« The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 180 : | Ligne 180 : | ||

[[Image:Central Park 1862.jpg|left|220px|thumb|Central Park during its construction.Photograph by Victor Prevost, 1862.]] | [[Image:Central Park 1862.jpg|left|220px|thumb|Central Park during its construction.Photograph by Victor Prevost, 1862.]] | ||

In 1860, the | In 1860, the wealthiest 5% of American families controlled more than half of the country's wealth. This trend has continued and has become a global issue as today, 2% of the world's population owns 50% of the wealth, while half of the world's population owns only 1% of the wealth. This highlights the persistent problem of income and wealth inequality which has been present for centuries and still ongoing. | ||

In cities like New York | In cities like New York during the mid-19th century, the extreme poverty and wealth gap led to violence and riots against the poorest and most vulnerable groups such as Irish and black people. This led to a political shift as the Irish population, in particular, began to vote overwhelmingly for the Democratic party as a reaction to the Republican party's policies. This period also marked the beginning of the Kennedy dynasty, as the Kennedy's became one of the most prominent Irish-American political families. The Kennedy dynasty is one of the most prominent political families in the United States history, known for their influence in American politics for more than a century. The Kennedy family has produced several prominent political figures, including President John F. Kennedy, who served as the 35th President of the United States and was assassinated in 1963, Robert F. Kennedy who served as Attorney General and was assassinated in 1968 while running for President, and Ted Kennedy who served as a long-time senator from Massachusetts. The Kennedy's are known for their liberal and progressive political views, and many of their political campaigns centered on issues such as civil rights, poverty and social justice. They have a strong legacy in American politics and still have an influence on the current political scene.<ref>Maier, Thomas (2003). [https://archive.org/details/kennedysamericas00maie_0 The Kennedys: America's Emerald Kings]. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04317-0.</ref><ref>[https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family The Kennedy Family]. The JFK Library</ref> | ||

Free African-Americans are the other major victims of this era, as they are accused of saturating the labour market, driving down wages and are targeted in urban riots; segregation and racism also dominate in the North. This is a paradox, because as the number of states in the Union increases, a greater proportion of states have democratised male suffrage, but at the same time a greater proportion of states exclude blacks from voting because of their race. | Free African-Americans are the other major victims of this era, as they are accused of saturating the labour market, driving down wages and are targeted in urban riots; segregation and racism also dominate in the North. This is a paradox, because as the number of states in the Union increases, a greater proportion of states have democratised male suffrage, but at the same time a greater proportion of states exclude blacks from voting because of their race. | ||

Version du 23 janvier 2023 à 12:53

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

In 1850, the northern states of the United States were primarily composed of immigrants from Europe, while the southern states were heavily dependent on the labor of enslaved African Americans. This economic and cultural divide between the North and South would eventually lead to the American Civil War. Additionally, the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it a federal crime to assist an escaped slave, further exacerbating tensions between the North and South.

In addition to the demographic and economic differences between the North and South, there were also significant political differences. The North was generally more industrialized and focused on economic growth, while the South was primarily agrarian and focused on protecting the institution of slavery. The Northern states were also more inclined to support abolition and were generally more supportive of federal government intervention in economic and social issues, while the Southern states were more inclined to support states' rights and were generally more resistant to federal government intervention. This political divide would also contribute to the eventual outbreak of the Civil War.

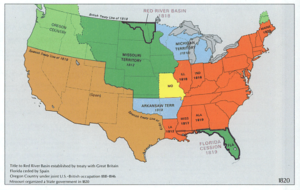

Territorial expansion

Forcible displacement of Amerindians

During the period between 1820 and 1850, the United States government pursued a policy of forced displacement of Native American tribes, also known as Indian Removal. This policy was implemented through a series of treaties and laws, including the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which authorized the President to negotiate treaties to remove tribes from their ancestral lands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River. This policy, implemented from 1831 to 1838, resulted in the forced relocation of thousands of Native Americans, including the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations, in what became known as the "Trail of Tears." The displacement was forced, many native Americans were killed in the process and it also led to the destruction of buffalo, which were a main source of food for the native Americans.

Andrew Jackson, the 7th President of the United States, passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 as part of his broader policy of Indian removal. He believed that the presence of Native American tribes in the southeastern United States was an obstacle to the economic development and expansion of white settlement in the region. He also held a belief in the concept of "manifest destiny," which held that it was the destiny of white Americans to expand and settle the entire continent. He believed that by removing the Native American tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River, white settlers would have access to more land and resources, and that this would lead to greater economic growth and prosperity.

