« Consumer and producer surplus » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 295 : | Ligne 295 : | ||

Finally, total market surplus (Stot) is the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. It represents the total sum of economic benefits for consumers and producers in the lamb meat market. Here, the total surplus is <math>Stot = SC + SP = 1210 + 508.2 = 1718.2</math> dollars. This means that the allocation of resources in this lamb meat market, at the equilibrium price and quantity, generates a total economic welfare of 1718.2 dollars for society. | Finally, total market surplus (Stot) is the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. It represents the total sum of economic benefits for consumers and producers in the lamb meat market. Here, the total surplus is <math>Stot = SC + SP = 1210 + 508.2 = 1718.2</math> dollars. This means that the allocation of resources in this lamb meat market, at the equilibrium price and quantity, generates a total economic welfare of 1718.2 dollars for society. | ||

== Discussion | == Market Efficiency Discussion == | ||

=== Concepts | === Key Concepts of Market Efficiency === | ||

The fundamental principles of economic theory concerning the efficiency of markets, particularly in a framework of perfect competition. Here is a detailed explanation of each of these remarks: | |||

# Allocation | # Allocation to buyers according to value assigned: In an efficient market, goods and services are allocated in priority to the buyers who value them most. This is demonstrated by their willingness to pay a higher price than other buyers. This principle ensures that resources are used in the most advantageous way, as goods are consumed by those who derive the greatest subjective benefit from them. This allocation can be seen on the market equilibrium graph, where the price reflects the meeting between consumers' willingness to pay and producers' willingness to sell. | ||

# Allocation | # Allocation to the most efficient producers : Producers who can offer goods and services at the lowest cost, thanks to advantages such as more efficient technologies, better access to resources, or more efficient production methods, will be the ones who can sell at competitive prices on the market. This leads to a situation where the most efficient producers are those who stay in business, while the least efficient leave the market or adapt to become more competitive. This maximises productive efficiency, as goods are produced at the lowest possible cost. | ||

# | # Total surplus maximisation and laissez-faire optimality: The idea that the free market, without external intervention, leads to an allocation of resources that maximises total surplus is a conclusion of economic welfare theory. In the absence of market failures, the competitive equilibrium achieved is Pareto efficient, because it is not possible to improve the well-being of one individual without worsening that of another. This laissez-faire principle is often cited in defence of free markets and economic policies that limit government intervention. | ||

These remarks presuppose a set of idealised assumptions that include perfectly competitive markets, an absence of market power for buyers and sellers, the absence of externalities, complete and perfectly symmetrical information, and well-defined and enforced property rights. In reality, these conditions are often not all met, which may justify intervention to correct the resulting inefficiencies and improve overall well-being. | |||

Efficiency in the Pareto sense, which is achieved in a perfectly competitive market, focuses solely on maximising the total surplus without taking into account the distribution of this surplus between the various market players. In other words, although a market may be efficient by maximising total surplus, this does not guarantee that the result is equitable or 'fair' in terms of the distribution of resources and income between individuals. | |||

Equity is a normative concept that concerns social justice and the distribution of goods and wealth in society. Criteria for fairness vary widely according to political and philosophical perspectives, and what is considered fair in one society may be perceived differently in another. For example, a distribution of resources that promotes equality of outcomes may be considered fair according to some ethical frameworks, while others might value equality of opportunity or proportionality, where rewards are distributed according to each individual's contribution. | |||

Economic efficiency and equity are therefore often treated separately in economics. Public intervention, such as progressive taxation and income redistribution, is commonly used to correct inequality and improve equity. However, these interventions can sometimes conflict with market efficiency by introducing distortions. As a result, policymakers face the challenge of balancing efficiency and equity, which may require delicate trade-offs and policy choices. | |||

=== | === Exploring the Limits of Market Autonomy === | ||

The limits of the laissez-faire principle arise from a variety of real-world conditions that deviate from the ideal of perfectly competitive markets. These market failures often justify government intervention to correct or mitigate inefficiencies and promote a more equitable allocation of resources. The main market failures mentioned are | |||

* | * Imperfect competition: In a market where there is imperfect competition, such as monopolies, oligopolies or monopsomes, producers or consumers can influence prices and quantities, preventing the market from achieving an efficient allocation of resources. Market power can lead to higher prices and lower quantities than would be achieved in a competitive market, reducing the total surplus. | ||

* | * Positive or negative externalities: An externality is an effect that an economic transaction between two parties has on a third party who is not directly involved in the transaction. Negative externalities, such as pollution, generate social costs that are not taken into account by producers or consumers, while positive externalities, such as innovation, generate social benefits that exceed private benefits. Markets left to their own devices fail to internalise these costs or benefits, which can lead to overproduction in the case of negative externalities and underproduction in the case of positive externalities. | ||

* | * Public goods: Public goods are goods that are non-excludable (no one can be prevented from consuming them) and non-rivalrous (consumption by one person does not affect availability to others). Examples include national defence, lighthouses or radio broadcasts. Markets tend to under-produce public goods because it is difficult to force users to pay for their consumption, leading to a free rider problem | ||

* | * Inequality problems: Laissez-faire does not guarantee a fair distribution of wealth or income. Markets can lead to outcomes where wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, while others may not have sufficient resources to meet their basic needs. This inequality may be due to initial differences in resource endowments, education or capabilities. | ||

In each of these cases, it may be necessary for governments to intervene with policies such as regulation, taxation, provision of public goods and redistribution programmes to correct market failures and promote a fairer and more efficient society. | |||

=== | === Analysis of Government Interventions and Failures === | ||

Just as there are market failures, there are also government failures, sometimes referred to as 'state failures'. These failures can occur when government interventions fail to improve market outcomes or unintentionally worsen them. Examples of such failures include | |||

* | * Bureaucratic inefficiency: Governments can suffer from red tape that hampers their ability to respond quickly and effectively to economic problems. Bureaucracy can be inefficient because of the complexity of procedures, the lack of performance incentives, or the difficulty of measuring and rewarding productivity. | ||

* | * Imperfect information: Like market participants, government decision-makers may lack complete or accurate information, which can lead to sub-optimal decisions or unintended consequences. Regulatory capture: This occurs when regulated industries exert undue influence on the government agencies responsible for regulating them, often to shape laws and policies to their advantage. This can result in regulations that serve the interests of business at the expense of the public interest. | ||

* Short-term political objectives: Politicians may be motivated by short-term electoral cycles, leading them to focus on policies that generate visible short-term benefits at the expense of long-term benefits, or to avoid unpopular but necessary measures. | |||

* | * Incentive problems: Incentives for government actors are not always aligned with the interests of society as a whole. For example, politicians may have an incentive to engage in excessive public spending to win popular support, even if this spending is not economically justified. | ||

* | * High transaction costs: Government intervention is often accompanied by high transaction costs, particularly in terms of implementation and regulatory compliance. | ||

* | |||

For these and other reasons, it is crucial to carefully evaluate any planned government intervention to ensure that it achieves its objectives without causing collateral damage or unexpected side-effects. Cost-benefit analysis is an important tool in this process, weighing the expected benefits of a policy against its potential costs and risks of failure. | |||

= Théorie et Pratique de la Taxation = | = Théorie et Pratique de la Taxation = | ||

Version du 5 janvier 2024 à 10:02

Based on a course by Federica Sbergami[1][2][3]

Microeconomics Principles and Concept ● Supply and demand: How markets work ● Elasticity and its application ● Supply, demand and government policies ● Consumer and producer surplus ● The economics of the public sector ● The costs of production ● Firms in competitive markets ● Monopoly ● Oligopoly ● Monopolisitc competition

Welfare economics is an important branch of economics that focuses on understanding and evaluating the efficiency and equity of resource allocation by the market. This discipline seeks to determine whether the allocation of resources through the market mechanism maximises collective well-being. It operates through two distinct but complementary prisms of analysis: positive analysis and normative analysis.

