US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The phrase "under God" was added to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954 during the Cold War, when the US was trying to differentiate itself from the Soviet Union, which was perceived as an atheist state. The change was made by a Congressional decision and was aimed at emphasizing the religious and patriotic values of the US. Until 2003, the Pledge of Allegiance was recited in Texas schools and elsewhere, with the phrase "under God" included.[8] During the Cold War, children in the US, as well as in other countries, participated in civil defense drills that simulated a Soviet nuclear attack. These drills were meant to prepare them for a potential nuclear attack and teach them how to protect themselves from radioactive fallout. This was part of the larger effort by governments to prepare their citizens for the possibility of a nuclear war.

After World War II, the United States emerged as a superpower, with a strong economy and a rapidly growing middle class. This period, sometimes referred to as the "Society of Plenty," was characterized by widespread prosperity and economic growth, as well as advances in technology and consumer culture. The country was able to achieve this level of prosperity due to several factors, including a highly productive workforce, favorable government policies, and a booming consumer market. The US was also able to capitalize on its status as the world's leading industrial power, as well as its dominant position in the global political and military spheres, to maintain and enhance its prosperity during the Cold War era.

The United States and the Cold War

The use of atomic bombs by the United States on Japan marked the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, a period of political and military tension between the US and the Soviet Union. The US believed that its possession of nuclear weapons gave it an advantage over the Soviets in the post-war negotiations, but this action also intensified the arms race between the two nations, leading to a state of global insecurity and fear of nuclear war. This period was characterized by the US' efforts to contain the spread of communism, through military, economic, and political means, and the Soviet Union's efforts to expand its sphere of influence. The Cold War greatly impacted society in the US and around the world, shaping international relations, economics, and domestic policies for decades to come.

At the end of World War II, the United States was in a unique position compared to other major powers. Its territory was largely untouched by the war and its economy was thriving, but the US was unable to force its liberal ideals on the Soviet Union. The US saw the spread of communism as a threat to its way of life and sought to contain its spread through a combination of political, economic, and military means. However, the Soviet Union was not receptive to these efforts, and instead pursued a policy of closed markets and state-controlled economic development. This created significant barriers to the expansion of American economic interests and the US' ability to dominate global markets. The result was a period of intense economic and political competition between the two superpowers, which would come to define the Cold War era.

The Yalta Conference, held in February 1945, was attended by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. The leaders discussed a range of issues related to the post-World War II reorganization of Europe and the future of the Soviet Union. One of the key outcomes of the conference was the establishment of the United Nations (UN), an international organization aimed at promoting peace, security, and cooperation among nations. However, the leaders were unable to resolve many of the economic and political issues that were dividing them. The US and Britain sought to promote free trade and open markets, while the Soviet Union sought to maintain control over its economy and limit Western influence. These differences would lay the foundation for the Cold War and continued to shape international relations for many years to come.

The United States aimed to establish its financial and commercial hegemony over the world through the creation of international financial institutions such as the World Bank, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These institutions were intended to promote economic growth and stability in the aftermath of World War II and to provide a framework for international economic cooperation. However, the USSR saw these institutions as a means for the US to assert its dominance over the global economy and feared that participating in them would undermine its own control over its economy. As a result, the USSR refused to join these institutions, further deepening the divide between the US and the USSR and contributing to the tensions of the Cold War. The refusal of the USSR to participate in these institutions was seen as a rejection of American financial and commercial hegemony and a demonstration of the political and economic differences between the two superpowers.

The fears that fuel the Cold War

The fears that fueled the Cold War were rooted in the differences between the political, economic, and ideological systems of the United States and the Soviet Union. These fears led to a period of intense political, economic, and military competition between the two superpowers, as each sought to assert its dominance and protect its interests. The result was the Cold War, a decades-long struggle for global influence that shaped international relations and defined a generation.

Among the Soviet leaders, there was a fear of encirclement by capitalist powers, which they believed justified their expansion to the West and the establishment of communist regimes in buffer states. These states were created after World War I to prevent the advance of the Soviet Union and were seen as a threat to Soviet security. Soviet leaders feared that these states could be used by the US and its allies to encircle and isolate the Soviet Union, both politically and militarily. As a result, they sought to expand their influence and establish friendly regimes in these states to protect themselves from the perceived threat of encirclement. This fear of encirclement was a major driver of Soviet foreign policy during the Cold War, and contributed to the tense relationship between the Soviet Union and the West.

Among Americans, there was a fear that the USSR represented a global threat to which the US should respond with comprehensive military responses. After World War II, the world was in a period of transition, with many countries, including Europe and Japan, experiencing economic ruin. In some countries, such as Greece and China, there were civil wars, with opposing factions supported by either the US or the Soviets. The British and French colonial empires were facing pressure from national liberation movements, and the stability of the world seemed uncertain. This fear of Soviet expansion and influence, combined with the chaos and instability in many regions, led many Americans to view the USSR as a major threat to US security and interests. As a result, the US pursued a strategy of containment, aimed at limiting Soviet expansion and influence through a combination of military, economic, and diplomatic means. This fear of the USSR and the perceived threat it posed to US security and interests was a major driver of US foreign policy during the Cold War.