The balance between slave states and free states

In the 1850s, the balance between slave states and free states in the United States was a major political issue. The expansion of the country from west to east and south, as new territories were added and new states were formed, threatened to upset this balance. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had been established to maintain a balance between slave and non-slave states in the Senate, with Maine being admitted as a free state to balance the admission of Missouri as a slave state. However, with the discovery of gold in California and the subsequent rush of settlers to the area, the issue of whether California would be admitted as a free or a slave state became a major point of contention and ultimately led to the passage of the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise of 1850 included a number of measures aimed at maintaining the balance between slave and non-slave states and avoiding a civil war, including the admission of California as a free state, the establishment of the territories of New Mexico and Utah, and the passage of a stricter Fugitive Slave Law.

The Texas Declaration of Independence was adopted on March 2, 1836, by the Convention of 1836 at Washington-on-the-Brazos, Texas. It declared the independence of the Republic of Texas from Mexico and listed a number of grievances against the Mexican government. The full text is as follows:

"When a government has ceased to protect the lives, liberty and property of the people, from whom its legitimate powers are derived, and for the advancement of whose happiness it was instituted, and so far from being a guarantee for the enjoyment of those inestimable and inalienable rights, becomes an instrument in the hands of evil rulers for their oppression.

When the Federal Constitution of the country, which they have sworn to support, no longer has a substantial existence, and the whole nature of their government has been forcibly changed, without their consent, from a restricted federation of sovereign states, united for specific national purposes, into an consolidated central military despotism, in which every interest is disregarded but that of the army and the priesthood, both the eternal enemies of civil liberty, the ever ready minions of power, and the usual instruments of tyrants.

When, long after the spirit of the constitution has departed, moderation is at length so far lost by those in power, that even the semblance of freedom is removed, and the forms themselves of the constitution discontinued, and so far from their petitions and remonstrances being regarded, the agents who bear them are thrown into dungeons, and mercenary armies sent forth to force a new government upon them at the point of the bayonet.

When, in such a crisis, the differing opinions of political parties are forgotten, and the line of demarcation is drawn between the oppressor and the oppressed, it is the right and duty of the latter to rise in rebellion against the former, and to bear the arms they have been forced to assume, in defense of their persons, property and rights, which they pledge their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to maintain."

The expansion against Mexico and the question of balance between slave and non-slave states was a major issue in the early 19th century, particularly in Texas. The large number of Anglo-American settlers in Texas, many of whom brought their slaves with them, put pressure on the Mexican government to maintain the institution of slavery despite the fact that it had been abolished in Mexico in 1829. This led to tensions between the settlers and the Mexican authorities, and in 1835-1836, a war broke out between the Texan settlers and the Mexican army. In 1836, the Texan settlers declared their independence from Mexico, forming the Republic of Texas. The Republic of Texas officially abolished slavery in 1829 but it was still widely practiced. Texas was annexed to the United States in 1845, which increased the number of slave states in the country and further exacerbated tensions over the issue of slavery.[8] The U.S. Congress recognized the independence of the Republic of Texas on March 3, 1845. This was a significant step towards the eventual annexation of Texas to the United States which happened on December 29 of the same year. The annexation of Texas was a contentious issue in the United States, as it increased the number of slave states in the country and further inflamed tensions over the issue of slavery. The annexation of Texas was seen as a victory for pro-slavery interests in the United States, and it was a major factor in the growing sectional divide between the North and the South that ultimately led to the Civil War.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

During the same period, in Oregon, there was strong pressure to settle and displace the Native Americans still living there. White settlers, mainly Americans and Canadians, moved into the area and implemented policies that threatened the rights and lands of the indigenous tribes. There was also an ongoing debate on the issue of slavery in the region. Northern settlers, who were overwhelmingly against slavery, succeeded in having Oregon declared a slave-free territory in 1848. However, this also led to growing tension between the Northern and Southern states over the expansion of slavery into the new American territories.

The issue of the expansion of slavery into new territories and the balance of power between slave and non-slave states was a contentious issue in the United States in the 1840s. The states of the slave-owning South were particularly concerned about the potential for the expansion of non-slave states in the West, and they reacted strongly to the growing abolitionist sentiment in the North. In the 1844 presidential election, the Democrats nominated James K. Polk, a pro-slavery, expansionist candidate from Tennessee, and he was elected as the 11th President of the United States. His presidency was marked by the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War, which resulted in the acquisition of large territories in the West, including California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. This increased the number of slave states and further inflamed tensions over the issue of slavery, ultimately leading to the Civil War.[16][17]

Under the presidency of James K. Polk, Florida and Texas were annexed to the United States as states. Polk's presidency was also marked by the Mexican-American War, which began in 1846. The United States declared war on Mexico after a dispute over the border between Texas and Mexico, and the annexation of Texas by the United States. The war was controversial, particularly in the northern states, where many opposed it as an aggressive and unjustified expansion of slavery. Polk campaigned on a platform of "Manifest Destiny", which called for the expansion of American territory, and the war was seen as a way to acquire new territories in the West, including California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma, which would ultimately increase the number of slave states.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

The Mexican-American War, which lasted from 1846 to 1848, resulted in a significant expansion of American territory. As a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, Mexico ceded California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma to the United States in return for the payment of $15 million. This acquisition of new territories in the West, known as the Mexican Cession, was a major factor in the growing sectional divide between the North and the South over the issue of slavery.

