The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

| Faculté | Lettres |

|---|---|

| Département | Département d’histoire générale |

| Professeur(s) | Aline Helg[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] |

| Cours | The United States and Latin America: late 18th and 20th centuries |

Lectures

- The Americas on the eve of independence

- The independence of the United States

- The U.S. Constitution and Early 19th Century Society

- The Haitian Revolution and its Impact in the Americas

- The independence of Latin American nations

- Latin America around 1850: societies, economies, policies

- The Northern and Southern United States circa 1850: immigration and slavery

- The American Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861 - 1877

- The (re)United States: 1877 - 1900

- Regimes of Order and Progress in Latin America: 1875 - 1910

- The Mexican Revolution: 1910 - 1940

- American society in the 1920s

- The Great Depression and the New Deal: 1929 - 1940

- From Big Stick Policy to Good Neighbor Policy

- Coups d'état and Latin American populisms

- The United States and World War II

- Latin America during the Second World War

- US Post-War Society: Cold War and the Society of Plenty

- The Cold War in Latin America and the Cuban Revolution

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States was a social and political movement aimed at ending racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans in the mid-20th century. Young people, particularly students, played a crucial role in the movement. They organized and participated in sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and other forms of nonviolent protest to demand equal treatment under the law. The actions of these young people helped to bring national attention to the struggle for civil rights, and their bravery and determination inspired others to join the movement. Some of the most famous leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., were young when they became involved in the cause. Their efforts ultimately led to the passage of important legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which banned discrimination based on race in public accommodations and voting, respectively. The Civil Rights Movement remains an important part of American history, and its legacy continues to inspire young people today to fight for justice and equality.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday, January 15, is celebrated as Martin Luther King Jr. Day in the United States. It is a federal holiday that honors the life and legacy of one of the most influential leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. The holiday was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1983 and first observed as a federal holiday on January 20, 1986. It is now observed on the third Monday of January each year and is recognized as a day of service, where people are encouraged to volunteer and give back to their communities in honor of King's message of peace and social justice.[8][9][10][11]

Speech delivered on August 28, 1963 to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., is widely considered one of the greatest and most influential speeches of the 20th century.[12] According to U.S. Congressman John Lewis, who also spoke that day on behalf of the Coordinating Committee of Non-Violent Students. "By speaking as he did, he educated, he inspired, he guided not just the people who were there, but people across America and generations to come.[13]

During Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebrations, it is common to hear parts of King's famous speeches, including his "I Have a Dream" speech, which he delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. King's speeches continue to inspire people around the world with their message of equality, justice, and nonviolent resistance. His speeches are often used as a way to pay tribute to the diversity and minority rights in the United States and to celebrate the progress that has been made in the fight for civil rights. They also serve as a reminder of the work that still needs to be done to achieve King's vision of a just and equal society. King's speeches are timeless, and his message of hope, love, and reconciliation remains just as relevant today as it was in the 1960s. They are an important part of American history and continue to inspire people of all ages and backgrounds to work towards a more just and equal society.[14][15][16][17]

Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech was a powerful critique of the racial inequality and discrimination faced by African Americans in the United States. He spoke about the deep-seated injustices and indignities that African Americans were forced to endure, including segregation, discrimination in employment, and a lack of voting rights. However, despite the harsh realities that he addressed, King's speech was also a powerful expression of hope and a vision for a better future. He dreamed of a day when all people, regardless of their race, would be judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. He spoke of a future where his four children would "not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character."

After King's "I Have a Dream" speech, the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum and pressure grew on the federal government to take action to end racial segregation and discrimination. This pressure culminated in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial discrimination in public accommodations and in employment. The act also provided the federal government with the means to enforce desegregation. Additionally, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, which prohibited discriminatory voting practices that had been used to prevent African Americans from exercising their right to vote. The act also provided federal oversight of elections in states and localities with a history of voting discrimination. These two pieces of legislation were significant milestones in the struggle for civil rights and helped to end legal segregation and discrimination in the United States. They were a result of the hard work and determination of Civil Rights activists, including Martin Luther King Jr., and marked a major turning point in the fight for equality and justice for African Americans.

