« The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 177 : | Ligne 177 : | ||

[[File:National Labor Relations Act2.jpg|right|thumb|President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the National Labor Relations Act on 5 July 1935. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins (right) looks on.]] | [[File:National Labor Relations Act2.jpg|right|thumb|President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the National Labor Relations Act on 5 July 1935. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins (right) looks on.]] | ||

Roosevelt's intensification of reforms in 1935 and 1936 took place against a backdrop of persistent challenges related to unemployment and inequality. The creation of the National Youth Administration and the expansion of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were direct responses to the need to create jobs and support individuals affected by the economic depression. These initiatives had a particular focus on supporting young people and creative professionals, in recognition of the multi-dimensional impact of the crisis. While these programmes have provided significant help and created opportunities, they have not been without their limitations. Unemployment, despite these interventions, remained an endemic problem, underlining the depth of the crisis and the challenges inherent in fully addressing the impacts of the Great Depression. Criticism grew, pointing to the inequality in the distribution of the benefits of the New Deal programmes. While well-organised entities benefited disproportionately, the most vulnerable segments of society felt neglected. This inequality was not only an economic problem, but also a political challenge. The cracking of the political consensus was palpable. Some members of the Democratic Party, dissatisfied with existing policies, began to disassociate themselves, signalling an ideological split. Protests against government policies reflected growing dissent and a diversification of perspectives on how to respond effectively to the economic crisis. This discontent and diversity of opinion marks a moment of intense political and social dynamism. Navigating conflicting demands, diverse needs and multiple expectations became a central feature of governance under Roosevelt. The tensions between economic efficiency, social equity and political cohesion intensified, setting a precedent for the debates on economic and social policy that continue to this day. Every action and every initiative was scrutinised in the light of the imperatives of justice, inclusion and efficiency, a balance that is always difficult to achieve in times of deep crisis. | |||

Franklin D. Roosevelt | Franklin D. Roosevelt found himself in a delicate situation. While his New Deal programme had brought some relief to the American economy and he had succeeded in laying the foundations for a recovery, he was faced with a major dilemma. Unemployment remained unacceptably high, and with an election on the horizon, it was imperative to step up efforts to generate employment and establish economic stability. It was a delicate balancing act. Roosevelt had to navigate between pursuing policies that would bring macroeconomic stability and meeting the immediate needs of those most affected by the Depression. The first phase of the New Deal had been criticised for favouring specific groups. Big business and well-established farmers had been the main beneficiaries, and this had exacerbated inequalities. In this tense political environment, every decision was scrutinised. Roosevelt was aware that the growing inequalities were unsustainable, but the rectification of these inequalities had to be carefully orchestrated. Marginalised groups and those most in need needed support, but implementing policies that could potentially alienate other segments of the population or economic partners was a minefield. 1935 and 1936 were years of recalibration. The new reforms were bold and aimed to extend the economic safety net to include those who had been left behind. It was a period of political and economic readjustment, when the raw reality of the Depression was confronted with intensified efforts not only to stabilise the economy but also to ensure a fairer distribution of opportunities and resources. Political and social discontent was a palpable reality. Members of the Democratic Party broke away, signalling a fracture in the previous political consensus. Roosevelt, however, was determined. His commitment to the New Deal, despite its imperfections and criticisms, was unshakeable. The complexity of the task was to balance economic imperatives, social expectations and political reality in a world still recovering from one of the worst economic crises in modern history. This chapter of his administration illustrated the complexity inherent in governance in times of crisis, where every step forward is fraught with unexpected challenges, and where flexibility and resilience become indispensable assets. | ||

The Social Security Act of 1935 embodied a major transformation in the US federal government's responsibility to its citizens. Prior to the Act, protection and assistance for the vulnerable had been largely neglected, leaving many families without a safety net in times of need. Signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Act was one of a series of radical New Deal reforms designed to reshape the way government interacted with society, especially in times of economic crisis. The first component, the retirement programme, provided a solution to the financial insecurity experienced by the elderly, a problem exacerbated by the Great Depression. The fact that this programme was funded by both employers and employees underlined a principle of solidarity and shared responsibility. It offered older people financial dignity, guaranteeing a stable income after years of hard work. The unemployment assistance programme was the second cornerstone. It was a direct response to the acute economic vulnerability exacerbated by the Great Depression. With millions of people out of work, often through no fault of their own, this programme promised temporary support, underlining the government's role as a backstop in times of unforeseen economic crisis. The third component addressed the needs of the blind, disabled, elderly and children in need. It recognises the diversity of needs within society and strives to provide specialist support to ensure that even often overlooked groups receive the attention and support they need. Each component of the Social Security Act represented a step towards a government that not only governs but cares for its citizens. It was a move away from laissez-faire and towards a more paternalistic approach, where the protection and welfare of citizens, especially the most vulnerable, was placed at the centre of the political agenda. This approach set a precedent that not only shaped American domestic policy for decades to come, but also inspired welfare systems around the world. | |||

The Social Security Act is often cited as one of the most significant legislative achievements of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration and the New Deal. By establishing a financial safety net for the elderly, the unemployed and the disabled, this law profoundly transformed the role of the federal government in the lives of American citizens. Prior to the Act, many elderly and vulnerable people were left to fend for themselves, relying on charity or family for their livelihood. Social Security changed this dynamic, introducing direct government responsibility for the economic well-being of citizens. This helped reduce poverty and economic insecurity, providing greater financial stability for millions of Americans. In addition, the Act laid the foundation for the modern welfare system in the United States, establishing principles and practices that continue to inform public policy today. Individuals and families in situations of need can count on some measure of support from the state, which has strengthened social cohesion and stability. By embedding solidarity and mutual support into the very fabric of government policy, the Social Security Act helped to define a new era of governance in the United States. It was a significant step towards a more engaged welfare state, an aspect that has become central to American policy and has also influenced welfare systems around the world. In addition, by promoting the welfare and security of citizens, it laid the foundations for a more balanced and equitable society, reducing inequality and improving the quality of life for many Americans. | |||

The implementation of the Social Security programme has met with various challenges and criticisms. The exclusion of small farmers, sharecroppers, domestic workers and trade unions highlighted significant gaps in the system. These vulnerable groups were among those hardest hit by the Great Depression, and their exclusion from Social Security benefits exacerbated their precarious situation. Sharecroppers and domestic workers, in particular, were omitted because of the structure of informal and non-contractual employment, which raised concerns about equity and inclusion. Trade unions, which were already fighting for workers' rights in a difficult economic context, also faced challenges in accessing benefits. Criticism also came from the amount of assistance provided. Although Social Security represented a significant step forward in providing government support to those in need, the amount of benefits was often insufficient to meet basic needs, and many continued to live in poverty. However, despite these criticisms and challenges, the Social Security programme laid the foundations for a system of social protection in the United States. Over the years, it has been amended and expanded to include previously excluded groups and to increase the amount of assistance provided. This demonstrates the evolving nature of these public policies, which can be adapted and improved to better meet the needs of society. These initial challenges have also fuelled debate about the role of government in the economic well-being of citizens and have helped to shape future welfare and reform programmes. Ultimately, despite its imperfections, the Social Security Act marked an important milestone in the development of American welfare policy. | |||

The passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) in 1935 was an important milestone in the history of labour relations in the United States. It profoundly altered the landscape of industrial and labour relations by legalising the formation of trade unions and promoting collective bargaining. Prior to the introduction of the NLRA, workers often faced difficult working conditions, low wages and considerable resistance from employers to the establishment of unions. In-house" unions, which were controlled by employers, were often used to thwart efforts to form independent unions. The NLRA not only prohibited these practices but also established mechanisms to ensure that workers' rights to form unions and bargain collectively would be respected. The creation of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) was crucial to the enforcement of these rights. The NLRB had the power to order the reinstatement of workers dismissed for union activities and could also certify unions as legitimate representatives of workers. The impact of the NLRA was profound. It helped to balance the power relations between employers and employees, leading to a significant increase in the number of unionised workers and improvements in wages and working conditions. The Act helped establish a national standard for relations between employers and workers, anchoring the right to collective bargaining in US federal law. However, like any major piece of legislation, the NLRA also faced criticism and challenges. Some employers and industry groups have resisted the new regulations, and there have been debates about the balance between workers' rights and corporate economic interests. Nevertheless, the NLRA remains one of the most influential pieces of legislation of the New Deal era, laying the foundations for modern labour relations in the United States and helping to create a more robust middle class in the decades that followed. | |||

= | = Franklin D. Roosevelt's second term: 1936 - 1940 (Supreme Court battles, economic challenges) = | ||

The presidential election of 1936 saw Franklin D. Roosevelt win a resounding victory, securing a second term in office. During his campaign, the issue of the radical and ambitious New Deal reforms that he had launched during his first term took centre stage. Roosevelt was criticised by his opponent Alf Landon and other conservatives for deviating from the fundamental principles of American government and introducing elements of socialism into American politics. However, these attacks failed to win the support of a significant majority of voters. Roosevelt's New Deal policies and programmes were widely popular with the masses, who saw them as a necessary relief from the rigours of the Great Depression. Eleanor Roosevelt, his wife, played a crucial role in his re-election campaign. She was not only an influential first lady but also an ardent defender of civil rights, the rights of women and the poor. Eleanor became a respected and admired public figure for her dedication and commitment to society's most disadvantaged. Roosevelt's election victory in 1936 was a clear endorsement of his policies by the American people. It strengthened his determination to pursue and expand the New Deal initiatives, despite persistent opposition from some quarters. His second term saw a consolidation of the reforms initiated during his first term and an increased commitment to ensuring the economic and social well-being of ordinary US citizens. Thus, although he was criticised for approaches deemed too progressive or interventionist, Roosevelt's popularity and public support for New Deal policies were evident in the election results, indicating that, for the majority of Americans, the course set by the President was not only necessary but also beneficial in the context of the most devastating economic crisis of the twentieth century. | |||

Franklin D. Roosevelt's victory in 1936 was not simply a re-election for the incumbent President, but symbolised a more profound transformation of the American political landscape. It reflected a new coalition, a heterogeneous but powerful alliance of diverse groups united around the principles and programmes of the New Deal. It was a convincing demonstration of Roosevelt's ability to rally a wide range of groups, from the urban working class to Midwestern farmers, from Southern Democrats to recent immigrants, to a multitude of ethnic groups and workers from all sectors. The New Deal coalition was not simply a temporary electoral alliance but shaped the identity and direction of the Democratic Party for generations to come. It embodied a more progressive and inclusive vision of American politics, where the interests of working people, the poor and the marginalised were recognised and taken into account in national policy-making. Roosevelt had succeeded in weaving a social and economic net that not only mitigated the devastating effects of the Great Depression but also laid the foundations for a modernised welfare state and regulated capitalism. His victories in almost every state in the country reflected popular approval of interventionist and redistributive policies which, although criticised by conservatives, were widely seen as necessary and beneficial by a large majority of voters.<gallery mode="packed" widths="200" heights="200"> | |||

Fichier:Manchester Elm Street 1936 LOC fsa 8a02859.jpg|Election poster in Manchester, NH. | |||

<gallery mode="packed" widths="200" heights="200"> | Fichier:A Mule and a Plow 05986r.jpg|Resettlement Administration poster, by Bernarda Bryson Shahn. | ||

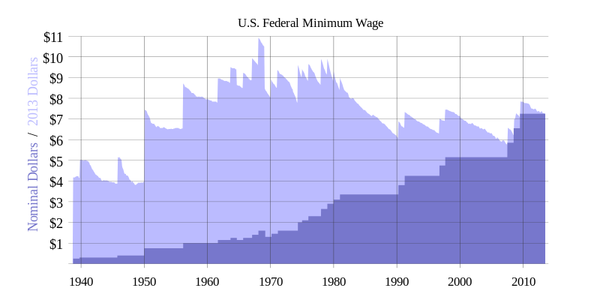

Fichier:Manchester Elm Street 1936 LOC fsa 8a02859.jpg| | Fichier:History of US federal minimum wage increases.png|History of the federal minimum wage in real and nominal dollars. | ||

Fichier:A Mule and a Plow 05986r.jpg| | |||

Fichier:History of US federal minimum wage increases.png| | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Franklin D. Roosevelt's election to a third and fourth term is an anomaly in American history. He was elected for a third term in 1940 because of the imminent threat of the Second World War. Roosevelt was an experienced leader and American voters, faced with international uncertainty, chose to keep him in power to ensure continuity of leadership. Roosevelt's choice for a fourth term in 1944 also occurred in the context of the war. The nation was immersed in global conflict, and changing presidents during wartime was not considered to be in the best interests of the country. Roosevelt's stability and experience were again favoured. However, after his death in 1945, it became clear that the practice of allowing a president to serve an unlimited number of terms needed to be re-examined. Executive power in the hands of one person for a long period of time could potentially be a risk to American democracy. As a result, the 22nd Amendment was proposed and adopted, limiting a President to two terms in office. This was intended to ensure regular renewal of leadership, keep the President accountable to the electorate and prevent excessive concentration of power. Since then, all American presidents have been limited to two terms, a principle that reinforces the dynamic and responsive nature of American democracy, ensuring an orderly transition of power and allowing the emergence of new leaders with fresh ideas and perspectives. | |||

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was an important step in Roosevelt's ongoing effort to combat the devastating effects of the Great Depression. Despite positive intentions, challenges such as insufficient funding and the massive scale of poverty and despair meant that the programme's impact was more limited than hoped. During this period, the economic crisis did not discriminate; it affected all aspects of American society, but small farmers were particularly vulnerable. The FSA, with its limited resources, tried to provide a solution for this specific demographic, but the challenges were monumental. In the South, the impact of the programme was even more diluted. The socio-economic structure, marked by racial discrimination and inequality, exacerbated the economic difficulties. Sharecroppers, both white and black, found themselves in an extremely precarious situation, often without land or means of subsistence. The effort to provide low-interest loans and technical assistance was a lifeline for some, but unattainable for the majority. The complex realities of the time - a ravaged economy, a changing society and deep-rooted inequalities - made the successful implementation of the FSA programme a daunting challenge. Despite this, the FSA remains a testament to the Roosevelt administration's commitment to trying to bring relief and positive change, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. It also laid the groundwork for future thinking and action on agricultural policy and social security in the United States. | |||

