A multipolar world: 1989 - 2011

Based on a lesson by Ludovic Tournès[1][2][3]

Perspectives on the studies, issues and problems of international history ● Europe at the centre of the world: from the end of the 19th century to 1918 ● The era of the superpowers: 1918 - 1989 ● A multipolar world: 1989 - 2011 ● The International System in Historical Context: Perspectives and Interpretations ● The beginnings of the contemporary international system: 1870 - 1939 ● World War II and the remaking of the world order: 1939 - 1947 ● The international system in the test of bipolarisation: 1947 - 1989

The term "multipolar world" refers to an international system in which power is shared between several states or groups of states. It is an alternative to a unipolar world, where a single state (such as the United States after the Cold War) or a group of states (such as the West during the Cold War) holds the majority of global power. The transition from a unipolar to a multipolar world has created new power dynamics and tensions on the world stage. Emerging powers and power blocs have begun to claim greater influence in world affairs, often through economic and political channels.

The end of the Cold War was marked by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. These events put an end to almost half a century of global bipolarity, with the United States and the Soviet Union as the dominant superpowers. With the end of the Cold War, the United States became the world's only superpower, leading to a period of unipolar domination. This period of unipolar dominance was, however, short-lived. During the 1990s and 2000s, several other countries began to increase their influence on the world stage. China, in particular, experienced rapid economic growth that strengthened its power and influence. Similarly, the European Union has consolidated and expanded, becoming a major player in world affairs. Other countries, such as India and Brazil, have also begun to play a more important role.

The transition to a multipolar world has not been without its challenges. Many regional conflicts have broken out, often due to rivalries over power or resources. For example, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were partly the result of the struggle for control of oil and gas resources. Similarly, tensions between the United States and Russia have continued to manifest themselves, notably due to disagreements over issues such as NATO expansion and the Crimea question. The transition to a multipolar world remains an ongoing process, and the future of this new international system is uncertain. Tensions between the major powers, regional conflicts, and global challenges such as climate change and nuclear proliferation will continue to shape the global balance of power in the years to come.

The collapse of the Soviet bloc[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The collapse of the Soviet bloc was one of the most significant events of the late twentieth century. Not only did it put an end to almost 50 years of Cold War, but it also led to profound and often tumultuous changes in the countries of Eastern Europe and the rest of the world. Poland is often cited as the place where the first cracks in the Soviet bloc began to appear. The Solidarity movement, led by Lech Wałęsa, organised a series of strikes in 1980 to protest against working conditions and the Communist regime. These strikes led to negotiations with the government and the recognition of Solidarity as the first independent trade union in a communist country. In Hungary, the government began to liberalise its economy and introduce political reforms in the 1980s. In 1989, Hungary began to dismantle its border with Austria, opening a breach in the Iron Curtain separating East and West. Czechoslovakia experienced a peaceful 'Velvet Revolution' in 1989, when massive demonstrations led to the resignation of the Communist government. Romania was the only country to experience a violent revolution. In December 1989, demonstrations against Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime were violently repressed, but eventually led to Ceaușescu's arrest and execution. And finally, in November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. This symbolic event marked the end of the Cold War and paved the way for German reunification the following year. All these events marked the beginning of the transition of these countries to market economies and democratic political systems. However, this transition has not been easy and these countries continue to face challenges linked to their communist past.

Undeniably, the collapse of the Soviet bloc represents a historic turning point that has redefined the global balance of power. First and foremost was the rise of the United States as the world's only superpower. This new stature has given it a decisive influence on the international stage. Its dominance was particularly palpable during the 1990s, as witnessed by its military interventions in Bosnia, Kosovo and Iraq. At the same time, Russia, once a global giant, has seen a marked decline in its international influence. The disintegration of the Soviet Union led to a drastic fall in its power, militarily, economically and politically. Many of the republics that had previously been part of the Soviet Union became independent. However, Russia, particularly under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, is working hard to regain its former influence. The collapse of the Soviet bloc has also given new impetus to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Several Eastern European countries, formerly under the Soviet shadow, joined NATO, consolidating the alliance's role in the European security landscape. The collapse of the Cold War also gave rise to significant changes in the global economy. The decline of communism encouraged the adoption of the market economy system in many countries, fuelling globalisation and economic interdependence. Despite the rise of the United States as the sole superpower, the collapse of the Soviet bloc opened the way for other nations to increase their influence. China, for example, took advantage of this opportunity to boost its economic growth and expand its role on the world stage.

The demise of the bipolar system has left a power vacuum in some parts of the world, giving rise to a series of conflicts and tensions. The former buffer states between East and West have had to find their own way, sometimes triggering internal conflicts or becoming points of friction between the new emerging powers. In some cases, the end of the Cold War opened the way for ethnic or political tensions that had previously been suppressed by the bipolar power structure. The conflicts in the Balkans in the 1990s are a striking example, where ethnic tensions degenerated into large-scale violence after the fall of communism. In addition, in some regions such as the Middle East, the power vacuum has exacerbated regional rivalries and led to increased conflict and instability. In the absence of a clear balance of power, several countries have sought to extend their influence, often by military means. Overall, the transition to a multipolar world has brought new complexities and challenges in terms of international relations, as nations navigate this new power dynamic.

The Communist system at the end of its tether[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The rise of the Soviet Union[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Before the revolution of 1917, Russia, which was to become the heart of the Soviet Union, was widely perceived as a developing country, with an economy dominated by agriculture and an overall level of development significantly lower than that of Western European countries. In 1917, the Russian economy, which was on the verge of becoming the Soviet Union, lagged far behind its Western European counterparts. A large proportion of the population lived in rudimentary conditions, with a low standard of living, inadequate wages and low literacy rates. Moreover, Russia's economy was heavily dependent on agriculture, with little industrialisation and underdeveloped infrastructure.

The First World War put enormous pressure on this fragile economic balance, resulting in devastating economic and human losses that exacerbated the country's precarious state. The revolution of 1917, however, paved the way for radical change. The Bolshevik leaders who took power after the revolution initiated a bold programme of economic and industrial development. Despite very high human and social costs, including famine, political purges and general political repression, these policies led to rapid economic growth. In just a few decades, the Soviet Union was transformed from a largely agrarian economy into an industrial superpower with a massive military capability. Although the Soviet Union became a global superpower, it continued to experience considerable internal economic and social problems. Economic inefficiency, corruption, mismanagement and deprivation persisted throughout the Soviet Union's existence, contributing to its eventual collapse in 1991.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union pursued a major armaments policy to compete with the United States, which came at a significant economic cost. The Soviet government invested heavily in the military industry, using a large proportion of its resources to finance these efforts. This resulted in sacrifices for the Soviet population, including a lower standard of living and a slowdown in general economic development. Despite these challenges, it is important to note that the Soviet Union was not considered a Third World country when it became a superpower. After the Second World War, the Soviet Union emerged as one of the world's two superpowers, rivalling the United States. Although its economy was highly centralised, it was sufficiently developed to rival the United States in areas such as space research, military technology and industrial production. This rivalry and arms race came at a significant economic cost to the Soviet Union, contributing to internal economic problems and ultimately to the collapse of the Union in 1991.

