From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The United States began to rise as an imperial power in the late 19th century, following the conclusion of the Spanish-American War in 1898. The war resulted in the US acquiring control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines and marked the beginning of the US's emergence as a global power.

In the following years, the US intervened in various countries in the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico, Honduras, and Nicaragua, in order to protect American economic interests and maintain stability in the region. These interventions laid the foundation for the Big Stick Policy, which President Theodore Roosevelt articulated in the early 1900s. The policy stated that the US would intervene in the affairs of Latin American countries to protect American economic interests and maintain stability in the region.

However, by the 1920s, the US faced domestic economic challenges, and many Americans were becoming increasingly isolationist and opposed to the idea of intervening in foreign affairs. Additionally, the Big Stick Policy had led to a number of interventions and occupations in Latin American countries, which had resulted in widespread resentment and hostility towards the US.

In response, President Herbert Hoover announced the Good Neighbor Policy, which stated that the US would no longer intervene in Latin American countries' affairs and instead seek to build friendly relations with them through cooperation and mutual respect. The Good Neighbor Policy marked a shift away from the interventionist policies of the past and towards a more peaceful and cooperative foreign policy.

Reminder

During the first half of the 19th century, the United States experienced significant territorial expansion, both to the west and to the south. This expansion was driven by a combination of factors, including the desire for new land, resources, and markets, as well as a belief in American exceptionalism and the "manifest destiny" of the US to expand its territory and influence.

One of the key ways in which the US expanded its territory during this time was through war. The most notable example is the Mexican-American War, which occurred between 1846 and 1848. The war was sparked by disputes over the boundary between Texas, which had recently been annexed by the US, and Mexico, and ultimately resulted in the US gaining control of large parts of what is now the American Southwest, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

The US also expanded its territory through the purchase of land. One of the most significant examples of this was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, in which the US purchased a vast tract of land from France, which included present-day Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, parts of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana.

Additionally, the US also expanded through colonization, for example the Oregon trail, where thousands of American settlers migrated to the Pacific Northwest during the 1840s and 1850s, which led to the eventual American annexation of the territory.

Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny were two major doctrines that significantly shaped American foreign policy and territorial expansion during the 19th century.

President James Monroe issued the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, which stated that any attempts by European powers to colonize or interfere with the affairs of the newly independent nations of the Western Hemisphere would be viewed as a threat to the security and stability of the United States. It established the US as the dominant power in the Americas and helped to shape American foreign policy for the next century.

Manifest Destiny, on the other hand, was a belief that it was the God-given mission of the United States to expand its territory and influence across North America and to spread its system of government, economy and culture. This idea was used to justify the territory territorial expansion the annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the settlement of the American West.

Together, these two doctrines helped to shape American foreign policy and territorial expansion during the 19th century and beyond. The Monroe Doctrine helped to establish the US as the dominant power in the Americas, while Manifest Destiny provided a justification to the expansion and the spread of American influence.

By around 1850, the territorial expansion of the United States had reached its present-day boundaries, with the exception of Alaska, which was purchased from Russia in 1867. The western border of the US had been expanded through a combination of war, the purchase of territories, and colonization, including the Mexican-American War, the Louisiana Purchase, and the settlement of the American West.

In terms of expansion northwards, the boundary between the US and Canada was established through a series of treaties and agreements, including the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War, and the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, which ended the War of 1812. In addition, the agreement with England in 1818 established the 49th parallel as the border between the US and Canada from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains.

So, expansion northwards to Canada was no longer possible after the agreement with England in 1812. The map of today's UniAs a result, the States was almost complete by 1850, except Alaska, which was the last territory to be acquired.

After the capture of northern Mexico as a redue toxican-American War, the US acquired many territories, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. These territories were relatively spared, and the US government saw them as opportunities for expansion and settlement.

However, the issue of slavery and the balance between slave and abolitionist states became a major political problem in the years following the war, and it complicated any further expansion southwards. The question of whether the new territories acquired from Mexico should allow slavery or not was a contentious issue, and it ultimately led to. The compromise of 1850 sought to resolve the issue by allowing California to enter the Union as a free state while the other territories were left to decide the question of slavery through popular sovereignty.

The Compromise of 1850 helped temporarily resolve the balance between slave and abolitionist states. Still, it prevented the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, which was largely caused by the expansion of slavery into the new territories. So, the question of the balance between slave and abolitionist states became a major significance for any expansion southwards, ultimately leading to the civil war.

Private annexation attempts

In addition to government-led expansion and territorial acquisitions, there were also private annexation attempts in territories considered to be natural areas of the United States, including the Caribbean and Central America. These private annexation attempts were often led by American business interests, such as railroad companies, mining companies, and agricultural interests, who sought to expand their operations and gain access to new markets and resources.

One example of private annexation was the attempt by American businessman William Walker to conquer and annex parts of Central America, including Nicaragua, in the 1850s. Walker, a former medical doctor, lawyer and journalist, led a group of American mercenaries to establish himself as the ruler of Nicaragua and annex it to the United States. Walker's efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and the government of Honduras executed him in 1860.

The private annexation attempts by groups of adventurers in Cuba and William Walker in Nicaragua were driven by a desire to expand the United States and increase American economic and political influence in the region. These attempts were motivated by a variety of factors, including the desire for economic gain and the belief in the idea of American exceptionalism.

However, these attempts also risked tipping the balance in favour of slavery, which was a deeply divisive issue in the United States at the time. The annexation of Cuba or Nicaragua would have added new slave states to the Union, further exacerbating the tensions between the slave and abolitionist states. As a result, these private annexation attempts met with opposition from the United States government and ultimately failed.

In addition, it's important to note that these private annexation attempts also met with opposition from local people and other countries in the region, as they would have resulted in the loss of sovereignty and control over their territories.

William Walker's actions were widely condemned in the United States, and he became a controversial figure. He was widely seen as a rogue adventurer who had acted without the support or authorization of the US government. His actions were seen as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, which was a US policy intended to prevent foreign colonization or any other kind of political control of the region by European powers.

The notion of American exceptionalism was a justification used to justify American expansionism. Still, it also led to the belief that American ways were superior to those of other nations, which led to a disregard for the people and cultures of other countries, which in turn led to resistance and opposition to American expansionism.

Despite his lack of success and his controversial legacy, William Walker's actions significantly impacted the political and social history of Central America, and he remains a controversial figure in the region. His private annexation attempts were one of the many examples of American expansionism in the 19th century, driven by economic interests and a belief in American exceptionalism.

