The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The United States Constitution, which was adopted in 1787, lays out the framework for the federal government and its powers. It also includes a Bill of Rights, which outlines individual rights and freedoms. The Constitution has been amended 27 times throughout history, and it is still in force today. The course focuses on understanding the development of the Constitution and the tensions it generated leading up to the Civil War, which was fought from 1861 to 1865. The course also examines the changes in politics, religion, and society that led to the formation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. This doctrine established the principle that the United States would consider any attempt by European nations to colonize or interfere with the nations of the Americas as a threat to its own security. By studying the United States around 1800, one can gain insight into the country's political and social history and how it continues to shape the nation today.

The Articles of Confederation and the Constitutions of the various States

Shortly after independence in 1776, the States of the Union signed the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation were adopted by the thirteen original states of the United States in 1777 and served as the country's first constitution. They were written as a reaction to the centralized authority of the British government, which the colonies had just fought to gain independence from. The Articles of Confederation established a weak central government with most of the powers remaining with the individual states. The central government could not raise taxes, regulate commerce, or enforce laws effectively, which led to numerous problems and challenges for the young nation. As a result, many leaders began to call for a stronger central government, which ultimately led to the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787.

After achieving independence from Britain, each of the 13 original states plus Vermont adopted its own constitution. These state constitutions reflected the diverse political and cultural beliefs of the people within each state and set out the structure and powers of the state government. However, as the nation began to face challenges such as economic instability and threats to national security, many leaders recognized the need for a stronger and more unified government. This led to the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787, which established a federal system of government with a clear division of powers between the national government and the state governments. The preamble to the Constitution lays out the reasons for its creation, emphasizing the goal of forming a more perfect union and securing the benefits of liberty for all citizens.

During the early years of the United States, each state had its own constitution and system of government, which reflected the different political and social beliefs of the people within each state. Some states, like Pennsylvania, had relatively egalitarian government systems, with universal suffrage for white men who paid taxes and a single assembly with a collegial executive. Other states, like Maryland, had more hierarchical systems of government, with an assembly and a senate and concentrated executive power in the hands of a governor who was elected by the wealthy landowners, who also had the right to vote. New Jersey also had limited suffrage, where the right to vote was restricted to those who met certain property ownership requirements, including women who have been rich for a long time. These differences in state government were one of the factors that led to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, which aimed to establish a more unified and effective national government to address the challenges facing the young nation.

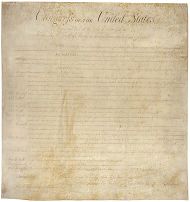

The diversity in state government and political beliefs during the early years of the United States was a significant factor that led to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution aimed to establish a more unified and effective national government to address the challenges facing the young nation. The Bill of Rights, the first of ten amendments to the Constitution, were adopted in 1791 and were added to protect the individual rights of citizens from the potential abuse of power by the government. The Bill of Rights guarantees the equality of men and protects individual rights such as freedom of speech, religion, and peaceful assembly. The Bill of Rights also protects property rights, due process and a fair trial.

The Bill of rights did not protect the rights of all citizens at the time, as it did not include rights for enslaved people and Native Americans, and rights for women were also limited. As a result, it took many years and many struggles for these groups to gain their rights.

At the time of the drafting of the U.S. Constitution in 1787, slavery existed in all of the 13 original states. Still, the institution of slavery was not treated equally in every state. Some states, like Vermont, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, had abolished slavery shortly after gaining independence from Britain. Other states, such as Pennsylvania and New York, passed gradual abolition laws that slowly phased out slavery over time. However, in states such as South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, slavery was deeply ingrained in their economies and society, and the institution of slavery was not abolished.

Furthermore, in all states except South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, there was no legal exclusion of Black people from voting or participating in politics. However, in practice, many barriers to voting and political participation were imposed by law and custom, which effectively denied many Black people the right to vote.

Throughout the South, slavery hardened after independence, and the number of slaves increased through imports and natural growth. This led to a growing divide between the North and South over the issue of slavery, which ultimately led to the Civil War.

The Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865, was fought primarily over the issue of slavery and states' rights, and the tensions between the North and South came to a head. The war resulted in the abolition of slavery and the destruction of the slave-based economy in the South. After the war, the United States faced significant challenges in rebuilding the country and addressing the social and economic issues that had led to the conflict.