The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which was adopted in 1868, provides that no state shall "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." This amendment was intended to provide legal protections for the newly-freed slaves and ensure that they had the same rights and protections under the law as other citizens. The 15th Amendment, which was adopted in 1870, provides that the right of citizens of the United States to vote "shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." This amendment was enacted to ensure that African American men could vote and participate in the political process without being denied the right to vote based on their race or previous status as slaves. Both the 14th and 15th Amendments were important steps towards ensuring equal rights and protections for African Americans in the aftermath of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. However, despite these amendments, discrimination and segregation continued to persist, and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s was necessary to further advance the cause of equality and justice for African Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 helped to provide additional legal protections and enforcement mechanisms for the rights guaranteed by the 14th and 15th Amendments.

The United States was one of the last countries in the world to abolish slavery and was the only country in the Americas to have a system of legal segregation and discrimination based on race. Despite the guarantees of equal protection and voting rights enshrined in the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, discrimination and segregation persisted for many decades. Even after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, many other forms of discrimination and inequality persisted in the United States, including Jim Crow laws, redlining, and mass incarceration, among others. While progress has been made towards reducing racial inequality, the legacy of discrimination and inequality continues to be felt today, and ongoing efforts are needed to address these issues. While the United States was the only country in the Americas to have a system of legal segregation and discrimination based on race, discrimination and inequality based on race, ethnicity, and skin color have been widespread in other countries around the world, including the Americas. In many countries, these forms of discrimination persist to this day, and ongoing efforts are needed to address them.

Actors for change

African American rights were recognized in the mid-1960s due to the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement, a political and social movement aimed at ending racial segregation and discrimination. The Civil Rights Movement was not a sudden development, but rather the result of decades of organizing, protest, and activism by African Americans and their allies.

One of the key factors in the recognition of African American rights in the mid-1960s was the growth of the Black Freedom Struggle, which was a mass movement that sought to challenge and end segregation and discrimination. Activists such as Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and others used tactics such as peaceful protests, boycotts, and civil disobedience to draw attention to the injustices faced by African Americans and to demand change.

Another important factor was the changing political landscape of the United States in the 1960s. President John F. Kennedy, who was in office when the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum, was initially hesitant to take action on civil rights. However, he eventually came to support the movement and pushed for civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In addition, the Civil Rights Movement was a response to the broader social, cultural, and political changes that were taking place in the United States in the mid-1960s, including the rise of the counterculture, the feminist movement, and the anti-war movement. These movements helped to create a climate of social and political ferment in which the Civil Rights Movement could flourish.

Finally, the recognition of African American rights in the mid-1960s was also due to international pressure and the impact of the Civil Rights Movement on the world stage. The world was watching as the United States was grappling with the issue of racial inequality, and the actions of the Civil Rights Movement helped to inspire similar movements for social justice and equality around the world.

African-Americans of the South

African Americans in the South were some of the key actors in the Civil Rights Movement. After World War II, many African Americans in the South had returned from serving in the military and were no longer willing to accept the systemic racial segregation and discrimination that they faced.

These African Americans were inspired by the example of other oppressed groups around the world who were fighting for their rights and freedoms, and they began to organize and protest against the injustices they faced. They formed civil rights organizations, held protests and sit-ins, and engaged in other forms of nonviolent resistance to challenge the status quo.

The courage and determination of African Americans in the South, who risked their lives and livelihoods to demand equal rights and justice, was a critical factor in the success of the Civil Rights Movement. Their activism helped to draw attention to the injustices they faced, galvanized public support, and put pressure on the government to take action to end segregation and discrimination.

Without the bravery and commitment of African Americans in the South, it is unlikely that the Civil Rights Movement would have been as successful as it was in bringing about change and securing equal rights for African Americans

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in shaping the direction of civil rights and equality in the United States, and its policy direction has changed over time, becoming more progressive in some cases.

In the mid-twentieth century, the Supreme Court issued a number of landmark decisions that helped to advance the cause of civil rights and equality. For example, in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, setting the stage for the integration of schools across the country.[18][19][20][21]

In addition to Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court issued a number of other important decisions during the mid-twentieth century that helped to advance the cause of civil rights and equality. For example, in the 1964 case of Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in public accommodations based on race, color, religion, or national origin.

These and other decisions by the Supreme Court helped to establish the legal framework for civil rights and equality in the United States, and they continue to be highly influential today. The Supreme Court's role in shaping the direction of civil rights and equality remains an important aspect of American history and law.