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) programme was a delicate balance in Roosevelt's attempt to navigate between support for small farmers and the wider economic imperatives that favoured large farms. While small farmers were an important target, economic efficiency and productivity were equally pressing issues that could not be ignored. By providing advisory and technical services to large landowners, the FSA was not only injecting capital but also helping to improve farming methods, optimising productivity and sustainability. This technical assistance was aimed not only at increasing production, but also at improving the working conditions of farm workers, a group that was often neglected and exploited. Large landowners benefited from advice on how to optimise the management of their land, which led to an increase in productivity. Paradoxically, by helping large farms, the FSA was also indirectly helping to improve the lives of farm workers through more productive and efficient farming. Indeed, the central dilemma was that support for small farmers and large landowners was not mutually exclusive. Both were essential for a robust agricultural economy. Small farmers needed support to survive, while large farms were essential for economic efficiency and large-scale food production. So the FSA, with all its apparent contradictions, was a reflection of the complex landscape of the time. It was an effort to balance economic, social and human imperatives, a juggling act between the immediate need for relief and the long-term goals of productivity and sustainability. In this complex context, the FSA succeeded in creating a positive impact, not only by directly supporting those in need but also by introducing structural changes that would benefit the farming community as a whole and beyond. | |||

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 marked a crucial step in labour legislation in the United States, establishing important safeguards to protect workers from exploitation. The genesis of this law was centred on the protection of non-union workers, a vulnerable population at the time who were often subject to unfair and inequitable working conditions. However, its application transcended this target population to encompass unionized workers as well, setting a universal minimum standard that elevated the foundation of working conditions across the country. However, the FLSA was not without its initial limitations. Its scope was confined to workers in certain industries, leaving a substantial segment of the workforce, notably those in agriculture and domestic service, without the necessary protections. This was a reflection of the political and social compromises of the time, where the needs of certain groups were often balanced against economic and political realities. Over time, the FLSA evolved, expanding to envelop a larger portion of the workforce and raising the minimum wage. This adaptability and evolution have been crucial in ensuring that the law remains relevant and effective in the face of changing challenges and workforce dynamics. It has become a living document, adjusted and modified to meet the changing demands of American society. Today, the FLSA remains a pillar of American labour law. It is a testament to the desire of government and society to protect workers from exploitation and to ensure that economic gains are shared fairly. By setting minimum standards for wages and working conditions, it creates a balanced playing field where workers can contribute to economic prosperity while being assured of fair and equitable working conditions. The Act remains a vibrant example of the legislative system's ability to adapt and evolve to meet the changing needs of its population. | |||

= | = Social impact of the New Deal: assessing the legacy of policies and programmes = | ||

L'héritage du New Deal est un sujet de vaste et intensif débat. Initié par le président Franklin D. Roosevelt dans les années 1930 pour répondre à la Grande Dépression, le New Deal a mis en place une série de programmes et de réformes qui ont non seulement modifié le paysage économique américain, mais ont également influencé les attentes des citoyens en matière de gouvernement. D'une part, le New Deal a été salué pour avoir introduit un filet de sécurité social significatif, avec la création de la sécurité sociale étant une de ses réalisations les plus notables. Cet élément clé a apporté un soulagement nécessaire aux personnes âgées, aux personnes handicapées et aux chômeurs, et est devenu un élément central du système de bien-être américain. De plus, les droits des travailleurs se sont considérablement étendus sous le New Deal, renforçant les syndicats et rapprochant le parti démocrate de la classe ouvrière. Des millions de chômeurs ont trouvé un emploi grâce à des programmes de travaux publics, et des réformes financières et bancaires ont stabilisé le système financier. Cependant, le New Deal n'était pas exempt de critiques. Certains ont avancé que ses mesures n'étaient pas suffisantes et que les pauvres, en particulier parmi les minorités, étaient souvent négligés. L'interventionnisme gouvernemental a été un sujet de contentieux, en particulier parmi la communauté des affaires qui le percevait comme excessif. Bien que le New Deal ait introduit d'importantes réformes structurelles, il n'a pas complètement résolu la Grande Dépression, et il a fallu l'effort de guerre de la Seconde Guerre mondiale pour revitaliser pleinement l'économie américaine. L'augmentation des dépenses publiques a également soulevé des inquiétudes sur la dette nationale. L'héritage persistant du New Deal réside dans son influence continue sur la politique et la société américaines. Les débats qui ont commencé à cette époque sur l'équilibre entre l'intervention du gouvernement et la liberté du marché persistent dans le discours politique contemporain. Dans l'ensemble, le New Deal est souvent perçu comme une réponse audacieuse à une crise économique et sociale sans précédent, bien qu'il soit également associé à une intervention gouvernementale accrue dans l'économie. Ses réformes structurelles et sociales ont laissé une empreinte durable qui continue d'influencer la politique, l'économie et la société américaines à ce jour. | L'héritage du New Deal est un sujet de vaste et intensif débat. Initié par le président Franklin D. Roosevelt dans les années 1930 pour répondre à la Grande Dépression, le New Deal a mis en place une série de programmes et de réformes qui ont non seulement modifié le paysage économique américain, mais ont également influencé les attentes des citoyens en matière de gouvernement. D'une part, le New Deal a été salué pour avoir introduit un filet de sécurité social significatif, avec la création de la sécurité sociale étant une de ses réalisations les plus notables. Cet élément clé a apporté un soulagement nécessaire aux personnes âgées, aux personnes handicapées et aux chômeurs, et est devenu un élément central du système de bien-être américain. De plus, les droits des travailleurs se sont considérablement étendus sous le New Deal, renforçant les syndicats et rapprochant le parti démocrate de la classe ouvrière. Des millions de chômeurs ont trouvé un emploi grâce à des programmes de travaux publics, et des réformes financières et bancaires ont stabilisé le système financier. Cependant, le New Deal n'était pas exempt de critiques. Certains ont avancé que ses mesures n'étaient pas suffisantes et que les pauvres, en particulier parmi les minorités, étaient souvent négligés. L'interventionnisme gouvernemental a été un sujet de contentieux, en particulier parmi la communauté des affaires qui le percevait comme excessif. Bien que le New Deal ait introduit d'importantes réformes structurelles, il n'a pas complètement résolu la Grande Dépression, et il a fallu l'effort de guerre de la Seconde Guerre mondiale pour revitaliser pleinement l'économie américaine. L'augmentation des dépenses publiques a également soulevé des inquiétudes sur la dette nationale. L'héritage persistant du New Deal réside dans son influence continue sur la politique et la société américaines. Les débats qui ont commencé à cette époque sur l'équilibre entre l'intervention du gouvernement et la liberté du marché persistent dans le discours politique contemporain. Dans l'ensemble, le New Deal est souvent perçu comme une réponse audacieuse à une crise économique et sociale sans précédent, bien qu'il soit également associé à une intervention gouvernementale accrue dans l'économie. Ses réformes structurelles et sociales ont laissé une empreinte durable qui continue d'influencer la politique, l'économie et la société américaines à ce jour. | ||

Version du 6 novembre 2023 à 11:12

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

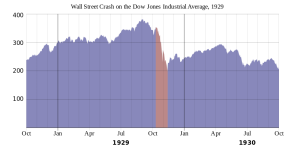

The 1920s, glittering with prosperity and lulled by carefree optimism, are often referred to as the 'Roaring Twenties'. This period illustrates a flourishing America, where abundance and success seemed to be the norm. However, this era of opulence and euphoria came to an abrupt end with the stock market crash of October 1929, opening the door to the grim Great Depression. This economic catastrophe, the most devastating in American history, transformed a once prosperous country into a nation reeling from massive unemployment, widespread poverty and financial instability.