After his execution, many of his followers were captured, executed, or forced to leave the country. His actions were widely criticized in the United States, and he became a controversial figure. He was seen as a rogue adventurer who had acted without the support or authorization of the US government. His actions were seen as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, which was a US policy intended to prevent foreign colonization or any other kind of political control of the region by European powers.

His actions in Central America were also met with resistance and opposition from local people, and historians still debate his legacy in the region. Some view him as a heroic figure who sought to bring modernization and progress to the region, while others see him as a ruthless dictator who sought to impose his will on the people of Central America.

Another example of private annexation attempts was in Hawaii, where American planters and businessmen sought to annex the islands to the United States to gain access to the Hawaiian sugar market. The annexation of Hawaii was a complicated process involving the political and economic interests of many different actors, including American planters, merchants, politicians, the Hawaiian monarchy, and local inhabitants.

In the late 19th century, American planters and businessmen had invested heavily in Hawaiian sugar plantations and had come to dominate the Hawaiian economy. They saw annexation as a way to gain access to the American market and to protect their investments from foreign competition. American politicians, such as President Cleveland, also saw Hawaii as a valuable strategic location, as it would be a valuable naval base for the United States.

The annexation of Hawaii was eventually achieved in 1898, following a coup d'etat that was supported by American interests. The annexation of Hawaii was accomplished by a joint resolution of Congress, which was signed into law by President McKinley. It was a controversial move, which was opposed by many Hawaiian nationalists and by some Americans who believed that annexation would undermine American democratic values and lead to the subjugation of a sovereign nation.

U.S. expansion was suspended during the Civil War between 1861 and 1865, as the country focused on the conflict between the Union (north) and Confederacy (south) over slavery and states' rights. After the Civil War ended in 1865, the country was reunited and slavery was abolished with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

After the Civil War, the United States resumed its expansionist policies, with a renewed emphasis on economic growth and territorial expansion. The country continued to push westward as the government sought to settle and develop the remaining western territories. This was done through a variety of means, including treaties with native tribes, the purchase of land from Mexico and other countries, and the annexation of new territories, such as Alaska in 1867.

Additionally, the United States also sought to expand its influence and control in other parts of the world, including the Caribbean and Central America, through various means such as the Big Stick Policy and the Good Neighbor Policy. The Big Stick Policy relied on economic and military pressure to assert American dominance, while the Good Neighbor Policy relied on diplomacy and cooperation to achieve the same goals. The United States also continued to pursue its expansionist policies in Asia and the Pacific.

Expansion through the acquisition of counter territories

The United States acquired Alaska from Russia in 1867 through a treaty of cession in which Russia sold the territory to the United States for $7.2 million. The acquisition of Alaska was met with mixed reactions in the United States, with some viewing it as a valuable acquisition of valuable natural resources. In contrast, others viewed it as a "waste of money" on an inhospitable and remote territory.

In 1867, the United States also acquired the Midway Islands in the Pacific Ocean. This was done through a guano-mining claim under the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which authorized American citizens to take possession of any unclaimed islands for the purpose of mining guano.

In 1878, the United States also acquired a coal station in the Samoan Islands in the Pacific. This was done to establish a coaling station for American naval ships in the Pacific and to protect American commercial interests in the region. The coal station was acquired through a treaty with the local Samoan leaders.

These acquisitions of Alaska, Midway Islands, and the Samoan Islands were part of a broader expansionist policy of the United States in the 19th century aimed at securing strategic locations, natural resources, and access to new markets. This expansion also aimed to project American power and influence in different regions and protect American commercial interests.

With the purchase of Alaska and the acquisition of the Midway Islands and the Samoan Islands, the United States began to focus on a different type of territorial expansion in the South Pacific. Instead of acquiring new territories for settlement or colonization, the United States began to acquire territories to facilitate trade and access to new markets.

Several factors drove this change in focus. One of the main reasons was the strong revival of European, Russian and Japanese imperialism in the late 19th century. As other imperial powers were expanding their territories and influence in different regions of the world, the United States sought to establish a presence in these regions to protect American commercial interests and to project American power and influence.

Another reason was the rapid industrialization and economic growth of the United States in the late 19th century. American entrepreneurs and businesses were looking for new markets and opportunities to expand their operations outside the country's borders. Acquiring trading territories in the South Pacific gave American businesses access to new markets, resources and opportunities.

In this new context, American foreign policy began to be framed by the concept of the Open Door Policy, which aimed to maintain the territorial integrity and political independence of China while also protecting American economic interests in the region, and the Big Stick Policy, which sought to extend American influence in the Caribbean and Central America through a show of military force and intervention.

In the late 19th century, the United States had become a major industrial and agricultural power with a rapidly growing population. With this expansion of industry and agriculture, American businesses and entrepreneurs were looking for new markets to sell their goods and services.

At the same time, the United States was also looking to extend its influence and protect its interests in the regions around its southern border, particularly Mexico. With the rapid industrialization and economic growth of the United States, it was also looking to expand its commercial markets in the Caribbean and Central America, where other imperial powers, such as European countries, Russia and Japan, were also seeking to establish a presence.

This drive to expand commercial markets and extend influence in the region was reflected in American foreign policy, which was characterized by the Open Door Policy and the Big Stick Policy. Both policies aimed at protecting American economic interests and projecting American power and influence in the region while also maintaining other countries' territorial integrity and political independence.

Under the rule of Porfirio Diaz in the late 19th century, Mexico had a significant population of American settlers, particularly in the country's northern regions. These American settlers were primarily involved in the mining, industrial and agricultural sectors and played a significant role in developing these industries in Mexico.

During this time, the United States had significant economic interests in Mexico and the American settlers were able to exert significant influence over the Mexican economy. Diaz's government was open to foreign investment and the American settlers were able to establish themselves as a powerful economic force in the region, especially in the mining, oil and railroad sectors.

However, it's worth noting that the American settlers were not interested in colonizing Mexico. Instead, they were more focused on controlling the resources, such as mines, oil and other recent industry, and to some extent, the haciendas (farms), for the benefit of their own country. The United States was looking to gain access to Mexican resources and markets to fuel its own economic growth, rather than outright colonization.

During this time, the United States began to adopt a more assertive foreign policy, known as the Big Stick Policy, which emphasized the use of military force and economic pressure to assert its influence in the Americas and beyond. This policy was championed by President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed that the United States should play a more active role in world affairs and exert its power to promote stability and protect American interests. However, as the country entered the 20th century, the Big Stick Policy began to be criticized for its aggressive and interventionist approach, leading to the emergence of the Good Neighbor Policy under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This policy sought to improve relations with Latin American countries through diplomacy and mutual cooperation, rather than coercion and intervention. This change in foreign policy was driven by a growing recognition of the limitations of the Big Stick Policy and the desire to build stronger and more cooperative relationships with countries in the region.