Domestic and international context

Internal structural changes

The internal structural changes in American society during and after World War II played a significant role in the development of the Civil Rights Movement. As you mentioned, the mechanization of part of the cotton crop led to reduced rural employment and urbanization in the South, which in turn led to a migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North and West in search of better opportunities and greater freedom. This migration, known as the Great Migration, had a profound impact on American society and helped to lay the foundation for the Civil Rights Movement.

The Great Migration not only transformed the African American community in the North and West, but it also helped to increase communication and mutual support between African Americans across the country. The extension of communication and mutual aid between African Americans in the South and those in the North and West helped to strengthen the electoral weight of African Americans in the states of the East Coast and California. This increased political power, combined with the growing demands of the Civil Rights Movement and the broader changes in American society and the world, put pressure on politicians to address the issue of racial inequality and segregation. Over time, this pressure led to the passage of federal civil rights legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which helped to end legal segregation and discrimination in the United States and laid the foundation for a more equal and just society.

In the North and West, African Americans encountered new forms of racial discrimination and segregation, but they also found greater political and economic opportunities than they had in the South. This migration and the changes it brought about helped to create a more diverse and politically conscious African American community, which was better equipped to fight for its rights and demand equal treatment under the law.

With the beginning of modernization in the South, the attitudes of some whites began to change, especially with the arrival of white migrants to the Sun Belt. The increase in economic and social mobility, along with greater exposure to different ideas and cultural influences, led to a reconsideration of the strict segregationist policies that had long been in place. This shift in attitudes, combined with the pressure of the Civil Rights Movement and the increasing visibility of racial inequality, created the conditions for significant changes in the South, including the end of legal segregation and the expansion of voting rights for African Americans.

It's important to note that this change was not universal, and that resistance to desegregation and equality remained strong in some parts of the South. Nevertheless, the Civil Rights Movement and the broader changes in American society helped to move the country closer to the ideals of equality and justice enshrined in its founding principles.

In addition to the internal structural changes in American society, the Civil Rights Movement was also influenced by broader domestic and international developments, such as the Cold War, the growing influence of mass media, and the rise of the Black Power and anti-war movements in the 1960s. These developments helped to create a political and social climate that was more favorable to the demands of the Civil Rights Movement, and they helped to shape the direction of the movement and its ultimate outcomes.

The Cold War and Decolonization

This contrast between the ideals espoused by the United States and the reality of segregation and discrimination was also apparent in the context of decolonization and the fight for independence by many countries around the world. The United States, as a global superpower, was being closely watched by the international community, and the treatment of African Americans within its own borders was seen as a reflection of its commitment to freedom and democracy. This put pressure on the US government to address the issue of civil rights and work towards achieving greater equality for all its citizens, including African Americans. The Civil Rights Movement was part of a larger global movement towards greater freedom, equality, and human rights, and the changes that took place in the United States during this period had a significant impact on the rest of the world.

In 1944, Gunnar Myrdal published An American dilemma: The negro problem and modern democracy. This book was influential in highlighting the inconsistencies in American democracy and was widely read and discussed both within the United States and abroad. It helped to increase pressure on the government to address the issue of racial discrimination and segregation, and to take concrete steps towards ensuring equal rights for all citizens, regardless of their race or color. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s was, in part, a response to this growing awareness and demand for change, and the activism of individuals and organizations that emerged in response to these challenges helped to bring about significant progress in the struggle for civil rights and equality in the United States.[22]

The Soldier Voting Act of 1942, also known as the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act, allowed soldiers serving abroad during World War II to vote regardless of where they were stationed. This act was a response to the propaganda of the Axis powers, which portrayed the United States as hypocritical for promoting democracy abroad while denying it to African Americans at home. The act was a significant step towards enfranchising black soldiers and acknowledging the need for civil rights reform. However, it was just one of many actions taken during this time to address the issue of segregation and discrimination against African Americans in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement, which gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s, would eventually lead to the passage of significant legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which helped to secure the rights and freedoms of African Americans.[23][24][25][26]

When African American soldiers returned from the war, they sought to exercise their right to vote, believing that the recently enacted legislation would protect their ability to do so. However, white supremacists often used violence to prevent them from registering to vote in their home states. Despite facing ongoing segregation, African Americans began to increasingly resist and protest against it, staging open demonstrations and pushing for change.

