The era of the superpowers: 1918 - 1989

Based on a lesson by Ludovic Tournès[1][2][3]

Perspectives on the studies, issues and problems of international history ● Europe at the centre of the world: from the end of the 19th century to 1918 ● The era of the superpowers: 1918 - 1989 ● A multipolar world: 1989 - 2011 ● The International System in Historical Context: Perspectives and Interpretations ● The beginnings of the contemporary international system: 1870 - 1939 ● World War II and the remaking of the world order: 1939 - 1947 ● The international system in the test of bipolarisation: 1947 - 1989

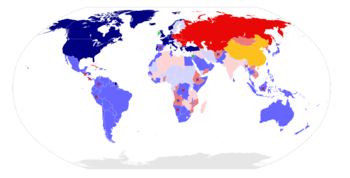

It is plausible to argue that the era of the superpowers began in 1918, at the end of the First World War. The war shaped an international landscape conducive to the rise of two major protagonists: the United States and the Soviet Union. The persistent geopolitical and economic tensions that followed the war paved the way for the rise of these nations. However, the period from 1945 to 1989 is commonly seen as the zenith of the superpower era, marked by heightened rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union and an unbridled arms race. It was also an era of major events, such as the Korean War, the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam War and the space race, all of which left their mark on world geopolitics.

The post-First World War period was characterised by the gradual decline of Europe as the centre of world power, giving way to the emergence of new powers, including the United States and the Soviet Union. The war profoundly weakened the nations of Europe, overwhelmed by immense human and material losses. War debts overshadowed the European economy, which found it difficult to recover. In addition, the rise of nationalist movements and authoritarian regimes in Europe generated political and social tensions, further contributing to the region's decline.

At the same time, the United States took off as a major economic power, thanks to its prosperous industry and its participation in the First World War. The Soviet Union also gained significant importance after the revolution of 1917, which gave birth to a socialist state. Over time, the United States and the Soviet Union have strengthened their economic, political and military influence, overshadowing Europe and other parts of the world. The rivalry between these two superpowers shaped global geopolitics, leaving an indelible mark on the history of the 20th century.

The outcome of the First World War[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The First World War undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the course of twentieth-century history. Its devastating effects, ranging from considerable loss of life to the massive destruction of Europe and other regions of the world, reshaped the international political and socio-economic landscape.

With nearly 8.5 million soldiers killed and around 13 million civilians decimated, the human toll of war is staggering. The merciless battles ravaged huge swathes of territory, demolishing towns and villages, destroying infrastructure and leaving desolate landscapes in their wake. In addition to the direct victims, millions of others were scarred by physical and psychological injuries, diseases spread by unhealthy conditions, as well as famine and deprivation caused by the blockade and the disruption of supply systems. This suffering had a lasting effect on the survivors and subsequent generations.

The impact of the First World War extends far beyond its catastrophic human and material losses. It considerably transformed the demographic and geographical landscape of many countries, while initiating major social, political and economic upheavals.

Demographically, the war created a gender imbalance, with a generation of men decimated at the front, and a generation of women having to adapt to a more dominant role in society and the economy, paving the way for women's rights movements. In addition, the collective shock and grief left its mark on the psyche of the belligerent nations, creating what has been called the "Lost Generation". Geographically, the map of Europe was redrawn by the Treaty of Versailles and other peace agreements, creating new states and redefining existing borders. These changes fuelled nationalist and ethnic tensions, paving the way for future conflicts, notably the Second World War. Socially, the war destabilised traditional social and political hierarchies, contributing to the rise of radical social and political movements such as communism in Russia, fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany. Economically, the war disrupted the economies of the belligerent countries, leading to massive inflation, crushing debts and high unemployment. These economic problems contributed to the Great Depression of the 1930s and fuelled the political instability that led to the Second World War. The First World War not only ushered in a new era of global conflict, but also laid the foundations for many of the tensions and transformations that continued to shape the world throughout the 20th century.

The First World War caused massive population movements. These population movements were due to several factors, including forced displacement by governments, military occupation, flight from combat zones and the evacuation of civilians from threatened areas. Millions of people were uprooted from their homes and forced to seek refuge elsewhere. The worst affected areas were those of Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where the collapse of the Ottoman, Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian empires created a huge political and social vacuum. These displacements created considerable humanitarian problems, including a lack of food, shelter and medical care. What's more, the end of the war did not mean the end of population displacement. The Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, for example, sanctioned a forced exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, displacing over a million people on each side. These massive population movements left lasting scars on the societies affected and laid the foundations for numerous ethnic and territorial conflicts throughout the 20th century.

The economic impact of the First World War on Europe was devastating, and its effects continued long after the end of hostilities. Not only did the war lead to massive destruction of infrastructure and industrial production, it also caused a significant loss of labour due to mass deaths and war injuries. In addition, to finance their war efforts, countries incurred huge debts to domestic and foreign financial institutions. The United Kingdom and France, for example, contracted huge debts with the United States. These war debts, coupled with inflation and economic instability, placed a heavy financial burden on the belligerent countries. Germany, in particular, was severely affected. The Treaty of Versailles imposed crushing war reparations on Germany, which further worsened the country's economic situation. Economic hardship contributed to political and social instability, creating fertile ground for the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. The post-war economic crisis was also a major factor in triggering the Great Depression in the 1930s. Countries struggled to repay their war debts and rebuild their economies, leading to global economic instability. The effects of this crisis lasted until the Second World War and shaped the global economy for decades to come.

The political and social consequences of the First World War were as profound as its military and economic consequences. The most immediate impact was the collapse of several European empires: the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire. The collapse of these empires led to a radical reshaping of the political map of Europe and the Middle East. New nations were created, often on the basis of nationalist and ethnic claims, which in turn fuelled new political and territorial tensions. The collapse of the Russian Empire paved the way for the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the establishment of the world's first communist nation, the Soviet Union. This development had major political and social implications, not just for Europe but for the whole world, giving rise to an ideology that would shape much of the twentieth century. Germany, which suffered national trauma after defeat and the humiliating Versailles peace treaty, saw the emergence of the Nazi party and fascism under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. This rise of fascism, also visible in Italy with Benito Mussolini, led to the Second World War. The First World War radically altered the political and social landscape of Europe and the world. It sowed the seeds of new ideologies and conflicts that have shaped the history of the twentieth century.

The great powers at the end of the war[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

France: Post-war challenges[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

France endured a terrible ordeal during the First World War. The loss of life was staggering: around 1.5 million French soldiers lost their lives, representing a significant fraction of the country's total population. This hecatomb had a devastating impact on French society, causing a demographic and socio-economic crisis. The material destruction in France was also enormous. The most intense fighting took place on French soil, particularly in the north-eastern regions of the country, such as Picardy, Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Alsace-Lorraine. Entire towns and villages were razed to the ground, infrastructure destroyed and farmland rendered unusable by shells and trenches. The image of the "lunar landscapes" of these devastated regions remains one of the most striking images of the war. Economically, the costs of the war for France were immense. The country spent huge sums to finance the war effort, which led to massive inflation and increased its national debt. Reconstruction of the devastated areas required major investment, adding to the economic burden of the war. The First World War left lasting scars on France, transforming its social, economic and physical landscape for decades to come.