U.S. Internal Factors

There were several internal factors in the United States that contributed to the heightened fears of the Soviet threat during the Cold War.

- Truman, Roosevelt's successor, was seen as less capable and experienced than his predecessor, which increased concerns about US preparedness to face the Soviet threat.

- The war industry had made significant profits during World War II, and many in this sector sought to maintain this profit by continuing to produce and sell weapons.

- There was a long tradition of anti-socialist and anti-Bolshevik sentiment in the US, dating back to the 1880s. During the war, there was also strong anti-communist propaganda that contributed to negative views of communism.

- There was a fear that the poverty and instability in many countries after the war would lead to the rise of communist parties in these countries, particularly in France and Italy, and that this would pose a threat to US interests and security.

These internal factors, combined with the external threat posed by the Soviet Union, contributed to a sense of heightened fear and urgency among policy makers and the public in the United States during the Cold War.

The general idea behind the US foreign policy during the Cold War was that the prosperity and well-being of the country was closely tied to its economic growth, which in turn was dependent on access to new markets for exports and supplies of raw materials. The US saw any restrictions or limitations on its plans for global expansion as a threat to its interests, and was therefore motivated to maintain its economic and military power in order to secure its dominance and protect its economic and strategic interests around the world. This idea helped shape the US response to the Soviet Union and its approach to the international order during the Cold War, as the US sought to prevent the spread of communism and maintain its global influence and dominance.

Doctrine Truman

The Truman Doctrine was a foreign policy doctrine announced by President Harry S. Truman on March 12, 1947. The Doctrine stated that the United States would provide political, military, and economic support to any country threatened by communism or totalitarianism, with the goal of containing the spread of communism and promoting the spread of democracy and capitalism. The Truman Doctrine was a response to the growing threat posed by the Soviet Union, which had expanded its sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and was seen as a threat to Western democracy and capitalism. The Doctrine marked a significant shift in US foreign policy, as it marked the beginning of the US's involvement in containing Soviet expansion and maintaining its global dominance during the Cold War.[9][10][11][12]

The Truman Doctrine and the policy of containment formulated by George Kennan are closely related and often seen as complementary. The policy of containment, as articulated by Kennan, sought to prevent the spread of communism and the expansion of Soviet influence by containing Soviet power within its existing borders and limiting its ability to project power beyond those borders. The Truman Doctrine built upon the policy of containment by providing concrete military and economic support to countries threatened by communism or totalitarianism, and thus making it a key component of the US's Cold War strategy. The Truman Doctrine and the policy of containment together helped to shape US foreign policy during the Cold War, as the US sought to maintain its global dominance and protect its interests in the face of perceived threats from the Soviet Union.

The policy of containment during the Cold War can be seen as an extension of the Monroe Doctrine in some ways, although there are also important differences between the two. The Monroe Doctrine, first articulated by President James Monroe in 1823, warned European powers not to interfere in the affairs of the Americas and proclaimed that the Western Hemisphere was closed to further European colonization. The policy of containment during the Cold War similarly sought to protect US interests and prevent the spread of communism, but it was more global in scope and focused on containing Soviet influence rather than European influence.

Like the Monroe Doctrine, the policy of containment during the Cold War reflected a belief in American exceptionalism and a desire to protect US interests and maintain US dominance. However, the policy of containment also reflected the unique geopolitical realities of the Cold War, as the US sought to prevent the spread of Soviet influence and protect its allies in Europe and around the world. Ultimately, the policy of containment was a central component of US foreign policy during the Cold War, shaping US relations with the Soviet Union and shaping global politics for decades to come.[13][14][15][16][17]

The Marshall Plan, also known as the European Recovery Program, was a U.S. initiative launched in 1948 to provide aid to Western European countries to rebuild their economies after the devastation of World War II. The idea behind the plan was to prevent the spread of communism and stabilize the region, as well as to promote the growth of U.S. exports and boost its own economy. Over the course of four years, the United States provided more than $13 billion in aid to Western Europe, which helped the region to recover and become a major trading partner for the United States. The Marshall Plan is considered one of the most successful U.S. foreign policy initiatives of the 20th century and is often cited as a key factor in the success of the post-war economic boom in Europe.[18][19][20][21]

National Security Act

The National Security Act of 1947 was a significant piece of legislation passed by the U.S. Congress during the early years of the Cold War. The act created several new institutions and reorganized existing ones to meet the challenges posed by the Soviet Union. The most significant changes brought about by the act included the creation of the National Security Council (NSC), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Department of Defense. The NSC was tasked with advising the President on national security matters and coordinating the various agencies involved in the country's defense. The CIA was established as an independent intelligence agency responsible for gathering and analyzing foreign intelligence. The Department of Defense was created to coordinate and oversee all military activities, including the newly created U.S. Air Force. The National Security Act of 1947 is considered one of the key pieces of legislation that helped the United States meet the challenges of the Cold War.[22][23]

