« Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (17 versions intermédiaires par le même utilisateur non affichées) | |||

| Ligne 9 : | Ligne 9 : | ||

{{hidden | {{hidden | ||

|[[Introduction to Political Science]] | |[[Introduction to Political Science]] | ||

|[[ | |[[Intellectual legacy of Émile Durkheim and Pierre Bourdieu in social theory]] ● [[The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic]] ● [[Intellectual legacy of Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto in social theory]] ● [[The notion of "concept" in social sciences]] ● [[History of the discipline of political science: theories and concepts]] ● [[Marxism and Structuralism]] ● [[Functionalism and Systemism]] ● [[Interactionism and Constructivism]] ● [[The theories of political anthropology]] ● [[The three I's debate: interests, institutions and ideas]] ● [[Rational choice theory and the analysis of interests in political science]] ● [[An analytical approach to institutions in political science]] ● [[The study of ideas and ideologies in political science]] ● [[Theories of war in political science]] ● [[The War: Concepts and Evolutions]] ● [[The reason of State]] ● [[State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance]] ● [[Theories of violence in political science]] ● [[Welfare State and Biopower]] ● [[Analysis of democratic regimes and democratisation processes]] ● [[Electoral Systems: Mechanisms, Issues and Consequences]] ● [[The system of government in democracies]] ● [[Morphology of contestations]] ● [[Action in Political Theory]] ● [[Introduction to Swiss politics]] ● [[Introduction to political behaviour]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation]] ● [[Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation]] ● [[Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations]] ● [[Introduction to Political Theory]] | ||

|headerstyle=background:#ffffff | |headerstyle=background:#ffffff | ||

|style=text-align:center; | |style=text-align:center; | ||

| Ligne 54 : | Ligne 54 : | ||

Together, these principles have shaped the development of the international system of sovereign states, and continue to influence the way states interact with each other on the international stage. However, as mentioned earlier, these principles are constantly being challenged and adapted in response to new realities and global challenges. | Together, these principles have shaped the development of the international system of sovereign states, and continue to influence the way states interact with each other on the international stage. However, as mentioned earlier, these principles are constantly being challenged and adapted in response to new realities and global challenges. | ||

== | == The "globalisation" of the State system == | ||

How did states come into being? There was the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, but in Europe it took much longer until we really had states and abolished empires. From a global perspective, this process took much longer. | |||

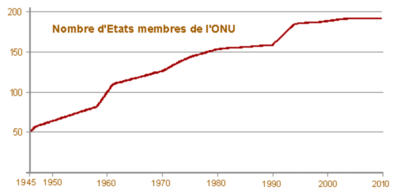

The formation of states as distinct political entities was a long and complex process that took place over several centuries. In Europe, the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 is often cited as a major starting point, as it codified the principles of state sovereignty and non-interference. However, the transition from empires and kingdoms to modern nation states, as we know them today, took much longer. In the European context, this process was facilitated by various factors, such as the emergence of the bourgeoisie, national revolutions, the rise of nationalism and the weakening of feudal structures. It was a gradual process, marked by wars, revolutions and diplomatic negotiations. Ultimately, the concept of the sovereign state became the main model of political organisation in Europe around the 19th century. On a global scale, the formation of states was an even longer and more complex process. In many parts of the world, the concept of the sovereign state was introduced by European colonialism. After decolonisation in the mid-20th century, many new states emerged, often with borders arbitrarily drawn by the former colonial powers. These new states had to navigate a number of challenges to establish their sovereignty and legitimacy, including ethnic and linguistic diversity, economic underdevelopment, and internal and external conflict.[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP globalisation du système étatique 2015.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

The United Nations system was founded in 1945 by 51 countries determined to preserve peace through international cooperation and collective security. The Charter of the United Nations, which is the founding document of the UN, was signed on 26 June 1945 in San Francisco at the end of the United Nations Conference on International Organisation, and came into force on 24 October 1945. These 51 original Member States accepted the obligations of the United Nations Charter and undertook to respect its principles. As such, they laid the foundations for today's organisation, which aims to maintain international peace and security, promote respect for human rights, foster social and economic development, protect the environment and provide humanitarian assistance in times of famine, natural disaster and armed conflict. Since its creation, the UN has grown and evolved to reflect the political and geographical changes in the world. In 2023, the UN will have 193 member states, reflecting the increase in the number of sovereign states since 1945 and the central role of the UN as a forum for international cooperation. | |||

The idea of a state is constantly evolving and the number of states in the world continues to change. The creation of a state is not a fixed and defined process, but rather is shaped by a combination of historical, political, social and cultural factors. In 1945, when the UN was founded, there were 51 member states. However, the number of UN member states has grown considerably since then, to 193 today. In addition, there are entities that have some form of autonomous governance and consider themselves to be states, but are not recognised as such by the international community. These entities, such as Kosovo, Palestine and Taiwan, are often in a complex situation of partial or contested recognition. This reminds us that sovereignty and international recognition are complex political processes that depend not only on the internal structures of a territory, but also on how other states and international organisations perceive and interact with these territories. In short, the existence and recognition of states are constantly evolving and subject to ongoing negotiation. This underlines the complexity and fluidity of the international system, and the fact that statehood is a dynamic and constantly evolving process. | |||

The increase in the number of sovereign states over time can largely be attributed to two major historical processes: decolonisation and the fall of authoritarian regimes and empires. Decolonisation, which mainly took place in the 1960s and 1970s, led to the creation of many new sovereign states in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean. These new states were born of the struggle for independence by colonised peoples against the European colonial powers. Then, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in the 1990s, many other states appeared on the international scene. These events marked the end of the Cold War and reshaped the political and geographical boundaries of Europe and Central Asia. However, this process is not over. There are still regions of the world where statehood is contested or uncertain. Moreover, the very concept of a sovereign state is constantly evolving, in response to political, economic, technological and cultural changes. Consequently, although the international system has evolved considerably since the Treaty of Westphalia, we still live in a world of states in flux, where sovereignty and autonomy are never definitively acquired, but are always the subject of negotiation and conflict. | |||

== Implications of the Westphalian State Model for International Relations == | |||

What does this division of the world into sovereign states represent or imply for international relations? | |||

The division of the world into sovereign states has profound implications for international relations. Essentially, it creates an international system that is often described as anarchic. This is not to say that it is total chaos, but rather that there is no higher global authority that can impose rules or laws on states. Each state has its own internal authority and no state has official authority over another. This means that states are the main players on the international stage. They have the capacity to wage war, conclude treaties, recognise other states and enter into diplomatic relations. In practice, however, their freedom of action is often limited by factors such as economic and military power, alliances and obligations under international law. This also means that international cooperation is often difficult to achieve. In the absence of a global authority, states must voluntarily agree on common rules and standards. This is where international organisations such as the United Nations come in, providing a framework for negotiating and developing these common standards. Finally, this can also lead to conflicts of interest between states, as each state seeks to protect and promote its own interests. These conflicts can be managed through diplomacy, but they can also, in certain circumstances, lead to military conflict. In short, the division of the world into sovereign states creates a complex and dynamic international system, where both cooperation and conflict are possible, and where power and influence are constantly at stake. | |||

