« Externalities and the role of government » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 219 : | Ligne 219 : | ||

These policies aim to align private incentives with social benefits or costs, so that economic activities more accurately reflect their true cost or value to society. By carefully adjusting these interventions, the state aims to achieve an allocation of resources that maximises social well-being. | These policies aim to align private incentives with social benefits or costs, so that economic activities more accurately reflect their true cost or value to society. By carefully adjusting these interventions, the state aims to achieve an allocation of resources that maximises social well-being. | ||

= | = Private Approaches to Managing Externalities = | ||

== The Coase Theorem == | |||

The Coase Theorem, formulated by the economist Ronald Coase, offers an interesting perspective on how externalities can be managed by the market without government intervention. According to this theorem, if property rights are clearly defined and transaction costs are negligible, the parties affected by the externality can negotiate with each other to reach an efficient solution that maximises total welfare, regardless of the initial distribution of rights. In this context, property rights are the legal rights to own, use and exchange a resource. A clear definition of these rights is essential because it determines who is responsible for the externality and who has the right to negotiate about it. For example, if a property right is granted to a polluter, the parties affected by the pollution (such as local residents) should theoretically negotiate with the polluter and potentially compensate him for reducing the pollution. Conversely, if local residents have the right to enjoy a clean environment, the polluter should compensate them for continuing to pollute. | |||

Coase's theorem also indicates that the efficient allocation of resources will be achieved whatever the distribution of property rights, as long as the parties can negotiate freely. This means that the parties will continue to negotiate until the cost of the externality to the polluter is equal to the cost to society. The essence of this proposition is that the end result (in terms of efficiency) should be the same regardless of who initially holds the rights, a principle known as Coase invariance. However, in practice, the conditions required for the application of Coase's theorem are often not met. Transaction costs may be significant, property rights may be difficult to establish or enforce, and the parties may not have complete or symmetrical information to negotiate effectively. Furthermore, when many parties are involved or the effects of an externality are diffuse and not localised, the coordination required to negotiate private agreements becomes extremely complex. | |||

In these situations where the conditions of Coase's theorem are not met, state intervention through regulations, taxes or subsidies may be necessary to achieve an allocation of resources that reflects the social cost or benefit of the externalities. This helps to ensure that externalities are internalised, leading to a solution that is closer to the social optimum. | |||

The problems you have raised are major challenges when it comes to solving externalities by market means or private solutions, as described in Coase's theorem. | |||

Problem I - High Transaction Costs: Transaction costs include all the costs associated with negotiating and executing an exchange. In the case of externalities, these costs may include the costs of finding information about the affected parties, the costs of negotiating to reach an agreement, the legal costs of formalising the agreement, and the monitoring and enforcement costs of ensuring that the terms of the agreement are respected. When these costs are prohibitive, the parties cannot reach an agreement that would internalise the externality. As a result, the market alone fails to correct the externality, and external intervention, such as by the state, may become necessary to facilitate a more efficient solution. | |||

Problem II - Free-Rider Problem: The free-rider problem is particularly relevant in the case of public goods or when positive externalities are involved, such as environmental protection or vaccination. If a good is non-excludable (it is difficult to prevent someone from benefiting from it) and non-rival (consumption by one person does not prevent consumption by another), individuals may be encouraged not to reveal their true value of the good or service in the hope that others will pay for its provision while themselves enjoying the benefits without contributing to the cost. This leads to under-provision of the good or service as everyone expects someone else to pay for the positive externality, resulting in less than the socially optimal quantity being produced. | |||

These two problems illustrate why markets can often fail to resolve externalities on their own and why government intervention may be necessary. The state can help reduce transaction costs by introducing laws and regulations that facilitate private agreements, and it can overcome the free-rider problem by supplying public goods itself or subsidising their production to encourage provision closer to the social optimum. | |||

== The Power of Private Negotiation and the Definition of Property Rights == | |||

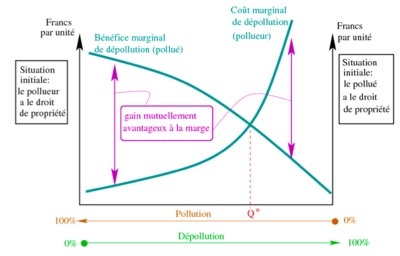

This graph illustrates a negotiation situation between a polluter and a polluted party concerning pollution abatement, in the context of Coase's theorem. The graph shows two curves: the marginal cost of clean-up for the polluter and the marginal benefit of clean-up for the polluted. | |||

[[Fichier:Négociation privée et droits de propriété 1.png|400px|vignette|centré|NB: the socially optimal level of pollution is not zero!]] | |||

This graph illustrates an economic approach to solving the problem of negative externalities by means of negotiations between parties, in accordance with Coase's theorem. It describes a situation where a polluter and a party affected by the pollution, the polluted party, are involved in a negotiation aimed at finding a level of pollution abatement that maximises collective well-being. | |||

In this representation, the cost to the polluter of reducing pollution, or depolluting, increases with each additional unit of depollution undertaken. This is represented by the rising curve, indicating that the first few units of pollution abatement are relatively inexpensive for the polluter, but that the cost increases progressively. At the same time, the benefit to the polluter of reducing pollution decreases with each additional unit. The first reductions in pollution bring great benefits to the polluter, but these benefits diminish as the air or water becomes cleaner. | |||

The point where these two curves cross, marked Q∗, represents the level of pollution abatement where the marginal benefit of cleaning is exactly equal to the marginal cost of cleaning. This is the ideal level of clean-up from the point of view of economic efficiency, as it perfectly balances the marginal cost and benefit of clean-up. | |||

The framework provided by the graph suggests that, regardless of who initially holds the property rights, whether the polluter or the polluted, there is an opportunity for a mutually beneficial agreement. If the polluter has the right to pollute, the polluted can potentially compensate the polluter financially for reducing pollution, to the point where it is no longer advantageous for the polluted to pay for additional pollution abatement. Conversely, if the polluted party holds the right to a clean environment, the polluter could pay for the right to pollute, until the additional cost of reducing pollution outweighs the benefits to the polluter. | |||

However, in reality, negotiations between the polluter and the polluted are often hampered by high transaction costs. These costs can include the legal costs of establishing and enforcing agreements, the costs of information gathering and negotiation, and the challenges of coordinating a large number of parties. In addition, information asymmetries and the free-rider problem, where individuals benefit from bargaining outcomes without actively participating, can also complicate the private resolution of externalities. | |||

As a result, although Coase's theorem offers an elegant solution on paper, the need for state intervention in the form of environmental regulations or taxes is often unavoidable in order to manage externalities effectively and achieve an allocation of resources that reflects the social cost and benefit of depollution. | |||

== Illustration Pratique: Un Accord Négocié en Détail == | == Illustration Pratique: Un Accord Négocié en Détail == | ||

Version du 8 janvier 2024 à 15:24

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami[1][2][3]

Microeconomics Principles and Concept ● Supply and demand: How markets work ● Elasticity and its application ● Supply, demand and government policies ● Consumer and producer surplus ● Externalities and the role of government ● The costs of production ● Firms in competitive markets ● Monopoly ● Oligopoly ● Monopolisitc competition

The notion of the "invisible hand" described by Adam Smith is a central concept in economics, reflecting the idea that individual actions motivated by self-interest can lead to beneficial results for society as a whole. However, this idea is based on the assumption of perfect competition, which is rarely achieved in practice.

In the real world, the market is often imperfect and subject to various dysfunctions, notably due to the existence of externalities. Externalities are the effects that economic transactions have on third parties who are not directly involved in the transaction. These effects can be positive or negative.

A classic example of a negative externality is pollution: a factory that pollutes the air or water harms the environment and public health, but these costs are not factored into the price of its products. Conversely, an example of a positive externality might be vaccination: by getting vaccinated, a person reduces the risk of transmitting diseases to others, thereby benefiting society.

