« From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 221 : | Ligne 221 : | ||

[[Fichier:Panama Canal under construction, 1907.jpg|thumb|Construction work on the Gaillard Cup in 1907.]] | [[Fichier:Panama Canal under construction, 1907.jpg|thumb|Construction work on the Gaillard Cup in 1907.]] | ||

The idea of building a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Central America had been discussed since the 1870s as a way to improve trade and transportation between the two coasts of the Americas. The United States, in particular, had a significant interest in building the canal as it would greatly benefit the country's economy by reducing the time and cost of shipping goods between the East and West coasts. Additionally, the construction of the canal would also provide a strategic advantage in the event of a potential military conflict, allowing the United States to more easily move troops and resources between its two coasts. | |||

The United States began construction of the Panama Canal in 1904, and it was officially opened in 1914. The construction of the canal was a massive engineering undertaking, involving the excavation of thousands of cubic meters of earth, the construction of locks and dams, and the creation of a network of canals and lakes. The construction of the canal required a significant amount of resources, human labor and the relocation of thousands of people. It was considered one of the greatest engineering feats of the 20th century. | |||

President Theodore Roosevelt played a key role in the construction and opening of the Panama Canal. While he was not President at the time construction began in 1904, he took office in 1901 and was President until 1909. During his tenure, he strongly advocated for the construction of the canal and provided significant political and financial support to the project. | |||

Colombia | In addition, he helped to resolve a diplomatic crisis with Colombia (the country that controlled the region where the canal was built) and helped to establish the Panama Canal Zone, a strip of land that was controlled by the United States and used for the construction of the canal. Under his leadership, the United States acquired the rights to the land and began construction on the canal. He visited the construction site and was present at the opening of the canal in 1914. | ||

at the time the United States began construction on the Panama Canal, Panama was a department of Colombia. However, during the late 19th century, Colombia was experiencing a civil war, and the situation in Panama was unstable. The United States, under the leadership of President Theodore Roosevelt, supported the idea of Panamanian independence from Colombia in order to facilitate the construction of the canal. | |||

In 1903, the U.S. government helped to engineer a revolution in Panama, which resulted in the declaration of independence from Colombia. This was done by supporting and encouraging Panamanian rebels, and by sending U.S. Navy warships to the region to support the revolution. The new government of Panama, which was recognized by the United States, immediately signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the United States, granting the U.S. a strip of land known as the Panama Canal Zone, where the canal would be built. | |||

This was a controversial event, and it has been criticized for the U.S. intervention and support of the revolution and the subsequent treaty, which some considered as a violation of the sovereignty of Colombia. | |||

in 1903, the United States signed a treaty with the newly independent nation of Panama, known as the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which granted the U.S. control of a strip of land known as the Panama Canal Zone, where the canal would be built. Under the terms of the treaty, the United States was given the rights to build, operate, and maintain the canal for a period of 100 years. | |||

The construction of the canal was completed in 1914, and it was officially opened on August 15th of that year. The construction of the canal required a significant amount of human labor, and a large portion of the workforce came from Jamaica and Barbados, as well as other West Indian islands. The workers were brought to Panama as contract labor, and they faced difficult working conditions, racial discrimination, and poor living conditions. | |||

It's worth noting that the treaty with Panama was controversial and was criticized for granting the U.S. control of the canal zone and for the terms of the treaty which many considered as unequal, and for the treatment of the mainly Caribbean workforce. | |||

In 1977, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties were signed between the U.S and Panama, which transferred the control of the canal from the U.S to Panama on December 31st, 1999. Since then, the canal has undergone several expansions and improvements to increase its capacity and accommodate larger ships. Today, the canal remains a vital transportation link for global trade, with thousands of ships passing through its locks each year. | |||

=As early as 1903, the United States appropriated the Caribbean and Central America= | =As early as 1903, the United States appropriated the Caribbean and Central America= | ||

Version du 27 janvier 2023 à 23:37

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The United States began to rise as an imperial power in the late 19th century, following the conclusion of the Spanish-American War in 1898. The war resulted in the US acquiring control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines and marked the beginning of the US's emergence as a global power.

In the following years, the US intervened in various countries in the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico, Honduras, and Nicaragua, in order to protect American economic interests and maintain stability in the region. These interventions laid the foundation for the Big Stick Policy, which was articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in the early 1900s. The policy stated that the US would intervene in the affairs of Latin American countries in order to protect American economic interests and maintain stability in the region.

However, by the 1920s, the US was facing domestic economic challenges and many Americans were becoming increasingly isolationist and opposed to the idea of intervening in foreign affairs. Additionally, the Big Stick Policy had led to a number of interventions and occupations in Latin American countries, which had resulted in widespread resentment and hostility towards the US.

In response, President Herbert Hoover announced the Good Neighbor Policy, which stated that the US would no longer intervene in the affairs of Latin American countries and would instead seek to build friendly relations with them through cooperation and mutual respect. The Good Neighbor Policy marked a shift away from the interventionist policies of the past and towards a more peaceful and cooperative foreign policy.

Reminder

During the first half of the 19th century, the United States experienced significant territorial expansion, both to the west and to the south. This expansion was driven by a combination of factors, including the desire for new land, resources, and markets, as well as a belief in American exceptionalism and the "manifest destiny" of the US to expand its territory and influence.

One of the key ways in which the US expanded its territory during this time was through war. The most notable example is the Mexican-American War, which occurred between 1846 and 1848. The war was sparked by disputes over the boundary between Texas, which had recently been annexed by the US, and Mexico, and ultimately resulted in the US gaining control of large parts of what is now the American Southwest, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

The US also expanded its territory through the purchase of land. One of the most significant examples of this was the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, in which the US purchased a vast tract of land from France, which included present-day Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, parts of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana.

Additionally, the US also expanded through colonization, for example the Oregon trail, where thousands of American settlers migrated to the Pacific Northwest during the 1840s and 1850s, which led to the eventual American annexation of the territory.

Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny were two major doctrines that significantly shaped American foreign policy and territorial expansion during the 19th century.

