immediately, Article 25 provides that this can be done. | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 25.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a25 article 25]]] | [[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 25.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a25 article 25]]] | ||

There may be a provisional partial agreement of the treaty or some States agree among themselves to apply only part of the treaty. Everything always revolves around the agreement of the States on this matter. If we do not ratify, there are difficulties such as the difficulty of going back on provisions created when they were made in accordance with the law. | |||

Article 102 of the Charter of the United Nations is applicable to all Member States providing that when a treaty has been agreed and entered into force, the signatory States shall be obliged to register it in the United Nations Treaty Service in New York. Since laws are published domestically, they are published internationally. | |||

[[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 102.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/chap16.shtml Chapitre XVI : Dispositions diverses - article 102]]] | [[Fichier:CHARTE DES NATIONS UNIES - article 102.png|vignette|center|700px|[https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/pdf/charter.pdf Charte des Nations Unies] - [https://www.un.org/fr/documents/charter/chap16.shtml Chapitre XVI : Dispositions diverses - article 102]]] | ||

Finally, treaties do not apply retroactively; they apply to facts, circumstances and events that occur after the treaty has been concluded. They shall not apply to facts and circumstances prior to its entry into force. | |||

Entry into force may depend on. The Convention shall enter into force on the date specified in the clause; for States acceding to it at a later date, the treaty shall enter into force at a later date. | |||

Non-retroactivity must be determined on the basis of the entry into force for each State. This is not a peremptory rule, because States can agree, but must regulate this decision. They must expressly say or wish to do so in such a way that it can be said in the interpretation that there was a willingness on the part of States to apply a convention retroactively. In some areas of international law, rules cannot be applied retroactively. | |||

Finally, there is no question of non-retroactivity for customary law. Retroactivity is a matter of treaty law. Customary law, from the moment the rule is established, applies to all States. It is not retroactive, but binding on all States. Events prior to the birth of the customary rule are not taken into account. There is only one critical date, the rule covers all events from birth. | |||

== | == Reservations == | ||

This is a specificity of international treaties, there is nothing comparable in domestic law contracts. The rules on reservations can be found in articles 19 to 23 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Subsequently, the International Law Commission worked on the issue, which led to the adoption of a non-binding text or the Commission recalls the rules on reservations. | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 19.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a19 article 19]]] | [[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 19.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a19 article 19]]] | ||

| Ligne 336 : | Ligne 322 : | ||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 23.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a23 article 23]]] | [[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 23.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a23 article 23]]] | ||

The problem of reservations is a simple matter of possible consent. There are treaties where it is not difficult to know who must consent. In the case of a bilateral treaty, it is clear that mutual consent is necessary. Finding a common denominator between 194 states is difficult, even "diabolical". | |||

So we can negotiate, but then we will arrive at a time when nothing goes wrong, because we can always question it. Now there is the question of some dissatisfied states, some will disagree radically. There are States that will say that the compromise we have arrived at and acceptable, but there are a few articles that are not even essential, which are a huge problem that could be contrary to constitutional law or a political problem, for example. | |||

=== The question arises as to what to do with States that say they could ratify only if they could make an exception? === | |||

The problem is to find a consensus between protecting the integrity of the treaty or promoting the universality of the treaty. | |||

If one is in favour of the integrity of the treaty, the treaty as such cannot be subject to reservations. If, on the other hand, the universality of the treaty is favoured, it is impossible to agree on everything. The idea was to ensure greater ratification by releasing ballast on articles, especially since States could withdraw their reservations afterwards. | |||

Before the Second World War, the universal rule was that of the integrity of treaties, we accepted all or nothing, we could make a reservation only if all States agreed. After 1945, the rule was to favour the universality of treaties by admitting reservations. Today, the general rule is to be able to make reservations to conventions. | |||

It is generally said that these must be multilateral and not bilateral conventions. Practice, however, shows that reservations have taken place in bilateral treaties. What can be said is that it is certain that reservations apply to multilateral treaties. In a multilateral treaty, agreement must be reached. | |||

