The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

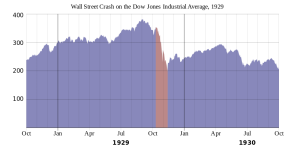

The 1920s, glittering with prosperity and lulled by carefree optimism, are often referred to as the 'Roaring Twenties'. This period illustrates a flourishing America, where abundance and success seemed to be the norm. However, this era of opulence and euphoria came to an abrupt end with the stock market crash of October 1929, opening the door to the grim Great Depression. This economic catastrophe, the most devastating in American history, transformed a once prosperous country into a nation reeling from massive unemployment, widespread poverty and financial instability.

The Great Depression not only shook the economy; it trampled the soul and spirit of the American people. Millions lost not only their jobs but also their faith in a prosperous future. Businesses and banks went bankrupt, leaving behind them a trail of desolation and helplessness. Farmers, the backbone of the economy, have been dispossessed of their land, adding to the sense of despair.

The crisis has sown doubt and uncertainty in the minds of Americans, once optimistic and confident in their prosperous nation. A deep distrust of the economic system and government has sprung up, radically changing the national psyche. However, in this abyss of despair, the innovative policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal emerged like a beam of light. Bold reforms and a government now more involved in the economy began a healing process, laying new foundations for a gradual recovery.

The Great Depression not only reconfigured American politics, catalysing the shift in power from the Republicans to the Democrats, but also prompted a profound re-examination of the relationship between the citizen and the state. The Democratic Party, once associated with the South and Catholic immigrants, has become the champion of the working and middle classes, which have been hardest hit by the crisis. The American political landscape was redefined, and with it an era of renewal and social transformation emerged.

This monumental upheaval spawned a blossoming of social movements, a reassessment of cultural values and a redefinition of national identity. The Great Depression left an indelible scar on American history, a sombre reminder of human vulnerability to the unpredictable forces of the economy. Yet it also illustrated the nation's resilience and innovation, highlighting America's undeniable ability to reinvent itself in the midst of the most devastating trials.

The causes of the 1929 stock market crash[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The stock market crash of 1929 was not simply the result of economic instability in Europe or the inability of European nations to repay the loans they had taken out with American banks after the First World War. Rather, it was the consequence of a combination of economic, financial and political factors, each contributing to a collapse of devastating proportions. Unbridled stock market speculation was commonplace in the 1920s. Unrealistic optimism led many investors to place huge sums of money in the stock market, often on credit. This led to artificial inflation in share prices and the formation of a vulnerable financial bubble. Margin buying, or the excessive use of credit to buy shares, made the situation worse. When confidence collapsed, many investors found themselves unable to repay their loans, exacerbating the crisis. The lack of robust financial regulation allowed risky and unethical practices, making the stock market and banks unstable. In addition, panic and the rush to sell amplified the market collapse. An unprecedented volume of share sales precipitated a vertiginous fall in prices. Beyond the dynamics of the stock market, the US economy was suffering from deep-seated problems. Wealth inequalities, industrial and agricultural overproduction and a decline in consumption all contributed to a fragile economic base. Banks, having invested heavily in the stock market or lent money to investors to buy shares, were hit hard when share values plummeted. Their failure exacerbated the crisis of confidence and further reduced access to credit. Instability in Europe and the inability of European countries to repay their debts also played a role in the crisis. The interconnection of the world's economies turned a national crisis into an international disaster. These factors converged to create an environment where a large-scale economic collapse was inevitable. This toxic mix of unregulated speculation, easy credit, underlying economic instability and panic selling was exacerbated by international economic instability. This highlighted the imperative need for greater regulation and oversight of the stock market and banking system, leading to substantial reforms in the years that followed to prevent a recurrence of such disasters.

This dichotomy between the international and domestic factors that led to the stock market crash of 1929 is at the heart of debates about the origins of the Great Depression. International economic tensions, notably European debt, cannot be overlooked. However, close inspection reveals that fundamental economic dynamics in the United States also played a critical role. The Second Industrial Revolution, characterised by considerable technological advancement and industrial expansion, instilled a sense of economic invincibility and apparent prosperity during the 'Roaring Twenties'. This period saw the emergence of new industries, increased productivity and widespread financial euphoria. However, this economic effervescence concealed a vulnerable financial landscape, undermined by excessive speculative practices and a dangerous accumulation of debt. The prosperity of the 1920s was not as solid as it seemed. It was fuelled in part by easy access to credit and unbridled stock market speculation. Many investors, blinded by enthusiasm and optimism, were unaware of the risks inherent in a market saturated with speculative capital. The euphoria masked the underlying economic fragility and encouraged unsustainable optimism. The sharp fall came when economic reality caught up with speculation. Investors became aware of the latent instability and financial insecurity. The stock market crash that followed was inevitable, not because of external pressures, but rather because of unresolved internal flaws in the US economy. In this context, European debt and international instability were merely aggravating factors, not the root causes of the crisis. The very foundations of American prosperity were unstable, hollowed out by imprudent financial practices and a lack of adequate regulation. The Great Depression that followed was not only a brutal market correction but also a rude awakening for a nation that had been lulled into economic complacency for too long. It signalled the imperative need for a balance between innovation, growth and financial prudence, laying the foundations for a new economic order in the United States.

This debt-fuelled investment frenzy and unbridled optimism was a key element that precipitated the stock market crash of 1929. Market dynamics at the time were characterised by a collective euphoria in which caution took a back seat to blind confidence in a perpetual economic upswing. The idea that the market could rise indefinitely was ingrained in the minds of many investors. Their investment strategy, often devoid of prudence, was heavily geared towards buying shares on margin. This speculative approach, while lucrative in the short term, was inherently vulnerable, making the economy extremely susceptible to market fluctuations. Share prices had reached stratospheric heights, fuelled not by solid economic fundamentals but by unbridled speculation. This dislocation between the real and perceived value of shares created an unsustainable financial bubble. Every bubble, no matter how big or small, is bound to burst sooner or later. The bubble of 1929 was no different. When reality set in again, and investor confidence collapsed, the stock market was plunged into chaos. Investors, including those who had bought on margin and were already deeply in debt, rushed to sell, triggering a rapid and relentless downward spiral in share prices. The massive rush to dump equities exacerbated the crisis, turning a market correction that was perhaps inevitable into an economic catastrophe of staggering proportions. The consequences were felt far beyond Wall Street, permeating every nook and cranny of the US and global economy. This financial disaster was not the product of a single factor, but the result of a toxic combination of unregulated speculation, easy credit and complacency, a perfect storm that triggered one of the darkest periods in modern economic history. The lesson of the crash was clear: a market left to its own devices, without careful regulation and proper oversight, is liable to descend into excesses that can have devastating consequences for everyone.