During this time, the U.S. government, under the leadership of President Andrew Johnson, attempted to implement a plan of Reconstruction that focused on restoring the southern states to the Union as quickly as possible and with minimal disruption to the social and economic order. However, this plan faced significant opposition from Congress and many citizens, who believed that more radical measures were needed to ensure the rights of newly freed slaves and promote economic and social equality.

As a result, the U.S. government implemented a new constitutional amendment, the 13th, 14th and 15th amendment, which abolished slavery, granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, regardless of race, and gave voting rights to the African American men. These amendments were a part of a stronger, more centralized government and aimed to address the issues that led to the Civil War, and to ensure a more perfect Union.

The Philadelphia Constitutional Convention

The Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, which was held in 1787, was attended by 55 men, mostly lawyers and politicians, who were tasked with drafting a new constitution for the United States. Among them, 19 were large enslavers. During the convention, there were significant debates and disagreements over several key issues, including the structure of the government and the question of who would be able to vote.

One of the main debates centred around whether the right to vote should be limited to landowners or whether it should be considered a natural right of every free man. This debate was complicated because the Declaration of Independence had stated that "all men are created equal," but whether this included enslaved people and non-landowners remained unresolved.

Another important issue that was debated was slavery and the status of free slaves. The Southern states argued for the protection of their institution of slavery and the continuation of the transatlantic slave trade. In contrast, the Northern states opposed the expansion of slavery and sought to limit or abolish it. These debates ultimately led to the inclusion of the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted each enslaved person as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of apportioning representation in the U.S. House of Representatives, and the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required the return of runaway slaves to their owners. These compromises helped to resolve some of the tensions and enabled the drafting of the Constitution, but also set the stage for further conflicts over slavery in the future.

Silences, concessions and achievements of the Constitution of 1787

The U.S. Constitution is a document that has been able to endure for more than 200 years because it is a compromise between different groups of people with different ideas and interests. The language used in the Constitution is often vague and open to interpretation, which allows for different interpretations and applications over time. This flexibility has helped the Constitution adapt to changing circumstances and remain relevant throughout the country's history.

The Constitution's opening phrase "We the People" was intended to emphasize the idea that the document was created by and for the people of the United States. However, the Constitution does not clearly define who is considered part of "the people." This lack of definition was a deliberate compromise made by the framers to avoid potential conflicts over who should be included in the new government. Additionally, the Constitution does not mention slavery directly. Instead, it uses language that allows for the continuation of the practice, such as the three-fifths compromise, which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person to determine representation in Congress. The framers made this compromise to secure the support of southern states that relied on slavery for their economy.

The U.S. Constitution is a federal document, which means that it outlines the structure and powers of the national government, but it also leaves many powers to the individual states. Each state has its own constitution, which outlines the structure and powers of the state government. Additionally, each state has the power to define its own citizenship requirements. This means that the qualifications and rights of a citizen can vary from state to state. This system is known as federalism, which divides the power between the national government and the state government. This allows the states to have some autonomy while still being part of the larger federal union.

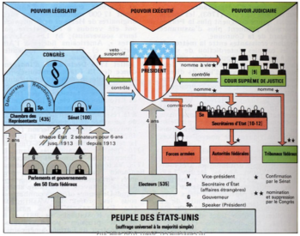

The Constitution establishes a system of separation of powers, dividing the government into three branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial. The legislative branch, which makes the laws, is composed of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention decided that the Senate would be composed of two senators per state, giving each state equal representation regardless of population. In contrast, the House of Representatives is based on population, with each state receiving a number of representatives proportional to its population. This representation system was intended to balance the interests of smaller states with those of larger states, and to ensure that the government would be responsive to the needs of the people. The separation of powers also helps to prevent any one branch from becoming too powerful, and allows for checks and balances between the branches.

In 1787, during the drafting of the Constitution, the delegates from the northern states made a significant concession to the slaveholding states, accepting the so-called "Three-fifths Compromise." This compromise stipulated that for the purpose of determining representation in Congress, enslaved people would be counted as three-fifths of a person. This meant that the number of representatives from the slaveholding states would be based on the number of free inhabitants, plus three-fifths of the slave population of their state. This compromise allowed the southern states to increase their representation in Congress and maintain a balance of power with the northern states. However, it also meant that the Constitution treated enslaved people as less than full human beings, and this compromise has been widely criticized as a moral failing of the Constitution.