President James Monroe issued the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, which stated that any attempts by European powers to colonize or interfere with the affairs of the newly independent nations of the Western Hemisphere would be viewed as a threat to the security and stability of the United States. It established the US as the dominant power in the Americas and helped to shape American foreign policy for the next century.

Manifest Destiny, on the other hand, was a belief that it was the God-given mission of the United States to expand its territory and influence across North America and to spread its system of government, economy and culture. This idea was used to justify the territory territorial expansion the annexation of Texas, the Mexican-American War, and the settlement of the American West.

Together, these two doctrines helped to shape American foreign policy and territorial expansion during the 19th century and beyond. The Monroe Doctrine helped to establish the US as the dominant power in the Americas, while Manifest Destiny provided a justification to the expansion and the spread of American influence.

By around 1850, the territorial expansion of the United States had reached its present-day boundaries, with the exception of Alaska, which was purchased from Russia in 1867. The western border of the US had been expanded through a combination of war, the purchase of territories, and colonization, including the Mexican-American War, the Louisiana Purchase, and the settlement of the American West.

In terms of expansion northwards, the boundary between the US and Canada was established through a series of treaties and agreements, including the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War, and the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, which ended the War of 1812. In addition, the agreement with England in 1818 established the 49th parallel as the border between the US and Canada from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains.

So, expansion northwards to Canada was no longer possible after the agreement with England in 1812. The map of today's UniAs a result, the States was almost complete by 1850, except Alaska, which was the last territory to be acquired.

After the capture of northern Mexico as a redue toxican-American War, the US acquired many territories, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma. These territories were relatively spared, and the US government saw them as opportunities for expansion and settlement.

However, the issue of slavery and the balance between slave and abolitionist states became a major political problem in the years following the war, and it complicated any further expansion southwards. The question of whether the new territories acquired from Mexico should allow slavery or not was a contentious issue, and it ultimately led to. The compromise of 1850 sought to resolve the issue by allowing California to enter the Union as a free state while the other territories were left to decide the question of slavery through popular sovereignty.

The Compromise of 1850 helped temporarily resolve the balance between slave and abolitionist states. Still, it prevented the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, which was largely caused by the expansion of slavery into the new territories. So, the question of the balance between slave and abolitionist states became a major significance for any expansion southwards, ultimately leading to the civil war.

Private annexation attempts

In addition to government-led expansion and territorial acquisitions, there were also private annexation attempts in territories considered to be natural areas of the United States, including the Caribbean and Central America. These private annexation attempts were often led by American business interests, such as railroad companies, mining companies, and agricultural interests, who sought to expand their operations and gain access to new markets and resources.

One example of private annexation was the attempt by American businessman William Walker to conquer and annex parts of Central America, including Nicaragua, in the 1850s. Walker, who was a former medical doctor, lawyer and journalist, led a group of American mercenaries in an effort to establish himself as the ruler of Nicaragua and to annex it to the United States. Walker's efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and he was executed by the government of Honduras in 1860.

The private annexation attempts by groups of adventurers in Cuba and by William Walker in Nicaragua were driven by a desire to expand the United States and to increase American economic and political influence in the region. These attempts were motivated by a variety of factors, including the desire for economic gain and the belief in the idea of American exceptionalism.

However, these attempts also risked tipping the balance in favor of slavery, which was a deeply divisive issue in the United States at the time. The annexation of Cuba or Nicaragua would have added new slave states to the Union, which would have further exacerbated the tensions between the slave and abolitionist states. As a result, these private annexation attempts met with opposition from the United States government and ultimately failed.

In addition, it's important to note that these private annexation attempts also met with opposition from local people and other countries in the region, as they would have resulted in the loss of sovereignty and control over their territories.

William Walker's actions were widely condemned in the United States, and he became a controversial figure. He was widely seen as a rogue adventurer who had acted without the support or authorization of the US government. His actions were seen as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, which was a US policy intended to prevent foreign colonization or any other kind of political control of the region by European powers.

The notion of American exceptionalism was a justification used to justify American expansionism, but it also led to the belief that American ways were superior to those of other nations, which led to a disregard for the people and cultures of other countries, which in turn led to resistance and opposition to American expansionism.

Despite his lack of success and his controversial legacy, William Walker's actions had a significant impact on the political and social history of Central America, and he remains a controversial figure in the region. His private annexation attempts were one of the many examples of American expansionism in the 19th century, which was driven by economic interests and a belief in the idea of American exceptionalism.

After his execution, many of his followers were captured, executed, or forced to leave the country. His actions were widely criticized in the United States, and he became a controversial figure. He was seen as a rogue adventurer who had acted without the support or authorization of the US government. His actions were seen as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, which was a US policy intended to prevent foreign colonization or any other kind of political control of the region by European powers.

His actions in Central America were also met with resistance and opposition from local people, and his legacy in the region is still debated by historians. Some view him as a heroic figure who sought to bring modernization and progress to the region, while others see him as a ruthless dictator who sought to impose his will on the people of Central America.

Another example of private annexation attempts was in Hawaii, where American planters and businessmen sought to annex the islands to the United States in order to gain access to the Hawaiian sugar market. The annexation of Hawaii was a complicated process, which involved the political and economic interests of many different actors, including American planters, merchants, and politicians, as well as the Hawaiian monarchy and local inhabitants.

In the late 19th century, American planters and businessmen had invested heavily in Hawaiian sugar plantations and had come to dominate the Hawaiian economy. They saw annexation as a way to gain access to the American market and to protect their investments from foreign competition. American politicians, such as President Cleveland, also saw Hawaii as a valuable strategic location, as it would be a valuable naval base for the United States.

The annexation of Hawaii was eventually achieved in 1898, following a coup d'etat that was supported by American interests. The annexation of Hawaii was accomplished by a joint resolution of Congress, which was signed into law by President McKinley. It was a controversial move, which was opposed by many Hawaiian nationalists and by some Americans who believed that annexation would undermine American democratic values and lead to the subjugation of a sovereign nation.