The Great Depression not only shook the economy; it trampled the soul and spirit of the American people. Millions lost not only their jobs but also their faith in a prosperous future. Businesses and banks went bankrupt, leaving behind them a trail of desolation and helplessness. Farmers, the backbone of the economy, have been dispossessed of their land, adding to the sense of despair.

The crisis has sown doubt and uncertainty in the minds of Americans, once optimistic and confident in their prosperous nation. A deep distrust of the economic system and government has sprung up, radically changing the national psyche. However, in this abyss of despair, the innovative policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal emerged like a beam of light. Bold reforms and a government now more involved in the economy began a healing process, laying new foundations for a gradual recovery.

The Great Depression not only reconfigured American politics, catalysing the shift in power from the Republicans to the Democrats, but also prompted a profound re-examination of the relationship between the citizen and the state. The Democratic Party, once associated with the South and Catholic immigrants, has become the champion of the working and middle classes, which have been hardest hit by the crisis. The American political landscape was redefined, and with it an era of renewal and social transformation emerged.

This monumental upheaval spawned a blossoming of social movements, a reassessment of cultural values and a redefinition of national identity. The Great Depression left an indelible scar on American history, a sombre reminder of human vulnerability to the unpredictable forces of the economy. Yet it also illustrated the nation's resilience and innovation, highlighting America's undeniable ability to reinvent itself in the midst of the most devastating trials.

The causes of the 1929 stock market crash

The stock market crash of 1929 was not simply the result of economic instability in Europe or the inability of European nations to repay the loans they had taken out with American banks after the First World War. Rather, it was the consequence of a combination of economic, financial and political factors, each contributing to a collapse of devastating proportions. Unbridled stock market speculation was commonplace in the 1920s. Unrealistic optimism led many investors to place huge sums of money in the stock market, often on credit. This led to artificial inflation in share prices and the formation of a vulnerable financial bubble. Margin buying, or the excessive use of credit to buy shares, made the situation worse. When confidence collapsed, many investors found themselves unable to repay their loans, exacerbating the crisis. The lack of robust financial regulation allowed risky and unethical practices, making the stock market and banks unstable. In addition, panic and the rush to sell amplified the market collapse. An unprecedented volume of share sales precipitated a vertiginous fall in prices. Beyond the dynamics of the stock market, the US economy was suffering from deep-seated problems. Wealth inequalities, industrial and agricultural overproduction and a decline in consumption all contributed to a fragile economic base. Banks, having invested heavily in the stock market or lent money to investors to buy shares, were hit hard when share values plummeted. Their failure exacerbated the crisis of confidence and further reduced access to credit. Instability in Europe and the inability of European countries to repay their debts also played a role in the crisis. The interconnection of the world's economies turned a national crisis into an international disaster. These factors converged to create an environment where a large-scale economic collapse was inevitable. This toxic mix of unregulated speculation, easy credit, underlying economic instability and panic selling was exacerbated by international economic instability. This highlighted the imperative need for greater regulation and oversight of the stock market and banking system, leading to substantial reforms in the years that followed to prevent a recurrence of such disasters.

This dichotomy between the international and domestic factors that led to the stock market crash of 1929 is at the heart of debates about the origins of the Great Depression. International economic tensions, notably European debt, cannot be overlooked. However, close inspection reveals that fundamental economic dynamics in the United States also played a critical role. The Second Industrial Revolution, characterised by considerable technological advancement and industrial expansion, instilled a sense of economic invincibility and apparent prosperity during the 'Roaring Twenties'. This period saw the emergence of new industries, increased productivity and widespread financial euphoria. However, this economic effervescence concealed a vulnerable financial landscape, undermined by excessive speculative practices and a dangerous accumulation of debt. The prosperity of the 1920s was not as solid as it seemed. It was fuelled in part by easy access to credit and unbridled stock market speculation. Many investors, blinded by enthusiasm and optimism, were unaware of the risks inherent in a market saturated with speculative capital. The euphoria masked the underlying economic fragility and encouraged unsustainable optimism. The sharp fall came when economic reality caught up with speculation. Investors became aware of the latent instability and financial insecurity. The stock market crash that followed was inevitable, not because of external pressures, but rather because of unresolved internal flaws in the US economy. In this context, European debt and international instability were merely aggravating factors, not the root causes of the crisis. The very foundations of American prosperity were unstable, hollowed out by imprudent financial practices and a lack of adequate regulation. The Great Depression that followed was not only a brutal market correction but also a rude awakening for a nation that had been lulled into economic complacency for too long. It signalled the imperative need for a balance between innovation, growth and financial prudence, laying the foundations for a new economic order in the United States.

This debt-fuelled investment frenzy and unbridled optimism was a key element that precipitated the stock market crash of 1929. Market dynamics at the time were characterised by a collective euphoria in which caution took a back seat to blind confidence in a perpetual economic upswing. The idea that the market could rise indefinitely was ingrained in the minds of many investors. Their investment strategy, often devoid of prudence, was heavily geared towards buying shares on margin. This speculative approach, while lucrative in the short term, was inherently vulnerable, making the economy extremely susceptible to market fluctuations. Share prices had reached stratospheric heights, fuelled not by solid economic fundamentals but by unbridled speculation. This dislocation between the real and perceived value of shares created an unsustainable financial bubble. Every bubble, no matter how big or small, is bound to burst sooner or later. The bubble of 1929 was no different. When reality set in again, and investor confidence collapsed, the stock market was plunged into chaos. Investors, including those who had bought on margin and were already deeply in debt, rushed to sell, triggering a rapid and relentless downward spiral in share prices. The massive rush to dump equities exacerbated the crisis, turning a market correction that was perhaps inevitable into an economic catastrophe of staggering proportions. The consequences were felt far beyond Wall Street, permeating every nook and cranny of the US and global economy. This financial disaster was not the product of a single factor, but the result of a toxic combination of unregulated speculation, easy credit and complacency, a perfect storm that triggered one of the darkest periods in modern economic history. The lesson of the crash was clear: a market left to its own devices, without careful regulation and proper oversight, is liable to descend into excesses that can have devastating consequences for everyone.