In the late 1940s during the height of McCarthyism, the limitations placed on African Americans were significant. From 1924 to 1972, J. Edgar Hoover dominated the FBI and was fixated on the perceived threat of communist infiltration in the United States. As a result, any African Americans who called for civil rights or demanded reforms were frequently accused of being communists and un-American. Those who spoke out against racism even faced the confiscation of their passports.[27][28][29][30]

Additionally, with the inauguration of the UN headquarters in New York in 1949, it became increasingly difficult for the United States to maintain its image as a defender of democracy and the free world in the eyes of newly decolonized nations in Africa and Asia who had taken their place at the UN. The existence of segregation and discrimination within the United States cast a shadow on the country's claims of promoting freedom and equality.

This will further undermine the image of the United States as a beacon of democracy and freedom, as representatives from newly decolonized nations in Africa and Asia will experience segregation and discrimination while traveling in the southern states. The Soviet Union will use this as propaganda to further discredit the United States on the world stage. Moreover, this also creates a negative image for the United States in the eyes of the international community and raises questions about the country's commitment to democracy and human rights. However, at this time, the international pressure was not strong enough to prompt the US government to take action against segregation in the South.

The first stages of the fight: from 1955 to 1960

In 1954, the tide began to turn for African Americans with a shift in the Supreme Court. The Court, which had been dominated by Southerners, suddenly became more progressive, making its role crucial for all citizens in the United States.

In 1955, the Supreme Court began its deliberations on the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education. Represented by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the case challenged the "separate but equal" doctrine that had been upheld by the Supreme Court in 1896. This case was a crucial moment in the fight for African American rights, as it aimed to challenge the practice of segregation and discrimination that was prevalent in many parts of the country.[31]

In 1955, the Supreme Court was discussing one of the most significant cases in the history of the United States, Brown v. Board of Education. When one of the justices passed away, President Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren, a former Attorney General and popular Governor of California, to replace him. As a Republican who was in touch with the changing times, Warren believed that justice should evolve and adapt to current realities, rather than remain fixed in the past.[32][33][34][35][36][37]

In 1955, the NAACP lawyers presented evidence showing the disparity in the education received by black and white students due to segregation in schools. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that segregation in schools was unconstitutional and ordered public schools to integrate as soon as possible, without specifying a time frame. This ruling marked a significant step towards ending racial segregation in the United States.[38]

Under the leadership of Earl Warren, the Supreme Court made a series of landmark decisions during the period from 1954 to 1969 that reinterpreted the U.S. Constitution in a way that favored those who had previously been excluded, including African Americans. This had a significant impact on the protection of civil rights in the United States.

Earl Warren, during his tenure as Chief Justice, not only protected the rights of African Americans, but also advanced the rights of other marginalized groups, including women, Native Americans, Latinx Americans, the poor, and individuals with disabilities. He interpreted the U.S. Constitution in a way that provided these groups with greater freedom and equality.

These decisions, made in the years following the ruling on Brown v. Board of Education, effectively ended segregation in not just schools, but also in federal agencies and public spaces. These decisions marked a significant shift towards greater equality and freedom for African Americans, and other marginalized groups, who had long been denied their basic rights and dignity.

The landmark decision to make segregation in schools illegal was a major milestone for the African American community and had far-reaching implications. It not only required the federal government to enforce this ruling across the country, but also necessitated the deployment of the military and the FBI to ensure compliance with these new laws and protect the rights of African Americans.

This resulted in widespread acts of resistance and violence, including the bombing of homes and schools, and intimidation of African Americans who tried to assert their rights. The white supremacists who opposed the integration of schools and public spaces employed violent means to try and maintain the status quo. The federal government, under the pressure of the Supreme Court's decisions, was forced to send troops and enforce the integration of schools and public spaces, making the use of violence to maintain segregation illegal. Despite this, it was still a difficult and dangerous time for African Americans who were trying to claim their rights and live their lives as equal citizens.