Following the war, the discovery of gold in California in 1848 led to the California Gold Rush, which brought thousands of people, including Chinese immigrants, to the West Coast. Many Chinese immigrants came to California to mine for gold and to work in other industries, and they played a significant role in the development of the West Coast during the 19th century.[26][27]

During the expansion and colonization of the American West, there were many conflicts between European settlers and the indigenous peoples of the region, including the forced displacement, enslavement and massacre of Native Americans. The annexation of Oregon in 1846 and the discovery of gold in California in 1848 led to an influx of settlers in the region, and this led to increasing tensions and violence between settlers and Native Americans. Many tribes were forced to give up their land and move to reservations, and their populations were decimated by disease, violence, and forced labor.

The conquest of the West also raised many ethical and moral questions about the treatment of indigenous peoples and the expansion of American territory. The actions of settlers and the US government in the West were often in violation of treaties and agreements made with Native American tribes, and the forced displacement and extermination of native peoples has had a lasting impact on their communities and cultures.

The two-party system in the United States did evolve over time. In 1828, the Democratic-Republican Party, which had been led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, split into two separate parties: the Democratic Party and the National Republican Party, which later became the Whig Party. The Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, represented the interests of small farmers and western settlers, while the National Republican Party and later the Whig Party, represented the interests of the northeastern industrial and commercial elite.

In the 1820s and 1830s, the question of slavery and its expansion into new territories became an increasingly divisive issue in American politics. The Democratic Party, which had its base of support in the South, largely supported the expansion of slavery, while the Whig Party, which had its base of support in the North, opposed it.

The Whig Party dissolved in 1854, and its members joined the newly formed Republican Party which was formed by abolitionist and anti-slavery groups and advocated for the restriction of slavery in the territories. The Republican Party became more and more vocal about its opposition to slavery, and it gained support among the northern industrial and commercial elite, as well as among the emerging abolitionist movement. The Democratic party, on the other hand, became more and more associated with the slave-owning interests in the South.

I the early years of the Republic racism and xenophobia were not absent and the treatment of Irish immigrants was not good, but the party system and its evolution was not only driven by those factors.

During the 19th century, both major parties in the United States, the Democrats and the Republicans, supported the expansion and colonization of the American West. The idea of manifest destiny, the belief that it was the nation's destiny to expand its territory and spread its way of life, was a popular and influential concept among American politicians, businessmen, and settlers during this time. Both parties saw the expansion into the West as an opportunity for economic growth and territorial expansion.

However, their views on slavery and the treatment of indigenous peoples were different. The Democratic Party, which had its base of support in the South, supported the expansion of slavery, and the party's elected officials often advocated for pro-slavery policies. On the other hand, the Republican Party, which had its base of support in the North, opposed the expansion of slavery, and it was associated with the abolitionist movement.

In general, both parties supported the idea of American expansion into the West, but their views on slavery, the treatment of indigenous peoples and territorial expansion had significant differences which ultimately led to the American civil war.[28][29]

Thesis of the Manifest Destiny of the United States (1845)

The thesis of the Manifest Destiny of the United States, as articulated by John L. O'Sullivan in 1845, was that it was the divinely ordained mission of the United States to expand its territory and influence across the North American continent, and eventually the entire world. The idea was that the principles of democracy and freedom embodied by the United States made it a superior civilization, and it was the duty of the nation to spread these principles to the rest of the world. This idea would become a key justification for U.S. imperialism and territorial expansion in the following decades.[30][31][32]

It was believed that the Anglo-Saxon race and culture of the United States were superior to other cultures and that it was the duty of the nation to spread its power and population to the rest of the world. This idea was used to justify territorial expansion and the annexation of land from other countries and native peoples. The belief was that this expansion was a divine right and will, which was to be accomplished by the "superior" American society.[33][34] The thesis of Manifest Destiny as articulated by John L. O'Sullivan and others in the mid-19th century had a racist dimension, as it was based on the belief in the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race and culture. This belief was used to justify the subjugation and displacement of indigenous peoples, the annexation of land from Mexico and other countries, and the forced removal and displacement of enslaved African Americans. The belief in the divine right of the United States to expand its territory and influence was often coupled with the idea that non-white races were inferior and therefore, should be either subdued or eliminated to make way for the expansion of the white population. The idea of Manifest Destiny was used as a justification for aggressive and violent expansionism, and the displacement of indigenous and other people of color.