This shift in American expansionism and imperialism during the late 19th century can be attributed to several factors, including a desire for new commercial markets, a belief in the superiority of the American way of life, and the influence of racist ideologies such as the "one drop of blood rule". The United States sought to expand its influence by acquiring territories that would serve as trading partners and provide access to new markets, rather than through colonization and the displacement of indigenous populations as was done during the conquest of the West. This shift in strategy also reflected a growing belief in the inferiority of non-white populations, which influenced American attitudes towards expansion in Latin America and the Caribbean.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

New conception of the Destiny Manifest

This new conception of Manifest Destiny, which emerged in the late 19th century, focused on economic expansion rather than territorial expansion. American businesses and corporations sought to gain access to resources and markets in other countries, while also seeking to exert political and economic influence over these nations. This shift in American foreign policy was reflected in the new doctrine of the "Big Stick" and the "Good Neighbor" policy, which emphasized the use of economic and political power to exert influence over other countries, rather than outright annexation or military conquest.

This belief in American superiority led to the justification of various actions taken by the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the annexation of Hawaii and the Spanish-American War, which led to the acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. It also played a role in the intervention in Latin American countries, such as the support for the overthrow of democratically-elected governments in favor of authoritarian leaders who were more amenable to American interests. This belief in American exceptionalism and the idea of spreading American values and institutions to other nations is still present in American foreign policy to this day.

In the late 19th century, the concept of Social Darwinism emerged and played a significant role in shaping the United States' policy of territorial expansion and economic domination in Latin America and the Pacific. Social Darwinism, a belief that the strong should prevail and that certain races were superior to others, was used to justify the subjugation of so-called "inferior" peoples and the acquisition of their territories. Businessmen and entrepreneurs from the United States, who were seen as the "fittest" and chosen by Social Darwinism, were generously supported by the U.S. federal government and public finances in their efforts to expand American influence and control over resources in Latin America, Hawaii and other parts of the world.

This support from the government and public finances took various forms, such as subsidies for shipping and communication infrastructure, military protection for American interests, and the use of diplomacy to open up markets and protect American investments. In addition, the U.S. government also supported these entrepreneurs by creating a favorable legal and political environment for them to operate in, through the use of treaties, trade agreements, and other forms of international law. Overall, this support from the U.S. government allowed American entrepreneurs to expand their economic and political influence in these territories, and played a significant role in the continued expansion of the United States throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.es.

Alfred Thayer Mahan, a United States Navy flag officer and geostrategist, wrote seminal works on naval power's importance in determining nations' rise and fall. His most notable publication, "The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783" (1890), posited that control of the seas through a formidable navy is a crucial factor in the international relations and global power dynamics. The aim was to protect the new American trading empire and to support Washington's overseas policy by allowing the US to maintain a robust naval presence in the international waters, which would protect American commerce and interests. Mahan's ideas had a significant impact on the naval policies and strategic thinking of the United States, in which he advocated for a strong navy that would be capable of competing with the British Royal Navy, which had hitherto dominated the seas. Mahan's ideas were particularly influential during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the United States sought to assert itself as a major naval power.

Mahan's ideas on naval power and the need for a strong navy to protect American interests and commerce greatly influenced the development of the United States Navy. The Navy focused on maintaining a strong presence in international waters, particularly in the Atlantic and Caribbean, and competing with European powers such as Britain. The United States Navy, under the influence of Mahan's ideas, also focused on building a strong battleship fleet and developing coaling stations and naval bases around the world to support its operations. The Navy also placed emphasis on naval education and training for its officers and sailors. Additionally, the Navy played a significant role in the Spanish-American War of 1898, which marked the emergence of the United States as a world power and further solidified the importance of a strong navy. The Navy continues to play a vital role in protecting American interests and providing security in international waters.

In the late 19th century, the United States Navy played a significant role in the history of Hawaii. In the 1880s, the U.S. government became increasingly interested in the islands as a potential naval base and coaling station. The U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, based in California, had been using the islands for refueling and repairs for many years. The U.S. government also became concerned about the potential threat of other foreign powers, such as Germany and Japan, to American interests in Hawaii.

In 1887, the U.S. government negotiated a treaty with Hawaii's monarch, King Kalakaua, which granted the U.S. the exclusive right to establish a naval base at Pearl Harbor. The U.S. Navy established a coaling station and repair facility at Pearl Harbor, which would become one of the most important naval bases in the Pacific.

In addition to its activities in Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy also played a role in overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. A group of American and European businessmen, known as the Hawaiian League, overthrew Queen Liliuokalani and established a provisional government. The U.S. Navy provided military support to the provisional government, and the U.S. government later annexed Hawaii as a territory in 1898.

The role of the US Navy in Hawaii in the 1880s was very important in the establishment of naval base and coaling station and also in the annexation of Hawaii as a territory of the US.

Imperialism declared under President William McKinley: 1898, War against Spain

The Spanish-American War began in 1898 and was a conflict between the United States and Spain. The U.S. declared war on Spain following the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, which was blamed on Spain. The war was fought primarily in Cuba and the Philippines, with the U.S. ultimately victorious. As a result, Spain ceded control of Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States, and the Philippines were sold to the U.S. for $20 million. The war marked a turning point in U.S. history as it marked the country's emergence as a world power.

The Spanish-American War occurred during the presidency of William McKinley, who served as President of the United States from 1897 to 1901. The war was one of the major events of his presidency, and it marked a significant turning point in U.S. foreign policy and international relations. The victory in the war and the acquisition of new territories, such as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, solidified the United States' status as a world power.

Cuba had been an important source of sugar for the United States for many years before the Spanish-American War. American planters and investors had established large sugar cane plantations in Cuba, which relied heavily on the labor of enslaved and later indentured Afro-Cuban workers. The U.S. had a strong economic interest in maintaining control of the island, in part because of the sugar trade, and this was one of the factors that led to the conflict with Spain. The war ended Spanish control of the island and the eventual establishment of an independent Cuba. However, the US maintained significant influence over the island throughout the 20th century.

The Spanish-American War was fought primarily in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The U.S. had declared war on Spain following the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, which was blamed on Spain, and the main objective of the war was to gain control of Cuba. The U.S. forces quickly gained control of the island, and Spain soon agreed to a ceasefire. As part of the peace agreement, Spain ceded control of Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States, and the Philippines were sold to the U.S. for $20 million. The war marked a significant turning point in U.S. foreign policy and international relations, as it marked the country's emergence as a world power.

