« The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 214 : | Ligne 214 : | ||

The Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the United States, as it led to the emergence of new denominations, such as the Baptists and Methodists, and it helped to establish a more individualistic and personal approach to religion. Additionally, it has been argued that the Great Awakening also helped to pave the way for the growth of the abolitionist movement and other social reform movements that would emerge in the 19th century. | The Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the United States, as it led to the emergence of new denominations, such as the Baptists and Methodists, and it helped to establish a more individualistic and personal approach to religion. Additionally, it has been argued that the Great Awakening also helped to pave the way for the growth of the abolitionist movement and other social reform movements that would emerge in the 19th century. | ||

It | It was also characterized by a more militant and evangelical form of Protestantism, which was often in conflict with other religious groups such as Catholics and indigenous religious practices.<ref>Conforti, Joseph. "The Invention of the Great Awakening, 1795–1842". Early American Literature (1991): 99–118. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSTOR JSTOR] [https://www.jstor.org/stable/25056853?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents 25056853].</ref><ref>Griffin, Clifford S. "Religious Benevolence as Social Control, 1815–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1957) 44#3 pp. 423–444. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSTOR JSTOR] [https://www.jstor.org/stable/1887019?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents 1887019]. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_object_identifier doi]:[https://academic.oup.com/jah/article-abstract/44/3/423/696178/?redirectedFrom=fulltext 10.2307/1887019].</ref><ref>Mathews, Donald G. "The Second Great Awakening as an organizing process, 1780–1830: An hypothesis". American Quarterly (1969): 23–43. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSTOR JSTOR] [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2710771?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents 2710771]. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_object_identifier doi]:[https://www.jstor.org/stable/2710771?origin=crossref&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents 10.2307/2710771].</ref><ref>Shiels, Richard D. "The Second Great Awakening in Connecticut: Critique of the Traditional Interpretation", Church History 49 (1980): 401–415. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSTOR JSTOR] [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3164815?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents 3164815].</ref><ref>Varel, David A. "The Historiography of the Second Great Awakening and the Problem of Historical Causation, 1945–2005". Madison Historical Review (2014) 8#4 [[https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://en.wikipedia.org/&httpsredir=1&article=1021&context=mhr|online]]</ref>. | ||

The Great Awakening, as a religious movement, had a profound impact on American society during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and it also played a role in shaping the role of women in politics. | The Great Awakening, as a religious movement, had a profound impact on American society during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and it also played a role in shaping the role of women in politics. | ||

| Ligne 232 : | Ligne 232 : | ||

Furthermore, the formation of new religious sects can also be understood as a way for migrants to create a sense of community and belonging in a new and unfamiliar place. Religion can provide a sense of continuity and tradition, and it can also be a source of comfort and support in times of uncertainty. Additionally, it can also be a way for people to assert their own cultural and religious identity in a new place, as well as to link with other migrants who share their beliefs and practices. | Furthermore, the formation of new religious sects can also be understood as a way for migrants to create a sense of community and belonging in a new and unfamiliar place. Religion can provide a sense of continuity and tradition, and it can also be a source of comfort and support in times of uncertainty. Additionally, it can also be a way for people to assert their own cultural and religious identity in a new place, as well as to link with other migrants who share their beliefs and practices. | ||

The Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the United States, as it led to the emergence of new denominations, such as the Baptists and Methodists, and it helped to establish a more individualistic and personal approach to religion. | |||

The Great Awakening its impact on communities | |||

The | The Great Awakening had a significant impact on both women and Black people in the United States during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. | ||

For Black people, the Great Awakening was a significant moment in the development of their religious and cultural identity. Many Black people were forcibly displaced from Africa and brought to the Americas as slaves. They were often denied access to traditional religious practices and forced to convert to Christianity. The Great Awakening provided an opportunity for Black people to assert their own religious identity and to create new religious communities that reflected their own beliefs and values. | |||

One of the most notable examples of this is the African Evangelical Apostolic Church, which was founded in 1801 by a group of free Black people in Philadelphia. This church was established in response to the racism and discrimination that Black people faced in white churches. It was one of the first Black churches in the United States, and it played an important role in the development of the Black church as a cultural and religious institution. | |||

Additionally, the Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the enslaved Black people. The Great Awakening provided an opportunity for enslaved people to connect with their faith, and to find solace in the midst of their difficult circumstances. Many enslaved people found comfort in the message of salvation and redemption, which was central to the Great Awakening. | |||

Even though the Great Awakening provided an opportunity for Black people to assert their own religious identity, they still faced many barriers and discrimination. They were often segregated in their religious communities, and their religious practices were often suppressed. However, the Great Awakening was a significant moment in the development of Black religious culture and identity, and it would set the stage for the later emergence of Black-led religious movements, such as the Black theology. | |||

Around 1810, 100,000 slaves were forcibly displaced to the West. Slavery spread and hardened. In 1770, there were 450,000 slaves in the 13 colonies; by 1820, there were 1.5 million. | Around 1810, 100,000 slaves were forcibly displaced to the West. Slavery spread and hardened. In 1770, there were 450,000 slaves in the 13 colonies; by 1820, there were 1.5 million. | ||

Version du 18 janvier 2023 à 11:05

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The United States Constitution, which was adopted in 1787, lays out the framework for the federal government and its powers. It also includes a Bill of Rights, which outlines individual rights and freedoms. The Constitution has been amended 27 times throughout history, and it is still in force today. The course focuses on understanding the development of the Constitution and the tensions it generated leading up to the Civil War, which was fought from 1861 to 1865. The course also examines the changes in politics, religion, and society that led to the formation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. This doctrine established the principle that the United States would consider any attempt by European nations to colonize or interfere with the nations of the Americas as a threat to its own security. By studying the United States around 1800, one can gain insight into the country's political and social history and how it continues to shape the nation today.

