« Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 202 : | Ligne 202 : | ||

== The Order == | == The Order == | ||

The regime of Porfirio Díaz, known as the Porfiriato, was characterised by a strong desire for modernisation and economic progress. However, to achieve these ambitions, Díaz knew he had to maintain strict control over Mexican society. To achieve this, he adopted a series of strategies and tactics aimed at consolidating his power and minimising dissent. One of his main strategies was the "divide and rule" tactic. Díaz skilfully played factions off against each other, granting favours to some groups while repressing others. For example, he sometimes supported the interests of landowners while repressing peasant movements, or vice versa, depending on what best served his interests at any given time. At the same time, he adopted a "bread or stick" approach, rewarding loyalty and punishing dissent. Those who supported the Díaz regime could expect favours, government posts or economic concessions. On the other hand, those who opposed him often faced repression, imprisonment or even exile. Control of the media was also crucial for Díaz. He exercised strict control over the media, censoring critical voices and promoting a positive image of his regime. Newspapers that supported him were favoured with government subsidies, while those that criticised him were often closed down or their editors intimidated. Militarisation was another pillar of his regime. Díaz strengthened the army and police, using them as tools to maintain order and suppress dissent. Particularly turbulent areas were often placed under martial law, with troops deployed to guarantee stability. In addition, Díaz's government had a network of spies and informers who monitored the activities of citizens, particularly those of opposition groups and activists. Finally, economic concessions played an essential role in maintaining his power. Díaz often used economic concessions as a means of winning the support of local and foreign elites. By granting exclusive rights to certain resources or industries, he secured the loyalty of these powerful groups. By combining these tactics, the Porfirian regime managed to maintain firm control over Mexico for more than three decades. However, this repression and inequality eventually led to widespread discontent, which erupted in the form of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. | |||

Porfirio Díaz's regime skilfully used the principle of 'divide and rule' as a strategic tool to maintain its grip on power. By creating or exacerbating existing divisions within Mexican society, Díaz was able to weaken and fragment any potential opposition, making it more difficult to form a unified coalition against him. Regions that showed particular loyalty to the regime were often favoured with investments, infrastructure projects or other economic benefits. On the other hand, regions perceived as less loyal or potentially rebellious were often neglected or even punished with punitive economic measures. This approach created regional disparities, with some regions enjoying significant economic development while others languished in poverty. Within the working class, Díaz often played the interests of urban workers against those of rural workers. By offering advantages or concessions to one group while neglecting or repressing the other, he was able to prevent the formation of a unified workers' front that could challenge his rule. Similarly, Mexico's indigenous communities, which had already been marginalised for centuries, were further divided under the Díaz regime. By favouring certain communities or indigenous leaders while repressing others, Díaz created divisions and rivalries within the indigenous population, making it more difficult for them to unite against the regime. Using these tactics, Díaz was able to weaken the opposition, strengthen his own power and maintain firm control over Mexico for more than three decades. However, these divisions and inequalities ultimately contributed to the instability and discontent that led to the Mexican Revolution. | |||

Under the regime of Porfirio Díaz, the principle of "bread or stick" became a central element of governance. This dualistic strategy enabled Díaz to maintain a delicate balance between the carrot and the stick, guaranteeing the loyalty of some while discouraging opposition from others. Incentives, or 'bread', were often used to win the support of key groups or influential individuals. For example, land, government jobs or lucrative contracts could be offered to those prepared to support the regime. These rewards not only ensured the loyalty of many individuals and groups, but also served as an example of the benefits of cooperating with the Díaz regime. However, for those who were not seduced by these incentives or who actively chose to oppose the regime, Díaz did not hesitate to use the "stick". Repression was brutal for those who dared to challenge the regime. Demonstrations were often violently repressed, opposition leaders were arrested or exiled, and in some cases entire communities suffered reprisals for the actions of a few. The army and police, strengthened and modernised under Díaz, were the main instruments of this repression. This combination of incentives and repression enabled Díaz to consolidate his power and govern Mexico for more than three decades. However, this approach also sowed the seeds of discord and discontent, which would eventually erupt in the form of the Mexican Revolution, bringing the era of the Porfiriato to an end. | |||

The regime of Porfirio Díaz, although often praised for its efforts at modernisation and industrialisation, was also marked by strong political repression and restrictions on civil liberties. Stability and order were top priorities for Díaz, and he was prepared to take draconian measures to maintain them. Censorship was omnipresent. Newspapers, magazines and other publications were closely monitored, and any content deemed subversive or critical of the government was quickly suppressed. Journalists who dared to criticise the regime were often harassed, arrested or even exiled. This censorship was not limited to the print media; public gatherings, plays and even some forms of art were also subject to government scrutiny and censorship. Propaganda was another key tool used by the regime to shape public opinion. Díaz's government promoted an image of stability, progress and modernity, often in contrast to previous regimes, which were portrayed as chaotic and regressive. This propaganda was omnipresent, from school textbooks to newspapers and public speeches. Surveillance was also commonplace. Government intelligence services kept a close eye on the activities of citizens, particularly those of groups considered 'problematic' or 'subversive'. Indigenous communities, trade unions, opposition political groups and others were often infiltrated by government informers. Repression was most severe for those who dared to openly challenge the regime. Strikes were brutally suppressed, trade union and political leaders were arrested or murdered, and communities that opposed the government were often collectively punished.[[File:Rurales.jpg|thumb|A detachment of Rurales in campaign uniform during the Diaz era.]] | |||

The Porfirian regime's "bread or stick" approach to maintaining order and controlling society was aimed primarily at the elite and the pillars of the regime, such as the army and the church. The regime offered incentives or rewards, such as jobs, land or other benefits, to those who supported it and were prepared to cooperate with it. The aim was to "buy" the support of certain members of the elite and prevent them from opposing the regime. On the other hand, those who refused to cooperate or who were perceived as a threat to the regime were dealt with severely. The "stick" represented repression, force and punishment. The army and police were used to suppress all opposition, whether real or perceived. Dissidents were often arrested, tortured, exiled or even executed. Property could be confiscated and the families of opponents persecuted. The Church, as a powerful and influential institution in Mexico, was another important pillar of the regime. Díaz understood the importance of maintaining good relations with the Church to ensure the stability of his regime. Although relations between the state and the Church were strained at times, Díaz often sought to cooperate with the Church and secure its support. In return, the Church enjoyed privileges and protections under Díaz. Ultimately, the "bread or stick" approach was a way for Díaz to consolidate his power and maintain control over Mexico. By offering rewards and incentives to those who supported him and severely punishing those who opposed him, Díaz managed to maintain relative stability for most of his reign. However, this approach also sowed the seeds of discontent and revolution, as many Mexicans felt oppressed and marginalised by Díaz's authoritarian rule. | |||