Positive analysis seeks to observe and describe economic phenomena objectively. For example, it may look at the effects of a change in tax policy on incomes without judging whether these effects are desirable or not. Normative analysis, on the other hand, ventures into the realm of value judgements, asking what ought to be. It assesses, for example, whether the allocation of resources by the market is fair or efficient, going beyond simple observation to question the desirability of economic outcomes. In welfare economics, tools such as consumer and producer surplus are used to measure the benefits that individuals and firms derive from participating in the market. These tools help to assess whether the market allocates resources in a way that maximises collective welfare, which is the sum of the individual benefits of all market participants.

Welfare economics is also concerned with questions of equity and efficiency. For example, it may examine whether the distribution of resources and wealth is equitable, or whether the market manages to allocate resources in such a way as to maximise production and the satisfaction of society's needs and desires. It also looks at phenomena such as externalities and public goods, where market forces may not lead to an efficient allocation of resources. Externalities, such as pollution, where the costs or benefits of an economic activity affect others who are not directly involved in the transaction, are a classic example of a market failure that welfare economics seeks to understand and correct. The application of welfare economics in real life is vast. For example, governments use its principles to design tax policies that not only generate revenue, but also seek to spread the tax burden fairly. Similarly, in the case of environmental regulation, welfare economics helps to balance the economic costs of reducing pollution with the benefits in terms of public health and the environment.

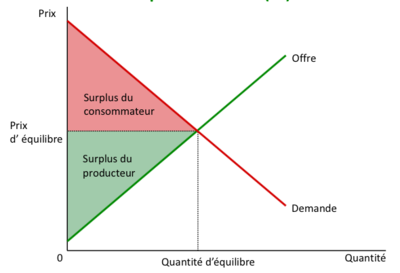

To assess the benefits derived by consumers and producers from their participation in the market, welfare economics relies on the concepts of consumer and producer surplus. These concepts are fundamental to understanding how the market allocates resources and to assessing whether this allocation maximises society's overall well-being. Consumer surplus is the measure of the benefits that consumers obtain by purchasing goods and services. More precisely, it represents the difference between what consumers are prepared to pay for a good or service and what they actually pay. If, for example, a consumer is prepared to pay 15 euros for a product but only pays 10 euros for it, their surplus is 5 euros. This surplus reflects the benefit or satisfaction obtained over and above the cost incurred. On the other hand, the producer surplus is the difference between the amount producers receive for selling their goods or services and the cost of producing them. It is essentially the profit that producers make from selling their products over and above their production costs. For example, if a producer sells a good for €20 when the cost of production is €15, his surplus is €5.

In a perfectly functioning market, with no flaws (such as externalities, public goods, imperfect information or monopolies), the market's allocation of resources is said to be "efficient" in the Pareto sense. This means that no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. In such an ideal scenario, the market succeeds in maximising aggregate welfare, which is the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. This translates into an allocation of resources that not only maximises aggregate output, but does so in a way where the benefits of some are not obtained at the expense of others. This idealised analysis of the perfect market serves as a benchmark for assessing the performance of real markets. Economists can then identify market failures and propose policy interventions to correct these failures, with the aim of improving the efficiency and equity of resource allocation.

Economic Surplus Analysis

Consumer and producer surplus are fundamental concepts in economics that allow us to analyse and evaluate the efficiency with which markets allocate resources. These two measures help us to understand the benefits that consumers and producers derive from their interactions in the market. They are essential indicators for assessing market performance and for guiding economic policies aimed at improving the efficiency and equity of resource allocation.

Consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are willing to pay for a good or service and what they actually pay. It therefore represents the benefit or advantage that a consumer obtains by acquiring a good at a lower price than he was prepared to pay. For example, if an individual is prepared to pay 15 euros for a book but only pays 10 euros for it, their consumer surplus is 5 euros. This surplus indicates the additional value that the consumer perceives in the purchase over and above the price paid. On the other hand, the producer surplus is the difference between the price at which a good is sold and the minimum cost for which the producer was prepared to sell it. In other words, it is the profit or advantage that a producer derives from the sale of a good, over and above its production costs. Let's take the example of a farmer who sells apples: if the production cost of an apple is €0.50 and he sells it for €1, his producer surplus per apple is €0.50. This surplus reflects the economic gain made by the producer on the sale.

In an ideally functioning market, where there are no market failures such as externalities or monopolies, total surplus (the sum of consumer and producer surplus) is maximised. This means that resources are allocated as efficiently as possible, thereby maximising general welfare. For example, in a competitive fruit and vegetable market with no market failures, the equilibrium price and quantity result in maximum consumer and producer surplus, reflecting an efficient allocation of agricultural resources. However, in reality, markets can often be imperfect due to various failures. For example, in the case of industrial pollution (a negative externality), the cost of pollution is not factored into the price of the product, which can lead to overproduction and overconsumption of that product, thereby reducing social welfare. Government interventions, such as taxing polluters or environmental regulations, aim to correct these shortcomings and bring resource allocation closer to ideal efficiency.

Understanding Market Demand

Consumer surplus is an economic concept that measures the benefit or advantage that a consumer derives from participating in the market. This surplus is calculated as the difference between the price the consumer is prepared to pay for a good or service (his reserve price) and the price he pays to acquire it. To illustrate this concept, let's take the example of a consumer who is considering buying a smartphone. If this consumer is prepared to pay up to 800 euros for a particular smartphone, but finds an offer at 600 euros, his consumer surplus is 200 euros. This means that he obtains an additional benefit of 200 euros in terms of satisfaction or perceived value, because he has paid much less for the smartphone than the maximum price he was prepared to pay.

This consumer surplus is a way of quantifying the welfare gain that consumers obtain by participating in the market. It represents the difference between their subjective assessment of the value of a good and the amount they actually spend to obtain it. In a market economy, consumer surplus is often used to assess the efficiency of resource allocation and to analyse the impact of economic policies, such as taxes or subsidies, on consumer welfare.

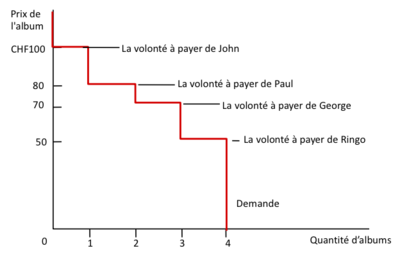

This table is divided into two main sections: the first lists the willingness to pay of different buyers for original Rolling Stones albums, and the second shows how the quantity demanded varies with the price of the albums.

In the first section, we have four buyers - John, Paul, George, and Ringo - each with a different willingness to pay for an album. John is willing to pay the most, up to CHF 100 (Swiss francs), while Ringo is willing to pay the least, with a maximum of CHF 50. The second section of the table details how the price affects the quantity requested. When the price is over CHF 100, none of the buyers is prepared to buy the album, which means that the quantity requested is zero. If the price is between CHF 80 and CHF 100, only John is interested, as he is the only one willing to pay in this price range, so the quantity requested is one album. If the price falls to between CHF 70 and CHF 80, both John and Paul will be willing to buy the album, increasing the quantity requested to two. Between CHF 50 and CHF 70, three buyers (John, Paul and George) are prepared to buy, and finally, if the price is less than or equal to CHF 50, all the buyers are prepared to buy, increasing the quantity demanded to four albums.

Let's now analyse the consumer surplus for each price. If the albums are sold at CHF 50, John, Paul and George all have consumer surplus, which is the difference between their willingness to pay and the selling price. For example, if John buys at CHF 50, his surplus is CHF 100 - CHF 50 = CHF 50. Similarly, Paul would have a surplus of CHF 30 and George CHF 20. Ringo would have no surplus because his reserve price is equal to the market price. This table is a good illustration of the law of demand, which states that the quantity demanded of a good increases as its price falls, provided that all other factors remain constant. It also shows how consumer surplus varies for each individual as a function of the price of the good.