The First World War left a profound economic imprint on France. The key industrial regions of the north and east, home to much of the country's industrial and mining infrastructure, were particularly hard hit by the fighting. The damage inflicted on these regions led to a fall in industrial production and a rise in unemployment, with lasting effects on the French economy. Transport infrastructure, essential to trade and industry, has also been severely affected. Rail networks, bridges, ports and roads were destroyed or damaged, disrupting trade and population movements. What's more, the financial cost of the war to France was colossal. To finance the war effort, France had to borrow heavily from abroad, particularly from the United States and the United Kingdom. This left the country with a huge war debt that put considerable pressure on the national economy for decades after the end of the war. The costs of rebuilding devastated areas and repairing infrastructure were also considerable, adding to the financial burden. As a result, the French economy experienced a period of difficulty and instability in the post-war period, with high inflation and slow economic growth. The economic impact of the First World War on France was devastating and its repercussions were felt for decades after the war ended.

The First World War brought about major social and cultural changes in France, as it did in other countries affected by the conflict. One of the most remarkable changes concerned the role of women. With so many men mobilised to the front, women were called upon to take on traditionally male roles in society. They began to work in large numbers in factories, offices, farms, shops, and even in some public services, such as the post office and transport. This led to a significant increase in women's participation in the country's economic life. This development has also had an impact on the perception of women's role in society and has helped to change attitudes towards women's rights. Although the right to vote was not granted to women in France until after the Second World War, in 1944 women's participation in the war effort paved the way for this development. What's more, the First World War had a major impact on French culture and values. The brutality and horrors of war provoked a profound questioning of traditional ideals and values. This was reflected in the artistic and literary movements of the time, such as Dadaism and Surrealism, which expressed a break with the past and a deep disillusionment with traditional conventions and authorities. The social and cultural impact of the First World War in France was considerable, bringing about lasting changes in the country's society and culture.

Despite the scale of the challenges posed by the material, economic and social damage of the First World War, France demonstrated a remarkable capacity for resilience. On the economic front, France undertook a vast reconstruction operation in the regions devastated by the war. With the financial aid obtained through war reparations, foreign loans and internal investment, the country succeeded in rebuilding its industrial and transport infrastructure, relaunching its agricultural production and restoring its industrial output. France also experienced a cultural renaissance after the war. Despite, or perhaps because of, the horrors and losses suffered during the war, France continued to be a world centre of innovation and creativity in the arts, literature and philosophy. It was in the 1920s and 1930s that artistic movements such as Surrealism, Cubism and Existentialism flourished in France, affirming the country's cultural influence. The period between the wars was marked by considerable challenges for France, but also by major achievements. Despite the deep scars left by the war, France showed great resilience and succeeded in reasserting its position as one of Europe's great economic and cultural powers.

Germany: From Empire to Weimar Republic[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Germany was severely affected by the First World War, both in human and economic terms. The human toll for Germany was colossal, with an estimated 1.7 to 2 million dead, in addition to several million wounded and maimed. Economically, the impact of the war and its consequences were profoundly destructive. The financial cost of waging war was enormous. The country was forced to borrow heavily to finance the war effort, leading to high inflation. The German economy was also weakened by the Allied naval blockade, which disrupted foreign trade. The economic impact of the war was exacerbated by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war. Germany was held responsible for the war and was forced to pay extremely heavy war reparations to the Allies. The amount of the reparations, set at 132 billion gold marks, was well beyond Germany's financial capacity. These reparations, combined with the loss of productive territory and the reduction in Germany's industrial capacity imposed by the Treaty, plunged the German economy into a deep crisis. Inflation rose dramatically, reaching its peak in the hyperinflation of 1923, which wiped out the savings of many Germans and caused social and political instability. The consequences of the First World War for Germany were devastating, leaving lasting scars that shaped the country's history in the decades that followed.

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, had far-reaching consequences for Germany and was a source of discontent and resentment among the German population. From a financial point of view, the treaty required Germany to pay enormous reparations to the Allies for the damage caused during the war. As mentioned earlier, these reparations payments put enormous pressure on the already weakened German economy, leading to problems such as inflation and unemployment. On the military front, the treaty also required Germany to drastically reduce its armed forces. The German army was limited to 100,000 men, and the navy was restricted to a few specific warships with no submarines. Germany was also banned from having an air force. In territorial terms, Germany lost around 13% of its pre-war territory and 10% of its population. Significant territories were ceded to Poland, Belgium, Denmark and France, and others were placed under the supervision of the League of Nations. For many Germans, these terms were seen as excessively punitive and humiliating. The sense of injustice was exacerbated by the treaty's "war guilt clause", which placed responsibility for starting the war on Germany and its allies. This resentment towards the Treaty of Versailles helped fuel political instability in Germany and was exploited by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in their rise to power.

The end of the First World War saw a period of revolution and political upheaval in Germany. Germany's capitulation and the conditions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles created a climate of discontent and social disorder. In November 1918, following Germany's defeat in the First World War and the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II, a republican government was established under the leadership of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). This became known as the Weimar Republic. However, the new government faced many challenges, including opposition from forces on the right and left. Inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917, various left-wing groups in Germany, notably the Spartacists led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, sought to establish a communist government. This led to the Spartakist revolt in Berlin in January 1919, which was violently suppressed by the government with the help of paramilitary free corps. The Weimar Republic continued to be shaken by political and economic instability throughout its existence, with revolts, coup attempts, hyperinflation and a great depression. These problems eventually paved the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in the early 1930s.

Despite the terrible loss of life and the financial reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, Germany's infrastructure remained relatively unscathed during the First World War. Unlike France, Belgium and parts of Eastern Europe, where the fighting was particularly devastating to towns, villages and industries, most of the fighting in the First World War took place outside German territory. This situation enabled Germany to reorganise parts of its economy more quickly after the war. However, economic reconstruction was hampered by the heavy war reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles and internal political instability. The Great Depression of the 1930s also dealt a severe blow to the German economy. Unemployment rose dramatically and public discontent with the government of the Weimar Republic increased. It was against this backdrop of economic crisis and political instability that Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party managed to gain popularity, promising the restoration of German prosperity and greatness, which eventually led to the Second World War.