The meteoric rise of the car and household appliance industries in the 1920s is a classic example of the double-edged sword of rapid industrial growth. Although these innovations marked an era of apparent prosperity, they also sowed the seeds of the impending economic crisis. Industrial production had reached historic highs, but this growth was not matched by equivalent demand. The American economic machine, with its overloaded production capacity, began to creak, generating a surplus of goods that far exceeded consumers' purchasing capacity. The spectre of overproduction, where factories were producing at a rate that outstripped consumption, became a worrying reality. The flourishing car and household appliance industries became victims of their own success. The domestic market was saturated; every American household that could afford a new car or appliance already had one. The imbalance between supply and demand set off a chain reaction, with falling consumption leading to reduced production, rising unsold stocks and falling profits for companies. This economic slowdown was a worrying omen in an already volatile financial landscape. The stock market, which had long been a source of prosperity, was ripe for a correction. Shares were overvalued, a product of speculation rather than the intrinsic value of companies. When business confidence faltered, a domino effect was triggered. Investors, nervous and uncertain, withdrew their capital, sending the market into a downward spiral. So the stock market crash of 1929 was not an isolated event, but the result of a series of interconnected factors. Industrial overproduction, market saturation, overvalued equities and a loss of business confidence converged to create a precarious economic environment. When the crash came, it was not just a financial correction, but a brutal reassessment of the foundations on which the prosperity of the 1920s had been built. Prudence and regulation became watchwords in discussions of the economy, ushering in an era in which rapid growth would be tempered by recognition of its potential limits and the dangers of excess.

The rise of consumer credit was a defining feature of the American economy in the 1920s, an era of rapid but reckless expansion. Citizens, lured by the promise of immediate prosperity, went into debt to enjoy a standard of living beyond their immediate means. Easy access to credit not only stimulated consumption but also engendered a culture of indebtedness. This easy access to credit has, however, concealed deep cracks in the country's economic foundations. Consumer spending, while high, was artificially inflated by debt. Individuals and families, seduced by the apparent abundance and easy access to credit, accumulated considerable debt. This dynamic created an economy which, although apparently prosperous on the surface, was intrinsically fragile, with stability dependent on consumers' ability to manage and repay their debts. When the optimism of the Roaring Twenties gave way to the reality of a declining economy, the fragility of this expansive credit system became apparent. Consumers, already heavily in debt and now faced with an uncertain economic outlook, cut back on their spending. Unable to repay their debts, a vicious circle of defaults and consumer recession set in, exacerbating the economic slowdown. This abrupt reversal revealed the inadequacy of an economy based on debt and speculation. The collapse of confidence and the contraction of credit were triggers for a crisis that swept through not only the United States but also the global economy. Individuals, companies and even nations found themselves trapped in a spiral of debt and default, ushering in an era of recession and readjustment. This scenario highlighted the need for careful and considered credit and debt management. The economic euphoria fuelled by easy credit and excessive consumption proved unsustainable. In the ashes of the Great Depression, a new approach to economics and finance began to emerge, one that recognised the dangers inherent in unregulated prosperity and sought a more sustainable balance between growth and financial stability.

The low interest rate regime that prevailed in the 1920s played a significant role in setting the stage for the stock market crash of 1929. Increased access to credit, facilitated by low interest rates, encouraged both consumers and investors to take on debt. In a climate where cheap money was readily available, financial prudence often took a back seat to excessive enthusiasm and confidence in the economy's upward trajectory. Cheap money not only fuelled consumption but also encouraged intense speculation on the stock market. Investors, armed with easily obtained credit, flocked to an already overvalued market, pushing share prices well beyond their intrinsic value. This dynamic created an overheated financial environment, where real value and speculation were dangerously misaligned. The correction came in the form of higher interest rates. This increase, while necessary to cool an overheated economy, came as a shock to investors and borrowers. Faced with higher borrowing costs and a growing debt burden, many were forced to liquidate their positions on the stock market. This scramble for the exit led to a massive sell-off, triggering a rapid and uncontrolled fall in share prices. The inversion of interest rates revealed the fragility of an economy built on the shifting sands of cheap credit and speculation. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed were dramatic manifestations of the limits and dangers of unregulated economic growth overly dependent on debt. The lesson learned was painful but necessary. In the years following the crisis, greater attention was paid to the prudent management of monetary policy and interest rates, recognising their central role in stabilising the economy and preventing speculative excesses that could lead to economic disaster. The disaster of 1929 prompted a profound reassessment of the principles and practices underpinning economic management, underlining the need for a balance between the imperatives of growth and the imperatives of financial stability and security.

The lack of robust regulation was a crucial weakness that exacerbated the severity of the 1929 stock market crash. At the time, the stock market was largely unregulated territory, a kind of financial 'wild west' where government oversight and investor protections were minimal or non-existent. This facilitated an environment of unbridled speculation, market manipulation and insider trading. The lack of transparency and ethics in stock market operations has created a highly volatile and uncertain market. Investors, lacking reliable and accurate information, were often in the dark, forced to navigate a market where asymmetric information and manipulation were commonplace. Trust, an essential ingredient of any healthy financial system, was eroded, replaced by uncertainty and speculation. In this context, fraud and insider trading proliferated, exacerbating the risks for ordinary investors who were often ill-equipped to understand or mitigate the dangers inherent in the market. Their vulnerability was exacerbated by the absence of regulatory protections, leaving many investors at the mercy of a capricious and often manipulated market. When the crash occurred, these structural and regulatory weaknesses were brutally exposed. Investors, already faced with a precipitous fall in stock market values, were left with no recourse in the face of an inadequate regulatory and protection infrastructure. The catastrophe of 1929 was a wake-up call for government and regulators. In its wake, an era of regulatory reform was ushered in, characterised by the introduction of stricter oversight mechanisms and protections for investors. Legislation such as the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 in the United States laid the foundations for a more transparent, fair and stable stock market. The harsh lesson of the stock market crash revealed the crucial importance of regulation and supervision in maintaining the integrity and stability of financial markets. It initiated a profound transformation in the way financial markets were perceived and managed, marking the beginning of an era in which regulation and investor protection became central pillars of financial stability.

Economic inequality was an underlying, and often overlooked, weak link in the economic fabric of the United States on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash. The growing gap between the rich and the working class was not simply a question of social justice, but also a factor of profound economic vulnerability. In the boom years of the 1920s, a narrative of unprecedented prosperity and growth prevailed. However, this prosperity was not evenly distributed. While wealth and luxury were ostensibly on display in the upper echelons of society, a significant portion of the American population lived in precarious economic conditions. The working class, although fundamental to industrial production and growth, was a marginal beneficiary of the wealth generated. This disproportion in the distribution of wealth instilled tensions and fissures within the economy. Consumption, a vital engine of economic growth, was undermined by the inadequacy of real wages for the majority of workers. Their ability to participate fully in the consumer economy was limited, creating a dynamic where overproduction and debt became increasingly prevalent. In this context, consumer confidence was fragile. Working class families, faced with rising living costs and stagnant wages, were vulnerable to economic shocks. When signs of an impending recession appeared, their ability to absorb and overcome the impact was limited. Their withdrawal from consumption exacerbated the economic slowdown, turning a moderate recession into a deep depression. The revelation of this wealth inequality had profound implications for economic and social policy. Gaps in the distribution of wealth were not simply social inequities, but economic flaws that could amplify boom and bust cycles. Recognition of the importance of economic justice, wage stability and worker protection became central to political and economic responses in the years following the Great Depression, shaping an era of reform and recovery.