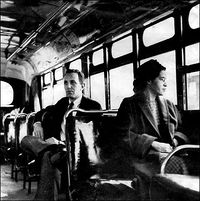

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, to a white man who was still standing. Her arrest and imprisonment sparked the famous Montgomery Bus Boycott, which lasted for over a year and was led by the 26-year-old Martin Luther King and the Christian Leadership Conference. This event played a crucial role in the fight for racial equality and propelled King to the forefront of the movement. Rosa Parks, a modest seamstress, was also an activist with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and was aware of the risks she was taking by standing up against segregation. Her actions eventually led to the integration of public transportation.[39][40][41][42]

The Little Rock Nine, as they came to be known, faced intense opposition and hostility as they attempted to integrate Little Rock Central High School. In response to the segregationist governor of Arkansas refusing to allow nine black youths to integrate Little Rock Middle School in 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower requisitioned more than 1,000 soldiers to ensure the integration of the school. This action was necessary to ensure the enforcement of the Supreme Court's decision on desegregation and to protect the rights of African American students. The deployment of soldiers caused widespread violence and protests, and attracted international attention and criticism. Despite this, President Eisenhower believed it was necessary to uphold the law and ensure that the decision of the Supreme Court was carried out. Despite the presence of federal troops, the nine students still faced harassment and violence from segregationists. This event drew widespread attention and sparked protests around the country, while also giving the Soviet Union an opportunity to criticize the United States for its treatment of African Americans and distract from its own actions in Eastern Europe. The integration of Little Rock Central High School was a turning point in the civil rights movement and demonstrated the federal government's commitment to ending segregation in public schools.[43][44][45][46]

These sit-ins and boycotts were part of a larger movement known as the Civil Rights Movement, which aimed to end segregation and discrimination against African Americans. The Greensboro sit-ins, in particular, were part of a wave of nonviolent protests that took place across the country. The protesters faced violence and arrests, but their bravery and persistence eventually led to the desegregation of many businesses and public spaces. These events were significant in inspiring other activists to take up the cause of civil rights, and they helped to bring the issue of racial equality to the forefront of national attention.

John F. Kennedy became president in January 1961.

As president, Kennedy's main focus was on foreign policy and facing the expansionist policies of the Soviet Union in Asia, Africa, and Cuba. However, he was also concerned about maintaining the support of Democratic voters in the Southern states, and as a result, he did not actively address the issue of racial segregation in the South during his presidency.

The "Freedom Rides" were a series of civil rights protests that took place in the early 1960s, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The purpose of the Freedom Rides was to test and challenge the implementation of a 1960 Supreme Court decision that banned segregation in transportation facilities. The Freedom Riders, a group of white and black activists, rode buses together to challenge the segregation laws and test if the federal government would enforce them. John F. Kennedy, who became president in January 1961, was in a difficult position with regards to the Freedom Rides. On one hand, he was committed to advancing civil rights and promoting equality. On the other hand, he was facing opposition from many Southern states, who were resistant to change and segregation, and he needed the support of these states to advance his legislative agenda. As a result, Kennedy was trying to prevent the Freedom Rides from taking place, as he believed that they would cause chaos and violence, and would harm his efforts to gain support from the Southern states.

However, the Freedom Riders continued their journey, and when they arrived in Alabama, they were met with violence and resistance from segregationists. Kennedy was forced to send in federal troops to restore order and protect the Freedom Riders. This incident put pressure on Kennedy to take a more active role in addressing the issue of racial segregation and inequality in the South. As a result of the pressure, Kennedy eventually became more involved in the civil rights movement and gave a famous speech in June 1963 calling for the end of segregation and the passage of civil rights legislation. This speech is seen as a turning point in Kennedy's presidency and in the civil rights movement, and set the stage for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed by Congress and signed into law. The Act banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in employment practices and public accommodations. This was a major step forward in the fight for racial equality in the United States.[47][48][49][50][51][52]

In Alabama and Mississippi, the Freedom Riders faced brutal attacks from members of the Ku Klux Klan, and the Kennedy administration was forced to take action to protect them and enforce the law. The violent response to the Freedom Rides drew national attention to the issue of segregation and the lack of enforcement of federal laws. It was a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement, and it helped to galvanize support for further action to end segregation. The Freedom Rides ultimately contributed to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made segregation in public accommodations illegal and ensured the enforcement of the desegregation of public transportation.[53]

The case of the Voter Education Project in Mississippi

Kennedy sought to redirect this movement toward preparing blacks to register as voters: blacks were subject to "voter fitness" tests.[54][55] This route was less risky than the Freedom Riders.

He created the Voter Education Project in 1962 under the protection of the federal government and the FIB, but in Mississippi it shows the limits of Kennedy's commitment to blacks, pushing some blacks to renounce non-violence.[56][57]

Mississippi is one of the poorest states and a bastion of segregation; blacks who have been fighting for civil rights since 1945 are being laid off, chased off the farms they live on, beaten up and murdered.