Austria-Hungary: The end of an empire[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, a conglomeration of different peoples and nations united under the Habsburg sceptre, was one of the main losers of the First World War. This vast empire, which extended over much of Central and Eastern Europe, was dismantled as a result of the conflict. The beginning of the end for the Austro-Hungarian Empire came when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in June 1914, an event that sparked off the First World War. The Empire found itself in the camp of the Central Powers, alongside Germany and the Ottoman Empire. During the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire suffered heavy losses and faced growing economic and social problems, including food shortages and widespread discontent among its various peoples. The situation became even more unstable when Austro-Hungarian troops began to suffer a series of defeats. With the defeat of the Central Powers in 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed. Under pressure from the Allies and internal nationalist movements, the empire was dismantled. The peace treaties of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Trianon, in 1919 and 1920 respectively, confirmed the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and led to the creation of several new states, including Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and others. This break-up profoundly reshaped the political map of Central Europe.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was made up of a complex mix of ethnic, linguistic and cultural groups, including Austrians, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Serbs, Croats, Italians, Poles, Ukrainians, Romanians and others. These diverse groups had different allegiances, aspirations and grievances, which created internal tensions throughout the Empire's existence. The First World War exacerbated these tensions. The harsh conditions of war, including food shortages and high casualties, intensified discontent among the different nationalities. In addition, military defeats and economic problems weakened the authority of the Empire and stimulated nationalist aspirations. The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the First World War was largely the result of these internal tensions. With the defeat of the Empire, the various nationalities seized the opportunity to claim their independence or join forces with other nations. This led to the creation of several new states, including Austria and Hungary as separate nations, and redefined the political landscape of Central Europe.

The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire led to the creation of many new states in Central and Eastern Europe. However, the way in which these new states were created often led to long-term problems. Firstly, the borders of these new states were often drawn arbitrarily, without taking into account the ethnic, linguistic and cultural realities on the ground. This created many isolated ethnic minorities within new states that did not necessarily represent them. For example, Hungary lost around two thirds of its territory and one third of its population to neighbouring countries, creating large Hungarian minorities in Romania, Slovakia and Serbia. Secondly, these new borders were often contested, leading to tensions and conflicts between the new states. Border disputes fuelled nationalist tensions and were often used by authoritarian leaders to mobilise domestic support. Finally, the creation of these new states created a power vacuum in the region, allowing outside powers such as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union to seek to extend their influence. This had profound consequences for Central and Eastern Europe throughout the rest of the twentieth century, culminating in the Second World War and the Cold War.

The break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire left a power vacuum in the region, which facilitated the expansion of German influence in Central Europe, especially during the rise of the Third Reich before the Second World War. Moreover, the demise of this great empire changed the dynamics of power in Europe, with repercussions for the overall balance of power. In terms of political and economic repercussions, the demise of the Empire created many new states, as we have already mentioned. These new countries faced immense challenges, including establishing stable governments, building viable economies, managing ethnic tensions and defining their relationships with their neighbours and with the world powers. These challenges have contributed to instability in the region, with conflicts and tensions persisting for many years. From an economic point of view, the fragmentation of the Empire also had major consequences. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had an integrated market with a common transport system, currency and legal system. With its dissolution, these economic links were severed, leading to economic disruption and adjustment difficulties for the new states. These economic challenges were exacerbated by the Great Depression of the 1930s and contributed to political and social instability in the region.

Ottoman Empire: Towards the Republic of Turkey[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The First World War was the final straw for the Ottoman Empire, which had been in decline for decades prior to the conflict. Engaged on the side of the Central Powers during the war, the Ottoman Empire suffered heavy military losses and a severe economic crisis. At the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire was dismembered by the Treaty of Sèvres signed in 1920. This treaty considerably reduced the Empire's territory, ceding large swathes of land to Greece, Italy and other countries. It also recognised the independence of several nations in what were formerly Ottoman territories, such as Armenia, Georgia and others. However, the terms of the Treaty of Sevres were widely rejected in Turkey, which contributed to the emergence of the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. This movement led to the Turkish War of Independence, which overthrew the Ottoman Sultanate and resulted in the creation of the Republic of Modern Turkey in 1923. The new Turkish state abandoned many features of the Ottoman Empire, such as the caliphate, the millet system and decentralised administration, and embarked on a series of reforms to modernise the country and transform it into a secular nation-state based on the European model. The First World War not only marked the end of the Ottoman Empire, but also laid the foundations for modern Turkey.

Founded in the early 14th century, the Ottoman Empire became one of the largest and most powerful political entities in the world at its peak in the 16th century. The Empire ruled over vast territories in Europe, Asia and Africa and played a major role in the political, economic and cultural history of these regions. However, during the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire began to decline under the pressure of various factors. Internally, the Empire was plagued by ethnic and religious tensions, corruption, administrative inefficiency and an ageing infrastructure. Reform movements, such as the Tanzimat of the mid-nineteenth century, attempted to modernise the Empire and make it more competitive with the European powers, but these efforts were often met with strong resistance. At the same time, the Ottoman Empire came under increasing pressure from the European powers, which sought to extend their influence over Ottoman territories. Wars with Russia and other states led to the loss of territory and weakened the Ottoman economy. The First World War exacerbated these challenges for the Ottoman Empire. The war effort drained the Empire's resources and exacerbated internal tensions. Ultimately, the war precipitated the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and led to the formation of the modern Republic of Turkey.

During the First World War, the Ottoman Empire chose to align itself with the Central Powers, notably Germany and Austria-Hungary. However, this alliance failed to reverse the course of the empire's decline. The Gallipoli campaign of 1915, led by British and French forces with the support of Australian and New Zealand troops, was a major attempt to seize Constantinople and overthrow the Ottoman Empire. Although the campaign ultimately failed, it weakened the Empire and led to significant territorial losses. In addition, the Ottoman Empire was also engaged in conflicts with British forces in the Middle East, notably in Palestine and Mesopotamia. These battles resulted in further territorial losses for the empire and weakened its ability to maintain control over its remaining territories. At the end of the war, under the Treaty of Sèvres signed in 1920, the Ottoman Empire was dismantled. However, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, an Ottoman military officer, rejected the treaty and led a war of independence that resulted in the creation of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the redrawing of its territories after the First World War radically altered the political map of the Middle East. This was achieved through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres and the establishment of the League of Nations mandate system, under which certain former provinces of the Ottoman Empire became territories under French administration (such as Syria and Lebanon) or British administration (such as Iraq, Palestine and Jordan). The creation of these new states was often accompanied by tensions and conflicts, due to disputed borders, ethnic and religious differences, and geopolitical rivalries. In addition, the question of Palestine became a major source of conflict in the region, ultimately leading to the creation of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent Arab-Israeli conflicts. As for Turkey, it is the direct result of the transformation of the former heartland of the Ottoman Empire into a modern republic under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, following a successful war of independence against Allied occupation forces and Ottoman royalist forces. These changes had a lasting impact on the region's political stability, inter-state relations and socio-economic development.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire reshaped the geopolitics not only of the Middle East, but also of South Eastern Europe. The vacuum left by the empire created fertile ground for international rivalries, nationalist aspirations and sectarian conflicts. The new borders drawn after the war often ignored the ethnic and religious realities on the ground, leading to persistent conflicts and tensions. Moreover, the arbitrary division of the Middle East also created problems of legitimacy for the new states, which often appeared to be artificial constructs in the eyes of their citizens. In South-East Europe, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire was also followed by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which established Turkey's modern borders and led to a massive population exchange between Greece and Turkey, creating large minorities in both Greece and Turkey, which are still a source of tension between the two countries. The consequences of the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire are still felt today, in the form of ongoing conflicts, geopolitical tensions and development challenges in the region.