Spain lost most of its American colonies in the early 19th century, with the exception of Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791, led to the independent Republic of Haiti in 1804, and the loss of the colony of Saint-Domingue, which was a major source of wealth for Spain. The Creole elite in Cuba and Puerto Rico, primarily white landowners and slaveholders, worried that a war of independence in their islands would lead to a similar revolt by enslaved people, as happened in Haiti.

In the 19th century, Cuba's economy was largely based on sugar production, and the island had become a major sugar producer in the Americas. The Creole elite had become wealthy through the profitable sugar trade and the importation of enslaved Africans to work on the plantations. They were unwilling to risk their wealth and status in a war of independence. The island of Cuba remained a Spanish colony until the Spanish-American War of 1898, when it was ceded to the United States as part of the peace treaty following the war.

After the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865, many Cubans, including Afro-Cubans, began to call for independence from Spain. In 1868, a group of planters and intellectuals led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes launched a war for independence known as the Ten Years' War. The war was fought primarily by Creole landowners and their enslaved and later indentured Afro-Cuban workers. It was supported by many Afro-Cubans, including General Antonio Maceo, who became a key leader in the war. However, the war was ultimately unsuccessful and was ended in 1878 with the Pact of Zanjón, which granted some autonomy to Cuba but did not bring about independence.

In 1886, Spain abolished slavery in Cuba, and in 1895, Cubans launched a new war for independence, known as the War of Independence. This war was led by José Martí and Antonio Maceo, both of whom had fought in the Ten Years' War. The war continued until 1898 when Spain ceded control of the island to the United States as part of the peace treaty following the Spanish-American War. The war of 1895-1898 is also known as the Cuban War of Independence.

Despite some initial successes, the War of Independence led by José Martí and Antonio Maceo, ended without achieving independence for Cuba. Martí died in 1895, and Maceo died in 1896, leaving the independence movement without their key leaders. The war had reached a stalemate by that time, and the situation in Cuba had become a source of concern for the United States.

At the time, the United States was going through an economic crisis, and many American businesses and politicians were looking for new markets abroad. With its strategic location and growing economy, Cuba was seen as a potential market for American goods and an opportunity for American businesses to invest. However, to justify a takeover of the island, it was necessary to gain the support of the American public. This was achieved by spreading false information about the state of the war and the situation in Cuba, portraying the Spanish as brutal oppressors and the Cuban independence fighters as heroic freedom fighters. This led to a wave of public sympathy for the Cuban cause and support for the U.S. intervention.

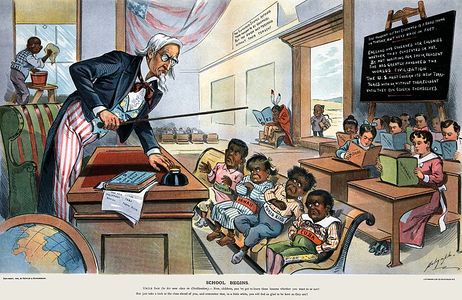

Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. The caption reads: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!".

In 1898, the United States declared war on Spain and quickly defeated the Spanish forces in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. As a result, Spain ceded control of these territories to the United States in the Treaty of Paris, which was signed on December 10, 1898. The United States paid Spain $20 million for the territories.

The cession of these territories marked the beginning of American imperialism, as the United States now controlled a significant amount of land and people outside of its own borders. The U.S. government justified the takeover of these territories as a "civilizing mission" to bring the benefits of American democracy and civilization to the peoples of these lands. However, this justification was often used to justify exploitative and oppressive policies towards the peoples of these territories, particularly in the Philippines where the US fought a brutal war to suppress the independence movement.

The United States transformed Puerto Rico into a protectorate and imposed a military government on Cuba until 1902, when it was officially declared independent. However, the United States maintained significant control over Cuban affairs through the Platt Amendment, which was added to the Cuban Constitution in 1901. This amendment limited Cuban sovereignty and granted the United States the right to intervene militarily in Cuba to defend American interests, including protecting life, property, and freedom.

The racism behind corporate America was indeed out in the open, as the U.S. government and American businesses had a vested interest in maintaining control over these territories, and their resources, labour, and markets. The U.S. government and American businesses often justified their actions by claiming they were helping to "civilize" the inhabitants of these territories. However, it was primarily driven by economic and strategic interests, with little regard for the rights and well-being of the people living in these territories.

The Platt Amendment gave the United States the right to intervene militarily in Cuba to defend American interests and included a provision for establishing a naval base in Cuba. This led to the United States leasing land from Cuba to establish the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, which is located in the Guantanamo Bay area of southeastern Cuba. The United States has maintained control of this base since 1903, paying an annual rent of $2,000 to the Cuban government until 1934 when the Cuban government, under pressure from the US, agreed to terminate the rent payments. Since then the US has refused to pay rent or negotiate a new agreement with the Cuban government. The base remains a contentious issue between the two countries, with the Cuban government demanding the return of the base to Cuban control and the United States maintaining that the base is necessary for national security.

The Open Door Policy, also known as the "Open Door Notes" was a set of principles put forward by the United States in the late 19th century to ensure that all nations would have equal trading opportunities in China. The policy was first proposed by U.S. Secretary of State John Hay in 1899 and 1900 in a series of diplomatic notes sent to major world powers. The policy was intended to counter the actions of imperial powers, such as Russia, Germany, France and Japan, who were seeking to carve out exclusive spheres of influence in China. The Open Door Policy stated that all countries should have equal access to trade and investment opportunities in China and that the territorial integrity of China should be preserved. While the policy was primarily directed at China, it had a broader significance. It reflected the U.S. desire to maintain an open, multi-polar world order and promote American economic interests in Asia and worldwide.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

The Open Door Policy became a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy, with the goal of ensuring that American companies had equal access to markets around the world. The United States used its economic and military power to influence the policies of other countries in order to open their markets to American goods and investments. As the US economy grew and American companies expanded overseas, the US government sought to establish a favourable economic environment for these companies, often at the expense of the interests of other countries. This often led to the US government using its influence to promote policies that would benefit American companies while undermining the economies of other countries. The Open Door Policy laid the foundation for the US economic expansion overseas and the US efforts to dominate global markets that continue to this day.

The Panama Canal

The idea of building a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Central America had been discussed since the 1870s as a way to improve trade and transportation between the two coasts of the Americas. The United States, in particular, had a significant interest in building the canal. It would greatly benefit the country's economy by reducing the time and cost of shipping goods between the East and West coasts. Additionally, the canal's construction would also provide a strategic advantage in the event of a potential military conflict, allowing the United States to move troops and resources more easily between its two coasts.

The United States began construction of the Panama Canal in 1904, and it was officially opened in 1914. The construction of the canal was a massive engineering undertaking, involving the excavation of thousands of cubic meters of earth, the construction of locks and dams, and the creation of a network of canals and lakes. The canal construction required a significant amount of resources, human labour and the relocation of thousands of people. It was considered one of the greatest engineering feats of the 20th century.