What will begin to mobilize opinion is the lynching of a young black boy in Chicago who was 14 years old, Emmet Till; his mother in Chicago decided to allow the photo of his disfigured corpse to be published by the national and international press.[58][59][60][61][62][63]

There was a trial with an all-white jury, and twice the jury acquitted all the defendants; at the same time, it gave a boost to the courage of the blacks in Mississippi who began to demonstrate more directly.[64]

This change will accelerate with the arrival of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which is another youth organization created in 1960, a multiracial Christian youth movement.[65][66][67][68]

The aims of this movement are not only to register blacks at the polling stations, but also to develop grassroots organizations at the local level that give priority to youth and women. Young people who join the SNCC drop out of school to participate in social change in small towns in the South, they represent the radical wing for the black representation movement that pushes Martin Luther King's struggle towards the centre.

In Mississippi they are going to do a huge job of recruiting communities with assemblies to mobilize people to read, to write, to take charge of their lives deciding to work for Kennedy's Voting Education Project; but the voter aptitude test is facing.[69]

In Mississippi in 1960, only 5 percent of blacks were in a position to vote; when they were not attacked, the candidates on the voters' lists were rejected. A year after the campaign was launched, 63 activists were assassinated without the Kennedy government reacting.

Washington denounces the lack of success of the Voting Education Project, which ceases to provide funding.

In 1963, when a group of students arrived in Mississippi to supervise the Voting Education Program, the FBI began to protect blacks.

They decided to play the game inviting several hundred students from the North and East to force the FBI to protect their Mississippi voting campaign. That's when two volunteers, two whites and a black from the South, disappear. The government sends hundreds of police and FBI agents to find them. It is only two months later that their bodies are found, the two white men shot and the black man tortured to death.

During their search, the FBI found a number of black bodies without opening investigations; this increases the feeling that the whites want to undermine the process of local self-determination; there is a change of strategy and they will do without the protection of the white students taking up arms especially since the FBI does not react to the murders in Mississippi.

Starting in 1953, the violence of the Ku Klux Klan redoubles, as well as that of the police and governors of the South begins to be shown on television screens, making it increasingly difficult to legitimize the UN headquarters in New York.

The great turning point for John F. Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy's Civil Rights Address on June 11, 1963.[70][71][72]

Kennedy did not take action until 1963 when Alabama police cracked down on a civil rights and integration protest, mostly youth and school children demonstrating; these events occurred at the same time as a movement for African unity was taking place in Addis Ababa.

The Soviet press seized on this to criticize the United States, and Kennedy made a speech on television calling on Congress to pass a civil rights framework law.[73][74][75]

In August 1963, the entire civil rights movement gathered more than 200,000 people for a march to Washington, D.C., leading to a tacit agreement between Kennedy and the organizers to avoid radical speeches in exchange for a framework law that would allow the dissemination of soothing images of the march.

Part of Martin Luther King's visionary speech is in which he portrays himself as Moses to the whole of reconciled America. After Kennedy's assassination in 1963, Lyndon B Johnson, the first president from the South, takes up the torch and obtains congressional approval guaranteeing black suffrage; the story ends with a legislative triumph.

Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering his "I Have a Dream" speech.

After 1965: division of the black movement

After 1965, the black movement split with the Civil Right of 1964 which forbids segregation leading to the creation of a commission to control the "segregationist" fact; this is an end in itself for those like Martin Luther King who advocate the fight for concrete equality, socio-economic equality and total integration, however one frankly wants black separatism.[76]

We must not forget that there is a huge difference between blacks from the North, South and West Coast, because the 1965 Voting Act was a victory only for the 11 million blacks in the South, but not for the 7 million blacks living in the ghettos.

We enter a period of riots in the ghettos of the North and California exploding in violent revolts characterized by looting, fires, police and military repression; these years are marked by enormous violence and by murders after that of Kennedy in 1963 by those of Malcolm X in 1965, those of Luther King and Robert Kennedy in 1968.

It is the gulf between the northern ghettos and the suburban villa zones that explains the explosion and the solution that would be a kind of Marshall Plan.

Johnson launches a policy to fight poverty, but at the same time he sinks into the Vietnam War where blacks are killed disproportionately. In 1968, youth revolts shook the world and the United States, leading to the election of Nixon as president.