The CIA was involved in several covert operations in the 1950s and beyond, aimed at overthrowing foreign governments seen as hostile to the interests of the United States. These operations were carried out as part of the larger Cold War effort to contain the spread of communism and promote American interests abroad. Some of the most well-known examples of these operations include the 1953 coup in Iran, the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba in 1961, and the overthrow of Salvador Allende's government in Chile in 1973.[24][25][26][27]

The development of McCarthyism: 1947 - 1962

The anti-communist sentiment in the United States has a long history dating back to the late 19th century. This sentiment was fueled by a mixture of political, economic, and ideological factors, including concerns about the rise of socialist and communist movements, the perceived threat to American business interests, and a strong anti-Bolshevik ideology. Fears and suspicions intensified during the early Cold War period with events such as the Soviet Union's acquisition of atomic weapons, and the perceived spread of communism in Eastern Europe and Asia. Additionally, the fear of espionage and subversion within the US government fueled the creation of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1938, which investigated alleged Communist activities. The committee, along with McCarthy's sensationalized speeches, led to a widespread "Red Scare" and a climate of fear and mistrust in the 1950s. This ultimately resulted in the blacklisting of numerous individuals in the entertainment industry, as well as the firing of federal employees suspected of Communist sympathies. The fear of communist subversion was used by political leaders to justify the pursuit of anti-communist policies both domestically and internationally.

McCarthyism was a period of intense anti-communist suspicion and persecution in the United States during the 1950s, led by Senator Joseph McCarthy. It was characterized by widespread accusations of political subversion and espionage, often without evidence, and resulted in the blacklisting of numerous people in the entertainment and other industries. The term "McCarthyism" has since become a byword for unjust and reckless political persecution.

The term "McCarthyism" is often used as a shorthand for this period and is synonymous with the broader phenomenon of anti-Communist hysteria. Senator Joseph McCarthy led the charge against Communism, often making accusations without evidence and destroying the careers and reputations of many innocent people. The anti-Communist fervor of the time was fueled by fear of Communist infiltration in American society and the perceived threat posed by the Soviet Union.[28][29]

Truman, as President of the United States, was concerned about the growing influence of the Communist Party in America, especially after the Soviet Union became a global superpower after the end of World War II. The strikes, along with the growing membership of the Communist Party of America, contributed to Truman's concern and eventually led him to launch the anti-communist crusade. The post-war period was characterized by economic uncertainty and social unrest, which created an environment ripe for the spread of communist ideology. This, in turn, fueled the fear that communism could take root in the United States, leading Truman to take action to protect American interests. This concern and his belief in the threat of Communist ideology led to a series of actions, including the implementation of the Truman Doctrine and the creation of the National Security Council. [30][31][32]

Truman's concern about the loyalty of federal government employees was a result of the growing influence of communism both domestically and internationally. The Communist victory in China under Mao Tse-tung further fueled his fear and this resulted in the formation of loyalty programs and screening processes for government employees. This atmosphere of suspicion and mistrust also led to the rise of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, which had a lasting impact on American politics and society.

McCarthy's accusations led to a witch hunt and a wave of fear, leading to many people being blacklisted, fired, and even imprisoned based on false or flimsy evidence. The government and private organizations also conducted extensive investigations into people's political beliefs and associations, damaging many careers and personal lives. The period known as McCarthyism resulted in a great loss of civil liberties and a general sense of paranoia that had a lasting impact on American society.

The fear of internal subversion and the threat of communism led to increased government surveillance and repression of perceived dissenters. This included the passage of the Subversive Activities Control Act, which required members of Communist organizations to register with the government, and the creation of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to investigate alleged communist infiltration of the federal government. The actions taken during this period led to widespread censorship, loss of employment and civil liberties for those accused of being communist sympathizers.

Pople who were suspected of being communists or having ties to communism were subjected to intense scrutiny and often faced consequences such as loss of job, exclusion from certain positions, seizure of passport, and even eviction. The government, through the Homeland Security Act, made it illegal for anyone to contribute to the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship and ordered all members of communist organizations to register with the government.

The Korean War lasted from 1950 to 1953 and was a conflict between North Korea (supported by China and the Soviet Union) and South Korea (supported by the United States and other Western countries). Truman's decision to intervene in the conflict was a significant moment in the Cold War, as it marked the first direct military involvement of the United States in a conflict against communist forces. The USSR's absence from the Security Council due to their protest of China's lack of permanent membership allowed for the United States to intervene in the Korean War without facing opposition from the USSR in the Council. The conflict ended in a stalemate, with a ceasefire agreement signed and a demilitarized zone established between North and South Korea.[33][34][35]

The Rosenbergs were arrested in 1950 on charges of conspiracy to commit espionage. They were convicted of passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union and sentenced to death in 1951. Despite protests from supporters who argued their innocence and claimed the evidence against them was circumstantial, they were executed in June of 1953. The case remains controversial and many still question their guilt.[36][37][38][39]