In the early phases of the development of international law, the main emphasis was on the coexistence of states and the settlement of disputes through military force, rather than through international legal mechanisms. This included the "law of war" (jus ad bellum and jus in bello), which regulated when a state had the right to declare war and how it should behave during war. In this context, the main aim of international law was to prevent or limit conflict by establishing acceptable standards of behaviour for states. For example, laws governing declarations of war, neutrality and the treatment of prisoners were intended to provide a degree of predictability and stability in an otherwise anarchic international system. | |||

However, the absence of a higher international authority meant that the application of these laws ultimately depended on the will of states and their ability to enforce these norms by force. In other words, the law of the strongest often prevailed. Over time, however, international law has evolved and expanded to encompass a much wider range of issues, including international trade, human rights, the environment, and the law of the sea, among others. In addition, international institutions have been created to facilitate the application of these laws and the resolution of disputes. These developments have contributed to the creation of a more complex and sophisticated international legal order, although many challenges remain in ensuring the effective application of international law. | |||

== The Traditional Structures of the International Order == | |||

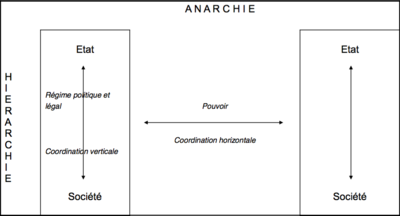

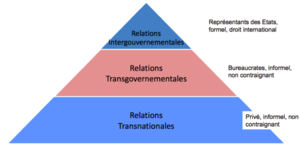

This diagram shows the idea of anarchy at international level. | |||

== | |||

[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP structures classiques de l‘ordre international 2015.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP structures classiques de l‘ordre international 2015.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | ||

The classic structure of international order distinguishes between a hierarchy within states and anarchy between them. | |||

Within a state, a structural hierarchy is clearly observable. The government, acting on behalf of the state, exercises authority over society. This authority is generally accepted by the citizens, in a form of mutual consent or 'shared sovereignty', particularly noticeable in democratic systems. The state, through its control of law enforcement agencies and the military, guarantees respect for the law and maintains order, thus establishing a clear hierarchy over society. | |||

Internationally, however, there is no comparable hierarchical system between states. No state has recognised jurisdiction or authority over another, and no supranational body exercises absolute power over all states. We therefore speak of "anarchy" in the international system. In this context, relations between states are governed by power, negotiation and, in some cases, international law, rather than by a recognised higher authority. | |||

It is within this framework of anarchy that states exercise their external sovereignty, respecting the rule of non-interference and acting autonomously on the international scene. Interactions take place mainly through diplomacy and negotiation, although conflicts and power rivalries can sometimes dominate. | |||

It is important to note that although anarchy describes the absence of a central global authority, it does not mean that the international system is devoid of structure or order. Treaties, conventions, international organisations and other cooperative mechanisms play a crucial role in structuring interactions between states and contribute to the relative stability of the international system. | |||

= The "internationalisation" of the international system = | |||

The "internationalisation" of the international system can be described as the process by which states have become increasingly interconnected and interdependent at the international level. This trend began well before 1945, but accelerated sharply in the post-war period. The formation of the United Nations in 1945 marked a significant turning point in the internationalisation of the international system. With the creation of the UN, states sought to resolve their differences by peaceful means and to collaborate on issues of common interest, thus contributing to greater interconnection and international cooperation. However, it is important to note that the process of internationalisation was not limited to the creation of the UN. It has also been marked by technological advances, the growth of world trade, the emergence of international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and the expansion of global communications. These factors have helped to break down barriers between states and increase their interdependence. | |||

Internationalisation has also been fostered by major events such as decolonisation, which led to the emergence of new states and the redefinition of international power relations. In addition, the evolution of international norms, such as human rights and international humanitarian law, has also helped to shape today's international system. It is therefore essential to understand that internationalisation is a dynamic process, which continues to evolve and shape the international system. Sovereign states, while retaining their autonomy, must now take account of their international obligations and responsibilities, reflecting the increasing interconnectedness and interdependence that characterise the modern international system. | |||

The establishment of today's international system can be attributed to a number of key historical moments. However, one date of particular significance is 1945, with the creation of the United Nations at the end of the Second World War. This moment represents a tipping point where the states of the world, deeply affected by the devastation of two world wars, came together to create an organisation that aimed to prevent such conflict in the future. The adoption of the United Nations Charter by 51 countries, establishing principles of international cooperation, peaceful conflict resolution and respect for human rights, marked the beginning of a new rules-based world order. However, the current international system did not stop there. Many other key moments have shaped its evolution, such as post-war decolonisation, which saw the emergence of many new sovereign states, or the end of the Cold War, which marked a new era of cooperation and conflict between nations. | |||

The year 1945 marked a particularly significant turning point for the international system with the founding of the United Nations. However, an exploration of previous historical events reveals that state sovereignty was already being transformed before this period of modernisation. The transformation of state sovereignty began long before 1945, notably with the development of international trade and the birth of international law. By the 19th century, for example, the expansion of imperialism and colonisation had already created networks of international interdependence. Trade treaties established norms and rules for relations between states, eroding certain aspects of their sovereignty. In addition, the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 marked important preliminary stages in the regulation of international conflicts and the establishment of certain standards of international behaviour. So, although 1945 marks a crucial stage in the structuring of the international system as we know it today, the process of eroding and transforming state sovereignty had already begun long before that date, through the development of international relations and the gradual emergence of an interconnected international community. | |||

# | These processes have accelerated in recent years at three levels. There has been an internationalisation of the international order through : | ||