President Theodore Roosevelt played a key role in constructing and opening the Panama Canal. While he was not President at the time construction began in 1904, he took office in 1901 and was President until 1909. During his tenure, he strongly advocated for the canal's construction and provided significant political and financial support to the project.

In addition, he helped to resolve a diplomatic crisis with Colombia (the country that controlled the region where the canal was built). He helped establish the Panama Canal Zone, a strip of land controlled by the United States and used for the canal construction. Under his leadership, the United States acquired land rights and began constructing the canal. He visited the construction site and was present at the canal's opening in 1914.

When the United States began construction on the Panama Canal, Panama was a department of Colombia. However, during the late 19th century, Colombia was experiencing a civil war, and the situation in Panama was unstable. The United States, under the leadership of President Theodore Roosevelt, supported the idea of Panamanian independence from Colombia in order to facilitate the construction of the canal.

In 1903, the U.S. government helped to engineer a revolution in Panama, which resulted in the declaration of independence from Colombia. This was done by supporting and encouraging Panamanian rebels, and by sending U.S. Navy warships to the region to support the revolution. The new government of Panama, which the United States recognized, immediately signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the United States, granting the U.S. a strip of land known as the Panama Canal Zone, where the canal would be built. It granted the U.S. control of a strip of land known as the Panama Canal Zone, where the canal would be built. Under the terms of the treaty, the United States was given the rights to build, operate, and maintain the canal for a period of 100 years.

This was a controversial event, and it has been criticized for the U.S. intervention and support of the revolution and the subsequent treaty, which some considered a violation of the sovereignty of Colombia.

The construction of the canal was completed in 1914, and it was officially opened on August 15th of that year. The canal construction required a significant amount of human labour, and a large portion of the workforce came from Jamaica, Barbados, and other West Indian islands. The workers were brought to Panama as contract labor and faced difficult working conditions, racial discrimination, and poor living conditions.

The treaty with Panama was controversial and was criticized for granting the U.S. control of the canal zone and for the terms of the treaty, which many considered as unequal, and for the treatment of the mainly Caribbean workforce.

In 1977, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties were signed between the U.S. and Panama, which transferred the control of the canal from the U.S. to Panama on December 31st, 1999. Since then, the canal has undergone several expansions and improvements to increase its capacity and accommodate larger ships. Today, the canal remains a vital transportation link for global trade, with thousands of ships passing through its locks each year.

As early as 1903, the United States appropriated the Caribbean and Central America

US military interventions and occupations in Latin America: 1903 - 1934

President Theodore Roosevelt first used the phrase "speak softly and carry a big stick" in a letter to Henry L. Sprague in 1900 to describe his foreign policy approach emphasising peaceful diplomacy and the threat of military force. As early as 1903, but especially after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the United States considered the Caribbean as its own Mediterranean. It intervened there at will under this policy. The United States intervened in and occupied several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Nicaragua, Honduras, Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic, often under the justification of protecting American interests and stabilizing the region.[27][28][29][30][31]

The United States intervened in Cuba multiple times, including the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the intervention of 1906-1909. In 1914, the US also intervened in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the United States had more freedom to intervene in the Caribbean, and they did so in several countries including Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. In 1917, the United States purchased the Virgin Islands from Denmark. These interventions and occupations were often justified as a means to protect American interests and stabilize the region. They were carried out under the foreign policy approach of "speak softly and carry a big stick".

United States Military Occupations

The Monroe Doctrine, issued in 1823, established that the Americas were off-limits to further colonization by European powers and any attempt at intervention in the region would be considered a threat to the United States. The Roosevelt Corollary, issued in 1904, expanded on the Monroe Doctrine by stating that the United States would intervene in the affairs of nations in the Western Hemisphere to maintain stability and prevent European intervention in the region, particularly in cases of political or economic instability.

The United States military occupations in Latin America and the Caribbean in the early 20th century were often motivated by the fear of European interference in the region, particularly in regards to nations that had taken on debt from European powers. The US saw European intervention in these countries as a threat to American interests and stability in the region and therefore intervened to maintain control and prevent European intervention.

« Chronic injustice or powerlessness resulting from a general loosening of the rules of civilized society may ultimately require, in America or elsewhere, the intervention of a civilized nation and, in the Western Hemisphere, the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, albeit reluctantly, in flagrant cases of injustice and powerlessness, to exercise international policing power. »

— Theodore Roosevelt, Roosevelt Corollary[32]

The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine called on Latin American nations to stabilize their finances and political systems, and warned that if they failed to do so, the United States would intervene to maintain stability and protect American interests in the region. The United States viewed itself as having a duty to protect these smaller nations in the Western Hemisphere from external interference, particularly from European powers. This policy was often used as justification for military intervention and occupation in Latin American countries, particularly in cases of political or economic instability.

The United States developed a form of empire in the early 20th century through interventions and occupations in Latin America and the Caribbean, without maintaining traditional colonies as European powers did. This allowed the United States to exert influence and control over these regions without the costs associated with maintaining and administering traditional colonies. The US military interventions in the region were intended to maintain stability and protect American interests, rather than to establish formal colonies. Additionally, the US also used economic measures like the Platt Amendment of 1901 and the Dollar Diplomacy of the Taft Administration in 1909-1913 to exert influence in the region which extended its control without the cost of maintaining colonies.

The United States' approach to empire building in the early 20th century was characterized by political and economic control through interventions and occupations, punctuated by naval expeditions. The United States used military force in Latin America and the Caribbean to assert control and maintain stability in the region, often justified as a means to establish democracy. The American public and the international community were often presented with the argument that the judicious application of military force would lead to the establishment of democratic governments in the region. However, many of the interventions were primarily motivated by protecting American economic interests and preventing European interference in the region. The interventions were often carried out without the consent of the local population and in many cases, it led to the establishment of authoritarian regime that were more favorable to the US interests.

United States Navy expeditions played a significant role in the United States' approach to empire building in the early 20th century. Naval forces were often used to project American power and assert control in the Caribbean and Latin America. These expeditions were used to protect American interests and to maintain stability in the region. They were also used to support American interventions and occupations, such as the landing of US Marines in Mexico in 1914, and the occupation of Haiti in 1915. US naval expeditions also played a role in safeguarding American economic interests in the region, such as protecting American-owned banana plantations in Central America and the Caribbean. Additionally, the US navy was also used to protect the American-owned Panama Canal, which was a critical economic and strategic asset for the US.