The meteoric rise of the car and household appliance industries in the 1920s is a classic example of the double-edged sword of rapid industrial growth. Although these innovations marked an era of apparent prosperity, they also sowed the seeds of the impending economic crisis. Industrial production had reached historic highs, but this growth was not matched by equivalent demand. The American economic machine, with its overloaded production capacity, began to creak, generating a surplus of goods that far exceeded consumers' purchasing capacity. The spectre of overproduction, where factories were producing at a rate that outstripped consumption, became a worrying reality. The flourishing car and household appliance industries became victims of their own success. The domestic market was saturated; every American household that could afford a new car or appliance already had one. The imbalance between supply and demand set off a chain reaction, with falling consumption leading to reduced production, rising unsold stocks and falling profits for companies. This economic slowdown was a worrying omen in an already volatile financial landscape. The stock market, which had long been a source of prosperity, was ripe for a correction. Shares were overvalued, a product of speculation rather than the intrinsic value of companies. When business confidence faltered, a domino effect was triggered. Investors, nervous and uncertain, withdrew their capital, sending the market into a downward spiral. So the stock market crash of 1929 was not an isolated event, but the result of a series of interconnected factors. Industrial overproduction, market saturation, overvalued equities and a loss of business confidence converged to create a precarious economic environment. When the crash came, it was not just a financial correction, but a brutal reassessment of the foundations on which the prosperity of the 1920s had been built. Prudence and regulation became watchwords in discussions of the economy, ushering in an era in which rapid growth would be tempered by recognition of its potential limits and the dangers of excess.

The rise of consumer credit was a defining feature of the American economy in the 1920s, an era of rapid but reckless expansion. Citizens, lured by the promise of immediate prosperity, went into debt to enjoy a standard of living beyond their immediate means. Easy access to credit not only stimulated consumption but also engendered a culture of indebtedness. This easy access to credit has, however, concealed deep cracks in the country's economic foundations. Consumer spending, while high, was artificially inflated by debt. Individuals and families, seduced by the apparent abundance and easy access to credit, accumulated considerable debt. This dynamic created an economy which, although apparently prosperous on the surface, was intrinsically fragile, with stability dependent on consumers' ability to manage and repay their debts. When the optimism of the Roaring Twenties gave way to the reality of a declining economy, the fragility of this expansive credit system became apparent. Consumers, already heavily in debt and now faced with an uncertain economic outlook, cut back on their spending. Unable to repay their debts, a vicious circle of defaults and consumer recession set in, exacerbating the economic slowdown. This abrupt reversal revealed the inadequacy of an economy based on debt and speculation. The collapse of confidence and the contraction of credit were triggers for a crisis that swept through not only the United States but also the global economy. Individuals, companies and even nations found themselves trapped in a spiral of debt and default, ushering in an era of recession and readjustment. This scenario highlighted the need for careful and considered credit and debt management. The economic euphoria fuelled by easy credit and excessive consumption proved unsustainable. In the ashes of the Great Depression, a new approach to economics and finance began to emerge, one that recognised the dangers inherent in unregulated prosperity and sought a more sustainable balance between growth and financial stability.

The low interest rate regime that prevailed in the 1920s played a significant role in setting the stage for the stock market crash of 1929. Increased access to credit, facilitated by low interest rates, encouraged both consumers and investors to take on debt. In a climate where cheap money was readily available, financial prudence often took a back seat to excessive enthusiasm and confidence in the economy's upward trajectory. Cheap money not only fuelled consumption but also encouraged intense speculation on the stock market. Investors, armed with easily obtained credit, flocked to an already overvalued market, pushing share prices well beyond their intrinsic value. This dynamic created an overheated financial environment, where real value and speculation were dangerously misaligned. The correction came in the form of higher interest rates. This increase, while necessary to cool an overheated economy, came as a shock to investors and borrowers. Faced with higher borrowing costs and a growing debt burden, many were forced to liquidate their positions on the stock market. This scramble for the exit led to a massive sell-off, triggering a rapid and uncontrolled fall in share prices. The inversion of interest rates revealed the fragility of an economy built on the shifting sands of cheap credit and speculation. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed were dramatic manifestations of the limits and dangers of unregulated economic growth overly dependent on debt. The lesson learned was painful but necessary. In the years following the crisis, greater attention was paid to the prudent management of monetary policy and interest rates, recognising their central role in stabilising the economy and preventing speculative excesses that could lead to economic disaster. The disaster of 1929 prompted a profound reassessment of the principles and practices underpinning economic management, underlining the need for a balance between the imperatives of growth and the imperatives of financial stability and security.

The lack of robust regulation was a crucial weakness that exacerbated the severity of the 1929 stock market crash. At the time, the stock market was largely unregulated territory, a kind of financial 'wild west' where government oversight and investor protections were minimal or non-existent. This facilitated an environment of unbridled speculation, market manipulation and insider trading. The lack of transparency and ethics in stock market operations has created a highly volatile and uncertain market. Investors, lacking reliable and accurate information, were often in the dark, forced to navigate a market where asymmetric information and manipulation were commonplace. Trust, an essential ingredient of any healthy financial system, was eroded, replaced by uncertainty and speculation. In this context, fraud and insider trading proliferated, exacerbating the risks for ordinary investors who were often ill-equipped to understand or mitigate the dangers inherent in the market. Their vulnerability was exacerbated by the absence of regulatory protections, leaving many investors at the mercy of a capricious and often manipulated market. When the crash occurred, these structural and regulatory weaknesses were brutally exposed. Investors, already faced with a precipitous fall in stock market values, were left with no recourse in the face of an inadequate regulatory and protection infrastructure. The catastrophe of 1929 was a wake-up call for government and regulators. In its wake, an era of regulatory reform was ushered in, characterised by the introduction of stricter oversight mechanisms and protections for investors. Legislation such as the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 in the United States laid the foundations for a more transparent, fair and stable stock market. The harsh lesson of the stock market crash revealed the crucial importance of regulation and supervision in maintaining the integrity and stability of financial markets. It initiated a profound transformation in the way financial markets were perceived and managed, marking the beginning of an era in which regulation and investor protection became central pillars of financial stability.

Economic inequality was an underlying, and often overlooked, weak link in the economic fabric of the United States on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash. The growing gap between the rich and the working class was not simply a question of social justice, but also a factor of profound economic vulnerability. In the boom years of the 1920s, a narrative of unprecedented prosperity and growth prevailed. However, this prosperity was not evenly distributed. While wealth and luxury were ostensibly on display in the upper echelons of society, a significant portion of the American population lived in precarious economic conditions. The working class, although fundamental to industrial production and growth, was a marginal beneficiary of the wealth generated. This disproportion in the distribution of wealth instilled tensions and fissures within the economy. Consumption, a vital engine of economic growth, was undermined by the inadequacy of real wages for the majority of workers. Their ability to participate fully in the consumer economy was limited, creating a dynamic where overproduction and debt became increasingly prevalent. In this context, consumer confidence was fragile. Working class families, faced with rising living costs and stagnant wages, were vulnerable to economic shocks. When signs of an impending recession appeared, their ability to absorb and overcome the impact was limited. Their withdrawal from consumption exacerbated the economic slowdown, turning a moderate recession into a deep depression. The revelation of this wealth inequality had profound implications for economic and social policy. Gaps in the distribution of wealth were not simply social inequities, but economic flaws that could amplify boom and bust cycles. Recognition of the importance of economic justice, wage stability and worker protection became central to political and economic responses in the years following the Great Depression, shaping an era of reform and recovery.

