From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

We are going to talk about the rise of the United States as an imperial power up to the politics of Big Stick and Good Neighbor.

Reminder

There is a push to the West and to the South with the war against Mexico and all this expansion during the first half of the 19th century took place through war, the purchase of territories and colonization.

This push and expansion was done in the name of two major doctrines, namely the Monroe Doctrine and the Manifest Destiny Doctrine which dominated all of American history after that mid-nineteenth century.

Around 1850, the map of today's United States was almost complete, the western border was conquered and then following the agreement with England in 1812, expansion northwards, i.e. to Canada, was no longer possible.

After the capture of northern Mexico, these territories were taken because they were relatively sparsely populated, but after that there was always the problem of the balance between slave and abolitionist states, which compromised any expansion southwards.

Private annexation attempts

There are, however, attempts at private annexation in those territories considered to be natural areas of the United States, including the Caribbean and Central America.

From 1849 to 1851, groups of adventurers landed in Cuba with the aim of annexing Cuba to the United States. William Walker occupied Nicaragua between 1855 and 1857 re-establishing slavery in order to attract planters from the southern United States. It was precisely because these private attempts risked tipping the balance in favour of slavery that they met with opposition from Washington and failed.

U.S. expansion continued to be suspended during the Civil War between 1861 and 1865, but it resumed just after slavery was abolished.

Expansion through the acquisition of counter territories

As early as 1867, the United States bought Alaska from Russia for just over $7 million, at the same time they took possession of the Midway Islands in the Pacific and in 1878 they acquired a coal station in the Samoan Islands.

With the purchase of Alaska and the acquisition of these islands, a different type of territorial expansion took place in the South Pacific; it was now a question of acquiring trading territories to facilitate the penetration by US entrepreneurs of new markets outside the country's borders at a time when there was a very strong revival of European, Russian and Japanese imperialism.

Basically, for the United States, in 1890, it was a question of expanding commercial markets, since it had become a great industrial and agricultural power with 76 million inhabitants now looking towards the seas and also towards the southern border of the United States, i.e. Mexico.

In Mexico, under Diaz, there were 15,000 Americans settled in the north of Mexico, but there is no longer any question of colonizing there; what they do is that they control the mines, the recent industry and part of the haciendas.

It is no longer a question of pushing back the border as was done during the conquest of the West by eliminating the Amerindians in order to facilitate colonization; it is understandable that it is because Mexico, but beyond Mexico, Central America are densely populated territories inhabited by inferior races and that even the white minority in these regions is questionable for Americans who advocate the "one drop of blood rule".[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

New conception of the Destiny Manifest

According to the dominant theory, absorbing these territories would make the United States regress; before, the Indians of the West could be massacred without any problem, but now this is no longer possible. Therefore, the annexation of these territories is no longer envisaged, but the exploitation of their resources in terms of raw materials and cheap labour.

Many politicians, theologians and strategists merge the Monroe and Manifest Destiny doctrines with Social Darwinism claiming that by being of moral and racial superiority, the divine destiny of Americans is to extend their domination and civilization over the entire hemisphere.

More concretely, around 1890, businessmen and entrepreneurs from the United States settled not only in Latin America but also in Hawaii. What is important to know is that these entrepreneurs, supposedly chosen by social Darwinism, did not act alone. They are generously supported by the U.S. federal government and public finances.

Under Alfred Maham, the United States developed a modern navy capable not only of protecting the coasts of the United States, but also of competing with the British Royal Navy, which had hitherto dominated the seas.

The aim was to protect the new American trading empire and to support Washington's overseas policy.

The first test of this navy will be in the Pacific in Hawaii, which was already at the time a place where many U.S. planters were growing sugar with a large number of slaves and workers from Asia.

In order to be able to continue to dominate this territory, in 1893 these planters organized a coup d'état supported by the United States Navy overthrowing the Queen's Royal Government; in 1898 the United States annexed this strategic island where they would later build the Pearl Harbour naval base.

Imperialism declared under President William McKinley: 1898, War against Spain

1898 is also and above all the year in which the United States under President William McKinley entered the war against Spain for control of Cuba.

At that time, Cuba already had many American planters where they had sugar cane plantations.