# | # Globalisation and the spread of liberal values: Global interconnections between societies and populations are becoming increasingly intense. This is mainly due to globalisation, where increased social transactions are leading to an unprecedented level of interdependence. In addition, the spread of liberal values, which encourage the free movement of ideas, goods and people, facilitates and reinforces this process of globalisation. Globalisation is a multifaceted phenomenon that has a profound influence on our contemporary world. It is a process that intensifies the interactions and interdependence between states, societies and populations around the world. On the one hand, this process is fuelled by a significant increase in social transactions. Thanks to technological advances and modern means of communication, individuals, groups and organisations are increasingly in contact with each other. Whether through trade, travel, education, immigration or social networks, people and societies are interacting and interdependent on a scale never seen before. These growing interactions are leading to a convergence of cultures, ideas and lifestyles, making the world smaller and smaller. Globalisation is also facilitated by the spread of liberal values. These values, which include principles such as equality, freedom, human rights, democracy and free-market capitalism, have been widely promoted and adopted throughout the world, particularly since the end of the Cold War. The spread of these liberal values has not only paved the way for greater interconnection and interdependence between societies, but has also created an environment conducive to globalisation. By promoting openness, exchange and cooperation, these values encourage international cooperation and networking across national borders. In this way, globalisation and the spread of liberal values are two interdependent processes which, together, have contributed to greater integration and interdependence between societies throughout the world. | ||

# | # International organisations and institutions: Another aspect of the internationalisation of the international system is the emergence and strengthening of international organisations and institutions through which states cooperate and coordinate their actions. The observation of this phenomenon is not only interesting in terms of the numerical growth of these entities, but also in terms of the qualitative changes that have taken place, particularly since the end of the 20th century. One notable trend is the increasing judicialisation of some of these international organisations. In other words, more and more of these entities have developed legal mechanisms that enable them to exercise supranational legal authority and to issue decisions that are binding on member states. This marks a move away from the traditional principle of state sovereignty in the sense that states are now obliged to respect the decisions of these international organisations, even when they may run counter to their national interests. In parallel with this process of judicialisation, we have also seen a considerable development in regional integration. Examples of regional integration go well beyond Europe and the European Union. We can think of organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), all of which have sought to promote greater cooperation and integration between their member states. | ||

# Transgovernmental and transnational relations: The third level of internationalisation of the international system is found in the emergence of transgovernmental and transnational relations. Trans-governmental relations refer to interactions between different parts of government - bureaucrats, technical specialists and other civil servants - rather than formal relations between governments themselves. For example, those responsible for environmental or financial policy may network with each other, share information and best practice, and so influence national policies. This phenomenon, known as transgovernmentalism, has been particularly marked in recent decades. On the other hand, transnational relations concern interactions between non-governmental actors, such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies and other civil society entities, which are playing an increasingly important role in international politics. These actors can influence international policies and standards, engage in cross-border activities and even negotiate directly with governments and international organisations. In short, the international system is no longer limited to interactions between sovereign states. With the increase in transgovernmental and transnational relations, the boundaries between the internal and external affairs of states are becoming increasingly porous, and a multitude of non-state actors are actively involved in international politics. | |||

These developments bear witness to an ever-changing international landscape, in which the sovereignty of states is both eroded and re-articulated. | |||

== | == The Globalisation of Social Exchanges, Interdependence and the Theory of Liberalism == | ||

There are no simple definitions of the phenomenon of globalisation. Globalisation is a complex and multidimensional concept that cannot easily be summed up in a single definition. However, it can be understood as an increasingly rapid process of integration and interdependence between countries around the world, due to the growth of international trade and capital movements, as well as the rapid diffusion of information and technology. | |||

The definition proposed by Anthony Giddens in Dimensions of Globalization emphasises the growing interconnection of societies around the world.<ref>Giddens, Anthony. "Dimensions of globalization." ''The new social theory reader'' (2001): 245-246.</ref> According to him, globalization is "the intensification of global social relations that link distant localities in such a way that local events are shaped by events occurring miles away and vice versa." | |||

This definition highlights two key aspects of globalisation: | |||

* | * The intensification of global social relations: This refers to the increase in interactions and interconnections between individuals, groups, organisations and states around the world. This can take the form of trade, information flows, migratory movements, etc. | ||

* | * The mutual influence of local and global events: This means that events or decisions taken in one part of the world can have significant effects in other regions, and vice versa. For example, a decision taken by a multinational company in one country may have an impact on the living conditions of people in another. Similarly, local environmental problems can have global repercussions, as is the case with climate change. | ||

Overall, Giddens' definition highlights the interconnected nature of our contemporary world and how events, decisions and processes at different levels (local, national, regional and global) are increasingly interdependent. | |||

Giddens | Giddens conceptualises globalisation as a process whereby an activity carried out in one distant region has an immediate and perceptible impact in another distinct region. The example of climate change is a perfect illustration of how actions taken in one part of the world can have significant impacts elsewhere. Greenhouse gas emissions, whether produced in the North or the South, have global consequences because they contribute to global warming, which affects the planet as a whole. Similarly, conflicts, political or economic crises and natural disasters can trigger migration movements that have repercussions far beyond the borders of the country concerned. For example, a civil war in one country can trigger an influx of refugees into neighbouring countries and even beyond, affecting the stability and resources of these countries. Globalisation has amplified these interdependencies. Because of the increased ease of travel and communication, and growing economic interdependence, local problems can quickly become global. At the same time, global problems increasingly require global solutions, which calls for greater international cooperation. | ||

According to Robert Gilpin, globalisation is the process by which national economies become increasingly integrated and interconnected, leading to a unified world economy.<ref>Gilpin, Robert G.. ''The Challenge of Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century'', Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691186474</nowiki></ref> This means that economic decisions and activities in one country can have significant impacts on those in other countries, even those thousands of miles away. Economic globalisation, as defined by Gilpin, has many facets, including international trade, foreign direct investment, labour migration and the movement of capital. For example, a company based in the United States can have its products manufactured in China, sold in Europe and invest the profits in emerging markets in Africa. This process of global economic integration has been greatly facilitated by technological advances (particularly in telecommunications, transport and information technology), the adoption of liberal economic policies favouring free trade and financial liberalisation, and the rise of international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation. | |||

Globalisation has profoundly changed the way goods and services are produced and distributed. Production chains are increasingly fragmented and spread across different countries, a reality sometimes referred to as 'global value chains'. An example of this phenomenon is the production of a technological product, such as a smartphone. Different components of the phone may be manufactured in different countries around the world. For example, the chips may be produced in Japan, the assembly may be carried out in China, and the design and software development may be carried out in the United States. The finished product is then distributed and sold around the world. At the same time, financial markets have also become increasingly interconnected. Investments can be made almost instantaneously across borders and currencies, and the impact of economic decisions in one country can be felt around the world. This integration of production processes and financial markets has led to greater efficiency and lower costs, but it has also led to greater economic interdependence. This means that economic or financial crises can spread rapidly from one country to another, as we saw during the global financial crisis of 2008. Overall, globalisation has led to greater interconnection and interdependence of the world's economies, with both positive and negative implications. | |||