When externalities are present, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently, leading to what is known as "market failure". In such situations, state intervention may be justified to correct these failures. This can be done through regulations, taxes (such as the carbon tax on polluters) or subsidies (to encourage activities that generate positive externalities).

Understanding Externalities and their Impact on Market Efficiency

Clarification of Terms: Externalities Explained

An externality occurs when an action by an individual or a firm has a direct impact on the welfare of a third party without this impact being compensated or regulated by the market price system. This concept is crucial in economics as it represents one of the main market failures.

There are two main types of externalities:

- Negative Externalities: These occur when the action of an individual or company has a negative impact on a third party. A classic example is pollution: a company that emits pollutants into the atmosphere affects the health and quality of life of people living nearby, but these costs are not reflected in the price of its products.

- Positive Externalities: Conversely, a positive externality occurs when the action of an individual or company benefits others without them paying for the benefit. For example, the planting of trees by an individual may improve the air quality and aesthetics of the neighbourhood, benefiting all the residents of the area without them contributing financially to the planting.

The problem with externalities is that they can lead to a sub-optimal allocation of resources. In the case of negative externalities, they can lead to overproduction or overconsumption of the goods that generate these externalities. Conversely, positive externalities can lead to under-production or under-consumption of the goods that generate them, because producers are not compensated for the benefits they provide to society.

To correct these inefficiencies, state intervention is often necessary. This can take the form of regulations, taxes for negative externalities, or subsidies to encourage activities that generate positive externalities. For example, a carbon tax aims to internalise the environmental costs of pollution, by making polluters pay for the impact of their emissions.

Negative externalities take many forms and have a considerable impact on society and the environment. Take the example of cigarette smoke, often cited for its secondary effects on non-smokers. People exposed to passive smoke suffer increased risks of respiratory and cardiovascular disease, even though they have not chosen to be exposed to these dangers. Another striking example is car exhaust fumes. Air pollution from car traffic affects public health and the environment, even for those who make little or no use of their vehicles. This illustrates how individual transport choices can have widespread and unintended consequences. In urban and residential areas, problems such as dogs barking excessively or leaving faeces on pavements also constitute negative externalities. These behaviours cause inconvenience to residents, ranging from noise nuisance to an increased need for cleaning and maintenance of public spaces. Noise nuisance in general, whether from industry, construction work or leisure activities, is another source of negative externality. It can disrupt daily life, affecting the well-being, sleep and mental health of people living or working nearby. A less obvious but equally important example is antibiotic resistance, exacerbated by the overuse of drugs. Excessive use of antibiotics causes pathogens to adapt, making treatment less effective for the whole population, not just those taking the drugs. Finally, environmental pollution or degradation in various forms - such as the dumping of industrial waste, deforestation or greenhouse gas emissions - has major negative repercussions. These activities damage ecosystems, affect human and animal health, and contribute to climate change, with effects often felt far beyond the immediate areas of impact. These examples highlight the need for government intervention to regulate activities that generate negative externalities. Solutions can include regulations, taxes to discourage harmful behaviour, or awareness campaigns to inform the public of the consequences of certain actions. By proactively addressing these issues, societies can better manage the unwanted side-effects of certain activities and promote a healthier, more sustainable environment for all.

Positive externalities, where the actions of one person or company benefit others without direct compensation, play a crucial role in the economy and society. Your examples illustrate this dynamic well. Take, for example, the phenomenon of a car being sucked up by a lorry on the motorway. When a lorry is travelling at high speed, it creates a wake of air that can reduce wind resistance for the following vehicles, thereby improving their fuel efficiency. Although this is not the truck driver's main intention, it benefits other drivers by reducing their fuel consumption. Vaccines are a classic example of a positive externality. When people are vaccinated, they not only protect themselves against certain diseases, but also reduce the likelihood of these diseases being transmitted to others. This herd immunity benefits the whole community, especially those who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons. The restoration of historic buildings or any activity that attracts tourists also brings significant benefits to the local community. These projects not only increase the aesthetic appeal of an area, but also stimulate the local economy by attracting visitors who spend money in hotels, restaurants and other local businesses. Another fascinating example is the interaction between an orchard and the hives of a neighbouring beekeeper. The beekeeper benefits from the presence of the orchard, as his bees find an abundant source of nectar, improving the quality and quantity of their honey. In return, the orchards benefit from pollination by the bees, which is essential for fruit production. It's a fine example of symbiosis where both parties mutually benefit from their respective activities. Finally, research into new technologies is often a source of positive externalities. Innovations and discoveries can benefit society as a whole by improving quality of life, introducing new solutions to existing problems and stimulating economic growth. Often, the benefits of such research far outweigh the direct spin-offs for the researchers or the organisations that fund them. These examples illustrate the importance of positive externalities in our society. They also highlight the role that government intervention, for example by subsidising or supporting activities that generate such externalities, can play in maximising collective well-being.

The Consequences of Externalities on the Market Economy

Externalities, whether positive or negative, create a mismatch between private costs and benefits and social costs and benefits, leading to market inefficiencies.

In the case of negative externalities, the external costs of production or consumption are not taken into account by producers or consumers. For example, a factory that pollutes does not pay for the environmental and health damage that its pollution causes. This leads to an overproduction of polluting goods, because the market price does not reflect the true social cost of these products. In other words, if external costs were internalised in the price of the product, the cost would be higher, reducing demand and bringing production into line with a more socially optimal level.

For positive externalities, the scenario is reversed. The benefits that the actions of an individual or a company bring to society are not financially compensated. Take the example of vaccination: individuals who are vaccinated not only protect themselves, but also reduce the risk of spreading disease within the community. However, this external benefit is not reflected in the price of the vaccine. As a result, fewer people choose to be vaccinated than would be ideal from a social point of view. If the external benefits were taken into account, vaccination would be more attractive, and the level of vaccination in society could move closer to the social optimum.

Left to their own devices, markets tend to produce an excessive quantity of goods or services generating negative externalities and an insufficient quantity of those generating positive externalities. To correct these inefficiencies, interventions such as taxes (for negative externalities) or subsidies (for positive externalities) are often necessary to align private costs and benefits with social costs and benefits.

The example of the aluminium market is a perfect illustration of how negative externalities can affect the total social cost of production. In this case, the pollution generated by aluminium plants represents an external cost that is not initially taken into account when calculating the cost of producing aluminium. The private cost of production is the cost that the aluminium producer must bear directly to manufacture the product. This cost includes items such as raw materials, labour, energy, equipment maintenance and other operating expenses. These are the costs on which the company bases its selling price and profitability.

However, if aluminium plants pollute, there are external costs that affect other parts of society. These external costs can include adverse effects on public health, damage to the environment, reduced quality of life, and other negative impacts that are not reflected in the price of aluminium. For example, pollution can lead to additional health costs for the community, environmental clean-up and restoration costs, and a loss of biodiversity. The social cost of aluminium production is therefore the sum of the private cost of production (the cost borne by producers) and the external cost (the costs incurred by society as a result of pollution). This addition shows that the market price of aluminium, based solely on the private cost, is lower than the true social cost of its production.

This discrepancy leads to an overproduction of aluminium compared to what would be produced if external costs were included, which is a typical example of market inefficiency due to negative externalities. To correct this, measures such as imposing an environmental tax on the pollution produced by aluminium plants could be introduced. This tax would aim to internalise external costs, thereby aligning the private cost with the social cost and leading to production that is closer to the social optimum.

Social cost = private cost of production (supply) + external cost

Here's a closer look at this equation:

- Private Cost of Production: These are the costs that the aluminium producer has to bear to make the product. This includes expenditure on raw materials, labour, energy, equipment and other operational costs. These costs determine the price at which the company is willing to offer its product on the market.