In this war against Spain Cuba will be the first target, but also Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

At the beginning of 1829, Spain lost all its eastern American colonies except Cuba and Puerto Rico because of the Haitian revolution and the white Creole elites were too afraid that a war of independence in their islands would trigger a massive revolt of their own slaves; in Cuba especially the elite has been profiting since the beginning of the 19th century from the fall of Santo Domingo, having become the first sugar-producing land on the continent - the new pearl of the West Indies thanks to 1.5 million African slaves imported between 1800 and 1850; this Creole elite does not want to risk its fortune in a war of independence either.

After the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865, Cuban planters launched a first war of independence in 1868 in which they were supported by many Afro-Cubans, notably General Antonio Maceo. This war will go on for 10 years without achieving independence, Spain abolished slavery in Cuba in 1886, but it was not until 1895 that Cubans launched a new war of independence under the intellectual leadership of Jose Martin and the military leadership of Maceo.

In spite of victories these two leaders died quickly, 1896 the situation seems to have reached an impasse; at that time the United States is going through an economic crisis and the economic circles are looking for new markets abroad and Cuba seems to be finally ripe to be seized, but to do so it is necessary to seize the public opinion of the United States.

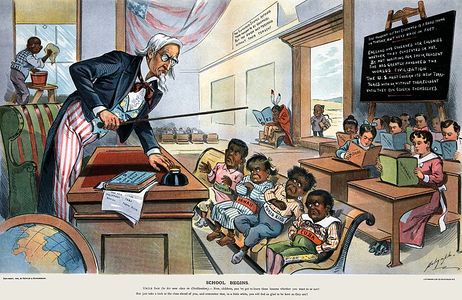

Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico [sic] and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. The caption reads: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!".

Washington sends a warship called the Maine to explode, killing 260 sailors and officers; even though Spain's responsibility was never proven, this is the pretext that the United States will use to start the war.

Spain is very quickly defeated and cedes almost all of what remains of its empire: Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines for $20 million. None of the islands will have a say in this treaty signing the beginning of U.S. imperialism per se or, in less brutal terms, "the civilizing mission of the white man".

The racism behind corporate America is out in the open. The United States transforms Puerto Rico into a protectorate, Cuba is militarily occupied until 1902, but the United States forces the Cuban Congress to approve the Platt amendment that limits Cuban sovereignty and authorizes the United States to intervene militarily to defend life, property and freedom in Cuba, which it will do several times.

With the Platt amendment, Washington is forcing Cuba to rent a military base at Guantánamo for almost $1,000 a year for almost perpetuity.

From 1900 it is also the Open Door Policy, i.e. the Open Door Policy already defined at the end of the 19th century in Asia requiring the imperial powers to respect the principle of equal trade opportunities for all nations.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

Cette politique devient la pierre angulaire de la politique étrangère des États-Unis c’est-à-dire que les États-Unis exigent l’ouverture des marchés aux compagnies étasuniennes puis ensuite le but est d’arriver à dominer ces marchés.

The Panama Canal

It is the Americas that remain their privileged zone of expansion, the Caribbean, Central America with the opening of a canal between the Atlantic and the Pacific at the centre of the scheme is something that has been advocated since the 1870s; for the politicians of the United States, it is the best way to dominate inter-oceanic trade and to prevent any attack on the territory of the United States.

It will be President Theodore Roosevelt who will realize this. He volunteered in Cuba in the rifles riders, when he was President of the United States he led the opening of the Panama Canal.

At that time Panama was a department of Colombia, but at the end of the 19th century Colombia was in the throes of one of its many civil wars and Roosevelt's government pushed the Panamanian rebels to declare the independence of Panama sending warships to ensure their victory.

Colombia gave in and in 1903 and the United States signed a treaty with the new nation of Panama obtaining the canal zone and 100 years of control of the canal, the canal was completed in 1914 thanks to a workforce that came mainly from Jamaica and Barbados.

As early as 1903, the United States appropriated the Caribbean and Central America

US military interventions and occupations in Latin America: 1903 - 1934

As early as 1903, but especially after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the United States considered the Caribbean as its own Mediterranean and intervened there at will: "speak softly and carry a big stick".[20][21][22][23][24]

The navy intervened a lot in Cuba, Mexico in 1914 and from the moment the Europeans entered the First World War then the United States could do whatever they wanted occupying Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and in 1917 they bought the Virgin Islands from Denmark.