Russia: From Tsarist autocracy to the USSR[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Russia was greatly affected by the First World War. Its massive losses, in terms of both human lives and resources, exacerbated the social and economic problems that were already plaguing the country. Popular discontent with the Tsarist regime was exacerbated by the mismanagement of the war and shortages of food and basic necessities. It was in this troubled context that the February Revolution of 1917 broke out, overthrowing Tsar Nicholas II and installing a provisional government. However, this new government was unable to respond to the people's demands, in particular an end to Russia's participation in the war and land reform. What's more, it faced growing opposition from the Soviets, the workers', soldiers' and peasants' councils, which had gained in influence and power. It was in this atmosphere of political and social unrest that the October Revolution of 1917 took place. Led by Vladimir Lenin, the Bolsheviks seized power and proclaimed the creation of Soviet Russia. The new regime immediately sought to end Russia's involvement in the war and began to implement radical reforms based on communist ideals. The First World War played a key role in Russian history, precipitating the fall of the Tsarist regime and paving the way for the creation of the Soviet Union.

The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 brought about a radical change in Russia's war policy. The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, were determined to put an end to Russia's participation in the war, which was one of their main slogans when they took power. To put this intention into practice, the new government began peace negotiations with the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire). These negotiations culminated in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed in March 1918. This treaty marked Russia's official exit from the First World War, but on very harsh terms. Russia had to give up a large part of its European territory, including Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland. It also had to recognise the independence of Ukraine and Belarus, which had previously been under Russian control. Although these territorial losses were heavy, the Bolsheviks were convinced that this was the price they had to pay to end the war and concentrate on consolidating their power in Russia. However, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was cancelled by the Armistice of 1918, which marked the end of the war, and most of the lost territories were recovered by Russia.

Russia's exit from the First World War caused a major strategic shift in the balance of power. Russia was a crucial ally of the Allied Powers, and its withdrawal from the conflict allowed the Central Powers to concentrate more resources on the Western Front. This increased the pressure on the Allies on the Western Front, where most of the fighting was now taking place. This led the Allies to seek new support to compensate for the loss of Russia. It was in this context that the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917 played a crucial role. The United States was a rising power at the time and had significant resources in terms of population, industry and finance. American involvement not only provided direct military support by sending troops to the Western Front, but also financial and material support for the Allies. The United States' entry into the war also had a major psychological impact. It boosted the morale of the Allies and helped to weaken that of the Central Powers, by showing that the Allies were capable of mobilising new support despite the difficulties. Although Russia's exit presented challenges for the Allies, it also contributed to the entry of the United States into the war, which played a crucial role in the final outcome of the conflict.

The Bolshevik Revolution radically transformed Russia. It marked the end of the Russian Empire and established a communist regime that had a profound impact on all aspects of Russian life. Politically, the revolution put an end to the Tsarist monarchy and established a communist system based on Marxism-Leninism. This led to the establishment of a one-party state in which the Communist Party held absolute power. On the economic front, the new regime nationalised industry and agriculture, putting an end to private ownership. This radical change created a planned economy, where all economic decisions were taken by the government. This had far-reaching consequences, with periods of growth but also serious shortages and economic crises. In social terms, the revolution brought about profound changes in Russia's social structure. The old elites were dispossessed and often persecuted, while the workers and peasants became the regime's new elites. The regime also sought to eradicate illiteracy and promote gender equality. However, these transformations came at the price of great violence and political repression. The civil war that followed the revolution resulted in millions of deaths and widespread suffering. Political repression intensified in the years that followed, with massive purges and the creation of a police state. The Bolshevik Revolution profoundly transformed Russia, leading it down the road to communism and ushering in a new era in its history.

Great Britain: War and the British Empire[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The First World War had a profound impact on Great Britain, despite the fact that the fighting did not take place on its territory. In human terms, Britain suffered great losses, with more than 700,000 servicemen killed and millions more wounded. This had a devastating effect on a whole generation and left a deep mark on British society.

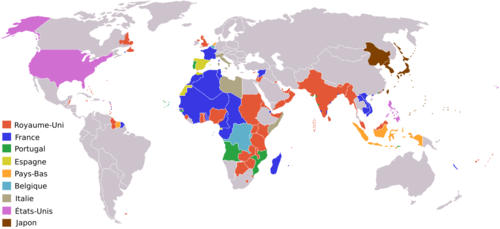

The First World War allowed Britain to expand its colonial empire, although this was tempered by the independence movements that were developing in many of its colonies. During the war, Britain and its allies seized several German colonies, notably in Africa and the Pacific. Following the Treaty of Versailles, several of these territories were placed under British mandate by the League of Nations. In addition, with the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain gained de facto control over several territories in the Middle East, including Palestine, Jordan and Iraq. These gains were formalised by the Sykes-Picot agreements and the League of Nations mandate. However, these territorial gains also created new challenges for Great Britain. Managing these territories and meeting the expectations of local populations for autonomy and governance was often a complex and difficult task. What's more, the cost of running the empire came on top of the economic problems Britain faced in the aftermath of the war. Although the First World War allowed Britain to expand its empire, it also exacerbated the challenges facing the empire, ultimately contributing to its decline in the twentieth century.

Despite its territorial successes, Britain faced significant domestic challenges after the First World War. Economically, the war had cost the country dearly, leading to a huge increase in the national debt. The need to repay these debts, together with the cost of reconstruction and the conversion from a wartime to a peacetime economy, put enormous pressure on the British economy. In addition, the country faced high inflation, rising unemployment and stagnant economic growth. Socially and politically, the country was marked by unrest. The labour movement became more radical and militant after the war, with a series of major strikes that challenged the traditional social order. In addition, the Irish question became more pressing, with the rise of the Irish independence movement, which culminated in the Irish War of Independence and the partition of Ireland in 1921. Although Britain succeeded in expanding its colonial empire after the First World War, it faced a series of significant challenges within its borders that marked the country for many years after the end of the war.