- External cost: These are the costs incurred by the company that are not taken into account by the producer. In the case of aluminium, if production involves pollution, external costs may include impacts on public health, the environment, quality of life and other aspects that are not reflected in the market price of aluminium. These costs are often diffuse and difficult to quantify precisely, but they are real and significant.

- Social cost: The social cost is the sum of the private cost of production and the external cost. It represents the total cost to society of aluminium production. This social cost is higher than the private cost of production due to the addition of external costs.

When social costs are not factored into production and consumption decisions, this leads to overproduction of aluminium compared with what would be socially optimal. In other words, more aluminium is produced than would be the case if the costs of pollution were taken into account. This situation is a classic example of market failure due to negative externalities. To remedy this, public policies can intervene, for example by imposing pollution taxes so that producers internalise these external costs, or by imposing environmental regulations to limit pollution. The aim of these interventions is to ensure that the private cost more closely reflects the social cost, leading to a more efficient allocation of resources from society's point of view.

Pollution and Social Optimum Analysis

In an economic framework, the intersection of the demand and social cost curves is crucial to understanding how to achieve an efficient equilibrium that takes account of both private interests and social impacts.

Here's how it works:

- Demand curve: The demand curve reflects the willingness of consumers to pay for different quantities of a good or service. It shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded, usually with an inverse relationship: as the price rises, the quantity demanded falls, and vice versa. # Social Cost Curve: The social cost curve encompasses both the private cost of production (the direct costs incurred by the producer) and the external costs (the uncompensated costs incurred by society as a result of producing the good). For example, in the case of aluminium, this would include the costs of production plus the environmental and public health costs associated with pollution. # Intersection for Optimal Quantity: When the demand curve intersects the social cost curve, this indicates the optimal quantity of the good from the point of view of society as a whole. At this point, the price that consumers are prepared to pay corresponds to the total cost (private + external) of producing the good. This quantity is different from the one that would be reached if only the private cost were taken into account, because it incorporates the total impact on society.

If markets only take private costs into account, there will be a tendency for overproduction (in the case of negative externalities) or underproduction (in the case of positive externalities) in relation to this optimal quantity. This is why interventions such as taxes (to internalise external costs) or subsidies (to encourage the production of goods generating positive externalities) may be necessary to align market quantities with socially optimal quantities.

This approach aims to achieve an equilibrium where production and consumption choices reflect not only private costs and benefits, but also the costs and benefits to society as a whole.

The distinction between the market equilibrium quantity and the socially optimal quantity is a key point in economics, particularly when considering the impact of externalities.

- Market Equilibrium Quantity: In a free market without external intervention, equilibrium occurs at the point where the private cost of production (the cost to the producer) equals the private profit (the price consumers are willing to pay). At this equilibrium point, the quantity of goods produced and the quantity demanded by consumers are equal. However, this equilibrium does not take into account the external costs or benefits that affect society as a whole.

- Socially Optimal Quantity: The socially optimal quantity, on the other hand, occurs at a level of production where the social cost (which includes private costs and external costs) is equal to the social benefit (which includes private benefits and external benefits). This quantity takes into account the total impact on society, not just on direct producers and consumers.

In the case of negative externalities, such as pollution, the social cost of production is higher than the private cost. As a result, the socially optimal quantity is generally lower than the market equilibrium quantity. This means that reducing production to the socially optimal quantity would reduce external costs (such as environmental damage) and would therefore be more beneficial for society as a whole. To achieve this socially optimal quantity, policy interventions such as pollution taxes (to internalise external costs) or regulations (to limit the quantity produced) may be necessary. These interventions aim to align private interests with social interests, ensuring that the costs and benefits to society are taken into account in production and consumption decisions.

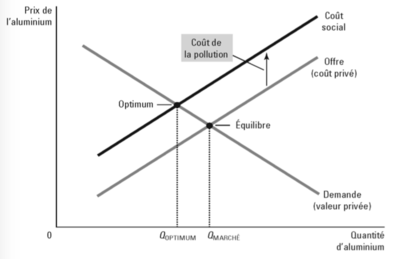

This graph represents a classic economic graph illustrating the concepts of market equilibrium and social optimum in the context of aluminium production and its negative externalities, in particular pollution.

On the horizontal axis, we have the quantity of aluminium produced, and on the vertical axis, the price of aluminium. Three curves are drawn:

- The demand curve (private value): This shows the relationship between the price consumers are prepared to pay and the quantity demanded. It is decreasing, which means that the lower the price, the higher the quantity demanded, and vice versa. # The supply curve (private cost): This represents the cost to producers of producing aluminium. It rises, indicating that the greater the quantity produced, the higher the cost of production (and therefore the selling price).

- The social cost curve: This curve is above the supply curve and represents the total cost of aluminium production, including the cost of pollution. The social cost is higher than the private cost because it takes into account the negative external effects of pollution on society.

The point where the demand curve crosses the supply curve (private cost) is the market equilibrium point (QMARCHEˊ). This is where the market, in the absence of regulation, tends to stabilise: the quantity that producers are prepared to supply at the market price equals the quantity that consumers are prepared to buy.

However, this equilibrium point does not take into account the cost of pollution. If we include the cost of pollution, we obtain the social cost curve, which intersects the demand curve at a different point, marked "Optimum". This social optimum point (QOPTIMUM) represents the quantity of production that would be ideal if external costs were taken into account. At this quantity, the total cost to society (including the cost of pollution) is equal to the price that consumers are prepared to pay.

What is notable about this graph is the difference between Q MARKET and Q OPTIMUM. The quantity produced at the market equilibrium point is higher than the socially optimal quantity, which implies that the market itself produces more aluminium than would be socially desirable because of external costs not taken into account (pollution). To reduce aluminium production from Q MARKET to Q OPTIMUM, political interventions such as pollution taxation, the introduction of quotas or environmental regulations may be necessary. In short, this graph clearly illustrates the implications of negative externalities on market efficiency and highlights the importance of regulatory intervention to achieve a level of production that is in harmony with social interests.

Impact of Negative Externalities on Society

A negative externality is a cost incurred by a third party who is not directly involved in an economic transaction. This means that part of the production costs are not borne by the producer or consumer of the good or service in question, but by other members of society. Negative externalities tend to reduce overall well-being, because the social costs of these economic activities are higher than the private costs.

Let's take a concrete example: a factory that produces aluminium emits pollutants into the atmosphere. These emissions have consequences for public health, such as respiratory illnesses, and for the environment, such as damage to the ecosystem. These additional costs to society, which can include increased medical costs and loss of biodiversity, are not reflected in the price of aluminium. If the plant does not pay for these external costs, it has little incentive to reduce pollution and may even produce aluminium at an artificially low cost, leading to overproduction and overconsumption of the metal.

From a welfare perspective, this creates a problem. Members of society suffer damage that they did not choose and for which they are not compensated. As a result, overall well-being is lower than it could be if these external costs were taken into account.

Economic theory and public policy seek to resolve this problem of negative externality through various interventions:

- Taxation of polluting activities: Taxes can be imposed on pollution to encourage companies to reduce their emissions. These taxes aim to internalise the external cost, which means that the producer will have to take the cost of pollution into account in its production decisions.

- Environmental regulations and standards: Laws can be put in place to directly limit the amount of pollution that a company can emit, thus forcing companies to adopt cleaner technologies or change their production processes.

- Emissions trading markets: In some cases, it is possible to create markets where companies can buy and sell rights to pollute, thereby achieving pollution reductions at the lowest cost.

These measures aim to reduce negative externalities and, as a result, improve society's well-being by ensuring that the social and private costs of production are better aligned. By incorporating the cost of pollution into the price of goods and services, businesses and consumers can make more informed decisions that reflect the true cost of their activities, leading to a more efficient and equitable outcome for society as a whole.