The Articles of Confederation and the Constitutions of the various States

Shortly after independence in 1776, the States of the Union signed the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation were adopted by the thirteen original states of the United States in 1777 and served as the country's first constitution. They were written as a reaction to the centralized authority of the British government, which the colonies had just fought to gain independence from. The Articles of Confederation established a weak central government with most of the powers remaining with the individual states. The central government could not raise taxes, regulate commerce, or enforce laws effectively, which led to numerous problems and challenges for the young nation. As a result, many leaders began to call for a stronger central government, which ultimately led to the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787.

After achieving independence from Britain, each of the 13 original states plus Vermont adopted its own constitution. These state constitutions reflected the diverse political and cultural beliefs of the people within each state and set out the structure and powers of the state government. However, as the nation began to face challenges such as economic instability and threats to national security, many leaders recognized the need for a stronger and more unified government. This led to the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787, which established a federal system of government with a clear division of powers between the national government and the state governments. The preamble to the Constitution lays out the reasons for its creation, emphasizing the goal of forming a more perfect union and securing the benefits of liberty for all citizens.

During the early years of the United States, each state had its own constitution and system of government, which reflected the different political and social beliefs of the people within each state. Some states, like Pennsylvania, had relatively egalitarian government systems, with universal suffrage for white men who paid taxes and a single assembly with a collegial executive. Other states, like Maryland, had more hierarchical systems of government, with an assembly and a senate and concentrated executive power in the hands of a governor who was elected by the wealthy landowners, who also had the right to vote. New Jersey also had limited suffrage, where the right to vote was restricted to those who met certain property ownership requirements, including women who have been rich for a long time. These differences in state government were one of the factors that led to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, which aimed to establish a more unified and effective national government to address the challenges facing the young nation.

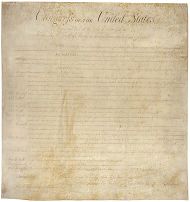

The diversity in state government and political beliefs during the early years of the United States was a significant factor that led to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution aimed to establish a more unified and effective national government to address the challenges facing the young nation. The Bill of Rights, the first of ten amendments to the Constitution, were adopted in 1791 and were added to protect the individual rights of citizens from the potential abuse of power by the government. The Bill of Rights guarantees the equality of men and protects individual rights such as freedom of speech, religion, and peaceful assembly. The Bill of Rights also protects property rights, due process and a fair trial.

The Bill of rights did not protect the rights of all citizens at the time, as it did not include rights for enslaved people and Native Americans, and rights for women were also limited. As a result, it took many years and many struggles for these groups to gain their rights.

At the time of the drafting of the U.S. Constitution in 1787, slavery existed in all of the 13 original states. Still, the institution of slavery was not treated equally in every state. Some states, like Vermont, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, had abolished slavery shortly after gaining independence from Britain. Other states, such as Pennsylvania and New York, passed gradual abolition laws that slowly phased out slavery over time. However, in states such as South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, slavery was deeply ingrained in their economies and society, and the institution of slavery was not abolished.

Furthermore, in all states except South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, there was no legal exclusion of Black people from voting or participating in politics. However, in practice, many barriers to voting and political participation were imposed by law and custom, which effectively denied many Black people the right to vote.

Throughout the South, slavery hardened after independence, and the number of slaves increased through imports and natural growth. This led to a growing divide between the North and South over the issue of slavery, which ultimately led to the Civil War.

The Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865, was fought primarily over the issue of slavery and states' rights, and the tensions between the North and South came to a head. The war resulted in the abolition of slavery and the destruction of the slave-based economy in the South. After the war, the United States faced significant challenges in rebuilding the country and addressing the social and economic issues that had led to the conflict.

During this time, the U.S. government, under the leadership of President Andrew Johnson, attempted to implement a plan of Reconstruction that focused on restoring the southern states to the Union as quickly as possible and with minimal disruption to the social and economic order. However, this plan faced significant opposition from Congress and many citizens, who believed that more radical measures were needed to ensure the rights of newly freed slaves and promote economic and social equality.

As a result, the U.S. government implemented a new constitutional amendment, the 13th, 14th and 15th amendment, which abolished slavery, granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, regardless of race, and gave voting rights to the African American men. These amendments were a part of a stronger, more centralized government and aimed to address the issues that led to the Civil War, and to ensure a more perfect Union.

The Philadelphia Constitutional Convention

The Philadelphia Constitutional Convention, which was held in 1787, was attended by 55 men, mostly lawyers and politicians, who were tasked with drafting a new constitution for the United States. Among them, 19 were large enslavers. During the convention, there were significant debates and disagreements over several key issues, including the structure of the government and the question of who would be able to vote.

One of the main debates centred around whether the right to vote should be limited to landowners or whether it should be considered a natural right of every free man. This debate was complicated because the Declaration of Independence had stated that "all men are created equal," but whether this included enslaved people and non-landowners remained unresolved.