The collapse of the Soviet Union[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Structural factors leading to collapse[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The collapse of the Soviet Union was the product of a number of interconnected factors that grew in magnitude over the decades.

Internal tensions were a key element in this process. Endemic corruption and economic inefficiency led to growing discontent among the Soviet population. The centralised, planned structure of the Soviet economy, while allowing initial progress in industrialisation and development, eventually stifled innovation and economic efficiency. Economic problems were exacerbated by the arms race with the United States, which drained much of the Soviet Union's resources. Political repression and a lack of civil liberties also fuelled internal resistance. The oppression of dissent and the lack of freedom of expression created a climate of fear and resentment. Events such as the Budapest Uprising in 1956, the Prague Spring in 1968 and the Solidarność movement in Poland in the 1980s clearly demonstrated a growing discontent among the citizens of the Soviet Union's satellite countries. In addition to these internal pressures, the Soviet Union was also subject to external pressures. Military, economic and ideological competition with the United States placed constant strain on the Soviet regime. Ultimately, these factors, combined with Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), led to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The Soviet Union came under significant external pressure during the Cold War, particularly from the United States and its allies in Western Europe. This pressure played an important role in the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. The confrontation strategy adopted by the United States and its allies included a number of approaches. The United States, for example, invested massively in its military arsenal, forcing the Soviet Union to do the same in order to maintain strategic parity. This put enormous economic pressure on the Soviet Union, which struggled to keep pace while trying to meet the economic and social needs of its population. In addition, the US and its allies actively supported dissident movements and human rights groups in Soviet bloc countries. They used a variety of methods, including broadcasting, financial support, and diplomacy, to encourage these movements. This put political pressure on the Soviet Union and helped to create internal discontent. The combined effect of these internal and external pressures eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, marking the end of the Cold War and the beginning of a new era in international relations.

Factors challenging the model[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The publication of "The Gulag Archipelago" by Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 1974 marked a significant turning point in the way the Soviet regime was perceived abroad. This detailed and personal account of the Soviet forced labour camp system brought to light the reality of political repression and human rights abuses under the Communist regime. The revelation of these atrocities helped to shake the image of Soviet communism and intensify criticism of the regime. The book was widely read and discussed in the West, contributing to a shift in public opinion and an awareness of the reality of life in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, these revelations were not new to many Soviet citizens and dissidents. Many were already aware of the brutality of the regime and had experienced or witnessed the direct consequences of its repression. However, the impact of 'The Gulag Archipelago' was in the way it succeeded in bringing these realities to the attention of a wider international audience, thereby fuelling increased external pressure on the Soviet regime.

Dissidence movements in Eastern Bloc countries, notably the Solidarność movement in Poland, played a crucial role in challenging the Soviet regime. This independent trade union, led by Lech Walesa, succeeded in mobilising millions of Polish workers to protest against the Communist regime in Poland, marking a decisive turning point in the history of Eastern Europe. Alongside these internal protest movements, the revelation of atrocities committed by the Soviet regime helped to shake the "Soviet myth". The reality of human rights violations, political repression and the concentration camp system in the Soviet Union was gradually revealed to the world, undermining the legitimacy of and support for the Soviet regime. These combined factors - internal dissent, external pressure and awareness of the regime's abuses - led to a gradual weakening of the Soviet regime, which finally culminated in its collapse in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This marked the end of almost half a century of Soviet domination in Eastern Europe and paved the way for a period of major political, economic and social transformation in the region.

The arrival in power of Leonid Brezhnev in 1964 marked a hardening of the Soviet regime. Brezhnev imposed a more assertive foreign policy, seeking to broaden and strengthen Soviet influence on the international stage. This led to increased support for communist and national liberation movements around the world, particularly in Africa, Asia and Latin America. At the same time, Brezhnev implemented a domestic policy of increased repression. It was under his reign that the "Brezhnev Doctrine" was formulated, which stipulated that the Soviet Union had the right to intervene in the internal affairs of any Communist country in order to protect the socialist system. This doctrine was used to justify the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, ending the period of liberalisation known as the Prague Spring. In addition, internal dissent was severely repressed under Brezhnev. Dissidents who criticised the regime or demanded greater political and civil liberties were monitored, harassed, arrested and often sent to prison or into exile. This policy of repression contributed to the isolation of the Soviet Union and fuelled resentment and opposition within the country. This period of "glaciation" lasted until the early 1980s, when the new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev undertook a series of political and economic reforms known as "glasnost" (openness) and "perestroika" (restructuring), which eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the decade.

Rivalry between great powers intensifies and subsides[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The era of Leonid Brezhnev marked an escalation in competition between the Soviet Union and the United States, ushering in an era of high tension commonly referred to as the 'Cold War'. These two superpowers considerably increased their stockpiles of nuclear weapons and engaged in a global competition to extend their influence, supporting various political movements and becoming directly involved in several regional conflicts. This period was characterised by the arms race, indirect military interventions and the use of diplomacy and propaganda to win allies and influence the course of world events. The ideological rivalry between communism and capitalism was another key aspect of this period, with each side seeking to promote its own system as the model to follow.

However, this climate of intense confrontation and 'glaciation' did not persist indefinitely. Mikhail Gorbachev's arrival in power in 1985 ushered in an era of change and reform for the Soviet Union. With his policies of "glasnost" (openness) and "perestroika" (restructuring), Gorbachev sought to modernise the Soviet economy and relax the rigidity of the political system. Gorbachev also sought to calm East-West relations, encouraging détente with the United States and Western countries. These initiatives led to the end of the Cold War and played a key role in the events that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Thus, a period that began with intensifying confrontation between the superpowers culminated in a process of détente and transformation that redefined the global political landscape.

The influence of economic factors[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

As the 1980s progressed, the Soviet economic system gradually demonstrated its inability to meet the challenges of the times. Despite high ambitions for modernisation and industrialisation, the Soviet Union failed to catch up with the standard of living in Western countries. The Soviet economy was based on centralised planning, with absolute state control over production. The means of production were owned by the state, which meant that all enterprises were run by the state rather than by private owners. This arrangement led to heavy bureaucracy, inefficient allocation of resources and economic stagnation. The lack of competition and the absence of incentives to improve efficiency or innovate also played a part in the system's failure. The Soviet Union also experienced widespread corruption, exacerbated by a rationing system and a burgeoning black economy. In addition, the considerable efforts devoted to the arms race with the West drained a substantial part of the Soviet Union's resources, exacerbating the economic crisis. In the end, the Soviet economy failed to adapt and respond to the changing needs of its population, contributing to the instability that eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