The concentration of wealth in the hands of a narrow elite was not only a contributing factor to the crash of 1929, but also exacerbated the severity of the Great Depression that followed. Much of the nation's wealth was held by a small fraction of the population, creating a disparity that weakened the economic resilience of society as a whole. In an economy where consumption is a key driver of growth, the ability of the masses to purchase goods and services is crucial. The stagnation of real wages among workers and the middle class has reduced their purchasing power, leading to a contraction in demand. This reduction in demand has, in turn, affected production. Faced with falling sales, companies cut production and laid off workers, creating a vicious cycle of unemployment and falling consumption. The working and middle classes, deprived of sufficient financial resources, were unable to drive economic recovery. The ability of businesses to invest and expand was also hampered by the contraction in market demand. The profits and dividends accumulated by the wealthiest were not sufficient to stimulate the economy, as they were often not ploughed back into the economy in the form of consumption or productive investment. This highlighted a critical realisation: a fair distribution of wealth was not just a matter of social justice, but also an economic imperative. For an economy to be healthy and resilient, the benefits of growth must be widely shared to ensure robust demand and support production and employment. The response to the Great Depression, notably through the policies of the New Deal, reflected this realisation. Initiatives were launched to increase workers' purchasing power, regulate financial markets and invest in public infrastructure to create jobs. This marked a transition to a more inclusive vision of economic prosperity, where the distribution of wealth and opportunity was seen as a central pillar of economic stability and growth.

The Great Depression significantly reoriented the United States' approach to economic and social policy. The economic catastrophe exposed deep structural weaknesses and inequalities that had previously been largely ignored or underestimated. The need for proactive state intervention to stabilise the economy, protect the most vulnerable citizens and reduce inequalities became clear. The advent of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal marked a turning point in the American perspective on the role of government. While the dominant ideology prior to the Great Depression favoured laissez-faire and minimal government intervention, the crisis called this approach into question. It was clear that leaving it to the market alone was not enough to guarantee stability, prosperity and fairness. The New Deal, with its three-pronged strategy of relief, recovery and reform, was a multi-dimensional response to the crisis. Relief meant direct and immediate assistance for the millions of Americans facing poverty, unemployment and hunger. It was not only a humanitarian measure but also a strategy to revitalise consumer demand and stimulate the economy. The recovery focused on revitalising key sectors of the economy. Through massive public works projects and other initiatives, the government sought to create jobs, increase purchasing power and initiate an upward spiral of growth and confidence. Every dollar spent on building infrastructure or on wages was passed on to the economy, boosting consumption and investment. Reform, however, was perhaps the most enduring aspect of the New Deal. It was about structurally transforming the economy to prevent a repetition of the mistakes that had led to the Great Depression. This included tighter regulation of the financial sector, guaranteed bank deposits and policies to reduce economic inequality. In this way, the Great Depression and the response of the New Deal redefined the American social and economic contract. They highlighted the need for a balance between market freedom and government intervention, economic growth and equity, individual prosperity and collective well-being. This transformation shaped the trajectory of American politics and economics for decades to come.

- GDP depression.png

The general evolution of the depression in the United States, as reflected by GDP per capita (average income per person) in constant 2000 dollars, as well as some of the key events of the period.[8]

The mismatch between output growth and wage stagnation was one of the key factors that amplified the severity of the Great Depression. A thriving economy depends not only on innovation and production, but also on strong and sustainable demand, which requires a balanced distribution of income. If, in the 1920s, particular attention had been paid to the fair remuneration of workers and to ensuring that productivity gains were translated into higher wages, the country might have been better prepared to withstand a recession. Workers and families would have had more financial resources to maintain their spending, which could have cushioned the impact of the economic contraction. In other words, an economy whose prosperity is widely shared is more resilient. It can absorb economic shocks better than one where wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few. Consumer demand, fuelled by decent wages and a fair distribution of income, can sustain businesses and employment through difficult times. The premise is that every worker is not only a producer but also a consumer. If workers are well paid, they consume more, fuelling demand, which in turn supports production and employment. It's an economic ecosystem where production and consumption are in harmony. The crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression provided valuable lessons on the importance of this balance. The reforms and policies that followed have sought to restore and maintain this balance, although the challenge of economic inequality and pay equity remains a contemporary issue, reiterating the relevance of the lessons learned from that tumultuous period in economic history.

Price adjustment can be an effective mechanism for balancing supply and demand, especially in a context where consumer purchasing power is limited. A reduction in prices could, in theory, have stimulated consumption, thereby improving business liquidity and supporting the economy. In the context of the 1920s, the combination of increased production and stagnant wages created an imbalance where supply exceeded demand. More goods were being produced than the market could absorb, largely because consumers' purchasing power was limited by insufficient wages. By reducing prices, companies could have made their products more accessible, thereby stimulating demand and reducing the build-up of unsold inventories. However, it should be noted that this strategy also has its challenges. Reducing prices can erode companies' profit margins, potentially putting them in difficulty, especially if they are already vulnerable due to other economic factors. In addition, a generalised price cut, or deflation, can have perverse economic effects, such as encouraging consumers to delay purchases in the expectation of even lower prices, thereby exacerbating the economic slowdown. So, while reducing prices may be a viable strategy for increasing demand in the short term, it needs to be approached with caution and in the context of a wider economic strategy. It may be more beneficial to combine this approach with initiatives to increase consumer purchasing power, for example, by raising wages or introducing favourable tax policies, to create an environment where production and consumption are in dynamic equilibrium.

The climate at the time was characterised by excessive optimism, an unshakeable faith in the perpetual growth of the market and a reluctance to intervene in free market mechanisms. The Republican administrations of the time, rooted in laissez-faire principles, were reluctant to interfere in economic affairs. The prevailing philosophy was that markets would regulate themselves and that government intervention could do more harm than good. This ideology, while effective during economic booms, proved insufficient to prevent or mitigate the looming crisis. Similarly, many business and industrial leaders were trapped in a short-term vision, focused on maximising immediate profits rather than long-term sustainability. The euphoria of the economic boom often obscured the warning signs and underlying imbalances that were building up. The combination of overconfidence, inadequate regulation and a lack of corrective measures created a breeding ground for a crisis of devastating proportions. The crash of 1929 was not just an isolated event, but the result of years of accumulating economic and financial imbalances. The lesson learned from this tragic period was the recognition of the need for prudent regulation, a long-term view and preparation for economic instability. The policies and institutions that have emerged from the Great Depression, including greater regulatory oversight and a more active role for government in the economy, reflect an awareness of the complexity of economic systems and the need to balance growth, stability and equity.

The agricultural sector, although less glamorous than the booming stock markets and rapidly expanding industries, was a fundamental pillar of the economy and society. The First World War had led to a dramatic increase in demand for agricultural products, boosting production and prices. However, by the end of the war, global demand had contracted, but production remained high, leading to oversupply and falling prices. Farmers, many of them already operating on slim margins, found themselves in an increasingly precarious financial position. Mechanisation of agriculture also played a role, increasing production but also reducing demand for labour, contributing to the rural exodus. Farmers and rural workers migrated to cities in search of better opportunities, fuelling rapid urbanisation but also contributing to the saturation of the urban labour market. These rural dynamics were precursors and amplifiers of the Great Depression. When the stock market crash hit and the urban economy contracted, the agricultural sector, already weakened, was unable to act as a counterweight. Rural poverty and distress intensified, widening the scope and depth of the economic crisis. The recovery of the agricultural sector and the stabilisation of rural communities became essential elements of the recovery effort. New Deal initiatives such as farm legislation to stabilise prices, efforts to balance production with demand and investment in rural infrastructure were crucial components of the overall strategy to revitalise the economy and build a more resilient and balanced system.