Jan Aart Scholte, | Jan Aart Scholte, a Dutch international relations scholar, offers a different perspective on globalisation by defining it as ''deterritorialisation'', or the growth of supraterritorial relationships between individuals.<ref>Scholte, Jan Aart. ''Globalization: A critical introduction''. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.</ref> Deterritorialisation refers to the weakening of links between culture, politics, the economy and physical territory. In the context of globalisation, deterritorialisation means that geographical boundaries and distances become less relevant in social, economic and political interactions. For example, in today's digital economy, many transactions and interactions can take place regardless of the physical location of the participants. Individuals and organisations can collaborate on projects, exchange information and ideas, and conduct business together despite significant differences in geographical location. Furthermore, the concept of supra-territorial relationships implies that people, organisations and governments interact and influence each other across national and regional boundaries. International organisations, transnational networks and online communities illustrate these supraterritorial relationships. It is important to note that deterritorialisation does not eliminate the importance of territory and the nation state, but it does complicate and transform these relationships. Thus, from Scholte's perspective, globalisation represents a move towards a more interconnected world that is less rooted in specific territories. | ||

Deterritorialisation refers to the weakening of geographical constraints on social, cultural and economic interactions. With the development of communication technologies, particularly the Internet and social media, interactions and transactions can take place instantaneously and independently of geographical location. This is particularly evident in the digital world, where information and ideas spread across national and regional borders at lightning speed. Social networks such as Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, as well as communication platforms such as Zoom or Teams, allow people to communicate and exchange ideas regardless of their geographical location. This deterritorialisation has profound implications for international relations. It makes it more difficult for states to control information, encourages the sharing of ideas and cultures, and can accelerate social and political change. However, it can also bring challenges, such as the spread of disinformation, the emergence of cyber-attacks, or the exploitation of digital technologies by extremist groups. | |||

David Harvey, | David Harvey, a leading British geographer, sees globalisation as a "time-space compression".<ref>Harvey, David. "Time-space compression and the postmodern." ''Modernity: after modernity'' 4 (1999): 98-118.</ref> This conception refers primarily to the way in which technological advances, particularly in transport and communication, have shortened distances and accelerated interactions between people and places around the world. For example, it takes just one click to send an email to the other side of the world, which would have taken days or even weeks by post a few decades ago. Similarly, advances in air transport have reduced the time needed to travel from one continent to another. This compression of space and time has facilitated and intensified global interactions and exchanges, bringing people and places closer together. It has therefore played a major role in globalisation. However, like deterritorialisation, space-time compression can also pose challenges in terms of international relations, such as the rapid spread of diseases or the management of information on a global scale. | ||

This all-encompassing definition of globalisation is a good illustration of how our world is changing. It highlights the transition from a reality where entities (states and their national societies) were distinct and interacted with a degree of independence, to a world where there is now a shared social space, thanks in large part to technology, international travel and economic interconnection. In this context, issues, challenges and opportunities are no longer solely national, but have an international dimension. For example, environmental, security, economic and even social issues are increasingly addressed in a global context. This calls for greater international cooperation, while raising new challenges in terms of governance, human rights, equity and sustainable development. | |||

== | == An Exploration of Liberalism == | ||

Liberalism has played a central role in promoting and facilitating globalisation. It is a political and economic philosophy that advocates individual freedom, representative democracy, human rights, private property and the market economy. In an international context, liberalism supports interdependence between nations and encourages the free movement of people, goods, services and ideas. This vision is reflected in the promotion of international trade, open borders, support for international organisations, multilateral cooperation and respect for international law. As far as globalisation is concerned, the spread of liberal ideas has facilitated the creation of international institutions, the establishment of global trade rules and the formation of a global culture. This has encouraged connectivity and interdependence between societies around the world. | |||

Free trade is a fundamental principle of economic liberalism that supports the minimisation of trade barriers and government intervention in the international exchange of goods and services. This means that there are no tariffs, quotas, subsidies or government-imposed restrictions on imports or exports. Over the last few decades, this principle has been widely adopted at a global level, thanks in part to international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which promote free trade between countries. This has led to increased economic integration and interdependence between national economies, a phenomenon often associated with globalisation.[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP carte pays membres OMC 2015.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | |||

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) plays a fundamental role in maintaining and expanding the global free trade system. Bringing together almost all the world's states as members or observers, the WTO facilitates trade negotiations, settles trade disputes and works to reduce barriers to international trade. Membership of the WTO implies adherence to the principles of free trade, as well as to a series of rules and standards designed to make international trade more predictable and equitable. This includes reducing or eliminating tariffs and other barriers to trade, ensuring the transparency and predictability of trade regimes, and respecting intellectual property rights, among other obligations. States with observer status are generally in the process of joining the WTO. This status allows them to participate in WTO discussions and meetings, while giving them time to prepare for full membership. These countries generally work to align their trade policies and regulations with WTO standards, with the ultimate aim of becoming full members. That said, while the green card represents the vast majority of the world's states, it is important to note that WTO membership and the practice of free trade are not without challenge or criticism. Some voices question the fairness of the global trading system, suggesting that it favours the richest and most powerful countries, and can exacerbate economic inequalities both between and within countries. | |||

Observer status at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is often a preliminary step towards full membership. Observer countries are generally those that have expressed an interest in joining the WTO and are in the process of aligning their national trade policies with WTO standards and regulations. During this period, they can attend WTO meetings and participate in discussions, but they cannot vote on decisions. It is important to note that the process of joining the WTO can be complex and time-consuming. Applicant countries must negotiate with existing members and demonstrate their commitment to free trade principles and WTO standards. These negotiations can cover a wide range of issues, from tariffs to sanitary and phytosanitary standards and intellectual property rights. In terms of geographical coverage, the WTO is truly a global organisation, with members in almost every region of the world. However, as mentioned earlier, the WTO and the free trade system it promotes are the subject of criticism and debate. Some voices point to the challenges associated with globalisation and free trade, particularly in relation to economic inequality, workers' rights and the environment. | |||

According to the liberal theory of international relations, trade and economic interdependence between nations can contribute to international stability and reduce the risk of conflict. This is sometimes referred to as the "democratic peace theory" or the "peace through trade" hypothesis. The basic idea is that when countries are economically linked to each other, they have a financial interest in maintaining peaceful relations. As a result, the economic cost of war would become prohibitive, discouraging conflict. Furthermore, economic interdependence can encourage international cooperation and the peaceful resolution of disputes. States are more likely to settle their disputes through negotiation and dialogue, rather than force, when they have strong and mutually beneficial trading relationships. | |||

There is also a peace project linked to the idea of opening up economic markets. This notion is often referred to as 'peaceful trade theory' or 'liberal peace theory'. This theory suggests that increasing trade links between nations can reduce the likelihood of conflict because the economic costs of war would be too high. In other words, countries that trade a lot with each other have more to lose in the event of conflict, which would make them less inclined to fight. Proponents of this theory often point out that trade can not only make war more costly, but can also help to build interpersonal and intercultural links, promote mutual understanding and encourage international cooperation. They also stress that trade can contribute to economic prosperity and therefore political stability, which could also reduce the chances of conflict. | |||