In the context of pricing policy, if a seller wanted to maximise revenue without regard to consumer surplus, he could set the price at CHF 70, thus selling two albums to John and Paul, which is less than the maximum quantity but at a higher price than if all the albums were sold at CHF 50. However, to maximise total welfare (the sum of consumer and producer surpluses), the seller would have to strike a balance between setting the price high enough to cover costs and generate a profit, while keeping it low enough to allow as many buyers as possible to benefit from a significant surplus.

Construction of the Aggregate Demand Curve

The aggregate demand curve represents the total quantity of a certain good or service that all consumers in a market are willing to buy at each possible price level. It is constructed by adding together the quantities demanded by all consumers at each price level. The curve shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity of that good that consumers are willing to buy, assuming that all other factors affecting demand remain constant (ceteris paribus).

In general, the aggregate demand curve has a negative slope, reflecting the law of demand: when the price of a good increases, the quantity demanded of that good decreases, and vice versa. This can be explained by two main effects:

- The substitution effect: When the price of a good increases, consumers will look for cheaper substitutes, thus reducing the quantity demanded of the more expensive good;

- The income effect: An increase in price reduces consumers' purchasing power, which reduces their ability to buy products at the same level as before.

In practice, the demand curve can be affected by many factors other than price, such as changes in consumer incomes, changes in tastes and preferences, changes in the prices of substitute and complementary goods, and future consumer expectations. When these factors change, they can shift the demand curve to the left or right.

To construct the aggregate demand curve from the data in the table provided, we would add up the quantity that each buyer is prepared to purchase at different price levels. Then, by placing the price on the vertical axis and the quantity on the horizontal axis, we would draw a curve linking the different points corresponding to the quantities demanded accumulated at each price. This aggregate demand curve would then be used to analyse how price changes influence the total quantity demanded on the market.

This image shows an aggregate demand curve for albums, probably in a hypothetical or case study context. This curve is plotted on a graph with the price of the album on the vertical axis (CHF) and the quantity of albums on the horizontal axis.

The curve is made up of horizontal segments at prices that correspond to the willingness of individual buyers to pay for the album:

- John is willing to pay up to 100 CHF, which is the highest price on the demand curve.

- Paul has a willingness to pay of up to 80 CHF.

- George is willing to pay up to 70 CHF.

- Ringo has the lowest willingness to pay, at 50 CHF.

The "stair step" formed by the curve indicates that each buyer has a specific willingness to pay and that no buyer is prepared to pay more than his or her indicated willingness to pay. When the price is above the willingness to pay of all buyers, the quantity demanded is zero. As the price decreases to match the willingness to pay of each successive buyer, the quantity demanded increases in stages. The curve clearly shows the law of demand: as the price falls, the quantity demanded increases. At a price of CHF 100, no albums are in demand. When the price drops to CHF 80, John starts asking for an album, which increases the quantity requested to 1. At CHF 70, Paul joins John, bringing demand to 2 albums. At CHF 50, all the buyers are ready to buy the album, bringing total demand to 4.

This graph also illustrates the concept of consumer surplus. For example, if the albums are sold at CHF 50 each, John benefits from a consumer surplus equal to the difference between his willingness to pay (CHF 100) and the price of the album (CHF 50), i.e. a surplus of CHF 50. Similar calculations can be made for Paul and George.

In a real-world context, this representation would help sellers understand how price influences demand and could be used to determine the optimal selling price that maximises either quantity sold or total revenue, depending on the seller's business objective. However, it should be noted that in real market scenarios, consumer preferences are not always so clearly defined and can be influenced by a multitude of factors other than price alone.

Valuation of Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus is an economic concept that captures the difference between what consumers are prepared to pay for a good or service and what they actually pay. This surplus represents the advantage or benefit that consumers derive from buying a good at a price lower than their reserve price, i.e. the maximum they would be prepared to pay. To illustrate this concept, imagine that a consumer is considering buying a new pair of shoes. If this consumer is prepared to pay up to 120 euros for these shoes, but finds them on sale for 80 euros, his consumer surplus is 40 euros. This calculation is based on the idea that the consumer has made a "saving" of 40 euros compared with what he was prepared to pay initially, which gives him a welfare gain.

Consumer surplus is therefore a measure of the utility gained by consumers when they carry out transactions on markets at prices that are lower than their personal valuations of the goods and services purchased. It is an important concept because it allows us to assess the economic efficiency of markets and to analyse how price changes, due to economic policies or market fluctuations, can influence consumer well-being. When the consumer surplus of all individuals in a market is added together, we obtain a measure of the total welfare that the market generates for consumers. A market is considered to be more efficient if it maximises total consumer surplus, i.e. if consumers together derive the maximum benefit from their purchases relative to what they would have been prepared to spend.

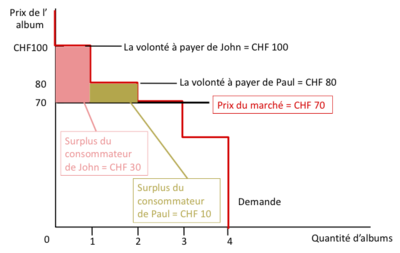

This graph provides a visual illustration of the notion of consumer surplus in a particular market context. On this graph, we see John's willingness to pay for an album, which is indicated by a point on the price axis at CHF 100. The market price is represented by a horizontal line at CHF 80. The difference between John's willingness to pay (CHF 100) and the market price (CHF 80) is represented by a coloured area, which illustrates John's consumer surplus, equivalent to CHF 20. This consumer surplus of CHF 20 indicates the economic advantage that John obtains by buying the album at a lower price than he was prepared to pay. It represents the additional welfare gain or utility that John perceives from making this transaction. In more general terms, consumer surplus is an indicator of the economic benefit obtained by consumers when they purchase goods or services at prices below their reservation prices.

In the context of a market analysis, this surplus can be used to assess how the change in prices would affect consumer welfare. If the market price were to rise, for example, John's consumer surplus would fall, while a fall in the market price would increase his surplus. This could also influence John's decision whether or not to proceed with the purchase, depending on how prices change. The demand curve, shown in the graph, represents the quantity of albums that consumers are prepared to buy at different price levels. It shows the typical inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded: as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

In a real-life situation, understanding consumer surplus can help sellers set their prices strategically to maximise both consumer welfare and their own profit. It can also inform policy makers who are considering measures such as taxes or subsidies, which would directly affect market prices and therefore consumer surplus.

This graph shows the consumer surplus for two individuals, John and Paul, in a hypothetical market where albums are sold. The consumer surplus is visualised by the coloured areas and is calculated as the difference between the individual's willingness to pay (his reserve price) and the current market price.

- For John: His willingness to pay is CHF 100. The market price is CHF 70. The difference between these two amounts is CHF 30, which represents John's consumer surplus.

- For Paul: His willingness to pay is CHF 80, and with the market price at CHF 70, his consumer surplus is CHF 10.

This graph illustrates that when the market price is lower than the consumers' willingness to pay, each of them obtains a surplus, which is a measure of their gain in terms of economic well-being. John enjoys a greater surplus because the difference between his willingness to pay and the market price is greater.

The interesting aspect here is that consumer surplus increases as the market price falls. If the market price were higher, for example at CHF 80, Paul would have no consumer surplus and John's surplus would be reduced. Conversely, if the price were lower than CHF 70, both consumers would see their surplus increase. This illustration also shows the effect of the elasticity of demand. If the price falls and more consumers like George or Ringo enter the market because of their own willingness to pay, the overall consumer surplus in the market would increase. In reality, understanding consumer surplus can help companies set prices that maximise profits while keeping customers satisfied. In addition, policy makers can use this information to assess the impact of fiscal policies, such as sales taxes, on consumer welfare.

Consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are prepared to pay for a good or service (reflecting the value they place on that good) and what they pay on the market. Consumer surplus is therefore a monetary measure of the benefit or utility that consumers obtain from the exchange. Graphically, consumer surplus is represented by the area under the demand curve and above the market price level. On a conventional diagram where the demand curve slopes downwards from left to right, this area takes the form of a triangle or a trapezoid, depending on the precise shape of the demand curve.

Let's take a simple example to illustrate: if the demand curve is linear, and the market price is below the maximum price that some consumers are prepared to pay, the consumer surplus is represented by a triangle. The base of the triangle is the difference between the maximum price willing to be paid (the start of the demand curve on the y-axis) and the market price. The height of the triangle is the quantity purchased at the market price. This surplus represents a gain for consumers, as it indicates that they have been able to acquire a good for less than they were prepared to pay for it, and this gain is often interpreted as a measure of their satisfaction or well-being resulting from their participation in the market. In other words, it quantifies the benefit that consumers derive from the operation of the market in terms of satisfaction or utility in relation to the money spent.

This graph shows a classic representation of the demand curve and consumer surplus in an economic context. The demand curve, plotted in red, illustrates the inverse relationship between the price and the quantity demanded of a good or service, meaning that when the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and vice versa. This relationship is a fundamental law in economics known as the law of demand.

On this graph, the market price is indicated by a horizontal line that intersects the demand curve at a specific point, reflecting the price level at which the good is currently traded on the market. The point where this horizontal line intersects the quantity axis determines the quantity of goods purchased at that market price. Consumer surplus is represented by the area coloured green. This surplus is the difference between the price consumers are willing to pay and the price they actually pay. It is expressed as the area under the demand curve, but above the market price, up to the quantity purchased. This gap represents the additional benefit or utility that consumers derive from buying the good at a price below their maximum willingness to pay.

In this space, each point on the demand curve represents a maximum price that a consumer is prepared to pay for a given quantity of goods. The highest price that some consumers are prepared to pay is illustrated by the highest point on the demand curve, marked as P1. At this price level, the quantity demanded would be zero, since this is the highest price anyone would be prepared to pay and there would be no buyers at this level. As the price falls to the market price, more consumers are willing to buy the good, which is indicated by the point where the market price line intersects the demand curve at quantity Q1. Consumer surplus is an important measure of the total economic benefit that consumers derive from purchasing goods on a market. It is essential for economic analysis because it allows us to understand how price changes affect not only the quantity of goods traded but also consumer welfare. When the market price falls, consumer surplus increases, as consumers derive greater satisfaction from their ability to buy at a lower price than they were prepared to pay.

In practice, companies can take a close interest in consumer surplus when making decisions about the pricing of their products. A price that is too high could significantly reduce consumer surplus and potentially reduce the quantity demanded. Conversely, a price that is too low could increase the quantity demanded but reduce the company's profit margins. The aim is often to find a balance that maximises profits while maintaining a consumer surplus high enough to keep customers satisfied and loyal.

Impact of Changes on Consumer Surplus

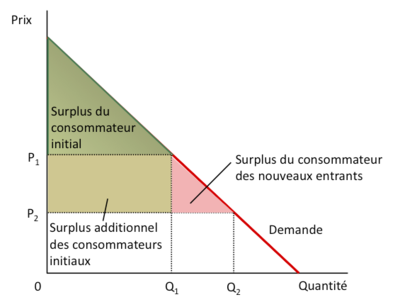

The change in consumer surplus due to a price change is represented by the difference between the areas under the demand curve at the two price levels. When the price of a good or service decreases, consumer surplus increases because consumers benefit from a greater difference between what they are willing to pay and what they do pay. This increase is visualised as the additional area that forms between the demand curve and the new lower price.

Conversely, if the price rises, the consumer surplus falls. This reduction is represented by the loss of the area that existed between the two price levels on the demand curve. Consumer surplus is therefore reduced because consumers are paying a price that is closer to their reserve price, and some consumers who were prepared to buy at the lower price may decide not to buy at the higher price.

This relationship between price change and consumer surplus is fundamental in economics because it reflects the direct impact of price changes on consumer welfare. It is particularly relevant when analysing the impact of economic policies such as product taxation or subsidies, which alter market prices and therefore consumer surplus. Economists and policy makers can use this information to assess the efficiency of markets and the effect of policy changes on general welfare.

This graph illustrates the changes in consumer surplus that result from a reduction in the price of a good or service on a market. The demand curve, represented by the red line descending from left to right, shows the relationship between the price and the quantity demanded of a good.

Initially, the market price is at P1, where the quantity demanded is Q1. The initial consumer surplus at this price level is represented by the area coloured green, which is the area below the demand curve and above the P1 price line, up to Q1. When the price falls to P2, the consumer surplus expands to include not only the initial green area but also the additional area coloured yellow. This yellow area represents the additional surplus that the original consumers receive as a result of the price reduction; they pay less than they were initially willing to pay for Q1 units of the good. Furthermore, at this new lower price, additional consumers enter the market, increasing the quantity demanded at Q2. The consumer surplus of the new entrants is represented by the area coloured red. This is the area below the demand curve and above the price line P2, between Q1 and Q2. These consumers were not prepared to buy the good at the initial price P1, but are encouraged to make purchases because of the reduced price.

Together, the initial consumer surplus, the additional surplus of the initial consumers, and the consumer surplus of the new entrants represent the total consumer surplus after the price cut. This total surplus is an indication of the total economic benefit or welfare that consumers derive from their participation in the market after the price change.

Analysing the impact of a price change on consumer surplus is essential to understanding the economic implications of pricing policies. For example, price reductions can be used as incentives to increase consumption or to make a product more accessible in a market. Conversely, a price increase could reduce consumer surplus and potentially reduce overall demand for the good. Commenting further, it is important to note that if the price falls even further, initial consumers would benefit from an even greater surplus and the number of new entrants could increase, which would broaden total welfare in the market. However, this drop in price could have consequences for producers, notably a reduction in their surplus (not shown in this graph). This is the kind of analysis an economist might use to assess the effects of a pricing policy or to understand market dynamics after changes in supply or demand.

Fundamentals of Market Supply

Producer surplus is an economic concept that reflects the profit made by producers when they sell their goods and services on the market. It is the difference between the income they receive from selling these goods and the cost of producing them. In other words, it is the amount of money that producers earn after covering their production costs.

In practice, producer surplus is represented by the area above the supply curve (which indicates the marginal cost of production or the producers' reserve price) and below the market price at which the goods are sold. If a producer is willing to sell a good for at least €10, but sells it for €15, his producer surplus for that good is €5. This represents the net gain above what was the minimum acceptable for the producer.

Producer surplus is an indicator of the economic health of companies and the profitability of markets. A high surplus may indicate a beneficial market for producers, where they are able to sell at prices substantially higher than their costs. This can stimulate investment, production expansion and innovation. However, it is important to note that producer surplus can be affected by many factors, including changes in production technology, input costs, market competition, and government policies such as taxes and subsidies. A thorough understanding of producer surplus can help policy makers and companies make informed decisions that affect production, pricing and overall market strategy.

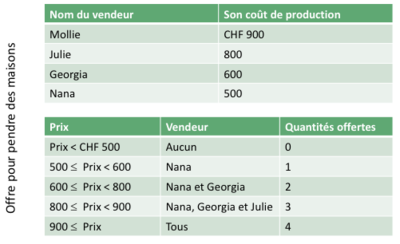

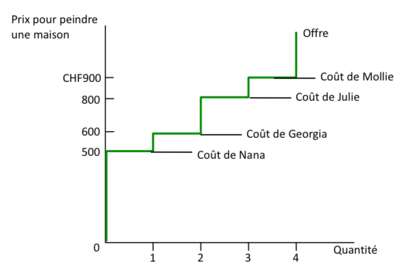

This table provides information on the production costs of different sellers and how these costs influence the quantity of goods they are prepared to offer at different price levels on the market for a specific product, in this case houses.