Díaz's strategy for maintaining control in rural areas was simple but effective: he used brute force to crush any form of resistance. The rurales, a paramilitary force created by Díaz, were often deployed in these areas to monitor and control local communities. They were feared for their brutality and lack of accountability, and were often involved in acts of violence against the civilian population. Indigenous communities, in particular, were hard hit by these repressive tactics. Historically marginalised and oppressed, these communities had their land confiscated and were often forced to work in slave-like conditions in the haciendas of large landowners. Any attempt at resistance or revolt was brutally suppressed. Indigenous traditions, languages and cultures were also often targeted in an attempt to assimilate and "civilise" them. The working class was not spared repression either. With the industrialisation and modernisation of Mexico under Díaz, the working class grew, particularly in the cities. However, working conditions were often precarious, wages low and workers' rights almost non-existent. Strikes and demonstrations were common, but were often violently repressed by the army and police. | |||

Díaz | Díaz knew that the regular army, with its diverse loyalties and regional affiliations, might not be entirely reliable in a crisis. The "rurales", on the other hand, were a specially trained force loyal directly to Díaz and his regime. They were often recruited from among veterans and trusted men, which guaranteed their loyalty to the president. The "rurales" were feared for their brutal efficiency. They were often used to suppress resistance movements, hunt down bandits and maintain order in areas where central government control was weak. Their presence was a constant reminder of the reach and power of the Díaz regime, even in the most remote parts of the country. In addition, Díaz used the "rurales" as a counterweight to the regular army. By maintaining a powerful and loyal parallel force, he could ensure that the army would not become too powerful or threaten his regime. It was a clever strategy for balancing power and preventing coups d'état or internal rebellion. However, the creation and use of "rurales" also had negative consequences. Their brutality and lack of accountability often led to abuses against the civilian population. Moreover, their presence reinforced the authoritarian nature of the Díaz regime, where force and repression were often favoured over dialogue or negotiation. | ||

Porfirio Díaz | Porfirio Díaz was an astute political strategist, and he understood the crucial importance of the army for the stability of his regime. The army, as an institution, had the potential to overthrow the government, as had been the case in many other Latin American countries at the time. Díaz, aware of this threat, took steps to ensure the army's loyalty. Increasing pay and benefits was a direct way of winning the loyalty of soldiers and officers. By offering better pay and improved living conditions, Díaz ensured that the army had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. What's more, by modernising the army with new weapons and equipment, he strengthened not only the army's ability to maintain order, but also its prestige and status within Mexican society. The presence of the "rurales" added another dimension to Díaz's strategy. By maintaining a powerful parallel force, he could play on the competition between the two groups. If the regular army became too ambitious or threatening, Díaz could rely on the "rurales" to counterbalance this threat. Conversely, if the "rurales" became too powerful or independent, Díaz could rely on the regular army. This "divide and rule" strategy was effective for Díaz for most of his reign. It prevented coups and maintained a delicate balance between the different factions of military power. However, this approach also reinforced the authoritarian nature of the regime, with an increased reliance on military force to maintain order and control.[[File:Uprising_of_Yaqui_Indians_Remington_1896.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Yaqui uprising - Retreating Yaqui warriors, by Frederic Remington, 1896.]] | ||

Porfirio Diaz a | Porfirio Diaz maintained a cautious and pragmatic relationship with the Catholic Church during his regime. He did not officially reform the constitution to remove the anti-clerical provisions of the liberal constitution of 1857, but preferred to ignore them. Diaz returned to the Catholic Church the monasteries and religious schools that had been confiscated under the previous liberal regime, and allowed the Church to continue to play an important role in society. In return, the Catholic Church supported the Díaz regime, preaching stability and order and discouraging dissent. This pragmatic alliance between state and church benefited both sides. For Díaz, it allowed him to consolidate his power and gain the support of a powerful and influential institution. For the Church, it allowed it to regain some of the influence and property that had been lost during earlier periods of reform. However, this relationship was not without its tensions. Although Díaz allowed the Church to regain some of its influence, he ensured that it did not become too powerful or threaten his regime. He maintained strict control over education, ensuring that the state had the final say on what was taught in schools, and limited the power of the Church in other areas of society. | ||

The Catholic Church, with its deep influence and historical roots in Mexico, was a major player in the country's social and political dynamics. Recognising this, Díaz saw the importance of maintaining a peaceful relationship with the Church. By avoiding open conflict with the Church, Díaz was able to avoid a potential source of dissent and opposition to his regime. The Church, for its part, had its own reasons for supporting Díaz. Having suffered significant losses in terms of property and influence under previous liberal regimes, it was keen to protect its interests and regain some of its power and influence. By supporting Díaz, the Church was able to operate in a more favourable environment, where it could continue to play a central role in the lives of Mexicans. This mutually beneficial arrangement contributed to the stability of the Díaz regime. However, it is also important to note that, although the Church supported Díaz, it also maintained a certain distance from the government, thereby preserving its institutional independence. This allowed the Church to continue to play a central role in the lives of Mexicans, while avoiding being too closely associated with the excesses and controversies of the Porfirian regime. | |||

The agreement between Díaz and the Catholic Church was not without consequences. For many critics, the fact that the Church was able to operate without hindrance meant that it had a disproportionate influence on Mexico's political and social life. The Church, with its vast resources and influence, was able to influence political decisions, often to the detriment of the separation of church and state, a fundamental principle of liberal democracy. The suppression of religious freedoms was another concern. Although the Catholic Church enjoyed greater freedom under Díaz, other religious groups were often marginalised or persecuted. This created an environment where religious freedom was limited, and the Catholic Church had a de facto monopoly on religious life. Education was also affected. With the Church playing a greater role in education, there were concerns about curriculum and teaching. Critics argued that education had become less secular and more oriented towards the teachings of the Church. This had implications for the development of critical and independent thinking among students. Finally, the Church's support for Díaz was seen by many as a betrayal. The Church, as an institution that was supposed to defend moral and ethical values, supported a regime that was often criticised for its repression and abuses. For many Mexicans, this discredited the Church as an institution and reinforced the idea that it was more concerned with power and influence than with the well-being of its faithful. | |||

Porfirio Díaz a | Porfirio Díaz skilfully navigated Mexico's political and economic landscape to consolidate his power. His policy of selective repression was a deliberate strategy to balance the needs and desires of the economic elites while neutralising potential threats to his authority. Large landowners, bankers and entrepreneurs were essential to Mexico's economic growth and the stability of the Díaz regime. By allowing them to prosper, Díaz ensured their support and loyalty. These economic elites enjoyed a stable environment for their investments and businesses, and in return they supported the Díaz regime, both financially and politically. However, Díaz was well aware that these same elites, with their vast resources and influence, could potentially become a threat to his power if they became dissatisfied or saw an opportunity to gain more power for themselves. So, while allowing them to prosper, Díaz also put mechanisms in place to ensure that they did not become too powerful or politically influential. He kept a close eye on them, making sure they didn't form alliances that could threaten him. On the other hand, those who openly opposed Díaz or posed a threat to his regime, such as trade union activists, critical journalists or dissident political leaders, were often the targets of his repression. They were arrested, imprisoned, exiled or sometimes even killed. This selective repression sent a clear message to Mexican society: support for Díaz was rewarded, while opposition was severely punished. | ||