During the drafting of the Constitution, there was significant debate over the role and powers of the executive branch, specifically the President. Some delegates wanted a strong President, with powers similar to that of a constitutional monarchy, while others opposed anything resembling a monarchy. As a compromise, the Constitution created a President with veto power over legislation passed by Congress, and a Vice President who is not directly elected by the people but chosen by an electoral college of electors. This system was intended to balance the need for a strong executive leader with the desire to avoid a monarchy-like figure. The President would have the ability to veto legislation and act as a check on the power of the legislative branch, but the Vice President would not be elected directly by the people, and would serve as a tie-breaker in the event that the electoral college was unable to reach a decision.

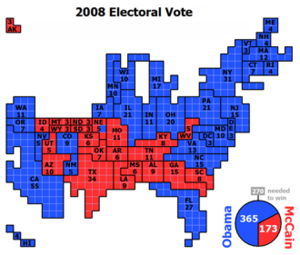

The electoral college is a system established by the Constitution in which each state has a number of electors equal to the number of its representatives in the House of Representatives plus two for its Senators. These electors then cast votes for the President and Vice President. The candidate who receives a majority of electoral votes, at least 270 out of 538, becomes the President. The rules for the electoral college have been amended over the years, mostly in the form of the 12th and 23rd amendment. The 12th amendment, ratified in 1804, changes the way the president and vice president are elected. Instead of voting for two candidates without specifying which is for president and which is for vice president, electors must now vote for one candidate for president and another for vice president. The 23rd amendment ratified in 1961, gives the residents of the District of Columbia the right to vote in presidential elections.

On Presidential Election Day, voters in each state elect a group of electors, known as the Electoral College, who will then cast votes for the President and Vice President. Today, most states use a "winner-takes-all" method, where the political party that wins the majority of votes in the state wins all of that state's electoral votes. This system creates an incentive for candidates to focus on states where they have a good chance of winning a majority of votes, and explains why the majority of campaign events and advertising take place in states with large populations, like Florida.

It's worth mentioning that Maine and Nebraska are the two states that use a different method, the "congressional district method", where two electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the state's popular vote, and the remaining electoral votes are awarded to the winner of each congressional district.

This system has been criticized because it can result in a situation where a candidate wins the popular vote but loses the election because of the way electoral votes are allocated. This has happened multiple times in U.S history, most recently in 2000.

In the United States, citizens do not directly elect the President through a system of universal suffrage, where every citizen has an equal vote. Instead, the President is elected through the Electoral College system, where each state is allocated a certain number of electors based on its population. These electors then cast their votes for the President. It is possible for a candidate to win the election without receiving a majority of the popular vote. This can happen if a candidate wins a majority of the electoral votes, which are allocated to states based on population, even if they do not win the popular vote. This has happened in several U.S. presidential elections, most recently in 2016. This system has been criticized for being undemocratic, as it can result in a candidate winning the election without having the support of a majority of the citizens.

In 1787, the delegates agreed to create a strong judiciary that controls Congress and can declare certain decisions unconstitutional. It is an established supreme court made up of 6 judges (now 9) appointed by the president, but elected by parliament and appointed for life. The Supreme Court is the citizens' last resort in all matters relating to constitutional law.

During this convention of 1787, the northern delegates made further concessions to the slave-owning southern states showing the racial limits of the concept of equality.

The northern states approved a clause that forced states that had already abolished slavery to return fugitive slaves from the south to the southern states. The other concession was that the northern delegates agreed to postpone the ban on importing new slaves from Africa for 20 years, i.e. until 1808. This will lead to massive imports of Africans until 1800.

At the same time, the slave trade within the United States continued until the abolition of slavery in 1865.

Much more than the compromise, it is the reduction of prerogatives in relation to the central federal state that will cause the most tension. It was the idea that the federal state could levy taxes on the whole territory, the other and the fear of the small states of losing their freedoms in relation to the large states.

It will be some time before the convention is adopted. It was only three years later, in 1790, that the most reluctant states finally signed the Constitution, but before that, amendments had to be attached to the constitution.

Bill of Rights

These amendments form the Bill of Rights[11] that protect fundamental freedoms:

- religion;

- expression;

- press;

- peaceful assembly;

- petition;

- weaponry for state defense militias; *

- protection against abuses by the state, police and justice.

The Bill of Rights is preceded by very little of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in France. However, the Bill of Rights is much more concerned with the common good and very individualistic. There are also rights that protect individuals against arbitrary action by the state.

One amendment that continues to attract a lot of ink is the freedom to bear arms: "Since a well-organized militia is necessary for security, the right of the people to keep and bear arms must not be restricted. This shows how malleable this is.