In the first part of the table, four sellers - Mollie, Julie, Georgia and Nana - are listed with their respective production costs for hanging houses. These costs range from CHF 500 for Nana to CHF 900 for Mollie, suggesting that Nana is the most efficient producer (or has the lowest production costs) and Mollie the least efficient of the four.

The second part of the table relates these production costs to the market price and the quantity offered. When the price is below CHF 500, no seller is prepared to offer his houses, because the market price would not even cover the lowest production cost. This means that the producer's surplus would be negative, as sellers would incur losses at these prices.

As the price rises, sellers are prepared to offer increasing quantities of houses:

- When the price is between CHF 500 and CHF 600, Nana is prepared to sell one house.

- Between CHF 600 and CHF 800, Nana and Georgia together offer two houses.

- Between CHF 800 and CHF 900, Nana, Georgia and Julie offer a total of three houses.

- Finally, when the price exceeds CHF 900, all the sellers, including Mollie, are prepared to offer houses, with a total quantity offered of four houses.

The producer surplus for each seller is the difference between the market price and their cost of production. For example, if houses are sold for CHF 800, Georgia would have a surplus of CHF 200 (CHF 800 - CHF 600), Julie would have a surplus of CHF 0 (since her production cost is CHF 800), and Nana would have a surplus of CHF 300 (CHF 800 - CHF 500).

This information is crucial to understanding how price variations affect supply on the market. If the market price rises, this encourages more sellers to offer their product, as they can obtain a higher surplus. Conversely, a fall in prices could lead to a reduction in supply, as fewer sellers would find it profitable to sell their homes. This illustrates the law of supply, according to which the quantity offered of a good increases when its price rises, provided that all other factors remain constant.

Development of the Aggregate Supply Curve

The aggregate supply curve is an economic concept that represents the relationship between the price of a good or service and the total quantity of that good or service that all producers in the market are willing to sell. This curve is the result of adding together the different quantities that each individual producer is prepared to offer at each possible price level.

The aggregate supply curve is generally upward sloping, which means that the higher the price, the greater the quantities of the good or service that producers are willing to offer. This reflects the principle that higher prices can cover higher production costs and are therefore an incentive for producers to increase their output. At lower prices, fewer producers are able or willing to sell, as prices may not cover production costs or offer an acceptable profit margin.

The slope of the supply curve can vary according to a number of factors, such as production costs, technology, the number of sellers on the market, and producers' expectations for the future. Changes in these factors can shift the aggregate supply curve to the left or right. For example, an improvement in technology could reduce production costs and shift the supply curve to the right, indicating that a greater quantity is available at each price. Conversely, an increase in input costs could shift the curve to the left.

In a market, the aggregate supply curve interacts with the aggregate demand curve to determine the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity - the points at which the quantity producers are willing to sell equals the quantity consumers are willing to buy.

Understanding the aggregate supply curve is essential for market analysis, economic policy formulation and production decision-making. It is a fundamental representation of supply forces in the market and is used to predict producers' reactions to changes in market conditions.

The chart in question illustrates an aggregate supply curve for house painting services, highlighting the production costs of four separate suppliers. This supply curve is characterised by a series of staircases that indicate that each supplier enters the market at different price thresholds, corresponding to their individual production costs.

At the first level, we see that Nana is prepared to offer its painting services from a price of CHF 500, which corresponds to its cost of production. This suggests that Nana will only provide her services if the market price meets or exceeds this threshold, thereby covering her costs and potentially making a profit. As the market price rises to CHF 600, Georgia begins to offer her services, indicating that this is the point at which she can cover her costs and enter the market.

When the price reaches CHF 800, we see that Julie is also willing to provide her services, joining Nana and Georgia. This shows that Julie will only offer her services when the price is high enough to be profitable for her, given her production costs. Finally, Mollie's production cost of CHF 900 marks the highest threshold among suppliers, indicating that she will only enter the market when prices are high enough to exceed her higher production costs.

The aggregate supply curve, which rises step by step, underlines the economic principle that producers are prepared to sell more when the price rises, reflecting the law of supply. This curve visually represents the total quantity of painting services that suppliers are willing to offer at different price levels, and how supply increases as prices rise.

However, this representation does not take into account the complexity and dynamics of real competition in the market. Factors such as technological innovations, changes in raw material costs, or the entry of new competitors could influence the supply curve. For example, if a new technology reduced production costs for all suppliers, we could see the supply curve shift to the right, indicating a greater quantity offered at each price.

This chart helps to understand pricing decisions and production planning based on production costs and the price the market can bear. Suppliers need to carefully assess at what price they can profitably offer their services and how they can adjust their production in response to price changes to maximise their producer surplus.

Calculating Producer Surplus

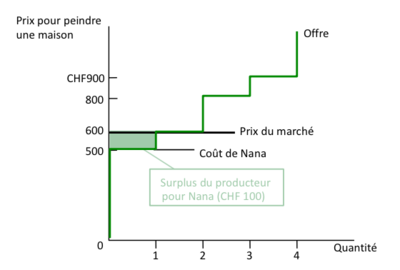

Producer surplus is an economic concept which represents the difference between the price at which producers actually sell their goods or services on the market and the minimum price they would be prepared to accept for these goods or services, i.e. their cost of production. It is a measure of economic profit and indicates the level of welfare that producers derive from selling their products.

When a producer sells a product at a price that is higher than its production cost, he makes a surplus. This surplus can be considered as a gain or profit above what is necessary to induce the producer to produce the good. In other words, if the cost of production represents the minimum compensation required for the producer to be willing to supply a certain quantity of the good, any price above this cost of production contributes to the producer's surplus.

The total producer surplus in a market is the sum of the individual surpluses of all producers. It is graphically represented by the area above the supply curve and below the market price up to the quantity produced.

Producer surplus is an important analytical tool for economists and decision-makers. It can be affected by various factors, such as changes in production costs, technological innovations, government policies, or variations in market demand. For example, a tax on production may reduce the producer's surplus by increasing the cost of production, while subsidies may increase it.

In a market economy, the objective is often to maximise the combined surplus of consumers and producers, which is seen as an indication of economic efficiency. When markets operate freely without external intervention, and conditions of perfect competition are met, consumer and producer surplus is maximised, leading to an allocation of resources that is considered Pareto optimal.

The graph represents a staircase supply curve for a house painting service and illustrates the producer surplus for one supplier, Nana, at a given market price. The staircase supply curve rises at each step, corresponding to the individual production costs of different suppliers to paint a house. These tiers indicate the price points at which additional suppliers enter the market. The higher the price, the more suppliers are willing to offer the service, as the price exceeds their respective production costs.

Nana's production cost is marked on the curve at CHF 500, which means that this is the minimum amount she should receive to cover her costs. The market price is currently set at CHF 600, which is represented by the horizontal line. The difference between the market price and Nana's production cost represents her producer surplus, which is visually indicated by the rectangular area below the market price and above Nana's production cost. In this case, Nana receives a producer surplus of CHF 100 for each house painted (CHF 600 - CHF 500). This surplus is the economic benefit she derives from selling her services above her costs. The graph shows that if the market price were below CHF 500, Nana would not be willing to provide the service because she would not be able to cover her production costs. Conversely, if the market price rose to, say, CHF 800, Nana's producer surplus would increase accordingly.

Producer surplus is a key element in understanding the motivation of producers and their response to price changes in the market. Suppliers will seek to maximise their producer surplus, which contributes to their overall profit. Changes in producer surplus can also indicate changes in the general well-being of producers, influencing their future investment and production decisions.