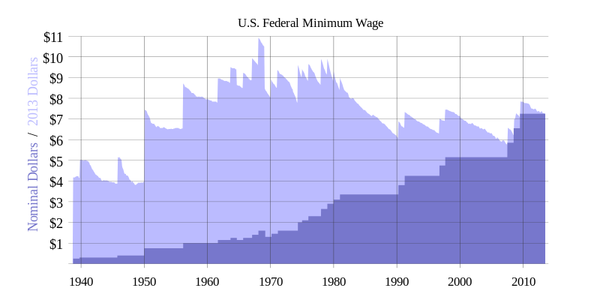

The concentration of wealth in the hands of a narrow elite was not only a contributing factor to the crash of 1929, but also exacerbated the severity of the Great Depression that followed. Much of the nation's wealth was held by a small fraction of the population, creating a disparity that weakened the economic resilience of society as a whole. In an economy where consumption is a key driver of growth, the ability of the masses to purchase goods and services is crucial. The stagnation of real wages among workers and the middle class has reduced their purchasing power, leading to a contraction in demand. This reduction in demand has, in turn, affected production. Faced with falling sales, companies cut production and laid off workers, creating a vicious cycle of unemployment and falling consumption. The working and middle classes, deprived of sufficient financial resources, were unable to drive economic recovery. The ability of businesses to invest and expand was also hampered by the contraction in market demand. The profits and dividends accumulated by the wealthiest were not sufficient to stimulate the economy, as they were often not ploughed back into the economy in the form of consumption or productive investment. This highlighted a critical realisation: a fair distribution of wealth was not just a matter of social justice, but also an economic imperative. For an economy to be healthy and resilient, the benefits of growth must be widely shared to ensure robust demand and support production and employment. The response to the Great Depression, notably through the policies of the New Deal, reflected this realisation. Initiatives were launched to increase workers' purchasing power, regulate financial markets and invest in public infrastructure to create jobs. This marked a transition to a more inclusive vision of economic prosperity, where the distribution of wealth and opportunity was seen as a central pillar of economic stability and growth.

The Great Depression significantly reoriented the United States' approach to economic and social policy. The economic catastrophe exposed deep structural weaknesses and inequalities that had previously been largely ignored or underestimated. The need for proactive state intervention to stabilise the economy, protect the most vulnerable citizens and reduce inequalities became clear. The advent of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal marked a turning point in the American perspective on the role of government. While the dominant ideology prior to the Great Depression favoured laissez-faire and minimal government intervention, the crisis called this approach into question. It was clear that leaving it to the market alone was not enough to guarantee stability, prosperity and fairness. The New Deal, with its three-pronged strategy of relief, recovery and reform, was a multi-dimensional response to the crisis. Relief meant direct and immediate assistance for the millions of Americans facing poverty, unemployment and hunger. It was not only a humanitarian measure but also a strategy to revitalise consumer demand and stimulate the economy. The recovery focused on revitalising key sectors of the economy. Through massive public works projects and other initiatives, the government sought to create jobs, increase purchasing power and initiate an upward spiral of growth and confidence. Every dollar spent on building infrastructure or on wages was passed on to the economy, boosting consumption and investment. Reform, however, was perhaps the most enduring aspect of the New Deal. It was about structurally transforming the economy to prevent a repetition of the mistakes that had led to the Great Depression. This included tighter regulation of the financial sector, guaranteed bank deposits and policies to reduce economic inequality. In this way, the Great Depression and the response of the New Deal redefined the American social and economic contract. They highlighted the need for a balance between market freedom and government intervention, economic growth and equity, individual prosperity and collective well-being. This transformation shaped the trajectory of American politics and economics for decades to come.

- GDP depression.png

The general evolution of the depression in the United States, as reflected by GDP per capita (average income per person) in constant 2000 dollars, as well as some of the key events of the period.[8]

The mismatch between output growth and wage stagnation was one of the key factors that amplified the severity of the Great Depression. A thriving economy depends not only on innovation and production, but also on strong and sustainable demand, which requires a balanced distribution of income. If, in the 1920s, particular attention had been paid to the fair remuneration of workers and to ensuring that productivity gains were translated into higher wages, the country might have been better prepared to withstand a recession. Workers and families would have had more financial resources to maintain their spending, which could have cushioned the impact of the economic contraction. In other words, an economy whose prosperity is widely shared is more resilient. It can absorb economic shocks better than one where wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few. Consumer demand, fuelled by decent wages and a fair distribution of income, can sustain businesses and employment through difficult times. The premise is that every worker is not only a producer but also a consumer. If workers are well paid, they consume more, fuelling demand, which in turn supports production and employment. It's an economic ecosystem where production and consumption are in harmony. The crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression provided valuable lessons on the importance of this balance. The reforms and policies that followed have sought to restore and maintain this balance, although the challenge of economic inequality and pay equity remains a contemporary issue, reiterating the relevance of the lessons learned from that tumultuous period in economic history.

Price adjustment can be an effective mechanism for balancing supply and demand, especially in a context where consumer purchasing power is limited. A reduction in prices could, in theory, have stimulated consumption, thereby improving business liquidity and supporting the economy. In the context of the 1920s, the combination of increased production and stagnant wages created an imbalance where supply exceeded demand. More goods were being produced than the market could absorb, largely because consumers' purchasing power was limited by insufficient wages. By reducing prices, companies could have made their products more accessible, thereby stimulating demand and reducing the build-up of unsold inventories. However, it should be noted that this strategy also has its challenges. Reducing prices can erode companies' profit margins, potentially putting them in difficulty, especially if they are already vulnerable due to other economic factors. In addition, a generalised price cut, or deflation, can have perverse economic effects, such as encouraging consumers to delay purchases in the expectation of even lower prices, thereby exacerbating the economic slowdown. So, while reducing prices may be a viable strategy for increasing demand in the short term, it needs to be approached with caution and in the context of a wider economic strategy. It may be more beneficial to combine this approach with initiatives to increase consumer purchasing power, for example, by raising wages or introducing favourable tax policies, to create an environment where production and consumption are in dynamic equilibrium.

The climate at the time was characterised by excessive optimism, an unshakeable faith in the perpetual growth of the market and a reluctance to intervene in free market mechanisms. The Republican administrations of the time, rooted in laissez-faire principles, were reluctant to interfere in economic affairs. The prevailing philosophy was that markets would regulate themselves and that government intervention could do more harm than good. This ideology, while effective during economic booms, proved insufficient to prevent or mitigate the looming crisis. Similarly, many business and industrial leaders were trapped in a short-term vision, focused on maximising immediate profits rather than long-term sustainability. The euphoria of the economic boom often obscured the warning signs and underlying imbalances that were building up. The combination of overconfidence, inadequate regulation and a lack of corrective measures created a breeding ground for a crisis of devastating proportions. The crash of 1929 was not just an isolated event, but the result of years of accumulating economic and financial imbalances. The lesson learned from this tragic period was the recognition of the need for prudent regulation, a long-term view and preparation for economic instability. The policies and institutions that have emerged from the Great Depression, including greater regulatory oversight and a more active role for government in the economy, reflect an awareness of the complexity of economic systems and the need to balance growth, stability and equity.