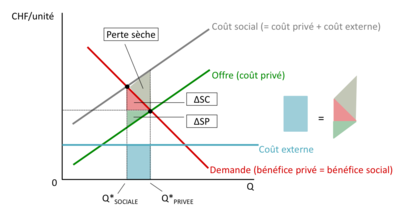

This is an economic graph detailing the effects of negative externalities on well-being in a market, in this case the hypothetical market for a good measured in Swiss francs per unit. The downward sloping demand curve shows the value that consumers place on different quantities of the good, reflecting the private and social benefits associated with its consumption. At the same time, the upward sloping supply curve reflects the private cost incurred by producers in supplying each additional unit of the good. Normally, in a market without externalities, equilibrium would be found at the intersection of these two curves, marking the quantity where private cost equals private benefit.

However, when we take into account external costs, such as pollution or other damage to society not included in the cost of production, a new curve, the social cost curve, is introduced. This curve, positioned above the supply curve, integrates these external costs into the private cost, showing the true cost to society. The intersection of this curve with the demand curve then marks the socially optimal quantity of the good, which is less than the market equilibrium quantity.

The graph highlights an area of deadweight loss, represented by a hatched area between the market equilibrium and socially optimal quantities. This dry loss symbolises the economic welfare lost as a result of production in excess of the social optimum. It is the value of the units produced in excess that society would have preferred not to produce if all the costs, including those of pollution, had been taken into account. This loss is a market inefficiency because it represents a cost to society that is not offset by an equivalent gain elsewhere in the economy.

The blue band at the bottom of the graph shows the external cost, which remains the same for each unit produced, regardless of the number of units. This external cost, constant per unit, is not reflected in the private cost of production and must be taken into account when assessing the total impact on society.

The graph clearly shows that without intervention, a market can operate inefficiently, producing more than is socially desirable because external costs are not taken into account. This leads not only to harmful overproduction but also to a sub-optimal allocation of society's resources. This is why policies such as pollution taxation are often proposed to realign production with the social optimum, thereby reducing deadweight loss and increasing collective well-being. These measures aim to make producers responsible for the costs they impose on society, encouraging production that is more respectful of the environment and more in line with the interests of society as a whole.

The Impact of Education as a Positive Externality

In the context of externalities and social well-being, determining the optimal quantity of a good or service to produce and consume takes into account not only private benefits and costs but also external benefits and costs to society. When we talk about social benefit, we are referring to the sum of private benefits, which are the direct benefits for the consumers and producers involved in the transaction, and external benefits, which are the unaccounted benefits that accrue to third parties not directly involved in the economic exchange.

The intersection of the social benefit curve and the cost curve reflects the point at which collective well-being is maximised. At this point, the last unit produced brings as much additional benefit to society as it costs to produce it. This is what we call the socially optimal quantity. This contrasts with the market equilibrium point, which takes account only of private benefits and costs and ignores external effects.

For goods that generate positive externalities, such as vaccination or education, the social benefit curve would be higher than the private benefit curve, suggesting that the socially optimal quantity is greater than what the market would produce on its own. This often justifies incentives or subsidies to increase the production and consumption of these goods to the socially optimal level.

Conversely, for goods that generate negative externalities, such as pollution from industrial production, the social cost curve is higher than the private cost curve. This implies that the quantity produced at market equilibrium exceeds the socially optimal quantity, because producers and consumers do not take external costs into account in their decisions. In this case, interventions such as Pigouvian taxes or regulations are needed to reduce production to a level that reflects the true costs to society.

The point of intersection between social benefit and cost reflects the optimal trade-off between the benefits of goods and services and their cost of production, including externalities. Reaching this point often requires active political action to correct market failures and align private incentives with social objectives.

The socially optimal level of production relative to the market equilibrium quantity depends on the nature of the externality concerned.

For goods with positive externalities, the socially optimal level of production is often higher than the market equilibrium quantity. This is because the social benefits of an additional unit of the good are greater than perceived by consumers and producers. As a result, the market, left to its own devices, does not produce enough of the good to maximise social welfare. Vaccinations are a classic example of this; they benefit society more than they cost to produce, but without intervention, fewer people are vaccinated than would be socially ideal, because individuals do not take into account the benefits that their vaccination brings to others.

For goods with negative externalities, the socially optimal level of production is in fact often lower than the market equilibrium quantity. This is because the social costs of an additional unit of the good (such as pollution) are higher than the producer takes into account. Without regulatory intervention or taxation, producers will produce too much of this good, exceeding the quantity that would be optimal for society.

To sum up

- Market equilibrium quantity: The quantity that producers are willing to sell is equal to the quantity that consumers are willing to buy, without taking externalities into account.

- Socially optimal quantity: The quantity at which the total cost to society (including external costs) is equal to the total benefit to society (including external benefits). For goods with positive externalities, this quantity is higher than the market equilibrium; for those with negative externalities, it is lower.

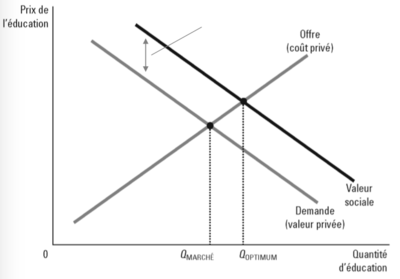

The graph you have shared represents an economic analysis of education as a good on a market, taking into account the effects of positive externalities. The supply curve, which rises, shows that providing more education costs educational institutions more, incorporating elements such as teachers' salaries, infrastructure and teaching resources. On the other hand, the falling demand curve shows that the quantity of education that individuals are prepared to consume decreases as the price rises, which is typical of most goods and services.

Where these two curves cross, we find the equilibrium quantity of the market, which is the point where the quantity of education offered corresponds to the quantity that consumers are prepared to buy. However, this equilibrium quantity does not necessarily reflect the optimal level for society as a whole due to the presence of positive externalities associated with education, such as better informed citizens, increased productivity and public health benefits that extend beyond the educated individual.

The socially optimal quantity of education is therefore assumed to be higher than the market equilibrium quantity, reflecting the full social benefit of education, which exceeds the private benefits perceived by individuals. These external benefits are not taken into account by consumers or providers when they make their decisions based solely on private costs and benefits, resulting in a sub-optimal investment in education from society's point of view.

The graph suggests that intervention, such as public policies providing subsidies or funding for education, may be required to increase the quantity of education from the market equilibrium quantity to the socially optimal quantity. These interventions are designed to reduce the cost of education to consumers or to increase supply through direct investment in educational institutions, thereby allowing society to fully realise the benefits of education that would otherwise be lost due to market failures. In sum, the graph highlights the crucial role that government intervention can play in supporting education to achieve a resource allocation that maximises social welfare.

Benefits of Positive Externalities on General Welfare

A positive externality occurs when an economic activity provides benefits to third parties who are not involved in the transaction. These third parties enjoy positive effects without having to pay for these benefits, leading to a situation where the total value of these activities for society is greater than the private value for the individuals or companies directly involved.

In the context of welfare, positive externalities are important because they can lead to under-production of the good or service in question if the market is left to its own devices. Producers do not receive payment for the external benefits they provide, so they have no incentive to produce the socially optimal quantity of that good or service.

Take education as an example: it benefits not only the student who acquires skills and knowledge, but also society as a whole. A better educated population can lead to a more skilled workforce, greater innovation, better governance and lower crime rates. These benefits are not reflected in the price of education and, as a result, without intervention, fewer resources will be allocated to education than would be ideal for society.

To address this mismatch, governments can intervene in a number of ways:

- Direct subsidies: Lowering the cost of education for students or institutions can encourage greater consumption or supply of educational services.

- Tax credits: Offering tax benefits for education costs can also encourage individuals to invest more in their education.

