« The independence of the United States » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 99 : | Ligne 99 : | ||

Unity between the colonies was essential to their collective success against Britain. The dynamics between the northern and southern colonies, with their economic, social and cultural differences, could have been a breaking point in the quest for independence. However, the appointment of George Washington, a Virginian, as commander-in-chief was a strategic manoeuvre to strengthen this unity. Virginia was the largest and wealthiest of the colonies, with considerable influence in colonial politics. Having a Virginian at the head of the Continental Army sent a strong message that the revolutionary effort was not simply a Northern colonial affair, but a pan-American movement. The Northern colonies, particularly Massachusetts, were at the centre of many anti-British protests and movements, such as the Boston Tea Party and the Battle of Lexington. To succeed, however, the independence movement had to transcend regional boundaries. The choice of Washington to lead the army ensured that the South would be invested in the cause, not only politically and economically, but also militarily. George Washington's appointment was not only based on his individual qualities, but was also part of a wider strategy to unite and mobilise all of the Thirteen Colonies in their fight against British rule.[[Fichier:Declaration independence.jpg|thumb|center|400px|The presentation of the final text of the declaration to Congress.Painting by John Trumbull.]] | Unity between the colonies was essential to their collective success against Britain. The dynamics between the northern and southern colonies, with their economic, social and cultural differences, could have been a breaking point in the quest for independence. However, the appointment of George Washington, a Virginian, as commander-in-chief was a strategic manoeuvre to strengthen this unity. Virginia was the largest and wealthiest of the colonies, with considerable influence in colonial politics. Having a Virginian at the head of the Continental Army sent a strong message that the revolutionary effort was not simply a Northern colonial affair, but a pan-American movement. The Northern colonies, particularly Massachusetts, were at the centre of many anti-British protests and movements, such as the Boston Tea Party and the Battle of Lexington. To succeed, however, the independence movement had to transcend regional boundaries. The choice of Washington to lead the army ensured that the South would be invested in the cause, not only politically and economically, but also militarily. George Washington's appointment was not only based on his individual qualities, but was also part of a wider strategy to unite and mobilise all of the Thirteen Colonies in their fight against British rule.[[Fichier:Declaration independence.jpg|thumb|center|400px|The presentation of the final text of the declaration to Congress.Painting by John Trumbull.]] | ||

= | = The Declaration of Independence = | ||

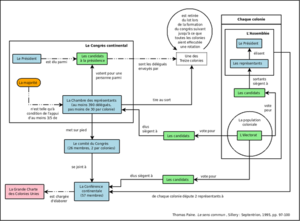

[[Image:Constitution-etats-unis-thomas-paine.png|thumbnail|300px|right|Constitution | [[Image:Constitution-etats-unis-thomas-paine.png|thumbnail|300px|right|Constitution of the United States as proposed by Thomas Paine in Common Sense, 1776]] | ||

George Washington a | George Washington faced countless challenges as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. Not only did he have to lead a largely inexperienced and ill-equipped army, but he also had to inspire and maintain the morale of the troops in the face of formidable adversity. Moreover, it was essential to rally the support of the civilian population, for an army is only as strong as the support it receives from its population. | ||

In this context, the work of Thomas Paine, in particular his pamphlet Common Sense, was decisive. Published in January 1776, Common Sense challenged the authority of the British king and advocated the idea of an independent American republic. His clear and forceful arguments galvanised the American public, changing the way many colonists perceived their relationship with Britain. Paine's impassioned prose provided compelling arguments for the need for independence, and helped to highlight the injustices of British rule. While political debates can often seem abstract or remote to the average citizen, Paine had the talent to make his arguments accessible to a wide audience, helping to strengthen popular support for the revolutionary cause. While Washington fought on the battlefield, consolidating the Continental Army and engaging British troops, Paine fought on the ideological front, arming the colonists with the arguments and determination needed to sustain the war. Both men, each in their own way, played crucial roles in the colonies' path to independence. | |||

Thomas Paine, | Thomas Paine, with "Common Sense", had a remarkable impact on the collective consciousness of the American colonists. In this incendiary work, Paine defied conventional logic and directly challenged the legitimacy of British rule over the American colonies. Using simple, direct language, he appealed to the reason and common sense of the average citizen, debunking the idea that the British monarchy was beneficial or even necessary for the good of the colonies. The sentiment Paine expressed - that the time for negotiations was over and the time had come for a clean break - resonated deeply with many colonists. The speed with which the pamphlet sold is testament to its influence. In an age without internet or television, the viral spread of a publication such as 'Common Sense' was a remarkable feat. To put this into perspective, if we proportioned the sale of 120,000 copies to the current population of the United States, it would be equivalent to several million copies sold today. As delegates debated the merits of the Declaration of Independence at the Second Continental Congress, the atmosphere was charged with anticipation and uncertainty. Against this backdrop, Paine's work provided welcome clarity, an impassioned call to action, strengthening the resolve of the leaders to move towards independence. The combination of the ideals set out in Common Sense and the growing desire for self-determination eventually led to the Declaration of Independence, a watershed in world history. | ||

The socio-cultural context of the colonies was unique in many ways. One of these distinctive aspects was the astonishingly high literacy rate among the colonists, particularly in comparison with other parts of the world at the same time. This erudition paved the way for the rapid and effective spread of ideas, particularly through printed literature. Thomas Paine's pamphlet "Common Sense" fell squarely into this knowledge-hungry society. The ability of the colonists to read, understand and discuss the contents of the pamphlet amplified its impact. Taverns, public squares and churches became lively discussion forums where Paine's arguments were debated, defended and dissected. The confluence of revolutionary ideas and events on the ground created an electric atmosphere. As news of early military victories, such as the British withdrawal from Boston, reached Philadelphia, it strengthened the case for independence. The Second Continental Congress, already inclined towards a break with Britain, was galvanised by these developments. In this dynamic context, Paine's work was not simply a call to action; it was a catalyst, accelerating a movement that was already underway. His powerful rhetoric, combined with the changing reality on the battlefield, created a synergy that eventually led to the colonies' declaration of independence and their quest to form a new nation. | |||

On 4 July 1776, a date now engraved in American history, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, marking a decisive turning point in relations between the colonies and the British crown. This bold decision was not the result of a moment's impetus, but the culmination of years of frustration, tension and confrontation with Great Britain. The document itself, mainly the work of Thomas Jefferson, with contributions and modifications by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and others, is more than just an announcement of separation. It articulates the philosophy behind the decision, based on the principles of the Enlightenment. Jefferson masterfully articulated the belief that all men are created equal, endowed with inalienable rights, including those to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. With this proclamation, the colonies were not simply severing their ties with Great Britain; they were establishing a new order based on the ideals of freedom, equality and democracy. The Declaration of Independence was not just an act of rebellion, but a bold vision of a new kind of government and society that would continue to influence freedom and human rights movements around the world. | |||