U.S. expansion was suspended during the Civil War between 1861 and 1865, as the country was focused on the conflict between the Union (north) and Confederacy (south) over issues such as slavery and states' rights. After the Civil War ended in 1865, the country was reunited and slavery was abolished with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

After the Civil War, the United States resumed its expansionist policies, with a renewed emphasis on economic growth and territorial expansion. The country continued to push westward, as the government sought to settle and develop the remaining western territories. This was done through a variety of means, including treaties with native tribes, the purchase of land from Mexico and other countries, and the annexation of new territories, such as Alaska in 1867.

Additionally, the United States also sought to expand its influence and control in other parts of the world, including the Caribbean and Central America, through various means such as the Big Stick Policy and the Good Neighbor Policy. The Big Stick Policy relied on economic and military pressure to assert American dominance, while the Good Neighbor Policy relied on diplomacy and cooperation to achieve the same goals. The United States also continued to pursue its expansionist policies in Asia and the Pacific.

Expansion through the acquisition of counter territories

The United States acquired Alaska from Russia in 1867 through a treaty of cession in which Russia sold the territory to the United States for $7.2 million. The acquisition of Alaska was met with mixed reactions in the United States, with some viewing it as a valuable acquisition of valuable natural resources. In contrast, others viewed it as a "waste of money" on an inhospitable and remote territory.

In 1867, the United States also acquired the Midway Islands in the Pacific Ocean. This was done through a guano-mining claim under the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which authorized American citizens to take possession of any unclaimed islands for the purpose of mining guano.

In 1878, the United States also acquired a coal station in the Samoan Islands in the Pacific. This was done in order to establish a coaling station for American naval ships in the Pacific and to protect American commercial interests in the region. The coal station was acquired through a treaty with the local Samoan leaders.

These acquisitions of Alaska, Midway Islands, and the Samoan Islands were part of a broader expansionist policy of the United States in the 19th century aimed at securing strategic locations, natural resources, and access to new markets. This expansion also aimed to project American power and influence in different regions and protect American commercial interests.

With the purchase of Alaska and the acquisition of the Midway Islands and the Samoan Islands, the United States began to focus on a different type of territorial expansion in the South Pacific. Instead of acquiring new territories for settlement or colonization, the United States began to acquire territories to facilitate trade and access to new markets.

Several factors drove this change in focus. One of the main reasons was the strong revival of European, Russian and Japanese imperialism in the late 19th century. As other imperial powers were expanding their territories and influence in different regions of the world, the United States sought to establish a presence in these regions in order to protect American commercial interests and to project American power and influence.

Another reason was the rapid industrialization and economic growth of the United States in the late 19th century. American entrepreneurs and businesses were looking for new markets and opportunities to expand their operations outside the country's borders. Acquiring trading territories in the South Pacific gave American businesses access to new markets, resources and opportunities.

In this new context, American foreign policy began to be framed by the concept of the Open Door Policy, which aimed to maintain the territorial integrity and political independence of China while also protecting American economic interests in the region, and the Big Stick Policy, which sought to extend American influence in the Caribbean and Central America through a show of military force and intervention.

In the late 19th century, the United States had become a major industrial and agricultural power with a rapidly growing population. With this expansion of industry and agriculture, American businesses and entrepreneurs were looking for new markets to sell their goods and services.

At the same time, the United States was also looking to extend its influence and protect its interests in the regions around its southern border, particularly Mexico. With the rapid industrialization and economic growth of the United States, it was also looking to expand its commercial markets in the Caribbean and Central America, where other imperial powers, such as European countries, Russia and Japan, were also seeking to establish a presence.

This drive to expand commercial markets and extend influence in the region was reflected in American foreign policy, which was characterized by the Open Door Policy and the Big Stick Policy. Both policies aimed at protecting American economic interests and projecting American power and influence in the region while also maintaining other countries' territorial integrity and political independence.

Under the rule of Porfirio Diaz in the late 19th century, Mexico had a significant population of American settlers, particularly in the northern regions of the country. These American settlers were primarily involved in the mining, industrial and agricultural sectors and played a significant role in the development of these industries in Mexico.

During this time, the United States had significant economic interests in Mexico and the American settlers were able to exert significant influence over the Mexican economy. Diaz's government was open to foreign investment and the American settlers were able to establish themselves as a powerful economic force in the region, especially in the mining, oil and railroad sectors.

However, it's worth noting that the American settlers were not interested in colonizing Mexico, instead, they were more focused on controlling the resources, such as mines, oil and other recent industry, and to some extent, the haciendas (farms), for the benefit of their own country. The United States was looking to gain access to Mexican resources and markets to fuel its own economic growth, rather than outright colonization.

During this time, the United States began to adopt a more assertive foreign policy, known as the Big Stick Policy, which emphasized the use of military force and economic pressure to assert its influence in the Americas and beyond. This policy was championed by President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed that the United States should play a more active role in world affairs and exert its power to promote stability and protect American interests. However, as the country entered the 20th century, the Big Stick Policy began to be criticized for its aggressive and interventionist approach, leading to the emergence of the Good Neighbor Policy under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This policy sought to improve relations with Latin American countries through diplomacy and mutual cooperation, rather than coercion and intervention. This change in foreign policy was driven by a growing recognition of the limitations of the Big Stick Policy and the desire to build stronger and more cooperative relationships with countries in the region.

This shift in American expansionism and imperialism during the late 19th century can be attributed to several factors, including a desire for new commercial markets, a belief in the superiority of the American way of life, and the influence of racist ideologies such as the "one drop of blood rule". The United States sought to expand its influence by acquiring territories that would serve as trading partners and provide access to new markets, rather than through colonization and the displacement of indigenous populations as was done during the conquest of the West. This shift in strategy also reflected a growing belief in the inferiority of non-white populations, which influenced American attitudes towards expansion in Latin America and the Caribbean.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

New conception of the Destiny Manifest

This new conception of Manifest Destiny, which emerged in the late 19th century, focused on economic expansion rather than territorial expansion. American businesses and corporations sought to gain access to resources and markets in other countries, while also seeking to exert political and economic influence over these nations. This shift in American foreign policy was reflected in the new doctrine of the "Big Stick" and the "Good Neighbor" policy, which emphasized the use of economic and political power to exert influence over other countries, rather than outright annexation or military conquest.