One clause limits the rights of the federal state to those contained in the Constitution. On the other hand, it must be seen that it contains fundamental freedoms that are totally incompatible with slavery; its adoption without calling slavery into question tacitly confirms the exclusion of blacks and women.

Society at the beginning of the 19th century

Territorial expansion

The United States of 1800 will expand rapidly. The Lewis and Clark Expedition crosses territories then in Indian hands[12][13][14][15][16][17]

"Lewis and Clark on the Columbia River", painted by Charles Marion Russell.

An event that will double the territory and the purchase of Louisiana from Napoleon's France. Louisiana had been returned by Spain to France, but was finally bought for 15 million dollars from Napoleon to finance the war in Haiti[18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. It is a territory where there are posts, but mostly Amerindian populations. The United States acquired Florida in 1818 without compensating Spain. Suddenly, the territory doubles.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33].

Bipartism

Very quickly, the oppositions that emerged during the constitutional debates were between two main parties, namely :

- the federalists with George Washington who were in favor of a strong federal government and good relations with Britain, opposed to the French Revolution. It's a very strong party among merchants, owners, craftsmen linked to trade and supported mainly in the north.

- The Republican-Democrats: they are in favour of a limited central government, close in some ways to the French Revolution, because they are not in favour of racial equality, opposed to Great Britain. They are strong among planters in the south and farmers in the north.

Already in 1800, there is an election campaign in the United States with the Republican-Democrats accusing the federalists of being monarchical and sold out to Britain, while the federalists accuse the Republican-Democrats of being Jacobin, anarchist and sans-culotte.

Religion

A "great awakening" took place throughout the Louisiana region and with the advance of the border at the expense of the Indians. More militant and evangelical Protestantism will make the revival to the sound of sermons with preachers who mobilize thousands of faithful in meeting camps.[34][35][36][37][38].

Women's participation is important for women's entry into politics.

In Kentucky, a camp brought together 20,000 people. The other important thing is the development of religious sects is a phenomenon that can be understood with the evolution of the border. For the new migrants, in each new conquered territory there will be religiosity in order to create a link between the different migrants.

This "great awakening" affects women, but especially black people. First of all, it is the free blacks who will form the first black church with the African Evangelical Apostolic Church in response to the racism that is beginning to develop in the white churches.

The "great awakening" affects the forcibly displaced slaves, because it is with the slaves and with the whip that these new territories will be conquered.

Around 1810, 100,000 slaves were forcibly displaced to the West. Slavery spread and hardened. In 1770, there were 450,000 slaves in the 13 colonies; by 1820, there were 1.5 million.

Among the slaves there is a parallel with the enslaved Jewish people in Egypt. In this movement, black preachers emerge.

Religion played a covering role for the women, but also for the slaves, allowing them to carve out a place in society through religion.

Growth of slavery

Since the purchase of Louisiana in 1803, the issue of slavery and the balance between slave and non-slave states has been growing.

Since 1800, 20 new states have joined the Union. Of the 22 states that made up the Union in 1819, there is a precarious balance between slave and non-slave states.

In 1819, Missouri applied to join the Union as a slave state. A long debate ensues in Congress, because the big question is the Senate. If you have a large majority of slave states, that means that the majority of senators are slave states, which means that slavery could be forced into the non-slave states. This will lead to the Civil War.

After a year of debate, the "Missouri Compromise" was reached with the creation of a free state to have 12 slave and 12 non-slave states[39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51].

The beginning of American nationalism

The revival of nationalism

It is a nationalism that was to be revived in 1812 when the United States launched a new war against England to expand its northern borders[52][53][54][55]. The idea is to push the English back north, but it was a failure.

In addition, the United States had no navy, and Great Britain was imposing a blockade on the seas and coasts of the United States, which would have the effect of strengthening nationalism.

The United States did not gain a square metre, but the big losers were the defeated Indian nations who opened up all the territories south of the Great Lakes to the new white settlers. All this still very Indian part will see massacres and exodus.

The consequence of this war is an upsurge in nationalism and self-confidence. Artists began to represent the myth of an agrarian society. The English embargo allows the first development of factories mainly on the east coast of the United States competing with the English.

It is also a time when we realize that in order to control the territory we have to build roads and canals which is very important to develop the colonization of the territory.