The impact of the war on Europe in general[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The First World War caused immense human losses in Europe, with around 10 million deaths, mainly men. The total number of deaths directly attributable to the war is enormous, but the figure becomes even more tragic when we consider the indirect losses. These indirect losses are due to factors such as malnutrition, disease, lack of medical care and exposure to the elements due to the destruction of housing and infrastructure. Many civilians were killed in war zones as a result of bombing, fighting, forced displacement, starvation and disease. For example, the Spanish flu of 1918-1919 claimed millions of lives worldwide, and many of these deaths were directly linked to the conditions created by the war. The First World War also caused waves of refugees and forced population movements on a scale never seen before. Civilians who were forcibly displaced from their homes often suffered from malnutrition, disease and other precarious health conditions. The impact of war on the population is not limited to the dead. The wounded, mutilated and psychologically traumatised affected millions of people, with lasting consequences for the health of the European population. The "gueules cassées", as disfigured soldiers were known, became a poignant symbol of the war. The impact of the First World War on the European population was catastrophic, resulting not only in direct loss of life, but also in long-term suffering and disruption for survivors and their families.

The massive loss of life during the First World War had a major impact on Europe's demography. Many countries saw their working-age male populations fall dramatically, with long-term consequences for their economies, societies and cultures. In France, for example, the war killed or injured a large proportion of the male population. The result was a demographic imbalance between the sexes, leading to a shortage of men of working age and a surplus of single women, a phenomenon often referred to as "Le surplus de femmes". In addition, the reduction in the working population slowed economic growth after the war. In Germany, the war also caused heavy loss of life and exacerbated existing economic and social problems. After the war, Germany experienced a period of economic and political turmoil, including hyperinflation and rising popular discontent, which ultimately led to the rise of the Nazi party. Russia was one of the countries hardest hit by the war, with high mortality rates among soldiers and civilians. The war, followed by the Bolshevik revolution and civil war, devastated the country and led to massive loss of life and displacement. In the UK, the war also resulted in heavy loss of life, with hundreds of thousands killed and injured. These losses had an impact on British society, with a generation of men decimated, women entering the workforce in large numbers, and major social and political disruption. Overall, the First World War left an indelible mark on the demography of Europe, with long-term consequences for the economy, society and politics of every country involved.

The term "hollow classes" refers to the drastic reduction in the number of men of childbearing age following the First World War. This had an impact on the birth rate, with a reduced number of births in the 1920s and 1930s, hence the term "hollow generation" or "hollow classes". The economic and social implications of this phenomenon were profound. Economically, the fall in the number of births led to a reduction in the working population, which may have slowed economic growth. In terms of the workforce, the loss of a large proportion of the working-age generation has led to a shortage of workers, with repercussions for industrial and agricultural production. Socially, this situation has led to a gender imbalance, with an increase in the number of single and widowed women, a situation that has helped to transform traditional gender roles. In particular, this has enabled women to enter the labour market more widely and has promoted female emancipation. In addition, the decline in the young population has had an impact on family and social structures, with fewer young people to look after the older generations. This has put additional pressure on social protection systems and may have contributed to social and political tensions. The "hollow classes" are an example of the long-term demographic consequences of the war, which had an impact on the economy, society and politics of many European countries for decades after the end of the war.

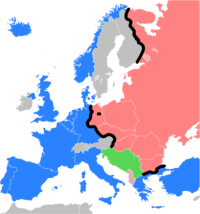

The First World War profoundly transformed the map of Europe and reorganised the balance of power on a global scale. In Europe, the defeated central empires - the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire - were dismantled. New nation states were created, such as Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Poland. The borders of many other countries were redrawn. These changes often created tensions and conflicts, not least because of competing territorial claims and heterogeneous populations within the new states. On a global scale, the war marked the beginning of a decline in European influence and the emergence of new powers. The United States, which had remained outside the conflict until 1917, emerged as an economic and military superpower. Its role in the war and in the subsequent peace negotiations marked its entry into world politics. In addition, the Russian Revolution of 1917 marked the birth of the Soviet Union, which became another global superpower in the course of the twentieth century. The establishment of a communist regime in Russia also created a new ideology that had an impact on international relations and conflicts in the 20th century. The First World War was not only a human and economic catastrophe, it also profoundly transformed the political and geopolitical order of the world.

The scale of destruction and loss of life during the First World War overturned pre-existing conceptions of society and culture in Europe and beyond. Culturally, the war profoundly affected the arts and literature. Writers and artists attempted to represent the horrors of war and to give meaning to this unprecedented experience. Modernism, which had begun before the war, was strongly influenced by it, with movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism seeking to break with traditional conventions and express the absurdity and alienation of the war experience. On a philosophical and intellectual level, the war also provoked a questioning of many fundamental principles of Western thought. Nineteenth-century optimism about progress, faith in reason and science, and confidence in liberalism and capitalism were all shaken. Philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and writers such as T.S. Eliot have explored these themes of disillusionment and disenchantment. On a social level, the war also provoked a questioning of the authority of traditional elites and institutions. The failure of governments to prevent war, and their handling of it, led to a mistrust of political, military and religious institutions and leaders. This contributed to the rise of revolutionary and social protest movements in the inter-war period. The First World War left a lasting legacy not only in terms of political and geopolitical upheaval, but also in terms of cultural and intellectual transformation.

The devastating consequences of the First World War triggered a profound crisis that affected all aspects of life, from the arts and philosophy to politics. In the field of art, movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism emerged as a reaction to the horror and absurdity of war. Dadaism, for example, was founded in Zurich during the war by a group of pacifist artists and writers who rejected the values of bourgeois society, which they held responsible for the war. Surrealism, which emerged after the war, continued to question logic and reason, exploring instead the role of the subconscious and the irrational. On a philosophical level, existentialism became an important school of thought after the war, emphasising the individual, freedom and authenticity. Existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus explored themes such as absurdity, despair and alienation, reflecting the anguish and disillusionment of the post-war period. Politically, the disillusionment and instability that followed the war also contributed to the rise of radical and far-right political movements. In the 1920s and 1930s, authoritarian regimes came to power in several European countries, most notably Nazi Germany. These movements often promised order and stability in response to post-war instability and crisis. It is clear, then, that the First World War had a profound and lasting impact on European civilisation, influencing not only politics and geopolitics, but also art, philosophy and culture.

The geopolitical consequences of the First World War were immense and profoundly altered the global political landscape. Firstly, the peace treaties that followed the end of the war dismantled the central empires - Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Tsarist Russia. The territories of these empires were divided up and new nation states were created, such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria and Hungary. The victorious countries also acquired new territories and colonies. The war also marked the end of European domination of world affairs. The European powers, although victorious, were financially and humanely exhausted, and their influence on the international stage began to decline. This paved the way for the rise of the United States and the Soviet Union, which became the new global superpowers in the post-war era. Finally, the war also changed alliances and international relations. The system of alliances that had played a role in triggering the war was replaced by the League of Nations, an international organisation designed to prevent future conflicts. However, despite these efforts, tensions and rivalries persisted, ultimately leading to the Second World War a few decades later. The First World War transformed global geopolitics, with effects that reverberated throughout the 20th century.