- Public provision: The government can provide education directly, ensuring that the quantity produced is closer to the optimal quantity for society.

When the positive externalities are properly internalised by these interventions, society's well-being improves. Individuals benefit from higher levels of consumption of the good or service, and society as a whole benefits from the positive effects that spread beyond the immediate consumers and producers. This leads to a more efficient allocation of resources and an improvement in overall social well-being.

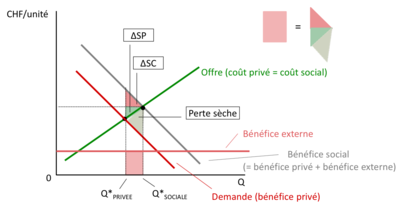

The graph you have shared represents an economic situation where a positive externality is present on the market. In this case, the social cost of production is equal to the private cost, which indicates that external costs are not significant or that negative externalities are not the focus here. On the other hand, the social benefit curve, which is the sum of private benefits and external benefits, is above the private benefit curve, indicating that the production or consumption of the good or service concerned has additional benefits for society that are not captured by the market.

The demand curve, representing the private benefit, shows the price that consumers are prepared to pay for each quantity of good or service. The social benefit curve, which is above, shows the true benefit to society, including external benefits not paid for by individuals. This could include, for example, benefits such as better public health due to increased vaccination or higher economic productivity due to a better educated population.

The market equilibrium quantity, QPRIVEˊE∗, is the point where the demand curve (private benefit) intersects supply. It is the level of output that the market would achieve without intervention. However, the socially optimal quantity, QSOCIALE∗, is higher because it takes into account external benefits. The market, by itself, does not produce enough to reach this point because producers are not compensated for the external benefits they generate.

The area of deadweight loss, indicated by the hatched area, represents the welfare that society misses out on because the good or service is not produced in the socially optimal quantity. This is market inefficiency, because if production were increased to Q∗SOCIAL, the additional social benefit (the area under the social benefit curve between Q∗PRIVEE and Q∗SOCIAL) would be greater than the additional cost of production (the area under the supply curve between Q∗PRIVEE∗ and Q∗SOCIAL).

The graph suggests that an intervention, such as subsidies or public provision of the good or service, might be required to increase production from Q∗PRIVEE to Q∗SOCIALE, thereby eliminating the deadweight loss. This would allow society to reap the full social benefits of the good or service, improving overall welfare.

Methods for Internalising Externalities

The internalisation of externalities is a central concept in economic theory which aims to resolve market inefficiencies caused by the external effects of economic activities. When externalities are present, whether positive or negative, the costs or benefits are not fully reflected in the market. The individuals or companies that generate these externalities do not incur the costs or receive the benefits associated with their actions, which leads them to make decisions that are not socially optimal.

To internalise a negative externality, we could impose a tax that reflects the external cost (such as a carbon tax on polluters), so that the private cost of the activity now includes the external cost. As a result, producers and consumers would have an incentive to reduce production or consumption of the good to a level closer to the social optimum.

Conversely, to internalise a positive externality, the state could offer subsidies or tax credits that increase private profits so that they better reflect social benefits. This would encourage greater production or consumption of the good, as in the case of vaccinations or education.

The private solution to internalising externalities, often associated with the Coase theorem, states that if property rights are well defined and transaction costs are low, the parties involved can negotiate a solution without outside intervention. For example, if a company pollutes a river and harms fishermen downstream, the fishermen could potentially pay the company to reduce the pollution or the company could pay for the damage caused. In theory, as long as the parties can negotiate and their rights are clearly established, they can reach a solution that internalises the externality and achieves efficiency.

However, in practice, the conditions required for a private solution are often difficult to achieve. Property rights may be poorly defined or difficult to enforce, and transaction costs, particularly in terms of negotiation and information, may be prohibitive. Moreover, when many agents are affected, as is often the case with environmental pollution, coordination between all the agents becomes virtually impossible without some kind of collective intervention. Internalising externalities through modified incentives is crucial to achieving an allocation of resources that is not only efficient from a market perspective but also beneficial to society as a whole. Well-designed policies can help achieve this balance, leading to increased social welfare.

In the context of both negative and positive externalities, the state plays a crucial role in putting policies in place to correct market failures and to align market outcomes with social welfare.

For negative externalities, where the activities of companies or individuals have harmful effects on third parties, the state can intervene in several ways:

- Behavioural standards: The state can establish regulations that directly limit harmful activities. These standards can include restrictions on the amount of pollution a plant can emit or requirements for the use of clean technologies.

- Pigouvian taxes: Named after the economist Arthur Pigou, these taxes aim to internalise the cost of negative externalities by including them in the cost of production. The tax is set equal to the cost of the externality for each unit produced, thus encouraging producers to reduce production or find less harmful means of production. In theory, the Pigouvian tax should be equal to the marginal external cost of the socially optimal quantity.

For positive externalities, where the actions of individuals or companies benefit society, the state can also adopt various measures:

- Obligations and Recommendations : Policies can be put in place to encourage behaviour that produces positive externalities. For example, public health campaigns to encourage vaccination or education to promote practices that benefit society.

- Subsidies: By subsidising the production of a good that generates positive externalities, the state can reduce the cost to producers and encourage them to increase production. This can include, for example, subsidies for renewable energy or for research and development in areas of public interest.

- Property rights: Granting property rights or patents on innovations can encourage the creation and dissemination of beneficial technologies or ideas. This allows innovators to benefit directly from their inventions, which might otherwise be under-produced due to the non-excludable nature of their benefits.

These policies aim to align private incentives with social benefits or costs, so that economic activities more accurately reflect their true cost or value to society. By carefully adjusting these interventions, the state aims to achieve an allocation of resources that maximises social well-being.

Private Approaches to Managing Externalities

The Coase Theorem

The Coase Theorem, formulated by the economist Ronald Coase, offers an interesting perspective on how externalities can be managed by the market without government intervention. According to this theorem, if property rights are clearly defined and transaction costs are negligible, the parties affected by the externality can negotiate with each other to reach an efficient solution that maximises total welfare, regardless of the initial distribution of rights. In this context, property rights are the legal rights to own, use and exchange a resource. A clear definition of these rights is essential because it determines who is responsible for the externality and who has the right to negotiate about it. For example, if a property right is granted to a polluter, the parties affected by the pollution (such as local residents) should theoretically negotiate with the polluter and potentially compensate him for reducing the pollution. Conversely, if local residents have the right to enjoy a clean environment, the polluter should compensate them for continuing to pollute.

Coase's theorem also indicates that the efficient allocation of resources will be achieved whatever the distribution of property rights, as long as the parties can negotiate freely. This means that the parties will continue to negotiate until the cost of the externality to the polluter is equal to the cost to society. The essence of this proposition is that the end result (in terms of efficiency) should be the same regardless of who initially holds the rights, a principle known as Coase invariance. However, in practice, the conditions required for the application of Coase's theorem are often not met. Transaction costs may be significant, property rights may be difficult to establish or enforce, and the parties may not have complete or symmetrical information to negotiate effectively. Furthermore, when many parties are involved or the effects of an externality are diffuse and not localised, the coordination required to negotiate private agreements becomes extremely complex.

In these situations where the conditions of Coase's theorem are not met, state intervention through regulations, taxes or subsidies may be necessary to achieve an allocation of resources that reflects the social cost or benefit of the externalities. This helps to ensure that externalities are internalised, leading to a solution that is closer to the social optimum.

The problems you have raised are major challenges when it comes to solving externalities by market means or private solutions, as described in Coase's theorem.