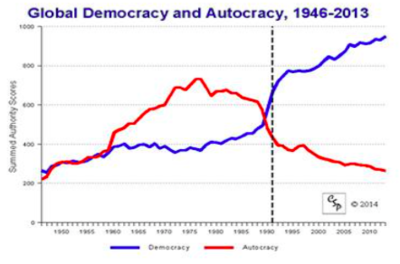

The second transformation, particularly since the 1990s, has been the triumph of democracy. Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, democracy has become increasingly predominant on a global scale. Several factors have contributed to this trend, including the end of the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, which paved the way for major political changes in many countries. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many Eastern European countries adopted democratic forms of government. In Latin America, Africa and Asia, similar transitions took place, with the fall of many authoritarian regimes and their replacement by democratic governments. In many cases, these transitions have been accompanied by economic reforms aimed at opening up economies to global competition. | |||

[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP global autocracy and democracy 1946 to 2013.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP global autocracy and democracy 1946 to 2013.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | ||

The end of the Cold War and the fall of communism in many countries has given rise to a wave of optimism about the potential of democracy and international cooperation. Francis Fukuyama's "End of History" symbolises this era, suggesting that liberal democracy could be the culmination of human socio-political evolution. The increase in the number of democratic states, as illustrated by the blue line, suggests a growing acceptance of democratic principles such as free and fair elections, separation of powers and respect for human rights. At the same time, there has been a decline in the number of authoritarian states, as illustrated by the red line. These developments have certainly created new opportunities for international cooperation, including the sharing of expertise and the joint resolution of global challenges. Democracies, in general, tend to be more open to international cooperation and respect for international norms and rules. | |||

Francis Fukuyama, in his famous book ''The End of History and The Last Man'', argued that the end of the Cold War represented the final triumph of liberal democracy over other political ideologies, notably communism and fascism.<ref>Fukuyama, Francis. ''The end of history and the last man''. Simon and Schuster, 2006.</ref> In his view, this marked the end of humanity's ideological evolution and the ultimate culmination of human progress towards a universally acceptable form of government. Fukuyama envisaged a world where the majority of countries adopted a democratic form of government and respected human rights and free market principles. He also foresaw an increase in international cooperation through supranational organisations, which would contribute to a more stable and prosperous world. | |||

Globalisation and the growing interdependence of states have brought many challenges and counter-movements. These include the rise of nationalism and protectionism, mistrust of international institutions, and social and political polarisation exacerbated by the spread of social networks and false information. At the same time, we are faced with pressing global problems, such as climate change, pandemics, economic inequality and mass migration, which require greater international cooperation. The question is how to balance these contradictory trends and shape a world order that is both equitable and stable. International relations theories can offer us tools for understanding these dynamics. For example, realism emphasises conflicts of interest and the struggle for power between states, while liberalism stresses the importance of international cooperation and global governance. Ultimately, the direction that the global system takes will depend on the political choices and actions of the key players on the international stage. | |||

We have talked about the internationalisation of the international system, globalisation and the spread of liberalism, but we also need to talk about the proliferation of international organisations and the increasing use of the courts. | |||

== The Role of International Organisations, Judiciarisation and Regional Integration == | |||

[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP Prolifération d’organisations intergouvernementales et Non Gouvernementales.png|400px|vignette|Proliferation of intergovernmental organisations (IGOs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).]] | |||

This table is a quantitative summary of the proliferation of international organisations. The data comes from the Union of International Organisations, which provides statistics on these issues. The number of international organisations, both intergovernmental and non-governmental, has increased over time. This is partly due to globalisation and the growing need for international coordination and cooperation on a variety of issues, ranging from economics and trade to the environment, health and human rights. IGOs, such as the UN, WTO, EU, NATO, WHO and others, play a crucial role in facilitating cooperation between states. On the other hand, NGOs, such as Amnesty International, Médecins Sans Frontières, Greenpeace and others, play an important role in championing certain causes and providing expertise and pressure for change on a global scale. The growth of these organisations reflects both the increasing complexity of the international system and the diversity of global issues that need to be addressed. | |||

Perhaps the most exciting aspect is not simply the creation and proliferation of international organisations and NGOs, but rather the real influence that these institutions can exert. The question is whether they emerge as autonomous political forces or whether, in the case of intergovernmental organisations, they simply remain platforms where states negotiate. In the case of NGOs, the question concerns their role: are they entities that raise their voices without having any substantial political impact? The problem then lies in assessing the real influence of these international players. | |||

Measuring the impact of international organisations and NGOs can be done in several ways, and will largely depend on the specific objective of the organisation in question. | |||

* Influencing policies and laws: Some international organisations, such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have a significant impact on the policies and regulations of member countries. Similarly, some NGOs, particularly large international organisations, can influence policy by conducting advocacy campaigns and providing information and research on specific issues. | |||

* Problem-solving and conflict resolution: Organisations such as the UN play a crucial role in conflict resolution and the prevention of humanitarian crises. Their impact can be assessed by examining their ability to resolve or mitigate conflicts and to provide humanitarian assistance when needed. | |||

* Development and humanitarian aid: Many international NGOs are involved in development and humanitarian aid efforts. Their impact can be assessed by looking at progress in the specific areas they target, such as reducing poverty, improving access to education, health, etc. | |||

* Stakeholder engagement: International organisations and NGOs can also have an impact by mobilising the public, raising awareness of the issues they champion, and stimulating dialogue and debate on these issues. | |||

The potentially most significant aspect is not limited to the emergence and expansion of international organisations and NGOs. It also lies in the concrete impact that these institutions can have. The question is whether they become independent political forces or, in the case of intergovernmental organisations, simply serve as platforms for inter-state negotiations. In the case of NGOs, the question is whether they are simply actors who make their voices heard, without really influencing the political landscape. The challenge is therefore to measure the actual impact of these players on the international scene. | |||

The power and impact of international organisations and NGOs at the political level is a subject of debate. On the one hand, some observers believe that these entities exert a substantial influence on global policies, while others maintain that they are merely instruments in the hands of states. In the case of international organisations such as the United Nations or the World Trade Organisation, they are seen by some as autonomous political forces that can shape policy and influence the political decisions of member states. They have the potential to set standards, propose policies and arbitrate disputes between states. However, these organisations are often constrained by their intergovernmental nature, which means that their power ultimately comes from the member states and is often limited by the consensus needed between these states to make decisions. NGOs, meanwhile, are playing an increasing role in global governance, ranging from activism to the provision of essential services to advocacy for specific policies. However, their ability to influence policy is often indirect. They can put pressure on governments and companies, highlight global problems, and sometimes provide solutions, but they generally do not have the power to make binding decisions. | |||