During the 1970s and 1980s, a series of external factors exacerbated the Soviet Union's economic problems. Among these factors, the fall in oil prices had a particularly devastating impact. Oil was a major source of revenue for the Soviet Union and when prices fell, the Soviet economy suffered. At the same time, military spending soared as the Soviet Union engaged in an arms race with the United States. This exorbitant spending drained the country's financial resources, further reducing investment in other sectors of the economy and hampering economic growth. These external factors have added further pressure to an already strained economy. They exacerbated the structural weaknesses of the Soviet economic system, accelerating its decline and ultimately contributing to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The convergence of these negative economic factors created a major crisis for the Soviet Union. The country's debt rapidly accumulated, the cost of living rose due to rampant inflation, and shortages of basic consumer goods became commonplace. These problems undermined public confidence in the Soviet economic system. Faced with this increasingly difficult reality, many citizens began to doubt the Soviet government's ability to ensure their well-being. The widening gap between the promise of communism and the reality of everyday life fuelled growing political protest. Calls for economic reform grew, increasing pressure on the government to change its approach. This erosion of confidence and rise in dissatisfaction ultimately played a key role in the collapse of the Soviet Union. Not only did these developments weaken the legitimacy of the Soviet system, they also fuelled the movements of protest and dissent that precipitated the regime's downfall.

The economic crisis undoubtedly played a major role in the final collapse of the Soviet Union. It undermined the credibility of the regime, eroding the trust that citizens had in their government. The shortage of basic goods, the rising cost of living and the widespread inefficiency of the economy led to widespread discontent among the population, undermining the legitimacy of the government. This economic crisis, coupled with an increasingly tense political context, contributed significantly to the collapse of the Soviet regime.

The war in Afghanistan[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The war in Afghanistan, launched in 1979, was a real burden on the Soviet economy and considerably shook the people's confidence in their government. The war, as costly in resources as in human lives, was increasingly unpopular. The Soviet leadership faced fierce criticism for its bellicose foreign policy and its military intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. These factors gradually fuelled a loss of confidence on the part of the population, giving rise to growing political opposition. These and other factors eventually led to the collapse of the Soviet regime.

The war in Afghanistan was one of the major triggers for the widespread political insurrection in the Soviet Union that eventually led to the fall of the regime. This conflict, fought on guerrilla terrain where Soviet forces were bogged down for years, was particularly costly in terms of human lives and material resources. It provoked widespread unpopularity among Soviet citizens, helping to fuel widespread discontent. The Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan was widely criticised, both inside and outside the country, as a form of imperialism or neo-colonialism. This perception contributed to the further isolation of the Soviet Union on the international stage and strengthened internal opposition. Inside the Soviet Union, the war contributed to growing disillusionment with the regime and its ideological rhetoric. The loss of life, the economic cost of the war and its growing unpopularity exacerbated existing discontent with government corruption, political repression and persistent economic problems. Outside the Soviet Union, the war was condemned by much of the international community. Not only did this isolate the Soviet Union, it also created an opportunity for the United States and its allies to actively support the Afghan Mujahedin, further increasing the pressure on the Soviet Union.

The fall of the Berlin Wall: Causes and consequences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The fall of the Berlin Wall[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The fall of the Berlin Wall was the product of a complex combination of political, economic and social factors, both internal and external to the GDR and the Soviet Union.

Internally, the GDR faced a series of serious problems. The country's economy was in bad shape, with stagnant economic growth, high foreign debt and a lack of consumer goods. In addition, there was widespread dissatisfaction among the population with the authoritarian communist regime. GDR citizens were frustrated by the lack of freedom and political repression, as well as by economic inequality and lack of opportunity.

Externally, the Soviet Union underwent a series of major political changes under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev. His policy of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) led to a degree of political and economic liberalisation, not only in the Soviet Union but also in other Eastern Bloc countries. In addition, Gorbachev adopted a policy of non-intervention in the internal affairs of the Soviet Union's satellite countries, which allowed protest movements to develop in these countries without fear of Soviet military intervention.

All these factors contributed to creating an environment conducive to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Popular pressure for change in the GDR, combined with political openness in the Soviet Union, led to a tipping point where the GDR government was no longer able to maintain control. On 9 November 1989, the GDR authorities announced that all GDR citizens could visit West Germany and West Berlin - leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The end of Communist domination in Europe[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The fall of the Berlin Wall also signalled the end of the ideological division of the world into East-West blocs that had prevailed for most of the twentieth century. It marked the beginning of a new era in international relations, characterised by the hegemony of the United States and the apparent triumph of democratic and capitalist ideals. That said, the road to democracy and capitalism was not an easy one for all the countries that emerged from the collapse of the Soviet bloc. The economic transition has been particularly difficult, with a significant rise in unemployment, inflation and poverty in many countries. In addition, political reform has often been undermined by corruption, poor governance and authoritarianism. The break-up of the Soviet Union and the end of Communist domination in Eastern Europe also had major geopolitical consequences. They led to the emergence of new independent countries, each with its own political and economic challenges. They also fuelled regional conflicts and ethnic tensions, as we saw in the Balkans in the 1990s.

The opening of the border between Hungary and Austria in 1989 was a landmark event in the history of the fall of the Eastern bloc and the Iron Curtain. Not only did it provide an escape route for East Germans seeking to leave the Communist bloc, it also highlighted the erosion of the Communist regime's authority and control in Eastern Europe. Hungary's decision to dismantle its border fences was one of many signs that the power of Communist regimes in the region was crumbling. It also showed that the policies of glasnost (transparency) and perestroika (restructuring) introduced by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had repercussions far beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. What's more, this event also demonstrated the important role that individual countries like Hungary played in the fall of the Eastern bloc. Although the end of the Cold War is often associated with larger players and events, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Hungary's decision to open its borders was a crucial step that paved the way for these historic events.

In Poland, the "round table" agreement between the Communist government and the independent trade union Solidarność led to semi-free elections on 4 June 1989. In these elections, Solidarność won a landslide victory. Although the Communist Party reserved a number of seats in parliament for itself, the scale of Solidarność's victory made it clear that the Communist regime no longer had the support of the Polish people. This event marked the beginning of the end of communism in Poland. Similarly, in Hungary, the victory of the Hungarian Democratic Forum in the 1990 parliamentary elections marked the end of communist rule in the country. This victory was preceded by a process of liberalisation and reform that had begun in the 1980s. Overall, these elections were clear signs of the end of communist hegemony in Eastern Europe and the emergence of new democracies in the region.

The fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime in Romania was one of the most dramatic moments in the end of communism in Eastern Europe. While most other communist regimes in the region were toppled by relatively peaceful protest movements or negotiated political transitions, in Romania the end of communism was marked by significant violence. Protests began in Timișoara in December 1989 in response to the government's attempt to deport a Hungarian-born Protestant pastor, László Tőkés, who had criticised the regime's policies. Protests quickly spread across the country, despite violent repression by the security forces. Eventually, the army turned against Ceaușescu, who was captured as he tried to flee Bucharest by helicopter. After a summary trial, Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena were executed on Christmas Day 1989. The end of the Ceaușescu dictatorship marked the beginning of a difficult period of transition in Romania, which faced many challenges, including establishing democratic institutions, reforming the economy and dealing with the consequences of the repression and widespread corruption of the Ceaușescu regime.