The agricultural sector, although less glamorous than the booming stock markets and rapidly expanding industries, was a fundamental pillar of the economy and society. The First World War had led to a dramatic increase in demand for agricultural products, boosting production and prices. However, by the end of the war, global demand had contracted, but production remained high, leading to oversupply and falling prices. Farmers, many of them already operating on slim margins, found themselves in an increasingly precarious financial position. Mechanisation of agriculture also played a role, increasing production but also reducing demand for labour, contributing to the rural exodus. Farmers and rural workers migrated to cities in search of better opportunities, fuelling rapid urbanisation but also contributing to the saturation of the urban labour market. These rural dynamics were precursors and amplifiers of the Great Depression. When the stock market crash hit and the urban economy contracted, the agricultural sector, already weakened, was unable to act as a counterweight. Rural poverty and distress intensified, widening the scope and depth of the economic crisis. The recovery of the agricultural sector and the stabilisation of rural communities became essential elements of the recovery effort. New Deal initiatives such as farm legislation to stabilise prices, efforts to balance production with demand and investment in rural infrastructure were crucial components of the overall strategy to revitalise the economy and build a more resilient and balanced system.

The fallout from agricultural decline has not been confined to rural areas, but has affected the economy as a whole, creating a domino effect. The contraction of the agricultural sector has reduced not only farmers' incomes, but also those of businesses dependent on rural areas. Suppliers of agricultural materials and equipment, retailers and even the banks that had lent to farmers - all were affected. This contraction in rural demand has reduced incomes and employment in a variety of sectors, spreading economic distress far beyond farms and farming communities. Farmers' indebtedness, exacerbated by falling prices for agricultural products, has led to loan defaults and land seizures, affecting the stability of rural and urban financial institutions. Banks, already weakened by other factors, have been put under greater pressure. This cascading effect highlights the integrated and interdependent nature of the economy. Problems in one sector reverberate through others, creating a downward spiral that can be difficult to halt and reverse. In the context of the Great Depression, the decline of the agricultural sector was both a symptom and a catalyst for the wider economic collapse. Political and economic responses to the crisis had, of necessity, to take account of this complexity and interdependence. Intervention to stabilise and revitalise the agricultural sector was an integral part of the overall effort to restore the nation's economic health. Efforts to raise the price of agricultural products, support farmers' incomes and improve rural stability were intrinsically linked to restoring confidence, stimulating demand and achieving general economic recovery.

The distress of the rural population was a major catalyst for the reforms introduced under the New Deal. Farmers were among the hardest hit during the Great Depression. The combination of overproduction, falling crop prices, mounting debt and adverse weather conditions, such as those seen during the Dust Bowl, led to economic and social disaster in rural areas. The New Deal, initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, introduced a series of programmes and policies aimed specifically at alleviating distress in the agricultural sector. Measures such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act were implemented to raise agricultural commodity prices by controlling production. By paying farmers to reduce production, the government hoped to raise prices and improve farmers' incomes. Other initiatives, such as the creation of the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act, were put in place to provide loans to farmers threatened with foreclosure. This has helped to stabilise the agricultural sector, allowing farmers to keep their land and continue producing. In addition, the implementation of public works projects not only created jobs but also helped to improve rural infrastructure, connecting rural areas to urban markets and improving market access for agricultural products. These government interventions were unprecedented at the time and marked a radical change in the federal government's role in the economy. The New Deal not only brought immediate relief but also laid the foundations for structural reforms to prevent such an economic catastrophe from happening again in the future. It emphasised the importance of balancing the agricultural and industrial sectors and strengthened the role of the state as a regulator and stabiliser of the economy.

The inability of the Republican administrations of the time to effectively address the agricultural crisis had a marked effect on the country's demographic and economic dynamics. Laissez-faire economic policies largely ignored the growing distress in rural areas. Overproduction and the consequent fall in agricultural prices have plunged farmers into financial precariousness. Without adequate support and faced with debt and bankruptcy, many have been forced to leave their land. This situation has not only exacerbated economic distress in rural areas, but has also fuelled migration to the cities. Urban areas, although promising in terms of economic opportunities, have been swamped by an influx of workers seeking employment and economic security. This rapid migration has strained urban resources, exacerbating the challenges associated with providing housing, services and jobs. The urban labour market, already affected by the economic contraction, became saturated, contributing to rising unemployment and poverty. Against this backdrop, the Great Depression revealed and exacerbated the underlying structural weaknesses of the US economy and politics. It highlighted the imperative need for more dynamic government action and balanced attention to all sectors of the economy. The response in the form of the New Deal marked a turning point, not only in terms of specific policies but also in the perception of the role of government in the economy. The need for government intervention to stabilise the economy, regulate markets and support citizens in distress became an accepted part of American economic policy, shaping the political and economic landscape for decades to come.

The trend towards rapid urbanisation and the simultaneous weakening of the agricultural sector created a series of complex challenges that exacerbated the economic problems of the time. As the rural population declined, so did the demand for goods and services in these areas. Local businesses, dependent on demand from farmers and rural workers, suffered, leading to a spiral of economic decline. What's more, the influx of rural workers into the cities coincided with the stock market crash and the resulting economic contraction, increasing competition for already scarce jobs. Urban infrastructure, social services and housing markets were ill-prepared to handle such a rapid increase in population. This put additional pressure on urban resources and exacerbated problems of poverty and unemployment. The decline of the agricultural sector also had an impact on industry and financial services. Businesses that depended on agricultural demand, whether for agricultural machinery, chemicals or financial services, have also been affected. The growing indebtedness of farmers and payment defaults have affected the health of banks and financial institutions. The overall economic situation has been aggravated by a combination of factors, including reduced demand for agricultural products, indebtedness, the bankruptcy of rural businesses, and a growing urban population without adequate jobs. All these factors contributed to the depth and duration of the Great Depression. Roosevelt's New Deal subsequently attempted to tackle these interconnected problems through a series of programmes and reforms aimed at stabilising the economy, providing direct relief to those who suffered most, and reforming the economic and financial systems to prevent a repetition of such disasters in the future. The complexity and interdependence of the economic and social challenges of the time highlighted the need for coordinated, multi-faceted government action.

The problems of the agricultural sector, exacerbated by overproduction, falling prices and indebtedness, were largely neglected. This inaction, combined with the stock market crash of 1929, highlighted the inadequacies of the laissez-faire economic approach adopted at the time. The agricultural sector was a vital part of the American economy, and its deterioration had repercussions far beyond rural areas. Farmers, already financially weakened, were powerless to cope with the economic turmoil caused by the Great Depression. Reduced domestic demand, shrinking export markets and an inability to access credit exacerbated the crisis. The advent of the Roosevelt administration and the implementation of the New Deal marked a radical shift in government policy. For the first time, the federal government took significant steps to intervene in the economy, signalling a departure from the laissez-faire philosophy. Measures such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act were introduced to increase the price of agricultural products by reducing overproduction. Low-interest loans and subsidies were provided to help farmers keep their land and stay in business. In addition, public works projects were launched to create jobs and stimulate economic activity. So while initial inaction in the face of the agricultural and financial crises exacerbated the impacts of the Great Depression, subsequent New Deal interventions helped to alleviate some of the worst suffering, stabilise the economy and lay the foundations for lasting recovery and reform. These initiatives also redefined the role of the federal government in managing the economy and protecting the welfare of its citizens, a legacy that continues to influence American policy to this day.