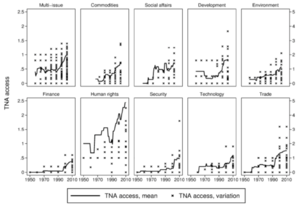

The concept of judicialisation was developed to analyse the influence and power of international organisations. It is based on the idea that law and judicial institutions are playing an increasingly important role in international affairs. This is seen in the emergence of international courts and tribunals, as well as in the increasing use of law and judicial procedures in international negotiations. As far as intergovernmental organisations are concerned, judicialisation can be assessed by examining the extent to which the international norms drawn up by these organisations are binding. In other words, it is a question of measuring the extent to which these standards are respected by the Member States and what the consequences are in the event of non-compliance. For example, consider the decisions of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). If a WTO member state breaches its rules, it can be subject to trade sanctions. This demonstrates a degree of judicialisation, as WTO rules are legally binding and there are tangible consequences for non-compliance. | |||

# | To assess the degree of obligation that international standards impose on States, which are the main addressees of these standards, three distinct aspects can be considered: | ||

# | # The level of obligation: In other words, to what extent are the standards binding on governments? Are they formulated in strong, binding terms, or are they more in the form of recommendations or guidelines? The first aspect, the "level of obligation", concerns the binding nature of these international standards for States. Not all international instruments are explicitly binding. For example, the 1948 United Nations General Assembly Declaration on Human Rights is explicitly non-binding. However, some standards have acquired the status of "jus cogens", i.e. a right that is binding on States, even if they have not ratified the treaty concerned. This is the case, for example, with the norms prohibiting genocide and torture, or the rule of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning a refugee to a territory where his or her life or freedom would be threatened. Despite violations, this does not call into question their legitimacy and validity. Between these two extremes, there are different degrees of obligations linked to international standards. | ||

# | # Proliferation of international standards: This involves determining how many international standards exist in a given area. A proliferation of standards may indicate a high level of international regulation, but it may also mean that the standards are complex and potentially contradictory. The second aspect concerns the "proliferation of international standards" and their degree of judicialisation and precision. This involves assessing whether these standards are sufficiently general to leave states a wide margin of manoeuvre in their implementation, or whether they are so precise that they can be applied as they stand, without the need for transposition at national level. To illustrate this point, let's take the example of the climate negotiations. The Kyoto Protocol imposed no obligations on developing countries, including major emerging powers such as China and India. The United States, although a signatory to the Framework Convention, was not bound by the standards of the Kyoto Protocol. The Protocol's standards were fairly vague, specifying only a level of greenhouse gas emissions for each signatory state, without indicating how this reduction was to be achieved, or setting up monitoring and assessment mechanisms to verify compliance with these obligations. As a result, the framework established by the Kyoto Protocol was rather imprecise and left a great deal of latitude to the States. | ||

# The existence of an enforcement body: In other words, is there an institution or organisation responsible for ensuring that states comply with the standards? This body may also have the power to impose sanctions in the event of non-compliance. The third aspect concerns the application of international standards. In other words, to what extent is there a body responsible for applying and enforcing these standards if states fail to comply with them? On a global scale, there is no international court comparable to a national court. Although the International Court of Justice exists, it can only intervene if the two states involved in a dispute agree to submit to a legal process, otherwise the Court has no jurisdiction. However, in recent years we have seen an increase in the use of more legal dispute resolution processes. For example, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has an elaborate system that also includes sanction mechanisms for states that fail to comply with WTO trade standards. Similarly, the International Criminal Court is another example of a legally strong institution in the field of human rights, capable of condemning individuals for crimes against humanity such as genocide and systematic torture. As far as the climate issue is concerned, the question arises as to what mechanisms will be used to implement the new obligations of States. Will there be a system of reporting between states, where each state documents its measures at international level, and these reports are then evaluated and recommendations made? Or will there be the possibility of sanctions in the event of non-compliance with certain obligations, and if so, by whom? Will it be an independent body that has this authority? Overall, it can be said that over the last twenty years we have seen a trend towards greater judicialisation of international organisations. It's true that many organisations are blocked, like the WTO for example, but this blockage may also be the result of the fact that these organisations have become more restrictive and that states are less inclined to tie their hands. Perhaps states want to retain their flexibility, and this could indicate a move towards a greater role for international organisations. | |||

[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP judiciarisation des RI.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | [[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP judiciarisation des RI.png|400px|vignette|centré]] | ||

In terms of the decision-making process and agenda-setting, it is possible to apply concepts similar to those of the political cycle to international relations. Agenda setting involves determining which members of an organisation have the capacity to propose new standards. For example, within the European Union, the European Commission, which operates independently of the Member States, has this capacity. This is a sign of advanced judicialisation and supranationality, which is not systematically the case in all international organisations. | |||

The second aspect concerns the decision-making process itself. We need to determine whether decisions are taken by consensus, unanimously by States, or by States alone. If this is the case, it can be said that the international organisation produces standards that reflect the individual will of each State. In this sense, these norms are compatible with the concept of State sovereignty, since each State has voluntarily given its agreement to these norms. | |||

Where we have a majority voting system, as is the case within the European Union or the United Nations Security Council, States can be bound by a decision even if they have voted against it. In this way, these international institutions acquire a more supranational character, since they can in fact establish norms that are binding on their members, even in the absence of their explicit agreement. | |||

This raises a series of interesting and important questions about the operation of global governance and the tensions between national sovereignty and international cooperation. For example, is it acceptable for a state to be bound by a decision it has opposed? How can minority states be protected in such a system? This can also lead to conflicts between Member States, especially if the decision taken has major consequences for national interests. At the same time, it is also an effective way of taking decisions and making progress on complex, global issues. | |||

By allowing decisions to be taken by majority rather than unanimity, these institutions can overcome the vetoes of a small number of states and take action on urgent issues. This can be particularly important in situations where inaction or delay could have serious consequences, as in the case of climate change or global security issues. However, it also requires checks and balances to prevent abuse and ensure that the interests of all Member States are taken into account. | |||

The European Union is a good example of this tension. Decisions taken by the European Commission and the European Parliament can have profound effects on Member States, even if they have voted against those decisions. This has led to debates about the sovereignty and power of these institutions, and how Member States can influence decisions taken at this level. The case of the UN Security Council is slightly different, as its five permanent members (the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom and France) have a right of veto over resolutions. This means that these countries can block any decision, even if all the other members agree. This has often been criticised as unfair and representative of a bygone era in world politics. However, it also serves to protect the interests of these major powers and to prevent major conflicts. In short, majority decision-making in international organisations is a key element of international cooperation, but it also raises important questions about sovereignty, representation and fairness. | |||