German reunification[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 was one of the most symbolic moments in the history of the 20th century. Not only did it mark the end of the division of Germany, it also symbolised the end of the Cold War and the division of Europe into East and West blocs. The fall of the Berlin Wall was preceded by growing protests and pressure for reform in East Germany (GDR). In response to this pressure, the GDR government announced a liberalisation of foreign travel restrictions for East German citizens. However, due to confusion in the communication of this policy, citizens believed that the borders were completely open and rushed towards the wall, eventually forcing the guards to open the checkpoints. The fall of the Berlin Wall had far-reaching repercussions, paving the way for German reunification less than a year later, in October 1990, and accelerating political change in other Eastern European countries. It is an event that continues to be celebrated as a symbol of freedom and unification.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, pressure for the reunification of East and West Germany increased significantly. In early 1990, free elections were held in East Germany for the first time in decades, and the pro-reunification parties won a landslide victory. During the summer and autumn of 1990, the two Germanies negotiated a reunification treaty, and the way was paved for East Germany to join the Federal Republic of Germany. On 3 October 1990, reunification was officially proclaimed, and East Germany ceased to exist. German reunification was a major event in post-Second World War history, marking the end of almost half a century of division in Germany and symbolising the end of the Cold War. It also posed many challenges, as the unified Germany had to integrate two very different economic and social systems.

The end of the Warsaw Pact[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Warsaw Pact, officially known as the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defence organisation of the communist countries of Eastern Europe during the Cold War, under the leadership of the Soviet Union. It was created in 1955 in response to the accession of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) to NATO. The dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991 came after several years of political and social change in the countries of Eastern Europe, including the collapse of the communist regimes in these countries and the end of the Cold War. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union later that year, the Warsaw Pact lost its raison d'être and was officially dissolved. The end of the Warsaw Pact marked the end of the military division of Europe that had existed during the Cold War, and paved the way for NATO's expansion into Eastern Europe in the following years.

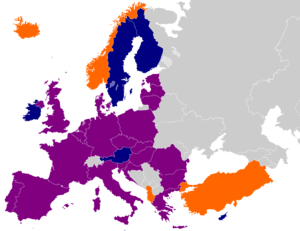

Following the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991, many of its former members began to turn towards the West. During the 1990s and 2000s, several former members of the Warsaw Pact joined NATO and the European Union, marking a significant transition towards democratic systems and market economies. These transitions were not without difficulties. Challenges included transforming planned economies into market economies, reforming political systems to become pluralist democracies, and managing ethnic and nationalist tensions that had been suppressed during the communist period. Nevertheless, the end of the Warsaw Pact and the westward movement of its former members were key elements in the geopolitical reorganisation of Europe after the end of the Cold War.

Creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 marked the end of the Cold War and profoundly transformed world geopolitics. The Soviet Union was replaced by 15 independent states, of which Russia is the largest and most influential.

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) was created to facilitate cooperation between these newly independent states and to manage some of the problems inherited from the Soviet Union, such as economic coordination and nuclear weapons management. However, the CIS never managed to exercise any significant authority and its relevance diminished over time as many of its members turned their attention to Europe and the West.

Member states retained their sovereignty and pursued independent foreign policies. Several of them, particularly the Baltic States and those of Eastern Europe, sought to move closer to the West and to integrate into European and Atlantic structures such as the European Union and NATO.

The emergence of a new world order[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The end of the Cold War and the disintegration of the Soviet Union have radically transformed the global geopolitical chessboard. The bipolar pattern of the Cold War, marked by intense opposition between two predominant superpowers, has metamorphosed into a multipolar world, characterised by increased complexity.

In this new post-Cold War world order, although the United States has retained its status as a military and economic superpower, its hegemony is no longer as unchallenged as it once was. Other nations, such as China, India and the European Union, have emerged as major forces on the international stage. At the same time, globalisation has enabled a host of other countries and regions to increase their influence and importance. Multilateral bodies, notably the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation, have taken on a more prominent role in regulating global affairs. In addition, transnational issues such as climate change, international terrorism, pandemics and cyberspace have become increasingly relevant, destabilising the traditional nation-state structure of world order.

The break-up of the Soviet Union and the Communist bloc led to a complete overhaul of the global geopolitical order established at the end of the Second World War. The bipolar division of the world between the United States and the Soviet Union gave way to multipolarity, with new players taking their place on the international stage. The end of the Cold War also brought major upheavals in international relations, notably the reunification of Germany, the end of the arms race, the demilitarisation of Eastern Europe, and the transition to democracy in many Central and Eastern European countries. These events had a significant impact on politics and international relations in the decades that followed.

Russia's transition: Decline and Renaissance[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The collapse of the USSR plunged Russia into a period of intense economic and political crisis. The country went through a period of turmoil, punctuated by demanding economic reforms, unbridled inflation and a decline in living standards. In addition, the transition from communist to democratic rule was fraught with difficulties, internal conflicts and struggles between different political groups. Russia has also faced major geopolitical challenges, with the loss of its former socialist republics, the questioning of its superpower status and the rise of new regional players.

Faced with this situation, Russia adopted a policy of refocusing, illustrated by its intervention in Chechnya in 1994, which triggered a long sequence of war and tension in the region. Despite the hardships it faced, Russia managed to stabilise its economy and strengthen its political system throughout the 2000s, notably under the presidency of Vladimir Putin. Today, the country is seen as a rising force on the international stage, with a booming economy and growing diplomatic influence.

The economic transition and its social consequences[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Russia into a phase of tumultuous economic transition, as it attempted to move from a planned economy to a market economy. This period was marked by a drastic contraction in industrial production, a direct consequence of liberalisation and radical structural reforms. Many industries, which had relied heavily on state subsidies under the Soviet regime, were unable to adapt to the new market realities and were forced to close down. This led to a significant rise in the unemployment rate, plunging many families into precariousness.

During the 1990s, Russia went through a period of difficult economic change, underpinned by economic and structural reforms designed to move the country from a planned economy to a market economy. International players such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank played a major role in this transition, exerting substantial pressure to implement these changes. These economic reforms led to the liberalisation of prices and trade, the mass privatisation of state-owned enterprises, the reduction of subsidies and the adoption of a more rigid monetary policy to combat inflation. These radical changes, although necessary for the country's economic development, have often been difficult for large sections of the Russian population.

These reforms have had serious socio-economic consequences, notably a rise in poverty, an increase in the unemployment rate and a deterioration in living conditions for a large part of the Russian population. What's more, this economic transformation has been marred by corruption and the questionable privatisation of many state-owned companies. These practices have benefited a small economic and political elite, but have left a large part of the Russian population destitute and unemployed. Economic change has led to a drastic fall in industrial production and an alarming rise in unemployment, inflation and poverty. The cost of basic necessities soared, while wages stagnated, leading to a deterioration in household purchasing power.