United States Military Occupations

Behind the occupations there is still the Monroe doctrine, but supplemented by the corollary Roosevelt, which comes from the fear of interference by European powers that have lent money to the nations of Central America and the Caribbean; the European nations seeing that Central America and the Caribbean cannot repay this debt intervene militarily.

« Chronic injustice or powerlessness resulting from a general loosening of the rules of civilized society may ultimately require, in America or elsewhere, the intervention of a civilized nation and, in the Western Hemisphere, the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, albeit reluctantly, in flagrant cases of injustice and powerlessness, to exercise international policing power. »

— Theodore Roosevelt, Roosevelt Corollary[25]

This doctrine calls on Latin American nations to stabilize their finances and their regimes if they do not want to be the object of civilizing intervention by the United States. In addition, the United States arrogates to itself the mission of protecting these small nations.

Unlike France and England, the United States manages in these years to develop an empire without having many colonies, so it is a much cheaper empire to maintain.

It is an empire characterized by political and economic control punctuated by naval expeditions. In all cases except Mexico, the intervention is justified both to the American public and to the outside world by the argument that the judicious application of military force will lead to the establishment of democracy in the region.

Intervention Scenario

As Wilson cruelly expressed it « I'm going to teach the nations of America how to elect good men »[26]

Even in the United States democracy was limited, the labor movement was severely repressed, women did not vote until 1920 and blacks in the South until 1964.

What U.S. politicians imagine as democracy in Latin America are aristocratic republics where the only interests represented are of the respectable element of the "better class" and not of the "rabble.

All this is particularly interesting, because we see that there is a racialization of the relationship of US foreign policy which echoes the relationship between blacks and whites at the same time; the dominated are turbulent barbarians almost naked, but not dangerous that a good master has to train and tame to make them responsible adults; in the same period Ku Klux Klan develops notably through the film The Birth of a Nation acclaimed among others by President Wilson.

Firstly, the US interventions are aimed at preventing European powers from taking military action against Latin American nations that do not pay their debts. To this end, Washington is encouraging US banks to assume the debts of European banks by guaranteeing the repayment of debts; this is called Dollar Diplomacy.

As Europe plunges into the First World War, these interventions are intended to guarantee the American banks the repayment of financial loans, but also to guarantee the geopolitical domination of the United States in the region against the European powers, but also to protect the plantations, the mines belonging to American citizens on the continent and in particular everything belonging to the United Fruit Company, to protect the Panama Canal and to convert the Caribbean into an American Mediterranean.

The U.S. Army and Navy disembark with great pomp and circumstance in an indebted country, lay down its authorities without fighting, militarily occupy the country while installing a provisional government composed of high-ranking officers of the U.S. Army and a few docile representatives of the country's elite.

High-ranking U.S. officials took control of customs and appropriated the import-export taxes they paid to U.S. banks, which recovered their loans.

The Marines are also preparing for the post-occupation period so that the country remains under US control; they are training law enforcement to protect the new regime, large landowners and large plantations. Sometimes they force the country to reform its constitution, as in Haiti[27] which will have to remove the ban on land ownership for non-whites that has existed since the Haitian revolution, but they are also holding national elections with a virtually guaranteed winner from the United States.

The purpose of these occupations is not to bring democracy. When we look at the work of these occupations, almost nothing is invested by the United States in infrastructure that would be for national development and education, nor is anything done to train public officials to improve agriculture or change the political culture.

The aim is to assert US dominance in the region and to protect US economic and strategic interests in the region, be they banking or the United Fruit Company.

1933: Roosevelt and the Good Neighbor Policy

With the arrival of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt to power in 1933, Washington's policy toward Latin America seemed to change abruptly.

From 1930 to 1935, almost all of Latin America was shocked by the Great Depression and underwent political changes of more or less violent regimes, but Washington no longer responded with military intervention.

Roosevelt proclaims that unilateral intervention in the affairs of other nations creates disorder, but also aversion against the United States. He will turn his country towards the Good Neighbor policy.