Another important issue that was debated was slavery and the status of free slaves. The Southern states argued for the protection of their institution of slavery and the continuation of the transatlantic slave trade. In contrast, the Northern states opposed the expansion of slavery and sought to limit or abolish it. These debates ultimately led to the inclusion of the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted each enslaved person as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of apportioning representation in the U.S. House of Representatives, and the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required the return of runaway slaves to their owners. These compromises helped to resolve some of the tensions and enabled the drafting of the Constitution, but also set the stage for further conflicts over slavery in the future.

Silences, concessions and achievements of the Constitution of 1787

The U.S. Constitution is a document that has been able to endure for more than 200 years because it is a compromise between different groups of people with different ideas and interests. The language used in the Constitution is often vague and open to interpretation, which allows for different interpretations and applications over time. This flexibility has helped the Constitution adapt to changing circumstances and remain relevant throughout the country's history.

The Constitution's opening phrase "We the People" was intended to emphasize the idea that the document was created by and for the people of the United States. However, the Constitution does not clearly define who is considered part of "the people." This lack of definition was a deliberate compromise made by the framers to avoid potential conflicts over who should be included in the new government. Additionally, the Constitution does not mention slavery directly. Instead, it uses language that allows for the continuation of the practice, such as the three-fifths compromise, which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person to determine representation in Congress. The framers made this compromise to secure the support of southern states that relied on slavery for their economy.

The U.S. Constitution is a federal document, which means that it outlines the structure and powers of the national government, but it also leaves many powers to the individual states. Each state has its own constitution, which outlines the structure and powers of the state government. Additionally, each state has the power to define its own citizenship requirements. This means that the qualifications and rights of a citizen can vary from state to state. This system is known as federalism, which divides the power between the national government and the state government. This allows the states to have some autonomy while still being part of the larger federal union.

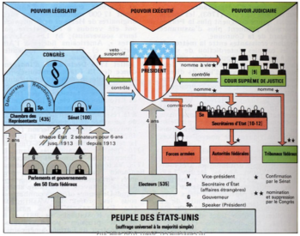

The Constitution establishes a system of separation of powers, dividing the government into three branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial. The legislative branch, which makes the laws, is composed of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention decided that the Senate would be composed of two senators per state, giving each state equal representation regardless of population. In contrast, the House of Representatives is based on population, with each state receiving a number of representatives proportional to its population. This representation system was intended to balance the interests of smaller states with those of larger states, and to ensure that the government would be responsive to the needs of the people. The separation of powers also helps to prevent any one branch from becoming too powerful, and allows for checks and balances between the branches.

In 1787, during the drafting of the Constitution, the delegates from the northern states made a significant concession to the slaveholding states, accepting the so-called "Three-fifths Compromise." This compromise stipulated that for the purpose of determining representation in Congress, enslaved people would be counted as three-fifths of a person. This meant that the number of representatives from the slaveholding states would be based on the number of free inhabitants, plus three-fifths of the slave population of their state. This compromise allowed the southern states to increase their representation in Congress and maintain a balance of power with the northern states. However, it also meant that the Constitution treated enslaved people as less than full human beings, and this compromise has been widely criticized as a moral failing of the Constitution.

During the drafting of the Constitution, there was significant debate over the role and powers of the executive branch, specifically the President. Some delegates wanted a strong President, with powers similar to that of a constitutional monarchy, while others opposed anything resembling a monarchy. As a compromise, the Constitution created a President with veto power over legislation passed by Congress, and a Vice President who is not directly elected by the people but chosen by an electoral college of electors. This system was intended to balance the need for a strong executive leader with the desire to avoid a monarchy-like figure. The President would have the ability to veto legislation and act as a check on the power of the legislative branch, but the Vice President would not be elected directly by the people, and would serve as a tie-breaker in the event that the electoral college was unable to reach a decision.

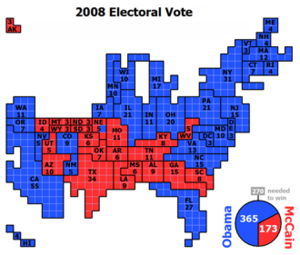

The electoral college is a system established by the Constitution in which each state has a number of electors equal to the number of its representatives in the House of Representatives plus two for its Senators. These electors then cast votes for the President and Vice President. The candidate who receives a majority of electoral votes, at least 270 out of 538, becomes the President. The rules for the electoral college have been amended over the years, mostly in the form of the 12th and 23rd amendment. The 12th amendment, ratified in 1804, changes the way the president and vice president are elected. Instead of voting for two candidates without specifying which is for president and which is for vice president, electors must now vote for one candidate for president and another for vice president. The 23rd amendment ratified in 1961, gives the residents of the District of Columbia the right to vote in presidential elections.

On Presidential Election Day, voters in each state elect a group of electors, known as the Electoral College, who will then cast votes for the President and Vice President. Today, most states use a "winner-takes-all" method, where the political party that wins the majority of votes in the state wins all of that state's electoral votes. This system creates an incentive for candidates to focus on states where they have a good chance of winning a majority of votes, and explains why the majority of campaign events and advertising take place in states with large populations, like Florida.

It's worth mentioning that Maine and Nebraska are the two states that use a different method, the "congressional district method", where two electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the state's popular vote, and the remaining electoral votes are awarded to the winner of each congressional district.

This system has been criticized because it can result in a situation where a candidate wins the popular vote but loses the election because of the way electoral votes are allocated. This has happened multiple times in U.S history, most recently in 2000.