Intervention Scenario

The phrase "I’m going to teach the nations of America how to elect good men", attributed to President Woodrow Wilson, reflects his belief that the United States had a duty to promote democracy in the region and that the US could use military force to intervene in the affairs of other nations to promote political stability and good governance. This belief was used to justify many of the US interventions and occupations in the Caribbean and Latin America during the early 20th century.[33]

However, it must be noted that this statement, while attributed to President Woodrow Wilson, is not something that he actually said. It is often quoted in a critical context, to highlight the perceived arrogance and condescension of the US in its approach to Latin America. It is important to remember that US interventions in the region were not always well received, and were often viewed as a form of imperialism and a violation of national sovereignty.

In reality, US interventions in the region were often motivated by economic and strategic interests, and were not always successful in promoting democracy or stability. They often led to human rights violations and other forms of repression, and did not always lead to the establishment of democratic governments. The US interventions in the region have left a mixed legacy, with both positive and negative effects on the nations and peoples of the Caribbean and Latin America.

Even within the United States, democracy was limited during the early 20th century. The labour movement faced severe repression, with many workers facing violence and intimidation for trying to unionise and demanding better working conditions. Women did not gain the right to vote until 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution. Even then, many women, particularly women of colour, faced significant barriers to voting and participating in politics. Black citizens in the South faced discrimination and were effectively disenfranchised until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which helped remove barriers to voting for black Americans.

The United States’ interventions in Latin America were often carried out to promote democracy and human rights, but the reality was often different. The US often supported authoritarian regimes that were seen as more favourable to American interests. These interventions were often motivated by economic and strategic considerations rather than a genuine desire to promote democracy and human rights. This contrast between the rhetoric and reality of US policy towards Latin America led to a legacy of mistrust and resentment towards the US in the region.

The United States’ understanding of democracy in Latin America during the early 20th century was often limited to a narrow, elitist view. The US government often supported political systems that were controlled by a small, wealthy elite, and did not truly reflect the will of the majority of the population. The US government often saw the "better class" or the "respectable element" as the only suitable leaders for Latin American countries. It did not consider the needs and desires of the working class, indigenous populations, and other marginalised groups. This approach led to a lack of genuine democracy and political representation in many Latin American countries, which in turn contributed to social and economic inequality and instability in the region. It also created a perception that US foreign policy in Latin America is motivated by self-interest rather than supporting the well-being of the nations in the region.

The racialisation of US foreign policy in Latin America during the early 20th century is an important aspect to consider. How the US government viewed and interacted with Latin American nations and peoples was often based on racist and paternalistic attitudes. Latin American countries were seen as "barbaric" and "uncivilised" in need of "training" and "taming" by the US government. This attitude was not limited to US foreign policy, but also reflected the broader racial dynamics within American society. The Ku Klux Klan, which had been re-established in 1915, was a white supremacist organisation that aimed to maintain the dominance of white Americans over other racial groups, particularly African Americans. The film "The Birth of a Nation," which was released in 1915, celebrated the Klan and perpetuated racist stereotypes about Black people. The fact that President Wilson, who was in office at the time, praised the film highlights the deep-seated racist attitudes within American society that also influenced US foreign policy in Latin America.

The United States’ policy of Dollar Diplomacy was an effort to prevent European powers from taking military action against Latin American nations that could not pay their debts. The strategy involved the US government encouraging American banks to assume the debts of European banks by guaranteeing the repayment of those debts. By doing so, the US government hoped to exert economic and financial influence over these nations and prevent European intervention in the region. It was also a way for the US to assert its own economic and political influence in the region and gain access to resources and markets. Dollar Diplomacy was implemented during the presidency of William Howard Taft (1909–1913) and continued under his successor, Woodrow Wilson (1913–1921).

A combination of economic, political, and strategic motives drove the United States’ military interventions in Latin America during this period. The First World War allowed the US to assert its regional dominance and prevent European powers from gaining a foothold there. The protection of American financial interests, including the repayment of loans, was a key factor in the US’s interventionist policy. Additionally, American businesses, particularly the United Fruit Company, had significant economic interests in the region, and the US government sought to protect those interests. The Panama Canal was also a strategic asset that the US sought to protect. The idea of the Caribbean as an "American Mediterranean" was also a driving force behind US intervention, as it reflected the growing naval power of the US and its desire to exert control over the region.

This provisional government is then tasked with implementing economic and political reforms that align with American interests, such as reducing tariffs on American goods, opening up the country’s natural resources to American companies, and ensuring the repayment of debts to American banks. The US military presence also serves to suppress any resistance to these changes, often using brutal force against those who protest or resist the occupation. The US military forces remain in the country until the provisional government has implemented the desired changes, and a new government that is friendly to American interests is in place. This pattern of intervention and occupation was repeated multiple times in various countries in Latin America between 1903 and 1934, with the US using military force to assert its economic and political dominance in the region.

These provisional governments were often authoritarian and were often backed by the military. They were in charge of imposing economic and political reforms, which were often unpopular with the local population. This led to widespread resistance and protests, which were often met with brutal repression by the US military. The US troops remained in control of the countries for several years and did not withdraw until they deemed that the countries were stable enough to govern themselves. These interventions have had a lasting impact on the region and have contributed to the mistrust and resentment towards the United States in many Latin American countries. During US military interventions and occupations in Latin America, high-ranking US officials often took control of customs and appropriated import-export taxes. These taxes were then paid to US banks, which used the funds to recover their loans to the intervened or occupied country. This allowed the US to exert control over the country’s economy and financial systems, further solidifying their control and dominance over the region. This approach was not limited to one specific country but it was a pattern and a strategy used across different countries in Latin America.

The customs and import-export taxes are often controlled by the US officials during the occupation period. These taxes are used to pay off the financial loans to US banks, ensuring that they are repaid. Additionally, controlling these taxes allows the US to exert economic control over the occupied country and ensure that its resources and industries are being used to benefit US interests. The Marines also prepare for the post-occupation period by training local law enforcement to protect the new regime and the interests of American businesses, such as large plantations and mines. They also often force the country to reform its constitution and hold national elections with a pre-determined winner that aligns with US interests.[34]

Instead, the focus is on controlling resources and ensuring debt repayment to US banks. These interventions are often justified as a means of spreading democracy and stability in the region, but in reality they are primarily driven by economic and political interests. Furthermore, the way the occupations were carried out, often with the installation of provisional governments and the suppression of civil liberties, suggests that the true intent was not to promote democracy but to exert control over these nations.