On the other hand, the rulers were interested in education and public health, which led to the development of infrastructures. It is also the birth of an American architecture, but which in fact imitates the Greco-Roman style. Thomas Jefferson will go so far as to design his own house inspired by ancient constructions.

Nationalism also translates into the strengthening of the army with the creation of the United States Military Academy of West Point.

The Monroe Doctrine

This doctrine marks the beginning of the imperialist vision of the United States[56][57][58][59][60]. Its context is the victory of the Haitian revolution, the independence of Brazil and the Spanish colonies from Mexico to the very bottom of South America. This will stir up the lust of Great Britain. It is a unilateral declaration by the government of the United States under President Adams, which is against any interference from Europe in the Americas, which were already largely independent in 1823.

This doctrine includes the demand for non-colonisation by European powers in the western hemisphere, particularly with regard to Alaska, and the non-intervention of European powers in the affairs of the American continent.

- non-interference by the United States in the affairs of Europe, including the European colonies. At the time, this doctrine went virtually unnoticed, because the great power of the day was Great Britain, which was respected in the Americas by its Royal Navy.

The Monroe Doctrine marks the beginning of American ambitions for the Americas and then for the world that will take shape over the decades.

Annexes

- La doctrine de Monroe, un impérialisme masqué par François-Georges Dreyfus, Professeur émérite de l'université Paris Sorbonne-Paris IV.

- La doctrine Monroe de 1823

- Nova Atlantis in Bibliotheca Augustana (Latin version of New Atlantis)

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1998). The Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. Random House.

- Berkin, Carol (2015). The Bill of Rights: The Fight to Secure America's Liberties. Simon & Schuster.

- Bessler, John D. (2012). Cruel and Unusual: The American Death Penalty and the Founders' Eighth Amendment. University Press of New England.

- Brookhiser, Richard (2011). James Madison. Basic Books.

- Brutus (2008) [1787]. "To the Citizens of the State of New York". In Storing, Herbert J. (ed.). The Complete Anti-Federalist, Volume 1. University of Chicago Press.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2015). The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780385353410 – via Google Books.

- Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and Jay, John (2003). Ball, Terence (ed.). The Federalist: With Letters of Brutus. Cambridge University Press.

- Kyvig, David E. (1996). Explicit and Authentic Acts: Amending the U.S. Constitution, 1776–1995. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0931-8 – via Google Books.

- Labunski, Richard E. (2006). James Madison and the struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford University Press.

- Levy, Leonard W. (1999). Origins of the Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Maier, Pauline (2010). Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. Simon & Schuster.

- Rakove, Jack N. (1996). Original Meanings. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Stewart, David O. (2007). The Summer of 1787. Simon & Schuster.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, Keith (November 18, 2013). "Kerry Makes It Official: 'Era of Monroe Doctrine Is Over'". Wall Street Journal.

- Keck, Zachary (November 21, 2013). "The US Renounces the Monroe Doctrine?". The Diplomat.

- "John Bolton: 'We're not afraid to use the word Monroe Doctrine'". March 3, 2019.

- "What is the Monroe Doctrine? John Bolton's justification for Trump's push against Maduro". The Washington Post. March 4, 2019.

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ "Bill of Rights". history.com. A&E Television Networks.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights – Facts & Summary". History.com.

- ↑ "The Bill Of Rights: A Brief History". ACLU.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights Transcript". Archives.gov.

- ↑ Full text of the Lewis and Clark journals online – edited by Gary E. Moulton, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- ↑ "National Archives photos dating from the 1860s–1890s of the Native cultures the expedition encountered". Archived from the original on February 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lewis and Clark Expedition, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- ↑ "History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark: To the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean" published in 1814; from the World Digital Library

- ↑ Lewis & Clark Fort Mandan Foundation: Discovering Lewis & Clark

- ↑ Corps of Discovery Online Atlas, created by Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576071885.

- ↑ Burgan, Michael (2002). The Louisiana Purchase. Capstone. ISBN 978-0756502102.

- ↑ Fleming, Thomas J. (2003). The Louisiana Purchase. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26738-6.

- ↑ Gayarre, Charles (1867). History of Louisiana.

- ↑ Lawson, Gary & Seidman, Guy (2008). The Constitution of Empire: Territorial Expansion and American Legal History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300128963.

- ↑ Lee, Robert (March 1, 2017). "Accounting for Conquest: The Price of the Louisiana Purchase of Indian Country". Journal of American History. 103 (4): 921–942. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaw504.