The First World War had a devastating economic impact on European countries. To finance the war, many governments borrowed heavily and issued currency. This led to high inflation, which eroded the value of money and made it more difficult to repay debts. As a result, after the war, many countries found themselves with huge public debts. The war also caused significant destruction to Europe's industrial and agricultural infrastructure, leading to a sharp fall in production. To compensate for this loss, many countries had to import goods, which contributed to the increase in debt. In addition, as millions of soldiers returned to civilian life after the war, unemployment rose sharply. At the same time, demand for war goods plummeted, leading to massive redundancies in industry. All these factors - inflation, debt, falling output and unemployment - led to an economic depression in many countries after the war. This situation was exacerbated by the war reparations imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, which created an additional economic burden. Economic reconstruction after the First World War was therefore a long and difficult process, made even more complex by the Great Depression of the 1930s. In many countries, it took several decades to return to pre-war levels of prosperity.

Peace Conference: From Wilson's vision to treaties[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The Paris Peace Conference was dominated by the "Big Four": US President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. Japan was also represented, but with less influence.

The defeated nations - Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire - were not invited to take part in the initial discussions at the conference. In fact, Germany was only allowed to send a delegation to Paris when the Treaty of Versailles was virtually finalised. When the German delegates saw the treaty, they were horrified by the harsh conditions and heavy reparations it imposed on Germany. Similarly, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire were not involved in the discussions that led to the redefinition of their borders and the creation of new states on their former territories. Decisions were taken without their consent, leading to strong protests and resentment. This exclusion of the defeated nations from the peace talks is one of the reasons why the peace treaties that were signed at the end of the Paris Peace Conference were widely perceived as unfair and helped to sow the seeds of future conflicts, including the Second World War.

The "Big Four" were the leaders of the four main Allied nations: US President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando. These leaders played the most important role in the negotiations and decision-making during the peace conference. President Wilson was a key figure at the conference and presented his famous "Fourteen Point Programme" which included ideas to promote peace, including freedom of the seas, self-determination of peoples and the creation of a general association of nations, which would later become the League of Nations. Prime Minister Clemenceau, nicknamed the "Tiger", represented the French position which aimed to ensure France's security against any future German aggression. He wanted substantial war reparations from Germany and the demilitarisation of the German border with France. David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, tried to strike a balance between Clemenceau's demands and Wilson's ideals. He wanted a just peace settlement, but was also concerned not to humiliate Germany to the point of provoking a future conflict. Vittorio Emanuele Orlando represented Italy. He mainly insisted on obtaining the territories promised to Italy by the London Pact of 1915, although he had less influence on the final decisions than the other three. Japan, although a member of the Entente and present at the conference, did not play as prominent a role. Its main objective was to retain the territories and possessions it had acquired during the war, particularly in China and the Pacific.

President Woodrow Wilson had a very clear agenda for the conference, which he detailed in his famous "Fourteen Point Programme". These points aimed to establish a just and lasting peace after the war, and included principles such as freedom of the seas, an end to diplomatic secrecy, disarmament, self-determination of peoples, and a return to peaceful frontiers. Wilson's fourteenth point was particularly significant, as it proposed the creation of a "general association of nations", which would later become the League of Nations. This proposal was adopted and the League of Nations was founded as an international organisation dedicated to the maintenance of world peace and security. Ironically, however, despite Wilson's key role in the creation of the League of Nations, the United States never joined due to opposition from the US Senate. Although Wilson's ideals had a major influence on the conference and the resulting peace treaties, not all of his points were fully implemented. Some of Wilson's allies, particularly France and Britain, had different objectives, and the conference was marked by compromises and complex negotiations between the different parties.

Wilson's Fourteen Points[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

In January 1918, US President Woodrow Wilson addressed the US Congress with a detailed plan to secure lasting peace and global stability after the devastating horror of World War I.[4] This plan, known as Wilson's Fourteen Points, outlined a series of ambitious and visionary proposals that would redefine international relations. At the heart of these proposals was an urgent call for a significant reduction in armaments to a level strictly limited to the requirements of national security. Wilson saw this as a necessary step to reduce tensions and prevent the military escalation that had preceded the war. In addition, Wilson argued for the right of peoples to self-determination, stressing that each nation should be free to determine its own sovereignty and political destiny. This principle sought to dismantle the old system of empires and colonies and promote freedom and equality between nations. The proposal for the free navigation of ships in time of peace was part of Wilson's wider aim to promote free trade and international economic cooperation, thus helping to bind nations together by mutual interests and prevent conflict. Finally, perhaps Wilson's most innovative point was his call for the creation of an international organisation. This body would be responsible for maintaining world peace by preventing future conflicts through negotiation and dialogue. This vision eventually led to the creation of the League of Nations, laying the foundations for what would later become the United Nations.

Wilson's forward-looking and ambitious vision, embodied in his "Fourteen Points", truly propelled the American President to centre stage during the peace conference negotiations. These proposals undoubtedly marked a turning point in traditional approaches to diplomacy and were hailed for their innovative boldness. However, it is crucial to recognise that not all of the "Fourteen Points" found favour in the final agreements of the conference. Indeed, some of Wilson's most progressive ideas were countered by the resistance and political realities expressed by the other powers at the negotiating table. This acted as a brake on the realisation of his entire peace programme. Nevertheless, despite these obstacles, the impact of the "Fourteen Points" on the landscape of international diplomacy was significant and undeniable. Wilson's proposal not only reinforced the United States' stature as a leader in world affairs, but also marked the beginning of a new era in international relations. Indeed, following the First World War, a new world order began to emerge, shaped in large part by Wilson's ideals. These principles of self-determination, free trade and multilateral dialogue for the peaceful resolution of conflict became fundamental elements of global governance, demonstrating the lasting impact of Wilson's vision.

Wilson's Fourteen Points were comprehensive and far-reaching proposals, addressing both the issues directly related to resolving the First World War and the wider issues that led to the outbreak of the conflict. These proposals aimed to create a more equitable and stable world order, and emphasised the need for international collaboration to achieve this. It was in this context that the United States, relatively untouched by the devastation and loss of life inflicted by the European conflicts, aspired to position itself as a central player in the Peace Conference. This desire was underpinned by a favourable economic climate that enabled them to assume the role of moralizing mediator, reinforced by the bold vision of Wilson's Fourteen Points. However, this American claim to diplomatic hegemony was not unanimously welcomed by the other nations taking part in the Conference. France and the United Kingdom, in particular, which had suffered considerable human and material losses during the war, were more concerned with defending their national interests and guaranteeing their future security. Despite these differences in outlook and objectives, the influence of the United States during the Paris Peace Conference remains undeniable. It played an essential role in defining the contours of a new world order emerging at the end of the First World War. Their influence helped shape a new era of international cooperation, guided in part by the principles set out in Wilson's Fourteen Points.