Porfirio Díaz | Porfirio Díaz mastered the art of transactional politics. By offering land, concessions and other benefits to his allies, he created a system of loyalty that strengthened his regime. These rewards were powerful incentives for Mexico's economic elite, encouraging them to support Díaz and invest in the country. In return, they enjoyed a stable business environment and protection from competition or territorial claims. However, this generosity was not without conditions. Díaz expected unwavering loyalty from his allies. Those who betrayed that trust or appeared to oppose him were quickly targeted. Repression could take many forms, from confiscation of property to imprisonment and even execution. This combination of carrot and stick was effective in maintaining order and stability for most of his reign. In addition, by selectively distributing land and concessions, Díaz was also able to control the concentration of economic power. By fragmenting wealth and resources, he ensured that no individual or group became powerful enough to challenge his authority. If an individual or family became too influential, Díaz had the means to reduce them to a more manageable size. This strategy was essential in maintaining the balance of power in Mexico during the Porfiriato. While it allowed for some economic stability and growth, it also created deep inequalities and sowed the seeds of discontent. Díaz's reliance on these tactics ultimately contributed to the instability and revolution that followed the end of his regime. | ||

The massive expansion of infrastructure under Porfirio Díaz required a larger and more efficient state administration. The bureaucracy grew at an unprecedented rate during this period, with the creation of numerous civil service posts to oversee, manage and maintain infrastructure projects. The expansion of the rail network is a particularly striking example of this bureaucratic growth. Railways not only developed as transport routes for goods and people, they also became a strategic tool for the government. With an extensive rail network, the government could quickly move troops to quell rebellions or unrest in remote areas, reinforcing Díaz's centralised control over the vast Mexican territory. To manage this complex network, numerous positions were created, ranging from engineers and technicians responsible for designing and maintaining the tracks, to administrators overseeing operations and logistics. In addition, the rail network has necessitated the creation of a rail police force to guarantee the safety of the tracks and stations, as well as to protect property and passengers. State expansion has not been limited to the railways. Other infrastructure projects, such as the construction of ports, roads, dams and irrigation systems, also required an expanded state administration. These projects created employment opportunities for a new class of trained and educated civil servants, who became essential to Porfiriato's state machinery. | |||

The ability to respond quickly to unrest was a key part of Díaz's strategy for maintaining his grip on Mexico. Before the expansion of the railway network, Mexico's vast territory, with its difficult terrain and long distances, made it difficult for the central government to respond quickly to rebellions or uprisings. Revolts could last for months, or even years, before the government could mobilise enough troops to put them down. With the advent of the railways, this dynamic changed. Troops could be moved quickly from one region to another, enabling a rapid response to any insurrection. This not only enabled rebellions to be effectively suppressed, but also acted as a deterrent, as potential rebels knew that the government could quickly send reinforcements. In addition, the railway network enabled better communication between the different regions of the country. Information about rebel movements, unrest or potential threats could be quickly transmitted to the capital, allowing Díaz's government to plan and coordinate its responses. However, this increased capacity for repression also had negative consequences. It reinforced the authoritarian nature of the Díaz regime, with an increased reliance on military force to maintain order. Many Mexicans became dissatisfied with this constant repression, which contributed to the build-up of tension and discontent that eventually led to the Mexican Revolution of 1910. | |||

The situation of the Yaquis during the Porfirian regime is a poignant example of the tensions and conflicts that emerged in response to Díaz's policies of modernisation and centralisation. The Yaquis, originally from the Yaqui river valley in the state of Sonora, had a long history of resistance to Spanish and later Mexican rule. Under the Díaz regime, the pressure to develop and modernise the country led to an increase in demand for land for agriculture and livestock, particularly in rich and fertile regions such as the Yaqui. The land in the Yaqui valley was particularly sought after for its fertility and access to water, both of which were essential to support large-scale agriculture. The Díaz government, in collaboration with private landowners, began expropriating land from the Yaquis, often by coercive or fraudulent means. These actions displaced many Yaquis from their ancestral lands, disrupting their traditional way of life based on agriculture and fishing. In response to these expropriations, the Yaquis resisted in every way possible. They launched several revolts against the Mexican government, using guerrilla tactics and seeking to reclaim their land. Díaz's government responded with brutal force, launching military campaigns to suppress Yaqui resistance. These campaigns were often accompanied by violence, forced displacement and, in some cases, the expulsion of Yaquis from their homeland to henequén plantations in the Yucatán or other remote areas of the country, where they were often subjected to slave-like working conditions. The resistance of the Yaquis and the brutal repression by the government became emblematic of the wider tensions that emerged in Mexico during the Porfirian regime. Although the Díaz regime brought a degree of stability and modernisation to the country, it often did so at the expense of indigenous and rural communities, who paid a heavy price in terms of land, culture and human lives. | |||

The Díaz government's response to the Yaquis uprisings is a grim example of the regime's treatment of dissidents and ethnic minorities. Military repression was brutal, and communities that resisted were often subjected to extreme violence. Massacres were common, and survivors, rather than simply being released, were often forcibly moved to remote parts of the country. The deportation of the Yaquis to the Yucatán peninsula is one of the most tragic episodes of this period. In Yucatán, demand for labour for the henequén plantations was high. Henequén, also known as sisal, was a lucrative crop used to make rope and other products. Working conditions on these plantations were appalling, with long and exhausting working days, poor living conditions and little or no pay. The deported Yaquis were often treated like slaves, working in inhumane conditions with no possibility of returning home. For the Díaz regime and the plantation owners, it was a win-win situation: the government got rid of a rebel group, and the plantation owners got cheap labour. These actions have been widely criticised, both then and now, for their brutality and lack of humanity. They are an example of how the Díaz regime, despite its efforts at modernisation and development, often acted at the expense of the most vulnerable groups in Mexican society. | |||

The scale of the deportation of the Yaquis is staggering and demonstrates the brutality of the Díaz regime towards indigenous groups who resisted his rule. The mass deportation of the Yaquis was not only a punitive measure, but also a lucrative business for the officials and plantation owners involved. The fact that the Yucatán planters paid for each Yaqui deported shows the extent to which this operation was systematised and commercialised. The colonel, as intermediary, received a commission for each Yaqui deported, while the rest of the money went directly to the War Ministry. This shows that the deportation of the Yaquis was not only a strategy to eliminate potential resistance, but also a way for the Díaz regime to generate revenue. The deportation of the Yaquis to Yucatán had devastating consequences for the community. Many died as a result of the inhumane working conditions on the henequén plantations, while others succumbed to disease. The culture and identity of the Yaquis were also severely affected, as they were uprooted from their homeland and dispersed to a foreign region. This tragedy is an example of how the Díaz regime has often prioritised economic and political interests over the rights and well-being of Mexico's indigenous peoples. It is a sombre reminder of the consequences of Díaz's policy of "modernisation" when implemented without regard for human rights and social justice. | |||