The election of Dwight D. Eisenhower as President of the United States in 1953 marked a shift towards a more conservative, anti-communist foreign policy, and McCarthyism was a significant part of that trend, reflecting a fear and suspicion of leftist ideology and political activism. Richard Nixon, as Vice President, was a key figure in promoting this anti-communist stance, and both he and Eisenhower worked to suppress the influence of the Communist Party in the United States and abroad.

children in the United States was altered to include the phrase "nation under God." Around the same time, the Communist Party was effectively banned in the US following a congressional vote in favor of such a law with 265 members voting in favor and only 2 members voting against.[40][41][42][43] In this climate of anti-communist sentiment, a law was passed in 1954 which made it illegal for anyone to support the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship and required members of Communist organizations to register with the government. This law reinforced the idea that public servants needed to prove their loyalty, and even a mere accusation could lead to loss of job without the need for evidence and without any chance of appeal.

During this time, the legal protections for the accused were not as strong as they are today, and it was relatively easy for someone to lose their job as a federal employee based on accusations alone, without the need for any evidence. This situation reflected the overall climate of fear and suspicion that existed during the Red Scare, and showed the power of the anti-communist sentiment in shaping public opinion and policy.

Senator Joseph McCarthy's anti-communist campaign reached a turning point when he attempted to accuse the U.S. Army of being infiltrated by communists. This move sparked a significant challenge to McCarthy and his methods, as many people began to question the validity of his claims and the methods he used to make them. The Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954 marked the decline of McCarthy's influence and ultimately led to his downfall.

The Soviet Union, in the midst of expanding its power, successfully tested its first hydrogen bomb while also creating the Warsaw Pact in 1955 in response to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) formed by the United States in 1949.[44][45][46][47][48] The launch of the Sputnik satellite, marked a significant moment in the Cold War as it demonstrated the technological advancements of the Soviet Union and heightened fears of a potential missile gap between the US and the Soviet Union. This contributed to increased tensions and heightened the sense of competition and rivalry between the two superpowers. The perceived threat from the USSR and its actions, such as the invasion and the launch of missiles and satellites, reinforced the justification for the Truman policy of loyalty assessments and anti-communist measures in the United States.

The American Society of Plenty

The post-World War II era in the United States, characterized by the Cold War and a sense of prosperity and abundance, marked a significant shift in American society. The threat of Soviet aggression and the arms race fueled a sense of anxiety and government control, but at the same time, there was also an economic boom and widespread growth that created a sense of abundance. This era was also marked by significant social and cultural changes, such as the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of the suburbs.

That is a common pattern in history, where during times of economic hardship or crisis, governments and societies often seek to deflect blame and find an internal enemy to focus the population's frustration and anger on, rather than question the existing power structures or system. This can lead to increased social control, suppression of dissent, and discriminatory policies targeting the identified enemy group. It is a tactic used to maintain stability and divert attention from more systemic problems. However, this can also lead to further social and political division, exacerbating rather than resolving the underlying issues.

Causes and characteristics

The post-World War II economic boom in the United States, also known as the "Golden Age of Capitalism," was characterized by rapid economic growth, low unemployment, and rising living standards.

During the post-World War II era, many Americans were wary of another economic downturn and remained cautious despite the prosperity of the times. Anti-communism was a significant factor in shaping American society during this period, serving as a unifying force that helped to justify American military interventions overseas and to build support for the country's foreign policy objectives. The anti-communist sentiment also helped maintain social stability, providing a clear sense of purpose and direction for American society. Despite this, there was still significant opposition to American military involvement in conflicts abroad, particularly the Vietnam War, and anti-war sentiment grew as the realities of war became more widely understood.

The post-World War II economic boom in the United States was heavily reliant on the construction and automobile industries and the arms industry. The demand for new homes, automobiles, and military equipment helped to drive the American economy during this time and created many new job opportunities. Additionally, the government's role in stimulating the economy through spending and investment in infrastructure projects also contributed to the economic prosperity of the era.

Most Americans, particularly the middle class, benefited from this period of growth and prosperity. With rising wages and a growing economy, many people achieved a higher standard of living and improved economic security. However, it's also important to note that there were still significant economic disparities and issues of poverty and inequality during this time, particularly for minority groups who faced discriminatory practices and limited access to economic opportunity.

The period following World War II saw a significant increase in birth rates, commonly referred to as the "Baby Boom." The Baby Boom was characterized by a sharp increase in the number of births as veterans returned home and started families. A sense of optimism and prosperity encouraged people to have more children. As a result, the US population grew rapidly, with 63.5 million children born between 1945 and 1961. By 1960, the US population had reached nearly 189 million people.