This belief in American superiority led to the justification of various actions taken by the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the annexation of Hawaii and the Spanish-American War, which led to the acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. It also played a role in the intervention in Latin American countries, such as the support for the overthrow of democratically-elected governments in favor of authoritarian leaders who were more amenable to American interests. This belief in American exceptionalism and the idea of spreading American values and institutions to other nations is still present in American foreign policy to this day.

In the late 19th century, the concept of Social Darwinism emerged and played a significant role in shaping the United States' policy of territorial expansion and economic domination in Latin America and the Pacific. Social Darwinism, a belief that the strong should prevail and that certain races were superior to others, was used to justify the subjugation of so-called "inferior" peoples and the acquisition of their territories. Businessmen and entrepreneurs from the United States, who were seen as the "fittest" and chosen by Social Darwinism, were generously supported by the U.S. federal government and public finances in their efforts to expand American influence and control over resources in Latin America, Hawaii and other parts of the world.

This support from the government and public finances took various forms, such as subsidies for shipping and communication infrastructure, military protection for American interests, and the use of diplomacy to open up markets and protect American investments. In addition, the U.S. government also supported these entrepreneurs by creating a favorable legal and political environment for them to operate in, through the use of treaties, trade agreements, and other forms of international law. Overall, this support from the U.S. government allowed American entrepreneurs to expand their economic and political influence in these territories, and played a significant role in the continued expansion of the United States throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.es.

Alfred Thayer Mahan, a United States Navy flag officer and geostrategist, wrote seminal works on the importance of naval power in determining the rise and fall of nations. His most notable publication, "The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783" (1890), posited that control of the seas through a formidable navy is a crucial factor in the international relations and global power dynamics. The aim was to protect the new American trading empire and to support Washington's overseas policy by allowing the US to maintain a robust naval presence in the international waters, which would protect American commerce and interests. Mahan's ideas had a significant impact on the naval policies and strategic thinking of the United States, in which he advocated for a strong navy that would be capable of competing with the British Royal Navy, which had hitherto dominated the seas. Mahan's ideas were particularly influential during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the United States sought to assert itself as a major naval power.

Mahan's ideas on naval power and the need for a strong navy to protect American interests and commerce greatly influenced the development of the United States Navy. The Navy's focus was on maintaining a strong presence in international waters, particularly in the Atlantic and Caribbean, and competing with European powers such as Britain. The United States Navy, under the influence of Mahan's ideas, also focused on building a strong battleship fleet and developing coaling stations and naval bases around the world to support its operations. The Navy also placed emphasis on naval education and training for its officers and sailors. Additionally, the Navy played a significant role in the Spanish-American War of 1898, which marked the emergence of the United States as a world power and further solidified the importance of a strong navy. The Navy continues to play a vital role in protecting American interests and providing security in international waters.

In the late 19th century, the United States Navy played a significant role in the history of Hawaii. In the 1880s, the U.S. government became increasingly interested in the islands as a potential naval base and coaling station. The U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, based in California, had been using the islands for refueling and repairs for many years. The U.S. government also became concerned about the potential threat of other foreign powers, such as Germany and Japan, to American interests in Hawaii.

In 1887, the U.S. government negotiated a treaty with Hawaii's monarch, King Kalakaua, which granted the U.S. the exclusive right to establish a naval base at Pearl Harbor. The U.S. Navy established a coaling station and repair facility at Pearl Harbor, which would become one of the most important naval bases in the Pacific.

In addition to its activities in Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy also played a role in the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. A group of American and European businessmen, known as the Hawaiian League, overthrew Queen Liliuokalani and established a provisional government. The U.S. Navy provided military support to the provisional government, and the U.S. government later annexed Hawaii as a territory in 1898.

The role of the US Navy in Hawaii in the 1880s was very important in the establishment of naval base and coaling station and also in the annexation of Hawaii as a territory of the US.

Imperialism declared under President William McKinley: 1898, War against Spain

The Spanish-American War began in 1898 and was a conflict between the United States and Spain. The U.S. declared war on Spain following the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, which was blamed on Spain. The war was fought primarily in Cuba and the Philippines, with the U.S. ultimately victorious. As a result, Spain ceded control of Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States, and the Philippines were sold to the U.S. for $20 million. The war marked a turning point in U.S. history as it marked the country's emergence as a world power.

The Spanish-American War occurred during the presidency of William McKinley, who served as President of the United States from 1897 to 1901. The war was one of the major events of his presidency, and it marked a significant turning point in U.S. foreign policy and international relations. The victory in the war and the acquisition of new territories, such as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, solidified the United States' status as a world power.

Cuba had been an important source of sugar for the United States for many years before the Spanish-American War. American planters and investors had established large sugar cane plantations in Cuba, which relied heavily on the labor of enslaved and later indentured Afro-Cuban workers. The U.S. had a strong economic interest in maintaining control of the island, in part because of the sugar trade, and this was one of the factors that led to the conflict with Spain. The war resulted in the end of Spanish control of the island and the eventual establishment of an independent Cuba, although the US maintained significant influence over the island throughout the 20th century.

The Spanish-American War was fought primarily in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The U.S. had declared war on Spain following the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, which was blamed on Spain, and the main objective of the war was to gain control of Cuba. The U.S. forces quickly gained control of the island, and Spain soon agreed to a ceasefire. As part of the peace agreement, Spain ceded control of Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States, and the Philippines were sold to the U.S. for $20 million. The war marked a significant turning point in U.S. foreign policy and international relations, as it marked the country's emergence as a world power.

Spain lost most of its American colonies in the early 19th century, with the exception of Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791, led to the independent Republic of Haiti in 1804, and the loss of the colony of Saint-Domingue, which was a major source of wealth for Spain. The Creole elite in Cuba and Puerto Rico, primarily white landowners and slaveholders, worried that a war of independence in their islands would lead to a similar revolt by enslaved people, as happened in Haiti.

In the 19th century, Cuba's economy was largely based on sugar production, and the island had become a major sugar producer in the Americas. The Creole elite had become wealthy through the profitable sugar trade and the importation of enslaved Africans to work on the plantations. They were unwilling to risk their wealth and status in a war of independence. The island of Cuba remained a Spanish colony until the Spanish-American War of 1898, when it was ceded to the United States as part of the peace treaty following the war.