This period was marked by great political and social instability, with demonstrations, strikes and violence, as well as an increase in crime and corruption. At the same time, the government had to contend with galloping inflation. Price liberalisation, implemented as part of economic reforms, has led to a dramatic rise in the cost of basic necessities. The contrast with the Soviet period, when prices were controlled and subsidised by the state, was striking. This had a direct and painful impact on the purchasing power of households, many of whom saw their standard of living deteriorate dramatically. Poverty increased alarmingly during this period. As the country struggled to adapt to its new economic model, many Russians were left behind, unable to meet the rising cost of living or find employment in a rapidly changing economy. Inequalities widened, with the economic and political elite benefiting from the privatisation of the economy, while the majority of the population saw their living conditions plummet.

The transition to a market economy has made Russia more exposed to global economic fluctuations and crises. Prior to this transition, under the Soviet regime, the Russian economy was largely isolated from the global economy, which partly protected it from external economic crises. However, with Russia's gradual integration into the global economy, this protection has disappeared. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 was one of the first major tests of the resilience of the post-Soviet Russian economy. The economic shock in Asia quickly affected Russia, mainly because of the fall in the price of raw materials, which made up a large proportion of Russian exports. This crisis exacerbated existing economic problems in Russia, leading to a financial crisis in 1998 which saw the rouble depreciate massively and the Russian government declare a moratorium on public debt. The global financial crisis of 2008 also had a significant impact on the Russian economy. The fall in commodity prices, particularly oil, led to a severe economic contraction. In addition, Russia's integration into the global financial system meant that the credit crisis that hit Western economies also affected Russia, with a drop in foreign investment and capital flight. These crises have revealed the vulnerability of the Russian economy to external shocks and underlined the need for the country to diversify its economy, which remains heavily dependent on exports of raw materials, particularly oil and gas.

The war in Chechnya[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The war in Chechnya has been one of the greatest security challenges facing post-Soviet Russia. The conflict began in 1994 when Chechnya, an autonomous republic in the North Caucasus, declared independence from Russia. In response, the Russian government launched a military intervention to re-establish its authority.

The First Chechen War, which lasted from 1994 to 1996, was a major military and political test for post-Soviet Russia. Despite the Russian forces' huge advantage in terms of numbers and technology, the Chechen resistance proved extremely tenacious and capable of waging an effective guerrilla war against the Russian troops. There are several reasons for this resistance. Firstly, Chechnya's mountainous terrain has provided Chechen forces with natural protection and plenty of places to hide and launch attacks. Secondly, many Chechens were deeply committed to the cause of independence and were prepared to fight to the death to defend their homeland. Finally, the Chechen forces were led by experienced warlords who were well versed in guerrilla tactics. The inability of Russian forces to take rapid control of Chechnya was also exacerbated by structural and organisational problems within the Russian army. Many Russian soldiers were poorly trained, ill-equipped and ill-prepared for combat conditions in Chechnya. In addition, coordination between the different branches of the Russian security forces was often poor, making the conduct of military operations even more difficult. The first Chechen war had an enormous human cost, with thousands of dead and wounded on both sides, and led to major population displacements. It was also marked by serious human rights violations, including extrajudicial executions, torture and enforced disappearances.

The second Chechen war, which began in 1999 and officially ended in 2009, was a period of intense conflict and widespread violence. It began following terrorist attacks in Russia and the invasion of Dagestan by Chechen militants. This war was characterised by an increased use of force by the Russian government and an intensification of violence. This second war was even more devastating than the first, causing the deaths of thousands of people and the displacement of hundreds of thousands more. Chechnya's towns and villages have been badly damaged and the region's infrastructure has been largely destroyed. Massive human rights violations have been committed by all parties to the conflict, including extrajudicial executions, torture, abductions and attacks on civilians. These abuses have been widely documented by human rights organisations, but few have been seriously investigated or prosecuted. The Russian military intervention in Chechnya has also had significant political repercussions. It contributed to the election of Vladimir Putin as President of Russia in 2000, and marked the beginning of a period of authoritarian rule and state-building in Russia.

The war in Chechnya played a significant role in Vladimir Putin's political rise. When Putin was appointed Prime Minister by President Boris Yeltsin in 1999, Russia was facing a series of internal and external challenges. Among these, the situation in Chechnya was one of the most pressing. Putin made resolving the Chechen conflict a priority, promising to restore order and authority to the Russian state. When terrorist attacks hit several Russian cities in 1999, Putin was quick to blame Chechen separatists, and launched a second war against Chechnya. This decision was widely supported by the Russian public, and reinforced Putin's image as a strong and resolute leader. Putin used the war in Chechnya to consolidate his power, promote nationalism and demonstrate his willingness to use force to preserve Russia's territorial integrity. Putin's handling of the war in Chechnya has also had an impact on Russia's relations with the rest of the world. Although the conduct of the war has been criticised for its human rights abuses, the international community has largely accepted Putin's position that the war in Chechnya was a necessary part of the global fight against terrorism. This has allowed Putin to consolidate his control over Chechnya and strengthen his power in Russia, while resisting international pressure for a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

The consequences of the loss of international influence[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to a deep economic crisis in Russia and considerable political instability. These internal challenges limited Russia's ability to exert significant influence on the international stage.

During the Gulf War in 1990-1991, Russia (then still the Soviet Union until December 1991) was going through a period of economic crisis and major internal political change. The imminent collapse of the Soviet Union left the country in a situation of great instability, both internally and on the international stage. As a result, Russia was not in a position to effectively oppose the US-led intervention to liberate Kuwait, which had been invaded by Iraq in August 1990. In fact, the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, ended up supporting the United Nations Security Council resolution authorising the use of force to expel Iraq from Kuwait. This was in contrast to the Cold War period, when the Soviet Union and the United States frequently found themselves in direct opposition on international policy issues. The Gulf War was a striking example of Russia's diminishing global influence during this period of transition.

The fragmentation of Yugoslavia in the 1990s saw Russia play a less influential role than it would have liked, despite deep historical and cultural links with the region, particularly with Serbia. Russia's internal political and economic instability limited its ability to project its influence on the international stage. During the Yugoslav wars, Russia mainly adopted a position of support for Serbia. However, its opposition to NATO's intervention in the Kosovo conflict in 1999 failed to prevent military action. This was a telling example of Russia's diminishing influence on the world stage at the time. In addition, Russia was criticised for its use of the veto as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, particularly when it blocked several resolutions concerning the situation in Bosnia and Kosovo. These actions caused controversy and led to tensions with other members of the Security Council, notably the United States and European countries. However, since the early 2000s, Russia has sought to re-establish its influence on the world stage, thanks in part to a more stable economy and a more assertive foreign strategy under the leadership of Vladimir Putin. This renaissance has been particularly visible in the former Soviet republics, but also on the world stage, where Russia has shown a willingness to defend its interests and challenge the Western-dominated international order.