The Baby Boom significantly impacted American society, as it created a large cohort of young people who would come of age during a time of great social and cultural change. It also put pressure on the country's infrastructure and resources as the demand for schools, housing, and other services increased. However, the Baby Boom also created a large and stable consumer market, contributing to the economic prosperity of the post-war era.[51][52]

The post-war Baby Boom was not unique to the United States, as many countries experienced similar increases in birth rates following the end of World War II. However, what sets the US apart is the duration of the Baby Boom, which lasted well into the 1960s. The long-lasting impact of the Baby Boom was reflected in many aspects of American society, including the construction industry. The demand for new homes, schools, and other infrastructure projects increased, leading to the growth of suburban areas with single-family homes, which became the hallmark of the American dream. Additionally, new factories, supermarkets, and airports were built to support the growing population, creating new job opportunities and further boosting the economy. The growth of suburban areas also marked a shift in American society, as people moved away from urban areas and into the suburbs in search of a more idyllic, family-oriented lifestyle. The suburbanization trend continued throughout the post-war era, leading to significant changes in the American landscape and shaping the country's social and cultural landscape in new and profound ways.

The growth of suburban areas and the Baby Boom led to a significant increase in automobile ownership, as people needed a way to get around in these sprawling, car-dependent communities. This, in turn, drove demand for new cars and spurred the growth of the automobile industry.

The automobile became a symbol of the American way of life and the prosperity of the post-war era. The car was seen as a symbol of freedom and mobility, allowing people to travel and explore new areas. Additionally, the growth of the automobile industry also required the development of new transportation networks and infrastructure, such as highways and parking lots, to support the increasing number of cars on the road.

The drive-in movie theatre also became a symbol of the automobile-based society of the post-war era. Drive-in theaters were a popular entertainment destination for families and were often located on the outskirts of cities, accessible only by car. This trend was indicative of the growing popularity of the automobile and the way it was transforming American society.

Military spending in the United States skyrocketed during the Cold War as the country sought to maintain its military advantage over the Soviet Union and other potential adversaries. Between 1949 and 1954, military spending quadrupled, and it continued to rise in the years that followed.

A significant portion of the military budget was dedicated to research and development as the US sought to create increasingly sophisticated weapons systems to maintain its military advantage. This led to a significant increase in investment in science and technology, which had a spillover effect on other industries and contributed to the overall prosperity of the post-war era.

The arms race with the Soviet Union was a major driving force behind the growth in military spending, as both countries sought to develop new and more powerful weapons systems. The competition between the two superpowers was a defining feature of the Cold War and had a major impact on global affairs. The two sides sought to outdo each other in a never-ending weapons development and upgrading cycle.

The US defence industry primarily consists of private corporations relying on federal government contracts for their revenue. This means that the defence industry has a strong financial interest in maintaining high levels of military spending, as it is directly tied to their profits. This interest can sometimes lead the defence industry to promote policies and ideas that increase the perception of insecurity and justify continued investment in the military. The application of the Monroe Doctrine to the world, for example, was often used as a justification for American intervention in foreign countries and as a way to maintain American influence abroad.

It's important to note that this dynamic can sometimes create conflicts of interest and raise questions about the influence of the defence industry on US foreign policy. The relationship between the US government and the defence industry is complex and multifaceted, and it continues to be the subject of debate and discussion in academic and policy circles.

The invention of the transistor in 1947 was a major turning point in the history of technology, as it paved the way for the electronic revolution. The transistor made it possible to miniaturize electronic components and enabled the development of a wide range of new technologies, from the first commercial computers to compact and portable radios.

The electronic revolution led to the automation of many industries, which reduced the need for labor and led to a decrease in industrial employment. This automation trend accompanied a new wave of mergers and acquisitions as large corporations sought to consolidate their power and gain control of the new technologies.

These mergers and acquisitions led to the creation of large conglomerate corporations with financial and technological power. These corporations acquired other subsidiary industries and assembled them into large consortiums, which enabled them to manufacture a wide range of products.

This process of concentration of production had a major impact on the economy and society of the United States, as it led to the rise of a small number of large corporations that dominated the market and exerted significant influence over government policies and the economy as a whole.

The process of concentration of production and the growth of large corporations has been a recurring trend in the history of the American economy. The four waves of concentration have all marked significant periods of industrial capital consolidation and centralisation.

The first wave of concentration occurred at the end of the 19th century when several large corporations emerged and dominated the American economy. The second wave occurred in the 1920s when the growth of the automobile and consumer goods industries led to a new wave of mergers and acquisitions.

The third wave occurred during the New Deal period in the 1930s when the federal government implemented policies to promote economic recovery and growth. This period also saw a new wave of consolidation in many industries as large corporations sought to gain control over new markets and technologies.

Finally, the fourth wave of concentration took place in the post-war period, as the electronic revolution and the growth of the military-industrial complex led to a new wave of mergers and acquisitions. This period was characterized by an unprecedented concentration of industrial capital, as a small number of large corporations dominated the American economy and exerted significant influence over government policies.

The concentration of production and the growth of large corporations significantly impacted the labour movement in the United States during the post-war period. The AFL (American Federation of Labor) and the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) merged into the AFL-CIO in 1955, forming a single, anti-communist trade union movement.