After the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865, many Cubans, including Afro-Cubans, began to call for independence from Spain. In 1868, a group of planters and intellectuals led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes launched a war for independence known as the Ten Years' War. The war was fought primarily by Creole landowners and their enslaved and later indentured Afro-Cuban workers. It was supported by many Afro-Cubans, including General Antonio Maceo, who became a key leader in the war. However, the war was ultimately unsuccessful and was ended in 1878 with the Pact of Zanjón, which granted some autonomy to Cuba but did not bring about independence.

In 1886, Spain abolished slavery in Cuba, and in 1895, Cubans launched a new war for independence, known as the War of Independence. This war was led by José Martí and Antonio Maceo, both of whom had fought in the Ten Years' War. The war continued until 1898 when Spain ceded control of the island to the United States as part of the peace treaty following the Spanish-American War. The war of 1895-1898 is also known as the Cuban War of Independence.

Despite some initial successes, the War of Independence led by José Martí and Antonio Maceo, ended without achieving independence for Cuba. Martí died in 1895, and Maceo died in 1896, leaving the independence movement without their key leaders. The war had reached a stalemate by that time, and the situation in Cuba had become a source of concern for the United States.

At the time, the United States was going through an economic crisis, and many American businesses and politicians were looking for new markets abroad. With its strategic location and growing economy, Cuba was seen as a potential market for American goods and an opportunity for American businesses to invest. However, to justify a takeover of the island, it was necessary to gain the support of the American public. This was achieved by spreading false information about the state of the war and the situation in Cuba, portraying the Spanish as brutal oppressors and the Cuban independence fighters as heroic freedom fighters. This led to a wave of public sympathy for the Cuban cause and support for the U.S. intervention.

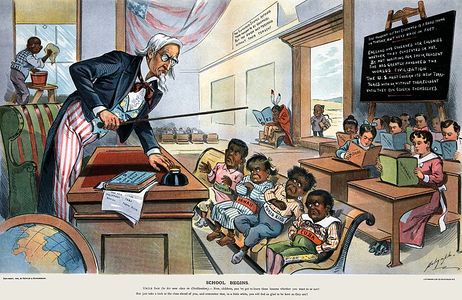

Caricature showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Porto Rico and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. The caption reads: "School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!".

In 1898, the United States declared war on Spain and quickly defeated the Spanish forces in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. As a result, Spain ceded control of these territories to the United States in the Treaty of Paris, which was signed on December 10, 1898. The United States paid Spain $20 million for the territories.

The cession of these territories marked the beginning of American imperialism, as the United States now controlled a significant amount of land and people outside of its own borders. The U.S. government justified the takeover of these territories as a "civilizing mission" to bring the benefits of American democracy and civilization to the peoples of these lands. However, this justification was often used to justify exploitative and oppressive policies towards the peoples of these territories, particularly in the Philippines where the US fought a brutal war to suppress the independence movement.

The United States transformed Puerto Rico into a protectorate and imposed a military government on Cuba until 1902, when it was officially declared independent. However, the United States maintained significant control over Cuban affairs through the Platt Amendment, which was added to the Cuban Constitution in 1901. This amendment limited Cuban sovereignty and granted the United States the right to intervene militarily in Cuba to defend American interests, including protecting life, property, and freedom.

The racism behind corporate America was indeed out in the open, as the U.S. government and American businesses had a vested interest in maintaining control over these territories, and their resources, labour, and markets. The U.S. government and American businesses often justified their actions by claiming they were helping to "civilize" the inhabitants of these territories. However, it was primarily driven by economic and strategic interests, with little regard for the rights and well-being of the people living in these territories.

The Platt Amendment gave the United States the right to intervene militarily in Cuba to defend American interests and also included a provision for the establishment of a naval base in Cuba. This led to the United States leasing land from Cuba to establish the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, which is located in the Guantanamo Bay area of southeastern Cuba. The United States has maintained control of this base since 1903, paying an annual rent of $2,000 to the Cuban government until 1934 when the Cuban government, under pressure from the US, agreed to terminate the rent payments. Since then the US has refused to pay rent or negotiate a new agreement with the Cuban government. The base remains a contentious issue between the two countries, with the Cuban government demanding the return of the base to Cuban control and the United States maintaining that the base is necessary for national security.

The Open Door Policy, also known as the "Open Door Notes" was a set of principles put forward by the United States in the late 19th century to ensure that all nations would have equal trading opportunities in China. The policy was first proposed by U.S. Secretary of State John Hay in 1899 and 1900 in a series of diplomatic notes sent to major world powers. The policy was intended to counter the actions of imperial powers, such as Russia, Germany, France and Japan, who were seeking to carve out exclusive spheres of influence in China. The Open Door Policy stated that all countries should have equal access to trade and investment opportunities in China and that the territorial integrity of China should be preserved. While the policy was primarily directed at China, it had a broader significance as it reflected the U.S. desire to maintain an open, multi-polar world order and promote American economic interests in Asia and worldwide.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

The Open Door Policy became a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy, with the goal of ensuring that American companies had equal access to markets around the world. The United States used its economic and military power to influence the policies of other countries in order to open their markets to American goods and investments. As the US economy grew and American companies expanded overseas, the US government sought to establish a favourable economic environment for these companies, often at the expense of the interests of other countries. This often led to the US government using its influence to promote policies that would benefit American companies while undermining the economies of other countries. The Open Door Policy laid the foundation for the US economic expansion overseas and the US efforts to dominate global markets that continue to this day.

The Panama Canal

The idea of building a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Central America had been discussed since the 1870s as a way to improve trade and transportation between the two coasts of the Americas. The United States, in particular, had a significant interest in building the canal as it would greatly benefit the country's economy by reducing the time and cost of shipping goods between the East and West coasts. Additionally, the construction of the canal would also provide a strategic advantage in the event of a potential military conflict, allowing the United States to more easily move troops and resources between its two coasts.

The United States began construction of the Panama Canal in 1904, and it was officially opened in 1914. The construction of the canal was a massive engineering undertaking, involving the excavation of thousands of cubic meters of earth, the construction of locks and dams, and the creation of a network of canals and lakes. The construction of the canal required a significant amount of resources, human labor and the relocation of thousands of people. It was considered one of the greatest engineering feats of the 20th century.