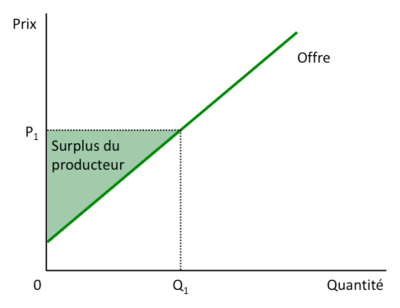

Producer surplus is represented graphically by the area between the supply curve and the market price, up to the quantity produced. Producer surplus is thus the total profit that producers make from selling their goods or services over and above their production costs. The supply curve itself indicates the minimum cost at which producers are willing to offer a certain quantity of the good or service. When the market price is higher than this minimum cost, producers benefit from a surplus, as they receive more than the minimum amount needed to cover their costs. The amount received by producers is the market price multiplied by the number of units sold, while the cost of production is generally represented by the supply curve. When you subtract the total cost of production (the area under the supply curve up to the quantity produced) from the total revenue (the product of the market price and the quantity sold), you get the producer surplus.

This concept is essential for understanding the distribution of profits in the economy and for assessing the efficiency of markets. In a situation of market equilibrium, the producer surplus, combined with the consumer surplus, can be used to assess the Pareto efficiency of the market, where no improvement in the welfare of one economic agent can be made without worsening the welfare of another.

Consequences of Changes on Producer Surplus

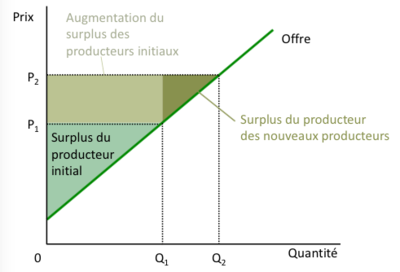

The change in producer surplus following a price change is given by the area above the supply curve between the two prices.

This graph illustrates a linear supply curve for a good or service on a specific market. This supply curve indicates that producers are prepared to offer a greater quantity of their good or service as the price increases, which is consistent with the law of supply in economics. The straight line rising from the origin shows this positive relationship between price and quantity offered.

The market price is represented by the horizontal line at P1, and the corresponding quantity that producers are willing to sell at this price is Q1. The producer surplus is then represented by the green-coloured area below price P1 and above the supply curve up to quantity Q1. This area illustrates the difference between the price producers receive for their goods or services and the cost of producing those goods or services. In other words, this green zone represents the net profit or gain that producers make over and above the minimum compensation they require to produce quantity Q1.

This producer surplus is a crucial element in understanding producers' economic incentives. The greater the surplus, the greater the incentive for producers to increase their production, as this means that they receive a price significantly higher than their cost of production. It is this profit that can be reinvested in the business for innovation, expansion, or used to increase the company's reserves. However, it is important to note that the graph represents a simplified situation. In reality, production costs may vary from one producer to another, and the supply curve may not be linear. In addition, changes in technology, input costs or government policies can shift the supply curve, affecting the producer surplus.

This graph serves as a model for analysing the impact of price variations on producers and can help in making strategic production and pricing decisions. It is also useful for policy makers who may consider interventions to stabilise prices or support certain industries, directly affecting producer surplus in the market.

Optimising Resource Allocation

Maximising Total Surplus

In a perfectly competitive market with no market failures, the market's allocation of resources can maximise overall welfare, known as total surplus, which is the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. Total surplus is a measure of economic efficiency and is maximised when markets operate freely and goods are traded until the additional surplus from each additional transaction is zero. Consumer surplus is the measure of the profit that consumers obtain by buying goods and services at a lower price than they would be willing to pay, while producer surplus is the profit that producers obtain by selling goods and services at a price higher than their cost of production. When these two surpluses are added together, they reflect the total market surplus.

The market is considered to be Pareto efficient when no other allocation of resources can make one individual better off without making another individual worse off. In such a market, the equilibrium price is reached when the quantity demanded equals the quantity offered, which also means that the total surplus is maximised. At this equilibrium point, it is not possible to increase the surplus of one side without decreasing that of the other. However, real markets can have failures that prevent such efficiency. These include the existence of market power (as in monopolies or oligopolies), externalities (where costs or benefits are not fully accounted for by the market), public goods (which are not efficiently produced or allocated by the market because of their non-excludable and non-rival nature) and imperfect information.

Where there are market failures, interventions such as regulations or tax policies may be necessary to correct these inefficiencies and move towards an allocation that maximises total surplus. Welfare economics is the study of these issues, seeking to understand how interventions can influence consumer and producer surplus and, consequently, overall welfare.

In an equilibrium market, the price that consumers pay for a good or service is equal to the price that producers receive for that good or service. Consequently, the price paid and the price received cancel each other out when the total surplus is calculated. This leads to a simplified formula for total surplus, which is the total value that consumers place on goods or services minus the total cost of producing those goods or services. This measure of total surplus is an indicator of the economic efficiency of the market.

When total surplus is maximised, there are no more possible transactions that could increase consumer value without proportionately increasing production costs, and vice versa. In such a state, the market is considered to be Pareto efficient, because it is not possible to make someone better off without making someone else worse off. In an ideal situation, the free market without intervention or failure will achieve this level of efficiency on its own. However, in reality, many markets experience failures that may require intervention to help maximise total surplus and improve economic efficiency. This may include corrections for externalities, regulations to counter market power, or the provision of public goods that the market alone would not optimally produce.

An allocation of resources is considered Pareto efficient if it maximises total surplus, which means that it is impossible to redistribute resources to make one person better off without making another worse off. In terms of surplus, this means that both the consumer surplus and the producer surplus are maximised and no additional gain can be made without one of the parties incurring a loss. In such an efficient situation, the market achieves what is known as a Pareto equilibrium, where resources are allocated in the most beneficial way for society as a whole. The total surplus, which is the sum of the consumer surplus and the producer surplus, is then at its highest level. This implies that consumers derive the greatest possible value from the goods and services they consume, and producers receive the best possible return on their investment and labour. Theoretically, this ideal is achieved in perfectly competitive markets where there are no externalities, public goods, information asymmetries or other market failures. In reality, public interventions such as regulations and taxes are often necessary to correct inefficiencies and move closer to Pareto efficiency.

This graph illustrates a typical market in equilibrium where the supply and demand curves cross. The supply curve is represented by an ascending line indicating that, as the price rises, producers are prepared to offer more goods because of the increased profitability. The demand curve, on the other hand, descends, showing that consumers are prepared to buy fewer goods as the price rises, in accordance with the law of demand.

The point where these two curves cross determines the equilibrium price of the market and the equilibrium quantity. At the equilibrium price, the quantity that producers are prepared to sell is exactly equal to the quantity that consumers are prepared to buy.

Consumer surplus is represented by the area coloured red below the equilibrium price and above the demand curve. This represents the difference between what consumers are prepared to pay (their perceived value of the good or service) and what they pay at the equilibrium price. It is the net profit that consumers obtain from their purchases on the market.

Producer surplus is the green area above the equilibrium price and below the supply curve. This surplus measures the difference between the market price and the price at which producers would theoretically be prepared to sell (which can be regarded as the cost of production). It is the net profit that producers make after selling their goods at the equilibrium price.

When the two surpluses are combined, they form the total market surplus, which is the measure of a market's economic efficiency. In a perfectly competitive market with no externalities or other market failures, total surplus is maximised at equilibrium. This means that it is not possible to increase the well-being of one individual without decreasing that of another, and that the market allocates resources as efficiently as possible.

The graph highlights the efficiency of the market in terms of optimising resources and maximising welfare. However, it should be noted that this ideal situation is based on a number of assumptions, including the absence of barriers to entry and exit, perfect information and homogeneous goods. In reality, these conditions are not always met, and inefficiencies may arise, sometimes requiring intervention to correct the market.