In the United States, citizens do not directly elect the President through a system of universal suffrage, where every citizen has an equal vote. Instead, the President is elected through the Electoral College system, where each state is allocated a certain number of electors based on its population. These electors then cast their votes for the President. It is possible for a candidate to win the election without receiving a majority of the popular vote. This can happen if a candidate wins a majority of the electoral votes, which are allocated to states based on population, even if they do not win the popular vote. This has happened in several U.S. presidential elections, most recently in 2016. This system has been criticized for being undemocratic, as it can result in a candidate winning the election without having the support of a majority of the citizens.

In 1787, the delegates at the Constitutional Convention agreed to create a strong judiciary, including a Supreme Court, with the power to review the actions of the other branches of government and ensure that they are in compliance with the Constitution. The Supreme Court, originally composed of six judges, now nine, is appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate. Once appointed, Justices serve for life, or until they choose to retire. The idea behind the lifetime appointment is to ensure that the Justices are independent from political pressure and can make impartial decisions. The Supreme Court is considered the final authority on all matters related to constitutional law and can declare acts of Congress or the President unconstitutional if they violate the Constitution. This system of checks and balances helps to protect individual rights and maintain the balance of power between the branches of government.

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the northern delegates made several concessions to the slave-owning southern states, which were designed to secure the support of those states for the new Constitution. One such concession was the Three-fifths Compromise, which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of determining representation in Congress. This compromise allowed the southern states to increase their representation in Congress and maintain a balance of power with the northern states.

This and other compromises made by the northern states during the convention, such as the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required the return of runaway slaves to their owners, highlighted the limits of the concept of equality in the new nation, and the fact that the rights of enslaved people were not considered in the formation of the new government. These compromises were a clear indication that the Constitution was a product of its time, reflecting the economic and social realities of the time, and they have been widely criticized as a moral failing of the Constitution.

During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the northern states approved the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required states that had already abolished slavery to return fugitive slaves from the South to their owners. This clause was designed to appease the slave-owning southern states and secure their support for the new Constitution. It was a harsh provision that went against the principles of freedom and made it difficult for enslaved people to escape to freedom.

The northern states also agreed to postpone the ban on importing new slaves from Africa for 20 years, until 1808. This allowed for the continuation of the transatlantic slave trade for another two decades, and resulted in the importation of a large number of enslaved people from Africa. The domestic slave trade within the United States, however, continued until the abolition of slavery in 1865.

These compromises made by the northern states during the convention, show the deep-seated conflicts within the newly formed nation over the issue of slavery, and the challenges in balancing the interests of the northern and southern states while trying to form a united nation.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was not only marked by the compromise over slavery, but also by the tension between the states over the balance of power between the central federal government and the individual states. One of the key issues was the question of taxation and the power of the federal government to levy taxes on the entire territory. This caused concerns among smaller states that they would lose their autonomy and be dominated by the larger states.

The drafting of the Constitution was a long and difficult process, and it was not until three years later, in 1790, that the last holdout states ratified it. In order to secure ratification, several states insisted on the addition of amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, which guaranteed individual rights and freedoms, and placed limits on the power of the federal government.

These amendments, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, were added in 1791, and provide individuals with rights such as freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and the right to a fair trial, among others. They also limit the powers of the government and provide for the separation of powers and federalism.

The Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights refers to the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution.[11] These amendments were added in 1791, soon after the Constitution was ratified, in order to address concerns that the Constitution did not adequately protect individual rights and freedoms. The Bill of Rights guarantees individual rights such as:

- First Amendment: Freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and petition

- Second Amendment: The right to bear arms

- Third Amendment: Protection against the quartering of soldiers

- Fourth Amendment: Protection against unreasonable searches and seizures

- Fifth Amendment: Protection against self-incrimination and double jeopardy and the right to a fair trial

- Sixth Amendment: The right to a fair trial, including the right to a public trial, an impartial jury, and the right to counsel

- Seventh Amendment: The right to a trial by jury in civil cases

- Eighth Amendment: Protection against cruel and unusual punishment

- Ninth Amendment: The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage other retained by the people

- Tenth Amendment: Powers not delegated to the federal government by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states or to the people.

These amendments have played a crucial role in shaping the legal and political landscape of the United States, and have helped to ensure that individual rights and freedoms are protected from government overreach.

The Bill of Rights protects several fundamental freedoms, including:

- Freedom of religion: The First Amendment guarantees the right to practice any religion or no religion at all, and prohibits the government from establishing a national religion or interfering with the free exercise of religion.

- Freedom of expression: The First Amendment also guarantees the right to free speech, which includes the freedom to express one's opinions and ideas without government censorship or retaliation.

- Freedom of the press: The First Amendment also guarantees the freedom of the press, which includes the right to publish information and ideas without government censorship or punishment.

- Freedom of peaceful assembly: The First Amendment guarantees the right to peaceful assembly, which includes the right to gather together and express one's opinions and ideas without government interference.

- Freedom of petition: The First Amendment also guarantees the right to petition the government for a redress of grievances, which includes the right to ask the government to take action on a particular issue or to change a law or policy.

- Right to bear arms: The Second Amendment guarantees the right to bear arms, which is often interpreted as the right of individuals to own firearms for self-defense and the defense of the state.