The American Declaration of Independence is a founding text and a bold proclamation of the principles underpinning the new nation. Its preamble evokes a universal truth, stating that "all men are created equal". This is not simply an affirmation of physical or intellectual equality, but rather a recognition of the intrinsic dignity and rights of each individual. By stating these rights as "inalienable", the Declaration recognises that these rights are not granted by government, but are inherent in human nature. Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are fundamental rights that each person possesses simply by being born. It is also clearly stated that the primary role of government is to guarantee and protect these rights. More than that, the Declaration offers a radical justification for revolution and rebellion. It posits that if a government fails to respect or violate these fundamental rights, it loses its legitimacy. In such circumstances, the people not only have the right, but also the duty, to seek to change, or even overthrow, that failing government in favour of a system that better protects their rights and freedoms. This philosophy not only laid the foundations for the American Revolution, but also influenced many other liberation and reform movements around the world. | |||

The Declaration of Independence, with its powerful language and profound principles, represented a bold departure from the political conventions of its time. While monarchy, hierarchy and the divine right of kings were still dominant norms in Europe, the American colonists proposed an alternative model: a government based on the consent of the citizens, where power was derived from the will of the people. The idea that all individuals possessed inalienable rights, regardless of their status or birth, was revolutionary. The notion that these rights could be defended against an oppressive government, and that the people had a moral right to resist and reshape that government, laid the foundations for a new political order. The influence of these ideas was not limited to the borders of the fledgling United States. Revolutionaries in France, Latin America, Europe and elsewhere drew on the Declaration's rhetoric and principles to support their own struggles for freedom and justice. Its call for freedom, equality and popular sovereignty echoed in the farthest corners of the world, spurring movements for human rights, democracy and national self-determination. Indeed, the Declaration of Independence became much more than a proclamation of autonomy for a new nation. It has become a beacon, lighting the way for all those who aspire to freedom and human dignity. Its legacy lives on not only in American institutions and values, but also in the inspiration it continues to offer to generations of human rights defenders around the world. | |||

The Declaration of Independence was both a proclamation of self-government and an indictment of the British Crown. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it listed a series of grievances against King George III, showing how he had regularly violated the rights of the colonists, calling into question the ideals of justice and representative government that the colonists cherished. The charges against the King served to illustrate an oppressive model of governance, in which the fundamental rights of citizens were regularly trampled underfoot. For example, the King had imposed taxes without the colonists' consent, housed troops in their homes without their permission and dissolved their legislatures. But the Declaration didn't just criticise; it also set out a vision. It presented a conception of universal human rights, and the idea that governmental power should be based on the consent of the governed. When government betrays this principle, the document declared, the people have not only the right but also the duty to overthrow it. The reference to "divine providence" reinforces the idea that the actions of the colonies were not only politically justified, but also morally and spiritually justified. This invocation of divine providence suggested that the quest for independence was in harmony with natural and universal laws, and that the colonists' fight for freedom was just and legitimate in the eyes of God. The strength of the Declaration of Independence lies not only in its accusations against a king, but in its universal call for justice, freedom and self-determination. By defining the right of peoples to govern themselves, it set a precedent that would inspire movements for human rights and freedom around the world for generations to come. | |||

The Declaration of Independence established a bold proclamation of autonomy for the American colonies. By declaring their right to "make peace, enter into alliances, and carry on commerce", it claimed all the prerogatives of a sovereign nation. These rights are not just privileges reserved for empires or world powers, but essential attributes of any autonomous political entity. Explicitly stating these rights was a way for the colonies to signify their complete and definitive break with Great Britain. They sought not only to free themselves from a tyrannical crown, but also to assume all the roles and responsibilities that come with sovereignty. By turning to the "supreme judge of the world", the drafters of the Declaration were invoking a higher moral and spiritual authority to justify their quest for independence. They were suggesting that their cause was not only political, but also ethically and universally justified. This transcendental reference reinforced the idea that independence was not simply a matter of convenience or expediency, but a moral imperative. By asking for "the protection of divine providence", the signatories were demonstrating their faith in a higher power that they hoped would guide them in their fight for freedom. It was both an affirmation of their deep conviction that their cause was just and an acknowledgement of the uncertainty and challenges they were about to face. In short, the Declaration of Independence, while a political document, was also imbued with spirituality, reflecting the hopes, beliefs and profound convictions of its drafters and signatories. | |||

The Declaration of Independence, for all its eloquence and philosophical significance, was in reality only the beginning of a long and ardent struggle for autonomy. This bold proclamation by no means guaranteed success. The simple declaration of independence was not enough; it had to be defended and won on the battlefield. The American War of Independence, which followed the Declaration, was a long and costly ordeal for the colonies. It demonstrated the determination and resilience of the Americans in the face of one of the greatest world powers of the time. The war was marked by victories, defeats, betrayals and countless sacrifices. It is also interesting to note that while the war raged, there was a great deal of international scepticism about the viability of the United States as an independent nation. Many nations watched cautiously, reluctant to officially recognise this new nation until they were certain of its ability to stand up to Britain. It was not until the victory at Yorktown in 1781, largely aided by the French, that Britain finally recognised that the war was lost. The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783, sealed this recognition. Not only did it recognise the United States as a sovereign nation, it also established favourable borders and granted significant fishing rights to the Americans. So although the Declaration of Independence was a pivotal moment in American history, it was only the beginning of an ordeal that would test the determination, unity and courage of the young nation. | |||

The American Declaration of Independence is one of the most influential texts in modern history. Using the language of natural rights, it set out the philosophy that individuals are born with inalienable rights, and that these rights are not granted by government, but exist independently of it. It is an idea that, although it has roots in the writings of thinkers such as John Locke, was expressed so directly and powerfully in the Declaration that it resonated deeply in the collective consciousness. Equally revolutionary was the notion that a government derives its legitimacy only from the "consent of the governed". It overturned the traditional logic of sovereignty, according to which monarchies ruled by divine right or by force. Instead, the Declaration argued that the people were the true source of power and that, if a government violated the rights of the people, it was not only the right but also the duty of the people to overthrow or change it. This idea had a worldwide impact. The concepts set out in the Declaration of Independence inspired, directly or indirectly, other revolutionary movements, such as the French Revolution, as well as independence movements in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Moreover, the language and ideas of the Declaration continue to be cited and invoked by defenders of human rights, democracy and self-determination around the world. The Declaration of Independence has become a universal symbol of freedom and resistance to oppression. | |||

Although the Declaration of Independence was a pioneering work, it carried with it the contradictions and limitations of the times in which it was written. The tension between the stated ideal that "all men are created equal" and the practical reality of a society that marginalised and oppressed large segments of its population is one of the great paradoxes of American history. Many of the Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, the principal drafter of the Declaration, owned slaves. These men fought for their own liberation from colonial rule while simultaneously depriving other human beings of their freedom. This contradiction was not only evident at the time, but has persisted throughout American history, provoking debate, division and, ultimately, civil war. Similarly, women, despite their crucial role in colonial society, were largely excluded from political deliberations and did not enjoy the same rights and protections as their male counterparts. Their struggle for equal rights would not gain ground until the nineteenth century and would continue throughout the twentieth century. Native Americans, who lived on the continent long before the arrival of Europeans, were largely ignored in the conversation about independence and rights, even though their land was often at the heart of conflicts between settlers and the British crown. In examining the Declaration of Independence through the prism of the 21st century, it is essential to contextualise it. It was a monumental step towards the idea of freedom and human rights, but it was also an imperfect product of an imperfect time. The struggles for inclusion, justice and equality that followed are testament to the document's limitations, but also to its inspiring potential. | |||