Although Russia inherited the Soviet Union's seat on the Security Council after the collapse of the USSR, its influence within this body was weakened by its internal economic and political difficulties.

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Despite the profound economic and political difficulties it experienced during the post-Soviet transition, Russia has managed to maintain a dominant influence in its region. Its legacy as the former dominant power of the Soviet Union, combined with its substantial military potential, including its nuclear arsenal, has helped to preserve its status as a major regional power. Russia's influence over the member countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), an organisation comprising several former Soviet republics, is another facet of its regional power. Russia has often used the CIS as an instrument to maintain its influence in the post-Soviet region, through a combination of economic, political and sometimes military levers.

Under the presidency of Vladimir Putin in the early 2000s, Russia embarked on a deliberate campaign to strengthen its presence on the international stage. It worked to rebuild its influence and authority, which had been seriously eroded over the previous decade. Putin adopted a foreign policy aimed at challenging the unipolar world order dominated by the United States after the Cold War. Instead, he championed the idea of a multipolar world order in which several major powers, including Russia, would wield significant influence. This policy has resulted in Russia playing a more active role in world affairs, notably through its status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, its role in regional organisations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and its relations with other emerging countries such as China and India. Russia has also used its abundance of energy resources, particularly oil and gas, as a tool of global power and influence.

In the 2000s and 2010s, Russia took an active part in a number of international conflicts and diplomatic processes. Its intervention in Syria in 2015, for example, changed the course of the civil war in favour of Bashar al-Assad's regime, making Russia a key player in the Syrian conflict. Similarly, Russia played a crucial role in the negotiations on Iran's nuclear programme, which led to the 2015 agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Russia was one of six countries to negotiate this agreement with Iran, alongside the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and China. However, Russia's diplomatic activism has also given rise to controversy. Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, for example, was widely condemned by the international community and led to a series of economic sanctions against Russia by the US and EU. In addition, allegations of Russian interference in elections in other countries, notably the United States in 2016, have also raised tensions with Western countries. These actions have contributed to a deterioration in relations between Russia and the West, marking a new phase of confrontation in international relations. However, they have also strengthened Russia's position as a key global player, capable of significantly influencing world events.

The Russian-Georgian war[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In April 1991, Georgia declared its independence. In response, Russia sought to maintain its hold on the country by supporting separatist movements in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. These two regions, supported by Russia, are demanding independence from Georgia. Russia saw these conflicts as an opportunity to strengthen its regional influence and curb Georgia's attempts to emancipate itself from its former Soviet overlord. In 1992, in a bid to reassert its authority over these territories, Georgia launched an attempt to regain control of these regions. This triggered violent clashes involving both the separatists and the Russian forces stationed in the region. Although a ceasefire agreement was signed in 1993, tensions remained and efforts to find a lasting political solution were still underway.

The Russo-Georgian war of 2008 was a crucial event in the post-Soviet history of the Caucasus region. It followed years of growing tensions between Russia, Georgia and the Russian-backed breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In August 2008, intense fighting broke out in South Ossetia after the Georgian government launched a military operation to regain control of the region. Russia quickly responded with a major military offensive against Georgia. In five days, Russian forces occupied several Georgian towns and bombed military and civilian infrastructure across the country. The Russian intervention provoked international condemnation and marked a major escalation in relations between Russia and the West. The war ended on 12 August 2008, with a ceasefire agreement brokered by French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who held the presidency of the European Union at the time.

After the war, Russia officially recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states, a decision that was widely condemned by the international community and recognised by only a small number of countries. Since then, Russia has maintained a significant military presence in these regions, and the situation remains tense. The war also had a lasting impact on relations between Russia and the West, and was one of the key factors leading to a new era of confrontation between Russia and NATO.

Rising commodity prices[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The boom in commodity prices, particularly oil and gas, has presented Russia with a major economic opportunity. These resources, which make up a considerable proportion of its economy, have propelled significant economic growth. By capitalising on this windfall, Russia has not only been able to strengthen its presence on the international stage, but also to consolidate its position in world affairs. The influx of hydrocarbon revenues has enabled Russia to invest substantially in its military, leading to a remarkable modernisation of its armed forces. This military renovation has strengthened Russia's strategic position on the international stage and enhanced its ability to defend its national interests.

In addition, Russia's economic growth has enabled it to strengthen its relations with rapidly developing emerging nations, particularly China. By positioning itself as an alternative to American domination of the international system, Russia has succeeded in establishing new alliances and increasing its influence in today's multipolar world. This strategy has enabled Russia to rebalance the forces at play and contribute to the construction of a more diversified international dynamic.

The Syrian crisis[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Syrian crisis represented a crucial stage in Russia's assertion on the international stage. By repeatedly vetoing UN Security Council resolutions aimed at imposing sanctions on Bashar al-Assad's regime, Russia has clearly demonstrated its determination to preserve its interests in Syria, while challenging Western postures. By supplying arms to the Syrian regime and coordinating air strikes with the Syrian army against rebel forces, Russia has not only actively supported Assad, but has also strengthened its influence in the region. This support, far from going unnoticed, has enhanced Russia's image as an influential international power, capable of intervening strategically in complex situations.

Syria is of great strategic importance to Russia. The alliance between Russia and Syria, which dates back to the Soviet era, has persisted over the decades, making Syria Russia's last real ally in the Middle East. As well as strengthening Russia's influence in this geopolitically critical region, this alliance also guarantees Russia's access to the Tartous naval base, which is Russia's only anchorage in the Mediterranean and a key component of its regional force projection. Syria is also a major customer for Russia's military industry. The two countries have signed arms contracts worth billions of dollars, and the Syrian army mainly uses Russian military equipment. Consequently, a change of regime in Syria could seriously threaten Russia's strategic and economic interests. This is why Russia has taken decisive steps to support the Assad regime throughout the Syrian crisis, including providing direct military assistance and using its veto in the UN Security Council to block actions that could harm the regime.

The invasion of Crimea and the war in Ukraine[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, a peninsula belonging de jure to Ukraine, triggering a major crisis between Russia and the West. This act was widely condemned by the international community, including the United States and the European Union, both of which imposed economic sanctions on Russia in response.

Russia's annexation of Crimea followed a political crisis in Ukraine where Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was deposed following popular protests, widely known as the Euromaidan. Russia viewed the overthrow of Yanukovych, who was widely regarded as pro-Russian, as a Western-backed coup. Shortly after the annexation of Crimea, armed conflict broke out in eastern Ukraine, particularly in the Donbass and Luhansk regions, where Russian-backed separatists declared independence from Ukraine.