The crash of 1929 and its consequences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The 1920s, often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties", were characterised by apparent prosperity and rapid economic growth. However, this growth was, to a large extent, unsustainable, as it was based on a massive expansion of credit and unbridled speculation. Easy credit and low interest rates encouraged a culture of spending and investment that exceeded the real means of consumers and investors. People were encouraged to live beyond their means, and overconfidence in continued growth fuelled a dangerous speculative bubble. The stock market became the centre of a speculative fever. Millions of Americans, from the richest to the poorest, invested their savings in the hope of quick gains. The belief that share prices would continue to rise indefinitely was a mirage that attracted people from all walks of life. However, the underlying economic reality did not support market euphoria. When confidence began to erode and the bubble burst, the market's rapid reversal triggered a panic. Investors sought to liquidate their positions, but with few buyers, share prices fell dramatically. This stock market crash had a domino effect, triggering a severe economic contraction. Consumer and investor confidence was severely shaken, leading to a reduction in spending and investment. Banks, also affected by the crisis and the ensuing panic, restricted credit, further exacerbating the recession. The Great Depression that followed was a moment of profound re-evaluation of the structure and regulation of the American economy. It underlined the dangers of unregulated speculation and excessive reliance on credit, and highlighted the need for a healthier balance between consumption, investment and sustainable economic growth. It has also paved the way for tighter government regulation to mitigate the risks and excesses that can lead to such crises.

The stock market craze and credit expansion masked deep structural weaknesses in the US economy. Overproduction, in particular, was a major problem not only in the industrial sector, where production outstripped demand, but also in the agricultural sector. Farmers, already struggling with low prices and falling incomes, were hit hard, exacerbating rural decline and economic misery. The unequal distribution of wealth was also a critical factor. A small elite enjoyed growing prosperity while the majority of Americans saw no significant improvement in their standard of living. This dynamic reduced aggregate demand, as a large proportion of the population could not afford to buy the goods that were being produced in abundance. When the speculative bubble in the stock market burst, these underlying weaknesses became apparent. Panic quickly set in, investors and consumers lost confidence in economic stability, and the country entered a downward spiral of economic contraction, rising unemployment and bankruptcies. The government's response and the introduction of the New Deal underlined the need for more robust government intervention to correct market imbalances and vulnerabilities. The programmes implemented sought not only to provide immediate relief, but also to initiate structural reforms aimed at building a more solid and equitable basis for future economic growth. This period marked a significant transformation in the conception and application of economic policy in the United States.

The stock market crash of 1929 was not an isolated event, but rather the most visible and immediate manifestation of a series of structural and systemic problems that had become entrenched in the US economy. Unbridled speculation, encouraged by easy access to credit and low interest rates, created an environment where thoughtful and prudent investment was often neglected in favour of quick profits. This focus on short-term profits not only fuelled the stock market bubble, but also diverted capital away from productive investments that could have supported sustainable economic growth. In addition, the lack of adequate regulation and government oversight left the market without effective safeguards against speculative excesses and risky financial practices. By failing to intervene actively, the government indirectly allowed unsustainable economic bubbles to form. When the stock market bubble burst, the underlying fragility of the economy was revealed. Banks and financial institutions were hit hard, and as credit tightened, businesses and consumers found themselves in a liquidity crunch. Confidence collapsed, and with it consumption and investment. The Great Depression called for a profound reconsideration of economic policies and a shift to greater government intervention to stabilise the economy, protect consumers and investors, and lay the foundations for more balanced and sustainable future growth. The lessons of that era continue to resonate in contemporary debates on economic regulation, the management of speculative bubbles and the role of government in promoting equitable and sustainable growth.

This crash was not just a temporary economic correction, but a catastrophic collapse that had profound and lasting repercussions for the global economy.

The rapid and severe decline in share values caught many investors off guard. The euphoria of the 'Roaring Twenties', when the market was booming and wealth seemed to be growing endlessly, quickly turned to despair and panic. Investors large and small saw the value of their portfolios plummet, eroding not only their personal assets but also their confidence in the financial system. The panic quickly spread beyond Wall Street. Banks, already weakened by bad loans and speculative investments, were hit by waves of panic withdrawals. Some were unable to cope with the sudden demand for liquidity and were forced to close their doors. This deepened the crisis, spreading mistrust and uncertainty throughout the economic system. The rapid loss of market value, combined with panic and investor withdrawal, marked the beginning of the Great Depression. The effects were felt far beyond the stock market, affecting businesses, workers and consumers across the country and, ultimately, the world. The financial collapse led to economic contraction, massive unemployment, corporate bankruptcies and widespread poverty and misery. The stock market crash prompted a thorough reappraisal of the financial system and its regulatory mechanisms. It provided a stark illustration of the dangers inherent in an unregulated and speculative market, and led to major reforms to strengthen the transparency, accountability and stability of the financial system, with the aim of preventing such a catastrophe from happening again in the future.

The collapse of banks and credit companies has been devastating. The banking system, in particular, is a pillar of the modern economy, facilitating the credit and investment necessary for economic growth. Its failure has exacerbated economic problems. The closure of banks has meant that many people and businesses have lost their savings and access to credit. In a world where credit is essential for everything from the day-to-day management of personal finances to the running and expansion of businesses, this collapse had far-reaching repercussions. Businesses were forced to scale back operations or close, leading to a rapid rise in unemployment. Uncertainty and fear led to a dramatic contraction in consumer spending. People, worried about their financial future, avoided unnecessary spending, contributing to a vicious circle of reduced demand, output and employment. This self-fulfilling recession was characterised by a reduction in demand, which in turn led to a reduction in production and even higher unemployment. The crisis also highlighted the fragility of the monetary and financial system and the importance of confidence in economic stability. Restoring this confidence has proved to be a long and difficult process, requiring in-depth reform and significant government intervention to stabilise the economy, reform the financial and banking system, and introduce safeguards to prevent future crises. This economic cataclysm ushered in an era of transformation, ushering in new and innovative economic policies, and redefining the relationship between government, the economy and citizens, with a renewed focus on regulation, social protection and economic equity.

The crash was a defining moment in the history of the Great Depression. It was not a short-lived crisis, but the prelude to an era of deep and persistent economic difficulties that affected almost every aspect of daily life. The breadth and depth of the Great Depression were unprecedented. The stock market crash exposed and exacerbated existing cracks in the economic fabric of the United States. Unemployment reached unprecedented levels, businesses failed at an alarming rate, and an atmosphere of despair and pessimism enveloped the nation. Every sector, from industry to agriculture, was affected, and images of queues of people waiting for food became striking symbols of the times. The stock market crash and subsequent Great Depression also led to a profound re-examination of economic and financial policies. The limitations and failures of laissez-faire and hands-off approaches were exposed. In response, there was a move towards greater regulation, government supervision and measures to increase transparency and financial stability. Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, for example, was not just a set of measures to respond to the immediate economic crisis, but also a revolution in the way government interacted with the economy. It introduced policies and institutions that continue to influence American economic policy to this day.