Problem I - High Transaction Costs: Transaction costs include all the costs associated with negotiating and executing an exchange. In the case of externalities, these costs may include the costs of finding information about the affected parties, the costs of negotiating to reach an agreement, the legal costs of formalising the agreement, and the monitoring and enforcement costs of ensuring that the terms of the agreement are respected. When these costs are prohibitive, the parties cannot reach an agreement that would internalise the externality. As a result, the market alone fails to correct the externality, and external intervention, such as by the state, may become necessary to facilitate a more efficient solution.

Problem II - Free-Rider Problem: The free-rider problem is particularly relevant in the case of public goods or when positive externalities are involved, such as environmental protection or vaccination. If a good is non-excludable (it is difficult to prevent someone from benefiting from it) and non-rival (consumption by one person does not prevent consumption by another), individuals may be encouraged not to reveal their true value of the good or service in the hope that others will pay for its provision while themselves enjoying the benefits without contributing to the cost. This leads to under-provision of the good or service as everyone expects someone else to pay for the positive externality, resulting in less than the socially optimal quantity being produced.

These two problems illustrate why markets can often fail to resolve externalities on their own and why government intervention may be necessary. The state can help reduce transaction costs by introducing laws and regulations that facilitate private agreements, and it can overcome the free-rider problem by supplying public goods itself or subsidising their production to encourage provision closer to the social optimum.

The Power of Private Negotiation and the Definition of Property Rights

This graph illustrates a negotiation situation between a polluter and a polluted party concerning pollution abatement, in the context of Coase's theorem. The graph shows two curves: the marginal cost of clean-up for the polluter and the marginal benefit of clean-up for the polluted.

This graph illustrates an economic approach to solving the problem of negative externalities by means of negotiations between parties, in accordance with Coase's theorem. It describes a situation where a polluter and a party affected by the pollution, the polluted party, are involved in a negotiation aimed at finding a level of pollution abatement that maximises collective well-being.

In this representation, the cost to the polluter of reducing pollution, or depolluting, increases with each additional unit of depollution undertaken. This is represented by the rising curve, indicating that the first few units of pollution abatement are relatively inexpensive for the polluter, but that the cost increases progressively. At the same time, the benefit to the polluter of reducing pollution decreases with each additional unit. The first reductions in pollution bring great benefits to the polluter, but these benefits diminish as the air or water becomes cleaner.

The point where these two curves cross, marked Q∗, represents the level of pollution abatement where the marginal benefit of cleaning is exactly equal to the marginal cost of cleaning. This is the ideal level of clean-up from the point of view of economic efficiency, as it perfectly balances the marginal cost and benefit of clean-up.

The framework provided by the graph suggests that, regardless of who initially holds the property rights, whether the polluter or the polluted, there is an opportunity for a mutually beneficial agreement. If the polluter has the right to pollute, the polluted can potentially compensate the polluter financially for reducing pollution, to the point where it is no longer advantageous for the polluted to pay for additional pollution abatement. Conversely, if the polluted party holds the right to a clean environment, the polluter could pay for the right to pollute, until the additional cost of reducing pollution outweighs the benefits to the polluter.

However, in reality, negotiations between the polluter and the polluted are often hampered by high transaction costs. These costs can include the legal costs of establishing and enforcing agreements, the costs of information gathering and negotiation, and the challenges of coordinating a large number of parties. In addition, information asymmetries and the free-rider problem, where individuals benefit from bargaining outcomes without actively participating, can also complicate the private resolution of externalities.

As a result, although Coase's theorem offers an elegant solution on paper, the need for state intervention in the form of environmental regulations or taxes is often unavoidable in order to manage externalities effectively and achieve an allocation of resources that reflects the social cost and benefit of depollution.

Illustration Pratique: Un Accord Négocié en Détail

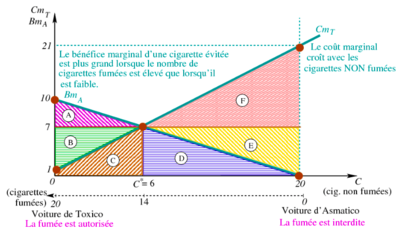

L'analyse des coûts et bénéfices marginaux pour les deux frères, Toxico et Asmatico, nous donne une base pour une possible solution négociée à la question de fumer en voiture lors de leurs voyages.

Pour Toxico, le coût marginal de ne pas fumer une cigarette augmente linéairement avec chaque cigarette non fumée, ce qui est décrit par la fonction . Cela signifie que chaque cigarette supplémentaire qu'il choisit de ne pas fumer lui coûte plus en termes de satisfaction personnelle. Lorsqu'il ne fume pas dans la voiture d'Asmatico, le coût total qu'il subit après avoir renoncé à un paquet entier est de 220 unités de bien-être, qui est la somme des coûts marginaux de chaque cigarette non fumée.

D'autre part, pour Asmatico, qui n'aime pas la fumée, le bénéfice marginal de chaque cigarette non fumée par Toxico diminue avec chaque cigarette supplémentaire non fumée. Cela est représenté par la fonction . Le bénéfice total qu'Asmatico retire de l'abstention de Toxico est de 100 unités de bien-être, ce qui est la somme des bénéfices marginaux pour chaque cigarette non fumée.

Ces fonctions suggèrent que les deux frères peuvent négocier une compensation qui est mutuellement avantageuse. Puisque le coût total pour Toxico de ne pas fumer est plus élevé que le bénéfice total pour Asmatico lorsque Toxico fume, Asmatico pourrait compenser Toxico pour qu'il ne fume pas, jusqu'à un point où le coût marginal de Toxico égale le bénéfice marginal d'Asmatico. La négociation consisterait à déterminer une quantité de cigarettes que Toxico serait prêt à ne pas fumer et le montant que Asmatico serait prêt à payer pour cette abstention.

Par exemple, Toxico pourrait accepter de réduire le nombre de cigarettes qu'il fume si Asmatico lui paie une certaine somme par cigarette non fumée. Ils devraient trouver un accord qui maximise leur bien-être collectif, c'est-à-dire trouver le nombre de cigarettes que Toxico est prêt à ne pas fumer et qui correspond au montant que Asmatico est prêt à payer pour cette réduction. En théorie, selon le théorème de Coase, ils pourraient arriver à un accord sans l'intervention de leurs parents ou d'une autre autorité, à condition que les coûts de transaction pour négocier et faire respecter cet accord soient négligeables.

Le graphique représente une situation économique qui implique deux parties, Toxico et Asmatico, et leurs préférences relatives à fumer des cigarettes pendant qu'ils sont en voiture. Sur l'axe horizontal, nous avons le nombre de cigarettes non fumées, C, et sur l'axe vertical, les coûts et bénéfices marginaux en termes de bien-être ou de satisfaction, mesurés en unités monétaires.

La courbe ascendante, , représente le coût marginal pour Toxico de ne pas fumer de cigarettes. Comme on peut le voir, ce coût marginal augmente avec chaque cigarette supplémentaire qu'il choisit de ne pas fumer. Cela indique que Toxico trouve de plus en plus difficile de renoncer à chaque cigarette supplémentaire.

La courbe descendante, , représente le bénéfice marginal pour Asmatico pour chaque cigarette que Toxico ne fume pas. Le bénéfice est plus élevé lorsque le nombre de cigarettes non fumées est faible et diminue à mesure que davantage de cigarettes sont non fumées.

Le point où les deux courbes se croisent, marqué , suggère un compromis optimal pour les deux parties. À ce point, le coût pour Toxico de ne pas fumer six cigarettes est égal au bénéfice pour Asmatico lorsque six cigarettes ne sont pas fumées. Cela implique que Toxico devrait s'abstenir de fumer exactement six cigarettes pour que les deux parties maximisent leur bien-être combiné.

Le graphique est divisé en différentes zones colorées (A à F), chacune représentant un différent coût ou bénéfice pour Toxico et Asmatico. Par exemple, les zones A et B représentent le coût total pour Asmatico dans la voiture de Toxico lorsque la fumée est autorisée. Les zones C à F représentent le coût total pour Toxico lorsqu'il accompagne Asmatico dans sa voiture et que la fumée est interdite.