President Wilson's Fourteen Points proposal was structured around three central axes:

- The first category of points aimed to establish greater transparency and fairness in international relations. This included the promotion of open diplomacy, the elimination of secret agreements, freedom of the seas, equal terms of trade and arms control. These points were based on the conviction that global peace and stability could only be achieved through the promotion of fair and transparent international norms.

- The second category concerned the restructuring of post-war Europe. Several points proposed specific territorial changes, based on the principle of the self-determination of peoples, including the restoration of Belgium and France, the adjustment of Italy's borders, autonomy for the peoples of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, and the creation of an independent Polish state.

- Finally, the last point envisaged the creation of an international organisation dedicated to the peaceful resolution of conflicts. This led to the creation of the League of Nations, an institution designed to maintain world peace and resolve international disputes peacefully, in order to avoid a repetition of the horrors of the First World War.

Points aimed at establishing transparency and justice in international relations[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The first points of Wilson's Fourteen Points aimed to promote openness and fairness in international relations. These principles were based on the belief that world peace and stability could only be achieved through open diplomacy and fair relations between nations.

The abolition of secret diplomacy[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Wilson firmly believed that secret diplomacy, which had been a major feature of European politics before the First World War, had contributed to the instability and mistrust that eventually led to war. Therefore, in his Fourteen Points, he argued that all diplomatic negotiations should be conducted openly and in public. The abolition of secret diplomacy, as he envisaged it, was intended to bring greater clarity and transparency to international relations. Openly disclosing the terms of treaties and agreements would avoid the kind of misunderstandings and suspicions that had often poisoned relations between nations. Moreover, it would ensure that the actions of governments were accountable to their citizens and to the world at large. This vision broke with traditional diplomatic practice and represented a fundamental change in the way international affairs were conducted. It was an attempt to create a new world order based on mutual trust and cooperation, rather than rivalry and competition. Although the idea was revolutionary at the time, it met with considerable resistance from those who believed that secret diplomacy was a necessary tool to protect national interests. As a result, although the idea of greater transparency in diplomacy gained ground, the reality of international diplomacy did not always follow Wilson's ideal.

Freedom of the seas[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Wilson firmly believed that secret diplomacy, which had been a major feature of European politics before the First World War, had contributed to the instability and mistrust that eventually led to war. Therefore, in his Fourteen Points, he argued that all diplomatic negotiations should be conducted openly and in public. The abolition of secret diplomacy, as he envisaged it, was intended to bring greater clarity and transparency to international relations. Openly disclosing the terms of treaties and agreements would avoid the kind of misunderstandings and suspicions that had often poisoned relations between nations. Moreover, it would ensure that the actions of governments were accountable to their citizens and to the world at large. This vision broke with traditional diplomatic practice and represented a fundamental change in the way international affairs were conducted. It was an attempt to create a new world order based on mutual trust and cooperation, rather than rivalry and competition. Although the idea was revolutionary at the time, it met with considerable resistance from those who believed that secret diplomacy was a necessary tool to protect national interests. As a result, although the idea of greater transparency in diplomacy gained ground, the reality of international diplomacy did not always follow Wilson's ideal.

The removal of economic barriers between nations[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The removal of economic barriers was a fundamental part of Wilson's Fourteen Points, aimed at fostering the global economy and encouraging peaceful interdependence between nations. Wilson supported the idea that free and open trade between nations would contribute to world peace and prosperity. Nevertheless, this vision met with considerable resistance from some countries. Many states, particularly those seeking to protect their own national industries, feared that trade liberalisation would lead to economic domination by the strongest and most industrialised countries. They were concerned that the abolition of tariffs and import quotas could expose their economies to potentially devastating foreign competition. These fears were particularly acute among smaller or economically vulnerable nations. There were also fears that lowering trade barriers would lead to greater economic inequality, favouring the interests of the richest and most powerful countries at the expense of developing countries. Despite these controversies, the idea of removing economic barriers has continued to play an important role in the development of international economic policy. This influenced the formation of organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and eventually led to the creation of the World Trade Organisation.

Guaranteeing national sovereignty and political independence[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The assurance of national sovereignty and political independence formed the core of Wilson's Fourteen Points. In an era marked by colonial imperialism and territorial agreements, this proposal was intended to be a radical break. The central principle of this idea was that each state had the right to self-determination, to its own governance, without external intervention or domination. This philosophy was firmly opposed to the practices of territorial conquest and forced sovereignty. Wilson also advocated the protection of the rights of national minorities, a concept largely neglected in international relations at the time. In addition, the American President envisaged the establishment of peaceful means of resolving international conflicts to avoid the outbreak of destructive wars and to guarantee respect for the sovereignty of each nation. This innovative concept foreshadowed the subsequent emergence of international institutions designed to peacefully regulate relations between states. The aim of this vision was to build a new, fair and just world order, based on respect for the sovereign rights of each country. The idea was to abandon the imperialist and colonialist policies that had characterised international relations up to that time. This particular point was incorporated into the succession of international commitments, as evidenced by the United Nations Charter.

Points aimed at reorganising Europe after the war[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The points aimed at reorganising post-war Europe formed a significant part of Wilson's Fourteen Points.

Withdrawal of German military forces from occupied territories[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The withdrawal of German military forces from occupied territories was also an important point in Wilson's Fourteen Points. The aim was to put an end to the German occupation of many territories in Europe, particularly in Belgium, France and other countries, and to re-establish the independence of these states. The return of Alsace-Lorraine to France was one of the key points of Wilson's Fourteen Points. Alsace-Lorraine was a region of France that had been annexed by Germany in 1871, following the Franco-Prussian War. During the First World War, the region became a point of contention between France and Germany, with violent clashes taking place in the area. As part of the Fourteen Points, Wilson sought to resolve this issue by calling for Alsace-Lorraine to be returned to France. This decision was welcomed by the French and helped strengthen Wilson's position as an international leader. Wilson also called for the return of annexed or illegally occupied territories and the evacuation of German military forces from all German-controlled areas. In this way, he sought to re-establish an international order based on respect for the sovereignty of states and territorial integrity. This proposal was widely supported by the Allies during the First World War, and was incorporated into the peace agreements that followed the war, notably the Treaty of Versailles. However, the application of these provisions was difficult and controversial, particularly with regard to the war reparations demanded of Germany and the consequences of the war on borders and national minorities in Europe.