- Protection against abuses by the state, police, and justice: The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments provide protection against abuses of power by the state, police, and justice system. These amendments protect individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, protection against self-incrimination and double jeopardy, the right to a fair trial, protection against cruel and unusual punishment, and the right to a public trial, an impartial jury, and the right to counsel.

The Bill of Rights, which is the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution, is preceded by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in France, which was adopted during the French Revolution in 1789. Both the Bill of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen are designed to protect individual rights and freedoms from government overreach.

However, there are some key differences between the two documents. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is more focused on the common good and the principles of equality and fraternity. It emphasizes the rights of citizens as a whole, rather than the rights of individual citizens. In contrast, the Bill of Rights is more individualistic and focuses on protecting the rights and freedoms of individual citizens from government abuse of power.

The Bill of Rights also includes several rights that protect individuals against arbitrary action by the state, such as the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Eighth amendments, which protect individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, protection against self-incrimination and double jeopardy, the right to a fair trial, protection against cruel and unusual punishment, and the right to a public trial, an impartial jury, and the right to counsel.

Overall, both the Bill of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen have played a crucial role in shaping the legal and political landscape of their respective countries and have served as a model for protecting individual rights and freedoms.

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees the right to bear arms, is one of the most debated and controversial amendments in the Bill of Rights. The amendment states that "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

The meaning and interpretation of this amendment has been the subject of much debate, with different interpretations of the phrase "well regulated Militia" and the meaning of "the right of the people to keep and bear Arms." Some argue that the amendment guarantees an individual right to own firearms for personal self-defense, while others argue that it only guarantees the right to bear arms as part of a well-regulated militia.

The Second Amendment has been the subject of much debate in the courts and in political circles, with ongoing discussions about gun control laws and regulations, and the balance between the right to bear arms and public safety. The fact that the amendment is open to different interpretation is what makes it a malleable one, and the interpretation of it has changed over time.

The Bill of Rights, including the Tenth Amendment, which limits the powers of the federal government to those specifically enumerated in the Constitution, is designed to protect individual rights and freedoms from government overreach. However, it must be acknowledged that the Constitution, including the Bill of Rights, was adopted at a time when slavery was still legal and widespread in the United States, and the rights and freedoms it guarantees were not extended to enslaved people or to women.

The fact that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were adopted without calling slavery into question, and that they did not explicitly address the rights of enslaved people or women, tacitly confirms the exclusion of these groups from the protections and rights guaranteed by the Constitution. This is a historical limitation of the Constitution, and it highlights the need to continue working towards greater equality and inclusivity in the interpretation and application of the Constitution.

Society at the beginning of the 19th century

Territorial expansion

The United States at the beginning of the 19th century was rapidly expanding its territory through a combination of purchases, treaties, and military conquests. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, in which the U.S. purchased a vast tract of land from France, was a significant expansion of American territory. The Lewis and Clark Expedition, which explored this new land, began in 1804. The War of 1812 also saw the U.S. gain territory from British North America. Additionally, the U.S. also annexed Florida from Spain in 1819 and Texas from Mexico in 1845. This territorial expansion would lead to conflicts with Native American tribes, as well as with Mexico, which ultimately resulted in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

"Lewis and Clark on the Columbia River", painted by Charles Marion Russell.

The Louisiana Purchase was a land deal between the United States and France, in which the U.S. acquired approximately 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for the sum of $15 million. The land, which had been controlled by France and recently returned by Spain, doubled the size of the United States and provided valuable resources such as fertile land for agriculture and access to the Mississippi River for transportation and trade. The purchase was arranged by U.S. President Thomas Jefferson and his representatives, and was completed in 1803. Napoleon Bonaparte, the emperor of France at the time, agreed to the sale in order to raise funds for his ongoing war in Haiti. The Louisiana Purchase is considered one of the most significant events in American history, as it greatly expanded the nation's territory and contributed to its westward expansion.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. The Louisiana Purchase was primarily a vast territory with a small population and many American Indian tribes. The United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1819 through a treaty called the Adams-Onis Treaty, which was named after the U.S. and Spanish negotiators. Spain ceded Florida to the United States in exchange for the U.S. renouncing its claims to Texas and paying off $5 million in claims by American citizens against Spain. The acquisition of Florida also doubled the territory of the United States and provided valuable resources such as ports, fertile land, and a location for military posts. However, the acquisition of Florida and Louisiana Purchase also displaced many American Indian tribes and led to conflicts over land rights and sovereignty.

[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33].

Bipartism

The two main political parties that emerged in the United States during the late 18th and early 19th centuries were the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. These parties formed in the aftermath of the constitutional debates and the adoption of the US Constitution, as different groups of people had different interpretations of what the Constitution meant and how the government should be run. These two parties set the stage for the modern two-party system in the United States, with the Federalists eventually fading away and the Democratic-Republican party splitting into the modern Democratic and Republican parties.

The Federalists, led by George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, were generally in favor of a strong federal government and good relations with Britain. They were supported by merchants, manufacturers, and wealthy landowners, and were mainly based in the Northeastern states.

The Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, were generally in favor of a limited central government and a more populist approach to politics. They were influenced by the ideas of the French Revolution, but did not support racial equality. They were mainly supported by farmers, planters and frontiersmen, and were mainly based in the Southern and Western states.

These two parties are the first two-party system in the US and set the stage for the modern two-party system in the United States, with the Federalists eventually fading away and the Democratic-Republican party splitting into the modern Democratic and Republican parties.