The policy of deportation and forced labour implemented by the Díaz regime against the Yaquis is a glaring example of the exploitation and marginalisation of indigenous peoples in Mexico during this period. The Yaquis, like many other indigenous groups, were seen as obstacles to the progress and modernisation that Díaz sought to bring about. Their resistance to the confiscation of their lands and government interference in their affairs was met with brutal force and systematic repression. The deportation of the Yaquis was not only a punitive measure, but also an economic strategy. By moving them to Yucatán, the Díaz regime was able to provide cheap, exploitable labour for the henequén plantations, while simultaneously weakening Yaqui resistance in the north. This dual motivation - political and economic - made the deportation all the more cruel and ruthless. The destruction of Yaqui communities, culture and traditional ways of life had lasting consequences. Not only did it uproot a people from their ancestral land, it also erased part of Mexico's indigenous history and culture. The loss of land, which is intrinsically linked to the identity and spirituality of indigenous peoples, was a devastating blow to the Yaquis. Díaz's policy towards the Yaquis was just one example of his regime's treatment of indigenous peoples and other marginalised groups. Although the Díaz regime was hailed for its economic achievements and modernisation of Mexico, it was also responsible for serious human rights violations and social injustices. These policies, and others like them, sowed the seeds of discontent that would eventually culminate in the Mexican Revolution of 1910. | |||

The Porfirio period, although marked by economic modernisation and relative stability, was also characterised by severe repression of all forms of dissent. The regime of Porfirio Díaz was determined to maintain order and stability at all costs, even if this meant violating the fundamental rights of its citizens. Workers, particularly those in the mining and infant industries, were often faced with dangerous working conditions, long hours and poor pay. When they tried to organise strikes or demonstrations to demand better pay or working conditions, they were often met with brutal violence. The strikes in Cananea in 1906 and Rio Blanco in 1907 are notable examples of how the regime responded to labour dissent with force. In both cases, the strikes were violently repressed by the army, leaving many workers dead or injured. Political opponents, be they liberals, anarchists or others, were also targeted. Newspapers and publications critical of the regime were often censored or closed down, and their editors and journalists were arrested or exiled. Elections were rigged, and those who dared to run against Díaz or his allies were often intimidated or even eliminated. Indigenous communities, such as the Yaquis, were particularly vulnerable to repression. In addition to deportations and massacres, many communities saw their land confiscated in favour of large landowners or foreign companies. These actions were often justified in the name of progress and modernisation, but had devastating consequences for the communities affected. | |||

The regime of Porfirio Díaz, although often praised for its modernisation of Mexico, was also marked by severe political repression. Stability, often referred to as "Paz Porfiriana", was maintained largely by suppressing dissenting voices and eliminating potential threats to Díaz's power. Political opponents, whether radical liberals, critical journalists, activists or even members of the elite who disagreed with Díaz's policies, often faced serious consequences. Arbitrary arrests were commonplace, and Mexican prisons at the time were full of political prisoners. Many were held without trial, and torture in custody was not uncommon. Exile was another tactic commonly used by the Díaz regime. Many political opponents were forced to leave the country to escape persecution. Some continued to oppose the regime from abroad, organising opposition groups or publishing critical writings. Censorship was also omnipresent. Newspapers and publishers that dared to criticise the government were closed down or pressured to moderate their tone. Journalists who did not comply were often arrested or threatened. This censorship created an environment where the media were largely controlled by the state, and where criticism of the government was rarely, if ever, heard. This climate of fear and intimidation had a paralysing effect on Mexican society. Many were afraid to speak out against the regime, to take part in demonstrations or even to discuss politics in private. The repression also prevented the emergence of an organised political opposition, as opposition groups were often infiltrated by government informers and their members arrested. | |||

The longevity of the Porfirio Díaz regime is impressive. However, despite his ability to hold on to power for so long, a series of internal and external factors eventually led to his downfall. One of the major problems was socio-economic inequality. Despite significant economic growth, the fruits of this prosperity were not distributed equitably. A small elite held much of the country's land and wealth, leaving the majority of the population poor and landless. This growing inequality fuelled discontent among the working classes. Political repression was another key factor. Díaz constantly suppressed freedom of expression and political opposition, creating a climate of mistrust and fear. However, this repression also led to an underground opposition and resistance that sought ways to overthrow the regime. In addition, the confiscation of communal land and its handover to private landowners or foreign companies provoked the anger of rural and indigenous communities, making land reform a central issue. The growing influence of foreign investment, particularly from the United States, has also been a source of concern. Mexico's dependence on such investment has raised concerns about national sovereignty and fuelled anti-imperialist sentiment. At the same time, although the Díaz regime experienced periods of economic growth, it also went through periods of recession, which exacerbated social tensions. Social and cultural changes also played a role. Education and modernisation led to the emergence of a middle class and an intelligentsia that increasingly disagreed with Díaz's authoritarian policies. Moreover, in 1910, Díaz, then aged over 80, sparked speculation about his succession, leading to power struggles within the ruling elite. His decision to stand for re-election, despite an earlier promise not to do so, and the subsequent allegations of electoral fraud, were the catalyst that sparked the Mexican Revolution. | |||

Firstly, there was the growing discontent of the working classes and peasants, due to the concentration of land ownership and the suppression of labour rights. The gap between the rich elite and the poor majority was widening, and many Mexicans were struggling to make a living. In addition, the lack of political representation and the suppression of dissent led to public frustration and anger. Secondly, foreign influence, particularly from the United States, in the Mexican economy was a source of tension. Foreign investors owned large swathes of land, mines, railways and other key infrastructure. Although these investments contributed to Mexico's modernisation, they also reinforced the feeling that the country was losing its economic autonomy and sovereignty. Many Mexicans felt that the benefits of these investments went mainly to foreign interests and a national elite, rather than to the population as a whole. Thirdly, Díaz's policy on relations with the Catholic Church also played a role. Although Díaz adopted a pragmatic approach, allowing the Church to regain some of its influence in exchange for his support, this relationship was criticised by radical liberals who felt that the Church had too much influence, and by conservatives who felt that Díaz did not go far enough in restoring the Church's power. Finally, the very nature of Díaz's authoritarian regime was itself a source of tension. By suppressing freedom of the press, imprisoning opponents and using force to suppress demonstrations and strikes, Díaz created a climate of fear and mistrust. While these tactics may have maintained order in the short term, they also sowed the seeds of revolt. When tensions finally boiled over, they led to a revolution that ended nearly thirty years of Díaz rule and transformed Mexico for decades to come. | |||

Under Porfirio Diaz, Mexico faced a series of challenges that eventually led to his downfall. One of the main problems was the country's economic dependence on exports of raw materials. Although these exports initially stimulated economic growth, they also left the country vulnerable to fluctuations in world markets. When demand for these raw materials plummeted, the Mexican economy was hit hard, leading to economic stagnation and growing discontent among the population. Diaz's handling of law and order was also a source of tension. His brutal response to strikes and political opposition not only provoked anger, but also reinforced the idea that the regime was oppressive and indifferent to the needs and rights of its citizens. The situation of indigenous peoples, forced into migration and forced labour, was particularly tragic. These actions not only destroyed entire communities, but also reinforced the feeling that the Diaz regime was putting economic interests ahead of human rights. Finally, the longevity of Diaz's rule and his blatant manipulation of the electoral system have eroded any illusion of democracy in Mexico. After more than three decades in power, many Mexicans were frustrated by the lack of political renewal and the feeling that Diaz was more of a dictator than a democratically elected president. This growing discontent, combined with the other challenges facing the country, created an environment conducive to revolution and change. | |||