The Declaration of Independence, drafted in 1776, was a product of its time, marked by the aspirations, prejudices and contradictions of the era. It symbolises both the noblest ideals of the Enlightenment, such as freedom, equality and inalienable rights, and the less glamorous realities of a colonial society that practised slavery, marginalised women and dispossessed the indigenous population. The document itself is a bold proclamation against tyranny and for self-determination. But at the same time, it reflects the limitations of its time. For example, when Jefferson wrote that "all men are created equal", he did not take into account the people enslaved on his own plantations or the women who, for decades, would not have the same political rights as men. However, despite its shortcomings, the Declaration of Independence has served as a landmark and inspiration for countless civil rights and liberation movements throughout history, not only in the United States but throughout the world. It laid the foundations for a nation that, while imperfect, constantly aspires to achieve its declared ideals. In reading it today, we are reminded of the importance of civic vigilance, of the constant evolution of democracy, and of the need to defend and expand rights for all. The Declaration is a testament to human hope and determination, a document that, while rooted in its time, transcends time to inspire future generations. | |||

= | = Continuation of the war = | ||

The American War of Independence, also known as the American Revolution, arose from growing tensions between the residents of the Thirteen British Colonies in North America and Great Britain. These tensions centred mainly on issues of representation and taxation, culminating in the colonists' famous rallying cry: "No taxation without representation". The first shots of this decisive war were fired on 19 April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. These initial clashes set the tone for a conflict that was to divide not only Great Britain and its colonies, but also the colonists themselves. On one side were the Patriots, mainly composed of the Continental Army, who wanted independence and freedom. Opposing them were the Loyalists, colonists who chose to remain loyal to the British Crown, supported by the British regular army. As the war progressed, the Patriots found unexpected allies. The Battle of Saratoga in 1777, often considered the turning point of the war, led to a formal intervention by France on behalf of the Americans. The French provided essential military and financial support, while other European nations, including Spain and the Netherlands, also challenged Britain by opening other war fronts. Among the most notable battles, in addition to the first ones at Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Saratoga and Yorktown stand out. Yorktown, in particular, saw the last major confrontation of the war in 1781. Here, British troops under the command of General Cornwallis were besieged and eventually forced to surrender by an alliance of American and French troops. The war, however, did not end immediately after Yorktown. Sporadic fighting continued until 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was signed. This treaty marked the official end of the conflict, with Great Britain finally recognising the independence of the United States. This war, with its republican and democratic ideals, left a lasting legacy, inspiring many independence movements and revolutions in the years that followed. | |||

The American War of Independence was an arduous ordeal for the young United States. Often outnumbered and under-resourced, the Continental Army, made up mainly of militiamen and volunteers, found it difficult to stand up to the well-organised military might of Great Britain. The strength of this army fluctuated, most of the time between 4,000 and 7,000 men. Many of these soldiers were inexperienced, ill-equipped and untrained in conventional war tactics. In addition, logistical difficulties, including shortages of supplies and food, often undermined the morale of the troops. In contrast, the British Army was strong and well-funded, boasting up to 35,000 soldiers at certain times during the conflict. This impressive force was not made up entirely of Britons. The United Kingdom also used mercenaries, mainly Germans (often called "Hessians"), but also troops from other European countries, such as Ireland and, to a lesser extent, Russia. These forces were professional and well-trained, and had the advantage in terms of both discipline and equipment. The obvious inequality between these two forces made the colonists' fight all the more impressive. Every victory won by the Continental Army, whatever the cost, became a symbol of determination and resilience in the quest for independence against a far superior enemy. | |||

The American War of Independence saw the emergence of a new style of fighting. While the British army was accustomed to conventional line formations and traditional battle tactics, American troops often adopted less conventional methods. Inspired in part by indigenous tactics and frontier experiences, American forces employed guerrilla tactics, hiding in forests, launching surprise attacks and withdrawing quickly before British troops could mount a counter-offensive. These tactics created a war of attrition against the British, making each advance costly in men and resources. Ambushes and lightning attacks not only inflicted casualties on the British army, but also sapped its morale, turning what should have been a straightforward military campaign into a prolonged and gruelling conflict. Despite their numerical inferiority and the many challenges they faced, the American troops managed to win decisive victories at key moments, notably at Saratoga and, finally, at Yorktown. These triumphs not only strengthened American resolve, but also convinced foreign powers, particularly France, to support the American cause. The British surrender at Yorktown in 1781, orchestrated by a combination of American and French forces, marked the effective end of the fighting and paved the way for American independence.[[File:Surrender of Lord Cornwallis.jpg|thumb|Capitulation of Cornwallis at Yorktown - John Trumbull (1820).]] | |||

[[File:Surrender of Lord Cornwallis.jpg|thumb|Capitulation | |||

During the American War of Independence, the British used the issue of slavery as a strategic tool against the colonists. Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation in 1775 that promised freedom to any slave who joined British forces to fight against the insurgents. The proclamation was designed to weaken support for the revolution, while destabilising the slave-based economy of the colonies. The promise of freedom from the British prompted many slaves to escape from their masters and join the British ranks in the hope of gaining their freedom. Some were used as labourers, others as soldiers. However, the reality was often different from the promises: many faced discrimination within the British army or were returned to slavery after being captured by American forces. However, it is also important to note that the patriot cause itself was not uniformly anti-slavery. While some revolutionaries criticised slavery and even took steps to abolish it in the Northern states, others defended the institution and continued to own slaves long after the war. The British were not alone in promising freedom to slaves. Patriots, particularly in the North, also offered freedom in exchange for military service. Ultimately, the Revolutionary War created opportunities and challenges for slaves who yearned for freedom, but it did not end the institution of slavery in the United States, an issue that would remain unresolved until the Civil War nearly a century later. | |||

The American War of Independence provided an unhoped-for opportunity for some slaves to break free from the shackles of servitude. Faced with colonial resistance, the British devised a strategy to weaken the insurgents by offering freedom to slaves who would abandon their masters to join the British ranks. This was a shrewd tactic, as it not only deprived the colonies of a valuable workforce, but also created internal divisions and disrupted the colonial economy. Driven by the hope of a better life and the promise of freedom, many slaves took the bold decision to escape, braving the risks and uncertainties that lay ahead. However, once integrated into the British Army, many discovered that the reality did not always match the promise. Instead of taking up arms as fully-fledged soldiers, many were relegated to support roles such as porters, cooks or labourers. This use of black labour reflected the racial prejudices of the time and doubts about the loyalty and fighting ability of these new recruits. However, this does not mean that all the slaves who joined the British were confined to menial roles. Some were able to fight alongside their British comrades, albeit often under unequal conditions. But even for these soldiers, the promised rewards - particularly freedom - were not guaranteed. Some were betrayed by the British at the end of the war, sold back into slavery or abandoned to their fate. Despite these challenges and betrayals, the decision of these slaves to seek freedom in the midst of war is a testament to their courage, determination and unwavering desire for freedom. | |||