In the European Union (EU) system, the complexity is compounded by the fact that decision-making does not rest solely with the Member States meeting in the Council of the European Union, but also involves the European Parliament, a co-legislative institution independent of the Council. The European Parliament is directly elected by the citizens of the EU Member States, which strengthens its democratic legitimacy and independence from national governments. This makes the European Union a very unique supranational entity. No other international organisation shares such a governance structure in which citizens have a direct role in supranational decision-making. In this sense, the EU stands out for its ability to transcend national sovereignty in certain policy and legislative measures. | |||

== | == Transgovernmental and Transnational Relations == | ||

The growing interdependence of societies and the emergence of cross-border problems have led to a growing interest in joint solutions. The more globalised societies become, the more problems transcend state borders, requiring more extensive cooperation. Consequently, the creation of international organisations and the development of international standards are essential to meet these shared challenges. These international organisations and standards make it possible not only to regulate cross-border areas of activity, but also to harmonise the policies and practices of different countries. In this way, they contribute to more effective management of global issues, whether climate change, migration, global health or international trade. That said, their effectiveness depends on the willingness of Member States to comply with international standards and to adopt implementing measures at national level. However, the complexity of global issues and the diversity of national contexts make this a difficult task, underlining the importance of the continued engagement of states, international organisations and civil society in addressing these global challenges. | |||

We have seen a trend towards greater judicialisation of international organisations and norms. This judicialisation, i.e. the tendency to resort to law and legal proceedings to resolve international problems, is not uniform across all areas and all organisations. However, the phenomenon is present and notable. Since 1945, we have seen not only an increase in the number of international organisations and multilateral treaties, but also a trend towards making them more binding. The aim is to establish collective discipline and strengthen compliance with commitments made at international level. The application of these standards and agreements can vary, however, depending on countries' adherence to them, their capacity to implement commitments and existing implementation and monitoring mechanisms. Despite the significant challenges, this move towards greater judicialisation is an encouraging sign of the global effort to manage international problems through cooperation and international law. | |||

Another notable phenomenon in the political organisation of states, in addition to their cooperation in intergovernmental organisations, is regional integration. There is a proliferation of regional integration initiatives around the world. For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in North America represents such an initiative. However, this agreement is essentially economic and is limited to the creation of a free trade area, with no greater ambitions, unlike the European Union, which extends to various policies of all kinds. It is important to note that regional integration can vary considerably in terms of ambition and scope. While some agreements may focus primarily on economic issues, others, such as the European Union, may aim for deeper integration covering a wide range of policies and areas of cooperation. | |||

In southern Latin America, we find MERCOSUR, an organisation that brings together Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela and Bolivia. While also a free trade area, MERCOSUR has higher ambitions. Members aspire to a customs union, a common market, and possibly a common currency in the future, although this is not yet the case. MERCOSUR is ambitious; its member countries have developed common policies on the environment, social rights and labour rights for their citizens. The rise of left-wing governments in recent years has led to a shift towards the social sphere. However, with recent political changes, notably in Argentina and Brazil, this focus could change. Nevertheless, MERCOSUR remains a well-established and functional organisation. | |||

The African Union (AU), created at the start of the new millennium in 2002, is also an important regional organisation. Its predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity, focused primarily on decolonisation. The African Union, on the other hand, has much broader ambitions. It relies on sub-regional organisations, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The AU aims for deeper economic and political integration between its member states, inspired in part by the European Union model. A number of sub-regional organisations in Africa share a similar action plan, the main aim of which is to liberalise trade between their member states with a view to creating a common market and eventually a common currency. In some parts of Africa, currency unions already exist, although this is often a legacy of colonial times. The African Union also envisages the unification of these various sub-regional common markets into an Africa-wide common market. However, there have been delays in implementing these plans. Some sub-regional bodies are more effective than others, but it is interesting to note this trend towards regional organisation. The African Union is not only active on the economic front, but also in the field of security. It has a Security Council which, in much the same way as the UN Security Council, can envisage military intervention on the territory of its member states in the event of a crisis, a fairly recent phenomenon. So we are seeing a replication of the UN system at African level, with varying degrees of effectiveness. This major phenomenon goes beyond what the European Union does in terms of security. | |||

In South-East Asia, we also find ASEAN (Association of South-East Asian Nations), a network of states that have come together to create a common market. Although the initial objective was to create this zone by 2015, this is still far from being achieved. However, they have a plan to integrate not only economically, but also culturally and socially. They are developing joint activities, including a system of university exchanges. The concept of cultural and social exchanges is strongly encouraged within ASEAN. | |||

There is also the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), an organisation of Gulf countries which also aspires to establish a monetary union. In addition, the Eurasian Union was more recently launched by Vladimir Putin, bringing together Russia and several former USSR states. This customs union aims to rival the European Union, particularly in the context of the Ukrainian conflict. Russia's ambition is to include Ukraine in this organisation and in this process of economic integration dominated by Russia. This would be incompatible with a deep association agreement with the European Union. It is therefore clear that these regional organisations can also compete with each other. | |||

The phenomenon of regionalism, characterised by the emergence and multiplication of regional organisations, is relatively recent and essentially dates back to the 1990s. It is a response to increasing globalisation and cross-border challenges. Regional organisations provide a framework for states to collaborate and coordinate their efforts to address common and transnational issues, be they economic, political, environmental or security-related. The idea behind regionalism is that countries sharing geographical, historical, cultural or economic links can benefit from closer cooperation. This can take the form of establishing common markets, implementing coordinated policies, or even, in some cases, adopting a single currency. It is important to note that the degree of integration and the nature of the agreements vary considerably from one regional organisation to another. For example, the European Union represents a very high level of integration, with a common currency and supra-national governance in many areas. Other organisations, such as ASEAN or MERCOSUR, are less integrated, but nevertheless pursue objectives of economic and political cooperation. However, despite their growth and potential, regional organisations face many challenges, particularly in terms of coordination between member states, meeting commitments and managing disputes. | |||

Despite the general increase in judicialisation and integration through international organisations, there is a certain weariness with the current multilateral system. Organisations such as the WTO and the UN often find it difficult to advance their agendas because of blockages and conflicts between member states. At the same time, however, we are seeing an increase in cooperation at a more micro level, often referred to as 'network diplomacy' or 'second track diplomacy'. This involves direct interaction and collaboration between technocrats, bureaucracies and administrative departments in different countries. For example, the environment or education ministries of different countries may collaborate directly on specific initiatives, independently of the official positions of their respective governments. These types of collaboration can often be more agile and effective in solving specific problems, due to their more technocratic and less politicised nature. | |||