The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, was a direct response to the many years of authoritarianism and socio-economic inequality under the regime of Porfirio Díaz. It was fuelled by the growing discontent of various sectors of Mexican society, ranging from the oppressed working and peasant classes to intellectuals and the middle classes who aspired to genuine democracy and land reform. Francisco Madero, a wealthy landowner and opponent of Díaz, was one of the first to openly challenge the regime. After being imprisoned for contesting the 1910 elections, he called for an armed revolt against Díaz. What began as a series of local uprisings quickly developed into a full-fledged revolution, with various revolutionary leaders, such as Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, joining the cause with their own armies and agendas. The revolution was marked by a series of battles, coups and changes of leadership. It saw the rise and fall of several governments, each with its own vision of what a post-porfirien Mexico should be. Emiliano Zapata, for example, advocated radical land reform and the return of land to peasant communities, while other leaders had different visions for the country's future. After a decade of conflict and instability, the revolution finally led to the promulgation of the 1917 Constitution, which established the framework for modern Mexico. This constitution incorporated numerous social and political reforms, such as land reform, workers' rights and public education, while limiting the power and influence of the Church and foreign corporations. | |||

= | = The First Republic of Brazil: 1889 - 1930 = | ||

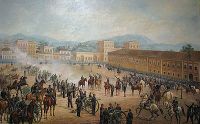

[[File:Benedito Calixto - Proclamação da República, 1893.jpg|thumb|left|200px| | [[File:Benedito Calixto - Proclamação da República, 1893.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The proclamation of the Republic, by Benedito Calixto.]] | ||

La fin de l'esclavage en 1888 avec la "Lei Áurea" (Loi d'Or) a posé un défi majeur à l'économie brésilienne, en particulier dans les secteurs du café et de la canne à sucre qui dépendaient fortement de la main-d'œuvre esclave. Avec l'abolition, l'élite brésilienne a dû trouver des moyens de remplacer cette main-d'œuvre. L'une des solutions adoptées a été d'encourager l'immigration européenne, principalement d'Italie, du Portugal, d'Espagne et d'Allemagne. Ces immigrants étaient souvent attirés par la promesse de terres et d'opportunités, et ils sont venus en grand nombre pour travailler dans les plantations de café de l'État de São Paulo et d'autres régions. L'immigration a également été encouragée pour "blanchir" la population, car il y avait une croyance répandue parmi l'élite que les immigrants européens apporteraient une "amélioration" à la composition raciale et culturelle du Brésil. La transition vers la République en 1889 a également marqué un tournant dans la politique brésilienne. La nouvelle constitution a cherché à centraliser le pouvoir, réduisant l'autonomie des provinces. Cela a été fait dans le but de moderniser le pays et de le rendre plus compétitif sur la scène internationale. Le nouveau régime républicain a également cherché à promouvoir l'industrialisation, en encourageant les investissements étrangers et en modernisant les infrastructures, telles que les chemins de fer et les ports. Cependant, malgré ces efforts de modernisation, la République a été marquée par des inégalités socio-économiques persistantes. L'élite terrienne et industrielle a continué à dominer la politique et l'économie, tandis que la majorité de la population, y compris les anciens esclaves et les travailleurs ruraux, est restée marginalisée. De plus, la politique sous la Première République (1889-1930) a été caractérisée par le "coronelismo", un système dans lequel les "coronéis" (chefs locaux) exerçaient un contrôle quasi féodal sur les régions rurales, en échange de leur soutien au gouvernement central. | La fin de l'esclavage en 1888 avec la "Lei Áurea" (Loi d'Or) a posé un défi majeur à l'économie brésilienne, en particulier dans les secteurs du café et de la canne à sucre qui dépendaient fortement de la main-d'œuvre esclave. Avec l'abolition, l'élite brésilienne a dû trouver des moyens de remplacer cette main-d'œuvre. L'une des solutions adoptées a été d'encourager l'immigration européenne, principalement d'Italie, du Portugal, d'Espagne et d'Allemagne. Ces immigrants étaient souvent attirés par la promesse de terres et d'opportunités, et ils sont venus en grand nombre pour travailler dans les plantations de café de l'État de São Paulo et d'autres régions. L'immigration a également été encouragée pour "blanchir" la population, car il y avait une croyance répandue parmi l'élite que les immigrants européens apporteraient une "amélioration" à la composition raciale et culturelle du Brésil. La transition vers la République en 1889 a également marqué un tournant dans la politique brésilienne. La nouvelle constitution a cherché à centraliser le pouvoir, réduisant l'autonomie des provinces. Cela a été fait dans le but de moderniser le pays et de le rendre plus compétitif sur la scène internationale. Le nouveau régime républicain a également cherché à promouvoir l'industrialisation, en encourageant les investissements étrangers et en modernisant les infrastructures, telles que les chemins de fer et les ports. Cependant, malgré ces efforts de modernisation, la République a été marquée par des inégalités socio-économiques persistantes. L'élite terrienne et industrielle a continué à dominer la politique et l'économie, tandis que la majorité de la population, y compris les anciens esclaves et les travailleurs ruraux, est restée marginalisée. De plus, la politique sous la Première République (1889-1930) a été caractérisée par le "coronelismo", un système dans lequel les "coronéis" (chefs locaux) exerçaient un contrôle quasi féodal sur les régions rurales, en échange de leur soutien au gouvernement central. | ||

Version du 28 septembre 2023 à 11:01

Based on a lecture by Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

The Americas on the eve of independence ● The independence of the United States ● The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society ● The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas ● The independence of Latin American nations ● Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies ● The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery ● The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877 ● The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900 ● Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910 ● The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940 ● American society in the 1920s ● The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940 ● From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy ● Coups d'état and Latin American populisms ● The United States and World War II ● Latin America during the Second World War ● US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty ● The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution ● The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

At the turn of the twentieth century, Latin America was marked by regimes advocating "Order and Progress". Inspired by positivism and the ideals of modernisation, these regimes, often led by authoritarian rulers, sought to industrialise their nations, stimulate economic growth and establish robust centralised power. While promoting laudable initiatives such as modernising infrastructure and improving public services, these regimes have also been synonymous with political repression, human rights abuses, and a concentration of power and wealth within a narrow elite.

Mexico is a case in point. Under the rule of Porfirio Díaz, from 1876 to 1910, the country underwent rapid modernisation, building railways and attracting foreign investment. However, this era, known as the Porfiriato, was also marked by growing inequality, harsh repression and human rights abuses, fuelling discontent that culminated in the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920.

This period was also influenced by Western ideologies, notably racism and social Darwinism. These beliefs were often used to justify the exploitation of marginalised groups such as indigenous peoples and Afro-Latin Americans. These ideologies reinforced exploitative practices, such as forced labour, even after the formal abolition of slavery.

Economic liberalism, although it advocates minimal state intervention, has in fact manifested itself in Latin America with the active support of the state, favouring large landowners and industrialists. At the same time, migration policies were put in place to encourage European immigration, with the aim of "whitening" the population, reflecting the racial prejudices of the time and the interests of the ruling elite.