The second important thing to know is that reservations must be made at the latest at the time of signature or ratification. At the time of ratification and accession, one gives one's final consent to be bound by the treaty, other contractors must know what one is obliged to do and what one is not. A State that no longer wishes to implement a particular article would mean that the convention would no longer be binding on States overriding the adage pacta sunt servanda. In the case of reservations, other participants may object. That does not mean that we cannot make reserves later. This is the case if there is an agreement between all States, there is no reason why it is prohibited. | |||

=== What is a reservation? === | |||

In order to know this, one must go to the definition of the terms used in Article 2 §1 (d) of the Vienna Convention: Reservation "means a unilateral declaration, whatever its wording or designation, made by a State when it signs, ratifies, accepts, approves or accedes to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude or modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to that State. | |||

The reserve is distinguished by the following elements: | |||

* It is a unilateral declaration; each State, when ratifying or acceding to the treaty, can at the same time formulate a reservation. | |||

* The reservation is formulated at that time in the formulation of ratification sent to the depositary, which will notify it including the reservation to the other High Contracting States, including the signatories. | |||

* The purpose and effect of the reservation is to exclude or modify the legal effect, so provision X or Y will not apply according to the terms written in the treaty. The substance of these provisions is being changed; it will not apply in the substance of the treaty; it can either exclude the application of this provision to it or slightly modify an article in its own respect, since it assures part of the obligations, but accepts another. The treaty will not apply in the same way as if the reservation had not been made. | |||

Interpretative declarations, which States often make when ratifying or acceding to a treaty. In principle, these are declarations that are not intended to modify the substance of the treaty or to seek ratification so that the State can make known its understanding of the convention or make political declarations. The true interpretative declaration is to say how the provision is understood. | |||

In theory, it is clear that the interpretative declaration merely casts a certain light on the article, but remains the same, although States sometimes play with it, they make disguised reservations, do not dare to make open reservations either for legal or political reasons. Sometimes interpretative declarations are reservations. It must be said that it is not the label that counts, it is not because the State is going to send its position in the form of a reservation or an interpretative declaration. The question is sometimes subtle, depending on the interpretation of the text by the State, but also on the interpretation of the text of the treaty. If it bites on the substance, it's a reserve. | |||

=== When are reservations eligible? === | |||

The current regime provided for by the 1969 Vienna Convention in articles 19 to 23 is a liberal regime under which a State may make as many reservations as it wishes, there is the presumption and freedom to make reservations. There is no formal limit, it is a common sense limit, if a State has too many problems with a treaty it will not ratify it. | |||

There are, however, some rules on the admissibility of reservations and in particular some of them are covered by treaty law and others by general international law. | |||

By conventional law, we mean that, on the basis of a convention, we want to know whether we want to make reservations. The first thing to do to avoid the issue is to say that the treaty itself may have provisions on the issue to be followed; the contracting parties have been able to make provision. If in the Treaty there is nothing, in other Treaties there are things; we must follow them: | |||

* '''treaties which completely prohibit reservations''': the Contracting Parties considered that the integrity of the treaty weighed more heavily than the universality of ratification. Interpretative declarations, but not reservations, can be made. | |||

* '''prohibition of reservations on certain provisions''': this will define a hard core of the most important provisions on which reservations cannot be made. Reservations are prohibited on certain articles, a contrario, they are allowed on the other provisions. Negotiators are of the opinion that certain articles are essential to the convention. For example, article 12 of the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf. | |||

* '''Reservations are permissible for certain articles''', i. e. reservations are prohibited on all other provisions. This latter version is generally more subtle, the convention is more locked. | |||

* '''provisions which prohibit certain materially defined reservations''': reservations having certain qualities such as, for example, in the former Human Rights Convention to article 64, which prohibits reservations of a general nature that are considered non-intelligible. There are conventions which prohibit certain types of reservations, particularly those that are not specific. | |||