The British promise of freedom to slaves during the American War of Independence was as much a military strategy as a moral appeal, and the reality that followed for many slaves was not what they had hoped for. From the outset, the British proclamation offering freedom to slaves had a clear strategic purpose: to weaken support for the rebellion by depriving the colonists of valuable labour and creating internal divisions. But the promise of freedom, once made, became a powerful magnet for many slaves who aspired to emancipation. However, while some were freed, many others faced betrayal and disappointment. At the end of the war, when the British were forced to evacuate their colonial strongholds, they were faced with the dilemma of what to do with the freed slaves who had joined them. Although some were taken to Britain, many were left behind, where they risked re-slavery. Others were deported to other British colonies, particularly in the Caribbean. There, instead of the freedom they had so long hoped for, they were sold to new masters, returned to the horrors of slavery, but this time far from their homeland. The sad irony is that the promise of freedom led many slaves to a fate perhaps worse than the one they had fled. This episode highlights the complexities and contradictions of the War of Independence, where ideals of freedom coexisted with the brutal realities of slavery and discrimination. | |||

The British offer of freedom to slaves was not motivated by altruistic principles or moral opposition to slavery, but rather by strategic and military considerations. The American War of Independence posed many challenges for the British, who were fighting not only colonial rebels but also the logistical and geographical constraints of waging war on a distant continent. Slave recruitment was a sign of the growing pressure the British were feeling. Faced with recruitment challenges in Britain and long supply lines, they sought to exploit internal divisions in the colonies. Slaves, with the promise of freedom, represented a potential resource, even if most of them were not used as front-line combatants. It is also crucial to understand that the context of the British offer was that of an empire that had benefited greatly from slavery. British economic interests were deeply linked to the slave system, particularly in the sugar plantations of the Caribbean. The offer of freedom to slaves during the American War of Independence was therefore pragmatic and opportunistic, rather than a challenge to the foundations of slavery itself. It is a poignant illustration of the complexities of this war, where principle, strategy and expediency intertwined, influencing the course of history for many people and, ultimately, for the nation that would emerge from this conflict. | |||

France's involvement in the American War of Independence was decisive in the outcome of the conflict in favour of the American colonists. Although French motives were partly based on opposition to British tyranny, they were just as much, if not more, influenced by a strategic desire to gain the upper hand over Great Britain, their age-old enemy. France's humiliation at the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Seven Years' War, was still fresh in the French memory. Consequently, the chance to recover some of its lost prestige and weaken British power was too tempting for France to ignore. France's aid was not limited to proclamations of support: it provided troops, a naval fleet, arms, equipment and crucial finances to the American rebels. The Battle of Saratoga in 1777 is often cited as a turning point in the war, not only because it was a major victory for the colonists, but also because it convinced France that the Americans were a force to be reckoned with, leading to a formal alliance in 1778. French involvement balanced the forces on the battlefield, particularly at the decisive Siege of Yorktown in 1781, which led to the British surrender and essentially ended hostilities. France's involvement also internationalised the conflict. With France openly entering the war, other European powers, such as Spain and the Netherlands, also took up positions, creating new fronts and diverting British attention from North America alone. Ultimately, without the military, financial and diplomatic support of France, it is hard to imagine that the American colonists could have achieved a complete victory as quickly as they did against the mighty Great Britain. | |||

The collaboration between the Comte de Rochambeau and General George Washington was crucial in coordinating the combined efforts of the French and American armies. The two commanders developed a relationship of mutual respect and jointly devised strategies to counter the British. One of Rochambeau's most notable contributions was his professional military experience. The Europeans, particularly the French, had developed sophisticated war tactics and Rochambeau shared this expertise with Washington, raising the level of competence and efficiency of the Continental Army. But it is the siege of Yorktown in 1781 that is the most striking testimony to the importance of French intervention. Rochambeau, Washington and the French admiral de Grasse, who commanded a vital fleet in Chesapeake Bay, worked closely together to surround and besiege the British army under the command of General Cornwallis. The coordination of American and French land forces, combined with French control of the waters, made the British position untenable. Cornwallis was forced to surrender, marking a decisive turning point for the colonies in their quest for independence. Without the presence and support of the French expeditionary corps led by Rochambeau, and without de Grasse's naval command, the victory at Yorktown - and perhaps the final victory in the war - would have been much harder to achieve. France's participation, in the form of troops in the field and a fleet in American waters, not only helped the colonies to balance the balance of power, but also gave new impetus and confidence to the American war effort. | |||

French naval superiority, orchestrated by Admiral de Grasse in Chesapeake Bay, was a key part of the strategy that led to the British surrender at Yorktown. During this period, control of the seas was essential in determining the outcome of major conflicts, and the siege of Yorktown was no exception. The timely arrival of de Grasse's fleet thwarted British plans and blocked any hope of maritime reinforcements for Cornwallis. De Grasse's ability to maintain this position ensured that Cornwallis would remain isolated and vulnerable to the combined approach of French and American land forces. But the role of the French navy was not limited to blocking British reinforcements. French ships also helped transport troops, supplies and ammunition, bolstering the Patriotes' war effort on land. Ultimately, Franco-American cooperation, both on land and at sea, created a formidable alliance that turned the tide of the war. The Battle of Yorktown itself, although symbolically seen as an American victory, was in reality the fruit of a joint effort, in which French military and naval expertise played a decisive role in the trap that was set for the British. Without this collaboration, the war could have had a very different outcome. | |||

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 was the culmination of a series of negotiations between the United States, Great Britain, France and other European powers. It formally ended the American War of Independence and recognised the sovereignty of the United States over a vast territory stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River in the west, and from Canada in the north to Spanish Florida in the south. The French contribution to the American war effort cannot be underestimated. It went far beyond the supply of troops and military equipment. France used its influence in Europe to win support for the American cause and to dissuade other powers from allying themselves with Great Britain. It also played a key role in negotiating the treaty itself, ensuring that US interests were protected at the negotiating table. The impact of this French assistance is clearly visible in the outcome of the war. The combined forces of France and the United States were able to defeat a militarily superior colonial power. Ultimately, France's decision to enter the war alongside the United States not only changed the course of the war, but also redefined the balance of power in North America. The Treaty of Paris was therefore the crowning achievement of a successful alliance and the beginning of a new era for a fledgling nation. It symbolised the transition from rebellion to sovereignty, consolidating the United States as an independent entity on the world stage. | |||

The American War of Independence, which lasted from 1775 to 1783, was a major episode in world history that led to the birth of a new nation. Although the war began in 1775 with confrontations such as the battles of Lexington and Concord, it was in 1776 that the colonies made a bold declaration of independence, signifying a definitive break with the British crown. Several factors contributed to this rapid victory compared with other independence movements. Firstly, the crucial support of France was invaluable. Not only did France provide essential financial and material resources, it also sent ground troops and naval power. The combined efforts of France and the United States succeeded in encircling and defeating the British forces at Yorktown, a decisive victory that essentially ended the fighting. The military strategy of the Continental Army also played a vital role. Under the leadership of General George Washington, the Continental Army adopted a flexible approach, often using guerrilla tactics to stand up to the much larger and better equipped British Army. These tactics enabled the American troops to avoid heavy losses while inflicting considerable damage on the enemy. Finally, the unwavering determination of the American Patriots was a key factor in this victory. Despite the challenges, setbacks and difficult times, the desire for freedom and independence continued to inspire American combatants, driving them to resist and fight for their rights. The American War of Independence was an uphill battle, but thanks to strategic alliances, innovative tactics and unwavering determination, the United States succeeded in gaining its independence in less than a decade. This laid the foundations for a nation that would play a central role on the world stage for centuries to come. | |||