The positivist ideology

The context in Latin America

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Latin America, fresh from its wars of independence, was looking for models to structure its young republics. Against this backdrop of aspirations for modernity and political and social instability, positivism, a philosophy developed mainly by Auguste Comte in France, found fertile ground. With its unshakeable faith in science and rationality as a means of understanding and transforming society, this ideology was adopted by many Latin American intellectuals and leaders. In Brazil, for example, positivism has left an indelible mark. The national motto, "Ordem e Progresso", is a direct testimony to this influence. Brazilian positivists were convinced of the need for an enlightened elite to guide the country towards modernity. In Mexico, under the regime of Porfirio Díaz, known as the Porfiriato, a positivist approach was adopted to modernise the country. This involved massive investment in infrastructure, education and industry, but was also accompanied by political repression. The adoption of positivism in Latin America can also be seen as a response to the rise of American imperialism. With policies such as the Monroe Doctrine and Theodore Roosevelt's "Big Stick" policy, the United States was seen as an imminent threat. Positivism offered Latin American countries a path to internal development and modernisation, without having to submit to American influence or intervention.

Positivism, with its roots in Europe, found a particular resonance in Latin America at the end of the 19th century. This philosophy, which emphasised science, rationality and progress, became the mainstay of many Latin American leaders seeking to transform their nations. Positivism's appeal lay largely in its promise of modernity. At a time when Latin America was seeking to define itself after decades of colonial and post-colonial struggles, positivism offered a clear model for national development. Leaders believed that, by adopting a scientific and rational approach to governance, they could accelerate modernisation while establishing much-needed stability. The state became the principal actor in this transformation. Under the influence of positivism, many governments sought to centralise power, in the belief that a strong state was essential to achieve the ambitions of modernisation. This centralisation aimed to eliminate inefficiencies and create a more coherent structure for implementing public policy. Infrastructure became a major priority. Governments invested in building railways, ports, roads and telegraphs, facilitating trade, communication and national integration. These projects were not only symbols of progress, but were essential for integrating previously isolated regions and stimulating the economy. Education and public health also received renewed attention. Positivist leaders firmly believed that education was the key to progress. Schools were built, curricula reformed and efforts were made to increase literacy rates. Similarly, recognising the link between health, productivity and progress, initiatives were launched to improve public hygiene, combat disease and establish hospitals.

Despite its promises of progress and modernisation, positivism also had sombre consequences in Latin America. Under the guise of rationality and order, this philosophy was often misused to justify authoritarian and repressive policies. The central idea of positivism was that society should progress through defined stages, based on science and rationality. However, this linear vision of progress led some leaders to believe that everything considered "backward" or "primitive" had to be eliminated if society was to progress. In this context, political dissent, often associated with "backward" or "chaotic" ideas, was seen as an obstacle to progress. As a result, many positivist regimes repressed or even eliminated political opponents in the name of "Order and Progress". Moreover, the positivist vision of progress was often tainted by ethnocentric prejudices. Indigenous cultures, with their distinct traditions and ways of life, were often seen as vestiges of an "inferior" stage of development. This perspective led to policies of forced assimilation, where indigenous populations were encouraged, or often forced, to abandon their traditions in favour of the dominant culture. In some cases, this even led to forced displacement and genocidal policies. At the same time, to 'whiten' the population and make it more homogenous, many states encouraged European migration. The underlying idea was that the arrival of European migrants, seen as carriers of culture and progress, would dilute indigenous and Afro-Latin American influences and accelerate modernisation.

In the mid-19th century, Latin America underwent major transformations that stimulated its economy and strengthened its role on the world stage. The expansion of communication routes and population growth were key factors in this upward economic dynamic, particularly as regards the production and export of raw materials. The construction of railways was one of the most transformative innovations of this period. These railways crossed previously inaccessible terrain, linking remote regions with urban centres and ports. This not only facilitated the extraction of precious minerals such as silver, gold and copper, but also made it possible to transport these resources to ports for export. Railways also stimulated the development of commercial agriculture, allowing products such as coffee, sugar, cocoa and rubber to be transported more efficiently and at lower cost. Roads, although less revolutionary than railways, also played a crucial role, particularly in areas where railways were not present or economically viable. They facilitated the movement of goods and people, strengthening economic links between towns and the countryside. Ports, meanwhile, have been modernised to meet the growing demand for exports. These improved port infrastructures have made it possible to accommodate larger ships and increase export capacity, facilitating trade with Europe, the United States and other regions. Population growth also played a key role. With a growing population, there was a more abundant workforce to work in the mines, plantations and fledgling industries. In addition, immigration, particularly from Europe, brought skills, technology and capital that helped modernise the economy.

Population growth in Latin America in the 19th century had a profound impact on the region's economy. A growing population means increased demand for goods and services, and in the Latin American context, this translated into increased demand for raw materials and agricultural products. At a national level, population growth has led to increased demand for food, clothing and other essential goods. Demand for agricultural products such as maize, wheat, coffee, sugar and cocoa has grown, stimulating the expansion of farmland and the introduction of more intensive and specialised farming methods. This internal demand also encouraged the development of local industries to transform these raw materials into finished products, such as sugar mills and coffee roasters. Internationally, the industrial era in Europe and North America created an unprecedented demand for raw materials. Industrialised countries were looking for reliable sources of raw materials to feed their factories, and Latin America, with its vast natural resources, became a key supplier. Amazonian rubber, for example, was essential for tyre manufacture in European and North American factories, while minerals such as silver and copper were exported to meet the needs of the metallurgical industry. The expansion of these industries had a major economic impact. It created jobs for thousands of people, from farm workers and miners to tradesmen and entrepreneurs. This employment growth in turn stimulated other sectors of the economy. For example, with more people earning wages, there was an increased demand for goods and services, which encouraged the development of trade and services.