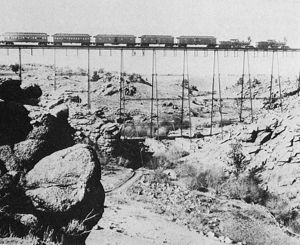

After the annexation of the Mexican territories, including California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma, in the 1840s, there was a shift in the focus of U.S. expansionism. While the idea of Manifest Destiny did not officially end, it was no longer used as a justification for territorial expansion through military conquest and annexation. Instead, the focus shifted towards economic expansion, such as the building of railroads and the settlement of the western territories through the Homestead Act of 1862. The idea of manifest destiny was also used as a justification for the forced removal and displacement of indigenous peoples, as well as the expansion of American influence and power in other parts of the world, such as Asia and Latin America. The belief in the divine right and duty of the United States to spread its power and influence remained a significant aspect of American foreign policy throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

After the annexation of Mexican territories, the idea of Manifest Destiny evolved into a broader policy of American domination, both domestically and internationally. This included economic, financial, and military domination of other countries and regions, particularly in the Caribbean and Latin America. The United States began to use its economic and military power to exert influence over other countries, often through the use of force, intervention, and the imposition of puppet governments. This policy of domination was justified as a means of spreading American values and interests, and protecting American economic and strategic interests. This type of domination was called "informal empire" as it was done without the need of formal annexation. This policy can be seen in the various interventions of the United States in the Caribbean, Central and South America throughout the late 19th and early 20th century and the United States continued to exert its influence around the world, particularly in the aftermath of World War II through the Cold War, where the United States sought to expand its influence and contain the spread of communism.

The idea of Manifest Destiny, as articulated in the mid-19th century, did begin to fade in the latter part of the century, as the focus of American expansionism shifted from territorial conquest to economic expansion. The War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain, in which the United States was not able to achieve its expansionist goals, and the subsequent Treaty of Ghent that ended the war, marked the end of American expansion to the north. However, the belief in the divine right and duty of the United States to spread its power and influence remained a significant aspect of American foreign policy throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The idea of Manifest Destiny was still used as a justification for the forced removal and displacement of indigenous peoples, as well as the expansion of American influence and power in other parts of the world, such as Asia and Latin America. It is important to note that the fading of the Manifest destiny idea as an official doctrine, did not mean the end of American expansionism and imperialism, but rather a shift in the ways of achieving it.

1850: Fragile Compromise between Slave and Free States

In 1850, the United States was in a delicate balance between slave states in the south and free states in the north. This compromise was made to keep the balance of power between the two regions, but it was a fragile one. At the same time, new territories were being acquired through the Mexican-American War and the annexation of California, which further complicated the issue of slavery and statehood.

The issue in 1850 was how to balance the number of slave states and free states as new territories were being added to the United States. If there were more slave states than free states, then the slave states would have a majority in the Senate and could potentially pass laws to expand slavery to the new territories. Conversely, if there were more free states than slave states, the free states would have the majority in the Senate and could pass laws to abolish slavery in the new territories. This issue was at the center of the debate over the Compromise of 1850, which aimed to find a solution to this problem by admitting California as a free state, creating the territories of New Mexico and Utah where the question of slavery would be decided by popular sovereignty, and strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Compromise of 1850 was a series of laws passed by the U.S. Congress that attempted to ease tensions between the northern and southern states over the issue of slavery in newly acquired territories. The compromise admitted California as a free state, created the territories of New Mexico and Utah where the question of slavery would be decided by popular sovereignty, and strengthened the Fugitive Slave Act. However, the Compromise of 1850 did not settle the issue of slavery and it continued to be a contentious issue in American politics. The question of slavery in the territories was a major point of contention in the lead-up to the Civil War and ultimately led to the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1861, whose anti-slavery stance further inflamed tensions between the North and South and ultimately led to the outbreak of the Civil War.[35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

The North: market revolution and immigration

The market revolution

The market revolution in the North during the mid-19th century led to significant economic and social changes. The introduction of new technologies and transportation systems, such as railroads and steam-powered factories, allowed for increased production and the growth of industry. This led to the rise of a market economy and a shift from a primarily agrarian society to an industrialized one. The North also experienced a significant influx of immigrants during this time, primarily from Ireland and Germany, which further contributed to the growth of industry and the expansion of cities.

The market revolution in the North during the mid-19th century led to significant economic and social changes. The introduction of new technologies and transportation systems, such as railroads and steam-powered factories, allowed for increased production and the growth of industry. This led to the rise of a market economy and a shift from a primarily agrarian society to an industrialized one. Additionally, the North experienced a significant influx of immigrants during this time, which further contributed to the growth of industry and the expansion of cities. In contrast, the southern economy remained primarily agrarian and focused on the production of cash crops such as cotton and tobacco, and reliance on the labor of enslaved African Americans. This economic and social divide between the North and South would eventually contribute to the outbreak of the Civil War..

The market revolution in the United States during the mid-19th century was characterized by the rapid development of transportation infrastructure, including the construction of railroads and canals, which facilitated the movement of goods and people across the country. This allowed for increased economic integration and the growth of a national market, connecting the North, South, East and West of the country. This transportation infrastructure not only enabled the export of goods from the North to other parts of the country, but also facilitated the movement of people, ideas and culture, contributing to the formation of a more unified national identity. Additionally, the development of transportation infrastructure allowed for the expansion of industry and the growth of urban centers, further contributing to the economic and social changes of the market revolution.