The deep south is still reacting to all these laws with the candidacy of Wallace who creates an American Independent Party in order to have a segregationist as president, but who fails showing that mentalities take a long time to evolve and that it is necessary to continue to claim rights that are never acquired for everyone.

Annexes

Brown v. Board of Education - les arrêts

- Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 493 (1954)

- Brown v. Board of Education 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

- Bolling v. Sharpe 347 U.S. 497 (1955)

References

- ↑ Aline Helg - UNIGE

- ↑ Aline Helg - Academia.edu

- ↑ Aline Helg - Wikipedia

- ↑ Aline Helg - Afrocubaweb.com

- ↑ Aline Helg - Researchgate.net

- ↑ Aline Helg - Cairn.info

- ↑ Aline Helg - Google Scholar

- ↑ Weiss, Jana (2017). "Remember, Celebrate, and Forget? The Martin Luther King Day and the Pitfalls of Civil Religion", Journal of American Studies

- ↑ Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service official government site

- ↑ [King Holiday and Service Act of 1994] at THOMAS

- ↑ Remarks on Signing the King Holiday and Service Act of 1994, President William J. Clinton, The American Presidency Project, August 23, 1994

- ↑ Stephen Lucas et Martin Medhurst, « "I Have a Dream" Speech Leads Top 100 Speeches of the Century », University of Wisconsin News, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 15 décembre 1999 (lire en ligne).

- ↑ A "Dream" Remembered, NewsHour, 28 août 2003.

- ↑ I Have a Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Future of Multicultural America, James Echols – 2004

- ↑ Alexandra Alvarez, "Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor", Journal of Black Studies 18(3); doi:10.1177/002193478801800306.

- ↑ Hansen, D, D. (2003). The Dream: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins. p. 58.

- ↑ "Jones, Clarence Benjamin (1931– )". Martin Luther King Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle (Stanford University).

- ↑ Horwitz, Morton J. (Winter 1993). "The Warren Court And The Pursuit Of Justice". Washington and Lee Law Review. 50.

- ↑ Powe, Jr., Lucas A. (2002). The Warren Court and American Politics. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Swindler, William F. (1970). "The Warren Court: Completion of a Constitutional Revolution" (PDF). Vanderbilt Law Review. 23.

- ↑ Driver, Justin (October 2012). "The Constitutional Conservatism of the Warren Court". California Law Review. 100 (5): 1101–1167. JSTOR 23408735.

- ↑ Myrdal, Gunnar (1944). An American dilemma: The negro problem and modern democracy. New York: Harper & Bros.

- ↑ Inbody, Donald S. The Soldier Vote War, Politics, and the Ballot in America. Palgrave Macmillan US :Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- ↑ Schønheyder, Caroline Therese. “U.S. Policy Debates Concerning the Absentee Voting Rights of Uniformed and Overseas Citizens, 1942-2011.” Thesis / Dissertation ETD, 2011.

- ↑ Coleman, Kevin. (2010). The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act: Overview and Issues.

- ↑ US Policy Debates Concerning the Absentee Voting Rights, United States. Congress, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1944

- ↑ Krenn, Michael L. The African American Voice in U.S. Foreign Policy since World War II. Garland Pub., 1999.

- ↑ Maxwell, William J. F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover's Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature. Princeton Univ. Press, 2017.

- ↑ Executive Order 9981 - On July 26, 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 establishing equality of treatment and opportunity in the Armed Services. This historic document can be viewed here.

- ↑ Jon E. Taylor, Freedom to Serve: Truman, Civil Rights, and Executive Order 9981 (Routledge, 2013)

- ↑ Patterson, James T. (2001). Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195156324.

- ↑ Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506557-2.

- ↑ Belknap, Michael (2005). The Supreme Court Under Earl Warren, 1953–1969. The University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-563-0.

- ↑ Cray, Ed (1997). Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren. ISBN 978-0-684-80852-9.

- ↑ Powe, Lucas A. (2000). The Warren Court and American Politics. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674006836.

- ↑ Schwartz, Bernard (1983). Super Chief: Earl Warren and His Supreme Court, A Judicial Biography. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814778265.

- ↑ Urofsky, Melvin I. (2001). The Warren Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576071601.