The boom in the production and export of raw materials in the 19th century transformed Latin America into a key player in the global economy. However, this transformation has had double-edged consequences for the region. Dependence on the export of raw materials has created what is often referred to as a "cash economy". In this model, a country relies heavily on one or a few resources for its export earnings. While this can be lucrative during periods of high demand and high prices, it also exposes the country to great volatility. If commodity prices fall on the world market, this can lead to economic crises. Many Latin American countries have experienced this on several occasions, where a fall in the price of a key resource has led to recessions, debt and economic instability. This dependence also reinforced unequal economic structures. Export industries were often controlled by a national elite or foreign interests. These groups accumulated enormous wealth from the export of resources, while the majority of the population saw little or no benefit. In many cases, workers in these industries were poorly paid, worked in difficult conditions and had no access to social benefits or labour protection. In addition, the concentration of investment and resources in export industries often neglected the development of other sectors of the economy. This has limited economic diversification and reinforced dependence on raw materials.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the gap between Latin America and the northern and western United States widened considerably, reflecting divergent development trajectories influenced by a combination of economic, political and social factors. In economic terms, while the United States and Western Europe were undergoing rapid industrialisation, most Latin American countries remained largely agrarian, heavily dependent on the export of raw materials. This dependence exposed them to the volatility of world prices. Foreign investment in Latin America, although substantial, was often concentrated in extractive sectors such as mining. Moreover, a large proportion of the profits generated by these investments went back to the investing countries, limiting the economic benefits for Latin American countries. In terms of infrastructure, although investments were made, they were mainly focused on supporting export industries, sometimes neglecting the development of a robust domestic market. Politically, the relative stability enjoyed by the US and Western Europe contrasted sharply with the frequent instability of many Latin American countries, marked by coups d'état, revolutions and frequent changes of government. In addition, US foreign policy, notably the Monroe Doctrine and the 'Big Stick' policy, strengthened its influence in the region, often to the detriment of local interests. Socially, Latin America has continued to struggle against deeply rooted structures of inequality inherited from the colonial period. These inequalities, where a narrow elite held much of the wealth and power, hindered inclusive economic development and were often the source of social and political tensions. Moreover, unlike the United States and Western Europe, which invested heavily in education, Latin America offered limited access to education, particularly for its rural and indigenous populations.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the economic, political and social differences between Latin America and the northern and western United States became increasingly marked, reflecting divergent development trajectories and influencing their relations on the international stage. Economically, the US North and West had succeeded in diversifying their economies, moving away from an exclusive dependence on raw materials to embrace industrialisation. This diversification offered a degree of protection against the vagaries of the global market. Latin America, on the other hand, with its increased dependence on the export of raw materials, was at the mercy of international price fluctuations. This economic vulnerability not only slowed the region's growth, but also contributed to widening the wealth gap with the more industrialised nations, exacerbating the disparities in living standards between the two regions. Politically, the stability and democratic nature of government in the United States has created a favourable environment for business, attracting foreign investment and immigrants in search of better opportunities and civil liberties. Latin America, on the other hand, with its often authoritarian regimes, has experienced periods of political instability, marked by coups d'état, revolutions and, in many cases, flagrant violations of human rights. These conditions not only discouraged foreign investment, but also led many Latin Americans to seek refuge elsewhere, particularly in the United States. On the social front, the United States had invested heavily in developing its education and health systems, leading to a general improvement in living standards for a large proportion of its population. Latin America, despite its cultural and natural riches, was struggling with major inequalities. A small elite held much of the wealth and power, while the majority of the population faced challenges such as limited access to quality education, adequate healthcare and economic opportunities.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the geopolitical and economic landscape of the Americas underwent significant changes. While Britain had historically been the main trading partner and investor in Latin America, the rise of the United States changed this dynamic. The United States, having consolidated its own industrial and economic development, began to look southwards to extend its influence and economic interests. This transition from British to American influence in Latin America was not simply a question of trade and investment. It was part of a wider context of projecting power and influence. The United States, with the Monroe Doctrine and later the "Big Stick" policy, made clear its intention to play a dominant role in the Western Hemisphere. Economically, the US invested heavily in key infrastructure in Latin America, including railways, ports and, emblematically, the Panama Canal. These investments have certainly helped to modernise parts of Latin America and facilitate trade. However, they have often been made on terms that are advantageous to US companies, sometimes to the detriment of local interests. Politically, the growing influence of the United States has had varied consequences. In some cases, it has supported or installed regimes favourable to its interests, even if this meant suppressing democratic or nationalist movements. This has sometimes led to periods of instability or authoritarian regimes that have neglected the rights and needs of their own people. Culturally, American influence began to be felt in many areas, from music and film to fashion and language. This paved the way for an enriching cultural exchange, but also raised concerns about the erosion of local cultures and cultural homogenisation.

The influence of Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism, a misguided interpretation of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theories, had a profound and often damaging influence on American thought in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By extrapolating the ideas of 'survival of the fittest' to human society, some argued that certain races or ethnic groups were naturally superior to others. In the United States, this ideology was used to support the idea that the economic and political dominance of the Anglo-Saxons was the result of their biological superiority. This belief has had profoundly discriminatory consequences for many groups in the United States. Immigrants, particularly those from Eastern and Southern Europe, were seen as biologically inferior and less suitable for American citizenship. African-Americans, already oppressed by the system of slavery, were confronted with a new pseudo-scientific justification for segregation and racial discrimination. Native Americans, for their part, were portrayed as an "endangered race", justifying their forced removal and forced assimilation. Social Darwinism has also influenced American policy. Immigration laws, for example, were shaped by beliefs in racial superiority, restricting immigration from regions considered "biologically inferior". Racial segregation, particularly in the South, was justified not only by open prejudice, but also by pseudo-scientific beliefs about racial superiority.

The influence of Social Darwinism was not limited to North America. In Latin America, the ideology also found fertile ground, profoundly influencing social policies and attitudes during a critical period of modernisation and national change. The ethnic and cultural complexity of Latin America, with its mix of indigenous, African and European heritages, was interpreted through the prism of Social Darwinism. Elites, often of European descent, have adopted this ideology to justify and perpetuate their economic and political domination. By asserting that groups of African and Amerindian descent were biologically inferior, they were able to rationalise gross inequalities and underdevelopment as the inevitable result of the region's ethnic make-up. This ideology had devastating consequences for indigenous and Afro-Latin American populations. Indigenous cultures, with their languages, traditions and beliefs, have been actively suppressed. In many countries, policies of forced assimilation were implemented, seeking to "civilise" these populations by integrating them into the dominant culture. Indigenous land was often seized, forcing them to work in conditions akin to servitude for the landed elites. Afro-Latin Americans were also victims of this ideology. Despite their significant contribution to the region's culture, economy and society, they were relegated to subordinate positions, often facing discrimination, marginalisation and poverty. The concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small elite was justified by this belief in biological superiority. The elites used Social Darwinism as a shield against criticism, arguing that inequalities were natural and inevitable.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an intellectual transformation took place in Latin America. The elites, faced with the reality of their nations' relative underdevelopment compared with certain European powers and North America, sought to understand and rectify this situation. Contrary to certain fatalistic interpretations that might have attributed backwardness to divine will or immutable factors, many Latin American thinkers and leaders adopted a more proactive perspective. They saw backwardness not as an inevitability, but as the result of historical actions, decisions and circumstances. This perspective was partly influenced by the European currents of thought of the time, such as positivism, which valued reason, science and progress. If backwardness was the result of human choices, then it could also be overcome by deliberate human actions. This belief led to a series of modernisation efforts across the continent. Governments invested in infrastructure, such as railways and ports, to facilitate trade and economic integration. They have sought to reform education systems, promote industrialisation and attract foreign investment. Many also adopted immigration policies to 'whiten' their populations, in the hope that the arrival of European settlers would stimulate economic and social development. However, these modernisation efforts were not without their contradictions. Despite seeking to transform their societies, many elites maintained unequal social and economic structures. Indigenous and Afro-Latin American populations were often marginalised or directly oppressed in this process of modernisation. Moreover, attempts to imitate European or North American models have sometimes led to unexpected or undesirable results.