After the euphoria of victory over Great Britain, the United States faced the complex reality of nation-building. A fledgling democratic republic required a robust governmental structure. The adoption of the Articles of Confederation in 1777 initially served as a constitution, but its inherent weaknesses led to the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1787, which laid the foundations of the federal government as we know it today. The expansionist ambitions of the United States became evident in the early nineteenth century. The purchase of Louisiana from France in 1803 doubled the size of the country, opening up huge swathes of territory to the west for exploration and colonisation. This acquisition, made under the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, was central to the American vision of "manifest destiny", the idea that the United States was destined to expand from coast to coast. The annexation of Texas in 1845, closely followed by the war with Mexico, reflected this expansionist vision. At the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded much of northern Mexico to the United States, including the present-day states of California, Arizona, New Mexico and others. However, this rapid expansion was not without consequences. Indigenous peoples, who had lived on these lands for thousands of years, faced violence, deception and dispossession. US government policies, including the Indian Removal Act of 1830, resulted in the forced removal of many Native American tribes from their ancestral lands to territories west of the Mississippi, a tragic event often referred to as the "Trail of Tears". These policies of expansion, while enriching the United States, left a legacy of injustice and trauma for the indigenous peoples. | |||

The end of the War of Independence marked the beginning of an era of intense challenge for the United States. With independence secured, the nation was faced with a multitude of internal dilemmas that threatened its cohesion. The issue of slavery, in particular, was deeply divisive. Although the Declaration of Independence proclaimed that "all men are created equal", slavery was deeply entrenched, particularly in the Southern states. Some of the Founding Fathers themselves owned slaves, creating a glaring contradiction between the proclaimed ideals of freedom and equality and the reality of oppression and dehumanisation. Slavery became a central issue when the Constitution was drafted in 1787. Compromises, such as the Three-Fifths Compromise, were made to maintain a precarious balance between slave-holding and non-slave-holding states. But these compromises were only temporary solutions to an ever-worsening problem. As the nation expanded westwards, the question of whether new territories would become slave or non-slave states exacerbated tensions. Events such as the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 attempted to maintain this delicate balance. At the same time, governing such a vast and diverse nation posed its own challenges. Tensions between states' rights and federal power led to heated debates over the interpretation of the Constitution and the scope of federal authority. The convergence of these issues, particularly the question of slavery, culminated in the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. His anti-slavery stance led several Southern states to secede, triggering the Civil War in 1861. It would be the deadliest war in American history, and would ultimately test the nation's resilience and determination to forge a unified identity. | |||

= | = Revolution or reaction? = | ||

Les historiens débattent actuellement de la question de savoir si la Révolution américaine doit être considérée comme une véritable "révolution" ou simplement comme une réaction conservatrice à la domination britannique. | Les historiens débattent actuellement de la question de savoir si la Révolution américaine doit être considérée comme une véritable "révolution" ou simplement comme une réaction conservatrice à la domination britannique. | ||

Version du 3 août 2023 à 16:08

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The independence of the United States, a landmark event in world history, was the result of a daring quest by the thirteen British colonies in North America to free themselves from the yoke of the British Empire. These colonies evolved over the decades, cultivating a sense of identity of their own, although still under British rule. Their common aspiration for autonomy found its most eloquent expression in the Declaration of Independence, adopted on 4 July 1776. In this document, they resolutely asserted their right to govern themselves, proclaiming their emancipation from the British crown.

However, to understand this transition to independence, we need to delve into the historical intricacies and underlying movements that shaped this period. Two major factors in particular influenced this period: the Seven Years' War and the Age of Enlightenment. The Seven Years' War, often referred to as the French and Indian War on the American continent, drained British coffers, forcing the metropolis to impose heavier taxes on its colonies across the Atlantic. This tax burden, juxtaposed with Enlightenment ideals of inalienable rights and individual liberties, fuelled growing frustration among the colonists.

Britain's attempts to consolidate its hold on the colonies, through measures such as the Quartering Acts and the Proclamation of 1763, only served to exacerbate these tensions. These acts, perceived as affronts to the freedom of the colonists, were the catalyst for a growing desire for independence, culminating in the revolution that led to the birth of a nation that would influence the course of world history.

The causes of independence

The demographic growth and territorial expansion of the American colonies in the 18th century were key precursors to the independence of the United States. The population explosion, which saw the territory grow from 300,000 inhabitants in 1700 to 2.5 million in 1770, generated socio-economic and political dynamics that influenced the trajectory of these colonies.

Firstly, this rapid population growth led to increased pressure on land and resources. The settlers, eager to expand their agricultural territories, looked westwards to the lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains. However, these territorial ambitions were hampered by British policies, notably the Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited settlers from settling west of these mountains to avoid conflict with the indigenous peoples. This restriction, perceived as an impediment to the freedom and prosperity of the colonies, exacerbated tensions between the colonists and the metropolis. Rapid population growth also gave rise to distinct regional identities. The North, with its expanding cities and diversified economy centred on trade, fishing and crafts, developed an identity distinct from that of the South, which was mainly agrarian and dependent on plantations exploiting slave labour. These distinctions created different world views and, although the colonies joined forces to achieve independence, these regional identities continued to influence the formation of the nation and its politics.

During the 18th century, the American colonies became a melting pot of identities and cultures. While Britain was the main source of immigration, a steady stream of people from other parts of Europe - notably Germany, Ireland, France, the Netherlands and elsewhere - came to America in search of new opportunities. These immigrants, often driven by religious persecution, conflict or simply the search for a better life, enriched the colonies with their customs, languages, farming practices and craft traditions. The Germans, for example, who settled mainly in Pennsylvania, became renowned for their farming and building skills. The Irish, fleeing poverty and religious oppression, brought with them a strong determination and musical traditions that became part of the colonial culture. This influx of cultural diversity led to an increased sense of pluralism. The colonies were no longer simply an extension of Britain; they were a mosaic of peoples from across the continent of Europe, each helping to shape the cultural, social and economic landscape of the emerging America. This diversity also reinforced the colonies' sense of self-identity. While political and economic institutions were largely modelled on the British model, people's everyday lives reflected a fusion of traditions. It became increasingly clear that, although loyal to the Crown, the colonies had developed a distinct, complex and plural identity. Consequently, as political tensions intensified with Britain, this unique identity became central to the claim for autonomy. The colonists were not simply British subjects living overseas; they were a diverse community with their own aspirations and visions for the future, which inevitably contributed to their desire for independence and the formation of a new nation.