The political discourse between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans during the early years of the United States was often characterized by strong rhetoric and accusations. The 1800 presidential election, in particular, was a contentious and highly polarized campaign.

The Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, accused the Federalists of being monarchical and too closely aligned with Britain. They portrayed the Federalists as out of touch with the common people and too willing to sacrifice American interests for the sake of maintaining good relations with Britain.

The Federalists, led by John Adams, accused the Democratic-Republicans of being radical Jacobins and anarchists, who were influenced by the excesses of the French Revolution. They portrayed the Democratic-Republicans as dangerous radicals who wanted to overthrow the existing order and bring about chaos and anarchy.

The election of 1800 was a significant moment in American history as it marked the first peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another, and it established the two-party system in the United States.

Religion

A "Great Awakening" took place in the United States during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and it was characterized by a resurgence of religious fervor and an increase in religious activity. This religious revival movement was led by a number of prominent preachers, such as Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and Charles Finney, who traveled throughout the country, giving powerful and emotive sermons that attracted large numbers of people.

The Great Awakening was particularly influential in the region of the Louisiana Purchase, where it played an important role in shaping the religious and cultural landscape. The expansion of American territory into the West brought many new settlers into contact with different religious traditions, and the Great Awakening provided an opportunity for these settlers to assert their own religious identity.

The Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the United States, as it led to the emergence of new denominations, such as the Baptists and Methodists, and it helped to establish a more individualistic and personal approach to religion. Additionally, it has been argued that the Great Awakening also helped to pave the way for the growth of the abolitionist movement and other social reform movements that would emerge in the 19th century.

It was also characterized by a more militant and evangelical form of Protestantism, which was often in conflict with other religious groups such as Catholics and indigenous religious practices.[34][35][36][37][38].

The Great Awakening, as a religious movement, had a profound impact on American society during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and it also played a role in shaping the role of women in politics.

During the Great Awakening, women were active participants in religious revivals and camp meetings, where they were often seen as equal partners in the religious experience. They were encouraged to participate in religious activities such as singing, praying and testifying, that were traditionally led by men. This experience allowed women to develop their public speaking skills and gain confidence in their ability to lead and participate in public discourse.

Additionally, the Great Awakening also led to the formation of new religious denominations such as the Methodists and Baptists that welcomed women as preachers and leaders. This allowed many women to take on leadership roles within their religious communities, and many of these women went on to become leaders in other areas of society, including politics.

As a result, the Great Awakening played a significant role in advancing women's participation in public life and helped to pave the way for the women's rights movement in the 19th century. It helped to challenge traditional gender roles, and encouraged women to be more active in public life, and in politics, by giving them the opportunity to develop their leadership skills and self-confidence.

Even though the Great Awakening provided an opportunity for women to participate in politics, they still faced many barriers and discrimination, as the society was still patriarchal and women didn't have the right to vote until much later.

The Great Awakening was characterized by large religious revivals and camp meetings, which attracted thousands of people. One such camp meeting, held in Cane Ridge, Kentucky in 1801, is estimated to have brought together as many as 20,000 people. These camp meetings were a key feature of the Great Awakening and provided an opportunity for people to come together to hear sermons, pray, and participate in religious activities.

The development of new religious sects during this time period can be understood as a response to the rapid expansion of the American frontier. As new settlers moved westward, they often found themselves in areas where there were few established churches or religious institutions. The Great Awakening provided an opportunity for these settlers to create new religious communities that reflected their own beliefs and values.

Furthermore, the formation of new religious sects can also be understood as a way for migrants to create a sense of community and belonging in a new and unfamiliar place. Religion can provide a sense of continuity and tradition, and it can also be a source of comfort and support in times of uncertainty. Additionally, it can also be a way for people to assert their own cultural and religious identity in a new place, as well as to link with other migrants who share their beliefs and practices.

The Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the United States, as it led to the emergence of new denominations, such as the Baptists and Methodists, and it helped to establish a more individualistic and personal approach to religion.

The Great Awakening its impact on communities

The Great Awakening had a significant impact on both women and Black people in the United States during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

For Black people, the Great Awakening was a significant moment in the development of their religious and cultural identity. Many Black people were forcibly displaced from Africa and brought to the Americas as slaves. They were often denied access to traditional religious practices and forced to convert to Christianity. The Great Awakening provided an opportunity for Black people to assert their own religious identity and to create new religious communities that reflected their own beliefs and values.

One of the most notable examples of this is the African Evangelical Apostolic Church, which was founded in 1801 by a group of free Black people in Philadelphia. This church was established in response to the racism and discrimination that Black people faced in white churches. It was one of the first Black churches in the United States, and it played an important role in the development of the Black church as a cultural and religious institution.

Additionally, the Great Awakening also had a significant impact on the religious culture of the enslaved Black people. The Great Awakening provided an opportunity for enslaved people to connect with their faith, and to find solace in the midst of their difficult circumstances. Many enslaved people found comfort in the message of salvation and redemption, which was central to the Great Awakening.

Even though the Great Awakening provided an opportunity for Black people to assert their own religious identity, they still faced many barriers and discrimination. They were often segregated in their religious communities, and their religious practices were often suppressed. However, the Great Awakening was a significant moment in the development of Black religious culture and identity, and it would set the stage for the later emergence of Black-led religious movements, such as the Black theology.