The fallout from agricultural decline has not been confined to rural areas, but has affected the economy as a whole, creating a domino effect. The contraction of the agricultural sector has reduced not only farmers' incomes, but also those of businesses dependent on rural areas. Suppliers of agricultural materials and equipment, retailers and even the banks that had lent to farmers - all were affected. This contraction in rural demand has reduced incomes and employment in a variety of sectors, spreading economic distress far beyond farms and farming communities. Farmers' indebtedness, exacerbated by falling prices for agricultural products, has led to loan defaults and land seizures, affecting the stability of rural and urban financial institutions. Banks, already weakened by other factors, have been put under greater pressure. This cascading effect highlights the integrated and interdependent nature of the economy. Problems in one sector reverberate through others, creating a downward spiral that can be difficult to halt and reverse. In the context of the Great Depression, the decline of the agricultural sector was both a symptom and a catalyst for the wider economic collapse. Political and economic responses to the crisis had, of necessity, to take account of this complexity and interdependence. Intervention to stabilise and revitalise the agricultural sector was an integral part of the overall effort to restore the nation's economic health. Efforts to raise the price of agricultural products, support farmers' incomes and improve rural stability were intrinsically linked to restoring confidence, stimulating demand and achieving general economic recovery.

The distress of the rural population was a major catalyst for the reforms introduced under the New Deal. Farmers were among the hardest hit during the Great Depression. The combination of overproduction, falling crop prices, mounting debt and adverse weather conditions, such as those seen during the Dust Bowl, led to economic and social disaster in rural areas. The New Deal, initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, introduced a series of programmes and policies aimed specifically at alleviating distress in the agricultural sector. Measures such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act were implemented to raise agricultural commodity prices by controlling production. By paying farmers to reduce production, the government hoped to raise prices and improve farmers' incomes. Other initiatives, such as the creation of the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act, were put in place to provide loans to farmers threatened with foreclosure. This has helped to stabilise the agricultural sector, allowing farmers to keep their land and continue producing. In addition, the implementation of public works projects not only created jobs but also helped to improve rural infrastructure, connecting rural areas to urban markets and improving market access for agricultural products. These government interventions were unprecedented at the time and marked a radical change in the federal government's role in the economy. The New Deal not only brought immediate relief but also laid the foundations for structural reforms to prevent such an economic catastrophe from happening again in the future. It emphasised the importance of balancing the agricultural and industrial sectors and strengthened the role of the state as a regulator and stabiliser of the economy.

The inability of the Republican administrations of the time to effectively address the agricultural crisis had a marked effect on the country's demographic and economic dynamics. Laissez-faire economic policies largely ignored the growing distress in rural areas. Overproduction and the consequent fall in agricultural prices have plunged farmers into financial precariousness. Without adequate support and faced with debt and bankruptcy, many have been forced to leave their land. This situation has not only exacerbated economic distress in rural areas, but has also fuelled migration to the cities. Urban areas, although promising in terms of economic opportunities, have been swamped by an influx of workers seeking employment and economic security. This rapid migration has strained urban resources, exacerbating the challenges associated with providing housing, services and jobs. The urban labour market, already affected by the economic contraction, became saturated, contributing to rising unemployment and poverty. Against this backdrop, the Great Depression revealed and exacerbated the underlying structural weaknesses of the US economy and politics. It highlighted the imperative need for more dynamic government action and balanced attention to all sectors of the economy. The response in the form of the New Deal marked a turning point, not only in terms of specific policies but also in the perception of the role of government in the economy. The need for government intervention to stabilise the economy, regulate markets and support citizens in distress became an accepted part of American economic policy, shaping the political and economic landscape for decades to come.

The trend towards rapid urbanisation and the simultaneous weakening of the agricultural sector created a series of complex challenges that exacerbated the economic problems of the time. As the rural population declined, so did the demand for goods and services in these areas. Local businesses, dependent on demand from farmers and rural workers, suffered, leading to a spiral of economic decline. What's more, the influx of rural workers into the cities coincided with the stock market crash and the resulting economic contraction, increasing competition for already scarce jobs. Urban infrastructure, social services and housing markets were ill-prepared to handle such a rapid increase in population. This put additional pressure on urban resources and exacerbated problems of poverty and unemployment. The decline of the agricultural sector also had an impact on industry and financial services. Businesses that depended on agricultural demand, whether for agricultural machinery, chemicals or financial services, have also been affected. The growing indebtedness of farmers and payment defaults have affected the health of banks and financial institutions. The overall economic situation has been aggravated by a combination of factors, including reduced demand for agricultural products, indebtedness, the bankruptcy of rural businesses, and a growing urban population without adequate jobs. All these factors contributed to the depth and duration of the Great Depression. Roosevelt's New Deal subsequently attempted to tackle these interconnected problems through a series of programmes and reforms aimed at stabilising the economy, providing direct relief to those who suffered most, and reforming the economic and financial systems to prevent a repetition of such disasters in the future. The complexity and interdependence of the economic and social challenges of the time highlighted the need for coordinated, multi-faceted government action.

The problems of the agricultural sector, exacerbated by overproduction, falling prices and indebtedness, were largely neglected. This inaction, combined with the stock market crash of 1929, highlighted the inadequacies of the laissez-faire economic approach adopted at the time. The agricultural sector was a vital part of the American economy, and its deterioration had repercussions far beyond rural areas. Farmers, already financially weakened, were powerless to cope with the economic turmoil caused by the Great Depression. Reduced domestic demand, shrinking export markets and an inability to access credit exacerbated the crisis. The advent of the Roosevelt administration and the implementation of the New Deal marked a radical shift in government policy. For the first time, the federal government took significant steps to intervene in the economy, signalling a departure from the laissez-faire philosophy. Measures such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act were introduced to increase the price of agricultural products by reducing overproduction. Low-interest loans and subsidies were provided to help farmers keep their land and stay in business. In addition, public works projects were launched to create jobs and stimulate economic activity. So while initial inaction in the face of the agricultural and financial crises exacerbated the impacts of the Great Depression, subsequent New Deal interventions helped to alleviate some of the worst suffering, stabilise the economy and lay the foundations for lasting recovery and reform. These initiatives also redefined the role of the federal government in managing the economy and protecting the welfare of its citizens, a legacy that continues to influence American policy to this day.

The crash of 1929 and its consequences

The 1920s, often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties", were characterised by apparent prosperity and rapid economic growth. However, this growth was, to a large extent, unsustainable, as it was based on a massive expansion of credit and unbridled speculation. Easy credit and low interest rates encouraged a culture of spending and investment that exceeded the real means of consumers and investors. People were encouraged to live beyond their means, and overconfidence in continued growth fuelled a dangerous speculative bubble. The stock market became the centre of a speculative fever. Millions of Americans, from the richest to the poorest, invested their savings in the hope of quick gains. The belief that share prices would continue to rise indefinitely was a mirage that attracted people from all walks of life. However, the underlying economic reality did not support market euphoria. When confidence began to erode and the bubble burst, the market's rapid reversal triggered a panic. Investors sought to liquidate their positions, but with few buyers, share prices fell dramatically. This stock market crash had a domino effect, triggering a severe economic contraction. Consumer and investor confidence was severely shaken, leading to a reduction in spending and investment. Banks, also affected by the crisis and the ensuing panic, restricted credit, further exacerbating the recession. The Great Depression that followed was a moment of profound re-evaluation of the structure and regulation of the American economy. It underlined the dangers of unregulated speculation and excessive reliance on credit, and highlighted the need for a healthier balance between consumption, investment and sustainable economic growth. It has also paved the way for tighter government regulation to mitigate the risks and excesses that can lead to such crises.