Commercialization refers to the process of increasing economic activity and the use of money in transactions, rather than relying on barter or self-sufficiency. This shift often leads to a greater dependence on market systems, and can result in the erosion of traditional community and familial structures. Prior to this, many settler communities in the United States had existed on the fringes of the larger economy, relying on subsistence farming and limited trade.

Industrialization refers to the process of development of industry on an extensive scale, characterized by the use of machinery and the application of the assembly-line method of mass production. It also typically involves the shift from manual labor to machine-based production, and the use of interchangeable parts that can be mass-produced in order to be used in a variety of products. This increased efficiency and productivity, but also led to changes in the labor force, as well as the way goods were produced and consumed.

Industrialization is marked by the construction of large-scale industrial facilities, where mass production takes place. This process often leads to significant social changes, such as the rise in the percentage of wage-earners in the labor force. During the period of industrialization in the United States, the percentage of wage-earners in the total labor force rose from around 10% in 1800 to around 40% in 1860. This change was due to the growth of factory jobs and the shift away from agricultural work. Along with this, there was also an urbanization movement, as people were moving to urban areas to work in the factories, leading to the formation of new cities and towns.

During the period of industrialization in the United States, the northeastern region became heavily industrialized and the majority of the population worked as wage earners. This marked a significant departure from the founding myth of the United States as a nation of free and self-sufficient peasant settlers. Many of the people working in the factories were women and young girls, who worked in the textile industries before getting married. These women were able to contribute to the family income by working, allowing them to buy goods and improve their standard of living. This also had a significant impact on the role of women in the society and economy. Additionally, the rise of wage-earning and urbanization also led to the change in social structure and lifestyle.

Many factory workers, both men and women, worked long hours during the day and often put in additional hours at night. Some women also worked from home, under contract with factories, performing tasks such as sewing clothes with Singer machines. They were often paid very low wages for this work. This had a significant impact on the economy of families, as women's work in these factories and home contracts allowed them to earn additional income and contribute to the family's finances. This also changed the traditional gender roles, as women were increasingly participating in the workforce and taking on responsibilities outside of the home. This also led to an increase in the production of goods and services, leading to an economic growth.

The profession of schoolteacher did develop during the period of industrialization in the United States, as the growth of the public school system created a need for more teachers. The development of public schools was more compatible with the ideal of motherhood that was promoted by the dominant bourgeois ideology of the time. This ideal emphasized the role of women as caretakers and educators of children, and the teaching profession was seen as a suitable and respectable career for women. This led to an increase in the number of women entering the teaching profession, and the expansion of the public school system helped to promote education and literacy among the population.

During this period, the working class faced significant exploitation, with many working long hours for low wages under difficult conditions. The means of struggle available to them were often limited, and not very effective in addressing their grievances. This was partly due to the abundance of workers, which created a surplus of labor, making it difficult for workers to organize and negotiate for better conditions. Additionally, the working class was often divided by ethnicity, race, and gender, which made it harder for them to unite and collectively demand for better rights. The situation was different from that of Latin America, where the causes of the limitations of the struggle of the working class could have been different.

Immigration

The United States experienced a demographic explosion in the mid-19th century due to high rates of reproduction among the existing population and a large influx of immigrants. The population of the U.S. increased sixfold between 1800 and 1860, growing from 5.3 million to 31.5 million during that time period.

Many immigrants came to the United States in the mid-19th century as a result of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the economic changes brought about by industrialization. Many people fled Europe seeking better economic opportunities and to escape extreme poverty, as well as the destruction of traditional agricultural way of life and the decline of small peasantry. This immigration wave was a major contributor to the demographic explosion in the United States during this time period.[42] 1848 was a significant year in European history, often referred to as the "Year of Revolutions" or the "Spring of Nations". It was a time of political upheaval and social unrest across Europe, with various countries experiencing significant protests and uprisings. The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, which denounced the exploitation of workers and called for a revolution to overthrow the capitalist system, was also published in 1848. Additionally, many immigrants to the United States in this time period were fleeing from political and religious persecution, as well as from famines. All of these factors contributed to the large number of immigrants who came to the United States in the mid-19th century, which in turn contributed to the country's demographic explosion.

The mid-19th century was also a time of great hardship for the Irish, due to the potato famine that occurred between 1845 and 1849. The potato blight, a disease that destroyed the potato crop, led to widespread starvation and death, with an estimated 1 million Irish people dying as a result. Many Irish people were forced to emigrate in search of food and work, and as a result, a significant number of Irish immigrants came to the United States during this time period. The Irish immigrants constitute a large proportion of the immigrants to the United States between 1830 and 1860, estimated to be around 45%. This Irish immigration wave also contributed to the demographic explosion in the United States during this time period.