It must be seen that since the United States itself is in the midst of the deepest economic crisis in its history, it cannot continue to apply the Big Stick policy, since in the 1930s it would have to intervene in almost all of Latin America, since there is political and social unrest in almost every country.

La Good Neighbor Policy est un avatar de la politique du Big Stick. En effet, Roosevelt ne met pas en question l’hégémonie américaine ni la protection des intérêts étatsuniens dans la région ; il propose un autre moyen d’assurer et de consolider cette suprématie.

Il constate que la politique menée jusqu’à là a été inefficace et coûteuse constatant qu’elle a suscité la montée du nationalisme et du protectionnisme ainsi qu’un rejet des États-Unis dans la plupart des pays d’Amérique latine.

Roosevelt voit aussi que le déclin de l’influence politique et économique de l’Europe depuis la Première Guerre mondiale a considérablement réduit le besoin pour les États-Unis d’intervenir militairement. Il envisage d’utiliser en priorité la pression économique et diplomatique afin d’obtenir l’alignement des nations latino-américaines sur les besoins des États-Unis.

Pour convaincre l’Amérique latine qu’il y a changement, Washington signe avec les nations latino-américaines des accords de non-intervention et de non-ingérence dans les affaires des uns et des autres ; toutefois, le gouvernement américain n’hésite pas à interpréter à son avantage certains principes de non-intervention en affirmant que la défense active des intérêts économiques des citoyens et des compagnies étasuniennes à l’étranger n’est pas une intervention dans les affaires intérieures d’autres pays, mais une simple protection de ses citoyens.

La nouvelle arme est l’influence économique d’abord par l’accroissement du commerce et depuis 1934 le gouvernement fédéral a créé une banque d’import – export qui accorde des prêts aux exportateurs étasuniens afin de stimuler la reprise économique aux États-Unis. Cette banque étatique fait aussi de gros projets de développement en Amérique latine réalisés par des entreprises étasuniennes.

En plus, Washington signe des traités de commerce bilatéraux avec les nations latino-américaines auxquels il donne le statut de nation la plus favorisée avec pour résultat la dépendance accrue de ces pays à l’égard des États-Unis qui était déjà assez substantielle avant 1929 et qui s’accroit dramatiquement dans les années 1930. Cette dépendance profite aux compagnies étasuniennes contribuant aux États-Unis à sortir de la crise économique.

La culture est le dernier volet de la politique du Good Neighbor ; le gouvernement de Roosevelt cherche à souligner l’unité du Nouveau Monde contre l’ancien.

Selon lui alors que l’Europe de la grande dépression succombe au totalitarisme, les Amériques défendent la justice et la démocratie. Pour cela, le département d’État crée une division culturelle dont le but est de promouvoir le progrès et l’entente dans les Amériques, mais surtout de promouvoir une image positive des États-Unis.

La division culturelle du département d’État diffuse des émissions de radio en Amérique latine, elle publie un magazine largement distribué, contrôle la production de film à Hollywood et interdit la diffusion de films qui critiquent les États-Unis.

La meilleure preuve que la politique de bon voisinage ne change pas grand-chose est que dans les années 1930 la presque totalité des pays qui ont subi le Big Sticks sont dirigés par des dictateurs pro-Washington issus des armées ou des gardes rurales formées sous l’occupation par les marines ; ce sont les Duvalier à Haïti, Rafael Trujillo en République Dominicaine Somoza au Nicaragua Batista à Cuba sont des exemples de ces hommes sortis de ces gardes rurales ou nationales qui deviennent présidents et dictateurs ou directement dictateur.

Roosevelt aurait dit de Somoza “he is a son of a bitch but at least he is our son of a bitch[28][29]”. Tout en s’enrichissant de façon astronomique, ces dictateurs assurent la domination étatsunienne et protègent les intérêts économiques étatsuniens dans leur pays en muselant l’opposition et en répriment violemment les classes laborieuses.

Réponses latino-américaines aux politiques du Big Stick et du Good Neighbor

Le rapport de force est fondamentalement inégal, dès 1950 les dernières tentatives de fonder une fédération latino-américaine ont échoué et l’immense région est divisée en plus de 20 nations différentes divisées et sans presque aucune communication entre elles.

Pendant la révolution mexicaine, le Mexique sous Cárdenas réussi à nationaliser sont industrie pétrolière tandis que les États-Unis renoncent à y intervenir militairement.