The stock market craze and credit expansion masked deep structural weaknesses in the US economy. Overproduction, in particular, was a major problem not only in the industrial sector, where production outstripped demand, but also in the agricultural sector. Farmers, already struggling with low prices and falling incomes, were hit hard, exacerbating rural decline and economic misery. The unequal distribution of wealth was also a critical factor. A small elite enjoyed growing prosperity while the majority of Americans saw no significant improvement in their standard of living. This dynamic reduced aggregate demand, as a large proportion of the population could not afford to buy the goods that were being produced in abundance. When the speculative bubble in the stock market burst, these underlying weaknesses became apparent. Panic quickly set in, investors and consumers lost confidence in economic stability, and the country entered a downward spiral of economic contraction, rising unemployment and bankruptcies. The government's response and the introduction of the New Deal underlined the need for more robust government intervention to correct market imbalances and vulnerabilities. The programmes implemented sought not only to provide immediate relief, but also to initiate structural reforms aimed at building a more solid and equitable basis for future economic growth. This period marked a significant transformation in the conception and application of economic policy in the United States.

The stock market crash of 1929 was not an isolated event, but rather the most visible and immediate manifestation of a series of structural and systemic problems that had become entrenched in the US economy. Unbridled speculation, encouraged by easy access to credit and low interest rates, created an environment where thoughtful and prudent investment was often neglected in favour of quick profits. This focus on short-term profits not only fuelled the stock market bubble, but also diverted capital away from productive investments that could have supported sustainable economic growth. In addition, the lack of adequate regulation and government oversight left the market without effective safeguards against speculative excesses and risky financial practices. By failing to intervene actively, the government indirectly allowed unsustainable economic bubbles to form. When the stock market bubble burst, the underlying fragility of the economy was revealed. Banks and financial institutions were hit hard, and as credit tightened, businesses and consumers found themselves in a liquidity crunch. Confidence collapsed, and with it consumption and investment. The Great Depression called for a profound reconsideration of economic policies and a shift to greater government intervention to stabilise the economy, protect consumers and investors, and lay the foundations for more balanced and sustainable future growth. The lessons of that era continue to resonate in contemporary debates on economic regulation, the management of speculative bubbles and the role of government in promoting equitable and sustainable growth.

This crash was not just a temporary economic correction, but a catastrophic collapse that had profound and lasting repercussions for the global economy.

The rapid and severe decline in share values caught many investors off guard. The euphoria of the 'Roaring Twenties', when the market was booming and wealth seemed to be growing endlessly, quickly turned to despair and panic. Investors large and small saw the value of their portfolios plummet, eroding not only their personal assets but also their confidence in the financial system. The panic quickly spread beyond Wall Street. Banks, already weakened by bad loans and speculative investments, were hit by waves of panic withdrawals. Some were unable to cope with the sudden demand for liquidity and were forced to close their doors. This deepened the crisis, spreading mistrust and uncertainty throughout the economic system. The rapid loss of market value, combined with panic and investor withdrawal, marked the beginning of the Great Depression. The effects were felt far beyond the stock market, affecting businesses, workers and consumers across the country and, ultimately, the world. The financial collapse led to economic contraction, massive unemployment, corporate bankruptcies and widespread poverty and misery. The stock market crash prompted a thorough reappraisal of the financial system and its regulatory mechanisms. It provided a stark illustration of the dangers inherent in an unregulated and speculative market, and led to major reforms to strengthen the transparency, accountability and stability of the financial system, with the aim of preventing such a catastrophe from happening again in the future.

The collapse of banks and credit companies has been devastating. The banking system, in particular, is a pillar of the modern economy, facilitating the credit and investment necessary for economic growth. Its failure has exacerbated economic problems. The closure of banks has meant that many people and businesses have lost their savings and access to credit. In a world where credit is essential for everything from the day-to-day management of personal finances to the running and expansion of businesses, this collapse had far-reaching repercussions. Businesses were forced to scale back operations or close, leading to a rapid rise in unemployment. Uncertainty and fear led to a dramatic contraction in consumer spending. People, worried about their financial future, avoided unnecessary spending, contributing to a vicious circle of reduced demand, output and employment. This self-fulfilling recession was characterised by a reduction in demand, which in turn led to a reduction in production and even higher unemployment. The crisis also highlighted the fragility of the monetary and financial system and the importance of confidence in economic stability. Restoring this confidence has proved to be a long and difficult process, requiring in-depth reform and significant government intervention to stabilise the economy, reform the financial and banking system, and introduce safeguards to prevent future crises. This economic cataclysm ushered in an era of transformation, ushering in new and innovative economic policies, and redefining the relationship between government, the economy and citizens, with a renewed focus on regulation, social protection and economic equity.

The crash was a defining moment in the history of the Great Depression. It was not a short-lived crisis, but the prelude to an era of deep and persistent economic difficulties that affected almost every aspect of daily life. The breadth and depth of the Great Depression were unprecedented. The stock market crash exposed and exacerbated existing cracks in the economic fabric of the United States. Unemployment reached unprecedented levels, businesses failed at an alarming rate, and an atmosphere of despair and pessimism enveloped the nation. Every sector, from industry to agriculture, was affected, and images of queues of people waiting for food became striking symbols of the times. The stock market crash and subsequent Great Depression also led to a profound re-examination of economic and financial policies. The limitations and failures of laissez-faire and hands-off approaches were exposed. In response, there was a move towards greater regulation, government supervision and measures to increase transparency and financial stability. Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, for example, was not just a set of measures to respond to the immediate economic crisis, but also a revolution in the way government interacted with the economy. It introduced policies and institutions that continue to influence American economic policy to this day.

The Great Depression had a quantifiably catastrophic impact on the US economy, as some alarming figures show. Between 1929 and 1932, the United States' Gross National Product (GNP) fell drastically, by more than 40%. This monumental economic recession was amplified by a 50% drop in industrial production, a sector that had once flourished in the country. At the same time, the agricultural sector, the backbone of the US economy, was not left out. It contracted substantially, with falling output closely mirroring that of industry. These simultaneous declines in key sectors created a downward spiral in economic activity. Unemployment, a clear indicator of economic health, soared alarmingly. In 1929, around 1.5 million Americans were unemployed. By 1932, however, this figure had jumped to 12 million, signalling an unprecedented jobs crisis that transformed the economic and social landscape. Large-scale job loss led to a significant reduction in income for millions of households. The direct consequences of this loss of income have been rising homelessness, increased prevalence of hunger and escalating poverty. People's ability to access basic needs such as food, housing and healthcare was severely compromised, highlighting the depth of the unfolding economic crisis.