The Seven Years' War, a world war before its time, had lasting consequences not only for the European powers involved, but also for the fate of the American colonies and the indigenous nations. With the British victory, the Treaty of Paris of 1763 marked a turning point in the dynamics of colonisation in North America. The British acquired immense territories, mainly at the expense of France, thus consolidating their hegemony on the continent. But this victory was not without its complications. Firstly, the lands west of the Mississippi River, although officially under British control, were still largely inhabited by indigenous nations. These nations, although weakened by the war, were not prepared to cede their lands without resistance. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, which sought to ease tensions with the native nations by prohibiting settlement west of the Appalachians, was in part a response to these challenges. However, for ambitious settlers seeking to expand their lands, this proclamation was seen as a betrayal of the crown, hindering their right to settle on land they considered to have been duly earned. Secondly, the war left Britain with a colossal debt. To recover some of these expenses, the British government imposed a series of taxes on the colonies, such as the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts. These taxes, which were levied without the direct consent of the colonies (a violation of the principle of "no taxation without representation"), aroused deep discontent and fuelled the flames of revolution. Finally, the end of the French threat in North America paradoxically made the British Empire less essential in the eyes of some colonists. Previously, the British presence had offered vital protection against French incursions. But with France removed from the North American scene, some settlers began to envisage an independent existence, free from British interference and taxation. While the Seven Years' War strengthened Britain's position as the dominant power in North America, it also planted the seeds of discord and discontent that would eventually lead to the American Revolution.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 played a key role in escalating tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain. It is a decision often underestimated in history, but its implications were profound. The Proclamation was put in place primarily to calm relations with the indigenous nations that had been allied to the French during the war. The British government hoped to avoid further costly conflicts by limiting the expansion of the colonies. However, this decision was not welcomed by the colonists. After years of war, many saw these western territories as the rightful reward for their efforts and sacrifices. In addition, the prospect of new land was attractive to many settlers, whether farmers looking to expand their holdings or speculators looking to profit from westward expansion. The proclamation was therefore seen as a betrayal and a hindrance to their prosperity. This sense of injustice was exacerbated by the fact that the proclamation was issued without consulting the colonial assemblies. For the colonists, this was further proof of Britain's contempt for their rights and interests. The conviction that London was increasingly out of touch with the realities and needs of the American colonies grew stronger. The Proclamation of 1763, coupled with other unpopular measures such as taxes imposed without representation, highlighted a growing schism between the colonists and the British government. It paved the way for the rise of revolutionary sentiment by reinforcing the idea that the interests of the British Empire and those of the American colonies diverged fundamentally.

The end of the Seven Years' War in 1763 marked the beginning of a period of heightened tension between the American colonies and the British government. Wishing to avoid further conflict with the indigenous nations and to reduce military costs, Great Britain introduced the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This directive prohibited settlers from settling west of the Appalachian line, a decision designed to preserve this land for the Amerindians. At the same time, the British government undertook to establish a more structured relationship with the indigenous nations. Rather than allowing settlers to negotiate directly, the British authorities attempted to centralise interactions, resulting in formal agreements. Nevertheless, there were irregularities. In particular, while interactions with the Cherokees were frequent and significant, the Apaches, who lived mainly in the south-west of the present-day United States, were not directly involved in the territorial disputes on the east coast. It is possible that other indigenous nations in the east were more involved in these territorial disputes. Despite these attempts at regulation, settlers, particularly those living on the western frontier, often chose to ignore official directives. Driven by a desire to expand, they acquired territories, sometimes in direct violation of established treaties, which triggered conflicts with the indigenous nations. These tensions and feelings of oppression by British control were major precursors to the events that would lead to the American Revolution.

The end of the Seven Years' War left Britain with a colossal debt. In order to repay this debt, the British government sought to increase its revenues from the North American colonies, which had hitherto been relatively untaxed compared to other parts of the Empire. However, these attempts were met with fierce opposition. Over the decades, the colonies had developed a sense of autonomy. They enjoyed extensive decentralisation and their legislative assemblies often had the final say on internal taxation. So when the metropolis imposed direct taxes without the consent of the colonial assemblies, it was seen not only as a violation of their rights, but also as a challenge to their established mode of governance.

The Stamp Act, introduced in 1765, is a striking example of this discontent. This law imposed a tax on all printed documents in the colonies, from contracts to newspapers. What exacerbated the anger of the colonists was that it was decided without their consent. The famous phrase "No taxation without representation" sounded like a rallying cry among the colonists. The Stamp Act became a symbol of British oppression, highlighting the discrepancy between the colonists' expectations of rights and freedom, and the British government's intentions to strengthen its economic and political control over the colonies. The challenge to the Stamp Act also served as a catalyst for unprecedented inter-colonial cooperation, reinforcing the sense of a distinct American identity and laying the foundations for the organised resistance that would lead to the American Revolution.

The Enlightenment, a period of intellectual and cultural renaissance, had a profound influence on thinkers and leaders throughout the Western world, and the American colonies were not immune to this ferment of revolutionary ideas. These ideas, particularly those concerning human rights and the nature of government, were crucial in shaping the political philosophy of the founding fathers of the United States. John Locke, one of the most influential philosophers of the time, posited that legitimate power could only reside with the consent of the governed. He argued that individuals possess inalienable rights, and that any government that violates these rights loses its legitimacy. These ideas found a powerful echo among the American colonists, particularly those who had received a classical education. The perceived oppression of the British government, with its taxation and regulation without direct representation, was in direct contradiction to these enlightened principles. Moreover, these policies were being implemented at a time when the circulation of ideas was rapid, thanks to the rise of the press and literary salons. Pamphlets, newspapers and books spread the ideas of the Enlightenment, forging a collective consciousness among the colonists around notions such as liberty, justice and democracy.

Figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams were deeply imbued with the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Their writings and speeches reflected an unshakeable belief in the need for a government that protected the rights of the individual. So when tensions with Britain escalated, Enlightenment ideas provided an intellectual and moral basis for colonial resistance. These principles were clearly set out in the Declaration of Independence of 1776, marking the beginning of a new nation founded on the ideals of the Enlightenment, a nation that would be, in Lincoln's words, "conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal".

Reaction of the colonies

The period leading up to the American Revolution was marked by rising tensions between the colonists and the British government. New taxes and regulations, perceived as oppressive, prompted the colonists to actively oppose the metropolis, using a combination of peaceful and direct methods to demonstrate their discontent. One of the first acts of resistance was the drafting of petitions and protests. The colonists, feeling deprived of their right to parliamentary representation, expressed their disagreement by formally requesting the revision or abolition of unpopular laws. These petitions reflected the general sense of injustice felt in the colonies and laid the foundations for the organised opposition to come. In a similar vein, but with direct economic consequences for Britain, economic boycotts were employed. Traders stopped importing British goods, while consumers avoided imported products. This approach hit Britain where it hurt most: their economy. Some British merchants, sensing the pinch, became unlikely allies, urging their own government to ease the restrictions.