We are authorized to make reservations that are authorized by the treaty. This is the rule of consent and willingness. | |||

Irrespective of what the parties had intended, and particularly in treaties such as the Vienna Convention, States could make reservations in principle unlimited. There is a problem with the general law: States can make reservations as they wish. That is why there are limits to reservations in general law: | |||

*r'''elative limits (Article 20 § 2 and § 3)''': in institutional treaties, it is difficult to make reservations, for example, the United Nations, as an institution must operate according to equal rules for all. | |||

*'''limit of the object and purpose of the treaty as provided for in article 19 of the Vienna Convention letter c)''': it is not an easy or straightforward application, since one can legitimately have different views on the object and purpose of the treaty.But what is easily understandable is that in a multi-party treaty which contains many provisions, not all of them are of equal importance, some are eminent and others are secondary provisions of an administrative or other subordinate nature; it is not possible to place reservations on articles essential to the proper functioning of the convention while reservations on secondary provisions are permitted. Deciding what is relevant to the object or purpose is sometimes obvious and sometimes not easy. We can have quite legitimately divergent views. | |||

The case that is legally very clear is the "Shariah" type of reservations, also known as "reservations of internal tradition". A Djibouti reservation to the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 states that " [The Government of the Republic of Djibouti will not consider itself] bound by provisions or articles incompatible with its religion and traditional values". | |||

This reservation is of a general nature and does not relate to a specific provision, it potentially concerns all the provisions of the treaty, and moreover, it is of an absolutely indeterminate nature, since no one other than Djibouti knows its religion and traditions, which means that Djibouti does not have to assume any obligation. This is not inconsistent with any convention; we reserve the right to apply or not to apply a provision on the basis of tradition and religion, which only Djibouti knows. This is incompatible with the adage pacta sunt servanda, reserving the application of an agreement is contrary to the object and purpose of any contractual commitment. In that case, it would simply have been necessary not to ratify the Convention. In fact, a whole series of States have made an objection to this reservation. | |||

=== Why do these States ratify when they have problems with this type of convention? === | |||

The problem is not legal in this respect, it is that these human rights conventions have become so much a religion for Western countries that everyone has to ratify them. This somewhat unfortunate situation leads these states to ratify this convention, because it is politically necessary. In reality, they cannot apply these conventions contrary to their internal traditions. It's politically sensitive, but not legally. | |||

Another case is a delicate one, the reservations made by the socialist states in the late 1940s and early 1950s with regard to the 1948 genocide convention. This reservation concerns Article IX, in the event of a dispute concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention, each State Party to this Convention is a party to disputes concerning another State may bring the dispute before the International Court of Justice. It is an arbitration clause that allows in the event of a dispute to bring it before the International Court of Justice. | |||

The Socialist Republics agreed to sign the convention, but not to recognize the international tribunal. The communist countries never had the majority of judges in court is no chance to impose their vision of international relations. For these States, it was out of the question to submit to the court. At the same time, these States absolutely wanted to become party to it for the same political reasons as in the previous example. It was vital to be bound by the Convention, but not by Article IX. | |||

=== | === Is it contrary to the object and purpose? === | ||

For socialist states, what counts in the convention is the substantial conditions and repression of genocide. The object and purpose are therefore linked to genocide and the substantive provisions of the Convention. | |||

=== | === Does Article IX appeal to the procedure? === | ||

This is a non-essential procedural issue. | |||

The Westerners in the late 1940s argued that the convention against genocide was not a convention against others, it was not limited to designating a crime and organising repression. There was a provision in the convention that allowed the convention to be applied. This convention by virtue of Article IX is not a paper rag convention. The guarantee clause in Article IX is essential to the realisation of the object and purpose of the Convention. | |||

The two arguments are plausible, the choice between the two is not obvious; for a long time there was uncertainty about the admissibility of the Soviet reserve and the effects to be attached to it. | |||