The history of the United States is marked by a tension between the declared ideal of equality and the realities of discrimination and oppression. Part of this tension can be attributed to the way in which religious beliefs have been interpreted and used to justify existing power structures. In the United States, Protestantism, particularly in its Evangelical and Puritan forms, has played a central role in the formation of national identity. The early Puritan settlers believed that they had made a covenant with God to establish a "city on a hill", an exemplary society based on Christian principles. Over time, this idea of a special divine mission evolved into a form of manifest destiny, the belief that the United States was destined by God to expand and dominate the North American continent. This belief in a divine mission was often intertwined with notions of racial and cultural superiority. Anglo-Saxon Protestant elites, particularly in the nineteenth century, often saw their economic and political success as proof of divine favour. In this context, domination over other groups, whether Native Americans, African-Americans or non-Anglo-Saxon immigrants, was often seen not only as natural, but also as ordained by God. This interpretation of faith was used to justify a range of policies and actions, from westward expansion and the dispossession of Native American lands, to racial segregation and discriminatory laws against immigrants. It also acted as a counterweight to reform movements. For example, during the post-Civil War Reconstruction period, many white Southerners used religious arguments to oppose civil rights for African-Americans.

The history of Latin America is deeply marked by racial and social hierarchies inherited from the colonial period. After the independence of Latin American nations in the early nineteenth century, these hierarchies persisted and were often reinforced by modern ideologies, including Social Darwinism and other forms of racial thinking. Latin American elites, often of European descent or "criolla" (descendants of Spanish colonists born in America), played a central role in the formation of the new republics. These elites often saw their position of power and privilege as the result of their cultural and racial superiority. In this context, indigenous, mestizo and Afro-Latin American populations were often perceived as inferior, not only in terms of race, but also in terms of culture, education and ability to contribute to national progress. This perception had profound consequences for the region's politics and development. Elites have often sought to 'improve' the racial composition of their countries by encouraging European immigration, in the hope that this would stimulate economic development and 'whiten' the population. In some countries, such as Argentina and Uruguay, these policies have had a significant impact on demographic composition. Indigenous populations, in particular, have been the victims of forced assimilation policies. Their lands have been seized, their cultures and languages actively repressed, and they have been encouraged or forced to adopt 'Western' lifestyles. In many countries, indigenous people were seen as obstacles to modernisation, and their lands and resources were coveted for economic development. Mestizos and Afro-Latin Americans were also marginalised, although they often played a central role in the economy and society. They were often relegated to subordinate positions, facing discrimination and exclusion from the political and economic spheres of power.

Positivism, introduced to Latin America mainly in the 19th century, was enthusiastically embraced by many of the region's elites. Inspired by the work of European thinkers such as Auguste Comte, these elites saw positivism as a solution to the challenges facing their fledgling republics. For them, positivism offered a systematic and rational approach to guiding national development. The central idea was that, through the application of the scientific method to governance and society, the "irrationalities" and "archaisms" that impeded progress could be overcome. These 'irrationalities' were often associated with the cultures and traditions of indigenous, mestizo and Afro-Latin American populations. Positivism was thus both an ideology of modernisation and a tool for strengthening elite control over society.

The 'order and progress' regimes that emerged in this context had several features in common:

- Centralisation of power: These regimes often sought to centralise power in the hands of a strong government, reducing regional and local autonomy.

- Modernisation of infrastructure: They invested heavily in infrastructure projects such as railways, ports and education systems, with the aim of integrating their national economies and promoting development.

- Promoting education: Convinced that education was the key to progress, these elites sought to establish modern education systems, often inspired by European models.

- Public health reform: Modernising health systems was also seen as essential to improving quality of life and promoting economic development.

However, these efforts at modernisation were often accompanied by policies of forced assimilation towards indigenous populations and other marginalised groups. Moreover, although positivism advocated rationality and science, it was often used to justify authoritarian policies and to repress dissent.

The adoption by Latin American elites of the mantra of "order and progress", although inspired by intentions of modernisation and development, has often had harmful consequences for large sections of the population. Positivist principles, while advocating rationality and science, were misused to justify policies that reinforced existing inequalities. Under the pretext of maintaining order and promoting progress, many regimes repressed all forms of dissent. Political opponents, trade unionists, human rights activists and other groups were persecuted, imprisoned, tortured or even executed. These actions were often justified by the need to preserve stability and eliminate "disruptive elements" from society. At the same time, the indigenous populations, already marginalised since the colonial period, were further oppressed. Their land has been confiscated for development projects or large-scale farming. Their cultures and traditions have been devalued or actively repressed as part of efforts to assimilate them. Workers, particularly in the extractive and agricultural industries, have been subjected to precarious and often dangerous working conditions. Attempts to organise or demand rights were violently repressed. At the same time, economic policies often favoured the interests of the elite, leading to further concentration of wealth. Large landowners, industrialists and financiers benefited from subsidies, concessions and other advantages, leaving the majority of the population to continue living in poverty. Despite the economic growth that some countries experienced during this period, the benefits were not equitably distributed. Large segments of the population remained excluded from the benefits of development. The lessons learned from this period remain relevant today, reminding us of the potential dangers of the uncritical adoption of foreign ideologies without taking into account the local context and the needs of the population as a whole.

The positivist philosophy

Positivism, developed by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in the mid-19th century, was born against a backdrop of profound social and intellectual upheaval in Europe. The Industrial Revolution was radically transforming societies, and political revolutions were challenging established orders. Faced with these changes, Comte sought to establish a solid foundation for knowledge and social progress. In the first phase, the theological stage, individuals attempt to explain the world around them through the prism of religion. Natural and social phenomena are understood to be the result of the will of the gods or of a superior god. It was a period dominated by faith and supernatural beliefs. As society evolved, it entered the metaphysical stage. Supernatural explanations gave way to more abstract ideas. Although people begin to look for more abstract explanations for phenomena, these ideas remain speculative and are not necessarily based on empirical reality. Eventually, society reaches the scientific or positive stage, which Comte sees as the ultimate stage of human development. People recognise that the true understanding of the world comes from scientific observation and the experimental method. Beliefs and actions are then based on facts and tangible evidence, and society is guided by scientific laws. Comte hoped that by adopting a positivist approach, society could overcome the disorder caused by the social upheavals of his time. He envisaged the creation of a 'science of society', sociology, which would apply the same rigour to the study of society as was used in the natural sciences to study the physical world. Although positivism has had a considerable influence, it has also been criticised for its deterministic view of social progression and its sometimes blind faith in science as the cure for all social ills.

Auguste Comte, in his positivist vision, conceptualised the development of human society as an orderly progression through distinct stages. This idea of progression was deeply rooted in his belief in a natural order and in the linear evolution of society. He saw society as a living organism, subject to natural laws similar to those that govern the physical world. Just as biological species evolve through natural selection, Comte believed that societies would advance through a similar process. Societies that were able to adapt, integrate and develop advanced social and intellectual structures would prosper, while those that could not adapt would be left behind. Social integration, for Comte, was a key indicator of progress. An integrated society was one in which individuals and institutions worked in harmony for the common good. Conflict and disorder were seen as symptoms of a less evolved society or one in transition. The degree of scientific knowledge was another essential criterion for measuring progress. Comte firmly believed that science and rationality were the ultimate tools for understanding and improving the world. Thus, a society that embraced scientific thought and rejected superstition and religious dogma was, in his eyes, more advanced.