However, despite the consolidation of the labour movement, the number of union members did not increase significantly during this period. The new jobs created during the post-war boom were primarily in the "white collar" sector, such as office and administrative work, and in industries with no strong unionisation tradition.

This shift in the workforce composition and the decline in union membership and influence contributed to the weakening of the labour movement in the United States during this period. Despite these challenges, the AFL-CIO remained a powerful force in American politics, advocating for workers' rights and economic justice.

he post-war period was characterized by a significant increase in agricultural productivity, largely due to technological advances such as mechanization, the use of pesticides and fertilizers, and improved farming techniques. These advances allowed for much larger and more efficient agricultural production, leading to a concentration of agricultural production in the hands of a relatively small number of large agribusinesses.

As a result, many small and medium-sized farms could not compete and were forced to close or sell out to larger operations. This trend was especially pronounced in the United States, where agriculture became increasingly dominated by large corporations and agribusinesses. The consequences of this concentration of production, including the displacement of small farmers and the decline of rural communities, remain important issues to this day.

During the post-war period, agricultural productivity in the United States and other developed countries experienced a rapid increase as advances in technology and farming techniques led to greater efficiency and larger yields. However, as you noted, this increase in productivity was accompanied by a decline in the number of family-run farms, as many could not compete with the larger, more efficient agribusinesses that dominated the industry.

As a result, many rural communities experienced significant changes as farmers left the land searching for other employment opportunities. This trend has had long-lasting effects on rural communities, as declining populations, loss of services and infrastructure, and economic hardship have become persistent challenges. Nevertheless, despite these challenges, many rural communities have managed to adapt and find new opportunities and continue to play an important role in the economic and social fabric of the country.

This migration to northern cities and California for better economic opportunities was known as the "Great Migration". It led to a significant demographic shift in the United States and impacted the country's social, economic, and political landscape. Many African Americans faced discrimination and poverty in the cities. They worked in low-paying jobs, but the migration allowed them to escape the poverty and discrimination of the rural South and pursue better lives for themselves and their families.

Birth of the symbols of America's affluent society

During this time period, America was experiencing significant economic growth and prosperity, leading to the rise of symbols of its affluent society. This included increased consumerism, suburbanization, and the development of new technologies and products. Additionally, there was a focus on individualism and the American dream, which emphasized the idea of success through hard work and the pursuit of material wealth. All of these factors combined to create a cultural shift in America that celebrated its growing prosperity and the values of its affluent society.

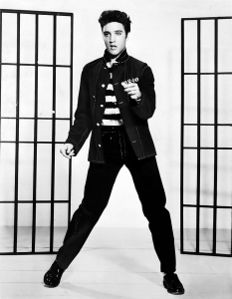

The 1950s marked the beginning of the consumer culture in the United States, where new symbols of American prosperity and consumerism emerged, including television and popular icons like McDonald's, Barbie, Marilyn Monroe, and Elvis Presley. These cultural touchstones came to represent the new affluent society and way of life in the United States. Elvis Presley's music and style in the 1950s caused a stir among the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) community as his sound and movement were heavily influenced by African American culture and were considered controversial by some. He broke the mold of traditional music and dance, which was a departure from the norms of the time.

Additionally, during this time the consumer boom was in full swing and people had more disposable income which led to an increase in consumer goods, automobiles, and suburbanization. The American Dream of owning a home, a car, and leading a comfortable middle-class life became a widespread goal for many people. The 1950s saw the beginning of the baby boom with the post-World War II population increase, and the development of modern technologies such as commercial air travel, air conditioning, and the widespread use of credit cards.

The ¾ of Americans enjoying the affluent society

This migration and growth of industry in the sun-belt lead to an increase in prosperity and the growth of the white middle-class in America. Approximately 3/4 of Americans were able to enjoy this affluent society during the 1950s. The development of industries such as the arms industry, aeronautics, oil extraction, and agribusiness in the sun-belt regions of America contributed to the growth of prosperity and the white middle-class during the 1950s.

During the 1950s, middle-class women were faced with new challenges as they entered the industrial workforce. This change resulted in a conflict between the traditionalist value system and the idea of pursuing salaried work. The integration of women into the workforce was a significant shift that challenged the traditional gender roles and norms.

During the 1950s, the white middle class was the biggest beneficiary of the expanding economy and federal programs. They had access to well-paying jobs in growing industries and were able to enjoy the benefits of the affluent society, while also benefiting from the support provided by federal programs.

The Federal Housing Administration policy led to widespread discrimination and segregation in housing, as the Federal Housing Administration provided mortgages only to white middle-class citizens, excluding marginalized groups such as people of color, the poor, Jews, and other minority communities. This perpetuated a systemic and institutionalized form of discrimination, creating unequal opportunities for different groups in society.[53][54]

The 1950s saw also a huge increase in federal investment in the highway system, with spending growing 38-fold. Despite this investment, public transportation and railways were neglected, and there was no effort to build social housing for the poor until the end of the 1960s. This shift in priorities favored automobile use and reinforced the prosperity of the white middle-class, while neglecting the needs of marginalized communities, particularly the poor.