Many immigrants in the mid-19th century settled in the rural Midwest, where there was land available for farming and opportunities for work in agriculture. Germans and Scandinavians were among the groups that settled in the Midwest during this time period. Other immigrants, particularly those who were very poor and had little or no agricultural experience, tended to remain in the port cities where they had landed, such as New York and Boston. At the time, these cities had large immigrant populations: it is estimated that around half of the inhabitants of New York were immigrants, while in Boston immigrants made up a third of the population. These immigrants were concentrated in the urban areas, which helped fuel the growth of these cities.

In addition to the immigration of Europeans, there was also significant migration of black people from the South to the North in the mid-19th century. This migration was primarily made up of free blacks who were leaving the South due to increasing racial discrimination and the expansion of slavery. A small number of enslaved people also escaped to the North via the Underground Railroad, which was a secret network of safe houses and routes established by abolitionists, particularly Quakers, to help fugitive slaves reach freedom. Many of these refugees settled in northern cities, such as Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. The migration of blacks from the South to the North, along with the immigration of Europeans, contributed to the demographic explosion in the United States during the mid-19th century.[43][44][45][46][47]

The gap between rich and poor

the gap between rich and poor was widening in the United States during the mid-19th century. The rapid industrialization and economic growth of the country during this time period led to the rise of a new industrial capitalist class, which amassed great wealth through their control of the country's factories and businesses. At the same time, many workers, particularly immigrants and other marginalized groups, were paid low wages and subjected to poor working conditions. This led to a growing divide between the wealthy and the working class, with a small number of individuals and families controlling a large portion of the country's wealth and resources, while a large number of people struggled to make ends meet. This gap between rich and poor is a persistent problem in the United States and many other countries, and continues to be an important issue today. The widening gap between the rich and poor in the United States during the mid-19th century was characterized by the formation of an aristocracy of financiers and multimillionaires, largely composed of families from the elite merchant class that existed during the colonial period, such as the Roosevelt and Whitney families, while the poor crowded into urban slums. During the mid-19th century, the Roosevelt and Whitney families were among the wealthy elite merchant class in the United States. The Roosevelt family, for example, made their fortune in shipping and importing, while the Whitney family amassed wealth through their control of the cotton trade. They both were very influential in the American politics and economy, and they were among the families that control a large portion of the country's wealth and resources, while many people struggled to make ends meet in the slums of the cities. [48][49][50][51] It was at this time that New York's Central Park was built serving as a recreational space but primarily intended for the wealthy class, serving as a symbol of their status and privilege, while the working class and poor were mostly excluded from accessing it.

- Theodore Roosevelt and family, 1903.jpg

Family of Theodore Roosevelt (1903).

- TheKennedyFamily1.jpg

The Kennedy family in the summer of 1931.

In 1860, the wealthiest 5% of American families controlled more than half of the country's wealth. This trend has continued and has become a global issue as today, 2% of the world's population owns 50% of the wealth, while half of the world's population owns only 1% of the wealth. This highlights the persistent problem of income and wealth inequality which has been present for centuries and still ongoing.

In cities like New York during the mid-19th century, the extreme poverty and wealth gap led to violence and riots against the poorest and most vulnerable groups such as Irish and black people. This led to a political shift as the Irish population, in particular, began to vote overwhelmingly for the Democratic party as a reaction to the Republican party's policies. This period also marked the beginning of the Kennedy dynasty, as the Kennedy's became one of the most prominent Irish-American political families. The Kennedy dynasty is one of the most prominent political families in the United States history, known for their influence in American politics for more than a century. The Kennedy family has produced several prominent political figures, including President John F. Kennedy, who served as the 35th President of the United States and was assassinated in 1963, Robert F. Kennedy who served as Attorney General and was assassinated in 1968 while running for President, and Ted Kennedy who served as a long-time senator from Massachusetts. The Kennedy's are known for their liberal and progressive political views, and many of their political campaigns centered on issues such as civil rights, poverty and social justice. They have a strong legacy in American politics and still have an influence on the current political scene.[52][53]

Free African-Americans are the other major victims of this era, as they are accused of saturating the labour market, driving down wages and are targeted in urban riots; segregation and racism also dominate in the North. This is a paradox, because as the number of states in the Union increases, a greater proportion of states have democratised male suffrage, but at the same time a greater proportion of states exclude blacks from voting because of their race.

In 1850 only Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine granted equality to blacks. In Massachusetts, blacks could testify, in California they could not testify against whites, in all northern states they were segregated or excluded from certain public places as well as from almost all skilled and industrial jobs and labor associations.

Blacks are forced to live in ghettos and, like the Irish, to create their own institutions and accept much lower-paying jobs. Despite all this, the number of blacks in the North is increasing considerably, especially in Philadelphia, New York and Cincinnati, even though they represent only 2% of the total population.