Case Study: Analysis of the Lamb Meat Market

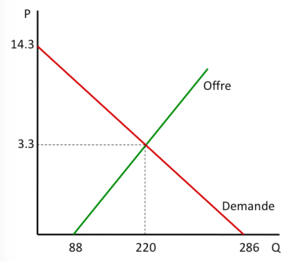

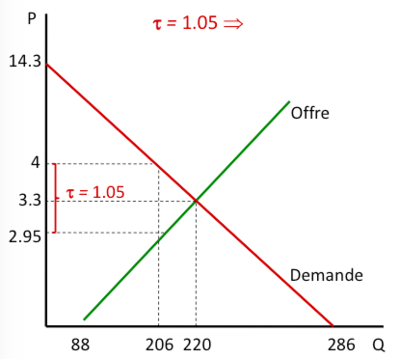

The following graph represents a lamb meat market with the supply and demand curves intersecting to indicate market equilibrium. The vertical axis (P) represents the price of lamb in dollars and the horizontal axis (Q) represents the quantity of lamb.

The demand curve, represented by the red line descending from left to right, indicates that the lower the price, the greater the quantity demanded. This reflects the law of demand: consumers generally demand more of a good as its price falls. The demand curve crosses the price axis at 14.3, which would be the maximum price consumers would be prepared to pay for zero quantity of the product, and it crosses the quantity axis at 286, which represents the maximum quantity consumers would take if lamb meat were free.

The supply curve, represented by the green line rising from left to right, shows that the higher the price, the greater the quantity offered. This follows the law of supply: producers are prepared to sell more of a good as its price rises. The supply curve intersects the quantity axis at 88, which would be the minimum quantity offered at a price of 0.

The two curves intersect at the equilibrium point, where the price is 3.3 dollars and the equilibrium quantity is 220 units. This point of intersection indicates the price and quantity where the quantity that consumers want to buy is exactly equal to the quantity that producers want to sell.

This graph illustrates a market in equilibrium with no surplus or shortage of lamb. The equilibrium is Pareto efficient, which means that it is not possible to make someone better off without making someone else worse off. If the price were higher than 3.3 dollars, there would be a surplus of lamb because the quantity offered would exceed the quantity demanded. If the price were below 3.3 dollars, there would be a shortage because the quantity demanded would exceed the quantity offered. In such a market, the total surplus (the sum of the consumer and producer surpluses) is maximised at this equilibrium point. Consumer surplus would be the area below the demand curve and above the equilibrium price, while producer surplus would be the area above the supply curve and below the equilibrium price. Their sum represents the total economic benefits generated by the market for all participants.

- et

In this example, the lamb meat market is analysed using linear functions to represent demand and supply. The demand and supply equations are given by and respectively, where and are the demand and supply prices. In equilibrium, the quantity demanded and the quantity offered are equal to , and the equilibrium price is dollars.

According to the equations provided:

The equilibrium quantity () is 220 units.

The equilibrium price () is 3.3 dollars.

Consumer surplus (CS) is calculated as the area of a triangle below the demand curve and above the equilibrium price. Mathematically, it is calculated as the difference between the maximum willingness to pay (the price intercept on the price axis of the demand function when quantity is zero) and the equilibrium price, multiplied by the quantity sold in equilibrium, all divided by two. In this example, the consumer surplus is dollars.

Producer surplus (PS) is also calculated as the area of a triangle, but this time above the supply curve and below the equilibrium price. It represents the difference between the equilibrium price and the price at which producers would be willing to supply the good for zero units (the cost of production for zero units), multiplied by the quantity sold at equilibrium, all divided by two. The producer surplus is dollars.

Finally, total market surplus (Stot) is the sum of consumer surplus and producer surplus. It represents the total sum of economic benefits for consumers and producers in the lamb meat market. Here, the total surplus is dollars. This means that the allocation of resources in this lamb meat market, at the equilibrium price and quantity, generates a total economic welfare of 1718.2 dollars for society.

Market Efficiency Discussion

Key Concepts of Market Efficiency

The fundamental principles of economic theory concerning the efficiency of markets, particularly in a framework of perfect competition. Here is a detailed explanation of each of these remarks:

- Allocation to buyers according to value assigned: In an efficient market, goods and services are allocated in priority to the buyers who value them most. This is demonstrated by their willingness to pay a higher price than other buyers. This principle ensures that resources are used in the most advantageous way, as goods are consumed by those who derive the greatest subjective benefit from them. This allocation can be seen on the market equilibrium graph, where the price reflects the meeting between consumers' willingness to pay and producers' willingness to sell.

- Allocation to the most efficient producers : Producers who can offer goods and services at the lowest cost, thanks to advantages such as more efficient technologies, better access to resources, or more efficient production methods, will be the ones who can sell at competitive prices on the market. This leads to a situation where the most efficient producers are those who stay in business, while the least efficient leave the market or adapt to become more competitive. This maximises productive efficiency, as goods are produced at the lowest possible cost.

- Total surplus maximisation and laissez-faire optimality: The idea that the free market, without external intervention, leads to an allocation of resources that maximises total surplus is a conclusion of economic welfare theory. In the absence of market failures, the competitive equilibrium achieved is Pareto efficient, because it is not possible to improve the well-being of one individual without worsening that of another. This laissez-faire principle is often cited in defence of free markets and economic policies that limit government intervention.

These remarks presuppose a set of idealised assumptions that include perfectly competitive markets, an absence of market power for buyers and sellers, the absence of externalities, complete and perfectly symmetrical information, and well-defined and enforced property rights. In reality, these conditions are often not all met, which may justify intervention to correct the resulting inefficiencies and improve overall well-being.

Efficiency in the Pareto sense, which is achieved in a perfectly competitive market, focuses solely on maximising the total surplus without taking into account the distribution of this surplus between the various market players. In other words, although a market may be efficient by maximising total surplus, this does not guarantee that the result is equitable or 'fair' in terms of the distribution of resources and income between individuals.

Equity is a normative concept that concerns social justice and the distribution of goods and wealth in society. Criteria for fairness vary widely according to political and philosophical perspectives, and what is considered fair in one society may be perceived differently in another. For example, a distribution of resources that promotes equality of outcomes may be considered fair according to some ethical frameworks, while others might value equality of opportunity or proportionality, where rewards are distributed according to each individual's contribution.

Economic efficiency and equity are therefore often treated separately in economics. Public intervention, such as progressive taxation and income redistribution, is commonly used to correct inequality and improve equity. However, these interventions can sometimes conflict with market efficiency by introducing distortions. As a result, policymakers face the challenge of balancing efficiency and equity, which may require delicate trade-offs and policy choices.

Exploring the Limits of Market Autonomy

The limits of the laissez-faire principle arise from a variety of real-world conditions that deviate from the ideal of perfectly competitive markets. These market failures often justify government intervention to correct or mitigate inefficiencies and promote a more equitable allocation of resources. The main market failures mentioned are

- Imperfect competition: In a market where there is imperfect competition, such as monopolies, oligopolies or monopsomes, producers or consumers can influence prices and quantities, preventing the market from achieving an efficient allocation of resources. Market power can lead to higher prices and lower quantities than would be achieved in a competitive market, reducing the total surplus.

- Positive or negative externalities: An externality is an effect that an economic transaction between two parties has on a third party who is not directly involved in the transaction. Negative externalities, such as pollution, generate social costs that are not taken into account by producers or consumers, while positive externalities, such as innovation, generate social benefits that exceed private benefits. Markets left to their own devices fail to internalise these costs or benefits, which can lead to overproduction in the case of negative externalities and underproduction in the case of positive externalities.

- Public goods: Public goods are goods that are non-excludable (no one can be prevented from consuming them) and non-rivalrous (consumption by one person does not affect availability to others). Examples include national defence, lighthouses or radio broadcasts. Markets tend to under-produce public goods because it is difficult to force users to pay for their consumption, leading to a free rider problem

- Inequality problems: Laissez-faire does not guarantee a fair distribution of wealth or income. Markets can lead to outcomes where wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, while others may not have sufficient resources to meet their basic needs. This inequality may be due to initial differences in resource endowments, education or capabilities.

In each of these cases, it may be necessary for governments to intervene with policies such as regulation, taxation, provision of public goods and redistribution programmes to correct market failures and promote a fairer and more efficient society.