President Theodore Roosevelt played a key role in the construction and opening of the Panama Canal. While he was not President at the time construction began in 1904, he took office in 1901 and was President until 1909. During his tenure, he strongly advocated for the construction of the canal and provided significant political and financial support to the project.

In addition, he helped to resolve a diplomatic crisis with Colombia (the country that controlled the region where the canal was built) and helped to establish the Panama Canal Zone, a strip of land that was controlled by the United States and used for the construction of the canal. Under his leadership, the United States acquired the rights to the land and began construction on the canal. He visited the construction site and was present at the opening of the canal in 1914.

at the time the United States began construction on the Panama Canal, Panama was a department of Colombia. However, during the late 19th century, Colombia was experiencing a civil war, and the situation in Panama was unstable. The United States, under the leadership of President Theodore Roosevelt, supported the idea of Panamanian independence from Colombia in order to facilitate the construction of the canal.

In 1903, the U.S. government helped to engineer a revolution in Panama, which resulted in the declaration of independence from Colombia. This was done by supporting and encouraging Panamanian rebels, and by sending U.S. Navy warships to the region to support the revolution. The new government of Panama, which was recognized by the United States, immediately signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the United States, granting the U.S. a strip of land known as the Panama Canal Zone, where the canal would be built.

This was a controversial event, and it has been criticized for the U.S. intervention and support of the revolution and the subsequent treaty, which some considered as a violation of the sovereignty of Colombia.

in 1903, the United States signed a treaty with the newly independent nation of Panama, known as the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which granted the U.S. control of a strip of land known as the Panama Canal Zone, where the canal would be built. Under the terms of the treaty, the United States was given the rights to build, operate, and maintain the canal for a period of 100 years.

The construction of the canal was completed in 1914, and it was officially opened on August 15th of that year. The construction of the canal required a significant amount of human labor, and a large portion of the workforce came from Jamaica and Barbados, as well as other West Indian islands. The workers were brought to Panama as contract labor, and they faced difficult working conditions, racial discrimination, and poor living conditions.

It's worth noting that the treaty with Panama was controversial and was criticized for granting the U.S. control of the canal zone and for the terms of the treaty which many considered as unequal, and for the treatment of the mainly Caribbean workforce.

In 1977, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties were signed between the U.S and Panama, which transferred the control of the canal from the U.S to Panama on December 31st, 1999. Since then, the canal has undergone several expansions and improvements to increase its capacity and accommodate larger ships. Today, the canal remains a vital transportation link for global trade, with thousands of ships passing through its locks each year.

As early as 1903, the United States appropriated the Caribbean and Central America

US military interventions and occupations in Latin America: 1903 - 1934

As early as 1903, but especially after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the United States considered the Caribbean as its own Mediterranean and intervened there at will: "speak softly and carry a big stick".[27][28][29][30][31]

The navy intervened a lot in Cuba, Mexico in 1914 and from the moment the Europeans entered the First World War then the United States could do whatever they wanted occupying Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and in 1917 they bought the Virgin Islands from Denmark.

United States Military Occupations

Behind the occupations there is still the Monroe doctrine, but supplemented by the corollary Roosevelt, which comes from the fear of interference by European powers that have lent money to the nations of Central America and the Caribbean; the European nations seeing that Central America and the Caribbean cannot repay this debt intervene militarily.

« Chronic injustice or powerlessness resulting from a general loosening of the rules of civilized society may ultimately require, in America or elsewhere, the intervention of a civilized nation and, in the Western Hemisphere, the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, albeit reluctantly, in flagrant cases of injustice and powerlessness, to exercise international policing power. »

— Theodore Roosevelt, Roosevelt Corollary[32]

This doctrine calls on Latin American nations to stabilize their finances and their regimes if they do not want to be the object of civilizing intervention by the United States. In addition, the United States arrogates to itself the mission of protecting these small nations.

Unlike France and England, the United States manages in these years to develop an empire without having many colonies, so it is a much cheaper empire to maintain.

It is an empire characterized by political and economic control punctuated by naval expeditions. In all cases except Mexico, the intervention is justified both to the American public and to the outside world by the argument that the judicious application of military force will lead to the establishment of democracy in the region.

Intervention Scenario

As Wilson cruelly expressed it « I'm going to teach the nations of America how to elect good men »[33]

Even in the United States democracy was limited, the labor movement was severely repressed, women did not vote until 1920 and blacks in the South until 1964.

What U.S. politicians imagine as democracy in Latin America are aristocratic republics where the only interests represented are of the respectable element of the "better class" and not of the "rabble.

All this is particularly interesting, because we see that there is a racialization of the relationship of US foreign policy which echoes the relationship between blacks and whites at the same time; the dominated are turbulent barbarians almost naked, but not dangerous that a good master has to train and tame to make them responsible adults; in the same period Ku Klux Klan develops notably through the film The Birth of a Nation acclaimed among others by President Wilson.

Firstly, the US interventions are aimed at preventing European powers from taking military action against Latin American nations that do not pay their debts. To this end, Washington is encouraging US banks to assume the debts of European banks by guaranteeing the repayment of debts; this is called Dollar Diplomacy.

As Europe plunges into the First World War, these interventions are intended to guarantee the American banks the repayment of financial loans, but also to guarantee the geopolitical domination of the United States in the region against the European powers, but also to protect the plantations, the mines belonging to American citizens on the continent and in particular everything belonging to the United Fruit Company, to protect the Panama Canal and to convert the Caribbean into an American Mediterranean.

The U.S. Army and Navy disembark with great pomp and circumstance in an indebted country, lay down its authorities without fighting, militarily occupy the country while installing a provisional government composed of high-ranking officers of the U.S. Army and a few docile representatives of the country's elite.

High-ranking U.S. officials took control of customs and appropriated the import-export taxes they paid to U.S. banks, which recovered their loans.

The Marines are also preparing for the post-occupation period so that the country remains under US control; they are training law enforcement to protect the new regime, large landowners and large plantations. Sometimes they force the country to reform its constitution, as in Haiti[34] which will have to remove the ban on land ownership for non-whites that has existed since the Haitian revolution, but they are also holding national elections with a virtually guaranteed winner from the United States.