The ¼ of Americans in Poverty

They are mostly elderly or children, the majority are single women who are widowed or divorced, 70 per cent live in cities and 30 per cent in smaller, more rural communities.

The poorest category is that of Amerindians, whose annual income is half the average income of the poor.[55][56]

In 1953, Congress decided to eliminate Indian reservations. It was the Indian termination policy that removed federal assistance to reserves, encouraging Native Americans to abandon their reserves in exchange for the payment of meager bonuses that swelled the miserable population of the cities.[57][58]

Quand cette politique est stoppée en 1960, de nombreuses tribus ont été décimées.[59][60][61][62]

They are also the urban poor and Puerto Rican immigrants, especially Mexicans, as well as sharecroppers and migrant workers.

Until the early 1960s, the United States did not care about the poor; it was Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson who arrived after Kennedy's assassination and launched the war against poverty which, unfortunately, was to be curbed very dramatically because of the Vietnam War. However, this aid bore fruit, poverty was reduced and 25% of pollution classified as poor fell to 11% in 1973.[63][64][65][66][67][68][69]

Annexes

- “International Monetary Fund.” International Organization, vol. 1, no. 1, 1947, pp. 124–125. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2703527.

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ The phrase "under God" was added to the pledge by a Congressional act approved on June 14, 1954. At that time, President Eisenhower said: "in this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America's heritage and future; in this way, we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country's most powerful resource in peace and war."

- ↑ Full text and audio of the speech

- ↑ Freeland, Richard M. (1970). The Truman Doctrine and the Origins of McCarthyism. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. pp. g. 90.

- ↑ Hinds, Lynn Boyd, and Theodore Otto Windt Jr. The Cold War as Rhetoric: The Beginnings, 1945–1950 (1991) online edition

- ↑ Merrill, Dennis (2006). "The Truman Doctrine: Containing Communism and Modernity". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 36 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00284.x.

- ↑ "Present Status of the Monroe Doctrine". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 54: 1–129. 1914. ISSN 0002-7162. JSTOR i242639. 14 articles by experts

- ↑ Perkins, Dexter (1927). The Monroe Doctrine, 1823–1826. 3 vols.

- ↑ Rossi, Christopher R. (2019) "The Monroe Doctrine and the Standard of Civilization." Whiggish International Law (Brill Nijhoff, 2019) pp. 123-152.

- ↑ Sexton, Jay (2011). The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in 19th-Century America. Hill & Wang. 290 pages; competing and evolving conceptions of the doctrine after 1823

- ↑ Monroe Doctrine and related resources at the Library of Congress

- ↑ Diebold, William (1988). "The Marshall Plan in Retrospect: A Review of Recent Scholarship". Journal of International Affairs. 41 (2): 421–435. JSTOR 24356953.

- ↑ Bryan, Ferald J. "George C. Marshall at Harvard: A Study of the Origins and Construction of the 'Marshall Plan' Speech." Presidential Studies Quarterly (1991): 489-502. Online

- ↑ Mee, Charles L. The Marshall Plan: The Launching of the Pax Americana (1984).

- ↑ Weissman, Alexander D. "Pivotal politics—The Marshall Plan: A turning point in foreign aid and the struggle for democracy." History Teacher 47.1 (2013): 111-129. online

- ↑ Brown, Cody M. The National Security Council: A Legal History of the President's Most Powerful Advisers, Project on National Security Reform (2008).

- ↑ Encyclopedia of American foreign policy, 2nd ed. Vol. 2, New York: Scribner, 2002, National Security Council, 22 April 2009

- ↑ Warner, Michael (June 13, 2013). "CIA Cold War Records: THE CIA UNDER HARRY TRUMAN — Central Intelligence Agency"

- ↑ "Office of the General Counsel: History of the Office". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ↑ "CIA – History". Federation of American Scientists.

- ↑ Warner, Michael (1995). "The Creation of the Central Intelligence Group" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. Center for the Study of Intelligence. 39 (5): 111–120.

- ↑ United States Congress. "Joseph McCarthy (id: M000315)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑ FBI file on Joseph McCarthy

- ↑ Caute, David (1978). The Great Fear: The Anti-Communist Purge Under Truman and Eisenhower. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22682-7.

- ↑ Latham, Earl (ed.). The Meaning of McCarthyism (1965). excerpts from primary and secondary sources

- ↑ Schrecker, Ellen (1994). The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-08349-1.

- ↑ Luuk van Middelaar, Le passage à l'Europe, Paris, Galimard, 2012, 479 p. (ISBN 978-2-07-013033-7)

- ↑ « Le compromis de Luxembourg », sur cvce.eu

- ↑ Matthias Schönwald: Walter Hallstein and the „Empty chair“ Crisis 1965/66. In: Wilfried Loth (Hrsg.): Crises and compromises. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2001, ISBN 3-7890-6980-9, S. 157–172.