The South: black slavery and white privilege

In the southern United States, the years from 1800 to 1860 were years of great growth and prosperity for some. During this period, the southern United States experienced significant economic growth through the expansion of cotton farming and the slave trade. Cotton was one of the main crops of the south and was widely exported to Europe and other parts of the world. New lands were conquered and populated by free people and slaves.

Cotton King

This is the era of the Cotton King because the textile industry in England and the northern United States is booming, and the demand for cotton continues to grow.

With the invention of the cotton ginning machine, production increased and became more and more technical as cotton-producing land expanded along with the number of slaves.

In 1800, cotton accounted for only 7% of US exports, in 1820 32% and in 1850 58%. This shows the enormous weight the Southern states have in national politics and economy. At the same time, the number of slaves multiplied: 460,000 in 1770 in the thirteen colonies, 1.5 million in 1820 and more than 4 million in 1860. The import of slaves remained illegal after the prohibition in 1808.

The main explanation is natural growth, as living conditions are better and slaves live in family huts. All these slaves will reach the huge figure of 4 million on the eve of the Civil War, of which 2 million work in the cotton plantations.

Once again we see the archaic and modern modes of production side by side. The slaves live in rudimentary conditions, but it is a very organized production, on the other hand, it is a period when the slave merchants function very well.

At the same time, the society will evolve between free whites and black slaves. Free African-Americans are at most 17% in Delaware, in the other states they are less than 1%. It is a dichotomous society where slaves do huge jobs such as plantation work, sugar, rice, indigo, domestic work, mining, transportation construction, industry and lumber.

The gap between rich and poor whites

Between 1820 and 1850, society in the South did not change much compared to the North, even though the gap between rich and poor widened. The South continued to be rural and dominated by slavery. Almost all African Americans were slaves, and it was the slaves who provided the permanent skilled and unskilled labor force for the benefit of all whites.

Among whites, only 1.5% own more than 5 slaves, 64% do not, but still enjoy them. Among those who do not own slaves, there are some very poor whites who benefit indirectly from slavery because the worst work is always done by slaves. The little white children who often provide the basic food for the large slave planters are often paid in return by the loan of slaves to do the worst or hardest work; there are loaned slaves.

At a deeper level, there continues to be a belief in the ideal of freedom and autonomy of the independent peasant embodied by the Democratic Party. In the South, the freedom of white people depends on the permanence of slavery.

In order to understand the war of secession, it is necessary to understand that even the poorest white people live in a society where they see the continuous humiliation in which the slaves live as a reflection of their own freedom and their privileged situation.[54][55][56]

Deep down, when we live with miserable people, we have the illusion of being free and superior with the privilege of white skin that makes the richest planters equal to the richest, reinforced by fundamentally racist legislation. In the South slaves are not only excluded and most black Americans as well as free African-Americans are excluded from the rights of the poorest. This reinforces the consciousness of being part of an aristocracy, it is the extreme rigidity of the separation between blacks and whites that allows the poorest whites to believe in the privilege of white skin even as the gap between rich and poor among whites widens. It is thanks to this belief that the great planters of the South will be able to mobilize whites behind the Democratic Party to defend slavery in the Civil War.

Annexes

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ Nacional, Defensa. “2 De Marzo De 1836, Texas Declara Su Independencia.” Gob.mx, www.gob.mx/sedena/documentos/2-de-marzo-de-1836-texas-declara-su-independencia.

- ↑ Barker, Nancy N. (July 1967). "The Republic of Texas: A French View". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 71.

- ↑ Calore, Paul (2014). The Texas Revolution and the U.S.–Mexican War A Concise History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7940-5.

- ↑ Edmondson, J.R. (2000). The Alamo Story: From Early History to Current Conflicts. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-55622-678-0.

- ↑ Hardin, Stephen L. (1994). Texian Iliad – A Military History of the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73086-1. OCLC 29704011.

- ↑ Vazquez, Josefina Zoraida (July 1985). translated by Jésus F. de la Teja. "The Texas Question in Mexican Politics, 1836–1845". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 89.

- ↑ Weber, David J. (1992). The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale Western Americana Series. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05198-0.

- ↑ Winders, Richard Bruce (2004). Sacrificed at the Alamo: Tragedy and Triumph in the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: State House Press. ISBN 1-880510-81-2.

- ↑ Morrison, Michael A. "Martin Van Buren, the Democracy, and the Partisan Politics of Texas Annexation". Journal of Southern History 61.4 (1995): 695–724. ISSN 0022-4642. Discusses the election of 1844. online edition.

- ↑ Polk, James K. The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845–1849 edited by Milo Milton Quaife, 4 vols. 1910. Abridged version by Allan Nevins. 1929, online.

- ↑ Smith, Justin Harvey. The War with Mexico, Vol 1. Vol 2. (2 vol 1919).