- ↑ See, e.g., Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education, Berea College v. Kentucky, Gong Lum v. Rice, Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, and Sweatt v. Painter

- ↑ Aguiar, Marian; Gates, Henry Louis (1999). "Southern Christian Leadership Conference". Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 0-465-00071-1.

- ↑ Cooksey, Elizabeth B. (December 23, 2004). "Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)". The new Georgia encyclopedia. Athens, GA: Georgia Humanities Council. OCLC 54400935. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ↑ Fairclough, Adam. To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr. (University of Georgia Press, 2001)

- ↑ Garrow, David. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1986); Pulitzer Prize

- ↑ Faubus, Orval Eugene. Down from the Hills. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing, 1980. 510 pp. autobiography.

- ↑ Anderson, Karen. Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School (2013)

- ↑ Baer, Frances Lisa. Resistance to Public School Desegregation: Little Rock, Arkansas, and Beyond (2008) 328 pp. ISBN 978-1-59332-260-1

- ↑ Kirk, John A. "Not Quite Black and White: School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954-1966," Arkansas Historical Quarterly (2011) 70#3 pp 225–257 in JSTOR

- ↑ Meier, August; Rudwick, Elliott M. (1975). CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement, 1942-1968. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252005671.

- ↑ Frazier, Nishani (2017). Harambee City: Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1682260186.

- ↑ Congress of Racial Equality Official website

- ↑ Harambee City: Archival site incorporating documents, maps, audio/visual materials related to CORE's work in black power and black economic development.

- ↑ Catsam, Derek (2009). Freedom's Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813173108.

- ↑ Niven, David (2003). The Politics of Injustice: The Kennedys, the Freedom Rides, and the Electoral Consequences of a Moral Compromise. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572332126.

- ↑ "Civil rights rider keeps fight alive" . Star-News. 30 June 1983. pp. 4A

- ↑ PEDAGOGÍA INTERNACIONAL: CUANDO LA INSTRUCCIÓN CÍVICA SE CONVIERTE EN UN PELIGRO PARA LA VIDA..., R. UEBERSCHLAG - The student, international student magazine.

- ↑ Whitby, Kenny J. The Color of Representation: Congressional Behavior and Black Interests. University of Michigan Press, 1997. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.14985.

- ↑ The Voter Education Project, King Research & Education Institute ~ Stanford University.

- ↑ Voter Education Project, Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ Tyson, Timothy B. (2017). The Blood of Emmett Till, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-1484-4

- ↑ Anderson, Devery S. (2015). Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

- ↑ Houck, Davis; Grindy, Matthew (2008). Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press, University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-934110-15-7

- ↑ Whitaker, Hugh Stephen (1963). A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Emmett Till Case. M.A. thesis, Florida State University.

- ↑ The original 1955 Jet magazine with Emmett Till's murder story pp. 6–9, and Emmett Till's Legacy 50 Years Later" in Jet, 2005.

- ↑ Documents regarding the Emmett Till Case. Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- ↑ Federal Bureau of Investigation. Prosecutive Report of Investigation Concerning (Emmett Till) Part 1 & Part 2 (PDF).

- ↑ Hogan, Wesley C. How Democracy travels: SNCC, Swarthmore students, and the growth of the student movement in the North, 1961–1964.

- ↑ Hogan, Wesley C. Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC's Dream for a New America, University of North Carolina Press. 2007.

- ↑ Carson, Clayborne (1981). In Struggle, SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Founded ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans.

- ↑ The Voter Education Project, King Research & Education Institute ~ Stanford University.

- ↑ Goduti Jr., Philip A. (2012). Robert F. Kennedy and the Shaping of Civil Rights, 1960-1964. McFarland. ISBN 9781476600871.

- ↑ Goldzwig, Steven R.; Dionisopolous, George N. (1989). "John F. Kennedy's civil rights discourse: The evolution from "principled bystander" to public advocate". Communication Monographs. Speech Communication Association. 56 (3): 179–198. doi:10.1080/03637758909390259. ISSN 0363-7751.

- ↑ Loevy, Robert D. (1997). The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law That Ended Racial Segregation (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791433614.

- ↑ Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Pub.L. 88–352 , 78 Stat. 241 , enacted July 2, 1964)

- ↑ Civil Rights Act Passes in the House ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ "A Case History: The 1964 Civil Rights Act". The Dirksen Congressional Center.

- ↑ The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Background and Overview (PDF), Congressional Research Service