- ↑ Alman, Emily A. and David. Exoneration: The Trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell – Prosecutorial deceptions, suborned perjuries, anti-Semitism, and precedent for today's unconstitutional trials. Green Elms Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9779058-3-6 or ISBN 0-9779058-3-7.

- ↑ Carmichael, Virginia .Framing history: the Rosenberg story and the Cold War, (University of Minnesota Press, 1993).

- ↑ "David Greenglass grand jury testimony transcript" (PDF). National Security Archive, Gelman Library, George Washington University. August 7, 1950.

- ↑ Wexley, John. The Judgment of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Ballantine Books, 1977. ISBN 0-345-24869-4.

- ↑ Communist Control Act of 1954, August 24, 1954, An Act to outlaw the Communist Party, to prohibit members of Communist organizations from serving in certain representative capacities, and for other purposes.

- ↑ McAuliffe, Mary S. “Liberals and the Communist Control Act of 1954.” The Journal of American History. 63.2. (1976): 351-67.

- ↑ Haerle, Paul R. “Constitutional Law: Federal Anti-Subversive Legislation: The Communist Control act of 1954.” Michigan Law Review. 53.8 (1955): 1153–65.

- ↑ “The Communist Control Act of 1954.” The Yale Law Journal. 64.5 (1955): 712-65.

- ↑ "Text of Warsaw Pact" (PDF). United Nations Treaty Collection. Archived (PDF) from the original

- ↑ Yost, David S. (1998). NATO Transformed: The Alliance's New Roles in International Security. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-878379-81-X.

- ↑ Formation of Nato and Warsaw Pact. History Channel. Archived from the original.

- ↑ "The Warsaw Pact is formed". History Channel. Archived from the original.

- ↑ "In reaction to West Germany's NATO accession, the Soviet Union and its Eastern European client states formed the Warsaw Pact in 1955." Citation from: NATO website. "A short history of NATO". nato.int. Archived from the original.

- ↑ CDC Bottom of this page http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/vsus.htm "Vital Statistics of the United States, 2003, Volume I, Natality", Table 1-1 "Live births, birth rates, and fertility rates, by race: United States, 1909-2003."

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau — Oldest Boomers Turn 60 (2006)August 2010

- ↑ Van Bavel, Jan; Reher, David S. (2013). "The Baby Boom and Its Causes: What We Know and What We Need to Know". Population and Development Review. 39 (2): 264–265. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00591.x.

- ↑ Figures in Landon Y. Jones, "Swinging 60s?" in Smithsonian Magazine, January 2006, pp 102–107.

- ↑ Principles to Guide Housing Policy at the Beginning of the Millennium, Michael Schill & Susan Wachter, Cityscape

- ↑ "Racial" Provisions of FHA Underwriting Manual, 1938 Recommended restrictions should include provision for the following: Prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended … Schools should be appropriate to the needs of the new community and they should not be attended in large numbers by inharmonious racial groups.

- ↑ Getches, David H.; Wilkinson, Charles F.; Williams, Robert L. (2005). Cases and Materials on Federal Indian Law. St. Paul, MN: Thomson/West. pp. 199–216. ISBN 978-0-314-14422-5.

- ↑ Wunder, John R. (1999). Native American Sovereignty. Taylor & Francis. pp. 248–249. ISBN 9780815336297. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ↑ House concurrent resolution 108 (HCR-108), passed August 1, 1953, declared it to be the sense of Congress that it should be policy of the United States to abolish federal supervision over American Indian tribes as soon as possible and to subject the Indians to the same laws, privileges, and responsibilities as other US citizens - US Statutes at Large 67:B132

- ↑ "Public Law 280" . The Tribal Court Clearinghouse. 1953-08-15. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Fixico, Donald Lee (1986). Termination and Relocation: Federal Indian Policy, 1945-1960. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0908-2.

- ↑ raska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3723-0. Ulrich, Roberta (2010). American Indian Nations from Termination to Restoration, 1953-2006. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3364-5.

- ↑ "Federal Indian Policies". Oneida Indian Nation. Archived from the original

- ↑ "List of Federal and State Recognized Tribes".

- ↑ Woods, Randall (2006). LBJ: Architect of American Ambition. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0684834580.

- ↑ Zarefsky, David. President Johnson's War on Poverty (1986).

- ↑ Califano Jr., Joseph A. (October 1999). "What Was Really Great About The Great Society: The truth behind the conservative myths". Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Zachary A. Goldfarb (December 9, 2013). Study: U.S. poverty rate decreased over past half-century thanks to safety-net programs. The Washington Post.

- ↑ Bookbinder, Hyman (August 20, 1989). "Did the War on Poverty Fail?". The New York Times.

- ↑ Martha J. Bailey and Sheldon Danziger (eds.), Legacies of the War on Poverty. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2013. ISBN 9780871540072.

- ↑ Annelise Orleck and Lisa Gayle Hazirjian (eds.), The War on Poverty: A New Grassroots History, 1964–1980. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011. ISBN 9780820339498.