The Great Depression had a quantifiably catastrophic impact on the US economy, as some alarming figures show. Between 1929 and 1932, the United States' Gross National Product (GNP) fell drastically, by more than 40%. This monumental economic recession was amplified by a 50% drop in industrial production, a sector that had once flourished in the country. At the same time, the agricultural sector, the backbone of the US economy, was not left out. It contracted substantially, with falling output closely mirroring that of industry. These simultaneous declines in key sectors created a downward spiral in economic activity. Unemployment, a clear indicator of economic health, soared alarmingly. In 1929, around 1.5 million Americans were unemployed. By 1932, however, this figure had jumped to 12 million, signalling an unprecedented jobs crisis that transformed the economic and social landscape. Large-scale job loss led to a significant reduction in income for millions of households. The direct consequences of this loss of income have been rising homelessness, increased prevalence of hunger and escalating poverty. People's ability to access basic needs such as food, housing and healthcare was severely compromised, highlighting the depth of the unfolding economic crisis.

The economic distress did not spare rural areas, where the drastic fall in agricultural prices plunged farmers into a downward financial spiral. To quantify this, let's imagine a 50% drop in agricultural prices. This would mean that farmers' incomes, and by extension their purchasing power, would be severely affected. The domino effect of this fall in prices would be tangible. A significant decline in the rural population occurred as farmers, faced with reduced incomes, were forced to abandon their land. Imagine a 30% reduction in the rural population, reflecting the severity of migration to urban centres. This exodus from the countryside to the cities has led to a contraction in agricultural production. If we were to quantify this decline, we could envisage a 40% reduction in agricultural production, exacerbating the fall in prices due to a persistent oversupply. The rural economy was in a downward spiral. Falling prices and a shrinking population led to falling production. This toxic combination not only exacerbated poverty and distress in rural areas but also contributed to the saturation of cities with surplus labour, exacerbating already high unemployment rates.

The Great Depression, characterised by a catastrophic deterioration in economic conditions, resulted in immeasurable human suffering. If we were to put figures on this crisis, we might consider that the unemployment rate soared to an alarming 25%, meaning that one in four Americans of working age found themselves without a job. Food insecurity was rampant. Perhaps as much as a third of the American population was affected, facing malnutrition and hunger in the absence of a stable income. Poverty rates reached unprecedented heights, with millions of people, perhaps as many as 40% of the population, living below the poverty line. Against this backdrop, the New Deal was introduced to bring immediate relief. Millions of jobs were created through various programmes - to illustrate, the Civilian Conservation Corps employed some 2.5 million single young men in conservation and natural resource development work. However, despite these considerable efforts, the economic recession dragged on. It took almost a decade, until the mid-1940s, for the US economy to begin to show signs of robust recovery, where the unemployment rate returned to a more manageable figure, and rates of poverty and food insecurity began to fall. This period underlines the scale of the economic and humanitarian devastation and the need for coordinated and meaningful government intervention to facilitate recovery and ensure the well-being of citizens in times of crisis.

The economic decline, represented by an estimated 30% fall in consumer spending, illustrated the collapse in consumer confidence and purchasing power. The unemployment rate, which reached a staggering peak of 25%, highlighted the extent of people's inability to find work and, consequently, to earn an income. This reduction in income created a vicious circle where reduced consumption led to reduced demand for goods and services. In terms of figures, imagine a 40% fall in industrial production, illustrating a drastic reduction in demand. Financial distress seeped into every household, where average incomes fell by perhaps 50%, making it difficult for millions of Americans to access basic needs. In fact, up to a third of Americans were unable to meet basic needs such as food and housing. The human cost of this crisis was enormous. Food banks and shelters were overwhelmed, and perhaps 20% of the population struggled to provide a daily meal for their families. The number of homeless people increased exponentially, with thousands of "tent cities" emerging across the country. These alarming statistics paint a bleak picture of America during the Great Depression, highlighting the deep economic and human distress that required massive and decisive government intervention to reverse the course of economic and social deterioration.

The Great Depression shattered the financial and social foundations of the American middle class. Imagine that 50% of middle-class households saw their financial security collapse, losing not only jobs but also their savings. The loss of homes was alarming; at one point nearly 1,000 homes were foreclosed every day, leaving families homeless and desperate. Property, a pillar of financial security, evaporated for millions, with an estimated 25% increase in homelessness. Confidence in the government under President Herbert Hoover was at an all-time low. The slow and inadequate response to the crisis left around 60% of the American population feeling neglected, without support or relief from growing poverty and uncertainty. Middle-class families, once prosperous, have seen their standard of living fall drastically. Real wages may have fallen by 40%, and discretionary spending became a luxury. One in four Americans was unemployed, and economic misery permeated every aspect of daily life. These figures provide a tangible perspective on the scale of the devastation that the Great Depression inflicted on the American middle class, and underline the powerlessness felt by many in response to governance that was perceived as ineffective and insensitive to the deep distress of the people.

The emergence of the 'Hoovervilles' marked a low point in the Great Depression, underlining the scale of the human and economic misery that had befallen the country. It's no exaggeration to say that thousands of these makeshift settlements sprang up in cities across America, housing entire families who had lost everything. The numbers behind these communities tell a story of desperation. Each "Hooverville" could have hundreds or even thousands of residents. In New York City, a particularly large "Hooverville" emerged in Central Park, where hundreds of people lived in makeshift shelters. Life in these communities was precarious. With little or no access to adequate sanitation, disease spread easily. Malnutrition rates were high, with perhaps as many as 75% of residents suffering from a lack of adequate food, and life expectancy in these camps was significantly reduced. The emergence of the "Hoovervilles" was a visible sign of the government's failure to respond effectively to the crisis. The plight of the residents, over 90% of whom were unemployed and had lost all means of support, became a powerful symbol of the country's economic and social deterioration. These figures offer a glimpse into the immensity of the human crisis during the Great Depression, highlighting the devastating impact of unemployment, poverty and government failure in responding to the deteriorating living conditions of ordinary Americans.

The residents of the Hoovervilles represented a mix of those hardest hit by the Great Depression. For example, 60% may have been immigrants or African-Americans, reflecting the discrimination and inequality exacerbated by the economic crisis. In these makeshift communities, the unemployment rate among people of colour and immigrants was around 50% higher than the national average. Limited access to support and work opportunities amplified their economic vulnerability. Each Hooverville had its own self-help system. Almost 80% of residents depended on charity, donations of food and clothing, or occasional work to survive. Self-sufficiency was a necessity, with exceptionally high rates of dependency on community services and charity. The psychological impact was also profound. For many, life in the Hoovervilles represented a drastic decline in living standards, with perhaps 70% of residents having previously lived in middle-class conditions. Shame and humiliation were omnipresent, as each family and individual struggled to maintain dignity in overwhelming circumstances. These figures paint a moving picture of life in the Hoovervilles and highlight the inequality and distress that characterised the experience of millions of marginalised Americans during the Great Depression. It was a dark chapter, when deteriorating living conditions and social marginalisation became clear symptoms of a deep economic and humanitarian crisis.