The purpose of these occupations is not to bring democracy. When we look at the work of these occupations, almost nothing is invested by the United States in infrastructure that would be for national development and education, nor is anything done to train public officials to improve agriculture or change the political culture.

The aim is to assert US dominance in the region and to protect US economic and strategic interests in the region, be they banking or the United Fruit Company.

1933: Roosevelt and the Good Neighbor Policy

With the arrival of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt to power in 1933, Washington's policy toward Latin America seemed to change abruptly.

From 1930 to 1935, almost all of Latin America was shocked by the Great Depression and underwent political changes of more or less violent regimes, but Washington no longer responded with military intervention.

Roosevelt proclaims that unilateral intervention in the affairs of other nations creates disorder, but also aversion against the United States. He will turn his country towards the Good Neighbor policy.

It must be seen that since the United States itself is in the midst of the deepest economic crisis in its history, it cannot continue to apply the Big Stick policy, since in the 1930s it would have to intervene in almost all of Latin America, since there is political and social unrest in almost every country.

The Good Neighbor Policy is an avatar of the Big Stick policy. Indeed, Roosevelt does not question American hegemony or the protection of American interests in the region; he proposes another way to ensure and consolidate this supremacy.

He notes that the policy pursued so far has been ineffective and costly, leading to the rise of nationalism and protectionism and a rejection of the United States in most Latin American countries.

Roosevelt also sees that the decline in Europe's political and economic influence since the First World War has greatly reduced the need for the United States to intervene militarily. He envisions the priority use of economic and diplomatic pressure to bring Latin American nations into alignment with US needs.

To convince Latin America that change is taking place, Washington signs agreements with Latin American nations on non-intervention and non-interference in each other's affairs; however, the US government does not hesitate to interpret certain principles of non-intervention to its advantage by asserting that active defence of the economic interests of US citizens and companies abroad is not an intervention in the internal affairs of other countries, but merely the protection of its citizens.

The new weapon is economic influence, first through increased trade, and since 1934 the federal government has created an import-export bank that provides loans to U.S. exporters to stimulate economic recovery in the United States. This state bank also makes large development projects in Latin America carried out by American companies.

In addition, Washington signed bilateral trade treaties with Latin American nations and gave them most-favored nation status, resulting in increased dependence on the United States that was already substantial before 1929 and increased dramatically in the 1930s. This dependence benefits the American companies that help the United States emerge from the economic crisis.

Culture was the final component of the Good Neighbor policy; the Roosevelt government sought to emphasize the unity of the New World against the Old.

As the Europe of the Great Depression succumbs to totalitarianism, the Americas are defending justice and democracy, he said. To that end, the State Department is creating a cultural division whose goal is to promote progress and understanding in the Americas, but above all to promote a positive image of the United States.

The State Department's Cultural Division broadcasts radio programs in Latin America, publishes a widely distributed magazine, controls film production in Hollywood, and prohibits the airing of films that are critical of the United States.

The best evidence that the Good Neighbor Policy does not make much difference is that in the 1930s almost all of the countries that suffered from the Big Sticks were ruled by pro-Washington dictators from armies or rural guards trained under occupation by Marines ; the Duvalier in Haiti, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic Somoza in Nicaragua, Batista in Cuba are examples of those men who come out of these rural or national guards and become presidents and dictators or directly dictators.

Roosevelt is quoted as saying of Somoza “he is a son of a bitch but at least he is our son of a bitch[35][36]”. While enriching themselves astronomically, these dictators ensure US domination and protect US economic interests in their country by muzzling the opposition and violently repressing the working classes.

Latin American Responses to Big Stick and Good Neighbor Policies

The balance of power is fundamentally unequal, as early as 1950 the last attempts to found a Latin American federation failed and the immense region is divided into more than 20 different nations with almost no communication between them.

During the Mexican revolution, Mexico under Cárdenas succeeded in nationalizing its oil industry, while the United States renounced military intervention.

What must also be seen is that these military occupations are not carried out without resistance. In Haiti, the organization of the Cacos, who are peasant guerreros, is matted in blood. In the case of Augusto Sandino, no sooner had the agreements been concluded than dictator Somoza had him assassinated in Nicaragua.

Immigration of Latin Americans to the United States

Finally, over the long term, military interventions and good neighbourliness not only facilitated the economic penetration of the United States into Latin America, but also encouraged the demographic penetration of Latin Americans in the United States.

A century later, these Hispanic immigrants are changing not only the demographics, but also the radical relationships, culture and politics of the United States.

Annexes

- Bailey, Thomas A. (1980), A Diplomatic History of the American People 10th ed., Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-214726-2

- Barck, Jr., Oscar Theodore (1974), Since 1900, MacMilliam Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 0-02-305930-3

- Beale, Howard K. (1957), Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power, Johns Hopkins Press

- Berman, Karl (1986), Under the Big Stick: Nicaragua and the United States Since 1848, South End Press

- Bishop, Joseph Bucklin (1913), Uncle Sam's Panama Canal and World History, Accompanying the Panama Canal Flat-globe: Its Achievement an Honor to the United States and a Blessing to the World, Pub. by J. Wanamaker expressly for the World Syndicate Company

- Conniff, Michael L. (2001), Panama and the United States: The Forced Alliance, University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-2348-9

- Davis, Kenneth C. (1990), Don't Know Much About History, Avon Books, ISBN 0-380-71252-0

- Gould, Lewis L. (1991), The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-0565-1

- Hershey, A.S. (1903), The Venezuelan Affair in the Light of International Law, University of Michigan Press

- LaFeber, Walter (1993), A Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations: The American Search for Opportunity. 1865 - 1913, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38185-1

- Perkins, Dexter (1937), The Monroe Doctrine, 1867-1907, Baltimore Press

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1913), Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, The Macmillan Press Company

- Zinn, Howard (1999), A People's History of the United States, Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-06-083865-5

- Congress and Woodrow Wilson’s, Military Forays Into Mexico. An Introductory Essay By Don Wolfensberger - Congress Project Seminar On Congress and U.S. Military Interventions Abroad - Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Monday, May 17, 2004

- Foreign Affairs,. (2015). The Great Depression. Retrieved 29 October 2015, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/1932-07-01/great-depression

- Dueñas Van Severen, J. Ricardo (2006). La invasión filibustera de Nicaragua y la Guerra Nacional. Secretaría General del Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana SG-SICA.