Around 1810, 100,000 slaves were forcibly displaced to the West. Slavery spread and hardened. In 1770, there were 450,000 slaves in the 13 colonies; by 1820, there were 1.5 million.

Among the slaves there is a parallel with the enslaved Jewish people in Egypt. In this movement, black preachers emerge.

Religion played a covering role for the women, but also for the slaves, allowing them to carve out a place in society through religion.

Growth of slavery

Since the purchase of Louisiana in 1803, the issue of slavery and the balance between slave and non-slave states has been growing.

Since 1800, 20 new states have joined the Union. Of the 22 states that made up the Union in 1819, there is a precarious balance between slave and non-slave states.

In 1819, Missouri applied to join the Union as a slave state. A long debate ensues in Congress, because the big question is the Senate. If you have a large majority of slave states, that means that the majority of senators are slave states, which means that slavery could be forced into the non-slave states. This will lead to the Civil War.

After a year of debate, the "Missouri Compromise" was reached with the creation of a free state to have 12 slave and 12 non-slave states[39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51].

The beginning of American nationalism

The revival of nationalism

It is a nationalism that was to be revived in 1812 when the United States launched a new war against England to expand its northern borders[52][53][54][55]. The idea is to push the English back north, but it was a failure.

In addition, the United States had no navy, and Great Britain was imposing a blockade on the seas and coasts of the United States, which would have the effect of strengthening nationalism.

The United States did not gain a square metre, but the big losers were the defeated Indian nations who opened up all the territories south of the Great Lakes to the new white settlers. All this still very Indian part will see massacres and exodus.

The consequence of this war is an upsurge in nationalism and self-confidence. Artists began to represent the myth of an agrarian society. The English embargo allows the first development of factories mainly on the east coast of the United States competing with the English.

It is also a time when we realize that in order to control the territory we have to build roads and canals which is very important to develop the colonization of the territory.

On the other hand, the rulers were interested in education and public health, which led to the development of infrastructures. It is also the birth of an American architecture, but which in fact imitates the Greco-Roman style. Thomas Jefferson will go so far as to design his own house inspired by ancient constructions.

Nationalism also translates into the strengthening of the army with the creation of the United States Military Academy of West Point.

The Monroe Doctrine

This doctrine marks the beginning of the imperialist vision of the United States[56][57][58][59][60]. Its context is the victory of the Haitian revolution, the independence of Brazil and the Spanish colonies from Mexico to the very bottom of South America. This will stir up the lust of Great Britain. It is a unilateral declaration by the government of the United States under President Adams, which is against any interference from Europe in the Americas, which were already largely independent in 1823.

This doctrine includes the demand for non-colonisation by European powers in the western hemisphere, particularly with regard to Alaska, and the non-intervention of European powers in the affairs of the American continent.

- non-interference by the United States in the affairs of Europe, including the European colonies. At the time, this doctrine went virtually unnoticed, because the great power of the day was Great Britain, which was respected in the Americas by its Royal Navy.

The Monroe Doctrine marks the beginning of American ambitions for the Americas and then for the world that will take shape over the decades.

Annexes

- La doctrine de Monroe, un impérialisme masqué par François-Georges Dreyfus, Professeur émérite de l'université Paris Sorbonne-Paris IV.

- La doctrine Monroe de 1823

- Nova Atlantis in Bibliotheca Augustana (Latin version of New Atlantis)

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1998). The Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. Random House.

- Berkin, Carol (2015). The Bill of Rights: The Fight to Secure America's Liberties. Simon & Schuster.

- Bessler, John D. (2012). Cruel and Unusual: The American Death Penalty and the Founders' Eighth Amendment. University Press of New England.

- Brookhiser, Richard (2011). James Madison. Basic Books.

- Brutus (2008) [1787]. "To the Citizens of the State of New York". In Storing, Herbert J. (ed.). The Complete Anti-Federalist, Volume 1. University of Chicago Press.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2015). The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780385353410 – via Google Books.

- Hamilton, Alexander, Madison, James, and Jay, John (2003). Ball, Terence (ed.). The Federalist: With Letters of Brutus. Cambridge University Press.

- Kyvig, David E. (1996). Explicit and Authentic Acts: Amending the U.S. Constitution, 1776–1995. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0931-8 – via Google Books.

- Labunski, Richard E. (2006). James Madison and the struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford University Press.

- Levy, Leonard W. (1999). Origins of the Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Maier, Pauline (2010). Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. Simon & Schuster.

- Rakove, Jack N. (1996). Original Meanings. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Stewart, David O. (2007). The Summer of 1787. Simon & Schuster.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, Keith (November 18, 2013). "Kerry Makes It Official: 'Era of Monroe Doctrine Is Over'". Wall Street Journal.

- Keck, Zachary (November 21, 2013). "The US Renounces the Monroe Doctrine?". The Diplomat.

- "John Bolton: 'We're not afraid to use the word Monroe Doctrine'". March 3, 2019.

- "What is the Monroe Doctrine? John Bolton's justification for Trump's push against Maduro". The Washington Post. March 4, 2019.

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ "Bill of Rights". history.com. A&E Television Networks.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights – Facts & Summary". History.com.

- ↑ "The Bill Of Rights: A Brief History". ACLU.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights Transcript". Archives.gov.