The issue had meanwhile been resolved, as other States had formulated the same reservation and that practice had become widespread. Thus, for Westerners, this reserve is not so bad, the practice is that this reserve is admissible. The Court still applies this reservation. | |||

=== In summary, what happens if there is disagreement about the acceptability and validity of the reservation? === | |||

First of all, it will be necessary to ascertain whether there are agreements and whether there are objections to the reservation. If there is no objection to the reservation and States expressly accept it, then this means that reservations to those States do not pose any problems. We can therefore proceed as if the reservation were valid even if it is not true. | |||

If we have objections, we have a potential dispute. At that time, we do not know how to apply the treaty. As long as there is no particular problem, we move forward and the dispute can be dormant. As long as there are no disputes, it is not very important to know whether the reservation to article IX is valid or not. However, we won't be able to test it, because we don't have a case. If we have a case, we have a dispute about the applicability of the convention; we will have to engage in procedures for the peaceful settlement of disputes. | |||

Finally, the effects. The setbacks are decided on the basis of the treaty and, if not, on the basis of Articles 19 and 20 of the Vienna Convention. | |||

Assuming we have valid reservations, what are their effects? | |||

The general effect of the reservation is to fragment the treaty into a bundle of bilateral relations. Contrary to the option that exists, there is in reality a plurality of treaties according to the reservations and the reactions of other States to those reservations, so the treaty is fragmented according to bilateral relations. Thus it will apply differently depending on the States parties to the treaty. We have to look at the reports of each state, there are potentially many relations. | |||

A silent state that does not react, in this case if the situation were not regulated there would be legal certainty that would last too long. According to Article 20 §5, after one year silence is considered acceptance; it is a legal fiction, acceptance is imputed to the silent state. A State that does not wish to accept a reservation, if it does not object, after a certain period of time has elapsed, will be understood that it has accepted. After 12 months the position will be clear. During the twelve months, the situation is in abeyance. | |||

=== | === Assuming we have valid reservations, what are their effects? === | ||

The general effect of the reservation is to fragment the treaty into a bundle of bilateral relations. Contrary to the option that exists, there is in reality a plurality of treaties according to the reservations and the reactions of other States to those reservations, so the treaty is fragmented according to bilateral relations. Thus it will apply differently depending on the States parties to the treaty. We have to look at the reports of each state, there are potentially many relations. | |||

A silent state that does not react, in this case if the situation were not regulated there would be legal certainty that would last too long. According to Article 20 §5, after one year silence is considered acceptance; it is a legal fiction, acceptance is imputed to the silent state. A State that does not wish to accept a reservation, if it does not object, after a certain period of time has elapsed, will be understood that it has accepted. After 12 months the position will be clear. During the twelve months, the situation is in abeyance.[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 20.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a20 article 20]]] | |||

[[Fichier:Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969 - article 20.png|vignette|center|700px|[http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/francais/traites/1_1_1969_francais.pdf Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités de 1969] - [http://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/19690099/index.html#a20 article 20]]] | |||

=== | === If there is an objection to a reservation that it is the effect of the reservation? === | ||

Il y a deux distinctions à faire qui sont superposées : | Il y a deux distinctions à faire qui sont superposées : | ||

1) | 1) it is an option given by the Vienna Convention and by practice to the objecting State: if it is stated that a reservation is not intended to be applied to a particular article and that a State objects, a choice must be made: | ||

*'''objection | * '''simple objection''': do we want to apply the provisions of the convention on which there is no dispute? The reservation is opposed to the reservation, which entails the consequence that the reservation to the article will not be applicable. However, if there is no difference of opinion, we are not opposed to implementing the treaty. | ||

*'''objection | * '''Radical objection''': the article was so important that a State refused to apply the agreement between it and the reserving State. As long as the provision is retained, the convention will not be enforced. | ||

The effect of an objection will be, depending on the circumstances, to allow the treaty to apply except in the case of an objection to a reservation, or that a provision of the treaty will not be applicable from then on, there will be no treaty relationship between the States wishing to make the reservation and the objecting State. | |||