Ce qu’il faut voir aussi est que ces occupations militaires ne se font pas sans résistance. À Haïti, l’organisation des Cacos qui sont des paysans guerreros est matée dans le sang. Dans le cas de Augusto Sandino, à peine des accords conclus que le dictateur Somoza le fait assassiner au Nicaragua.

Immigration des Latino-Américains aux États-Unis

Finalement, sur la longue durée, les interventions militaires et le bon voisinage n’ont pas seulement facilité la pénétration économique des États-Unis en Amérique latine, mais elles ont aussi encouragé la pénétration démographique des Latino-Américains aux États-Unis.

Un siècle plus tard, ces immigrants hispaniques sont en train de changer non seulement la démographie, les rapports radicaux, la culture et la politique des États-Unis.

Annexes

- Bailey, Thomas A. (1980), A Diplomatic History of the American People 10th ed., Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-214726-2

- Barck, Jr., Oscar Theodore (1974), Since 1900, MacMilliam Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 0-02-305930-3

- Beale, Howard K. (1957), Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power, Johns Hopkins Press

- Berman, Karl (1986), Under the Big Stick: Nicaragua and the United States Since 1848, South End Press

- Bishop, Joseph Bucklin (1913), Uncle Sam's Panama Canal and World History, Accompanying the Panama Canal Flat-globe: Its Achievement an Honor to the United States and a Blessing to the World, Pub. by J. Wanamaker expressly for the World Syndicate Company

- Conniff, Michael L. (2001), Panama and the United States: The Forced Alliance, University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-2348-9

- Davis, Kenneth C. (1990), Don't Know Much About History, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-71252-0

- Gould, Lewis L. (1991), The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-0565-1

- Hershey, A.S. (1903), The Venezuelan Affair in the Light of International Law, University of Michigan Press

- LaFeber, Walter (1993), A Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations: The American Search for Opportunity. 1865 - 1913, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38185-1

- Perkins, Dexter (1937), The Monroe Doctrine, 1867-1907, Baltimore Press

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1913), Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, The Macmillan Press Company

- Zinn, Howard (1999), A People's History of the United States, Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-06-083865-5

- Congress and Woodrow Wilson’s, Military Forays Into Mexico. An Introductory Essay By Don Wolfensberger - Congress Project Seminar On Congress and U.S. Military Interventions Abroad - Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Monday, May 17, 2004

- Foreign Affairs,. (2015). The Great Depression. Retrieved 29 October 2015, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/1932-07-01/great-depression

- Dueñas Van Severen, J. Ricardo (2006). La invasión filibustera de Nicaragua y la Guerra Nacional. Secretaría General del Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana SG-SICA.

- Rosengarten, Jr., Frederic (1976). Freebooters must die!. Haverford House, Publishers. ISBN 0-910702-01-2.

- Scroggs, William O. (1974). Filibusteros y financieros, la historia de William Walker y sus asociados. Colección Cultural Banco de América.

- La guerra en Nicaragua, 1860, del propio William Walker, traducida al español en 1883 por el italo-nicaragüense Fabio Carnevalini y reeditada en 1974 y 1993.

- Obras históricas completas, [[1865]], de Jerónimo Pérez, reeditada en 1928 por Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya y más adelante en [[1974]] y [[1993]].

- Con Walker en Nicaragua, ([[1909]]), de James Carson Jamison, quien fue capitán de su ejército y estuvo en sus expediciones. * La Guerra Nacional. Centenario, 1956, de Ildefonso Palma Martínez, reeditada en 2006 en el Sesquicentenario de la Batalla de San Jacinto.

- El predestinado de ojos azules, [[1999]], de Alejandro Bolaños Geyer

- Investigación más completa sobre William Walker en el mundo

- Harrison, Brady. William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature. University of Georgia Press, August 2, 2004. ISBN 0-8203-2544-9. ISBN 978-0-8203-2544-6.

References

- ↑ "One Drop of Blood" by Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, July 24, 1994

- ↑ Dworkin, Shari L. The Society Pages. "Race, Sexuality, and the 'One Drop Rule': More Thoughts about Interracial Couples and Marriage"

- ↑ "Mixed Race America – Who Is Black? One Nation's Definition". www.pbs.org. Frontline. "Not only does the one-drop rule apply to no other group than American blacks, but apparently the rule is unique in that it is found only in the United States and not in any other nation in the world."