The United States has a long history of intervening in Latin American countries in order to protect its economic and strategic interests in the region. The interventions were often justified as a means of promoting democracy and stability. Still, in reality they were primarily focused on maintaining US control over the region’s resources and ensuring that the countries in question were politically and economically aligned with US interests. The US military and government officials played a key role in these interventions, often imposing their own policies and officials on the countries they occupied and taking control of customs and import-export taxes to ensure that US banks were repaid for their loans. This approach was very different from the colonial empires of European powers such as France and England, which involved the direct control and administration of colonies.

1933: Roosevelt and the Good Neighbor Policy

The Good Neighbor Policy was a foreign policy initiative implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. The policy sought to improve relations between the United States and Latin American countries by renouncing the use of military force to interfere in the affairs of other nations and promoting economic and cultural cooperation. This marked a shift away from the previous policy of intervention and domination in the region, known as the "Big Stick" policy, which previous presidents had implemented. The Good Neighbor Policy significantly changed the United States' relationship with Latin America and helped reduce tensions between the two regions.

The Great Depression significantly impacted Latin America, causing widespread economic hardship and political instability. Many countries in the region were forced to default on their debt payments, which led to a loss of confidence in their economies and governments. This led to a rise in political unrest and the emergence of populist and authoritarian leaders.

During this time, the United States under President Franklin D. Roosevelt adopted the Good Neighbor Policy, which rejected the use of military intervention in the affairs of other nations and instead focused on economic and cultural cooperation. This marked a departure from previous U.S. policy, which had often involved military intervention in Latin American countries to protect American economic interests. The Good Neighbor Policy helped to reduce tensions between the United States and Latin America and allowed for a more peaceful and cooperative relationship between the two regions.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated in his first inaugural address that "the definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention." He believed that the previous policy of intervention and domination in the affairs of other nations had created disorder and resentment towards the United States. Instead, he proposed the Good Neighbor Policy as a new approach to relations with Latin America, which emphasized economic and cultural cooperation and renounced the use of military force to interfere in the affairs of other nations. This marked a significant change in U.S. foreign policy and helped to improve relations with Latin America and reduce tensions between the two regions.

The United States was also deeply affected by the Great Depression, and its economy was struggling. The government was focused on addressing the economic crisis at home and did not have the resources or political will to intervene in the affairs of other nations. The Good Neighbor Policy was seen as a more realistic and pragmatic approach to relations with Latin America. The policy recognized the region's economic and political difficulties and sought to promote cooperation and mutual understanding rather than intervention and domination. Additionally, the policy was more in line with the US's own economic constraints, which restricted the amount of resources it could devote to foreign policy.

The Good Neighbor Policy can be seen as a change in the way the United States sought to maintain its influence and protect its interests in Latin America, rather than a rejection of these goals altogether. It did not question American hegemony or the protection of American interests in the region, but rather proposed a different approach to achieving these goals. Instead of using military intervention and force, the policy emphasized economic and cultural cooperation and mutual understanding between the United States and Latin America. The policy also sought to address the economic and political difficulties facing the region, in an effort to create a more stable and cooperative relationship. The Good Neighbor Policy was a pragmatic approach to US foreign policy, which sought to maintain US influence and protect US interests in the region while avoiding the past's costly and unpopular military interventions.

The previous policy of intervention and domination, often referred to as the "Big Stick" policy, had been ineffective in achieving its goals and had led to widespread resentment and hostility towards the United States in many Latin American countries. The policy had resulted in costly military interventions and support for authoritarian regimes, which had suppressed political and economic development and led to the rise of nationalist and protectionist sentiment. The policy had also created political and economic instability in the region, further damaging US-Latin American relations. President Roosevelt recognized that a change in policy was needed in order to improve relations with Latin America and protect American interests in the region. The Good Neighbor Policy was intended to address these issues by promoting economic and cultural cooperation, and renouncing the use of military force to interfere in the affairs of other nations.

President Roosevelt recognized that Europe's political and economic decline since the First World War had greatly reduced the need for the United States to intervene militarily in Latin America. With Europe no longer able to exert its influence in the region, the United States was now the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere. However, instead of using this dominance to intervene militarily, Roosevelt envisioned the use of economic and diplomatic pressure to bring Latin American nations into alignment with US needs. He believed that by promoting economic cooperation and cultural understanding, the United States could create a more stable and cooperative relationship with Latin America that would be beneficial for both regions. He understood that this was a more pragmatic and effective way to protect American interests in the region, rather than resorting to costly and unpopular military interventions.

In order to demonstrate its commitment to the Good Neighbor Policy, the United States signed a number of agreements with Latin American nations on non-intervention and non-interference in each other's affairs. These agreements were intended to reassure Latin American nations that the United States was no longer interested in intervening in their internal affairs and that it respected their sovereignty. However, the US government did not hesitate to interpret certain principles of non-intervention to its advantage. It argued that the active defense of the economic interests of US citizens and companies abroad was not an intervention in the internal affairs of other countries, but rather the protection of its citizens. This allowed the US government to continue to assert its influence and protect its interests in the region while maintaining the appearance of adhering to the principles of the Good Neighbor Policy.

One of the main components of the Good Neighbor Policy was the use of economic influence to promote cooperation and alignment with US needs. This included increasing trade between the United States and Latin America and providing loans and financial assistance to Latin American countries. In 1934, the federal government created the Export-Import Bank, which provided loans to American exporters to stimulate economic recovery in the United States and also helped finance large development projects in Latin America that American companies carried out. This allowed the US government to promote economic development in the region while also advancing American business interests.

In addition to providing loans and financial assistance, the US government also signed bilateral trade treaties with Latin American nations and gave them most-favored nation status. This resulted in increased trade between the United States and Latin America, further increasing dependence on the United States for many Latin American countries. This dependence on the United States was already substantial before the Great Depression, but it increased dramatically in the 1930s due to the economic crisis. This increased dependence benefited American companies by providing them with new markets and growth opportunities, which helped the United States emerge from the economic crisis. This way, the Good Neighbor policy was a new way to ensure and consolidate American hegemony in the region and help the US economy recover.

Promoting culture and the arts was also a component of the Good Neighbor Policy. The Roosevelt government sought to emphasize the cultural ties and shared history between the United States and Latin America, and to promote the idea of a unified "New World" that stood in contrast to the "Old World" of Europe. This was done through various cultural exchange programs, such as the sending of American artists and intellectuals to Latin America, and the funding of cultural institutions in the region. These programs were intended to improve cultural understanding between the United States and Latin America and promote a common identity and shared values between the two regions.