There is a growing trend towards collaboration between various non-governmental entities, such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), research bodies, businesses and even individuals. These actors work together on common international problems, often in an informal and flexible way, exchanging information, best practice and resources. This type of cooperation, sometimes referred to as "civil society diplomacy", can be a crucial part of the international architecture. These international networks, whether formal or informal, are important because they enable a wider range of actors to participate in solving international problems. They can also provide platforms for information exchange, consensus building and policy implementation at a level that formal intergovernmental organisations may not be able to achieve. It should be stressed, however, that these networks are not a panacea. While they can play an important role in solving international problems, they cannot completely replace the role of states and formal international organisations. These entities have the legal power to take binding decisions, apply rules and adopt sanctions that go beyond what non-governmental networks can do. | |||

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is an excellent example of a transnational organisation that wields considerable influence over the regulation of international finance. Founded in 1974 by the central banks of the G10 countries, the Basel Committee issues recommendations on banking regulation with the aim of improving the stability of the global financial system. It drew up the Basel Accords, a series of recommendations on banking regulation and supervisory standards. Although these standards are not legally binding, they have considerable influence as they are generally adopted by central banks and national regulators around the world. The Basel Committee played a key role in the response to the global financial crisis of 2008. In response, it developed the standards known as Basel III, which tightened banks' capital and liquidity requirements and introduced new regulations to improve bank risk management. However, membership of the Basel Committee has traditionally been limited to central banks in developed countries. This has led to criticism of the representativeness and fairness of the committee, although efforts have been made to include representatives from developing countries, such as China. The example of the Basel Committee illustrates the important role that transnational organisations can play in regulating international issues, but also the challenges they face in terms of representativeness and legitimacy. | |||

These standards are often described as "soft law", which does not have the binding legal force of "hard law". However, although they are not legally binding, these standards can exert strong political and social pressure on states to adopt and implement them. These standards, developed in trans-governmental networks such as the Basel Committee, can become very influential, particularly in areas where international cooperation is essential to solve common problems. For example, in addition to financial regulation, we can also see these kinds of standards in areas such as the environment, public health and labour standards. These informal standards can play a key role in international regulation. For example, they can serve as a basis for the development of more formal international treaties. Furthermore, even in the absence of a formal treaty, these standards can help to create an international consensus on certain issues and guide the behaviour of states. | |||

International cooperation and inter-state relations have evolved well beyond formal diplomatic interaction between states. They now involve a multitude of actors, including non-governmental organisations, multinational companies, international organisations and transnational policy networks. These actors often operate outside formal diplomatic channels, but can nevertheless play an important role in solving global problems and setting the international policy agenda. It is also important to note the impact of information and communication technologies on international cooperation. The Internet and social media have enabled individuals and groups of all sizes and geographical locations to participate in international political discussions. This has led to a partial democratisation of international politics, with ordinary citizens now able to influence international policy decisions. In short, to understand the complexity of international cooperation and interstate relations today, it is crucial to look beyond traditional diplomatic interactions and take into account the multitude of actors and processes that shape the international political world. | |||

The way in which the new emerging powers integrate into the international system is an issue of crucial importance. These countries are not simply passive participants on the international stage, but are increasingly active in setting the global agenda. They do so not only through formal diplomatic channels, but also through informal trans-governmental networks, where they can sometimes find more productive opportunities for cooperation. These trans-governmental relations can be more nuanced and complex than formal diplomatic relations, as they involve a much wider range of actors. They can sometimes be more cordial and productive, as they allow for a more informal and technical form of dialogue. However, they are also often fragmented and dependent on the specific issue or technical area in question. It is essential to understand that states are no longer simply represented by their leaders or foreign ministers on the international stage. Instead, they are increasingly acting through their sub-units, such as specialist ministries, government agencies and even non-state actors. This move towards more decentralised and diversified participation in global governance reflects the growing complexity of the international system and the need for a more multidimensional approach to international cooperation. | |||

Today, the conduct of international affairs goes well beyond formal diplomatic exchanges. Many actors within states - including various government agencies, regulators, local authorities and even parliaments - are actively involved in international affairs. For example, parliaments may participate in international forums, while government agencies may collaborate with their foreign counterparts on specific technical issues. This process of disaggregation reflects the increasing complexity of the modern world. Many of the problems we face today - such as climate change, terrorism or pandemics - cannot be solved by a single state acting alone. On the contrary, they require transnational cooperation and involve a multitude of actors. What's more, this also reflects the growing interdependence of states in our globalised world. Actions taken in one country can have a significant impact on other countries, making international coordination and cooperation necessary. | |||

== | == Evaluating the Influence of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) == | ||

The term "transnational relations" or "transnationalism" refers to the multiplication and intensification of exchanges between non-governmental actors across national borders. These actors may be multinational companies, NGOs, social movements, scientific networks or even individuals. In the context of transnationalism, states are no longer the only players on the international stage. Non-governmental actors are playing a growing role in defining and implementing international policies. For example, NGOs can influence international policies on issues such as human rights or climate change by putting pressure on governments and international organisations, organising awareness-raising campaigns and providing technical expertise. | |||

Transnationalism can also occur alongside traditional inter-state relations. For example, multinational companies may conduct commercial activities across national borders while being governed by international trade agreements negotiated between states. Similarly, NGOs can work internationally while collaborating with governments and international organisations. This means that the conduct of international affairs is increasingly complex and requires an understanding of the interactions between a wide variety of actors at different levels. | |||

The terminology "NGO" (Non-Governmental Organisation) is quite broad and can cover a multitude of organisations with different objectives, structures and working methods. Generally, an NGO is a non-profit organisation that operates independently of government. NGOs can be active in many fields, such as human rights, education, health, sustainable development, etc. The UN has established a number of criteria for accrediting NGOs. These criteria are generally linked to the organisation's mission, objectives and operations. For example, to be recognised by the UN, an NGO must generally : | |||

* | * Have objectives and goals that are consistent with those of the UN | ||

* | * Operate in a transparent and democratic manner | ||

* | * Have an impact on a national or international scale | ||

* | * Have a defined organisational structure | ||

* | * Have transparent sources of funding | ||

Once accredited, an NGO may attend certain UN meetings, present written or oral statements, participate in debates, collaborate with Member States and other actors, and have access to UN information and resources. UN accreditation of an NGO does not necessarily mean that the UN supports or approves of the NGO's actions. It is simply recognition of the NGO's ability to contribute to UN debates and processes.[[Fichier:Lavenex intro SP mesurer influence ONG qui est pas ong.png|400px|vignette|centré|Who isn't an NGO?]] | |||