- ↑ Khanna, Nikki (2010). "If you're half black, you're just black: Reflected Appraisals and the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule". The Sociological Quarterly. 51 (5): 96–121. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.619.9359. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01162.x.

- ↑ Hickman, Christine B. “The Devil and the One Drop Rule: Racial Categories, African Americans, and the U.S. Census.” Michigan Law Review, vol. 95, no. 5, 1997, pp. 1161–1265. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1290008

- ↑ Schor, Paul. “From ‘Mulatto’ to the ‘One Drop Rule’ (1870–1900).” Oxford Scholarship Online, 2017, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199917853.003.0011

- ↑ Gómez, Laura E. “Opposite One-Drop Rules: Mexican Americans, African Americans, and the Need to Reconceive Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century Race Relations.” How the United States Racializes Latinos: White Hegemony and Its Consequences, by Cobas José A. et al., Routledge, 2016, p. 14

- ↑ Brown, Kevin D. “The Rise and Fall of the One-Drop Rule: How the Importance of Color Came to Eclipse Race.” Color Matters: Skin Tone Bias and the Myth of a Post-Racial America, by Kimberly Jade Norwood, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2014, p. 51

- ↑ Jordan, W. D. (2014). Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States. Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies, 1(1). Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91g761b3

- ↑ Scott Leon, Princeton University, 2011. Hypodescent: A History of the Crystallization of the One-drop Rule in the United States, 1880-1940 url: https://search.proquest.com/openview/333a0ac8590d2b71b0475f3b765d2366/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- ↑ Winthrop, Jordan D. “Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States.” Color Matters: Skin Tone Bias and the Myth of a Post-Racial America, by Kimberly Jade Norwood, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2014

- ↑ Esthus, Raymond A. "The Changing Concept of the Open Door, 1899-1910," Mississippi Valley Historical Review Vol. 46, No. 3 (Dec., 1959), pp. 435–454 JSTOR

- ↑ Hu, Shizhang (1995). Stanley K. Hornbeck and the Open Door Policy, 1919-1937. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29394-5.

- ↑ Lawrence, Mark Atwood/ “Open Door Policy”, Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, (online).

- ↑ McKee, Delber (1977). Chinese Exclusion Versus the Open Door Policy, 1900-1906: Clashes over China Policy in the Roosevelt Era. Wayne State Univ Press. ISBN 0-8143-1565-8.

- ↑ Moore, Lawrence. Defining and Defending the Open Door Policy: Theodore Roosevelt and China, 1901–1909 (2017)

- ↑ Otte, Thomas G. (2007). The China question: great power rivalry and British isolation, 1894-1905. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921109-8.

- ↑ Sugita, Yoneyuki, "The Rise of an American Principle in China: A Reinterpretation of the First Open Door Notes toward China" in Richard J. Jensen, Jon Thares Davidann, and Yoneyuki Sugita, eds. Trans-Pacific relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the twentieth century (Greenwood, 2003) pp 3–20 online

- ↑ Vevier, Charles. "The Open Door: An Idea in Action, 1906-1913" Pacific Historical Review 24#1 (1955), pp. 49-62 online.

- ↑ Martin, Gary. "Speak Softly And Carry a Big Stick"

- ↑ Martin, Gary. "Speak softly and carry a big stick"

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2019, September 16). Big Stick ideology. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 08:24, September 19, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Stick_ideology

- ↑ National Geographic Society. “Big Stick Diplomacy.” National Geographic Society, 18 July 2014, www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/sep2/big-stick-diplomacy/.

- ↑ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Big Stick Policy.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/event/Big-Stick-policy.

- ↑ Theodore Roosevelt, Roosevelt Corollary. (en) « Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power. »

- ↑ Statement to British envoy William Tyrrell (November 1913), explaining his policy on Mexico

- ↑ Constitution de 1918, présentée le 12 juin 1918. Constitution préparée par les États-Unis qui occupent le pays depuis 1915. Adoptée par plébiscite.

- ↑ Brainy Quote, FDR

- ↑ Blood on the Border: Prologue