The reign of the American Hyperpower: 1991-2001[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The American hyperpower[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the end of the Cold War and left the United States as the world's sole superpower, a period often described as unipolar. This position has given the United States unprecedented influence in the world. In the field of international security, the United States has played a central role in many conflicts and security issues around the world. It has led military interventions, such as the Gulf War in 1991 and the invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003, and has been a key player in the Middle East peace process. Economically, the US dollar has continued to be the world's reserve currency, and the US has been a major player in international economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. It has also played a leading role in promoting free trade and economic globalisation. In the field of technology, the United States has been at the forefront of many innovations, particularly in the fields of computing, the internet and biotechnology. American companies such as Apple, Google and Microsoft have become global giants. Culturally, the US has had a major influence through the spread of its popular culture, including film, music and television, as well as the English language.

The global hegemony of the United States is the result of a series of factors that have given the nation considerable influence on a planetary scale. First and foremost, the United States' privileged geographical position has played a pivotal role. Nestled between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, it has direct access to the continents of Europe and Asia. What's more, its proximity to Latin America gives it considerable influence in the region. Secondly, the military power of the United States is unrivalled. Its army, the strongest in the world, is equipped with military bases spread across the globe, and has the capacity to project its power on the international stage. Complemented by a substantial nuclear arsenal, the United States' military power is a formidable factor in its dominance. The political and economic system of the United States has also been a crucial vector of its supremacy. The American model, combining democracy and capitalism, was massively adopted worldwide following the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, as the world's largest economy, the United States exerts a major economic influence. Finally, the presence of the United States in international organisations is a further pillar of its dominance. Its key role in establishing post-Second World War global institutions such as the UN, the IMF and the World Bank has endured, and it continues to wield great influence within these organisations.

This period of American hegemony has often been referred to as the 'hyperpower' to emphasise the absolute superiority of the United States in world affairs.[4]

With the end of the Cold War, the landscape of American foreign policy underwent a profound transformation. The United States turned to a strategy more focused on advancing democracy and human rights worldwide, and protecting American economic interests internationally. Successive US leaders have embraced this policy regardless of their political affiliation. It has also been an era of intense debate about the appropriate application of American power on the world stage. Some advocates of a multilateral approach have advocated greater collaboration with other countries and international organisations. On the other hand, those who advocated a unilateral approach supported the idea that the United States should act according to its own interests, regardless of the opinion or intervention of other nations.

The rise of the neoconservative movement[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The rise of the neo-conservative movement in the United States during the 1990s played a pivotal role in redefining American foreign policy. The neoconservatives advocated the use of US military and economic strength to spread democracy and Western values across the globe, while combating authoritarian regimes and terrorist groups. This orientation became particularly evident following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, which triggered the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. The neoconservatives saw these conflicts as opportunities to establish democracy in these countries and overthrow authoritarian regimes that posed a threat to US security.

However, neoconservative policy has been criticised both at home and abroad. Many have criticised the neoconservatives for failing to take account of the complexity of regional conflicts, favouring military action over diplomacy and negotiation. Others argued that the effectiveness of democracy promotion depended on a more nuanced approach, involving deeper engagement with the societies concerned, rather than primarily the use of military force. Beyond these concerns, there were also worries about the impact of such interventions on regional stability and human rights, as well as questions about the legitimacy of the unilateral use of force by the United States without broad international support and explicit authorisation from the United Nations. These criticisms underlined the limits of American power and the need for the US to work closely with other countries and international organisations to resolve global conflicts.

The fight against terrorism[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Since the early 2000s, the United States has redefined its foreign policy, placing the fight against Islamist terrorism at the heart of its concerns. This new orientation is mainly due to the attacks of 11 September 2001, which caused the death of almost 3,000 people on American soil. These attacks, carried out by the terrorist group Al-Qaeda under the leadership of Osama bin Laden, had a profound effect on America and the world. In response to this unprecedented attack, the United States launched the "war on terror". This global military campaign was directed not only against Al Qaeda, but also against other Islamist terrorist groups. It led to the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003.

The "war on terror" has served as a justification for US intervention in several military conflicts, notably in Afghanistan and Iraq. However, this policy has been the subject of much criticism, both nationally and internationally. One of the most serious criticisms has been that this war has led to serious human rights violations. Among the most notable incidents were the abuses and torture committed in Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq by US military personnel. These actions have not only been condemned for their cruelty, but have also tarnished the reputation of the United States as a defender of human rights. The cost of the "war on terror" has also been a cause for concern. In financial terms, these conflicts have cost US taxpayers trillions of dollars. In human terms, the losses have been just as tragic, with thousands of American soldiers and even more Afghan and Iraqi civilians killed. These criticisms led to calls for an overhaul of US foreign policy, with a demand for greater accountability, transparency and respect for international law in the conduct of military operations.

The 1990s saw a number of US military interventions on a global scale, notably in Iraq and the Balkans. Although presented as efforts to establish peace and democracy, these interventions were widely criticised for their unilateral nature and their often devastating impact on civilian populations. This period was also marked by a series of terrorist attacks, including the attack on the World Trade Center in 1993 and those on the American embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998. These acts of terrorism played a major role in shaping US counter-terrorism policy. In response to these events, the FBI created a dedicated counter-terrorism division and the United States stepped up security measures in its embassies around the world. These actions demonstrate the evolution of the US national security strategy, which has begun to take the threat of international terrorism seriously, and to devote significant political and security resources to it.

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 marked a decisive turning point in US foreign policy, catalysing an increased focus on the fight against terrorism. These tragic attacks motivated the United States to redouble its efforts to combat international terrorist organisations. In response to the attacks, orchestrated by the terrorist group Al-Qaeda, the United States launched military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. These operations were aimed not only at dismantling Al Qaeda, but also at eliminating other perceived terrorist threats. These military campaigns marked the beginning of the "war on terror", a strategy that has profoundly influenced US foreign policy in the early 21st century.

The doctrine of preventive war[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

American unilateralism is particularly striking in the doctrine of pre-emptive war, promoted by the Bush administration in the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks. This controversial doctrine advocates the use of pre-emptive military force against nations or groups identified as threats to US national security, without waiting for direct aggression.

The central objective of this strategy was to neutralise potential threats before they materialised into actual attacks on the United States or its allies. This marked a major departure from the policy of deterrence that had prevailed during the Cold War, when force was only used in response to proven aggression.

This doctrine of pre-emptive war was the basis for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Bush administration justified the intervention on the basis of the subsequently discredited belief that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction that posed an imminent threat to the security of the United States. This doctrine and its application have come in for considerable criticism, both nationally and internationally, for destabilising the international balance and violating the principles of international law.

Intervention in Somalia[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The US intervention in Somalia began at the end of 1992, when President George H. W. Bush ordered the dispatch of troops to help end the famine caused by the ongoing civil war in the country. The operation, called "Restore Hope", was primarily humanitarian, aimed at securing the environment so that food aid could reach those most in need. However, the situation quickly became more complicated, violent and chaotic. The Battle of Mogadishu in 1993, also known as "Black Hawk Down" because of the Hollywood film that later dramatised the event, is a poignant example of the evolution of American involvement in Somalia. The battle resulted in the deaths of 18 American soldiers and marked a turning point in American intervention. Under pressure from public opinion, the United States began to withdraw its troops from Somalia and did so completely in March 1994.