The reduction of national borders in Europe[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Wilson's idea of reducing national borders in Europe was really more a question of redefining or redrawing borders based on the principle of the self-determination of peoples. His idea was not to reduce the size or number of nation states, but rather to ensure that state boundaries corresponded as closely as possible to ethnic or linguistic boundaries. He argued that the peoples of Europe should be able to choose their own form of government and national allegiance. As a result, some national boundaries in Europe were changed or redefined following the First World War, often in line with Wilson's proposals. For example, Poland's independence was restored, with access to the sea to ensure its economic independence, and new states such as Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were created from the former central empires. Not all of Wilson's proposals were fully implemented, and some states expressed reservations or opposition to some of his ideas. In particular, the idea of the self-determination of peoples was criticised for its potential to create new tensions and conflicts, due to the many national minorities living in states where they did not constitute the majority.

The question of reorganising national borders in Europe was a major issue throughout the twentieth century. This was particularly the case in the wake of the two world wars, when the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires disintegrated, leading to the creation of new states and the redefinition of geographical boundaries. This process proved complex and often contested, as it involved reconciling divergent national interests, competing territorial claims and varied cultural and ethnic identities. After the First World War, for example, Wilson's principle of self-determination was used as a guide to redraw the map of Europe. This led to the creation of new independent nations such as Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, and the resurrection of Poland. However, these changes also generated conflict and tension, as they often involved the displacement of populations and conflicting territorial claims. Similarly, after the Second World War, the redefinition of borders in Europe was a delicate process, giving rise to numerous conflicts and territorial disputes. For example, the question of the future of East Prussia, Silesia and the Sudetenland, to name but a few, was a source of persistent tension and conflict. The reorganisation of national borders in Europe has been and remains a sensitive and complex subject. It requires a careful and balanced approach, which takes into account the aspirations, rights and interests of the various parties involved, while seeking to maintain peace and stability in Europe.

Guaranteeing the sovereignty and autonomy of oppressed peoples[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The affirmation of the sovereignty and autonomy of oppressed peoples was an essential part of Wilson's Fourteen Points. Wilson firmly maintained that lasting peace could only be achieved through respect for the rights of oppressed peoples to self-determination, i.e. to decide their own political and social destiny. Accordingly, it called for recognition of the autonomy and sovereignty of many ethnic and national groups that were then subordinate to foreign powers. These populations included those of Central and Eastern Europe, who were under the domination of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and those of the Balkans, who lived under the yoke of the Ottoman Empire. In addition, Wilson also envisaged the question of self-determination for the peoples of Africa and Asia, who were under the yoke of European colonialism. However, it should be noted that the application of the principle of self-determination in these regions met with strong resistance, particularly from the colonial powers, who were reluctant to relinquish their control over these territories. In the end, the promise of self-determination was a noble objective, but its implementation proved to be a major challenge, often hampered by divergent geopolitical interests and complex historical and cultural realities. Despite these challenges, however, the principle laid the foundations for a new framework for international relations, based on respect for the rights of peoples to decide their own future.

Wilson advocated the establishment of an international organisation to safeguard the rights of oppressed peoples and to resolve international conflicts peacefully. This vision led to the creation of the League of Nations in 1920. Although the ideals embodied in Wilson's Fourteen Points were widely admired, their application encountered many obstacles. The realities of international power, dominated by the interests of the Great Powers, as well as internal divisions and rivalries among the oppressed peoples themselves, often hampered the realisation of these principles. However, the affirmation of the importance of the sovereignty and autonomy of oppressed peoples was an essential milestone in the history of the decolonisation movements that emerged during the twentieth century. It also laid the foundations for a new approach to the rights of minorities, emphasising their right to self-determination and fair treatment. Despite the difficulties encountered in implementing these principles, their inclusion in Wilson's Fourteen Points marked a significant break with the previous world order and paved the way for a new approach to international relations, based on respect for the rights of peoples and the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

Points aimed at establishing an international organisation for the peaceful resolution of conflicts[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Against the backdrop of the devastation of the First World War, Wilson recognised the imperative of an international institution capable of arbitrating disputes between nations in order to prevent another catastrophe of such magnitude. He therefore proposed the creation of the League of Nations - which later became the United Nations - to serve as an international forum where problems could be resolved through diplomacy and dialogue rather than war. It is a fundamental concept that has shaped international diplomacy in the 20th century and beyond. This category of Wilson's Fourteen Points therefore has important historical significance and continues to influence the way the international community manages conflict today.

The creation of an international organisation to guarantee peace[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

Inspired by the desire to establish a lasting peace after the devastation of the First World War, Woodrow Wilson advocated the creation of an international organisation to guarantee peace. This fourteenth point of his programme reflected an innovative understanding of world diplomacy, a transition from an international system based on balances of power and bilateral agreements to a global architecture of multilateral collaboration. Wilson saw that war was often a symptom of the absence of mechanisms to resolve disputes between nations peacefully. He firmly believed that the creation of an international organisation, with the power to arbitrate disputes, facilitate dialogue and negotiation, and discourage aggression, could provide a significant barrier against future conflict.

This led to the development of the idea of a "League of Nations", which would be responsible for maintaining world peace. The League of Nations, the forerunner of today's United Nations, was created in 1920 with the aim of fostering international cooperation and achieving international peace and security. The League of Nations was established to promote international cooperation and maintain world peace. The principle was that international disputes would be resolved by negotiation and arbitration rather than by force or war. The main objective of the League was to prevent conflict and maintain peace, by monitoring international relations, resolving disputes and imposing sanctions. However, despite its ambitions, the League faced many challenges and failed to prevent the outbreak of the Second World War. The experience of the League, however, provided valuable lessons for the creation of the United Nations (UN) in 1945. The UN was designed to correct some of the shortcomings of the League, with a Security Council endowed with greater powers and a broader mandate to promote international cooperation in various fields, including human rights, economic and social development, and public health. Despite the failures of the League, Wilson's idea of an international organisation to resolve conflicts peacefully has continued to influence the design of world order and remains a key element of international governance today.

Promoting international cooperation in economic, social and cultural affairs[modifier | modifier le wikicode]

The last of Wilson's Fourteen Points put forward the idea of forming a general association of nations, which should be designed to offer mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to all states, large and small. This association would later be embodied in the League of Nations. In this context, Wilson stressed the importance of international cooperation not only in political affairs, but also in the economic, social and cultural fields. He argued that peace could only be lasting if it was accompanied by economic and social justice, and that nations should work together to promote economic development, eliminate trade barriers, improve working conditions and promote a decent standard of living for all. In practice, this has meant the establishment of international organisations specialising in different areas, such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO) for labour issues, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) for cultural and educational affairs, and the World Bank and International Monetary Fund for international economic cooperation. Although these ideas were not fully realised at the time of the creation of the League of Nations, they continued to influence the design of world order and were incorporated into the architecture of the United Nations and related international institutions after the Second World War. Thus, Wilson's vision of multidimensional international cooperation remains a key element of global governance today.

The resolution of international disputes by peaceful rather than military means[modifier | modifier le wikicode]