- ↑ Library of Congress: Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- ↑ Bailey, Hugh C. (1956). "Alabama's Political Leaders and the Acquisition of Florida" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly. 35 (1): 17–29. ISSN 0015-4113.

- ↑ Brooks, Philip Coolidge (1939). Diplomacy and the borderlands: the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

- ↑ Text of the Adams–Onís Treaty

- ↑ Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Del Bene, Terry. The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History. OUP USA.

- ↑ "Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819". Sons of Dewitt Colony. TexasTexas A&M University.

- ↑ Cash, Peter Arnold (1999), "The Adams–Onís Treaty Claims Commission: Spoliation and Diplomacy, 1795–1824", DAI, PhD dissertation U. of Memphis 1998, 59 (9), pp. 3611-A. DA9905078 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

- ↑ "An Act for carrying into execution the treaty between the United States and Spain, concluded at Washington on the twenty-second day of February, one thousand eight hundred and nineteen"

- ↑ Onís, Luis, “Negociación con los Estados Unidos de América” en Memoria sobre las negociaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos de América, pról. de Jack D.L. Holmes, Madrid, José Porrúa, 1969.

- ↑ Conforti, Joseph. "The Invention of the Great Awakening, 1795–1842". Early American Literature (1991): 99–118. JSTOR 25056853.

- ↑ Griffin, Clifford S. "Religious Benevolence as Social Control, 1815–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1957) 44#3 pp. 423–444. JSTOR 1887019. doi:10.2307/1887019.

- ↑ Mathews, Donald G. "The Second Great Awakening as an organizing process, 1780–1830: An hypothesis". American Quarterly (1969): 23–43. JSTOR 2710771. doi:10.2307/2710771.

- ↑ Shiels, Richard D. "The Second Great Awakening in Connecticut: Critique of the Traditional Interpretation", Church History 49 (1980): 401–415. JSTOR 3164815.

- ↑ Varel, David A. "The Historiography of the Second Great Awakening and the Problem of Historical Causation, 1945–2005". Madison Historical Review (2014) 8#4 [[1]]

- ↑ Brown, Richard H. (1970) [Winter 1966], "Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism", in Gatell, Frank Otto (ed.), Essays on Jacksonian America, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 5–72

- ↑ Miller, William L. (1995), Arguing about Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress, Borzoi Books, Alfred J. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-56922-9

- ↑ Brown, Richard Holbrook (1964), The Missouri compromise: political statesmanship or unwise evasion?, Heath, p. 85

- ↑ Dixon, Mrs. Archibald (1899). The true history of the Missouri compromise and its repeal. The Robert Clarke Company. p. 623.

- ↑ Forbes, Robert Pierce (2007). The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 369. ISBN 9780807831052.

- ↑ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Missouri Compromise" . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ↑ Howe, Daniel Walker (Summer 2010), "Missouri, Slave Or Free?", American Heritage, 60 (2): 21–23

- ↑ Humphrey, D. D., Rev. Heman (1854). THE MISSOURI COMPROMISE. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Reed, Hull & Peirson. p. 32.

- ↑ Moore, Glover (1967), The Missouri controversy, 1819–1821, University of Kentucky Press (Original from Indiana University), p. 383

- ↑ Peterson, Merrill D. (1960). The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. University of Virginia Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-8139-1851-0.

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean (2004), "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited", Journal of the Historical Society, 4 (3): 375–401

- ↑ White, Deborah Gray (2013), Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans, Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, pp. 215–216

- ↑ Woodburn, James Albert (1894), The historical significance of the Missouri compromise, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, p. 297

- ↑ "War of 1812" bibliographical guide by David Curtis Skaggs (2015); Oxford Bibliographies Online

- ↑ Library of Congress Guide to the War of 1812, Kenneth Drexler

- ↑ Benn, Carl (2002). The War of 1812. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-466-5.

- ↑ Latimer, Jon (2007). 1812: War with America. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02584-4.

- ↑ "The Monroe Doctrine (1823)". Basic Readings in U.S. Democracy.

- ↑ Boyer, Paul S., ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 514. ISBN 978-0-19-508209-8.

- ↑ Morison, S.E. (February 1924). "The Origins of the Monroe Doctrine". Economica. doi:10.2307/2547870. JSTOR 2547870.

- ↑ Ferrell, Robert H. "Monroe Doctrine". ap.grolier.com.

- ↑ Lerner, Adrienne Wilmoth (2004). "Monroe Doctrine". Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security.