Cette illustration sert à montrer comment une négociation Coasienne pourrait se dérouler entre les deux parties. Si elles peuvent négocier sans coûts de transaction, elles pourraient s'entendre sur une compensation pour que Toxico ne fume que six cigarettes, améliorant ainsi le bien-être d'Asmatico sans imposer un coût excessif à Toxico. La négociation pourrait impliquer que Asmatico paie Toxico pour chaque cigarette non fumée jusqu'à atteindre l'équilibre à .

Cependant, si les coûts de transaction étaient significatifs ou si l'une des parties avait une information incomplète sur les préférences de l'autre, atteindre cet accord deviendrait plus compliqué. De plus, si Toxico ou Asmatico adoptait un comportement de resquilleur, en essayant de bénéficier de l'accord sans payer sa part juste, cela pourrait également empêcher de parvenir à une solution efficace. En l'absence d'une solution négociée, une intervention extérieure, telle qu'une réglementation ou une politique mise en place par les parents ou une autorité, pourrait être nécessaire pour résoudre la situation.

1. ACHAT DE PERMIS DE POLLUER

Toxico décide d'acheter le droit de fumer dans la voiture d'Asmatico pour 7 CHF par cigarette. Il continue à fumer jusqu'à ce que son coût marginal de ne pas fumer atteigne 7 CHF. À ce stade, il a renoncé à fumer 6 cigarettes, fumant donc 14 cigarettes sur les 20 habituelles.

Le coût total pour Toxico se compose de deux parties :

- Le coût de l'achat du droit de fumer, qui correspond à la zone D+E dans le graphique. Cela se calcule comme le prix par cigarette multiplié par le nombre de cigarettes fumées, soit CHF.

- Le coût associé à l'abstinence des 6 cigarettes qu'il a décidé de ne pas fumer, correspondant à la surface C. Ce coût est représenté par l'aire d'un triangle avec une base de 6 (le nombre de cigarettes non fumées) et une hauteur de 7 (le coût marginal de la sixième cigarette non fumée, qui commence à 1 CHF pour la première cigarette non fumée et augmente de 1 CHF pour chaque cigarette additionnelle). Par conséquent, l'aire de ce triangle est CHF. Le coût total pour Toxico est donc de 98 CHF pour l'achat des droits de fumer plus 21 CHF pour le coût d'abstinence, ce qui fait un total de 119 CHF.

Cependant, s'il n'avait pas acheté les droits de fumer, fumer toutes les cigarettes lui aurait coûté 220 CHF. Donc, en ne fumant pas ces 6 cigarettes, il réalise un gain de CHF, qui correspond à la surface F.

Asmatico, d'autre part, est prêt à accepter cet arrangement car jusqu'à la treizième cigarette, son bénéfice marginal de ne pas subir la fumée est inférieur à 7 CHF, ce qui est moins que ce qu'il reçoit de Toxico. Il subit un coût associé à la fumée passive des 14 cigarettes que Toxico fume, ce qui correspond à la surface D, évaluée à 49 CHF. Cependant, il gagne 98 CHF de Toxico pour le droit de fumer. Ainsi, son gain net est de CHF, correspondant à la surface E.

Cet exemple démontre comment une négociation Coasienne peut aboutir à une solution où les deux parties s'améliorent grâce à des échanges volontaires, malgré la présence d'externalités négatives.

2. ACHAT DE DROITS À L'AIR PROPRE

Lorsque Asmatico achète le droit à un air propre en payant Toxico pour ne pas fumer dans la voiture, les calculs montrent les résultats suivants :

- Le bénéfice total pour Asmatico, si Toxico ne fumait pas du tout pendant le voyage, serait de 100 CHF.

- Le coût pour Toxico de ne pas fumer 6 cigarettes est de 24 CHF, qui est la somme des coûts marginaux d'abstinence pour ces cigarettes.

- Asmatico paie Toxico 42 CHF pour qu'il s'abstienne de fumer ces 6 cigarettes (7 CHF par cigarette non fumée).

En termes de gain net pour chacun des frères dans ce scénario :

- Toxico reçoit 42 CHF d'Asmatico, et comme son coût d'abstinence est de 24 CHF, son gain net est de 18 CHF.

- Asmatico, d'autre part, paie 42 CHF mais son bénéfice total sans fumée est de 100 CHF, donc son gain net est de 58 CHF.

Dans cette situation, la quantité de cigarettes non fumées est identique à celle du premier scénario : Toxico s'abstient de fumer 6 cigarettes. Cependant, les gains nets diffèrent en raison de la direction du paiement. Asmatico paie pour un air propre, et Toxico reçoit une compensation pour ne pas fumer, contrairement au premier scénario où Toxico payait pour le droit de fumer.

Cela illustre comment la distribution initiale des droits affecte la distribution des gains monétaires entre les parties, même si la quantité de l'externalité (dans ce cas, la fumée de cigarette) reste la même. C'est une démonstration pratique du théorème de Coase : tant que les coûts de transaction sont négligeables et que les droits de propriété sont clairement définis, les parties peuvent négocier des compensations pour atteindre un résultat efficient indépendamment de la répartition initiale des droits.

L'Action Publique Face aux Externalités

La Palette des Interventions Publiques pour les Externalités

Lorsque le marché aboutit à une mauvaise allocation des ressources à cause d'une externalité et qu'une négociation privée n'est pas possible, généralement en raison de coûts de transaction élevés, d'informations asymétriques ou du problème du passager clandestin, le gouvernement peut intervenir pour corriger cette défaillance.

L'une des approches que le gouvernement peut prendre est l'adoption de politiques autoritaires, qui consistent en des réglementations strictes. Ces réglementations peuvent être sous forme d'obligations ou d'interdictions concernant certains comportements. Par exemple, le gouvernement peut rendre la vaccination obligatoire pour tous les écoliers afin de s'assurer que la société bénéficie de l'immunité collective. De même, il peut fixer un niveau maximal de pollution que les entreprises ne doivent pas dépasser pour protéger la santé publique et l'environnement. Ces mesures peuvent être efficaces pour atteindre un résultat souhaité rapidement et de manière assez directe.

Cependant, ces politiques peuvent aussi être considérées comme intrusives et limiter les libertés individuelles ou les choix des entreprises. Elles doivent donc être conçues avec soin pour équilibrer les objectifs de bien-être social et le respect des droits individuels. De plus, leur efficacité dépend de la capacité du gouvernement à les faire respecter, ce qui nécessite souvent un suivi et des ressources significatives.

Lorsque des négociations privées échouent à résoudre les problèmes d'externalités et que le marché ne parvient pas à une allocation optimale des ressources, le gouvernement peut opter pour des interventions qui s'appuient sur les mécanismes de marché pour réaligner les incitations privées avec les intérêts sociaux. Ces interventions, dites "orientées vers le marché", cherchent à utiliser les prix et les incitations économiques pour encourager les comportements souhaitables sans imposer directement des réglementations.

Les taxes pigouviennes sont un exemple classique d'une telle politique. Nommées d'après l'économiste Arthur Pigou, elles sont conçues pour internaliser les coûts des externalités négatives. En taxant des activités qui produisent des effets externes nuisibles, comme la pollution, le gouvernement peut inciter les entreprises et les consommateurs à réduire leur comportement polluant jusqu'à ce que le coût social et privé soit aligné. Le montant de la taxe est généralement fixé pour être égal au coût marginal externe de l'activité polluante à la quantité socialement optimale.