However, not all reactions were peaceful. Groups such as the "Sons of Liberty" sometimes crossed the line of civil disobedience and ventured into intimidation or direct violence, particularly against British government officials or Loyalists. These acts, although less frequent, marked a significant escalation in the confrontation with the Crown. The most notorious incident of this nature was the "Boston Massacre" in 1770. This tragic event, in which British soldiers fired on a crowd of demonstrators, killing five of them, became a powerful symbol of the perceived brutality of British rule. It galvanised colonial public opinion and reinforced the desire for independence. As these acts of resistance intensified, the relationship between the colonies and Britain deteriorated, inevitably setting the two parties on the path to the open conflict that would erupt in 1775.

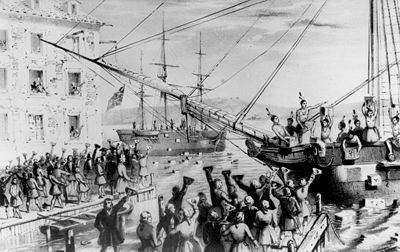

The Boston Tea Party is one of the most famous manifestations of civil disobedience in American history. It is emblematic of the escalation of colonial resistance to British policy. In 1773, the British government granted the British East India Company a virtual monopoly on the tea trade in America, as well as imposing a tax on tea. These measures were seen by many colonists as another blatant example of taxation without representation. The colonies, and Boston in particular, were in an uproar. On 16 December 1773, in response to these unpopular policies, members of the Sons of Liberty movement, disguised as Mohawks to emphasise their American identity and reject their British affiliation, boarded three ships moored in Boston harbour. They took care to vandalise only the tea cargo, throwing 342 chests of tea overboard, while avoiding damage to other property. This was not simply an action against taxes. It was also a protest against a monopoly that was putting many local traders out of business. With this symbolic act, the colonists demonstrated their determination to resist British rule and defend their rights. The British government's reaction to the Boston Tea Party was swift and severe. They imposed the Intolerable Acts, which included the closure of the port of Boston until the tea was paid for and a severe restriction on the autonomy of the colonial government of Massachusetts. These punitive acts only exacerbated tensions, pushing the colonies towards even greater unity against Great Britain. In short, the Boston Tea Party was not just an act of defiance; it symbolised the breaking point, where colonial patience with British rule had reached its limits. It marked a major turning point that led directly to the outbreak of the American Revolution.

The Boston Massacre was a pivotal moment in relations between the colonists and the British government, highlighting the volatility of the tensions simmering in North America. On the night of 5 March 1770, a cold winter's evening in Boston, a British soldier was at his post in front of the customs house. Following an altercation with a colonist, a crowd formed around him, hurling insults, snowballs and various debris. Several other British soldiers were called in to help. The crowd continued to grow and become more hostile. In the ensuing chaos and confusion, the British soldiers opened fire, killing five people and wounding several others. The incident was quickly exploited by the colony's patriot leaders, such as Paul Revere, John Adams and Samuel Adams, who used it to fuel anti-British sentiment. Engravings and descriptions of the confrontation were distributed throughout the colonies, often with a biased narrative, depicting British soldiers as bloodthirsty brutes, deliberately shooting unarmed civilians. John Adams, the future President of the United States, defended the soldiers at their trial, arguing that they had acted in self-defence against a threatening mob. Most of the soldiers were acquitted, reinforcing the idea of a fair judicial system in the colonies. However, the memory of the massacre has remained etched in the collective memory, symbolising for many the brutal repression of the British. The Boston Massacre became a powerful symbol of British tyranny and a catalyst for the unification of anti-British sentiment among the colonists. It was one of many events that eventually led to the Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution.

The Boston Tea Party is not just a memorable page in the history books, but an event that crystallised colonial discontent with a series of British measures perceived as oppressive. In the years leading up to that December night, the colonies had become increasingly frustrated with the metropole's attempts to take control of the colonial economy and impose it in an authoritarian manner. The Tea Act of 1773 was the last straw. Although the Act actually reduced the price of tea, it confirmed Britain's right to tax the colonies without their direct consent. The reaction was swift and dramatic. Under the cloak of night and disguised as Mohawk Indians, a group of activists, including some members of the Sons of Liberty, stormed the British ships. The sound of tea chests breaking and the gurgling of tea brewing in the salty waters of Boston harbour resonated as a bold act of defiance against the British crown. The impact of this act was felt far beyond the shores of Boston. The British authorities reacted harshly, closing Boston Harbour and imposing a series of punitive measures known as the 'Intolerable Laws'. Far from suppressing the rebellious spirit, these measures galvanised the colonies, urging them to unite in defence of their rights and freedoms. In this way, the Boston Tea Party was not just a protest against a tax, but a symbol of resistance, a declaration that the colonists would no longer be passive in the face of what they perceived to be injustices. That night marked a turning point, paving the way for even more direct confrontation and ultimately the quest for American independence.

The British reaction

The series of laws known as the Coercive Acts was London's punitive response to the notorious Boston Tea Party. Passed by the British Parliament in 1774, the Acts were intended to discipline the colony of Massachusetts, and in particular the city of Boston. However, far from calming the situation, they intensified tensions, solidifying the colonies' opposition to British rule.

The Boston Port Act was one of these punitive measures, closing the port of Boston until the damage caused by the Boston Tea Party had been made good. This action had a severe impact on the local economy, leaving many Bostonians unemployed. At the same time, The Massachusetts Government Act restructured colonial government, drastically reducing the powers of the local assembly and giving the British governor greater control. This was seen as a direct attack on the colony's autonomy. In addition, with The Administration of Justice Act, London sought to ensure that British soldiers and officials, if accused of crimes, would not face a biased trial in Massachusetts. This allowed them to be tried elsewhere, often in Great Britain. The strengthening of the Quartering Act was another thorn in the side of the colonists. It stipulated that, if necessary, British soldiers would have to be housed in private dwellings, a heavy imposition on the colony's citizens. Finally, The Quebec Act, although indirectly linked to the Boston troubles, was seen as part of the "Intolerable Acts". It extended the province of Quebec, de facto reducing the size of neighbouring colonies, and promoted Catholicism, which was frowned upon by the Protestant majority in the colonies. In response, the colonies joined forces. The First Continental Congress, which brought delegates from twelve colonies to Philadelphia in September 1774, aimed to develop a coordinated response to these oppressive laws. Instead of intimidating the colonists, the Intolerable Acts acted as a catalyst, laying the foundations for the American War of Independence.

The Intolerable Acts, imposed by the British government, were seen not only as punitive, but also as a direct attack on the colonists' rights and freedoms as British citizens. The closure of the port of Boston, for example, affected the very heart of the colonial economy, while the restructuring of the Massachusetts government undermined their right to self-government, a value held dear by the colonists. The outrage was felt far beyond the borders of Massachusetts. The colonies, which until then had had distinct grievances and regional identities, began to see their destinies as inextricably linked. The injustice felt in Boston was now felt as far away as Virginia or South Carolina. Unity in outrage and resistance became the new norm. This unified opposition became manifest at the First Continental Congress. Bringing together delegates from almost every colony, they engaged in a collective response to perceived tyranny. It was in this context that the Continental Army was formed, with George Washington as Commander-in-Chief. The steady deterioration in relations, exacerbated by coercive acts, eventually brought the colonists to a point of no return. The Declaration of Independence, signed on 4 July 1776, was much more than a political declaration; it was the bold assertion of a people claiming their place and their right to self-determination. So what the British government hoped would be a series of measures that would restore order and authority instead accelerated the colonies' march towards revolution and independence.