- Rosengarten, Jr., Frederic (1976). Freebooters must die!. Haverford House, Publishers. ISBN 0-910702-01-2.

- Scroggs, William O. (1974). Filibusteros y financieros, la historia de William Walker y sus asociados. Colección Cultural Banco de América.

- La guerra en Nicaragua, 1860, del propio William Walker, traducida al español en 1883 por el italo-nicaragüense Fabio Carnevalini y reeditada en 1974 y 1993.

- Obras históricas completas, [[1865]], de Jerónimo Pérez, reeditada en 1928 por Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya y más adelante en [[1974]] y [[1993]].

- Con Walker en Nicaragua, ([[1909]]), de James Carson Jamison, quien fue capitán de su ejército y estuvo en sus expediciones. * La Guerra Nacional. Centenario, 1956, de Ildefonso Palma Martínez, reeditada en 2006 en el Sesquicentenario de la Batalla de San Jacinto.

- El predestinado de ojos azules, [[1999]], de Alejandro Bolaños Geyer

- Investigación más completa sobre William Walker en el mundo

- Harrison, Brady. William Walker and the Imperial Self in American Literature. University of Georgia Press, August 2, 2004. ISBN 0-8203-2544-9. ISBN 978-0-8203-2544-6.

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ "One Drop of Blood" by Lawrence Wright, The New Yorker, July 24, 1994

- ↑ Dworkin, Shari L. The Society Pages. "Race, Sexuality, and the 'One Drop Rule': More Thoughts about Interracial Couples and Marriage"

- ↑ "Mixed Race America – Who Is Black? One Nation's Definition". www.pbs.org. Frontline. "Not only does the one-drop rule apply to no other group than American blacks, but apparently the rule is unique in that it is found only in the United States and not in any other nation in the world."

- ↑ Khanna, Nikki (2010). "If you're half black, you're just black: Reflected Appraisals and the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule". The Sociological Quarterly. 51 (5): 96–121. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.619.9359. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01162.x.

- ↑ Hickman, Christine B. “The Devil and the One Drop Rule: Racial Categories, African Americans, and the U.S. Census.” Michigan Law Review, vol. 95, no. 5, 1997, pp. 1161–1265. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1290008

- ↑ Schor, Paul. “From ‘Mulatto’ to the ‘One Drop Rule’ (1870–1900).” Oxford Scholarship Online, 2017, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199917853.003.0011

- ↑ Gómez, Laura E. “Opposite One-Drop Rules: Mexican Americans, African Americans, and the Need to Reconceive Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century Race Relations.” How the United States Racializes Latinos: White Hegemony and Its Consequences, by Cobas José A. et al., Routledge, 2016, p. 14

- ↑ Brown, Kevin D. “The Rise and Fall of the One-Drop Rule: How the Importance of Color Came to Eclipse Race.” Color Matters: Skin Tone Bias and the Myth of a Post-Racial America, by Kimberly Jade Norwood, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2014, p. 51

- ↑ Jordan, W. D. (2014). Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States. Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies, 1(1). Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91g761b3

- ↑ Scott Leon, Princeton University, 2011. Hypodescent: A History of the Crystallization of the One-drop Rule in the United States, 1880-1940 url: https://search.proquest.com/openview/333a0ac8590d2b71b0475f3b765d2366/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- ↑ Winthrop, Jordan D. “Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States.” Color Matters: Skin Tone Bias and the Myth of a Post-Racial America, by Kimberly Jade Norwood, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2014

- ↑ Esthus, Raymond A. "The Changing Concept of the Open Door, 1899-1910," Mississippi Valley Historical Review Vol. 46, No. 3 (Dec., 1959), pp. 435–454 JSTOR

- ↑ Hu, Shizhang (1995). Stanley K. Hornbeck and the Open Door Policy, 1919-1937. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29394-5.

- ↑ Lawrence, Mark Atwood/ “Open Door Policy”, Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, (online).

- ↑ McKee, Delber (1977). Chinese Exclusion Versus the Open Door Policy, 1900-1906: Clashes over China Policy in the Roosevelt Era. Wayne State Univ Press. ISBN 0-8143-1565-8.

- ↑ Moore, Lawrence. Defining and Defending the Open Door Policy: Theodore Roosevelt and China, 1901–1909 (2017)

- ↑ Otte, Thomas G. (2007). The China question: great power rivalry and British isolation, 1894-1905. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921109-8.

- ↑ Sugita, Yoneyuki, "The Rise of an American Principle in China: A Reinterpretation of the First Open Door Notes toward China" in Richard J. Jensen, Jon Thares Davidann, and Yoneyuki Sugita, eds. Trans-Pacific relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the twentieth century (Greenwood, 2003) pp 3–20 online

- ↑ Vevier, Charles. "The Open Door: An Idea in Action, 1906-1913" Pacific Historical Review 24#1 (1955), pp. 49-62 online.

- ↑ Martin, Gary. "Speak Softly And Carry a Big Stick"

- ↑ Martin, Gary. "Speak softly and carry a big stick"

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. (2019, September 16). Big Stick ideology. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 08:24, September 19, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Stick_ideology

- ↑ National Geographic Society. “Big Stick Diplomacy.” National Geographic Society, 18 July 2014, www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/sep2/big-stick-diplomacy/.

- ↑ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Big Stick Policy.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/event/Big-Stick-policy.

- ↑ Theodore Roosevelt, Roosevelt Corollary. (en) « Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power. »

- ↑ Statement to British envoy William Tyrrell (November 1913), explaining his policy on Mexico

- ↑ Constitution de 1918, présentée le 12 juin 1918. Constitution préparée par les États-Unis qui occupent le pays depuis 1915. Adoptée par plébiscite.

- ↑ Brainy Quote, FDR

- ↑ Blood on the Border: Prologue