- ↑ Ortega Blake, Arturo. Frontera de papel, tres hermanos en la Guerra México-Estados Unidos. México: Grijalbo, Random House Mondadori, 2004. ISBN 970-05-1734-9.

- ↑ John S.D. Eisenhower. "So Far from God: The U.S. War with Mexico, 1846-1848". UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA PRESS Norman, 1989.

- ↑ Crawford, Mark; Heidler, Jeanne; Heidler (eds.), David Stephen (1999). Encyclopedia of the Mexican War. ISBN 978-1-57607-059-8.

- ↑ Bauer, Karl Jack (1992). The Mexican War: 1846–1848. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6107-5.

- ↑ Guardino, Peter. The Dead March: A History of the Mexican-American War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (2017). ISBN 978-0-674-97234-6

- ↑ Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2008)

- ↑ Meed, Douglas. The Mexican War, 1846–1848 (2003). A short survey.

- ↑ Ralph K. Andrist (2015). The Gold Rush. New Word City. p. 29.

- ↑ "Gold rush". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008

- ↑ Billington, Ray Allen, and Martin Ridge. Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier (5th ed. 2001)

- ↑ Billington, Ray Allen. The Far Western frontier, 1830–1860 (1962), Wide-ranging scholarly survey; online free

- ↑ "Annexation": The July–August 1845 editorial in which the phrase "Manifest Destiny" first appeared

- ↑ Johannsen, Robert W. "The Meaning of Manifest Destiny", in Sam W. Hayes and Christopher Morris, eds., Manifest Destiny and Empire: American Antebellum Expansionism. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-89096-756-3.

- ↑ Sampson, Robert D. John L. O'Sullivan and His Times. (Kent State University Press, 2003) online

- ↑ « C’est notre destinée manifeste de nous déployer sur le continent confié par la Providence pour le libre développement de notre grandissante multitude. » (« It is our manifest destiny to overspread the continent alloted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions »

- ↑ Howard Zinn, Une Histoire populaire des États-Unis, 1980, Trad.fr. Agone 2002, p.177

- ↑ Compromise of 1850

- ↑ Compromise of 1850 and related resources from the Library of Congress

- ↑ Texas Library and Archive Commission Page on 1850 Boundary Act

- ↑ Map of North America at the time of the Compromise of 1850 at omniatlas.com

- ↑ Hamilton, Holman (1954). "Democratic Senate Leadership and the Compromise of 1850". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 41 (3): 403–18. doi:10.2307/1897490. ISSN 0161-391X. JSTOR 1897490.

- ↑ Russel, Robert R. (1956). "What Was the Compromise of 1850?". The Journal of Southern History. Southern Historical Association. 22 (3): 292–309. doi:10.2307/2954547. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2954547.

- ↑ Waugh, John C. On the Brink of Civil War: The Compromise of 1850 and How It Changed the Course of American History (2003)

- ↑ Childs, Frances Sergeant. French Refugee Life in the United States: 1790-1800, an American Chapter of the French Revolution. Philadelphia: Porcupine, 1978. Print.

- ↑ Blackett, R.J.M. (2013). Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Curtis, Anna L. (1941). Stories of the Underground Railroad. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. (Stories about Thomas Garrett, a famous agent on the Underground Railroad)

- ↑ Frost, Karolyn Smardz (2007). I've Got a Home in Glory Land: A Lost Tale of the Underground Railroad. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ↑ Larson, Kate Clifford (2004). Bound For the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-45627-0.

- ↑ Still, William (1872). The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-Breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom, As Related by Themselves and Others, or Witnessed by the Author. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. (Classic book documenting the Underground Railroad operations in Philadelphia).

- ↑ Collier, Peter; David Horowitz (1994). The Roosevelts: An American Saga. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-65225-7.

- ↑ Schriftgiesser, Karl (1942). The Amazing Roosevelt Family, 1613–1942. Wildred Funk, Inc.

- ↑ William Richard Cutter. Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of Boston and Eastern Massachusetts, Volume 3 (Boston: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1908) pp. 1400–1401. https://books.google.com/books?id=qaK9Vz1UdDcC

- ↑ "Racing Proud of Whitney Heritage: Three Generations of Family Prominent on American Scene; Among Founders of Jockey Club, Campaigned Abroad; Owned Two Derby Winners". Daily Racing Form at University of Kentucky Archives. 1956-05-05.

- ↑ Maier, Thomas (2003). The Kennedys: America's Emerald Kings. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04317-0.

- ↑ The Kennedy Family. The JFK Library

- ↑ Frank Lawrence Owsley, "The Confederacy and King Cotton: A Study in Economic Coercion," North Carolina Historical Review 6#4 (1929), pp. 371–397 in JSTOR

- ↑ Frank Lawrence Owsley. King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign relations of the Confederate States of America (1931).

- ↑ Ashworth, John (2008). Slavery, capitalism, and politics in the antebellum Republic. 2. p. 656.