Decisive steps towards independence

The British response to the Boston Tea Party, in the form of coercive measures, had unexpected consequences. Instead of isolating and punishing Massachusetts alone, these measures had the opposite effect: they acted as a catalyst to unite the thirteen colonies. While Massachusetts was directly targeted, the other colonies saw it as a dangerous precedent. If Great Britain could violate the rights of one colony with impunity, what was to prevent another colony from suffering the same fate in the future? In this climate of concern, a sense of inter-colonial solidarity emerged. The other colonies sent supplies to support Boston when its port was closed, and committees of correspondence were formed to facilitate communication and coordination between them. Moreover, this sense of shared injustice was amplified by the common recognition of their rights as British citizens. It became clear that, unless they presented a united front, all the colonies would be vulnerable to further incursions on their rights and freedoms. This solidarity laid the foundations for more formal assemblies, such as the First Continental Congress, where the colonies discussed their collective responses to British actions. Gradually, a sense of American nationalism emerged, fusing the distinct identities of the different colonies into a common cause: the quest for autonomy, rights and, ultimately, independence.

In September 1774, a major historic event took place in Philadelphia, heralding the beginning of a new chapter in colonial relations. The First Continental Congress brought together delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies, an unprecedented demonstration of colonial unity in the face of British oppression. During this assembly, a consensus emerged among the delegates: coercive acts, seen as a direct attack on their rights as British citizens, were declared illegal. This was not simply a declaration of disagreement. The colonies were ready for action. They called for the formation of militias, preparing the ground for a possible armed confrontation. This bold gesture was a strong signal to Great Britain that the colonies would not be content with mere verbal protests. The Congress was not just a response to unpopular legislation. It represented a fundamental transformation in the way the colonies perceived themselves and their relationship with the metropolis. For the first time, instead of acting as thirteen separate entities with their own interests and concerns, they had come together as a collective unit to defend their common rights. It was a decisive turning point, a significant step towards independence and the formation of a united nation.

In the tumult of the rise to independence, it is essential to remember that opinion among the American colonists was not monolithic. Indeed, colonial America was a melting pot of diverse perspectives and loyalties. Loyalists, also known as "Tories", were a substantial fraction of the colonial population. These individuals, attached by conviction, tradition or personal interest, remained loyal to the British Crown. Often, they saw resistance and rebellion against the King as ingratitude towards an empire that had provided protection and opportunity. Sometimes it was their economic and social ties with Britain that guided their position, fearing that independence would destabilise their social position or damage their economic interests. On the other hand, there were also colonists who, although opposed to British policies, were reluctant to support an armed revolution. They preferred peaceful means of protest, such as signing petitions or boycotting British goods. For them, the notion of revolution and war often meant economic disruption, the threat of social chaos and the potential for loss of life. This diversity of opinion and approach among the colonists is a reminder that the road to American independence was far from a uniform consensus, but rather a complex mosaic of interests, loyalties and ideologies.

The role of King George III in the escalation of tensions between Britain and the American colonies is often scrutinised and debated. His reign coincided with a period of profound change and upheaval for the British Empire, particularly in North America. Although King George III is often portrayed as obstinate and unable to fully understand the desires and needs of the American colonists, it is crucial to remember that he did not work in a vacuum. Behind him was a British Parliament and advisers who largely shared his belief that the colonies should remain subject to the British Crown and Parliament. The perception among the colonists was that George III was acting tyrannically. His support for coercive acts and the Quartering Act - which forced colonists to house British soldiers - were seen as direct infringements of their rights. Many colonial pamphlets and articles of the time portrayed the King as a distant monarch, indifferent to the concerns of his subjects across the Atlantic. But the real catalyst for discord was not simply the King's personality or actions. It was the deep-rooted feeling among the colonists that they deserved the same rights and privileges as any other British citizen. When these rights were seen to be threatened or ignored, anger and a desire for autonomy grew, culminating in the American Revolution. So while the actions and decisions of King George III undeniably played a part in triggering the Revolution, they were part of a much larger picture of discontent, desires and frustrations that animated the colonies during this crucial period.

The Continental Congress, which met for the first time in 1774, was composed of men who, for the most part, belonged to the socio-economic elite of the colonies. These delegates generally had financial, political or land interests to protect. Although they came from a variety of backgrounds - merchants, lawyers, planters, and a few artisans and businessmen - most were prominent figures in their respective colonies. It is essential to note that the desire for autonomy in the colonies was not only a reaction to the Coercive Acts. Although the Acts played a crucial role in crystallising colonial discontent, friction between the colonies and Britain had been brewing for decades. Concerns about taxation without representation, the ability of the colonies to govern themselves and trade restrictions were among the many sources of anxiety. However, the fact that many delegates to the Continental Congress belonged to the colonial elite had implications for the nature of the American Revolution. These men were not necessarily seeking to establish a radically egalitarian society. Instead, many were concerned with maintaining the existing social order while breaking free from British rule. In other words, while they aspired to political independence, they did not necessarily wish to overturn the socio-economic structure of the colonies. The American Revolution, like all revolutions, was complex, shaped by a multitude of factors and actors. Although the Continental Congress played a decisive role in leading the colonies to independence, it must be seen in the wider context of the tensions, aspirations and anxieties that ran through the colonies during this crucial period.

The colonial elites, who made up the majority of delegates to the Continental Congress, were well aware that a successful revolution would require the support of a large section of the population. To reach the various strata of colonial society, they adopted a multifaceted approach to mobilising support. Taverns, in particular, were vital centres of colonial social life. More than just drinking, they served as meeting places where news, rumours and political ideas were exchanged and debated. Revolutionary leaders used these establishments to spread their ideas, sometimes in the form of songs, toasts or lively discussions. Merchants were also essential, not only as financiers of the cause, but also because they could influence the population through boycotts and other forms of economic resistance against British policies. Lawyers, with their knowledge of British law and Enlightenment philosophy, provided intellectual justification for the revolution, articulating the colonists' grievances in legal and moral terms. Artisans and skilled workers made up a large proportion of the urban population and had an important role to play in mobilising the masses. Their skills were essential to the revolutionary cause, whether by producing goods for the war effort or by actively participating in demonstrations and acts of resistance. Propaganda was also a crucial tool for winning hearts and minds. Pamphlets, often written by eminent thinkers such as Thomas Paine with his famous "Common Sense", played a fundamental role in spreading revolutionary ideas. Newspapers, with their tales of British injustice, amplified anti-British sentiment. By combining these elements, the revolutionary leaders were able to weave a network of support that cut across the different strata of colonial society. This mobilisation was essential to guarantee not only the initial success of the American Revolution, but also its long-term viability in the face of the major challenges it encountered. The American Revolution was not a revolution of the lower classes, but rather a rebellion of the colonial elite, who sought greater power and autonomy from the British government. They succeeded in mobilising the entire population and garnering support for their cause. In the end, however, it was the actions and decisions of this colonial elite that led to the independence of the United States.