- ↑ Full text of the Lewis and Clark journals online – edited by Gary E. Moulton, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- ↑ "National Archives photos dating from the 1860s–1890s of the Native cultures the expedition encountered". Archived from the original on February 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lewis and Clark Expedition, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- ↑ "History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark: To the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean" published in 1814; from the World Digital Library

- ↑ Lewis & Clark Fort Mandan Foundation: Discovering Lewis & Clark

- ↑ Corps of Discovery Online Atlas, created by Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576071885.

- ↑ Burgan, Michael (2002). The Louisiana Purchase. Capstone. ISBN 978-0756502102.

- ↑ Fleming, Thomas J. (2003). The Louisiana Purchase. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26738-6.

- ↑ Gayarre, Charles (1867). History of Louisiana.

- ↑ Lawson, Gary & Seidman, Guy (2008). The Constitution of Empire: Territorial Expansion and American Legal History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300128963.

- ↑ Lee, Robert (March 1, 2017). "Accounting for Conquest: The Price of the Louisiana Purchase of Indian Country". Journal of American History. 103 (4): 921–942. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaw504.

- ↑ Library of Congress: Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- ↑ Bailey, Hugh C. (1956). "Alabama's Political Leaders and the Acquisition of Florida" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly. 35 (1): 17–29. ISSN 0015-4113.

- ↑ Brooks, Philip Coolidge (1939). Diplomacy and the borderlands: the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

- ↑ Text of the Adams–Onís Treaty

- ↑ Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Del Bene, Terry. The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History. OUP USA.

- ↑ "Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819". Sons of Dewitt Colony. TexasTexas A&M University.

- ↑ Cash, Peter Arnold (1999), "The Adams–Onís Treaty Claims Commission: Spoliation and Diplomacy, 1795–1824", DAI, PhD dissertation U. of Memphis 1998, 59 (9), pp. 3611-A. DA9905078 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

- ↑ "An Act for carrying into execution the treaty between the United States and Spain, concluded at Washington on the twenty-second day of February, one thousand eight hundred and nineteen"

- ↑ Onís, Luis, “Negociación con los Estados Unidos de América” en Memoria sobre las negociaciones entre España y los Estados Unidos de América, pról. de Jack D.L. Holmes, Madrid, José Porrúa, 1969.

- ↑ Conforti, Joseph. "The Invention of the Great Awakening, 1795–1842". Early American Literature (1991): 99–118. JSTOR 25056853.

- ↑ Griffin, Clifford S. "Religious Benevolence as Social Control, 1815–1860", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1957) 44#3 pp. 423–444. JSTOR 1887019. doi:10.2307/1887019.

- ↑ Mathews, Donald G. "The Second Great Awakening as an organizing process, 1780–1830: An hypothesis". American Quarterly (1969): 23–43. JSTOR 2710771. doi:10.2307/2710771.

- ↑ Shiels, Richard D. "The Second Great Awakening in Connecticut: Critique of the Traditional Interpretation", Church History 49 (1980): 401–415. JSTOR 3164815.

- ↑ Varel, David A. "The Historiography of the Second Great Awakening and the Problem of Historical Causation, 1945–2005". Madison Historical Review (2014) 8#4 [[1]]

- ↑ Brown, Richard H. (1970) [Winter 1966], "Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism", in Gatell, Frank Otto (ed.), Essays on Jacksonian America, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 5–72

- ↑ Miller, William L. (1995), Arguing about Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress, Borzoi Books, Alfred J. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-56922-9

- ↑ Brown, Richard Holbrook (1964), The Missouri compromise: political statesmanship or unwise evasion?, Heath, p. 85

- ↑ Dixon, Mrs. Archibald (1899). The true history of the Missouri compromise and its repeal. The Robert Clarke Company. p. 623.

- ↑ Forbes, Robert Pierce (2007). The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 369. ISBN 9780807831052.

- ↑ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Missouri Compromise" . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ↑ Howe, Daniel Walker (Summer 2010), "Missouri, Slave Or Free?", American Heritage, 60 (2): 21–23

- ↑ Humphrey, D. D., Rev. Heman (1854). THE MISSOURI COMPROMISE. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Reed, Hull & Peirson. p. 32.

- ↑ Moore, Glover (1967), The Missouri controversy, 1819–1821, University of Kentucky Press (Original from Indiana University), p. 383

- ↑ Peterson, Merrill D. (1960). The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. University of Virginia Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-8139-1851-0.

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean (2004), "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited", Journal of the Historical Society, 4 (3): 375–401

- ↑ White, Deborah Gray (2013), Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans, Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, pp. 215–216

- ↑ Woodburn, James Albert (1894), The historical significance of the Missouri compromise, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, p. 297

- ↑ "War of 1812" bibliographical guide by David Curtis Skaggs (2015); Oxford Bibliographies Online

- ↑ Library of Congress Guide to the War of 1812, Kenneth Drexler

- ↑ Benn, Carl (2002). The War of 1812. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-466-5.

- ↑ Latimer, Jon (2007). 1812: War with America. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02584-4.

- ↑ "The Monroe Doctrine (1823)". Basic Readings in U.S. Democracy.

- ↑ Boyer, Paul S., ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 514. ISBN 978-0-19-508209-8.

- ↑ Morison, S.E. (February 1924). "The Origins of the Monroe Doctrine". Economica. doi:10.2307/2547870. JSTOR 2547870.

- ↑ Ferrell, Robert H. "Monroe Doctrine". ap.grolier.com.

- ↑ Lerner, Adrienne Wilmoth (2004). "Monroe Doctrine". Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security.