The Great Depression exacerbated existing racial inequalities in the United States, with a disproportionate effect on African-American communities. For example, while the national unemployment rate reached alarming heights, it was around 50% higher among African-Americans. This poignant statistic highlights a reality where African-Americans were often the first to be laid off and the last to be hired. With the rise in unemployment, a phenomenon of reverse migration has occurred. Around 1.3 million African-Americans, a significant proportion of the urban African-American population at the time, found themselves forced to return to the South, often facing a life as sharecroppers or farmers. This was a return to precarious living and working conditions, exacerbating poverty and discrimination. Wages for African-Americans, already low before the Depression, fell even further. The average African-American worker could earn up to 30% less than a white worker, exacerbating the economic and social challenges. Living conditions for African-Americans also deteriorated. In the Hoovervilles, where large numbers of African-Americans found themselves living, conditions were precarious. The lack of basic services such as drinking water and sanitary facilities affected up to 90% of coloured residents in these settlements. These figures reveal not only the devastating economic impact of the Great Depression on African-Americans, but also how the crisis intensified racial and social inequalities, plunging many African-Americans into deep poverty and precariousness and highlighting the systemic discrimination of the time.

The impact of the Great Depression on Mexican immigrants was exacerbated by discriminatory government policies. Between 1929 and 1936, the 'Mexican repatriation' saw a considerable number of individuals of Mexican origin forced to leave the United States. Precise estimates suggest that up to 60% of those affected were in fact American citizens, born and raised in the United States. The difficult economic climate has led to increased xenophobia. With unemployment reaching 25% nationally during the Great Depression, the pressure to 'free up' jobs fuelled anti-immigrant sentiment. For Mexican-Americans, this often translated into mass deportations, where between 10% and 15% of the Mexican population living in the United States was forced to leave. The conditions of "repatriation" were often brutal. Trains and buses were used to transport people of Mexican origin to Mexico, and around 50% of them were children born in the United States. They found themselves in a country they barely knew, often without the resources to settle down and start a new life. Instead of solving the problem of unemployment, the repatriation policy exacerbated human suffering. Mexican-Americans, including US citizens of Mexican origin, were stigmatised and marginalised, and communities were torn apart. This chapter in American history highlights the dangers of xenophobia and discrimination, particularly during times of economic crisis.

The Great Depression was not limited to the borders of the United States; it also deeply affected Mexico, exacerbating the challenges faced by repatriated individuals. At the same time as hundreds of thousands of people of Mexican origin, including US citizens, were being sent back to Mexico, the country was facing its own economic crises. Unemployment was high, and the mass return of people put further pressure on an already fragile economy. Estimates suggest that Mexico, with an economy that had contracted by almost 17% during the Depression years, was not equipped to handle the sudden influx of workers. The absorption capacity of the labour market was limited; demand for labour far outstripped supply, leading to rising unemployment and poverty. Many returnees were US citizens who found themselves in an unfamiliar country, without resources or support networks. Around 60% of those deported had never lived in Mexico. They faced integration challenges, including language and cultural barriers, in an inhospitable economic environment. This massive displacement has had lasting consequences. Families were separated, community ties were broken, and a collective trauma set in. This episode bears witness to the profound and lasting repercussions of migration policies, especially when implemented in the context of a global economic crisis. The resilience of those affected, however, also testifies to the human capacity to adapt and rebuild in extraordinary circumstances.

The Great Depression exacerbated existing racial and economic inequalities in the United States. Although the crisis affected all segments of the population, marginalised groups such as African-Americans and Mexican immigrants were disproportionately affected, compounding their daily hardships and struggles. African-Americans, already facing systemic segregation and discrimination, saw their situation worsen during the Great Depression. The unemployment rate among African-Americans was about double that of whites. Many relief initiatives and employment programmes were either inaccessible to people of colour or segregated and offered inferior wages and working conditions. African-American workers were often the first to be fired and the last to be hired. In the agrarian South, many black farmers, already exploited as sharecroppers, were evicted from their land as a result of falling prices for agricultural products, exacerbating poverty and food insecurity. Mexican immigrants, too, suffered exacerbated prejudice. Mass deportations and forced repatriations have broken up families and communities, leaving many people in precarious situations in both the United States and Mexico. These actions were exacerbated by xenophobic sentiments, which were often amplified during periods of economic crisis. The struggle for access to resources and aid was a common theme during this period. Existing racial prejudices limited marginalised groups' access to government relief programmes and economic opportunities, exacerbating inequality and deprivation. The Great Depression highlighted deep fissures in equity and justice in American society, fissures that continued to be addressed and contested in the decades that followed.

The election of 1932 and the rise of Franklin D. Roosevelt[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Herbert Hoover, President of the United States from 1929 to 1933, was often criticised for his handling of the Great Depression. His ideological beliefs in 'rugged individualism' and laissez-faire economics led him to adopt a hands-off approach, in stark contrast to the public's growing expectations of government action. Hoover believed that the primary responsibility for economic recovery lay with individuals, businesses and local communities. He firmly believed in the inherent ability of the American economy to recover naturally without direct government interference. Hoover encouraged private initiative and charity as the primary means of relieving public distress. He expected businesses to avoid layoffs and maintain wages, and the wealthy to contribute generously to charitable efforts to help the less fortunate. However, these expectations proved unrealistic in the gloomy economic reality of the time, marked by a rapid contraction in employment, bankruptcies and widespread social distress. The American people, faced with astronomical unemployment rates, loss of housing and poverty, expected a more vigorous and immediate response. The perception of Hoover's inaction contributed to a sense of despair and abandonment among the population, making the Hoovervilles, shanty towns where the homeless lived, visible and ubiquitous symbols of the perceived failure of his presidency. It was only towards the end of his term that Hoover began to recognise, at least in part, the need for more direct federal action to combat the economic crisis. By then, however, public confidence in his ability to steer the country through the Depression had been profoundly eroded. Franklin D. Roosevelt's landslide victory in the 1932 presidential election reflected the public's yearning for a change of direction and vigorous government action to turn the nation around.

In 1932, the economic and social distress caused by the Great Depression was palpable in every corner of the United States. The apparent failure of the hands-off approach of President Hoover and the Republican Party left many Americans disillusioned and desperate, intensifying the call for decisive government action. Unemployment had reached record levels, poverty and homelessness were rampant, and ordinary citizens were struggling to survive. Franklin D. Roosevelt, with his charisma and empathetic approach, captured the nation's attention. He presented the "New Deal" as a bold and necessary remedy to combat the ravages of the Depression. He pledged to use the power of the federal government to alleviate the suffering of citizens, stimulate economic recovery and introduce structural reforms to prevent a recurrence of the crisis. This radical departure from laissez-faire orthodoxy was exactly what many voters were looking for. Roosevelt's promise of swift, direct and vigorous action inspired confidence and hope in a country beset by despair and mistrust. His proposals aimed to create jobs, support farmers, stabilise industry and reform the financial system. Roosevelt's election in 1932 therefore symbolised not only a rejection of Hoover's conservative approach, but also a clear public mandate for proactive government intervention. It marked the beginning of an era of transformation in which the state played a pivotal role in the economy, a trend that would continue for decades. Roosevelt's election victory signalled a transition to a government that, rather than standing on the sidelines, took bold steps to protect and support its citizens in times of crisis.