Since then, the United States has maintained a more discreet presence in Africa, although it has participated in a number of military and humanitarian operations. For example, the US has played an active role in the fight against the Al-Shabaab terrorist group in Somalia and has provided humanitarian aid in response to various crises, such as the genocide in Darfur, Sudan. The failure of the intervention in Somalia has had a profound effect on American foreign policy. It demonstrated the limits and challenges of using military force to resolve humanitarian crises and contributed to a certain reluctance to become militarily involved in foreign conflicts in the future.

The Yugoslav conflict[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Even after the end of the Cold War, US policy continued to play a crucial role in Europe, particularly during the Yugoslav conflict that erupted in the 1990s. The collapse of Yugoslavia into several states gave rise to a series of violent conflicts, characterised by ethnic cleansing and war crimes.

The United States, in collaboration with its NATO allies, played an active role in efforts to bring these conflicts to an end. It has taken part in peace negotiations and supported NATO military interventions. One of the most notable interventions was Operation Deliberate Force in 1995, a series of air strikes against Serb forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina in response to the attack on Srebrenica and the massacre of thousands of Bosnian Muslims. Later, in 1999, in response to the Serbian government's brutal repression of the Kosovo Albanians, NATO, with significant support from the United States, launched another series of air strikes. Known as Operation Allied Force, its aim was to put an end to the violence and establish a secure environment for all the inhabitants of Kosovo, regardless of their ethnic origin.

US involvement in the peace negotiations was a key element in ending the conflicts in the Balkans, and Richard Holbrooke played a particularly important role in this. Richard Holbrooke, a seasoned American diplomat, was appointed Special Envoy for the Balkans by President Bill Clinton. His work was crucial in the negotiations that led to the Dayton Accords in 1995, which put an end to the war in Bosnia. Holbrooke and his team succeeded in bringing together the leaders of Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio for peace talks. Holbrooke is widely credited with the Dayton Accords, which established a multi-ethnic Bosnia-Herzegovina divided into two entities - the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (with a Bosnian-Croat majority) and the Republika Srpska (with a Serb majority). These agreements put an end to three and a half years of war, which left around 100,000 people dead and millions displaced. Richard Holbrooke is often cited as an example of an effective diplomat who used both pressure and negotiation to reach a peace agreement. However, the complex structure of post-Dayton Bosnia-Herzegovina has also been criticised for institutionalising ethnic divisions and creating an inefficient and corrupt political system.

The First Gulf War[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Iraq's invasion of Kuwait under the command of Saddam Hussein in August 1990 created a major international crisis. The UN immediately condemned the invasion and imposed a complete trade embargo against Iraq. However, faced with Saddam Hussein's determination to retain control of Kuwait, the UN authorised the use of force to liberate Kuwait in November of the same year.

The United States, under President George H. W. Bush, then organised an international coalition of 34 countries, including many members of NATO and the Arab League. The mission, known as Operation Desert Storm, began with an aerial bombing campaign in January 1991, followed by a ground offensive in February.

The first Gulf War was a rapid military success for the coalition. Iraqi forces were driven out of Kuwait and the country's territorial integrity was restored. Nevertheless, Saddam Hussein remained in power in Iraq, a situation that helped create the conditions for a second Gulf War in 2003.

This intervention also demonstrated the ability of the United States to form and lead an international coalition in response to aggression, while underlining its undisputed military leadership at the time.

The Second Gulf War[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Second Gulf War, also known as the Iraq War, began in 2003 with an invasion of Iraq by a US-led coalition, with the main objective of overthrowing Saddam Hussein. The main justification for this intervention was that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD) that posed a threat to international security, a claim that later proved to be inaccurate. Despite the absence of a UN mandate and opposition from several countries, the United States, under President George W. Bush, decided to intervene with the support of a few allies, including the United Kingdom. The invasion was swift and Saddam Hussein was overthrown in a matter of weeks.

The situation deteriorated rapidly after the invasion. Lack of post-war planning and strategic errors, such as the disbanding of the Iraqi army, led to insurgency and widespread sectarian violence. Iraq was plunged into chaos for several years, with thousands of deaths and millions of displaced people. The war in Iraq has been widely criticised, both for its initial justification and its management. It eroded the credibility of the United States on the international stage and contributed to a feeling of opposition to American unilateralism.

Intervention in Afghanistan[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Operation Enduring Freedom, launched by the United States and its allies in response to the attacks of 11 September 2001, was aimed at dismantling al-Qaeda and removing from power in Afghanistan the Taliban regime that had harboured and supported the terrorist group. The aim was also to capture or kill Osama bin Laden, the alleged mastermind behind the attacks. With the support of the Northern Alliance, an anti-Taliban Afghan faction, the coalition forces quickly overthrew the Taliban regime. However, capturing bin Laden proved more difficult than expected, and he managed to elude coalition forces for almost a decade before finally being located and killed in Pakistan in 2011. The intervention in Afghanistan has also involved a long-term effort to rebuild and stabilise the country, which has been plagued by conflict and political, economic and social difficulties. The United States and its allies have tried to establish a democratic government, train a new Afghan army and contribute to the country's economic development.

Despite the colossal efforts made by the United States and its allies to stabilise Afghanistan, the country continues to face immense challenges. The Taliban have regained ground and insecurity is omnipresent. Corruption is endemic within the government and institutions, hampering economic development and the provision of public services. The reconstruction mission has also been marked by strategic and tactical errors. For example, efforts to build an Afghan National Army capable of maintaining security have been hampered by problems of corruption, mismanagement and low morale. Similarly, efforts to create a democratic system of governance have often been undermined by the realities of tribal power and local allegiances. The situation is further complicated by Afghanistan's ethnic and cultural diversity, as well as interference from neighbouring countries such as Pakistan and Iran. In addition, the country continues to struggle with socio-economic problems such as poverty, illiteracy and lack of access to healthcare.

A controversial and criticised modus operandi[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The exercise of power by the United States in the international arena, particularly through the use of military force, has sometimes been a source of controversy and criticism, particularly over the last two decades. Unilateral actions, such as the invasion of Iraq in 2003, have met with opposition and disapproval from many countries, including some US allies.

The invasion of Iraq, justified by accusations that Iraq was in possession of weapons of mass destruction - accusations which turned out to be false - was considered by many observers to be a violation of international law. Moreover, the instability that followed the overthrow of Saddam Hussein's regime led to a rise in extremism in the region, with tragic consequences for the Iraqi population and for international security.

Similarly, the use by the United States of drones to carry out targeted strikes, mainly in Afghanistan and Pakistan, has raised concerns about the legality of these actions under international law and their humanitarian impact. These attacks have often caused civilian casualties and have been criticised for their lack of transparency.

These and other actions have tarnished the image of the United States on the international stage, undermining its legitimacy and influence as a world leader. Although the United States remains a superpower with considerable influence, these controversies have highlighted the challenges it faces in exercising its power effectively and responsibly.