Analysis of Government Interventions and Failures

Just as there are market failures, there are also government failures, sometimes referred to as 'state failures'. These failures can occur when government interventions fail to improve market outcomes or unintentionally worsen them. Examples of such failures include

- Bureaucratic inefficiency: Governments can suffer from red tape that hampers their ability to respond quickly and effectively to economic problems. Bureaucracy can be inefficient because of the complexity of procedures, the lack of performance incentives, or the difficulty of measuring and rewarding productivity.

- Imperfect information: Like market participants, government decision-makers may lack complete or accurate information, which can lead to sub-optimal decisions or unintended consequences. Regulatory capture: This occurs when regulated industries exert undue influence on the government agencies responsible for regulating them, often to shape laws and policies to their advantage. This can result in regulations that serve the interests of business at the expense of the public interest.

- Short-term political objectives: Politicians may be motivated by short-term electoral cycles, leading them to focus on policies that generate visible short-term benefits at the expense of long-term benefits, or to avoid unpopular but necessary measures.

- Incentive problems: Incentives for government actors are not always aligned with the interests of society as a whole. For example, politicians may have an incentive to engage in excessive public spending to win popular support, even if this spending is not economically justified.

- High transaction costs: Government intervention is often accompanied by high transaction costs, particularly in terms of implementation and regulatory compliance.

For these and other reasons, it is crucial to carefully evaluate any planned government intervention to ensure that it achieves its objectives without causing collateral damage or unexpected side-effects. Cost-benefit analysis is an important tool in this process, weighing the expected benefits of a policy against its potential costs and risks of failure.

Théorie et Pratique de la Taxation

Introduction aux Principes de Taxation

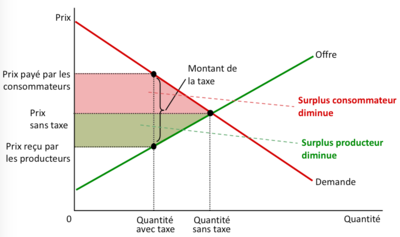

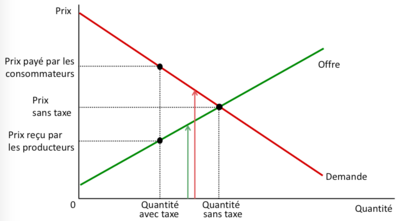

Lorsqu'un gouvernement impose une taxe sur un bien ou un service, cela a des répercussions immédiates et importantes sur l'économie de ce marché. La présence de la taxe tend à diminuer la quantité de biens ou de services échangés, car elle introduit une charge supplémentaire qui doit être prise en compte par les consommateurs et les producteurs. Par exemple, si une taxe est imposée sur le carburant, les consommateurs pourraient réduire leur consommation en raison de l'augmentation du prix, et les stations-service pourraient être moins enclines à garder de grandes quantités de carburant en stock, sachant que la demande a diminué.

Le prix que les consommateurs paient pour le bien ou service taxé s'accroît généralement de la valeur de la taxe. Reprenons l'exemple du carburant : si le gouvernement impose une taxe de 0,20 $ par litre, le prix à la pompe pour les consommateurs augmentera probablement d'autant, rendant le carburant plus cher pour les conducteurs. En revanche, le prix que les producteurs reçoivent pour chaque unité vendue diminue, car une partie de l'argent qui leur aurait autrement été versé est désormais destinée au gouvernement sous forme de taxe. Dans notre exemple, cela pourrait signifier que les raffineries de pétrole reçoivent moins pour chaque litre de carburant vendu, ce qui pourrait les amener à réduire leur production.

Un aspect clé de la taxation est que l'incidence fiscale, ou le fardeau économique réel de la taxe, ne dépend pas nécessairement de qui est légalement tenu de la payer. Que la taxe soit prélevée sur les vendeurs ou les acheteurs, les effets sur le marché en termes de prix et de quantités seront les mêmes après que les ajustements du marché auront eu lieu. Cela est dû aux changements de comportement des consommateurs et des producteurs en réponse à la taxe, qui affectent finalement les prix d'équilibre et la répartition des charges fiscales entre eux.

Qui porte le poids réel de la taxe dépend en grande partie des élasticités de l'offre et de la demande. L'élasticité mesure la sensibilité de la quantité demandée ou offerte à un changement de prix. Si, par exemple, nous considérons un médicament essentiel pour lequel il n'y a pas de substitut proche et pour lequel les patients ont absolument besoin, la demande sera probablement inélastique. Dans ce cas, même si le prix du médicament augmente en raison de la taxe, les patients continueront à l'acheter, car ils n'ont pas d'autre choix. En conséquence, les consommateurs finiront par supporter une grande partie de la taxe. À l'inverse, si un produit a de nombreux substituts proches, comme les fruits, une petite augmentation de prix en raison d'une taxe pourrait amener les consommateurs à se tourner vers les alternatives, ce qui signifie que les producteurs ne peuvent pas répercuter la totalité de la taxe sur les consommateurs sans perdre une part significative de leur marché.

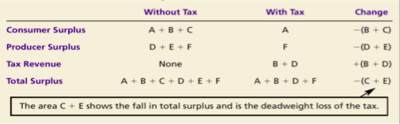

La taxation a un impact à double facette sur l'économie : elle affecte le bien-être des participants du marché et génère des revenus pour le gouvernement.

Impact sur le bien-être (Surplus Total)

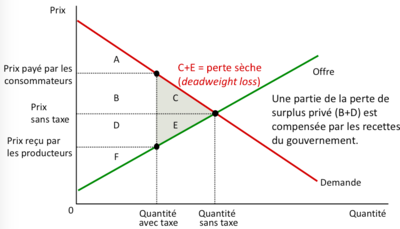

L'introduction d'une taxe sur un marché réduit le surplus total, qui est la somme du surplus du consommateur (SC) et du surplus du producteur (SP). Le mécanisme de ce phénomène est le suivant :

- Surplus du Consommateur : La taxe augmente le prix que les consommateurs paient pour le bien ou le service, ce qui réduit leur surplus. Ils paient plus pour chaque unité, et certains consommateurs pourraient choisir de ne plus acheter le bien en raison de son coût supplémentaire, perdant ainsi l'utilité qu'ils auraient autrement tirée de sa consommation.

- Surplus du Producteur : En même temps, la taxe diminue le prix net que les producteurs reçoivent après impôts. Cela réduit leurs incitations à produire et vendre, ce qui diminue leur surplus. La réduction des quantités produites et vendues peut également entraîner une perte d'efficience productive.

La perte combinée de surplus du consommateur et du producteur est souvent illustrée par un triangle de perte sèche sur un graphique de l'offre et de la demande. Cette perte sèche représente la perte de bien-être économique qui ne profite ni aux consommateurs, ni aux producteurs, ni même au gouvernement : elle est simplement une perte d'efficience due à la taxe.

Revenu du Gouvernement (SG)

D'un autre côté, la taxe génère des revenus pour le gouvernement (SG), qui est le produit de la taxe par unité multiplié par le nombre d'unités vendues après l'imposition de la taxe. Cet argent peut être utilisé pour financer des services publics, des investissements dans l'infrastructure, l'éducation, la santé, ou pour redistribuer des ressources dans le cadre de programmes sociaux. Ainsi, bien que la taxation réduise le surplus total du marché, elle permet d'accomplir des fonctions gouvernementales qui peuvent, à leur tour, avoir un impact positif sur le bien-être social.

L'efficacité globale d'une taxe, en termes de compromis entre la perte de bien-être du marché et les avantages des dépenses gouvernementales, dépend de la manière dont les fonds sont utilisés. Si les revenus de la taxe sont dépensés de manière à améliorer le bien-être global ou à corriger d'autres inefficacités du marché (comme les externalités négatives), l'impact net de la taxation peut être positif. En revanche, si les revenus sont mal gérés ou dépensés de manière inefficace, l'effet net peut être une diminution du bien-être social.