In contrast, the Democratic Party fielded Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man whose energy, confidence and bold proposals for a "New Deal" promised radical change and vigorous action to combat the Depression. Roosevelt proclaimed that the economic and social deterioration required direct and substantial intervention by the federal government to create jobs, support agriculture, stabilise industry, and reform the financial system. The contrast between the two candidates was clear. Hoover, though respectable, was associated with policies that seemed powerless in the face of the scale of the crisis, and he was seen by many as aloof and unresponsive to the distress of the population. His message that the economy was on the mend seemed out of touch with the reality of millions of Americans who were unemployed, homeless and living in poverty. Roosevelt, by contrast, communicated a dynamic and empathetic vision. His commitment to using government power to bring direct and immediate relief to affected citizens and to institute structural reforms to prevent a recurrence of the crisis resonated deeply with a population in distress. Ultimately, the election of 1932 was a clear reflection of the American people's desire for change. Hoover and the Republicans were swept aside in a crushing defeat, while Roosevelt and his bold New Deal programme were greeted with a mixture of hope and despair. The election result marked the beginning of a profound transformation in the government's approach to the economy and social welfare, ushering in an era of government activism that would define American politics for decades to come.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) embodied a wave of transformation and renewal in American politics and governance. Taking the reins of a nation deeply rooted in the economic and social desolation of the Great Depression, FDR infused a sense of hope and renewed confidence among American citizens. His New Deal programmes, characterised by a series of bold policies and projects, centred on the three 'R's': Relief (relief for the poor and unemployed), Recovery (recovery of the economy) and Reform (reforms to prevent another depression). FDR catapulted into iconic popularity and leadership, largely due to his ability to communicate directly with the American people. His 'fireside chats', regular radio speeches in which he explained the policies and intentions of his administration, played a crucial role in restoring public confidence and articulating his vision for national renewal. Interestingly, FDR was not the first Roosevelt in the White House. Theodore Roosevelt, another prominent member of the family, had also held the highest office. Theodore was a progressive who initiated many reforms aimed at controlling business, protecting consumers and conserving nature. FDR's presidency seemed a natural extension of Theodore's legacy of renewal and progress. The two men shared common traits, including a commitment to public service, a willingness to challenge established norms, and a passion for creating a more just and equitable society. Although distant cousins, they shared a common vision of renewal that was not only symbolic of their family lineage but also indicative of their transformative impact on the American nation. Today, their legacies are intrinsically linked to periods of progress and transformation, establishing the Roosevelt family as a dynamic force in American political history.

Franklin D. Roosevelt grew up in an environment of privilege and opulence, imbued with the advantages of a well-to-do and well-connected New York family. His formative years at Groton and Harvard were characterised not only by academic excellence, but also by a network of relationships that shaped his future political rise. At Groton and Harvard, Roosevelt developed a distinct personality, marked by charisma and leadership. Although academic rigour and intellectual opportunities were abundant, it was the social culture and relationships that Roosevelt cultivated during these years that were particularly influential. When he joined Columbia Law School, Roosevelt was already a young man of great promise. Although he did not finish his degree, his career was not hindered. His marriage to Eleanor Roosevelt, a woman of conviction and passion, marked a significant turning point. Eleanor was not only a link to the iconic presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, she also became a powerful force in her own right, committed to humanitarian and social causes. Franklin D. Roosevelt was a product of his upbringing and environment. Every step of the way, from Groton to Harvard and beyond, helped forge a leader whose ambition, insight and network were ready to meet the challenges of his time. His marriage to Eleanor not only strengthened his social and political position, but also introduced a dynamism and social commitment that would become central to his presidency. Together, they entered the political arena, ready to influence the course of American history in the tumultuous decades ahead.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's political career was as impressive as it was diverse. His first steps as a member of the New York State Senate were a springboard for his passionate commitment to the public good and the general interest. His deeply held convictions in favour of workers' and consumers' rights not only defined his tenure in the Senate, but also paved the way for the reform initiatives he would later introduce as President. Serving under Woodrow Wilson as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Roosevelt honed his sense of governance and diplomacy. This broadened his horizons, exposing him to the complexities and challenges of national and international politics. However, it was in 1921 that Roosevelt faced one of the most difficult challenges of his life. Polio changed everything, transforming not only his physical condition but also his outlook on life. Far from holding him back, the disease fuelled a determination and resilience that would become cornerstones of his leadership. His personal battle with illness strengthened his empathy for the less fortunate and disadvantaged, broadening his vision of social and economic justice. As President, Roosevelt's ability to overcome personal adversity translated into bold leadership in times of crisis. During the Great Depression, his hard-won empathy and unwavering commitment to progress combined in the formulation of the New Deal, a series of innovative policies and programmes designed to restore hope, dignity and prosperity to a country besieged by economic despair. When the Second World War broke out, Roosevelt again stepped forward with unwavering determination. His leadership during the war was not only the product of strategy and diplomacy, but also the expression of a deeply personal resilience and tenacity. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man shaped by adversity, became a symbol of American resilience. His leadership during the Great Depression and the Second World War is the testament of a life in which personal challenges were transformed into bold public engagement, leaving an indelible mark on the nation and the world.

Defeat in the 1920 election was not the end, but rather a new beginning for Franklin D. Roosevelt. This failure, far from extinguishing him, rekindled his passion and commitment to public service. His return to New York was not a retreat, but an opportunity to refocus, rebuild and prepare for the challenges ahead. Polio, a debilitating disease that could have ended the careers of many public figures, became a catalyst for transformation for Roosevelt. With unwavering determination, he not only rebuilt himself physically, but also refined and expanded his political vision. From this confrontation with polio came a deeper sensitivity to the struggles of others, an empathy that influenced and enriched his political approach. In 1928, American politics was about to undergo a transformation. Roosevelt, now Governor of New York, was at the forefront of this change. The Great Depression was not just an economic crisis, but also a profound humanitarian and social crisis. The old methods and ideas were no longer sufficient. A new kind of leadership, bold, compassionate and innovative, was needed. Roosevelt answered the call. His commission for the unemployed, his stance in favour of retirement pensions and trade union rights were not symbolic gestures, but concrete actions. They demonstrated a deep understanding of the challenges of the time and a willingness to act. Roosevelt's term as governor was marked not only by progressive policies, but also by a new approach to politics, in which humanity, compassion and innovation were central. He was a renewed Democrat, a transformed leader, who was prepared to go beyond traditional norms and expectations. Victory in the 1932 presidential election was therefore no accident, but the result of a profound personal and political transformation. The New Deal, with its range of progressive and humanitarian policies, was the manifestation of a vision forged through years of struggle, challenge and transformation. Thus Roosevelt, a man scarred and shaped by adversity, ascended to the presidency with deep conviction and bold vision. His leadership during the Great Depression was not just the product of politics, but also the expression of a deep humanity, a broad compassion and a resilience forged in the heat of personal adversity.