D'un autre côté, les subventions peuvent être utilisées pour encourager des comportements ayant des externalités positives. Par exemple, le gouvernement peut offrir des aides financières pour les travaux d'amélioration de l'isolation des habitations privées, ce qui réduit la consommation d'énergie et, par conséquent, les émissions de gaz à effet de serre. De même, des subventions pourraient être offertes aux entreprises qui investissent dans la recherche et le développement de technologies propres ou dans la formation de leur main-d'œuvre, ce qui peut avoir des retombées positives pour l'ensemble de l'économie.

Ces politiques orientées vers le marché sont souvent préférées aux réglementations directes car elles peuvent atteindre les objectifs souhaités tout en permettant une certaine flexibilité dans la manière dont les individus et les entreprises répondent aux incitations fiscales. Cependant, leur conception et leur mise en œuvre nécessitent une compréhension précise de la nature et de la taille des externalités, ainsi qu'une capacité à ajuster les taxes et les subventions de manière appropriée pour éviter des effets secondaires indésirables ou des distorsions du marché.

Comparaison des Systèmes de Permis et d'Imposition

L'État dispose en effet de deux principales approches pour réduire la pollution émanant d'une usine :

- Réglementation : L'État peut imposer une réglementation stricte qui oblige l'usine à réduire la pollution à un niveau spécifique. Ces limites réglementaires sont souvent définies après des études environnementales et sanitaires et peuvent inclure des plafonds sur les émissions de polluants spécifiques. L'usine doit alors ajuster ses processus de production, investir dans des technologies de contrôle de la pollution ou changer ses matières premières pour se conformer aux normes imposées. Cette approche de "commande et contrôle" offre aux autorités une assurance que certaines réductions de pollution seront réalisées, mais peut être coûteuse pour les entreprises et ne fournit pas de flexibilité quant à la manière d'atteindre ces réductions.

- Taxe Pigouvienne : Alternativement, l'État peut imposer une taxe pigouvienne, qui est une taxe sur chaque unité de pollution émise. Le montant de la taxe est idéalement égal au coût marginal externe de la pollution à la quantité optimale de pollution. Cette taxe incite l'usine à réduire la pollution, car elle doit maintenant payer pour l'impact externe de ses émissions. La taxe pigouvienne offre une flexibilité à l'usine sur la façon de réduire la pollution, car elle peut choisir de payer la taxe, de réduire la pollution pour éviter la taxe, ou une combinaison des deux. Cela peut également encourager l'innovation en matière de technologies de réduction de la pollution, car réduire les émissions devient financièrement avantageux.

Chacune de ces approches a ses avantages et inconvénients. La réglementation peut être plus directe et plus facile à comprendre pour le public, mais elle peut également être moins efficiente et moins flexible. Les taxes pigouviennes, quant à elles, sont généralement considérées comme plus efficientes du point de vue économique, car elles permettent à chaque usine de trouver la manière la plus rentable de réduire sa pollution. Cependant, déterminer le montant exact de la taxe pour correspondre au coût marginal externe de la pollution peut être complexe et sujet à des débats politiques et économiques.

Le système de plafonnement et d'échange, également connu sous le nom de marché des permis à polluer, est une méthode orientée vers le marché pour contrôler la pollution en fournissant des incitations économiques pour réduire les émissions polluantes. Voici comment il fonctionne :

- Plafonnement : L'État fixe un plafond, c'est-à-dire une limite maximale sur la quantité totale de pollution qui peut être émise par toutes les entreprises concernées. Ce plafond est inférieur au niveau actuel des émissions pour forcer une réduction globale.

- Distribution de Permis : L'État alloue ou vend des permis à polluer aux entreprises, où chaque permis autorise le détenteur à émettre une certaine quantité de pollution. Le nombre total de permis correspond au plafond d'émissions fixé par l'État.

- Échange : Les entreprises qui peuvent réduire leurs émissions à un coût inférieur au prix du marché des permis auront un incitatif à le faire et pourront vendre leurs permis excédentaires. Cela crée un marché pour les droits à polluer. Les entreprises pour qui la réduction des émissions est plus coûteuse peuvent acheter des permis supplémentaires sur le marché pour se conformer à la réglementation.

Le système de cap-and-trade a plusieurs avantages. Il offre une flexibilité aux entreprises pour atteindre les objectifs de réduction des émissions de la manière la plus économique. Il encourage également l'innovation en matière de technologies propres car les économies réalisées grâce à des réductions plus efficaces peuvent être rentables.

Cependant, il existe un problème potentiel avec ce système lié au lobbying. Les entreprises et les groupes d'intérêts peuvent exercer des pressions pour augmenter le nombre de permis alloués, ce qui augmenterait le plafond des émissions autorisées et réduirait l'efficacité du programme en termes de réduction de la pollution. Si le plafond est fixé trop haut, les permis peuvent devenir trop abondants et bon marché, ce qui réduit l'incitation à investir dans la réduction de la pollution.

Pour que le système de plafonnement et d'échange fonctionne efficacement, il est crucial que le plafond d'émissions soit fixé à un niveau qui reflète les véritables objectifs de réduction de la pollution et qu'il soit progressivement abaissé au fil du temps pour encourager des réductions continues. De plus, le processus d'allocation des permis doit être transparent et équitable pour prévenir la manipulation du marché et assurer une concurrence juste et efficace.

Taxes Pigouviennes et Permis de Pollution: Une Évaluation de leur Équivalence

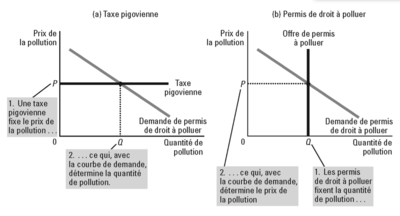

Les graphiques ci-dessou comparent les approches de la taxe pigouvienne et des permis d'émission négociables pour réguler la pollution. Ces deux mécanismes visent à réduire la pollution en imposant des coûts aux pollueurs, mais ils fonctionnent de manière légèrement différente.

Taxe Pigouvienne (Graphique a) : La taxe pigouvienne est un prix fixé par l'État sur la pollution. Ce prix est conçu pour refléter le coût externe que la pollution impose à la société. Le graphique montre une ligne horizontale à un prix déterminé par la taxe. Le point où cette ligne coupe la courbe de demande de la pollution indique la quantité de pollution qui sera produite au prix fixé par la taxe. Les entreprises polluantes paieront la taxe pour chaque unité de pollution qu'elles émettent, et cette taxe est censée inciter les entreprises à réduire leurs émissions jusqu'à ce que le coût marginal de réduction de la pollution soit égal à la taxe. Le principal avantage de cette approche est qu'elle permet aux entreprises de décider comment elles vont réduire la pollution, leur donnant la flexibilité pour trouver les solutions les moins coûteuses. Cependant, le niveau de pollution résultant n'est pas garanti car il dépend de la réaction des entreprises à la taxe. Si la taxe est trop basse, la pollution pourrait rester élevée ; si elle est trop élevée, elle pourrait imposer des coûts excessifs aux entreprises.

Marché des Permis à Polluer (Graphique b) : Dans le système de cap-and-trade, également connu sous le nom de marché des permis à polluer, l'État fixe un plafond sur la quantité totale de pollution qui peut être émise. Des permis correspondant à ce plafond sont distribués ou vendus aux entreprises polluantes. Ces permis sont négociables, ce qui signifie que les entreprises qui peuvent réduire la pollution à moindre coût vont vendre leurs permis excédentaires à d'autres entreprises pour qui la réduction est plus onéreuse. Le graphique montre que le prix des permis est déterminé par le point où la courbe d'offre de permis (qui est verticale car le nombre de permis est fixe) coupe la courbe de demande des entreprises pour le droit à polluer. L'avantage de ce système est qu'il garantit un niveau de pollution ne dépassant pas le plafond fixé. Toutefois, le prix des permis peut varier et peut être difficile à prévoir, ce qui peut créer de l'incertitude pour les entreprises.