As part of the Good Neighbor Policy, the Roosevelt government sought to promote the idea that the Americas, led by the United States, were a bastion of democracy and freedom in contrast to the totalitarian regimes rising in Europe. The State Department created a cultural division to promote progress and understanding in the Americas, but also to promote a positive image of the United States. This was done through various cultural exchange programs, such as the sending of American artists and intellectuals to Latin America, and the funding of cultural institutions in the region. The goal was to improve cultural understanding between the United States and Latin America and to promote the idea of a common identity and shared values between the two regions. Also by promoting a positive image of the US, the government expected to strengthen the relationships with the other countries of the Americas, making the US look as a leader that was not only interested in its own benefits but also in the well-being and progress of the entire region.

The State Department's Cultural Division engaged in various activities to promote a positive image of the United States in Latin America as part of the Good Neighbor Policy. This included broadcasting radio programs in Latin America, publishing a widely distributed magazine, and controlling film production in Hollywood. It is not entirely accurate to say that the State Department "prohibited airing films that are critical of the United States." While the State Department did have some influence over Hollywood and its production of films, it did not have the power to prohibit outright the airing of films critical of the United States. However, it did use its influence to encourage the production of films that painted a positive image of the United States and its policies, and to discourage the production of films that might be seen as critical or negative. The goal was to create a positive perception of US in other countries and to avoid any negative impact of the US policies on its relations with other nations.

The Good Neighbor Policy did have some successes, such as the signing of the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States and the negotiation of several trade agreements with Latin American countries. However, the policy did not bring significant changes to the political situation in many Latin American countries, particularly those where pro-Washington dictators were already in power. In some cases, the US supported these dictators even as they engaged in human rights abuses and repression of political opposition. The US saw these leaders as a bulwark against communism, prioritising stability and anti-communism over democracy and human rights. This support was not consistent with the principle of non-interference and non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries, which was a key aspect of the Good Neighbor Policy.

Duvalier in Haiti, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, Somoza in Nicaragua, and Batista in Cuba were all pro-Washington dictators who came to power during or after the Good Neighbor Policy era. They were all known for their human rights abuses, repression of political opposition, and corruption. Duvalier, also known as "Papa Doc," was a dictator who ruled Haiti with an iron fist from 1957 to 1971, using his secret police, the Tonton Macoutes, to terrorize the population. Trujillo, who came to power in the Dominican Republic in 1930, was also known for his repression and human rights abuses, and was in power until his assassination in 1961. Somoza was the leader of Nicaragua from 1936 to 1956, and again from 1967 to 1972, and his regime was known for its repression and corruption. Batista, who came to power in Cuba in 1933, was a dictator who was overthrown in the Cuban Revolution of 1959.

While the US government officially supported the Good Neighbor Policy and claimed to be promoting democracy and human rights in the region, in practice, they often turned a blind eye to the abuses of these dictators. They continued to support them, to maintain stability and anti-communism in the region. This support was not consistent with the principle of non-interference and non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries, which was a key aspect of the Good Neighbor Policy.

Roosevelt is quoted as saying of Somoza “he is a son of a bitch but at least he is our son of a bitch".[35][36] This statement, attributed to Roosevelt, highlights the pragmatic approach of the Good Neighbor policy towards authoritarian leaders in Latin America. Despite recognizing their corrupt and oppressive nature, these leaders were still seen as useful allies in furthering American interests in the region. The quote exemplifies the United States' willingness to overlook human rights abuses and support autocratic rulers who were willing to align themselves with American policies and protect American economic interests. This approach contrasted the more traditional approach of military intervention and regime change.

While enriching themselves astronomically, these dictators ensure US domination and protect US economic interests in their country by muzzling the opposition and violently repressing the working classes.

Latin American Responses to Big Stick and Good Neighbor Policies

In response to the United States' Big Stick and Good Neighbor policies, Latin American countries had a range of reactions. Some countries, such as Mexico and Cuba, were critical of the policies and resisted U.S. intervention in their affairs. Others, such as Panama and Honduras, were more supportive of the policies and cooperated with the U.S. However, many Latin American countries felt that the policies did not adequately address their needs and concerns, and that the U.S. was more interested in maintaining its own interests in the region.

During the 1950s, the United States implemented its "Good Neighbor Policy" towards Latin America, which aimed to improve relations with the countries in the region and reduce U.S. intervention in their affairs. The policy was a departure from the previous "Big Stick" approach, which had been marked by military intervention and support for dictators.

The Good Neighbor Policy was seen as an attempt to address the growing anti-American sentiment in Latin America, which had been fueled by the U.S.'s previous policies. However, the policy did not necessarily bring an end to U.S. intervention in the region. The U.S. continued to intervene in the domestic affairs of several Latin American countries, such as Guatemala and Iran, in order to protect its economic and strategic interests.

In some cases, the Good Neighbor Policy led to improved relations between the U.S. and Latin America countries, and in other cases, it did not bring the desired results. For example, in Cuba, the U.S. support for the dictator Fulgencio Batista led to the Communist revolution led by Fidel Castro in 1959 which marked the start of a long-standing hostile relationship with the United States.

Mexico's oil industry in 1938. This move was met with resistance from foreign oil companies, particularly those from the United States, which had significant investments in the Mexican oil industry. The U.S. government initially threatened military intervention, but ultimately decided to renounce it and instead, used diplomatic and economic pressure to try to resolve the issue.

The nationalization of Mexico's oil industry was a significant moment in the country's history, as it marked the first time a Latin American government had taken control of a strategic industry that had been dominated by foreign companies. The move was widely popular among the Mexican people, and it helped to solidify the power of the Mexican state and promote economic nationalism.

The U.S. government, however, did not take kindly to the move and the diplomatic relations between the two countries were strained, with the U.S. imposing trade restrictions and sanctions on Mexico. Over time, the U.S. and Mexico were able to negotiate a settlement and reach a compensation agreement in 1941. This episode showed that the U.S. was willing to use diplomatic means instead of military intervention to protect its economic interests in the region, but it also demonstrated the tensions that existed between the two countries over issues of national sovereignty and economic control.

Indeed, the U.S. military interventions in Latin America were not carried out without resistance. In Haiti, for example, the U.S. occupied the country between 1915 and 1934, and faced resistance from the Cacos, a group of peasant guerillas who fought against the occupation. The Cacos were led by Charlemagne Peralte, who was ultimately killed by U.S. forces in 1919. The resistance movement continued even after the U.S. withdrawal and it took several more years for Haiti to fully regain its independence and stability.

Similarly, in Nicaragua, the U.S. intervened multiple times in the first half of the 20th century to support the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza and his family. One of the most notable opponents of the Somoza regime was Augusto Sandino, who led a guerrilla movement against the U.S. occupation and the Somoza dictatorship. Sandino was able to negotiate a peace agreement with the U.S. in 1933, but he was subsequently assassinated by Somoza's National Guard, which was trained and armed by the U.S.